Abstract

Background:

Middle managers play key roles in hospitals as the bridge between senior leaders and frontline staff. Yet relatively little research has focused on their role in implementing new practices.

Purpose:

The aim of this study was to expand the understanding of middle managers’ influence in organizations by looking at their activities through the lens of two complementary conceptual frameworks.

Methodology/Approach:

We analyzed qualitative data from 17 Veterans Affairs Medical Centers with high and low potential to change organizational practices. We analyzed 98 interviews with staff ranging from senior leaders to frontline staff to identify themes within an a priori framework reflecting middle manager activities.

Findings:

Analyses yielded 14 emergent themes that allowed us to classify specific expressions of middle manager commitment to implementation of innovative practices (e.g., facilitate improvement innovation, garner staff buy-in). In comparing middle manager behaviors in high and low change potential sites, we found that most emergent themes were present in both groups. However, the activities and interactions described differed between the groups.

Practice Implications:

Middle managers can use the promising strategies identified by our analyses to guide and improve their effectiveness in implementing new practices. These strategies can also inform senior leaders striving to guide middle managers in those efforts.

Key words: implementation, middle managers, organizational innovation, quality improvement

In recent years, changes in the health care environment have led to an increased emphasis on improving quality of care by focusing on safety, efficiency, and value (Kleinman & Dougherty, 2013; Institute of Medicine, 2001). Although there has been a push for changing clinical practice, doing so has proven difficult (Conway & Clancy, 2010; Leape et al., 2009). Often health care organizations’ efforts to implement change in their facility are not successful, with employees frequently facing competing priorities, knowledge barriers, or misaligned incentives (Alexander, 2008; Burnes, 2004; Ferlie, Fitzgerald, Wood, & Hawkins, 2005; Shortell, Bennett, & Byck, 1998). However, implementing innovative practices can help facilitate positive change in health care organizations (Birken, Lee, & Weiner, 2012). Furthermore, implementing quality improvement initiatives, which are defined as “systematic, data-guided activities designed to bring about immediate, positive change in the delivery of health care” (Baily, Bottrell, Lynn, Jennings, & Hastings Center, 2006), can guide health care organizations toward improved quality of care. Middle managers can play an important role in health care organizations by facilitating the implementation of innovation and quality improvement initiatives within their facility (Birken et al., 2012; Bourne & Walker, 2005).

Although current literature has identified a number of individual and organizational factors that influence quality improvement effectiveness, the emphasis has predominately been on senior leaders with a lack of focus on the middle managers’ influence on organizational change efforts (Birken et al., 2012; Feifer & Ornstein, 2004; Hagedorn et al., 2006; Noble, 1999). For example, studies have found that leadership is necessary for innovation and improved performance in a health care facility, and leadership support is essential for organizing resources needed to carry out innovation implementation (Chuang, Jason, & Morgan, 2011; Plsek & Wilson, 2001). In addition, senior leaders who demonstrate support for implementation can influence positive staff involvement in innovation and encourage middle managers to prioritize innovation implementation; however, additional research is needed to evaluate how middle managers influence implementation effectiveness (Birken, Lee, Weiner, Chin, & Shaefer, 2013; Chuang et al., 2011; Klein, Conn, & Sorra, 2001). Studying middle managers is important because they are able to facilitate or enhance innovation implementation processes, implement change, and improve organizational performance (Caldwell, Chatman, O'Reilly, Ormiston, & Lapiz, 2008; Wooldridge & Floyd, 1990). Furthermore, studying middle managers is imperative because they are situated between senior leaders and frontline staff in the organization and have the ability to bridge or create information gaps that may influence innovation implementation in positive or negative ways (Birken et al., 2012). Additional research is needed to gain insight into how differences in middle managers’ actions may influence improvement efforts in organizations.

Theory/Conceptual Model

This article aims to better understand how middle managers can influence organizations by looking at their behavior through the lens of two complementary conceptual frameworks, the theory of middle managers’ role in implementing innovative practices (Birken et al., 2012) and the Organizational Transformation Model (OTM; Lukas et al., 2007), which considers organizational factors in relation to organizational change.

The theory of middle managers’ role focuses specifically on middle managers in an organization and theorizes that they express their commitment to innovation implementation by (a) diffusing information to give employees necessary information about innovation implementation, (b) synthesizing information to provide relevant examples to help employees understand how innovations are implemented, (c) mediating between strategy and day-to-day activities to give employees the tools needed to implement innovations, and (d) selling innovation implementation to encourage employees to use it consistently and effectively (Birken et al., 2012). In addition, Birken et al. (2012) theorize that middle managers can play a key role in managing the demands associated with implementation by identifying actions that need to be prioritized in order to support innovation implementation and engaging employees in innovation implementation. This framework provides the basis for further examining the behaviors of middle managers’ contributions not only toward implementing innovative practices to facilitate quality improvement initiatives but more broadly building improvement capabilities in a health care setting.

The OTM looks more broadly at organizational factors associated with organizational change and the implementation of evidence-based clinical practices (Austin et al., 2014; Lukas et al., 2007, 2010). This framework allows us to examine the relationship between middle manager behavior and the larger organizational context in which they operate and explore whether middle manager behaviors differ in organizations that are supportive of structures and processes that facilitate change and the implementation of new practices versus those that are not. The OTM identifies five critical elements for moving organizations from short-term to more sustained improvements. These five elements include (a) impetus to transform, (b) leadership commitment to quality, (c) improvement initiatives that actively engage staff, (d) alignment to achieve consistency of organization-wide goals, and (e) integration to bridge organizational boundaries (Lukas et al., 2007). In addition, the OTM found that improvement in health care organizations was greater when middle managers were committed to quality, being actively involved in the redesign process, and fully aligned around the importance of quality improvement (Lukas et al., 2007). Furthermore, OTM aligns with the understanding that quality improvement initiatives in a health care facility require organizational change, implementation, and innovation in order to be successful (Kaplan et al., 2010).

The main objectives of this article are to expand on Birken and colleague’s framework using elements of the OTM to gain insight into how middle managers can influence the implementation of innovative practices and the development of improvement capability by asking the following: (a) What are the roles of middle managers in implementing innovative practices? (b) Are there differences in the middle manager activities associated with the larger organizational context in which they operate—and if so, what are they?

Methods

Our analysis of middle managers’ roles and behaviors is based on data collected for a broader management evaluation of grants that focused on strengthening improvement capability in the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA). In this study, we define improvement capability as an organization’s capacity to continuously improve their quality, safety, and values, which requires support in the form of resources, organizational processes, and building an overall culture of improvement (Adler et al., 2003). Middle managers are defined here as staff with a supervisory capacity other than senior leaders (e.g., department managers, program managers, nurse managers, administrative directors, frontline supervisors).

Setting

Starting in 2009, the VA Office of Systems Redesign awarded 30 Improvement Capability Grants to 25 Veterans Affairs Medical Centers (VAMCs) and 5 Veterans Integrated Service Networks nationwide. Grant funding lasted 3 years beginning in FY2009 for 10 grantees and FY2010 for 20 grantees. For the analyses in this article, we include only the VAMC grantees, because middle managers in the network grants were a step removed the medical centers, and therefore, their roles were not comparable. Our analyses focused on interviews conducted in Fall 2011 and Fall 2012, coinciding with the end of grant funding for each facility.

Data Collection

For the full evaluation, selected staff members from each facility participated voluntarily in biannual, in-depth semistructured interviews for the life of their local improvement capability grant, with follow-up interviews occurring at 1 year postgrant. Interviewees were selected purposively to obtain the perspectives of individuals in particular positions related to the grant and/or the development of improvement capability at different levels and in different areas of the medical center. Although the specific individuals varied depending on the organizational structure of each medical center and on the objectives of the local grant, the categories of interviewees included (1) medical center senior leadership; (2) middle managers who were either (a) directly involved in the Improvement Capability Grant (typically the System Redesign Coordinator, the Quality Management Officer, and the designated point of contact for the grant) or, to gain a diversity of perspectives, (b) identified by the site at the evaluators’ request to represent middle managers who had participated in improvement initiatives and those who had not participated; and (3) frontline staff identified by the site as individuals who had participated in improvement initiatives.

Interview protocols asked about grant implementation and included the five OTM elements to guide our assessment of organizational capacity for supporting positive change. The interview protocol also included questions pertaining specifically to middle manager behaviors. The interview protocol can be found in the Appendix (see Appendix, Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com.HCMR/A6). The interviews were conducted in both individual and group formats. Group interviews included participants in similar job categories or individuals who were part of an existing improvement team.

Measures and Analysis

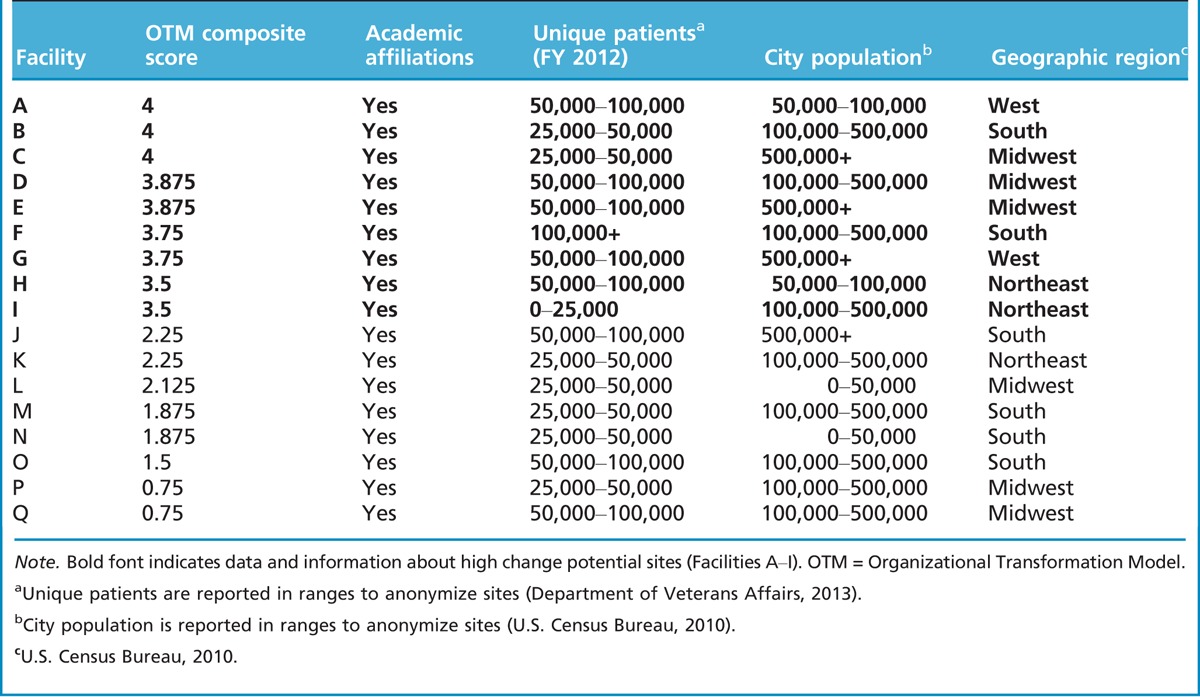

Initially to select a sample of sites for our analysis and later to assess the organizational context in which middle managers operate, we used the OTM composite scores calculated for the full evaluation to characterize the sites, with high OTM scores reflecting high potential for change and low scores reflecting low potential for change. The OTM composite scores were derived from a structured analytic tool organized by the five elements of the OTM, following a method used previously (Lukas, et. al. 2010). After each site visit, team members used the tool to record narrative evidence from the interviews of the operational components of each OTM element. Then each team member independently rated each component with scores ranging from 0 (no evidence of the element present) to 4 (element in place and consistently being used as intended). After the independent ratings, team members compared ratings and developed a consensus score for each element. Composite scores were calculated by averaging scores for the five elements. Although one might expect all sites to have high OTM scores given their interest in applying for grants to build improvement capability, in fact, there was substantial variation, with scores ranging from 0.75 to 4.0. Using these scores, each of the 25 VAMCs was categorized into high, middle, and low terciles for change potential. Our analysis focused on comparisons of high tercile (nine high change potential facilities with composite scores ranging from 3.5 to 4.0) and low tercile (eight low change potential facilities with composite scores ranging from 0.75 to 2.25). We focused on the outlier high and low terciles to maximize the differences between groups and ensure that comparisons were between two distinct groups. We chose to exclude the middle tercile, because the differences in scores between that group and the outlier groups were too small to have confidence they represented real differences. Additional organizational and descriptive information on the 17 included sites can be found in Table 1.

Table 1.

Organizational and descriptive facility information

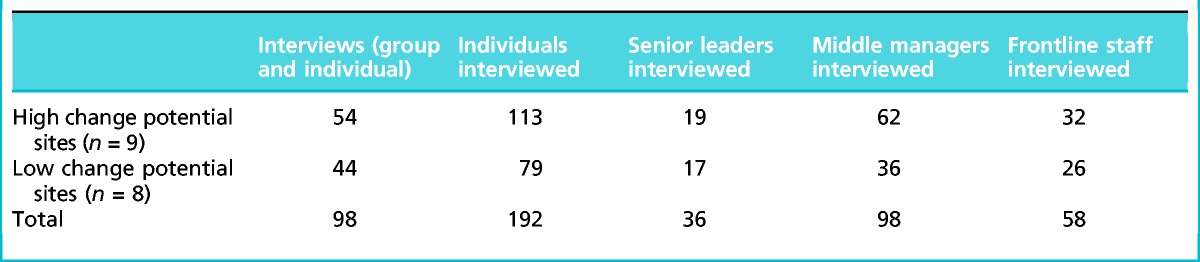

The qualitative data included 54 interviews in the nine high change potential sites and 44 interviews in the low change potential sites. In total, the analysis included 17 facilities, 98 interviews, and 192 individuals. Table 2 summarizes the data sample.

Table 2.

Qualitative data sample

We applied a priori codes pertaining to the four components of middle manager commitment identified in the Birken et al. theory of the middle manager’s role in health care innovation implementation to analyze middle manager activities. The four-person qualitative team came to consensus on the code definitions, and interrater reliability was established in an iterative process. All 98 interviews were then systematically coded for mentions of middle manager behavior by using Nvivo software. In order to ensure maximum saturation, each interview was coded by two members of the team. Subsequent comparative case analysis across all 17 sites yielded emergent themes within each component and identified distinguishing features of high and low change potential sites.

Findings

Overview

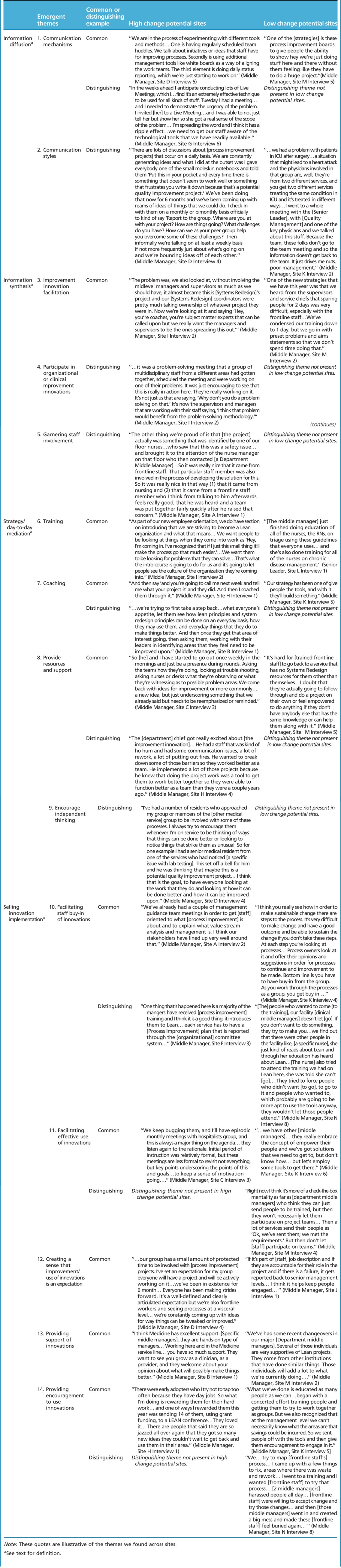

In comparing middle manager behaviors in high and low change potential sites, we found that although most of the emergent themes were present in both groups, the ways in which they were used or expressed differed. In the rest of this section, we describe the 14 themes in greater detail and provide examples of common and distinguishing expressions of the themes. Quotes that are illustrative of each common and distinguishing theme can be found in Table 3.

Table 3.

Emergent themes with illustrative quotes

Information Diffusion

Information diffusion, as defined by Birken et al. (2012), is middle managers disseminating facts, giving employees necessary information about improvement capability activities. We found both common and distinguishing expressions of information diffusion across high and low change potential sites.

Common expressions. We found several communication mechanisms that were present in both the high and low change potential sites.

Communication mechanisms. All middle managers used meetings, informal and formal, specific to the innovation or improvement in order to relay important information. Daily huddles, an example of an informal meeting, were used as a way to pass on information to staff. Huddles are brief, frequent, meetings with staff that are focused on specific aspects of implementation of process improvement (Barnas, 2011; Institute for Healthcare Improvement, 2004).

Middle managers used formal reporting structures (e.g., committee meetings) to convey information about innovations laterally and upward in the organization. It was then up to middle managers to relay any information gathered during these meetings back to their staff.

Middle managers used coaching as a way to communicate information about improvements. Middle managers in this role delivered information to staff by facilitating improvement projects, in this context providing staff with pertinent information regarding the implementation of innovation.

Middle managers used electronic modes of communication such as e-mail, SharePoint, and other Web-based communications. In addition, they used visual aids to convey information to staff. These visual aids include posters, white boards, and videos.

Distinguishing expressions. The overarching difference between middle managers’ information diffusion in high and low change potential sites was in their communication styles.

Communication styles. Middle managers in high sites communicated in ways that were informal but clear, direct, transparent, multidisciplinary, and multidirectional. Middle managers in low sites communicated information about innovations in ways that were formal, often fragmented, and unidirectional with fewer outlets for staff feedback.

These differences in communication styles effected middle manager communication mechanisms. Although similarities existed, we found that the way in which these communication mechanisms were carried out varied. For example, differences existed in how middle managers used formal reporting structures in the organization. In the low change potential sites, middle managers used these structures mainly to report information to senior leaders in the organization. The focus on reporting upward, along with the differences in communication styles of middle managers in high and low sites, negatively affected whether that information made it back to the frontline staff.

Alternatively, middle managers in the high change potential sites used formal facility or unit rounding to not only convey important information to their staff but also to gather important information. Their physical presence on the unit allowed them to observe implementation, deliver important information, and garner feedback from staff. The presence of rounding was not cited in low change potential sites. In addition, middle managers in high sites held events or forums specific to the innovation in order to convey information.

Furthermore, high change potential site middle managers used electronic communication mechanisms in more active and multidirectional ways than low change potential site middle managers. For example, middle managers in high sites used online meetings, which allow staff throughout the organization to participate and influence the implementation of innovative practices, whereas middle managers in low sites conveyed information in a unidirectional fashion by e-mailing staff or posting information to organizational Web pages. Lastly, high change potential middle managers used visual data like statistical dashboards and flow charts of processes to convey information about the innovation.

Information Synthesis

Birken et al. (2012) define information synthesis as integrating and interpreting facts, making general information about improvement capability activities relevant to unique organizations and employees. Again, we found both common and distinguishing middle manager expressions of information synthesis across high and low change potential sites.

Common expressions. One theme that was present across both high and low sites was improvement innovation facilitation.

Improvement innovation facilitation. For improvement projects that facility staff identified as unsuccessful or not meeting objectives, middle managers analyzed where the project broke down and identified the root cause of that failure. Some of the root causes identified were organizational barriers, staff engagement, and lack of resources.

Middle managers took this information and made improvements to their facilitation of the project in order to gain or maintain involvement from staff and successfully guide the project. They synthesized the lessons learned from the project and identified generalizable themes or best practices that could be applied to future projects. For example, middle managers learned the importance of keeping the team involved on all aspects of the project instead of having a coach direct every step.

They also recognized the difficulty of pulling staff away from their clinical duties for extended periods of time, instead finding that a shorter or just-in-time training was more successful.

Distinguishing expressions. Two themes emerged that exhibit the differences between middle managers in high and low change potential sites.

Participation in organizational or clinical improvement innovations. The first theme was middle manager participation in organizational or clinical improvement innovations. In the high sites, middle managers identified problem areas in the medical center and made suggestions for improvements to remedy the issue. In addition, they participated in or facilitated improvement initiatives to resolve the process issues in the organization. For example, in one site middle managers discovered a duplication of efforts in the medical center and participated in an improvement project that streamlined the process and eliminated that duplication.

Garnering staff involvement. The second distinguishing theme between high and low change potential sites was garnering staff involvement. Middle managers in the high sites recognized the importance of soliciting improvement ideas from their staff; those that are closest to the work being targeted for improvement. Middle managers often solicited ideas through the use of suggestion cards with which the frontline staff could submit their ideas. In one high site, those ideas were discussed as a group twice a week, with middle managers encouraging staff to submit their own ideas. This in turn empowered the staff to participate in improvement innovations.

For staff members that resisted improvement work, middle managers in the high change potential sites tried to determine the core reason for lack of participation. For example, middle managers discovered that many frontline employees wanted to participate in improvement projects but could not afford the time with their competing clinical priorities. Some frontline employees were disinterested because they saw a particular improvement methodology as a passing fad, and others were not yet provided with needed training and thus were not ready to participate in a project.

Strategy/Day-to-Day Activity Mediation

Strategy/day-to-day activity mediation according to the Birken et al. (2012) framework is identifying tasks required for improvement capability activities, giving employees the tools necessary to implement innovation.

Common expressions. We found three emergent themes that were present across all sites.

Training. The first theme was training. Middle managers in all sites provided training to educate their staff on how to carry out improvement work in the facility. Training pertinent to the implementation of improvement work was provided in many forms, including online and in person.

Coaching. A second theme that emerged across all sites was coaching. Middle managers encouraged the use of improvement tools (e.g., process mapping or value stream mapping) and coached their staff on how to effectively utilize those tools. For example, middle managers would assign tasks after staff received training and then provide feedback and support related to those tasks in order to encourage staff learning. This method of coaching ensured that staff understood how to implement the improvement tools in their own work.

Providing resources and support. Lastly, middle managers at all sites provided resources and support to staff to ensure that they had the resources and knowledge needed to complete a project. Examples of how provision of resources and support differed in high and low change potential sites are given below.

Distinguishing expressions. Although the themes above were present in all sites, the ways in which middle managers embodied those themes varied.

Middle managers in high change potential sites were found to incorporate examples of relevant improvement work into trainings. This was done by asking staff members to bring real issues they are facing in their department and then creating improvement projects to address those issues. In addition, middle managers facilitating training at these sites cited successful improvement projects during training to give staff members a better understanding of how improvement work can be carried out in their facility. In contrast, low change potential sites reported middle managers adapting the curriculum to meet the needs of staff members but did not mention utilizing real department issues for improvement projects or discussing other successful projects from the facility.

Middle managers in high sites coached staff until they were ready to use tools on their own, whereas low sites did not. For example, middle managers in high OTM sites met with staff frequently to talk about issues staff members may be having with their improvement work, clarified questions, and encouraged continued use of improvement work. In addition, middle managers at high OTM sites worked closely with staff members to address barriers they were facing and followed up in a timely manner with suggestions on how to address any barriers and issues staff encountered. This level of support was not as prominent at low OTM sites.

Encouraging independent thinking among staff. The final emergent theme pertaining to strategy/day-to-day mediation, encouraging independent thinking among staff, was present only in high change potential sites. Middle managers in these sites were found to foster staff members’ independence by not just giving them solutions to problems but also working with them to improve the process. By doing this, middle managers encouraged staff to use the knowledge gained in training to solve the issues they were facing and empowered them to work more independently in the future.

Selling Innovation Implementation

Birken et al. (2012) define selling improvement capability activities as justifying innovation implementation, encouraging employees to consistently and effectively use innovation. Five common themes emerged across all sites, although there were distinguishing expressions of those themes by middle managers in high and low change potential sites.

Common expressions.

Facilitating staff buy-in of innovative practices. Middle managers at all sites facilitated staff buy-in of innovative practices. Middle managers described and provided evidence of the utility of an innovation in order to achieve staff buy-in. Examples included holding meetings to educate staff on an improvement intervention or demonstrating hands-on use of the intervention and associated processes in order to ensure staff buy-in.

Facilitating effective use of innovative practices. Facilitating effective use of innovative practices emerged as a theme across all sites, with middle managers providing guidance on the application of an adopted innovation. Middle managers revisited key points and goals of training with staff and provided instruction to reinforce the use of improvement tools.

Creating the sense that improvement work is an expectation. Middle managers at all sites created the sense that improvement work was an expectation. Middle managers set this expectation by explicitly stating improvement work in employee job descriptions, holding people accountable for assigned tasks and protecting time for improvement initiatives.

Providing support of the innovations. In addition, middle managers sold innovative practices by providing support of the innovations. Interviewees reported that middle managers were generally supportive of and willing to assist with improvement initiatives. For example, at one site, interviewees felt middle managers facilitated individuals’ growth as clinicians and care providers and were open to ideas for improvement.

Providing encouragement for staff to use innovative practices. Finally, middle managers across all sites provided encouragement for staff to use innovative practices. Encouragement from middle managers to utilize innovations was apparent through staff involvement in training programs and the use of incentives such as awards or financial compensation.

Distinguishing expressions. Although middle managers in both high and low change potential sites exhibited all five themes pertaining to selling innovation implementation, there were notable differences in how their behaviors manifested.

High change potential sites more consistently utilized middle managers as facilitators of improvement work with multiple managers across service lines promoting improvement initiatives. For example, one site with high change potential had many service chiefs across several service lines engaged in and promoting Improvement Capability Grant activities.

Middle managers at high OTM sites also used more explicit, standardized structures and processes (e.g., improvement committees, management guidance teams, regular meetings) to facilitate staff buy-in and effective use of innovations. In contrast, although low change potential sites showed evidence of encouraging staff to use innovations, some employed punitive measures to enforce these efforts, resulting in less staff buy-in.

Lastly, interviewees from low change potential sites reported more barriers (as compared to high change potential sites) associated with lack of successful selling of innovation implementation. These barriers resulted in inadequate staff buy-in and ineffective use of innovations.

Discussion

This study expands the theory of middle managers’ role in health care innovation implementation developed by Birken et al. (2012) by adding to the empirical base and identifying 14 emergent themes representing specific ways in which middle managers express their commitment to improvement capability. The study also contributes to theory by increasing our understanding of the specific roles of organizational context in that behavior.

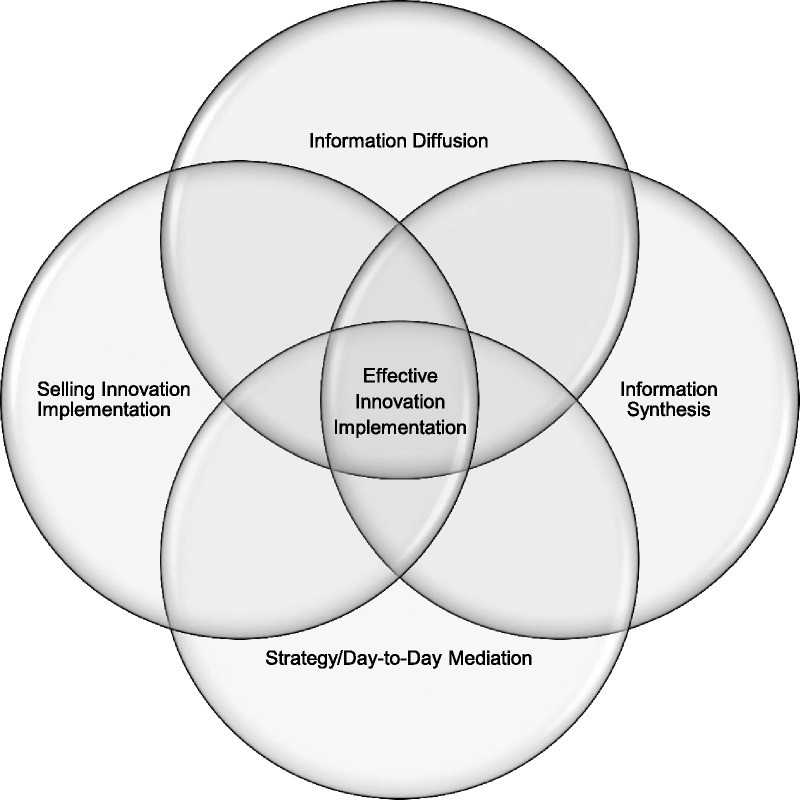

Although each emergent theme is distinct, they are also interrelated. We found multiple areas where the components of middle managers’ commitment to implementation of innovation drew on each other. For example, in order to sell innovation implementation to frontline staff, middle managers were influenced by synthesis and diffusion of information as well as meditation between the strategic and day-to-day tasks necessary to implement innovation. Another example prominent in our data was that in order for middle managers to diffuse information to staff they had to assess strategic and day-to-day tasks required for implementation, synthesize the information about implementation, and concurrently utilize selling of the implementation. Preliminary analyses of interview passages coded for multiple themes support these examples. Building on Birken and colleagues theory, we posit that managers’ influence is most effective when these components and our underlying emergent themes build on each other and do not occur in isolation (see Figure 1). Future research can be designed to test and further explicate these relationships.

Figure 1.

Interrelatedness of the components of middle managers’ commitment to implementation of innovation

We also found that, within the emergent themes, middle manager behavior was influenced by organization-wide implementation policies and practices. Although the general finding of links between behavior and context was not unexpected, our analyses provide new details about those dynamics. On the one hand, middle managers in all sites exhibited behaviors that facilitate the uptake of innovative practices and building of an improvement culture, a finding that has important implications for practice. For example, middle managers in all sites communicated pertinent information about organizational improvement efforts and culture to staff and provided staff with training related to those efforts.

However, middle managers in high change potential medical centers stood out from those in low change potential sites on a number of the themes identified. In contrast with middle managers in low change potential sites, these middle managers generally took more initiative and were more interactive in carrying out the 14 emergent themes. These middle managers go a step further in interactions with staff, taking the initiative to support new practices and to engage staff in the change efforts. Communication with staff was more active, interactive, and informal, with an emphasis on being multidirectional. Middle managers in these high change potential sites encouraged independent thinking in staff, while at the same time encouraging them to bring real improvement problems forward. These middle managers not only train staff in using improvement tools but also mentor and coach them with real improvement-related examples until they fully understand and are ready to use these tools and skills. In addition, these middle managers serve as facilitators of improvement work, utilizing explicit structures and processes to facilitate staff buy-in and effective use of innovations. One component of this facilitation is working closely with staff to address barriers to improvement. These middle manager actions appear to both facilitate implementation and reduce barriers to change and, thus, offer promising practices for middle managers seeking to facilitate the implementation of innovative improvement practices, as discussed in Practice Implications.

To look more closely at organizational influence on the distinguishing behaviors of managers in high and low change potential sites, we examined them in relation to the drivers of organizational change defined in the OTM. Organizations with high change potential scores are characterized by senior managers who support and are personally involved in improvement activities; in improvement efforts that are clearly aligned with organizational priorities and with resource and accountability systems; and where staff at all levels are engaged, knowing how their work contributes to the larger organization and actively participating to improve the organization. Our findings of more active middle managers in high change potential sites who are comfortable with and skilled in facilitating improvement are consistent with these organizational characteristics. First, in an organization with an improvement culture, there is an expectation that change is possible and that working to improve is expected and rewarded. Both middle managers and frontline staff are used to working in this way and working with each other. Thus, we would expect not only that middle managers will be more active in their commitment to improvement but also that staff will be willing to participate and more likely to buy-in to the new practice—a frequent barrier in low change potential sites. Second, in an organization with strong leadership direction and support for improvement and with aligned resources and accountability, improvement and innovation are linked to the priorities and management structures of the medical center. Thus, we would expect that middle manager implementation activities will be supported by reporting structures, resource allocations, and policies that provide lines of communication and tools to facilitate their improvement efforts, such as protected time for staff to work on improvement activities—mentioned often in low change potential sites as a barrier to staff involvement. Although we offer promising practices in this article specifically for middle managers, our findings of the strong link between active middle manager behavior and a larger organization context with high change potential offer insights about broader facilitators for implementing innovations and building improvement capability. In addition, although the study has shown a link between organizational context and middle manager behaviors, organizational context by itself should not rule out middle managers in all organizations taking these promising practices into consideration.

Limitations

Our study was not without limitations. Like most observational studies, we are limited in our ability to assert causality. However, the larger evaluation is based on data from a span of 4–5 years, with detailed reporting of middle manager behaviors, which allow us insight into the middle manager’s role in the organization. As mentioned previously, the themes and promising practices identified are interrelated and can often be influenced by factors outside of middle manager’s control.

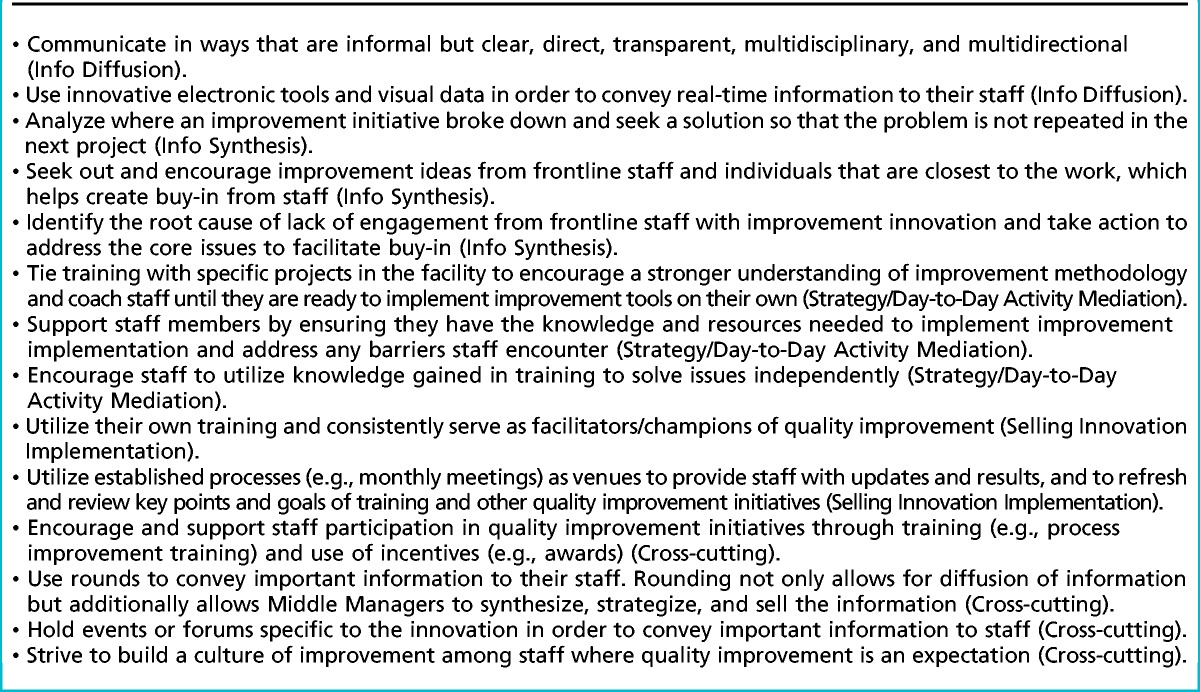

Practice Implications

Ultimately, our study identified 14 practical promising practices, summarized in Table 4, which may help middle managers in their efforts to implement innovations. Our study was based solely on data collected from the VA. Although this setting contains several unique characteristics, it also shares commonalities with private health care systems, including the middle manager’s role in the organization. It is because of these similarities that our findings are generalizable to a larger audience. By focusing on these promising practices, middle managers may be able to increase their effectiveness in implementing new improvement practices in their organization.

Table 4.

Promising practices for middle managers

These practices were identified by comparing and contrasting themes identified in the high and low change potential sites, which suggests that they may be easier to accomplish in organizations with cultures and structures that are supportive of change. At the same time, however, the promising practices are specific enough to benefit middle managers in most organizations. Some can be implemented independently within the managers’ units and, through successful application, may potentially be used to leverage broader change in the organization. In addition, these promising practices may inform senior leaders of areas for improvement when guiding middle managers in improvement efforts.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This study was based on an evaluation supported by the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs and approved by the VA Boston Healthcare System Institutional Review Board. The contents of this article do not represent the views of the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs or the United States Government. The authors would like to acknowledge the contributions of the larger evaluation team at the Center for Healthcare Organization and Implementation Research, specifically the following colleagues for their editorial comments: Lauren Babich, PhD, Sally Holmes, MBA, and Michael Shwartz, PhD.

Footnotes

The authors have disclosed that they have no significant relationship with, or financial interest in, any commercial companies pertaining to this article.

Supplemental digital content is available for this article. Direct URL citations appear in the printed text and are provided in the HTML and PDF versions of this article on the journal’s Web site (www.hcmrjournal.com).

References

- Adler P. S., Riley P., Kwon S. W., Signer J. K., Lee B., Satrasala R. (2003). Performance improvement capability: Keys to accelerating performance improvement in hospitals. California Management Review, 45(2), 12–33. [Google Scholar]

- Alexander J. A. (2008). Quality improvement in healthcare organizations: A review of research on QI implementation. Washington, DC: Institute of Medicine. [Google Scholar]

- Austin E. L., Pollio D. E., Holmes S., Schumacher J., White B., Lukas C. V., Kertesz S. (2014). VA’s expansion of supportive housing: Successes and challenges on the path toward Housing First. Psychiatric Services, 65(5), 641–647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baily M. A., Bottrell M., Lynn J., Jennings B. & Hastings Center. (2006). The ethics of using QI methods to improve health care quality and safety. The Hastings Center Report, 36(4), S1–S40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnas K. (2011). ThedaCare's business performance system: Sustaining continuous daily improvement through hospital management in a lean environment. Joint Commission Journal on Quality and Patient Safety, 37(9), 387–399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birken S. A., Lee S. Y., Weiner B. J. (2012). Uncovering middle managers’ role in healthcare innovation implementation. Implementation Science, 7, 28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birken S. A., Lee S. Y., Weiner B. J., Chin M. H., Schaefer C. T. (2013). Improving the effectiveness of health care innovation implementation middle managers as change agents. Medical Care Research and Review, 70(1), 29–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourne L., Walker D. H. (2005). The paradox of project control. Team Performance Management, 11(5/6), 157–178. [Google Scholar]

- Burnes B. (2004). Emergent change and planned change–competitors or allies? The case of XYZ construction. International Journal of Operations & Production Management, 24(9), 886–902. [Google Scholar]

- Caldwell D. F., Chatman J., O'Reilly C. A., 3rd, Ormiston M., Lapiz M. (2008). Implementing strategic change in a health care system: The importance of leadership and change readiness. Health Care Management Review, 33(2), 124–133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chuang E., Jason K., Morgan J. C. (2011). Implementing complex innovations: Factors influencing middle manager support. Health Care Management Review, 36(4), 369–379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conway P. H., Clancy C. (2010). Charting a path from comparative effectiveness funding to improved patient-centered health care. The Journal of the American Medical Association, 303(10), 985–986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Department of Veterans Affairs. (2013). VHA facility quality and safety report fiscal year 2012 data. Retrieved from http://www.va.gov/HEALTH/docs/QandS_Report_2013_data_tables_fy12_data.pdf

- Feifer C., Ornstein S. M. (2004). Strategies for increasing adherence to clinical guidelines and improving patient outcomes in small primary care practices. Joint Commission Journal on Quality and Safety, 30(8), 432–441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferlie E., Fitzgerald L., Wood M., Hawkins C. (2005). The nonspread of innovations: The mediating role of professionals. Academy of Management Journal, 48(1), 117–134. [Google Scholar]

- Hagedorn H., Hogan M., Smith J. L., Bowman C., Curran G. M., Espadas D., Sales A. E. (2006). Lessons learned about implementing research evidence into clinical practice. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 21(Suppl. 2), S21–S24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Institute for Healthcare Improvement. (2004). Huddles. Retrieved from http://www.ihi.org/resources/Pages/Tools/Huddles.aspx [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine. (2001). Crossing the quality chasm. Washington, DC: National Academy Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan H. C., Brady P. W., Dritz M. C., Hooper D. K., Linam W. M., Froehle C. M., Margolis P. (2010). The influence of context on quality improvement success in health care: A systematic review of the literature. The Milbank Quarterly, 88(4), 500–559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein K. J., Conn A. B., Sorra J. S. (2001). Implementing computerized technology: An organizational analysis. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 86(5), 811–824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleinman L. C., Dougherty D. (2013). Assessing quality improvement in health care: Theory for practice. Pediatrics, 131(Suppl. 1), S110–S119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leape L., Berwick D., Clancy C., Conway J., Gluck P., Guest J.… Lucian Leape Institute at the National Patient Safety Foundation. (2009). Transforming healthcare: A safety imperative. Quality & Safety in Health Care, 18(6), 424–428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lukas C. V., Engle R. L., Holmes S. K., Parker V. A., Petzel R. A., Seibert M. N., Sullivan J. L. (2010). Strengthening organizations to implement evidence-based clinical practices. Health Care Management Review, 35(3), 235–245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lukas C. V., Holmes S. K., Cohen A. B., Restuccia J., Cramer I. E., Shwartz M., Charns M. P. (2007). Transformational change in health care systems: an organizational model. Health Care Management Review, 32(4), 309–320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noble C. H. (1999). The eclectic roots of strategy implementation research. Journal of Business Research, 45(2), 119–134. [Google Scholar]

- Plsek P., Wilson T. (2001). Complexity science: Complexity, leadership, and management in healthcare organisations. British Medical Journal, 323(7315), 746–749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shortell S. M., Bennett C. L., Byck G. R. (1998). Assessing the impact of continuous quality improvement on clinical practice: What it will take to accelerate progress. The Milbank Quarterly, 76(4), 593–624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Census Bureau. (2010). American FactFinder community facts. Retrieved from http://factfinder.census.gov/faces/nav/jsf/pages/index.xhtml

- Wooldridge B., Floyd S. (1990). The strategy process, middle management involvement, and organizational performance. Strategic Management Journal, 11(3), 231–241. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.