Abstract

Increased neuropeptide Y (NPY) gene expression in the dorsomedial hypothalamus (DMH) has been shown to cause hyperphagia, but the pathway underlying this effect remains less clear. Hypothalamic neural systems play a key role in the control of food intake, in part, by modulating the effects of meal-related signals, such as cholecystokinin (CCK). An increase in DMH NPY gene expression decreases CCK-induced satiety. Since activation of catecholaminergic neurons within the nucleus of solitary tract (NTS) contributes to the feeding effects of CCK, we hypothesized that DMH NPY modulates NTS neural catecholaminergic signaling to affect food intake. We used an adeno-associated virus system to manipulate DMH NPY gene expression in rats to examine this pathway. Viral-mediated hrGFP anterograde tracing revealed that DMH NPY neurons project to the NTS; the projections were in close proximity to catecholaminergic neurons, and some contained NPY. Viral-mediated DMH NPY overexpression resulted in an increase in NPY content in the NTS, a decrease in NTS tyrosine hydroxylase (TH) expression, and reduced exogenous CCK-induced satiety. Knockdown of DMH NPY produced the opposite effects. Direct NPY administration into the fourth ventricle of intact rats limited CCK-induced satiety and overall TH phosphorylation. Taken together, these results demonstrate that DMH NPY descending signals affect CCK-induced satiety, at least in part, via modulation of NTS catecholaminergic neuronal signaling.

Keywords: cholecystokinin, dorsomedial hypothalamus, neuropeptide Y, nucleus of solitary tract, tyrosine hydroxylase

the obesity epidemic in western countries has generated more interest in understanding the pathways and mechanisms controlling energy homeostasis. Central and peripheral signals are involved in regulating appetite. Previous studies have established that central neural systems regulate food intake, in part, by modulating the effects of peripheral meal-related signals, such as cholecystokinin (CCK) (30). The nucleus tractus solitarius (NTS) in the brain stem has notably been characterized as a site of integration of central and peripheral signals (22).

Central leptin signaling enhances CCK satiating effect (12, 20). Neuropeptide Y (NPY) produces an opposite effect. Injection of NPY in the fourth ventricle increases food intake in a dose-dependent fashion and reduces the latency to eat (10). Third ventricle NPY administration limits CCK-induced c-Fos expression in the NTS and CCK-induced satiety (30, 32) as well as NTS neuronal activation in response to a gastric load (37). Leptin and NPY actions in energy homeostasis have mostly been studied in the arcuate nucleus (ARC) but less in other hypothalamic nuclei, such as the dorsomedial hypothalamus (DMH). The first evidence for a role of the DMH in regulating food intake came from lesioning studies. Rodents with lesions of the DMH are hypophagic and lose weight (2). Several studies have shown the importance of the DMH in the regulation of food intake and development of obesity. Otsuka Long-Evans Tokushima Fatty (OLETF) rats, an animal model of obesity, display an increase in DMH NPY gene expression before the onset of obesity (4). DMH NPY gene expression in rodents has been linked to hyperphagia (43). DMH NPY levels are notably elevated during early postnatal development (18) and lactation (25), when hyperphagia is present. A raise in DMH NPY gene expression causes an increase in meal size (43) and has been shown to reduce CCK-induced satiety (43). However, our understanding of the pathways by which DMH NPY modulates the behavioral efficacy of feeding-related sensory feedback, such as CCK, is limited.

CCK is released in response to a meal and activates vagal afferent neurons to promote meal termination. Vagal afferent neurons terminate in the NTS where activation of catecholaminergic neurons has been shown to be critical for CCK action (35). Exogenous CCK injections induce c-Fos immunoreactivity in tyrosine hydroxylase (TH)-expressing neurons within the NTS (27). TH is the rate-limiting enzyme in catecholamine biosynthesis, and changes in TH activity have been shown to regulate catecholamine synthesis (26). TH activity is regulated by phosphorylation. Phosphorylation at Ser31 and Ser40 have been shown to increase enzymatic activity and neurotransmitter release (26). TH phosphorylation has been directly related to catecholamine neuronal activity. For instance, in rats, cocaine infusion led to TH phosphorylation of ventral tegmental area (VTA) neurons associated with dopamine release, and pharmacological inhibition of TH phosphorylation resulted in a decrease in extracellular dopamine (45). Additionally, hypotension and glucoprivation led to TH phosphorylation, increase in TH activity, and c-Fos expression in several catecholaminergic brain areas in rats, including the brain stem, leading Damanhuri et al. (11) to conclude that serine phosphorylation of TH was a highly sensitive measure of neuronal activity. Exogenous CCK injections trigger TH phosphorylation in the NTS, and specific lesions to TH neurons blunt CCK-induced satiety (1, 36). Moreover, the ability of CCK to decrease food intake is correlated with the number of viable NTS TH neurons (35). Exogenous CCK injections trigger ERK activation in NTS TH neurons and TH phosphorylation (1). CCK-induced TH phosphorylation is ERK-dependent (1), and ERK activation has been shown to mediate CCK-induced satiety (39). Taken together, these data indicate an important role for TH phosphorylation in mediating CCK action. Because the NTS dendrites that contain NPY receptor 1 (Y1R) also express TH (17), we hypothesized that DMH NPY neurons project to the NTS and can affect CCK-induced satiety via modulation of NTS catecholaminergic neuronal signaling.

We used an adeno-associated virus (AAV) system to manipulate DMH NPY gene expression in rats to examine this pathway. AAV-mediated overexpression of DMH NPY resulted in a decrease in NTS TH expression and reduced exogenous CCK-induced satiety. Knockdown of DMH NPY produced the opposite effects. AAV-mediated hrGFP anterograde tracing revealed that DMH NPY neurons project to the NTS; the projections were in close proximity to catecholamine neurons, and some contained NPY. When administered directly into the fourth ventricle of intact rats, NPY limited CCK-induced satiety and overall TH neuronal activation. Together, these results demonstrate that DMH NPY descending signals affect CCK-induced satiety, at least in part, via modulation of NTS catecholaminergic neuronal signaling.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals and Experimental Design

Male Sprague-Dawley rats (307 ± 9 g; Charles River Laboratories International) were single-housed in hanging wire-mesh cages and maintained on a 12:12-h light-dark cycle in a temperature-controlled room. They had ad libitum access to tap water and standard laboratory rodent chow (15.8% fat, 65.6% carbohydrate, and 18.6% protein in %kcal; 3.37 kcal/g; Prolab RMH 1000, PMI Nutrition International).

For experiment 1, we used the recombinant AAV vector either to overexpress or to knock down NPY gene expression specifically in the DMH (n = 6–8/group). Feeding response to exogenous CCK was examined in these animals. DMH NPY (via in situ hybridization) and NTS TH gene expression (via RT-PCR) were quantified in the same rats (n = 4–6/group). Another group of AAV-injected animals (AAVGFP) were used to examine DMH NPY projections via AAV-mediated hrGFP expression in combination with NPY and TH immunohistochemistry in the NTS (n = 3).

For experiment 2, TH neuron activation in response to CCK (n = 6) or saline (n = 3) was performed in an additional group of naïve animals.

For experiment 3, twelve rats were successfully equipped with fourth ventricle cannula. Ten of these animals were used to determine food consumption in response to CCK following intracerebroventricular (icv) NPY through the fourth ventricle. At death, animals were split into two groups and received fourth ventricle injection of either saline (n = 6) or NPY (n = 6). Subgroups were treated with intraperitoneal saline (n = 3) or CCK (n = 3). All procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the Johns Hopkins University.

Experiment 1

AAV-mediated vector.

Recombinant viral vectors AAVNPY (AAV-mediated NPY gene expression), AAVGFP (control), AAVshNPY (AAV-mediated shRNA for NPY knockdown), and AAVshCTL (control) were prepared using the AAV Helper-Free System (Stratagene) as described in Refs. 43 and 9. Virus titers were determined using quantitative PCR, and ∼1 × 109 particles/site were used for each virus injection. Animals were randomly assigned to bilateral DMH injections with coordinates: 3.1 mm caudal to bregma, 0.4 mm lateral to midline, and 8.6 mm ventral to skull surface (34) at a rate of 0.1 μl/min for 5 min, and the injector remained in place for an additional 5 min before removal (n = 6–8/group). At the end of experiments, after euthanasia, coronal sections (12 μm) through the hypothalamus were prepared, and the sections containing hrGFP expression were examined on a Zeiss Axio Imager (Carl Zeiss MicroImaging). Levels of NPY mRNA expression in areas of the DMH and the ARC [3.0–3.5 mm posterior to bregma (34)] were examined using in situ hybridization with 35S-labeled antisense riboprobes of NPY as previously described to confirm overexpression or knockdown of DMH NPY (9, 43).

Measure of CCK-induced satiety.

Animals were habituated for at least 4 consecutive days to intraperitoneal injection and to a feeding schedule in which food was removed from the cages 2 h before dark onset and returned to the cages just before lights off.

On the experimental day, animals were fasted 2 h before dark onset and randomly divided into two groups. One group received a CCK injection (CCK-8S; 3.2 nmol/kg ip; Bachem); the other group received a saline injection. Food was returned to the cages, and food intake was measured 30 min later.

Two days later, animals received a second injection with either saline or CCK (3.2 nmol/kg ip) in a counterbalanced order. Food intake was measured 30 min after injection. Each animal served as its own control.

TH expression.

Brain stems were sliced via cryosection (CM1900; Leica Biosystems) until apparition of the central canal [Plate 76–78 of the Paxinos and Watson Rat Brain Atlas (34)] and individual NTS were collected; two 0.5-mm sections were cut, and the NTS was punched out using an 18-gauge needle. Total RNA was extracted using TRIzol reagent (Life Technologies). Two-step quantitative real-time RT-PCR was performed for gene expression determination. One microgram of total RNA was reverse-transcribed into first-strand cDNA using the RevertAid First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Fermentas), and the resulting cDNA product was then quantified using iQ SYBR Green SuperMix Kit (Bio-Rad Laboratories) on iQ5 Multicolor Real-Time PCR Detection System (Bio-Rad Laboratories). Primers were obtained from Integrated DNA Technologies. β-Actin was used as an internal control.

NTS immunohistochemistry.

Cryostat sections (12 μm) of brain stems from AAVGFP animals (n = 6) were immunostained for TH or TH in combination with NPY. Nonspecific background was blocked by a 30-min incubation at 37°C with 20% goat serum. Slices were incubated with primary antibodies (mouse anti-TH at 1:500, cat. no. LS-C85507, LifeSpan BioSciences, or rabbit anti-NPY at 1:200, DiaSorin) for 2.5 h at 37°C, washed three times in PBS, and incubated with secondary antibody (Alexa Fluor goat anti-mouse 546 or 350 or goat anti-rabbit 546 at 1:200; Life Sciences). Sections were examined on a Zeiss Axio Imager.

Experiment 2

TH neuron activation in response to CCK.

Animals were fasted for 2 h before an injection of either CCK (3.2 nmol/kg ip; n = 3) or saline (intraperitoneal; n = 3). Fifteen minutes after injection, animals were deeply anesthetized via isoflurane inhalation (Baxter) and transcardially perfused with cold saline, followed by 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA). Brain stems were removed and postfixed for 2 h in 4% PFA before being stored in 25% sucrose.

Cryostat sections (12 μm) of brain stems were used for immunohistochemistry. Nonspecific background was blocked by a 30-min incubation at 37°C with 20% goat serum. Slices were incubated with primary antibodies (mouse anti-TH at 1:500, cat. no. LS-C85507, LifeSpan BioSciences, or rabbit anti-phosphorylated TH (p-TH) at 1:200, cat. no. 3370S, Cell Signaling Technology) for 2.5 h at 37°C, washed three times in PBS, and incubated with secondary antibody (Alexa Fluor goat anti-mouse 488 or goat anti-rabbit 546 at 1:200, Life Sciences). Sections were examined on a Zeiss Axio Imager. Total number of TH neurons and p-TH-positive neurons were manually counted in photographs of unilateral NTS sections.

Experiment 3

Fourth ventricle cannulation and fourth ventricle NPY administration.

Animals were anesthetized with a ketamine-xylazine mixture. They were placed in a stereotaxic apparatus and implanted with chronic indwelling stainless steel cannula aimed at the fourth cerebral ventricle (coordinates: 2 mm anterior to the extremity of the occipital bone, 7.2 mm ventral to the dural surface). Rats were permitted to recover from cannula implantation for 1 wk after surgery. Animals were then habituated for at least 4 consecutive days to fourth ventricle injection and a feeding schedule in which food was removed from the cages 4 h before dark onset and returned to the cages 2 h into the dark cycle. Accurate cannula placement was verified during brain stem sectioning after animals were killed.

On experimental days, animals were fasted for 4 h and then received a fourth ventricle injection of either saline or NPY (5 nmol). Two hours following intracerebroventricular injection, animals received another injection of either CCK (3.2 nmol/kg ip) or saline (intraperitoneal). Food was returned to the cages, and food intake was measured 30 min later. Each animal received the four treatment combinations (saline/saline, saline/CCK, NPY/saline, and NPY/CCK) with at least 2 days in between experimental days.

TH and p-TH protein levels.

Animals received the same treatment as described above. Fifteen minutes after the second injection (CCK or saline intraperitoneally), animals were anesthetized by isoflurane inhalation (Baxter) and killed by decapitation. Brains were removed, frozen in dry ice, and preserved at −80°C.

NTS nuclei were punched from animals’ brain stems using a cryostat. Brain stems were sectioned until apparition of the central canal [Plate 76–78 of the Paxinos and Watson Rat Brain Atlas (34)]. Two 0.5-mm sections were cut, and the NTS was punched out using an 18-gauge needle. Ten micrograms of protein were used, samples were loaded in precast 4–12% Tris-acetate gels, and the gels were run for 50 min at 200 V. The proteins were transferred (1 h at 100 V) from the gels to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes. Skim milk (10%) in TBS-Tween 20 (m-TBST) was used to block nonspecific binding. Membranes were incubated with primary antibodies diluted in 10 ml of 10% m-TBST (β-actin, 2 μl, Sigma cat. no. 2228; TH, 10 μl, Millipore cat. no. ab152; p-TH, 10 μl, Millipore cat. no. ab5423). Secondary antibodies (10 μl) were also diluted in 10 ml of 10% m-TBST (anti-rabbit IgG, horseradish peroxidase-linked, Cell Signaling Technology cat. no. 7074). The membranes were exposed to film for 3 min, and the films were analyzed using Image Studio Lite 5.2 (LI-COR Biosciences).

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using Prism software (Prism 6.0; GraphPad Software). Unpaired two-tailed t-test was used when comparing two groups. To analyze data and differences among group means for three or more groups, one-way ANOVA (Tukey method) was used. When two treatments were analyzed, two-way ANOVA was used (Tukey post hoc). Differences were considered significant if P < 0.05. Data are means ± SE. Statistical details are provided in the figure legends.

RESULTS

Experiment 1

Manipulation of DMH NPY gene expression in rats.

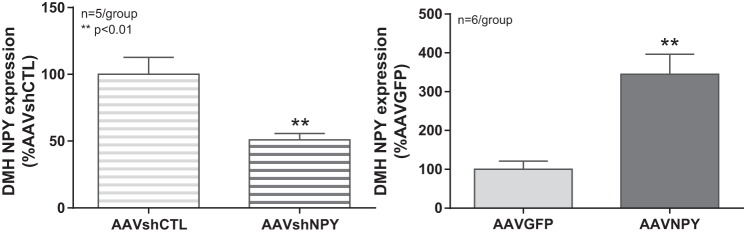

DMH NPY gene expression was determined by in situ hybridization. Injection of AAV-mediated RNA interference (RNAi) vector (AAVshNPY) led to a significant 51% knockdown of DMH NPY gene expression when compared with control AAVshCTL. Conversely, injection of recombinant viral vector AAVNPY resulted in a significant 3.4-fold overexpression of NPY in the DMH when compared with control AAVGFP (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

DMH injections of viral vectors modulate DMH NPY expression. DMH NPY gene expression was determined via in situ hybridization and normalized to AAVshCTL or AAVGFP expression levels (set at 100). Injection of AAV-mediated RNAi vector (AAV-mediated NPY knockdown or AAVshNPY) into the DMH resulted in a significant 51% decrease in DMH NPY expression compared with control AAVshCTL (100 ± 12 vs. 50.9 ± 4.8, P < 0.01). Injection of recombinant viral vector AAVNPY (AAV-mediated NPY expression) led to a significant 3.4-fold increase in DMH NPY expression compared with AAVGFP (100 ± 21.2 vs. 344.7 ± 51.8, P < 0.01).

Changes in DMH NPY gene expression affect CCK-induced satiety.

We characterized the feeding response to exogenous CCK-8S (3.2 nmol/kg) in animals injected with AAV vector either to overexpress or to knockdown DMH NPY. In the control groups, AAVshCTL for NPY knockdown and AAVGFP for NPY overexpression, animals significantly reduced their 30-min food intake in response to CCK compared with saline. Changes in NPY gene expression in the DMH did not significantly alter baseline (saline) intake, and there was no difference in CCK response between the two control groups. Knockdown of DMH NPY resulted in an increase in CCK-induced satiety. AAVshNPY animals reduced their food intake in response to intraperitoneal CCK significantly more than the AAVshGFP rats. Conversely, overexpression of NPY in the DMH blunted the animals’ response to exogenous CCK. AAVNPY rats’ intake following CCK treatment was significantly greater than AAFGFP animals’ intake and did not differ from baseline intake (Fig. 2). It should be noted that although manipulations of NPY expression in the DMH did not affect 30-min intake (saline treatment) as compared with their own controls (AAVshCTL 4 ± 0.3 g vs. AAVshNPY 4.2 ± 0.4 g, not significant, and AAVGFP 2.1 ± 0.5 g vs. AAVNPY 1.4 ± 0.4 g, not significant), the baseline intakes between the two cohorts appear to differ. The reason for this difference is unclear. Since we did not record food intake before experimental manipulations, we do not know whether experimental manipulations could cause this difference.

Fig. 2.

Changes in DMH NPY expression affect CCK-induced satiety. Thirty-minute food consumption (in grams) in response to an intraperitoneal CCK injection (3.2 nmol/kg) compared with a saline injection. Changes in NPY expression in the DMH did not significantly alter baseline (saline) intake [AAVshCTL 4 ± 0.3 g vs. AAVshNPY 4.2 ± 0.4 g, not significant (ns); AAVGFP 2.1 ± 0.5 g vs. AAVNPY 1.4 ± 0.4 g, ns]. There was no difference in the response to CCK between the 2 control groups (AAVshCTL vs. AAVGFP, P = 0.7, ns). CCK significantly reduced food intake in both groups. Knockdown of DMH NPY enhanced CCK-induced satiety (AAVshCTL −1.1 ± 0.3 g vs. AAVshNPY −2.4 ± 0.7 g, P < 0.05), whereas overexpression of NPY in the DMH blunted the response to exogenous CCK (AAVGFP −1.3 ± 0.7 g vs. AAVNPY +0.1 ± 0.3 g, P < 0.05).

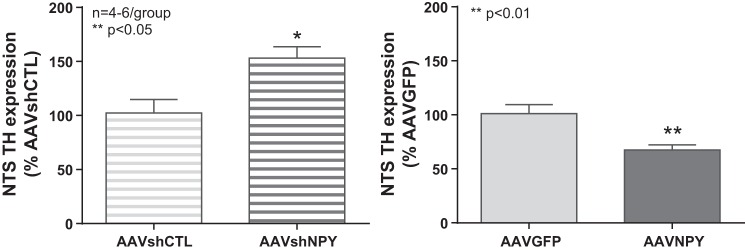

Changes in DMH NPY gene expression affect TH expression in the NTS.

We used AAVshNPY and AAVNPY animals to test whether changes in DMH NPY gene expression will affect TH gene expression in the NTS. We found that knockdown of DMH NPY resulted in a significant increase in TH expression in the NTS. AAVshNPY animals had significantly higher levels of TH expression in the NTS than AAVshGFP rats. Conversely, overexpression of NPY in the DMH led to a significant decrease in TH expression in the NTS (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Changes in DMH NPY expression affect NTS TH expression. Knocking down DMH NPY resulted in a significant 52% increase in TH expression in the NTS (AAVshCTL vs. AAVshNPY, P < 0.05). Conversely, overexpression of NPY in the DMH led to a significant 33% decrease in TH expression in the NTS (AAVGFP vs. AAVNPY, P < 0.01).

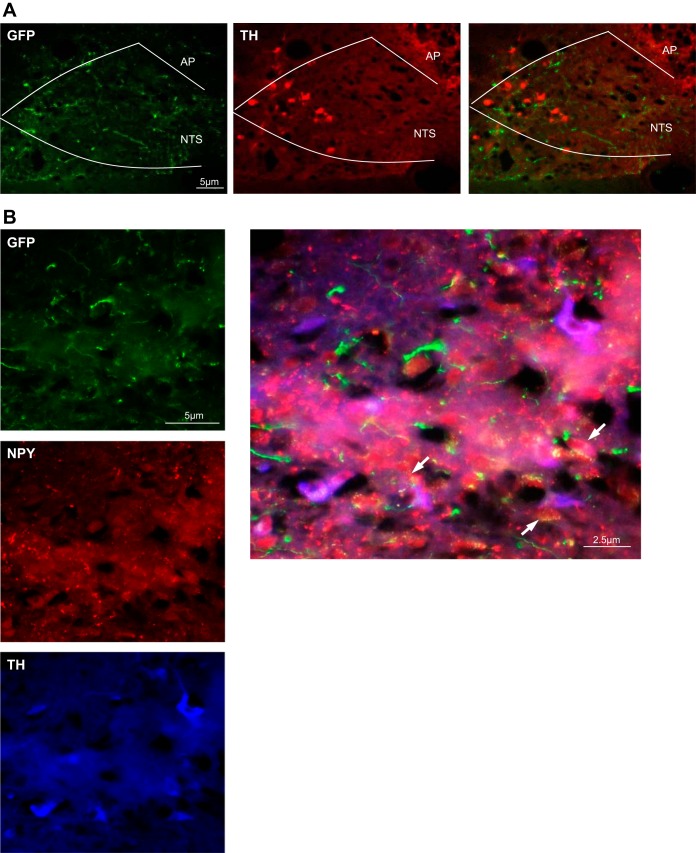

DMH neurons project to TH neurons in the NTS.

Projections from DMH neurons were examined via viral-mediated hrGFP anterograde tracing in AAVGFP animals. Positive hrGFP fibers were found in the brain stem, in particular, in the NTS. We first immunolabeled TH-positive neurons and determined that projections arising from the DMH were terminating in close proximity to catecholaminergic NTS neurons (Fig. 4A). We then stained the NTS for TH-positive neurons and NPY-positive fibers. We found that there were projections from the DMH as hrGFP-positive fibers contained NPY, and they were in proximity to catecholaminergic neurons in the NTS (Fig. 4B).

Fig. 4.

A: DMH neurons project to NTS, in close proximity to TH neurons. Projections from the DMH were followed via viral-mediated hrGFP expression (green) in AAVGFP-injected animals (n = 6). TH-positive neurons were labeled in red. There were projections from the DMH to the NTS, in close proximity to TH neurons (AP, area postrema). B: DMH projections to the NTS contain NPY. Projections from the DMH were followed via viral-mediated hrGFP expression (green) in AAVGFP-injected rats (n = 6). NPY was stained in red, and TH-positive neurons were labeled in blue. Some projections from the DMH to the NTS contained NPY (shown in yellow) and could be found in close proximity to TH neurons (white arrows).

Experiment 2

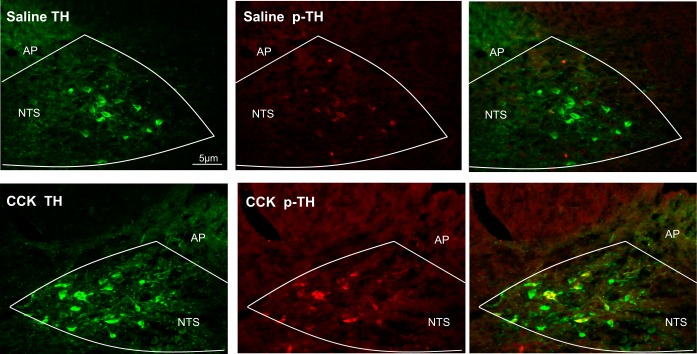

Exogenous CCK activates TH neurons in the NTS.

We used immunohistochemistry to label TH-positive neurons as well as p-TH in the NTS of rats receiving intraperitoneal injection of saline or CCK. TH-positive neurons were identified in the NTS following both treatments. Saline injection did not induce TH phosphorylation, whereas exogenous CCK led to TH phosphorylation in ~50% of TH-positive neurons (Fig. 5). Exact enumeration of TH and p-TH-positive neurons can be found in Table 1.

Fig. 5.

TH neuron activation in the NTS in response to exogenous CCK. Immunolocalization of TH-positive neurons (green) and p-TH-positive neurons (red) following intraperitoneal injection of saline or CCK (3.2 nmol/kg; n = 6/group) in the NTS. Saline injection did not induce TH phosphorylation in TH-positive neurons, whereas exogenous CCK led to TH phosphorylation in ~50% of TH-positive neurons.

Table 1.

Quantification of TH neuron activation following CCK treatment

| TH-Positive Neurons | p-TH-Positive Neurons | |

|---|---|---|

| NTS (unilateral) | 9.6 ± 2.5 | 4.4 ± 1.1 |

| 48.2 ± 11.5% |

Enumeration of TH-positive neurons and p-TH-positive neurons in the NTS (unilateral) at the AP level (n = 6; 4–6 images/animal). Exogenous CCK injection led to TH phosphorylation in 48% of TH-positive neurons.

Experiment 3

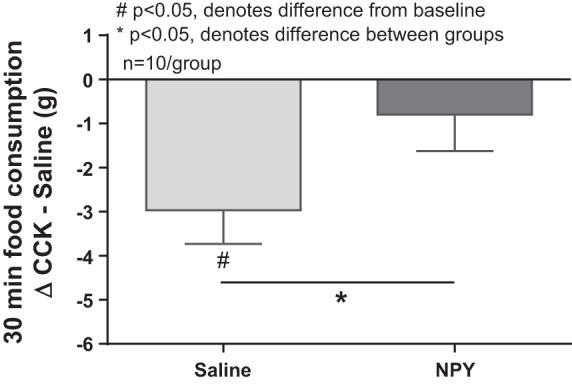

Preadministration of intracerebroventricular NPY blunts CCK-induced satiety.

To examine NPY and CCK interaction further, animals received a fourth ventricle intracerebroventricular injection of either saline or NPY (5 nmol) 2 h before an intraperitoneal injection of either saline or CCK (3.2 nmol/kg). Fourth ventricle NPY administration at this dose did not significantly increase food intake, and there was no difference in food intake between the saline/saline and NPY/saline groups. CCK significantly reduced food intake at 30 min when combined with an intracerebroventricular saline injection. However, preadministration of NPY blunted CCK-induced satiety, and animals’ consumption following CCK treatment was not reduced compared with baseline and was significantly increased compared with the control group (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

Fourth ventricle intracerebroventricular (icv) preadministration of NPY blunts exogenous CCK-induced satiety. Thirty-minute food consumption (in grams) in response to an intraperitoneal CCK injection (3.2 nmol/kg) compared with a saline injection in rats that 2 h prior had received icv administration of either saline or NPY (5 nmol). There was no significant difference in baseline intake following icv administration of saline or NPY (5.3 ± 2.4 vs. 6.3 ± 2.9 g, P = 0.4, ns). Exogenous CCK significantly reduced 30-min food intake when combined with an icv saline injection (saline/saline 5.1 ± 0.7 g vs. saline/CCK 2.3 ± 0.7 g, P < 0.05). icv NPY administration 2 h before CCK injection blunted CCK-induced satiety. Intake following CCK injection was not different from baseline and was significantly greater than in the control group (saline −3.0 ± 0.8 g vs. NPY −0.8 ± 0.8 g, P < 0.05).

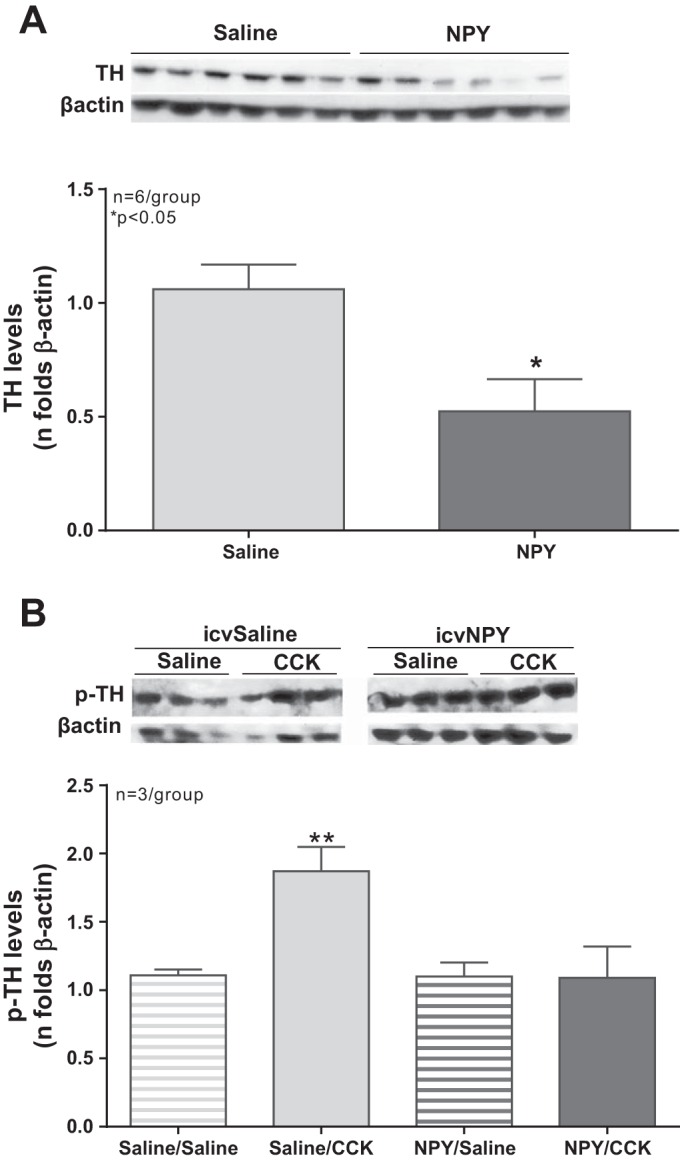

Fourth ventricle administration of NPY leads to a decrease in TH protein levels in the NTS and a reduction in phosphorylated TH in response to CCK.

We characterized TH protein and phosphorylated TH protein levels in the NTS of animals that had received a fourth ventricle intracerebroventricular injection of either saline or NPY (5 nmol) 2 h before an intraperitoneal injection of either saline or CCK (3.2 nmol/kg). CCK injection had no significant effect on total TH levels, and there was no significant effect of intracerebroventricular or intraperitoneal treatments on total TH levels. However, administration of NPY into the fourth ventricle significantly reduced TH protein levels in the NTS (NPY vs. saline, P < 0.01; Fig. 7A).

Fig. 7.

A: 4th ventricle administration of NPY decreases TH NTS protein levels. TH protein levels in the NTS of animals that had received a 4th ventricle injection of saline or NPY (5 nmol) before an intraperitoneal injection of saline or CCK (3.2 nmol/kg). There was no significant effect of the intraperitoneal treatment and no effect of 4th ventricle injection and intraperitoneal injection on total TH protein levels in the NTS. However, there was a significant effect of 4th ventricle treatment; administration of NPY led to a significant decrease in TH protein levels in the NTS (P < 0.05). B: 4th ventricle administration of NPY decreases p-TH NTS protein levels in response to exogenous CCK. TH protein levels in the NTS of animals that had received a 4th ventricle injection of saline or NPY (5 nmol) before an intraperitoneal injection of saline or CCK (3.2 nmol/kg). Because NPY treatment reduced the amount of total TH, p-TH was quantified in comparison to β-actin. CCK injection led to a significant increase in TH phosphorylation levels in the NTS in saline-pretreated animals (P < 0.01). Preadministration of NPY blunted the effects of CCK-induced TH phosphorylation (saline/CCK vs. NPY/CCK, P < 0.01).

Because we have found that NPY treatment reduced the amount of total TH, p-TH was quantified in comparison to β-actin rather than total TH. There was no interaction between the intraperitoneal and intracerebroventricular treatment. There was a significant increase in TH phosphorylation in response to intraperitoneal CCK (P < 0.01). CCK-induced TH phosphorylation was blunted by preadministration of fourth ventricle NPY (saline/CCK vs. NPY/CCK, P < 0.01). TH phosphorylation levels in the NPY/CCK group were not different from the control saline/saline group or the NPY/saline group (Fig. 7B). There was no difference between the saline/CCK and NPY/CCK groups in the p-TH-to-total TH ratio. NPY seemed to act predominantly via reduction of NTS TH protein levels and not by affecting the TH phosphorylation pathway.

DISCUSSION

The present study aimed to deepen our understanding of the interplay between the hypothalamus and hindbrain in the control of food intake. We have focused on DMH NPY signaling, which has previously been shown to play a critical role in the development of hyperphagia in the OLETF rat model, notably via an increase in meal size (4, 43), which is traditionally thought of as being regulated by gut-originating inhibitory sensory feedback (14). In this study, we determined a pathway by which DMH NPY interacts with gut signals to regulate food intake. We found that DMH NPY gene expression affected catecholaminergic signaling in the NTS to modulate the action of the satiety peptide CCK. Viral-mediated changes in DMH NPY gene expression modulated the ability of CCK to reduce food intake; overexpression of DMH NPY blunted exogenous CCK action, whereas knockdown of DMH NPY had the opposite effect. Additionally, we revealed that changes in DMH NPY gene expression were negatively correlated with changes in NTS TH expression. DMH NPY overexpression resulted in a decrease in NTS TH expression, whereas knockdown of DMH NPY again produced the opposite effect. We questioned whether DMH neurons directly project to the NTS to regulate NTS TH expression. Using viral-mediated hrGFP anterograde tracing in combination with immunohistochemistry, we found projections arising from the DMH in the NTS. Importantly, some of these projections were also positively labeled for NPY. As we had previously found that manipulation of DMH NPY gene expression causes changes in NTS NPY levels but not in NTS NPY gene expression (43), we concluded that NPY-containing fibers project from the DMH to the NTS and that changes in DMH NPY gene expression lead to changes in NTS NPY contents. NPY-containing fibers arising from the DMH were found in close proximity to TH neurons. This is critical, as CCK has been shown to signal via activation of TH neurons in the NTS (1, 36).

Using immunohistochemistry, we first confirmed that exogenous administration of CCK led to TH phosphorylation in the NTS (1). We found CCK-induced TH phosphorylation in ~50% of the NTS TH-positive neurons. To test whether changes in NTS NPY levels could influence CCK-induced satiety and catecholaminergic signaling, we administered NPY directly into the fourth ventricle of intact rats. NPY treatment blunted CCK-induced satiety and overall TH neuronal activation by decreasing total TH protein levels. In this case, the ratio of phosphorylated to total TH protein was unchanged, suggesting an effect of NPY on total TH expression rather than on TH phosphorylation. We concluded from these data that central NPY descending signals affect CCK-induced satiety, at least in part, via modulation of NTS catecholaminergic neuronal signaling to regulate food intake (Fig. 8).

Fig. 8.

Proposed pathway linking changes in DMH NPY expression and CCK sensitivity. Based on the data presented in this paper, we propose the following model: an increase in DMH NPY expression leads to an increase in DMH NPY content. NPY fibers transport NPY to the NTS, leading to an increase in NTS NPY content. Within the NTS, NPY binds to the Y1R on TH neurons, triggering a decrease in TH expression and TH protein levels. Ultimately, the pool of TH enzyme available for phosphorylation is reduced, resulting in a decrease in the quantity of phosphorylated TH in response to CCK and a decrease in CCK-induced satiety. Conversely, a decrease in DMH NPY expression will result in an increase in NTS TH expression and NTS TH protein levels, increasing the pool of TH enzyme available for phosphorylation, resulting in an increase in TH phosphorylated in response to CCK and an increase in CCK-induced satiety.

Our study supports a role for DMH NPY in modulating NTS TH gene expression and TH protein levels. TH is the rate-limiting enzyme in catecholamine biosynthesis, and changes in TH activity have been shown to regulate catecholamine synthesis (26, 33). CCK is believed to signal via activation of NTS TH neurons; in the present study, we found that an exogenous CCK injection (3.2 nmol/kg) induced TH phosphorylation in ~50% of the NTS TH-positive neurons. Previous studies on rats have reported that between 10 and 70% of NTS TH neurons are activated in response to CCK, with CCK doses varying between 2.75 nmol/kg and 100 µg/kg (∼9 nmol/kg; Refs. 27, 28, 36, 42). NTS TH neuronal activation increases with CCK dosage (28). Crucially, NTS catecholamine lesions significantly reduce CCK-induced satiety, and the ability of CCK to decrease food intake is strongly correlated to the number of surviving NTS TH neurons (35). Taken together, these data show that CCK acts, at least partially, via activation of NTS TH neurons to decrease intake. TH phosphorylation has been shown to be a marker of TH neurons activity (11). Exogenous CCK administration leads to an ERK-dependent TH phosphorylation (1), and ERK activation has been shown to mediate CCK-induced satiety (39). Our data confirmed CCK-induced TH phosphorylation and showed that a decrease in TH phosphorylation was associated with a reduction in CCK-induced satiety. Although these results suggest that CCK action is mediated via TH phosphorylation, we do not currently have direct evidence of the necessity of TH phosphorylation for CCK action. Several central signals have been shown to modulate CCK action, notably leptin, which can enhance CCK-induced satiety (12, 20). Leptin increases NTS TH neuronal activation in response to CCK, identifying NTS catecholaminergic neurons as potential mediators of the interaction between central and peripheral signaling (42).

TH phosphorylation has been shown to increase the enzyme activity and catecholamine release (26). TH activity can also be modulated on the long term via changes in TH protein level. The amount of TH protein synthetized has been shown to be regulated at the gene level, via mRNA production, but also by posttranscriptional processes, including alternative RNA processing, regulation of RNA stability, and translation regulation (23). TH mRNA levels have previously been shown to be modulated by corticoids, cold, stress, and drug administration (23). Additionally, TH mRNA levels have been linked to feeding status; administration of long-acting glucagon-like peptide 1 agonist exendin-4 (EX-4) leads to a decrease in food intake associated with reduction in hypothalamic NPY gene expression and increase in mesolimbic TH expression (44). Central leptin treatment also reduces intake and NPY hypothalamic expression; similarly, these changes were associated with an increase in TH expression in the forebrain (41). In both cases, changes in TH mRNA levels were observed 2 h posttreatment. Faster changes in TH protein levels have also been reported. Brain stem TH protein levels have been shown to be regulated by the ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS), and changes in TH protein levels have been observed within 30 min of treatment with a UPS inhibitor (26a). Additionally, in rats, treatment with EX-4 led to a significant increase in VTA TH protein within 15 min (31). Because of the timeline of our experiments, protein quantifications were measured 2 h and 15 min post-intracerebroventricular injection, and changes in TH protein levels in response to NPY were likely due to regulation in gene expression and mRNA production. This is also in accordance with data from our first experiment, where NTS TH expression was modulated by DMH NPY gene expression, however, we did not measure NTS TH gene expression in response to an increase in NTS NPY contents.

We had previously found that manipulation of DMH NPY gene expression resulted in changes in NTS NPY content but not NTS NPY gene expression (43). In this study, we found evidence of NPY-containing fibers derived from the DMH to the NTS, further supporting a direct connection from DMH NPY neurons to the NTS to modulate gut-originating sensory feedback. It should be noted that the AAVGFP virus can affect all neurons at the site of injections, and positive hrGFP fibers could potentially arise from other DMH neuronal populations that may project to the NTS to regulate CCK action. For instance, prolactin-releasing peptide (PrRP) neurons are notably present in the DMH, and genetic ablation of PrRP attenuates CCK-induced satiety (15). Additionally, DMH NPY may affect CCK signaling indirectly; DMH-originating projections have been found in the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus (PVN) and lateral hypothalamic area (LH). Double-labeling experiments revealed that DMH projections to the PVN and LH contain NPY (24), and PVN neurons project to the NTS to modulate CCK-induced satiety (6). Moreover, there are NPY-expressing cells in the LH (29) and in the PVN (19, 21) that might project to the NTS as well. Oxytocin-containing fibers from the PVN have also been shown to project to the NTS, and activation of these neurons enhance CCK-induced satiety (7). Interestingly, oxytocin receptor antagonist injection within the DMH has been found to modulate NTS TH neuronal activation in response to feeding (40). Thus, although our data support a direct connection from DMH NPY neurons to the NTS, we cannot rule out the possibility that other neuronal populations within the DMH may be involved in regulating NTS NPY content or the existence of an indirect pathway between DMH NPY neurons and the NTS.

We have shown that changes in DMH NPY gene expression result in changes in NTS NPY content (43). To test whether DMH NPY effects on CCK action may be modulated via alteration in NTS NPY content, we injected NPY directly into the fourth ventricle of naïve rats. We found that pretreatment with NPY significantly blunted the ability of CCK to reduce food intake. As DMH NPY projections were found in close proximity to NTS TH neurons and changes in DMH NPY gene expression resulted in changes in NTS TH expression, we investigated a potential role for NTS NPY in regulating TH activity. TH activity can be regulated via phosphorylation and/or changes in TH protein levels (23). We quantified TH and p-TH protein levels following an intracerebroventricular injection of either NPY or saline 2 h before an intraperitoneal injection of either CCK or saline; we found that NPY treatment reduced the amount of total TH protein levels. CCK injection led to an increase in p-TH protein when combined with saline intracerebroventricular administration, but this effect was blunted by NPY pretreatment. Interestingly, there was no difference in p-TH-to-total TH ratio between the saline/CCK and NPY/CCK groups. We concluded that NPY reduces TH phosphorylation in response to CCK by decreasing TH protein levels and, consequently, the amount of enzyme available for phosphorylation. NPY did not affect TH phosphorylation. Similarly, leptin has previously been shown to enhance CCK action in vagal afferent neurons by increasing the cytoplasmic pool of a transcription factor, early growth response protein 1 (EGR-1), but did not affect the actual activation step, EGR-1 translocation (13).

Our data support a direct connection between the DMH and the NTS and a role for NPY in transmitting information from the hypothalamus to the hindbrain. Other peptides may also be involved in transmitting signals from DMH NPY neurons to the NTS to regulate CCK function. Injection of a cAMP agonist (Sp-cAMP) in the hypothalamus has notably been shown to inhibit NPY-induced feeding, and Sp-cAMP administration specifically increases the active protein kinase A (PKA) activity in the DMH (38), suggesting that NPY in the DMH could signal via inhibition of cAMP level and PKA activity to promote food intake. This is particularly interesting as TH has been shown to be phosphorylated by cAMP-dependent PKA (16). This possibility merits further investigation.

Overall, we found that changes in DMH NPY gene expression modulate CCK-induced satiety. Physiologically, DMH NPY gene expression has been shown to be upregulated by food restriction (5, 19) or during periods of hyperphagia, such as early postnatal development and lactation (24). Our data suggest that when energy stores are depleted or extra energy is required, elevation in DMH NPY gene expression can lead to an increase in meal size and food intake via a decreased sensitivity for gut-originating feedback signals. Inversely, when energy storage increases, leptin has been shown to restrict food intake by enhancing CCK-induced satiety (13).

Additionally, changes in DMH NPY gene expression may be crucial in the etiology of obesity. In rats, CCK sensitivity has been reported to decrease after 5-6 wk of high-fat diet exposure, and loss in CCK sensitivity is concurrent with the development of hyperphagia and rapid weight gain (12). OLETF rats display an increase in DMH NPY gene expression before the onset of obesity (4), and an increase in DMH NPY gene expression and the consequential loss in CCK sensitivity may be the triggering factor in the development of hyperphagia.

Perspectives and Significance

Previous studies have established a role for DMH NPY in the control of food intake (3, 4); however, the neural pathways by which NPY modulates food intake, especially meal size, remain unclear. The present study improves our understanding of the interplay between DMH NPY signaling and feeding-related feedback signals. We found that changes in DMH NPY gene expression could affect CCK-induced satiety via modulation of brain stem catecholamine neuronal signaling. This work supports a therapeutic action of DMH NPY knockdown against hyperphagia and provides potential target(s) for the treatment of obesity.

GRANTS

This work was supported by National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases Grants DK-074269 (S. Bi) and DK-104867 (S. Bi).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

C.B.d.L.S. and S.B. conception and design of research; C.B.d.L.S. and Y.J.K. performed experiments; C.B.d.L.S. analyzed data; C.B.d.L.S. and S.B. interpreted results of experiments; C.B.d.L.S. prepared figures; C.B.d.L.S. drafted manuscript; C.B.d.L.S., T.H.M., and S.B. edited and revised manuscript; C.B.d.L.S. and S.B. approved final version of manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Babic T, Townsend RL, Patterson LM, Sutton GM, Zheng H, Berthoud HR. Phenotype of neurons in the nucleus of the solitary tract that express CCK-induced activation of the ERK signaling pathway. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 296: R845–R854, 2009. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.90531.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bellinger LL, Bernardis LL, Brooks S. The effect of dorsomedial hypothalamic nuclei lesions on body weight regulation. Neuroscience 4: 659–665, 1979. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(79)90142-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bi S, Kim YJ, Zheng F. Dorsomedial hypothalamic NPY and energy balance control. Neuropeptides 46: 309–314, 2012. doi: 10.1016/j.npep.2012.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bi S, Ladenheim EE, Schwartz GJ, Moran TH. A role for NPY overexpression in the dorsomedial hypothalamus in hyperphagia and obesity of OLETF rats. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 281: R254–R260, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bi S, Robinson BM, Moran TH. Acute food deprivation and chronic food restriction differentially affect hypothalamic NPY mRNA expression. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 285: R1030–R1036, 2003. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00734.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Blevins JE, Morton GJ, Williams DL, Caldwell DW, Bastian LS, Wisse BE, Schwartz MW, Baskin DG. Forebrain melanocortin signaling enhances the hindbrain satiety response to CCK-8. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 296: R476–R484, 2009. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.90544.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Blevins JE, Schwartz MW, Baskin DG. Evidence that paraventricular nucleus oxytocin neurons link hypothalamic leptin action to caudal brain stem nuclei controlling meal size. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 287: R87–R96, 2004. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00604.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chao PT, Yang L, Aja S, Moran TH, Bi S. Knockdown of NPY expression in the dorsomedial hypothalamus promotes development of brown adipocytes and prevents diet-induced obesity. Cell Metab 13: 573–583, 2011. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2011.02.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Corp ES, Melville LD, Greenberg D, Gibbs J, Smith GP. Effect of fourth ventricular neuropeptide Y and peptide YY on ingestive and other behaviors. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 259: R317–R323, 1990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Damanhuri HA, Burke PG, Ong LK, Bobrovskaya L, Dickson PW, Dunkley PR, Goodchild AK. Tyrosine hydroxylase phosphorylation in catecholaminergic brain regions: a marker of activation following acute hypotension and glucoprivation. PLoS One 7: e50535, 2012. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0050535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.de Lartigue G, Barbier de la Serre C, Espero E, Lee J, Raybould HE. Leptin resistance in vagal afferent neurons inhibits cholecystokinin signaling and satiation in diet induced obese rats. PLoS One 7: e32967, 2012. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0032967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.de Lartigue G, Lur G, Dimaline R, Varro A, Raybould H, Dockray GJ. EGR1 is a target for cooperative interactions between cholecystokinin and leptin, and inhibition by ghrelin, in vagal afferent neurons. Endocrinology 151: 3589–3599, 2010. doi: 10.1210/en.2010-0106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dockray GJ. Luminal sensing in the gut: an overview. J Physiol Pharmacol 54, Suppl 4: 9–17, 2003. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dodd GT, Worth AA, Nunn N, Korpal AK, Bechtold DA, Allison MB, Myers MG Jr, Statnick MA, Luckman SM. The thermogenic effect of leptin is dependent on a distinct population of prolactin-releasing peptide neurons in the dorsomedial hypothalamus. Cell Metab 20: 639–649, 2014. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2014.07.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fujisawa H, Okuno S. Regulatory mechanism of tyrosine hydroxylase activity. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 338: 271–276, 2005. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.07.183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Glass MJ, Chan J, Pickel VM. Ultrastructural localization of neuropeptide Y Y1 receptors in the rat medial nucleus tractus solitarius: relationships with neuropeptide Y or catecholamine neurons. J Neurosci Res 67: 753–765, 2002. doi: 10.1002/jnr.10185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Grove KL, Brogan RS, Smith MS. Novel expression of neuropeptide Y (NPY) mRNA in hypothalamic regions during development: region-specific effects of maternal deprivation on NPY and agouti-related protein mRNA. Endocrinology 142: 4771–4776, 2001. doi: 10.1210/endo.142.11.8498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Grove KL, Chen P, Koegler FH, Schiffmaker A, Susan Smith M, Cameron JL. Fasting activates neuropeptide Y neurons in the arcuate nucleus and the paraventricular nucleus in the rhesus macaque. Brain Res Mol Brain Res 113: 133–138, 2003. doi: 10.1016/S0169-328X(03)00093-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hayes MR, Skibicka KP, Leichner TM, Guarnieri DJ, DiLeone RJ, Bence KK, Grill HJ. Endogenous leptin signaling in the caudal nucleus tractus solitarius and area postrema is required for energy balance regulation. Cell Metab 11: 77–83, 2010. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2009.10.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kagotani Y, Hisano S, Tsuruo Y, Daikoku S, Okimura Y, Chihara K. Intragranular co-storage of neuropeptide Y and arginine vasopressin in the paraventricular magnocellular neurons of the rat hypothalamus. Cell Tissue Res 262: 47–52, 1990. doi: 10.1007/BF00327744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kanoski SE, Zhao S, Guarnieri DJ, DiLeone RJ, Yan J, De Jonghe BC, Bence KK, Hayes MR, Grill HJ. Endogenous leptin receptor signaling in the medial nucleus tractus solitarius affects meal size and potentiates intestinal satiation signals. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 303: E496–E503, 2012. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00205.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kumer SC, Vrana KE. Intricate regulation of tyrosine hydroxylase activity and gene expression. J Neurochem 67: 443–462, 1996. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1996.67020443.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee SJ, Kirigiti M, Lindsley SR, Loche A, Madden CJ, Morrison SF, Smith MS, Grove KL. Efferent projections of neuropeptide Y-expressing neurons of the dorsomedial hypothalamus in chronic hyperphagic models. J Comp Neurol 521: 1891–1914, 2013. doi: 10.1002/cne.23265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li C, Chen P, Smith MS. The acute suckling stimulus induces expression of neuropeptide Y (NPY) in cells in the dorsomedial hypothalamus and increases NPY expression in the arcuate nucleus. Endocrinology 139: 1645–1652, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lindgren N, Goiny M, Herrera-Marschitz M, Haycock JW, Hökfelt T, Fisone G. Activation of extracellular signal-regulated kinases 1 and 2 by depolarization stimulates tyrosine hydroxylase phosphorylation and dopamine synthesis in rat brain. Eur J Neurosci 15: 769–773, 2002. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2002.01901.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26a.Longo Carbajosa NA, Corradi G, Verrilli MA, Guil MJ, Vatta MS, Gironacci MM. Tyrosine hydroxylase is short-term regulated by the ubiquitin-proteasome system in PC12 cells and hypothalamic and brainstem neurons from spontaneously hypertensive rats: possible implications in hypertension. PLoS One 10: e0116597, 2015. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0116597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Luckman SM. Fos-like immunoreactivity in the brainstem of the rat following peripheral administration of cholecystokinin. J Neuroendocrinol 4: 149–152, 1992. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2826.1992.tb00152.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Maniscalco JW, Rinaman L. Overnight food deprivation markedly attenuates hindbrain noradrenergic, glucagon-like peptide-1, and hypothalamic neural responses to exogenous cholecystokinin in male rats. Physiol Behav 121: 35–42, 2013. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2013.01.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Marston OJ, Hurst P, Evans ML, Burdakov DI, Heisler LK. Neuropeptide Y cells represent a distinct glucose-sensing population in the lateral hypothalamus. Endocrinology 152: 4046–4052, 2011. doi: 10.1210/en.2011-1307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McMinn JE, Sindelar DK, Havel PJ, Schwartz MW. Leptin deficiency induced by fasting impairs the satiety response to cholecystokinin. Endocrinology 141: 4442–4448, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mietlicki-Baase EG, Ortinski PI, Rupprecht LE, Olivos DR, Alhadeff AL, Pierce RC, Hayes MR. The food intake-suppressive effects of glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor signaling in the ventral tegmental area are mediated by AMPA/kainate receptors. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 305: E1367–E1374, 2013. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00413.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Moran TH, Aja S, Ladenheim EE. Leptin modulation of peripheral controls of meal size. Physiol Behav 89: 511–516, 2006. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2006.04.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Murrin LC, Roth RH. Dopaminergic neurons: effects of electrical stimulation on dopamine biosynthesis. Mol Pharmacol 12: 463–475, 1976. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Paxinos G, Watson C. The Rat Brain in Stereotaxic Coordinates (6th ed.). San Diego, CA: Elsevier Academic Press, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rinaman L. Hindbrain noradrenergic lesions attenuate anorexia and alter central cFos expression in rats after gastric viscerosensory stimulation. J Neurosci 23: 10084–10092, 2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rinaman L, Hoffman GE, Dohanics J, Le WW, Stricker EM, Verbalis JG. Cholecystokinin activates catecholaminergic neurons in the caudal medulla that innervate the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus in rats. J Comp Neurol 360: 246–256, 1995. doi: 10.1002/cne.903600204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schwartz GJ, Moran TH. Leptin and neuropeptide y have opposing modulatory effects on nucleus of the solitary tract neurophysiological responses to gastric loads: implications for the control of food intake. Endocrinology 143: 3779–3784, 2002. doi: 10.1210/en.2002-220352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sheriff S, Chance WT, Iqbal S, Rizvi TA, Xiao C, Kasckow JW, Balasubramaniam A. Hypothalamic administration of cAMP agonist/PKA activator inhibits both schedule feeding and NPY-induced feeding in rats. Peptides 24: 245–254, 2003. doi: 10.1016/S0196-9781(03)00037-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sutton GM, Patterson LM, Berthoud HR. Extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2 signaling pathway in solitary nucleus mediates cholecystokinin-induced suppression of food intake in rats. J Neurosci 24: 10240–10247, 2004. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2764-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Uchoa ET, Zahm DS, de Carvalho Borges B, Rorato R, Antunes-Rodrigues J, Elias LL. Oxytocin projections to the nucleus of the solitary tract contribute to the increased meal-related satiety responses in primary adrenal insufficiency. Exp Physiol 98: 1495–1504, 2013. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.2013.073726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.van den Heuvel JK, Eggels L, Fliers E, Kalsbeek A, Adan RA, la Fleur SE. Differential modulation of arcuate nucleus and mesolimbic gene expression levels by central leptin in rats on short-term high-fat high-sugar diet. PLoS One 9: e87729, 2014. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0087729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Williams DL, Schwartz MW, Bastian LS, Blevins JE, Baskin DG. Immunocytochemistry and laser capture microdissection for real-time quantitative PCR identify hindbrain neurons activated by interaction between leptin and cholecystokinin. J Histochem Cytochem 56: 285–293, 2008. doi: 10.1369/jhc.7A7331.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yang L, Scott KA, Hyun J, Tamashiro KL, Tray N, Moran TH, Bi S. Role of dorsomedial hypothalamic neuropeptide Y in modulating food intake and energy balance. J Neurosci 29: 179–190, 2009. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4379-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yang Y, Moghadam AA, Cordner ZA, Liang NC, Moran TH. Long term exendin-4 treatment reduces food intake and body weight and alters expression of brain homeostatic and reward markers. Endocrinology 155: 3473–3483, 2014. doi: 10.1210/en.2014-1052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yao L, Fan P, Arolfo M, Jiang Z, Olive MF, Zablocki J, Sun HL, Chu N, Lee J, Kim HY, Leung K, Shryock J, Blackburn B, Diamond I. Inhibition of aldehyde dehydrogenase-2 suppresses cocaine seeking by generating THP, a cocaine use-dependent inhibitor of dopamine synthesis. Nat Med 16: 1024–1028, 2010. doi: 10.1038/nm.2200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]