Abstract

BACKGROUND

The addition of azithromycin to standard regimens for antibiotic prophylaxis before cesarean delivery may further reduce the rate of postoperative infection. We evaluated the benefits and safety of azithromycin-based extended-spectrum prophylaxis in women undergoing nonelective cesarean section.

METHODS

In this trial conducted at 14 centers in the United States, we studied 2013 women who had a singleton pregnancy with a gestation of 24 weeks or more and who were undergoing cesarean delivery during labor or after membrane rupture. We randomly assigned 1019 to receive 500 mg of intravenous azithromycin and 994 to receive placebo. All the women were also scheduled to receive standard antibiotic prophylaxis. The primary outcome was a composite of endometritis, wound infection, or other infection occurring within 6 weeks.

RESULTS

The primary outcome occurred in 62 women (6.1%) who received azithromycin and in 119 (12.0%) who received placebo (relative risk, 0.51; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.38 to 0.68; P<0.001). There were significant differences between the azithromycin group and the placebo group in rates of endometritis (3.8% vs. 6.1%, P = 0.02), wound infection (2.4% vs. 6.6%, P<0.001), and serious maternal adverse events (1.5% vs. 2.9%, P = 0.03). There was no significant between-group difference in a secondary neonatal composite outcome that included neonatal death and serious neonatal complications (14.3% vs. 13.6%, P = 0.63).

CONCLUSIONS

Among women undergoing nonelective cesarean delivery who were all receiving standard antibiotic prophylaxis, extended-spectrum prophylaxis with adjunctive azithromycin was more effective than placebo in reducing the risk of postoperative infection. (Funded by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development; C/SOAP ClinicalTrials.gov number, NCT01235546.)

GLOBALLY, PREGNANCY-ASSOCIATED IN-fection is a major cause of maternal death and is the fourth most common cause in the United States.1 Maternal infection is also associated with a prolonged hospital stay and increased health care costs.2,3 Cesarean delivery is the most common major surgical procedure4 and is associated with a rate of surgical-site infection (including endometritis and wound infection) that is 5 to 10 times the rate for vaginal delivery.5 Despite routine use of antibiotic prophylaxis (commonly, a cephalosporin given before skin incision6), infection after cesarean section remains an important concern, particularly among women who undergo nonelective procedures (i.e., unscheduled cesarean section during labor, after membrane rupture, or for maternal or fetal emergencies).6-12 As many as 60 to 70% of all cesarean deliveries are nonelective; postoperative infections occur in up to 12% of women undergoing non-elective cesarean delivery with standard preincision prophylaxis.13,14

Studies (including a single-center randomized trial) suggest that azithromycin-based extended-spectrum prophylaxis — a single dose of azithromycin plus standard cephalosporin prophylaxis — may result in a lower risk of infection after cesarean section than standard prophylaxis alone.15 It has been thought that the efficacy of such prophylaxis was due to coverage for ureaplasma species, which are commonly associated with infections after cesarean section.16-21 We performed this study to assess whether the addition of azithromycin to standard antibiotic prophylaxis before skin incision would reduce the incidence of infection after cesarean section without increasing the risk of other adverse maternal and perinatal outcomes.

METHODS

TRIAL DESIGN AND OVERSIGHT

The Cesarean Section Optimal Antibiotic Prophylaxis (C/SOAP) trial was a double-blind, pragmatic, randomized clinical trial conducted at 14 hospitals in the United States. The institutional review board at each study site approved the trial protocol, which is available with the full text of this article at NEJM.org. Written informed consent was obtained from all the patients. Funding was provided by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. Pfizer donated the azithromycin that was used in the trial but did not participate in the design, conduct, or reporting of the trial. An independent data and safety monitoring board oversaw the trial. The first two authors take responsibility for the accuracy and completeness of the reporting and the fidelity of the report to the trial protocol.

TRIAL DESIGN

Women with a singleton pregnancy with a gestation of 24 weeks or more who were undergoing nonelective cesarean delivery during labor or after membrane rupture were eligible. Labor was defined as regular contractions with cervical dilation of 4 cm or more or with documented cervical change of at least 1 cm of dilation or at least 50% effacement. Women with membrane rupture for at least 4 hours were eligible, regardless of whether labor had started. Most women underwent the consent procedure at admission for delivery and were rescreened to confirm eligibility after the decision was made to proceed to cesarean delivery. Gestational age was estimated in accordance with the guidelines of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.22

Exclusion criteria were an inability to provide consent, a known allergy to azithromycin, subsequent vaginal delivery, azithromycin use within 7 days before randomization, chorioamnionitis or other infection requiring postpartum antibiotic therapy (although patients receiving antibiotics for group B streptococcus were eligible), and fetal death or known major congenital anomaly. We also excluded patients who had substantial liver disease (cirrhosis or an aminotransferase level at least three times the upper limit of the normal range), a serum creatinine level of more than 2.0 mg per deciliter (177 μmol per liter) or the need for dialysis, diarrhea at the time of planned randomization, cardiomyopathy or pulmonary edema, maternal structural heart disease, arrhythmias, use of medications known to prolong the QT interval, or known substantial electrolyte abnormalities, such as hypokalemia, hypocalcemia, or hypomagnesemia.

All the women were to receive standard prophylaxis (cefazolin) according to the protocol at each trial center. Patients who were allergic to cephalosporin or penicillin received the local alternative medication (clindamycin alone or clindamycin plus gentamicin). Antibiotic prophylaxis was administered before surgical incision or as soon as possible thereafter.

INTERVENTIONS

Patients were randomly assigned to receive either azithromycin (at a dose of 500 mg in 250 ml of saline) or an identical-appearing saline placebo. Clinical and research staff members other than the investigational pharmacist were unaware of treatment assignments. The computer-generated block-designed randomization plan was produced by the data coordinating center and was stratified according to site. Only the investigational pharmacists who prepared the study drug had access to the randomization algorithm through a dedicated password-protected website.

The 250-ml bags containing the azithromycin or placebo were sequentially numbered and kept in a secure refrigerator (7-day shelf life), which allowed for rapid administration after randomization. (Expired study bags were discarded without recycling the randomization sequence.) Study staff members retrieved the next sequentially numbered study drug bag up to 1 hour before incision and typically once the decision was made to proceed to cesarean section. At the time that the study infusion was connected, the patient was considered to have undergone randomization. Study medication was infused over a period of 1 hour, according to Food and Drug Administration guidelines for azithromycin.

Cesarean procedures and care at each center followed providers’ usual practices. Trial outcomes and other data were abstracted by certified research staff.

TRIAL OUTCOMES

The primary outcome was a composite of endometritis, wound infection, or other infections (abdominopelvic abscess, maternal sepsis, pelvic septic thrombophlebitis, pyelonephritis, pneumonia, or meningitis) occurring up to 6 weeks after surgery. Endometritis was defined as the presence of at least two of the following signs with no other recognized cause: fever (temperature of at least 38°C [100.4°F]), abdominal pain, uterine tenderness, or purulent drainage from the uterus. Wound infection was defined as the presence of either superficial or deep incisional surgical-site infection characterized by cellulitis or erythema and induration around the incision or purulent discharge from the incision site with or without fever and included necrotizing fasciitis. Wound hematoma, seroma, or breakdown alone in the absence of the preceding signs did not constitute infection. Diagnosis of abdominal or pelvic abscess required radiologic or surgical confirmation. Detailed trial criteria consistent with the recommendations of the National Healthcare Safety Network of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention for surgical site infections are provided in the Supplementary Appendix, available at NEJM.org.23

Criteria for other infections, which included a clinical diagnosis leading to therapy with antibiotics and additional criteria, are provided in the Supplementary Appendix. Primary outcomes were centrally adjudicated by investigators who were unaware of treatment assignments.

A major secondary neonatal outcome was a composite of death, suspected or confirmed sepsis, or other complications, including the respiratory distress syndrome, necrotizing enterocolitis, periventricular leukomalacia, grade III or higher intraventricular hemorrhage, the systemic inflammatory response syndrome, and bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Other secondary outcomes that were specified in the statistical analysis plan included a neonatal safety composite (death, allergic reaction, or transfer to a long-term care facility), a maternal safety composite outcome (defined below as maternal serious adverse events), and infection with resistant organisms.

Other secondary maternal and neonatal outcomes that were specified in the protocol are listed in Table S1 in the Supplementary Appendix. Among such outcomes were specific maternal postoperative infections, maternal fever, unscheduled visits and readmissions, neonatal complications, and length of hospital stay.

Neonatal serious adverse events included the neonatal safety composite, grade III or higher intraventricular hemorrhage, sepsis, and other reported serious events. Maternal serious adverse events (maternal safety composite outcome) included death, suspected allergic reactions (including anaphylaxis or generalized skin rash), any serious adverse event leading to the discontinuation of a study medication or suspected to be due to the medication, and any other reported serious adverse complication, including pulmonary embolism, admission to an intensive care unit (ICU), and cardiac events.

OUTCOME ASCERTAINMENT AND FOLLOW-UP

Trained and certified research staff members who were unaware of treatment assignments ascertained maternal and infant outcomes by reviewing medical records from the delivery hospitalization, from visits to a postpartum clinic or emergency department, and from hospital admissions. Patients were scheduled for a 6-week postpartum visit (or were contacted by telephone) to ascertain maternal and infant medical events and visits and were contacted by telephone at 3 months to identify infant deaths and adverse events. Medical records (including those at other health facilities) were required to verify study outcomes.

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

We determined that a sample size of 2000 patients would provide a power of 80% to detect a 33% relative reduction in the primary outcome from a baseline risk of 12% or a 40% relative reduction from a baseline risk of 8%, at a two-sided alpha level of 0.05. We also calculated that this sample size would provide a power of 80% or more to assess a 30% relative reduction in the composite neonatal outcome, assuming a baseline risk of 16%.14

All analyses were performed according to the intention-to-treat principle. We used the chi-square test or Fisher's exact test to analyze categorical variables and Student's t-test for continuous variables. Relative risks and 95% confidence intervals were calculated for outcomes. In secondary analyses, we adjusted for characteristics that were not balanced at randomization using logistic-regression models for the primary outcome. Tests of interaction in multivariable logistic-regression models were used to test the homogeneity of the treatment effect on the primary outcome across subgroups in four prespecified analyses, according to trial site, body-mass index (the weight in kilograms divided by the square of the height in meters) of less than 30 versus 30 or more, membrane rupture before randomization versus after randomization, and initiation of study medication before versus after skin incision. We calculated the number of patients who would need to be treated to prevent one primary outcome event and 95% confidence intervals.

We performed one planned interim analysis of the primary outcome using O'Brien–Fleming boundaries; the final analysis was evaluated at a 0.048 level of significance. All secondary outcomes were evaluated at a 0.05 level of significance.

RESULTS

CHARACTERISTICS OF THE PATIENTS

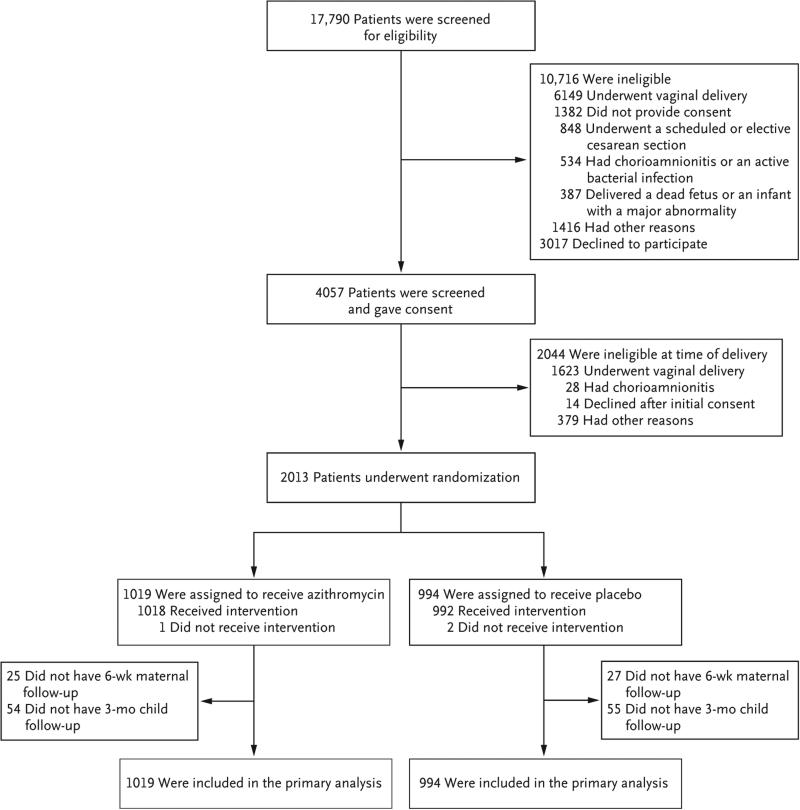

Of 17,790 women who were screened at the 14 clinical sites from April 2011 through November 2014, a total of 1019 were randomly assigned to the azithromycin group and 994 to the placebo group (Fig. 1). The characteristics of the patients at baseline were similar in the two groups, except that smoking was slightly less prevalent in the azithromycin group (Table 1). The specific characteristics related to the cesarean delivery, including indications for cesarean delivery, receipt of standard prophylaxis, timing of receipt of study medication, and type of surgical skin preparation, were similar in the two groups (Table 2). More than 99% of the patients in each group received the standard antibiotic prophylaxis. Azithromycin or placebo was administered before incision in 88% of the women in each group. Maternal and neonatal outcome data were available for all the patients at the time of hospital discharge. Postpartum follow-up within 6 weeks was available for 1961 of the 2013 women (97.4%) who underwent randomization (Fig. 1).

Figure 1. Enrollment and Outcomes.

In the azithromycin group, 1018 patients received the assigned drug, but data were missing on the timing of administration in 9. In the placebo group, 992 patients received the assigned saline infusion, but the timing was not documented in 11.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the Patients at Baseline.*

| Characteristic | Azithromycin (N = 1019) | Placebo (N = 994) |

|---|---|---|

| Age — yr | 28.2±6.1 | 28.4±6.5 |

| Race or ethnic group — no. (%)† | ||

| Non-Hispanic black | 351 (34.4) | 341 (34.3) |

| Hispanic | 203 (19.9) | 208 (20.9) |

| Non-Hispanic white | 356 (34.9) | 342 (34.4) |

| Other | 109 (10.7) | 103 (10.4) |

| Body-mass index‡ | ||

| Mean | 35.3±7.7 | 35.5±7.9 |

| Category — no. (%) | ||

| <18.5 | 1 (01) | 1 (01) |

| 18.5 to <25 | 53 (5.2) | 43 (4.3) |

| 25 to <30 | 217 (21.3) | 221 (22.2) |

| 30 to <40 | 503 (49.4) | 478 (48.1) |

| ≥40 | 243 (23.8) | 249 (25.1) |

| Missing data | 2 (0.2) | 2 (0.2) |

| Private insurance — no./total no. (%)† | 317/1008 (31.4) | 312/983 (31.7) |

| Previous pregnancy — no. (%) | ||

| Any | 552 (54.2) | 560 (56.3) |

| ≥20 wk of gestation | 416 (40.8) | 402 (40.4) |

| Diabetes mellitus — no. (%) | ||

| Any | 142 (13.9) | 146 (14.7) |

| Gestational only | 99 (9.7) | 106 (10.7) |

| Chronic hypertension — no. (%) | 51 (5.0) | 54 (5.4) |

| Smoking during pregnancy — no. (%) | 97 (9.5) | 122 (12.3) |

| Alcohol use during pregnancy — no. (%) | 41 (4.0) | 47 (4.7) |

| Use of illegal drugs during pregnancy — no. (%) | 35 (3.4) | 28 (2.8) |

| Positive for group B streptococcus — no. (%) | 249 (24.4) | 266 (26.8) |

| Gestational age | ||

| At randomization — wk | 38.9±2.3 | 39.0±2.3 |

| <37 wk at delivery — no. (%) | 112 (11.0) | 114 (11.5) |

Plus-minus values are means ±SD. There were no significant differences between the groups except for smoking during pregnancy (P=0.047). Percentages may not total 100 because of rounding.

Race or ethnic group was self-reported.

The body-mass index is the weight in kilograms divided by the square of the height in meters.

Table 2.

Characteristics of Cesarean Procedures.

| Characteristic | Azithromycin (N = 1019) | Placebo (N = 994) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| no./total no. (%) | |||

| Primary indication for cesarean delivery* | 0.97 | ||

| Failure to progress | 360/1019 (35.3) | 342/993 (34.4) | |

| Nonreassuring fetal heart tones | 268/1019 (26.3) | 258/993 (26.0) | |

| Failed induction | 105/1019 (10.3) | 103/993 (10.4) | |

| Elective repeat procedure meeting study criteria | 94/1019 (9.2) | 95/993 (9.6) | |

| Abnormal presentation | 59/1019 (5.8) | 67/993 (6.7) | |

| Other reason | 133/1019 (13.1) | 128/993 (12.9) | |

| Receipt of standard antibiotic prophylaxis | 1017/1019 (99.8) | 990/994 (99.6) | 0.45 |

| Timing of study-drug administration | |||

| Before skin incision† | 884/1009 (87.6) | 860/981 (87.7) | 0.97 |

| 0 to 60 min before | 833/1009 (82.6) | 815/981 (83.1) | |

| >60 min before | 51/1009 (5.1) | 45/981 (4.6) | |

| After incision | 125/1009 (12.4) | 121/981 (12.3) | |

| Membrane rupture before skin incision | 889/1012 (87.8) | 868/987 (87.9) | 0.95 |

| Skin-incision type | 0.10 | ||

| Pfannenstiel | 987/1019 (96.9) | 947/992 (95.5) | |

| Vertical | 32/1019 (3.1) | 45/992 (4.5) | |

| Closure method | 0.91 | ||

| Staples | 415/1019 (40.7) | 411/992 (41.4) | |

| Suture | 593/1019 (58.2) | 569/992 (57.4) | |

| Dermabond | 11/1019 (1.1) | 12/992 (1.2) | |

| Uterine incision | 0.99 | ||

| Low transverse | 975/1019 (95.7) | 949/992 (95.7) | |

| Other | 44/1019 (4.3) | 43/992 (4.3) | |

| Skin preparation | |||

| Chlorhexidine | 369/1019 (36.2) | 364/994 (36.6) | 0.78 |

| Chlorhexidine–alcohol | 340/1019 (33.4) | 316/994 (31.8) | |

| Chlorhexidine–alcohol plus iodine | 218/1019 (21.4) | 213/994 (21.4) | |

| Iodine–alcohol | 92/1019 (9.0) | 101/994 (10.2) | |

| Vaginal preparation | |||

| Any | 265/1019 (26.0) | 258/994 (26.0) | 0.98 |

| Type | |||

| Iodine | 254/1019 (24.9) | 243/994 (24.4) | 0.68 |

| Chlorhexidine | 11/1019 (1.1) | 15/994 (1.5) | |

| None | 754/1019 (74.0) | 736/994 (74.0) | |

One patient in the placebo group did not have a primary indication for cesarean delivery.

The P value for this category is for the between-group comparison for administration of the study drug before the incision versus administration after the incision.

PRIMARY OUTCOME

The primary composite outcome occurred in 62 women (6.1%) who received azithromycin and in 119 (12.0%) who received placebo (relative risk, 0.51; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.38 to 0.68; P<0.001) (Table 3). The use of azithromycin was associated with significantly lower rates of endometritis (3.8% vs. 6.1%; relative risk, 0.62; 95% CI, 0.42 to 0.92; P = 0.02) and wound infections (2.4% vs. 6.6%; relative risk, 0.35; 95% CI, 0.22 to 0.56; P<0.001). The risks of other infections were low and did not differ significantly between groups. The number of patients who would need to be treated to prevent one study outcome was 17 (95% CI, 12 to 30) for the primary outcome, 43 (95% CI, 24 to 245) for endometritis, and 24 (95% CI, 17 to 41) for wound infections. The results were similar after planned adjustment for smoking with respect to the primary outcome (adjusted odds ratio, 0.48; 95% CI, 0.35 to 0.66), endometritis (adjusted odds ratio, 0.61; 95% CI, 0.40 to 0.91), and wound infections (adjusted odds ratio, 0.34; 95% CI, 0.21 to 0.55). Results from survival analyses were also similar to the findings in the primary analysis (Table S2 and Figs. S1 through S4 in the Supplementary Appendix).

Table 3.

Primary Composite Outcome and Its Components.*

| Outcome | Azithromycin (N = 1019) | Placebo (N = 994) | Relative Risk (95% CI) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| no. (%) | ||||

| Primary composite outcome | 62 (6.1) | 119 (12.0) | 0.51 (0.38–0.68) | <0.001 |

| Endometritis | 39 (3.8) | 61 (6.1) | 0.62 (0.42–0.92) | 0.02 |

| Wound infection | 24 (2.4) | 66 (6.6) | 0.35 (0.22–0.56) | <0.001 |

| Necrotizing fasciitis | 0 | 4 (0.4) | NA | 0.06 |

| Deep wound infection | 6 (0.6) | 8 (0.8) | 0.73 (0.25–2.10) | 0.56 |

| Other infection | 3 (0.3) | 6 (0.6) | 0.49 (0.12–1.94) | 0.34 |

| Abdominal or pelvic abscess | 0 | 4 (0.4) | NA | 0.06 |

| Septic pelvic thrombophlebitis | 0 | 0 | NA | NA |

| Maternal sepsis | 2 (0.2) | 1 (0.1) | 1.95 (0.18–21.5) | >0.99 |

| Pyelonephritis | 1 (01) | 0 | NA | >0.99 |

| Pneumonia | 1 (0.1) | 2 (0.2) | 0.49 (0.04–5.37) | 0.62 |

| Meningitis | 0 | 0 | NA | NA |

NA denotes not applicable.

Heterogeneity of the effect of adjunctive azithromycin was not detected in prespecified subgroups, according to study site, obesity status, membrane status at randomization, and timing of medication administration (Table S3 in the Supplementary Appendix). A significant interaction was detected in a post hoc analysis of skin-closure methods (P = 0.02), which suggested a greater reduction in infections for women receiving staples than for those receiving sutures. No heterogeneity in treatment effect was detected in other post hoc subgroup analyses, including vaginal preparation, group B streptococcal status, diabetes status, and preterm delivery.

SECONDARY NEONATAL AND MATERNAL OUTCOMES

The composite neonatal outcome of death or complications occurred in 146 infants (14.3%) in the azithromycin group and in 135 (13.6%) in the placebo group (relative risk, 1.05; 95% CI, 0.85 to 1.31; P = 0.63) (Table 4). There was one neonatal death in the placebo group, which occurred 5 days after birth as a result of extreme prematurity, and three deaths in the azithromycin group, which occurred at 15 days from fulminant herpes simplex virus, at 42 days from uncertain cause, and at 72 days from the sudden infant death syndrome. The frequencies of other neonatal outcomes, including neonatal ICU admission or hospitalization after discharge, were not significantly different between groups. Other maternal outcomes, including rates of postpartum fever, treatment with antibiotics, and need for readmission or unscheduled visits for any reason or specifically for infection, were significantly less common in the azithromycin group (Table 4).

Table 4.

Secondary Neonatal and Maternal Outcomes.*

| Outcome | Azithromycin (N = 1019) | Placebo (N = 994) | Relative Risk (95% CI) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| no. of patients (%) | ||||

| Neonatal | ||||

| Composite neonatal outcome | 146 (14.3) | 135 (13.6) | 1.05 (0.85–1.31) | 0.63 |

| Sepsis | ||||

| Suspected | 120 (11.8) | 124 (12.5) | 0.94 (0.75–1.19) | 0.63 |

| Confirmed | 1 (01) | 1 (01) | 0.98 (0.06–15.6) | >0.99 |

| Death | ||||

| Within 3 mo | 3 (0.3) | 1 (01) | 2.93 (0.30–28.1) | 0.62 |

| Within 28 days | 1 (01) | 1 (01) | 0.98 (0.06–15.6) | >0.99 |

| Composite neonatal complications | 45 (4.4) | 34 (3.4) | 1.29 (0.83–2.00) | 0.25 |

| Respiratory distress syndrome | 42 (4.1) | 33 (3.3) | 1.24 (0.79–1.94) | 0.34 |

| Necrotizing enterocolitis | 1 (0.1) | 0 | NA | >0.99 |

| Periventricular leukomalacia | 0 | 0 | NA | NA |

| Intraventricular hemorrhage of grade III or more | 1 (0.1) | 2 (0.2) | 0.49 (0.04–5.37) | 0.62 |

| Bronchopulmonary dysplasia | 4 (0.4) | 3 (0.3) | 1.30 (0.29–5.80) | >0.99 |

| Systemic inflammatory response syndrome | 0 | 1 (0.1) | NA | 0.493 |

| NICU admission | 171 (16.8) | 169 (17.0) | 0.99 (0.81–1.20) | 0.89 |

| Readmission or unscheduled visit | 170 (16.7) | 140 (14.1) | 1.18 (0.96–1.46) | 0.11 |

| Readmission | 39 (3.8) | 43 (4.3) | 0.88 (0.58–1.35) | 0.57 |

| Maternal | ||||

| Postpartum fever | 51 (5.0) | 81 (8.1) | 0.61 (0.44–0.86) | 0.004 |

| Any postpartum readmission or unscheduled visit | 83 (8.1) | 123 (12.4) | 0.66 (0.51–0.86) | 0.002 |

| Clinic visit | 32 (3.1) | 53 (5.3) | 0.59 (0.38–0.91) | 0.02 |

| Emergency department visit | 54 (5.3) | 84 (8.5) | 0.63 (0.45–0.87) | 0.005 |

| Readmission | 27 (2.6) | 49 (4.9) | 0.54 (0.34–0.85) | 0.007 |

| Because of infection | 23 (2.3) | 62 (6.2) | 0.36 (0.23–0.58) | <0.001 |

| Postpartum use of antibiotics | 126 (12.4) | 166 (16.7) | 0.74 (0.60–0.92) | 0.006 |

| Composite serious adverse events† | ||||

| Neonatal serious adverse events | ||||

| Any | 7 (0.7) | 5 (0.5) | 1.37 (0.43–4.29) | 0.77 |

| Safety composite‡ | 3 (0.3) | 1 (01) | 2.93 (0.30–28.1) | 0.62 |

| All maternal serious adverse events§ | 15 (1.5) | 29 (2.9) | 0.50 (0.27–0.94) | 0.03 |

NA denotes not applicable, and NICU neonatal intensive care unit.

Details about serious adverse events are provided in Table S4 in the Supplementary Appendix.

This category is a composite of perinatal death, perinatal allergic reaction, and neonatal transfer to a chronic care facility.

This category is the same as the maternal safety composite.

ADVERSE EVENTS

Maternal serious adverse events were less common in the azithromycin group than in the placebo group (1.5% vs. 2.9%, P = 0.03); no significant between-group difference was observed in the rates of neonatal serious adverse events, including the safety composite outcome (Table 4). Other maternal or neonatal adverse events did not differ significantly between groups (Tables S4 and S5 in the Supplementary Appendix).

BACTERIAL CULTURES AND ANTIMICROBIAL RESISTANCE

We examined results of all clinical maternal postpartum cultures in those with wound infections (Table S6 in the Supplementary Appendix). Fifty women (2.5%) had cultures that were positive for at least one bacterial organism, most commonly gram-negative bacilli and staphylococcus and enterococcus species. The azithromycin group had a significantly lower prevalence than the placebo group with respect to positive cultures (1.4% vs. 3.6%, P = 0.001) and bacteria resistant to at least one antibiotic (1.0% vs. 2.4%, P = 0.01). Bacteria resistant to azithromycin were identified in three wound cultures in the azithromycin group and four in the placebo group. Overall, 19 newborns (0.9%) had positive culture results (mainly in blood samples), with no significant between-group difference in the prevalence (8 newborns [0.8%] in the azithromycin group and 11 [1.1%] in the placebo group [P = 0.50]) or in the prevalence of bacteria resistant to at least one antibiotic (0.5% vs. 0.8%, P = 0.42).

SENSITIVITY ANALYSES

We conducted sensitivity analyses that excluded patients with protocol violations or were restricted to women with complete postpartum follow-up data. In these analyses, the results were similar to those in the primary analyses (Tables S7 and S8 in the Supplementary Appendix).

DISCUSSION

In this large, multicenter, randomized trial, we found that the addition of azithromycin to standard antibiotic prophylaxis significantly reduced the frequency of infection after nonelective cesarean section. The risks of serious adverse maternal events and several other maternal outcomes, including readmissions, were lower in the azithromycin group than in the placebo group, and the risks of adverse neonatal outcomes were not increased in this group. The number of eligible women who would need to be treated to prevent one study outcome was 17 for the primary outcome, 43 for endometritis, and 24 for wound infections. In addition, the benefit of the intervention did not appear to vary significantly according to prespecified subgroup, including clinical site and timing of administration of the medication in relation to skin incision.

Our findings are consistent with those of previous studies supporting a lower risk of infection after cesarean section with the use of prophylactic extended-spectrum coverage than with standard antibiotic prophylaxis. In some reports, fewer infections were reported with the addition of metronidazole, which covers anaerobes, than with standard prophylaxis.24-28 We focused on azithromycin because it covers ureaplasma organisms, which are more commonly associated with infections after cesarean section than anaerobes when specific cultures are performed, and because it has been associated with reduced risks of both wound infections and endometritis.15,24-26 A single-center randomized trial involving 597 women and subsequent observational studies from the same center indicated that women who received azithromycin-based extended-spectrum antibiotic prophylaxis administered after umbilical-cord clamping had a rate of postoperative infection that was at least 30% lower than did women receiving standard prophylaxis; women in the azithromycin group also had a shorter hospital stay.24-26 Contrary to previous studies in which prophylactic extended-spectrum antibiotics were administered after skin incision and umbilical-cord clamping, we tested a preincision approach. The vast majority of patients received antibiotics before incision, with demonstrated maternal benefits and no evidence of neonatal harm.

A limitation of our study is the exclusion of women undergoing a scheduled cesarean section and those with intrapartum chorioamnionitis. These exclusions limit the generalizability of our findings in these two groups. Previous studies of azithromycin-based extended prophylaxis have suggested potential benefits for these two groups of women,22-24 but further investigation is warranted to assess efficacy and cost-effectiveness. Such factors are important, because women who have a scheduled cesarean delivery have a low risk of infection, and those with a diagnosis of chorioamnionitis are treated with broad-spectrum antibiotics after cesarean section. The mechanism by which azithromycin reduces the rate of infection after cesarean section remains unclear. Specific tests for the presence of ureaplasma or mycoplasma species are not routinely performed in practice and were not available for this study population. The available culture results suggest that the beneficial effect of azithromycin probably extends beyond coverage of ureaplasma organisms.

The selection of resistant organisms is a potential concern regarding azithromycin-based prophylaxis. However, it is unlikely that the single dose of antibiotic would significantly increase resistance. Our findings from clinical maternal cultures are reassuring, but ongoing monitoring for changes in resistance profiles is needed. We excluded women with a history of arrhythmia or cardiomyopathy, given a previous observational study reporting an association between multiple oral doses of azithromycin over a period of at least 5 days and the risk of cardiac death in a nonpregnant, older patient cohort with underlying coexisting conditions.29 Our data did not show any safety signal involving cardiac events or maternal death with the single intravenous dose of azithromycin; this is consistent with reassuring findings subsequently reported in a general population of young and middle-aged healthy adults.30

Standard antibiotic prophylaxis has been shown to reduce rates of surgical-site infection after cesarean section, along with rates of serious maternal complications and death.11 Our findings indicate that extended-spectrum prophylaxis with adjunctive azithromycin for cesarean delivery in women at increased risk for infection safely reduces the rates of infection and maternal use of health care resources without increasing the risk of neonatal adverse outcomes.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Supported by a grant (#HD64729) from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD). The azithromycin used in the study was provided by Pfizer through an investigator-initiated grant.

Dr. Clark reports receiving travel and grant support from AirStrip; Dr. Esplin, serving as a member of scientific advisory boards of Sera Prognostics and Clinical Innovations and having an equity interest in Sera Prognostics; and Dr. Cutter, receiving fees for serving on data and safety monitoring boards from Biogen Idec, Teva Neuroscience, Pfizer, Sanofi, Receptos, Gilead Sciences, Neuren Pharmaceuticals, Apotex/Modigenetech, Opko, Ono/Merck, GlaxoSmithKline, Horizon Pharma, Reata Pharma, and PTC Therapeutics, fees for serving on a steering committee from MedImmune, fees for serving on advisory boards from EMD Serono, Novartis, Questcor, Genentech, and Janssen, consulting fees from Teva Neuroscience, Genzyme, Genentech, Transparency Life Sciences, Roche, Opexa, Somahlution, Savara, and Nivalis, fees from a law firm for providing a legal opinion regarding a patent infringement case on behalf of Galderma, and grant support to his institution from Teva Neuroscience. No other potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

Disclosure forms provided by the authors are available with the full text of this article at NEJM.org.

We thank Rachel LeDuke, R.N., M.S.N., W.H.N.P., for assistance with protocol development and overall coordination between clinical research centers and the data coordinating center; John Hauth, M.D., for assistance with conception and oversight of the trial; Joseph Biggio, M.D., for oversight; Rebecca Quinn, Pharm.D., for coordinating investigational-drug pharmacy services at the University of Alabama at Birmingham; Yukiko N. Orange, B.S., Christopher Parks, B.S., and Richard Mailhot, M.B.A., M.S., for the development and maintenance of the trial database and data-entry system; Victoria Jauk, R.N., M.P.H., Robin Steele, M.P.H., Sue Cliver, B.Sc., and Ashutosh Tamhane, M.D., Ph.D., for data management and statistical analysis; Michael W. Varner, M.D., for oversight and outcome review; the members of the data and safety monitoring board — Janet Wittes, Ph.D., Mark Landon, M.D., Dwight J. Rouse, M.D., Robert Schelonka, M.D., and Sharon Copper, Ph.D. — for their services; Uma M. Reddy, M.D., and Caroline Signore, M.D., for their assistance as NICHD program officers; and the obstetrics and gynecology residents and fellows at the trial sites for their assistance with recruitment.

Footnotes

Presented in part at the 36th annual meeting of the Society for Maternal–Fetal Medicine, Atlanta, February 1–6, 2016.

References

- 1.Berg CJ, Chang J, Callaghan WM, Whitehead SJ. Pregnancy-related mortality in the United States, 1991-1997. Obstet Gynecol. 2003;101:289–96. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(02)02587-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mugford M, Kingston J, Chalmers I. Reducing the incidence of infection after caesarean section: implications of prophylaxis with antibiotics for hospital resources. BMJ. 1989;299:1003–6. doi: 10.1136/bmj.299.6706.1003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Perencevich EN, Sands KE, Cosgrove SE, Guadagnoli E, Meara E, Platt R. Health and economic impact of surgical site infections diagnosed after hospital discharge. Emerg Infect Dis. 2003;9:196–203. doi: 10.3201/eid0902.020232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.DeFrances CJ, Cullen KA, Kozak LJ. National Hospital Discharge Survey: 2005 annual summary with detailed diagnosis and procedure data. Vital Health Stat 13 2007. 165:1–209. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gibbs RS. Clinical risk factors for puerperal infection. Obstet Gynecol. 1980;555(Suppl):178S–184S. doi: 10.1097/00006250-198003001-00045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists ACOG practice bulletin no. 120: use of prophylactic antibiotics in labor and delivery. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;117:1472–83. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3182238c31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mangram AJ, Horan TC, Pearson ML, Silver LC, Jarvis WR. Guideline for prevention of surgical site infection, 1999: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Hospital Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee. Am J Infect Control. 1999;27:97–132. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.ASHP therapeutic guidelines on antimicrobial prophylaxis in surgery: American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 1999;56:1839–88. doi: 10.1093/ajhp/56.18.1839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services Physician Quality Reporting Initiative (PQRI) specifications document. 2008 https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/PQRS/downloads/2008PQRI MeasureSpecifications123107.pdf)

- 10.Shojania KG, Duncan BW, McDonald KM, Wachter RM, Markowitz AJ. Making health care safer: a critical analysis of patient safety practices. Evid Rep Technol Assess (Summ) 2001;43:1–668. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Smaill FM, Grivell RM. Antibiotic prophylaxis versus no prophylaxis for preventing infection after cesarean section. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;10:CD007482. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007482.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chelmow D, Ruehli MS, Huang E. Prophylactic use of antibiotics for nonla-boring patients undergoing cesarean delivery with intact membranes: a meta-analysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2001;184:656–61. doi: 10.1067/mob.2001.111303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thigpen BD, Hood WA, Chauhan S, et al. Timing of prophylactic antibiotic administration in the uninfected laboring gravida: a randomized clinical trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;192:1864–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2004.12.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Costantine MM, Rahman M, Ghulmiyah L, et al. Timing of perioperative antibiotics for cesarean delivery: a metaanalysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;199(3):301, e1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2008.06.077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tita AT, Rouse DJ, Blackwell S, Saade GR, Spong CY, Andrews WW. Emerging concepts in antibiotic prophylaxis for cesarean delivery: a systematic review. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;113:675–82. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e318197c3b6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rosene K, Eschenbach DA, Tompkins LS, Kenny GE, Watkins H. Polymicrobial early postpartum endometritis with facultative and anaerobic bacteria, genital mycoplasmas, and Chlamydia trachomatis: treatment with piperacillin or cefoxitin. J Infect Dis. 1986;153:1028–37. doi: 10.1093/infdis/153.6.1028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Watts DH, Krohn MA, Hillier SL, Eschenbach DA. Bacterial vaginosis as a risk factor for post-cesarean endometritis. Obstet Gynecol. 1990;75:52–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Roberts S, Maccato M, Faro S, Pinell P. The microbiology of post-cesarean wound morbidity. Obstet Gynecol. 1993;81:383–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Andrews WW, Shah SR, Goldenberg RL, Cliver SP, Hauth JC, Cassell GH. Association of post-cesarean delivery endometritis with colonization of the chorioamnion by Ureaplasma urealyticum. Obstet Gynecol. 1995;85:509–14. doi: 10.1016/0029-7844(94)00436-H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Keski-Nisula L, Kirkinen P, Katila ML, Ollikainen M, Suonio S, Saarikoski S. Amniotic fluid U. urealyticum colonization: significance for maternal peripartal infections at term. Am J Perinatol. 1997;14:151–6. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-994117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yoon BH, Romero R, Park JS, et al. Mi crobial invasion of the amniotic cavity with Ureaplasma urealyticum is associated with a robust host response in fetal, amniotic, and maternal compartments. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1998;179:1254–60. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(98)70142-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists ACOG practice bulletin no. 101: ultrasonography in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;113:451–61. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e31819930b0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.The National Healthcare Safety Network manual: patient safety component protocol. Centers for Diseases Control and Prevention; Atlanta: Jan, 2008. ( http://www.dhcs.ca.gov/provgovpart/initiatives/nqi/Documents/NHSNManPSPCurr.pdf) [Google Scholar]

- 24.Andrews WW, Hauth JC, Cliver SP, Savage K, Goldenberg RL. Randomized clinical trial of extended spectrum antibiotic prophylaxis with coverage for Urea-plasma urealyticum to reduce post-cesarean delivery endometritis. Obstet Gynecol. 2003;101:1183–9. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(03)00016-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tita AT, Hauth JC, Grimes A, Owen J, Stamm AM, Andrews WW. Decreasing incidence of postcesarean endometritis with extended-spectrum antibiotic prophylaxis. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;111:51–6. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000295868.43851.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tita AT, Owen J, Stamm AM, Grimes A, Hauth JC, Andrews WW. Impact of extended-spectrum antibiotic prophylaxis on incidence of postcesarean surgical wound infection. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;199(3):303, e1–3. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2008.06.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pitt C, Sanchez-Ramos L, Kaunitz AM. Adjunctive intravaginal metronidazole for the prevention of postcesarean endometritis: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2001;98:745–50. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(01)01517-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Meyer NL, Hosier KV, Scott K, Lipscomb GH. Cefazolin versus cefazolin plus metronidazole for antibiotic prophylaxis at cesarean section. South Med J. 2003;96:992–5. doi: 10.1097/01.SMJ.0000060570.51934.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ray WA, Murray KT, Hall K, Arbogast PG, Stein CM. Azithromycin and the risk of cardiovascular death. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:1881–90. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1003833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Svanström H, Pasternak B, Hviid A. Use of azithromycin and death from cardiovascular causes. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:1704–12. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1300799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.