Abstract

Kv7.2 and Kv7.3 subunits underlie the M-current, a neuronal K+ current characterized by an absolute functional requirement for phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate (PIP2). Kv7.2 gene mutations cause early-onset neonatal seizures with heterogeneous clinical outcomes, ranging from self-limiting benign familial neonatal seizures to severe early-onset epileptic encephalopathy (Kv7.2-EE). In this study, the biochemical and functional consequences prompted by a recurrent variant (R325G) found independently in four individuals with severe forms of neonatal-onset EE have been investigated. Upon heterologous expression, homomeric Kv7.2 R325G channels were non-functional, despite biotin-capture in Western blots revealed normal plasma membrane subunit expression. Mutant subunits exerted dominant-negative effects when incorporated into heteromeric channels with Kv7.2 and/or Kv7.3 subunits. Increasing cellular PIP2 levels by co-expression of type 1γ PI(4)P5-kinase (PIP5K) partially recovered homomeric Kv7.2 R325G channel function. Currents carried by heteromeric channels incorporating Kv7.2 R325G subunits were more readily inhibited than wild-type channels upon activation of a voltage-sensitive phosphatase (VSP), and recovered more slowly upon VSP switch-off. These results reveal for the first time that a mutation-induced decrease in current sensitivity to PIP2 is the primary molecular defect responsible for Kv7.2-EE in individuals carrying the R325G variant, further expanding the range of pathogenetic mechanisms exploitable for personalized treatment of Kv7.2-related epilepsies.

Phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate (PIP2), a negatively charged lipid only found in the inner leaflet of the plasma membrane, regulates several classes of ion channels, with few exhibiting an absolute functional dependence on PIP2 levels. Among these, Kv7 voltage-dependent potassium (K+) channels only conduct current when membrane PIP2 levels achieve critical values1,2,3,4. Heteromeric assembly of Kv7.2 and Kv7.3 subunits (encoded by the KCNQ2 and KCNQ3 genes, respectively) underlie the M-current (IKM), a slowly activating and deactivating neuronal K+ current which regulates excitability in the sub-threshold range for action potential generation, thus contributing to network oscillation and synchronization5. Depletion of membrane PIP2 upon activation of Gq-coupled receptors inhibits IKM, increasing neuronal excitability2,3. In addition, PIP2 exposure reverses homomeric Kv7.2 and heteromeric Kv7.2 + Kv7.3 current rundown occurring spontaneously in excised patches3. Single channel recordings from Kv7 channels of various subunit compositions revealed that when PIP2 is depleted the open probability approaches zero; increasing PIP2 levels induces a concentration-dependent increase in channel open probability, without changing the single channel conductance, the ionic selectivity, or the number of channels at the plasma membrane6.

Mutations in Kv7.2 are responsible for neonatal-onset epileptic diseases with a heterogeneous phenotypic presentation7. On the benign end of the spectrum is familial neonatal seizures (BFNS), an autosomal-dominant epilepsy characterized by recurrent seizures beginning in the first days of life and remitting after a few weeks or months, with mostly normal interictal EEG, neuroimaging, and psychomotor development. By contrast, de novo missense Kv7.2 mutations can lead to a severe epileptic encephalopathy (Kv7.2-EE), in which neonates develop pharmacoresistant seizures with distinct EEG and neuroradiological features, and various degrees of developmental delay8. De novo missense Kv7.2 mutations are among the most common causes of early-onset EEs9,10.

Both loss-of-function11,12 and gain-of-function13,14 molecular mechanisms have been identified in Kv7.2-EE; understanding the molecular pathogenesis in Kv7.2-EE is crucial to deduce genotype-phenotype correlations which may improve diagnostic, prognostic and therapeutic approaches. In this work, we have explored the molecular pathogenesis of a Kv7.2 mutation (R325G) found recurrently in three cases of Kv7.2-EE with early-onset seizures, burst-suppression pattern at the EEG, and profound global developmental delay15,16; the same variant has been more recently reported in a fourth patient with atypical presentation (neonatal-onset seizures) of the Kleefstra syndrome, a genetic disorder characterized by intellectual disability, limited or absent speech, hypotonia, synophrys, hypertelorism, and microcephaly17. The results obtained suggest that the R325G mutation severely impaired Kv7.2 channel function by reducing channel apparent affinity for PIP2; therefore, strategies increasing cellular PIP2 levels might provide therapeutic benefit in Kv7.2-EE patients carrying this and, possibly, other mutations affecting PIP2-dependent regulation.

Results

Functional and biochemical characterization of homomeric and heteromeric channels carrying Kv7.2 R325G subunits

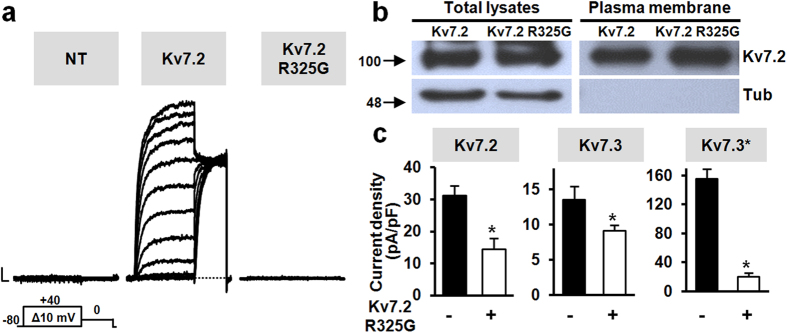

Homomeric Kv7.2 channels expressed in Chinese Hamster Ovary (CHO) cells by transient transfection carried robust outward K+ currents activating at about −40 mV and showing slow activation and deactivation kinetics, and lack of inactivation. Instead, no current could be recorded from cells transfected with Kv7.2 R325G cDNA; macroscopic current densities at 0 mV in Kv7.2 R325G-transfected and non-transfected cells were identical, being respectively 0.7 ± 0.1 pA/pF and 1.1 ± 0.1 pA/pF (p > 0.05) (Fig. 1a). Despite such dramatic loss of function, Western-blot experiments revealed a similar amount of Kv7.2 or Kv7.2 R325G subunits in both total lysates and plasma membrane-isolated fractions from CHO cells (Fig. 1b); in fact, the average values for the ODQ2Tot/ODTub ratios (in total lysates) and the ODQ2Biot/ODQ2Tot ratios (in biotinylated plasma membrane-enriched fractions) were 0.85 ± 0.13 and 1.15 ± 0.11, or 0.71 ± 0.03 and 0.85 ± 0.17, in Kv7.2- or Kv7.2 R325G-transfected cells, respectively (n = 4; p > 0.05).

Figure 1. Functional and biochemical characterization of Kv7.2 R325G subunits.

(a) Macroscopic currents from CHO cells in response to the voltage protocol shown; NT: non-transfected cells. Current scale: 200 pA; time scale: 200 ms. (b) Western blot analysis of proteins from total lysates (left) or biotinylated plasma membrane fractions (right) from CHO cells transfected with the indicated constructs. Higher and lower blots were probed with anti-Kv7.2 or anti-α-tubulin antibodies, as indicated. Numbers on the left correspond to the molecular masses of the protein markers. For clarity, the images shown are cropped from full-length gels; these are shown as Supplementary Information (Supplementary Fig. 2). (c) Current densities (0 mV) in cells co-expressing Kv7.2 R325G subunits and Kv7.2 (n = 11 and 20 in the absence and in the presence of Kv7.2 R325G subunits, respectively), Kv7.3 (n = 15 and 13 in the absence and in the presence of Kv7.2 R325G subunits, respectively), or Kv7.3* (n = 18 and 17 in the absence and in the presence of Kv7.2 R325G subunits, respectively) subunits. Asterisks indicate values significantly different (p < 0.05) versus respective controls.

Having detected a significant plasma membrane expression of non-functional Kv7.2 R325G mutant subunits, their possible inhibitory effects on the currents carried by Kv7.2 and/or Kv7.3 channels were evaluated. As shown in Fig. 1c, current densities at 0 mV in cells co-transfected with Kv7.2 and Kv7.2 R325G cDNAs (1.8 μg + 1.8 μg) was lower than that in cells transfected with Kv7.2 cDNA (1.8 μg). Similarly, co-expression of Kv7.2 R325G with Kv7.3 subunits also reduced current density; more pronounced inhibitory effects were observed when Kv7.3 subunits carrying the A315T pore mutation (Kv7.3*)18,19 were used to enhance macroscopic current size. Altogether, these results suggested that Kv7.2 R325G subunits exerted significant dominant-negative effects when expressed together with Kv7.2, Kv7.3 or Kv7.3* subunits.

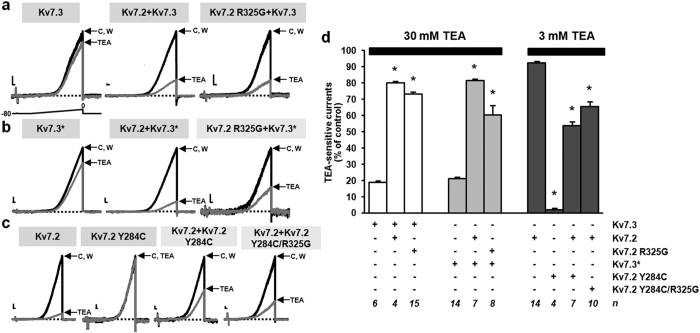

Pharmacological experiments with tetraethylammonium (TEA) provided further evidence for Kv7.2 R325G subunits incorporation into heteromeric channels with Kv7.2, Kv7.3 or Kv7.3* subunits. In fact, when TEA-insensitive Kv7.3 subunits20 were expressed together with Kv7.2 R325G subunits, currents showed a higher sensitivity to blockade by 30 mM TEA, identical to that of Kv7.2 + Kv7.3 heteromers (Fig. 2a). Similar results were observed when Kv7.3* subunits were used for these experiments (Fig. 2b). Conversely, to study heteromerization between Kv7.2 and Kv7.2 R325G subunits, a pore mutation (Y284C) was introduced to reduce TEA sensitivity21; heteromeric channels assembled upon Kv7.2 and Kv7.2 Y284C subunits or Kv7.2 and Kv7.2 Y284C/R325G double mutant subunits co-expression both showed an intermediate sensitivity between TEA-sensitive Kv7.2 and TEA-insensitive Kv7.2 Y284C homomeric channels (Fig. 2c). In Fig. 2d, a quantification of the pooled data from these experiments is reported. Overall, these results suggest that Kv7.2 R325G subunits were effectively incorporated into heteromeric channels with Kv7.2 or Kv7.3 subunits.

Figure 2. TEA-sensitivity of heteromeric channels carrying Kv7.2 R325G subunits.

(a,b,c) Representative current responses to voltage ramps from −80 mV to 0 mV from the indicated channels recorded in control solution C, upon perfusion for 2 min with 30 mM (a,b) or 3 mM (c) TEA, and upon drug washout (W). Current scale: 50 pA; time scale: 200 ms. (d) Average data from experiments such as those shown in panels a (white bars), b (light grey bars), or c (dark grey bars). Asterisks indicate values significantly different from respective controls (leftmost bar in each group; p < 0.05). In the last row, the number of experiments performed (n), each from a separate cell, is indicated.

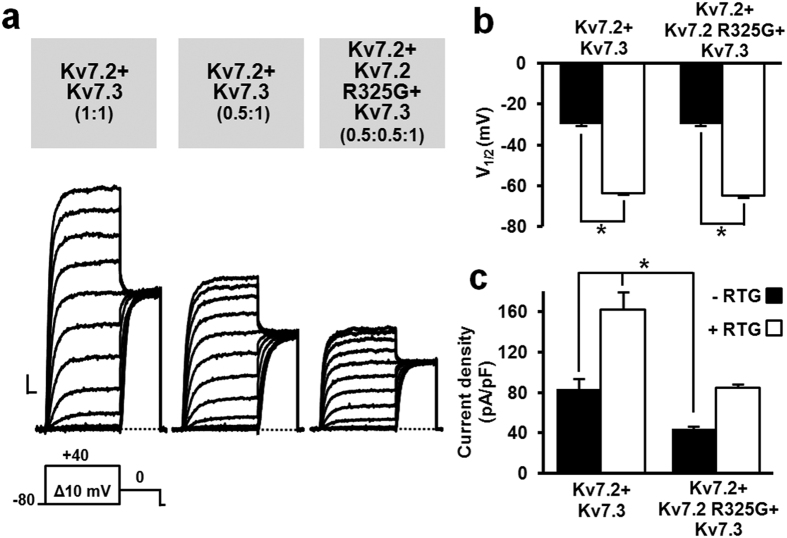

To reproduce the genetic balance of Kv7.2-EE-affected patients who carry a single mutant Kv7.2 allele, and considering that most of IKM is underlined by the heteromeric assembly of Kv7.2 and Kv7.3 subunits5, patch-clamp recordings were also performed in CHO cells co-transfected with Kv7.2 R325G together with Kv7.2 and Kv7.3 cDNAs at a 0.5:0.5:1 ratio. Macroscopic current density from Kv7.2 + Kv7.2 R325G + Kv7.3-transfected cells was smaller than that recorded from cells transfected with Kv7.2 + Kv7.3 cDNAs, both at 1:1 and 0.5:1 ratios (Fig. 3a), a result again consistent with a dominant-negative effect exerted by mutant subunits on heteromeric channel function. Current densities (in pA/pF) were 124.5 ± 4.4 (n = 25), 83.2 ± 4.1 (n = 33), and 55.5 ± 6.1 (n = 33) in Kv7.2 + Kv7.3- (1:1 ratio), Kv7.2 + Kv7.3- (0.5:1 ratio), and Kv7.2 + Kv7.2 R325G + Kv7.3- (0.5:0.5:1 ratio) expressing cells, respectively (p < 0.05 among each other). In both Kv7.2 + Kv7.3- and Kv7.2 + Kv7.2 R325G + Kv7.3-expressing cells, the Kv7 activator retigabine22 (RTG, 10 μM) shifted by a similar extent in the hyperpolarizing direction the voltage-dependence of channel activation (Fig. 3b), and potentiated maximal current density (Fig. 3c); as a result, current density from of Kv7.2 + Kv7.2 R325G + Kv7.3 heteromeric channels during retigabine exposure was identical to that of Kv7.2 + Kv7.3-expressing cells (Fig. 3c).

Figure 3. Functional characterization of heteromeric Kv7.2 + Kv7.3 channels incorporating Kv7.2 R325G subunits.

(a) Macroscopic currents recorded in response to the indicated voltage protocol (cDNA transfection ratios are in parenthesis). Current scale: 500 pA; time scale: 200 ms. (b,c) Quantification of retigabine (RTG)-induced effects on activation V½ (b) and current density at 0 mV (c). Asterisks indicate values significantly different (p < 0.05) from respective controls. For the data shown in panels b and c, the number of experiments (n) is 14 and 20 in the absence (filled bars) and in the presence of RTG (empty bars), respectively.

The Kv7.2 R325G mutation affects PIP2-dependent regulation

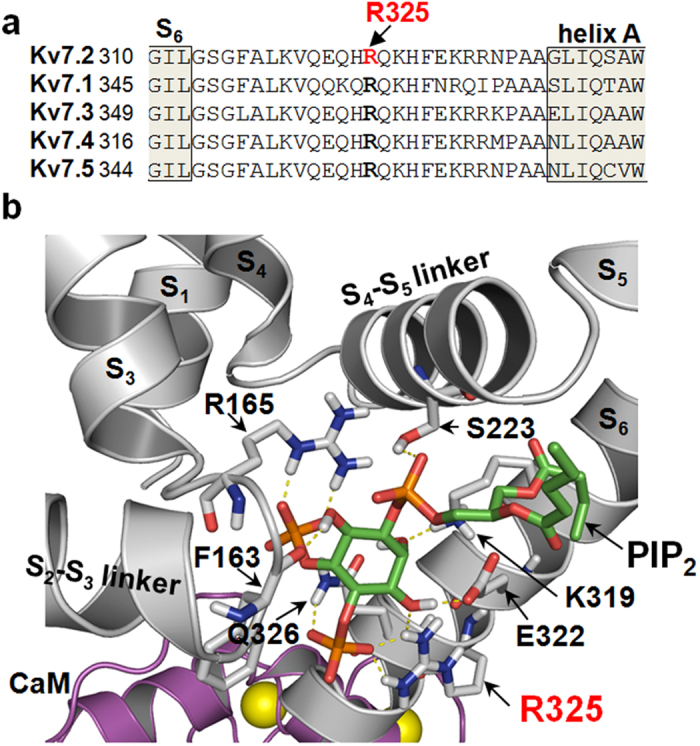

The R325 residue, highly conserved among Kv7 subunits, is located in the short linker connecting the S6 segment with the calmodulin (CaM)-binding A-helix of Kv7.2 C-terminus (Fig. 4a)23. In Kv7.1 channels, PIP2 binding to this proximal cytosolic linker is a critical determinant of open pore stability24,25; therefore, the potential contribution of the R325 residue to PIP2 binding was investigated by molecular modeling studies. In particular, we grafted a short-chain derivative of PIP2 (dioctanoyl-PIP2; diC8-PIP2), whose crystal coordinates were taken from the diC8-PIP2-bound configuration of the Kir 2.2 channel26 onto a Kv7.2 homology model built on a Kv7.1 homology model integrating the crystal structure of the Kv7.1 proximal C-terminus including the A and B helices27. Starting from this model, docking experiments were performed to find the best-scoring Kv7.2/PIP2 configuration. The data obtained revealed that, within this region, the negatively-charged PIP2 molecule is involved in an intricate network of electrostatic interactions with the side chains of residues in the S2-S3 linker (F163, R165), in the S4-S5 linker (S223), and in the pre-helix A region (K319, E322, R325, and Q326) (Fig. 4b). In particular, the R325 side chain interacts with both the 3′OH and the 4′PO42− of the PIP2 molecule; the stability of the interaction between the ζ-carbon of the Kv7.2 R325 residue and the phosphorus atom at C4′ of PIP2 was confirmed by molecular dynamics experiments over a 10 ns time range (Suppl. Fig. 1).

Figure 4. Location of the R325 residue within a PIP2-binding pocket in a Kv7.2 subunit.

(a) Partial primary sequence alignment (from the end of S6 to the beginning of the A helix) among Kv7 subunits. (b) A single PIP2 molecule docked onto a Kv7.2 subunit. Kv7.2 α-carbon traces are in grey; the PIP2 molecule is shown as sticks, and colored according to atom type (carbon, green; phosphorous, orange; oxygen, red). The CaM molecule is in purple; Ca2+ ions are in yellow. Dashed yellow lines indicate Kv7.2/PIP2 interactions occurring at distances <3 Å.

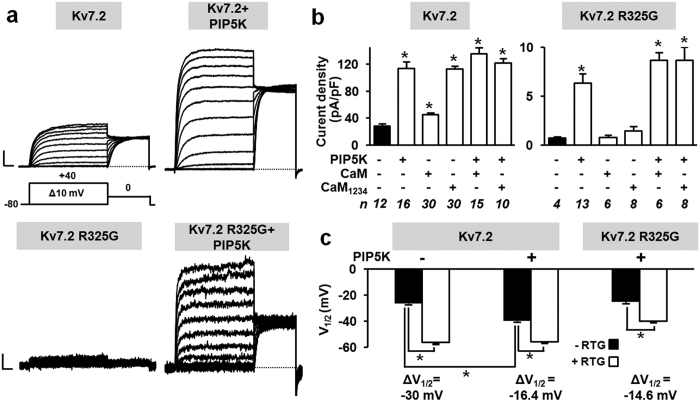

Based on these structural hints, we next investigated whether the loss-of-function of homomeric Kv7.2 R325G channels was due to a reduced sensitivity to PIP2-dependent regulation; to this aim, endogenous PIP2 levels were increased by co-expression of type 1γ PI(4)P5-kinase (PIP5K), a PIP2-synthesizing enzyme6,28,29,30. In Kv7.2 channels, PIP5K enhanced current density (Fig. 5a and b), and increased current voltage-sensitivity (Fig. 5c), as described28,31. Notably, co-expression with PIP5K led to the appearance of measurable currents in cells transfected with Kv7.2 R325G cDNA (Fig. 5a), although their size was smaller than that from Kv7.2-expressing cells (Fig. 5b). No current was instead detected when only PIP5K was expressed in CHO cells (current density was 0.7 ± 0.1 pA/pF; n = 6). Currents from PIP5K-treated Kv7.2 R325G channels were blocked by 0.3 mM TEA to a similar extent as those from Kv7.2 − or Kv7.2 + PIP5K-expressing cells; the % of current blockade was 58.3 ± 1.3 (n = 8), 57.8 ± 2.6 (n = 5), or 57.0 ± 1.0 (n = 5) in cells expressing Kv7.2, Kv7.2 + PIP5K, or Kv7.2 R325G + PIP5K channels, respectively (p > 0.05). PIP5K-recovered Kv7.2 R325G currents were also sensitive to 10 μM retigabine, showing a significant leftward shift in activation gating upon drug exposure (Fig. 5c). Notably, the voltage shift in V½ caused by retigabine (expressed as ΔV½ = V½ RTG − V½ CONTROL) in Kv7.2 R325G + PIP5K currents (−14.6 mV) was similar to that measured in Kv7.2 + PIP5K channels (−16.4 mV), both values being significantly smaller than that measured in Kv7.2 currents in the absence of PIP5K (−30.0 mV; p < 0.05) (Fig. 5c).

Figure 5. Effect of PIP5K, CaM, and CaM1234 on homomeric Kv7.2 and Kv7.2 R325G channels.

(a) Macroscopic currents recorded in response to the voltage protocol shown, in the absence (left) or presence (right) of PIP5K. Current scale: 500 pA (upper panels) or 50 pA (lower panels); time scale: 200 ms. (b) Current densities (0 mV) from cells expressing Kv7.2 or Kv7.2 R325G channels alone or in combination with PIP5K, CaM or CaM1234, as indicated. In the last row, the number of experiments (n), each from a separate cell, is indicated. (c) Effect of retigabine (RTG, 10 μM) on activation gating (V½) for the indicated channels. In all panels, asterisks indicate values significantly different (p < 0.05) from respective controls.

Co-expression with CaM or with a variant CaM unable to bind Ca2+ (CaM1234)32 has been shown to rescue Kv7.2 channels rendered non-functional by mutations in the CaM binding domains33 and to enhance Kv7.2 current density34 (Fig. 5b). Transfection with CaM or CaM1234 failed to recover currents from homomeric Kv7.2 R325G channels (Fig. 5b). Notably, CaM or CaM1234 were unable to further potentiate PIP5K-enhanced Kv7.2 or Kv7.2 R325G currents (Fig. 5b).

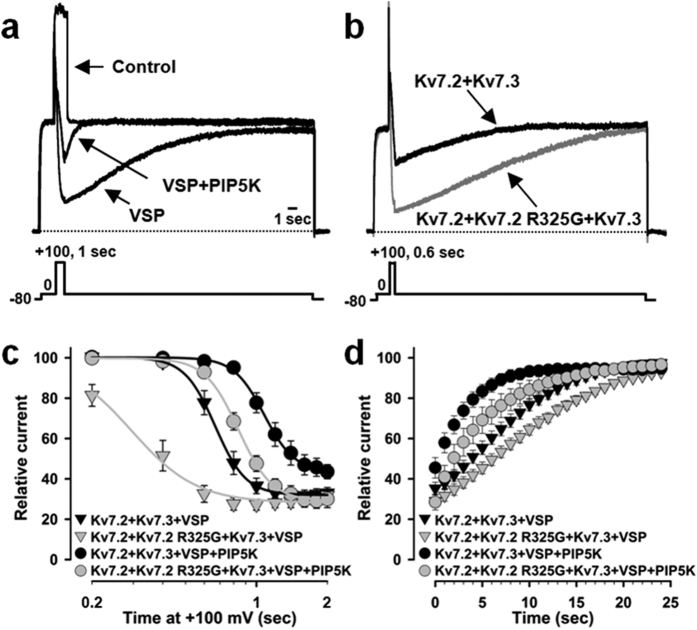

To deplete membrane PIP2 levels, a voltage-sensitive phosphatase (VSP) from zebrafish35 was used; this phosphatase is activated by strong depolarizations (≥100 mV), leading to a reduction of the plasma membrane content of PIP2 and to an inhibition of Kv7 channels4,35,36; membrane repolarization turns off the phosphatase, leading to PIP2 re-synthesis and Kv7 current recovery. In Kv7.2 + Kv7.3 channels, depolarizing pulses to +100 mV of increasing length (0.6–2 sec) time-dependently suppressed currents at 0 mV (Fig. 6a and c); the time constant of current decline at +100 mV was 0.37 ± 0.04 sec (Fig. 6d), as previously reported (0.4 sec)29. Current suppression occurring upon VSP activation was counteracted by PIP5K co-expression (Fig. 6a and c). After VSP turnoff by membrane repolarization, Kv7.2 + Kv7.3 current recovery time constant was 10.8 ± 0.9 sec; this value was decreased (3.6 ± 0.6 s; p < 0.05) in the presence of PIP5K (Fig. 6a and d). Instead, currents from Kv7.2 + Kv7.2 R325G + Kv7.3-expressing cells were more sensitive to VSP-induced inhibition, being inhibited by +100 mV pulses lasting only 0.2 sec, a time length unable to suppress Kv7.2 + Kv7.3 currents (Fig. 6c). PIP5K co-expression reduced current sensitivity to VSP also in Kv7.2 + Kv7.2 R325G + Kv7.3-expressing cells (Fig. 6c). On the other hand, after VSP switch-off, Kv7.2 + Kv7.2 R325G + Kv7.3 currents recovered more slowly than Kv7.2 + Kv7.3 currents, both in the absence and in the presence of PIP5K; in fact, the current recovery time constants of Kv7.2 + Kv7.2 R325G + Kv7.3 channels were respectively 6.7 ± 1.2 sec and 16.9 ± 1.7 sec with or without PIP5K (p < 0.05 versus the respective value in Kv7.2 + Kv7.3 channels; Fig. 6b and d). Altogether, these data provide evidence that the R325G mutation in Kv7.2 reduces PIP2 sensitivity, and that an increased cellular PIP2 levels can rescue the loss-of-function effect prompted by this mutation.

Figure 6. Effect of VSP on Kv7.2 + Kv7.3 and Kv7.2 + Kv7.2 R325G + Kv7.3 currents.

(a) Currents recorded in response to the indicated voltage protocol in cells expressing Kv7.2 + Kv7.3 (control), Kv7.2 + Kv7.3 + VSP, or Kv7.2 + Kv7.3 + VSP + PIP5K, as indicated. (b) Currents recorded in response to the indicated voltage protocol in cells expressing VSP and Kv7.2 + Kv7.3 (black trace) or Kv7.2 + Kv7.2 R325G + Kv7.3 (gray trace) channels. (c,d) Time-dependence of current decrease (c) and recovery (d) in cells co-expressing the indicated channels and VSP, in the absence or in the presence of PIP5K. VSP-dependent current inhibition (c) was expressed as the ratio between the current values recorded at 0 mV immediately after and before the +100 mV step. Recovery (d) was expressed as the ratio between currents measured every second at the end and before the +100 mV depolarizing pulse. For the data shown in panels c and d, the number of experiments (n) is 11 for Kv7.2 + Kv7.3 + VSP, 11 for Kv7.2 + Kv7.3 + VSP + PIP5K, 12 for Kv7.2 + Kv7.2 R325G + Kv7.3 + VSP, and 12 for Kv7.2 + Kv7.2 R325G + Kv7.3 + VSP + PIP5K.

The R325G mutation does not interfere with the subcellular localization of Kv7.2 subunits in rat hippocampal neurons in vitro

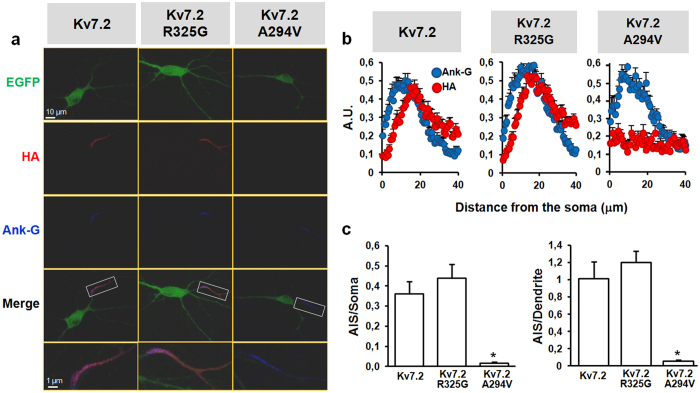

In neurons, Kv7.2 and Kv7.3 subunits are primarily expressed at the axon initial segment (AIS)37,38. Epilepsy-causing mutations in Kv7.2 may interfere with such AIS targeting39,40. To assess whether the Kv7.2 R325G mutation also prompted similar effects, wild-type or mutant Kv7.2 subunits were expressed (together with Kv7.3 subunits) by transient transfection in embryonic rat hippocampal neurons. Confocal immunofluorescence experiments in non-permeabilized neurons revealed that plasma membrane expression of Kv7.2 and Kv7.2 R325G subunits could be almost exclusively detected at the Ankyrin-G-positive AIS (Fig. 7a and b); both wild-type and mutant Kv7 subunits displayed an identical AIS expression pattern (Fig. 7c), with immunoreactivity steeply increasing within the more distal regions of the AIS (Fig. 7b), as reported for native channels in rat neocortical neurons38. By contrast, Kv7.2 subunits carrying a different EE-associated variant affecting a pore residue (A294V) failed to localize at the AIS, as previously described39 (Fig. 7).

Figure 7. AIS localization of Kv7.2 R325G subunits.

(a) Representative images of primary rat hippocampal neurons transfected with Kv7.3 and the EGFP-Kv7.2-HA-, EGFP-Kv7.2 R325G-HA-, or EGFP-Kv7.2 A294V-HA-expressing plasmids revealed by anti-HA (red; before permeabilization) or anti-ank-G (blue; after permeabilization) antibodies. In green is the EGFP fluorescence. Lower panels are magnifications of the boxed regions. (b) Quantification of the intensity (expressed as arbitrary units, A.U.) of the HA (red) and Ank-G (blue) fluorescence signals for Kv7.2 (n = 20), Kv7.2 R325G (n = 18), and Kv7.2 A294V (n = 15) subunits, measured on a 40 μm-long axonal region starting from the soma, as described in Methods. (c) Quantification of AIS/Soma and AIS/Dendrite fluorescence ratios for Kv7.2, Kv7.2 R325G, and Kv7.2 A294V subunits, calculated as described in Methods. Asterisks indicate values significantly different (p < 0.05) from respective controls.

Discussion

The primary defect of Kv7.2 R325G channels is a decreased PIP2 sensitivity

Currents carried by all five members of the Kv7 family are characterized by their absolute functional requirement for PIP23,41,42. In the present experiments, homomeric channels formed by Kv7.2 subunits carrying a mutation (R325G) found independently in four individuals affected with Kv7.2-EE15,16,17, were non functional, despite being expressed at the plasma membrane; Kv7.2 R325G subunits strongly suppressed channel function when incorporated into heteromers with Kv7.2, Kv7.3 or Kv7.3* subunits. The lack of Kv7.2 R325G homomeric channel function was partially rescued by co-expression with PIP5K, a lipid kinase which elevates PIP2 concentration in the plasma membrane to millimolar levels28,30 and reduces the ability of Gq-coupled receptors to suppress Kv7 currents36, strongly suggesting that the primary dysfunction triggered by the R325G mutation is a drastic reduction in Kv7.2 sensitivity to endogenous levels of PIP2. Consistent with this view is also the decreased potency shown by the water-soluble PIP2 analogue diC8-PIP2 in activating Kv7.2 channel carrying the R325A mutation43. Noteworthy, at variance with Kv7.2 R325G channels, homomeric Kv7.2 R325A channels, similarly to Kv7.1 channels carrying the equivalent R360A mutation both in the absence44 or in the presence45 of KCNE1 subunits, were functional, although they displayed a reduced current amplitude43,46; the α-helix-stabilizing propensity of alanine relative to glycine47 provides a plausible explanation for such relevant functional difference. Noteworthy, all Kv7.2 missense variants causing EE (including the c.973A > G leading to the R325G mutation herein investigated) are de novo substitutions of a single nucleotide7,48. Instead, a substitution of at least two nucleotides would be needed to generate the arginine-to-alanine mutation studied by Telezhkin43; thus, the R325A mutation is less likely to occur in vivo.

Kv7.2 R325G mutant subunits, when incorporated in heteromeric channels with Kv7.2 and Kv7.3 subunits at a ratio reproducing the genetic balance of epilepsy-affected patients, exerted dominant-negative effects, enhanced current suppression by PIP2 depletion with VSP, and slowed current recovery kinetics after VSP turnoff; all these results, beside confirming the molecular mechanism of the primary dysfunction, also provide strong support for a significant role of the decreased PIP2 sensitivity in severe epilepsy pathogenesis in patients carrying the R325G variant.

Mechanistic and structural consequences of the reduced PIP2 sensitivity of Kv7.2 R325G subunits

In Kv7.1 channels, PIP2 is not required for voltage-sensing domain (VSD) activation, being rather indispensable for coupling VSD activation to pore opening25. In particular, molecular dynamics experiments revealed that PIP2 stabilizes the open pore configuration by reducing the electrostatic repulsion among positively-charged residues in the S4-S5 linker, in S6, and in the proximal C-terminus immediately past S624. Unfortunately, a truncated version of the Kv7.1 channel (residues 122 to 358) was used in these experiments24; thus, the potential role of the Kv7.2 R325 residue (corresponding to R360 in Kv7.1) could not be evaluated.

In Kv7.2 channels, as herein confirmed, PIP2 up-regulates current density and facilitates voltage-dependent opening6,49; dynamic repositioning of PIP2 from the VSD to the open pore gate occurs during activation49, whereas the reverse movement correlates with channel deactivation46. Thus, a critical PIP2 binding site in Kv7.1 and Kv7.2 channels is located at the VSD-pore domain interface, where PIP2 headgroups are engaged in electrostatic interactions with basic residues in the VSD and the proximal C-terminus (including the S6 gate)3,41, thereby bridging these two domains and providing structural stabilization1. The present modeling studies confirm the critical contribution of the R325 residue to PIP2 binding in the proximal C-terminal pocket in Kv7.2 subunits; substitution of the positively-charged arginine with a smaller, non-polar glycine may significantly weaken such structural stabilization, impeding the translation of the electromechanical forces triggered by VSD displacement into pore opening. Direct crystallographic evidence for a contribution to PIP2 binding of positively-charged residues located at the interface between the transmembrane and the cytoplasmic domains has been achieved in Kir2.226, a PIP2-gated voltage-independent channel50. Finally, PIP2 binding to a similar region has been shown to stabilize the voltage sensor of Kv1 channels in a state of decreased voltage sensitivity, thus promoting functional changes opposite to those described for Kv7 channels51.

Coordinated regulation of Kv7.2 channels by PIP2 and calmodulin

The ubiquitous Ca2+-binding protein CaM exerts a critical control over Kv7.2 channel function23,52. Changes in CaM binding and functional regulation have been described for several disease-causing Kv7.2 mutations34, and co-expression with CaM has been shown to rescue Kv7.2 channels rendered non-functional by mutations in helices A or B of the CaM-binding domain33. However, CHO cells transfection with either CaM or with a mutant CaM unable to bind Ca2+ (CaM1234)32 failed to recover functional homomeric Kv7.2 R325G channels; moreover, CaM or CaM1234 did not further potentiate PIP5K-induced current enhancement in both Kv7.2 and Kv7.2 R325G channels. These results are consistent with the hypothesis that CaM-induced enhancement of Kv7.2 macroscopic current density is mostly mediated by changes in PIP2 affinity34,53,54,55. CaM also regulates polarized axonal surface expression of Kv7.2 subunits56,57; normal AIS expression of heteromeric channels carrying Kv7.2 R325G subunits was observed in cultured hippocampal neurons, suggesting that no significant mutation-induced changes in CaM binding occurs, and that changes in PIP2-dependent regulation do not impede AIS trafficking of mutant Kv7.2 subunits.

Pharmacological implications and conclusions

Retigabine is the prototype anticonvulsant acting as an activator of neuronal Kv7 channels (Kv7.2-5); retigabine causes a variable degree of hyperpolarization shift of the voltage dependence of channel activation, together with an increase in channel maximal opening probability22,58. The present observation that increasing cellular PIP2 levels with PIP5K negatively shifted the V½ of Kv7.2 channels (as previously described for Kv7.159, Kv7.249, and other heteromeric Kv7 channels31) and decreased retigabine-induced responses in both in Kv7.2 and Kv7.2 R325G channels, indicates that retigabine and PIP2 act via at least partially overlapping mechanisms to stabilize voltage-dependent pore opening; consistent with this view is the fact that PIP2-depleted Kv7.3 channels are insensitive to retigabine60.

In conclusion, the present results add severe forms of Kv7.2-related epilepsy to the growing list of channelopathies caused by changes in PIP2-dependent regulation1,59; the recent observation that Kv7 channels are critical determinants of the cortical excitability changes occurring upon dynamic regulation of PIP2 levels31, lends further support to the pathogenetic role of the proposed mechanism in individuals carrying the Kv7.2 R325G variant. Future studies will further explore the structural implications of the functional results herein presented, and define whether such specific molecular defect is associated with distinct clinical features.

Methods

Mutagenesis and heterologous expression of channel subunits

Mutations were engineered by Quick-change mutagenesis (Agilent Technologies) in a pcDNA3.1-Kv7.2 plasmid (for electrophysiological and western-blot experiments), or in a dual-tagged Enhanced Green Fluorescent Protein-Kv7.2-hemagglutinin (EGFP-Kv7.2-HA) plasmid (for immunocytochemistry experiments), as described21,34,61. In the EGFP-Kv7.2-HA chimeric constructs, in addition to an EGFP at the cytoplasmic N-terminus, an HA epitope was inserted in the extracellular loop that connects transmembrane domains S1 and S2 of Kv7.2 subunits, as previously described61,62. Protocols for wild-type and mutant cDNAs expression by transient transfection, as well as methods for CHO cell growth, have been previously described34. Total cDNA in the transfection mixture was kept constant at 4 μg, except for Western-blotting experiments (6 μg).

Cell surface biotinylation and Western-blot

Total or plasma membrane expression of Kv7.2 or Kv7.2 R325G subunits in CHO cells was investigated by surface biotinylation and western-blotting analysis, as described63. Channel subunits were identified using mouse monoclonal anti-Kv7.2 primary antibodies (clone N26A/23, dilution 1:1000; Antibodies Inc., Davis, CA), followed by horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated anti-mouse secondary antibodies (clone NA931V; dilution 1:5,000; GE Healthcare, Little Chalfont, UK). Anti-Kv7.2 monoclonal antibodies were generated using a fusion protein corresponding to amino acids 1–59 of the cytoplasmic N-terminus of human Kv7.2 subunits (accession number O43526).

Patch-clamp recordings

Macroscopic current recordings from transiently-transfected CHO cells, as well as data processing and analysis, were performed as reported11. In the experiments with TEA or retigabine (obtained from Valeant Pharmaceuticals, Aliso Viejo, CA), currents were activated by 3-s voltage ramps from −80 mV to 0/+40 mV at 0.1-Hz frequency. TEA blockade was expressed as the percentage of peak current inhibition produced by a 2-min drug application.

Molecular modeling

Homology modeling

A homology model of a Kv7.2 subunit was generated starting from a Kv7.1 homology model which integrates the crystal structure of the Kv7.1 proximal C-terminus27, using the SWISS-MODEL software64. This model was then aligned with the crystal structure of Kir2.2 channels bound to diC8-PIP226, using the Chimera matchmaker tool (https://www.cgl.ucsf.edu/chimera/docs/ContributedSoftware/matchmaker/matchmaker.html); the PIP2 crystal coordinates were then superimposed onto the Kv7.2 model. Protein preparation. To obtain a satisfactory starting structure for following studies, the Kv7.2 protein was prepared using the Schrodinger Protein Preparation Wizard65. The orientation of hydroxyl groups on S, T and Y, the side chains of N and Q residues, and the protonation state of H residues were optimized. N- and C- terminal residues were capped with acetyl and N-methyl-amide residues, respectively. The ionization and tautomeric states of H, D, E, R and K residues were adjusted to match a pH of 7.4. The structure was finally submitted to a restrained minimization (OPLS2005 force field)66 that was stopped when the root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) of heavy atoms reached 0.30 Å. Docking studies. The Schrodinger Induced Fit Docking Extended Sampling protocol67,68 was used for docking studies of PIP2 on the optimized Kv7.2 configuration. The docking space, centered on the PIP2 molecule, was defined as a 32 Å3 cubic box, while the diameter midpoint of docked ligands was restrained within a smaller, nested 22 Å3 cubic box. Residues within 10 Å of ligand poses were refined by the Prime Software (https://www.schrodinger.com/prime). Molecular Dynamics simulations. The stability of the best scoring PIP2/Kv7.2 complex was further investigated by Molecular Dynamic (MD) simulations using Desmond MD system (https://www.schrodinger.com/desmond). The simulated environment was built using the system builder utility, with the structures being neutralized by Na+ and Cl− ions, which were added to a final concentration of 0.15 M. Simulations were run in explicit solvent, using the TIP4P water model69 in a Periodic Boundary Conditions orthorhombic box. A series of minimizations and short MD simulations were carried out to relax the model system, by means of a relaxation protocol consisting of six stages: (i) minimization with the solute restrained; (ii) minimization without restraints; (iii) simulation (12 ps) in the NVT ensemble using a Berendsen thermostat (10 °K) with non-hydrogen solute atoms restrained; (iv) simulation (12 ps) in the NPT ensemble using a Berendsen thermostat (10 °K) and a Berendsen barostat (1 atm) with non-hydrogen solute atoms restrained; (v) simulation (24 ps) in the NPT ensemble using a Berendsen thermostat (300 °K) and a Berendsen barostat (1 atm) with non-hydrogen solute atoms restrained; (vi) unrestrained simulation (24 ps) in the NPT ensemble using a Berendsen thermostat (300 °K) and a Berendsen barostat (1 atm). At this point, a 10 ns long MD simulation was carried out at a temperature of 300 °K in the NPT ensemble using a Nose-Hoover chain thermostat and a Martyna-Tobias-Klein barostat (1.01325 bar). Backbone atoms were constrained during the simulation (10 kcal/mol). Trajectory analyses were performed using the Desmond simulation event analysis tool.

Neuronal cell transfection and immunocytochemistry

Hippocampal cultures were prepared from 18-day embryonic rats, as described70. At 8 days in vitro (8 DIV), neurons were co-transfected with EGFP-Kv7.2-HA (wild-type or mutant) and Kv7.3 cDNAs (ratio 1:1, total 2 μg) using Lipofectamine 2000 and immunostaining was performed at room temperature 72 hr after transfection. For surface immunostaining, neurons were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde/4% sucrose for 10′ at 37 °C, blocked with 10% normal goat serum in PBS and incubated with rabbit anti-HA antibodies (1:60; 745500; Invitrogen) diluted in 10% normal goat serum in PBS for 1 hr. For permeabilized immunostaining, neurons were incubated with mouse monoclonal anti-ankyrin-G antibodies (1:200; clone 106/36; Millipore) diluted in permeabilizing buffer (15 mM phosphate buffer pH 7.4 containing 0.1% gelatin, 0.3% Triton X-100 and 0.4 M NaCl) for 2 hr. After PBS wash, neurons were incubated simultaneously with rabbit AlexaFluor555- and mouse AlexaFluor649-conjugated secondary antibodies (1:400 and 1:300, respectively; LifeTechnologies) for 1 hr in permeabilizing buffer. Coverslips were then mounted with moviol. Confocal image acquisition was performed on a Zeiss LSM510 Meta laser scanning microscope equipped with a 63x oil immersion lens. The ImageJ software was used for image analysis. Axonal Ank-G and HA signals were measured every 0.14 μm along a 40 μm-long region starting from the soma; values (expressed as fluorescence arbitrary units of intensity) in each neuron were normalized, and averaged every 5 points to decrease signal noise. AIS/Soma and AIS/Dendrites ratios were calculated by expressing the HA fluorescence (measured in a 20–30 μm AnkG-positive area) versus the EGFP fluorescence of a 50 μm2 rectangle in the soma (AIS/Soma) or versus a 25 μm-long region of the main dendrite (AIS/Dendrite)39.

Animals

Experimental procedures were performed in accordance with the European Communities Council Directive (86/809/EEC) on the care and use of animals and the UK Animals (Scientific Procedures) Act 1986, and were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of the CNR Institute of Neuroscience.

Statistics

Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. Each data point shown in figures or in the text is the Mean ± SEM of at least 4 determinations, each performed in a single cell or in a separate experiment. Statistically significant differences were evaluated with the Student’s t-test or with the ANOVA followed by the Student-Newman-Keuls test, with the threshold set at p < 0.05.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Soldovieri, M. V. et al. Early-onset epileptic encephalopathy caused by a reduced sensitivity of Kv7.2 potassium channels to phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate. Sci. Rep. 6, 38167; doi: 10.1038/srep38167 (2016).

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The Authors are deeply grateful to: Dr. Thomas J. Jentsch, Leibniz-Institut für Molekulare Pharmakologie (FMP), Berlin (Germany) for Kv7.2 and Kv7.3 cDNAs; Dr. Alvaro Villarroel, UPV-CSIC, Leioa (ES) for PIP(4)5 K lγ and Kv7.3 A315T cDNAs; Dr. B. Attali Tel Aviv University (IL) for the coordinates of the Kv7.1/CaM homology model; Dr. Yasushi Okamura, Osaka University, Suita, Osaka (JP) for Dr-VSP-IRES-GFP cDNA.

Footnotes

Author Contributions M.V.S., L.M., A.A., and A.M. performed mutagenesis and protein biochemistry experiments; P.A., I.M., F.M. performed electrophysiological experiments; P.A. and N.I. performed molecular modeling studies; M.D.M., E.M. and M.P. performed neuronal transfection and imaging experiments; M.T. conceived the project and coordinated the group. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

References

- Zaydman M. A. & Cui J. PIP2 regulation of KCNQ channels: biophysical and molecular mechanisms for lipid modulation of voltage-dependent gating. Front. Physiol. 5, 195 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delmas P. & Brown D. A. Pathways modulating neural KCNQ/M (Kv7) potassium channels. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 6, 850–862 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H. et al. PIP(2) activates KCNQ channels, and its hydrolysis underlies receptor-mediated inhibition of M currents. Neuron 37, 963–975 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kruse M., Hammond G. R. & Hille B. Regulation of voltage-gated potassium channels by PI(4,5)P2. J. Gen. Physiol. 140, 189–205 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soldovieri M. V., Miceli F. & Taglialatela M. Driving with no brakes: molecular pathophysiology of Kv7 potassium channels. Physiology 26, 365–376 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y., Gamper N., Hilgemann D. W. & Shapiro M. S. Regulation of Kv7 (KCNQ) K+ channel open probability by phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate. J. Neurosci. 25, 9825–9835 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miceli F. et al. KCNQ2-Related Disorders. In Pagon RA, Adam MP, Ardinger HH, Wallace SE, Amemiya A, Bean LJH, Bird TD, Ledbetter N, Mefford HC, Smith RJH, Stephens K, editors. GeneReviews® [Internet]. Seattle (WA): University of Washington, Seattle; 1993–2016. 2010 Apr 27 [updated 2016 Mar 31]. Accessed on October 28, 2016 at https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK32534/.

- Weckhuysen S. et al. KCNQ2 encephalopathy: emerging phenotype of a neonatal epileptic encephalopathy. Ann. Neurol. 71, 15–25 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kato M. et al. Clinical spectrum of early onset epileptic encephalopathies caused by KCNQ2 mutation. Epilepsia 54, 1282–1287 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saitsu H. et al. Whole exome sequencing identifies KCNQ2 mutations in Ohtahara syndrome. Ann. Neurol. 72, 298–300 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miceli F. et al. Genotype-phenotype correlations in neonatal epilepsies caused by mutations in the voltage sensor of K(v)7.2 potassium channel subunits. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 110, 4386–4391 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orhan G. et al. Dominant-negative effects of KCNQ2 mutations are associated with epileptic encephalopathy. Ann. Neurol. 75, 382–394 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devaux J. et al. A Kv7.2 mutation associated with early onset epileptic encephalopathy with suppression-burst enhances Kv7/M channel activity. Epilepsia 57, e87–93 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miceli F. et al. Early-onset epileptic encephalopathy caused by gain-of-function mutations in the voltage sensor of Kv7.2 and Kv7.3 potassium channel subunits. J. Neurosci. 35, 3782–3793 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Numis A. L. et al. KCNQ2 encephalopathy: delineation of the electroclinical phenotype and treatment response. Neurology 82, 368–370 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weckhuysen S. et al. Extending the KCNQ2 encephalopathy spectrum: clinical and neuroimaging findings in 17 patients. Neurology 81, 1697–1703 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marchese G., Rizzo F., Guacci A., Weisz A. & Coppola G. Kleefstra-variant syndrome with heterozygous mutations in EHMT1 and KCNQ2 genes: a case report. Neurol. Sci. 37, 829–831 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaika O., Hernandez C. C., Bal M., Tolstykh G. P. & Shapiro M. S. Determinants within the turret and pore-loop domains of KCNQ3 K+ channels governing functional activity. Biophys. J. 95, 5121–5137 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gómez-Posada J. C. et al. A pore residue of the KCNQ3 potassium M-channel subunit controls surface expression. J. Neurosci. 30, 9316–9323 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hadley J. K. et al. Differential tetraethylammonium sensitivity of KCNQ1-4 potassium channels. Br. J. Pharmacol. 129, 413–415 (2000). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castaldo P. et al. Benign familial neonatal convulsions caused by altered gating of KCNQ2/KCNQ3 potassium channels. J. Neurosci. 22, RC199 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miceli F., Soldovieri M. V., Martire M. & Taglialatela M. Molecular pharmacology and therapeutic potential of neuronal Kv7-modulating drugs. Curr. Opin. Pharmacol. 8, 65–74 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villarroel A. et al. The ever changing moods of calmodulin: how structural plasticity entails transductional adaptability. J. Mol. Biol. 426, 2717–2735 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasimova M. A., Zaydman M. A., Cui J. & Tarek M. PIP(2)-dependent coupling is prominent in Kv7.1 due to weakened interactions between S4-S5 and S6. Sci. Rep. 5, 7474 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaydman M. A. et al. Kv7.1 ion channels require a lipid to couple voltage sensing to pore opening. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 110, 13180–13185 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen S. B., Tao X. & MacKinnon R. Structural basis of PIP2 activation of the classical inward rectifier K+ channel Kir2.2. Nature 477, 495–498 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sachyani D. et al. Structural basis of a Kv7.1 potassium channel gating module: studies of the intracellular C-terminal domain in complex with calmodulin. Structure 22, 1582–1594 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winks J. S. et al. Relationship between membrane phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate and receptor-mediated inhibition of native neuronal M channels. J. Neurosci. 25, 3400–3413 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falkenburger B. H., Jensen J. B. & Hille B. Kinetics of PIP2 metabolism and KCNQ2/3 channel regulation studied with a voltage-sensitive phosphatase in living cells. J. Gen. Physiol. 135, 99–114 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wenk M. R. et al. PIP kinase Igamma is the major PI(4,5)P(2) synthesizing enzyme at the synapse. Neuron 32, 79–88 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim K. S., Duignan K. M., Hawryluk J. M., Soh H. & Tzingounis A. V. The Voltage Activation of Cortical KCNQ Channels Depends on Global PIP2 Levels. Biophys. J. 110, 1089–1098 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gamper N. & Shapiro M. S. Calmodulin mediates Ca2+-dependent modulation of M-type K+ channels. J. Gen. Physiol. 122, 17–31 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alaimo A. et al. Cooperativity between calmodulin-binding sites in Kv7.2 channels. J. Cell. Sci. 126, 244–253 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ambrosino P. et al. Epilepsy-causing mutations in Kv7.2 C-terminus affect binding and functional modulation by calmodulin. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1852, 1856–1866 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hossain M. I. et al. Enzyme domain affects the movement of the voltage sensor in ascidian and zebrafish voltage-sensing phosphatases. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 18248–18259 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suh B. C. & Hille B. Regulation of KCNQ channels by manipulation of phosphoinositides. J. Physiol. 582, 911–916 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan Z. et al. A common ankyrin-G-based mechanism retains KCNQ and NaV channels at electrically active domains of the axon. J. Neurosci. 26, 2599–2613 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Battefeld A., Tran B. T., Gavrilis J., Cooper E. C. & Kole M. H. Heteromeric Kv7.2/7.3 channels differentially regulate action potential initiation and conduction in neocortical myelinated axons. J. Neurosci. 34, 3719–3732 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abidi A. et al. A recurrent KCNQ2 pore mutation causing early onset epileptic encephalopathy has a moderate effect on M current but alters subcellular localization of Kv7 channels. Neurobiol. Dis. 80, 80–92 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung H. J., Jan Y. N. & Jan L. Y. Polarized axonal surface expression of neuronal KCNQ channels is mediated by multiple signals in the KCNQ2 and KCNQ3 C-terminal domains. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 103, 8870–8875 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loussouarn G. et al. Phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate, PIP2, controls KCNQ1/KCNE1 voltage-gated potassium channels: a functional homology between voltage-gated and inward rectifier K+ channels. EMBO J. 22, 5412–5421 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suh B. C. & Hille B. Recovery from muscarinic modulation of M current channels requires phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate synthesis. Neuron 35, 507–520 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Telezhkin V., Thomas A. M., Harmer S. C., Tinker A. & Brown D. A. A basic residue in the proximal C-terminus is necessary for efficient activation of the M-channel subunit Kv7.2 by PI(4,5)P(2). Pflugers Arch. 465, 945–953 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boulet I. R., Labro A. J., Raes A. L. & Snyders D. J. Role of the S6 C-terminus in KCNQ1 channel gating. J. Physiol. 585, 325–337 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas A. M., Harmer S. C., Khambra T. & Tinker A. Characterization of a binding site for anionic phospholipids on KCNQ1. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 2088–2100 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L. et al. Migration of PIP2 lipids on voltage-gated potassium channel surface influences channel deactivation. Sci. Rep. 5, 15079 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott K. A., Alonso D. O., Sato S., Fersht A. R. & Daggett V. Conformational entropy of alanine versus glycine in protein denatured states. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 104, 2661–2666 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millichap J. J. et al. KCNQ2 encephalopathy: Features, mutational hot spots, and ezogabine treatment of 11 patients. Neurol. Genet. 2, e96 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Q. et al. Dynamic PIP2 interactions with voltage sensor elements contribute to KCNQ2 channel gating. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 110, 20093–20098 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang C. L., Feng S. & Hilgemann D. W. Direct activation of inward rectifier potassium channels by PIP2 and its stabilization by Gbetagamma. Nature 391, 803–806 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez-Menchaca A. A. et al. PIP2 controls voltage-sensor movement and pore opening of Kv channels through the S4-S5 linker. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 109, E2399–2408 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shahidullah M., Santarelli L. C., Wen H. & Levitan I. B. Expression of a calmodulin-binding KCNQ2 potassium channel fragment modulates neuronal M-current and membrane excitability. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 102, 16454–16459 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alberdi A. et al. Uncoupling PIP2-calmodulin regulation of Kv7.2 channels by an assembly destabilizing epileptogenic mutation. J. Cell. Sci. 128, 4014–4023 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosenko A. & Hoshi N. A change in configuration of the calmodulin-KCNQ channel complex underlies Ca2+-dependent modulation of KCNQ channel activity. PLoS ONE 8, e82290 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosenko A. et al. Coordinated signal integration at the M-type potassium channel upon muscarinic stimulation. EMBO J. 31, 3147–3156 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavaretta J. P. et al. Polarized axonal surface expression of neuronal KCNQ potassium channels is regulated by calmodulin interaction with KCNQ2 subunit. PloS ONE 9, e103655 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu W. & Devaux J. J. Calmodulin orchestrates the heteromeric assembly and the trafficking of KCNQ2/3 (Kv7.2/3) channels in neurons. Mol. Cell. Neurosci. 58, 40–52 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tatulian L., Delmas P., Abogadie F. C. & Brown D. A. Activation of expressed KCNQ potassium currents and native neuronal M-type potassium currents by the anti-convulsant drug retigabine. J. Neurosci. 21, 5535–5545 (2001). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Logothetis D. E., Petrou V. I., Adney S. K. & Mahajan R. Channelopathies linked to plasma membrane phosphoinositides. Pflugers Arch. 460, 321–341 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou P. et al. Phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate alters pharmacological selectivity for epilepsy-causing KCNQ potassium channels. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 110, 8726–8731 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soldovieri M. V. et al. Decreased subunit stability as a novel mechanism for potassium current impairment by a KCNQ2 C terminus mutation causing benign familial neonatal convulsions. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 418–428 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwake M., Pusch M., Kharkovets T. & Jentsch T. J. Surface expression and single channel properties of KCNQ2/KCNQ3, M-type K+ channels involved in epilepsy. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 13343–13348 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soldovieri M. V. et al. Novel KCNQ2 and KCNQ3 mutations in a large cohort of families with benign neonatal epilepsy: first evidence for an altered channel regulation by syntaxin-1A. Hum. Mutat. 35, 356–367 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwede T., Kopp J., Guex N. & Peitsch M. C. SWISS-MODEL: An automated protein homology-modeling server. Nucleic Acids Res. 31, 3381–3385 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madhavi Sastry G., Adzhigirey M., Day T., Annabhimoju R. & Sherman W. Protein and ligand preparation: Parameters, protocols, and influence on virtual screening enrichments. J. Comput. Aided Mol. Des. 27, 221–234 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jorgensen W. L., Maxwell D. S. & Tirado-Rives J. Development and testing of the OPLS all-atom force field on conformational energetics and properties of organic liquids. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 118, 11225–11236 (1996). [Google Scholar]

- Sherman W., Day T., Jacobson M. P., Friesner R. A. & Farid R. Novel Procedure for Modeling Ligand/Receptor Induced Fit Effects. J. Med. Chem. 49, 534–553 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherman W., Beard H. S. & Farid R. Use of an Induced Fit Receptor Structure in Virtual Screening. Chem. Biol. Drug Des. 67, 83–84 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jorgensen W. L., Chandrasekhar J., Madura J. D., Impey R. W. & Klein M. L. Comparison of simple potential functions for simulating liquid water. J. Chem. Phys. 79, 926–935 (1983). [Google Scholar]

- Brewer G. J., Torricelli J. R., Evege E. K. & Price P. J. Optimized survival of hippocampal neurons in B27-supplemented Neurobasal, a new serum-free medium combination. J. Neurosci. Res. 35, 567–576 (1993). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.