Abstract

BACKGROUND

Because preoperative risk factor modification is generally not possible in the emergency setting, complication prevention represents an important focus for quality improvement in emergency general surgery (EGS). The objective of our study was to determine the overall impact that specific postoperative complications have in this patient population.

STUDY DESIGN

Our study sample consisted of patients from the 2012–2013 ACS-NSQIP database who underwent an EGS procedure. We used population attributable fractions (PAFs) to estimate the overall impact that each of 8 specific complications had on 30-day physiologic and resource use outcomes in our study population. The PAF represents the percentage reduction in a given outcome that would be anticipated if a complication were able to be completely prevented in our study population. Both unadjusted and risk-adjusted PAFs were calculated.

RESULTS

There were 79,183 patients included for analysis. The most common complications in these patients were bleeding (6.2%), incisional surgical site infection (SSI) (3.4%), pneumonia (2.7%), and organ/space SSI (2.6%). Bleeding was the complication with the greatest overall impact on mortality and end-organ dysfunction, demonstrating an adjusted PAF of 10.7% (95% CI 8.2%,13.1%, p < 0.001) and 15.9% (95% CI 13.9%, 16.7%, p < 0.001) for these respective outcomes. The only other complication with a sizeable impact on these outcomes was pneumonia (adjusted PAF of 7.9% for mortality and 13.2% for pneumonia). In contrast, complications such as urinary tract infection, venous thromboembolism, myocardial infarction, and incisional SSI had negligible impacts on these outcomes.

CONCLUSIONS

Our study provides a framework for the development of high-value quality initiatives in EGS.

Over the past decade, an increasing number of patients with emergency general surgical (EGS) disease are receiving their care under the auspices of acute care surgical services.1–5 As the clinical management and in-hospital administration of EGS patients continues to become more centralized, it will become increasingly practical to develop and implement quality initiatives that are specifically designed to improve the outcomes of these patients. Perhaps in recognition of this evolving opportunity, the American Association for the Surgery of Trauma (AAST) and the American College of Surgeons (ACS) have created a task force of academic leaders in acute care surgery in order to develop a strategic agenda for future EGS research efforts.6 Among the health policy research needs identified by this task force as meriting prioritization were the creation of metrics for measuring the quality of EGS care received, and development of public health strategies to mitigate the burden imposed by EGS.

For several reasons, postoperative complications represent an obvious initial focus for EGS-specific quality improvement efforts. First, complications occur relatively frequently in EGS patients, especially when compared with patients who undergo elective surgical procedures.7–10 Therefore, any successful effort to curb the incidence of adverse postoperative events in EGS patients would be expected to have a disproportionate impact on the overall incidence of surgical morbidity in the United States. Second, the occurrence of postoperative complications is strongly associated with the risk of subsequent death and with the generation of considerable costs of care and excess health care resource use.11–15 A reduction in the frequency of complications in the EGS population would therefore be anticipated to result in significant savings, both in terms of patient lives and health care expenditures. Finally, the time-sensitive nature of EGS disease will generally preclude reliance on traditional approaches to surgical quality improvement, such as preoperative risk factor modification. Perhaps by default, any attempt to improve the outcomes of patients who require emergency operation will instead need to involve either a reduction in the incidence of postoperative complications or an improvement in the timeliness and effectiveness with which such complications are recognized and managed.9,14

In order to maximize the benefit of EGS quality initiatives, it will first be necessary to understand which complications have the greatest overall impact on EGS patients. Previous studies of morbidity after EGS typically describe complications in terms of their incidence or their strength of association with downstream outcomes such as mortality, hospital cost, or hospital readmission.7–16 However, simple knowledge of the prevalence of a complication or its severity is not sufficient for being able to determine that complication’s overall impact on a given patient population. For example, a relatively common complication will have only a negligible population-level impact if it is unlikely to result in pathophysiologic compromise or extensive resource use. Similarly, complications that are particularly severe or costly will have a small population-level impact if they occur rarely. The objective of this study was to use an epidemiologic measure termed population attributable fraction in order to quantify the overall impact that specific complications have on patient and financial outcomes after EGS.

METHODS

The 2012–2013 American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program (ACS-NSQIP) Participant Use Data Files (PUFs) were used for our study.17 Patients were included for analysis if they underwent emergency surgery by a general surgeon for a clinical condition that has been identified by the AAST as constituting the scope of EGS practice.18 Missing information was handled in 1 of 2 ways. For variables in which a very small percentage of observations were lacking information (American Society of Anesthesiologists [ASA] Physical Status classification, operative time, length of postoperative hospitalization), patients with missing data were simply excluded from the analysis. For variables in which a larger percentage of observations were lacking information (BMI, preoperative functional status, and preoperative serum albumin), a missing indicator category was created.19

The primary outcomes variables for our analysis included 30-day incidence of end-organ dysfunction (EOD), 30-day mortality, hospital readmission within 30 days after index operation, and length of postoperative hospitalization. End-organ dysfunction is a composite outcome variable, and was noted to have occurred if a patient developed 1 or more of the following conditions in the first 30 days after the index procedure: need for postoperative mechanical ventilation > 48 hours, coma, septic shock, or postoperative renal insufficiency (with or without the need for hemodialysis).16 Bleeding is defined by ACS-NSQIP as the need for 1 or more units of packed red blood cells within 72 hours of the start of the index operation.

The primary predictor variables for our analysis were the presence or absence of the following index complications in the first 30 days after the index EGS operation: incisional surgical site infection (SSI, including superficial and/or deep incisional infections), bleeding, pneumonia, organ/space SSI, urinary tract infection (UTI), venous thromboembolism (VTE, including deep venous thrombosis and/or pulmonary embolism), myocardial infarction (MI), and stroke. Bleeding is defined by ACS-NSQIP as the need for 1 or more units of packed red blood cells within 72 hours of the start of the index operation. Additional predictor variables that were considered included a comprehensive set of patient- and procedure-related characteristics (Tables 1 and 2).

Table 1.

Patient-Related Characteristics of 19,524 Elderly Patients Undergoing Emergency General Surgery

| Characteristic | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Demographic | ||

| Female | 40,568 | 51.2 |

| Age, y | ||

| <50 | 41,143 | 52.0 |

| 50–69 | 23,564 | 29.8 |

| ≥70 | 14,476 | 18.3 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | ||

| <20 | 4,503 | 5.7 |

| 20–24 | 19,856 | 25.1 |

| 25–29 | 22,731 | 28.7 |

| ≥30 | 24,664 | 31.2 |

| Unknown | 7,429 | 9.4 |

| Chronic comorbid condition | ||

| Diabetes mellitus | 8,277 | 10.5 |

| Active smoker | 16,184 | 20.4 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 3,301 | 4.2 |

| Congestive heart failure | 857 | 1.1 |

| Hypertension | 24,541 | 31.0 |

| End-stage renal disease | 952 | 1.2 |

| Disseminated cancer | 1,299 | 1.6 |

| Chronic steroid usage | 2,720 | 3.4 |

| Bleeding disorder | 4,424 | 5.6 |

| Acute comorbid condition | ||

| Preoperative mechanical ventilation | 1,340 | 1.7 |

| Preoperative acute renal failure | 856 | 1.1 |

| Preoperative infected wound | 2,010 | 2.5 |

| Preoperative transfusion | 1,840 | 2.3 |

| Preoperative sepsis classification | ||

| None | 52,840 | 66.7 |

| SIRS | 13,840 | 17.5 |

| Sepsis | 10,234 | 12.9 |

| Septic shock | 2,269 | 2.9 |

| Frailty or nutrition | ||

| Preoperative functional status | ||

| Independent | 75,785 | 95.7 |

| Partially or totally dependent | 2,713 | 3.4 |

| Unknown | 685 | 0.9 |

| Preoperative serum albumin | ||

| Normal (≥3.5 mg/dL) | 43,633 | 55.1 |

| Low (<3.5 mg/dL) | 14,496 | 18.3 |

| Unknown | 21,054 | 26.6 |

| >10% Weight loss in prior 6 months | 1,045 | 1.3 |

SIRS, systemic inflammatory response syndrome.

Table 2.

Procedure-Related Characteristics of Elderly Patients Undergoing Emergency General Surgery

| Characteristic | Data |

|---|---|

| Preoperative | |

| ASA Physical Status Classification | |

| ASA Class 1 | 16,966 (21.4) |

| ASA Class 2 | 34,005 (42.9) |

| ASA Class 3 | 20,141 (25.4) |

| ASA Class 4 | 7,395 (9.3) |

| ASA Class 5 | 676 (0.9) |

| Primary diagnosis classification | |

| Upper gastrointestinal tract | 43,296 (54.7) |

| Hepato-pancreatico-biliary | 8,371 (10.6) |

| Intestinal obstruction | 7,400 (9.4) |

| Hernia | 7,910 (10.0) |

| Colorectal | 6,567 (8.3) |

| Vascular | 1,871 (2.4) |

| Soft tissue | 1,836 (2.3) |

| General abdominal | 1,751 (2.2) |

| Cardiothoracic | 107 (0.1) |

| Resuscitation or other | 74 (0.1) |

| Intraoperative | |

| Total work relative value units, median (IQR), units |

10.0 (9.5, 21.5) |

| Operative time, median (IQR), min | 55 (36, 87) |

| Incisional wound classification | |

| Clean or clean-contaminated | 30,573 (38.6) |

| Contaminated | 28,220 (35.6) |

| Dirty or infected | 20,390 (25.8) |

Data are expressed as n (%) of overall study sample unless otherwise indicated.

ASA, American Society of Anesthesiologists; IQR, interquartile range.

The frequency of binary outcomes and the median lengths of postoperative hospitalization were compared for patients who sustained each type of index complication. Multivariable logistic regression models were used to identify the independent association between each of the index complications and 30-day binary outcomes. The previously identified patient- and procedure-related characteristics, operative EGS diagnosis, and each of the index postoperative complications were included as predictor variables in these regression models. Multivariable linear regression was used to assess the association between index complications and postoperative length of hospitalization. For this model, the logarithmic transformation of postoperative length of hospitalization was used as the dependent variable. Adjusted odds ratios (AOR) and 95% CIs were reported for the logistic regression models, and adjusted beta coefficients and 95% CIs were reported for the linear regression model. The regression models that were used to identify associations with hospital readmission included only those patients who were still alive 30 days after their EGS procedure.

In order to assess the impact of each of the index complications on the outcomes of our study, we calculated the unadjusted population attributable fraction (PAF) for each complication-outcome pair. In this context, PAF represents the reduction in the rate of a given outcome that could be achieved if exposure to a specific complication were completely eliminated. The PAF was calculated using the following equation:

where Pc represents the prevalence of a specific complication within our study population and RR represents the risk ratio of an adverse outcome (ie, the risk of the outcome in patients who sustained the complication divided by the risk of the outcome in patients who did not sustain the complication).20

In order to determine the impact of each index complication on postoperative length of hospitalization, we developed a modification of the above formula in order to determine the proportion of our study population’s overall quantity of postoperative hospital days that were attributable to a given complication:

where (DD−CD)c represents the number of postoperative, post-complication hospital days for patients who experienced a given complication, and DDp represents the total number of postoperative hospital days for all patients in our study population. For this equation, patients whose index complication occurred after initial hospital discharge were considered to have a (DD−CD) value of zero.

In order to estimate the PAFs for each complication-binary outcome pair after adjustment for known patient- and procedure-related factors we used the punaf command in Stata Version 14.0 (STATA Corp) after performing each of the previously described multivariable logistic regression analyses.21 This approach allows for an assessment of the proportional reduction in adverse outcomes that would occur if a given surgical complication could be avoided, holding constant patient- and procedure-related characteristics. Because length of postoperative hospitalization was treated as a continuous variable in our study, we did not estimate adjusted attributable fractions for this outcome and present only unadjusted PAFs.

RESULTS

There were 79,410 patients from the 2012–2013 ACS-NSQIP Participant User Files who underwent emergency operation for an EGS diagnosis and were available for analysis. Of these patients, 227 (0.3%) were excluded due to missing information, yielding a study population of 79,183 patients. Patient- and procedure-related characteristics of study patients are demonstrated in Table 1 and 2.

The overall incidence of index complications in our study population was 14.4% (11,387 of 79,183 patients), with 8,887 (11.2%) patients sustaining only 1 index complication and 2,600 (3.2%) developing more than 1 index complication. The most common index complications (in order of decreasing frequency) were bleeding (6.2%), incisional SSI (3.4%), pneumonia (2.7%), organ/space SSI (2.6%), UTI (1.5%), VTE (1.1%), MI (0.5%), and stroke (0.2%).

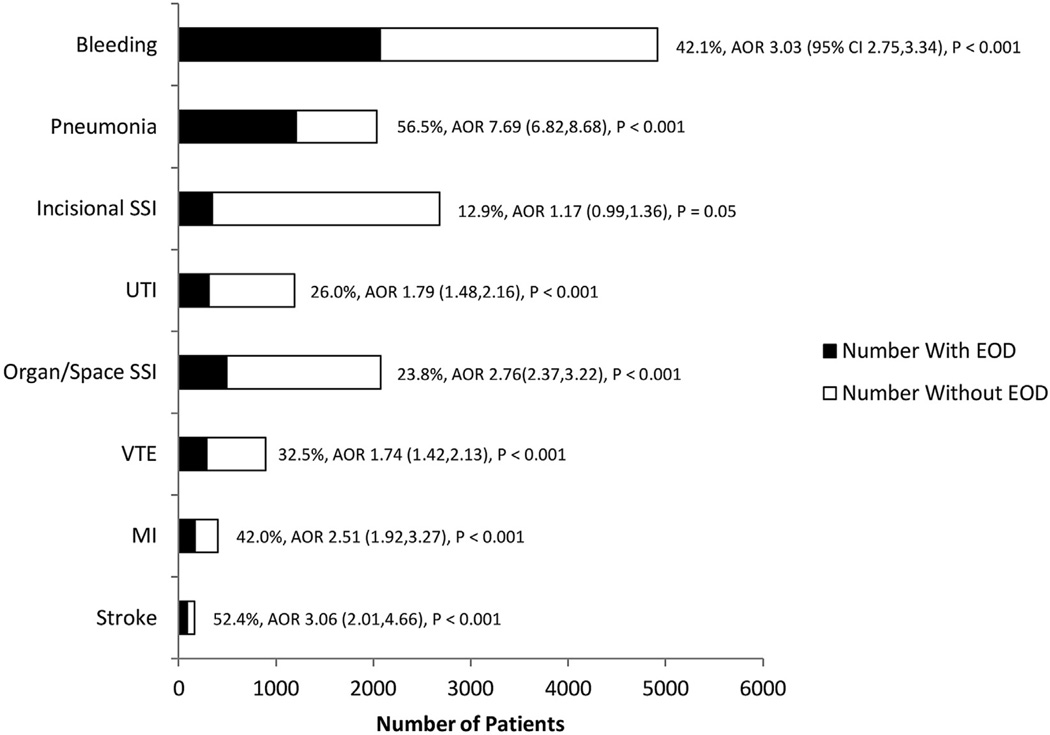

The 30-day incidence of EOD in our study population was 5.9% (4,646 patients). Figure 1 demonstrates the incidence of EOD stratified by type of index complication and the AOR of developing EOD in patients who sustained a given index complication. The incidence of EOD was highest in patients who developed postoperative pneumonia (56.5%) or stroke (52.4%), and lowest in patients who developed postoperative incisional SSI (12.9%). All of the index complications that we analyzed were associated with a significant risk of EOD, although the magnitude of this association appeared to be greatest for pneumonia (AOR of EOD = 7.69 [95% CI 6.82, 8.68], p < 0.001).

Figure 1.

Independent association between index complications and incidence of postoperative end-organ dysfunction in emergency general surgery patients. AORs adjusted for known patient- and procedure-related factors and for presence of other index complications. AOR, adjusted odds ratio; EOD, end-organ dysfunction; SSI, surgical site infection; UTI, urinary tract infection; VTE, venous thromboembolism.

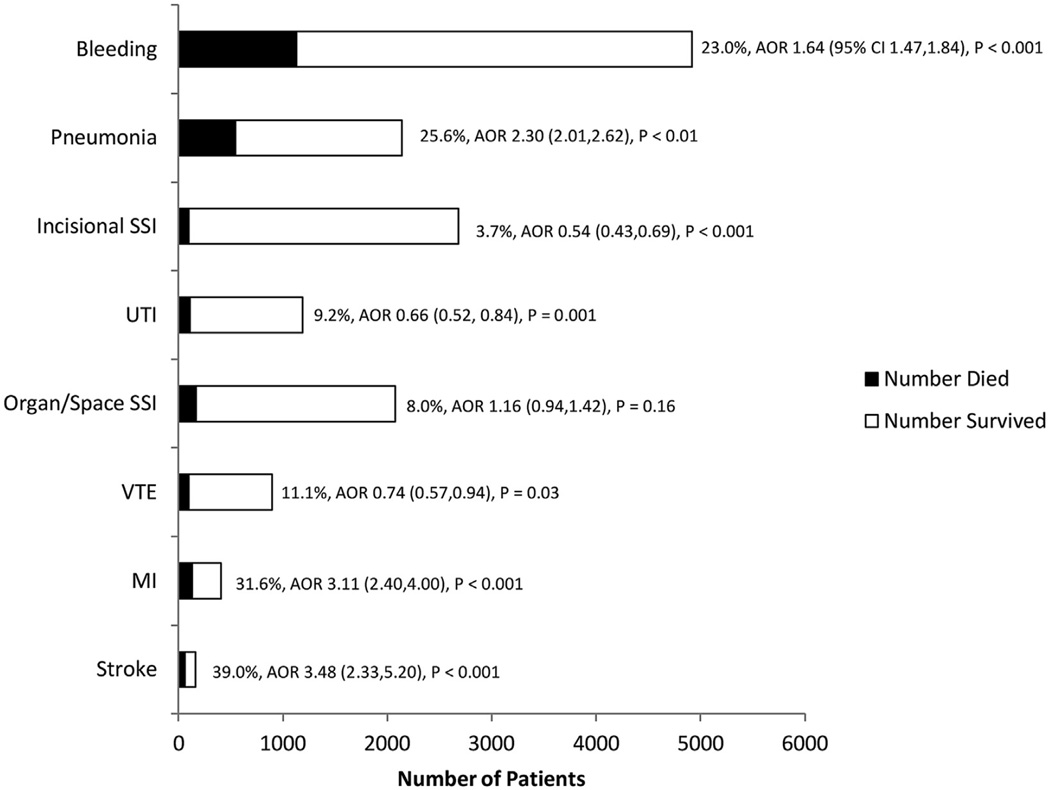

The overall 30-day mortality rate for patients in our analysis was 3.3% (2,603 patients). Figure 2 demonstrates 30-day mortality rates stratified by index complication type. The incidence of death was highest in patients who sustained stroke, MI, pneumonia, and bleeding, and each of these complications was independently associated with an increased risk of subsequent death. Conversely, complications such as incisional SSI, UTI, organ/space SSI, and VTE did not appear to significantly increase the risk of death. In particular, the AOR of death in patients who sustained incisional SSI, UTI, and VTE was less than 1.0. This finding is likely explained by the fact that a large percentage of patients in our study who died did so early after their index operation. Because these patients did not live long enough to sustain complications such as incisional SSI or UTI, these complications therefore appear to have a “protective effect” against death. This statistical anomaly has been described previously, and is largely a result of our failing to censor patients who experience early death after their EGS operation.22

Figure 2.

Independent association between index complications and incidence of mortality in emergency general surgery patients. AORs adjusted for known patient- and procedure-related factors and for presence of other index complications. AOR, adjusted odds ratio; SSI, surgical site infection; UTI, urinary tract infection; VTE, venous thromboembolism.

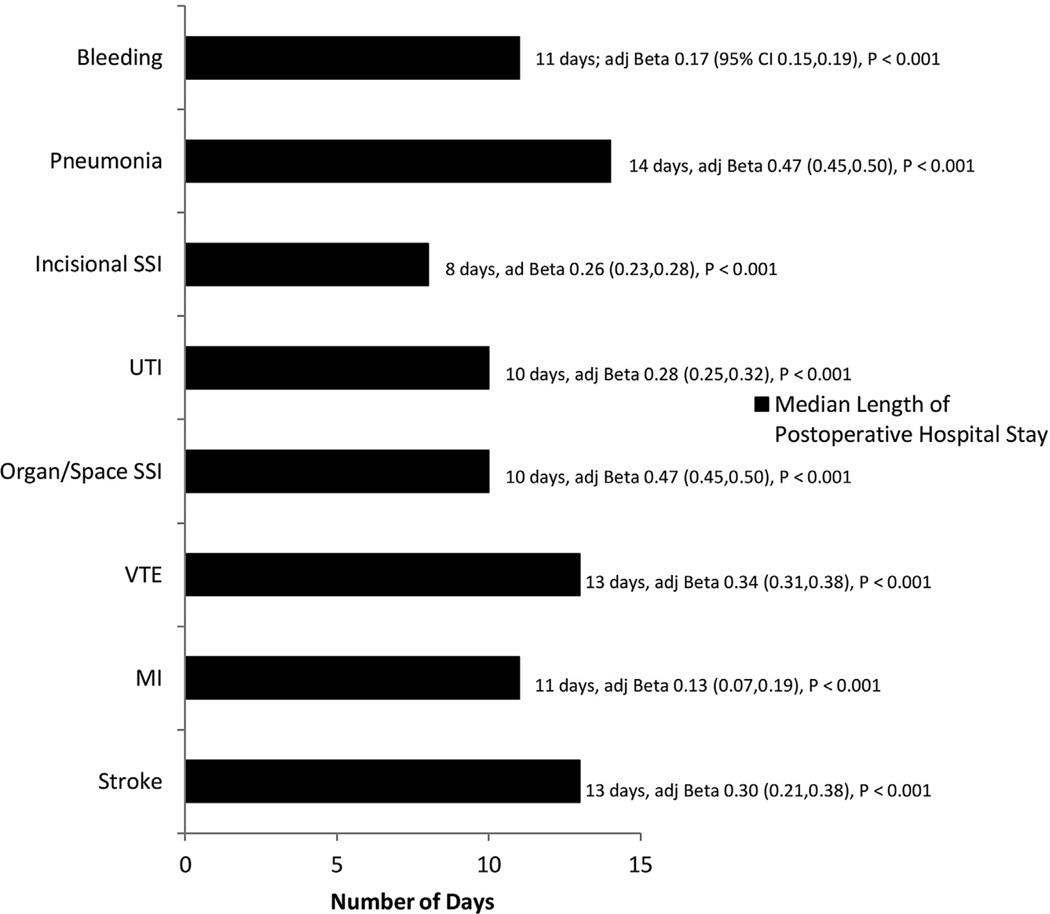

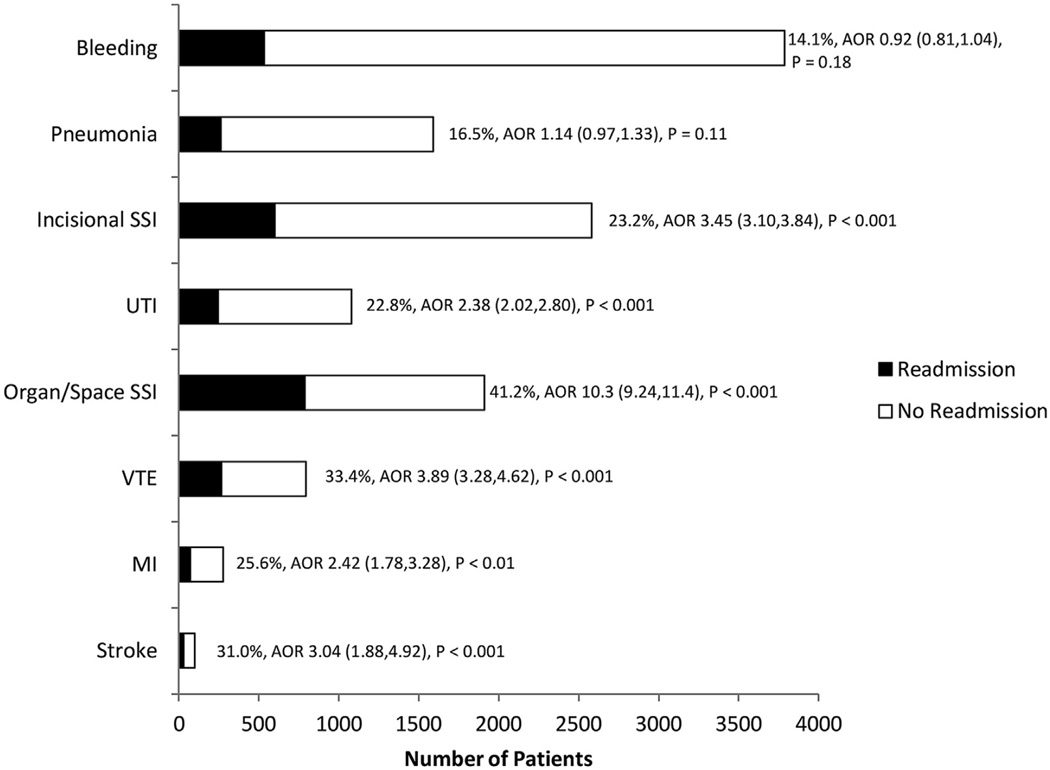

The median length of postoperative hospitalization for patients in our study was 2 days (interquartile range 1 to 5 days). All of the index complications that we analyzed resulted in a significant increase in length of stay (Fig. 3), although this increase was greatest in patients who sustained pneumonia (median postoperative length of stay, 14 days) and stroke (median postoperative length of stay, 13 days). The overall 30-day hospital readmission rate among survivors of EGS was 6.4% (5,067 patients). The incidence of readmission was highest after organ/space SSI (41.2%, Fig. 4), and the likelihood of readmission was greatest after organ/space SSI (AOR of readmission = 10.3), VTE (AOR 3.89), and incisional SSI (3.45). Patients who developed pneumonia or bleeding and who survived the initial 30 days after their index procedure did not have a significant increase in the risk of readmission.

Figure 3.

Independent association between index complications and length of postoperative hospitalization in emergency general surgery patients. Beta coefficient adjusted for known patient- and procedure-related factors and for presence of other index complications; logarithmic transformation of postoperative length of hospital stay used as dependent variable in linear regression model. adj Beta, adjusted Beta coefficient; SSI, surgical site infection; UTI, urinary tract infection; VTE, venous thromboembolism.

Figure 4.

Independent association between index complications and incidence of hospital readmission in emergency general surgery patients. AORs adjusted for known patient- and procedure-related factors and for presence of other index complications. AOR, adjusted odds ratio; SSI, surgical site infection; UTI, urinary tract infection; VTE, venous thromboembolism.

Table 3 demonstrates the unadjusted PAF for each complication-outcome combination, and shows that if bleeding were completely eliminated as a complication in our study population, there would be a 40.9% reduction in the incidence of EOD, a 39.7% reduction in mortality, and a 19.2% reduction in postoperative hospital days. The unadjusted impact of pneumonia was also relatively large for these 3 outcomes as well. The complications that exhibited the largest unadjusted impact on hospital readmission, meanwhile, were organ/space SSI and incisional SSI. Elimination of these complications would result in a 13.9% and 9.2% reduction in the need for readmission in our study population, respectively.

Table 3.

Unadjusted Population Attributable Fractions and Excess Length of Postoperative Hospitalization for Specific Index Complications

| End-organ dysfunction, % | Mortality, % | Total number of postoperative hospital days, % | Hospital readmission, % |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Bleeding (40.9) | 1. Bleeding (39.7) | 1. Bleeding (19.2) | 1. Organ/Space SSI (13.9) |

| 2. Pneumonia (23.9) | 2. Pneumonia (18.8) | 2. Pneumonia (7.9) | 2. Incisional SSI (9.2) |

| 3. Organ/Space SSI (8.2) | 3. MI (4.4) | 3. Organ/Space SSI (5.0) | 3. Bleeding (6.2) |

| 4. VTE (5.2) | 4. Organ/Space SSI (3.9) | 4. Incisional SSI (3.4) | 4. VTE (4.4) |

| 5. UTI (5.2) | 5. VTE (2.7) | 5. UTI (2.5) | 5. UTI (3.7) |

| 6. Incisional SSI (4.2) | 6. UTI (2.7) | 6. VTE (2.3) | 6. Pneumonia (3.3) |

| 7. MI (3.2) | 7. Stroke (2.3) | 7. MI (1.1) | 7. MI (1.1) |

| 8. Stroke (1.6) | 8. Incisional SSI (0.5) | 8. Stroke (0.5) | 8. Stroke (0.5) |

Data are expressed as percentage reduction in incidence of adverse outcome or number of postoperative hospital days that would occur if exposure to complication were completely eliminated.

MI, myocardial infarction; SSI, surgical site infection; UTI, urinary tract infection; VTE, venous thromboembolism.

Table 4 demonstrates the PAF for each complication-binary outcome combination after adjustment for patient- and procedure-related factors. As with our unadjusted analysis, bleeding was the complication with the largest overall impact on EOD and mortality. Elimination of bleeding in our study population would result in an estimated 15.9% (95% CI 13.9, 16.7; p < 0.001) reduction in the incidence of EOD and a 10.7% (95% CI 8.2, 13.1; p < 0.001) reduction in the incidence of mortality. Not surprisingly, the overall impact of this and other complications on outcomes was found to be lower after controlling for other factors. Although the overall impact of organ/space SSI and incisional SSI on the incidence of EOD and mortality was relatively small, they had the largest impact of the complications that we examined on the incidence of hospital readmission (PAF 12.9% for organ/space SSI and 7.3% for incisional SSI). By comparison, complications such as UTI, VTE, and MI did not appear to have a large impact on any of the outcomes that we assessed.

Table 4.

Risk-Adjusted Population Attributable Fractions for Specific Index Complications

| End-organ dysfunction | Mortality | Hospital readmission |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Bleeding, 15.9 (13.9,16.7) p < 0.001 |

1. Bleeding, 10.7 (8.2,13.1) p < 0.001 |

1. Organ/space SSI, 12.9 (12.1,13.7) p < 0.001 |

| 2. Pneumonia, 13.2 (12.3,14.0) p < 0.001 |

2. Pneumonia, 7.9 (6.5,9.2) p < 0.001 |

2. Incisional SSI, 7.3 (6.5,8.1) p < 0.001 |

| 3. Organ/Space SSI, 3.6 (3.0, 4.2) p < 0.001 |

3. MI, 2.3 (1.7,2.9) p < 0.001 |

3. VTE, 3.1 (2.6,3.6) p < 0.001 |

| 4. UTI, 1.3 (0.9,1.8) p < 0.001 |

4. Stroke 1.0 (0.7,1.4) p < 0.001 |

4. UTI, 2.2 (1.7, 2.8) p < 0.001 |

| 5. VTE, 1.1 (0.7,1.6) p < 0.001 |

5. Organ/space SSI, 0.6 (−0.2,1.4) p = 0.17 |

5. MI, 0.6 (0.4,0.9) p = 0.17 |

| 6. MI, 1.1 (0.7, 1.4) p < 0 .001 |

6. VTE, 0.8 (−1.5,−0.2) p = 0.01 |

6. Stroke, 0.3 (0.1,0.5) p < 0 .001 |

| 7. Stroke, 0.5 (0.3, 0.7) p < 0.001 |

7. UTI, 1.3 (−2.0,−0.6) p < 0.001 |

7. Pneumonia, 0.5 (−0.1,1.0) p = 0.12 |

| 8. Incisional SSI, 0.6 (0.0,1.2) p = 0.06 |

8. Incisional SSI, 2.1 (−2.8,−1.4) p = 0.06 |

8. Bleeding, 0.7 (−1.6,0.3) p = 0.17 |

Data are expressed as estimated percentage reduction (95% CI) in incidence of adverse outcome or number of postoperative hospital days that would occur if exposure to complication were completely eliminated.

MI, myocardial infarction; SSI, surgical site infection; UTI, urinary tract infection; VTE, venous thromboembolism.

As is shown in Table 4, the adjusted PAF for several complications appeared to suggest that they reduced the incidence of mortality. As described previously, this anomalous finding is likely due to the relatively high incidence of mortality in our study population and to the fact that the complications that demonstrated a “negative” adjusted PAF tend to occur later in a patient’s postoperative course.

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this study is the first to use PAF as a parameter for describing the overall impact that postoperative complications have on the outcomes of surgical patients. The PAF has traditionally been used in the epidemiologic literature in order to assess priorities for public health action, such as determining and comparing the potential influence of identified risk factors on the prevalence of a given disease or condition.23,24 Extending the use of PAF to an assessment of the impact of surgical morbidity offers a distinct advantage to policymakers who must determine which complications merit the greatest attention as targets of quality improvement initiatives. Previously published studies have demonstrated the prevalence and the severity of specific complications after EGS.7,9,10,14–16 By providing estimated PAFs for these complications, our analysis combines information about both prevalence and severity into a single parameter that describes each complication’s overall impact on the EGS patient population. As a result, future EGS-specific quality improvement initiatives can be targeted toward high-impact complications, maximizing the value of the resources and effort that underlie those initiatives.

Based on the findings of our analysis, we estimate that bleeding and pneumonia are the complications that exert the greatest overall impact on patient outcomes after EGS. Elimination of these complications in our study population would be anticipated to result in a 15.9% and 13.2% reduction, respectively, in the incidence of EOD, and a 10.7% and 7.9% reduction in the incidence of mortality. By comparison, complications that are targeted by existing initiatives, such as the Surgical Care Improvement Program (SCIP), would be anticipated to have very little impact on the EGS population. The Surgical Care Improvement Program currently targets process measures that are believed to be important for the prevention of SSI, VTE, MI, and UTI.25 Although some of these complications (such as incisional SSI) were relatively common in our study sample, and others (such as MI and organ/space SSI) were relatively severe in terms of their association with EOD and mortality, the overall impact of each of the SCIP-targeted complications on patient outcomes after EGS was small when compared to the burden imposed by bleeding and pneumonia. Our results therefore suggest that simply extending quality improvement initiatives that were originally designed for elective procedures to EGS will have minimal impact on patient outcomes.

The results of our study also suggest that the impact of a given complication will depend on the outcome being considered. As previously demonstrated, organ/space and incisional SSI complications had little if any impact on the incidence of EOD and death in our study, but were the highest-impact complications in terms of their contribution to hospital readmission. Hospital readmission is increasingly being used by third party payers as a marker of health care resource use and overall quality, and there is growing interest in identifying factors that contribute to the need for readmission.15 As our study demonstrates, however, the factors that have the greatest impact on hospital readmission may not be the same factors that pose the largest burden on early postoperative patient outcomes. As a result, initiatives designed to reduce post-EGS mortality may not substantially affect post-EGS readmission, and vice versa. Presuming that the resource pool available for quality improvement is finite, it may ultimately be necessary for health care policymakers to determine which outcomes merit the greatest share of this effort.

Our study has several important limitations. First, our analysis is confined to patients undergoing EGS procedures within hospitals that participate in ACS-NSQIP. Because our data source is not population-based, our findings are not necessarily generalizable to all EGS patients and to all United States hospitals. Second, we have developed EOD as a composite variable used to represent an adverse but sub-lethal patient outcome, though this variable has not been previously validated.16 Third, our use of PAF as a descriptive parameter assumes a hypothetical scenario in which exposure to a given complication is completely avoided after EGS procedures. In reality, each of the complications we have examined in this analysis is likely to vary in the degree to which they can be prevented. Fourth, we have framed the rationale for our study in the context of future quality improvement efforts in EGS. Prevention of or rescue from complications represent only 1 of the many possible foci of such efforts. Finally, our use of logistic regression as a basis for our estimates of the PAF of specific complications on 30-day mortality after EGS has resulted in the appearance of some complications having a “protective” effect on the risk of death. This statistical anomaly could have been avoided by either censoring early postoperative deaths from our analysis, or by alternatively performing survival analysis. Because the a priori purpose of our study was to identify complications with the largest overall impact on mortality, we have chosen to present the findings as they are because the statistical significance or positive/negative direction of lower-impact complications has not altered our conclusions.

CONCLUSIONS

In conclusion, our study demonstrates the impact that specific outcomes have on patient and financial outcomes after EGS. The results of our analysis provide a framework for the development of high-value initiatives that are designed to reduce the burden that postoperative complications have on patients who require EGS procedures. Our findings suggest that any initiative that can successfully reduce the incidence of postoperative bleeding or pneumonia in EGS patients will offer the greatest possible value in terms of minimizing the burden that postoperative complications pose on the physiologic outcomes of this patient population.

Abbreviations and Acronyms

- AOR

adjusted odds ratio

- EGS

emergency general surgery

- EOD

end-organ dysfunction

- MI

myocardial infarction

- PAF

population attributable fraction

- SSI

surgical site infection

- UTI

urinary tract infection

- VTE

venous thromboembolism

Footnotes

Disclosure Information: Authors have nothing to disclose. Timothy J Eberlein, Editor-in-Chief, has nothing to disclose.

Presented at the Southern Surgical Association 127th Annual Meeting, Hot Springs, VA, December 2015.

Author Contributions

Study conception and design: Scarborough, Schumacher, Pappas, McCoy, Englum, Agarwal, Greenberg

Acquisition of data: Scarborough

Analysis and interpretation of data: Scarborough, Schumacher, Pappas, McCoy, Englum, Agarwal, Greenberg

Drafting of manuscript: Scarborough

Critical revision: Schumacher, Pappas, McCoy, Englum, Agarwal, Greenberg

REFERENCES

- 1.Hoyt DB, Kim HD, Barrios C. Acute care surgery: a new training and practice model in the United States. World J Surg. 2008;32:1630–1635. doi: 10.1007/s00268-008-9576-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Britt RC, Weireter LJ, Britt LD. Initial implementation of an acute care surgery model: implications for timeliness of care. J Am Coll Surg. 2009;209:421–424. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2009.06.368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gale SC, Shafi S, Dombrovskiy VY, et al. The public health burden of emergency general surgery in the United States: A 10-year analysis of the Nationwide Inpatient Sample - 2001 to 2010. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2014;77:202–208. doi: 10.1097/TA.0000000000000362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Santry HP, Madore JC, Collins CE, et al. Variations in the implementation of acute care surgery: Results from a national survey of university-affiliated hospitals. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2015;78:60–68. doi: 10.1097/TA.0000000000000492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Khalil M, Pandit V, Rhee P, et al. Certified acute care surgery programs improve outcomes in patients undergoing emergency surgery: A nationwide analysis. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2015;79:60–64. doi: 10.1097/TA.0000000000000687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Morris JA, Jr, Fildes J, May AK, et al. A research agenda for emergency general surgery: health policy and basic science. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2013;74:322–328. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e31827d0fe3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ingraham AM, Cohen ME, Bilimoria KY, et al. Comparison of 30-day outcomes after emergency general surgery procedures: potential for targeted improvement. Surgery. 2010;148:217–238. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2010.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ingraham AM, Cohen ME, Raval MV, et al. Comparison of hospital performance in emergency versus elective general surgery operations at 198 hospitals. J Am Coll Surg. 2011;212:20–28. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2010.09.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Smith MA, Hussain A, Xiao J, et al. The importance of improving the quality of emergency surgery for a regional quality collaborative. Ann Surg. 2013;257:596–602. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3182863750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Havens JM, Peetz AB, Do WS, et al. The excess morbidity and mortality of emergency general surgery. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2015;78:306–311. doi: 10.1097/TA.0000000000000517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dimick JB, Pronovost PJ, Cowan JA, Lipsett PA. Complications and costs after high-risk surgery: Where should we focus quality improvement initatives? J Am Coll Surg. 2003;196:671–678. doi: 10.1016/S1072-7515(03)00122-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Silber JH, Rosenbaum PR, Trudeau ME, et al. Changes in prognosis after the first postoperative complication. Med Care. 2005;43:122–132. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200502000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lawson EH, Hall BL, Louie R, et al. Association between occurrence of a postoperative complication and readmission: implications for quality improvement and cost savings. Ann Surg. 2013;258:10–18. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31828e3ac3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sheetz KH, Krell RW, Englesbee MJ, et al. The importance of the first complication: Understanding failure to rescue after emergent surgery in the elderly. J Am Coll Surg. 2014;219:365–370. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2014.02.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Havens JM, Olufajo OA, Cooper ZR, et al. Defining rates and risk factors for readmissions following emergency general surgery. JAMA Surg. 2015;11:1–7. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2015.4056. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McCoy CC, Englum BR, Keenan JE, et al. Impact of specific postoperative complications on the outcomes of emergency general surgery patients. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2015;78:912–919. doi: 10.1097/TA.0000000000000611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shiloach M, Frencher SK, Jr, Steeger JE, et al. Toward robust information: data quality and inter-rater reliability in the American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program. J Am Coll Surg. 2010;210:6–16. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2009.09.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shafi S, Aboutanos MB, Agarwal SA, Jr, et al. Emergency general surgery: definition and estimated burden of disease. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2013;74:1092–1097. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e31827e1bc7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hamilton BH, Ko CY, Richards K, Hall BL. Missing data in the American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program are not missing at random: implications and potential impact on quality assessment. J Am Coll Surg. 2010;210:125–139. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2009.10.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Poole C. A history of the population attributable fraction and related measures. Ann Epidemiol. 2015;25:147–154. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2014.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Newson RB. Attributable and unattributable risks and fractions and other scenario comparisons. The Stata Journal. 2013;13:672–698. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Khuri SF, Henderson WG, DePalma RG, et al. Determinants of long-term survival after major surgery and the adverse effect of postoperative complications. Ann Surg. 2005;242:326–341. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000179621.33268.83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Northridge ME. Annotation: Public health methods - attributable risk as a link between causality and public health action. Am J Public Health. 1995;85:1202–1204. doi: 10.2105/ajph.85.9.1202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rockhill B, Newman B, Weinberg C. Use and misuse of population attributable fractions. Am J Public Health. 1998;88:15–19. doi: 10.2105/ajph.88.1.15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Weston A, Caldera K, Doron S. Surgical care improvement project in the value-based purchasing era: more harm than good? Clin Infect Dis. 2013;56:424–427. doi: 10.1093/cid/cis940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]