ABSTRACT

Aim: To assist in the long-term health management of residents and evaluate the health impacts after the Tokyo Electric Power Company’s Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant accident in Fukushima Prefecture, the Fukushima prefectural government decided to implement the Fukushima Health Management Survey. This report describes the results for residents aged 15 years or younger who received health checks and evaluates the data obtained from 2011 and 2012.

Methods: The target group consisted of residents aged 15 years or younger who had lived in the evacuation zone. The health checks were performed on receipt of an application from any of the residents. The checks, which included the measurements of height, weight, blood pressure, biochemical laboratory findings, and peripheral blood findings, were performed as required.

Results: 1) A total of 17,934 (64.5%) and 11,780 (43.5%) residents aged 15 years or younger received health checks in 2011 and 2012, respectively. 2) In both years, a number of male and female residents in the 7-15 year age group were found to suffer from obesity, hyperlipidemia, hyperuricemia, or liver dysfunction. Furthermore, pediatric aged 15 years or younger were commonly observed to suffer from hypertension or glucose metabolic abnormalities. 3) A comparison of data from 2012 and 2011 demonstrated that both males and females frequently showed increased body height and decreased body weight in 2012. The prevalence of hypertension, glucose metabolic abnormalities, or high γ-GTP values in males and females in the 7-15 year age group in 2012 was lower than that in 2011. However, the prevalence of hyperuricemia among residents in the 7-15 year age group was higher in 2012 than in 2011.

Conclusions: These results suggested that some residents aged 15 years or under who had lived in the evacuation zone had developed obesity, hyperlipidemia, hyperuricemia, liver dysfunction, hypertension, or glucose metabolic abnormalities. Therefore, we think that it is necessary to continue the health checks for these residents in order to ameliorate these lifestyle-related diseases.

Keywords: health check, Fukushima Health Management Survey, The Great East Japan Earthquake, child, adult

INTRODUCTION

On March 11, 2011, a massive undersea earthquake and subsequent tsunami struck East Japan. With a Richter-scale magnitude of 9.0, the Great East Japan Earthquake was one of the most powerful earthquakes on record and the largest to hit Japan1-4). The associated tsunami hit the northern part of the main island of Honshu, covering more than 800km of the Pacific coastline and claiming nearly 20,000 lives. In Fukushima Prefecture, 1,609 people were confirmed killed and 207 remain missing5,6).

The Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant, which is owned and operated by the Tokyo Electric Power Company was severely damaged by the earthquake and tsunami. The tsunami destroyed the direct current power supply, resulting in a complete loss of power to the Nuclear Power Plant cooling system. Consequently, the overheated Nuclear Power Plant reactor cores underwent a meltdown and hydrogen gas explosions dispersed large amounts of radionuclide materials into the surrounding areas7). Due to the accident at the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant, residents of all ages living in the evacuation zone-, a government-designated area around the nuclear power plant in Fukushima prefecture, were evacuated. As a result, many child evacuees from the government-designated evacuation zone were forced to make changes to their lifestyle, such as school life, diets, free play outside with friends, exercise patterns, and sleep patterns. Further, some parents experienced anxiety regarding their health status, particularly with regard to radiation exposure.

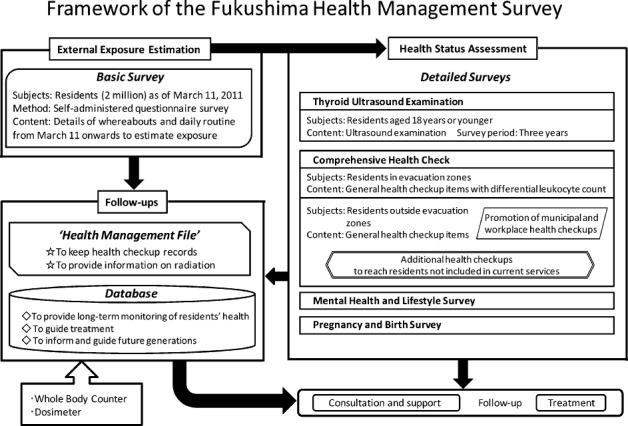

The Fukushima prefectural government decided to conduct what it called the Fukushima Health Management Survey (FHMS) to assist in the long-term health management of residents, to evaluate the health impacts of the accident, to promote the future well-being of residents, and to determine whether long-term low-dose radiation exposure has any effect of their health4,8). The framework of the FHMS was showed in Fig. 1. Comprehensive health checks (CHCs) are part of the detailed FHMSs and we sought to review the data regarding their health, assess the incidence of various diseases, and improve the health status of evacuees.

Fig. 1.

Items included in the comprehensive health check.

To assist in the long-term health management of residents aged 15 years or under and evaluate the health impacts after the Tokyo Electric Power Company’s Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant accident, we performed health checks for child evacuees from the government-designated evacuation zone and analyzed the basic data.

METHODS

The study was carried out under the auspices of the Committee for Human Experiments at the Fukushima Medical University School (the Institutional Review Board approval number 1319). Informed consent was obtained from all residents aged 15 years or under, who have received health checks or their parents. The target group and methods employed in the CHC were reported previously by Yasumura et al.8).

Target group

The target group consisted of residents aged 15 years or under who had lived in Hirono-machi, Naraha-machi, Tomioka-machi, Kawamata-machi Kawauchi-mura, Okuma-machi, Futaba-machi, Namie-machi, Kazurao-mura, Iitate-mura, Minami-soma City, Tamura City and the part of Date city specifically recommended for evacuation.

The residents aged 15 years or under have received health checks at 102 pediatric medical institutions in the prefecture since January 2011 (153 pediatricians agreed to be registered to conduct these comprehensive health checks).

The CHCs have also been performed outside the prefecture, with a total of 554 pediatric medical institutions helping to conduct health checks for children aged 15 years or younger.

Evaluation items

In addition to assessing the effects of radiation, additional variables were specified according to age in order to assess health, prevent lifestyle-related diseases, and identify or treat diseases at an early stage. The survey items for children aged 7 to 15 years consisted of height, weight, blood pressure, red blood cell (RBC) count, hematocrit (Hct), hemoglobin (Hb), platelet count, and white blood cell (WBC) count. Upon request, aspirate aminotransferase (AST), alanine aminotransferase (ALT), γ-glutamyl transpeptidase (γ-GTP), triglyceride (TG), high-density lipoprotein-cholesterol (HDL-C), low-density lipoprotein-cholesterol (LDL-C), hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c), fasting plasma glucose concentration, serum creatinine (Cr), and uric acid (UA) could be added. For children aged 0 to 6 years, height, weight, RBC count, Hct, Hb, platelet count, and WBC count were examined.

Definitions

Hypertension, anemia, liver dysfunction, hyperuricemia and hyperlipidemia were defined as previously reported9).

Statistics

Data are expressed as the mean values.

RESULTS

1) Baseline characteristics for residents aged 15 years or under who had lived in the evacuation zone (Table 1)

In 2011, 17,934 (64.5%) of the residents aged 15 years or younger received health checks, whereas 11,780 (43.5%) of those aged 15 years or younger received health checks in 2012. The numbers of residents aged 15 years or under who had lived in Hirono-machi, Naraha-machi, Tomioka-machi, Kawamata-machi Kawauchi-mura, Okuma-machi, Futaba-machi, Namie-machi, Kazurao-mura, Iitate-mura, Minami-soma City, Tamura City and the part of Date city are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

The number of residents aged 15 years or under who had lived in the evacuation zone in childhood.

| Date City |

Tamura City |

Minamisoma City |

Kawamata Machi |

Hirono Machi |

Naraha Machi |

Tomioka Machi |

|

| 0-6 years | 98 | 1,720 | 3,664 | 580 | 257 | 347 | 760 |

| 7-15 years | 200 | 3,503 | 6,078 | 1,190 | 515 | 688 | 1,431 |

| Kawauchi Mura |

Okuma Machi |

Futaba Machi |

Namie Machi |

Katsurao Machi |

Iitate Machi |

|

| 0-6 years | 88 | 777 | 362 | 1,016 | 53 | 280 |

| 7-15 years | 175 | 1,126 | 559 | 1,709 | 105 | 538 |

2) Body height, weight and blood pressure in residents aged 15 years or under who had lived in the evacuation zone (Table 2, 3, 4, 5,and 6)

1 Body height

Body height is shown in Table 2, 3, 4, and 5. Increases in body height were observed in males in the 1 year (Y) 2 month (M)-1Y6M , 1Y8M-1Y10M, and 2Y-14Y age groups in 2012 in comparison to the data for 2011, with gains in body height also observed in females in the 10M-1Y, 1Y2M-1Y6M, 2Y-2Y6M, 3Y-4Y6M, 5Y6M-9Y, 11Y, 13Y, and 15Y age groups in 2012 compared to 2011.

Table 2.

The mean body height of residents aged-less than 6 years old who had lived in the evacuation zone in 2011 and 2012.

| Age years (Y), month (M) | male | female | ||||||||

| 2011 | 2012 | (b)-(a) | 2011 | 2012 | (b)-(a) | |||||

| n | means (cm) (a) |

n | means (cm) (b) |

n | means (cm) (a) |

n | means (cm) (b) |

|||

| 10M-1Y | 44 | 73.6 | 46 | 73.3 | △0.3 | 36 | 71.5 | 49 | 72.0 | 0.5 |

| 1Y-1Y2M | 77 | 74.8 | 52 | 74.1 | △0.7 | 79 | 73.7 | 60 | 73.4 | △0.3 |

| 1Y2M-1Y4M | 68 | 76.5 | 64 | 77.2 | 0.7 | 85 | 75.1 | 41 | 75.2 | 0.1 |

| 1Y4M-1Y6M | 93 | 78.7 | 54 | 79.1 | 0.4 | 80 | 77.4 | 54 | 77.8 | 0.4 |

| 1Y6M-1Y8M | 80 | 81.2 | 59 | 80.2 | △1.0 | 78 | 78.9 | 53 | 78.9 | 0.0 |

| 1Y8M-1Y10M | 73 | 82.1 | 56 | 82.5 | 0.4 | 86 | 81.2 | 49 | 81.1 | △0.1 |

| 1Y10M-2Y | 83 | 83.8 | 52 | 83.7 | △0.1 | 98 | 82.0 | 52 | 81.8 | △0.2 |

| 2Y-2Y6M | 281 | 86.6 | 181 | 87.4 | 0.8 | 263 | 85.4 | 178 | 85.6 | 0.2 |

| 2Y6M-3Y | 269 | 90.7 | 196 | 91.4 | 0.7 | 288 | 89.9 | 199 | 89.7 | △0.2 |

| 3Y-3Y6M | 281 | 94.8 | 193 | 94.9 | 0.1 | 255 | 93.5 | 208 | 94.0 | 0.5 |

| 3Y6M-4Y | 257 | 98.6 | 170 | 99.0 | 0.4 | 246 | 97.3 | 181 | 97.4 | 0.1 |

| 4Y-4Y6M | 258 | 101.7 | 203 | 102.3 | 0.6 | 275 | 100.6 | 175 | 100.8 | 0.2 |

| 4Y6M-5Y | 280 | 105.7 | 193 | 105.7 | 0.0 | 253 | 104.2 | 192 | 103.9 | △0.3 |

| 5Y-5Y6M | 286 | 108.5 | 182 | 108.9 | 0.4 | 286 | 107.6 | 197 | 107.5 | △0.1 |

| 5Y6M-6Y | 293 | 111.4 | 199 | 111.9 | 0.5 | 296 | 110.3 | 191 | 111.1 | 0.8 |

Table 3.

The mean body weight of residents aged-less than 6 years old who had lived in the evacuation zone in 2011 and 2012.

| Age years (Y), month (M) | male | female | ||||||||

| 2011 | 2012 | (b)-(a) | 2011 | 2012 | (b)-(a) | |||||

| n | means (kg) (a) |

n | means (kg) (b) |

n | means (kg) (a) |

n | means (kg) (b) |

|||

| 10M-1Y | 44 | 9.8 | 46 | 9.4 | △0.4 | 36 | 8.9 | 49 | 8.7 | △0.2 |

| 1Y-1Y2M | 77 | 9.9 | 52 | 9.5 | △0.4 | 79 | 9.4 | 60 | 9.1 | △0.3 |

| 1Y2M-1Y4M | 68 | 10.4 | 64 | 10.2 | △0.2 | 85 | 9.7 | 41 | 9.4 | △0.3 |

| 1Y4M-1Y6M | 93 | 10.9 | 54 | 10.5 | △0.4 | 80 | 10.3 | 54 | 10.1 | △0.2 |

| 1Y6M-1Y8M | 80 | 11.2 | 59 | 11.2 | 0.0 | 79 | 10.5 | 53 | 10.4 | △0.1 |

| 1Y8M-1Y10M | 73 | 11.6 | 56 | 11.4 | △0.2 | 86 | 11.0 | 49 | 10.5 | △0.5 |

| 1Y10M-2Y | 83 | 12.0 | 52 | 11.6 | △0.4 | 98 | 11.2 | 52 | 10.8 | △0.2 |

| 2Y-2Y6M | 281 | 12.7 | 181 | 12.8 | 0.1 | 263 | 12.1 | 178 | 11.9 | △0.2 |

| 2Y6M-3Y | 269 | 13.8 | 196 | 13.5 | △0.3 | 288 | 13.2 | 199 | 12.9 | △0.3 |

| 3Y-3Y6M | 281 | 14.8 | 193 | 14.6 | △0.2 | 255 | 14.1 | 208 | 14.1 | 0.0 |

| 3Y6M-4Y | 257 | 15.9 | 170 | 15.7 | △0.2 | 246 | 15.2 | 181 | 15.0 | △0.2 |

| 4Y-4Y6M | 258 | 16.8 | 203 | 16.6 | △0.2 | 275 | 16.4 | 175 | 16.0 | △0.4 |

| 4Y6M-5Y | 280 | 17.9 | 193 | 17.8 | △0.1 | 253 | 17.2 | 193 | 17.0 | △0.2 |

| 5Y-5Y6M | 286 | 18.7 | 182 | 18.5 | △0.2 | 286 | 18.4 | 197 | 18.2 | △0.2 |

| 5Y6M-6Y | 293 | 20.0 | 199 | 19.9 | △0.1 | 296 | 19.3 | 191 | 19.6 | 0.3 |

Table 4.

The mean body height of residents aged-7-15 years old who had lived in the evacuation zone in 2011 and 2012.

| Age (years) |

male | female | ||||||||

| 2011 | 2012 | (b)-(a) | 2011 | 2012 | (b)-(a) | |||||

| n | means (cm) (a) |

n | means (cm) (b) |

n | means (cm) (a) |

n | means (cm) (b) |

|||

| 6 | 584 | 116.6 | 383 | 116.6 | 0.0 | 533 | 115.6 | 391 | 115.6 | 0.0 |

| 7 | 630 | 122.8 | 459 | 123.0 | 0.2 | 611 | 121.5 | 401 | 121.6 | 0.1 |

| 8 | 692 | 128.1 | 424 | 128.5 | 0.4 | 623 | 127.5 | 381 | 127.9 | 0.4 |

| 9 | 633 | 133.4 | 460 | 133.9 | 0.5 | 652 | 133.6 | 424 | 133.9 | 0.3 |

| 10 | 682 | 139.3 | 433 | 139.4 | 0.1 | 675 | 140.4 | 438 | 140.0 | △0.4 |

| 11 | 721 | 145.5 | 488 | 145.8 | 0.3 | 641 | 146.9 | 440 | 147.4 | 0.5 |

| 12 | 662 | 153.2 | 438 | 153.3 | 0.1 | 641 | 152.2 | 389 | 152.1 | △0.1 |

| 13 | 568 | 160.1 | 386 | 160.6 | 0.5 | 645 | 154.6 | 400 | 154.9 | 0.3 |

| 14 | 621 | 165.3 | 327 | 165.7 | 0.4 | 610 | 156.4 | 357 | 156.4 | 0.0 |

| 15 | 512 | 168.4 | 223 | 168.2 | △0.2 | 563 | 157.0 | 225 | 157.3 | 0.3 |

Table 5.

The mean body weight of residents aged-7-15 years old who had lived in the evacuation zone in 2011 and 2012.

| Age (years) |

male | female | ||||||||

| 2011 | 2012 | (b)-(a) | 2011 | 2012 | (b)-(a) | |||||

| n | means (kg) (a) |

n | means (kg) (b) |

n | means (kg) (a) |

n | means (kg) (b) |

|||

| 6 | 584 | 22.1 | 383 | 21.5 | △0.6 | 533 | 21.7 | 391 | 21.1 | △0.6 |

| 7 | 632 | 24.8 | 459 | 24.8 | 0.0 | 611 | 24.1 | 401 | 24.0 | △0.1 |

| 8 | 692 | 28.4 | 424 | 28.0 | △0.4 | 623 | 27.4 | 381 | 27.2 | △0.2 |

| 9 | 633 | 32.6 | 460 | 32.2 | △0.4 | 652 | 31.0 | 424 | 31.3 | 0.3 |

| 10 | 682 | 36.0 | 433 | 35.9 | △0.1 | 675 | 35.7 | 438 | 34.8 | △0.9 |

| 11 | 721 | 40.5 | 488 | 40.7 | 0.2 | 641 | 40.5 | 440 | 40.7 | 0.2 |

| 12 | 662 | 46.9 | 438 | 45.4 | △1.5 | 641 | 45.8 | 389 | 44.0 | △1.8 |

| 13 | 568 | 51.2 | 386 | 51.5 | 0.3 | 645 | 48.5 | 400 | 47.4 | △1.1 |

| 14 | 621 | 56.1 | 327 | 56.1 | 0.0 | 610 | 51.8 | 357 | 50.7 | △1.1 |

| 15 | 512 | 60.0 | 223 | 58.7 | △1.3 | 563 | 53.5 | 225 | 51.7 | △1.8 |

2 Body weight

Decreased body weight was observed in males in the 10M-1Y6M, 1Y8M-2Y, 2Y6M-6Y, 8Y-10Y, 12Y, and 15Y age groups in 2012 in comparison to the data for 2011, with decreases in body weight also observed in females in the 10M-3Y, 3Y6M-5Y6M, 6-8Y, 10Y, and 12Y-15Y age groups in 2012 compared to 2011.

3 blood pressure

With regard to blood pressure, the prevalence of high systolic BP or high diastolic BP in the male residents in 2011 was 0.9% and 0.8%, respectively, in the 7-15Y age group, while in the female residents it was 0.2% and 0.4%, respectively, in the 7-15 Y age group. In 2012, the prevalence of high systolic BP or high diastolic BP in the male residents was 0.4% and 0.4%, respectively, in the 7-15 Y age group, while in the female residents it was 0.1% and 0.3%, respectively, in the 7-15 Y age group (Table 6). In addition, the prevalence of hypertension in both the male and female residents in the 7-15 Y age group in 2012 was lower than that in male and female residents in 2011.

Table 6.

lood pressure in residents aged-7-15 years old who had lived in the evacuation zone in 2011 and 2012.

| Systolic BP (mmHg) | Diastolic BP (mmHg) | ||||||

| n | means | ≥140 | n | means | ≥90 | ||

| 2011 | male | 5,728 | 108.6 | 0.9% | 5,727 | 62.6 | 0.8% |

| female | 5,686 | 106.3 | 0.2% | 5,684 | 62.2 | 0.4% | |

| 2012 | male | 3,778 | 106.2 | 0.4% | 3,778 | 61.2 | 0.4% |

| female | 3,601 | 104.1 | 0.1% | 3,601 | 60.6 | 0.3% | |

3) Peripheral blood data for residents aged 15 years or under who had lived in the evacuation zone (Table 7 and 8)

In 2011, the prevalence of anemia in the male residents was 24.5% in the 0-6 Y and 3.8% in the 7-15 Y age group, while that in the female residents was 3.1% in the 0-6 Y, and 1.6% in the 7-15 Y age group. Similarly, the prevalence of anemia in the male residents in 2012 was 25.3% in the 0-6 Y and 3.2% in the 7-15 year age group, while that in female residents was 3.2% in the 0-6 Y and 1.0% in the 7-15 year age group. There were no differences in the prevalence of anemia, peripheral WBC counts, including neutrophils and lymphocytes, or platelet counts among age groups or between males and females in both 2011 and 2012.

Table 7.

RBC counts, Hg, Hct, and platelet counts in residents aged-0-15 years old who had lived in the evacuation zone.

| Age (years) | Sex | RBC counts (106/μl) | Hb (g/dL) | Hct (%) | Platlet counts (103/μl) | ||||||||||||||||||

| male | n | means | ≤3.69 | ≤3.99 | ≥5.80 | n | means | ≤12.0 | ≤13.0 | ≥18.0 | n | means | ≤35.9 | ≤37.9 | ≥55.0 | n | means | ≤89 | ≤129 | ≥370 | ≥450 | ||

| female | ≤3.39 | ≤3.69 | ≥5.50 | ≤11.0 | ≤12.0 | ≥16.0 | ≤28.9 | ≤32.9 | ≥48.0 | ||||||||||||||

| 2011 | 0-6 | male | 3,253 | 4.72 | 0.0% | 0.6% | 0.2% | 3,253 | 12.5 | 24.5% | 74.2% | 0.0% | 3,253 | 37.2 | 28.4% | 64.4% | 0.0% | 3,251 | 321.2 | 0.3% | 0.5% | 22.3% | 6.4% |

| female | 3,175 | 4.68 | 0.1% | 0.1% | 0.9% | 3,175 | 12.6 | 3.1% | 23.8% | 0.0% | 3,175 | 37.4 | 0.2% | 2.1% | 0.0% | 3,172 | 322.5 | 0.2% | 0.4% | 22.7% | 5.7% | ||

| 2012 | 0-6 | male | 2,166 | 4.72 | 0.0% | 0.9% | 0.4% | 2,166 | 12.6 | 25.3% | 71.4% | 0.0% | 2,166 | 37.6 | 24.1% | 56.6% | 0.0% | 2,164 | 321.1 | 0.1% | 0.3% | 22.8% | 6.0% |

| female | 2,176 | 4.67 | 0.0% | 0.0% | 0.9% | 2,176 | 12.6 | 3.2% | 23.1% | 0.0% | 2,176 | 37.9 | 0.1% | 1.4% | 0.0% | 2,172 | 325.4 | 0.3% | 0.6% | 24.0% | 6.7% | ||

| 2011 | 7-15 | male | 5,765 | 7.91 | 0.0% | 0.3% | 1.1% | 5,765 | 13.8 | 3.8% | 24.9% | 0.0% | 5,765 | 40.9 | 5.2% | 19.0% | 0.0% | 5,763 | 277.4 | 0.0% | 0.1% | 7.2% | 1.0% |

| female | 5,709 | 4.69 | 0.0% | 0.1% | 0.8% | 5,710 | 13.3 | 1.6% | 7.6% | 0.1% | 5,710 | 39.8 | 0.2% | 0.9% | 0.1% | 5,708 | 273.5 | 0.1% | 0.3% | 5.6% | 0.8% | ||

| 2012 | 7-15 | male | 3,809 | 4.90 | 0.0% | 0.3% | 0.7% | 3,809 | 13.8 | 3.2% | 21.9% | 0.0% | 3,809 | 41.3 | 2.8% | 12.9% | 0.0% | 3,807 | 276.3 | 0.0% | 0.3% | 6.1% | 0.6% |

| female | 3,626 | 4.70 | 0.0% | 0.1% | 0.6% | 3,626 | 13.4 | 1.0% | 6.2% | 0.2% | 3,626 | 40.4 | 0.0% | 0.4% | 0.2% | 3,624 | 273.6 | 0.0% | 0.1% | 5.7% | 0.5% | ||

Table 8.

WBC counts, including neutrophil counts, lymphocyte counts, basophil counts, monocyte counts, and eosinophil counts, in residents aged-0-15 years old who had lived in the evacuation zone in childhood.

| Age (years) | Sex | WBC counts (103/μl) | Neutrophils counts (/μl) |

Lymphocyte counts (/μl) |

Basophils counts (/μl) | Monocyte counts (/μl) | Eosinophils counts (/μl) | |||||||||||||

| n | means | ≤2.9 | ≤3.9 | ≥9.6 | ≥11.1 | n | means | ≤500 | n | means | ≤500 | n | means | n | means | n | means | |||

| 2011 | 0-6 | male | 3,253 | 8.5 | 0.1% | 0.7% | 28.3% | 12.9% | 3,247 | 3,683 | 0.0% | 3,247 | 4,055 | 0.0% | 3,247 | 38 | 3,247 | 454 | 3,247 | 250 |

| female | 3,176 | 8.5 | 0.1% | 0.4% | 27.9% | 13.0% | 3,171 | 3,649 | 0.1% | 3,171 | 4,214 | 0.0% | 3,171 | 35 | 3,171 | 426 | 3,171 | 195 | ||

| 2012 | 0-6 | male | 2,166 | 8.6 | 0.0% | 0.3% | 29.3% | 13.2% | 2,158 | 3,555 | 0.1% | 2,158 | 4,202 | 0.0% | 2,158 | 40 | 2,158 | 460 | 2,158 | 316 |

| female | 2,176 | 8.6 | 0.1% | 0.5% | 29.0% | 13.5% | 2,162 | 3,521 | 0.0% | 2,162 | 4,321 | 0.0% | 2,162 | 37 | 2,162 | 431 | 2,162 | 261 | ||

| 2011 | 7-15 | male | 5,765 | 6.5 | 0.2% | 3.4% | 6.0% | 2.1% | 5,762 | 3,321 | 0.0% | 5,762 | 2,533 | 0.1% | 5,762 | 433 | 5,762 | 366 | 5,762 | 244 |

| female | 5,710 | 6.5 | 0.2% | 4.0% | 5.7% | 1.8% | 5,708 | 3,425 | 0.0% | 5,708 | 2,514 | 0.1% | 5,708 | 29 | 5,708 | 343 | 5,708 | 185 | ||

| 2012 | 7-15 | male | 3,809 | 6.5 | 0.2% | 2.7% | 6.5% | 2.2% | 3,806 | 0.0% | 0.0% | 3,806 | 2,582 | 0.0% | 3,806 | 36 | 3,806 | 362 | 3,806 | 304 |

| female | 3,626 | 6.5 | 0.2% | 2.5% | 5.4% | 1.8% | 3,623 | 3,341 | 0.0% | 3,623 | 2,569 | 0.0% | 3,623 | 30 | 3,623 | 337 | 3,623 | 226 | ||

4) Biochemical laboratory findings for residents aged 15 years or under who had lived in the evacuation zone (Table 9, 10, and 11)

With regard to lipid function, the prevalence of high LDL-C or high TG values in the male residents in 2011 was 3.3% and 7.7%, respectively, in the 7-15 Y age group, and 3.6% and 6.3%, respectively, in the 7-15 Y age group in females. In 2012, the prevalence of high LDL-C or high TG values was 3.2% and 7.7%, respectively, in the 7-15 Y age group in males, and 3.6% and 6.5%, respectively, in the 7-15 Y age group in females. There were no significant differences in the prevalence of high LDL-C and high TG values in the 7-15 year age group in both males and females between 2012 and 2011 (Table 9).

Table 9.

LDL-C, triglyceride, and HLD-C values in residents aged-7-15 years old who had lived in the evacuation zone in childhood.

| HDL-C (mg/dL) | Triglyceride (mg/dL) | LDL-C (mg/dL) | ||||||||||

| n | means | <40 | n | means | ≥150 | ≥300 | n | means | ≥120 | ≥140 | ||

| 2011 | male | 5,586 | 62.2 | 3.1% | 5,584 | 75.5 | 7.7% | 0.6% | 5,587 | 91.9 | 11.7% | 3.3% |

| female | 5,515 | 62.7 | 2.8% | 5,507 | 77.5 | 6.3% | 0.5% | 5,511 | 96.3 | 14.8% | 3.6% | |

| 2012 | male | 3,711 | 61.4 | 3.1% | 3,711 | 75.9 | 7.7% | 0.6% | 3,710 | 91.9 | 10.7% | 3.2% |

| female | 3,532 | 61.1 | 2.3% | 3,531 | 78.1 | 6.5% | 0.7% | 3,530 | 95.6 | 13.9% | 3.6% | |

In terms of liver function, the prevalence of high AST, ALT, and γ-GTP values in males in 2011 was 12.8%, 7.0% and 1.0%, respectively, in the 7-15 Y age group, and 6.4%, 2.0% and 0.2%, respectively, in the 7-15 Y age group in females. In 2012, the prevalence in males was 14.1%, 7.4% and 0.7%, respectively, in the 7-15 Y age group, while in females it was 7.0%, 2.0% and 0.1%, respectively, in the 7-15 Y age group. The prevalence of high AST or ALT values in males in the 7-15 Y age group in 2012 was slightly increased compared to the frequencies observed in 2011, and the prevalence of high AST values in female in the 7-15 Y age group in 2012 was slightly increased compared to the values observed in 2011. On the other hand, the prevalence of high γ-GTP values in male and female residents aged 7-15 Y in 2012 was slightly decreased compared to the values observed in 2011 (Table 10).

Table 10.

Liver function and uric acid levels in residents aged-7-15 years old who had lived in the evacuation zone in childhood.

| AST (U/l) | ALT (U/l) | γ-GT (U/l) | Uric acid (mg/dL) | ||||||||||||||

| n | means | ≥31 | ≥51 | n | means | ≥31 | ≥51 | n | means | ≥51 | ≥101 | n | means | ≥7.1 | ≥8.0 | ||

| 2011 | male | 5,588 | 25.1 | 12.8% | 1.3% | 5,588 | 17.8 | 7.0% | 2.6% | 5,587 | 16.0 | 1.0% | 0.1% | 5,584 | 4.8 | 4.7% | 1.2% |

| female | 5,515 | 22.0 | 6.4% | 0.4% | 5,515 | 13.6 | 2.0% | 0.7% | 5,514 | 13.2 | 0.2% | 0.0% | 5,507 | 4.3 | 0.3% | 0.1% | |

| 2012 | male | 3,711 | 25.6 | 14.1% | 1.2% | 3,711 | 17.8 | 7.4% | 2.2% | 3,710 | 16.0 | 0.7% | 0.2% | 3,704 | 5.0 | 6.1% | 2.0% |

| female | 3,532 | 22.6 | 7.0% | 0.5% | 3,532 | 13.5 | 2.0% | 0.5% | 3,532 | 13.3 | 0.1% | 0.0% | 3,528 | 4.4 | 0.6% | 0.2% | |

The prevalence of hyperuricemia in the male residents in 2011 was 4.7% in the 7-15 Y age group, and 0.3% in females in the 7-15 Y age group. The 2012 data reveal that the prevalence of hyperuricemia in the male residents was 6.1% in the 7-15 Y age group, while in females it was 0.6% in the 7-15 Y age group. Hyperuricemia was more common in males than in females aged 7-15 Y in both 2011 and 2012. The prevalence of hyperuricemia in the 7-15 Y age group in both males and females in 2012 was slightly increased compared to the values in 2011 (Table 10).

With regard to fasting plasma glucose concentration and HbA1c levels, the prevalence of high fasting plasma glucose concentration and HbA1c values was 2.4% and 1.2%, respectively, in the 7-15 Y age group in males, and 2.3% and 0.9%, respectively, in females. In 2012, high fasting plasma glucose concentration and HbA1c values were observed in 0.7% and 0.8%, respectively, of males in the 7-15 Y age group, with the respective values among females being 0.6% and 0.5% in the 7-15 Y age group. The prevalence of high HbA1c values in the 7-15 Y age group for both males and females in 2012 were slightly decreased compared to the values recorded in 2011(Table 11).

Table 11.

Fasting blood sugar, HbA1c levels, and serum creatinine in residents aged-7-15 years old who had lived in the evacuation zone in childhood.

| Sex | Fasting plasma glucose concentration (mg/dL) |

HbA1c (%) (NGSP) | Serum creatinine (mg/dL) | ||||||||||||

| male | n | means | ≥110 | ≥130 | ≥160 | n | means | ≥6.0 | ≥7.0 | ≥8.0 | n | means | ≥1.15 | ≥1.35 | |

| female | ≥0.98 | ≥1.15 | |||||||||||||

| 2011 | male | 5,569 | 89.4 | 2.4% | 0.3% | 0.1% | 5,578 | 5.3 | 1.2% | 0.1% | 0.1% | 5,588 | 0.49 | 0.0% | 0.0% |

| female | 5,494 | 87.7 | 2.3% | 0.3% | 0.1% | 5,506 | 5.3 | 0.9% | 0.1% | 0.0% | 5,512 | 0.45 | 0.0% | 0.0% | |

| 2012 | male | 2,908 | 87.1 | 0.7% | 0.0% | 0.0% | 3,711 | 5.3 | 0.8% | 0.1% | 0.1% | 3,694 | 0.49 | 0.0% | 0.0% |

| female | 2,779 | 85.4 | 0.6% | 0.1% | 0.0% | 3,527 | 5.3 | 0.5% | 0.1% | 0.0% | 3,518 | 0.46 | 0.0% | 0.0% | |

As to renal function, the prevalence of high serum creatinine was 0.0% in the 7-15 Y age group in both males and females in both 2011 and 2012 (Table 11).

DISCUSSION

The Great East Japan Earthquake and Fukushima Daiichi nuclear disaster forced people to evacuate their homes without notice, caused them to change their lifestyle in terms of diet, exercise patterns, and other personal habits, to adapt to a completely new situation, and produced a good deal of anxiety with regard to radiation exposure. In response to this situation, the Fukushima prefectural government made the decision to implement what they termed FHMS to assist in the long-term health management of residents and to evaluate the health impact of the nuclear disaster and forced evacuation. However, to date, there have been no reports on the health checks implemented for residents aged 15 years or under living in the evacuation zones at the time of the disasters.

We previously reported that, among the adult residents living in the evacuation zone, a certain number of both males and females aged 16 years or older demonstrated obesity or hyperlipidemia, and the prevalence of these conditions was seen to increase with age in 2011. In addition, some males aged 16 years or older were found to have hyperuricemia and liver dysfunction, and the prevalence of hyperuricemia and liver dysfunction also increased with age. Furthermore, the prevalence of hypertension, glucose metabolic abnormalities and renal dysfunction was found to increase in those aged 40 years or older9). The above results also show that, among the child residents who were living in the evacuation zone at the time of the disaster, a number of males and females aged 15 years or younger demonstrated hyperlipidemia and some males aged 15 years or younger were found to have hyperuricemia and liver dysfunction. Furthermore, hypertension and glucose metabolic abnormalities were common among the 7-15 Y age group. We believe that these findings may be associated with changes in the residents’ lifestyle, diet, exercise patterns, mental stress levels, and sleep patterns in childhood, as shown in our report on adult health. However, there is no data available on the laboratory findings for pediatric residents who were living in the evacuation zone before the Great East Japan Earthquake, so a comparison of health status among the pediatric population before and after the Great East Japan Earthquake is not possible.

A comparison of body height and body weight between 2011 and 2012 showed that mean body height was increased and mean body weight decreased in both males and females in 2012 in comparison to 2011. These results suggest a tendency toward obesity in children who were living in the evacuation zone in 2011 after the Great East Japan Earthquake. To evaluate the body weight gains, it is necessary to further investigate changes in body weight on long-term basis.

In addition, the prevalence of hypertension and glucose metabolic abnormalities in 2012 was lower than that in 2011. Furthermore, the prevalence of high γ-GTP values in male and female residents aged 7-15 Y in 2012 was slightly decreased compared to the values observed in 2011. These results show that these changes, including hypertension and glucose metabolic abnormalities, obesity, and high γ-GTP values, improved from 2011 to 2012. However, the prevalence of hyperuricemia in both males and females in the 7-15 Y age group in 2012 was slightly higher than that in the respective age groups in 2011, and the prevalence of high TG values in 2012 was similar to that in 2011, suggesting that there was no improvement in these findings from 2011 to 2012. In addition, there were no differences in the prevalence of anemia or in peripheral WBC counts, including neutrophils and lymphocytes, or platelet counts between 2011 and 2012. These results indicate that it is necessary to continue our observation of these residents through health checks and to use the data obtained to improve their lifestyle.

Lifestyle-related diseases, including obesity and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), are a major health problem, and their incidence is increasing worldwide10). Mutsuhashi et al. observed that the prevalence of overweight children was 3.12% among those aged 6 years in 1985, from which time it steadily increased to 4.68% in 200511). In addition, pediatric NAFLD has increased in line with the increased prevalence of pediatric obesity and has become an important health problem worldwide. It is also reported that the prevalence of obesity and NAFLD in elementary school children in increasing.12,13)

Thus, to evaluate the frequency of children with lifestyle-related diseases including obesity and/or NAFLD more precisely, it is necessary to compare the number of pediatric patients with lifestyle-related diseases between the population living in the evacuation zone and the general population.

The frequency of residents aged 15 years or younger who received health checks in 2011 was 64.5%, while that in 2012 was only 43.5%, which appears to indicate a decrease in interest in the health checks provided by the Fukushima Health Management Survey. This decrease in the number of child residents who received health checks could affect the results of our study and it is, therefore, necessary to encourage interest in these health checks through advertising and better education.

With regard to the limitations of our study, although there was no change in the criteria for residents aged 15 years or under targeted for health checks between 2011 and 2012, the actual pediatric residents who received health checks, the time at which they received the health checks and the medical institutions offering the health checks all varied between 2011 and 2012. Thus, a simple comparison of the data from 2011 and 2012 using statistical analysis was not feasible. To evaluate the health impacts of the disaster and forced evacuation more accurately, it is necessary to evaluate changes in the health status of the residents aged 15 years or under receiving the health checks in both 2011 and 2012 based on the results of the health checks. In addition, it is necessary to accumulate laboratory data from the comprehensive health checks over a long-term follow-up period and the prevention of each disease, including lifestyle-related diseases, should be considered independently on the basis of the long-term data.

In conclusion, these findings presented herein suggest that a number of children living in the evacuation zone at the time of the disaster suffered from a variety of conditions including obesity, hyperlipidemia, hyperuricemia, liver dysfunction, hypertension, and glucose metabolic abnormalities. We, therefore, believe that it is necessary to continue with the health checks for these residents aged 15 years or under in order to assist in resolving the observed lifestyle-related diseases.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This survey was supported by the National Health Fund for Children and Adults Affected by the Nuclear Incident. The findings and conclusions of this article are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not represent the official views of the Fukushima Prefecture government.

APPENDIX

The Fukushima Health Management Survey Group

Hitoshi Ohto, Masafumi Abe, Shunichi Yamashita, Kenji Kamiya, Seiji Yasumura, Mitsuaki Hosoya, Akira Ohtsuru, Akira Sakai, Shinichi Suzuki, Hirooki Yabe, Masaharu Maeda, Shirou Matsui, Keiya Fujimori, Tetsuo Ishikawa, Tetsuya Ohira, Tsuyoshi Watanabe, Hiroaki Satoh, Hitoshi Suzuki, Yukihiko Kawasaki, Atsushi Takahashi, Kotaro Ozasa, Gen Kobashi, Shigeatsu Hashimoto, Satoru Suzuki, Toshihiko Fukushima, Sanae Midorikawa, Hiromi Shimura,Hirofumi Mashiko, Aya Goto, Kenneth Eric Nollet, Shinichi Niwa, Hideto Takahashi, and Yoshisada Shibata

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

We have no conflicting interests affecting the present study.

REFERENCES

- 1.Japan Meteorological Agency. The 2011 off the Pacific coast of Tohoku earthquake (http://seisvol.kishou.go.jp/eq/2011)

- 2.National Police Agency of Japan. Damage situation and police countermeasures (www.npa.go.jp/archive/keibi/biki/higaijokyo_e.pdf)

- 3.Monthly Report on Earthquakes and Volcanoes in Japan. Meteorological Agency, 2011.

- 4.Sakai A, Ohira T, Hosoya M, et al. Life as an ecacuee after the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant accident is a cause of polycythemia: the Fukushima Health Management Survey. BMC Public Health, 14: 1318, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Simons M, Minson SE, Sladen A et al. The 2011 magnitude 9.0 Tohoku-Oki earthquake: mosaicking the megathrust from seconds to centuries. Science, 332: 1421-1425, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.The Report on Damage from the East Japan Earthquake. National Police Agency, 2012.

- 7.Shimura T, Yagaguchi I, Terada H, et al. Radiation occupational health interventions offered to radiation workers in response to the complex catastrophic disaster at the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant. Journal of Radiation Research, 2014;pp. 1- 9 doi: 10.1093/jrr/rru110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yasumura S, Hosoya M, Yamashita S, Kamiya K, Abe M, Akashi M, Kodama K, Ozasa K, for the Fukushima Health Management Survey Group. Study Protocol for the Fukushima Health Management Survey. J Epidemiol, 22: 375-383, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kawasaki Y, Hosoya M, Yasumura S, Ohira T, Satoh H, Suzuki H, Sakai A, Ohtsuru A, Takahashi A, Ozasa K, Kobashi G, Kamiya K, Yamashita S, Abe M, and the Fukushima Health Management Survey Group. The Basic Data for residents aged 16 years or older who received a Comprehensive Health Check examinations in 2011-2012 as a part of the Fukushima Health Management Survey after the Great East Japan Earthquake. Fukushima J Med Sci, 60: 159- 169, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Berg C, Rosengren A, Aires N, Lappas G, Torén K, Thelle D, Lissner L. Trends in overweight and obesity from 1985 to 2002 in Göteborg, West Sweden. Int J Obes (Lond)., 29: 916- 924, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mitsuhashi T, Suzuki E, Takao S, et al. maternal working hours and early childhood overweight in Japan: A population-based study. J Occup Health, 54: 25-33, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Takahashi Y, Fukusato T. Pediatric nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: overview with emphasis on histology. World Journal of Gastroenterology, 16: 5280-5285, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yoshinaga M, Shimago A, Koriyama C, Nomura Y, Miyata K, Hashiguchi J, Arima K. Rapid increase in the prevalence of obesity in elementary school children. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord, 28: 494-499, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]