Abstract

The complex anatomy of the skull and face arises from the requirement to support multiple sensory and structural functions. During embryonic development, the diverse component elements of the neuro- and viscerocranium must be generated independently and subsequently united in a manner that sustains and promotes the growth of the brain and sensory organs, while achieving a level of structural integrity necessary for the individual to become a free-living organism. While each of these individual craniofacial components is essential, the cranial and facial midline lies at a structural nexus that unites these disparately derived elements, fusing them into a whole. Defects of the craniofacial midline can have a profound impact on both form and function, manifesting in a diverse array of phenotypes and clinical entities that can be broadly defined as frontonasal dysplasias (FNDs). Recent advances in the identification of the genetic basis of FNDs along with the analysis of developmental mechanisms impacted by these mutations have dramatically altered our understanding of this complex group of conditions.

Key Words: Craniofacial midline, Frontonasal dysplasias, Malformations

The diversity of the frontonasal dysplasia (FND) phenotypes and the overlap with related craniofacial and more complex syndromes can confound the identification of FND. Although frontonasal malformations and their associated comorbidities may need to be viewed in light of more recent molecular findings, the defining features of FND were established decades ago [Sedano et al., 1970; Sedano and Gorlin, 1988] and still serve as the foundation for classifying these conditions (table 1). The core characteristics of FND are listed in table 2 and while the presentation is highly variable, at least 2 of these features are required to make a diagnosis.

Table 1.

Diagnostic criteria of FND

| Anterior cranium bifidum occultum |

| V-shaped or widow's peak of frontal hairline |

| True ocular hypertelorism (IP distance >97th centile) |

| Broadening of nasal root |

| Lack of nasal tip formation |

| Median facial cleft (nose and/or upper lip and palate) |

| Unilateral or bilateral clefting of the alae nasi |

At least 2 of these features are required to make a diagnosis. Established from Sedano and Gorlin [1988].

Table 2.

Features of defined FND syndromes

| Distinguishing craniofacial features | Integumentary | Musculoskeletal | CNS/cognition | Genitourinary | References | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FND1 (ALX3) | long philtrum with periphiltral swelling, midline notch upper lip and alveolus, upper eyelid ptosis | midline dermoid cyst | – | normal cognition | – | Twigg et al., 2009 |

| FND2 (ALX4) | large skull defect, blepharophimosis, microphthalmia | total alopecia/sparse scalp hair | – | mildline intracranial lipoma, callosal anomaly, normal cognition to DD/ID | cryptorchidism, hypospadias | Kayserili et al., 2012; Kariminejad et al., 2014 |

| FND3 (ALX1) | extreme micropthalmia, upper eyelid colobomata, bilateral facial cleft, complete cleft plate | sparse eyelashes, absence of eyebrows | – | – | – | Uz et al., 2010 |

| Heterozygous SIX2 deletion (FND4?) | high anterior hairline, frontal bossing large anterior fontonelle, ptosis, epicanthus inversus, parietal foramina, cranio-synostosis (metopic, sagittal) | – | – | normal cognition | – | Hufnagel et al., 2016 |

| CFNS (EFNB1) | craniosynostosis (coronal), craniofacial asymmetry | longitudinal nail ridging, coarse thick hair | sloping shoulders with dysplastic clavicles (pseudoarthrosis), Sprengel deformity, chest deformity, duplicated/broad halluces, cutaneous syndactyly, congenital diaphragmatic hernia | callosal anomaly, normal cognition to mild DD/ID | – | van den Elzen et al., 2014 |

| AFND (ZSWIM6) | parietal foramina (variable) | – | preaxial polydactyly, unilateral or bilateral hemimelia, hypoplastic patellae | PVNH, callosal anomaly, absent olfactory bulbs, hypopituitarism, DD/ID | cryptorchidism | Smith et al., 2014 |

| OAFNS (unknown) | microtia, preauricular tags, facial asymmetry, mandibular hypoplasia, epibulbar dermoids (OAVS) | abnormal hairline and eyebrows | vertebral fusion, complex vertebral segmentation, rib anomalies | intracranial lipomas, encephalocoeles, callosal anomaly, calcification of the cerebral falx, DD/ID | – | Evans et al., 2013 |

| AFFND (unknown) | retinal coloboma, optic nerve atrophy, ulcerated corneae, polar cataracts, iris atrophy, micropthalmia, S-shaped palpebral fissure | abnormal hairline/eyelashes/eyebrow, hypoplastic nails | short stature, scoliosis, polysyndactyly of fingers, camptobrachydactyly, (hypoplastic distal phalanges, short metacarpals), hip dislocation, hypoplastic fibulae, tarsal anomalies, and tibio-talar subluxation | mixed hearing loss, epilepsy, DD/ID | hypospadias, bifid/shawl scrotum (mainly in AFFND2) | Prontera et al., 2011; Richieri-Costa et al., 1989 |

AFFND = Acrofrontofacionasal dysplasia; DD/ID = developmental delay/intellectual disability; IP = interpupillary distance; PVNH = periventricular nodular heterotopia; – = not present.

Developmental Origins of the Frontonasal Process

The rationale for association of the specific features defining FND is based on the developmental origin of the craniofacial midline. A brief introduction to the early stages of craniofacial development illustrates the common origins of the structures impacted in FND and aids in understanding why certain phenotypes occur together. The mid- and upper face is constructed from 3 major tissue blocks: the paired maxillary processes which produce the upper jaw, cheek bones, and lateral nasal structures, plus the frontonasal process (FNP) which produces the midline tissue including the frontal bones, nasal bridge and nasal tip, and which are responsible for uniting the bilateral maxillary arch-derived structures (fig. 1). The maxillary and frontonasal processes are composed of an outer covering of ectoderm overlaying a small but highly proliferative neural crest derived mesenchyme responsible for the construction of the facial skeleton. However, while the maxillary process is enclosed on the prospective oral surface by an endodermally derived epithelium, FNP forms in direct contact with the anterior neural tube that will form the telencephalon and eventually the forebrain. Thus, FNP is subject to direct influence from the developing forebrain neuroepithelium, and this influence has profound implications for growth and patterning of the midface.

Fig. 1.

Embryological origins of the frontonasal process. The paired maxillary processes (blue) and FNP (yellow) have begun development by the end of the first month of gestation. Under normal circumstances, FNP has fused with the maxillary primordia by the end of the first trimester to form the midfacial structures. IMS = Intermaxillary segment; LNP = lateral nasal process; MNP = medial nasal process; Mx = maxillary process; NP = nasal pit.

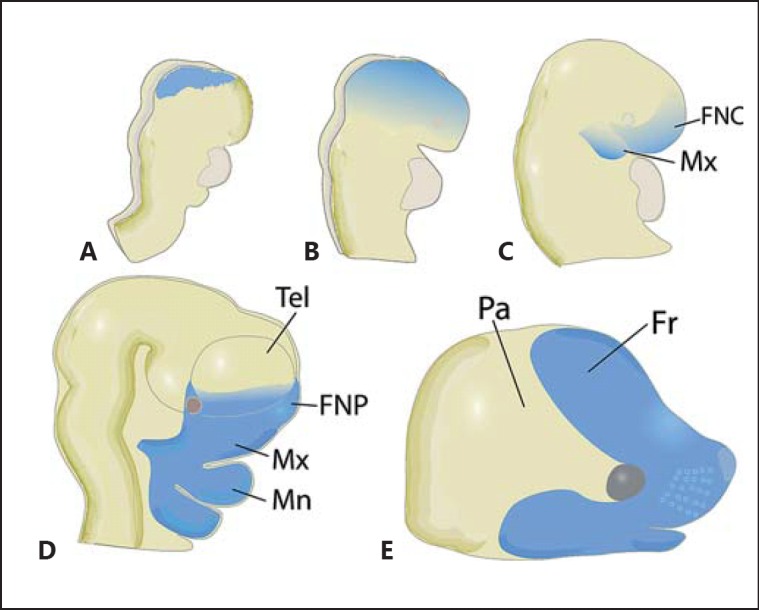

The neural crest is a highly migratory and invasive population of mesenchymal cells derived from the lateral margins of the epithelial neural plate following a process known as epithelial to mesenchymal transformation [Le Douarin, 1982, 2012; Zhang et al., 2014]. The neural crest cells that contribute to FNP originate in the prospective caudal forebrain and rostral midbrain neural plate prior to cranial neural tube closure and migrate between the basal surface of the neural plate and overlying ectoderm (fig. 2) [Nichols, 1981; Chai et al., 2000; Jiang et al., 2002]. During this migratory phase, the frontonasal neural crest cells spread as a sheet-like population, passing over the prospective telencephalon and eye to take up residence in the most rostral aspect of the neural tube [Jiang et al., 2002]. As the telencephalon expands, this population becomes predominantly restricted to the prospective frontonasal region of the developing face.

Fig. 2.

Origins and distribution of the frontonasal neural crest cells. A The frontonasal neural crest cell population (blue) emerges from the lateral margin of the neural folds prior to neural tube formation. B, C FNCs then migrate ventrally over the anterior neural folds (B) eventually reaching the frontonasal region of the neural tube soon after fusion of the neural folds (C). D FNCs are subsequently restricted to the prospective frontonasal region as the telencephalic vesicles rapidly expand. E The expansion of FNCs results in outgrowth of the midface and formation of the frontal bone over the forebrain. Data derived from Chai et al. [2000] and Jiang et al. [2002]. FNC = Frontonasal neural crest cell; FNP = frontonasal process; Fr = frontal bone; Mn = mandibular process; Mx = maxillary process; Pa = parietal bone; Tel = telencephalon.

The frontonasal neural crest cells are initially restricted in number as they exit the neural plate and must expand through rapid proliferation. Expansion begins during migration, but the neural crest cells encounter major mitogenic influences upon reaching their destinations within the frontonasal region and nasal processes. The coordinated expression of Shh, Bmp4, and Fgf8 plays a profound role in establishing growth and patterning of the facial primordia, and disruption of this coordination results in FNP defects and facial clefting [Foppiano et al., 2007; Hu and Marcucio, 2009a; Hu et al., 2015]. The expression domains of Fgf8 and Shh in the frontonasal ectoderm form a signalling centre known as the frontonasal ectodermal zone that dictates the morphogenetic outcome of FNP development [Hu et al., 2003, 2015; Hu and Marcucio, 2009a]. Bmp signalling, and Bmp4 in particular, is also a key factor in patterning and outgrowth of FNP [Ashique et al., 2002; Abzhanov et al., 2004; Wu et al., 2004]. In addition to promoting the growth of FNP, blockade of Bmp signalling results in downregulation of Shh in FNP [Foppiano et al., 2007] and compromises the ability of Shh to induce its own expression [Hu et al., 2015]. Similarly, Fgf signalling from the nasal pits is required for normal proliferation of FNP mesenchyme, and blocking this signalling also results in facial clefts [Szabo-Rogers et al., 2008]. The efficacy of these patterning systems requires tightly regulated spatial and temporal gene expression, and the distribution of these factors serve as markers of the individual facial primordia enabling a fine scale analysis of developmental defects (fig. 3). The patterning influence of the frontonasal ectodermal zone has been best characterised in the chicken embryo, where disruption of the tightly regulated distribution of FGF8 and SHH results in failure of midface outgrowth [Hu et al., 2003; Hu and Marcucio, 2009a]. However, a similar signalling system has been demonstrated in mouse embryos, suggesting that the regulation of mid- and upper facial patterning by this SHH/FGF8 mechanism is broadly utilized [Hu and Marcucio, 2009b].

Fig. 3.

In situ hybridisation illustrating the expression of genes marking the components of the facial primordia. A Twist1 expression marking the FNCs migrating ventrally towards the prospective FNP. B Fgf8 expression marking the anterior neural ectoderm (prospective forebrain neural tube) and ectoderm covering the MNP and LNP. C Msx2 expression marking the MNP, LNP, and MX prior to the completion of fusion. ANE = Anterior neural ectoderm; E = eye primordia; Md = mandibular process; NP = nasal placode. For further abbreviations see figure legends 1 and 2.

The individual facial processes expand and elongate as the mesenchymal populations proliferate and eventually adjacent processes make contact between opposing epithelial surfaces. The fusion process is best characterised in the formation of the secondary palate where individual epithelial cells make an initial contact through extension of cell surface protrusions known as filopodia [Taya et al., 1999]. Following this initial contact, opposing epithelial surfaces make direct contact, forming a transient bi-epithelial seam which is itself removed through a combination of programmed cell death and conversion of epithelial cells into mesenchyme via epithelial to mesenchymal transformation [Xu et al., 2006; Ke et al., 2015; Lan et al., 2015]. Following successful fusion, the previously separate mesenchymal populations become united as a single continuous population. The neural crest cells responsible for the production of skeletal elements within the mid- and upper face generate both bone and cartilage through direct transition from a multipotent mesenchymal state into terminally differentiated cell types [Bronner and LeDouarin, 2012]. The differentiation of neural crest-derived progenitors within the unified facial processes subsequently results in formation of a continuous facial skeleton. It is important to note that fusion of the facial processes precedes osteogenic differentiation of neural crest-derived progenitor cells. This implies that overt clefting and facial hypoplasia of otherwise intact skeletal elements may arise from defects in temporally separable developmental events. The challenge may therefore be to determine if these defects in different individuals are attributable to the same or independent genetic or environmental insults.

Phenotypic Spectrum of the FNDs

The syndromes within the FND spectrum are diverse and genetically heterogeneous. There are currently 6 genes associated with FND spectrum disorders, and while these findings are invaluable in understanding the origins and presentation of each condition, they account for only a small fraction of cases with the majority of affected individuals yet to attain a molecular diagnosis (table 2). In addition to these genetic influences, environmental insults are also likely to contribute to a proportion of FND cases. Consideration of the clinical, molecular and developmental aspects of the molecularly defined FND spectrum disorders will assist in understanding the aetiology of FND still awaiting molecular definition.

Craniofrontonasal syndrome (CFNS; OMIM 304110) is a distinctive condition which presents in females as FND including severe hypertelorism, a bifid or hypoplastic nasal tip, coronal craniosynostosis, malformation of the clavicle, longitudinally grooved or split nails, and thick, wiry hair. CFNS is less distinct in males, often presenting as hypertelorism and occasionally cleft lip and/or palate. This mode of presentation strongly suggested an X-linked aetiology, and prior to identification of the causative genetic mutations, there was suspicion of complicated modifier gene scenarios or embryonic lethality in males [Cohen, 1979; Sax and Flannery, 1986; Grutzner and Gorlin, 1988; Devriendt et al., 1995]. However, the identification of EFNB1 mutations in affected females resulted in the discovery of similar mutations in mildly affected males indicating that, in contrast to the more typical presentation of X-linked conditions, females have a more severe phenotype following mutation of EFNB1. Further, the development of very sensitive approaches to identifying low-level mosaicism has resulted in the identification of EFNB1 mutations in the majority of CFNS patients [Twigg et al., 2004; van den Elzen et al., 2014].

The mechanistic concept explaining the phenomenon of the female phenotypic bias in CFNS was first proposed as metabolic interference in which random X inactivation leads to a metabolically mixed population in females [Rollnick et al., 1981; Feldman et al., 1997]. More recent experimental investigation has demonstrated that at least in the case of EFNB1, this phenomenon is occurring at the cellular level rather than being strictly metabolic, prompting adoption of the term ‘cellular interference’ [Davy et al., 2006; Twigg et al., 2013]. The EFNB1 gene encodes ephrin-B1, a membrane-bound ligand for the Eph receptor, involved in repulsive signalling between individual cells [Krull et al., 1997; Mellitzer et al., 1999]. There appears to be no skewing of X inactivation in CFNS individuals, and this results in a mixed population of cells in females in which either the mutant or wildtype allele is expressed [Twigg et al., 2004; Wieland et al., 2007]. This results in the formation of ectopic boundaries within the frontal bone precursors in which osteogenic differentiation is inhibited, producing the characteristic hypoplastic calvarial phenotype [Davy et al., 2006]. The cell sorting/boundary formation activities of ephrin-B1 appear to be redundant since males which only produce mutant protein are less susceptible to this defect. However, in an intriguing twist, males harbouring a mosaic mutation in EPHNB1 replicate the mixed population phenomenon seen in CFNS females and may exhibit a more severe and distinct CFNS phenotype than males with mutations in all cells, confirming the origins of the apparently paradoxically more severe phenotype in females [Twigg et al., 2013].

Frontorhiny (FND1; OMIM 606014) was the first of the FND syndromes to be defined molecularly with the discovery of homozygous ALX3 mutations in 7 families [Twigg et al., 2009]. In addition to the core features of FND including hypertelorism, widely spaced nasal bones and a bifid nasal tip, FND1 is characterised by features affecting the distal aspect of FNP such as a short medial nasal region with a broad columnella that attaches to the widely spaced nasal alae producing a distinctive concave shape to the nasal tip and a long philtrum with raised and fleshy lateral margins. Overt clefting does not appear to be a major feature of FND1, although the generally deficient FNP can result in midline notching in the upper lip and alveolar bone.

FND2 (OMIM 605420) is a recessive condition characterised by hypertelorism, severely depressed nasal bridge, malar flattening, bifid nasal tip, cleft nasal alae, craniosynostosis, hypoplastic calvaria resulting in extensive foramina and cranium bifidum, total alopecia, and brain abnormalities including agenesis of the corpus callosum. FND2 results from homozygous ALX4 mutations and has been documented in 3 consanguineous families [Kayserili et al., 2009; Kariminejad et al., 2014]. Interestingly, heterozygous mutations in ALX4 cause parietal foramina 2 (OMIM 609597) which, in severe cases, may include hypertelorism and nasal abnormalities [Wuyts et al., 2000; Mavrogiannis et al., 2001; Kayserili et al., 2012; Bertola et al., 2013; Altunoglu et al., 2014]. Parietal foramina 1 (OMIM 168500) is caused by a heterozygous mutation in the MSX2 gene [Wilkie et al., 2000; Spruijt et al., 2005] and parietal foramina 1 and 2 are clinically indistinguishable [Mavrogiannis et al., 2006]. Further, activating mutations in both MSX2 and ALX4 have been implicated in craniosynostosis [Jabs et al., 1993; Ma et al., 1996; Yagnik et al., 2012; Florisson et al., 2013]. This highlights the involvement of calvarial development defects in the pathogenic presentation of FND and also supports the contention that FND, parietal foramina and craniosynostosis may represent components of a phenotypic spectrum [Yagnik et al., 2012].

FND3 (OMIM 601527) is a severe form of FND involving a profound hypoplasia of the tissue derived from FNP resulting in midfacial clefting due to a complete failure of fusion between the frontonasal and maxillary arch-derived tissues [Uz et al., 2010]. In addition, the 4 individuals (from 2 families) reported with this condition had hypertelorism, a wide nasal base, isolated nasal alae, malformed orbits, microphthalmia, cleft primary and secondary palate as well as low-set, posteriorly rotated ears. FND3 results from a complete loss of ALX1 either through homozygous genomic deletion of ALX1 or functionally through intragenic mutation. A milder manifestation of FND3 has been reported due to a homozygous splice acceptor site mutation which may encode a mutant ALX1 protein harbouring residual activity [Ullah et al., 2016].

A similarly severe FND phenotype has been reported in Burmese cats selected for a brachycephalic trait which has become popular in recent decades [Noden and Evans, 1986]. Approximately 25% of kittens born from matings between short-faced parents exhibit this FND phenotype, suggesting a recessive inheritance. Genetic analysis of this variant, known as the ‘Contemporary’ Burmese, identified a 12-bp deletion within the ALX1 gene in affected kittens [Lyons et al., 2016]. Interestingly, the prized Contemporary Burmese harbours the same deletion in heterozygous form, while no ALX1 deletion has been identified in the traditional long-faced Burmese, suggesting that the trait appears to be semidominant. This is strikingly similar to the impact of ALX4 mutations in humans causing parietal foramina in a heterozygous form but FND in a homozygous state, illustrating the value of studying a range of animal models to understand the complex developmental biology of human congenital malformation.

The Alx genes are closely related homeodomain containing transcription factors that additionally possess a conserved Aristaless domain. In mouse embryos, Alx1 (Cart1), Alx3 and Alx4 are each expressed in FNP mesenchyme spanning the stages at which cranial neural crest cells are migrating into the facial primordia in strongly overlapping domains [Beverdam and Meijlink, 2001]. Mutations in the ALX genes causing FND spectrum disorders appear to occur throughout the protein but have a bias towards the homeodomain. The homeodomain is a hallmark of this class of transcription factors, exhibiting very high levels of homology within related family members [D'Elia et al., 2001]. Mutations in a range of homeodomain class transcription factors are associated with congenital anomalies in humans and missense mutations within the homeodomain can cause both gain and loss of DNA-binding activity as has been observed for both ALX4 and MSX2 [Ma et al., 1996; Wilkie et al., 2000; Wuyts et al., 2000; Yagnik et al., 2012; Florisson et al., 2013]. The ALX4 deletion resulting in the Contemporary Burmese FND phenotype also occurs within the homeodomain [Lyons et al., 2016].

In zebrafish, while alx1, alx3 and alx4 are each expressed in the facial mesenchyme, alx1 alone is expressed in the recently emigrating neural crest at the earliest stages of migration from the neural tube [Dee et al., 2013]. Inhibition of alx1 expression in zebrafish embryos results in a severe FND-like phenotype with microphthalmia, coloboma, and severely hypoplastic facial skeleton. Inhibition of alx3 expression did not result in abnormalities of the facial skeleton [Dee et al., 2013], suggesting that while there is significant functional redundancy between alx genes, the early expression of alx1 relative to other alx family members results in a more acute requirement for alx1 expression during development of the zebrafish frontonasal structures. The observation of an acute, early requirement for alx1 during neural crest migration is consistent with the severe FND phenotype associated with loss of ALX1 in humans and suggests that as with zebrafish, human embryos null for ALX1 are likely to have a severely compromised frontonasal neural crest cell population. In mice, loss of Alx1 results in a failure of midbrain neural tube closure and consequent loss of the skull vault [Zhao et al., 1996]. Interestingly, Alx1 null mice appear to harbour a robust FNP-derived nasal skeleton despite the severe exencephalic phenotype, suggesting a less strict requirement for Alx1 in early mouse cranial neural crest cell development than in either human or zebrafish.

Homozygous loss of Alx4 in mice does not produce an FND phenotype but results in reduced parietal bones in neonates [Qu et al., 1997]. Alx4 mutants predominantly die perinatally due to complications arising from ventral body wall defects, but those that survive to adulthood exhibit normal-sized parietal bones, suggesting that a loss of Alx4 results in a delay rather than an overt defect in parietal bone development. Alx3 is expressed in a pattern that overlaps substantially with that of Alx4 within the frontonasal mesenchyme [Beverdam and Meijlink, 2001]. Mice harbouring a homozygous deletion of Alx3 appear normal. However, compound Alx3/Alx4 null mice have a severe FND phenotype with complete midline facial clefting resulting from elevated cell death within FNP and resulting hypoplasia [Beverdam et al., 2001]. This clearly demonstrates the redundant functions in the frontonasal development of Alx3 and Alx4 in mice but again highlights the differential sensitivity to Alx gene dosage between mice and humans. Despite these differences, the phenotypes of the Alx4 and Alx3/4 null mouse models are consistent with those seen in human FND and therefore provide opportunities to understand the developmental anomalies and molecular mechanisms resulting in failure of FNP development.

Acromelic frontonasal dysplasia (AFND) is a very rare clinically distinct condition exhibiting severe craniofacial anomalies including hypertelorism, median cleft face, bifid nasal tip, widely spaced nasal alae, parietal defects, and limb anomalies including polydactyly, tibial hypoplasia, and talipes equinovarus. In contrast to other conditions within the FND spectrum, AFND individuals typically display marked mental retardation and possess a range of brain malformations including hydrocephalus, agenesis of the corpus callosum, interhemispheric lipoma and periventricular nodular heterotopia [Richieri-Costa et al., 1992; Verloes et al., 1992; Slaney et al., 1999]. The identical heterozygous c.3487C>T mutation in the ZSWIM6 gene has been detected in 8 unrelated individuals [Smith et al., 2014; Twigg et al., 2016]. This specific, putative gain of function, mutation appears to be crucial in the aetiology of AFND since deletions spanning ZSWIM6 are present in individuals with unrelated phenotypes [Smith et al., 2014]. There is currently no animal model of AFND.

The function of ZSWIM6 is poorly characterised, but the SWIM domain has homology to sequences within a group of SWI2/SNF2 containing proteins and is predicted to form a zinc finger domain, suggesting a role in DNA binding, chromatin dynamics and transcriptional regulation [Muthuswami et al., 2000; Makarova et al., 2002; Rieger et al., 2012]. The details of ZSWIM6 expression within early embryonic development are yet to emerge, but it appears to be most strongly expressed in the cranial neural tube in mouse (http://www.informatics.jax.org/gxd) and zebrafish [Smith et al., 2014] consistent with the severe mental retardation phenotype of AFND. The function of ZSWIM6 in the development of the frontonasal structures and calvaria is presently unknown.

A mild form of FND has recently been attributed to a heterozygous deletion of the SIX2 gene in a single family [Hufnagel et al., 2016]. The proband had frontal bossing with a large anterior fontanelle, hypertelorism, ptosis, a flat nasal bridge, broad nasal tip, bilateral parietal foramina, complete sagittal synostosis as well as subtle cranial base anomalies and macrocephaly at 22 months of age. This form of FND (FND4?) is unusual in the involvement of the skull base, a malformation of which is not typically associated with developmental defects of FNP. The anterior skull and facial skeleton are produced from direct ossification of neural crest progenitors, while the skull base is derived from mesodermal precursors through endochondral ossification. However, mouse models of Six2 involvement in craniofacial development have demonstrated a link between these 2 independently derived structures.

The Brachyrrhine (Br) radiation-induced mutant mouse line exhibits a severe FND phenotype that appears to be linked to a reduction in Six2 expression, most likely due to a mutation in a regulatory region [McBratney et al., 2003; Fogelgren et al., 2008]. Six2 expression normally appears in the frontonasal mesenchyme from mid-gestation when the frontonasal neural crest cells have completed migration but is also expressed in the maxillary and mandibular primordia [Oliver et al., 1995]. Heterozygous Br mice are retrognathic and harbour skull base defects, while homozygotes have a complete failure of FNP growth and exhibit midfacial clefting [Fogelgren et al., 2008]. The skull vault appears compressed in the anterior-posterior axis due to reduced skull base growth since no craniosynostosis in Six2 null or Br mice was observed [Fogelgren et al., 2008; He et al., 2010]. Cranial skeletal defects in these mouse models include loss of the nasal septum, primary and secondary palate and presphenoid as well as a malformation of the basisphenoid. The skull base grows through a process of endochondral ossification, and the restricted growth of the skull base in Six2 null mice has been shown to be due to premature ossification of cartilaginous growth plates [He et al., 2010]. Once again, there appears to be a differential sensitivity for Six2 dosage between mouse and human, particularly in the mandibular and frontonasal process neural crest. However, these mouse models recapitulate a number of core features of SIX2 associated FND in humans and provide mechanistic insights into the origins of this craniofacial malformation.

Oculoauriculofrontonasal syndrome (OAFNS; OMIM 601452) is characterised by features overlapping those of FND and the oculoauriculovertebral spectrum (OAVS). The features of OAVS that have been observed in patients with OAFNS include microtia, preauricular tags, hemifacial microsomia, and epibulbar dermoids. Additional features include midline intracranial lipomas, encephaloceles, callosal anomalies, and calcification of the cerebral falx. Cognitive impairment does not seem to be a common finding, but developmental delay and learning difficulties are reported [Gabbett et al., 2008; Guion-Almeida and Richieri-Costa, 2010]. As the molecular pathogenesis of these conditions is still unknown, it is unclear if OAFNS is a distinct entity or if it represents a subtype of FND or OAVS [Evans et al., 2013].

The acrofrontofacionasal syndromes types 1 and 2 are ultra-rare conditions characterised by features of FND with postaxial synpolydactyly; type 1 is also associated with cleft lip/palate, while type 2 is associated with genitourinary anomalies such as hypospadias and bifid scrotum. Reported individuals have been born to consanguineous parents, and sibling recurrence supports autosomal recessive inheritance, although gonadal mosaicism cannot be totally excluded [Richieri-Costa et al., 1989; Guion-Almeida and Richieri-Costa, 2003; Chaabouni et al., 2008; Prontera et al., 2011].

In addition to the FND spectrum disorders that have been clinically defined as distinct groups, there are many cases that meet the minimal diagnostic criteria for FND but that do not clearly exhibit additional clinical features that allow definition of a distinct syndrome subclass. In many cases, the mode of inheritance for these conditions is uncertain, and in the absence of a molecular diagnosis, it is only possible to speculate on the existence of de novo or mosaic mutations or even environmental influences. The advent of massively parallel sequencing technology, in conjunction with careful clinical phenotyping, has provided major new insights into the aetiology of the FND spectrum disorders. Hopefully, in conjunction with an understanding of the developmental mechanisms resulting in defects of FNP, these new technologies will eventually lead to a molecular characterisation of this large undifferentiated FND group as well.

Conclusion

FND is a diverse collection of conditions sharing key features affecting the frontal cranial and midfacial skeleton. Ironically, while the core features of expanded skull vault and epicanthal distance combine to produce a relative increase in craniofacial volume, the underlying mechanisms driving the aberrant development of these structures are centred on loss and reduction of skeletal precursors and their derivatives. This phenomenon highlights the central role of the cranial and facial midline in uniting the complex architecture of the craniofacial skeleton. The FND spectrum disorders are fundamentally defects of cranial neural crest development and can therefore be considered as neurocristopathies. However, the diverse presentations of FND involve a range of other developmental systems, and in these respects, animal models have been invaluable in understanding the complex roles of specific FND genes in the development of FNP and other comorbid tissues.

The advent of genomic technology has resulted in a profound change in the way many, especially rare, genetic disorders are viewed by providing a molecular diagnosis and the mechanistic insights that follow on from gene identification. With the exception of ZSWIM6, which is yet to be functionally characterised, all the FND genes identified so far are bona fide, tissue-specific developmental regulators. FND is a defined group of disorders impacting on FNP. Is it really so surprising these disorders should be caused by tissue-specific factors? This contrasts with the growing collection of genes identified for mandibulofacial dysostoses which so far appear to be ubiquitously expressed and involved in core biochemical processes such as ribosome biogenesis and RNA splicing [Trainor and Andrews, 2013; Lehalle et al., 2015]. Mandibulofacial dysostoses, such as FND, are highly tissue-specific conditions, yet they are caused by mutations in genes that might be expected to produce very broad phenotypes. Both classes of craniofacial dysmorphology arise from defects in the cranial neural crest, albeit subtly different subpopulations. The implications for the majority of FND yet to be defined molecularly are unclear but highlight the need to be open to unexpected scenarios in the continuing search for the causes of craniofacial dysmorphology.

Disclosure Statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- 1.Abzhanov A, Protas M, Grant BR, Grant PR, Tabin CJ. Bmp4 and morphological variation of beaks in Darwin's finches. Science. 2004;305:1462–1465. doi: 10.1126/science.1098095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Altunoglu U, Satkın B, Uyguner ZO, Kayserili H. Mild nasal clefting may be predictive for ALX4 heterozygotes. Am J Med Genet A. 2014;164A:2054–2058. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.36578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ashique AM, Fu K, Richman JM. Endogenous bone morphogenetic proteins regulate outgrowth and epithelial survival during avian lip fusion. Development. 2002;129:4647–4660. doi: 10.1242/dev.129.19.4647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bertola DR, Rodrigues MG, Quaio CR, Kim CA, Passos-Bueno MR. Vertical transmission of a frontonasal phenotype caused by a novel ALX4 mutation. Am J Med Genet A. 2013;161A:600–604. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.35762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beverdam A, Meijlink F. Expression patterns of group-I aristaless-related genes during craniofacial and limb development. Mech Dev. 2001;107:163–167. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(01)00450-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Beverdam A, Brouwer A, Reijnen M, Korving J, Meijlink F. Severe nasal clefting and abnormal embryonic apoptosis in Alx3/Alx4 double mutant mice. Development. 2001;128:3975–3986. doi: 10.1242/dev.128.20.3975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bronner ME, LeDouarin NM. Development and evolution of the neural crest: an overview. Dev Biol. 2012;366:2–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2011.12.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chaabouni M, Maazoul F, Ben Hamida A, Berhouma M, Marrakchi Z, Chaabouni H. Autosomal recessive acro-fronto-facio-nasal dysostosis associated with genitourinary anomalies: a third case report. Am J Med Genet A. 2008;146A:1825–1827. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.32349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chai Y, Jiang X, Ito Y, Bringas P, Jr, Han J, et al. Fate of the mammalian cranial neural crest during tooth and mandibular morphogenesis. Development. 2000;127:1671–1679. doi: 10.1242/dev.127.8.1671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cohen MM., Jr Craniofrontonasal dysplasia. Birth Defects Orig Artic Ser. 1979;15:85–89. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Davy A, Bush JO, Soriano P. Inhibition of gap junction communication at ectopic Eph/ephrin boundaries underlies craniofrontonasal syndrome. PLoS Biol. 2006;4:e315. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0040315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dee CT, Szymoniuk CR, Mills PE, Takahashi T. Defective neural crest migration revealed by a Zebrafish model of Alx1-related frontonasal dysplasia. Hum Mol Genet. 2013;22:239–251. doi: 10.1093/hmg/dds423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.D'Elia AV, Tell G, Paron I, Pellizzari L, Lonigro R, Damante G. Missense mutations of human homeoboxes: a review. Hum Mut. 2001;18:361–374. doi: 10.1002/humu.1207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Devriendt K, Van Mol C, Fryns JP. Craniofrontonasal dysplasia: more severe expression in the mother than in her son. Genet Couns. 1995;6:361–364. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Evans KN, Gruss JS, Khanna PC, Cunningham ML, Cox TC, Hing AV. Oculoauriculofrontonasal syndrome: case series revealing new bony nasal anomalies in an old syndrome. Am J Med Genet A. 2013;161A:1345–1353. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.35926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Feldman GJ, Ward DE, Lajeunie-Renier E, Saavedra D, Robin NH, et al. A novel phenotypic pattern in X-linked inheritance: craniofrontonasal syndrome maps to Xp22. Hum Mol Genet. 1997;6:1937–1941. doi: 10.1093/hmg/6.11.1937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Florisson JM, Verkerk AJ, Huigh D, Hoogeboom AJ, Swagemakers S, et al. Boston type craniosynostosis: report of a second mutation in MSX2. Am J Med Genet A. 2013;161A:2626–2633. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.36126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fogelgren B, Kuroyama MC, McBratney-Owen B, Spence AA, Malahn LE, et al. Misexpression of Six2 is associated with heritable frontonasal dysplasia and renal hypoplasia in 3H1 Br mice. Dev Dyn. 2008;237:1767–1779. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.21587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Foppiano S, Hu D, Marcucio RS. Signaling by bone morphogenetic proteins directs formation of an ectodermal signaling center that regulates craniofacial development. Dev Biol. 2007;312:103–114. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2007.09.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gabbett MT, Robertson SP, Broadbent R, Aftimos S, Sachdev R, Nezarati MM. Characterizing the oculoauriculofrontonasal syndrome. Clin Dysmorphol. 2008;17:79–85. doi: 10.1097/MCD.0b013e3282f449c8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Grutzner E, Gorlin RJ. Craniofrontonasal dysplasia: phenotypic expression in females and males and genetic considerations. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Path. 1988;65:436–444. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(88)90358-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Guion-Almeida ML, Richieri-Costa A. Acrofrontofacionasal dysostosis: report of the third Brazilian family. Am J Med Genet A. 2003;119A:238–241. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.10444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Guion-Almeida ML, Richieri-Costa A. Frontonasal dysgenesis, first branchial arch anomalies, and pericallosal lipoma: a new subtype of frontonasal dysgenesis. Am J Med Genet A. 2010;152A:2039–2042. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.33485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.He G, Tavella S, Hanley KP, Self M, Oliver G, et al. Inactivation of Six2 in mouse identifies a novel genetic mechanism controlling development and growth of the cranial base. Dev Biol. 2010;344:720–730. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2010.05.509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hu D, R. Marcucio RS. A SHH-responsive signaling center in the forebrain regulates craniofacial morphogenesis via the facial ectoderm. Development. 2009a;136:107–116. doi: 10.1242/dev.026583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hu D, Marcucio RS. Unique organization of the frontonasal ectodermal zone in birds and mammals. Dev Biol. 2009b;325:200–210. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2008.10.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hu D, Marcucio RS, Helms JA. A zone of frontonasal ectoderm regulates patterning and growth in the face. Development. 2003;130:1749–1758. doi: 10.1242/dev.00397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hu D, Young NM, Li X, Xu Y, Hallgrímsson B, Marcucio RS. A dynamic Shh expression pattern, regulated by SHH and BMP signaling, coordinates fusion of primordia in the amniote face. Development. 2015;142:567–574. doi: 10.1242/dev.114835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hufnagel RB, Zimmerman SL, Krueger LA, Bender PL, Ahmed ZM, Saal HM. A new frontonasal dysplasia syndrome associated with deletion of the SIX2 gene. Am J Med Genet A. 2016;170A:487–491. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.37441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jabs EW, Müller U, Li X, Ma L, Luo W, et al. A mutation in the homeodomain of the human MSX2 gene in a family affected with autosomal dominant craniosynostosis. Cell. 1993;75:443–450. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90379-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jiang X, Iseki S, Maxson RE, Sucov HM, Morriss-Kay GM. Tissue origins and interactions in the mammalian skull vault. Dev Biol. 2002;241:106–116. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2001.0487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kariminejad A, Bozorgmehr B, Alizadeh H, Ghaderi-Sohi S, Toksoy G, et al. Skull defects, alopecia, hypertelorism, and notched alae nasi caused by homozygous ALX4 gene mutation. Am J Med Genet A. 2014;164A:1322–1327. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.36008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kayserili H, Uz E, Niessen C, Vargel I, Alanay Y, et al. ALX4 dysfunction disrupts craniofacial and epidermal development. Hum Mol Genet. 2009;18:4357–4366. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddp391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kayserili H, Altunoglu U, Ozgur H, Basaran S, Uyguner ZO. Mild nasal malformations and parietal foramina caused by homozygous ALX4 mutations. Am J Med Genet A. 2012;158A:236–244. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.34390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ke CY, Xiao WL, Chen CM, Lo LJ, Wong FH. IRF6 is the mediator of TGFβ3 during regulation of the epithelial mesenchymal transition and palatal fusion. Sci Rep. 2015;5:12791. doi: 10.1038/srep12791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Krull CE, Lansford R, Gale NW, Collazo A, Marcelle C, et al. Interactions of Eph-related receptors and ligands confer rostrocaudal pattern to trunk neural crest migration. Curr Biol. 1997;7:571–580. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(06)00256-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lan Y, Xu J, Jiang R. Cellular and molecular mechanisms of palatogenesis. Curr Top Dev Biol. 2015;115:59–84. doi: 10.1016/bs.ctdb.2015.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Le Douarin N. The Neural Crest. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Le Douarin NM. Piecing together the vertebrate skull. Development. 2012;139:4293–4296. doi: 10.1242/dev.085191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lehalle D, Wieczorek D, Zechi-Ceide RM, Passos-Bueno MR, Lyonnet S, et al. A review of craniofacial disorders caused by spliceosomal defects. Clin Genet. 2015;88:405–415. doi: 10.1111/cge.12596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lyons LA, Erdman CA, Grahn RA, Hamilton MJ, Carter MJ, et al. Aristaless-Like Homeobox protein 1 (ALX1) variant associated with craniofacial structure and frontonasal dysplasia in Burmese cats. Dev Biol. 2016;409:451–458. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2015.11.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ma L, Golden S, Wu L, Maxson R. The molecular basis of Boston-type craniosynostosis: the Pro148→His mutation in the N-terminal arm of the MSX2 homeodomain stabilizes DNA binding without altering nucleotide sequence preferences. Hum Mol Genet. 1996;5:1915–1920. doi: 10.1093/hmg/5.12.1915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Makarova KS, Aravind L, Koonin EV. SWIM, a novel Zn-chelating domain present in bacteria, archaea and eukaryotes. Trends Biochem Sci. 2002;27:384–386. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(02)02140-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mavrogiannis LA, Antonopoulou I, Baxová A, Kutílek S, Kim CA, et al. Haploinsufficiency of the human homeobox gene ALX4 causes skull ossification defects. Nat Genet. 2001;27:17–18. doi: 10.1038/83703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mavrogiannis LA, Taylor IB, Davies SJ, Ramos FJ, Olivares JL, Wilkie AO. Enlarged parietal foramina caused by mutations in the homeobox genes ALX4 and MSX2: from genotype to phenotype. Eur J Hum Genet. 2006;14:151–158. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5201526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.McBratney BM, Margaryan E, Ma W, Urban Z, Lozanoff S. Frontonasal dysplasia in 3H1 Br/Br mice. Anat Rec A Discov Mol Cell Evol Biol. 2003;271A:291–302. doi: 10.1002/ar.a.10034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mellitzer G, Xu Q, Wilkinson DG. Eph receptors and ephrins restrict cell intermingling and communication. Nature. 1999;400:77–81. doi: 10.1038/21907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Muthuswami R, Truman PA, Mesner LD, Hockensmith JW. A Eukaryotic SWI2/SNF2 domain, an exquisite detector of double-stranded to single-stranded DNA transition elements. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:7648–7655. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.11.7648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nichols DH. Neural crest formation in the head of the mouse embryo as observed using a new histological technique. J Embryol Exp Morphol. 1981;64:105–120. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Noden D, Evans H. Inhereted homeotic midfacial malformations in Burmese cats. J Craniofac Genet Dev Biol Suppl. 1986;2:249–266. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Oliver G, Wehr R, Jenkins NA, Copeland NG, Cheyette BN, et al. Homeobox genes and connective tissue patterning. Development. 1995;121:693–705. doi: 10.1242/dev.121.3.693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Prontera P, Urciuoli R, Siliquini S, Macone S, Stangoni G, et al. Acrofrontofacionasal dysostosis 1 in two sisters of Indian origin. Am J Med Genet A. 2011;155A:3125–3127. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.34295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Qu S, Niswender KD, Ji Q, van der Meer R, Keeney D, et al. Polydactyly and ectopic ZPA formation in Alx-4 mutant mice. Development. 1997;124:3999–4008. doi: 10.1242/dev.124.20.3999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Richieri-Costa A, Montagnoli L, Kamiya TY. Autosomal recessive acro-fronto-facio-nasal dysostosis associated with genitourinary anomalies. Am J Med Genet. 1989;33:121–124. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1320330118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Richieri-Costa A, Guion-Almeida ML, Pagnan NAB. Acro-fronto-facio-nasal dysostosis: report of a new Brazilian family. Am J Med Genet. 1992;44:800–802. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1320440616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Rieger MA, Duellman T, Hooper C, Ameka M, Bakowska JC, Cuevas BD. The MEKK1 SWIM domain is a novel substrate receptor for c-Jun ubiquitylation. Biochem J. 2012;445:431–439. doi: 10.1042/BJ20120406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Rollnick B, Day D, Tissot R, Kaye C. A pedigree possible evidence for the metabolic interference hypothesis. Am J Hum Genet. 1981;33:823–826. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sax CM, Flannery DB. Craniofrontonasal dysplasia: clinical and genetic analysis. Clin Genet. 1986;29:508–515. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.1986.tb00552.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sedano H, Gorlin R. Frontonasal malformation as a field defect and in syndromic associations. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol. 1988;65:704–710. doi: 10.1016/0030-4220(88)90014-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sedano HO, Cohen MM, Jr, Jirasek J, Gorlin RJ. Frontonasal dysplasia. J Pediatr. 1970;76:906–913. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(70)80374-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Slaney SF, Goodman FR, Eilers-Walsman BL, Hall BD, Williams DK, et al. Acromelic frontonasal dysostosis. Am J Med Genet. 1999;83:109–116. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Smith JD, Hing AV, Clarke CM, Johnson NM, Perez FA, et al. Exome sequencing identifies a recurrent de novo ZSWIM6 mutation associated with acromelic frontonasal dysostosis. Am J Hum Genet. 2014;95:235–240. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2014.07.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Spruijt L, Verdyck P, Van Hul W, Wuyts W, de Die-Smulders C. A novel mutation in the MSX2 gene in a family with foramina parietalia permagna (FPP) Am J Med Genet A. 2005;139:45–47. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.30923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Szabo-Rogers HL, Geetha-Loganathan P, Nimmagadda S, Fu KK, Richman JM. FGF signals from the nasal pit are necessary for normal facial morphogenesis. Dev Biol. 2008;318:289–302. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2008.03.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Taya Y, O'Kane S, Ferguson MW. Pathogenesis of cleft palate in TGF-beta3 knockout mice. Development. 1999;126:3869–3879. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.17.3869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Trainor PA, Andrews BT. Facial dysostoses: etiology, pathogenesis and management. Am J Med Genet C Semin Med Genet. 2013;163:283–294. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.c.31375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Twigg SR, Kan R, Babbs C, Bochukova EG, Robertson SP, et al. Mutations of ephrin-B1 (EFNB1), a marker of tissue boundary formation, cause craniofrontonasal syndrome. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:8652–8657. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0402819101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Twigg SR, Versnel SL, Nürnberg G, Lees MM, Bhat M, et al. Frontorhiny, a distinctive presentation of frontonasal dysplasia caused by recessive mutations in the ALX3 homeobox gene. Am J Hum Genet. 2009;84:698–705. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2009.04.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Twigg SR, Babbs C, van den Elzen ME, Goriely A, Taylor S, et al. Cellular interference in craniofrontonasal syndrome: males mosaic for mutations in the X-linked EFNB1 gene are more severely affected than true hemizygotes. Hum Mol Genet. 2013;22:1654–1662. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddt015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Twigg SR, Ousager LB, Miller KA, Zhou Y, Elalaoui SC, et al. Acromelic frontonasal dysostosis and ZSWIM6 mutation: phenotypic spectrum and mosaicism. Clin Genet. 2016;90:270–275. doi: 10.1111/cge.12721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ullah A, Kalsoom UE, Umair M, John P, Ansar M, et al. Exome sequencing revealed a novel splice site variant in the ALX1 gene underlying frontonasal dysplasia. Clin Genet. 2016 doi: 10.1111/cge.12822. E-pub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Uz E, Alanay Y, Aktas D, Vargel I, Gucer S, et al. Disruption of ALX1 causes extreme microphthalmia and severe facial clefting: expanding the spectrum of autosomal-recessive ALX-related frontonasal dysplasia. Am J Hum Genet. 2010;86:789–796. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2010.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.van den Elzen ME, Twigg SR, Goos JA, Hoogeboom AJ, van den Ouweland AM, et al. Phenotypes of craniofrontonasal syndrome in patients with a pathogenic mutation in EFNB1. Eur J Hum Genet. 2014;22:995–1001. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2013.273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Verloes A, Gillerot Y, Walczak E, Van Maldergem L, Koulischer L. Acromelic frontonasal ‘dysplasia’: further delineation of a subtype with brain malformation and polydactyly (Toriello syndrome) Am J Med Genet. 1992;42:180–183. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1320420209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Wieland I, Makarov R, Reardon W, Tinschert S, Goldenberg A, et al. Dissecting the molecular mechanisms in craniofrontonasal syndrome: differential mRNA expression of mutant EFNB1 and the cellular mosaic. Eur J Hum Genet. 2007;16:184–191. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5201968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Wilkie AO, Tang Z, Elanko N, Walsh S, Twigg SR, et al. Functional haploinsufficiency of the human homeobox gene MSX2 causes defects in skull ossification. Nat Genet. 2000;24:387–390. doi: 10.1038/74224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Wu P, Jiang TX, Suksaweang S, Widelitz RB, Chuong CM. Molecular shaping of the beak. Science. 2004;305:1465–1466. doi: 10.1126/science.1098109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Wuyts W, Cleiren E, Homfray T, Rasore-Quartino A, Vanhoenacker F, Van Hul W. The ALX4 homeobox gene is mutated in patients with ossification defects of the skull (foramina parietalia permagna, OMIM 168500) J Med Genet. 2000;37:916–920. doi: 10.1136/jmg.37.12.916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Xu X, Han J, Ito Y, Bringas P, Jr, Urata MM, Chai Y. Cell autonomous requirement for Tgfbr2 in the disappearance of medial edge epithelium during palatal fusion. Dev Biol. 2006;297:238–248. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Yagnik G, Ghuman A, Kim S, Stevens CG, Kimonis V, et al. ALX4 gain-of-function mutations in nonsyndromic craniosynostosis. Hum Mutat. 2012;33:1626–1629. doi: 10.1002/humu.22166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Zhang D, Ighaniyan S, Stathopoulos L, Rollo B, Landman K, et al. The neural crest: a versatile organ system. Birth Defects Res C Embryo Today. 2014;102:275–298. doi: 10.1002/bdrc.21081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Zhao Q, Behringer RR, de Crombrugghe B. Prenatal folic acid treatment suppresses acrania and meroanencephaly in mice mutant for the Cart1 homeobox gene. Nat Genet. 1996;13:275–283. doi: 10.1038/ng0796-275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]