Abstract

Guanine oxidation occurs in both DNA and the cellular nucleotide pool, and one of the major products is 8-hydroxyguanine (8-oxo-7,8-dihydroguanine). The mutagenic potentials of this oxidized base have been examined in various experimental systems. In this review, we summarize the mutagenicity of the base in mammalian cells. We also describe the effects of specialized DNA polymerases, DNA repair proteins, and nucleotide pool sanitization enzymes.

Keywords: 8-Hydroxyguanine; 8-Oxo-7,8-dihydroguanine; Specialized DNA polymerase; DNA repair protein; Nucleotide pool sanitization enzyme

Background

DNA oxidation by reactive oxygen species has been studied for decades, due to the pivotal role of damaged DNA in processes such as mutagenesis, carcinogenesis, aging, and neurodegeneration [1–3]. Moreover, oxidized DNA precursors (2’-deoxyribonucleoside 5’-triphosphates) formed in the cellular nucleotide pool also participate in these events. Reactive oxygen species are formed endogenously and are also produced by many environmental mutagens and carcinogens. Cancer involves multiple mutations in oncogenes and tumor suppressor genes, and thus oxidized DNA and DNA precursors might contribute to an extremely high percentage of carcinogenic events.

Kasai et al. reported the formation of 8-hydroxyguanine (GO, 8-oxo-7,8-dihydroguanine) by the oxidation of guanine in DNA and nucleosides [4–6]. Moreover, many research groups observed its generation under various experimental conditions in vitro, in living cells, and in vivo (e.g. [7–11]). GO is now recognized as one of the most important DNA lesions and has been used as a marker for DNA oxidation [12, 13], due to its prevalence in DNA and its high mutagenicity in mammalian cells. In this review, we summarize the mutagenic properties of the GO damage in mammalian cells, based on results obtained in various experimental systems.

Targeted mutations induced by GO

One of us (HK) constructed synthetic c-Ha-ras proto-oncogenes containing an GO:C pair in hotspots (codons 12 and 61). The modified bases were introduced into the first and second positions of codon 12 in the sense strand (5’-GGC-3’), and into the first position of codon 61 in the antisense strand (5’-CAA-3’, antisense strand 5’-TTG-3’) of the gene. Since most amino acid alterations in these hotspots activate the gene [14, 15], most base substitution mutations at the GO sites induce the transformation of mouse NIH3T3 cells. Thus, the type of mutation induced by the damaged base was determined by an analysis of the gene present in focus-forming cells, after transfection into NIH3T3 cells [16, 17]. The numbers of foci formed upon the transfection of the c-Ha-ras genes with GO were ~1 %, as compared to those formed by the activated c-Ha-ras genes (Val/Asp-12 and Lys/His-61).

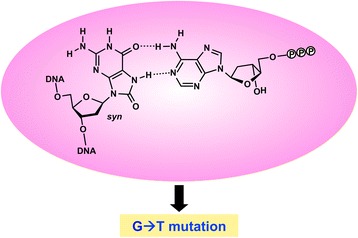

Sequence analysis of the c-Ha-ras gene present in the transformed cells indicated that the major mutation induced by GO is a G➔T transversion [16, 17]. This was the first report on the mutation spectrum of this modified base in mammalian cells. This result was in good agreement with dATP incorporation opposite GO by DNA polymerases (pols) in vitro [18, 19] (Fig. 1) and GO-induced mutations in Escherichia coli [20–23]. The oxidized guanine at the second position of codon 12 (5’-GGOC-3’) also induced a G➔A transition. The finding that the G➔A mutation was induced suggested that dTTP is also misinserted opposite GO in a sequence-dependent manner, during DNA replication in NIH3T3 cells. The remarkably high thermodynamic stability (small ΔG 0 value) of the GO:T pair near the 5’-end (mimicking the nucleotide incorporation step) in the 5’-GGOC-3’ sequence may be related to the observed G➔A mutation [24]. Moreover, mutations at the 5’-adjacent positions were found, when GO was incorporated into the second position of codon 12 and the first position of codon 61. Note that transformation occurs when an activated oncogene is present in the chromosomal DNA. The results observed in these studies are interpreted as the consequences of the integration of GO into the chromosomal DNA and the subsequent replication of the modified chromosome(s). The relative transforming activities of the c-Ha-ras genes with GO (~1 %) would reflect the mutation frequencies of the base in a semi-quantitative manner.

Fig. 1.

Mutation induction by dATP incorporation opposite GO in template DNA. When the syn-oriented GO base forms a Hoogsteen-type base pair with the A base of dATP in the active site of a DNA polymerase, this pairing causes the G➔T mutations.  represents a phosphate group

represents a phosphate group

The mutagenicity of GO in double-stranded (ds) plasmid DNA has been examined. Le Page et al. constructed a shuttle plasmid containing an GO:C pair in the sequence corresponding to codon 12 of the human c-Ha-ras gene (5’-GGOC-3’), and introduced it into simian COS-7 and human MRC5V1 cells [25]. The vector has the SV40 origin and can replicate in these cell lines. The replicated plasmid DNA was recovered and introduced into bacterial cells. The plasmid DNAs isolated from colonies were analyzed by a restriction enzyme that cleaves the plasmid without the targeted mutations and by sequencing. Among the 101 bacterial colonies analyzed, none had the mutated sequence in the COS-7 experiment. Moreover, only one colony among the 125 colonies obtained in the MRC5V1 experiment had the targeted G➔T transversion. Thus, the mutation frequency of GO was less than 1 % in their experiments.

Our research group also performed similar experiments, using a shuttle vector containing the oxidized base in the supF gene and the SV40 origin [26–30]. The base was incorporated into the 5’-GGOT-3’ sequence of the gene. The GO plasmid was transfected into human 293T and U2OS cells, and the replicated plasmid was introduced into the indicator bacterial cells (KS40/pOF105). Mutations in the supF gene are detectable using this strain, since most mutations in the gene confer nalidixic acid and streptomycin resistance to the cells. The frequencies of base substitution mutations at the GO site were 3–6 and ~1 × 10-3 in 293T and U2OS cells, respectively. The major mutation was a G➔T transversion, but G➔A and G➔C mutations were also observed at lower frequencies. Semitargeted mutations at the 5’-flanking positions were also detected.

Sunaga et al. and Yamane et al. incorporated an GO:C pair into the 5’-AGOG-3’ sequence in the supF gene, and introduced the ds supF shuttle plasmid into NCI-H1299 cells [31, 32]. In contrast to the experiments by Le Page et al. and our research group, the G➔T mutations were induced with frequencies of 2-4 %.

Yasui et al. developed a system for the site-specific introduction of DNA lesions into human genomic DNA [33]. They used lymphoblastoid TSCER122 cells heterozygous for the thymidine kinase gene. The cells display a TK-/- phenotype, since one allele contains a mutation in exon 4 and the other has an I-Sce I site and a 356-bp deletion in exon 5. Linear 6.1-kbp DNA containing the wild-type exon 5 and an GO residue (in an intron) was introduced into the cells, together with the I-Sce I expression DNA. The correct targeting restored the wild-type phenotype for thymidine kinase. Sequence analysis of the genomic DNA of revertant clones (TK+/-) indicated that the modified base induced G➔T, G➔C, and G➔A targeted mutations, with G➔T mutation frequencies of 5-8 %.

In addition to the approaches using ds DNA, the mutagenicity of GO in single-stranded shuttle plasmid (phagemid) DNAs has been examined in simian cells [34–36]. GO induced mutations with a frequency of 4–7 %, and the major mutation was the G➔T transversion. Moreover, G➔A and G➔C mutations were detected. Recently, Pande et al. examined the mutagenic properties of GO in the 5’-TGON-3’ (N = A, G, C, and T) sequence in human 293T cells [37]. The frequencies of G➔T targeted mutations were 5–11 %, and G➔A and 2-base deletion mutations were also induced. In particular, the G➔A mutation was observed as frequently as the G➔T mutation, in the case of the 5’-TGOG-3’ sequence. In addition to the mutations in the modified position, semi-targeted mutations at the neighboring positions were found.

Roles of specialized DNA pols

We knocked-down DNA pols η, ι, ζ, and REV1 by their respective siRNAs in human 293T cells, and introduced the ds supF shuttle plasmid into the knockdown cells [26]. The knockdowns of DNA pols η and ζ enhanced the G➔T mutation by an GO:C pair in the plasmid, but those of pol ι and REV1 had no effect [26]. These results indicated that DNA pols η and ζ are involved in error-free bypass of the GO base during the replication of ds DNA (Table 1). In contrast, the G ➔T mutation induced by the oxidized base in the ds shuttle plasmid decreased in the DNA pol κ-knockdown human U2OS cells [28]. This result suggested that DNA pol κ bypasses the GO base in an error-prone manner.

Table 1.

Expected functions of cellular proteins related to mutations by GO directly produced in DNA

| Protein | Role | |

|---|---|---|

| Specialized DNA pol | ||

| pol η | error-free bypass | |

| pol ζ | error-free bypass | |

| pol κ | error-prone bypass | |

| pol λ | error-free bypass, suppression of untargeted mutations | |

| DNA glycosylase | ||

| OGG1 | suppression of G→T mutation by GO removal | |

| MUTYH | suppression of G→T mutation by A removal | |

| NTH1 | suppression of G→T mutation | |

| NEIL1 | suppression of G→T mutation | |

| WRN | suppression of untargeted mutations |

Interestingly, the knockdown of DNA pol λ increased the 2-base deletion mutations induced by GO in single-stranded DNA [37]. This result suggested that DNA pol λ is involved in the error-free bypass of GO, by preventing the 2-base deletion.

Roles of DNA glycosylases

Overexpression of nuclear OGG1 or MUTYH, which are the major DNA glycosylases involved in the base excision repair of GO [38], suppressed the G➔T mutation frequency in a ds supF shuttle plasmid containing an GO:C pair [31, 32]. Yasui et al. also reported that the G➔T mutation, caused by GO site-specifically introduced into genomic DNA, was reduced in MUTYH-overexpressing cells [33]. In accordance with these observations, we found that the knockdowns of the OGG1 and MUTYH DNA glycosylases in human cells significantly increased the frequencies of G➔T transversion caused by GO:C in the supF shuttle plasmid [27]. Surprisingly, the G➔T mutation was also enhanced when the levels of other DNA glycosylases, NTH1 and NEIL1, were decreased. These results indicated that all of these DNA glycosylases suppress the G➔T mutations caused by GO:C pairs generated in DNA (Table 1).

Untargeted mutations induced by GO

Our research group introduced the ds supF plasmid containing GO:C into human U2OS cells, in which the Werner syndrome protein (WRN) was knocked-down. The total supF mutant frequency was 1.6-fold higher in the knockdown cells, as compared to the control cells [29]. Sequence analysis indicated that the targeted G➔T mutation frequency was increased only slightly by the WRN knockdown. Instead, the knockdown promoted base substitution mutations at untargeted G (or G:C) sites with statistical significance. These “action-at-a-distance mutations” seemed to be broadly distributed throughout the supF gene. As discussed in the original report, there are many possible explanations for these types of mutations at this time.

Similar “action-at-a-distance mutations” were observed when the GO:C plasmid was transfected into cells with knocked-down DNA pol λ, one of the specialized DNA pols [30]. The untargeted mutations at the G sites were significantly increased, but the frequency of untargeted mutations at G:C pairs was not significant (P = 0.10). The cause(s) of the untargeted mutations remain unknown, but they could be the same as those observed in the WRN knockdown cells, since DNA pol λ interacts with WRN [39].

As mentioned above, substitution mutations were found at the 5’-adjacent positions of GO [16, 17]. Interestingly, Nishimura and his colleagues found that human DNA pol η misincorporated deoxyribonucleotides opposite G at the 5’-flanking site of GO in the 5’-GGOC-3’ sequence in vitro [40]. The 5’-flanking mutations observed in mammalian cells may involve some similar events.

Mutations induced by 8-OH-dGTP in mammalian cells

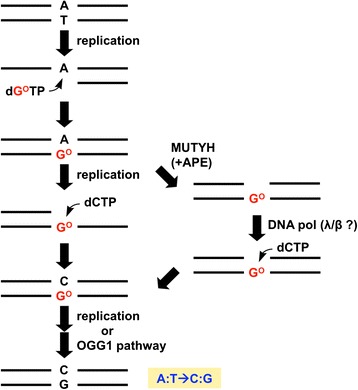

The ability of GO to form base pairs with A and C also causes mutations when dGTP is oxidized to produce 8-hydroxy-dGTP (dGOTP, 8-oxo-7,8-dihydro-dGTP). Shuttle plasmid DNA containing the supF gene was first transfected, and then dGOTP was introduced into simian COS-7 and human 293T cells to examine its mutagenicity in mammalian cells. The oxidized dGTP caused A:T➔C:G transversion mutations [41, 42]. These results are consistent with observations that dGOTP was incorporated opposite A by DNA pols in vitro, and that the same types of substitutions were induced in E. coli upon treatment with the oxidized deoxyribonucleotide [43, 44]. This mutation spectrum is explained by the misincorporation of dGOTP opposite A, and the insertion of dCTP opposite GO in DNA during the second round of replication (Fig. 2). The removal of the A bases opposite GO by MUTYH and the subsequent dCTP insertion by repair DNA pols would promote the A:T➔C:G mutations induced by the incorporation of dGOTP (Fig. 2) (see below).

Fig. 2.

Mutagenesis pathways of dGOTP. APE: AP endonuclease

Roles of specialized DNA pols in mutagenesis by dGOTP

The A:T➔C:G substitution mutations were decreased upon the knockdowns of DNA pols η and ζ, and REV1 by siRNAs in human 293T cells [42]. Thus, these specialized DNA pols seem to be involved in the mutation pathway(s) of the oxidized dGTP. To determine whether these DNA pols contribute to the incorporation of dGOTP and/or the insertion of dCTP opposite GO, plasmid DNA containing an GO:A pair, an intermediate in the mutagenic process of dGOTP, was transfected into 293T cells with knocked-down specialized DNA pols. The reduction of DNA pol η decreased the mutations induced by the GO:A pair by ~8 %, in agreement with the observation that dCTP is preferentially incorporated opposite GO by this DNA pol [40, 45]. However, the decrease was much smaller as compared to the case of dGOTP-induced mutations (~32 %). Thus, the decreased A:T➔C:G mutations by dGOTP in the pol η-knockdown cells would be mainly due to reduced dGOTP incorporation into the nascent strand (Table 2). This interpretation agrees with the observation that this DNA pol incorporates dGOTP opposite A in a highly erroneous manner in vitro [46, 47].

Table 2.

Expected functions of cellular proteins related to dGOTP-induced mutation

| Protein | Role | |

|---|---|---|

| Specialized DNA pol | ||

| pol η | incorporation of dGOTP | |

| pol ζ | incorporation of dGOTP | |

| REV1 | incorporation of dGOTP | |

| DNA glycosylase | ||

| MUTYH | promotion of A:T→C:G mutation | |

| Nucleotide pool sanitization enzyme | ||

| MTH1 | decrease of dGOTP | |

| MTH2 | decrease of dGOTP | |

| NUDT5 | decrease of dGOTP |

Meanwhile, no obvious effects were observed when plasmid DNA containing GO:A was transfected into DNA pol ζ- and REV1-knockdown cells. Thus, the two DNA pols are likely to play important roles in the incorporation of dGOTP, but not in the insertion of dCTP opposite GO (Table 2).

Mutation enhancement by MUTYH DNA glycosylase

The MUTYH DNA glycosylase removes A paired with GO, thus preventing G➔T mutations [38]. However, this activity may promote the A:T➔C:G transversions induced by dGOTP. We examined this possibility by the knockdown of the enzyme and the subsequent introduction of dGOTP or a supF plasmid containing an GO:A pair into the cells [27]. The A:T➔C:G mutation frequency of the shuttle plasmid containing A paired with GO was decreased in the MUTYH-knockdown cells. The knockdown of MUTYH also reduced the mutation frequency induced by the introduction of dGOTP into cells [27]. These results suggested that MUTYH promotes A:T➔C:G mutations by dGOTP in the nucleotide pool, although it suppresses G➔T mutations induced by GO formed by the direct oxidation of DNA (Fig. 2 and Table 2).

No effects were observed when dGOTP or a supF plasmid containing GO:A was introduced into the cells in which the OGG1, NTH1, and NEIL1 glycosylases were knocked-down [27].

Nucleotide pool sanitization enzymes

Nucleotide pool sanitization, the specific hydrolysis of damaged DNA precursors, is an important means by which organisms prevent mutations [48, 49]. In mammalian cells, the MTH1 (NUDT1), MTH2 (NUDT15), and NUDT5 proteins catalyze the hydrolysis of dGOTP and/or its diphosphate derivative to produce the monophosphate compound [50–53]. Both the supF plasmid DNA and dGOTP were introduced into cells in which the expression of each protein was knocked-down. The A:T➔C:G substitution mutations induced by dGOTP were higher in the knockdown cells than in control cells [54]. The increase in the induced mutation was more evident in the triple knockdown cells. These results indicated that all three proteins act as a defense against the mutagenesis induced by oxidized dGTP (Table 2).

Conclusions

The G➔T transversion is the major targeted substitution mutation caused by the GO base in mammalian cells. Moreover, the G➔A and G➔C mutations at the GO site and the substitution mutations at the 5’-adjacent position of GO are also induced. Action-at-a-distance mutations at untargeted positions are detected when the levels of WRN and DNA pol λ are reduced. The A:T➔C:G (A➔C) transversion is the mutation induced by dGOTP in the cellular nucleotide pool. The DNA repair and nucleotide pool sanitization enzymes function as the defenses against GO in DNA and the nucleotide pool, respectively. MUTYH is an exceptional DNA repair protein, since it enhances the A:T➔C:G mutations when GO is formed in the nucleotide pool. Some specialized DNA pols are involved in nucleotide incorporation opposite GO and/or dGOTP incorporation, and thus affect the mutation induction by GO. The mutagenic properties of GO are affected by various factors, including the sequence contexts and the amounts of specialized DNA pols, DNA repair proteins, and nucleotide pool sanitization enzymes. This is one of the explanations for the fact that various mutation frequencies of GO:C have been observed, as described above. Further studies are necessary to reveal the detailed mechanisms of the GO-induced mutagenesis and its suppression by cellular proteins, using various experimental systems.

Abbreviations

dGOTP, 8-hydroxy-dGTP (8-oxo-7,8-dihydro-dGTP); GO, 8-hydroxyguanine (8-oxo-7,8-dihydroguanine); pol, polymerase; ds, double-stranded.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank the collaborators who participated in the experiments described in this paper, especially Profs. Eiko Ohtsuka and Hideyoshi Harashima of Hokkaido University. Work in our laboratory was supported in part by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science KAKENHI Grants 20012001, 25550032 and 16H02956, and Grants from the Takeda Science Foundation to HK.

Authors’ contributions

Both TS and HK wrote the manuscript and read and approved the final version.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Contributor Information

Tetsuya Suzuki, Email: suzukite@hiroshima-u.ac.jp.

Hiroyuki Kamiya, Phone: +81-82-257-5300, FAX: +81-82-257-5334, Email: hirokam@hiroshima-u.ac.jp.

References

- 1.Halliwell B, Aruoma OI. DNA damage by oxygen-derived species. Its mechanism and measurement in mammalian systems. FEBS Lett. 1991;281:9–19. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(91)80347-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ames BN, Shigenaga MK, Hagen TM. Oxidants, antioxidants, and the degenerative diseases of aging. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993;90:7915–22. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.17.7915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kamiya H. Mutagenic potentials of damaged nucleic acids produced by reactive oxygen/nitrogen species: approaches using synthetic oligonucleotides and nucleotides: survey and summary. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:517–31. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kasai H, Nishimura S. Hydroxylation of deoxyguanosine at the C-8 position by ascorbic acid and other reducing agents. Nucleic Acids Res. 1984;12:2137–45. doi: 10.1093/nar/12.4.2137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kasai H, Tanooka H, Nishimura S. Formation of 8-hydroxyguanine residue in DNA by X-irradiation. Gann. 1984;75:1037–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kasai H, Crain PF, Kuchino Y, Nishimura S, Ootsuyama A, Tanooka H. Formation of 8-hydroxyguanine moiety in cellular DNA by agents producing oxygen radicals and evidence for its repair. Carcinogenesis. 1986;7:1849–51. doi: 10.1093/carcin/7.11.1849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kohda K, Tada M, Hakura A, Kasai H, Kawazoe Y. Formation of 8-hydroxyguanine residues in DNA treated with 4-hydroxyaminoquinoline 1-oxide and its related compounds in the presence of seryl-AMP. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1987;149:1141–8. doi: 10.1016/0006-291X(87)90527-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Floyd RA, West MS, Eneff KL, Hogsett WE, Tingey DT. Hydroxyl free radical mediated formation of 8-hydroxyguanine in isolated DNA. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1988;262:266–72. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(88)90188-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fraga CG, Shigenaga MK, Park JW, Degan P, Ames BN. Oxidative damage to DNA during aging: 8-hydroxy-2’-deoxyguanosine in rat organ DNA and urine. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1990;87:4533–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.12.4533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mouret JF, Polverelli M, Sarrazini F, Cadet J. Ionic and radical oxidations of DNA by hydrogen peroxide. Chem Biol Interact. 1991;77:187–201. doi: 10.1016/0009-2797(91)90073-G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Murata-Kamiya N, Kamiya H, Muraoka M, Kaji H, Kasai H. Comparison of oxidation products from DNA components by γ-irradiation and Fenton-type reactions. J Radiat Res. 1997;38:121–31. doi: 10.1269/jrr.38.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kasai H. Analysis of a form of oxidative DNA damage, 8-hydroxy-2’-deoxyguanosine, as a marker of cellular oxidative stress during carcinogenesis. Mutat Res. 1997;387:147–63. doi: 10.1016/S1383-5742(97)00035-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Helbock HJ, Beckman KB, Ames BN. 8-Hydroxydeoxyguanosine and 8-hydroxyguanine as biomarkers of oxidative DNA damage. Methods Enzymol. 1999;300:156–66. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(99)00123-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Seeburg PH, Colby WW, Capon DJ, Goeddel DV, Levinson AD. Biological properties of human c-Ha-ras1 genes mutated at codon 12. Nature. 1984;312:71–5. doi: 10.1038/312071a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Der CJ, Finkel T, Cooper GM. Biological and biochemical properties of human rasH genes mutated at codon 61. Cell. 1986;44:167–76. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(86)90495-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kamiya H, Miura K, Ishikawa H, Inoue H, Nishimura S, Ohtsuka E. c-Ha-ras containing 8-hydroxyguanine at codon 12 induces point mutations at the modified and adjacent positions. Cancer Res. 1992;52:3483–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kamiya H, Murata-Kamiya N, Koizume S, Inoue H, Nishimura S, Ohtsuka E. 8-Hydroxyguanine (7,8-dihydro-8-oxoguanine) in hot spots of the c-Ha-ras gene: effects of sequence contexts on mutation spectra. Carcinogenesis. 1995;16:883–9. doi: 10.1093/carcin/16.4.883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shibutani S, Takeshita M, Grollman AP. DNA synthesis past the oxidation-damaged base 8-oxodG. Nature. 1991;349:431–4. doi: 10.1038/349431a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kamiya H, Sakaguchi T, Murata N, Fujimuro M, Miura H, Ishikawa H, Shimizu M, Inoue H, Nishimura S, Matsukage A, Masutani C, Hanaoka F, Ohtsuka E. In vitro replication study of modified bases in ras sequences. Chem Pharm Bull. 1992;40:2792–5. doi: 10.1248/cpb.40.2792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wood ML, Dizdaroglu M, Gajewski E, Essigmann JM. Mechanistic studies of ionizing radiation and oxidative mutagenesis: genetic effects of a single 8-hydroxyguanine (7-hydro-8-oxoguanine) residue inserted at a unique site in a viral genome. Biochemistry. 1990;29:7024–32. doi: 10.1021/bi00482a011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cheng KC, Cahill DS, Kasai H, Nishimura S, Loeb LA. 8-Hydroxyguanine, an abundant form of oxidative DNA damage, causes G➔T and A➔C substitutions. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:166–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Moriya M, Grollman AP. Mutations in the mutY gene of Escherichia coli enhance the frequency of targeted G:C➔T:A transversions induced by a single 8-oxoguanine residue in single-stranded DNA. Mol Gen Genet. 1993;239:72–6. doi: 10.1007/BF00281603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wagner J, Kamiya H, Fuchs RPP. Leading versus lagging strand mutagenesis induced by 7,8-dihydro-8-oxo-2’-deoxyguanosine in E. coli. J Mol Biol. 1997;265:302–9. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1996.0740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Koizume S, Kamiya H, Inoue H, Ohtsuka E. Synthesis and thermodynamic stabilities of damaged DNA involving 8-hydroxyguanine (7,8-dihydro-8-oxoguanine) in a ras gene fragment. Nucleosides Nucleotides. 1994;13:1517–34. doi: 10.1080/15257779408012168. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Le Page F, Guy A, Cadet J, Sarasin A, Gentil A. Repair and mutagenic potency of 8-oxoG:A and 8-oxoG:C base pairs in mammalian cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 1998;26:1276–81. doi: 10.1093/nar/26.5.1276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kamiya H, Yamaguchi A, Suzuki T, Harashima H. Roles of specialized DNA polymerases in mutagenesis by 8-hydroxyguanine in human cells. Mutat Res. 2010;686:90–5. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2010.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Suzuki T, Harashima H, Kamiya H. Effects of base excision repair proteins on mutagenesis by 8-oxo-7,8-dihydroguanine (8-hydroxyguanine) paired with cytosine and adenine. DNA Repair (Amst) 2010;9:542–50. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2010.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kamiya H, Kurokawa M. Mutagenic bypass of 8-oxo-7,8-dihydroguanine (8-hydroxyguanine) by DNA polymerase k in human cells. Chem Res Toxicol. 2012;25:1771–6. doi: 10.1021/tx300259x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kamiya H, Yamazaki D, Nakamura E, Makino T, Kobayashi M, Matsuoka I, Harashima H. Action-at-a-distance mutagenesis induced by oxidized guanine in Werner syndrome protein-reduced human cells. Chem Res Toxicol. 2015;28:621–8. doi: 10.1021/tx500418m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kamiya H, Kurokawa M, Makino T, Kobayashi M, Matsuoka I. Induction of action-at-a-distance mutagenesis by 8-oxo-7,8-dihydroguanine in DNA pol λ-knockdown cells. Genes Environ. 2015;37:10. doi: 10.1186/s41021-015-0015-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sunaga N, Kohno T, Shinmura K, Saitoh T, Matsuda T, Saito R, Yokota J. OGG1 protein suppresses G:C➔T:A mutation in a shuttle vector containing 8-hydroxyguanine in human cells. Carcinogenesis. 2001;22:1355–62. doi: 10.1093/carcin/22.9.1355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yamane A, Shinmura K, Sunaga N, Saitoh T, Yamaguchi S, Shinmura Y, Yoshimura K, Murakami H, Nojima Y, Kohno T, Yokota J. Suppressive activities of OGG1 and MYH proteins against G:C to T:A mutations caused by 8-hydroxyguanine but not by benzo[a]pyrene diol epoxide in human cells in vivo. Carcinogenesis. 2003;24:1031–7. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgg056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yasui M, Kanemaru Y, Kamoshita N, Suzuki T, Arakawa T, Honma M. Tracing the fates of site-specifically introduced DNA adducts in the human genome. DNA Repair (Amst) 2014;15:11–20. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2014.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Moriya M. Single-stranded shuttle phagemid for mutagenesis studies in mammalian cells: 8-oxoguanine in DNA induces targeted G•C➔T•A transversions in simian kidney cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993;90:1122–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.3.1122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Le Page F, Margot A, Grollman AP, Sarasin A, Gentil A. Mutagenicity of a unique 8-oxoguanine in a human Ha-ras sequence in mammalian cells. Carcinogenesis. 1995;16:2779–84. doi: 10.1093/carcin/16.11.2779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tan X, Grollman AP, Shibutani S. Comparison of the mutagenic properties of 8-oxo-7,8-dihydro-2’-deoxyadenosine and 8-oxo-7,8-dihydro-2’-deoxyguanosine DNA lesions in mammalian cells. Carcinogenesis. 1999;20:2287–92. doi: 10.1093/carcin/20.12.2287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pande P, Haraguchi K, Jiang Y-L, Greenberg MM, Basu AK. Unlike catalyzing error-free bypass of 8‐oxodGuo, DNA polymerase λ is responsible for a significant part of Fapy · dG-induced G➔T mutations in human cells. Biochemistry. 2015;54:1859–62. doi: 10.1021/acs.biochem.5b00119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nakabeppu Y. Cellular levels of 8-oxoguanine in either DNA or the nucleotide pool play pivotal roles in carcinogenesis and survival of cancer cells. Int J Mol Sci. 2014;15:12543–57. doi: 10.3390/ijms150712543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kanagaraj R, Parasuraman P, Mihaljevic B, van Loon B, Burdova K, König C, Furrer A, Bohr VA, Hübscher U, Janscak P. Involvement of Werner syndrome protein in MUTYH-mediated repair of oxidative DNA damage. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:8449–59. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jałoszyński P, Masutani C, Hanaoka F, Perez AB, Nishimura S. 8-Hydroxyguanine in a mutational hotspot of the c-Ha-ras gene causes misreplication, ‘action-at-a-distance’ mutagenesis and inhibition of replication. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:6085–95. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Satou K, Kawai K, Kasai H, Harashima H, Kamiya H. Mutagenic effects of 8-hydroxy-dGTP in live mammalian cells. Free Radical Biol Med. 2007;42:1552–60. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2007.02.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Satou K, Hori M, Kawai K, Kasai H, Harashima H, Kamiya H. Involvement of specialized DNA polymerases in mutagenesis by 8-hydroxy-dGTP in human cells. DNA Repair (Amst) 2009;8:637–42. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2008.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Maki H, Sekiguchi M. MutT protein specifically hydrolyses a potent mutagenic substrate for DNA synthesis. Nature. 1992;355:273–5. doi: 10.1038/355273a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Inoue M, Kamiya H, Fujikawa K, Ootsuyama Y, Murata-Kamiya N, Osaki T, Yasumoto K, Kasai H. Induction of chromosomal gene mutations in Escherichia coli by direct incorporation of oxidatively damaged nucleotides. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:11069–74. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.18.11069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Maga G, Villani G, Crespan E, Wimmer U, Ferrari E, Bertocci B, Hübscher U. 8-Oxo-guanine bypass by human DNA polymerases in the presence of auxiliary proteins. Nature. 2007;447:606–8. doi: 10.1038/nature05843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shimizu M, Gruz P, Kamiya H, Kim S-R, Pisani FM, Masutani C, Kanke Y, Harashima H, Hanaoka F, Nohmi T. Erroneous incorporation of oxidized DNA precursors by Y-family DNA polymerases. EMBO Rep. 2003;4:269–73. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.embor765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shimizu M, Gruz P, Kamiya H, Masutani C, Xu Y, Usui Y, Sugiyama H, Harashima H, Hanaoka F, Nohmi T. Efficient and erroneous incorporation of oxidized DNA precursors by human DNA polymerase η. Biochemistry. 2007;46:5515–22. doi: 10.1021/bi062238r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sekiguchi M, Tsuzuki T. Oxidative nucleotide damage: consequences and prevention. Oncogene. 2002;21:8895–904. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kamiya H. Mutagenicity of oxidized DNA precursors in living cells: Roles of nucleotide pool sanitization and DNA repair enzymes, and translesion synthesis DNA polymerases. Mutat Res. 2010;703:32–6. doi: 10.1016/j.mrgentox.2010.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mo JY, Maki H, Sekiguchi M. Hydrolytic elimination of a mutagenic nucleotide, 8-oxodGTP, by human 18-kilodalton protein: sanitization of nucleotide pool. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1992;89:11021–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.22.11021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Fujikawa K, Kamiya H, Yakushiji H, Fujii Y, Nakabeppu Y, Kasai H. The oxidized forms of dATP are substrates for the human MutT homologue, the hMTH1 protein. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:18201–5. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.26.18201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cai JP, Ishibashi T, Takagi Y, Hayakawa H, Sekiguchi M. Mouse MTH2 protein which prevents mutations caused by 8-oxoguanine nucleotides. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2003;305:1073–7. doi: 10.1016/S0006-291X(03)00864-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ishibashi T, Hayakawa H, Sekiguchi M. A novel mechanism for preventing mutations caused by oxidation of guanine nucleotides. EMBO Rep. 2003;4:479–83. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.embor838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hori M, Satou K, Harashima H, Kamiya H. Suppression of mutagenesis by 8-hydroxy-2’-deoxyguanosine 5’-triphosphate (7,8-dihydro-8-oxo-2’-deoxyguanosine 5’-triphosphate) by human MTH1, MTH2, and NUDT5. Free Radical Biol Med. 2010;48:1197–201. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2010.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]