Abstract

BACKGROUND

A large proportion of justice-involved individuals have mental health issues and substance use disorders (SUD) that are often untreated due to high rates of uninsurance. However, roughly half of justice-involved individuals were estimated to be newly eligible for health insurance through the Affordable Care Act (ACA).

OBJECTIVE

We aimed to assess health insurance trends among justice-involved individuals before and after implementation of the ACA’s key provisions, the dependent coverage mandate and Medicaid expansion, and to examine the relationship between health insurance and treatment for behavioral health conditions.

DESIGN

Repeated and pooled cross-sectional analyses of data from the National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH).

PARTICIPANTS

Nationally representative sample of 15,899 adults age 19–64 years between 2008 and 2014 with a history of justice involvement during the prior 12 months.

MAIN MEASURES

Uninsurance rates between 2008 and 2014 are reported. Additional outcomes include adjusted treatment rates for depression, serious mental illness, and SUD by insurance status.

KEY RESULTS

The dependent coverage mandate was associated with a 13.0 percentage point decline in uninsurance among justice-involved individuals age 19–25 years (p < 0.001). Following Medicaid expansion, uninsurance declined among justice involved individuals of all ages by 9.7 percentage points (p < 0.001), but remained 16.3 percentage points higher than uninsurance rates for individuals without justice involvement (p < 0.001). In pooled analyses, Medicaid, relative to uninsurance and private insurance, was associated with significantly higher treatment rates for illicit drug abuse/dependence and depression.

CONCLUSION

Given the high prevalence of mental illness and substance use disorders among justice-involved populations, persistently elevated rates of uninsurance and other barriers to care remain a significant public health concern. Sustained outreach is required to reduce health insurance disparities between individuals with and without justice involvement. Public insurance appears to be associated with higher treatment rates, relative to uninsurance and private insurance, among justice-involved individuals.

KEY WORDS: health policy, vulnerable populations, healthcare reform, criminal justice

INTRODUCTION

Approximately 7 million individuals, 2.8 % of the adult population, are under correctional supervision on any given day in the United States.1 Individuals currently or recently in prison or jail, on probation or parole, or under arrest are often referred to as justice-involved.2 , 3 Although most studies of justice-involved individuals do not include all of these subgroups, existing evidence suggests that approximately 70 % of justice-involved individuals have a substance use disorder (SUD) or mental health issue.4 – 7 Yet, treatment among individuals with recent justice involvement has historically been inadequate due to lack of health insurance coverage8 – 10 and other barriers to care, including troubles navigating the healthcare system post release,11 disruption of medication during incarceration,12 and lack of behavioral health services.13

Roughly half of justice-involved individuals are expected to be eligible for health insurance through the Affordable Care Act (ACA),10 , 14 and many believe insurance expansion offers an opportunity to improve access to substance abuse and mental health treatment for this population.5 , 14 , 15 One recent report suggested that the ACA improved insurance rates among justice-involved individuals with SUD.16 However, to date, no national reports have assessed insurance trends among the general justice-involved population following implementation of either the ACA’s dependent coverage mandate, which expanded parental health insurance to children age 19–25,17 , 18 or Medicaid expansion and Marketplace plans. Furthermore, the relationship between health insurance and mental health and SUD treatment has not been investigated among a national cohort of justice-involved individuals.

To address this gap in knowledge, we analyzed data from the National Survey of Drug Use and Health (NSDUH) to assess whether uninsured rates for justice-involved individuals age 19–25 decreased following implementation of the dependent coverage mandate in September 2010. We also assessed whether uninsured rates declined among justice-involved individuals of all ages following national health reform initiatives that began in January 2014. Finally, we examined the association between health insurance (Medicaid vs. private vs. uninsured) and treatment among justice-involved individuals with mental illness and SUD to provide insight into the potential effect of health insurance expansion among this population.

METHODS

Data Source and Study Population

We analyzed the seven most recent years of data (2008–2014) from the National Survey of Drug Use and Health (NSDUH), a nationally representative, cross-sectional survey of non-institutionalized men and women that measures the prevalence of drug use and mental health disorders in the United States.19 Response rates in each year were above 70 %. The survey is sponsored by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAHMSA) and is conducted by RTI International, Research Triangle Park, North Carolina. We restricted our sample to non-elderly men and women age 19–64, because this age group was the target population for the ACA’s key provisions to expand health insurance coverage. Our analysis did not require institutional review board approval because it falls under the University of Michigan’s policy for research using publicly available data sets.

Key Variables and Outcome Measures

Justice-involved individuals were defined as those who reported being arrested and booked (excluding minor traffic violations), paroled, or on probation in the 12 months preceding the survey interview date.

An individual was determined to be uninsured if they were not enrolled in a private or public health insurance plan at the time of interview. For purposes of this study, health insurance categorization was mutually exclusive. Those enrolled in a private plan were excluded from the Medicaid category. Individuals not enrolled in a private plan or Medicaid were labelled as “Other.” Because NSDUH samples individuals evenly throughout the entire year, insurance estimates represent an average over all four quarters in each year, unless otherwise specified.

Questions related to illicit drug abuse/dependence, alcohol abuse/dependence, and depression are based on DSM IV criteria. Illicit drug abuse/dependence is a composite score of any cocaine, heroin, non-medical prescription opioid, or stimulant abuse/dependence in the last 12 months. Estimates of serious mental illness (SMI) are derived from a prediction model developed by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAHMSA) to measure SMI prevalence. SAHMSA’s prediction model utilizes the Kessler Psychological Distress Scale (K6) and the World Health Organization Disability Assessment Schedule (WHODAS).19

All measures of treatment are based on self-report. Depression treatment was defined as receiving any counseling or pharmacotherapy for depression within the last 12 months. Treatment for alcohol abuse/dependence was defined as any type of treatment for alcohol use within the last 12 months. Illicit drug use treatment was defined as any type of treatment for illicit drug use in the past 12 months. Treatment for serious mental illness was defined as receiving any inpatient treatment, outpatient treatment, or pharmacotherapy for mental health in the last 12 months.

Statistical Analysis

We calculated weighted frequencies to compare sociodemographic characteristics and prevalence of depression, SMI, alcohol abuse/dependence, and illicit drug abuse/dependence among those with and without justice involvement. Chi-square tests were performed to compare individuals with and without justice-involvement.

We compared insurance rates among individuals age 19–25, with and without justice-involvement, to individuals age 26–34 using logistic regression. A dichotomous pre-post variable was created to distinguish the periods of time before (prior to quarter 4 of 2010) and after (beginning quarter 1 of 2011) implementation of the dependent coverage mandate. For this analysis only, we did not include quarter 4 of 2010 because it was considered a transitional period, and we did not include 2014 data due to additional policy changes that took place during that year. Justice-involvement was interacted with age group and the pre-post variable in our logistic regression model. Adjusted insurance rates were obtained using predictive margins after controlling for gender, race/ethnicity, and income as a percent of the federal poverty level. Difference-in-differences were calculated using linear combinations of adjusted insurance rates.

We tabulated the proportion of uninsured each year for individuals of all ages with and without justice involvement. Uninsurance rates in 2014 among justice-involved individuals were compared to uninsurance rates in preceding years using logistic regression. Changes in type of insurance (i.e., Medicaid) among justice-involved individuals between 2013 and 2014 were compared using chi-square tests. We compared changes in uninsurance between individuals with and without justice involvement using multivariable logistic regression; to allow for comparisons of trends between groups, we interacted survey year with justice involvement (justice involvement vs. no justice involvement) and controlled for age, race, and gender. We used a difference-in-differences approach to compare uninsurance declines between 2013 and 2014 among individuals with and without justice involvement.

We pooled data from 2008 to 2014 and used multivariable logistic regression, controlling for age, race, gender, and survey year, to examine associations between health insurance coverage and treatment for depression, SMI, alcohol abuse/dependence, and illicit drug abuse/dependence among justice-involved individuals with those conditions. We pooled data for these analyses because small sample sizes in individual years resulted in estimates with large standard errors using repeated cross sections. We analyzed data using Stata SE version 14.1 (StataCorp, College Station, TX) and utilized complex survey design methods to account for clustered sampling. All data are weighted, unless otherwise noted, to enable nationally representative inferences. Stata’s subpopulation commands were used for accurate variance estimation. Two-sided p values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Study Population Characteristics

Our unweighted, pooled sample consisted of 15,899 individuals with and 218,595 individuals without justice involvement in the last 12 months. Justice-involved individuals accounted for 4.6 % of our weighted sample and are representative of 8.6 million individuals in the United States between 2008 and 2014. They had statistically significantly different sociodemographic characteristics, self-reported health, and disease prevalence compared to people with no justice involvement (Table 1). In particular, justice-involved individuals had a statistically significant higher prevalence of depression, serious mental illness, alcohol abuse or dependence, and illicit drug abuse or dependence. Justice-involved individuals were also younger and less likely to be female or non-Hispanic white.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic characteristics of non-elderly adults in the National Survey of Drug Use and Health, 2008–2014

| No. (Weighted %) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristic | Recent justice involvement (n = 15,899) | No justice involvement (n = 218,595) | P value |

| Male | 10,903 (71.8) | 98,177 (47.9) | <0.001 |

| Age, y | <0.001 | ||

| 19–25 | 10,209 (30.8) | 97,753 (15.0) | |

| 26–34 | 2,798 (27.9) | 38,950 (19.2) | |

| 35–49 | 2,315 (28.1) | 54,965 (33.4) | |

| 50–64 | 577 (13.1) | 26,927 (32.3) | |

| Race/ethnicity | <0.001 | ||

| White, non-Hispanic | 8,486 (56.0) | 137,019 (65.2) | |

| Black, non-Hispanic | 3,052 (20.9) | 26,519 (11.7) | |

| Hispanic | 2,850 (18.5) | 35,353 (15.6) | |

| Other | 1,511 (4.6) | 19,704 (7.5) | |

| Not high school graduate | 4,724 (28.5) | 26,583 (11.5) | <0.001 |

| Fair/poor self-reported health | 2,161 (18.0) | 19,864 (11.3) | <0.001 |

| Depression* | 1,859 (14.0) | 17,570 (7.3) | <0.001 |

| Serious mental illness* | 1,313 (10.5) | 10,010 (4.3) | <0.001 |

| Alcohol abuse/dependence* | 5,027 (29.4) | 21,394 (7.3) | <0.001 |

| Illicit drug abuse/dependence*,† | 1,519 (9.1) | 3,178 (1.1) | <0.001 |

*Within last 12 months

†Includes abuse/dependence of cocaine, heroin, non-medical prescription opioids, or stimulants

Dependent Coverage Mandate

Following implementation of the dependent coverage mandate in September 2010, uninsurance rates declined substantially for justice-involved individuals age 19–25 compared to justice-involved individuals age 26–34 (Fig. 1). After adjusting for gender, race, and income, we found a statistically significant reduction in uninsurance among justice-involved individuals age 19–25 (Table 2). Gains in insurance were due to an increase in private insurance coverage among individuals ages 19–25, relative to those ages 26–34. Consistent with previous analyses,20 we found that uninsurance rates also declined among individuals age 19–25 without a history of justice involvement (−6.5 %; P < 0.001). Declines in uninsurance following the dependent coverage mandate were significantly larger for justice-involved individuals compared to individuals without justice involvement (−6.5 %; p = 0.03).

Figure 1.

Uninsurance rates following the dependent coverage mandate in September 2010* by age group and justice-involvement history (* 2010 estimates do not include data from quarter 4)

Table 2.

Effect of the dependent coverage provision on health insurance coverage for individuals with recent criminal justice involvement*

| Outcome | Pre period (2008, Q1-2010, Q3) | Post period (2011, Q1-2013, Q4) | Difference-in-differences | 95 % CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Uninsurance | ||||

| 19–25 | 40.1 % | 31.8 % | −13.0 %† | (−18.8, -7.2) |

| 26–34 | 37.1 % | 41.8 % | ||

| Private insurance | ||||

| 19–25 | 40.2 % | 47.0 % | 13.1 %† | (7.6, 18.7) |

| 26–34 | 39.2 % | 32.9 % | ||

| Medicaid insurance | ||||

| 19–25 | 13.9 % | 14.3 % | 0.7 % | (−3.5, 4.9) |

| 26–34 | 17.1 % | 16.8 % | ||

*All analyses adjusted for age, gender, and income; † p < 0.001

Medicaid Expansion and Marketplace Plans

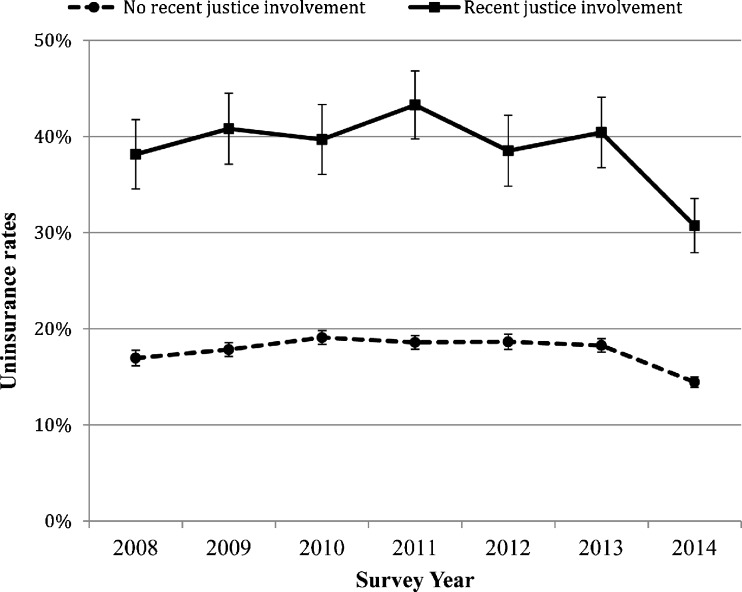

Uninsurance rates among justice-involved individuals declined substantially (Fig. 2) following implementation of Medicaid expansion and Marketplace plans in 2014. Uninsurance rates for justice-involved individuals in 2014 were lower than any prior year in our study (p < 0.005), but remained statistically significantly higher than uninsurance rates for those without justice involvement in multivariable analyses (difference, 16.3 %; p < 0.001; Adjusted difference, 11.4 %; p < 0.001). Uninsurance declines between 2013 and 2014 did not differ significantly between individuals with and without a history of justice involvement after controlling for age, gender, and race (difference-in-differences, −4.3 %; p = 0.07).

Figure 2.

Uninsurance rates by criminal justice involvement among adults 19–64, United States, 2008–2014

A decline in uninsurance among justice-involved individuals between 2013 and 2014 was due mostly to a statistically significant increase in Medicaid enrollment from 2013 to 2014 (6.3 %; p < 0.001) (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Type of insurance among justice-involved individuals age 19–64, United States, 2013 to 2014. (*p < 0.001)

Access to Mental Health and SUD Treatment

Among justice-involved individuals with depression based on DSM IV criteria, Medicaid, but not private insurance, was associated with significantly higher levels of treatment in the 2008–2014 period compared to uninsurance [Average treatment effect (ATE), (17.2 %; p < 0.001)] (Fig. 4). Medicaid and private insurance were both associated with significantly higher levels of treatment among justice-involved individuals with serious mental illness compared to those without insurance [ATE, (24.3 %; p < 0.001), (14.8 %; p < 0.05), respectively]. Among justice-involved individuals with alcohol abuse/dependence, Medicaid and private insurance were also associated with higher levels of treatment in adjusted analyses [ATE, (6.6 %; p < 0.05), (6.0 %; p < 0.05), respectively]. Finally, Medicaid alone was associated with SUD treatment among those with illicit drug abuse/dependence (ATE, 12.6 %; p < 0.05). Justice-involved individuals with Medicaid were significantly more likely than individuals with private insurance to receive treatment for illicit drug abuse/ dependence (ATE, 16.6 %; p = 0.003) and depression (ATE, 9.2 %; p = 0.02).

Figure 4.

Adjusted* treatment rates for behavioral health disorders by insurance status among justice-involved individuals, 2008–2014. (*Adjusted for age, race, gender, and survey wave; † p = 0.057;‡ p < 0.05; § p < 0.001)

DISCUSSION

In this nationally representative study of non-elderly justice-involved adults in the United States, we found that uninsurance rates declined substantially for individuals age 19–25 years after implementation of the dependent coverage mandate in 2010. Uninsurance declined for justice-involved individuals of all ages following expansion of Medicaid, subsidized private insurance, and the individual mandate under the ACA in 2014. Uninsurance decreased in 2014 mostly due to an increase in Medicaid enrollment. However, uninsured rates among justice-involved individuals remained approximately two times higher than uninsured rates among individuals without justice involvement. In pooled analyses, Medicaid coverage was associated with higher rates of mental health and SUD treatment among justice-involved individuals, but overall rates of treatment for SUD remained low. These data suggest that justice-involved individuals are gaining health insurance coverage under the ACA, but may still face barriers to care for some behavioral health conditions.

The dependent coverage mandate, which expanded private health insurance to dependents ages 19–25 in September 2010,21 was associated with a dramatic decrease in uninsurance among justice-involved individuals, due primarily to an increase in private insurance coverage. The mandate decreased uninsurance to a larger degree for justice-involved individuals compared to individuals without a history of justice involvement. Although Medicaid has traditionally been the key source of coverage for justice-involved individuals,22 , 23 our results suggest that private health insurance reforms may improve coverage for a subset of this vulnerable population. In fact, private health insurance reforms that target young individuals may disproportionately improve access for justice-involved populations because they are younger than the general population.

We found that uninsurance declined among the general justice-involved population following implementation of Medicaid expansion and Marketplace plans. Our findings expand on a recent study that found uninsurance declined among substance users with recent justice involvement.16 Although uninsurance reached historic lows among the justice-involved population, we found that they still remain substantially higher than uninsurance rates among the general public.

Persistently elevated uninsurance among justice-involved individuals, following several years of expanded dependent coverage and the first year of Medicaid expansion and subsidized private insurance, may partly be explained by the 24 states choosing to forego Medicaid expansion. Many of these states have above average incarceration rates and incarcerated populations.1 , 24 Several states have also developed unique insurance enrollment processes for justice-involved individuals that may not have been optimized in the first year of Medicaid expansion.25 For instance, some jails and prisons began allowing Medicaid enrollment during incarceration, accepting alternative forms of identification, and developing electronic enrollment systems in 2014.26 Follow-up study is needed to assess whether coverage has increased among justice-involved individuals due to these enrollment efforts or increasing familiarity with eligibility over time, and as more states adopt Medicaid expansion. Additionally, future work should investigate differences between states that have and have not expanded Medicaid.

The ACA is expected to improve access to mental health and substance use services.27 , 28 In pooled analyses, we found that both Medicaid and private insurance, compared to uninsurance, are associated with treatment for serious mental illness and alcohol abuse treatment among justice-involved individuals with those conditions, although treatment for alcohol abuse in particular remains disturbingly low. We also found that Medicaid, but not private insurance, was associated with treatment among justice-involved individuals with illicit drug abuse/dependence or depression. Our finding that Medicaid is associated with higher treatment rates for some behavioral health conditions compared to private insurance builds upon previous work indicating that Medicaid improves access to behavioral health care for low-income adults.29 , 30 Our findings suggest that Medicaid expansion may be of greater benefit for this population than private insurance expansion, perhaps because Medicaid offers improved care coordination to connect individuals to services31 , 32 or because Medicaid providers are more familiar with SUDs, which are more prevalent among low-income populations.33

We note, however, that we were unable to determine when individuals accessed treatment services relative to their justice involvement. Because NSDUH is a cross-sectional survey, we could only examine whether justice involvement and treatment occurred in the preceding 12 months. Future work should compare trends in treatment rates for justice-involved individuals as Medicaid programs continue to develop integrated medical homes with physical health, mental health, and SUD treatment services.34

Our study has important limitations. NSDUH is a household survey that excludes individuals who are homeless. Because justice-involved individuals are disproportionately homeless or unstably housed,35 they may be under-represented in this study. Treatment data and health insurance status are also self-reported and are available for only one year after Medicaid expansion and Marketplace implementation. Finally, degree of justice involvement and length of incarceration could not be determined, nor could justice involvement beyond the previous 12 months; these factors may alter disease prevalence and health outcomes. These limitations notwithstanding, we were able to provide national estimates of health insurance coverage among a vulnerable population soon after implementation of the ACA’s key provisions.

CONCLUSION

Although uninsured rates declined substantially among justice-involved individuals age 19–25 following implementation of the dependent coverage mandate in 2010 and among individuals of all ages following Medicaid expansion and Marketplace plans in 2014, disparities in health insurance persisted between individuals with and without criminal justice involvement at the end of 2014. Our findings highlight the potential impact of the ACA on mental health treatment for justice-involved individuals, but indicate that, while coverage (especially Medicaid) is associated with improved treatment rates for mental illness and substance use disorders, many barriers remain. Persistently high uninsurance rates, lack of care coordination,36 and poor access to high quality behavioral health treatment8 remain critical public health issues given the high prevalence of mental health and substance use disorders among justice-involved individuals. Continued outreach is needed to close the insurance gap between individuals with and without criminal justice involvement, to ensure that individuals eligible for public insurance or insurance subsidies are enrolled and, once enrolled, have access to robust behavioral health services.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Funders

This research was funded with support from the Robert Wood Johnson Clinical Scholars Program, the University of Michigan, and Ann Arbor VA Healthcare System.

Conflict of Interest

All authors declare no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kaeble D, Glaze L, Tsoutis A, Minton T. Correctional Populations in the United States, 2014. Washington, D.C.: Bureau of Justice Statistics; 2015. http://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/cpus14.pdf. Accessed July 17, 2016.

- 2.Boutwell AE, Freedman J. Coverage expansion and the criminal justice–involved population: implications for plans and service connectivity. Health Aff (Millwood) 2014;33(3):482–486. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2013.1131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gates A, Artiga S, Rudowitz R. Health coverage and care for the adult criminal justice-involved population. The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation. http://kff.org/uninsured/issue-brief/health-coverage-and-care-for-the-adult-criminal-justice-involved-population/. Published September 5, 2014. Accessed July 17, 2016.

- 4.Mallik-Kane K, Visher CA. Health and Prisoner Reentry: How Physical, Mental, and Substance Abuse Conditions Shape the Process of Reintegration. Washington, D.C.: Urban Institute; 2008. http://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/alfresco/publication-pdfs/411617-Health-and-Prisoner-Reentry.PDF. Accessed July 17, 2016.

- 5.Marks JS, Turner N. The critical link between health care and jails. Health Aff (Millwood) 2014;33(3):443–447. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2013.1350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Glaze LE, James DJ. Mental Health Problems of Prison and Jail Inmates. Bureau of Justice Statistics; 2006. http://www.bjs.gov/index.cfm?ty=pbdetail&iid=789. Accessed July 17, 2016.

- 7.Cloud D. On Life Support: Public Health in the Age of Mass Incarceration. New York, NY: Vera Institute of Justice; 2014. http://www.vera.org/pubs/public-health-mass-incarceration. Accessed July 17, 2016.

- 8.Cuellar AE, Cheema J. Health care reform, behavioral health, and the criminal justice population. J Behav Health Serv Res. 2014;41(4):447–459. doi: 10.1007/s11414-014-9404-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Frank JW, Linder JA, Becker WC, Fiellin DA, Wang EA. Increased hospital and emergency department utilization by individuals with recent criminal justice involvement: results of a national survey. J Gen Intern Med. 2014;29(9):1226–1233. doi: 10.1007/s11606-014-2877-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cuellar AE, Cheema J. As roughly 700,000 prisoners are released annually, about half will gain health coverage and care under federal laws. Health Aff (Millwood) 2012;31(5):931–938. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.0501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Binswanger IA, Whitley E, Haffey P-R, Mueller SR, Min S-J. A patient navigation intervention for drug-involved former prison inmates. Subst Abuse. 2015;36(1):34–41. doi: 10.1080/08897077.2014.932320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang EA, Hong CS, Shavit S, Sanders R, Kessell E, Kushel MB. Engaging Individuals Recently Released From Prison Into Primary Care: A Randomized Trial. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(9):e22–e29. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.300894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Binswanger IA, Nowels C, Corsi KF, et al. “From the prison door right to the sidewalk, everything went downhill”, A qualitative study of the health experiences of recently released inmates. Int J Law Psychiatry. 2011;34(4):249–255. doi: 10.1016/j.ijlp.2011.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Regenstein M, Rosenbaum S. What the Affordable Care Act means for people with jail stays. Health Aff (Millwood) 2014;33(3):448–454. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2013.1119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bechelli MJ, Caudy M, Gardner TM, et al. Case studies from three states: breaking down silos between health care and criminal justice. Health Aff (Millwood) 2014;33(3):474–481. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2013.1190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Saloner B, Bandara SN, McGinty EE, Barry CL. Justice-Involved Adults With Substance Use Disorders: Coverage Increased But Rates Of Treatment Did Not In 2014. Health Aff (Millwood) 2016;35(6):1058–1066. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2016.0005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Busch SH, Golberstein E, Meara E. ACA Dependent Coverage Provision Reduced High Out-Of-Pocket Health Care Spending For Young Adults. Health Aff (Millwood) 2014;33(8):1361–1366. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2014.0155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Saloner B, Cook BL. An ACA Provision Increased Treatment For Young Adults With Possible Mental Illnesses Relative To Comparison Group. Health Aff (Millwood) 2014;33(8):1425–1434. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2014.0214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.National Survey on Drug Use and Health, 2013 - Codebook. Washington, D.C.: United States Department of Health and Human Services. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality; 2014. https://www.icpsr.umich.edu/icpsrweb/ICPSR/studies/35509. Accessed July 17, 2016.

- 20.Sommers BD, Buchmueller T, Decker SL, Carey C, Kronick R. The Affordable Care Act Has Led To Significant Gains In Health Insurance And Access To Care For Young Adults. Health Aff (Millwood) 2013;32(1):165–174. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2012.0552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mulcahy A, Harris K, Finegold K, Kellermann A, Edelman L, Sommers BD. Insurance Coverage of Emergency Care for Young Adults under Health Reform. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(22):2105–2112. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1212779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Morrissey JP, Steadman HJ, Dalton KM, Cuellar A, Stiles P, Cuddeback GS. Medicaid enrollment and mental health service use following release of jail detainees with severe mental illness. Psychiatr Serv. 2006;57(6):809–815. doi: 10.1176/ps.2006.57.6.809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wakeman SE, McKinney ME, Rich JD. Filling the gap: the importance of Medicaid continuity for former inmates. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24(7):860–862. doi: 10.1007/s11606-009-0977-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Status of state action on the Medicaid expansion decision. The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation. http://kff.org/health-reform/state-indicator/state-activity-around-expanding-medicaid-under-the-affordable-care-act/. Published March 14, 2016. Accessed July 17, 2016.

- 25.Bandara SN, Huskamp HA, Riedel LE, et al. Leveraging the Affordable Care Act to enroll justice-involved populations in Medicaid: state and local efforts. Health Aff (Millwood) 2015;34(12):2044–2051. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2015.0668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zemel S, Corso C, Cardwell A. Toolkit: state strategies to enroll justice-involved individuals in health coverage. National Academy for State Health Policy. http://www.nashp.org/toolkit-state-strategies-to-enroll-justice-involved-individuals-in-health-coverage/. Published November 16, 2015. Accessed July 17, 2016.

- 27.Barry CL, Huskamp HA. Moving beyond parity — mental health and addiction care under the ACA. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(11):973–975. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1108649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mechanic D. Seizing opportunities under the Affordable Care Act for transforming the mental and behavioral health system. Health Aff (Millwood) 2012;31(2):376–382. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.0623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Creedon TB, Cook BL. Access To Mental Health Care Increased But Not For Substance Use, While Disparities Remain. Health Aff (Millwood) 2016;35(6):1017–1021. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2016.0098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wen H, Druss BG, Cummings JR. Effect of Medicaid Expansions on Health Insurance Coverage and Access to Care among Low-Income Adults with Behavioral Health Conditions. Health Serv Res. 2015;50(6):1787–1809. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.12411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Riedel LE, Barry CL, McGinty EE, et al. Improving Health Care Linkages for Persons The Cook County Jail Medicaid Enrollment Initiative. J Correct Health Care. 2016;22(3):189–199. doi: 10.1177/1078345816653199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Beronio K, Glied S, Frank R. How the affordable care act and mental health parity and addiction equity act greatly expand coverage of behavioral health care. J Behav Health Serv Res. 2014;41(4):410–428. doi: 10.1007/s11414-014-9412-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gryczynski J, Schwartz RP, O’Grady KE, Restivo L, Mitchell SG, Jaffe JH. Understanding Patterns Of High-Cost Health Care Use Across Different Substance User Groups. Health Aff (Millwood) 2016;35(1):12–19. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2015.0618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Somers SA, Nicolella E, Hamblin A, McMahon SM, Heiss C, Brockmann BW. Medicaid expansion: considerations for states regarding newly eligible jail-involved individuals. Health Aff (Millwood) 2014;33(3):455–461. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2013.1132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.The Growth of Incarceration in the United States: Exploring Causes and Consequences. Washington, D.C.: National Research Council of The National Academies; 2014. http://www.nap.edu/catalog/18613. Accessed July 17, 2016.

- 36.Patel K, Boutwell A, Brockmann BW, Rich JD. Integrating correctional and community health care for formerly incarcerated people who are eligible for Medicaid. Health Aff (Millwood) 2014;33(3):468–473. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2013.1164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]