Abstract

Mutations in genes encoding subunits of the epithelial Na+ channel (ENaC) can cause early onset familial hypertension, demonstrating the importance of this channel in modulating blood pressure. It remains unclear whether other genetic variants resulting in subtler alterations of channel function result in hypertension or altered sensitivity of blood pressure to dietary salt. This study sought to identify functional human ENaC variants to examine how these variants alter channel activity and to explore whether these variants are associated with altered sensitivity of blood pressure to dietary salt. Six-hundred participants of the Genetic Epidemiology Network of Salt Sensitivity (GenSalt) study with salt-sensitive or salt-resistant blood pressure underwent sequencing of the genes encoding ENaC subunits. Functional effects of identified variants were examined in a Xenopus oocyte expression system. Variants that increased channel activity included three in the gene encoding the α-subunit (αS115N, αR476W, and αV481M), one in the β-subunit (βS635N), and one in the γ-subunit (γL438Q). One α-subunit variant (αA334T) and one γ-subunit variant (βD31N) decreased channel activity. Several α-subunit extracellular domain variants altered channel inhibition by extracellular Na+ (Na+ self-inhibition). One variant (αA334T) decreased and one (αV481M) increased cell surface expression. Association between these variants and salt sensitivity did not reach statistical significance. This study identifies novel functional human ENaC variants and demonstrates that some variants alter channel cell surface expression and/or Na+ self-inhibition.

Keywords: epithelial sodium channel, Genetic Epidemiology Network of Salt Sensitivity, salt-sensitive hypertension, sodium self-inhibition, two-electrode voltage clamp

hypertension is a major contributor to cardiovascular disease (25, 33) and is the leading risk factor for mortality globally, with 9.4 million attributable deaths in 2010 (26). Among modifiable determinants of hypertension, Na+ consumption ranks among the most significant (11, 51). Elevated Na+ consumption is associated with higher blood pressure (18, 21, 28, 30, 31) and contributed to 1.6 million cardiovascular deaths in 2010 (35). However, individuals vary in blood pressure sensitivity to dietary Na+ (21, 32, 50), and genetic background likely plays a significant role in determining salt sensitivity (5). Almost all monogenetic hypertensive syndromes involve decreased urinary Na+ excretion by the kidney (7, 49), highlighting the importance of the kidney in regulating blood pressure and suggesting that dysregulation of renal Na+ handling likely contributes to non-Mendelian hypertension.

The epithelial Na+ channel (ENaC) is expressed in the kidney's late distal convoluted tubule, connecting tubule, and collecting duct, where it plays a key role in the absorption of Na+ from tubular fluid (20, 34). Liddle syndrome, characterized by early onset hypertension and hypokalemia, occurs as a consequence of mutations that reduce ENaC ubiquitination, increasing the number of channels at the cell surface and increasing channel open probability (Po) (13, 23, 44, 45). Human ENaC is comprised of three structurally related subunits, α, β, and γ, encoded by SCNN1A (chromosome 12), SCNN1B (chromosome 16), and SCNN1G (chromosome 16), respectively. Sibling-pair studies have previously revealed linkage disequilibrium between blood pressure and microsatellite markers on chromosome 16, near SCNN1B and SCNN1G (37, 52). Several studies have shown that selected common ENaC variants are associated with increases in blood pressure or changes in the salt sensitivity of blood pressure (8, 17, 27, 38, 47, 54, 55).

The Genetic Epidemiology Network of Salt Sensitivity (GenSalt) study searched for genetic polymorphisms associated with changes in sensitivity of blood pressure to dietary sodium (16, 55). This study examined subjects living in six rural villages in northern China. This region was selected due to its minimal ethnic and environmental heterogeneity and because individuals in this region have a habitually high dietary Na+ intake, approaching 5.2 g/day (16). Study subjects underwent a dietary intervention that included measurements of blood pressure on a low- and high-salt diet. Subjects with blood pressure that was unusually salt sensitive or unusually salt resistant were identified for comparative sequencing of SCNN1A, SCNN1B, and SCNN1G. We asked whether identified ENaC variants have functional effects by expressing them in Xenopus oocytes and comparing amiloride-sensitive current amplitudes. For variants that alter channel activity, we further asked whether these changes occur as a consequence of changes in cell surface expression or of changes in Na+ self-inhibition, a process wherein extracellular Na+ binds the channel and decreases channel Po (12, 14, 29, 42). Finally, we examined whether gain-of-function variants were significantly more common in salt-sensitive study subjects.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Identification of ENaC variants.

Study participants of Han ancestry (1,906 subjects) were selected for a dietary intervention that was approved by Institutional Review Boards at relevant institutions and by the National Human Genomic Resource Administration of China, as previously described (16). Briefly, individuals were excluded from the study if they had stage 2 hypertension, were receiving antihypertensive medications, or if they had secondary hypertension, cardiovascular, or chronic kidney disease. During a 3-day baseline assessment, blood pressures were measured while participants consumed their usual diet. Subjects were then administered a low-salt diet (51.3 mmol/day Na+) for 7 days followed by a high-salt diet (307.8 mmol/day) for 7 days, with continued monitoring of blood pressures. The 300 subjects with the highest and 300 subjects with the lowest mean arterial blood pressure responses were designated as salt sensitive and salt resistant, respectively, and were selected for targeted gene sequencing. SCNN1A, SCNN1B, and SCNN1G were sequenced using the VariantSEQr system (Applied Biosystems). Nonsynonymous exonic variants were individually tested for association with salt sensitivity using either a Chi square or Fisher's exact test (when an expected cell count was <5). Due to the low power of single marker analyses to identify rare and low-frequency variants influencing salt sensitivity, aggregate rare variant analysis was conducted using the optimal unified sequence kernel association test (SKAT-O). SKAT-O encompasses burden tests and SKAT by deriving an optimal test statistic under a range of scenarios in which variants may be protective or deleterious (24). Before SKAT-O testing, low-frequency and rare variants (minor allele frequency <5%) were aggregated according to gene and predicted gain-of-function or loss-of-function status.

Site-directed mutagenesis and expression of human ENaC in Xenopus oocytes.

cDNAs encoding human α-, β-, and γ-ENaC subunits were mutated using the QuickChange II XL mutagenesis kit (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA) to introduce selected variants. cDNAs were transcribed in vitro using the T7 or SP6 mMessage mMachine kit (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY). The synthesized cRNAs (2 ng/subunit) were injected into stage V–VI Xenopus laevis oocytes. Oocytes were incubated at 18°C in modified Barth's saline [MBS: 88 mM NaCl, 1 mM KCl, 2.4 mM NaHCO3, 0.3 mM Ca(NO3)2, 0.41 mM CaCl2, 0.82 mM MgSO4, 15 mM HEPES, 10 μg/ml streptomycin sulfate and sodium penicillin, and 100 μg/ml gentamycin sulfate, pH 7.4] for 24–48 h before electrophysiological recording at room temperature. The protocol for harvesting oocytes from X. laevis was approved by the University of Pittsburgh's Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Recording and analysis of currents in Xenopus oocytes.

Whole cell currents were recorded using standard two-electrode voltage-clamp techniques with an Axoclamp 900A microelectrode amplifier with a Digidata 1440A analog-to-digital converter (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA). Currents were recorded at room temperature (20–24°C), using the Clampex 10 Data Acquisition Module (Molecular Devices), with a sampling frequency of 1 KHz, a transmembrane electrical potential of −100 mV, and filtered at 20 Hz. Oocytes were perfused via gravity perfusion, with solution changes controlled via an eight-channel ValveLink 8.2 perfusion controller (AutoMate Scientific, Berkeley, CA). Standard 110 mM Na+ recording solution was 110 mM NaCl, 2 mM KCl, 2 mM CaCl2, and 10 mM HEPES, pH 7.4. Perfusion with 10 μM amiloride allowed subtraction of baseline (non-ENaC-mediated) currents. For examination of relative current amplitudes, currents were normalized to currents from a similar number of wild-type channels recorded from the same batch of oocytes on the same day. Normalized current amplitudes from multiple recording days were then averaged for comparison. Statistical significance was examined using a two-tailed Student's t-test.

Measurement of Na+ self-inhibition.

To assess Na+ self-inhibition, currents were recorded in 1 mM Na+ solution (1 mM NaCl, 109 mM N-methyl-d-glucamine, 2 mM KCl, 2 mM CaCl2, and 10 mM HEPES, pH 7.4), with abrupt transition to 110 mM Na+ solution. The ratio of steady-state current in 110 mM Na+ solution to the peak current that occurred immediately following transition to high-Na+ solution was used to represent the magnitude of Na+ self-inhibition. Kinetics of current decay were examined by fitting with a single exponential equation using Clampfit 10.4.

ENaC cell surface expression.

ENaC surface expression in oocytes was examined by coexpressing α- and γ-subunits with a FLAG epitope-tagged β-subunit, as previously described (9, 10). One day following cRNA injection of oocytes, amiloride-sensitive currents were assessed using two-electrode voltage clamp, as above. Oocytes were then incubated for an additional day at 18°C. Subsequent steps were performed on ice, except for measurement of chemiluminescence, which was performed at room temperature (20–24°C). Oocytes were incubated for 30 min in antibiotic-free MBS and 1% bovine serum albumin (MBS/BSA) and then for 1 h with MBS/BSA with 1 μg/ml mouse anti-FLAG antibody (M2; Sigma). After being washed in cold MBS/BSA, oocytes were incubated for 1 h in MBS/BSA with 1 μg/ml horseradish peroxidase-coupled goat anti-mouse IgG (Jackson ImmunoResearch, WestGrove, PA). Oocytes were washed in cold MBS/BSA and then BSA-free MBS and transferred to a 96-well plate. SuperSignal ELISA Femto Maximum Sensitivity Substrate (100 μl; Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL) was added to each well. Relative light units (RLU) were quantified using a GloMax-Multi+ Detection System (Promega, Madison, WI). The background mean RLU from wells with no cells was subtracted from the RLU for ENaC-injected oocytes.

RESULTS

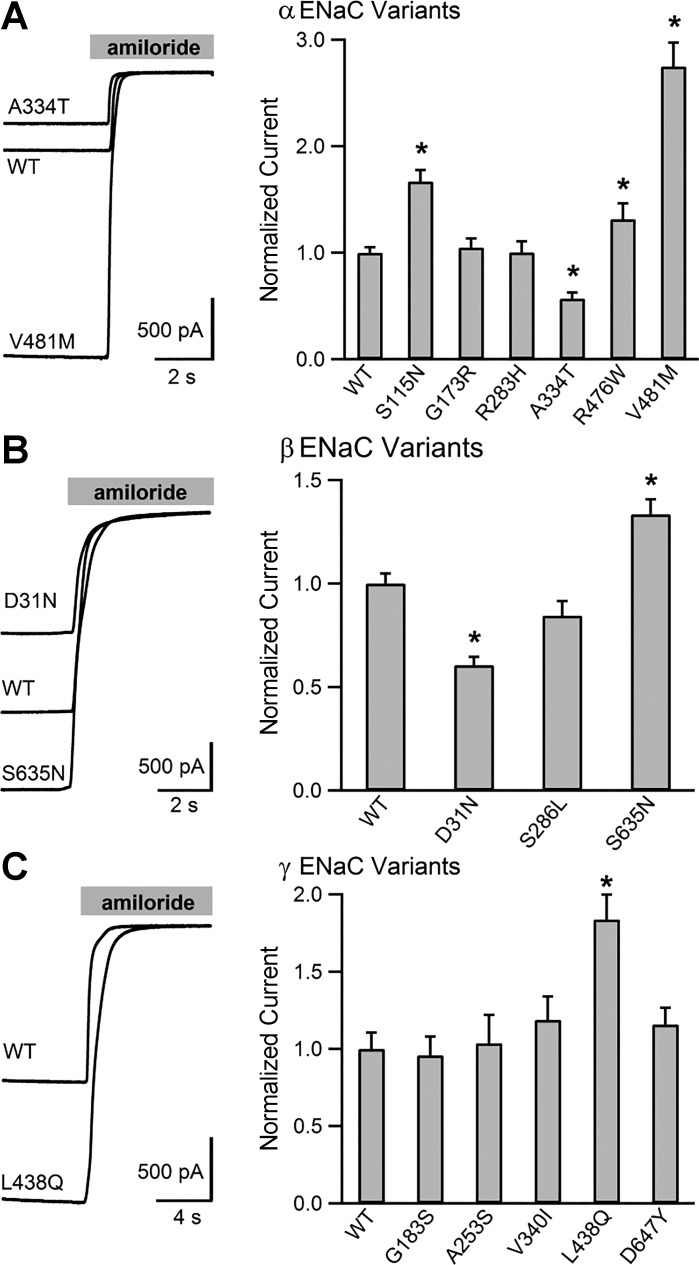

Sixteen nonsynonymous ENaC variants were identified in 600 GenSalt participants (Table 1). Of these, eight were in the α-subunit, three in the β-subunit, and five in the γ-subunit. We generated human ENaC cDNAs containing these variants and examined the activity of resulting channels in the Xenopus oocyte expression system. Whole cell amiloride-sensitive currents of wild-type or mutant channels were measured using two-electrode voltage clamp (Fig. 1). Within the α-subunit, three variants increased channel activity: S115N, R476W, and V481M by 1.67 ± 0.11-, 1.37 ± 0.10-, and 2.75 ± 0.22-fold, respectively (P < 0.001 for each variant vs. wild type). One variant, A334T, resulted in a reduction in amiloride-sensitive Na+ currents to 0.57 ± 0.06 of wild type (P < 0.001 vs. wild type), similar to previous findings (2). Neither G173R nor R283H significantly altered currents compared with wild type, with normalized mean currents of 1.05 ± 0.08 and 1.00 ± 0.10, respectively (P = 0.62 and 0.98). We and others have previously examined T663A (1, 2, 36, 40, 48, 53), and we did not functionally characterize it further. Another α-subunit variant, P52R, is present in an mRNA splice variant that adds 59 amino acids to the NH2-terminus of the protein. This residue is not present in the commonly studied isoform (NM_001038.5) used as our control and was not assayed (6, 46). We examined three β-subunit variants. Of these, S635N increased currents 1.33 ± 0.07-fold compared with wild type, and D31N reduced currents to 0.61 ± 0.04 of that observed for wild-type channels (P < 0.001 for both). S286L did not significantly affect whole cell Na+ currents (0.85 ± 0.07; P = 0.06). Of five γ-subunit variants examined, only L438Q significantly changed channel activity, increasing relative amiloride-sensitive Na+ currents 1.77 ± 0.15-fold (P < 0.001 vs. wild type). The γ-subunit variants G183S, A253S, V340I, and D647Y did not significantly alter whole cell Na+ currents.

Table 1.

Nonsynonymous ENaC variants identified in GenSalt

| Gene Exon* | Location | rs Number | Nucleotide Substitution | Amino Acid Substitution* | Minor Allele Frequency | Single Marker P Value† |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SCNN1A | Chr 12p13 | |||||

| Exon 2 | 6483972 | rs377074479 | C>G | P52R | 0.002 | 0.25 |

| Exon 2 | 6483606 | G>A | S115N | 0.001 | 0.49 | |

| Exon 3 | 6472753 | rs55859427 | G>C | G173R | 0.001 | 1.00 |

| Exon 4 | 6471244 | rs368942111 | G>A | R283H | 0.001 | 1.00 |

| Exon 6 | 6464581 | rs11542844 | G>A | A334T | 0.181 | 0.32 |

| Exon 11 | 6458506 | rs113622727 | C>T | R476W | 0.001 | 1.00 |

| Exon 12 | 6458386 | rs201693951 | G>A | V481M | 0.004 | 0.22 |

| Exon 13 | 6457062 | rs2228576 | G>A | T663A | 0.456 | 0.91 |

| SCNN1B | Chr 16p12 | |||||

| Exon 2 | 23360011 | rs370777535 | G>A | D31N | 0.001 | 1.00 |

| Exon 5 | 23379257 | rs142531781 | C>T | S286L | 0.002 | 1.00 |

| Exon 13 | 23392103 | rs13306629 | G>A | S635N | 0.003 | 0.50 |

| SCNN1G | Chr 16p12 | |||||

| Exon 3 | 23200921 | rs5736 | G>A | G183S | 0.008 | 0.34 |

| Exon 4 | 23203811 | G>T | A253S | 0.001 | 0.50 | |

| Exon 6 | 23208689 | rs774394259 | G>A | V340I | 0.001 | 1.00 |

| Exon 9 | 23224017 | rs756463117 | T>A | L438Q | 0.003 | 1.00 |

| Exon 13 | 23226779 | rs72647543 | G>T | D647Y | 0.001 | 1.00 |

ENaC, epithelial Na+ channel; GenSalt, Genetic Epidemiology Network of Salt Sensitivity; rs number, reference SNP identification number.

Exon and residue numbering as per common mRNA isoforms: for SCNN1A, NM_001038.5, encoding a 669-amino acid α−subunit; for SCNN1B, NM_000336.2, encoding a 640-amino acid β−subunit; for SCNN1G NM_001039.3 encoding a 649-amino acid γ subunit.

P value for single marker test (Chi square or Fisher's exact for sparse data). Includes heterozygous and homozygous participants.

Fig. 1.

Multiple human epithelial Na+ channel (ENaC) variants alter channel activity. The effect of nonsynonymous variants in the α-, β-, and γ-subunits on amiloride-sensitive currents. Left, select representative current traces recorded in oocytes injected with cRNAs encoding the three ENaC subunits. By convention, inward currents are downward. Gray bar at the top represents perfusion with amiloride (10 μM). Right, bar graphs showing mean current amplitudes normalized to wild-type currents measured on the same day. N ≥ 37 oocytes for each variant and wild type (WT). Error bars represent SE. *Statistically significant differences in current amplitude compared with wild type (P < 0.05) based on 2-tailed Student's t-test.

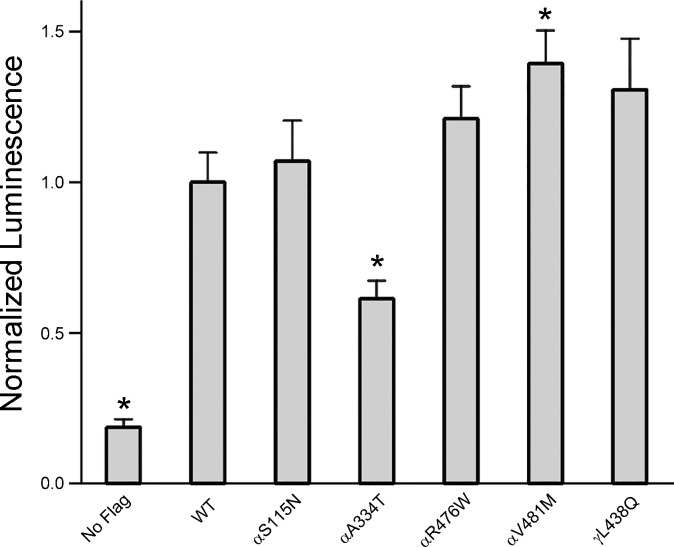

Changes in ENaC activity may reflect changes in cell surface number, Po, and/or single channel conductance. To determine whether variants that altered ENaC activity were associated with changes in ENaC surface expression, we examined surface expression of selected mutant and wild-type channels using a β-subunit with an extracellular FLAG tag, in conjunction with a chemiluminescence-based assay. Of the five variants examined, a significant increase in ENaC surface expression was only seen with αV481M (P < 0.01 vs. wild-type), a variant associated with an increase in whole cell Na+ currents (Fig. 2). A reduction in surface expression was seen with αA334T (P < 0.01 vs. wild type), a variant associated with a reduction in Na+ currents. For three of the variants that were associated with an increase in ENaC functional expression (αS115N, αR476W, and γL438Q), levels of surface expression were similar to wild type (P > 0.05).

Fig. 2.

Effects of functional ENaC variants on channel surface expression. Cell surface expression of ENaC in oocytes was determined by coexpressing Genetic Epidemiology Network of Salt Sensitivity (GenSalt) ENaC variants or wild type with a β-subunit containing a FLAG epitope tag. Oocytes were incubated with an antibody against FLAG, followed by a horseradish peroxidase-linked secondary antibody. Relative chemiluminescence was compared between wild type and the variants. No FLAG, background luminescence from oocytes expressing ENaC with no FLAG epitope tag (N = 27 oocytes for No FLAG control and >40 for wild type and variants). *Statistically significant difference from WT (P < 0.01).

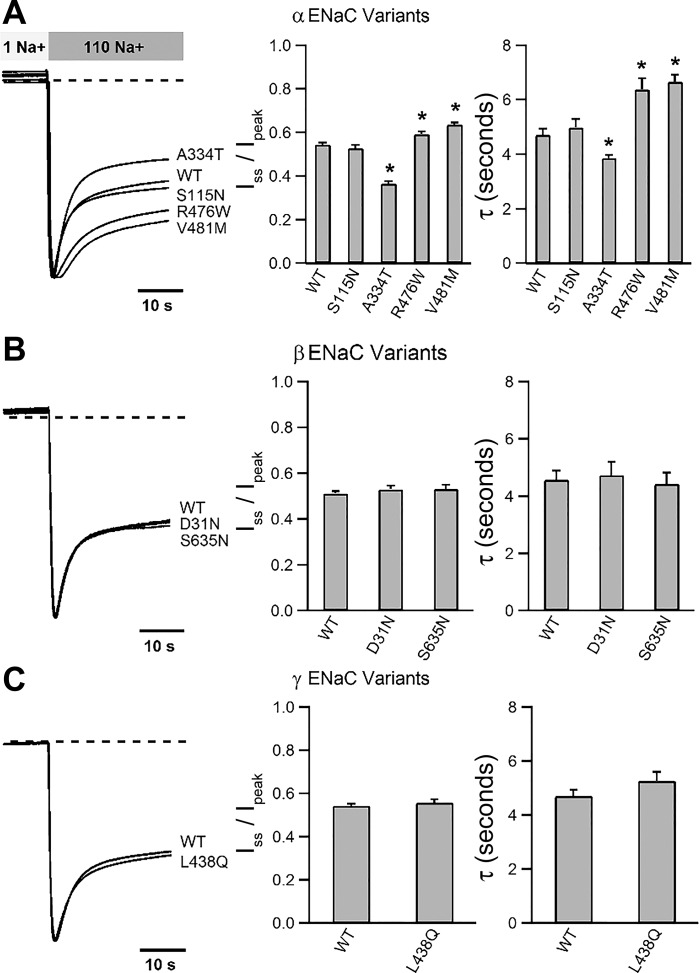

ENaC is not only permeable to Na+ but also modulated by it. Na+ binds the channel extracellular domain and impairs activity by promoting an allosteric reduction in channel Po (12, 14, 19, 29, 39, 42). This process, referred to as Na+ self-inhibition, can be examined experimentally by bathing ENaC-expressing oocytes in a low-concentration (1 mM) Na+ bath to allow channels to adopt a higher Po state, then abruptly increasing the extracellular Na+ concentration. The resulting rise in chemical-driving force transiently increases inward Na+ current. Channels then undergo Na+ self-inhibition, with a decline in inward current amplitude reflecting a reduction in channel Po. We assessed whether functional ENaC variants identified in GenSalt participants altered Na+ self-inhibition (Fig. 3). Two variants exhibited reduced Na+ self-inhibition (αR476W and αV481M), and one variant exhibited enhanced Na+ self-inhibition (αA334T), compared with wild-type ENaC (P < 0.01). Other variants exhibited Na+ self-inhibition that was similar to wild type.

Fig. 3.

Effects of ENaC variants on Na+ self-inhibition. The Na+ self-inhibition response was examined by rapidly transitioning ENaC-expressing oocytes from 1 to 110 mM extracellular Na+ solution. Left, representative current traces showing an initial increase in inward current due to increased driving force, followed by a decay in current amplitude (Na+ self-inhibition). Traces were normalized to that of wild type for ease of comparison. Broken lines indicate the zero current levels. Bars in middle show mean steady-state currents normalized to peak currents (Iss/Ipeak). Increased Iss/Ipeak reflects reduced Na+ self-inhibition, whereas reduced Iss/Ipeak reflects enhanced Na+ self-inhibition. Right, bars represent time constants (τ) based on a fit of curves using a single exponential decay function. N = 6 for all recordings. Error bars represent SE. *Statistically significant difference from wild-type channels (P < 0.05).

The ENaC variants we studied were identified in the 300 subjects with the highest (salt-sensitive) and 300 subjects with the lowest (salt-resistant) responses to a high-Na+ diet. We examined whether ENaC variants with enhanced activity were more likely to be found in the salt-sensitive individuals and whether variants with reduced activity were more likely to be found in the salt-resistant individuals. As noted in Table 2, neither of these associations reached statistical significance.

Table 2.

Comparison of functional variants and salt sensitivity

| Variants | Salt-Sensitive Carriers | Salt-Resistant Carriers | P Value (Burden)a | P Value (SKAT)a | P Value (SKAT-O)a |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gain of function | 0.62 | 0.33 | 0.45 | ||

| αS115N | 1b | 0 | |||

| αR476W | 0 | 1f | |||

| αV481M | 4c | 1g | |||

| βS635N | 3 | 1 | |||

| γL438Q | 1d | 2h | |||

| Loss of function | 0.17 | 0.40 | 0.18 | ||

| αA334T | 98 | 86 | |||

| αT663A | 194 | 196 | |||

| βD31N | 1e | 0 |

SKAT, sequence kernel association test.

Aggregate analysis of gain-of-function and loss-of-function variants, separately.

The carrier of αS115N is a heterozygous carrier of αA334T and homozygous for αT663A.

Among the 4 salt-sensitive carriers of αV481M, 3 are heterozygous carriers of αT663A, the other is heterozygous for αA334T and homozygous for αT663A.

The salt-sensitive carrier of γL438Q is heterozygous for αT663A.

The carrier of βD31N is homozygous for βT663A.

The salt-resistant carrier of αR476W is homozygous for αA334 and heterozygous for αT663A.

The salt-resistant carrier of αV481M is homozygous for αT663A.

Salt-resistant carriers of γL438Q are heterozygous for either αT663A or αA334T.

The most common variants resulted in a loss of function, including αA334T with a minor allele frequency of 18% and αT663A with a minor allele frequency of 45.6% in this cohort. We asked if these common loss-of-function variants influenced whether individuals with rare gain-of function ENaC variants exhibited the salt-sensitive phenotype. Even when accounting for these common variants, the segregation of the rare gain-of-function variants with salt sensitivity did not reach statistical significance.

DISCUSSION

We examined whether ENaC variants in the GenSalt cohort altered ENaC activity. Of the 16 nonsynonymous ENaC variants identified in the 600 study participants, αT663A and αA334T are relatively common, with allele frequencies of 0.18 and 0.46, respectively. Consistent with previous findings (2), we found that αA334T reduces channel activity (2). We have previously examined the functional effects of the αT663A variant. We found that this variant decreases channel activity in the Xenopus oocyte expression system as a consequence of reduced cell surface expression (36, 40, 53). Although Ambrosius and colleagues did not observe the decrease in channel activity in Xenopus oocytes (1), Tong and colleagues observed similar effects in Chinese hamster ovary cells (48).

The present study identified novel relatively rare variants that altered ENaC activity. αV481M exhibited the most robust gain of function, increasing currents 2.7-fold. Other gain-of-function variants included αS115N, αR476W, βS635N, and γL438Q. A loss-of-function variant, βD31N, was also identified.

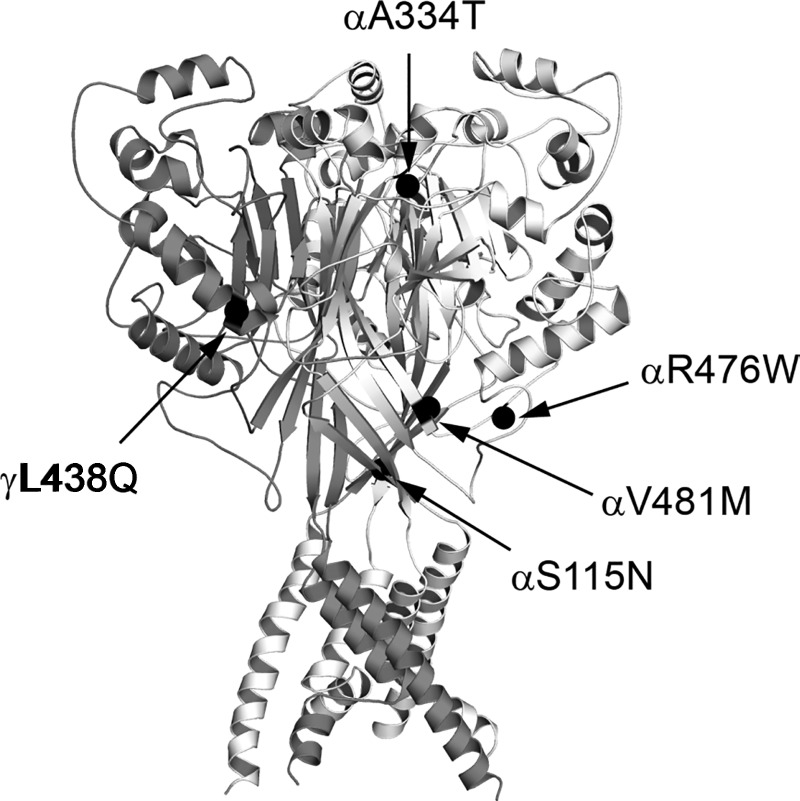

Three of these variants, αA334T, αR476W, and αV481M, altered the channel's Na+ self-inhibition response. While αR476W and αV481M increased Na+ currents in association with reducing Na+ self-inhibition, αA334T reduced Na+ currents and exhibited an enhanced Na+ self-inhibition response. Each of these sites is located in the extracellular region of the α-subunit (Fig. 4). Based on sequence alignments and a homology model of the α-subunit (20), αA334 is located within a loop connecting β-strands (β6–β7) in the palm and β-ball domains, respectively. Mutations at selected sites within this loop of the mouse α-subunit significantly alter Na+ self-inhibition (19). Because αA334T also reduced surface expression, a mutation at this site may affect ENaC stability and/or trafficking.

Fig. 4.

Locations of functional variants on a structural model of ASIC1. Extracellular and transmembrane domains of 3 chicken ASIC1 subunits were rendered as white, light gray, and dark gray ribbons (PDB ID: 4NYK) (15, 41). α-Carbons of ASIC1 residues homologous to human ENaC residues bearing functional variants are shown as black spheres. Homologous ASIC1/ENaC residues are T76/αS115, I225/αA334, E363/αR476, V368/αV481, and F351/γL438.

The αV481M variant led to a large increase in ENaC activity in association with suppressed Na+ self-inhibition, suggesting that the variant increases the channel's Po (29). We also found a modest increase in ENaC surface expression with this variant. αV481 is located at the start of β10, which is at the base of the palm domain (Fig. 4). Structural studies of ASIC1 suggest that this region undergoes a large conformational change during transition between closed and conducting states (3, 4). Given its location, it is not surprising that αV481M alters ENaC gating in response to extracellular Na+. αR476 is likely located within a loop connecting an α-helix and β-strand (α5–β10) in the thumb and palm domains, respectively. We previously reported that mutations at the β9–α4 loop connecting the palm and thumb domains significantly altered the Na+ self-inhibition and shear stress responses of mouse ENaC (43). Although it remains unclear whether variants modifying Na+ self-inhibition alter predisposition to salt-sensitive hypertension, it is clear that individuals in the general population express ENaC with varied sensitivity to extracellular Na+.

Seven variants did not show significant changes in ENaC activity in the current study. Genetic variations may affect protein function through multiple mechanisms, including altering the peptide sequence, mRNA levels, and translation efficiency. Our study focused on identifying functional human variants in the three ENaC subunits in the oocyte expression system. It is certainly possible that functional variants in other renal Na+ transporters, or variants in proteins that regulate these transporters, have a role in modifying salt sensitivity in humans.

Genetic mechanisms underlying the salt sensitivity of blood pressure remain to be elucidated (22). We asked whether gain-of-function variants were associated with salt sensitivity and loss-of-function variants were associated with salt resistance. Single variant analyses did not reveal individual variants with statistically significant association with salt sensitivity. However, these data do not rule out the possibility that altered ENaC function modifies salt sensitivity, a correlation that may be difficult to detect in the context of modest functional effects, a relatively small cohort, and the likelihood that study subjects may harbor alleles both protecting against and predisposing to salt sensitivity. More definitive results may require larger cohorts or animal modeling to examine functionally relevant ENaC variants in a homogenous genetic background.

GRANTS

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants R37-DK-051391 (T. R. Kleyman), K08-DK-110332 (E. C. Ray), T32-DK-061296 (E. C. Ray), P30-DK-079307 (T. R. Kleyman), U01-HL-072507 (J. He), R01-HL-087263 (J. He), and R01-HL-090682 (J. He) and American Heart Association Award 11SDG51300256 (T. N. Kelly).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

E.C.R., J.C., T.N.K., J.H., L.L.H., D.G., L.C.S., J.E.H., D.C.R., S.S., and T.R.K. analyzed data; E.C.R., J.C., T.N.K., J.H., L.L.H., D.G., L.C.S., J.E.H., D.C.R., S.S., and T.R.K. interpreted results of experiments; E.C.R. prepared figures; E.C.R. and T.R.K. drafted manuscript; E.C.R., T.N.K., J.H., L.L.H., D.G., J.E.H., D.C.R., S.S., and T.R.K. edited and revised manuscript; E.C.R., J.C., T.N.K., J.H., L.L.H., D.G., L.C.S., J.E.H., D.C.R., S.S., and T.R.K. approved final version of manuscript; J.C., L.L.H., L.C.S., and S.S. performed experiments; T.N.K., J.H., L.L.H., D.G., L.C.S., J.E.H., D.C.R., S.S., and T.R.K. conception and design of research.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ambrosius WT, Bloem LJ, Zhou L, Rebhun JF, Snyder PM, Wagner MA, Guo C, Pratt JH. Genetic variants in the epithelial sodium channel in relation to aldosterone and potassium excretion and risk for hypertension. Hypertension 34: 631–637, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Azad AK, Rauh R, Vermeulen F, Jaspers M, Korbmacher J, Boissier B, Bassinet L, Fichou Y, des Georges M, Stanke F, De Boeck K, Dupont L, Balascakova M, Hjelte L, Lebecque P, Radojkovic D, Castellani C, Schwartz M, Stuhrmann M, Schwarz M, Skalicka V, de Monestrol I, Girodon E, Ferec C, Claustres M, Tummler B, Cassiman JJ, Korbmacher C, Cuppens H. Mutations in the amiloride-sensitive epithelial sodium channel in patients with cystic fibrosis-like disease. Hum Muta 30: 1093–1103, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baconguis I, Bohlen CJ, Goehring A, Julius D, Gouaux E. X-ray structure of acid-sensing ion channel 1-snake toxin complex reveals open state of a Na(+)-selective channel. Cell 156: 717–729, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baconguis I, Gouaux E. Structural plasticity and dynamic selectivity of acid-sensing ion channel-spider toxin complexes. Nature 489: 400–405, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beeks E, Kessels AG, Kroon AA, van der Klauw MM, de Leeuw PW. Genetic predisposition to salt-sensitivity: a systematic review. J Hypertens 22: 1243–1249, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Berman JM, Brand C, Awayda MS. A long isoform of the epithelial sodium channel alpha subunit forms a highly active channel. Channels 9: 30–43, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Burke B, Gungadoo J, Marcano ACB, Newhouse SJ, Shiel J, Caulfield MJ, Munroe PB. Monogenic forms of human hypertension. In: Comprehensive Hypertension, edited by Lip G. London, UK: Elsevier, 2007, p. 417–428. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Busst CJ, Bloomer LD, Scurrah KJ, Ellis JA, Barnes TA, Charchar FJ, Braund P, Hopkins PN, Samani NJ, Hunt SC, Tomaszewski M, Harrap SB. The epithelial sodium channel gamma-subunit gene and blood pressure: family based association, renal gene expression, and physiological analyses. Hypertension 58: 1073–1078, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carattino MD, Hill WG, Kleyman TR. Arachidonic acid regulates surface expression of epithelial sodium channels. J Biol Chem 278: 36202–36213, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen J, Kleyman TR, Sheng S. Gain-of-function variant of the human epithelial sodium channel. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 304: F207–F213, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, Cushman WC, Green LA, Izzo JL Jr, Jones DW, Materson BJ, Oparil S, Wright JT Jr, Roccella EJ. Seventh report of the joint national committee on prevention, detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood pressure. Hypertension 42: 1206–1252, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chraibi A, Horisberger JD. Na self inhibition of human epithelial Na channel: temperature dependence and effect of extracellular proteases. J Gen Physiol 120: 133–145, 2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Firsov D, Schild L, Gautschi I, Merillat AM, Schneeberger E, Rossier BC. Cell surface expression of the epithelial Na channel and a mutant causing Liddle syndrome: a quantitative approach. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 93: 15370–15375, 1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fuchs W, Larsen EH, Lindemann B. Current-voltage curve of sodium channels and concentration dependence of sodium permeability in frog skin. J Physiol 267: 137–166, 1977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gonzales EB, Kawate T, Gouaux E. Pore architecture and ion sites in acid-sensing ion channels and P2X receptors. Nature 460: 599–604, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Group GCR. GenSalt: rationale, design, methods and baseline characteristics of study participants. J Hum Hypertens 21: 639–646, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hannila-Handelberg T, Kontula K, Tikkanen I, Tikkanen T, Fyhrquist F, Helin K, Fodstad H, Piippo K, Miettinen HE, Virtamo J, Krusius T, Sarna S, Gautschi I, Schild L, Hiltunen TP. Common variants of the beta and gamma subunits of the epithelial sodium channel and their relation to plasma renin and aldosterone levels in essential hypertension. BMC Med Genet 6: 4, 2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.He FJ, MacGregor GA. Effect of longer-term modest salt reduction on blood pressure. Coch Database Sys Rev 30: Cd004937, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kashlan OB, Blobner BM, Zuzek Z, Tolino M, Kleyman TR. Na+ inhibits the epithelial Na+ channel by binding to a site in an extracellular acidic cleft. J Biol Chem 290: 568–576, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kashlan OB, Kleyman TR. ENaC structure and function in the wake of a resolved structure of a family member. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 301: F684–F696, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kawasaki T, Delea CS, Bartter FC, Smith H. The effect of high-sodium and low-sodium intakes on blood pressure and other related variables in human subjects with idiopathic hypertension. Am J Med 64: 193–198, 1978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kelly TN, He J. Genomic epidemiology of blood pressure salt sensitivity. J Hypertens 30: 861–873, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Knight KK, Olson DR, Zhou R, Snyder PM. Liddle's syndrome mutations increase Na+ transport through dual effects on epithelial Na+ channel surface expression and proteolytic cleavage. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 103: 2805–2808, 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee S, Wu MC, Lin X. Optimal tests for rare variant effects in sequencing association studies. Biostatistics 13: 762–775, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lewington S, Clarke R, Qizilbash N, Peto R, Collins R. Age-specific relevance of usual blood pressure to vascular mortality: a meta-analysis of individual data for one million adults in 61 prospective studies. Lancet 360: 1903–1913, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lim SS, Vos T, Flaxman AD, Danaei G, Shibuya K, Adair-Rohani H, Amann M, Anderson HR, Andrews KG, Aryee M, Atkinson C, Bacchus LJ, Bahalim AN, Balakrishnan K, Balmes J, Barker-Collo S, Baxter A, Bell ML, Blore JD, Blyth F, Bonner C, Borges G, Bourne R, Boussinesq M, Brauer M, Brooks P, Bruce NG, Brunekreef B, Bryan-Hancock C, Bucello C, Buchbinder R, Bull F, Burnett RT, Byers TE, Calabria B, Carapetis J, Carnahan E, Chafe Z, Charlson F, Chen H, Chen JS, Cheng AT, Child JC, Cohen A, Colson KE, Cowie BC, Darby S, Darling S, Davis A, Degenhardt L, Dentener F, Des Jarlais DC, Devries K, Dherani M, Ding EL, Dorsey ER, Driscoll T, Edmond K, Ali SE, Engell RE, Erwin PJ, Fahimi S, Falder G, Farzadfar F, Ferrari A, Finucane MM, Flaxman S, Fowkes FG, Freedman G, Freeman MK, Gakidou E, Ghosh S, Giovannucci E, Gmel G, Graham K, Grainger R, Grant B, Gunnell D, Gutierrez HR, Hall W, Hoek HW, Hogan A, Hosgood HD 3rd Hoy D, Hu H, Hubbell BJ, Hutchings SJ, Ibeanusi SE, Jacklyn GL, Jasrasaria R, Jonas JB, Kan H, Kanis JA, Kassebaum N, Kawakami N, Khang YH, Khatibzadeh S, Khoo JP, Kok C, Laden F, Lalloo R, Lan Q, Lathlean T, Leasher JL, Leigh J, Li Y, Lin JK, Lipshultz SE, London S, Lozano R, Lu Y, Mak J, Malekzadeh R, Mallinger L, Marcenes W, March L, Marks R, Martin R, McGale P, McGrath J, Mehta S, Mensah GA, Merriman TR, Micha R, Michaud C, Mishra V, Mohd Hanafiah K, Mokdad AA, Morawska L, Mozaffarian D, Murphy T, Naghavi M, Neal B, Nelson PK, Nolla JM, Norman R, Olives C, Omer SB, Orchard J, Osborne R, Ostro B, Page A, Pandey KD, Parry CD, Passmore E, Patra J, Pearce N, Pelizzari PM, Petzold M, Phillips MR, Pope D, Pope CA 3rd Powles J, Rao M, Razavi H, Rehfuess EA, Rehm JT, Ritz B, Rivara FP, Roberts T, Robinson C, Rodriguez-Portales JA, Romieu I, Room R, Rosenfeld LC, Roy A, Rushton L, Salomon JA, Sampson U, Sanchez-Riera L, Sanman E, Sapkota A, Seedat S, Shi P, Shield K, Shivakoti R, Singh GM, Sleet DA, Smith E, Smith KR, Stapelberg NJ, Steenland K, Stockl H, Stovner LJ, Straif K, Straney L, Thurston GD, Tran JH, Van Dingenen R, van Donkelaar A, Veerman JL, Vijayakumar L, Weintraub R, Weissman MM, White RA, Whiteford H, Wiersma ST, Wilkinson JD, Williams HC, Williams W, Wilson N, Woolf AD, Yip P, Zielinski JM, Lopez AD, Murray CJ, Ezzati M, AlMazroa MA, Memish ZA. A comparative risk assessment of burden of disease and injury attributable to 67 risk factors and risk factor clusters in 21 regions, 1990–2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet 380: 2224–2260, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liu F, Yang X, Mo X, Huang J, Chen J, Kelly TN, Hixson JE, Rao DC, Gu CC, Shimmin LC, Chen J, Rice TK, Li J, Schwander K, He J, Liu DP, Gu D. Associations of epithelial sodium channel genes with blood pressure: the GenSalt study. J Hum Hypertens 29: 224–228, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Luft FC, Rankin LI, Bloch R, Weyman AE, Willis LR, Murray RH, Grim CE, Weinberger MH. Cardiovascular and humoral responses to extremes of sodium intake in normal black and white men. Circulation 60: 697–706, 1979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Maarouf AB, Sheng N, Chen J, Winarski KL, Okumura S, Carattino MD, Boyd CR, Kleyman TR, Sheng S. Novel determinants of epithelial sodium channel gating within extracellular thumb domains. J Biol Chem 284: 7756–7765, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mente A, O'Donnell MJ, Rangarajan S, McQueen MJ, Poirier P, Wielgosz A, Morrison H, Li W, Wang X, Di C, Mony P, Devanath A, Rosengren A, Oguz A, Zatonska K, Yusufali AH, Lopez-Jaramillo P, Avezum A, Ismail N, Lanas F, Puoane T, Diaz R, Kelishadi R, Iqbal R, Yusuf R, Chifamba J, Khatib R, Teo K, Yusuf S. Association of urinary sodium and potassium excretion with blood pressure. N Engl J Med 371: 601–611, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Miller JZ, Daugherty SA, Weinberger MH, Grim CE, Christian JC, Lang CL. Blood pressure response to dietary sodium restriction in normotensive adults. Hypertension 5: 790–795, 1983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Miller JZ, Weinberger MH, Daugherty SA, Fineberg NS, Christian JC, Grim CE. Heterogeneity of blood pressure response to dietary sodium restriction in normotensive adults. J Chronic Dis 40: 245–250, 1987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Miura K, Daviglus ML, Dyer AR, Liu K, Garside DB, Stamler J, Greenland P. Relationship of blood pressure to 25-year mortality due to coronary heart disease, cardiovascular diseases, and all causes in young adult men: the Chicago Heart Association Detection Project in Industry. Arch Intern Med 161: 1501–1508, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mount DB. Transport of sodium, chloride, and potassium. In: Brenner & Rector's The Kidney, edited by Skorecki K, Chertow GM, Marsden PA, Taal MW, Yu ASL. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier, 2016, p. 144–184. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mozaffarian D, Fahimi S, Singh GM, Micha R, Khatibzadeh S, Engell RE, Lim S, Danaei G, Ezzati M, Powles J. Global sodium consumption and death from cardiovascular causes. N Engl J Med 371: 624–634, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mueller GM, Yan W, Copelovitch L, Jarman S, Wang Z, Kinlough CL, Tolino MA, Hughey RP, Kleyman TR, Rubenstein RC. Multiple residues in the distal C terminus of the alpha-subunit have roles in modulating human epithelial sodium channel activity. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 303: F220–F228, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nagy Z, Busjahn A, Bahring S, Faulhaber HD, Gohlke HR, Knoblauch H, Rosenthal M, Muller-Myhsok B, Schuster H, Luft FC. Quantitative trait loci for blood pressure exist near the IGF-1, the Liddle syndrome, the angiotensin II-receptor gene and the renin loci in man. J Am Soc Nephrol 10: 1709–1716, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nguyen KD, Pihur V, Ganesh SK, Rakha A, Cooper RS, Hunt SC, Freedman BI, Coresh J, Kao WH, Morrison AC, Boerwinkle E, Ehret GB, Chakravarti A. Effects of rare and common blood pressure gene variants on essential hypertension: results from the family blood pressure program, CLUE, and atherosclerosis risk in communities studies. Circ Res 112: 318–326, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Palmer LG, Sackin H, Frindt G. Regulation of Na+ channels by luminal Na+ in rat cortical collecting tubule. J Physiol 509: 151–162, 1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Samaha FF, Rubenstein RC, Yan W, Ramkumar M, Levy DI, Ahn YJ, Sheng S, Kleyman TR. Functional polymorphism in the carboxyl terminus of the alpha-subunit of the human epithelial sodium channel. J Biol Chem 279: 23900–23907, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schrödinger L. The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System, Version 1.3. Schrödinger, LLC 2010.

- 42.Sheng S, Carattino MD, Bruns JB, Hughey RP, Kleyman TR. Furin cleavage activates the epithelial Na+ channel by relieving Na+ self-inhibition. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 290: F1488–F1496, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shi S, Ghosh DD, Okumura S, Carattino MD, Kashlan OB, Sheng S, Kleyman TR. Base of the thumb domain modulates epithelial sodium channel gating. J Biol Chem 286: 14753–14761, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Shimkets RA, Warnock DG, Bositis CM, Nelson-Williams C, Hansson JH, Schambelan M, Gill JR Jr, Ulick S, Milora RV, Findling JW. Liddle's syndrome: heritable human hypertension caused by mutations in the beta subunit of the epithelial sodium channel. Cell 79: 407–414, 1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Snyder PM, Price MP, McDonald FJ, Adams CM, Volk KA, Zeiher BG, Stokes JB, Welsh MJ. Mechanism by which Liddle's syndrome mutations increase activity of a human epithelial Na+ channel. Cell 83: 969–978, 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Thomas CP, Auerbach S, Stokes JB, Volk KA. 5′-Heterogeneity in epithelial sodium channel alpha-subunit mRNA leads to distinct NH2-terminal variant proteins. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 274: C1312–C1323, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tobin MD, Tomaszewski M, Braund PS, Hajat C, Raleigh SM, Palmer TM, Caulfield M, Burton PR, Samani NJ. Common variants in genes underlying monogenic hypertension and hypotension and blood pressure in the general population. Hypertension 51: 1658–1664, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tong Q, Menon AG, Stockand JD. Functional polymorphisms in the α-subunit of the human epithelial Na+ channel increase activity. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 290: F821–F827, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Vehaskari VM. Heritable forms of hypertension. Pediatr Nephrol 24: 1929–1937, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Weinberger MH. Salt sensitivity of blood pressure in humans. Hypertension 27: 481–490, 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Whelton PK, He J, Appel LJ, Cutler JA, Havas S, Kotchen TA, Roccella EJ, Stout R, Vallbona C, Winston MC, Karimbakas J. Primary prevention of hypertension: clinical and public health advisory from The National High Blood Pressure Education Program. J Am Med Assoc 288: 1882–1888, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wong ZY, Stebbing M, Ellis JA, Lamantia A, Harrap SB. Genetic linkage of beta and gamma subunits of epithelial sodium channel to systolic blood pressure. Lancet 353: 1222–1225, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yan W, Spruce L, Rosenblatt MM, Kleyman TR, Rubenstein RC. Intracellular trafficking of a polymorphism in the COOH-terminus of the α-subunit of the human epithelial sodium channel is modulated by casein kinase 1. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 293: F868–F876, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yang X, He J, Gu D, Hixson JE, Huang J, Rao DC, Shimmin LC, Chen J, Rice TK, Li J, Schwander K, Kelly TN. Associations of epithelial sodium channel genes with blood pressure changes and hypertension incidence: The GenSalt Study. Am J Hypertens 27: 1370–1376, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zhao Q, Gu D, Hixson JE, Liu DP, Rao DC, Jaquish CE, Kelly TN, Lu F, Ma J, Mu J, Shimmin LC, Chen J, Mei H, Hamm LL, He J. Common variants in epithelial sodium channel genes contribute to salt sensitivity of blood pressure: The GenSalt study. Circ Cardiovasc Genet 4: 375–380, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]