Abstract

Channel activities of skeletal muscle ryanodine receptor (RyR1) are activated by micromolar Ca2+ and inactivated by higher (∼1 mM) Ca2+. To gain insight into a mechanism underlying Ca2+-dependent inactivation of RyR1 and its relationship with skeletal muscle diseases, we constructed nine recombinant RyR1 mutants carrying malignant hyperthermia or centronuclear myopathy-associated mutations and determined RyR1 channel activities by [3H]ryanodine binding assay. These mutations are localized in or near the RyR1 domains which are responsible for Ca2+-dependent inactivation of RyR1. Four RyR1 mutations (F4732D, G4733E, R4736W, and R4736Q) in the cytoplasmic loop between the S2 and S3 transmembrane segments (S2–S3 loop) greatly reduced Ca2+-dependent channel inactivation. Activities of these mutant channels were suppressed at 10–100 μM Ca2+, and the suppressions were relieved by 1 mM Mg2+. The Ca2+- and Mg2+-dependent regulation of S2–S3 loop RyR1 mutants are similar to those of the cardiac isoform of RyR (RyR2) rather than wild-type RyR1. Two mutations (T4825I and H4832Y) in the S4–S5 cytoplasmic loop increased Ca2+ affinities for channel activation and decreased Ca2+ affinities for inactivation, but impairment of Ca2+-dependent inactivation was not as prominent as those of S2–S3 loop mutants. Three mutations (T4082M, S4113L, and N4120Y) in the EF-hand domain showed essentially the same Ca2+-dependent channel regulation as that of wild-type RyR1. The results suggest that nine RyR1 mutants associated with skeletal muscle diseases were differently regulated by Ca2+ and Mg2+. Four malignant hyperthermia-associated RyR1 mutations in the S2–S3 loop conferred RyR2-type Ca2+- and Mg2+-dependent channel regulation.

Keywords: type-1 ryanodine receptor, malignant hyperthermia, centronuclear myopathy, central core disease, Ca2+-dependent inactivation

ryanodine receptor calcium release channels (RyRs) play pivotal roles in releasing Ca2+ from the sarcoplasmic reticulum, an intracellular membrane compartment, during action potentials in skeletal and cardiac muscle. RyRs are homotetramers of 565-kDa polypeptides and their channel activities are regulated by a number of physiological molecules and proteins, which include Ca2+, Mg2+, ATP, protein kinases, and calmodulin (4, 16, 21). Intracellular Ca2+ activates both skeletal (RyR1) and cardiac (RyR2) isoforms of RyR at micromolar concentrations. Both isoforms are inhibited by millimolar Ca2+, but inhibition of RyR2 requires ∼10 times higher concentrations of Ca2+ than RyR1. Generation of recombinant RyR1/RyR2 chimera channels allowed for the identification of regions involved in isoform-specific Ca2+-dependent channel inactivation (7, 8, 24). We found that two distinct domains in the C-terminal ∼1,000 amino acids of RyRs are involved in isoform-specific Ca2+-dependent channel inactivation (14). One domain contained two EF-hand-type Ca2+ binding motifs [RyR1 amino acids (aa) 4065–4298], and the other domain included the second transmembrane region (RyR1 aa 4630–4688). Replacing these two regions in RyR1 with the corresponding RyR2 sequences resulted in RyR2-type Ca2+-dependent inactivation (14).

Missense mutations in the human RYR1 gene have been found to be associated with skeletal myopathies including malignant hyperthermia (MH), central core disease (CCD), and centronuclear myopathy (CNM) (17, 19, 20, 27, 28). MH is a life-threatening condition in which anesthetic reagents such as halothane cause abnormal sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ release and increase muscle oxidative metabolism, resulting in an uncontrollable increase in body temperature. CCD is a congenital myopathy that causes gradually worsening muscle weakness after birth. Skeletal muscle cells of CCD patients show damaged areas, called cores, that are missing mitochondria and oxidative enzymes. A number of patients with CCD have a risk for MH susceptibility as well. CNM is another congenital myopathy in which there are a prominent number of myofibers with centrally located nuclei (19, 20). Phenotypes of CNM observed in muscle biopsies sometimes overlap with other congenital myopathies. In total, more than 200 point mutations in the RYR1 gene have been found to be linked to patients with MH or congenital myopathy (17, 27, 28).

In the present study, we hypothesized that nine skeletal disease-associated mutations, located in RyR1 regions (or flanking regions), previously shown to be involved in Ca2+-dependent channel inactivation (14) alter Ca2+-dependent regulation of RyR1 channel activity, resulting in abnormal Ca2+ homeostasis. We constructed three mutations in the EF-hand domain (T4082M, S4113L, and N4120Y) (18, 20, 29), four mutations in the S2–S3 cytoplasmic loop (F4732D, G4733E, R4736W, and R4736Q) (12, 23, 27, 29), and two mutations in the S4–S5 loop (T4825I and H4832Y) (1, 3). The [3H]ryanodine binding method was used to determine RyR1 channel activities, as [3H]ryanodine prefers to bind to RyRs in the open channel state (22, 33). We found that RyR1 mutations in the three different domains affected Ca2+- and Mg2+-dependent regulation of RyR1 differently.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials.

[3H]Ryanodine was obtained from PerkinElmer (Waltham, MA), unlabeled ryanodine from Calbiochem (La Jolla, CA), protease inhibitors from Thermo Scientific (Waltham, MA) and Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO), and human embryonic kidney (HEK) 293 cells from American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA). Full-length wild-type RyR1 and RyR2 cDNAs (13, 25) were kindly provided by Dr. Gerhard Meissner of University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and Dr. Junichi Nakai of Saitama University, Japan, respectively.

Construction of RyR cDNAs.

Full-length rabbit RyR1 and RyR2 were cloned into the mammalian expression vectors pCMV5 and pCIneo, respectively. Single and multiple base changes were introduced by Pfu-turbo polymerase-based chain reaction, by using a small DNA fragment of RyR1 as a template, mutagenic oligonucleotides, and a QuikChange site-directed mutagenesis kit (Agilent, Santa Clara, CA). The complete mutated DNA fragments amplified by PCR were confirmed by DNA sequencing and were cloned back to the original positions. Full-length expression plasmids were constructed by ligating three RyR1 fragments [ClaI-XhoI (polylinker-6598), XhoI-EcoRI (6598–11767), EcoRI-XbaI (11767-polylinker) carrying mutation] and pCMV5 expression vector (ClaI/XbaI cloning sites) as described previously (13). Sequences and numbering are consistent with previous studies (25, 34). In this paper, disease-associated RyR1 mutations in human patients were described with rabbit RyR1 sequence and numbering.

Expression of full-length RyRs in HEK293 cells.

RyR1 cDNAs were transiently expressed in HEK293 cells with FuGENE6 (Promega, Madison, WI) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The expression level of endogenous RyR protein is background level in HEK293 cells, which enables us to measure the channel activities of the recombinant wild-type and mutant RyRs by heterologous expression. Cells were maintained at 37°C with 5% CO2 in high-glucose Dulbecco's modified eagle medium containing 10% fetal bovine serum and plated the day before transfection. For each 10-cm tissue culture dish, 3.5 μg cDNA was used, and cells were harvested 48 h after transfection. To prepare crude membrane fractions, cells were homogenized in 0.3 M sucrose, 150 mM KCl, 20 mM imidazole (pH7.0), 0.1 mM EGTA, 1 mM oxidized glutathione, and protease inhibitors. Homogenates were centrifuged for 45 min at 100,000 × g, and pellets were resuspended in the aforementioned buffer solution without EGTA and glutathione.

[3H]Ryanodine binding assay.

Ryanodine binds specifically to RyRs and is widely used as a probe for RyR channel activity because of its preferential binding to the open state of the RyR channels (22, 33). The bound amount of [3H]ryanodine at equilibrium represents the RyR channel open probability. [3H]Ryanodine binding experiments were performed with crude membrane fractions at a relatively low [3H]ryanodine concentration to determine regulation of wild-type and mutant RyRs by Ca2+ and Mg2+ (14, 40). Unless otherwise indicated, membranes were incubated with 2.5–3 nM [3H]ryanodine in 20 mM HEPES (pH 7.4), 0.15 M sucrose, 200 mM KCl, 0.3 mM oxidized glutathione (GSSG), protease inhibitors, and various Ca2+ and Mg2+ concentrations. Nonspecific binding was determined with an 800- to 1,000-fold excess of unlabeled ryanodine. After 20 h, samples were diluted with six volumes of ice-cold water and placed on Whatman GF/B filters preincubated with 2% polyethyleneimine in water. Filters were washed three times with 5-ml ice-cold 100 mM KCl, 1 mM K-PIPES (pH 7.0) solution. The radioactivity remaining within the filters was determined by liquid scintillation counting to obtain bound [3H]ryanodine.

A nearly saturating [3H]ryanodine concentration of 20 nM was used to determine wild-type and mutant RyR expression levels. Maximal binding (Bmax) values of [3H]ryanodine were determined by incubating homogenates for 4 h with 20 nM [3H]ryanodine in 20 mM imidazole, pH 7.0, 0.6 M KCl, protease inhibitors, and 100 μM Ca2+. Nonspecific binding of [3H]ryanodine was determined in the presence of 2.5 mM EGTA and 2.5 μM unlabeled ryanodine. All experiments were performed at room temperature (22–24°C). The gain of activity for each RyR preparation was calculated by normalizing the peak values of Ca2+-dependent activity to Bmax values.

Free Ca2+ concentrations and data analysis.

Free Ca2+ concentrations in the solutions were obtained by including 5 mM EGTA and the appropriate amounts of CaCl2 in the absence of Mg2+ and ATP (pH 7.4), as determined by using the stability constants and the computer program published by Shoenmakers et al. (32) and Maxchelator (http://maxchelator.stanford.edu). Free Ca2+ concentrations were verified in the absence of Mg2+ and ATP with a Ca2+ selective electrode (Model 9720BNWP, Thermo Scientific). A standard curve for Ca2+ concentration was obtained from buffer solutions (pH 7.2–7.4) with known Ca2+ concentrations by using a Calcium Calibration Buffer kit (Biotium, Hayward, CA) (for <100 μM) and 1 M CaCl2 solution stock (Sigma-Aldrich) (for ≥100 μM). To determine and compare EC50 and IC50 of Ca2+ for each mutant, we prepared the Ca2+/EGTA buffer solutions in bulk for each free Ca2+ concentration and used them for [3H]ryanodine binding experiments of each mutant RyR. We assumed the same free Ca2+ concentrations in the presence and absence of Mg2+. Free Ca2+ concentrations below 1 μM may be slightly affected by 1 mM Mg2+. However, we found that these slight changes, which were calculated by the computer program (Maxchelator), did not affect the statistical analysis of EC50.

Ca2+-dependent activities of RyRs were normalized to the peak activity of each Ca2+-dependent curve, and half maximal concentrations of Ca2+ for activation and inactivation were derived as EC50 and IC50, respectively. Caffeine-dependent activities of RyRs were normalized to the activities at 10 mM caffeine in each experiment by (B − Bcaf0)/(Bcaf10 − Bcaf0) × 100, where B is the bound amount of [3H]ryanodine, Bcaf0 is bound amount at 0 mM caffeine, and Bcaf10 is bound amount at 10 mM caffeine. The data were fit by the Hill equation as follows

| (1) |

where Bpeak is the peak activity, KA is the activation Hill constant of caffeine, and n is a Hill coefficient.

Results are given as means ± SE. Significant differences in the data (P < 0.05) were determined by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's test.

RESULTS

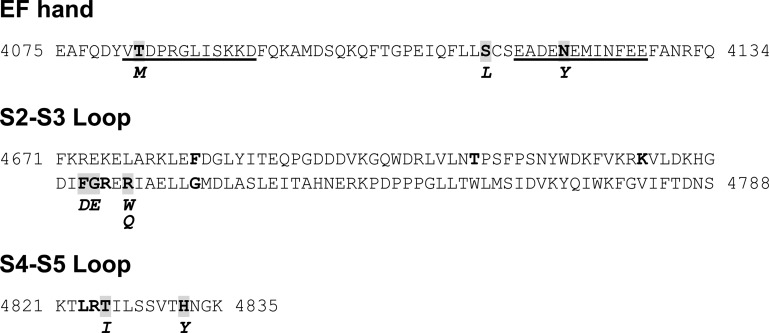

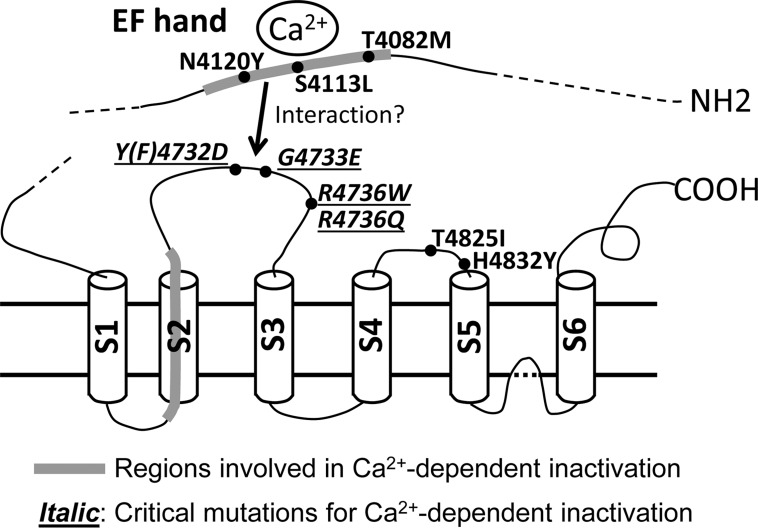

We previously reported that replacing the EF-hand and the second transmembrane (S2) regions in RyR1 with the corresponding RyR2 sequence impaired Ca2+-dependent inactivation of the RyR channel activity (14). In the present study, we tested the hypothesis that nine human disease-associated RyR1 mutations located in these regions or flanking regions, namely the EF-hand domain, S2–S3 loop, and S4–S5 loop of RyR1, alter the Ca2+-dependent regulation of RyR1 (Fig. 1). We used [3H]ryanodine binding assay, which has been widely used to determine the regulation of RyRs by Ca2+ and Mg2+ (5, 8, 22, 33). All mutant RyR1s retained the ability to bind [3H]ryanodine and yielded a peak-to-Bmax ratio of [3H]ryanodine binding similar to WT-RyR1 (Table 1).

Fig. 1.

Skeletal disease-associated mutations in RyR1. Amino acid sequences of three domains are shown. Underlines indicate EF-hand motifs. Bold letters denote MH, CCD, or CNM-linked mutation sites (https://cardiodb.org/Paralogue_Annotation/). Mutation sites characterized in this study are highlighted in gray, and mutations are shown in italic below the sequence.

Table 1.

Activities of wild-type and mutant RyRs

| Bpeak/Bmax, % | |

|---|---|

| WT-RyR1 | 47 ± 6 (5) |

| T4082M | 39 ± 3 (5) |

| S4113L | 39 ± 3 (5) |

| N4120Y | 49 ± 9 (5) |

| F4732D | 63 ± 7 (4) |

| G4733E | 62 ± 7 (4) |

| R4736W | 55 ± 8 (7) |

| R4736Q | 74 ± 7 (4) |

| T4825I | 61 ± 9 (7) |

| H4832Y | 57 ± 10 (4) |

| WT-RyR2 | 66 ± 4 (5) |

Values are means ± SE of the number of experiments indicated in parentheses. Activities of wild-type (WT) and mutant ryanodine receptors (RyRs) were obtained by normalizing the peak values of Ca2+-dependent activity in Fig. 2 to the Bmax values. None of the data of the mutants were significantly different from WT-RyR1 (one-way ANOVA).

Mutations in EF-hand domain.

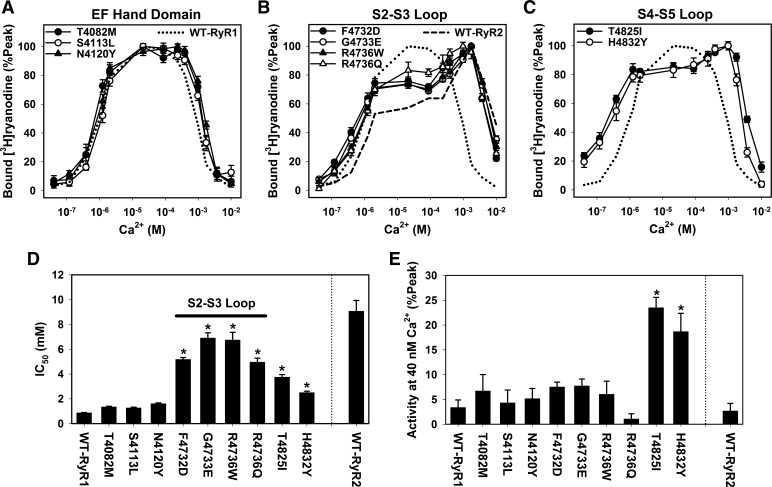

RyRs have two EF-hand motifs that bind Ca2+ with an affinity of 60 μM to 3.8 mM (38, 39). Two mutations in EF1 (T4082M) and EF2 (N4120Y), and another one between EF1 and EF2 (S4113L), are associated with MH or CNM (Fig. 1, Table 2) (18, 20, 29). We constructed three recombinant RyR1s carrying each individual mutation, expressed them in HEK293 cells, and determined Ca2+-dependent activity changes of the mutants by using the [3H]ryanodine binding method (Fig. 2A). We observed essentially no change in their apparent Ca2+ affinities for channel activation (EC50) compared with that of WT-RyR1 (Table 2). Affinities of Ca2+ for channel inactivation (IC50) were slightly but not significantly decreased (Fig. 2, A and D).

Table 2.

Activation of wild-type and mutant RyRs by Ca2+

| EC50, μM |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mutation | Myopathy | No Mg2+ | 1 mM Mg2+ | |

| WT-RyR1 | 1.0 ± 0.1 (5) | 2.0 ± 0.1 (4) | ||

| EF-hand | T4082M | MH | 0.74 ± 0.08 (5) | ND |

| S4113L | CNM | 1.2 ± 0.1 (5) | ND | |

| N4120Y | MH | 0.91 ± 0.11 (5) | ND | |

| S2–S3 loop | F4732D | MH | 0.66 ± 0.13 (4) | 1.4 ± 0.2 (7) |

| G4733E | MH | 0.73 ± 0.05 (4) | 1.4 ± 0.2 (5) | |

| R4736W | MH | 0.96 ± 0.09 (7) | 1.4 ± 0.1 (5) | |

| R4736Q | MH | 1.2 ± 0.1 (5) | 1.4 ± 0.2 (6) | |

| S4–S5 loop | T4825I | MH | 0.22 ± 0.02*(6) | 0.94 ± 0.05* (4) |

| H4832Y | MH | 0.41 ± 0.09*(5) | 0.51 ± 0.03* (4) | |

| WT-RyR2 | 4.2 ± 2.5 (5) | 1.9 ± 0.04 (8) | ||

Values are means ± SE of the number of experiments indicated in parentheses. EC50 values for Ca2+-dependent activation of wild-type and mutant RyRs were determined in the absence and presence of 1 mM Mg2+. RyR1 mutations are associated with either malignant hyperthermia (MH) or centronuclear myopathy (CNM).

P < 0.05 compared with WT-RyR1 by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's test among RyR1 groups (wild-type and mutant RyR1s). ND, not determined.

Fig. 2.

Ca2+-dependent activities of MH/CNM-associated RyR1 mutants. Ca2+-dependent changes in the activities of wild-type (WT) and mutant RyR1 were determined by the [3H]ryanodine binding method. Activities of mutant RyR1s carrying disease-associated mutations in EF-hand domain (A), S2–S3 loop (B), and S4–S5 loop (C) are shown together with that of WT-RyR1 (dotted line, mean values). A dashed line in B represents a mean value of WT-RyR2. D: IC50 values of wild-type and mutant RyRs. E: activities at 40 nM free Ca2+ were normalized to the peak activities for wild-type and each mutant RyR1. *P < 0.05 compared with WT-RyR1 by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's test among 10 sample groups (wild-type and mutant RyR1s). Data are shown as means ± SE (n = 4–7).

Mutations in the S2–S3 loop.

The S2–S3 cytoplasmic loop of RyR1 is composed of 118 amino acids and contains nine reported MH/CCD-linked point mutations (28). We determined the Ca2+ affinities for channel activation/inactivation of four RyR1 mutants (F4732D, G4733E, R4736W, and R4736Q) which are localized in a five amino acid stretch (Fig. 1) (12, 23, 27, 29). Note that F4732D of rabbit RyR1 corresponds to human MH mutation Y4733D. All four mutant RyR1s showed similar Ca2+-dependent activation and inactivation profiles of [3H]ryanodine binding (Fig. 2B). The activation phase was initially the same as WT-RyR1; however, it was followed by a plateau phase at 10–100 μM Ca2+ before reaching a peak value at ∼1 mM Ca2+. Ca2+ affinities for channel inactivation were greatly reduced compared with WT-RyR1. Average IC50 values were 5.2 ± 0.2, 6.9 ± 0.4, 6.7 ± 0.6, and 5.0 ± 0.3 mM (means ± SE, n = 4–7) for F4732D, G4733E, R4736W, and R4736Q mutants, respectively, that were five- to eightfold larger than that of WT-RyR1 (0.86 ± 0.03 mM, n = 5). Overall, the four mutants had a Ca2+ activation/inactivation profile more resembling WT-RyR2 than WT-RyR1, which suggested that each of the four RyR1 mutations conferred RyR2-type Ca2+-dependent regulation on RyR1.

Mutations in the S4–S5 loop.

Biochemical analyses and cryo-electron microscopy has shown that RyR1 has a short cytoplasmic loop linking the S4 and S5 transmembrane segments (S4–S5, Fig. 1) (9, 10, 41, 44). We constructed and characterized two MH-associated S4–S5 loop mutants, T4825I and H4832Y, using the [3H]ryanodine binding method (Fig. 2C) (1, 3) to compare their Ca2+-dependent activities with WT-RyR1 and the other RyR1 mutants (EF-hand and S2–S3 loop). In agreement with previous studies (2, 30, 31, 42, 43) the two mutants showed changes in both their Ca2+-dependent activation and inactivation compared with WT-RyR1 (Fig. 2C). However, changes in Ca2+-dependent inactivation were not as prominent as those of G4733E and R4736W mutants (Fig. 2D). Apparent EC50 values for Ca2+ activation of T4825I and H4832Y RyR1 channels were significantly different from WT-RyR1 (Table 2), as activities of these two mutants at 40 nM Ca2+ were significantly higher than WT-RyR1 (Fig. 2E). The results indicated that Ca2+-dependent activation of T4825I and H4832Y mutant channels were enhanced.

Effect of Mg2+ on RyR1 mutants.

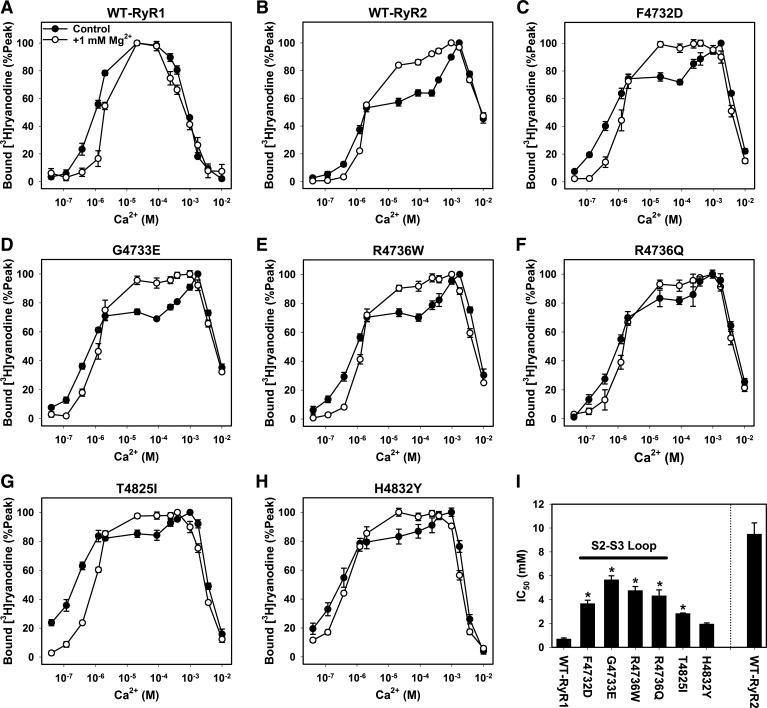

Chugun et al. (5) have reported that RyR2 activities in the rat ventricular microsomal fractions and recombinant RyR2 were suppressed at 10–100 μM Ca2+ and that the suppression was relieved by 1 mM Mg2+. As observed for WT-RyR2, we found that the suppression for S2–S3 loop mutants (F4732D, G4733E, R4736W, and R4736Q) at 10–100 μM Ca2+ was relieved by the addition of 1 mM Mg2+ to [3H]ryanodine binding media, which resulted in more bell-shaped Ca2+ activation/inactivation curves (Fig. 3). Average IC50 values of Ca2+ for channel activities were 3.7 ± 0.3, 5.7 ± 0.3, 4.8 ± 0.3, and 4.3 ± 0.5 mM (n = 5–7) for F4732D, G4733E, R4736W, and R4736Q mutants, respectively; they were significantly larger than that of WT-RyR1 (0.70 ± 0.09 mM, n = 4) (Fig. 3I). The affinities of Ca2+ for channel activation of these for S2–S3 loop mutants were essentially the same as WT-RyR1 (Table 2).

Fig. 3.

Ca2+-dependent activities of MH-associated RyR1 mutants in the presence of 1 mM Mg2+. A–H: Ca2+-dependent activities with and without 1 mM Mg2+ were determined for WT-RyR1, WT-RyR2, and six MH-associated RyR1 mutants. Data of Ca2+-dependent activities without 1 mM Mg2+ are from Fig. 2. Data are shown as means ± SE (n = 4–8). I: IC50 values of wild-type and mutant RyRs in the presence of 1 mM Mg2+ are shown. *P < 0.05 compared with WT-RyR1 by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's test among seven sample groups (wild-type and mutant RyR1s). Data are shown as means ± SE (n = 4–8).

We also determined the Ca2+-dependent channel activities of S4–S5 mutants (T4825I and H4832Y) in the presence of 1 mM Mg2+. The IC50 values of the two mutants were substantially higher than that of WT-RyR1 in the presence of Mg2+ (Fig. 3I), but the H4832Y mutant was not significantly different. Apparent affinities for Ca2+ activation (EC50) of the two mutants were significantly higher than WT-RyR1 (Table 2).

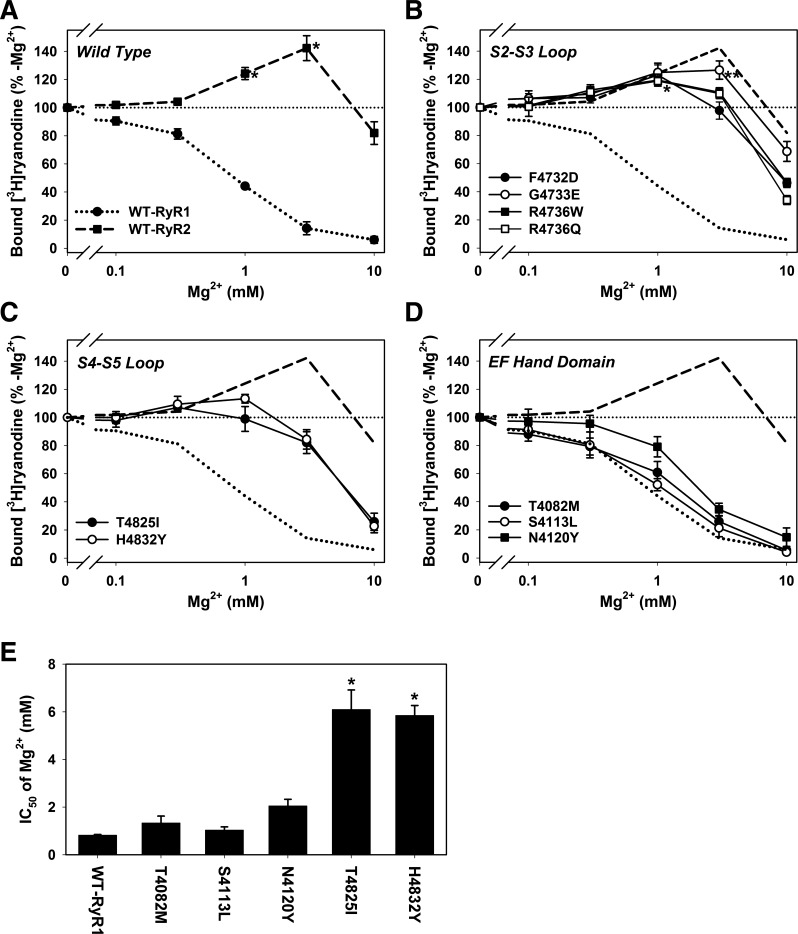

We compared the Mg2+ dependence of [3H]ryanodine binding to recombinant RyR1s and RyR2 at a Ca2+ concentration of 100 μM (Fig. 4), which maximally suppressed activities of WT-RyR2 and four S2–S3 loop RyR1 mutants (Fig. 3). As previously recognized (5, 42), Mg2+ inhibited WT-RyR1 in a concentration-dependent manner, whereas rabbit recombinant WT-RyR2 was activated by 1–3 mM Mg2+ but inhibited by 10 mM Mg2+ (Fig. 4A).

Fig. 4.

Effect of Mg2+ on MH/CNM-associated RyR1 mutants. Mg2+-dependent changes in the activities of wild-type and mutant RyR were determined at 100 μM Ca2+ by the [3H]ryanodine binding method. Activities of wild-type RyRs (A), S2–S3 loop mutants (B), S4–S5 loop mutants (C), and EF-hand mutants (D) are shown. Dotted and dashed lines in B, C, and D are mean values of WT-RyR1 and WT-RyR2, respectively. The smaller dotted line indicates the level at 100%. *P < 0.05 compared with control (-Mg2+) by one-way ANOVA. In B, *P < 0.05 for F4732D, G4733E, R4736W, and R4736Q mutants; **P < 0.05 for G4733E mutant. Data are shown as means ± SE (n = 4–6). E: IC50 values of WT-RyR1, EF-hand mutants, and S4–S5 loop mutants are shown. *P < 0.05 compared with WT-RyR1 by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s test. Data are shown as means ± SE (n = 4–5).

The four S2–S3 mutants showed a Mg2+ activation/inhibition profile similar to WT-RyR2 (Fig. 4B). G4733E-RyR1 was significantly activated by 1–3 mM Mg2+, and the other three mutants were activated by 1 mM Mg2+. Both S4–S5 loop mutations (T4825I and H4832Y) showed significantly reduced affinities of Mg2+ for channel inhibition compared with WT-RyR1, but these mutant channels were not significantly activated by Mg2+ (Fig. 4C). The IC50 values for Mg2+ inhibition were 6.1 ± 0.8 and 5.9 ± 0.4 mM for T4825I and H4832Y mutants, respectively, which were significantly higher than 0.82 ± 0.03 mM for WT-RyR1 (means ± SE, n = 4–5). The three EF-hand mutants were inhibited by Mg2+ in a concentration-dependent manner similar to WT-RyR1 (Fig. 4D). N4120Y mutations slightly reduced Mg2+ inhibitory effects, but the IC50 of Mg2+ was not significantly changed compared with that of WT-RyR1 (Fig. 4E). Taken together, the results suggested that MH-associated point mutations in the S2–S3 loop of RyR1 conferred RyR2-type Ca2+ and Mg2+ regulation.

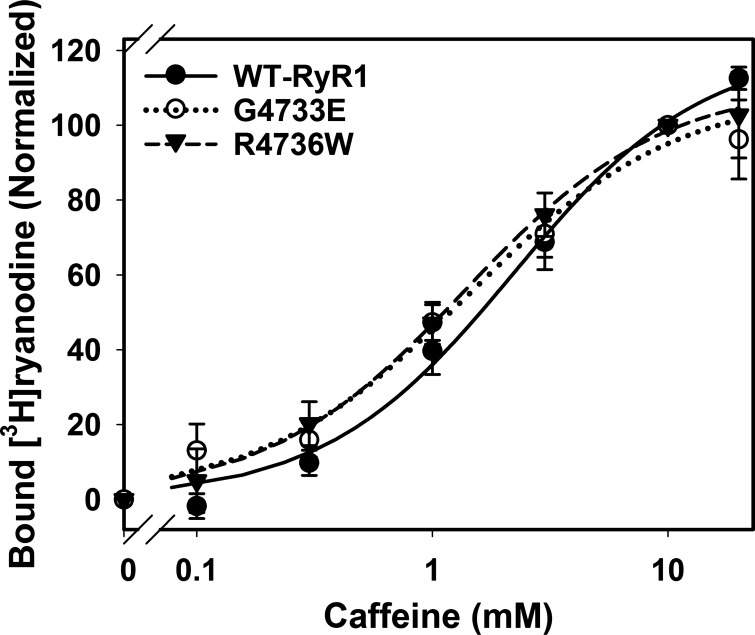

Effect of caffeine on G4733E and R4736W RyR1 mutants.

MH/CCD RyR1 mutations increased sensitivity for RyR agonists such as caffeine and halothane (35, 36, 42). We measured the effect of caffeine on G4733E and R4736W RyR1s, two mutants that showed the most pronounced changes in Ca2+ and Mg2+ regulations (Figs. 2–4).

Caffeine increased WT-RyR1 activity in a concentration-dependent manner with near saturating concentrations of 10–20 mM caffeine (Fig. 5), which is in agreement with previous observations (35, 36, 42). We found that both G4733E and R4736W mutations slightly increased caffeine affinities by ∼1.6-fold compared with WT-RyR1 (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Effect of caffeine on activities of G4733E and R4736W RyR1 mutants. Caffeine-dependent changes in the activities of wild-type, G4733E, and R4736W RyR1s were determined at 0.4 μM Ca2+ by [3H]ryanodine binding assays. Changes in the amount of bound [3H]ryanodine were normalized and fit by Eq. 1 as described in materials and methods. Data are shown as means ± SE (n = 4–15). There are no significant differences among three types of RyR1 at any tested caffeine concentrations by one-way ANOVA. Maximal amounts of bound [3H]ryanodine are 121 ± 9, 109 ± 9, and 111 ± 9% (10 mM caffeine as 100%); activation Hill constants of caffeine are 2.2 ± 0.5, 1.4 ± 0.4, and 1.4 ± 0.3 mM, and Hill coefficients are 1.1 ± 0.2, 1.0 ± 0.2, and 1.0 ± 0.2 for WT-RyR1, G4733E, and R4736W, respectively (fitted value ± regression SE).

DISCUSSION

Over 200 point mutations in RyR1 associated with MH or congenital myopathies including CCD and CNM have been determined by genetic screening of human patients. Of these, 35 mutations were validated to cause MH (i.e., causative mutations) by genetic, cellular, and biochemical characterizations (https://emhg.org/genetics/mutations-in-ryr1/). In the present study, we constructed and expressed seven mutant RyR1s carrying MH/CNM-associated mutations in EF-hand domain or S2–S3 loop as well as two MH causative mutants in S4–S5 loop (T4825I and H4832Y) and determined their Ca2+- and Mg2+-dependent regulation by [3H]ryanodine binding assay. Six mutations (T4082M, N4120Y, F4732D, G4733E, R4736W, and R4736Q) were identified in MH susceptible individuals/families in Europe, North America, or Japan (12, 18, 23, 27, 29). One mutation (S4113L) was found in an Asian female who was diagnosed with CNM (20). Patients were positive using the caffeine/halothane contracture test, Ca2+-induced Ca2+ release test, or histological analysis. The present study aimed to obtain a better understanding of how the mutations impair RyR1 channel activity. Two causative RyR1 mutations (T4825I and H4832Y) in the S4–S5 loop were included in the present study to compare their properties with those in the other two domains. As previously reported (2, 30, 31, 42, 43), the two mutants exhibited an altered Ca2+/Mg2+ regulation.

We found that MH-associated mutations in the S2–S3 loop (F4732D, G4733E, R4736W, and R4736Q) greatly reduced affinities of Ca2+ for channel inactivation (Figs. 2 and 3), whereas EC50 of Ca2+, representing an initial phase of Ca2+ activation, was only slightly changed (Table 2). These four mutations suppressed RyR1 activities at 10–100 μM Ca2+, and the suppressions were relieved by 1 mM Mg2+. Together, all four S2–S3 loop mutants showed Ca2+/Mg2+-dependent regulation similar to recombinant WT-RyR2. It is possible that activities of S2–S3 loop mutants are enhanced particularly at ∼1 mM Ca2+, which results in apparent suppressions of activities at 10–100 μM Ca2+, though the gains of activity of RyR1 mutants are comparable to that of WT-RyR1 (Table 1). Although it is widely accepted that the bell-shaped Ca2+-dependent [3H]ryanodine binding to RyRs represents Ca2+-dependent activation of RyRs by cytosolic micromolar Ca2+ and inhibition by cytosolic millimolar Ca2+ (see review in Ref. 6), we cannot rule out a possible millimolar luminal Ca2+ effect in this equilibrium binding assay. Single amino acid substitution in the cytoplasmic S2–S3 loop of RyR1 might have allosterically altered luminal Ca2+ regulation of RyR1. While further clinical and functional tests remain to be done to validate the four S2–S3 loop mutations as causative MH mutations, our studies point out that the S2–S3 loop may participate in the regulation of RyR1 by Ca2+ and Mg2+.

In a previous study, we found that two isoform-specific regions involved in Ca2+-dependent inactivation were located in the EF-hand domain and the second transmembrane region (S2), but not the S2–S3 loop. While an RyR1/RyR2 chimera carrying the RyR2 sequence of the S2–S3 loop showed essentially the same affinity of Ca2+ for channel inactivation as WT-RyR1 (14), our current results indicate that the S2–S3 loop is involved in Ca2+-dependent inactivation of RyR1. One possible mechanism is that the S2–S3 loop mediates functional signal transduction between two domains, the EF-hand and the S2 transmembrane segment in RyR1, and mutations in the S2–S3 loop in RyR1 possibly alter the functional coupling between these two domains (Fig. 6). The S2–S3 loop of RyR1 was shown to contain four to five α-helixes by studies with secondary structure prediction and 3D image analysis of cryo-electron microscopy (10, 41, 44). One of these is formed by RyR1 aa 4734–4741. In the secondary structure prediction programs (SABLE, http://sable.cchmc.org/, and Jpred 4, http://www.compbio.dundee.ac.uk/jpred4/), S2–S3 loop mutations (F4732D, G4733E, R4736W, and R4736Q) do not affect formation of this α-helix and minimally modify the neighboring structure (i.e., only one amino acid longer or shorter in formation of a neighboring α-helix), suggesting that these mutations are unlikely to cause large structural change.

Fig. 6.

A possible model of Ca2+-dependent inactivation of RyR1. Disease-associated RyR1 mutations in the EF-hand region, S2–S3 loop, and S4–S5 loop are shown. The regions involved in Ca2+-dependent channel inactivation are highlighted in gray.

Recently, the near-atomic level structure of RyR1 was shown by high-resolution cryo-electron microscopy and 3D image analysis (10, 41, 44). Zalk et al. (44) showed proximity between the EF-hand domain and the S2–S3 loop. While the structural data predicted a possible mechanism of two domains for Ca2+-dependent activation of RyR1, our current results from [3H]ryanodine binding assay suggested a potential role of S2–S3 loop for Ca2+-dependent inactivation. This cryo-electron microscopy study was done in the presence of 5 mM EGTA, yielding the structure of the closed channel (44). Thus we need to await the structure of the open RyR1 and the conformational changes between the EF-hand and S2–S3 loop upon Ca2+ binding to address the significance of two domains in regulating Ca2+-dependent gating. Recombinant studies with the EF-hand domains showed that the affinity of Ca2+ was 60 μM to 3.8 mM, which exceeds the concentration required for activation (38, 39). Scrambling two EF-hand motifs (EF1 and EF2) of RyR1 did not affect caffeine or depolarization-induced Ca2+ release in RyR1-expressing myotubes, whereas EF1-disrupted RyR1 showed slightly higher affinity of Ca2+ for channel activation (11). In addition, a mutant RyR2 lacking the entire EF-hand domain showed essentially the same Ca2+ activation as WT-RyR2, but the mutant was impaired in Ca2+-store overloaded-induced Ca2+ release (15). We observed no significant changes in the Ca2+-dependent activation and inactivation of ryanodine binding to EF-hand mutants T4802M, S4113L, and N4120Y. Channel activities of T4082M and S4113L-RyR1 were previously studied by using biopsies from patients harboring these mutations (18, 20). Skinned fiber preparation from a patient with T4082M mutation exhibited an enhanced Ca2+-induced Ca2+ release (18). In another study, KCl and RyR1 agonist (4-chloro-m-cresol)-induced Ca2+ release was increased in MyoD transfected skin fibroblasts that show a muscle-like phenotype from the patient with S4113L mutation compared with control cells (20). The apparent discrepancies between our results and the previous data suggest that other yet to be identified cellular factors have a role in the aberrant regulation of T4802M and S4113L-RyR1 mutants.

Two mutations in the S4–S5 loop were previously characterized in recombinant (T4825I and H4832Y) and in vivo (T4825I) studies (2, 30, 31, 42, 43). Our results with the two mutants were in agreement with these data and showed that the effects of two S4–S5 loop mutations differed from those of four S2–S3 loop mutations. All six mutations altered Ca2+-dependent inactivation, but impairments of Ca2+-dependent inactivation were more prominent in S2–S3 loop mutants. Changes in Ca2+ activation were observed only in S4–S5 loop mutants. Although allosteric effects of mutations have to be taken into account, taken together, the S4–S5 loop of RyR1 seems to be involved in Ca2+-dependent regulation, especially Ca2+ activation. In addition, 1 mM Mg2+ activated S2–S3 loop mutants but not S4–S5 loop mutants (Fig. 4).

In vitro experiments showed that RyR1 inhibition by Ca2+ required 0.5–1.0 mM, which was somewhat beyond the physiological concentration of intracellular Ca2+. However, single-channel studies showed that Ca2+ flux through the RyR1 channel from lumen to cytoplasm inhibited RyR1, which suggested that local Ca2+ concentration around the Ca2+ inactivation site of RyR1 reached millimolar levels (37). Termination of Ca2+ sparks, elementary Ca2+ release events, in frog skeletal muscle depended on the amount of released Ca2+ (26). Therefore, an altered Ca2+-dependent inactivation of RyR1, possibly caused by anesthetic reagents such as halothane, may result in the release of abnormal amounts of Ca2+ from the sarcoplasmic reticulum.

In conclusion, MH-associated RyR1 mutations in the S2–S3 cytoplasmic loop confer RyR2 type Ca2+ and Mg2+ regulation on RyR1. The results suggest that these mutant RyR1s do not readily close during excitation-contraction coupling, leading to intracellular Ca2+ overload, which is often observed in MH skeletal pathology.

GRANTS

Support for this study was provided by National Institutes of Health Grants R03-AR-061030 and UL1-TR-001450, American Heart Association Grant 10SDG3500001, and National Science Foundation Grant EPS0903795 (to N. Yamaguchi).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

A.C.G., T.W.H., and N.Y. performed experiments; A.C.G., T.W.H., and N.Y. analyzed data; A.C.G., T.W.H., and N.Y. interpreted results of experiments; A.C.G., T.W.H., and N.Y. edited and revised manuscript; A.C.G., T.W.H., and N.Y. approved final version of manuscript; N.Y. conception and design of research; N.Y. prepared figures; N.Y. drafted manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors are grateful to Drs. Martin Morad, Gerhard Meissner, Yukiko Sugi, Lars Cleemann, and Xiao-Hua Zhang for their valuable suggestions and to Shogo Enomoto and Jordan S. Carter for their technical assistance.

REFERENCES

- 1.Anderson AA, Brown RL, Polster B, Pollock N, Stowell KM. Identification and biochemical characterization of a novel ryanodine receptor gene mutation associated with malignant hyperthermia. Anesthesiology 108: 208–215, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barrientos GC, Feng W, Truong K, Matthaei KI, Yang T, Allen PD, Lopez JR, Pessah IN. Gene dose influences cellular and calcium channel dysregulation in heterozygous and homozygous T4826I-RYR1 malignant hyperthermia-susceptible muscle. J Biol Chem 287: 2863–2876, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brown RL, Pollock AN, Couchman KG, Hodges M, Hutchinson DO, Waaka R, Lynch P, McCarthy TV, Stowell KM. A novel ryanodine receptor mutation and genotype-phenotype correlation in a large malignant hyperthermia New Zealand Maori pedigree. Hum Mol Genet 9: 1515–1524, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Capes EM, Loaiza R, Valdivia HH. Ryanodine receptors. Skelet Muscle 1: 18, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chugun A, Sato O, Takeshima H, Ogawa Y. Mg2+ activates the ryanodine receptor type 2 (RyR2) at intermediate Ca2+ concentrations. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 292: C535–C544, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Coronado R, Morrissette J, Sukhareva M, Vaughan DM. Structure and function of ryanodine receptors. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 266: C1485–C1504, 1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Du GG, Khanna VK, MacLennan DH. Mutation of divergent region 1 alters caffeine and Ca2+ sensitivity of the skeletal muscle Ca2+ release channel (ryanodine receptor). J Biol Chem 275: 11778–11783, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Du GG, MacLennan DH. Ca2+ inactivation sites are located in the COOH-terminal quarter of recombinant rabbit skeletal muscle Ca2+ release channels (ryanodine receptors). J Biol Chem 274: 26120–26126, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Du GG, Sandhu B, Khanna VK, Guo XH, MacLennan DH. Topology of the Ca2+ release channel of skeletal muscle sarcoplasmic reticulum (RyR1). Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 99: 16725–16730, 2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Efremov RG, Leitner A, Aebersold R, Raunser S. Architecture and conformational switch mechanism of the ryanodine receptor. Nature 517: 39–43, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fessenden JD, Feng W, Pessah IN, Allen PD. Mutational analysis of putative calcium binding motifs within the skeletal ryanodine receptor isoform, RyR1. J Biol Chem 279: 53028–53035, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Galli L, Orrico A, Cozzolino S, Pietrini V, Tegazzin V, Sorrentino V. Mutations in the RYR1 gene in Italian patients at risk for malignant hyperthermia: evidence for a cluster of novel mutations in the C-terminal region. Cell Calcium 32: 143–151, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gao L, Tripathy A, Lu X, Meissner G. Evidence for a role of C-terminal amino acid residues in skeletal muscle Ca2+ release channel (ryanodine receptor) function. FEBS Lett 412: 223–226, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gomez AC, Yamaguchi N. Two regions of the ryanodine receptor calcium channel are involved in Ca2+-dependent inactivation. Biochemistry 53: 1373–1379, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Guo W, Sun B, Xiao Z, Liu Y, Wang Y, Zhang L, Wang R, Chen SRW. The EF-hand Ca2+ binding domain is not required for cytosolic Ca2+ activation of the cardiac ryanodine receptor. J Biol Chem 291: 2150–2160, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hamilton SL, Serysheva II. Ryanodine receptor structure: progress and challenges. J Biol Chem 284: 4047–4051, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hwang JH, Zorzato F, Clarke NF, Treves S. Mapping domains and mutations on the skeletal muscle ryanodine receptor channel. Trends Mol Med 18: 644–657, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ibarra M CA, Wu S, Murayama K, Minami N, Ichihara Y, Kikuchi H, Noguchi S, Hayashi YK, Ochiai R, Nishino I. Malignant hyperthermia in Japan: mutation screening of the entire ryanodine receptor type 1 gene coding region by direct sequencing. Anesthesiology 104: 1146–1154, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jungbluth H, Gautel M. Pathogenic mechanisms in centronuclear myopathies. Front Aging Neurosci 6: 339, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jungbluth H, Zhou H, Sewry CA, Robb S, Treves S, Bitoun M, Guicheney P, Buj-Bello A, Bönnemann C, Muntoni F. Centronuclear myopathy due to a de novo dominant mutation in the skeletal muscle ryanodine receptor (RYR1) gene. Neuromuscul Disord 17: 338–345, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Meissner G. Regulation of mammalian ryanodine receptors. Front Biosci 7: d2072–d2080, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Meissner G, el-Hashem A. Ryanodine as a functional probe of the skeletal muscle sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ release channel. Mol Cell Biochem 114: 119–123, 1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Monnier N, Kozak-Ribbens G, Krivosic-Horber R, Nivoche Y, Qi D, Kraev N, Loke J, Sharma P, Tegazzin V, Figarella-Branger D, Roméro N, Mezin P, Bendahan D, Payen JF, Depret T, MacLennan DH, Lunardi J. Correlations between genotype and pharmacological, histological, functional, and clinical phenotypes in malignant hyperthermia susceptibility. Hum Mutat 26: 413–425, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nakai J, Gao L, Xu L, Xin C, Pasek DA, Meissner G. Evidence for a role of C-terminus in Ca2+ inactivation of skeletal muscle Ca2+ release channel (ryanodine receptor). FEBS Lett 459: 154–158, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nakai J, Imagawa T, Hakamata Y, Shigekawa M, Takeshima H, Numa S. Primary structure and functional expression from cDNA of the cardiac ryanodine receptor/calcium release channel. FEBS Lett 271: 169–177, 1990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ríos E, Zhou J, Brum G, Launikonis BS, Stern MD. Calcium-dependent inactivation terminates calcium release in skeletal muscle of amphibians. J Gen Physiol 131: 335–348, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Robinson R, Carpenter D, Shaw MA, Halsall J, Hopkins P. Mutations in RYR1 in malignant hyperthermia and central core disease. Hum Mutat 27: 977–989, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rosenberg H, Sambuughin N, Riazi S, Dirksen R. Malignant Hyperthermia Susceptibility (Online). GeneReviews, Seattle, WA. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK1146/ [19 Sept. 2016]. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sambuughin N, Holley H, Muldoon S, Brandom BW, de Bantel AM, Tobin JR, Nelson TE, Goldfarb LG. Screening of the entire ryanodine receptor type 1 coding region for sequence variants associated with malignant hyperthermia susceptibility in the north american population. Anesthesiology 102: 515–521, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sato K, Pollock N, Stowell KM. Functional studies of RYR1 mutations in the skeletal muscle ryanodine receptor using human RYR1 complementary DNA. Anesthesiology 112: 1350–1354, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sato K, Roesl C, Pollock N, Stowell KM. Skeletal muscle ryanodine receptor mutations associated with malignant hyperthermia showed enhanced intensity and sensitivity to triggering drugs when expressed in human embryonic kidney cells. Anesthesiology 119: 111–118, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schoenmakers TJ, Visser GJ, Flik G, Theuvenet AP. CHELATOR: an improved method for computing metal ion concentrations in physiological solutions. Biotechniques 12: 870–879, 1992. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sutko JL, Airey JA, Welch W, Ruest L. The pharmacology of ryanodine and related compounds. Pharmacol Rev 49: 53–98, 1997. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Takashima H, Nishimura S, Matsumoto T, Ishida H, Kangawa K, Minamino N, Matsuo H, Ueda M, Hanaoka M, Hirose T, Numa S. Primary structure and expression from complementary DNA of skeletal muscle ryanodine receptor. Nature 339: 439–445, 1989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tong J, McCarthy TV, MacLennan DH. Measurement of resting cytosolic Ca2+ concentrations and Ca2+ store size in HEK-293 cells transfected with malignant hyperthermia or central core disease mutant Ca2+ release channels. J Biol Chem 274: 693–702, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tong J, Oyamada H, Demaurex N, Grinstein S, McCarthy TV, MacLennan DH. Caffeine and halothane sensitivity of intracellular Ca2+ release is altered by 15 calcium release channel (ryanodine receptor) mutations associated with malignant hyperthermia and/or central core disease. J Biol Chem 272: 26332–26339, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tripathy A, Meissner G. Sarcoplasmic reticulum lumenal Ca2+ has access to cytosolic activation and inactivation sites of skeletal muscle Ca2+ release channel. Biophys J 70: 2600–2615, 1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Xiong H, Feng X, Gao L, Xu L, Pasek DA, Seok JH, Meissner G. Identification of a two EF-hand Ca2+ binding domain in lobster skeletal muscle ryanodine receptor/Ca2+ release channel. Biochemistry 37: 4804–4814, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Xiong L, Zhang JZ, He R, Hamilton SL. A Ca2+-binding domain in RyR1 that interacts with the calmodulin binding site and modulates channel activity. Biophys J 90: 173–182, 2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yamaguchi N, Xu L, Pasek DA, Evans KE, Chen SRW, Meissner G. Calmodulin regulation and identification of calmodulin binding region of type-3 ryanodine receptor calcium release channel. Biochemistry 44: 15074–15081, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yan Z, Bai XC, Yan C, Wu J, Li Z, Xie T, Peng W, Yin CC, Li X, Scheres SH, Shi Y, Yan N. Structure of the rabbit ryanodine receptor RyR1 at near-atomic resolution. Nature 517: 50–55, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yang T, Ta TA, Pessah IN, Allen PD. Functional defects in six ryanodine receptor isoform-1 (RyR1) mutations associated with malignant hyperthermia and their impact on skeletal excitation-contraction coupling. J Biol Chem 278: 25722–25730, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yuen B, Boncompagni S, Feng W, Yang T, Lopez JR, Matthaei KI, Goth SR, Protasi F, Franzini-Armstrong C, Allen PD, Pessah IN. Mice expressing T4826I-RYR1 are viable but exhibit sex- and genotype-dependent susceptibility to malignant hyperthermia and muscle damage. FASEB J 26: 1311–1322, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zalk R, Clarke OB, des Georges A, Grassucci RA, Reiken S, Mancia F, Hendrickson WA, Frank J, Marks AR. Structure of a mammalian ryanodine receptor. Nature 517: 44–49, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]