Inhibitory neurotransmitters regulate gastric motor activity. However, the exact role of how different neurotransmitters contribute to this activity remains to be fully investigated. In the present study we demonstrate a convergence of nitric oxide and purine components to inhibitory motor responses of the gastric antrum. We also show that these responses are highly conserved from rodents to primates demonstrating the importance of these inhibitory pathways in the modulation of gastric motor activity across diverse species.

Keywords: gastric motor activity, inhibitory motor nerves, smooth muscle relaxation, nitric oxide, P2Y1 receptors

Abstract

Inhibitory motor neurons regulate several gastric motility patterns including receptive relaxation, gastric peristaltic motor patterns, and pyloric sphincter opening. Nitric oxide (NO) and purines have been identified as likely candidates that mediate inhibitory neural responses. However, the contribution from each neurotransmitter has received little attention in the distal stomach. The aims of this study were to identify the roles played by NO and purines in inhibitory motor responses in the antrums of mice and monkeys. By using wild-type mice and mutants with genetically deleted neural nitric oxide synthase (Nos1−/−) and P2Y1 receptors (P2ry1−/−) we examined the roles of NO and purines in postjunctional inhibitory responses in the distal stomach and compared these responses to those in primate stomach. Activation of inhibitory motor nerves using electrical field stimulation (EFS) produced frequency-dependent inhibitory junction potentials (IJPs) that produced muscle relaxations in both species. Stimulation of inhibitory nerves during slow waves terminated pacemaker events and associated contractions. In Nos1−/− mice IJPs and relaxations persisted whereas in P2ry1−/− mice IJPs were absent but relaxations persisted. In the gastric antrum of the non-human primate model Macaca fascicularis, similar NO and purine neural components contributed to inhibition of gastric motor activity. These data support a role of convergent inhibitory neural responses in the regulation of gastric motor activity across diverse species.

NEW & NOTEWORTHY

Inhibitory neurotransmitters regulate gastric motor activity. However, the exact role of how different neurotransmitters contribute to this activity remains to be fully investigated. In the present study we demonstrate a convergence of nitric oxide and purine components to inhibitory motor responses of the gastric antrum. We also show that these responses are highly conserved from rodents to primates demonstrating the importance of these inhibitory pathways in the modulation of gastric motor activity across diverse species.

inhibitory motor neurons regulate motility patterns in the mammalian stomach, such as receptive relaxation, gastric peristalsis, and pyloric sphincter functions (24). Activation of enteric inhibitory neurons causes hyperpolarization of postjunctional membranes, termed inhibitory junction potentials (IJPs), and muscle relaxation (12, 18, 20, 31, 44). Multiple neurotransmitters have been suggested to participate in enteric inhibitory neural regulation, and at a minimum inhibitory neurotransmission is based on nitrergic, purinergic, and peptidergic components. Regional differences in the complement of neurotransmitters and postjunctional transduction and effector mechanisms customize responses to accomplish specialized motor needs.

IJPs in many regions of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract consist of two major components: 1) an initial fast, large amplitude hyperpolarization (fIJP), and 2) a second slower, reduced-amplitude hyperpolarization (sIJP) (18). The neurotransmitter responsible for the sIJP has been known for more than 20 yr (3, 37), and this component is due to the release of nitric oxide (NO) from motor neurons, activation of guanylate cyclase (GC), and production of cGMP in postjunctional cells (19, 39, 45). Most investigators consider the activation of cGMP-dependent protein kinase and phosphorylation of various effector proteins as the final steps in generating nitrergic responses in visceral smooth muscles (10, 38). The identity of the neurotransmitter mediating fIJPs has been more controversial. For many years ATP was assumed to be the ubiquitous purinergic neurotransmitter, but recent evidence suggests that other purines might be dominant in this response. Purinergic responses are mediated by binding of the transmitter to postjunctional P2Y1 receptors, Ca2+ release from stores and activation of, at a minimum, small conductance Ca2+-activated (SK) channels (2, 11, 18). In some tissues a third component of IJPs can be identified (21). These events are characterized by even slower kinetics than the sIJP and typically longer periods of stimulation and/or higher frequencies of EFS are required for this component of enteric inhibitory neurotransmission to be resolved and are thought to be due to the release of the peptide VIP or possibly PACAP in some tissues (21).

Although much has been determined about the nature of enteric neurotransmitters and how these substances elicit postjunctional hyperpolarization, less is known about the mechanisms linking inhibitory neurotransmission to relaxation. This is particularly true of the distal stomach in which enteric motor neurotransmission regulates the force of contraction during fasting and fed motor patterns. Since there appears to be only one class of enteric inhibitory neurons and these neurons release NO, peptides, and presumably purines, then another level of complexity is produced as postjunctional cells integrate neurotransmitter responses. In the present study we have dissected inhibitory responses in murine and non-human primate distal stomachs and determined how nitrergic and purinergic neurotransmitters elicit postjunctional motor responses. Our data suggest that while electromechanical coupling is of major importance for purinergic inhibitory responses, nitrergic responses are mediated mainly by membrane potential independent, pharmacomechanical coupling. We have also studied the consequences of stimulating inhibitory neurons during slow waves and between slow waves on contractile responses and electrical patterning. Our data demonstrate convergence of inhibitory neural inputs in regulating gastric motor responses in murine and primate stomachs.

METHODS

Ethical approval.

Nos1tm1Plh/J heterozygotes and B6.129P2-P2ry1tm1Bhk/J homozygotes (9) were obtained from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME) and mated to produce B6.Nos1tm1Plh/J and B6.129P2-P2ry1tm1Bhk/J offspring (Nos1−/− or nNos1−/− and P2ry1−/− mice, respectively). Up to 10 mice (both sexes; see Table 1) between the ages of P30–P60 were used for the described experiments. C57Bl6/6J were used as control mice as recommended by The Jackson Laboratory. Animals were killed by isoflurane sedation followed by cervical dislocation and exsanguination. The stomach from the esophagus to below the pyloric sphincter was removed and placed in oxygenated Krebs-Ringer buffer (KRB) for further sharp dissection. The Institutional Animal Use and Care Committee at the University of Nevada approved procedures used on mice.

Table 1.

Membrane potential and slow wave electrical parameters recorded from circular muscle of antral tissues of different strains of mice and monkey stomach

| Wild-Type Murine Antrum (n = 6) |

Nos1−/− Murine Antrum (n = 5) |

P2ry1−/− Murine Antrum (n = 5) |

Primate Antrum (n = 7) |

|||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Electrical Parameters | No drugs | Atropine | Atropine and l-NNA | Atropine, l-NNA, and MRS2500 | No drugs | Atropine | Atropine and l-NNA | Atropine, l-NNA and MRS2500 | No drugs | Atropine | Atropine and l-NNA | Atropine, l-NNA, and MRS2500 | No drugs | Atropine | Atropine and l-NNA | Atropine, l-NNA, and MRS2500 |

| Resting membrane potential, mV | −72.2 ± 1.5 | −74.3 ± 1.4 n.s. | −72.5 ± 1.4 n.s. | −71.1 ± 1.0 n.s. | −63.2 ± 2.6 | −63.0 ± 1.7 n.s. | −65.5 ± 0.5 n.s. | −64.1 ± 1.1 n.s. | −70.7 ± 1.9 | −70.8 ± 1.5 n.s. | −70.7 ± 2.1 n.s. | −71.7 ± 2.1 n.s. | −70.2 ± 2.3 | −69.5 ± 2.5 n.s. | −68.7 ± 3.1 n.s. | −68.5 ± 2.8 n.s. |

| Slow wave amplitude, mV | 34.4 ± 2.4 | 36.0 ± 1.3 n.s. | 34.8 ± 1.8 n.s. | 35.3 ± 0.8 n.s. | 29.4 ± 2.5 | 28.5 ± 1.7 n.s. | 26.7 ± 2.1 n.s. | 29.5 ± 1.8 n.s. | 35.7 ± 0.5 | 34.7 ± 1.1 n.s. | 36.2 ± 1.2 n.s. | 37.5 ± 2.6 n.s. | 33.7 ± 4.8 n.s. | 32.2 ± 4.3 n.s. | 31.9 ± 4.2 n.s. | 29.8 ± 4.1 n.s. |

| Slow wave duration, s | 11.2 ± 0.6 | 11.2 ± 0.7 n.s. | 10.8 ± 0.4 n.s. | 10.6 ± 0.4 n.s. | 8.9 ± 0.5 | 8.7 ± 0.6 n.s. | 8.8 ± 1.8 n.s. | 9.1 ± 0.4 n.s. | 10.4 ± 0.4 | 10.3 ± 0.6 n.s. | 10.9 ± 0.8 n.s. | 10.5 ± 0.9 n.s. | 4.9 ± 0.4 | 4.7 ± 0.3 n.s. | 5.1 ± 0.4 n.s. | 5.3 ± 0.4 n.s. |

| Slow wave frequency, min−1 | 3.4 ± 0.2 | 5.3 ± 0.9 | 3.2 ± 0.6 | 5.2 ± 0.8 | ||||||||||||

| IJP | ||||||||||||||||

| 1 Hz | ||||||||||||||||

| Diastolic | ||||||||||||||||

| Amplitude, mV | 8.7 ± 1.2 | 8.0 ± 01.6 n.s. | 8.1 ± 01.2 n.s. | 0.0 ± 0.0*** | 8.5 ± 0.8 | 7.7 ± 0.8 n.s. | 7.6 ± 0.9 n.s. | 0.3 ± 0.2*** | 0.9 ± 0.3 | 1.3 ± 0.2 n.s. | 0.1 ± 0.1* | 0.0 ± 0.0* | 2.6 ± 0.9 | 2.7 ± 0.8 n.s. | 3.3 ± 0.8 n.s. | 0.0 ± 0.0 n.s. |

| Duration, s | 1.0 ± 0.1 | 1.0 ± 0.1 n.s. | 1.0 ± 0.1 n.s. | 0.0 ± 0.0*** | 1.2 ± 0.1 | 1.1 ± 0.1 n.s. | 1.1 ± 0.1 n.s. | 0.2 ± 0.1*** | 0.2 ± 0.2 | 0.9 ± 0.1** | 0.1 ± 0.1 n.s. | 0.0 ± 0.0 n.s. | 1.2 ± 0.1 | 1.2 ± 0.2 n.s. | 1.5 ± 0.2 n.s. | 0.0 ± 0.0*** |

| Plateau | ||||||||||||||||

| Amplitude, mV | 26.5 ± 0.7 | 29.2 ± 2.8 n.s. | 24.3 ± 2.7 n.s. | 0.0 ± 0.0*** | 18.0 ± 2.6 | 20.6 ± 2.3 n.s. | 18.8 ± 1.4 n.s. | 0.0 ± 0.0*** | 0.2 ± 0.2 | 0.0 ± 0.0 n.s. | 0.0 ± 0.0 n.s. | 0.0 ± 0.0 n.s. | 20.9 ± 6.9 | 23.3 ± 5.9 n.s. | 23.4 ± 5.7 n.s. | 0.0 ± 0.0 n.s. |

| Duration, s | 0.9 ± 0.1 n.s. | 0.9 ± 0.1 n.s. | 1.0 ± 0.2 n.s. | 0.0 ± 0.0*** | 1.2 ± 0.3 | 1.1 ± 0.3 n.s. | 1.2 ± 0.2 n.s. | 0.0 ± 0.0** | 0.1 ± 0.1 | 0.0 ± 0.0 n.s. | 0.0 ± 0.0 n.s. | 0.0 ± 0.0 n.s. | 1.0 ± 0.2 | 1.4 ± 0.2 n.s. | 1.4 ± 0.1 n.s. | 0.0 ± 0.0** |

| 5 Hz | ||||||||||||||||

| Diastolic | ||||||||||||||||

| Amplitude, mV | 8.8 ± 0.9 | 9.7 ± 1.6 n.s. | 9.5 ± 1.2 n.s. | 0.2 ± 0.2*** | 8.6 ± 0.8 | 8.4 ± 0.8 n.s. | 7.8 ± 0.9 n.s. | 0.4 ± 0.3*** | 1.6 ± 0.6 | 2.5 ± 0.2 n.s. | 0.0 ± 0.0* | 0.1 ± 0.1* | 3.7 ± 0.9 | 4.5 ± 0.8 n.s. | 4.4 ± 1.0 n.s. | 0.0 ± 0.0** |

| Duration, s | 1.8 ± 0.1 | 1.8 ± 0.1 n.s. | 1.8 ± 0.1 n.s. | 0.2 ± 0.2*** | 1.5 ± 0.1 | 1.7 ± 0.1 n.s. | 1.8 ± 0.1 n.s. | 0.4 ± 0.3*** | 0.8 ± 0.4 | 2.2 ± 0.4* | 0.0 ± 0.0 n.s. | 0.3 ± 0.3 n.s. | 3.7 ± 1.1 | 4.8 ± 1.3 n.s. | 2.2 ± 0.2 n.s. | 0.0 ± 0.0* |

| Plateau | ||||||||||||||||

| Amplitude, mV | 30.8 ± 1.8 | 30.1 ± 2.8 n.s. | 32.6 ± 1.3 n.s. | 3.7 ± 2.8*** | 21.7 ± 1.0 | 24.3 ± 3.7 n.s. | 29.8 ± 2.4 n.s. | 1.0 ± 1.0*** | 5.9 ± 4.1 | 22.7 ± 4.1** | 0.3 ± 0.2 n.s. | 0.0 ± 0.0 n.s. | 27.3 ± 4.0 | 28.0 ± 3.3 n.s. | 26.9 ± 4.3 n.s. | 0.0 ± 0.0*** |

| Duration, s | 1.8 ± 0.1 | 1.8 ± 0.1 n.s. | 1.8 ± 0.1 n.s. | 0.8 ± 0.4* | 1.7 ± 0.1 | 1.9 ± 0.1 n.s. | 1.8 ± 0.1 n.s. | 0.2 ± 0.2*** | 0.6 ± 0.3 | 1.7 ± 0.1* | 0.3 ± 0.3 n.s. | 0.0 ± 0.0 n.s. | 4.1 ± 1.1 | 4.6 ± 1.2 n.s. | 2.0 ± 0.1 n.s. | 0.0 ± 0.0* |

| 10 Hz | ||||||||||||||||

| Diastolic | 11.1 ± 1.5 | 10.9 ± 2.0 n.s. | 11.6 ± 1.4 n.s. | 1.2 ± 0.5** | 8.6 ± 1.0 | 8.8 ± 1.2 n.s. | 8.3 ± 1.1 n.s. | 1.6 ± 0.4*** | 1.5 ± 0.6 | 3.5 ± 0.3** | 0.9 ± 0.3 n.s. | 0.6 ± 0.3 n.s. | 4.6 ± 1.0 | 5.4 ± 1.2 n.s. | 6.0 ± 1.2 n.s. | 0.1 ± 0.1* |

| Amplitude, mV | 1.9 ± 0.2 | 2.0 ± 0.1 n.s. | 2.0 ± 0.1 n.s. | 0.8 ± 0.3** | 1.4 ± 0.1 | 1.9 ± 0.2 n.s. | 2.1 ± 0.1 n.s. | 1.3 ± 0.3 n.s. | 1.7 ± 0.8 | 2.7 ± 0.2 n.s. | 1.2 ± 0.3 n.s. | 0.6 ± 0.4 n.s. | 3.9 ± 1.3 | 5.2 ± 1.6 n.s. | 2.9 ± 0.6 n.s. | 0.7 ± 0.7 n.s. |

| Duration, s | ||||||||||||||||

| Plateau | 34.9 ± 1.1 | 38.9 ± 2.8 n.s. | 30.8 ± 4.6 n.s. | 5.0 ± 1.6*** | 23.8 ± 2.1 | 26.1 ± 1.8 n.s. | 29.3 ± 2.5 n.s. | 1.0 ± 1.0*** | 22.0 ± 4.8 | 26.6 ± 3.1 n.s. | 0.7 ± 0.5*** | 0.0 ± 0.0*** | 29.0 ± 3.8 | 31.5 ± 3.2 n.s. | 28.7 ± 4.1 n.s. | 0.0 ± 0.0*** |

| Amplitude, mV | 2.0 ± 0.1 | 2.2 ± 0.1 n.s. | 1.7 ± 0.1 n.s. | 1.2 ± 0.1*** | 1.8 ± 0.2 | 1.9 ± 0.2 n.s. | 2.0 ± 0.1 n.s. | 0.3 ± 0.3*** | 4.4 ± 2.0 | 2.9 ± 1.0 n.s. | 0.1 ± 0.1 n.s. | 0.0 ± 0.0 n.s. | 4.8 ± 1.7 | 4.8 ± 1.8 n.s. | 2.2 ± 0.3 n.s. | 0.0 ± 0.0 n.s. |

Postjunctional inhibitory neural response (IJP) parameters to electrical field stimulation (EFS; 1, 5, and 10 Hz for 1 s) delivered during the diastolic membrane potential and plateau phase of slow waves under different experimental conditions. l-NNA, l-NG-nitroarginine. Levels of significance denoted by n.s. = not significant;

P ≤ 0.05;

P ≤ 0.01,

P ≤ 0.001 using one-way ANOVA and Student's t-test.

The stomachs from seven Cynomolgus monkeys (Macaca fascicularis) between 2.5 and 7 yr or age (both sexes) were obtained from Charles River Laboratories (CRL; Sparks, NV). Monkeys were initially sedated with ketamine (10 mg/kg), then administered 0.7 ml Beuthanasia-D solution (Schering-Plough, Kenilworth, NJ; pentobarbital sodium and phenytoin sodium) followed by exsanguination. Stomachs were transported from CRL to the University of Nevada in precooled KRB and further dissected within 90 min after animals were euthanized. All animals used in the described studies were maintained and the experiments performed in accordance with the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.

Electrophysiological experiments.

Stomachs were opened along the lesser curvature and gastric contents were washed away with KRB. For mice, the corpus and antrum were isolated by a surgical incision across the stomach along the border between the corpus and the fundus, which was indicated by a change in the structure of the mucosa. A second incision was made across the terminal antrum just oral to the pylorus. Individual regions of the stomach were subsequently pinned to the base of a Sylgard silicone elastomer (Dow Corning, Midland, MI) dish and the mucosa was removed by sharp dissection. The corpus and antrum were distinguished and separated from each other by an incision across the incisura angularis. Secondary pieces of tissues (2 × 6 mm) were isolated from along the greater curvature of the antrum and placed in a recording chamber with the serosal aspect of the muscle facing upward for simultaneous intracellular and isometric force measurements. A region of monkey antrum along the greater curvature (10–20 mm from the pyloric sphincter) was isolated and the mucosa removed by sharp dissection. A 1-mm-thick cross section, cut parallel to the long axis of the circular layer, was turned on-side and pinned to a Sylgard base so that the entire cross section of the tunica muscularis could be observed.

Intracellular microelectrode recordings were performed as previously described (18). Briefly, impalements of circular muscle cells along the greater curvature were made with glass microelectrodes having resistances of 80–120 MΩ. Transmembrane potentials were recorded with a high impedance electrometer (Axon Instruments, Union City, CA). Data were recorded on a PC running AxoScope 10 data acquisition software (Axon Instruments) and hard copies were made using Clampfit analysis software (Axon Instruments). In all experiments, parallel platinum electrodes were placed on either side of the muscle strips and neural responses were elicited by square wave pulses of electrical field stimulation (EFS; 0.3-ms pulse duration, 1-, 5-, and 10-Hz, train duration of 1 s, 10–15 V) using a Grass S48 stimulator (Quincy, MA).

Isometric force measurements.

Simultaneous isometric force and intracellular microelectrode recordings were performed. In these experiments the gastric antrum were prepared as described above for intracellular recordings. In mice, the greater curvature was isolated for intracellular recordings using tungsten pins (50 μm; Goodfellow, Huntingdon, England) and the lesser curvature end attached with suture thread to a Gould isometric strain gauge (Gould UC3; Gould Instruments). A resting force of 5 mN was applied, which was shown to set the muscles at optimum length (data not shown). This was followed by an equilibration period of 1 h, during which time the bath was continuously perfused with oxygenated KRB.

Solutions and drugs.

Tissues were constantly perfused with oxygenated KRB of the following composition (in mM): 118.5 NaCl, 4.5 KCl, 1.2 MgCl2, 23.8 NaHCO3, 1.2 KH2PO4, 11.0 dextrose, and 2.4 CaCl2. The pH of the KRB was 7.3–7.4 when bubbled with 97% O2-3% CO2 at 37 ± 0.5°C. Muscles were left to equilibrate for at least 1 h before experiments were begun. Atropine and l-NG-nitroarginine (l-NNA) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). 2-Iodo-N6-methyl-(N)-methanocarba-2′-deoxyadenosine-3′,5′-bisphosphate tetraammonium salt (MRS2500) was purchased from Tocris Bioscience (Ellisville, MO).

Data analysis.

Data are expressed as means ± SE. One-way ANOVA and Student's t-test were used to evaluate any differences, and *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001 were considered a statistically significant difference at the 95, 99, and 99.9% levels. The n values reported in the text and Table 1 refers to the number of animals used for each independent experimental protocol. Statistical analysis was performed using SIGMASTAT 3.1 (Jandel Scientific Software, San Jose, CA).

Several electrical mechanical parameters were analyzed: 1) resting membrane potential (RMP), 2) slow wave amplitude, 3) total slow wave duration as measured from the beginning of the upstroke phase to when membrane potential returned to the most diastolic point, 4) slow wave frequency, 5) amplitude of inhibitory junction potentials (IJPs), 6) duration of IJPs, 7) isometric force amplitude, and 8) isometric force duration. Figures displayed were made from digitized data using Corel Draw X4 (Corel, Ontario, Canada).

RESULTS

Electrical and mechanical activities from wild-type, Nos1−/−, and P2ry1−/− stomachs.

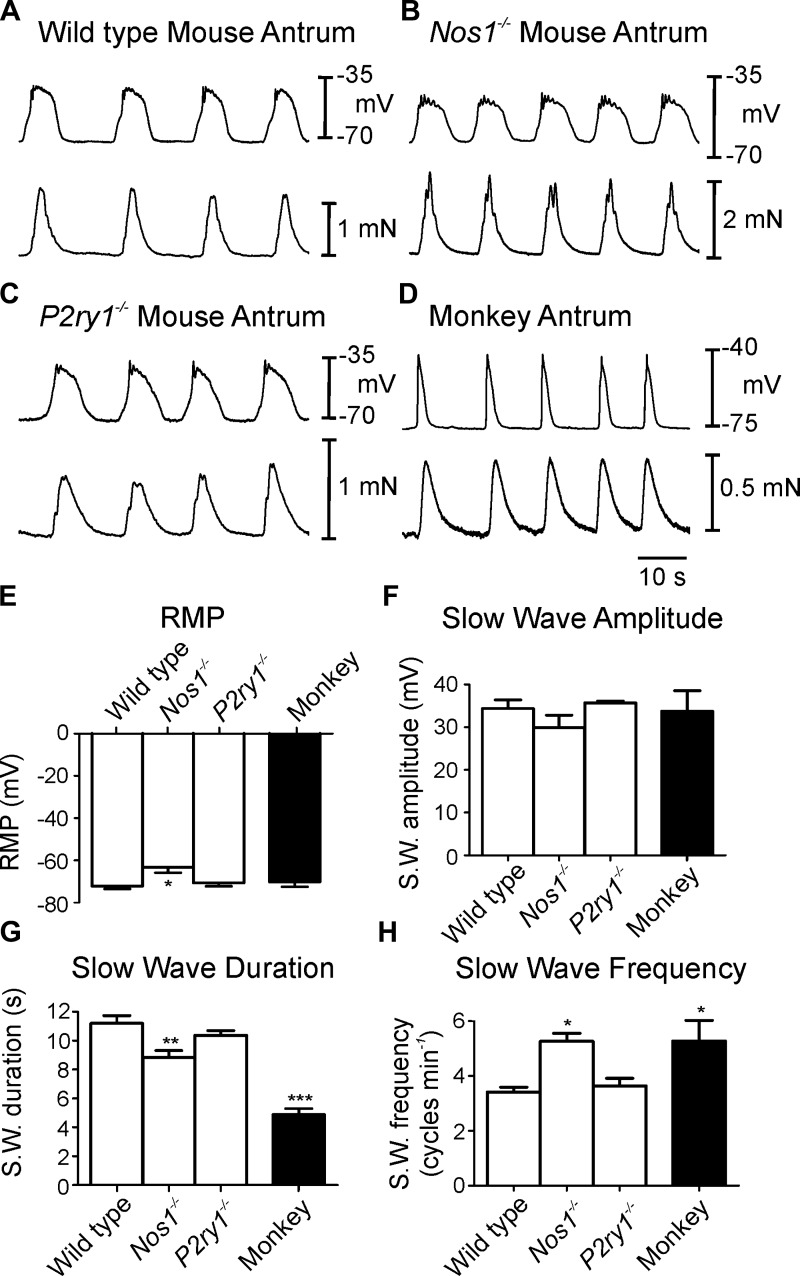

Circular muscle cells of wild-type murine gastric antrums had RMP (i.e., most diastolic potential) averaging −72.2 ± 1.5 mV. Spontaneous slow waves, 34.4 ± 2.4 mV in amplitude and 11.2 ± 0.6 s in total duration, consisted of an upstroke depolarization, partial repolarization, and a plateau phase that was sustained for several seconds before repolarization to RMP. In some cases the upstroke depolarization had an inflection that appeared to separate this phase into two discrete depolarization events (Fig. 1A). Slow waves occurred spontaneously, at an average frequency of 3.4 ± 0.2 cycles/min. Each slow wave was associated with a phasic contraction of the circular muscle that averaged 0.54 ± 0.06 mN in force and 11.8 ± 0.5 s in duration. Phasic contractions occurred at the same frequency as slow waves (i.e., 3.4 ± 0.2 min−1; n = 6; Fig. 1A).

Fig. 1.

Spontaneous slow waves and associated mechanical activities of mouse and monkey gastric antrum. A: pacemaker activity and mechanical activity in a wild-type mouse antrum. Slow waves and simultaneous contractile activity from Nos1−/− mice antrum (B) and P2ry1−/− antrum (C). D: antral slow waves and associated contractions from monkey antrum. Electrical activity is the top trace and isometric force in the bottom trace in A–D. E–H: summary data of resting membrane potential (RMP; E), slow wave amplitude (S.W.; F), slow wave duration (G), and slow wave frequency (H). Note that RMP was more depolarized and slow wave shorter in duration but frequency faster in Nos1−/− mice compared with wild-type and P2r1−/− mice. Monkey slow wave amplitude was not different but duration was significantly shorter and frequency faster than wild-type mouse antrum. *P ≤ 0.05, **P ≤ 0.01, significantly different from wild type by one-way ANOVA.

Antral muscle cells from Nos1−/− mice had RMPs that were significantly depolarized from wild-type cells (−63.2 ± 2.6 mV; Table 1; n = 5). Slow waves in Nos1−/− muscles averaged 29.4 ± 2.5 mV in amplitude and 8.9 ± 0.5 s in duration and occurred at an average frequency of 5.3 ± 0.9 cycles/min. Phasic contractions were also initiated by slow waves in Nos1−/− mice that averaged 0.58 ± 0.05 mN in force and 9.2 ± 0.5 s in duration and occurred at the same frequency as slow waves (Fig. 1B). RMP, slow wave duration and frequency were statistically different in Nos1−/− mice compared with wild-type parameters (Table 1).

In antral muscle cells of P2ry1−/− animals RMP averaged −70.7 ± 1.9 mV and slow waves 35.7 ± 0.5 mV in amplitude and 10.4 ± 0.4 s in duration occurred at a frequency of 3.2 ± 0.6 cycles/min (n = 5; Fig. 1E). Phasic contractions were initiated by each slow wave in P2ry1−/− antral muscles and averaged 0.62 ± 0.04 mN in amplitude and 10.7 ± 0.7 s in duration (Fig. 1C). There was no statistical difference when RMP, slow wave and isometric force contraction parameters were compared between P2ry1−/− and wild-type animals (P > 0.05 for all parameters).

Basal electrical and mechanical activities of antral muscles from cynomolgus monkey (macaca fascicularis).

Intracellular recordings from antral circular muscle of Cynomologus monkeys revealed RMPs averaging −70.2 ± 2.3 mV. Spontaneous slow waves, 33.7 ± 4.8 mV in amplitude and 4.9 ± 0.4s in duration, occurred at 5.2 ± 0.8 cycles/min (Fig. 1E). As with the murine stomach, each slow wave of monkey antrum was associated with a phasic contraction of the circular muscle that averaged 0.7 ± 0.04 mN in amplitude and 5.8 ± 0.4 s in duration. Similar to mouse stomach, phasic contractions occurred at the same frequency as slow waves (i.e., 5.2 ± 0.8 cycles/min; Fig. 1D).

Postjunctional neuronal responses in the stomachs of wild-type mice.

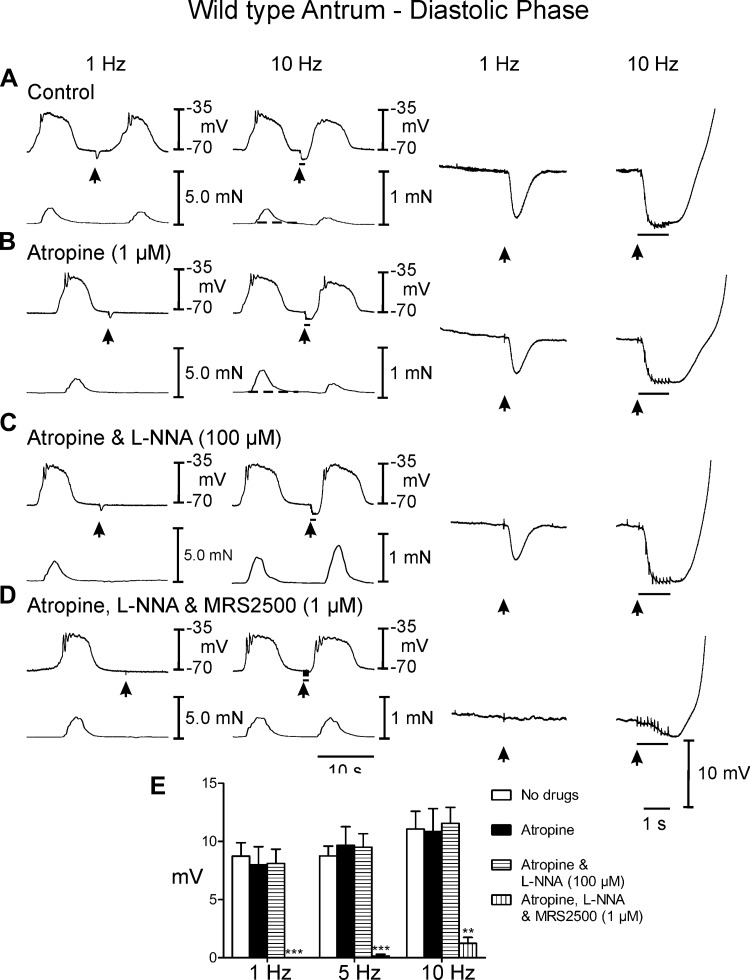

EFS of murine antral muscles during the diastolic period (i.e., between slow waves) caused membrane hyperpolarization or IJPs. IJPs were associated with attenuation in the phasic contraction (0.41 ± 0.03 mN) immediately following EFS (Fig. 2A). EFS at 5–10 Hz often initiated phase advancement of slow waves that produced a premature contraction that was smaller in amplitude (0.2 ± 0.02 mN). To determine the contribution of cholinergic motor nerves in modifying the postjunctional inhibitory responses, EFS was performed in the presence of atropine (1 μM). As previously reported, atropine had no statistically significant effect on spontaneous electrical or mechanical activities (see Figs. 2B and 3B). IJPs evoked between slow waves in the presence of atropine consisted of a transient hyperpolarization that averaged 8.7 ± 1.2 mV in amplitude and 1.0 ± 0.1 s in duration with 1 Hz and 11.1 ± 1.5 mV in amplitude and 1.9 ± 0.2 s duration at 10 Hz (Fig. 2, A and E). EFS at 5 and 10 Hz initiated premature slow waves at the break of the stimulus, which caused phase advancement of the next contraction. In atropine there was a slight relaxation below baseline at 5–10 Hz and as in control conditions the phase advancement of slow waves produced a premature contraction that was smaller in amplitude (0.26 ± 0.04 mN) than slow wave associated contractions prior to EFS (P < 0.05).

Fig. 2.

Postjunctional neural responses of wild type gastric antrum to electrical field stimulation (EFS) during the diastolic phase of membrane potential. A: under control conditions EFS at 1 and 10 Hz (arrows and horizontal bars) elicited inhibitory junction potentials (IJPs). Following EFS, slow waves and associated contractions were attenuated. The rate of rise of the slow wave upstroke was also reduced. EFS also produced a relaxation in baseline tension (dashed line indicates the change in baseline isometric force). B: atropine (1 μM) had little or no effect on EFS evoked neural responses. C: addition of l-NG-nitroarginine (l-NNA; 100 μM) in the presence of atropine did not reduce the initial fast, large amplitude hyperpolarization (fIJP) at 1 or 10 Hz but abolished the attenuation of slow waves and associated relaxation. In many instances at 10 Hz the phasic contraction immediately following EFS was potentiated. D: MRS2500 (1 μM) in atropine and l-NNA abolished the fIJP at 1 Hz and greatly reduced it at 10 Hz. E: summary data of IJP amplitude under different experimental conditions. IJPs were only significantly attenuated or inhibited by MRS2500. Electrical activity is shown in the top trace and mechanical activity in the bottom trace on the left. Enlarged traces of IJPs at faster sweep speeds are shown on the right. **P ≤ 0.01; ***P ≤ 0.001 significantly different than control by one-way ANOVA.

Fig. 3.

Postjunctional neural responses of wild type gastric antrum to EFS evoked during the plateau phase of slow waves. A: EFS at 1 and 10 Hz (arrows and horizontal bars) elicited large amplitude IJPs and disrupted slow waves and associated contractions. The slow wave and contraction immediately following EFS were phase advanced and attenuated. The slow wave upstroke rate of rise was also reduced. B: atropine (1 μM) had little or no effect on EFS evoked neural responses. C: l-NNA (100 μM) in the presence of atropine did not reduce the fIJP at 1 or 10 Hz and the amplitude of contractions following EFS was potentiated. The upstroke rate of rise was increased in l-NNA. D: MRS2500 (1 μM) in atropine and l-NNA abolished the fIJP at 1 Hz and greatly reduced the IJP and relaxation at 10 Hz. E: summary data of IJP amplitude under different experimental conditions. Electrical activity is shown in the top trace and mechanical activity in the bottom trace in A–D. Enlarged traces of IJPs at faster sweep speeds are shown on the right. ***P ≤ 0.001, significantly different than control by one-way ANOVA.

EFS during the plateau phase of slow waves evoked frequency-dependent large amplitude IJPs that disrupted slow waves and repolarized membrane potential close to the level of RMP, but slow waves resumed upon the break of the stimulus (Fig. 3A). The IJPs also interrupted phasic contractions (Fig. 3A). Contractile responses recovered, as did slow waves, upon the break of the stimulus. Following EFS, the phasic contractions were reduced in amplitude to 0.34 ± 0.03 mN for one to three cycles before returning to prestimulus conditions (Fig. 2B).

Postjunctional inhibitory responses were analyzed by sequential elimination of components attributed to NO and purines. l-NNA (100 μM) added in the continued presence of atropine and had no significant effect on spontaneous electrical parameters but increased the amplitude of contractions associated with each slow wave to 0.78 ± 0.04 mN (Figs. 2C and 3C). Between slow waves l-NNA had little or no effect on IJPs (Fig. 2, C and E) [amplitude = 8.0 ± 1.6 and 10.9 ± 2.0 mV in atropine (Fig. 2B) and 8.1 ± 1.2 and 11.6 ± 1.4 mV at 1 and 10 Hz in atropine and l-NNA (Fig. 2C)]. The most prominent effect of l-NNA on neural responses evoked during the diastolic phase between slow waves was the rapid rate-of-rise of the slow wave that was initiated upon the break of the stimulus (see Figs. 2C and 3C, right traces). The slow wave following EFS in l-NNA was associated with a greater contraction (i.e., 0.95 ± 0.05 mN). EFS during the plateau phase of slow waves continued to generate large amplitude IJPs after addition of l-NNA. These events caused hyperpolarization negative to RMP (at 5 and 10 Hz; Fig. 3, C and E; see Table 1). EFS also caused a termination of the phasic contraction associated with the IJP during the slow wave plateau. Upon cessation of EFS, rapid recovery of the slow wave plateau was initiated and a marked increase in the amplitude of contraction (to 1.5 ± 0.05 mN) immediately following EFS was observed (Fig. 3C, compare to A and B; Table 1; Figs. 2C and 3C, compare to Figs. 2, A and B, and 3, A and B). In the continued presence of atropine and l-NNA, postjunctional responses were also evoked after addition of the selective P2Y1 receptor antagonist MRS2500 (1 μM). MRS2500 inhibited IJPs evoked by EFS at 1 Hz and greatly attenuated IJPs at 10 Hz, during the diastolic phase between slow waves (Fig. 2, D and E). Relaxations or attenuation of slow waves immediately following EFS were not observed. MRS2500 also inhibited IJPs evoked at 1 Hz and attenuated IJPs at 10 Hz during the plateau phase (Fig. 3, D and E; Table 1). EFS at 10 Hz caused at slight attenuation in phasic contractions that immediately recovered following termination of EFS (Fig. 3D).

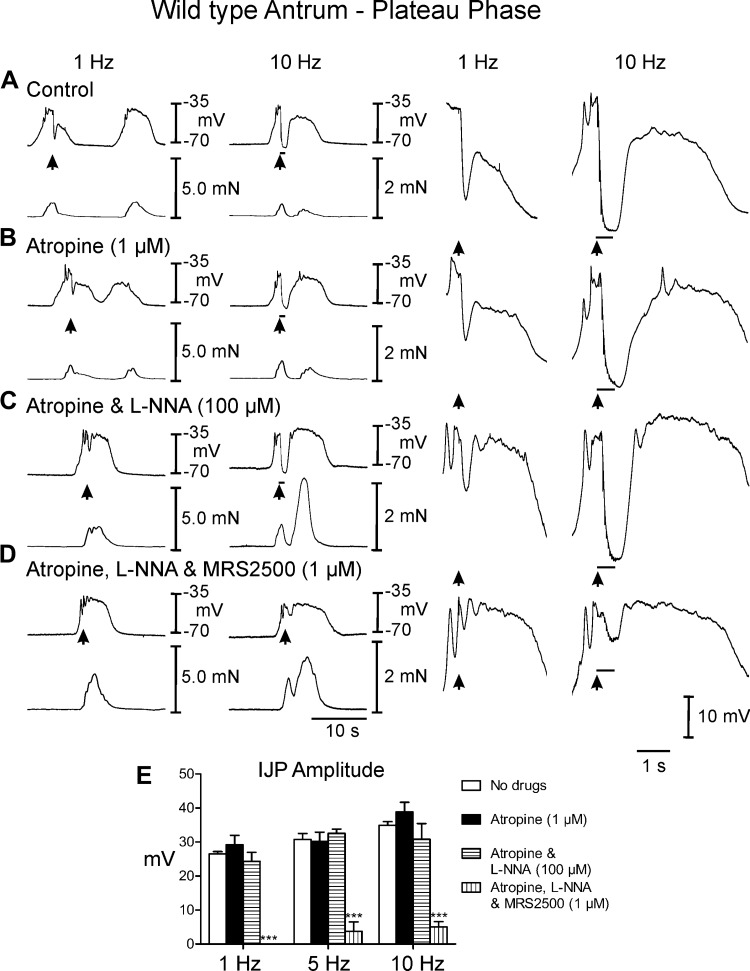

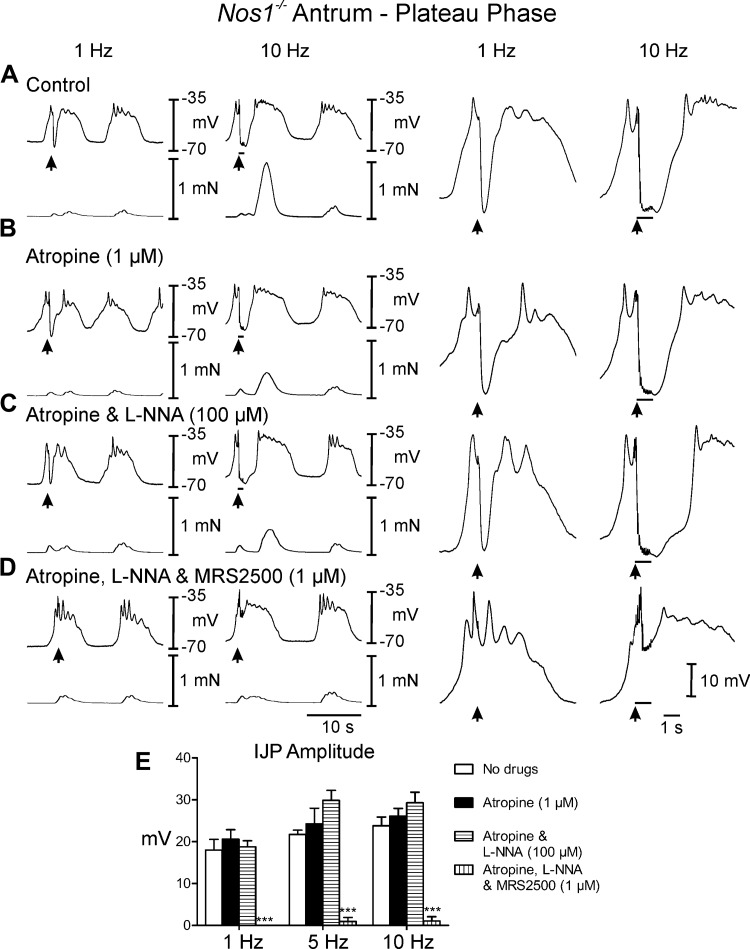

Postjunctional neural responses in the antrums of Nos1−/− mice.

EFS of antral muscles from Nos1−/− mice during the diastolic phase (under control conditions) caused IJPs that averaged 8.5 ± 0.8 mV in amplitude and 1.2 ± 0.1s in duration with 1 Hz and 8.6 ± 1.0 mV in amplitude and 1.4 ± 0.1 s duration at 10 Hz (Fig. 4, A and E). EFS during the plateau phase evoked frequency-dependent large amplitude IJPs that often terminated the slow wave (Fig. 5A). Conversely to wild-type mice, IJPs were not associated with relaxations during the diastolic phase but phasic contractions were inhibited during the plateau phase of the slow waves (0. 2 ± 0.02 mN). Following EFS, phasic contractions were increased in amplitude (0.95 ± 0.03 mN) for one or more cycles, before returning to prestimulus conditions (Figs. 4A and 5A). In atropine, post-EFS slow waves and associated phasic contractions were less robust than controls (Figs. 4, A and B, and 5, A and B). Addition of l-NNA (100 μM) in atropine displayed little or no effect on spontaneous electrical activity (Figs. 4C and 5C) and unlike wild-type control had little effect on phasic contraction amplitude (0.6 ± 0.04 mN). During the diastolic phase of membrane potential, l-NNA had little or no effect on the IJP [amplitude = 7.7 ± 0.8 and 8.8 ± 1.2 mV at 1 and 10 Hz in atropine (Fig. 4, B and E) and 7.6 ± 0.9 and 8.3 ± 1.1 mV in atropine and l-NNA (Fig. 4, C and E) at 1 and 10 Hz, respectively]. During the plateau phase large amplitude IJPs were still observed in response to EFS in the presence of l-NNA, which caused the membrane to hyperpolarize to more negative potentials than diastolic potentials (at 5 and 10 Hz, Fig. 5, C and E; Table 1). MRS2500 inhibited the IJP during the diastolic phase at 1 and 10 Hz. During the plateau phase MRS2500 also abolished the IJP at 1 Hz and greatly attenuated the IJP at 10 Hz (Fig. 4, D and E, and 5, D and E; Table 1). Phasic contractions were not significantly affected by EFS under these conditions (Figs. 4D and 5D).

Fig. 4.

Postjunctional neural responses of Nos-1−/− gastric antrum to EFS during the diastolic phase of membrane potential. A: EFS at 1 and 10 Hz (arrows and horizontal bars) under control conditions produced pronounced IJPs and an enhanced poststimulus contraction. B: in the presence of atropine postjunctional inhibitory responses and poststimulus contractions were similar to or slightly reduced to control, including rate of rise of the upstroke component. C: l-NNA had little or no effect on neural responses. D: MRS2500, in atropine and l-NNA, inhibited the IJP and the enhanced poststimulus contraction. E: summary data of the effects of different experimental conditions on IJP amplitude. Electrical activity is shown in the top trace and mechanical activity in the bottom trace in A–D. Enlarged traces of IJPs at faster sweep speeds are shown on the right. ***P ≤ 0.001, significantly different than control by one-way ANOVA.

Fig. 5.

Postjunctional neural responses of Nos-1−/− gastric antrum to EFS during the plateau phase of slow waves. A: EFS at 1 and 10 Hz (arrows and horizontal bars) under control conditions produced large IJPs and an enhanced poststimulus contraction. B: in the presence of atropine postjunctional inhibitory responses and contractions were similar to or slightly reduced to control conditions, including the rate of rise of the upstroke component. C: l-NNA had little or no effect on inhibitory neural responses or poststimulus contractions. D: MRS2500, in atropine and l-NNA, inhibited the IJP at 1 Hz and greatly attenuated the response at 10 Hz. Enhanced poststimulus contractions were blocked by MRS2500. E: summary data of the effects of different experimental conditions on IJP amplitude. Electrical activity is shown in the top trace and mechanical activity in the bottom trace in A–D. Enlarged traces of IJPs at faster sweep speeds are shown on the right. ***P ≤ 0.001, significantly different than control by one-way ANOVA.

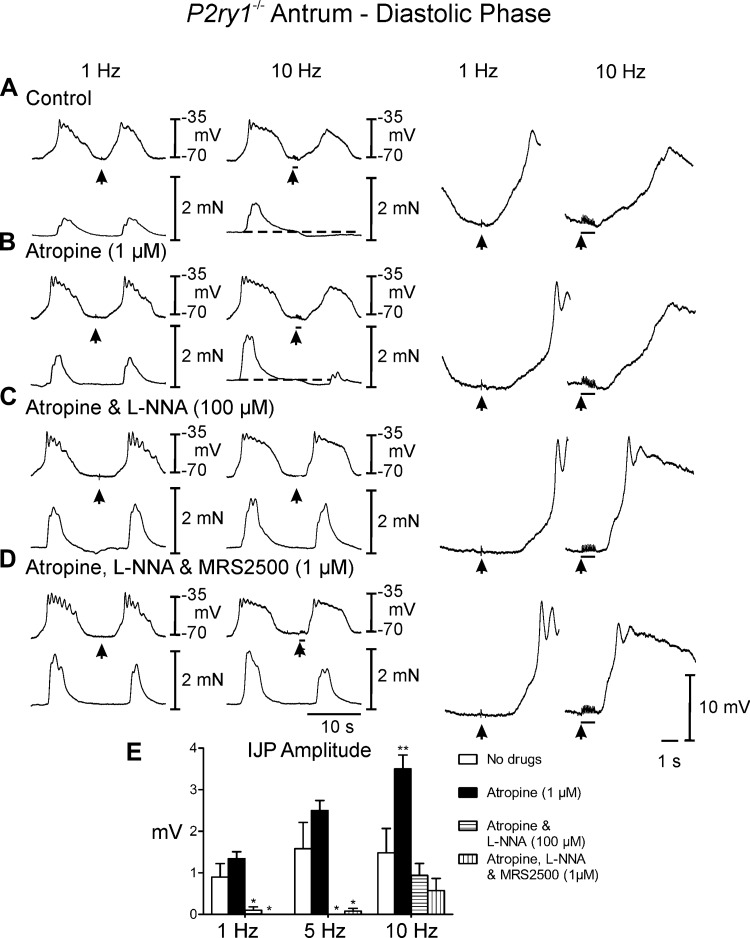

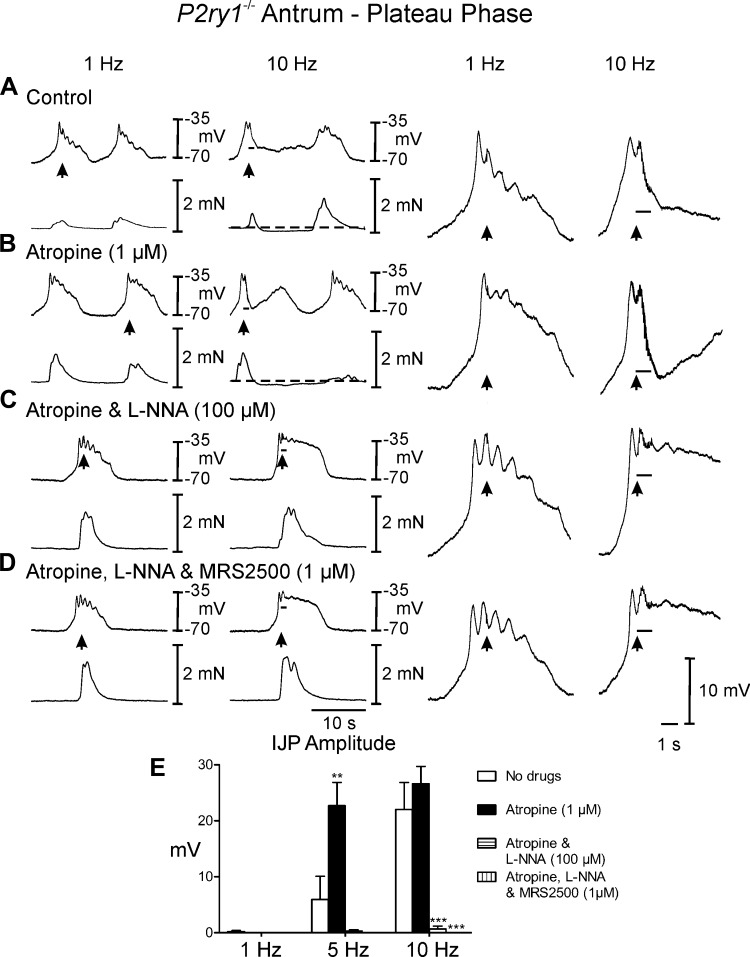

Postjunctional neuronal responses in gastric antrums of P2ry1−/− mice.

EFS of P2ry1−/− muscles between slow waves evoked none or only small IJP responses. For example, IJPs 0.9 ± 0.3 mV in amplitude and 0.2 ± 0.2s in duration were recorded at 1 Hz and 1.5 ± 0.6 mV in amplitude and 1.7 ± 0.8 s duration at 10 Hz (Fig. 6A). However, frequency-dependent relaxations averaging 0.2 ± 0.01 mN below baseline were observed following EFS delivered during the diastolic phase (Fig. 7A). Slow waves following EFS were attenuated at 5–10 Hz and these did not produce a contraction or initiated a contraction of reduced amplitude. EFS during the plateau phase of slow waves evoked frequency-dependent IJPs that interrupted the slow wave (5 and 10 Hz; Fig. 7A; 5 Hz not shown) and attenuated the associated phasic contraction (0.3 ± 0.02 mN). Atropine (1 μM) had no observable effect on spontaneous electrical or mechanical activity. However, unlike wild-type controls and Nos1−/− mice, atropine did have a significant effect on postjunctional neural responses (Figs. 6B and 7B; Table 1) and caused further inhibition of contractile activity for several cycles following EFS (Fig. 7B). Experiments were then performed in l-NNA (100 μM). l-NNA displayed little or no effect on spontaneous electrical parameters, but as with wild-type controls, markedly increased the amplitude of phasic contractions associated with each slow wave (0.9 ± 0.04 mN; Figs. 6C and 7C, compared with Figs. 6, A and B, and 7, A and B). Conversely to wild-type and Nos1−/− mice, during the diastolic phase of membrane potential, l-NNA significantly attenuated or abolished the IJP [amplitude = 1.3 ± 0.2 and 3.5 ± 0.3 mV in atropine (Fig. 6B) and 0.1 ± 0.1 and 0.9 ± 0.3 mV in atropine and l-NNA (Fig. 7B) at 1 and 10 Hz, respectively]. However, the amplitude and rate of rise of the upstroke of slow waves immediately following EFS were enhanced in l-NNA (Figs. 6C and 7C, right), supporting a role for NO in attenuating pacemaker activity (Fig. 6C, compare with Fig. 6, A and B). During the plateau phase IJPs were absent in P2ry1−/− mice in l-NNA (Fig. 7C). MRS2500 did not further affect spontaneous electrical and mechanical activity or neural responses compared with those recorded in atropine and l-NNA (Figs. 6D and 7D).

Fig. 6.

Postjunctional neural responses of gastric antrum from P2ry1−/− during the diastolic phase of membrane potential. A: EFS at 1 and 10 Hz (arrows) during the diastolic phase of membrane potential did not elicit IJPs at either 1 or 10 Hz. At 10 Hz the slow wave following EFS was attenuated but the associated contraction was absent (dashed line). B: atropine (1 μM) had little effect on EFS evoked neural responses compared with control recordings. C: addition of l-NNA (100 μM) in atropine did not affect the fIJP at 1 or 10 Hz but blocked the attenuation in the slow wave and inhibited the relaxation following EFS. D: MRS2500 (1 μM) in atropine and l-NNA did not affect electrical or mechanical responses at 1 Hz or 10 Hz compared with l-NNA and atropine alone. Dashed lines indicate change in baseline isometric force. E: summary data of the effects of different experimental conditions on IJP amplitude. Electrical activity is shown in the top trace and mechanical activity in the bottom trace in A–d. Enlarged traces of IJPs at faster sweep speeds are shown on the right. *P ≤ 0.05, **P ≤ 0.01, significantly different than control by one-way ANOVA.

Fig. 7.

Neural responses of P2ry1−/− gastric antrum during the plateau phase of slow waves. A: EFS at 1 Hz (arrow) during the plateau phase of membrane potential did not elicit an IJP. At 10 Hz EFS caused a reduction in the duration of the plateau phase of the slow wave during EFS, terminated the associated contraction and produced a relaxation of the circular layer (dashed lines). B: atropine (1 μM) did not alter or slightly potentiated the EFS evoked inhibitory responses compared with control conditions (dashed lines). C: addition of l-NNA (100 μM) in atropine relieved the attenuation in the slow wave plateau and the relaxation following EFS. D: MRS2500 (1 μM) in atropine and l-NNA did not affect electrical or mechanical responses at 1 Hz or 10 Hz compared with l-NNA and atropine alone. E: summary data of IJP amplitude under different experimental conditions. Electrical activity is shown in the top trace and mechanical activity in the bottom trace in A–E. Dashed lines indicate change in basal isometric force. Enlarged traces of IJPs at faster sweep speeds are shown on the right. **P ≤ 0.01, ***P ≤ 0.001, significantly different than control by one-way ANOVA.

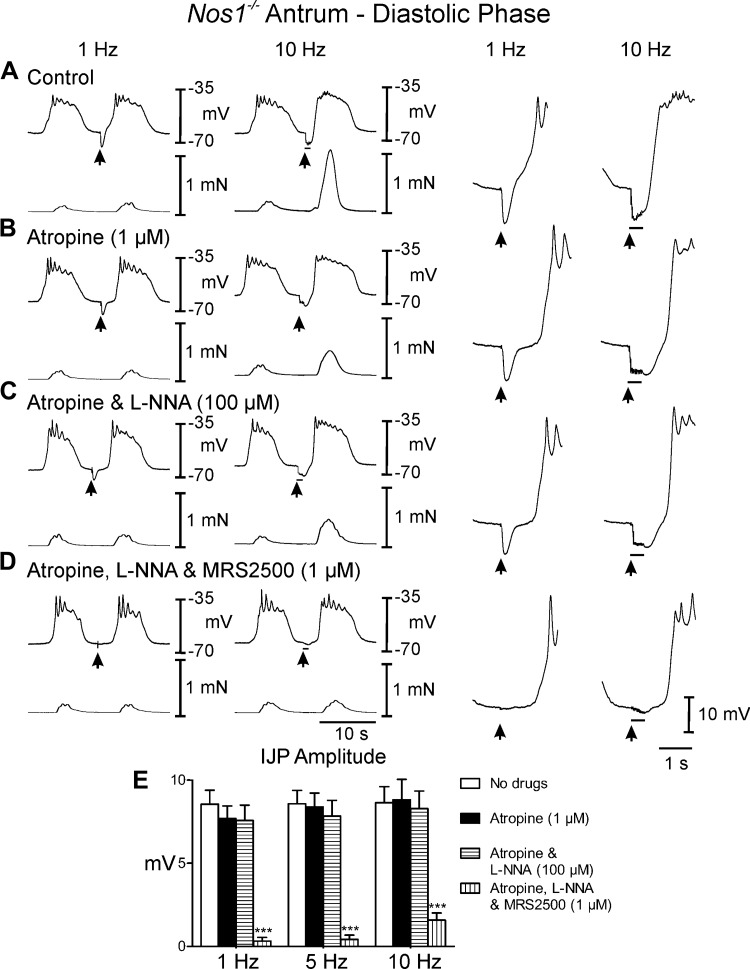

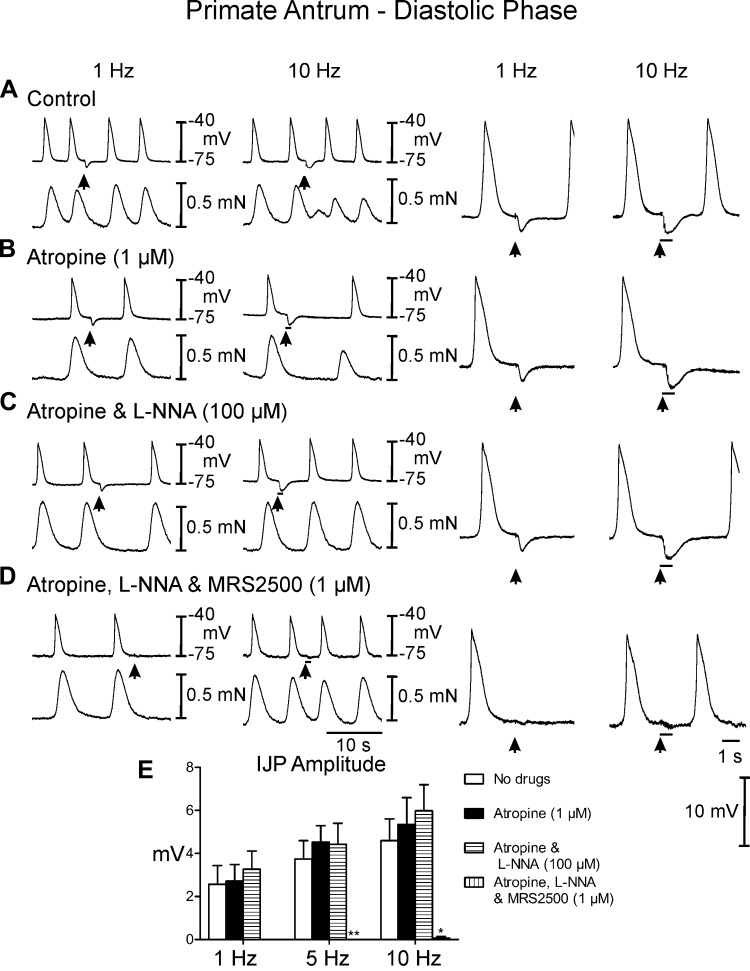

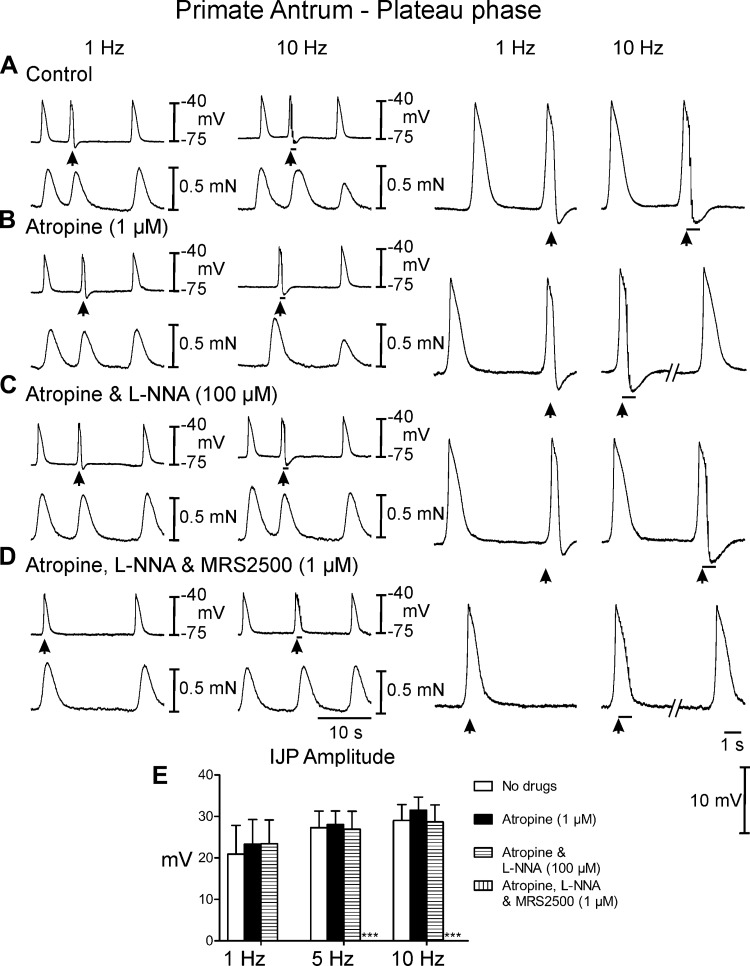

Postjunctional neuronal responses in antrums of cynomolgus monkey.

EFS of antral muscles of Cynomolgus monkeys between slow waves evoked IJPs that averaged 2.6 ± 0.9 mV in amplitude and 1.2 ± 0.1 s in duration with 1 Hz and 4.6 ± 1.0 mV in amplitude and 3.9 ± 1.3 s duration at 10 Hz (Fig. 8A). EFS during the plateau phase of slow waves evoked frequency-dependent large amplitude IJPs that interrupted the slow wave (Fig. 9A). IJPs were associated with a frequency-dependent reduction in the amplitude of phasic contractions following EFS (reduced to 0.3 ± 0.01 mN at 10 Hz; P < 0.05 compared with the contraction before EFS) that lasted several cycles before returning to prestimulus levels. Atropine had little or no effect on spontaneous electrical activity or postjunctional electrical and mechanical responses to EFS at any frequency examined (Figs. 8A and 9A). The effects of l-NNA were tested, in the continued presence of atropine. l-NNA had no significant effect on spontaneous slow wave activity (Figs. 8C and 9C, compare with Figs. 8, A and B, and 9, A and B) and no effect on IJPs evoked between slow waves (Table 1). Phasic contractions were more regular in l-NNA (0.75 ± 0.04 mN) and l-NNA inhibited the reduction in phasic contractions following EFS (0.6 ± 0.03 mN). Large amplitude IJPs were evoked by EFS during the plateau phase of the slow wave in the presence of l-NNA, and in most cases this resulted in hyperpolarization negative to RMP (Fig. 9C). l-NNA did not have a significant effect on the next slow wave following EFS, but also inhibited the reduction in phasic contractions associated with the slow waves following EFS. (Figs. 8C and 9C, compare with Figs. 8, A and B, and 9, A and B). MRS2500 was added in addition to atropine and l-NNA to determine the role of P2Y1R in the remaining inhibitory responses. MRS2500 (1 μM) inhibited IJPs evoked between slow waves by 1- and 10-Hz EFS (Fig. 8D). MRS2500 abolished the IJP evoked during the plateau phase by 1- and 10-Hz EFS (Fig. 9D). MRS2500 also inhibited any remaining reduction in phasic contractions (Figs. 8D and 9C).

Fig. 8.

Postjunctional neural responses of the monkey antrum during the diastolic phase of membrane potential. A: EFS at 1 and 10 Hz (arrows and horizontal bars) during the interslow wave period produced a fIJP. The interslow wave period and associated contractions were increased following EFS and at 10 Hz the phasic contractions following EFS were reduced in amplitude for several cycles. B: in atropine there was little change in the fIJP, the inter-slow wave period and phasic contractions were still increased in duration following EFS. C: l-NNA (100 μM) in the presence of atropine did not reduce the fIJP at 1 or 10 Hz or the increase in duration of the inter-slow wave period but abolished the attenuation of phasic contractions following EFS. D: MRS2500 (1 μM) in atropine and l-NNA abolished the fIJP at 1 Hz and 10 Hz and the increase in interslow wave duration. E, Summary of the IJP amplitude under different experimental conditions. Electrical activity is shown in the top trace and mechanical activity in the bottom trace in A–D. Enlarged traces of IJPs at faster sweep speeds are shown on the right. *P ≤ 0.05 and **P ≤ 0.001; significantly different than control by one-way ANOVA.

Fig. 9.

Neural responses of the monkey antrum to EFS during the plateau phase of slow waves. A: EFS at 1 and 10 Hz (arrows and horizontal bars) delivered during the slow wave plateau phase caused a rapid termination of the slow wave, a poststimulus IJP and an increase in inter-slow wave duration. Phasic contractions following EFS were attenuated particularly at higher frequencies. B: atropine did not alter EFS evoked electrical or mechanical responses compared with control recordings. C: l-NNA (100 μM) with atropine did not affect EFS evoked termination in slow waves or the increase in inter-slow wave duration but reduced the inhibition of contractions after EFS. D: MRS2500 (1 μM) in atropine and l-NNA abolished the EFS (1 and 10 Hz) evoked repolarization of slow waves and fIJP following slow waves and the increased inter-slow wave duration following EFS. E: summary of postjunctional responses under different experimental conditions. Electrical activity is shown in the top trace and mechanical activity in the bottom trace in A–D. Dashed lines represent a break in the trace in B and D shown at left. Enlarged traces of IJPs at faster sweep speeds are shown on the right. ***P ≤ 0.001, significantly different than control by one-way ANOVA.

DISCUSSION

In the present study we examined the convergence and complimentarily of nitrergic and purinergic inhibitory neural pathways in the regulation of gastric motor activity in rodent and non-human primate animal models. These two inhibitory components played distinctly different roles in regulating postjunctional electrical and mechanical responses. The nitrergic component produced a prominent relaxation or termination of phasic contractile activity with little change in electrical activity whereas the purinergic component produced a dominant inhibitory membrane hyperpolarization or inhibitory junction potential (IJP) while producing modest effects on relaxation responses.

To dissect out the major components of postjunctional inhibitory responses we utilized two genetically different models that lacked Nos1 or neuronal NO synthase (nNOS) and P2Y1 receptors. Data obtained from these mutants was supported by serial pharmacological blockade of muscarinic cholinergic excitatory receptors with atropine, followed by nitrergic and finally purinergic inhibitory responses using l-NNA and MRS2500, pharmacological agents directed against NO synthase and P2Y1 receptors, respectively. The contribution of converging inhibitory inputs in genetic models was extrapolated to Cynomolgus monkey (Macaca fascicularis). Interestingly, the contribution of NO and purine components to inhibitory responses were highly conserved between mouse and primate stomachs, as NO produced a dominant relaxation with slight membrane potential change whereas purines produced significant IJPs with modest relaxations in monkey stomach. Serial pharmacological blockade that was performed in the present study ruled out contribution of cholinergic nerves when inhibitory nerves were dominant under control conditions. Cholinergic input to antral muscle is significant but not dominant when inhibitory nerves are functional.

The importance of coordinated motor innervation of the distal stomach for gastric emptying of humans and animal models is reasonably well understood (50). In animal models, genetically engineered deletion of genes encoding the synthesis of inhibitory neurotransmitters such as NO can lead to antral muscle thickening, gastric dilation, delayed gastric emptying, and bezoar formation (30, 40). In humans, specific gene deletion is not possible; however, when the distal stomach is denervated or pyloroplasty has been performed, gastric emptying is uncontrolled (50).

The role of NO as an inhibitory neurotransmitter in the gastrointestinal tract has received significant attention since its discovery (3) and studies have examined its functional role in gastric motor activity (14, 23). However, many of these studies have concentrated on its role in gastric accommodation reflexes of the proximal stomach (7, 8, 27) and only few studies have focused on the endogenous role of NO on antral motor activity. It has been shown that the nitric oxide synthase antagonist l-NG-monomethyl-arginine (l-NMMA) increased the force of contractions in the canine antrum and that the effects of l-NMMA were antagonized by the substrate for NOS, l-arginine (33). Spontaneous relaxations of the anesthetized rat antrum were NO dependent (14) and suppression of NO transmission in rats and dogs causes disruption of gastric migrating motor complexes (14, 32). A similar decrease in antral motor activity and inhibition in gastric emptying was observed in human stomach (23). It has also been suggested that neuronally derived NO positively regulates the survival of interstitial cells of Cajal (ICC) in the mouse stomach (5). In the absence of nNOS, we have shown in this study that gastric slow wave frequency was higher compared with wild-type and P2yr1−/− mice. The smaller amplitude slow waves in nNOS mice are likely due to the more depolarized membrane potential in these antral tissues (42). Thus, in the absence of nNOS, ICC function effectively in pacemaking.

The relaxation effects of purines on the terminal stomach have also been investigated but the majority of these studies have concentrated on the pyloric sphincter (41). Concentration-relaxation responses were investigated for the exogenous application of the purine adenosine 5′-triphosphate (ATP) and its two analogs, 2-methylthioATP (2-MeSATP) and α,β-methyleneATP (α,β-MeATP). The order of potency for relaxations was reported as 2-MeSATP > ATP > > α,β-MeATP. Based on these findings it was concluded that ATP acting, through P2Y-purinoceptors, contributes to inhibitory neurotransmission in rat pylorus (41). Apamin, a known inhibitor of purine-mediated membrane hyperpolarization and relaxation by blocking small conductance (SK) potassium channels (also known as KCNN1-3; Ref. 29), caused reduction in inhibitory responses in the guinea-pig (6). A combination of NOS inhibition and purinoreceptor blockade significantly reduced inhibitory responses in the pyloric sphincter. More recently, the role of P2Y1 receptors in mediating the purine component of the nerve-evoked membrane hyperpolarization or IJP was identified in the colon, cecum, and stomach (11, 13, 18). The transient fIJP was absent in the colons of P2ry1−/− mice and inhibited by MRS2500. It was further shown that in P2ry1−/− mice or by MRS2500 colonic pellet transit, particularly in the distal colon where purine responses dominate, was significantly reduced (18).

Nos1−/− mice have delayed gastric emptying and the stomachs of these mutants appear dilated compared with wild-type controls (30). Gastric distension was also observed in Nos1−/ mice in the present study. Interestingly, the delayed gastric emptying and distension did not appear to be a consequence of luminal narrowing of the pyloric sphincter but there was marked hypertrophy of the circular muscle in the antrum. This phenotype is distinctly different than the pyloric occlusion observed in patients with idiopathic pyloric stenosis, which is limited to pylorus (34, 36) and is reported to be a consequence of loss of NOS immunopositive nerves (1) and ICC (26, 46). Unlike Nos1−/− mice, there was no observable stomach distension in P2ry1−/− mice compared with controls. Gastric emptying studies need to be performed to determine if genetic deletion of P2Y1 purinoreceptors affects gastric emptying.

Specific classes of interstitial cells ICC and interstitial cells that express platelet-derived growth factor receptor α (PDGFRα+ interstitial cells) play an important role in neuroeffector signal communication in the gastrointestinal tract (2, 4, 25, 47, 48). Intramuscular ICC (ICC-IM) have been shown to be mediators in cholinergic and nitrergic signaling (4, 43, 47, 49) whereas PDGFRα+ cells are involved in purinergic signaling (2, 25, 35). ICC and PDGFRα+ cells form gap junctions with each other and with neighboring smooth muscle cells (17, 22), and it is thought that this is the cellular mechanism of how motor transmission signals are conveyed from nerve terminals to smooth muscle cells via interstitial cells (47). Whether the signaling mechanism(s) between interstitial cells and smooth muscle cells is purely electrical or involves diffusible substances remains to be determined. Some investigators have argued against a role of interstitial cells in motor neurotransmission (15); however, recent genetic studies where ICC have been disrupted conditionally have provided convincing evidence for an involvement in neuroeffector transmission in the gut (16, 28).

In summary, with the use of mice with genetic deletions in components of inhibitory neurotransmitter signaling and pharmacological agents, the present study identifies a convergence of distinct inhibitory neurotransmitters that produces a combined relaxation response in the gastric antrum. NO produces a dominant relaxation with subtle hyperpolarization in membrane potential whereas a purine inhibitory response consists of a robust membrane hyperpolarization with modest relaxation. The convergence of inhibitory postjunctional responses were conserved between rodent and primate stomachs suggesting that the contribution of both NO and purine components of inhibitory postjunctional responses are fundamental to coordinated gastric motor activity.

GRANTS

These studies were supported by National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases Grants DK-57236 (to S. M. Ward) P01-DK-41315 (to S. M. Ward and K. M. Sanders). L. Shaylor was supported by the Michael (Mick) J. M. Hitchcock, Ph.D. Graduate Student Research Fund.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

L.A.S., S.J.H., and S.M.W. conception and design of research; L.A.S. and S.J.H. performed experiments; L.A.S. and S.J.H. analyzed data; L.A.S., S.J.H., K.M.S., and S.M.W. interpreted results of experiments; L.A.S. and S.J.H. prepared figures; L.A.S., S.J.H., K.M.S., and S.M.W. drafted manuscript; L.A.S., K.M.S., and S.M.W. edited and revised manuscript; K.M.S. and S.M.W. approved final version of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We acknowledge Charles River Laboratories for providing primate tissues and Nancy Horowitz and Lauren Peri for maintenance of the colonies and genotyping of mice.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abel RM, Bishop AE, Dore CJ, Spitz L, Polak JM. A quantitative study of the morphological and histochemical changes within the nerves and muscle in infantile hypertrophic pyloric stenosis. J Pediatr Surg 33: 682–687, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baker SA, Hennig GW, Salter AK, Kurahashi M, Ward SM, Sanders KM. Distribution and Ca(2+) signalling of fibroblast-like PDGFR(+) cells in the murine gastric fundus. J Physiol 591: 6193–6208, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bult H, Boeckxstaens GE, Pelckmans PA, Jordaens FH, Van Maercke YM, Herman AG. Nitric oxide as an inhibitory non-adrenergic non-cholinergic neurotransmitter. Nature 345: 346–347, 1990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Burns AJ, Lomax AE, Torihashi S, Sanders KM, Ward SM. Interstitial cells of Cajal mediate inhibitory neurotransmission in the stomach. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 93: 12008–12013, 1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Choi KM, Gibbons SJ, Roeder JL, Lurken MS, Zhu J, Wouters MM, Miller SM, Szurszewski JH, Farrugia G. Regulation of interstitial cells of Cajal in the mouse gastric body by neuronal nitric oxide. Neurogastroenterol Motil 19: 585–595, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Costa M, Furness JB, Humphreys CM. Apamin distinguishes two types of relaxation mediated by enteric nerves in the guinea-pig gastrointestinal tract. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol 332: 79–88, 1986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Desai KM, Sessa WC, Vane JR. Involvement of nitric oxide in the reflex relaxation of the stomach to accommodate food or fluid. Nature 351: 477–479, 1991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Desai KM, Zembowicz A, Sessa WC, Vane JR. Nitroxergic nerves mediate vagally induced relaxation in the isolated stomach of the guinea pig. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 88: 11490–11494, 1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fabre JE, Nguyen M, Latour A, Keifer JA, Audoly LP, Coffman TM, Koller BH. Decreased platelet aggregation, increased bleeding time and resistance to thromboembolism in P2Y1-deficient mice. Nat Med 5: 1199–1202, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Francis SH, Busch JL, Corbin JD, Sibley D. cGMP-dependent protein kinases and cGMP phosphodiesterases in nitric oxide and cGMP action. Pharmacol Rev 62: 525–563, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gallego D, Gil V, Martínez-Cutillas M, Mañé N, Martín MT, Jiménez M. Purinergic neuromuscular transmission is absent in the colon of P2Y(1) knocked out mice. J Physiol 590: 1943–1956, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gallego D, Hernández P, Clavé P, Jiménez M. P2Y1 receptors mediate inhibitory purinergic neuromuscular transmission in the human colon. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 291: G584–G594, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gil V, Martínez-Cutillas M, Mañé N, Martín MT, Jiménez M, Gallego D. P2Y(1) knockout mice lack purinergic neuromuscular transmission in the antrum and cecum. Neurogastroenterol Motil 25: e170–182, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Glasgow I, Mattar K, Krantis A. Rat gastroduodenal motility in vivo: involvement of NO and ATP in spontaneous motor activity. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 275: G889–G896, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Goyal RK, Chaudhury A. Mounting evidence against the role of ICC in neurotransmission to smooth muscle in the gut. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 298: G10–G13, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Groneberg D, Zizer E, Lies B, Seidler B, Saur D, Wagner M, Friebe A. Dominant role of interstitial cells of Cajal in nitrergic relaxation of murine lower oesophageal sphincter. J Physiol 593: 403–414, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Horiguchi K, Komuro T. Ultrastructural observations of fibroblast-like cells forming gap junctions in the W/W(nu) mouse small intestine. J Auton Nerv Syst 80: 142–147, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hwang SJ, Blair PJ, Durnin L, Mutafova-Yambolieva V, Sanders KM, Ward SM. P2Y1 purinoreceptors are fundamental to inhibitory motor control of murine colonic excitability and transit. J Physiol 590: 1957–1972, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Iino S, Horiguchi K, Nojyo Y, Ward SM, Sanders KM. Interstitial cells of Cajal contain signalling molecules for transduction of nitrergic stimulation in guinea pig caecum. Neurogastroenterol Motil 21: 542–50, e12-3, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Keef KD, Du C, Ward SM, McGregor B, Sanders KM. Enteric inhibitory neural regulation of human colonic circular muscle: role of nitric oxide. Gastroenterology 105: 1009–1016, 1993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Keef KD, Saxton SN, McDowall RA, Kaminski RE, Duffy AM, Cobine CA. Functional role of vasoactive intestinal polypeptide in inhibitory motor innervation in the mouse internal anal sphincter. J Physiol 591: 1489–1506, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Komuro T. Comparative morphology of interstitial cells of Cajal: ultrastructural characterization. Microsc Res Tech 47: 267–285, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Konturek JW, Thor P, Domschke W. Effects of nitric oxide on antral motility and gastric emptying in humans. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 7: 97–102. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kunze WA, Furness JB. The enteric nervous system and regulation of intestinal motility. Annu Rev Physiol 61: 117–142, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kurahashi M, Mutafova-Yambolieva V, Koh SD, Sanders KM. Platelet-derived growth factor receptor-α-positive cells and not smooth muscle cells mediate purinergic hyperpolarization in murine colonic muscles. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 307: C561–C570, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Langer JC, Berezin I, Daniel EE. Hypertrophic pyloric stenosis: ultrastructural abnormalities of enteric nerves and the interstitial cells of Cajal. J Pediatr Surg 30: 1535–1543, 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lefebvre RA, Baert E, Barbier AJ. Influence of NG-nitro-l-arginine on non-adrenergic non-cholinergic relaxation in the guinea-pig gastric fundus. Br J Pharmacol 106: 173–179, 1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lies B, Gil V, Groneberg D, Seidler B, Saur D, Wischmeyer E, Jiménez M, Friebe A. Interstitial cells of Cajal mediate nitrergic inhibitory neurotransmission in the murine gastrointestinal tract. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 307: G98–G106, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Litt M, LaMorticella D, Bond CT, Adelman JP. Gene structure and chromosome mapping of the human small-conductance calcium-activated potassium channel SK1 gene (KCNN1). Cytogenet Cell Genet 86: 70–73, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mashimo H, Kjellin A, Goyal RK. Gastric stasis in neuronal nitric oxide synthase-deficient knockout mice. Gastroenterology 119: 766–773, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mutafova-Yambolieva VN, Hwang SJ, Hao X, Chen H, Zhu MX, Wood JD, Ward SM, Sanders KM. Beta-nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide is an inhibitory neurotransmitter in visceral smooth muscle. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 104: 16359–16364, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ohta D, Lee CW, Sarna SK, Condon RE, Lang IM. Central inhibition of nitric oxide synthase modulates upper gastrointestinal motor activity. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 272: G417–G424, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ozaki H, Blondfield DP, Hori M, Publicover NG, Kato I, Sanders KM. Spontaneous release of nitric oxide inhibits electrical, Ca2+ and mechanical transients in canine gastric smooth muscle. J Physiol 445: 231–247, 1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Peeters B, Benninga MA, Hennekam RC. Infantile hypertrophic pyloric stenosis–genetics and syndromes. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 9: 646–660, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Peri LE, Sanders KM, Mutafova-Yambolieva VN. Differential expression of genes related to purinergic signaling in smooth muscle cells, PDGFRα-positive cells, and interstitial cells of Cajal in the murine colon. Neurogastroenterol Motil 25: e609–620, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Peters B, Oomen MWN, Bakx R, Benninga MA. Advances in infantile hypertrophic pyloric stenosis. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 8: 533–541, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sanders KM, Ward SM. Nitric oxide as a mediator of nonadrenergic noncholinergic neurotransmission. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 262: G379–G392, 1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schlossmann J, Feil R, Hofmann F. Insights into cGMP signalling derived from cGMP kinase knockout mice. Front Biosci 10: 1279–1289, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shuttleworth CW, Xue C, Ward SM, De Vente J, Sanders KM. Immunohistochemical localization of 3′,5′-cyclic guanosine monophosphate in the canine proximal colon: Responses to nitric oxide and electrical stimulation of enteric inhibitory neurons. Neuroscience 56: 513–522, 1993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sivarao DV, Mashimo H, Goyal RK. Pyloric sphincter dysfunction in nNOS−/− and W/Wv mutant mice: animal models of gastroparesis and duodenogastric reflux. Gastroenterology 135: 1258–1266, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Soediono P, Burnstock G. Contribution of ATP and nitric oxide to NANC inhibitory transmission in rat pyloric sphincter. Br J Pharmacol 113: 681–686, 1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Suzuki H, Kito Y, Hashitani H, Nakamura E. Factors modifying the frequency of spontaneous activity in gastric muscle. J Physiol 576: 667–674, 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Suzuki H, Ward SM, Bayguinov YR, Edwards FR, Hirst GDS. Involvement of intramuscular interstitial cells in nitrergic inhibition in the mouse gastric antrum. J Physiol 546: 751–763, 2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Thornbury KD, Ward SM, Dalziel HH, Carl A, Westfall DP, Sanders KM. Nitric oxide and nitrosocysteine mimic nonadrenergic, noncholinergic hyperpolarization in canine proximal colon. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 261: G553–G557, 1991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Torphy TJ, Fine CF, Burman M, Barnette MS, Ormsbee HS. Lower esophageal sphincter relaxation is associated with increased cyclic nucleotide content. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 251: G786–G793, 1986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Vanderwinden JM, Liu H, De Laet MH, Vanderhaeghen JJ. Study of the interstitial cells of Cajal in infantile hypertrophic pyloric stenosis. Gastroenterology 111: 279–288, 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ward SM, Beckett EA, Wang X, Baker F, Khoyi M, Sanders KM. Interstitial cells of Cajal mediate cholinergic neurotransmission from enteric motor neurons. J Neurosci 20: 1393–1403, 2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ward SM, Sanders KM. Interstitial cells of Cajal: primary targets of enteric motor innervation. Anat Rec 262: 125–135, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ward SM, Sanders KM. Involvement of intramuscular interstitial cells of Cajal in neuroeffector transmission in the gastrointestinal tract. J Physiol 576: 675–682, 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.White CM, Poxon V, Alexander-Williams J. The importance of the distal stomach in gastric emptying of liquids in man. Surg Gastroenterol 3: 13–20, 1984. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]