Abstract

Background

α-Synuclein (αSYN) has been genetically implicated in familial and sporadic Parkinson’s disease (PD), and is associated with disease susceptibility, progression and pathology. Excess amounts of αSYN are toxic to neurons. In the brain, microglial αSYN clearance is closely related to neuronal survival. Leucine-rich repeat kinase 2 (LRRK2) is the one of the other genes implicated in familial and sporadic PD. While LRRK2 is known to be expressed in microglia, its true function remains to be elucidated. In this study, we investigated αSYN clearance by microglia isolated from LRRK2-knockout (KO) mice.

Results

In LRRK2-KO microglia, αSYN was taken up in larger amounts and cleared from the supernatant more effectively than for microglia isolated from wild-type (WT) mice. This higher clearance ability of LRRK2-KO microglia was thought to be due to an increase of Rab5-positive endosomes, but not Rab7- or Rab11-positive endosomes. Increased engagement between Rab5 and dynamin 1 was also observed in LRRK2-KO microglia.

Conclusion

LRRK2 negatively regulates the clearance of αSYN accompanied by down-regulation of the endocytosis pathway. Our findings reveal a new functional role of LRRK2 in microglia and offer a new insight into the mechanism of PD pathogenesis.

Keywords: Microglia, LRRK2, α-Synuclein

Background

α-Synuclein (αSYN; SNCA) is one of the key molecules involved in familial and sporadic Parkinson’s disease (PD) [1–5]; genomic multiplication and point mutations in the α-synuclein gene (SNCA) are known to be causal factors for the familial parkinsonism forms of PD, PARK1 and PARK4 [6–9]. αSYN comprises 140 amino acids, which form an amphipathic region, a NAC domain, and an acidic tail [10]. Because of the hydrophobicity of the NAC domain, αSYN easily forms toxic fibrillar structures, and an excess amount of αSYN induces cell death, eventually leading to PD [11–13]. αSYN is expressed in neurons, where it is involved in exocytosis in the presynaptic region [14, 15], and its transmission from cell to cell has been demonstrated [16–18]. These findings suggest that clearance of αSYN in the brain is crucially important for prevention of neuronal cell death.

Microglia are immune cells in the brain playing crucial roles in inflammatory responses, scavenging, and production of neurotropic factors [19]. Accumulated evidence indicates that microglia participate in the pathogenesis of various neurodegenerative diseases [20, 21]. In Alzheimer’s disease, β-amyloid stimulates microglia and induces the production of inflammatory cytokines [22]. Clearance of β-amyloid by microglia has a critical role in prevention of the disease [23, 24]. In PD, microglia are involved in both disease -prevention through clearance of αSYN and disease -progression through production of inflammatory cytokines in which the oligomeric αSYN stimulates toll-like receptor (TLR) 2 whereas a high amount of monomeric αSYN stimulates TLR4 [25–28]. Among the various types of brain cells, microglia are known to have the highest ability to degrade αSYN [29]. One study using mice overexpressing αSYN has shown that acceleration of microglial clearance through αSYN opsonization ameliorated the degree of neurodegeneration [30]. It is believed that achieving adequate degradation of αSYN might be a new therapeutic approach for diseases characterized by pathological accumulation of αSYN [31, 32].

Leucine-rich repeat kinase 2 (LRRK2) is the gene responsible for autosomal-dominant PD, PARK8, which was originally defined by linkage analysis of a Japanese family (the Sagamihara family) [33–36]. LRRK2 is a complex kinase consisting of LRR, ROC, COR, kinase, and WD40 domains [37]. Accumulated evidence suggests that LRRK2 plays a key role in axonal extension, autophagy, proliferation, and survival of neurons [38, 39]. In addition to neurons, LRRK2 is highly expressed in immune cells such as B cells, macrophages, and microglia [40–43]. Several studies have demonstrated that LRRK2 is related to inflammatory responses of microglia that could be involved in the development and progression of neurodegeneration [44, 45]. It has been reported that pathological mutations of LRRK2 lead to increased production of inflammatory cytokines [46].

With regard to the association between LRRK2 and αSYN, it has been reported that LRRK2 knockout (KO) attenuates the neuropathology that is induced by αSYN overexpression in mouse brain through a delay of neuronal death resulting from improved structure and function of the Golgi complex [47]. Another study has demonstrated that LRRK2-KO ameliorated neurodegeneration in αSYN-overexpressing rats by inhibiting the recruitment of chronically activated proinflammatory myeloid cells [48]. Although these studies suggest an association between LRRK2 and the neuropathology caused by αSYN, no study has yet addressed how microglial LRRK2 is involved in αSYN clearance.

In the present study, we analyzed microglia treated with αSYN and revealed a new functional role of microglial LRRK2. Our results indicate that LRRK2 acts as a negative regulator of αSYN clearance.

Results

LRRK2 is a negative regulator of αSYN clearance in microglia

To investigate the function of microglial LRRK2, primary microglia were prepared from LRRK2-KO mice and littermate WT control mice by Ni’s method [49]. Immunostaining with antibodies against Iba-1 (a microglial marker) and GFAP (an astroglial marker) revealed that the purity of the microglia was about 92%. No morphological differences in tomato lectin staining were observed between KO and WT microglia (Fig. 1a), and the MTT assay demonstrated no difference in viability between KO and WT microglia (Fig. 1b). Furthermore, the phagocytotic activities of KO and WT microglia did not differ from each other when analyzed using fluorescent latex beads (Fig. 1c). These results indicated that LRRK2 is not related to these microglial phenotypes. For evaluation of αSYN clearance, we performed αSYN uptake and clearance assay using recombinant αSYN. The αSYN treatment did not alter the protein level of LRRK2 (250 kDa) in WT primary microglia (Fig. 2a). Importantly, αSYN bands were detected only in the groups that had been treated with recombinant αSYN, indicating that the detected bands were not endogenous but exogenous recombinant αSYN. It was noteworthy that more αSYN was taken up by KO microglia than by WT microglia (Fig. 2b). The results were confirmed using different anti-αSYN and anti-GAPDH antibodies (Fig. 2c, d). Measurement of αSYN clearance showed that the level of residual αSYN in the culture medium of KO microglia was decreased more prominently than that in the medium of WT microglia (Fig. 2e). These results indicated that αSYN clearance by LRRK2-KO microglia is higher than that by WT microglia, suggesting that LRRK2 is a negative regulator of αSYN clearance in microglia.

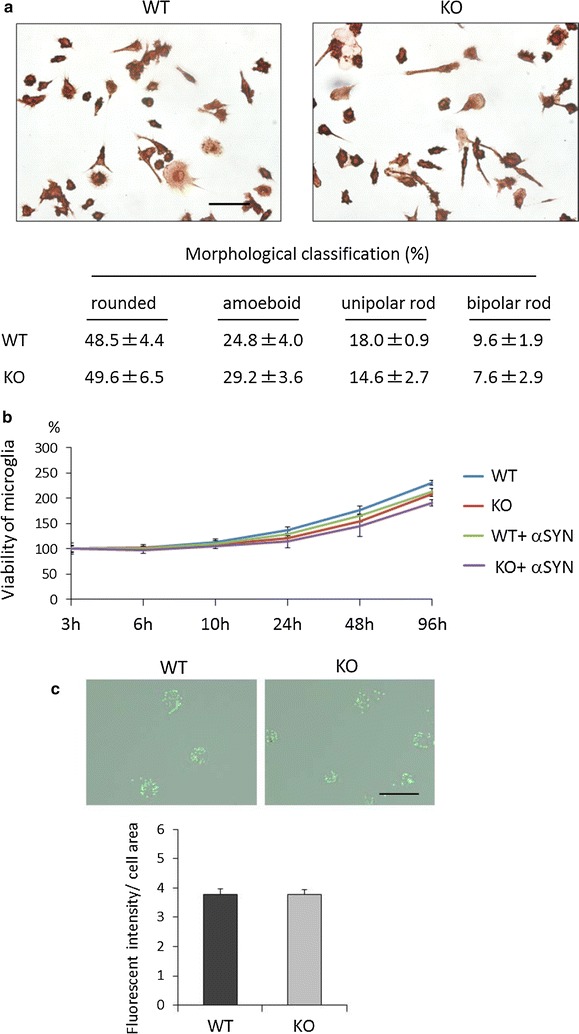

Fig. 1.

Characterization of LRRK2-KO microglia. a Tomato lectin staining of LRRK2-KO and WT microglia. One hundred cells were counted per culture well. n = 3 culture wells per group. Scale bar 50 μm. b MTT assay for evaluating the viability of LRRK2-KO and WT microglia in the absence or presence of αSYN. The data represent percentage viability relative to culture day 0, and were assessed by ANOVA at each time point (3 h: F = 0.26, p = 0.852; 6 h: F = 1.26, p = 0.351; 10 h: F = 0.94, p = 0.465; 24 h: F = 3.61, p = 0.065; 48 h: F = 2.55, p = 0.129; and 96 h: F = 3.46, p = 0.071). n = 3 culture wells per group. c Phagocytosis assay using FITC-microbeads. Upper panel shows an image of microbead phagocytosis. Scale bar 50 μm. Lower panel shows the fluorescence intensity of microbeads taken up by microglia. Forty cells were analyzed per group. The data are expressed as mean ± SD and were assessed by Student’s t test. These experiments were carried out three times using independent primary microglia isolated from different mice, and a representative image and data are shown

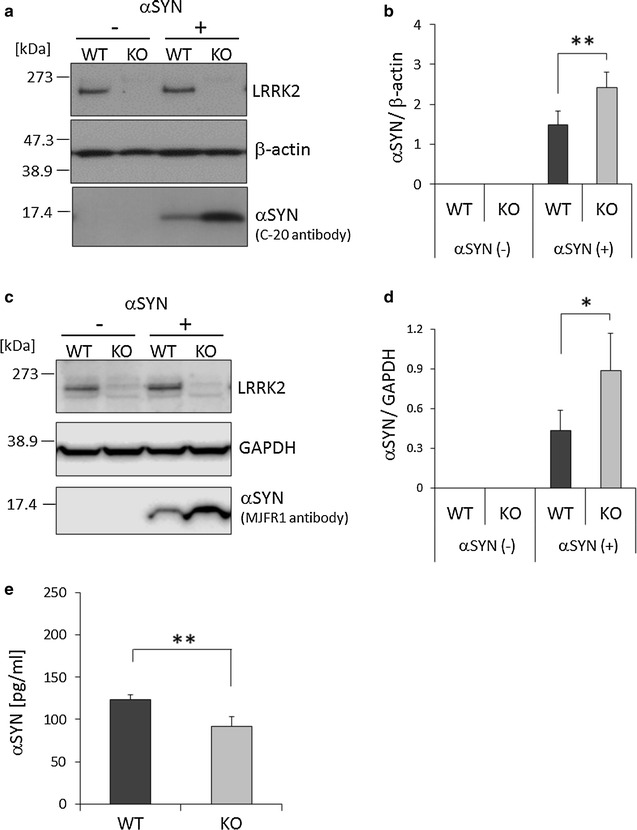

Fig. 2.

Increased αSYN uptake and degradation by LRRK2 KO microglia. a Western analysis of LRRK2-KO microglia treated with αSYN. Lysates were prepared from LRRK2- KO and WT microglia treated with or without αSYN and subjected to Western analysis using anti-LRRK2, β-actin, and αSYN (C-20) antibodies. b Quantified density of αSYN bands in (a) normalized by the density of β-actin. n = 4 culture wells per group. c Western analysis using anti-LRRK2, GAPDH, and αSYN (MJFR1) antibodies. d Quantified density of αSYN bands in (c) normalized by the density of GAPDH. n = 4 culture wells per group. e Residual αSYN in the culture media of WT and KO microglia. n = 8 culture wells per group. The amounts of αSYN were measured by ELISA 48 h after αSYN treatment. In all graphical representations, data are expressed as mean ± SD and were assessed by Student’s t test (KO vs. WT); *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01. All experiments were carried out three times using primary microglia isolated from independent mice, and a representative image and data are shown

LRRK2 regulates endocytotic αSYN uptake

It has been reported that αSYN is internalized through the endocytotic pathway [50]. On the other hand, LRRK2 is associated with Rab5, a member of the Ras superfamily of small Rab GTPases and a component of the early endosome [51, 52]. To elucidate whether LRRK2 regulates endocytotic αSYN clearance through early endosomes, WT and KO microglia treated with recombinant αSYN were subjected to immunostaining with anti-αSYN and anti-Rab5 antibodies. Internalized αSYN was visualized as small particles spread widely in the all cell, and in keeping with the results of Western analysis, KO microglia showed higher amount of αSYN than WT microglia (Fig. 3a). Immunostaining for Rab5 demonstrated a pattern similar to that of αSYN. Interestingly, Rab5-positive early endosomes were obviously increased in KO microglia relative to WT microglia. Furthermore, as reported previously [53], some of the αSYN taken up was co-localized with Rab5-positive early endosomes. Relative assessment of co-localization between αSYN and Rab5 revealed that the Rcoloc value for KO microglia was higher than that for WT microglia (Fig. 3b, c). These results suggested that the increased uptake of αSYN by LRRK2-KO microglia is associated with an increase of early endosomes, i.e. LRRK2 is a down-regulator of the endocytotic pathway.

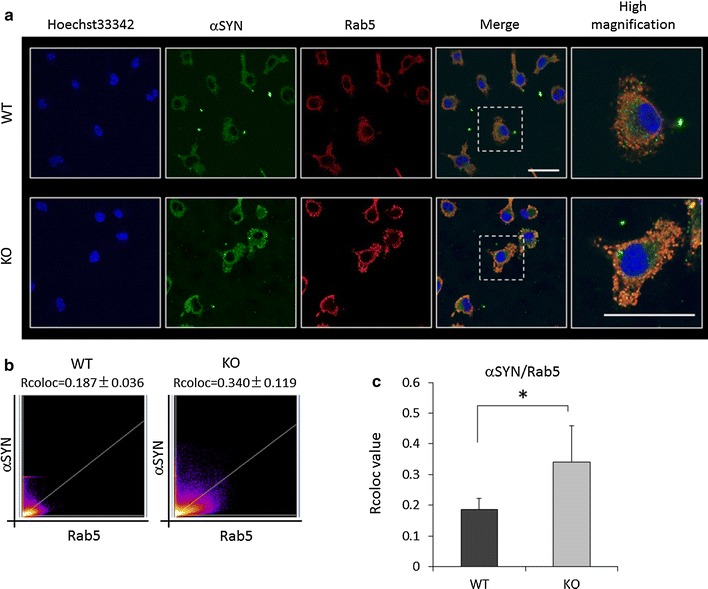

Fig. 3.

Increment of endocytotic αSYN uptake by LRRK2-KO microglia. a Confocal immunostaining images of αSYN and Rab5 in KO and WT microglia. Scale bar 50 μm. Higher-magnification views of the boxed area show the detail of immunopositive particles. Scale bar 20 μm. b Cytofluorograms for αSYN and Rab5 immunostaining evaluated using the high magnification views of KO and WT microglia. c The αSYN/Rab5 correlation coefficient (Rcoloc) values for KO and WT microglia. Ten cells were randomly chosen per group. In all graphical representations, data are expressed as mean ± SD and were assessed by Student’s t test; *p < 0.05. The experiment was carried out three times using primary microglia isolated from independent mice, and a representative image and data are shown

Early endosomes are selectively increased in LRRK2-KO microglia

To investigate whether there is any abnormality in other components of the endosomal-lysosomal pathway in KO microglia, lysosomes were analyzed by immunostaining with anti-LAMP1 antibody (a lysosome marker) and a pH-sensitive molecular probe (a functional lysosome marker). In both analyses, the fluorescence intensities did not differ from that of WT microglia (Fig. 4a), indicating that the structure and function of the lysosome system were not altered in LRRK2-KO microglia. Immunostaining of the early endosome, late endosome, and recycling endosome using antibodies against the marker molecules Rab5, 7, and 11, respectively, revealed that the fluorescence intensity of Rab5-positive endosomes, but not that of Rab7- or 11-positive endosomes, was significantly increased in KO microglia relative to WT microglia (Fig. 4b). The increment of early endosomes in KO microglia was also confirmed by using CellLight (Fig. 4c).

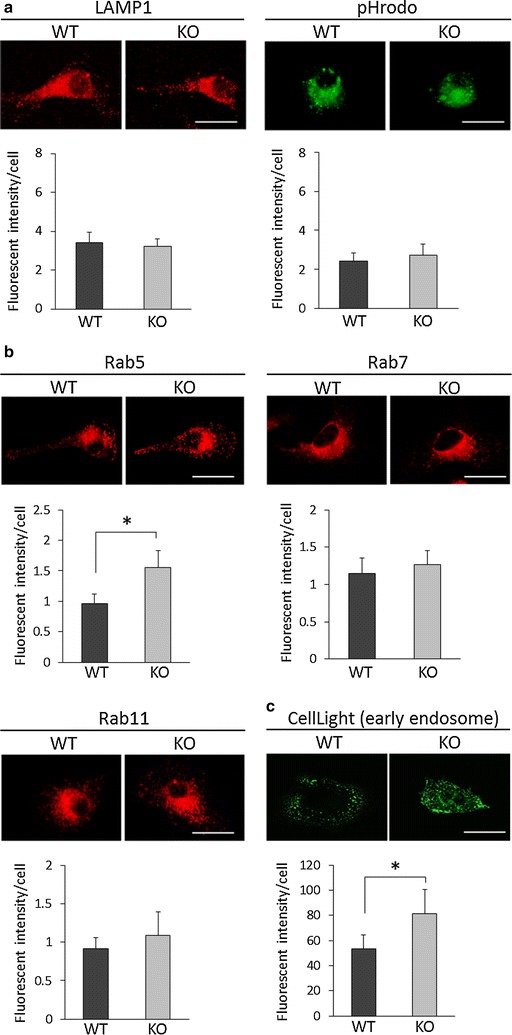

Fig. 4.

Increase of early endosomes, but not lysosomes, late, or recycling endosomes, in LRRK2-KO microglia. a Immunostaining for lysosomal markers in KO and WT microglia. Lysosomes and acidic lysosomes were visualized using anti-LAMP1 and pHrodo, respectively. b Immunostaining for endosomal markers in KO and WT microglia. Early endosomes, late endosomes, and recycling endosomes were visualized using antibodies against Rab5, Rab7 and Rab11, respectively. Scale bar 20 μm. Quantification of fluorescence intensity per cell showing an increase of Rab5-positive endosomes, but not Rab7- and Rab11-positive particles, in KO microglia. Twenty-five cells were analyzed per group. c Visualization of early endosomes using CellLight. Twenty-five cells were analyzed per group. In the graphical representation, data are expressed as mean ± SD and were assessed by Student’s t test; *p < 0.05. All experiments were carried out three times using primary microglia isolated from independent mice, and a representative image and data are shown

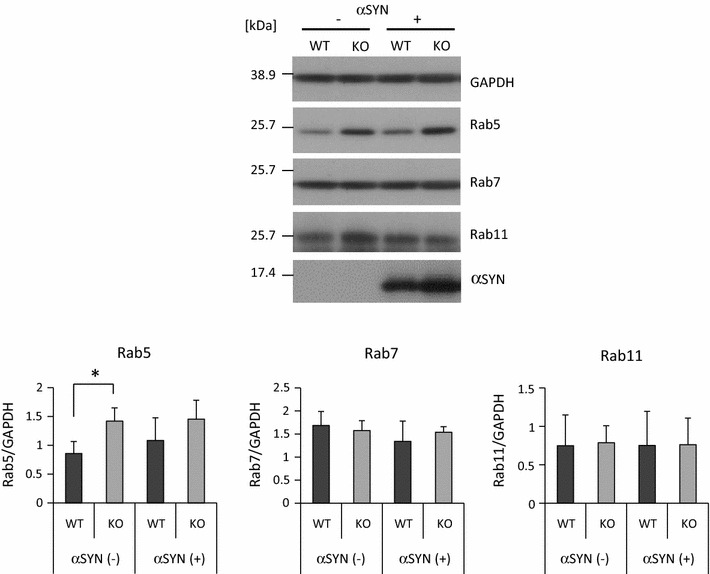

Western analysis using the same antibodies confirmed that the level of Rab5 protein was higher in KO microglia than in WT microglia (Fig. 5). After treatment with recombinant αSYN, an increase in the level of Rab5 protein in KO microglia, although not statistically significant, was also observed. These results indicated that early endosomes, but not other endosomes or lysosomes, are increased in LRRK2-KO microglia.

Fig. 5.

Higher Rab5 protein level in KO microglia than in WT microglia. Western analysis was performed to determine the protein levels of Rab5, Rab7 and Rab11 in KO and WT microglia treated with or without αSYN. The quantified density of each Rab was normalized by the density of GAPDH. n = 4 culture wells per group. In all graphical representations, data are expressed as mean ± SD and were assessed by ANOVA (KO vs WT). Rab5: F = 4.28, p = 0.028; Rab7: F = 0.96, p = 0.443; and Rab11: F = 0.01, p = 0.999. The experiment was carried out three times using primary microglia isolated from independent mice, and a representative image and data are shown

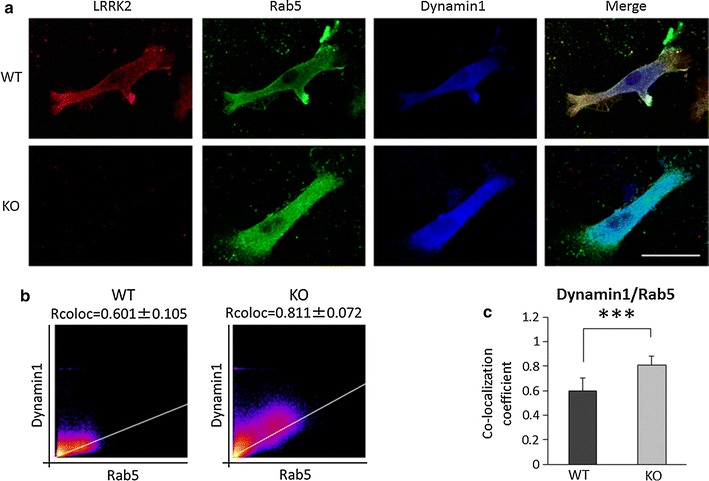

LRRK2 controls the primary endocytotic process in microglia

Recently, LRRK2 has been reported to associate with dynamin 1 in SH-SY5Y neuronal cells [54]. Dynamin 1 is one of the dynamin GTPase superfamily of molecules that modulate fission of the cytoplasmic membrane in the endocytosis pathway. To investigate how LRRK2 knockout affects dynamin 1, triple immunofluorescence staining with anti-LRRK2, anti-Rab5, and anti-dynamin1 antibodies was performed on KO and WT microglia. All staining was visualized as particles, and co-localization among LRRK2, Rab5, and dynamin1 was observed in primary microglia (Fig. 6a), in accordance with the previous study conducted using SH-SY5Y cells. Analysis of relative staining intensity showed that the Rcoloc value for Rab5 and dynamin 1 was increased in LRRK2-KO microglia relative to WT microglia (Fig. 6b, c). These results indicated that LRRK2 down-regulates the coordination between Rab5 and dynamin 1, resulting in reduced production of early endosomes.

Fig. 6.

Increased co-localization between Rab5 and dynamin 1 in LRRK2-KO microglia. a Comparison of co-localization of Rab5 and dynamin 1 between KO and WT microglia. Confocal immunostaining images show LRRK2-, Rab5-, and dynamin1-immunopositive particles in the KO and WT microglia. Scale bar 10 μm. b Cytofluorograms of dynamin 1 and Rab5 immunostaining in KO and WT microglia. c The Rcoloc values of dynamin1/Rab5 in KO and WT microglia. Ten cells were analyzed per group. In the graphical representation, data are expressed as mean ± SD and were assessed by Student’s t test; ***p < 0.005. All experiments were carried out three times using primary microglia isolated from independent mice, and a representative image and data are shown

Discussion

In the present study, we clarified for the first time the role of LRRK2 in the process of αSYN clearance in microglia. Primary microglia isolated from LRRK2-KO mice exhibited increased uptake and clearance of αSYN and an increased immunostaining of Rab5-positive early endosomes, but not other endosomes or lysosomes. KO microglia also showed an increased degree of co-localization between Rab5 and dynamin 1. This study provides the first evidence that LRRK2 in microglia has a negative regulatory role in αSYN clearance by the early endocytosis pathway.

Because LRRK2-KO microglia showed up-regulation of the endocytosis pathway in both the presence and absence of recombinant αSYN, i.e., independently of exogenous αSYN, it is likely that autonomous up-regulation of endocytosis in LRRK2-KO microglia is one of the mechanisms for the increment of αSYN uptake and clearance. A recent study has reported that Rab5b, an isoform of Rab5, is phosphorylated by LRRK2 at Thr 6, resulting in a decreased endocytosis rate in Hela cells [55]. It is possible that up-regulation of the endocytosis rate in KO microglia could be due to the lack of phosphorylation of Rab5b. Our findings also suggested that enhancement of the coordination between Rab5 and dynamin 1 is another mechanism for the up-regulation of Rab5-positive early endosomes. It has been shown that G2019S-mutant LRRK2 with higher kinase activity inhibits the co-localization between Rab5 and dynamin 1 [54]. Given that the kinase activity of LRRK2 down-regulates the co-localization between Rab5 and dynamin 1, knockout of LRRK2 may enhance their co-localization and lead to an increase of Rab5-positive early endosomes. As an another possible mechanism, LRRK2 may regulate the amount of the Rab5 molecule itself. It has been reported that macrophages of the LRRK2-KO mouse exhibit an increase of IL-6 production through increased nuclear translocation of NFAT [43]. Because IL-6 is known to increase Rab5, but not other Rabs [56], it is possible that the elevated level of IL-6 in KO microglia may selectively increase Rab5-positive early endosomes and consequently promote the coordination between Rab5 and dynamin 1.

In contrast to our study, it has recently been reported that the protein level of αSYN was comparable between LRRK2-KO and WT rats that overexpress αSYN after viral transfection [48]. It is possible that the amount of virally overexpressed αSYN might far exceed the capacity of microglia to clear it. LRRK2 KO has also been reported to abrogate the neurodegeneration induced by αSYN overexpression in this strain of rat. It is possible that a decreased inflammatory response resulting from lack of LRRK2, rather than up-regulated αSYN clearance, might be responsible for this alleviation of neurodegeneration.

It has been shown that an excess amount of αSYN induces neuronal death [11–13], and that continuity of this process will eventually cause PD [57]. Because αSYN is known to be transmitted from cell to cell, and microglia have the highest ability to clear it [16–18, 29], αSYN clearance by microglia, in addition to that by neurons themselves, would be of crucial importance for maintaining a healthy brain environment.

Conclusions

We have demonstrated that LRRK2 in microglia may function as the offending molecule responsible for neurodegeneration, in terms of down-regulation of αSYN clearance. In other words, inhibition of LRRK2 would be a potential therapeutic approach for PD.

Methods

Animals

LRRK2 exon 41-KO mice, developed by Hinkle and co-workers [58], on C57BL/6 J and littermate wild-type (WT) mice were used. The mice were housed in a light- and temperature-controlled room with water and food available ad libitum. For sacrifice, mice were euthanatized by cervical dislocation or exsanguination. All procedures had been approved by the Animal Experimentation and Ethics Committee of Kitasato University.

Antibodies

The following primary antibodies were used: rabbit polyclonal anti-α-synuclein antibody (C-20, Santa Cruz Biotechnology), rabbit monoclonal anti-α-synuclein antibody (MJFR1, Abcam), mouse monoclonal anti-α-synuclein antibody (4D6, Abcam), rabbit monoclonal anti-LRRK2 antibody (MJFF2, Epitomics), rabbit polyclonal anti-Iba-1 antibody (Wako), horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-labeled mouse monoclonal anti-β-actin antibody (ab20272, Abcam), rabbit monoclonal anti-glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase antibody (GAPDH; 14C10, Cell Signaling Technology), mouse monoclonal glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) antibody (2A5, Abcam), mouse monoclonal anti-Rab5 antibody (Rab5-65, Abcam), rabbit monoclonal anti-Rab5 antibody (C8B1, Cell Signaling Technology), rabbit monoclonal anti-Rab7 antibody (D95F2, Cell Signaling Technology), rabbit monoclonal anti-Rab11 antibody (D4F5, Cell Signaling Technology), and mouse monoclonal anti-LAMP1 antibody (H4A3, Abcam).

Isolation of primary microglia

Primary microglia isolation was performed according to the method of Ni [49]. Briefly, neonatal brains were obtained from WT and LRRK2-KO mice at 2 days of birth, then cortex sections were dissected out under a microscope and digested with papain for 20 min at 37 °C. The dispersed cells were suspended in growth medium (DMEM; Sigma, 10% FCS; Gibco, penicillin/streptomycin) and cultured at 40,000 viable cells/cm2. After mixed glial cells had become 100% confluent (about 10 days after plating), the culture flask was tapped gently until most of the microglia became detached. The isolated microglia were then cultured in growth medium at 10,000 viable cells/cm2 on poly-l-lysine (Sigma)-coated cover slips or in 24-well plastic tissue culture plates. The cells were used for experiments two days after plating. The purity of the microglia was about 92% when determined by immunostaining with the anti-Iba-1 antibody and anti-GFAP antibody.

Measurement of αSYN uptake

Primary microglia were treated with 5 μg/ml recombinant αSYN [γ-peptide] for 24 h. Uptake of recombinant αSYN was analyzed by Western analysis and immunofluorescence staining using the anti-αSYN antibody.

Measurement of αSYN clearance

Primary microglia were treated with 250 pg/ml recombinant αSYN for 48 h. After incubation, the level of residual αSYN in the culture medium was measured with a SensoLyte™ Anti-alpha-Synuclein Quantitative ELISA Kit (Anaspec) in accordance with the manufacturer’s protocol.

Western blotting

Microglia were lysed in TNE buffer [10 mM Tris–HCl buffer (pH 7.6) containing 150 mM NaCl, 1% Nonidet P-40, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, and protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche)] and incubated at 4 °C for 1 h. The cell lysate was obtained by centrifugation at 13,000 rpm for 15 min at 4 °C, then subjected to sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) using 5–20% gradient e-PAGEL (ATTO), and blotted onto polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membranes. The membranes were blocked in 2% skim milk in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS)—0.1% Tween 20 for 60 min at room temperature, and then probed with the appropriate primary antibodies for 24 h at 4 °C. After incubation with secondary antibodies for 30 min at room temperature, protein bands were visualized using an ECL Western Blotting Detection Kit (GE Healthcare). The intensity of the protein bands was analyzed using NIH ImageJ software (http://rsbweb.nih.gov/ij/).

Tomato lectin staining

Primary microglia attached to cover slips were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 30 min at room temperature and reacted with biotin-conjugated tomato lectin (Vector Laboratories) for 30 min at room temperature. Avidin/biotinylated HRP complex and ImmPACT DAB Substrate (Vector Laboratories) were used for detection.

Immunofluorescence staining

After treatment with 2% BSA in PBS—0.2% Triton X-100 for 60 min at room temperature to block non-specific binding, the fixed microglia were incubated with primary antibodies for 24 h at 4 °C, and subsequently with appropriate secondary antibodies for 30 min at room temperature. Nuclear staining was performed with 2′-(4-ethoxyphenyl)-5-(4-methyl-1-piperazinyl)-2,5′-bi-1H-benzimidazole (Hoechst 33342, Dojindo). Visualization of early endosomes using CellLight Early Endosomes-GFP (Molecular probes) was conducted according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Fluorescent signals were observed using a Nikon C2 Si confocal microscope system using 525–575, 595–635, and 445–475 nm band pass filter to obtain the signal by 488 nm-, 561 nm-, and UV-laser excitation, respectively. Pearson’s correlation coefficient (Rcoloc) value was given by Coloc 2-plugin in ImageJ for each cell.

3-(4,5-Dimethylthiazol-2-yl) 2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) assay

The culture supernatants of primary microglia cultured for 1, 3, 6, 12, 24, and 48 h with or without recombinant αSYN were assayed for viability using a Cell Counting Kit-8™ (Dojindo) in accordance with the manufacturer’s protocol.

Phagocytosis assay

Primary microglia were incubated with fluorescent latex beads (0.0025%, Sigma) for 1 h. The cells were washed with PBS, fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde, and mounted on glass slides using ProLong® Gold antifade reagent (Molecular Probes). Fluorescence intensity per cell was determined using ImageJ software.

Statistical analysis

All data are expressed as mean ± S.D. Significance of differences was assessed by Student’s t test for two comparisons and one-way ANOVA for multiple comparisons.

Authors’ contributions

TM performed the experiments with support from TS, SA, and TI. HM and MF provided animal. TM designed the study and wrote the manuscript with support from FO. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

We thank Mr. T. Hoshino and Miss A. Ozawa for technical assistance in the isolation of microglia.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Availability of data and materials

The key data supporting the conclusions of this article are included within the article. The raw datasets used in the study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Ethics approval

All animal studies had been approved by the Animal Experimentation and Ethics Committee of Kitasato University. (Reference Number; 2014: 14–38, 2015: 15–32, 2016: 16–25).

Funding

This study was supported by JSPS KAKENHI Grant Number 25860720, a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research on Innovative Areas (Comprehensive Brain Science Network) from the Ministry of Education, Science, Sports and Culture of Japan, Kitasato University Research Grant for Young Researchers, and the Kitasato University School of Allied Health Sciences (Grant-in-Aid for Research Project 2013–2014).

Abbreviations

- αSYN

α-synuclein

- GAPDH

glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase

- GFAP

monoclonal glial fibrillary acidic protein

- KO

knockout

- LRRK2

leucine-rich repeat kinase 2

- MTT assay

3-[4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl]-2,5 diphenyl tetrazolium bromide assay

- PBS

phosphate-buffered saline

- PD

Parkinson’s disease

- PVDF

polyvinylidene fluoride

- SDS-PAGE

sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis

- TLR

toll-like receptor

- WT

wild-type

Contributor Information

Tatsunori Maekawa, Phone: +08-42-778-9487, Email: maekawa@kitasato-u.ac.jp.

Toshikuni Sasaoka, Email: sasaoka@bri.niigata-u.ac.jp.

Sadahiro Azuma, Email: sazuma@med.kitasato-u.ac.jp.

Takafumi Ichikawa, Email: t.ichika@kitasato-u.ac.jp.

Heather L. Melrose, Email: Melrose.heather@mayo.edu

Matthew J. Farrer, Email: mfarrer@can.ubc.ca

Fumiya Obata, Email: obata@ahs.kitasato-u.ac.jp.

References

- 1.Bendor JT, Logan TP, Edwards RH. The function of α-synuclein. Neuron. 2013;79:1044–1066. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2013.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Goedert M, Spillantini MG, Del Tredici K, Braak H. 100 Years of Lewy pathology. Nat Rev Neurol. 2013;9:13–24. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2012.242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mullin S, Schapira A. α-Synuclein and mitochondrial dysfunction in Parkinson’s disease. Mol Neurobiol. 2013;47:587–597. doi: 10.1007/s12035-013-8394-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Olanow CW, Brundin P. Parkinson’s disease and alpha synuclein: is Parkinson’s disease a prion-like disorder? Mov Disord. 2013;28:31–40. doi: 10.1002/mds.25373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nalls MA, Pankratz N, Lill CM, Do CB, Hernandez DG, Saad M, DeStefano AL, Kara E, Bras J, Sharma M, Schulte C, Keller MF, Arepalli S, Letson C, Edsall C, Stefansson H, Liu X, Pliner H, Lee JH, Cheng R; International Parkinson’s Disease Genomics Consortium (IPDGC); Parkinson’s Study Group (PSG) Parkinson’s Research: The Organized GENetics Initiative (PROGENI); 23andMe; GenePD; NeuroGenetics Research Consortium (NGRC); Hussman Institute of Human Genomics (HIHG); Ashkenazi Jewish Dataset Investigator; Cohorts for Health and Aging Research in Genetic Epidemiology (CHARGE); North American Brain Expression Consortium (NABEC); United Kingdom Brain Expression Consortium (UKBEC); Greek Parkinson’s Disease Consortium; Alzheimer Genetic Analysis Group, Ikram MA, Ioannidis JP, Hadjigeorgiou GM, Bis JC, Martinez M, Perlmutter JS, Goate A, Marder K, Fiske B, Sutherland M, Xiromerisiou G, Myers RH, Clark LN, Stefansson K, Hardy JA, Heutink P, Chen H, Wood NW, Houlden H, Payami H, Brice A, Scott WK, Gasser T, Bertram L, Eriksson N, Foroud T, Singleton AB. Large-scale meta-analysis of genome-wide association data identifies six new risk loci for Parkinson’s disease. Nat Genet 2014, 46: 989–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Goedert M. Familial Parkinson’s disease. The awakening of alpha-synuclein. Nature. 1997;388:232–233. doi: 10.1038/40767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Polymeropoulos MH, Lavedan C, Leroy E, Ide SE, Dehejia A, Dutra A, Pike B, Root H, Rubenstein J, Boyer R, Stenroos ES, Chandrasekharappa S, Athanassiadou A, Papapetropoulos T, Johnson WG, Lazzarini AM, Duvoisin RC, Di Iorio G, Golbe LI, Nussbaum RL. Mutation in the alpha-synuclein gene identified in families with Parkinson’s disease. Science. 1997;276:2045–2047. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5321.2045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Farrer M, Kachergus J, Forno L, Lincoln S, Wang DS, Hulihan M, Maraganore D, Gwinn-Hardy K, Wszolek Z, Dickson D, Langston JW. Comparison of kindreds with parkinsonism and alpha-synuclein genomic multiplications. Ann Neurol. 2004;55:174–179. doi: 10.1002/ana.10846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Trinh J, Guella I, Farrer MJ. Disease penetrance of late-onset parkinsonism: a meta-analysis. JAMA Neurol. 2014;71:1535–1539. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2014.1909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jo E, McLaurin J, Yip CM, St George-Hyslop P, Fraser PE. Alpha-synuclein membrane interactions and lipid specificity. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:34328–34334. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M004345200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Narhi L, Wood SJ, Steavenson S, Jiang Y, Wu GM, Anafi D, Kaufman SA, Martin F, Sitney K, Denis P, Louis JC, Wypych J, Biere AL, Citron M. Both familial Parkinson’s disease mutations accelerate alpha-synuclein aggregation. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:9843–9846. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.14.9843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Saha AR, Ninkina NN, Hanger DP, Anderton BH, Davies AM, Buchman VL. Induction of neuronal death by alpha-synuclein. Eur J Neurosci. 2000;12:3073–3077. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2000.00210.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhou W, Hurlbert MS, Schaack J, Prasad KN, Freed CR. Overexpression of human alpha-synuclein causes dopamine neuron death in rat primary culture and immortalized mesencephalon-derived cells. Brain Res. 2000;66:33–43. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(00)02215-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Snead D, Eliezer D. Alpha-synuclein function and dysfunction on cellular membranes. Exp Neurobiol. 2014;23:292–313. doi: 10.5607/en.2014.23.4.292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vargas KJ, Makani S, Davis T, Westphal CH, Castillo PE, Chandra SS. Synucleins regulate the kinetics of synaptic vesicle endocytosis. J Neurosci. 2014;34:9364–9376. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4787-13.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kordower JH, Chu Y, Hauser RA, Freeman TB, Olanow CW. Lewy body-like pathology in long-term embryonic nigral transplants in Parkinson’s disease. Nat Med. 2008;14:504–506. doi: 10.1038/nm1747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li JY, Englund E, Holton JL, Soulet D, Hagell P, Lees AJ, Lashley T, Quinn NP, Rehncrona S, Björklund A, Widner H, Revesz T, Lindvall O, Brundin P. Lewy bodies in grafted neurons in subjects with Parkinson’s disease suggest host-to-graft disease propagation. Nat Med. 2008;14:501–503. doi: 10.1038/nm1746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pacheco C, Aguayo LG, Opazo C. An extracellular mechanism that can explain the neurotoxic effects of α-synuclein aggregates in the brain. Front Physiol. 2012;3:297. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2012.00297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lyman M, Lloyd DG, Ji X, Vizcaychipi MP, Ma D. Neuroinflammation: the role and consequences. Neurosci Res. 2014;79:1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.neures.2013.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cunningham C. Microglia and neurodegeneration: the role of systemic inflammation. Glia. 2013;61:71–90. doi: 10.1002/glia.22350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.González H, Elgueta D, Montoya A, Pacheco R. Neuroimmune regulation of microglial activity involved in neuroinflammation and neurodegenerative diseases. J Neuroimmunol. 2014;274:1–13. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2014.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Michelucci A, Heurtaux T, Grandbarbe L, Morga E, Heuschling P. Characterization of the microglial phenotype under specific pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory conditions: effects of oligomeric and fibrillar amyloid-beta. J Neuroimmunol. 2009;210:3–12. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2009.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mandrekar S, Jiang Q, Lee CY, Koenigsknecht-Talboo J, Holtzman DM, Landreth GE. Microglia mediate the clearance of soluble Abeta through fluid phase macropinocytosis. J Neurosci. 2009;29:4252–4262. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5572-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pan XD, Zhu YG, Lin N, Zhang J, Ye QY, Huang HP, Chen XC. Microglial phagocytosis induced by fibrillar β-amyloid is attenuated by oligomeric β-amyloid: implications for Alzheimer’s disease. Mol Neurodegener. 2011;6:45. doi: 10.1186/1750-1326-6-45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stefanova N, Fellner L, Reindl M, Masliah E, Poewe W, Wenning GK. Toll-like receptor 4 promotes α-synuclein clearance and survival of nigral dopaminergic neurons. Am J Pathol. 2011;179:954–963. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2011.04.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fellner L, Irschick R, Schanda K, Reindl M, Klimaschewski L, Poewe W, Wenning GK, Stefanova N. Toll-like receptor 4 is required for α-synuclein dependent activation of microglia and astroglia. Glia. 2013;61:349–360. doi: 10.1002/glia.22437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kim C, Ho DH, Suk JE, You S, Michael S, Kang J, Joong Lee S, Masliah E, Hwang D, Lee HJ, Lee SJ. Neuron-released oligomeric α-synuclein is an endogenous agonist of TLR2 for paracrine activation of microglia. Nat Commun. 2013;4:1562. doi: 10.1038/ncomms2534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Russo I, Berti G, Plotegher N, Bernardo G, Filograna R, Bubacco L, Greggio E. Leucine-rich repeat kinase 2 positively regulates inflammation and down-regulates NF-κB p50 signaling in cultured microglia cells. J Neuroinflamm. 2015;12:230. doi: 10.1186/s12974-015-0449-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lee HJ, Suk JE, Bae EJ, Lee SJ. Clearance and deposition of extracellular alpha-synuclein aggregates in microglia. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2008;372:423–428. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.05.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bae EJ, Lee HJ, Rockenstein E, Ho DH, Park EB, Yang NY, Desplats P, Masliah E, Lee SJ. Antibody-aided clearance of extracellular α-synuclein prevents cell-to-cell aggregate transmission. J Neurosci. 2012;32:13454–13469. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1292-12.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Al-Mansoori KM, Hasan MY, Al-Hayani A, El-Agnaf OM. The role of α-synuclein in neurodegenerative diseases: from molecular pathways in disease to therapeutic approaches. Curr Alzheimer Res. 2013;10:559–568. doi: 10.2174/1567205011310060002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schapira AH, Olanow CW, Greenamyre JT, Bezard E. Slowing of neurodegeneration in Parkinson’s disease and Huntington’s disease: future therapeutic perspectives. Lancet. 2014;384:545–555. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61010-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Funayama M, Hasegawa K, Kowa H, Saito M, Tsuji S, Obata F. A new locus for Parkinson’s disease (PARK8) maps to chromosome 12p11.2-q13.1. Ann Neurol. 2002;51:296–301. doi: 10.1002/ana.10113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Funayama M, Hasegawa K, Ohta E, Kawashima N, Komiyama M, Kowa H, Tsuji S, Obata F. An LRRK2 mutation as a cause for the parkinsonism in the original PARK8 family. Ann Neurol. 2005;57:918–921. doi: 10.1002/ana.20484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Paisán-Ruíz C, Jain S, Evans EW, Gilks WP, Simón J, van der Brug M, López de Munain A, Aparicio S, Gil AM, Khan N, Johnson J, Martinez JR, Nicholl D, Carrera IM, Pena AS, de Silva R, Lees A, Martí-Massó JF, Pérez-Tur J, Wood NW, Singleton AB. Cloning of the gene containing mutations that cause PARK8-linked Parkinson’s disease. Neuron. 2004;44:595–600. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.10.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zimprich A, Biskup S, Leitner P, Lichtner P, Farrer M, Lincoln S, Kachergus J, Hulihan M, Uitti RJ, Calne DB, Stoessl AJ, Pfeiffer RF, Patenge N, Carbajal IC, Vieregge P, Asmus F, Müller-Myhsok B, Dickson DW, Meitinger T, Strom TM, Wszolek ZK, Gasser T. Mutations in LRRK2 cause autosomal-dominant parkinsonism with pleomorphic pathology. Neuron. 2004;44:601–607. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Meylan E, Tschopp J. The RIP kinases: crucial integrators of cellular stress. Trends Biochem Sci. 2005;30:151–159. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2005.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Esteves AR, Swerdlow RH, Cardoso SM. LRRK2, a puzzling protein: insights into Parkinson’s disease pathogenesis. Exp Neurol. 2014;261:206–216. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2014.05.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Martin I, Kim JW, Dawson VL, Dawson TM. LRRK2 pathobiology in Parkinson’s disease. J Neurochem. 2014;131:554–565. doi: 10.1111/jnc.12949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gardet A, Benita Y, Li C, Sands BE, Ballester I, Stevens C, Korzenik JR, Rioux JD, Daly MJ, Xavier RJ, Podolsky DK. LRRK2 is involved in the IFN-gamma response and host response to pathogens. J Immunol. 2010;185:5577–5585. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1000548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kubo M, Kamiya Y, Nagashima R, Maekawa T, Eshima K, Azuma S, Ohta E, Obata F. LRRK2 is expressed in B-2 but not in B-1 B cells, and downregulated by cellular activation. J Neuroimmunol. 2010;229:123–128. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2010.07.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hakimi M, Selvanantham T, Swinton E, Padmore RF, Tong Y, Kabbach G, Venderova K, Girardin SE, Bulman DE, Scherzer CR, LaVoie MJ, Gris D, Park DS, Angel JB, Shen J, Philpott DJ, Schlossmacher MG. Parkinson’s disease-linked LRRK2 is expressed in circulating and tissue immune cells and upregulated following recognition of microbial structures. J Neural Transm. 2011;118:795–808. doi: 10.1007/s00702-011-0653-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Liu Z, Lee J, Krummey S, Lu W, Cai H, Lenardo MJ. The kinase LRRK2 is a regulator of the transcription factor NFAT that modulates the severity of inflammatory bowel disease. Nat Immunol. 2011;12:1063–1070. doi: 10.1038/ni.2113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kim B, Yang MS, Choi D, Kim JH, Kim HS, Seol W, Choi S, Jou I, Kim EY, Joe EH. Impaired inflammatory responses in murine Lrrk2-knockdown brain microglia. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e34693. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0034693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Moehle MS, Webber PJ, Tse T, Sukar N, Standaert DG, DeSilva TM, Cowell RM, West AB. LRRK2 inhibition attenuates microglial inflammatory responses. J Neurosci. 2012;32:1602–1611. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5601-11.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gillardon F, Schmid R, Draheim H. Parkinson’s disease-linked leucine-rich repeat kinase 2(R1441G) mutation increases proinflammatory cytokine release from activated primary microglial cells and resultant neurotoxicity. Neuroscience. 2012;208:41–48. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2012.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lin X, Parisiadou L, Gu XL, Wang L, Shim H, Sun L, Xie C, Long CX, Yang WJ, Ding J, Chen ZZ, Gallant PE, Tao-Cheng JH, Rudow G, Troncoso JC, Liu Z, Li Z, Cai H. Leucine-rich repeat kinase 2 regulates the progression of neuropathology induced by Parkinson’s-disease-related mutant alpha-synuclein. Neuron. 2009;64:807–827. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Daher JP, Volpicelli-Daley LA, Blackburn JP, Moehle MS, West AB. Abrogation of α-synuclein-mediated dopaminergic neurodegeneration in LRRK2-deficient rats. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111:9289–9294. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1403215111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ni M, Aschner M. Neonatal rat primary microglia: isolation, culturing, and selected applications. Curr Protoc Toxicol 2010, 12: Unit 12.17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 50.Lee HJ, Suk JE, Bae EJ, Lee JH, Paik SR, Lee SJ. Assembly-dependent endocytosis and clearance of extracellular alpha-synuclein. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2008;40:1835–1849. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2008.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Shin N, Jeong H, Kwon J, Heo HY, Kwon JJ, Yun HJ, Kim CH, Han BS, Tong Y, Shen J, Hatano T, Hattori N, Kim KS, Chang S, Seol W. LRRK2 regulates synaptic vesicle endocytosis. Exp Cell Res. 2008;314:2055–2065. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2008.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Heo HY, Kim KS, Seol W. Coordinate regulation of neurite outgrowth by LRRK2 and its interactor, Rab5. Exp Neurobiol. 2010;19:97–105. doi: 10.5607/en.2010.19.2.97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sung JY, Kim J, Paik SR, Park JH, Ahn YS, Chung KC. Induction of neuronal cell death by Rab5A-dependent endocytosis of alpha-synuclein. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:27441–27448. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M101318200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Stafa K, Tsika E, Moser R, Musso A, Glauser L, Jones A, Biskup S, Xiong Y, Bandopadhyay R, Dawson VL, Dawson TM, Moore DJ. Functional interaction of Parkinson’s disease-associated LRRK2 with members of the dynamin GTPase superfamily. Hum Mol Genet. 2014;23:2055–2077. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddt600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yun HJ, Kim H, Ga I, Oh H, Ho DH, Kim J, Seo H, Son I, Seol W. An early endosome regulator, Rab5b, is an LRRK2 kinase substrate. J Biochem. 2015;157:485–495. doi: 10.1093/jb/mvv005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bhattacharya M, Ojha N, Solanki S, Mukhopadhyay CK, Madan R, Patel N, Krishnamurthy G, Kumar S, Basu SK, Mukhopadhyay A. IL-6 and IL-12 specifically regulate the expression of Rab5 and Rab7 via distinct signaling pathways. EMBO J. 2006;25:2878–2888. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ozansoy M, Başak AN. The central theme of Parkinson’s disease: α-synuclein. Mol Neurobiol. 2013;47:460–465. doi: 10.1007/s12035-012-8369-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hinkle KM, Yue M, Behrouz B, Dächsel JC, Lincoln SJ, Bowles EE, Beevers JE, Dugger B, Winner B, Prots I, Kent CB, Nishioka K, Lin WL, Dickson DW, Janus CJ, Farrer MJ, Melrose HL. LRRK2 knockout mice have an intact dopaminergic system but display alterations in exploratory and motor co-ordination behaviors. Mol Neurodegener. 2012;7:25. doi: 10.1186/1750-1326-7-25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The key data supporting the conclusions of this article are included within the article. The raw datasets used in the study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.