Abstract

Pain perception can become altered in individuals with eating disorders and obesity for reasons that have not been fully elucidated. We show that leptin deficiency in ob/ob mice, or leptin insensitivity in the arcuate nucleus of the hypothalamus in mice with high-fat diet (HFD)-induced obesity, are accompanied by elevated orexin-A (OX-A) levels and orexin receptor-1 (OX1-R)-dependent elevation of the levels of the endocannabinoid, 2-arachidonoylglycerol (2-AG), in the ventrolateral periaqueductal gray (vlPAG). In ob/ob mice, these alterations result in the following: (i) increased excitability of OX1-R-expressing vlPAG output neurons and subsequent increased OFF and decreased ON cell activity in the rostral ventromedial medulla, as assessed by patch clamp and in vivo electrophysiology; and (ii) analgesia, in both healthy and neuropathic mice. In HFD mice, instead, analgesia is only unmasked following leptin receptor antagonism. We propose that OX-A/endocannabinoid cross talk in the descending antinociceptive pathway might partly underlie increased pain thresholds in conditions associated with impaired leptin signaling.

INTRODUCTION

Eating disorders and obesity are accompanied by altered pain perception (Lautenbacher et al, 1990; Papežová et al, 2005; Foo and Mason, 2009; Rodgers et al, 2014). Although this phenomenon might be a consequence of changes in the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis, stress response, and related or unrelated endocrine modifications (Lewis et al, 1980), its exact underlying mechanisms have not been elucidated.

The periaqueductal gray (PAG) is a key supraspinal site of the descending antinociceptive pathway (DAP), including the rostral ventromedial medulla (RVM) and dorsal horn of the spinal cord. Activation of PAG excitatory output neurons projecting monosynaptically to OFF and ON cells in the RVM causes antinociception via their stimulation and inhibition, respectively (Reynolds, 1969; Behbehani et al, 1990; Yilmaz et al, 2010).

Stimulation of the DAP, particularly following stress, relies in part on cannabinoid receptor type-1 (CB1) activation by the endocannabinoid 2-arachidonoylglycerol (2-AG), which disinhibits PAG output neurons through retrograde inhibition (Ohno-Shosaku and Kano, 2014) of GABA release from interneurons (Hohmann et al, 2005; Gregg et al, 2012). Orexinergic neurons of the lateral hypothalamus project to the vlPAG (Peyron et al, 1998; van den Pol et al, 1998), where activation of orexin type-1 receptors (OX1-R) by orexin-A (OX-A) stimulates 2-AG biosynthesis via the phospholipase C-diacylglycerol lipase α (DAGLα) route, thus potentially producing analgesia (Ho et al, 2011; Watanabe et al, 2005; Azhdari-Zarmehri et al, 2013, 2014). Yet, the role of OX-A, 2-AG, and DAPs in the alterations of pain perception during obesity or eating disorders has never been investigated.

Leptin is a circulating anorexigenic and pro-inflammatory adipokine produced by the adipose tissue, which reduces both endocannabinoid (Di Marzo et al, 2001) and OX-A (Goforth et al, 2014) signaling in the hypothalamus. Its levels are altered in obesity as well as during anorexia and binge-eating disorder (Monteleone et al, 2000; Cristino et al, 2014, for review). In agreement with the role of OX-A in the regulation of feeding (Sakurai et al, 1998) and energy homeostasis (Tsujino and Sakurai, 2009), not only leptin-deficient (ob/ob) obese mice but also mice with high-fat diet (HFD)-induced obesity exhibit increased OX-A signaling in many orexin hypothalamic target areas, ultimately due to selective leptin receptor (LeptR) desensitization in the arcuate nucleus (ARC) (Cristino et al, 2013). Elevated circulating leptin in HFD mice stimulates tumor necrosis factor-α and interleukin production by activating LeptRs in peripheral organs and macrophages, thereby potentially exacerbating pain and inflammation (Deng and Scherer, 2010; Maeda et al, 2009). On the other hand, it is not known whether defective leptin signaling in the hypothalamus instead reduces pain by causing enhanced endocannabinoid/OX-A signaling in the vlPAG.

We report that an OX-A/endocannabinoid cross talk, under the negative control of leptin, stimulates the DAP, thus partly explaining the changes in pain perception associated with conditions of altered leptin signaling, such as eating disorders and obesity.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Pain Models of SNI

Mononeuropathy was induced according to the method described elsewhere (Decosterd and Woolf, 2000). Adult (9–11 weeks old) male lean (wt) and obese (ob/ob) mice were anesthetized with sodium pentobarbital (50 mg/kg, i.p.). The sciatic nerve was exposed at the level of its trifurcation into sural, tibial, and common peroneal nerves. The tibial and common peroneal nerves were ligated tightly with 5.0 silk thread and then transected just distal to the ligation, leaving the sural nerve intact. Sham mice were anesthetized, and the sciatic nerve was exposed at the same level, but not ligated.

Drug Delivery

PAG cannulation, intrathecal catheterization, and subsequent injections, including bilateral PAG microinjections, were performed as described in detail in the Supplementary Methods.

RVM in vivo Extracellular Recordings

For electrophysiological experiments, adult (9–11 weeks old) male lean (wt, SFD) and obese (ob/ob, HFD) mice were anesthetized with pentobarbital (50 mg/kg, i.p.) and a 26-gauge, 10-mm-long stainless-steel guide cannula was stereotaxically lowered until its tip was 1 mm above the left vlPAG by applying coordinates (AP: −4.84 mm from bregma, L: 0.5 mm, V: 3.3 mm below the dura). The cannulae were anchored with dental cement to a stainless-steel screw in the skull according to the procedure described in detail in the Supplementary Material.

Patch-Clamp Recordings

Coronal midbrain slices (250 μm thick) containing the PAG were dissected from 6- to 9-week-old male wt and ob/ob mice. The dissection medium contained (in mM) 220 sucrose, 2.5 KCl, 6 MgCl2, 1.25 NaH2PO4, 26 NaHCO3, and 1 CaCl2, and was oxygenated with 95% O2/5% CO2, pH 7.4. After dissection, the slices were equilibrated in artificial cerebrospinal fluid (aCSF) at 32°C for at least 30 min before recording. The aCSF contained (in mM) 122 NaCl, 2.5 KCl, 2 CaCl2, 2 MgCl2, 1.23 NaH2PO4, 26 NaHCO3, 10 glucose, 3 Na-Pyruvate, and 1 Na-Ascorbate, and was oxygenated with 95% O2/5% CO2, pH 7.4. Subsequently, one slice at a time was transferred to a submerged recording chamber and continuously perfused with oxygenated aCSF at a rate of 3–4 ml/min at room temperature. Recording electrodes (6.4 MΩ on average) were made from borosilicate glass pipettes (Warner Instruments, Hamden, CT, USA). The internal solution consisted of (in mM) the following: 125 K-gluconate, 5 KCl, 0.5 CaCl2, 10 HEPES, 5 BAPTA, 0.33 GTP-Tris, 5 ATP-Mg, pH 7.29 with KOH, and 276 mOsm/l. The liquid junction potential (LJP) was calculated using JPCalc (provided with the pCLAMP software, Version 10.4.0.36) and was experimentally verified to be 12.1 mV. The LJP was corrected offline. vlPAG neurons were first identified either as projecting neurons or as interneurons, on the basis of their intrinsic membrane properties, and further classified as FS or TS according to the criteria described elsewhere (Park et al, 2010) (details in the Supplementary Material).

RMP of vlPAG-RVM neurons was subsequently determined as the average value during a 1-min-long trace, recorded after 5 min of stable RMP value. Afterward, the OX1 receptor antagonist SB334867 (12 μM) was administered to the aCSF reservoir. Five minutes after SB334867 administration, RMP was determined again.

RESULTS

An overview of some of the most significant results, proposed anatomical pathways, synaptic receptor distribution, and mechanism of endocannabinoid/orexin-modulated antinociceptive vlPAG/RVM descending projections described here is schematically presented in panels A–D of Figure 1. These results were obtained in two models of obese mice (see details in the Supplementary information): (1) Adult male B6.Cg-Lepob/J mice, obese because of a spontaneous nonsense mutation of the Ob gene for leptin (ob/ob, JAX© mouse strain), matched to lean wt Ob gene-expressing homozygous siblings; (2) 16–18-week-old C57BL/6J male mice made obese after 7 weeks of HFD (4.7 kcal/g: 49% fat, 18% protein, and 33% carbohydrate), matched to 16–18-week-old lean male mice, fed for 7 weeks with a standard-fat diet (SFD: 3.5 kcal/g, 14.5% of energy as fat). The metabolic parameters of these models have been reported previously (Cristino et al, 2013). In brief, HFD-induced obese mice became obese (Supplementary Figure S1A), hyperleptinemic (Supplementary Figure S1B), and leptin resistant (Supplementary Figure S1C) after 7 weeks of an ad libitum HFD. Mice of the same strain fed an SFD for 7 weeks remained lean and leptin- and insulin-sensitive (Supplementary Figure S1).

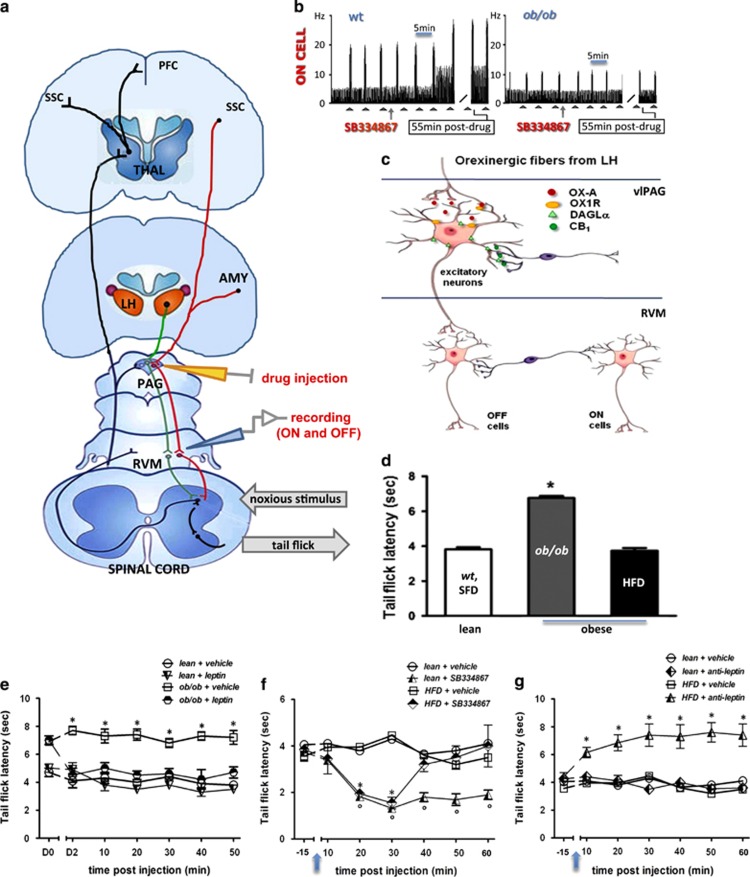

Figure 1.

Endocannabinoid/orexin-mediated control of the vlPAG/RVM nociceptive pathway. (a–d) An overview of the proposed anatomical pathway, synaptic receptor distribution, and mechanism of endocannabinoid/orexin-modulated antinociceptive vlPAG/RVM descending projections. (a) Incoming nociceptive signals from the spinal dorsal horn are processed through ascending projections to the RVM, vlPAG and THAL. These nociceptive signals are under descending control by cell projections from the vlPAG, via ON and OFF neurons in the RVM ('ON' cells are represented in green, and ‘OFF' cells are represented in red). AMY, amygdala; LH, lateral hypothalamus; PAG, periaqueductal gray; PFC, prefrontal cortex; RVM, rostroventral medulla; SSC, somatosensory cortex; THAL, thalamus; vlPAG, ventrolateral periaqueductal gray. (b) The spontaneous firing of neurons in the RVM is controlled by orexin-A-positive nerve terminals originated in the lateral hypothalamus (HYP, orange in panel a) and is modulated by local vlPAG microinjection of antagonist for OX1-R (SB334867) or CB1R (not shown) or leptin (not shown). SB334867 (0.05 mmol) microinjection into the vlPAG stimulates ON cell nociceptive firing in wt but not in obese ob/ob mice. (c) Presynaptic CB1 receptors, mostly localized on GABAergic interneurons, modulate the activity of excitatory (possibly glutamatergic) output neurons of the vlPAG, which make direct connections to RVM. In ob/ob mice the overstimulation of OX1-R receptors localized in the vlPAG output neurons leads to an enhancement of 2-AG levels with subsequent stimulation of presynaptic CB1 receptors, disinhibition of vlPAG output neurons, and activation of RVM OFF cells, which results in analgesia. RVM ON cells might be inhibited by the same vlPAG output neurons via a GABAergic interneuron. (d) ob/ob mice (gray bar) show a higher tail-flick latency compared with lean mice (white bar), whereas high-fat diet (HFD) mice (black bar) do not. (e) Leptin injection (5 mg/kg, daily i.p. per 2 days (D1 and D2); D0 being the day before the first injection) in ob/ob mice restores thermal noxious latency. (f) Acute i.p. injection of the OX1-R antagonist, SB334867 (60 mg/kg, 15 min after baseline recording), in HFD mice significantly decreases thermal latency 20 and 30 min post injection. (g) Acute i.p. injection of a leptin receptor antagonist (anti-leptin, 5 mg/kg, 15 min after baseline recording) increases thermal latency 10 min after treatment until the end of the observation. Data are expressed as means±SEM of eight mice per group. *P<0.05 indicates statistical difference between ob/ob and lean mice (e) and between HFD and lean mice (f and g) for individual time points. Statistical analysis was performed by one-way ANOVA (d) and two-way ANOVA (e–g) followed by the Bonferroni post hoc test.

In order to evaluate the thermal nociceptive latency in wt, SFD, ob/ob, and HFD mice, we performed a tail-flick test. As no difference was found between the thermal pain threshold of wt and SFD mice (wt: 3.92±0.14 s and SFD: 3.68±0.12 s), we pooled these values together and referred hereafter to this group as ‘lean' in these behavioral experiments (wt+SFD: 3.8±0.13 s). Noteworthy, mice lacking leptin (ob/ob) showed antinociceptive behavior in terms of a higher tail-flick latency compared with lean mice, whereas HFD mice did not show any significant changes in thermal response as compared with lean mice (6.76±0.11 s for ob/ob vs 3.8±0.13 s for lean mice, P<0.05; F(1,6)=48.54, and 3.74±0.15 for HFD mice) (Figure 1d). Importantly, the replacement of leptin (two injections in 48 h i.p.; 5 mg/kg) in ob/ob mice restored the thermal noxious latency (4.92±0.35 s for leptin-injected ob/ob mice vs 7.22±0.131 s at 10 min for ob/ob mice, P<0.05; F(1,7)=7.95), whereas the hormone did not exert any significant effect in lean mice (3.8±0.4 s for leptin-injected lean mice vs 4.3±0.4 s for vehicle-injected lean mice) (Figure 1e). As (1) obese mice have increased OX-A signaling in many output areas of the lateral hypothalamus (Cristino et al, 2013), (2) the PAG is one of such output areas (see later), and (3) OX-A activation of OX1-R causes antinociceptive effects (Ohno-Shosaku and Kano, 2014; Azhdari-Zarmehri et al, 2013, 2014), we wanted to investigate whether the ‘normoalgesic' phenotype of HFD mice was due to concurrent and opposing actions of hypothalamic OX1-R activation and elevated circulating leptin. Indeed, acute i.p. injection of these mice with the OX1-R antagonist SB334867 (60 mg/kg, 20 min after baseline recording) significantly decreased the thermal latency 20 and 30 min post injection (1.55±0.25 s for HFD+SB vs 4.45±0.15 s at 30 min for HFD+vehicle mice, P<0.005; F(1,8)=84.3) (Figure 1f), which is reminiscent of the hyperalgesic effect of SB334867 observed in otherwise ‘hypoalgesic' ob/ob mice (Supplementary Figure S2). Conversely, acute i.p. injection of HFD mice with a leptin receptor antagonist (5 mg/kg, 15 min after baseline recording) increased the thermal latency 10 min after treatment until the end of the observation (7.4±0.8 s for HFD+anti-leptin receptor vs 4.45±0.15 s at 30 min for HFD+vehicle mice, P<0.005; F(1,8)=54.9). These data confirm our hypothesis of concurring tonic pronociceptive and antinociceptive actions of leptin and OX-A in HFD mice. Control experiments revealed the following: (1) the leptin receptor antagonist did not exert any significant effect in lean mice (4.1±0.4 s for anti-leptin-injected lean mice vs 3.8±0.09 s for vehicle-injected lean mice) (Figure 1g); (2) the injection of leptin (5 mg/kg i.p.), or of the CB1 inverse agonist AM251 (1 mg/kg i.p.) (which was tested because CB1 receptors also stimulate the DAP (Ohno-Shosaku and Kano, 2014; Hohmann et al, 2005) and was found to do so in ob/ob mice as well (see below)), also did not significantly alter thermal nociceptive latency in lean mice as compared with basal levels (Figure 1e–g); and (3) injection of the OX1-R antagonist SB334867 (i.p., 60 mg/kg) significantly reduced thermal latency in lean mice as compared with vehicle-treated lean mice (lean+SB: 1.14±0.19 s vs lean+vehicle: 2.56±0.30 s after 20 min of treatment; P<0.05; F(1,8)=79.5).

DAGLα/OX1-R-Positive vlPAG Neurons Projecting to RVM Receive Either CB1 Inhibitory or OX-A Excitatory Synapses

We analyzed the orexinergic innervation of vlPAG neurons involved in the DAP from cohorts of wt and ob/ob mice (B6.Cg-Lepob/J) and C57Bl6 mice on SFD or HFD. We found a dense plexus of orexinergic (OX-A) fibers in the PAG of obese mice (ob/ob and HFD) in comparison with lean (wt and SFD) mice (Figure 2a–e). These fibers were distributed with roughly comparable density in the PAG area, the exception being the dorsolateral and ventrolateral PAG of obese mice, in which a considerably stronger OX-A immunoreactivity occurred in comparison with lean mice and was lowered by leptin injection in ob/ob but not in HFD mice (Figure 2f and g).

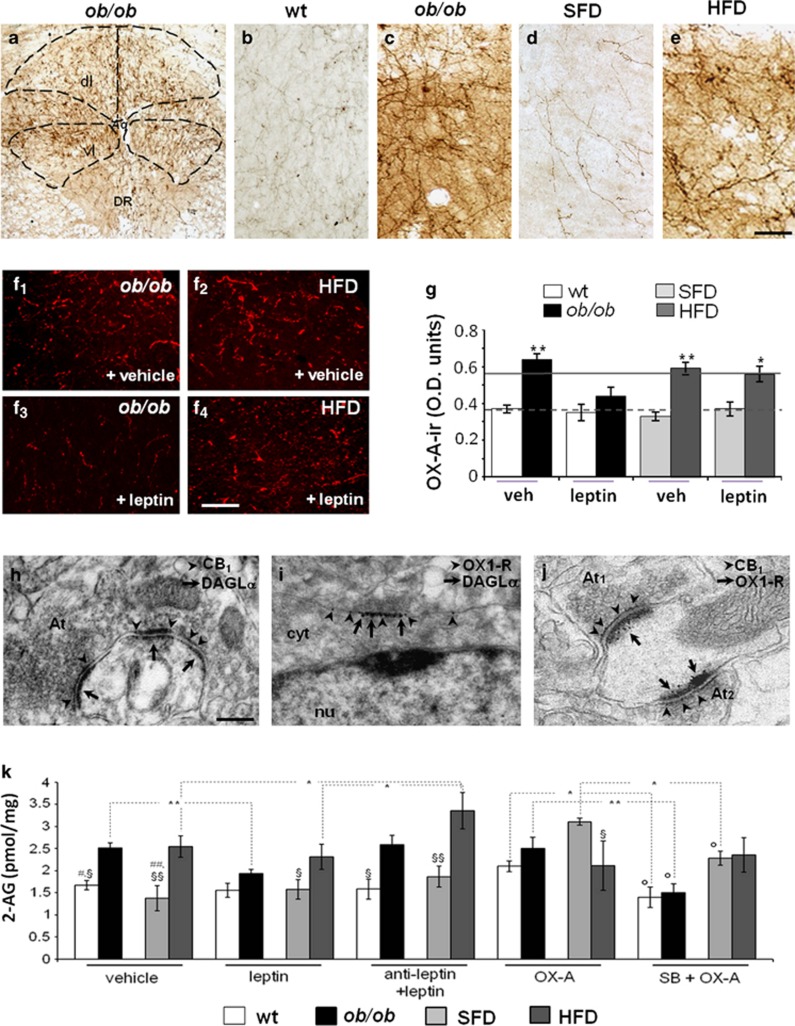

Figure 2.

OX-A immunoreactivity increases in the fibers projecting to the vlPAG of obese mice together with the increase in 2-AG levels. (a–e) Representative peroxidase-based OX-A staining in the vlPAG of obese ob/ob (a and c) and wt (b), standard-fat diet (SFD) (d), and HFD (e) mice showing the dense plexus of orexinergic fibers being more immunoreactive in the vlPAG of obese mice than in lean mice. (f1–f4) Leptin-mediated lowering of OX-A immunodensity in ob/ob (f3) but not in HFD (f4) mice. (g) Bar graphs of OX-A peroxidase-based optical density (OD) of 24 h fasted, wt and ob/ob mice (bars); average values for wt mice (dotted line) and ob/ob mice (solid line) fed ad libitum are shown as reference. Data are from n=3 mice per group fed ad libitum and are means±SD; * P<0.05 (P=0.02; F(1,12)=15.34) by comparison of HFD with SFD leptin-injected mice and **P<0.005 (P=0.002; F(1,19)=33.24) by comparison of ob/ob with wt or of HFD with SFD vehicle-injected mice. Statistical analysis was performed by two-way ANOVA followed by the Bonferroni post hoc test. (h) Electron microscopy immunogold detection of symmetrical, putative inhibitory, axodendritic synapses between an axon terminal (At), which exhibits marked CB1 immunogold labeling (arrowheads) in the presynaptic membrane, and a membrane showing DAGLα accumulation (arrows) at the edges of the postsynaptic density. (i) Accumulation of OX1-R metal particles (arrowheads) within the perikaryon (cyt;) of a neuron expressing DAGLα concentrated on the somatic membrane (arrows). (j) Dense accumulation of OX1-R immunogold (arrows) in a spine receiving two symmetrical, putative inhibitory, CB1-immunolabeled synapses (arrowheads) from different axon terminals (At1 and At2). CB1 is densely accumulated at the edges of presynaptic membrane specializations. Aq, aqueduct; At, axon terminal; cyt, cytoplasm; dl, dorsolateral area; DR, dorsal raphe; vl, ventrolateral area; nu, nucleus. [Scale bar: 300 μm (a), 50 μm (b,e), 100 μm (f), 0.6 μm (g–i).] (k) Enhancement of 2-AG levels in obese (ob/ob and HFD) mice compared with lean (wt and SFD) mice is reversed after leptin administration (24 h, 5 mg/kg) in ob/ob and not in HFD mice and is mimicked by OX-A administration in lean mice (2 h, 40 mg/kg). Data are means±SD; n=3 mice per group. *P<0.01 and **P<0.001 for the indicated comparisons. §P<0.05 and §§P<0.005 by comparison of wt with ob/ob or of SFD with HFD mice, per each treatment. #P<0.05 by comparison of wt+vehicle with wt+OX-A and ##P<0.005 by comparison of SFD+vehicle with SFD+OX-A. oP<0.05 by comparison of wt+SB+OX-A or ob/ob+SB+OX-A or SFD+SB+OX-A with each matched OX-A-treated sample. Statistical analysis was performed by two-way ANOVA followed by the Bonferroni post hoc test.

The neuronal circuitry of the antinociceptive PAG–RVM pathway was traced by microinjection of the fluorescent retrograde tracer cholera toxin-β (CTβ, Alexa Fluor 488; Life Technologies, USA) into the RVM of wt and ob/ob mice, which produced a dense retrograde labeling in the majority of vlPAG neurons (67±6%). The CTβ labeling was exploited as a cellular hallmark to identify the subset of DAGLα/OX1-R-, CB1/synaptophysin-, and OX-A/synaptophysin-expressing neurons from adjacent PAG sections (Supplementary Figure S3). We found that the vast majority of OX1-R-positive neurons were labeled with CTβ (wt: 88.2±8.6% and ob/ob: 82.2±6.5%). In this population, a very similar percentage of neurons were found to be labelled with CTβ/OX-A/synaptophysin (wt: 88.4±9.4% and ob/ob: 81.8±7.8%, Supplementary Figure S3A), CTβ/CB1/synaptophysin (wt: 84.3±6.1% and ob/ob: 84.5±8.3%, Supplementary Figure S3B), and CTβ/DAGLα/OX1-R (87±7% in wt and 79±5% in ob/ob, Supplementary Figure S3C). Finally, by double immunogold electron microscopy we found that DAGLα-expressing neurons receive symmetrical, putative inhibitory, CB1-positive synapses more frequently than they do asymmetrical, putative excitatory ones (86.5±8.4%=inhibitory vs 27.3±6.4%=excitatory) (Figure 2h). DAGLα immunogold labeling was found just beneath the membrane of somata and proximal dendrites of OX1-R-expressing neurons (Figure 2i). Many somata and proximal dendrites of OX1-R-expressing neurons were found to receive symmetrical (ie, putative inhibitory) synapses from CB1-expressing axons (Figure 2j). This morphological evidence supported a model of DAP circuitry as illustrated in the scheme (Figure 1c).

OX-A Enhances 2-AG Levels in the vlPAG of Obese Mice Through OX1-R Activation

2-AG levels were higher in the vlPAG of obese mice (ob/ob and HFD) as compared with lean mice (wt and SFD). Notably, leptin administration lowered 2-AG levels in ob/ob but not in lean or HFD mice. Leptin effect in ob/ob mice was reversed by antagonism of leptin receptor, which in HFD mice increased 2-AG levels. OX-A injection significantly increased 2-AG levels in lean mice, whereas it was ineffective in obese mice. The selective OX1-R antagonist, SB334867, counteracted the effect of OX-A in lean mice and lowered 2-AG levels in ob/ob mice (Figure 2k). No differences in anandamide levels were found between obese mice and their lean counterparts after vehicle, leptin, or OX-A treatment (data not shown). These data suggest the following: (i) elevation of 2-AG in the vlPAG of ob/ob and HFD mice is attributable to OX-A-mediated activation of OX1-R, which in turn is enhanced by leptin signaling deficiency (Figure 2f and g) in the lateral hypothalamus (Cristino et al, 2013); and (ii) unlike the hypothalamus (Di Marzo et al, 2001), leptin does not reduce 2-AG levels in the vlPAG of lean mice despite the presence of its receptors in this brain area (Patterson et al, 2011).

Activity of OFF (Antinociceptive) and ON (Pronociceptive) Cells in the RVM of Obese Mice

Recording of RVM ON and OFF cell activity is a widely used functional method to study DAP. Indeed, OFF cells suppress, and ON cells facilitate, nociception. Here, we evaluated how the absence of leptin or its overproduction, in ob/ob and HFD mice, respectively, affects DAP in terms of ongoing and evoked activity of ON and OFF cells of the RVM.

We found that, in agreement with the above-mentioned thermal nociception threshold data, ob/ob mice show a reduced ON cell ongoing activity (Figure 3a and b) and increased OFF cell ongoing activity (Figure 3d and e) in comparison with lean mice, whereas no changes were observed in ON and OFF cell activity of HFD mice. Moreover, in ob/ob mice, we found onset increase, either for ON or for OFF cells, compared with wt (Figure 3c and f), together with reduction of ON cell-evoked frequency (ob/ob mice: 7.5±0.02 Hz vs wt mice: 19.3±0.04 Hz) and OFF cell duration of inhibition (ob/ob mice: 4.2±0.03 s vs wt mice: 11.6±0.09 s), without changes in ON cell duration of excitation (ob/ob mice: 5.3±0.02 s vs wt mice: 4.26±0.04 s.

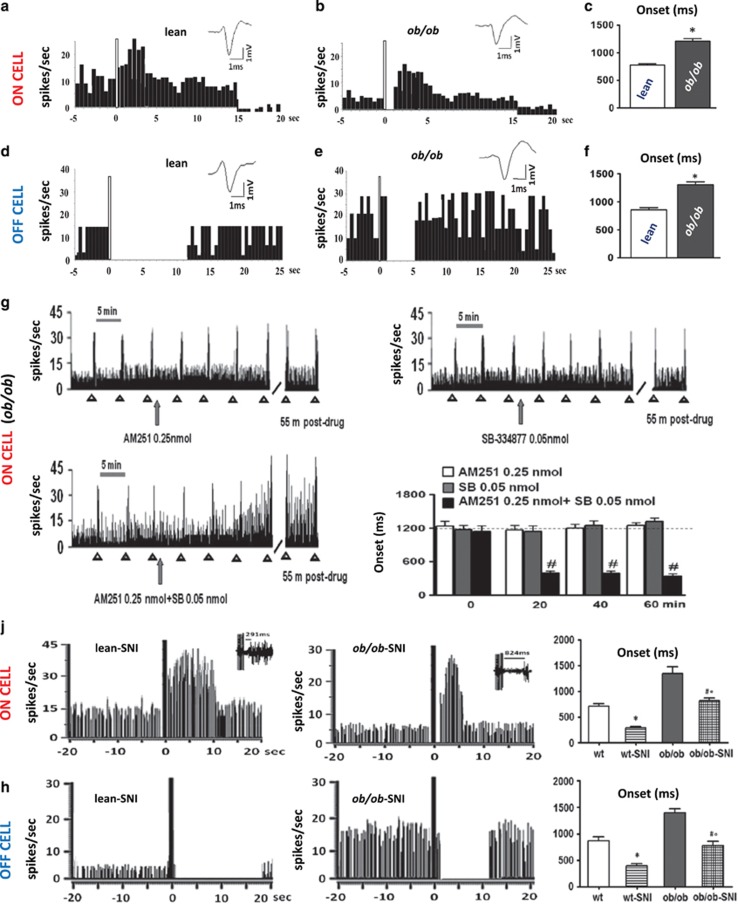

Figure 3.

Electrophysiological recordings of RVM ON (pronociceptive) and OFF (antinociceptive) cell activity in vivo in wt and ob/ob mice. (a–c) Representative peristimulus time histogram (PSTH) of noxious-stimuli-evoked activity of identified ON cells in lean and obese ob/ob mice. Twenty seconds of recording is shown. ob/ob mice showed a reduced ON cell spontaneous activity compared with lean mice (3.5±0.2 spikes/s for ob/ob mice vs 7.9±1.3 spikes/s for lean mice) and a reduced evoked excitation. In particular, the onset was increased (1208±50 ms for ob/ob mice vs 778±22.70 ms for lean mice). (d–f) Representative PSTH of noxious-stimuli-evoked activity of identified OFF cells in lean and obese ob/ob mice. Twenty-five seconds of recording is shown. For this and all other PSTHs, the bin width is 500 ms; the white bar represents the time of mechanical stimulation. Bar graphs showing neuronal population data of evoked activity, measured by analyzing the onset of excitation (n=10–12 neurons/group). Mice lacking leptin (ob/ob) showed increased OFF cell spontaneous activity compared with lean mice (11.25±1.9 spikes/s for ob/ob mice vs 8.3±1.0 spikes/s for lean mice) and a reduced evoked inhibition. Each bar represents the mean±SEM of n= 6 mice per group. *P<0.05 indicates the difference between ob/ob and lean mice by two-way ANOVA test followed by Bonferroni post hoc test. (g) Representative rate histograms illustrate the pronociceptive effect exerted by the combination of AM251 and SB334867 that, when microinjected alone at the same dose, did not exert any changes on the spontaneous and evoked activity of ON cells. Sixty minutes of recording is shown. Each bar represents the mean±SEM of n=6–8 mice per group and one neuron was recorded for each animal. #P<0.05 indicates significant difference of ob/ob+AM251 0.25 nmol+SB 0.05 nmol vs ob/ob+AM251 0.25 nmol and ob/ob+ SB 0.05 nmol. The dashed line represents the ob/ob basal value. P values indicate statistically significant differences by two-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni post hoc test. (j) Representative rate histograms of firing frequencies and noxious-stimuli-evoked activity of identified ON cells in lean-SNI and ob/ob-SNI mice 7 days after the spared nerve injury (SNI). Forty seconds of continuous recording is shown. (h) Representative rate histograms of firing frequencies and noxious-stimuli-evoked activity of identified OFF cells in lean-SNI and ob/ob-SNI mice. Forty seconds of continuous recording is shown. Each bar represents the mean±SEM of n=6 mice per group, and for each animal two neurons were recorded. *P<0.05 indicates significant difference between wt-SNI and wt mice; #°P<0.05 indicates significant difference between ob/ob-SNI and wt-SNI and ob/ob mice. P value was considered significant using one-way ANOVA followed by the Bonferroni post hoc test.

In agreement with a role of enhanced OX-A/2-AG levels in DAP in ob/ob mice, and with the previously described evidence indicating that both CB1 and OX-1 R receptors are endogenous enhancers of DAP (Ohno-Shosaku and Kano, 2014; Hohmann et al, 2005), we found the following: (1) the inverse CB1 agonist, AM251, caused an enhancement of ON cell (Supplementary Figure S4A, B, D–F) and a reduction of OFF cell (Supplementary Figure S4H–J) activity in these mice, while exerting a similar pronociceptive-like effect in lean mice only at the highest dose tested (1 nmol) (Supplementary Figure S4D–F, H–J); and (2) the OX-1 R selective antagonist SB334867 (0.05 nmol) exerts a pronociceptive-like effect by increasing ON cell and decreasing OFF cell activity in lean mice (Supplementary Figure S5A, D–F and S5G, J, K). Importantly, in ob/ob mice, in agreement with the overexpression of OX-A-releasing fibers projecting to the vlPAG, a double dose of SB334867 (0.1 nmol) was necessary to increase ON cell and decrease OFF cell activity, thereby exerting again a pronociceptive-like effect (Supplementary Figure S5B–F and S5H–K).

We reasoned that the fact that, in ob/ob mice, the dose of AM251 sufficient to modify cell activity was half of that used for lean mice (0.5 nmol) could be linked to the inverse agonist properties of this compound and to the possible occurrence of partial CB1 receptor adaptation in the vlPAG of these obese mice (desensitization) mediated by G-protein-coupled receptor (GPCR) kinase (GRK)-mediated phosphorylation of activated receptors and subsequent β-arrestin2 binding (Nguyen et al, 2012). Accordingly, like in other regions of the brain (Breivogel et al, 2013), we found here also in the PAG an extensive CB1R co-distribution with β-arrestin2, suggesting that β-arrestin2 might regulate CB1 signaling in this area. CB1 and β-arrestin2 co-distribution was higher in the vlPAG of ob/ob mice as compared with wt mice (ob/ob: 24.2±4.6% and wt: 11.2±2.7% of vlPAG area, analyzed from n=15 sections for mouse; n=3 mice per group), which is suggestive of stronger induction of CB1 internalization in the former mice. This phenomenon is likely due to the higher levels of 2-AG in these obese mice, and in fact it could be induced also in wt mice by OX-A in a manner sensitive to SB334867, which in turn tended to reduce CB1 binding to β-arrestin2 in ob/ob mice (Supplementary Figure S4C). Thus, in view of the inverse agonist nature of AM251 (as opposed to SB334867, which is a neutral antagonist), this stronger CB1 internalization might favor the action of AM251 and explain, at least in part, the higher sensitivity of ob/ob mice to this compound (Supplementary Figure S4B, D–J).

Importantly, we also found preliminary evidence of a possible synergistic effect between OX1-R and CB1 at stimulating DAP. In fact, sub-effective doses of SB334867 (0.05 nmol) and AM251 (0.25 nmol), when co-injected in ob/ob mice, produced an enhancement of ON cell activity and significantly reduced their onset (388±46.41 ms vs basal values 1200±109.5 ms, P=0.003; F(1,13)=5.58) (Figure 3g).

We also investigated whether the antinociceptive behavior mediated by ON and OFF cells in obese mice occurs in a model of pathological pain. Therefore, we applied spared nerve injury (SNI) to the sciatic nerve to reproduce peripheral neuropathy (Decosterd and Woolf, 2000) in wt and ob/ob mice. In agreement with previous data (Maeda et al, 2009), we found that ob/ob mice do not develop tactile allodynia and, therefore, we recorded for the first time ON and OFF cells of the RVM in these mice. Lean wt SNI mice showed an increased and decreased ongoing and evoked activity of ON and OFF cells, respectively, as compared with sham-operated lean wt animals. In agreement with the absence of tactile allodynia, SNI ob/ob mice showed ON and OFF cell activity comparable to those of sham-operated wt mice (Figure 3j and h). Both neuropathic lean and ob/ob mice showed a relative increase in both spontaneous and evoked activity of ON cells compared with the respective sham-operated lean and ob/ob mice. In particular, the onset decreased (280±38 ms for wt-SNI mice vs 703±61.5 ms for wt mice, P<0.005; F(1,19)=36.52, and 870±71.5 ms for ob/ob-SNI mice vs 1380±62 ms for ob/ob mice, P=0.00; F(1,20)=29.36); the duration of excitation increased in wt-SNI mice compared with wt mice but not in ob/ob mice (8.8±1s for wt-SNI mice vs 3.8±0.8 s for wt mice, P<0.005; F(1,20)=14.52); and the evoked frequency increased significantly in both wt-SNI and ob/ob-SNI mice (26±1.2 Hz for wt-SNI mice vs 18±0.5 Hz for wt mice, P<0.005; F(1,19)=33.46, and 15.9±1.3 Hz for ob/ob-SNI mice vs 9.2±0.4 Hz for ob/ob mice, P<0.005; F(1,20)=21.49) (Figure 3j). Both neuropathic lean and ob/ob mice showed relatively increased spontaneous and evoked activity in OFF cells compared with the respective lean and ob/ob mice. In particular, the duration of inhibition increased in both wt-SNI and ob/ob-SNI mice compared with wt (17.6±1 s for wt-SNI mice vs 10±1.5 s for wt mice, P<0.005; F(1,19)=15.80) and ob/ob mice (11.6±0.9 s for ob/ob-SNI mice vs 3.9±0.2 s for ob/ob mice, P<0.005; F(1,20)=81.10), respectively. Finally, the onset of inhibition decreased in both wt-SNI and ob/ob-SNI mice compared with wt (380±51 ms for wt-SNI mice vs 820±44 ms for wt mice, P<0.005; F(1,19)=41.40) and ob/ob mice (790±54 ms for ob/ob-SNI mice vs 1400±60 ms for ob/ob mice, P<0.005; F(1,20)=55.40), respectively (Figure 3h).

We could not perform ON and OFF cell recordings in HFD mice following pharmacological treatments, as in these animals the cells were too sensitive to the treatment and/or the concomitant mechanical noxious stimuli. Therefore, we could not evaluate why, in HFD mice, ON and OFF cells of the RVM exhibit the same activity as in lean STD mice. Noteworthy, the plasma levels of leptin were not different between sham-operated HFD mice and HFD-SNI mice (Supplementary Figure S1B).

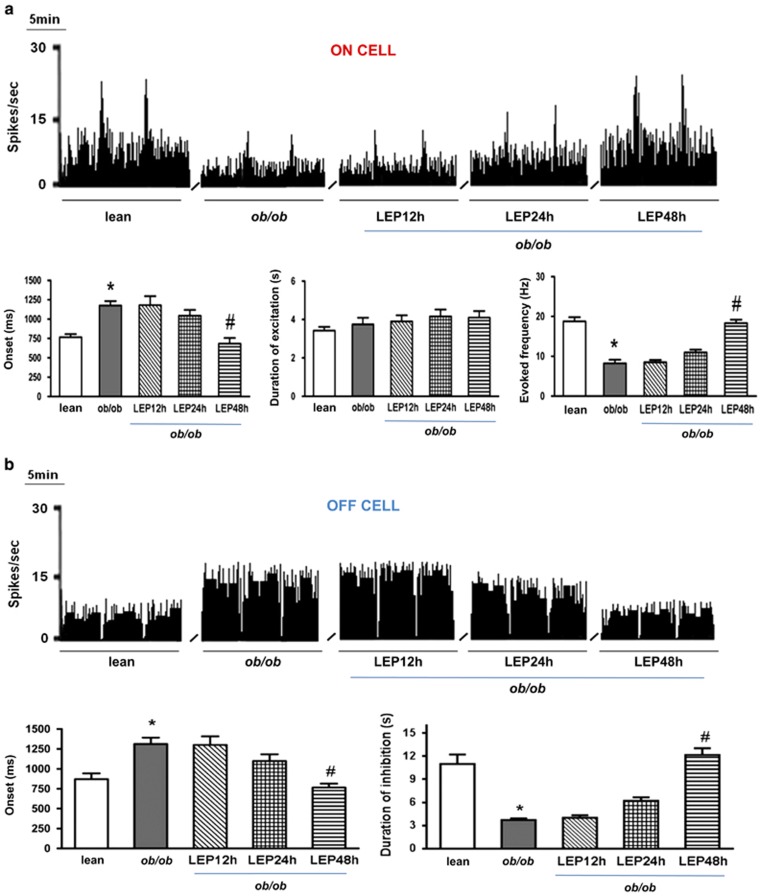

Indeed, the above experiments in obese mice as well as the behavioral experiments presented in Figure 1 indicate that enhanced OX-A→2-AG→CB1 signaling in the vlPAG of obese mice, due to lack of leptin (as in ob/ob mice) or leptin sensitivity in the hypothalamus (as in HFD mice) (Cristino et al, 2013), activates DAP and produces overt (as in ob/ob mice) or latent (as in HFD mice) hypoalgesia. Therefore, to investigate whether the changes of ON and OFF cell activity were, in fact, due to leptin deficiency and, in turn, to unbalance orexin/cannabinoid cross talk, we injected leptin in ob/ob mice and measured the activity of these cells. We found a partial normalization of ON and OFF cell parameters after single i.p. injection (1 day after injection) and a complete recovery of both ON and OFF cell activity after 48 h and two leptin injections (5 mg/kg, i.p.). In particular, neuronal population data of ON cell-evoked activity showed that leptin administration in ob/ob mice reduced the onset (682±4.79 vs ob/ob basal values 1176±56.36 ms, P<0.005; F(1,13)=66.22) and increased the evoked frequency (18.33±0.87 Hz vs ob/ob basal values 8.5±0.56 Hz, P=0.00; F(1,13)=95.02), whereas it did not change the duration of excitation (Figure 4a). Neuronal population data of OFF cell-evoked activity showed that leptin administration reduced the onset (766±48.54 ms vs ob/ob basal values 1300±109.5 ms, P<0.005; F(1,11)=22.09) and increased the duration of inhibition (12.17±0.87 s vs ob/ob basal values 3.72±0.22 s, P<0.005; F(1,11)=76.34) in ob/ob mice (Figure 4b).

Figure 4.

Effect of intraperitoneal injection of leptin on the spontaneous and noxious-evoked activity of RVM ON and OFF cells in ob/ob mice. (a) Representative rate histograms illustrate the effect of leptin administration on the spontaneous and evoked activity of ON cells, which was significant after 48 h. Each bar represents the mean±SEM of n=6–8 mice per group, and one neuron was recorded for each animal. *P<0.05 indicates significant difference between ob/ob mice and wt mice and #P<0.05 indicates significant difference between ob/ob+leptin 48 h and ob/ob mice by one-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni's post hoc test. (b) Same as in a, but for spontaneous and evoked activity of OFF cells.

OX-A Exerts a Tonic Depolarizing Effect on vlPAG Neurons of ob/ob Mice

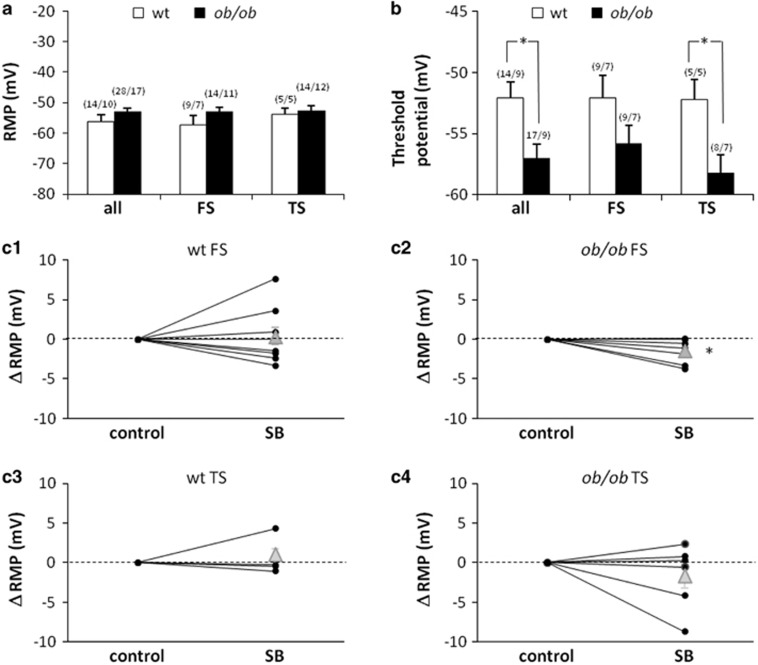

OX-A supplemented to brain slices of wt rats has been shown to exert an overall excitatory effect on PAG neurons. This influence is mostly due to a direct depolarization of resting membrane potential (RMP), but also depends on a 2-AG-mediated enhancement of excitatory and reduction of inhibitory synaptic potentials (Ho et al, 2011). In the present paper, we describe higher levels of OX-A in the vlPAG of ob/ob mice compared with wt, and link the difference to the preferential activation of OFF cells (and reduction of ON cells) in the RVM. It is thus possible that, in ob/ob animals, a high level of OX-A exerts a tonic depolarizing/activating influence on vlPAG neurons, in particular on those projecting to RVM. To test this hypothesis we performed patch-clamp recordings of RMP in vlPAG neurons identified as projecting to RVM on the basis of their intrinsic membrane properties and further categorized as fast- and transient-spiking neurons (FS and TS, respectively) (Supplementary Figure S6) (Park et al, 2010; see also Supplemental Material). We found that FS-vlPAG neurons of ob/ob animals were tonically depolarized by the OX-A present in the milieu. In fact, although FS and TS neurons of both genotypes showed comparable RMP values (Figure 5a), still blocking OX1-R (SB334867, 12 μM) hyperpolarized the RMP specifically in ob/ob FS-vlPAG neurons (−1.4±0.53 mV on average, n=7, P<0.05) (Figure 5c2), with no effect on the other categories/genotypes (Figure 5c1, 3, 4). This result is in line with the effect described in wt PAG neurons by Ho et al. (2011)—namely, a depolarization >1 mV induced by OX-A added in vitro. The effect was present only in 45% of their recordings, which the authors performed blindly—ie, with no distinction between neurons: this restriction is well explained by our finding that only FS neurons (and not TS neurons) are sensitive to the OX1-R blocker (in ob/ob animals). Moreover, when tested with brief depolarizing current pulses, ob/ob vlPAG neurons appeared to have a more negative threshold for action potential initiation (ie, they are more excitable) compared with wt, although this trend reached a statistical significance only for TS-vlPAG neurons (Figure 5b), with no difference in the frequencies of evoked spikes (data not shown). Blocking OX1-R had no effect on firing threshold and evoked spikes frequency (data not shown).

Figure 5.

Intrinsic membrane properties in vlPAG neurons projecting to RVM. Resting membrane potential (RMP) (a) and action potential initiation threshold (b) of ob/ob and wt vlPAG neurons. Data are mean±SEM for the whole population of recorded neurons (all) and for the fast (FS) and transient (TS) spiking subpopulations. Significant differences are indicated with asterisks: *P<0.05. In brackets: number of neurons/number of mice. (c) Effect of block of OX-A receptors (SB334867, 12 μM). SB causes hyperpolarization of ob/ob FS neurons only (c2, P=0.05) and no effect in wt FS neurons (c1) or in TS neurons (both wt c3 and ob/ob c4). Data are presented as amount (mV) of variation of RMP value after treatment with SB. Black dots: data from individual neurons. Gray triangles: means±SEM.

In conclusion, we recorded indirect functional evidence that the vlPAG of ob/ob mice has a higher concentration of OX-A than does wt vlPAG. Moreover, the lower firing threshold of TS-vlPAG neurons suggests that at least a part of the projections to RVM are more active in ob/ob than in wt mice. We found no significant difference in the firing frequency of wt and ob/ob neurons at rest (data not shown).

DISCUSSION

Heterosynaptic endocannabinoid spread induced by activation of OX1-R receptors in the vlPAG suppresses inhibitory transmission in this area (Ho et al, 2011). Here, we suggest that this mechanism is involved in the potentiation of the PAG–RVM–spinal dorsal horn DAP during leptin signal deficiency. Both models used here, ob/ob mice and mice with HFD-induced obesity, which differ by being completely leptin deficient and showing leptin signal deficiency only in the ARC, respectively, exhibited vlPAG OX-A and 2-AG levels higher than in the corresponding lean mice. This alteration, and the ensuing disinhibition of vlPAG output neurons, is at the basis of the hypoalgesic behavior of obese (ob/ob) mice and explains the recent observation, published during the preparation of this manuscript, that attenuated pain response of these mice is affected by leptin (Rodgers et al, 2014). More importantly, these observations provide a possible mechanism for the different pain perception thresholds often observed in patients with obesity or eating disorders, in which leptin signaling is disrupted. However, and intriguingly, in this study HFD mice exhibited hypoalgesia only following blockade of leptin receptors, possibly due to the concomitant proalgesic action, exerted outside the DAP, of elevated leptin in these mice.

A first original result of our study was to provide, through retrograde tracing, morphological studies and in vivo electrophysiological measurements in the vlPAG and RVM, the anatomical substrate on which endocannabinoid and orexinergic circuitries interact in the vlPAG, as hitherto investigated only by in vitro patch-clamp approaches in lean animals (Ho et al, 2011). On the basis of our morphological data, we identified the neuronal sites of 2-AG biosynthesis from DAGLα, and action at CB1 receptors, within the vlPAG–RVM circuitry, which underlie the nociception afforded by OX-A signaling in this brain area. Presynaptic CB1 receptors located on inhibitory, presumably GABAergic, interneurons inhibit the activity of the latter, thereby disinhibiting excitatory (presumably glutamatergic) output neurons of the vlPAG. In ob/ob mice, overstimulation of OX1-R receptors, and subsequently DAGLα (both proteins being located on these same vlPAG output neurons), produces an enhancement of 2-AG levels and subsequent overstimulation of presynaptic CB1 receptors, with consequent further disinhibition of vlPAG output neurons, thereby activating RVM OFF cells and reinforcing analgesia. At the same time, RVM ON cells are inhibited by the same vlPAG output neurons, possibly via GABAergic interneurons located in the RVM. Thus, we have shown that activation of the OX1-R/DAGLα/2-AG/CB1 pathway in the vlPAG may relieve pain because coupled to facilitation of the DAP. Perhaps more importantly, we have revealed that this mechanism is enhanced by defective leptin signaling.

One limitation of studies using the ob/ob mouse is that the mutation causing lack of leptin production is very seldom found in humans, whereas most forms of human obesity, although associated with reduced hypothalamic leptin receptor activity subsequent to elevated leptin production from the adipose tissue (Ogier et al, 2002), cannot be attributed to leptin alone. Indeed, we have found here that, despite their dysregulation of OX-A and endocannabinoid signaling in the vlPAG being similar to that observed in ob/ob mice, HFD obese mice exhibit neither reduced-pain sensitivity nor altered descending antinociceptive signaling. However, we also provided data suggesting that this lack of hypoalgesia is not due to the lack of OX-A-mediated analgesia in HFD mice, but rather due to the concomitant proalgesic action of leptin, likely exerted at extrahypothalamic receptors. Furthermore, impaired leptin signaling is also associated with other conditions, such as anorexia nervosa and binge eating, which can be accompanied by reduced-pain perception (Lautenbacher et al, 1990; Yamamotova et al, 2009, 2012) as is food deprivation due to poor social conditions (Vaez Mahdavi et al, 2012).

It is known that 2-AG levels in the hypothalamus are reduced by leptin, and therefore are enhanced under conditions of hypothalamic leptin signaling deficiency typical of both genetically or diet-induced obesity (Di Marzo et al, 2001; Cristino et al, 2013). More recently, we demonstrated that impaired leptin signaling, specifically in the ARC of the hypothalamus, causes the ‘rewiring' of orexinergic neurons of the lateral hypothalamus, thus leading to CB1-mediated retrograde disinhibition, instead of inhibition, of such neurons, with subsequent increase of OX-A trafficking and release to target areas. This phenomenon is reversed by acute leptin administration in ob/ob mice but not in HFD mice, which are characterized by specific LeptR insensitivity in the ARC (Cristino et al, 2013). In agreement with these previous data, we have found here that leptin replacement is ineffective at reducing 2-AG levels in the vlPAG of HFD mice in spite of their LeptR sensitivity in this region. This suggests that the ARC has a master regulatory role in determining OX-A-induced endocannabinoid overactivity in the vlPAG. Nevertheless, in the presence of leptin, a LeptR antagonist did increase 2-AG levels in the vlPAG of HFD mice, suggesting that strongly elevated systemic leptin levels in these mice do tonically counteract to some extent OX-A-induced elevation of vlPAG 2-AG levels. As LeptR is present in the PAG (Patterson et al, 2011), this might be due to tonic leptin inhibition of 2-AG biosynthesis in this brain area, although occurring in HFD but not in lean mice, and might provide an additional explanation as to why HFD mice exhibit pain sensitivity similar to wt and SFD mice, unless administered with a LeptR antagonist.

Descending antinociception can be induced by directly exciting the vlPAG or by inhibiting intrinsic GABAergic tone (disinhibition) (Behbehani et al., 1990). The finding that intra-vlPAG microinjection of SB334867 reduced tail-flick latency in mice confirms the vlPAG as an important site of action for orexin-induced supraspinal antinociception (Ho et al, 2011; Azhdari-Zarmehri et al, 2011). In ob/ob mice, both the OX-A-mediated reduced-pain sensitivity and enhanced OFF–decreased ON cell activity were markedly reduced by treatment with AM251 at a dose inactive in wt mice, thus strongly suggesting that the CB1-mediated disinhibition produced by retrograde 2-AG after OX1-R receptor activation has a major role in OX-A-induced antinociception in the vlPAG. This suggestion is further supported by the generalized increased excitability of RVM-projecting output neurons in ob/ob mouse vlPAG slices as compared with wt mice. However, a direct postsynaptic depolarizing effect of OX-A in the vlPAG, which would also lead to increased output neuronal firing, may have contributed to the antinociceptive phenotype of ob/ob mice. This contention is supported by the seemingly synergistic effect of SB334867 and AM251 on ON and OFF cell activity, which suggests the existence of not completely overlapping mechanisms for the two compounds. Excitation of the PAG might also induce antinociception via ascending pathways (Morgan et al, 1989), and the possibility that OX-A might excite the PAG to induce analgesia through such pathways cannot be ruled out. However, the present finding that OX-A depolarizes vlPAG neurons projecting to the RVM retrogradely traced by fluorophore provides direct evidence indicating that this neuropeptide excites the PAG to activate the DAP.

In conclusion, we have reported here morphological, biochemical, pharmacological, and in vivo and in vitro electrophysiological data suggesting that, under conditions of leptin signaling deficiency, typical of obesity but also of some eating disorders, endocannabinoid signaling is enhanced in the vlPAG via orexinergic neuron overactivity engendered in the hypothalamus (Cristino et al, 2013), and contributes, via disinhibition of excitatory output neurons to the RVM, to facilitation of the DAP and reduced-pain perception. The understanding of whether or not this mechanism is responsible, at least in part, for altered pain thresholds in individuals with obesity and eating disorders, who are characterized by increased circulating endocannabinoid and OX-A levels (Engeli et al, 2005; Monteleone et al, 2005; Bronsky et al, 2011), will require specific studies in patients with these conditions—eg, by analyzing, by PET imaging, the activity of their brainstem CB1 receptors (Horti and Van Laere, 2008) in response to pain stimuli.

Funding and Disclosure

This work was supported by Intramural Funding of Endocannabinid Research Group at the Institute of Biomolecular Chemistry of CNR to LC and VD and by grants from MIUR-FIRB ‘Futuro in Ricerca' (RBFR126IGO to LL). The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We are particularly grateful to Professor Ken Mackie (Indiana University) who kindly provided the DAGLα antibody.

Author contributions

LC, LL, SM and VD designed the study and wrote the manuscript. LC conducted the immunohistochemistry and immunogold study at confocal and electron transmission microscopy. LL and SB performed in vivo electrophysiology. SB and RI performed neurotracing experiments. TB and GB performed the in vitro patch-clamp electrophysiology. GM performed ELISA assays, western blotting and co-immunoprecipitation assays. FP performed the LC/MS determination of endocannabinoids levels. All the authors analyzed and discussed data.

Footnotes

Supplementary Information accompanies the paper on the Neuropsychopharmacology website (http://www.nature.com/npp)

Supplementary Material

References

- Azhdari-Zarmehri H, Esmaeili M-H, Sofiabadi M, Haghdoost-Yazdi H (2013). Orexin receptor type-1 antagonist SB334867 decreases morphine-induced antinociceptive effect in formalin test. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 112: 64–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azhdari-Zarmehri H, Semnanian S, Fathollahi Y, Erami E, Khakpay R, Azizi H et al (2011). Intra-periaqueductal gray matter microinjection of orexin-A decreases formalin-induced nociceptive behaviors in adult male rats. J Pain 12: 280–287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azhdari-Zarmehri H, Semnanian S, Fathollahi Y (2014). Orexin-A microinjection into the rostral ventromedial medulla causes antinociception on formalin test. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 122: 286–290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behbehani M-M, Jiang M-R, Chandler S-D, Ennis M (1990). The effect of GABA and its antagonists on midbrain periaqueductal gray neurons in the rat. Pain 40: 195–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breivogel CS, Puri V, Lambert JM, Hill DK, Huffman JW, Razdan RK (2013). The influence of beta-arrestin2 on cannabinoid CB1 receptor coupling to G-proteins and subcellular localization and relative levels of beta-arrestin1 and 2 in mouse brain. J Recept Signal Transduct Res 33: 367–379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bronsky J, Nedvidkova J, Krasnicanova H, Vesela M, Schmidtova J, Koutek J et al (2011). Changes of orexin A plasma levels in girls with anorexia nervosa during eight weeks of realimentation. Int J Eat Disord 44: 547–552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cristino L, Becker T, Di Marzo V (2014). Endocannabinoids and energy homeostasis: an update. Biofactors 40: 389–397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cristino L, Busetto G, Imperatore R, Ferrandino I, Palomba L, Silvestri C et al (2013). Obesity-driven synaptic remodeling affects endocannabinoid control of orexinergic neurons. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 110: 2229–2238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Decosterd I, Woolf C-J (2000). Spared nerve injury: an animal model of persistent peripheral neuropathic pain. Pain 87: 149–158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng Y, Scherer P-E (2000). Adipokines as novel biomarkers and regulators of the metabolic syndrome. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1212: E1–E19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Marzo V, Goparaju SK, Wang L, Liu J, Bátkai S, Járai Z et al (2001). Leptin-regulated endocannabinoids are involved in maintaining food intake. Nature 410: 822–825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engeli S, Böhnke J, Feldpausch M, Gorzelniak K, Janke J, Bátkai S et al (2005). Activation of the peripheral endocannabinoid system in human obesity. Diabetes 54: 2838–2843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foo H, Mason P (2009). Analgesia accompanying food consumption requires ingestion of hedonic foods. J Neurosci 29: 13053–13062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goforth PB, Leinninger GM, Patterson CM, Satin LS, Myers MG Jr (2014). Leptin acts via lateral hypothalamic area neurotensin neurons to inhibit orexin neurons by multiple GABA-independent mechanisms. J Neurosci. 34: 11405–11415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregg LC, Jung KM, Spradley JM, Nyilas R, Suplita RL, Zimmer A et al (2012). Activation of type 5 metabotropic glutamate receptors and diacylglycerol lipase-α initiates 2-arachidonoylglycerol formation and endocannabinoid-mediated analgesia. J Neurosci 32: 9457–9468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho YC, Lee HJ, Tung LW, Liao YY, Fu SY, Teng SF et al (2011). Activation of orexin 1 receptors in the periaqueductal gray of male rats leads to antinociception via retrograde endocannabinoid (2-arachidonoylglycerol)-induced disinhibition. J Neurosci 31: 14600–14610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hohmann AG, Suplita RL, Bolton NM, Neely MH, Fegley D, Mangieri R et al (2005). An endocannabinoid mechanism for stress-induced analgesia. Nature 435: 1108–1112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horti A-G, Van Laere K (2008). Development of radioligands for in vivo imaging of type 1 cannabinoid receptors (CB1) in human brain. Curr Pharm Des 14: 3363–3383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lautenbacher S, Pauls A-M, Strian F, Pirke K-M, Krieg C (1990). Pain perception in patients with eating disorders. Psychosom Med 52: 673–682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis J-W, Cannon J-T, Liebeskind J-C (1980). Opioid and nonopioid mechanisms of stress analgesia. Science 208: 623–625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maeda T, Kiguchi N, Kobayashi Y, Ikuta T, Ozaki M, Kishioka S (2009). Leptin derived from adipocytes in injured peripheral nerves facilitates development of neuropathic pain via macrophage stimulation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106: 13076–13081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monteleone P, Di Lieto A, Tortorella A, Longobardi N, Maj M (2000). Circulating leptin in patients with anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa or binge-eating disorder: relationship to body weight, eating patterns, psychopathology and endocrine changes. Psychiatry Res 94: 121–129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monteleone P, Matias I, Martiadis V, De Petrocellis L, Maj M, Di Marzo V (2005). Blood levels of the endocannabinoid anandamide are increased in anorexia nervosa and in binge-eating disorder, but not in bulimia nervosa. Neuropsychopharmacology 30: 1216–1221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan M-M, Sohn J-H, Liebeskind JC (1989). Stimulation of the periaqueductal gray matter inhibits nociception at the supraspinal as well as spinal level. Brain Res 502: 61–66 (1989). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen PT, Schmid CL, Raehal KM, Selley DE, Bohn LM, Sim-Selley LJ et al (2012). β-arrestin2 regulates cannabinoid CB1 receptor signalling and adaptation in a central nervous system region-dependent manner. Biol Psychiatry 71: 714–724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogier V, Ziegler O, Mejean L, Nicolas J-P, Stricker-Krongrad A (2002). Obesity is associated with decreasing levels of the circulating soluble leptin receptor in humans. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 26: 496–503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohno-Shosaku T, Kano M (2014). Endocannabinoid-mediated retrograde modulation of synaptic transmission. Curr Opin Neurobiol 29C: 1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papežová H, Yamamotová A, Uher R (2005). Elevated pain threshold in eating disorders: physiological and psychological factors. J Psychiatr Res 39: 431–438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park C, Kim JH, Yoon BE, Choi EJ, Lee CJ, Shin HS (2010). T-type channels control the opioidergic descending analgesia at the low threshold-spiking GABAergic neurons in the periaqueductal gray. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 107: 14857–14862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson C-M, Leshan R-L, Jones J-C Jr, Myers M-G (2011). Molecular mapping of mouse brain regions innervated by leptin receptor-expressing cells. Brain Res 1378: 18–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peyron C, Tighe DK, van den Pol AN, de Lecea L, Heller HC, Sutcliffe JG et al (1998). Neurons containing hypocretin (orexin) project to multiple neuronal systems. J Neurosci 18: 9996–10015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds D-V (1969). Surgery in the rat during electrical analgesia induced by focal brain stimulation. Science 164: 444–445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodgers HM, Liban S, Wilson LM (2014). Attenuated pain response of obese mice (B6.Cg-lepob) is affected by aging and leptin but not sex. Physiol Behav 123: 80–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakurai T, Amemiya A, Ishii M, Matsuzaki I, Chemelli RM, Tanaka H et al (1998). Orexins and orexin receptors: a family of hypothalamic neuropeptides and G protein-coupled receptors that regulate feeding behavior. Cell 92: 573–585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsujino N, Sakurai T (2009). Orexin/hypocretin: a neuropeptide at the interface of sleep, energy homeostasis, and reward system. Pharmacol Rev 61: 162–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaez Mahdavi M-R, Khalili Najafabadi M, Ghazanfari T (2012). The effect of social stress on chronic pain perception in female and male mice. PLoS One 7e47218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- van den Pol A-N, Gao X-B, Obrietan K, Kilduff T-S, Belousov A (1998). Presynaptic and postsynaptic actions and modulation of neuroendocrine neurons by a new hypothalamic peptide, hypocretin/orexin. J Neurosci 18: 7962–7971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe S, Kuwaki T, Yanagisawa M, Fukuda Y, Shimoyama M (2005). Persistent pain and stress activate pain-inhibitory orexin pathways. Neuroreport 16: 5–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamotova A, Kmoch V, Papezova H (2012). Role of dehydroepiandrosterone and cortisol in nociceptive sensitivity to thermal pain in anorexia nervosa and healthy women. Neuro Endocrinol Lett 33: 401–405. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamotova A, Papezova H, Uher R (2009). Modulation of thermal pain perception by stress and sweet taste in women with bulimia nervosa. Neuro Endocrinol Lett 30: 237–244. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yilmaz P, Diers M, Diener S, Rance M, Wessa M, Flor H. (2010). Brain correlates of stress-induced analgesia. Pain 151: 522–529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.