Abstract

Objectives

To estimate the extent to which prepregnancy obesity explains the Black-White disparity in stillbirth and infant mortality.

Methods

A population-based study of linked Pennsylvania birth-infant death certificates (2003-2011; n=1,055,359 births) and fetal death certificates (2006-2011; n=3,102 stillbirths) for all singleton pregnancies in non-Hispanic (NH) White and NH Black women. Inverse probability weighted regression was used to estimate the role of prepregnancy obesity in explaining the race-infant/fetal death association.

Results

Compared with NH White women, NH Black women were more likely to be obese (≥30kg/m2) and experienced a higher rate of stillbirth (8.3 vs. 3.6 stillbirths per 1,000 liveborn and stillborn infants) and infant death (8.5 vs. 3.0 infant deaths per 1,000 livebirths). When the contribution of prepregnancy obesity was removed, the difference in risk between NH Blacks and NH Whites decreased from 6.2 (95% CI: 5.6, 6.7) to 5.5 (95% CI: 4.9, 6.2) excess stillbirths per 1,000 and 5.8 (95% CI: 5.3, 6.3) to 5.2 (95% CI: 4.7, 5.7) excess infant deaths per 1,000.

Conclusions

For every 10,000 livebirths in Pennsylvania (2003 to 2011), six of the 61 excess infant deaths in NH Black women and 5 of the 44 excess stillbirths (2006-2011) were attributable to prepregnancy obesity.

Keywords: Race, obesity, infant mortality, stillbirth

Introduction

Reducing racial inequalities in adverse perinatal outcomes is among the most important public health priorities in the United States. In 2013, infants born to non-Hispanic Black mothers experienced 11.1 deaths per 1,000 live births. In contrast, the rate among non-Hispanic Whites was 5.1 deaths per 1,000 live births1. This disparity has persisted over the past decade with an infant mortality rate 2.2 times higher for non-Hispanic Black women in 2013 decreasing only slightly from 2.4 in 20001. Similarly, non-Hispanic Black mothers are subject to more than twice the stillbirth risk of non-Hispanic Whites. The rate of stillbirth in non-Hispanic White women in 2013 was 4.9, compared to a rate of 10.5 in non-Hispanic Black women2. The causal status of these differences is subject to much controversy and debate3-7. This is largely because “race” is the result of a set of social, political, economic, historical, cultural, and biological processes that interact in complex ways8-11. However, the fact that these differences exist and are important is uncontroversial. Furthermore, despite decades of study, little is known about what actually explains this stark racial gap in fetal and infant mortality12.

Interestingly, a similar Black-White inequality exists for maternal obesity. Non-Hispanic Black women carry the burden of the obesity epidemic in the U.S. Nearly three-quarters of non-Hispanic Black childbearing-aged women are overweight (body mass index [BMI]≥25 kg/m2)13 and more than half are obese (BMI ≥30 kg/m2)14. These percentages are approximately 1.5 times that of non-Hispanic White women of equal age. Additionally, at 10%, the prevalence of severe obesity (BMI ≥35 kg/m2) in non-Hispanic Black women is twice the rate of their non-Hispanic White counterparts13. Finally, a growing body of research suggests important biologic differences in obesity phenotypes and the effect of obesity across racial groups, including adipose tissue deposition and associations with C-reactive protien15,16.

There is strong evidence linking prepregnancy obesity to adverse infant outcomes including infant mortality and stillbirth17-20. The risk of infant mortality has been shown to rise as prepregnancy BMI increases20. This relationship holds true for risk of stillbirth with a 2-fold increase in risk of infant death for women who start their pregnancy as obese compared to those women of normal prepregnancy BMI17.

Despite the seriousness of health inequalities and the evidence linking maternal prepregnancy obesity to racially-disparate birth outcomes, the interrelationships among race, obesity, and perinatal death are understudied. Understanding the magnitude to which obesity does or does not contribute to the racial disparity in perinatal death is important to inform future research efforts to reduce the disparity. Our objective was to assess the extent to which maternal prepregnancy obesity may explain the Black-White disparity in infant mortality and stillbirth in a census of Pennsylvania births.

Methods

Penn MOMS is a population-based study of linked birth-infant death certificates and fetal death (stillbirth) certificates in Pennsylvania that was designed to evaluate maternal weight and weight gain in relation to adverse birth outcomes. The study was approved by the University of Pittsburgh Institutional Review board. Data cleaning and birth-infant death matching procedures have been described in detail previously21.

The 2003 revision of the U.S. Standard Certificates of Live Birth and Death and the Fetal Death Report capture data that allow for the calculation of prepregnancy BMI22. Pennsylvania adopted the revised birth certificate in 2003 and fetal death certificate in 2006. Records from these respective years up to and including 2011 were used for this analysis. Of the 1,265,127 eligible singleton births and 8,362 eligible singleton stillbirths, we excluded 29,871 records (2.3%) with missing data on birth weight, gestational age, infant's gender, or birth facility or records with a gestational age <20 or >42 weeks. We then excluded records in which the maternal self-reported race/ethnicity was not non-Hispanic (NH) Black or non-Hispanic (NH) White (n=178,341) and records of fetuses or infants with congenital anomalies (n=6,816). Of the remaining 1,058,461 records, there were 150,506 births and 1,569 stillbirths with missing data on prepregnancy BMI or one of the covariates used in the final models. We used multiple imputation to handle these missing data (described below). The final analytic sample included 1,055,359 births (2003-2011) and 3,102 stillbirths (2006-2011).

Pennsylvania defines stillbirth as a delivery that results in a fetus of ≥16 weeks gestation that shows no evidence of life after it is entirely ex utero. We chose to study stillbirth at ≥20 weeks gestation for consistency with the literature. Infant mortality was defined as death of a live-born infant before 365 days of life. Infant death was further classified into neonatal death (infant death before 28 days of life) and post-neonatal death (infant death from 28 to 364 days of life). Gestational age is reported on the birth and fetal death certificates using the best obstetric estimate, which we have shown to have high accuracy23.

Prepregnancy weight and height on the birth and fetal death certificates were self-reported by the mother before hospital discharge. We classified prepregnancy BMI (weight (kg)/height (m)2) for the analysis as obese (BMI ≥30.0 kg/m2) or not obese (BMI <30 kg/m2) and severely obese (BMI ≥35.0 kg/m2) or not severely obese (BMI <35 kg/m2). Our primary analysis compared women with obesity to those without obesity. We then chose to compare women with severe obesity to those without severe obesity as a secondary analysis.

Before hospital discharge, mothers reported their education, age, marital status, smoking status before pregnancy, enrollment in the Special Supplemental Program for Women Infants and Children (WIC), and insurance status (private vs. public). Hospital staff recorded the number of previous liveborn infants. The delivering hospital's level of neonatal care was classified as I, II, or III24. Urban residence was informed using county-level FIPS codes obtained from the Pennsylvania Bureau of Health Statistics which geocodes maternal address in the birth record. These FIPS codes were used to merge with the U.S. Department of Agriculture Economic Research Service Urban-Rural Continuum Codes to determine the urbanicity of the county of maternal residence25. These variables were used as confounders of the relation between prepregnancy obesity or severe obesity and the outcome of interest. Continuous and categorical confounders were adjusted for using regression splines and indicator coding, respectively.

Statistical analysis

Missing data were imputed 10 times with a Markov chain Monte Carlo approach26. Missing data for prepregnancy weight and height, weight at delivery, age, race/ethnicity, parity, smoking status prior to pregnancy, education, insurance, marital status, urban residence, and enrollment in WIC were jointly imputed using the infant's birth weight, sex, gestational age, year of birth, infant death, neonatal level of care, and infant admission into the neonatal intensive care unit21. Neither fetal nor infant death was imputed. The details of the multiple imputation analysis have been described elsewhere21.

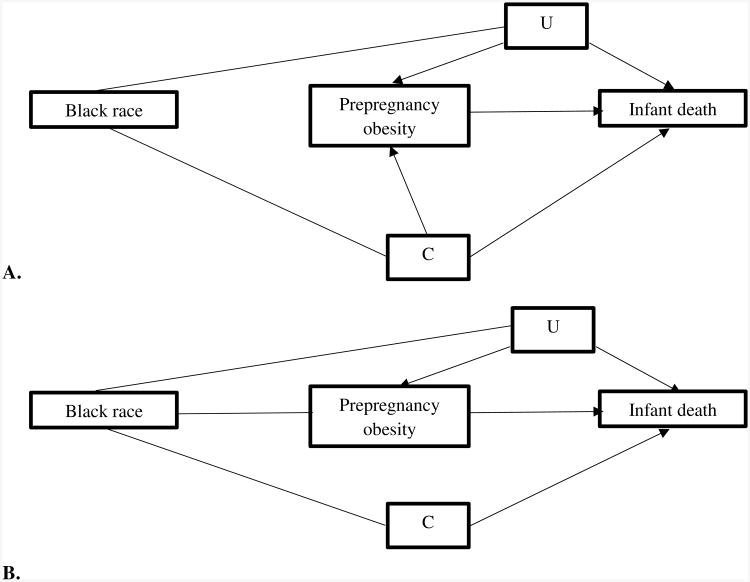

Figure 1 displays the diagram that guided our analytic framework. We followed previous research and studied race a marker of disparity, or difference between racial groups, rather than an etiologic factor3,27. While this approach does not deny its potentially etiologic role, it does enable us to (i) quantify the extent to which the racial groups in our cohort differ with respect to infant mortality, and (ii) assess the extent to which these differences are due to the differential patterns of obesity between racial groups. Maternal age, height, education, marital status, smoking, parity, insurance, WIC status, urban residence, percent Black residents, and hospital's level of neonatal intensive care (denoted C in Figure 1) are potential mediators of the race/ethnicity-death association and also confounders of the obesity-death association. Potential unmeasured confounders are denoted ‘U’ in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

1A. Diagram of relationships between Black race, prepregnancy obesity, and infant death. This accounts for confounders of the prepregnancy obesity status-infant death association (C), and unmeasured confounders (U). 1B. Relationship between Black race, prepregnancy obesity, and infant death after accounting for inverse probability weighting.

Our analytic approach consisted of three steps. We first fit a logistic regression model to estimate the total association between race and infant death (all pathways from NH Black race/ethnicity to death in Figure 1, Panel A). Because our interest is in race as a marker of disparity, we estimated unadjusted associations for the relation between race and birth outcomes3.

We next added our measure of prepregnancy obesity and the interaction between prepregnancy obesity and race to this logistic model, and weighted this model using stabilized inverse probability weights, defined as:

where M denotes obesity status (1 if obese, 0 otherwise) and X denotes race (1 if NH Black, 0 if NH White). The numerator and denominator of these weights were obtained as the predicted probabilities from a logistic model regressing obesity against race (numerator), and obesity against race and our identified confounders (denominator).

A logistic model regressing infant mortality against race, obesity, and their interaction, weighted by sw enabled us to estimate the direct association between race and infant mortality that is not attributed to maternal obesity (the pathways from NH Black race to death not through obesity)28. Confounding adjustment for the relation between obesity and birth outcomes is accomplished via inverse probability weighting by sw, which essentially modifies the diagram in Figure 1, Panel A to that in Figure 1, Panel B27. We obtained risk differences from this logistic model via marginal standardization (using the ‘margins’ command in Stata)29. Standard errors were obtained using the robust (sandwich) variance estimator30. Additional details, including the Stata code we used to conduct our analyses, are provided in Appendix 1.

Weights had a mean of 1 with no extreme values. As a final step, we calculated the proportion of the risk difference between NH Black race and death potentially accounted for by prepregnancy obesity as [(Total Association-Direct Association)/Total Association]*10031.

These analyses were repeated with stillbirth, neonatal mortality and post-neonatal mortality as outcomes, where denominators were based on infants alive at the start of each period. In other words, all stillbirth analyses included both stillborn and liveborn infants, while infant mortality analyses included only livebirths. We also replaced maternal obesity with severe obesity and repeated analyses. Ad hoc sensitivity analyses were conducted by (1) including those with missing data on birth weight, gestational age, infant's gender, or birth facility prior to imputation of the data, and (2) including infants with congenital anomalies (n=6,816: stillbirth=373, infant deaths=1,362).

Results

In the cohort of Black and White mothers, 17% of women were NH Black, 22% had obesity before pregnancy, and 10% had severe obesity. Women with obesity were more likely than women without obesity to be NH Black, multiparous, less educated, receiving WIC assistance, and to live in non-metropolitan areas (Table 1).

Table 1.

Maternal characteristics by prepregnancy obesity (body mass index≥30 kg/m2), Pennsylvania stillbirths and live births, 2003 to 2011 (n=1,058,461).

| Obese n=235,510 | Not Obese n=822,951 | |

|---|---|---|

| Race/ethnicity | ||

| Non-Hispanic White | 77.9 | 84.9 |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 22.1 | 15.1 |

| Age (years) | ||

| <20 | 5.5 | 9.2 |

| 20-29 | 51.9 | 49.8 |

| >29 | 42.6 | 41.0 |

| Parity | ||

| 1 | 35.6 | 43.0 |

| 2 or more | 64.4 | 57.0 |

| Marital status | ||

| Married | 59.8 | 63.3 |

| Unmarried | 40.2 | 36.7 |

| Education | ||

| Less than high school | 12.6 | 13.9 |

| High school | 32.5 | 25.4 |

| Some college | 32.0 | 26.3 |

| College graduate | 22.8 | 34.4 |

| Smoking status prior to pregnancy | ||

| Nonsmoker | 75.0 | 76.0 |

| Smoker | 25.0 | 24.0 |

| Insurance | ||

| Private | 59.2 | 64.6 |

| Medicaid, self-pay, or other | 40.8 | 35.4 |

| WIC Status | ||

| Assistance | 42.8 | 32.2 |

| No Assistance | 57.2 | 67.8 |

| Residential status | ||

| Metropolitan, >1 million | 49.1 | 52.2 |

| Metropolitan, 250,000 to 1 million | 27.8 | 27.7 |

| Metropolitan, <250,000 | 9.5 | 8.8 |

| Non-metropolitan | 13.6 | 11.3 |

| Birth facility neonatal care | ||

| Level I | 24.5 | 21.6 |

| Level II | 15.7 | 16.6 |

| Level III | 59.8 | 61.8 |

Stillbirth and infant death occurred at a rate two to three times higher in NH Black women compared with NH White women (Table 2). This racial disparity was observed for both neonatal (5.3 vs. 1.9 per 1,000 livebirths) and post-neonatal mortality (3.3 vs. 1.1 per 1,000 livebirths). Compared with women without obesity, women with obesity had a higher rate of stillbirth and infant death.

Table 2.

Stillbirths and infant deaths by maternal race/ethnicity and prepregnancy obesity status (BMI ≥ 30kg/m2) for at risk pregnancies in Pennsylvania, 2003-2011.

| Stillbirtha | Infant Deathb | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Events (n) | Population at risk | Stillbirths per 1,000 liveborn and stillborn infants | Events (n) | Population at risk | Deaths per 1,000 live births | |

| Maternal race/ethnicity | ||||||

| NH Black | 1,012 | 121,789 | 8.3 | 1,494 | 175,133 | 8.5 |

| NH White | 2,090 | 583,345 | 3.6 | 2,643 | 880,226 | 3.0 |

| Prepregnancy BMI | ||||||

| Obese | 1,013 | 161,414 | 6.3 | 1,225 | 234,497 | 5.2 |

| Not Obese | 2,089 | 543,720 | 3.8 | 2,912 | 820,862 | 3.5 |

Sample limited to stillbirths from 2006-2011.

Livebirths from 2003-2011.

NH=non-Hispanic, BMI=body mass index

The unadjusted total associations between race and stillbirth, and the direct association indicating the part of the relation not attributed to obesity, are displayed in Table 3. These associations are expressed as the excess cases per 1,000 pregnancies comparing NH Black women with NH White women. For every 1,000 liveborn and stillborn infants, NH Black women had 6.2 (95% CI: 5.6, 6.7) more stillbirths relative to NH White women (Table 3). After removing the portion of this association attributable to obesity, this number dropped to 5.5 (95% CI: 4.9, 6.2) excess stillbirths. Redefining obesity to severely obese (BMI ≥ 35kg/m2) slightly attenuated this observed decrease in excess risk. These data suggest that 10.6% of the association of race and stillbirth was explained by prepregnancy obesity and 4.7% by severe obesity.

Table 3.

Race/ethnicity-stillbirth association and race/ethnicity-stillbirth association not attributable to prepregnancy obesity per 1,000 stillbirths and livebirths in Pennsylvania, 2006 to 2011 (n=705,134)a.

| Events (n) | Population at risk | Unadjusted risk per 1,000 liveborn and stillborn infants | Race/ethnicity-stillbirth association: RD per 1,000 liveborn and stillborn infants (95% CI) | Association not attributed to prepregnancy obesity: RD per 1,000 liveborn and stillborn infants (95% CIs) | Proportion of total explained by obesity | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||

| BMI≥30 kg/m2 | BMI≥35 kg/m2 | BMI≥30 kg/m2 | BMI≥35 kg/m2 | |||||

| Stillbirth | ||||||||

| NH Black | 1,012 | 121,789 | 8.3 | 6.2 (5.6, 6.7) | 5.5 (4.9, 6.2) | 5.9 (5.2, 6.5) | 10.6% | 4.7% |

| NH White | 2,090 | 583,345 | 3.6 | Reference | Reference | Reference | ||

Births with congenital anomalies not included.

RD=Risk Difference, NH=non-Hispanic

Table 4 demonstrates these associations for infant, neonatal, and post-neonatal death. NH Black women had 5.8 (95% CI: 5.3, 6.3) excess cases of infant mortality for every 1,000 live births compared with NH Whites. After removing the portion attributable to obesity or severe prepregnancy obesity, the number of excess cases decreased. Similar relationships were seen when infant mortality was further classified into neonatal and post-neonatal death. The proportion of the association between race and mortality that was explained by obesity ranged from 9.7% to 10.0% and 4.9% to 7.1% for severe obesity (BMI ≥35 kg/m2).

Table 4.

Race/ethnicity-infant mortality association and race/ethnicity-infant mortality association not attributable to prepregnancy obesity per 1,000 live births in Pennsylvania, 2003 to 2011 (n=1,055,359)a.

| Events (n) | Population at risk | Unadjusted risk per 1,000 live births | Race/ethnicity-infant mortality association: RD per 1,000 live births (95% CI) | Association not attributed to prepregnancy obesity: RD per 1,000 live births (95% CIs) | Proportion of total explained by obesity | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||

| BMI≥30 kg/m2 | BMI≥35 kg/m2 | BMI≥30 kg/m2 | BMI≥35 kg/m2 | |||||

| Infant death | ||||||||

| NH Black | 1,494 | 175,133 | 8.5 | 5.8 (5.3, 6.3) | 5.2 (4.7, 5.7) | 5.5 (5.0, 5.9) | 9.8% | 5.9% |

| NH White | 2,643 | 880,226 | 3.0 | Reference | Reference | Reference | ||

| Neonatal death | ||||||||

| NH Black | 926 | 175,133 | 5.3 | 3.7 (3.3, 4.1) | 3.3 (2.9, 3.8) | 3.5 (3.1, 3.9) | 9.7% | 4.9% |

| NH White | 1,636 | 880,226 | 1.9 | Reference | Reference | Reference | ||

| Post-neonatal death | ||||||||

| NH Black | 568 | 174,207 | 3.3 | 2.1 (1.8, 2.4) | 1.9 (1.6, 2.2) | 2.0 (1.7, 2.2) | 10.0% | 7.1% |

| NH White | 1,007 | 878,590 | 1.1 | Reference | Reference | Reference | ||

Births with congenital anomalies not included.

RD=risk difference, BMI= body mass index, NH=non-Hispanic

Results were not meaningfully different when we retained pregnancies with missing data on birth weight, gestational age, infant's gender, or birth facility or those with congenital anomalies (Table S1 and Table S2).

Discussion

Our goal was to estimate the extent to which prepregnancy obesity explains the racial disparities in infant and fetal death in Pennsylvania. Using this large, population-based cohort, we observed that maternal obesity may explain approximately 10% of the Black-White disparity in stillbirth and infant mortality; severe obesity alone may contribute about 5% to that inequality. More specifically, for every 10,000 live births in Pennsylvania from 2003 to 2011, approximately 6 of the 61 excess infant deaths occurring in non-Hispanic Black women, and 5 of the 44 excess stillbirths were attributable to prepregnancy obesity. We chose to also assess the role of severe obesity as a secondary analysis to determine the extent to which associations seen in obesity were driven by women with severe obesity. Furthermore, an association seen in women with severe obesity, may be a more feasible group for future study as there are fewer women with severe obesity.

Our conceptual and methodologic framework permitted us to isolate the role of maternal obesity from all other pathways through which the racial disparity in poor perinatal outcomes may operate. We accomplished this via inverse probability weighting, which simultaneously adjusted for potential confounding of the association between prepregnancy obesity and adverse perinatal outcomes, while quantifying the total racial disparity in these same outcomes15,16. We specifically chose not to adjust for additional racially disparate comorbidities (e.g. gestational hypertension), which may also account for a portion of the racial disparity in infant mortality, as this would have led to an overestimation of obesity's role in explaining the disparity27.

Self-reported measures of race/ethnicity represent an array of social, political, cultural, and biological processes that interact in complex ways8-10. Such processes have long characterized U.S. race relations, making it difficult to assert that estimated coefficients for self-reported race are counterfactually causal32. These difficulties underlie much of the debate on the causal status of race. However, our use of race as a marker of disparity is agnostic to its causal status: it does not require one adopt a position on whether race is causal or not, but underscores the important differences that exist between racial groups.

As with other studies that use observational data to examine obesity effects, clarifying the policy implications of our results will require additional research for a number of reasons33. First, prepregnancy weight can be reduced through many different approaches, including physical activity or diet interventions. Different interventions to reduce or eliminate prepregnancy obesity would likely result in different effects, and thus varying proportions of the racial disparity attributable to this risk factor. Second, population-level reductions of the prevalence of prepregnancy obesity can be accomplished by preventing the onset of obesity in women without obesity of childbearing age or by reducing the body mass of women with obesity of childbearing age to below a given obesity threshold (or both). These alternative obesity prevalence reduction strategies may also have different impacts on infant mortality. Third, eliminating obesity or severe obesity entirely from the population is not currently feasible and unlikely in a population health setting (although methods do exist to quantify realistic intervention effects34,).

Our study builds on previous reports suggesting such mediation may be occurring. In two recent papers, Salihu et al. used over 1 million Missouri vital records (1978–1997) to examine racial differences in the relationship between pregravid obesity and neonatal mortality35 and stillbirth.36 The investigators reported that prepregnancy obesity was more strongly associated with neonatal mortality and stillbirth among Black women than among White women, suggesting a potential mediating role of prepregnancy obesity. Other researchers reported similar results in an analysis of Florida birth certificates from March to December in 2004 (n=166,301 birth records linked to n=1,015 infant death records)37. They found that among Black women, maternal obesity was associated with a 1.5-fold increase in the risk of infant mortality (95% CI: 1.2, 2.0), while among White women, there was no meaningful increase (adjusted odds ratio 1.1, 95% CI: 0.82, 1.3). However, the results of these studies could not be used to quantify the degree to which the racial disparity in perinatal mortality was attributable to prepregnancy obesity.

Our findings should be considered in light of certain limitations. As in previous studies, we were unable to account for potential confounding by diet, maternal stress, and exercise. In our analyses of stillbirths we did not discern antepartum from intrapartum stillbirths. Our results may also be subject to bias from obesity misclassification that varies by race, as prepregnancy weight was self-reported23. However, when we accounted for this misclassification in previous studies, our results were not meaningfully different21. Finally, the information needed to classify women based on Hispanic origin (e.g., Puerto Rican, Mexican, Cuban), which strongly influences rates of infant death1, was unavailable on a large proportion of Hispanic women. However, this affects the generalizability, but not the internal validity of our results. We encourage others to apply our analytic framework in future research studies of obesity-mediated inequalities in ethnically-diverse populations.

While our results cannot be generalized to the entire U.S. population, our use of a large and recent population of NH Black and NH White women yields several strengths. Pennsylvania is the 6th most populous State in the U.S., and the Black-White gap in perinatal mortality represents the largest racial/ethnic disparity in the U.S1.

Our findings shed light on the potential mechanisms underlying the racial disparity in stillbirth and infant death38. Evidence on the role that prepregnancy obesity plays in perpetuating racial disparities in these birth outcome scan help to prioritize further research aimed at reducing disparities. Although the causes of racial disparities are multifactorial, we focus on maternal obesity as it is currently a public health epidemic and, in principle, it is amenable to modification39. Furthermore, our innovative approach enabled us to isolate the role that prepregnancy obesity plays, independent of other characteristics also associated with race, obesity, and infant mortality. Future research should aim to develop and evaluate the impact of targeted interventions to optimize pregravid BMI in different racial/ethnic groups with the ultimate purpose of improving the survival of fetuses and infants in the U.S.

Supplementary Material

Study Importance Questions.

What is already known about this subject?

Non-Hispanic Black women experience infant mortality and stillbirth at a rate twice that of non-Hispanic White women in the U.S.

Non-Hispanic Black women are more likely to be obese compared with non-Hispanic White women in the U.S.

The effect of maternal obesity on infant mortality and stillbirth varies by race.

What does your study add?

We estimate the extent to which prepregnancy obesity status contributes to the racial disparity in stillbirth and infant mortality between non-Hispanic Black and non-Hispanic White women.

Acknowledgments

Sources of Funding: This project was supported by NIH grant R21HD065807; Lara S. Lemon is a Ruth Kirschstein T-32 grant recipient.

Footnotes

Disclosures: No conflicts of interest

References

- 1.Matthews TJ, MacDorman MF, Thoma ME. Infant Mortality Statistics From the 2013 Period Linked Birth/Infant Death Data Set. National vital statistics reports : from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics, National Vital Statistics System. 2015;64(9):1–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.MacDorman MF, Gregory EC. Fetal and Perinatal Mortality: United States, 2013. National vital statistics reports : from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics, National Vital Statistics System. 2015;64(8):1–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kaufman JS, Cooper RS. Seeking causal explanations in social epidemiology. American journal of epidemiology. 1999;150(2):113–120. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.VanderWeele TJ, Robinson WR. On the causal interpretation of race in regressions adjusting for confounding and mediating variables. Epidemiology (Cambridge, Mass) 2014;25(4):473–484. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0000000000000105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Glymour C, Glymour MR. Commentary: race and sex are causes. Epidemiology (Cambridge, Mass) 2014;25(4):488–490. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0000000000000122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Krieger N. On the causal interpretation of race. Epidemiology (Cambridge, Mass) 2014;25(6):937. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0000000000000185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zuberi T. Deracializing Social Statistics: Problems in the Quantification of Race. Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science. 2000;568:172–185. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Krieger N. Refiguring “race”: epidemiology, racialized biology, and biological expressions of race relations. International journal of health services : planning, administration, evaluation. 2000;30(1):211–216. doi: 10.2190/672J-1PPF-K6QT-9N7U. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Krieger N. Stormy weather: race, gene expression, and the science of health disparities. American journal of public health. 2005;95(12):2155–2160. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.067108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Graves JL. The Emperor's new clothes : biological theories of race at the millennium. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jacobson MF. Whiteness of a different color: European immigrants and the alchemy of race. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Macdorman MF, Mathews TJ. Recent trends in infant mortality in the United States. NCHS data brief. 2008;(9):1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Institute of Medicine, National Research Council Committee to Reexamine IOMPWG. The National Academies Collection: Reports funded by National Institutes of Health. In: Rasmussen KM, Yaktine AL, editors. Weight Gain During Pregnancy: Reexamining the Guidelines. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US) National Academy of Sciences; 2009. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Fryar CD, Flegal KM. Prevalence of Obesity Among Adults and Youth: United States, 2011-2014. NCHS data brief. 2015;(219):1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rahman M, Temple JR, Breitkopf CR, Berenson AB. Racial differences in body fat distribution among reproductive-aged women. Metabolism: clinical and experimental. 2009;58(9):1329–1337. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2009.04.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Clark DO, Unroe KT, Xu H, Keith NR, Callahan CM, Tu W. Sex and Race Differences in the Relationship between Obesity and C-Reactive Protein. Ethnicity & disease. 2016;26(2):197–204. doi: 10.18865/ed.26.2.197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chu SY, Kim SY, Lau J, et al. Maternal obesity and risk of stillbirth: a metaanalysis. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology. 2007;197(3):223–228. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2007.03.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stothard KJ, Tennant PW, Bell R, Rankin J. Maternal overweight and obesity and the risk of congenital anomalies: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Jama. 2009;301(6):636–650. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nelson SM, Matthews P, Poston L. Maternal metabolism and obesity: modifiable determinants of pregnancy outcome. Human reproduction update. 2010;16(3):255–275. doi: 10.1093/humupd/dmp050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Johansson S, Villamor E, Altman M, Bonamy AK, Granath F, Cnattingius S. Maternal overweight and obesity in early pregnancy and risk of infant mortality: a population based cohort study in Sweden. BMJ (Clinical research ed) 2014;349:g6572. doi: 10.1136/bmj.g6572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bodnar LM, Siminerio LL, Himes KP, et al. Maternal obesity and gestational weight gain are risk factors for infant death. Obesity (Silver Spring, Md) 2015 doi: 10.1002/oby.21335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.CDC National Center for Health Statistics. Birth Edit Specifications for the 2003 Proposed Revision of the U.S. Standard Certificate of Birth. 2003 http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/dvs/birth_edit_specifications.pdf.

- 23.Bodnar LM, Abrams B, Bertolet M, et al. Validity of birth certificate-derived maternal weight data. Paediatric and perinatal epidemiology. 2014;28(3):203–212. doi: 10.1111/ppe.12120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stark AR. Levels of neonatal care. Pediatrics. 2004;114(5):1341–1347. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-1697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.USDA. Rural-Urban Continuum Codes. 2013 http://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/rural-urban-continuum-codes.aspx#.U7WgCvldUg0.

- 26.Royston P. Multiple imputation of missing values: Further update of ice, with an emphasis on categorical variables. Stata J. 2009;9:466–477. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Naimi AI, Schnitzer ME, Moodie EE, Bodnar LM. Mediation analysis for health disparities research. American journal of epidemiology. 2015 doi: 10.1093/aje/kwv329. In Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.VanderWeele TJ. Marginal structural models for the estimation of direct and indirect effects. Epidemiology (Cambridge, Mass) 2009;20(1):18–26. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e31818f69ce. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Localio AR, Margolis DJ, Berlin JA. Relative risks and confidence intervals were easily computed indirectly from multivariable logistic regression. Journal of clinical epidemiology. 2007;60(9):874–882. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2006.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.White H. A Heteroskedasticity-Consistent Covariance Matrix Estimator and a Direct Test for Heteroskedasticity. Econometrica. 1980;48(4):817–838. [Google Scholar]

- 31.VanderWeele TJ. Policy-relevant proportions for direct effects. Epidemiology (Cambridge, Mass) 2013;24(1):175–176. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e3182781410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Naimi AI. The Counterfactual Implications of Fundamental Cause Theory. Curr Epidemiol Reports. 2016 in press. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hernán MA, Taubman SL. Does obesity shorten life? The importance of well-defined interventions to answer causal questions. International journal of obesity (2005) 2008;32(3):S8–14. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2008.82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Westreich D. From exposures to population interventions: pregnancy and response to HIV therapy. American journal of epidemiology. 2014;179(7):797–806. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwt328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Salihu HM, Alio AP, Wilson RE, Sharma PP, Kirby RS, Alexander GR. Obesity and extreme obesity: new insights into the black-white disparity in neonatal mortality. Obstetrics and gynecology. 2008;111(6):1410–1416. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e318173ecd4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Salihu HM, Dunlop AL, Hedayatzadeh M, Alio AP, Kirby RS, Alexander GR. Extreme obesity and risk of stillbirth among black and white gravidas. Obstetrics and gynecology. 2007;110(3):552–557. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000270159.80607.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Thompson DR, Clark CL, Wood B, Zeni MB. Maternal obesity and risk of infant death based on Florida birth records for 2004. Public health reports (Washington, DC:1974) 2008;123(4):487–493. doi: 10.1177/003335490812300410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Naimi AI, Kaufman JS. Counterfactual Theory in Social Epidemiology: Reconciling Analysis and Action for the Social Determinants of Health. Curr Epidemiol Rep. 2015;2(1):52–60. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Atkinson RL, Pietrobelli A, Uauy R, Macdonald IA. Are we attacking the wrong targets in the fight against obesity?: the importance of intervention in women of childbearing age. International journal of obesity (2005) 2012;36(10):1259–1260. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2012.149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.