Abstract

Background

The objective of this study was to evaluate the cerebral perfusion of the basal ganglia in infants with hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy (HIE) receiving hypothermia using dynamic color Doppler sonography (CDS) and investigate for any correlation between these measurements and survival.

Methods

Head ultrasound (HUS) was performed with a 9S4 MHz sector transducer in HIE infants submitted to hypothermia as part of their routine care. Measurements of cerebral perfusion intensity (CPI) with an 11LW4 MHz linear array transducer were performed to obtain static images and DICOM color Doppler videos of the blood flow in the basal ganglia area. Clinical and radiological data were evaluated retrospectively. The video images were analyzed by two radiologists using dedicated software, which allows automatic quantification of color Doppler data from a region of interest (ROI) by dynamically assessing color pixels and flow velocity during the heart cycle. CPI is expressed in cm/sec and is calculated by multiplying the mean velocity of all pixels divided by the area of the ROI. Three videos of 3 seconds each were obtained of the ROI, in the coronal plane, and used to calculate the CPI. Data are presented as mean ± SEM or median (quartiles).

Results

A total of 28 infants were included in this study: 16 male, 12 female. HUS was performed within the first 48 hours of therapeutic hypothermia treatment. CPI values were significantly higher in the seven non-survivors when compared to survivors (0.226±0.221 vs. 0.111±0.082 cm/sec; P=0.02).

Conclusions

Increased perfusion intensity of the basal ganglia area within the first 48 of therapeutic hypothermia treatment was associated with poor outcome in neonates with HIE.

Keywords: Hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy (HIE), head ultrasound (HUS), infants, color Doppler sonography (CDS), hypothermia

Introduction

Neonatal hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy (HIE) is associated with high rates of morbidity and mortality. Approximately 1 million neonatal deaths have been reported throughout the world in infants with signs of asphyxia (1,2).The combined outcome of moderate to severe disability or death occurs in 53% to 61% of infants with moderate to severe HIE, even at state-of-the-art referral centers (3). The benefits of therapeutic hypothermia, as a neuroprotective strategy that improves death and/or disability in neonates with moderate to severe HIE, have been shown in several randomized control trials. Currently, therapeutic hypothermia is the standard of care in most centers worldwide (3).

As a result of asphyxia the fetus suffers from hypoxia, hypercarbia and acidosis. This may lead to decreased cerebral blood flow due to a combination of abnormal cerebral auto-regulation and systemic hypotension, causing cerebral hypoperfusion and subsequent hypoxic-ischemic injury (HII) (4,5). In the post-asphyxiated period, an increase in cerebral blood flow may take place, within the first few hours of life, and may last of many hours or days. This period is known as reperfusion phase and may lead to secondary brain injury. An increased cerebral blood flow in the first day of life has been described in neonates with severe HII (1,5). A significant number of asphyxiated infants (35% to 85%) exhibit predominantly basal ganglia and thalamic involvement (6) and unfavorable neurological outcome have been described with injury to the deep cerebral grey matter (6,7). Therefore, quantification of brain perfusion, specifically of basal ganglia with dynamic color Doppler sonography (CDS) in this population, may be helpful in the assessment of reperfusion injury and has the potential to be used as a biomarker of severity of disease.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is the standard imaging modality of the brain in HIE infants (6,8). MRI provides anatomic and functional data that are important in the assessment of the severity of the disease and the prognosis. A spectrum of injury patterns, such as watershed or involvement of basal ganglia and thalami have been described. Head ultrasound (HUS) has been reported as less accurate than MRI but it is as a useful imaging modality due to the lack of ionizing radiation and the fact it can be performed at the bedside. A recent study suggests that HUS may be even a more effective modality in the assessment of HIE than it has been previously described (9). Therefore, HUS is a robust bedside screening modality in critically ill neonates.

Over the last years, we have developed experience with a non-invasive technique called Dynamic tissue perfusion measurement. This technique uses CDS to assess and quantify tissue perfusion (1,10), more specifically of the cerebral basal ganglia. It also provides dynamic blood flow data and perfusion velocity in a chosen region of interest (ROI) from a standard color Doppler video, without intravenous contrast injection.

Methods

Patient population

From September 2008 to November 2010, bedside HUS of HIE infants treated with whole body therapeutic hypothermia were performed by a single radiologist (RF), who was not aware of some relevant clinical data of these patients. HUS was done as part of standard of care. Institutional ethics approval was obtained to review the HUS studies and to extract clinical data of these infants. Clinical and radiological data were evaluated retrospectively.

The inclusion criteria were infants eligible for therapeutic hypothermia based on the same criteria used in the NICHD whole body hypothermia trial (3). Only infants with birth weight >1,800 g and gestational age ≥36 weeks were included. All infants underwent a standardized neurologic examination using the modified Sarnat score (3). Infants were candidates for hypothermia when moderate or severe encephalopathy (Sarnat score 2 and 3) was present. Infants admitted with more than 6 hours of life or major congenital abnormalities were not candidates to therapeutic hypothermia and therefore, excluded from the study.

Ultrasound technique and perfusion quantification

HUS was performed with a 9S4 MHz sector transducer in all HIE infants submitted to hypothermia within the first 48 hours, as part of their routine care. We used dynamic tissue perfusion measurement with CDS to obtain measurements of cerebral perfusion intensity (CPI) with an 11LW4 MHz linear array transducer. We obtained color Doppler videos of the blood flow in the basal ganglia in the coronal plane, with standardized CDS parameters (Color gain 40 and scale 7.5 cm/s). HUS was performed using a Toshiba Aplio XG unit (Toshiba Medical Systems, Japan). The video images were analyzed by two radiologists (RF and GC) using a dedicated software installed in an external workstation (Pixelflux Chameleon software, Germany), which allows automatic quantification of color Doppler data from a ROI. CPI is expressed in cm/sec. Three videos of 3 seconds each were obtained for the ROI, in each patient and used to calculate the mean CPI.

The method of dynamic tissue perfusion measurement quantifies tissue perfusion taking in consideration the amount of blood flow through a specific tissue during a cardiac cycle. Two important parameters are measured during the heart cycle: mean perfusion velocity of all vessels and mean perfused area. Therefore, reflecting the differences between systolic and diastolic perfusion in small vessels.

| Mean perfusion intensity (cm/s) = mean velocity of pixels (v) multiplied by area of all color pixels (A) divided by area of the ROI (AROI). |

According to this algorithm, a dynamic mean perfusion intensity is calculated for a specific tissue area with a standard ROI using acquired color Doppler videos (DICOM format), exported to a personal computer to be analyzed by a dedicated software (Pixelflux, Chameleon Software, Germany). Mean perfusion intensity is calculated by the software during a cardiac cycle and each time a measurement is made a result is provided in cm/s by an analysis panel. Perfusion curves are also provided. Color Doppler videos with major motion artifacts were excluded.

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as mean ± SD or median (interquartile). Categorical variables and CPI measurements of the basal ganglia area were compared between survivors and non-survivors, using the Student t-test. A P value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

HUS was performed in a total of 28 moderate (Figure 1) or severe HIE (Figure 2) infants treated with therapeutic hypothermia. Of these, seven infants expired due to progressive deterioration of their neurologic and clinical status. Patient demographics and clinical data during HUS study are presented on Tables 1 and 2, respectively. HIE infants that expired had lower cord pH and 10 min Apgar score, and higher Sarnat score at admission when compared to survivors. These infants were started on therapeutic hypothermia later than the survivors.

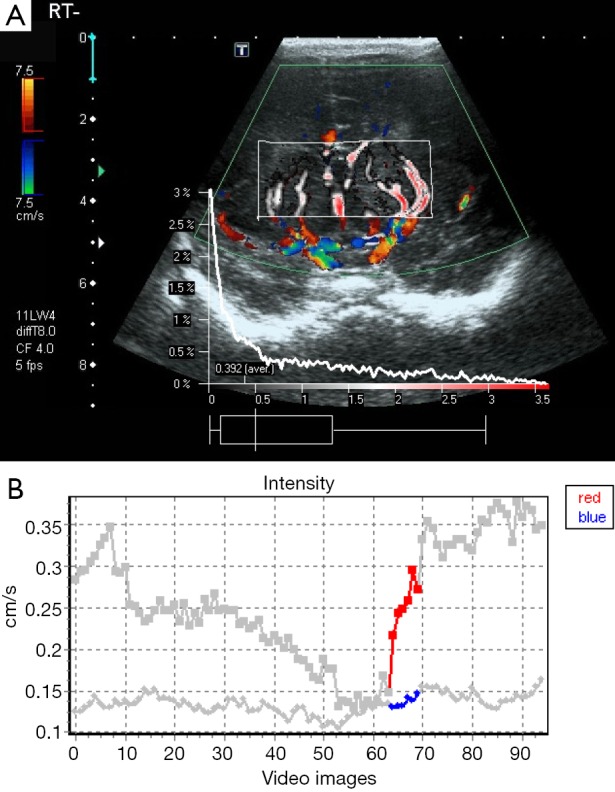

Figure 1.

A 1-day-old female infant with moderate HIE. Dynamic tissue perfusion measurement shows color Doppler image with ROI in basal ganglia to calculate cerebral perfusion intensity (CPI) (A), and corresponding perfusion intensity curve with perfusion up to 0.3 cm/s (B). HIE, hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy; ROI, region of interest.

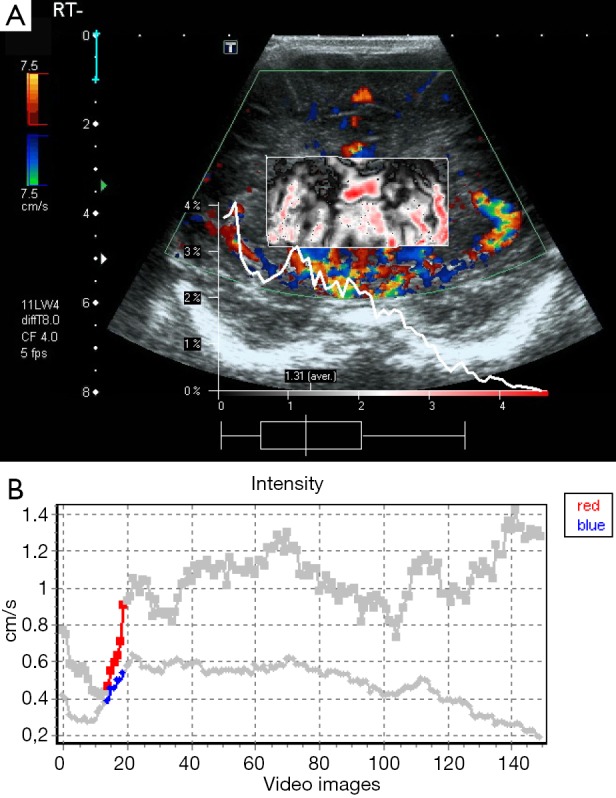

Figure 2.

A 1-day-old male infant with severe HIE. Dynamic tissue perfusion measurement demonstrates color Doppler image with ROI in the basal ganglia and very increased perfusion (A). Corresponding perfusion intensity curve with perfusion up to 0.9 cm/s (B). HIE, hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy; ROI, region of interest.

Table 1. Population characteristics.

| Population characteristics | Survivors | Died |

|---|---|---|

| Birth weight (g) | 3,536±649 | 3,320±417 |

| Male [%] | 11/21 [52] | 5/7 [71] |

| Cord pH | 7.00±0.20 | 6.74±0.15# |

| Cord base excess | −14.1±5.5 | −16.7±6.1 |

| Apgar 10 min | 5 [2–6] | 2.5 [1.3–3.8]* |

| Sarnat 3 at admission [%] | 4/21 [19] | 5/7 [71]# |

| Age start cooling | 4.9±0.9 | 5.6±0.4* |

*, P<0.05; #, P<0.01. Results are presented as mean ± SD.

Table 2. Clinical data at brain ultrasonography study.

| Clinical data | Survivors | Died |

|---|---|---|

| Age (h) | 17.1±10.5 | 19.5±6.4 |

| Esophageal temp (°C) | 33.6±0.3 | 33.3±0.1# |

| Heart rate (bpm) | 105±20 | 123±74* |

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg) | 62±12 | 66±13 |

| Mean blood pressure (mmHg) | 51±11 | 54±9 |

| Oxygen saturation | 99±4 | 98±2 |

| Inspired fraction on oxygen | 0.29±0.18 | 0.52±0.02* |

*, P<0.05; #, P<0.01. Results are presented as mean ± SD.

CPI with dynamic CDS of the basal ganglia was obtained in all 28 infants. A significantly higher CPI of the basal ganglia area was observed in non-survivors (0.226±0.221 cm/sec) when compared with infants that survived (0.107±0.085 cm/sec; P=0.02).

Discussion

In this study, we used a simple bedside technique of brain imaging with HUS and tissue perfusion assessment. We demonstrated with dynamic CDS a significantly increased perfusion of the basal ganglia in non-survivor infants with HIE receiving therapeutic hypothermia when compared to survivors. These increased perfusion values likely reflect a more remarkable reperfusion phase that follows a severe insult injury despite hypothermia treatment. Therefore this technique has the potential to be used as a biomarker of disease severity and/or response to treatment in this population.

In HIE, there is usually a cerebral hypoperfusion phase that may be followed by an increase in cerebral blood flow within the first few hours of life and may last days. This period is known as reperfusion phase and may lead to secondary brain injury. Assessment of basal ganglia injury is vital to determine severity of disease and prognosis. To the best of our knowledge, our study is the first to demonstrate specifically reperfusion injury of the basal ganglia with dynamic CDS. CDS provides real time bedside assessment of brain perfusion in critically ill neonates. Increased perfusion of basal ganglia is quite obvious with color Doppler, however this is a subjective assessment and for accurate measurements dedicated software is necessary. Dynamic tissue perfusion measurement provides blood flow data and perfusion velocity in a chosen ROI from a standard color Doppler video that are exported to a workstation after the exam is performed.

MRI provides anatomic and functional information demonstrating different patterns of injury. Watershed injury has been described in mild to moderate HIE whereas involvement of basal ganglia and thalami are findings observed in the more severe cases. Although HUS is thought to be less accurate than MRI, it is considered as a useful tool given its low cost, portability and lack of ionizing radiation. A recent study suggests that HUS may be a more effective modality in the assessment of HIE than it has been previously described (9). However, assessment of basal ganglia injury is vital to determine severity of disease and prognosis.

Although dynamic CDS evaluation of CPI appears to be promising in neonates with HIE, our study has some limitations. It was retrospective and the sample size is limited. We did not compare the CPI measurements to MRI results. Future prospective studies with a larger cohort and comparison to MRI are needed to evaluate and determine the accuracy and reproducibility of this technique. CPI quantification with dynamic CDS opens a window to better understand, diagnose and monitor reperfusion injury in HII.

Acknowledgements

None.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- 1.Cassia GS, Faingold R, Bernard C, Sant'Anna GM. Neonatal hypoxic-ischemic injury: sonography and dynamic color Doppler sonography perfusion of the brain and abdomen with pathologic correlation. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2012;199:W743-52. 10.2214/AJR.11.8072 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bryce J, Boschi-Pinto C, Shibuya K, Black RE, WHO Child Health Epidemiology Reference Group . WHO estimates of the causes of death in children. Lancet 2005;365:1147-52. 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)71877-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shankaran S, Laptook AR, Ehrenkranz RA, Tyson JE, McDonald SA, Donovan EF, Fanaroff AA, Poole WK, Wright LL, Higgins RD, Finer NN, Carlo WA, Duara S, Oh W, Cotten CM, Stevenson DK, Stoll BJ, Lemons JA, Guillet R, Jobe AH, National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Neonatal Research Network . Whole-body hypothermia for neonates with hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy. N Engl J Med 2005;353:1574-84. 10.1056/NEJMcps050929 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ilves P, Lintrop M, Talvik I, Muug K, Maipuu L. Changes in cerebral and visceral blood flow velocities in asphyxiated term neonates with hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy. J Ultrasound Med 2009;28:1471-80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Berger R, Garnier Y. Pathophysiology of perinatal brain damage. Brain Res Brain Res Rev 1999;30:107-34. 10.1016/S0165-0173(99)00009-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rutherford MA, Azzopardi D, Whitelaw A, Cowan F, Renowden S, Edwards AD, Thoresen M. Mild hypothermia and the distribution of cerebral lesions in neonates with hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy. Pediatrics 2005;116:1001-6. 10.1542/peds.2005-0328 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Miller SP, Ramaswamy V, Michelson D, Barkovich AJ, Holshouser B, Wycliffe N, Glidden DV, Deming D, Partridge JC, Wu YW, Ashwal S, Ferriero DM. Patterns of brain injury in term neonatal encephalopathy. J Pediatr 2005;146:453-60. 10.1016/j.jpeds.2004.12.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Barkovich AJ, Kjos BO, Jackson DE, Jr, Norman D. Normal maturation of the neonatal and infant brain: MR imaging at 1.5 T. Radiology 1988;166:173-80. 10.1148/radiology.166.1.3336675 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Epelman M, Daneman A, Kellenberger CJ, Aziz A, Konen O, Moineddin R, Whyte H, Blaser S. Neonatal encephalopathy: a prospective comparison of head US and MRI. Pediatr Radiol 2010;40:1640-50. 10.1007/s00247-010-1634-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Scholbach T, Herrero I, Scholbach J. Dynamic color Doppler sonography of intestinal wall in patients with Crohn disease compared with healthy subjects. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2004;39:524-8. 10.1097/00005176-200411000-00014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]