Abstract

The algorithms based on common neighbors metric to predict missing links in complex networks are very popular, but most of these algorithms do not account for missing links between nodes with no common neighbors. It is not accurate enough to reconstruct networks by using these methods in some cases especially when between nodes have less common neighbors. We proposed in this paper a new algorithm based on common neighbors and distance to improve accuracy of link prediction. Our proposed algorithm makes remarkable effect in predicting the missing links between nodes with no common neighbors and performs better than most existing currently used methods for a variety of real-world networks without increasing complexity.

As an important branch of network data analysis, predicting missing links in complex network has attracted many researchers’ widespread attentions not only because data collected from network platforms is incomplete1,2, but also it is helpful to understand evolution of networks3,4,5, and predict future conflict and individual preferences6,7. In principle many evolution models correspond to a link prediction approach. Thus, link prediction can be used in revealing hidden information and evaluating the performance of distinct models. Moreover, link prediction has been applied to health care and communication field to identify abnormal cases8,9.

The main work in link prediction is to estimate the missing link between two nodes based on current links and interactions in networks10. Link prediction discusses missing links and spurious links. In this paper, we focus on predicting missing links. Generally, between nodes with very high likelihood scores are considered to be highly likely to have missing links. In the past few years, many prediction methods based on topological structure of networks have been proposed related to local paths, common neighbors and random walk10,11,12,13. In social networks two individuals who have more common friends are very likely to be friends in future. Furthermore, community methods, hierarchical models and probabilistic methods are also used for link prediction14,15,16,17,18,19. Recently, information theory and spectral method of adjacency matrix have been adopted to find missing links20,21,22.

The prediction methods based on common neighbors metric10 are very popular due to its simplicity. But with single common neighbors metric is not accurate enough to reveal the similarities between nodes and reconstruct properly networks, especially there are less common neighbors between nodes in sparse networks. A part of missing links could not be predicted because there are no common neighbors between them, but they often play a key role to connect different communities, and affect network properties, such as betweenness centrality, average distance, congestion and spreading ability. Therefore, it is important to propose an algorithm to predict missing links between nodes with no common neighbors.

A lot of real-world networks indicate high clustering properties. There are a large number of short loops. It is a good idea to exploit this properties to improve accuracy of link prediction. In this paper, we separate link prediction into two parts: predicted links that generate loops of length 3 and predicted links that generate short loops of length more than 3. So common neighbors and distance metric are adopted to predict these loops. The key question is to estimate the proportion of two parts. A new method is proposed to achieve it. By estimating the proportion of missing links between nodes with no common neighbors in total missing links, our algorithm makes remarkable effect to predict the missing links between nodes with no common neighbors, and improve the accuracy of link prediction. The experimental results show that it can obtain significantly better prediction accuracy for a variety of real-world networks than other methods.

Results

Data sets Description

The test data sets of real-world networks in this paper are:

Karate: The test data of Karate club network was collected by Zachary, which indicates the interactions of 34 members of a university Karate club23.

Dolphins: It is an animal relationship network studied by Lusseau et al. with 62 bottlenose dolphins living in Doubtful Sound of New Zealand24.

Polbook: This is a network of books about US politics published around the time of the 2004 presidential election and sold by the online bookseller Amazon.com. The network was compiled by Krebs and is unpublished, but can be found on Krebs’ website (see http://www.orgnet.com).

Word: The data is a network of common adjective and noun adjacencies for the novel “David Copperfield” by Charles Dickens, as described by Newman25.

Neural: This data represents the neural network of C. Elegans. The nodes in the original data are not consecutively numbered, so they have been renumbered to be consecutive26.

Circuit: Electronic circuits can be viewed as networks in which nodes are electronic components (like capacitors, diodes, etc.) and connections are wires. Our network maps one of the benchmark circuits of the so-called ISCAS'89 set (see data set from http://www.weizmann.ac.il/mcb/UriAlon/)27.

Email: This is a network of e-mail interchanges between members of the Universitat Rovira i Virgili (Tarragona) (see data set from http://deim.urv.cat/~alexandre.arenas/data/welcome.htm)28.

Power: This is an undirected, unweighted network representing the topology of the Western States Power Grid of the United States26.

The data sets (1–5) and (8) can be downloaded from Mark Newman’s network data sets: http://www-personal.umich.edu/~mejn/netdata/. The parameters of networks about the number of nodes N, the number of links m, average degree 〈k〉, average distance 〈d〉, assortativity coefficient r and degree heterogeneity H are listed in Table 1.

Table 1. Illustration of properties of networks.

| Networks | N | m | c | cn | cr |  |

〈d〉 | 〈k〉 | r | H |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Karate | 34 | 78 | 0.571 | 0.859 | 0.793 | 0.771 | 2.408 | 4.588 | −0.476 | 1.693 |

| Dolphins | 62 | 159 | 0.259 | 0.761 | 0.710 | 0.715 | 3.357 | 5.129 | −0.044 | 1.327 |

| Polbook | 105 | 441 | 0.488 | 0.959 | 0.937 | 0.927 | 3.079 | 8.400 | −0.128 | 1.421 |

| Word | 112 | 425 | 0.173 | 0.725 | 0.694 | 0.672 | 2.536 | 7.589 | −0.129 | 1.815 |

| Neural | 297 | 2148 | 0.292 | 0.945 | 0.913 | 0.916 | 2.455 | 14.465 | −0.163 | 1.801 |

| Circuit | 512 | 819 | 0.055 | 0.137 | 0.118 | 0.115 | 6.858 | 3.199 | −0.030 | 1.259 |

| 1133 | 5451 | 0.220 | 0.776 | 0.734 | 0.733 | 3.606 | 9.622 | 0.078 | 1.942 | |

| Power | 4941 | 6594 | 0.080 | 0.208 | 0.179 | 0.176 | 18.989 | 2.669 | 0.003 | 1.450 |

Parameters are measured in original networks G except  and cr in G′ = G − EP, where

and cr in G′ = G − EP, where  .

.

cn: CN coefficient;  ; 〈d〉: average distance; 〈k〉: average degree; c: clustering coefficient; r: assortativity coefficient (see Methods section);

; 〈d〉: average distance; 〈k〉: average degree; c: clustering coefficient; r: assortativity coefficient (see Methods section);  : degree heterogeneity. The values of cr and

: degree heterogeneity. The values of cr and  are the average of 20 realizations to randomly remove EP for each network every time.

are the average of 20 realizations to randomly remove EP for each network every time.

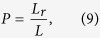

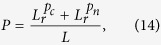

Link prediction method

Two metrics are used to evaluate the accuracy of link prediction methods: AUC (areas under the receiver operating characteristic curve)29 and Precision30. Given an unweighted and undirected network G = (V, E) with vertex set V = {v1, v2, …, vN} and the observed link set E, where the size of E is m. The self-loops and multiple links are not allowed. E are randomly divided into two disjoint subsets: the probe set EP and the training set ET. EP is used for testing and is viewed as unknown information. ET is viewed as known information. A good prediction method should have high AUC value according to the definition of AUC, i.e. the links in probe set have higher scores than non-existing links. Precision is computed as the fraction of correct predicted links in the top-L ranking lists, where L is the total number of missing links (L = |EP|) (see Methods section).

Now G′ = (V, ET) is known, so basic idea in reconstructing network is to add top-L predicted links to G′ to obtain G* = (V, E*) so that G* is as close as possible to G. Therefore, a good predicted method can provide trusted prediction in the evolution of networks.

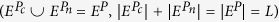

In this paper we separate the probe set EP into two subsets:  and

and  , which denote link set between nodes with common neighbors and link set between nodes with no common neighbors in G′, respectively, that is,

, which denote link set between nodes with common neighbors and link set between nodes with no common neighbors in G′, respectively, that is,

|

|

where Γ(i) denotes the set of neighbors of node i. Let  is the proportion of

is the proportion of  in EP. The test will be performed with EP accounting for 10% of the observed link set E, and randomly selects EP to remove every time. The results of cr are the average of 20 realizations for each network (see Table 1).

in EP. The test will be performed with EP accounting for 10% of the observed link set E, and randomly selects EP to remove every time. The results of cr are the average of 20 realizations for each network (see Table 1).

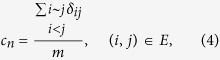

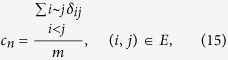

But for a practical observed network G, link prediction methods are used to predict the possible links in the future (network evolution), we only knew roughly the total number of missing links L = |EP|, which is consistent with other methods in literatures. Therefore, it is key to estimate the proportion of  in EP in order to improve prediction accuracy under the Precision metric. We define

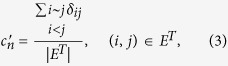

in EP in order to improve prediction accuracy under the Precision metric. We define  to evaluate strength of links between nodes with common neighbors in G′ = (V, ET) (The corresponding definition is cn for G, and cn is labeled as “CN coefficient” in this paper), which is defined as the fraction of links between nodes with common neighbors in ET, that is,

to evaluate strength of links between nodes with common neighbors in G′ = (V, ET) (The corresponding definition is cn for G, and cn is labeled as “CN coefficient” in this paper), which is defined as the fraction of links between nodes with common neighbors in ET, that is,

|

|

where δij = 1, if Γ(i) ∩ Γ(j) ≠ ∅, 0 otherwise, and i ~ j denotes node i and j to be adjacent. The results of  and cn are listed in Table 1. Between

and cn are listed in Table 1. Between  and cr has low RMSE (root-mean-square error) and high positive correlation measured by Pearson correlation coefficient (CC). Furthermore, between cn, cr and clustering coefficient c (defined in Methods section) also indicate high positive correlation (see Table 2). Therefore, it is feasible to use

and cr has low RMSE (root-mean-square error) and high positive correlation measured by Pearson correlation coefficient (CC). Furthermore, between cn, cr and clustering coefficient c (defined in Methods section) also indicate high positive correlation (see Table 2). Therefore, it is feasible to use  instead of cr to estimate the proportion of

instead of cr to estimate the proportion of  in EP. Thus,

in EP. Thus,  in G′.

in G′.

Table 2. Root mean square error (EMSE) and Pearson correlation coefficient (CC) between c

n

,

, c

r

and clustering coefficient c in the 8 networks.

, c

r

and clustering coefficient c in the 8 networks.

| cr |

|

cn | cr | c | cn | cr |

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EMSE | 0.012 | CC | 0.999 | 0.777 | 0.999 | ||||

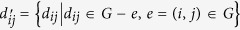

There are large number of short loops in real-world networks. In order to illustrate the fact, the distribution of “pseudo-distance” will be given. Generally, the distance dij of two nodes i, j is defined as the length of the shortest paths between them. dij is infinite if no such path exist. “pseudo-distance”  is defined to be the length of the shortest paths between i and j in network G − e for a link e = (i, j), that is,

is defined to be the length of the shortest paths between i and j in network G − e for a link e = (i, j), that is,  . Let

. Let

|

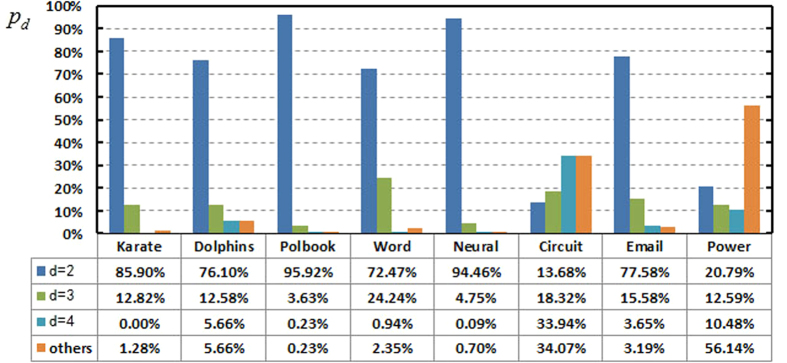

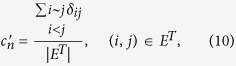

which denotes the fraction of links where pseudo-distance is d in total links. In a way it can reveal distance distribution of missing links in G′. Figure 1 describes the distribution pd for d = 2, 3, 4 and the rest in 8 real-world networks, where the distribution of most networks are concentrated in d = 2, 3, 4. It is obvious that p2 = cn.

Figure 1. The distributions pd for d = 2, 3, 4 and the rest in 8 real-world networks.

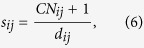

On the other hand, these missing links for d ≠ 2 (links between nodes with no common neighbors) play a pivotal role in determining the structure properties of networks. But they are neglected by mostly current existing link prediction methods. A single method based on common neighbors could not predict these important missing links. So we propose in this paper a new prediction method based on common neighbors and distance. The score of likelihood is defined as follows:

|

where CNij = |Γ(i) ∩ Γ(j)| represents the number of common neighbors for node i and j. The above equation equals to:

|

Since between two nodes is more likely to possess a link if they have more common neighbors, it is not difficult to find that it is equivalent to the CN method10 for these pairs of nodes with common neighbors, but distance plays an important role in predicting missing links between nodes with no common neighbors because high score is obtained by short distance. Our method is summarized in Methods section.

Experiment

In Table 3, the predicted results of different methods under the AUC metric are listed in 8 real-world networks. Our method is compared with prediction methods based on common neighbors10: CN method, Sal (Salton Index), Jaccard Index, Sen (Sϕrensen Index), HPI (Hub Promoted Index), HDI (Hub Depressed Index), LHN (Leicht-Holme-Newman Index), AA (Adamic-Adar Index) and RA method (Resource Allocation Index). For computation in these methods can be seen in Table 4. The results are the average of 20 realizations for each network under 10% and 20% probe set. Probe set will be randomly removed every time. The highest value of AUC for each network is labeled in boldface. The accuracy of our method outperforms other methods except Neural network, because this network possesses high cn, high degree heterogeneity and negative assortativity. RA index and AA index have similar form, and thus they have nearly same scores. Circuit and Power network have low cn, and thus for most methods assign low AUC scores which are approximately 0.5 for this two networks. Conversely, our method shows better results due to distance.

Table 3. The AUC of different methods under 10% and 20% probe set in 8 networks.

|

Methods | Karate | Dolphins | Polbook | Word | Neural | Circuit | Power | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10% | RA | 0.721(78) | 0.775(71) | 0.899(25) | 0.675(38) | 0.868(12) | 0.552(13) | 0.848(11) | 0.586(5) |

| AA | 0.711(75) | 0.776(71) | 0.898(25) | 0.677(41) | 0.863(12) | 0.552(13) | 0.849(11) | 0.586(5) | |

| Jaccard | 0.591(63) | 0.770(67) | 0.878(25) | 0.621(36) | 0.792(11) | 0.552(13) | 0.845(11) | 0.586(5) | |

| LHN | 0.578(74) | 0.751(62) | 0.850(26) | 0.584(31) | 0.727(10) | 0.552(13) | 0.838(10) | 0.586(5) | |

| HDI | 0.581(64) | 0.772(69) | 0.865(23) | 0.620(35) | 0.781(12) | 0.552(13) | 0.844(11) | 0.586(5) | |

| HPI | 0.696(79) | 0.754(63) | 0.895(26) | 0.637(37) | 0.808(12) | 0.552(13) | 0.841(10) | 0.586(5) | |

| Sen | 0.591(63) | 0.770(67) | 0.878(25) | 0.621(36) | 0.792(11) | 0.552(13) | 0.845(11) | 0.586(5) | |

| Sal | 0.617(69) | 0.765(66) | 0.886(25) | 0.624(36) | 0.800(10) | 0.552(13) | 0.844(11) | 0.586(5) | |

| CN | 0.679(72) | 0.772(70) | 0.889(26) | 0.678(42) | 0.844(13) | 0.552(13) | 0.847(11) | 0.586(5) | |

| Our | 0.725(88) | 0.790(60) | 0.901(14) | 0.693(46) | 0.844(10) | 0.742(23) | 0.880(9) | 0.659(10) | |

| 20% | RA | 0.686(60) | 0.753(39) | 0.883(18) | 0.658(22) | 0.845(10) | 0.541(10) | 0.822(6) | 0.571(2) |

| AA | 0.683(59) | 0.754(39) | 0.881(18) | 0.660(22) | 0.842(10) | 0.541(10) | 0.822(6) | 0.571(2) | |

| Jaccard | 0.597(41) | 0.749(37) | 0.856(17) | 0.609(19) | 0.773(9) | 0.541(10) | 0.819(6) | 0.571(2) | |

| LHN | 0.588(50) | 0.737(36) | 0.829(19) | 0.583(18) | 0.724(8) | 0.541(10) | 0.813(6) | 0.571(2) | |

| HDI | 0.590(37) | 0.751(38) | 0.847(16) | 0.609(19) | 0.765(9) | 0.541(10) | 0.819(6) | 0.571(2) | |

| HPI | 0.662(63) | 0.738(35) | 0.868(20) | 0.623(21) | 0.789(10) | 0.541(10) | 0.816(6) | 0.571(2) | |

| Sen | 0.597(41) | 0.749(37) | 0.856(17) | 0.609(19) | 0.773(9) | 0.541(10) | 0.819(6) | 0.571(2) | |

| Sal | 0.613(47) | 0.746(36) | 0.862(18) | 0.611(20) | 0.780(10) | 0.541(10) | 0.818(6) | 0.571(2) | |

| CN | 0.662(52) | 0.740(37) | 0.858(17) | 0.655(21) | 0.824(10) | 0.540(10) | 0.821(6) | 0.571(2) | |

| Our | 0.678(71) | 0.767(59) | 0.885(17) | 0.672(20) | 0.828(6) | 0.698(23) | 0.871(6) | 0.593(11) |

The results are the average of 20 realizations for each network, and probe set EP will be randomly removed every time. The highest value for each network is labeled in boldface. The numbers in the brackets denote the standard deviations. For example, 0.721(78) denotes that the AUC value is 0.721 and the standard deviation is 78 × 10−4.

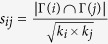

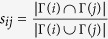

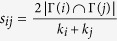

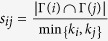

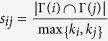

Table 4. The computation of link prediction methods.

| CN | sij = |Γ(i) ∩ Γ(j)| | Sal (Salton) |  |

| Jaccard |  |

Sen (Sϕrensen) |  |

| HPI (Hub Promoted) |  |

HDI (Hub Depressed) |  |

| LHN (Leicht-Holme-Newman) |  |

AA (Adamic-Adar) |  |

| RA (Resource Allocation) |  |

||

| PA (Preferential Attachment) | sij = ki × kj | LP (Local Path) | sLP = A2 + βA3 |

ki is the degree of node i. PA method and LP method do not directly relate to common neighbors, but based on local information, where A is adjacency matrix and β = 0.01.

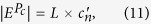

In most algorithms, AUC shows slightly downward trend when the proportion of EP in E increases from 10% to 20% (see Fig. 2). The main reason is that the decrease of training set ET will result in the number of pairs of nodes with common neighbors becoming small, which increases the difficulty of link prediction.

Figure 2.

The changes of AUC when  increases from 10% to 20% in 8 real-world networks (a–h).

increases from 10% to 20% in 8 real-world networks (a–h).

On the other hand, the prediction results under the Precision metric are given in Table 5. Similarly, our method noticeably outperforms other methods except Polbook and Power network in  = 20%, because Power network has low

= 20%, because Power network has low  (or cn), high m and large average distance 〈d〉 = 18.989. According to Eq. (12) in Power network our method need predict too much missing links with large distance (i.e. the presence of few short loops with length more than 3), which result in low prediction accuracy than CN method. It should be mentioned that Precision indicates the opposite changing trend compared with AUC except Circuit and Power network (They are low

(or cn), high m and large average distance 〈d〉 = 18.989. According to Eq. (12) in Power network our method need predict too much missing links with large distance (i.e. the presence of few short loops with length more than 3), which result in low prediction accuracy than CN method. It should be mentioned that Precision indicates the opposite changing trend compared with AUC except Circuit and Power network (They are low  ) with the increase of EP (see Fig. 3).

) with the increase of EP (see Fig. 3).

Table 5. The Precision of different methods under 10% and 20% probe set in 8 networks.

|

Methods | Karate | Dolphins | Polbook | Word | Neural | Circuit | Power | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10% | RA | 0.154(109) | 0.123(73) | 0.185(55) | 0.054(27) | 0.103(17) | 0.012(9) | 0.143(12) | 0.028(9) |

| AA | 0.132(125) | 0.128(81) | 0.172(53) | 0.068(39) | 0.105(20) | 0.012(9) | 0.158(13) | 0.031(8) | |

| Jaccard | 0.004(16) | 0.087(58) | 0.122(46) | 0.002(4) | 0.021(10) | 0.031(18) | 0.074(9) | 0.016(2) | |

| LHN | 0.007(22) | 0.017(30) | 0.077(48) | 0.001(5) | 0.000(1) | 0.007(9) | 0.004(3) | 0.009(2) | |

| HDI | 0.000(0) | 0.083(64) | 0.105(45) | 0.002(7) | 0.023(8) | 0.020(12) | 0.075(9) | 0.020(1) | |

| HPI | 0.171(91) | 0.022(25) | 0.142(52) | 0.011(9) | 0.007(4) | 0.012(9) | 0.013(4) | 0.030(3) | |

| Sen | 0.004(16) | 0.087(58) | 0.122(46) | 0.002(4) | 0.021(10) | 0.031(18) | 0.074(9) | 0.016(2) | |

| Sal | 0.000(0) | 0.075(57) | 0.120(39) | 0.000(0) | 0.021(10) | 0.015(15) | 0.056(8) | 0.015(2) | |

| CN | 0.143(73) | 0.135(57) | 0.148(46) | 0.063(32) | 0.099(20) | 0.058(21) | 0.149(15) | 0.069(18) | |

| Our | 0.221(95) | 0.227(55) | 0.188(46) | 0.193(33) | 0.141(19) | 0.075(17) | 0.225(17) | 0.079(4) | |

| 20% | RA | 0.160(76) | 0.156(38) | 0.280(22) | 0.092(33) | 0.150(12) | 0.007(4) | 0.174(9) | 0.022(3) |

| AA | 0.155(78) | 0.161(43) | 0.278(32) | 0.102(31) | 0.155(14) | 0.007(4) | 0.188(9) | 0.023(2) | |

| Jaccard | 0.028(50) | 0.131(53) | 0.157(34) | 0.014(17) | 0.043(10) | 0.027(13) | 0.097(5) | 0.013(4) | |

| LHN | 0.015(23) | 0.027(25) | 0.089(27) | 0.001(3) | 0.002(2) | 0.027(12) | 0.012(3) | 0.010(3) | |

| HDI | 0.045(47) | 0.159(47) | 0.138(35) | 0.017(18) | 0.050(10) | 0.018(7) | 0.113(7) | 0.018(4) | |

| HPI | 0.145(70) | 0.018(14) | 0.192(36) | 0.006(6) | 0.006(2) | 0.015(7) | 0.012(2) | 0.027(3) | |

| Sen | 0.028(50) | 0.131(53) | 0.157(34) | 0.014(17) | 0.043(10) | 0.027(13) | 0.097(5) | 0.013(4) | |

| Sal | 0.023(42) | 0.108(47) | 0.158(33) | 0.009(12) | 0.036(9) | 0.025(11) | 0.071(8) | 0.013(4) | |

| CN | 0.200(59) | 0.226(44) | 0.243(59) | 0.107(30) | 0.146(13) | 0.047(9) | 0.163(16) | 0.085(5) | |

| Our | 0.292(101) | 0.256(64) | 0.252(44) | 0.231(32) | 0.203(15) | 0.056(11) | 0.255(5) | 0.060(4) |

The results are the average of 20 realizations for each network, and probe set EP will be randomly removed every time. The highest value for each network is labeled in boldface. The numbers in the brackets denote the standard deviations. For example, 0.154(109) denotes that the Precision value is 0.154 and the standard deviation is 109 × 10−4.

Figure 3.

The changes of Precision when  increases from 10% to 20% in 8 real-world networks (a–h).

increases from 10% to 20% in 8 real-world networks (a–h).

The results of most algorithms are better for high ratio of EP than low one for Precision metric. The main reason is that the decrease of training set ET will result in weak n′ and strong n′′ according to the definition of AUC (see Methods section), which make negative contributions to AUC. But the increase of probe set EP, the probability to obtain relevant items will increase, and it is easier to find the missing links, which is a good explanation for this phenomenon. Therefore, in practical application it is necessary to combine two metrics to evaluate accuracy of a link prediction method.

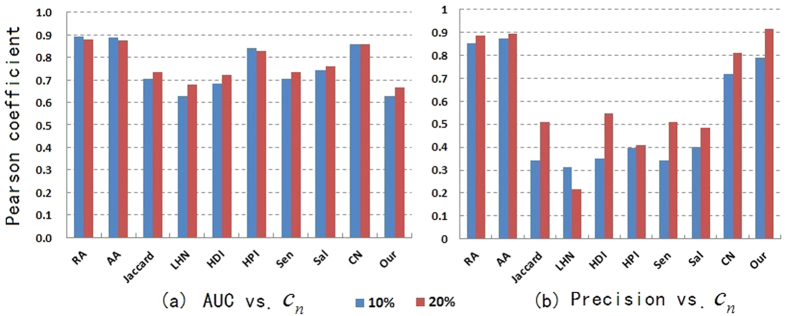

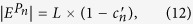

Moreover, CN coefficient cn of original network may also affect prediction accuracy. In Fig. 4 AUC metric and cn have high positive correlation for almost all methods, but for Precision metric there are only RA, AA, CN and our method keeping high positive correlation. The change in probe set has little effect on all methods according to AUC metric, but makes great effect on Jaccard, HDI and Sen method according to Precision metric.

Figure 4. Pearson correlation coefficient of different methods for prediction accuracy metrics vs. cn under 10% and 20% probe set in 8 networks.

(a) The correlation coefficient of different methods for AUC metric vs. cn. (b) The correlation coefficient of different methods for Precision metric vs. cn.

Next, we compared our method with other two classic methods PA (Preferential Attachment Index)31 and LP (Local Path Index)11, which do not directly relate to common neighbors, but based on local information. Table 6 indicates the prediction accuracy of LP, PA and our method under the Precision metric with 10% and 20% probe set, where our method has the best performance.

Table 6. The Precision of LP, PA and our method under 10% and 20% probe set in 8 networks.

| Networks |  |

PA | LP | Our |  |

PA | LP | Our |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Karate | 10% | 0.068(82) | 0.175(140) | 0.221(95) | 20% | 0.118(70) | 0.177(88) | 0.292(101) |

| Dolphins | 0.020(29) | 0.133(70) | 0.227(55) | 0.025(31) | 0.199(47) | 0.256(64) | ||

| Polbook | 0.044(32) | 0.172(44) | 0.188(46) | 0.088(25) | 0.221(39) | 0.252(44) | ||

| Word | 0.082(43) | 0.083(31) | 0.193(33) | 0.150(32) | 0.102(30) | 0.231(32) | ||

| Neural | 0.054(18) | 0.099(18) | 0.141(19) | 0.098(9) | 0.145(14) | 0.203(15) | ||

| Circuit | 0.002(4) | 0.005(7) | 0.075(17) | 0.003(3) | 0.020(8) | 0.056(11) | ||

| 0.018(7) | 0.136(11) | 0.225(17) | 0.029(5) | 0.175(10) | 0.255(5) | |||

| Power | 0.001(1) | 0.042(2) | 0.079(4) | 0.002(1) | 0.045(6) | 0.060(4) |

The results are the average of 20 realizations for each network, and probe set will be randomly removed every time. The highest value is labeled in boldface. The numbers in the brackets denote the standard deviations. For example, 0.068(82) denotes that the Precision value is 0.068 and the standard deviation is 82 × 10−4.

The most striking feature of our method is to make remarkable effect to predict missing links between nodes with no common neighbors (i.e. the accuracy to find  ), compared with LP and PA method according to Precision metric (see Table 7). The above mentioned methods based on common neighbors cannot find any missing links between nodes with no common neighbors, and thus we do not list them here. The results indicate that LP cannot find any missing links with respect to

), compared with LP and PA method according to Precision metric (see Table 7). The above mentioned methods based on common neighbors cannot find any missing links between nodes with no common neighbors, and thus we do not list them here. The results indicate that LP cannot find any missing links with respect to  , and PA method could find a small amount of

, and PA method could find a small amount of  for certain networks because the proportion of

for certain networks because the proportion of  in EP is low except Circuit network and Power network. The proportion can be calculated by Eq. (12).

in EP is low except Circuit network and Power network. The proportion can be calculated by Eq. (12).

Table 7. The Precision of different methods to predict missing links between nodes with no common neighbors under 10% and 20% probe set in 8 networks.

| Networks |  |

PA | LP | Our |  |

PA | LP | Our |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Karate | 10% | 0.05(224) | 0(0) | 0.353(207) | 20% | 0.064(116) | 0(0) | 0.351(169) |

| Dolphins | 0(0) | 0(0) | 0.267(129) | 0.004(19) | 0(0) | 0.265(70) | ||

| Polbook | 0(0) | 0(0) | 0.432(104) | 0(0) | 0(0) | 0.427(47) | ||

| Word | 0(0) | 0(0) | 0.430(54) | 0.003(9) | 0(0) | 0.410(36) | ||

| Neural | 0(0) | 0(0) | 0.441(25) | 0.005(8) | 0(0) | 0.457(20) | ||

| Circuit | 0.002(5) | 0(0) | 0.081(17) | 0.004(3) | 0(0) | 0.059(12) | ||

| 0.001(2) | 0(0) | 0.340(21) | 0.004(4) | 0(0) | 0.335(9) | |||

| Power | 0(1) | 0(0) | 0.059(5) | 0(0) | 0(0) | 0.047(3) |

Precision =  , which denotes the proportion of relevant links in the probe set

, which denotes the proportion of relevant links in the probe set  . The results are the average of 20 realizations for each network, and probe set EP will be randomly removed every time. The highest value for each network is labeled in boldface. The numbers in the brackets denote the standard deviations. For example, 0.064 (116) denotes that the Precision value is 0.064 and the standard deviation is 116 × 10−4. The previous mentioned methods based on common neighbors cannot find any missing links between nodes with no common neighbors, and thus we do not list them here.

. The results are the average of 20 realizations for each network, and probe set EP will be randomly removed every time. The highest value for each network is labeled in boldface. The numbers in the brackets denote the standard deviations. For example, 0.064 (116) denotes that the Precision value is 0.064 and the standard deviation is 116 × 10−4. The previous mentioned methods based on common neighbors cannot find any missing links between nodes with no common neighbors, and thus we do not list them here.

The time-consuming of computing distance between all pairs of nodes is at most O(mN) by using BFS (Breadth First Search). For a sparse network (m = O(N)) the complexity of our method is equivalent to the complexity of CN method.

Discussion and Conclusion

In the past few years, many link prediction algorithms have been proposed, but most of the algorithms do not account for missing links between two nodes with no common neighbors. Generally, to predict these missing links between nodes with no common neighbors are very difficult because they account for low proportion in missing links, but they have significance in determining network structure and network properties. We proposed in this paper a new algorithm based on common neighbors and distance to improve prediction accuracy, which separates link prediction into two parts: predicted links that generate loops of length 3 (missing links between nodes with common neighbors) and predicted links that generate short loops of length more than 3 (missing links between nodes with no common neighbors). By estimating the proportion of missing links between nodes with no common neighbors in total missing links, our algorithm makes remarkable effect to predict missing links between nodes with no common neighbors. For other methods based on common neighbors cannot find any missing links between nodes with no common neighbors. A series of experimental results indicate that prediction accuracy of our proposed method is better than most existing currently used methods for a variety of real-world networks. The complexity of this method is almost same as that of CN method. Moreover, there are two rules: (i) With the increase of probe set, experimental results indicate that the changing trend of scores according to AUC metric is not consistent with Precision metric for most algorithms and networks. Thus, it is necessary to combine two metrics to evaluate the accuracy of a link prediction method. (ii) The between AUC metric and cn has high positive correlation.

On the other hand, the questions of link prediction have not been solved completely. For example, how to evaluate superiority of a link prediction method except current metrics. Because a good prediction method should not only take into account prediction accuracy, but also pay attention to network properties. Furthermore, it is important how to choose a suitable link prediction method according to the feature of network as there is no absolutely good method for all networks. Link prediction has been extended to weighted and directed version32,33,34,35. It can also predict signed links with positive and negative relationships in social networks, and predict spurious interactions15,36,37. Whether it is possible to modify our method to deal with them. All are a long-standing challenge work.

Methods

Metrics

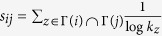

AUC is defined as:

|

A link prediction method provides an ordered list of scores of all links in U − ET (scores represent the likelihood of missing links), where U is a universal set for  links. At each time, we will randomly select a link in U − E and a link in probe set EP to compare their scores. After comparison of n times, there are n′ times the links in EP having higher scores and n′′ times they have same scores. The degree to which the score exceeds 0.5 represents how better the method performs than pure chance.

links. At each time, we will randomly select a link in U − E and a link in probe set EP to compare their scores. After comparison of n times, there are n′ times the links in EP having higher scores and n′′ times they have same scores. The degree to which the score exceeds 0.5 represents how better the method performs than pure chance.

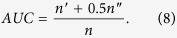

Another metric to measure accuracy is Precision, which is computed as follows:

|

where Lr is relevant links (i.e. generally, we take the top-L links as the predicted links according to scores, and there are Lr links in the probe set EP (L = |EP|)). Thus, the higher Precision value means the higher accuracy.

Our link prediction method

Given an undirected and unweighted network G = (V, E) with vertex set V = {v1, v2, …, vN} and the observed link set E, where the size of E is m. The self-loops and multiple links are not allowed. In order to evaluate the performance of an algorithm, a certain proportion links in G will be randomly selected to constitute probe set EP, and the rest links constitute training set ET (ET ∪ EP = E, ET ∩ EP = ∅). We separate EP into two subsets:  and

and  denote respectively link set between nodes with common neighbors and link set between nodes with no common neighbors

denote respectively link set between nodes with common neighbors and link set between nodes with no common neighbors  .

.  and

and  are calculated using Eqs (11 and 12) because EP is used for testing and is viewed as unknown information. According to computation of sij (Eq. (13)) to obtain the scores for all non-exist links U − ET, sort the list of scores in non-increasing order. Then select top-

are calculated using Eqs (11 and 12) because EP is used for testing and is viewed as unknown information. According to computation of sij (Eq. (13)) to obtain the scores for all non-exist links U − ET, sort the list of scores in non-increasing order. Then select top- links between nodes with common neighbors and top-

links between nodes with common neighbors and top- links between nodes with no common neighbors from U − ET to constitute predicted links.

links between nodes with no common neighbors from U − ET to constitute predicted links.

|

|

|

where Γ(i) denotes the set of neighbors of node i. δij = 1, if Γ(i) ∩ Γ(j) ≠ ∅, 0 otherwise, and i ~ j denotes node i and j to be adjacent.

|

where CNij = |Γ(i) ∩ Γ(j)| is the number of common neighbors of node i and j. dij is the distance between i and j. The Precision metric in Eq. (9) can be written as follows:

|

where  ,

,  denote relevant links between nodes with common neighbors and relevant links between nodes with no common neighbors, respectively. Similarly, to predict future missing links for a current observed network G,

denote relevant links between nodes with common neighbors and relevant links between nodes with no common neighbors, respectively. Similarly, to predict future missing links for a current observed network G,  is replaced by cn as follows:

is replaced by cn as follows:

|

which is the proportion of links between nodes with common neighbors in link set E.

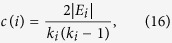

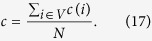

Parameters

The local clustering coefficient c(i) of a node i is defined as the probability that two distinct neighbors of i are connected38.

|

where |Ei| denotes the number of links that actually exist between ki nodes, and c(i) = 0 if ki = 0, 1. The clustering coefficient c of a network is the average of all nodes:

|

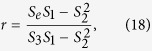

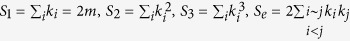

Assortativity of network is called as assortative mixing, which refers to the tendency of network nodes to joint other nodes preferentially with similar or opposite properties39:

|

where  .

.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Yang, J. and Zhang, X.-D. Predicting missing links in complex networks based on common neighbors and distance. Sci. Rep. 6, 38208; doi: 10.1038/srep38208 (2016).

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the anonymous referees for their valuable comments and suggestions to improve the final version of the paper. This work is supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos 11531001 and 11271256), the Joint NSFC-ISF Research Program (jointly funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China and the Israel Science Foundation (No. 11561141001)), Innovation Program of Shanghai Municipal Education Commission (No. 14ZZ016) and Specialized Research Fund for the Doctoral Program of Higher Education (No. 20130073110075).

Footnotes

Author Contributions This manuscript was completed by J.-X. Yang and X.-D. Zhang. In the initial stage X.-D. Zhang provided many good ideas and methods to achieve this work. J.-X. Yang deduced the mathematical equation and model. X.-D. Zhang analysed the mathematical equation and model. Afterward J.-X. Yang finished the experiment and data processing, and written this manuscript. X.-D. Zhang revised the research manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript and approved the final version of the manuscript.

References

- Von Mering C. et al. Comparative assessment of large-scale data sets of protein-protein interactions. Nature 417, 399–403 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amaral L. A. N. A truermeasure of our ignorance. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 105, 6795–6796 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barabási A. L. et al. Evolution of the social network of scientific collaborations. Physica A 311, 590–614 (2002). [Google Scholar]

- Dorogovtsev S. N. & Mendes J. F. Evolution of networks. Adv. Phys. 51, 1079–1187 (2002). [Google Scholar]

- Bringmann B., Berlingerio M., Bonchi F. & Gionis A. Learning and predicting the evolution of social networks. IEEE Intell. Syst. 25, 26–35 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- Guimerà R., Llorente A., Moro E. & Sales-Pardo M. Predicting human preferences using the block structure of complex social networks. PLoS ONE 7, e44620 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rovira-Asenjo N., Gumí T., Sales-Pardo M. & Guimerà R. Predicting future conflict between team-members with parameter-free models of social networks. Sci. Rep. 3, 1999 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Z. & Lin D. K. J. The time-series link prediction problem with applications in communication surveillance. Informs. J. Comput. 21, 286–303 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- Almansoori W. et al. Link prediction and classification in social networks and its application in healthcare and systems biology. Network Modeling Analysis in Health Informatics and Bioinformatics 1, 27–36 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- Lü L. & Zhou T. Link prediction in complex networks: A survey. Physica A 390, 1150–1170 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- Lü L., Jin C. H. & Zhou T. Similarity index based on local paths for link prediction of complex networks. Phy. Rev. E 80, 046122 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barzel B. & Barabási A. L. Network link prediction by global silencing of indirect correlations. Nat. Biotechnol. 31, 720–725 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang T., Wang H. & Wang X. CD-Based Indices for Link Prediction in Complex Network. PLoS ONE 11, e0146727 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clauset A., Moore C. & Newman M. E. J. Hierarchical structure and the prediction of missing links in networks. Nature 453, 98–101 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guimerà R. & Sales-Pardo M. Missing and spurious interactions and the reconstruction of complex networks. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 106, 22073–22078 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan B. & Gregory S. Finding missing edges in networks based on their community structure. Phy. Rev. E 85, 056112 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Z., He J.-L., Kapoor K. & Srivastava J. Correlations between community structure and link formation in complex networks. PLoS ONE 8, e72908 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang P., Xu B. W., Wu Y. R. & Zhou X. Y. Link prediction in social networks: the-state-of-the-art. Sci. China Inform. Sci. 58, 1–38 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- Zhang P., Wang F., Wang X., Zeng A. & Xiao J. The reconstruction of complex networks with community structure. Sci. Rep. 5, 17287 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan F., Xia Y. & Zhu B. Link Prediction in Complex Networks: A Mutual Information Perspective. PLoS ONE 9, e107056 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lü L., Pan L., Zhou T., Zhang Y.-C. & Stanley H. E. Toward link predictability of complex networks. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 112, 2325–2330 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu B. & Xia Y. An information-theoretic model for link prediction in complex networks. Sci. Rep. 5, 13707 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zachary W. W. An information flow model for conflict and fission in small groups. J. Anthropol. Res. 33, 452–473 (1977). [Google Scholar]

- Lusseau D. et al. The bottlenose dolphin community of Doubtful Sound features a large proportion of long-lasting associations. Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 54, 396–405 (2003). [Google Scholar]

- Newman M. E. J. Finding community structure in networks using the eigenvectors of matrices. Phy. Rev. E 74, 036104 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watts D. J. & Strogatz S. H. Collective dynamics of small-world networks. Nature 393, 440–442 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milo R. et al. Superfamilies of evolved and designed networks. Science 303, 1538–1542 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guimerà R., Danon L., Díaz-Guilera A., Giralt F. & Arenas A. Self-similar community structure in a network of human interactions. Phy. Rev. E 68, 065103 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanley J. A. & McNeil B. J. The meaning and use of the area under a receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve. Radiology 143, 29–36 (1982). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herlocker J. L., Konstan J. A., Terveen L. G. & Riedl J. T. Evaluating collaborative filtering recommender systems. ACM T. Inform. Syst. 22, 5–53 (2004). [Google Scholar]

- Barabási A. L. & Albert R. Emergence of Scaling in Random Networks. Science 286, 509–512 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murata T. & Moriyasu S. Link prediction of social networks based on weighted proximity measures. Web. Intel. IEEE/WIC/ACM Conf. IEEE 85–88 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- Lü L. & Zhou T. Link prediction in weighted networks: The role of weak ties. EPL. 89, 18001 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- Liu D., Lv Y. & Yu Z. LRP: A Theory of Link Formation in Directed Networks. In Proc. ACMASE Conf. 5 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- Zhao J. et al. Prediction of links and weights in networks by reliable routes. Sci. Rep. 5, 12261 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang P., Zeng A. & Fan Y. Identifying missing and spurious connections via the bi-directional diffusion on bipartite networks. Phys. Lett. A 378, 2350–2354 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- Wang G. N., Gao H., Chen L., Mensah D. N. A. & Fu Y. Predicting positive and negative relationships in large social networks. PLoS ONE 10, e0129530 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albert R. & Barabási A. L. Statistical mechanics of complex networks. Rev. Mod. Phys. 74, 47 (2002). [Google Scholar]

- Newman M. E. J. Assortative mixing in networks. Phys. Rev. Lett. 89, 208701 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]