Abstract

Background

Clinical trials that study cancer are essential for testing the safety and effectiveness of promising treatments, but most people with cancer never enroll in a clinical trial — a challenge exemplified in racial and ethnic minorities. Underenrollment of racial and ethnic minorities reduces the generalizability of research findings and represents a disparity in access to high-quality health care.

Methods

Using a multilevel model as a framework, potential barriers to trial enrollment of racial and ethnic minorities were identified at system, individual, and interpersonal levels. Exactly how each level directly or indirectly contributes to doctor–patient communication was also reviewed. Selected examples of implemented interventions are included to help address these barriers. We then propose our own evidence-based intervention addressing barriers at the individual and interpersonal levels.

Results

Barriers to enrolling a diverse population of patients in clinical trials are complex and multilevel. Interventions focused at each level have been relatively successful, but multilevel interventions have the greatest potential for success.

Conclusion

To increase the enrollment of racial and ethnic minorities in clinical trials, future interventions should address barriers at multiple levels.

Introduction

Clinical trials focused on cancer research are essential for testing the safety and effectiveness of potential treatments and translating new knowledge into tangible benefits for patients; they also represent options for novel therapy for cancer.1,2 However, approximately 2% to 3% of all patients with cancer ever enroll in a trial. 3,4 Estimates of the number of trials that fail to meet scientific objectives because of insufficient accrual rates range from 22% to 50%.5,6 Low accrual rates jeopardize the ability of researchers to assess the safety and effectiveness of new approaches to cancer care, wastes resources, precludes follow-up studies, and reduces the ability of our clinical research system to translate research into evidence-based practice.6–8

Underenrollment is an even greater challenge among racial and ethnic minorities — particularly African Americans — despite a requirement by the National Institutes of Health that members of minority populations be represented in clinical research.1,3,4,9–11 A systematic review compared the proportion of underrepresented minority participants in phase 3 cancer treatment and prevention clinical trials conducted between the periods 1990 to 2000 and 2001 to 2010.12 In the treatment studies conducted between 2001 and 2010 that reported race/ethnicity, the reviewers found that 82.9% of participants were white, 6.2% were African American, 3.3% were Asian, 2.2% were Hispanic, and 0.1% were Native American.12 This is in contrast to studies conducted between 1990 and 2000, in which 89% of participants were white, 10.5% were African American, 0.4% were Hispanic, and 0.04% were Asian.12 In other words, even though the proportion of white participants decreased, whites continued to comprise a large majority of participants in cancer treatment trials, and the proportion of African American participants decreased between the periods 1990 to 2000 and 2001 to 2010. However, during those same periods, the proportion of African American participants in clinical prevention trials increased (5.5% from 1990–2000, 11.6% from 2001–2010).12

Although several patient populations are underrepresented in clinical trials, including elderly patients (≥65 years), residents of rural areas, and those with low socioeconomic status, the current review focuses on racial and ethnic minority underenrollment for several reasons.4,10,13–16 Racial and ethnic minorities — particularly African Americans — bear the greatest cancer burden in the United States, so they should be adequately represented in cancer research.17–19 Under-representation of racial and ethnic minorities also limits the generalizability of research findings.20–22 The Institute of Medicine has recommended that every individual with cancer have access to high-quality clinical trials, so we believe that under-representation of racial and ethnic minorities represents a disparity in health care.2 Underenrollment of racial and ethnic minorities in clinical trials may therefore contribute to preventable disparities in treatment outcomes and survival.1,17,23,24

Purpose

The purpose of this paper is to identify and describe potential barriers to the enrollment of racial and ethnic minorities in clinical trials at the system, individual (health care professional, patient, and family), and interpersonal levels (eg, doctor–patient relationship).

The paper also describes selected examples of evidence-based interventions already implemented to address some of these barriers at the patient-, physician-, and doctor–patient interpersonal communication levels. We take this approach because multilevel interventions, as compared with single-level interventions, may have the greatest potential to achieve substantial and sustained change and to produce additive — and possibly multiplicative — effects.25,26

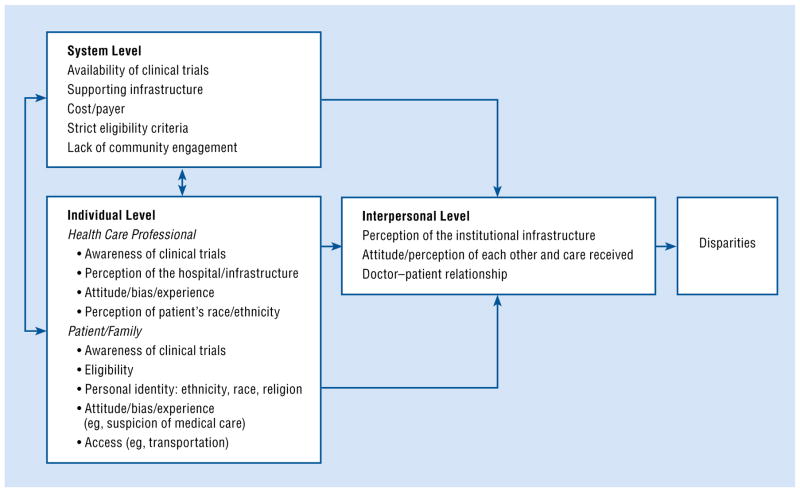

We propose a multilevel model derived from general systems theory, which posits that organizations are comprised of discrete but related levels (Fig 1).27 Our multilevel model demonstrates how system- and individual-level barriers contribute to interpersonal-level barriers to the enrollment of racial and ethnic minorities in clinical trials.

Fig 1.

A multilevel model of factors contributing to disparities in clinical trials.

System-Level Barriers

Barriers at the level of health care systems and hospitals include the limited number of trials nationally and regionally available; hospital infrastructures that lack the resources to support trials; financial costs to hospitals and patients; restrictive study designs and eligibility criteria; and lack of community engagement. Many of these barriers have a disproportionate effect on minority enrollment because members of minority populations are more likely to receive care at under-resourced hospital systems where few clinical trials are available, to be underinsured, and to present with comorbidities that make them ineligible for trials that may be available.28–30

Available clinical trials supported by a well-resourced and functional infrastructure are critical to the enrollment of minority patients.31 For example, this infrastructure includes staff dedicated to enrolling, managing, and tracking participants; data collection and management capabilities; and an efficient Institutional Review Board. Without a functional infrastructure, efforts at increasing the enrollment of minorities in other levels are less likely to be successful.31–33 The financial costs of enrollment to institutions and individual patients affect all patient populations, but they have a disproportionate impact on minorities compared with nonminorities. Minorities are more likely to be underinsured, to seek care at under-resourced hospitals, and to have concerns about the cost of participating in a clinical trial.29,34 In addition, lack of or inadequate health insurance acts as a barrier to enrollment in clinical trials for several under-represented populations, including racial and ethnic minorities.29,35

As a way to enhance community engagement, the infrastructure of clinical trials should exist within a medical institution that has an established, trusted relationship with the members of the community it serves.36 Building trust within a community requires that an institution conduct its research in an open and honest manner that involves a complete and accurate description of the known and potential differences in the risks and benefits for different racial and ethnic populations. Ways and means to facilitate and encourage open discussions into research ethics, including the past abuse of minority patients in research, are needed, as are efforts to create and sustain partnerships with the community to share ownership of the research.37–40

In response to system-level barriers, several national, regional, and consortia efforts have implemented programs to increase enrollment among racial and ethnic minority populations.8,41,42 For example, the Minority-Based Community Clinical Oncology Program of the National Cancer Institute was designed to increase minority participation in cancer clinical trials by developing outreach efforts at health care institutions that serve large numbers of minority patients with cancer.32 Mc-Caskill-Stevens et al32 reported that the success of this program was largely due to system- and hospital-level factors, such as opening trials that matched the clinical characteristics of patient populations and developing relationships with local physicians and cancer advocacy groups that increased their willingness to enroll or refer minority patients to clinical trials. However, their success was limited by lack of funding for minority outreach activities, lack of system support to provide staff and mentoring for minority investigators, and lack of funding to provide protocol-related drugs and related services for uninsured patients.32

The Community Oncology Research Program of the National Cancer Institute is a national network of health care professionals, investigators, and organizations that conducts cancer-related research across the United States.43 The program focuses on determining the reasons for the existence of racial and ethnic disparities in clinical trial participation, as well as ways to increase the participation of racial and ethnic minorities in clinical trials through numerous interventions.43 Because its inauguration was in 2014, evaluation data have not yet been published.

In recent years NRG Oncology convened a workshop on the challenges and opportunities of clinical trial enrollment in an attempt to address the issue of minority underenrollment in clinical trials.44 Experts in oncology, including members of the Minority-Based Community Clinical Oncology Program of the National Cancer Institute, and a large patient advocacy group were in attendance.44 Ten themes emerged regarding future plans and interventions to increase minority enrollment in clinical trials; of these, 8 themes focused on the system level44:

Target recruitment and emphasize the personalized nature of trials as a way to improve minority enrollment to specialized studies

Define study populations at the molecular level rather than by traditional and less-precise eligibility criteria

Make the delivery of cancer care research available at the community and academic levels so studies are designed to better improve health outcomes

Improve local infrastructure by providing translation and navigation services and research-friendly electronic medical records

Expand and standardize the collection of demographics and real-time information about accruals for all patient populations

Strengthen the infrastructure of information technology

Improve recruitment, training, and mentorship of young investigators, particularly those of racial and ethnic minority backgrounds and those with an interest in cancer disparities

Continue and improve budgetary support from the US Congress for all clinical cancer research within the National Cancer Institute

Individual-Level Barriers

Our multilevel model emphasizes individual factors that may present a barrier to the enrollment of racial and ethnic minorities in clinical trials. The term individuals is meant to refer to persons directly involved in the clinical trial enrollment process, including health care professionals, patients, and their family members. Barriers on a system level can influence how individuals perceive the enrollment of minority patients in clinical trials and how they communicate about trials. For example, an investigation of physician perceptions of clinical trials and trial support available at their institution revealed that most physicians held a favorable attitude about clinical trials, both as a source of high-quality patient care and as a professional benefit to themselves.33 However, approximately two-thirds of practicing oncologists perceived a lack of needed infrastructure to conduct trials.33 This included a low number of trials open and lack of nonphysician staff to support patient participation in clinical trials.33 Similarly, the health care system can also influence patient concerns about the cost of participating in trials and, in turn, their decisions to enroll or not enroll in a clinical trial.34 Thus, these 2 levels are linked in terms of whether and how health care professionals and minority patients discuss clinical trials and whether minority patients agree to enroll.

Health Care Professionals

Health care professionals play a critical role in facilitating or inhibiting the enrollment of a diverse population of patients into clinical trials.33,45,46 Several factors are related to the reluctance of health care professionals to enroll their patients in trials, regardless of whether or not they are members of minority groups themselves.

A major barrier is the lack of awareness of available trials: Health care professionals must be made aware of national, regional, and local trials currently taking patients and the eligibility criteria for each of those trials to discuss such enrollment with their patients.45,46 In addition, the attitudes of health care professionals about trials and discussing such trials with patients and their families present a major barrier to trial enrollment, and they likely affect the quality of communication during discussions of clinical trials.33,45 For example, health care professionals may not fully agree with or understand the scientific value of trials in general or the details of specific trials; they may feel they do not have adequate system support; or they may have concerns about practical issues such as strict protocol designs, patient inconvenience, and added work for the health care staff.33,45 Some clinicians find it difficult to reconcile the roles of physician and researcher, or are concerned about unduly influencing patient decisions about enrolling in a clinical trial.47

Some attitudinal factors are specific to the enrollment of minority patients, such as the concern about harming the therapeutic relationship. For example, a focus-group study involving community physicians found that some physicians were hesitant to discuss clinical trials with their African American patients because of their perceptions that African Americans are often mistrustful of physicians and medical institutions.48

An additional attitudinal factor that may deter health care professionals from discussing trials with minority patients is implicit bias against members of minority groups. Prior research has shown that implicit bias (comprised of conscious and unconscious biases) among physicians toward members of minority groups has an impact on clinical interactions with minority patients.49–52 We are unaware of studies that specifically investigate whether the implicit bias of health care professionals is a barrier to the enrollment of minorities in clinical trials, but research in other contexts suggests that some physicians may have implicit negative attitudes about African Americans that may lead them to believe they will be poor candidates for clinical trials.53–56 For example, research has shown that primary care physicians tend to trust minority patients less than they trust white patients.54 Research has also shown that physicians high in implicit bias may view their minority patients as less likely to comply with recommended treatment,57 and that physicians’ diagnoses and treatment of African Americans can be influenced by racial stereotypes.55 This body of research suggests that physicians may limit offers for trial enrollment to those patients they perceive as good study candidates so that the studies will be conducted in a timely and efficient manner.58 This may mean physicians are less likely to offer a clinical trial to patients who are racial and ethnic minorities than to white patients, and research has shown this to be the case.46,59

Recommendations have been made for evidence-based approaches to reduce the impact of health care professional bias in clinical interactions.60 One approach is to train health care professionals in the use of high-quality patient-centered communication, which requires the development of a positive interpersonal relationship.61 Patient-centered communication focuses on patient needs and perspectives, and it does not ignore the racial and ethnic background of the patient, because doing so denies an important part of an individual.61 Results of the NRG Oncology workshop identified the commitment of physicians and study investigators to the enrollment of minorities into clinical trials as critical to the future of clinical cancer research.44 They also emphasized that physicians must be culturally sensitive and aware of the impact appropriate communication and patient trust have on minority enrollment in clinical trials.44

Several communication curricula are available, but they include little training on discussing clinical trials with patients or with specific patient populations.62 One exception is an Australian study, which reported on a 1-day intensive course for physicians to improve aspects of their communication related to discussing clinical trials with patients.45 Results showed that physicians improved in some shared decision-making behaviors and were more likely to describe some of the key clinical or ethical aspects of the trial.63 However, we are unaware of any specific training curriculum that emphasizes ways to communicate about clinical trials with minority patients.

Patients and Families

Some major barriers to enrolling racial and ethnic minority patients in clinical trials are that patients are often not aware they are eligible for an existing trial; they are often underinsured and cannot afford the extra expenses related to trial participation; and they may not meet the clinical criteria due to comorbid conditions or age restrictions.29,30,64 Similar to health care professionals, patients hold attitudes and beliefs that may also affect their willingness to participate and the way they communicate during clinic visits in which trials are discussed.65,66 Despite this, research shows that, overall, minorities are as likely as whites to consent if they are offered a trial.30,59,67,68 For example, an assessment of more than 4,000 racially diverse patients with cancer found no significant association between race and ethnicity and refusal to participate in a clinical trial or lack of desire to participate in research.30 Similarly, Katz et al69 implemented the Tuskegee Legacy Project to address and understand if and how the Tuskegee syphilis experiment impacted the trial recruitment and retention of African Americans into biomedical studies. The researchers found no difference in self-reported willingness among African Americans to participate in biomedical research.69 A systematic review of the available research on the factors that influence participation in clinical trials among African Americans concluded that the strongest inhibitors of participation were low levels of knowledge and lack of awareness of clinical trials.66 The most important facilitators of participation were social support and recommendations from physicians, family members, and friends.66

Several patient-focused interventions designed to improve knowledge of, attitudes about, and participation in clinical trials among racial and ethnic minority patients has been developed and tested.70,71 A multicenter, randomized trial of a web-based, interactive, educational tool was designed to increase knowledge, decrease attitudinal barriers, and improve preparation for making decisions about clinical trial enrollment among minority patients with cancer.70 At baseline, the level of knowledge about clinical trials, attitudinal barriers to participation, and preparation for decision-making among the participants were assessed.70 Prior to their initial visit with an oncologist, patients in the intervention arm watched a set of brief, individually tailored videos addressing knowledge and attitudinal barriers to clinical trial participation, whereas those assigned to the control arm received text-based general information about clinical trials from the National Cancer Institute. The study results showed that, compared with baseline levels, participants in the intervention and control arms both showed improved knowledge (control arm: mean [standard deviation {SD}] = 2.5 [3.1]; intervention arm: mean [SD] = 3.2 [3.1]; P < .001) and decreased attitudinal barriers (control arm: mean [SD] = −0.2 [0.4]; intervention arm: mean [SD] = −0.3 [0.5]; P < .001).70 However, patients in the intervention arm had a significantly greater increase in knowledge and decrease in attitudinal barriers compared with patients in the control arm (P < .001).71 All patients had a significant increase in their preparedness to consider participation in clinical trials (control arm: mean [SD] = 3.4 [13.5]; intervention arm: mean [SD] = 4.7 [12.8]; P < .001).70

Another intervention specifically addressed the negative perceptions and attitudes of patients about clinical trials by assessing the effectiveness of a multimedia, psychoeducational intervention compared with printed educational materials.71 The intervention was designed to improve patient attitudes and knowledge of clinical trials, their ability to effectively make decisions, their receptivity to receiving more information, and their willingness to participate in clinical trials.71 The researchers observed that study participants who received the intervention had more positive attitudes toward clinical trials (mean [SD] = 0.21 [0.01]; P = .02), and, although the 2 interventions were not developed and tested with minority patients, the study results showed no significant difference between intervention by patient demographics.71 Thus, the intervention could potentially be adapted to specifically benefit racial and ethnic minority patient populations.

Although racial and ethnic minority patients are overall as likely as white patients to agree to enroll in a clinical trial, reasons for declining may differ by racial and ethnic background.30,59,66–68 Minority patients — particularly African Americans — may hold negative race-related attitudes and beliefs that could directly and indirectly influence interactions with their health care professional regarding trials and decisions about enrollment.38,40,66,72 These attitudes, which have been derived in large part from issues of racism, uninformed consent, and poor health care for minorities in the United States, include greater mistrust in medical institutions and health care professionals and a greater sense of having been the target of discrimination.20,23,29,38,69,72–78 A systematic review of the research assessing the multiple barriers to minority enrollment in clinical trials found that mistrust in research and the medical system was the most common barrier to patients’ willingness to participate in a clinical trial.29

The attitudes of African American patients toward medical research were assessed using focus groups of African American adult patients from a single urban public hospital.72 Results showed that most were in favor of medical research as long as they were not treated as “guinea pigs.”72 The authors also reported that many of the participants had a limited understanding of the informed consent process, and many patients assumed the consent form was protecting hospitals and doctors from any legal responsibility, not to protect patients.72 Another study that assessed and compared the racial differences in factors that influence patient willingness to enroll in clinical research studies found that African Americans were less willing to participate in medical research if they attributed a high importance to the race of the physician when seeking routine medical care and believed that minorities bear most of the risks of medical research.40

Interventions designed to increase the recruitment of minorities in clinical trials are generally focused on communities, rather than on individuals.32,79 One such intervention targeted minority recruitment using strategic planning, which included meetings and conferences with key stakeholders and minority organizations as a means to increase minority enrollment.79 The authors examined institutions that employed these strategies and those that did not, and they found a significant increase in the rate of minority accrual in institutions that implemented strategic planning compared with those that did not.79 This effort suggests that the mistrust of the medical system seen among minority patients might be addressed with culturally sensitive and open community engagement.

Other identified patient-level barriers to the enrollment of racial and ethnic minorities in clinical trials include lack of transportation, inadequate insurance, lack of childcare, and poor access to health care.42,66 The NRG Oncology workshop also identified direct-to-patient communication and advertising as critical for the future of minority enrollment in clinical trials, emphasizing that this should be done with collaboration with key stakeholders such as community groups, survivor advocacy groups, and religious institutios.44 The intersection between the impact of patient attitudes and access to trial participation illustrates the complex and multilevel nature of this issue and the need for more comprehensive interventional strategies.

Interpersonal-Level Barriers

Our model suggests that system- and individual-level barriers to minority enrollment in clinical trials affect whether and how trials are discussed during doctor–patient clinical interactions. This suggestion is based on our work and that of others showing that patient and physician attitudes affect the quality of communication during clinical interactions with African Americans.80–88 Our model also partly explains why communication during these interactions is often of a lower quality and may affect racial and ethnic minorities’ decisions about enrollment.

For example, implicit bias among health care professionals (eg, oncologists) negatively affects communication with minority patients.89 An investigation of the impact of the implicit racial bias of oncologists on their clinical interactions with African Americans with cancer revealed that oncologists with higher rates of implicit bias against African Americans had shorter interactions with African Americans than oncologists with lower levels of implicit bias.90 In addition, oncologists with higher rates of implicit bias used less patient-centered communication.90 Although this study was not specifically focused on clinical trials, the findings suggest that implicit bias among health care professionals may affect clinical interactions with African Americans who are eligible or express interest in participating in a clinical trial.90

Racial and ethnic differences in the quality of communication are due to both patient-related communication behaviors (eg, African Americans often ask fewer questions),82,86 general communication behaviors among physicians, including amount of patient centeredness, information giving, and shared decision-making, 61,81,86,91 and communication specific to discussing trials.45,63,92–95 Although few researchers have specifically focused on discussions with minority patients about enrolling in cancer trials, a single study of video-recorded interactions was undertaken in which oncologists discussed clinical trials with whites and African Americans.96 Using linguistic analyses, the interactions with African Americans compared with whites were found to be shorter, the topic of clinical trials was less frequently mentioned, and, when clinical trials were mentioned, less time was spent discussing them.96 Compared with whites, differences were observed in the discussion of some of the key aspects of clinical trials: Oncologists and African American patients spent less time discussing the purpose of the trial, its risks and benefits, and alternatives to participating in the trial; however, they spent more time discussing the voluntary nature of trials.96 These findings are particularly problematic because very few oncologists are African American, and so racially discordant interactions may be considered the norm for African American patients with cancer.96,97

Few patient-focused interventions designed to improve doctor–patient discussions of clinical trials exist, and none of them focus on minority patient populations.98 One study assessed an intervention designed to improve patient understanding of early-phase clinical trials for which they were eligible and which would be discussed during a subsequent oncology visit.99 Prior to the visit with the oncologist to discuss the trial, study participants in the intervention group viewed an interactive, computer-based presentation about clinical trials that included information about several aspects of clinical trials and urged them to discuss the risks and benefits of the trial with their oncologist; those assigned to the control group were provided a pamphlet that covered similar topics.99 Following the clinic visit, participants assigned to the intervention were more likely than the controls to understand that the purpose of an early-phase trial was related to the safety and dosing of the drug; however, the majority of participants in both groups reported that the main purpose of an early-phase trial was “to see if the drug works.” 99 In addition, those in the intervention group were also more likely than the control group to believe that the physician talked to them about joining an early-phase trial because they might benefit from the drug compared with controls. Brown et al100 developed and pilot tested another patient-focused intervention that provided eligible patients with a booklet with trial-related questions they could ask their oncologist during the clinic visit. Findings suggested that the study patients had high informational needs prior to the visit, selected most of the questions to ask their oncologist, and asked many of the questions during the visit.100 Although these interventions were not tested in populations with minority patients, they could potentially be adapted for specific populations.

The clinical interaction is based on a relationship, so focus on the social interaction between patients and physicians from differing social backgrounds may be valuable. Research from the field of social psychology suggests that patients and physicians in racially discordant clinical interactions should create a sense of common purpose, support, and understanding as ways to reduce bias and increase cooperation and trust.101,102 This approach formed the basis of a “team” intervention in a primary care clinic that succeeded in increasing patient trust and adherence following such clinic visits.103 Thus, this type of approach may reduce the impact of racial bias in interactions when clinical trials could be discussed.

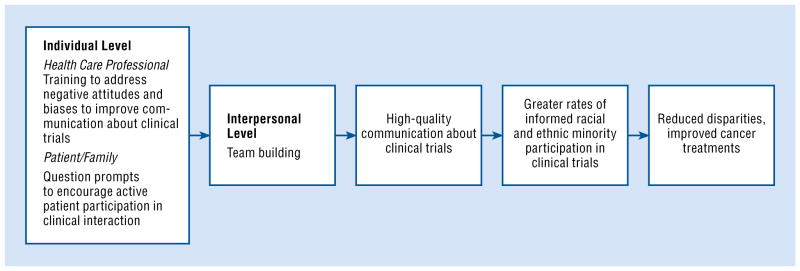

Proposed Multilevel Interventional Model

Our multilevel model and supporting research identify and describe factors that may inhibit the enrollment of minorities in clinical trials. Authors have challenged researchers to move beyond reductionist, single-level interventions.25,26,104 We have met this challenge by proposing a multilevel intervention comprised of evidence-based strategies focused at the patient, oncologist, and patient–oncologist interpersonal levels. Although the proposed intervention does not directly address the system level, addressing these other 2 levels may, in combination, have a greater and longer-lasting impact on increasing enrollment among minority patients (Fig 2). Ideally, an intervention should address all levels; however, in reality, it may be difficult for all interventions to address all of them.

Fig 2.

Our proposed model for a system-level intervention.

Our proposed intervention builds on previously published descriptive and interventional research on individual attitudes and clinical communication by addressing these 3 levels of barriers. The intervention places emphasis on the communication about clinical trials that occurs between patients and physicians in clinical settings. We place the focus on clinical communication for 3 reasons:

The quality of doctor–patient communication during clinic visits is considered the most central and proximal influence on a patient’s decision to participate in a clinical trial.

Health care is transacted through these interpersonal processes among health care organizations, health care professionals, and patients and their families.105–107

The quality of communication during clinical interactions with minority patients is less than that seen among similar interactions with whites.80–88

However, even multilevel interventions will have limited success if they occur in a vacuum; in other words, they must be implemented within institutions with the appropriate infrastructure to support trials that match the clinical characteristics of an engaged, diverse patient population.

Our proposed multilevel intervention illustrates some potential ways to influence the attitudes and communication skills of minorities related to engaging in discussion about clinical trials with oncologists; the attitudes and communication skills of oncologists when discussing trials with minority patients; and doctor–patient interactions in which trials may be discussed.

The first aspect of the intervention is a patient-focused communication intervention called a question-prompt list. A question-prompt list is a list of questions related to the physical and psychosocial aspects of a medical condition that patients may wish to ask their physician during a medical visit. Question-prompt lists are designed as a simple, inexpensive way to support patients in gaining information about their diagnosis and treatment and improve doctor–patient communication by encouraging patients to actively participate in their health care (eg, ask questions, state concerns).108–111 Active participation has been shown to influence the amount of information physicians provide, treatments they recommend, topics discussed, and patient psychosocial and physical health outcomes.112–116 Question-prompt lists have been developed and tested in several medical settings, and, given the research showing that racially discordant interactions are often characterized by poor-quality communication, it is surprising that this type of intervention has not been tested in this context.98,100,117,118 We have collaborated with community members, African American patients and their families, and oncologists to develop a question-prompt list for use in the context of racially discordant oncology treatment interactions.119 Preliminary findings from a randomized trial of the question-prompt list show that its use was feasible and acceptable in this patient population, and it was successful in improving their level of active participation.120

For the purpose of a multilevel intervention relevant to minority enrollment in clinical trials, we suggest adapting a question-prompt list developed for use in the context of clinical trials, although it has never been tested among minority patients.100 This question-prompt list includes 33 questions divided into 11 categories (eg, finding out more about the trial, understanding the trial’s purpose and background, understanding possible risks). Adapting the question-prompt list for use in a diverse population of patients will require engaging community members and patients to ensure that it reflects findings from focus groups and other research with individuals representative of the patients likely to be the recipients of the intervention.121

The second aspect of the intervention is intended to enhance the patient-focused intervention by improving physician attitudes and communication skills related to discussing trials with minority patients. The physician-focused intervention would include 2 components, one focused on communication skills and the other focused on trial-related attitudes. The communication component would build on prior work on training physicians to improve physician communication skills related to discussing trials but would also involve increasing physician knowledge about the fact that most patients, including racial and ethnic minority groups, are willing to participate in trials if their physician offers a trial and does so using high-quality, patient-centered communication.45,63,67,92,122

In clinical communication, participants exchange both informational and relational messages, and the training intervention would involve skill-building in both.92 Skill-building in informational communication would include guidelines for discussing information patients need to make an informed decision about participating in a trial based on international guidelines.123,124 Skill-building in relational communication would include explanations and illustrations of communication strategies such as using organizing statements, eliciting questions and concerns by utilizing strategies such as the ask–tell–ask method, using plain language rather than technical jargon, assessing understanding by using the teach-back method, directly acknowledging and empathically responding to questions and concerns, and using shared–decision-making principles.125–127

The attitudinal component of the physician-focused intervention would occur following the communication component. This aspect of the intervention would be designed to increase the likelihood that physicians will discuss and offer trials to their minority patients. Asking people to think about their attitudes affects both their attitudes and relevant behavior, and asking people to form a situation-specific plan for a type of behavior, such as discussing a trial with a patient, increases the likelihood they will engage in the behavior.128–130 Our proposed intervention translates that research into an intervention in which physicians are provided with a brief e-mail message prior to a visit with a patient potentially eligible for a trial. In the message, physicians would be asked to rate the scientific and clinical benefits of offering a trial to minority patients and to consider exactly how they will discuss the trial with the patient.

The interpersonal aspect, which is the third aspect of the intervention, involves both patients and physicians. It is based on research that suggests the encouragement of patients and physicians to create a sense of common purpose, support, and understanding may assist in reducing bias and increasing cooperation and trust.101,102 Based on this research, members of our research group tested a team intervention in a primary care clinic that successfully increased patient trust and adherence following racially discordant clinic visits.103 A similar team intervention could be provided to physicians who have the ability to offer trials to a diverse population of patients as well as their patients who are potentially eligible for an ongoing trial. Patients and oncologists would receive simple instructions about working together as a team to achieve a common goal — providing high-quality care to treat cancer — and they would be provided with team items, such as pens and buttons, with a team logo. This type of intervention may overcome — or reduce — some of the effects of patient mistrust of physicians and researchers, physician implicit bias toward minorities, and concerns about harming the therapeutic relationship with these patients.

Conclusions

Although racial and ethnic disparities in cancer and other conditions have been documented for decades, researchers, health care professionals, and policymakers have been unable to eliminate these persistent and preventable contributors to poor health.17,23 Underenrollment of racial and ethnic minority populations in clinical trials is a health care disparity that results from preventable and interlinked policies, practices, and barriers at the system, individual, and interpersonal levels.23 Although many interventions designed to increase the clinical trial enrollment of racial and ethnic minorities and other under-represented groups have experienced varying levels of success, multilevel interventions are likely to be the most effective method for increasing enrollment among a well-informed, diverse population of patients.25 When members of these groups decide to enroll in a clinical trial based on a supportive and efficient system-level environment and high-quality communication with their health care professionals, medical researchers will be able to move toward their goal of translating new knowledge into tangible benefits and providing high-quality cancer care for all patients.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded in part by National Institutes of Health/National Cancer Institute grant no. R01CA200718-01.

Footnotes

No significant relationships exist between the authors and the companies/organizations whose products or services may be referenced in this article.

References

- 1.Newman LA, Roff NK, Weinberg AD. Cancer clinical trials accrual: missed opportunities to address disparities and missed opportunities to improve outcomes for all. Ann Surg Oncol. 2008;15(7):1818–1819. doi: 10.1245/s10434-008-9869-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Committee on Cancer Clinical Trials; NCI Cooperative Group Program; Institute of Medicine. Mendelsohn. In: Nass SJ, Moses HL, editors. A National Cancer Clinical Trials System for the 21st Century: Reinvigorating the NCI Cooperative Group Program. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Murthy VH, Krumholz HM, Gross CP. Participation in cancer clinical trials: race-, sex-, and age-based disparities. JAMA. 2004;291(22):2720–2726. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.22.2720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stewart JH, Bertoni AG, Staten JL, et al. Participation in surgical oncology clinical trials: gender-, race/ethnicity-, and age-based disparities. Ann Surg Oncol. 2007;14(12):3328–3334. doi: 10.1245/s10434-007-9500-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cheng SK, Dietrich MS, Dilts DM. A sense of urgency: evaluating the link between clinical trial development time and the accrual performance of cancer therapy evaluation program (NCI-CTEP) sponsored studies. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16(22):5557–5563. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-0133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Korn EL, Freidlin B, Mooney M, et al. Accrual experience of National Cancer Institute Cooperative Group phase III trials activated from 2000 to 2007. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(35):5197–5201. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.31.5382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Penner LA, Manning M, Eggly S, et al. Prosocial behavior in cancer research: patient participation in cancer clinical trials. In: Graziano B, Schroeder D, editors. Handbook of Prosocial Behavior. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Minasian LM, Carpenter WR, Weiner BJ, et al. Translating research into evidence-based practice: the National Cancer Institute Community Clinical Oncology Program. Cancer. 2010;116(19):4440–4449. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Du W, Gadgeel SM, Simon MS. Predictors of enrollment in lung cancer clinical trials. Cancer. 2006;106(2):420–425. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Al-Refaie WB, Vickers SM, Zhong W, et al. Cancer trials versus the real world in the United States. Ann Surg. 2011;254(3):438–442. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31822a7047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Freedman LS, Simon R, Foulkes MA, et al. Inclusion of women and minorities in clinical trials and the NIH Revitalization Act of 1993—the perspective of NIH clinical trialists. Control Clin Trials. 1995;16(5):277–285. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(95)00048-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kwiatkowski K, Coe K, Bailar JC, et al. Inclusion of minorities and women in cancer clinical trials, a decade later: have we improved? Cancer. 2013;119(16):2956–2963. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Unger JM, Hershman DL, Albain KS, et al. Patient income level and cancer clinical trial participation. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(5):536–542. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.45.4553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Baquet CR, Commiskey P, Daniel Mullins C, et al. Recruitment and participation in clinical trials: socio-demographic, rural/urban, and health care access predictors. Cancer Detect Prev. 2006;30(1):24–33. doi: 10.1016/j.cdp.2005.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Paskett ED, Cooper MR, Stark N, et al. Clinical trial enrollment of rural patients with cancer. Cancer Pract. 2002;10(1):28–35. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-5394.2002.101006.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vanderpool RC, Kornfeld J, Mills L, et al. Rural-urban differences in discussions of cancer treatment clinical trials. Patient Educ Couns. 2011;85(2):e69–e74. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2011.01.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Siegel R, Ward E, Brawley O, et al. Cancer statistics, 2011: the impact of eliminating socio-economic and racial disparities on premature cancer deaths. CA Cancer J Clin. 2011;61(4):212–236. doi: 10.3322/caac.20121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.American Cancer Society. Cancer Facts & Figures 2016. Atlanta, GA: American Cancer Society; [Accessed September 13, 2016]. http://www.cancer.org/acs/groups/content/@research/documents/document/acspc-047079.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 19.American Cancer Society. Cancer Facts & Figures for African Americans 2016–2018. Atlanta, GA: American Cancer Society; [Accessed September 13, 2016]. http://www.cancer.org/acs/groups/content/@editorial/documents/document/acspc-047403.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Banda DR, StGermain D, McCaskill-Stevens W, et al. A critical review of the enrollment of black patients in cancer clinical trials. ASCO Org. 2012:153–157. doi: 10.14694/EdBook_AM.2012.32.88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Carpenter WR, Tyree S, Wu Y, et al. A surveillance system for monitoring, public reporting, and improving minority access to cancer clinical trials. Clin Trials. 2012;9(4):426–435. doi: 10.1177/1740774512449531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Unger JM, Gralow JR, Albain KS, et al. Patient income level and cancer clinical trial participation: a prospective survey study. JAMA Oncol. 2016;2(1):137–139. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2015.3924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Smedley BD, Stith AY, Nelson AR, editors. Committee on Understanding and Eliminating Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care; Board on Health Sciences Policy; Institute of Medicine. Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2003. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bolen S, Tilburt J, Baffi C, et al. Defining “success” in recruitment of underrepresented populations to cancer clinical trials: moving toward a more consistent approach. Cancer. 2006;106(6):1197–1204. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Taplin SH, Anhang Price R, Edwards HM, et al. Understanding and influencing multilevel factors across the cancer care continuum. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 2012;2012(44):2–10. doi: 10.1093/jncimonographs/lgs008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Clauser SB, Taplin SH, Foster MK, et al. Multilevel intervention research: lessons learned and pathways forward. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 2012;2012(44):127–133. doi: 10.1093/jncimonographs/lgs019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kozlowski SWJ, Klein KJ. A multilevel approach to theory and research in organizations: contextual, temporal, and emergent processes. In: Klein KJ, Koszlowski SWJ, editors. Multilevel Theory, Research, and Methods in Organizations: Foundations, Extensions, and New Directions. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Diehl KM, Green EM, Weinberg A, et al. Features associated with successful recruitment of diverse patients onto cancer clinical trials: report from the American College of Surgeons Oncology Group. Ann Surg Oncol. 2011;18(13):3544–3550. doi: 10.1245/s10434-011-1818-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ford JG, Howerton MW, Lai GY, et al. Barriers to recruiting underrepresented populations to cancer clinical trials: a systematic review. Cancer. 2008;112(2):228–242. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Langford AT, Resnicow K, Dimond EP, et al. Racial/ethnic differences in clinical trial enrollment, refusal rates, ineligibility, and reasons for decline among patients at sites in the National Cancer Institute’s Community Cancer Centers Program. Cancer. 2014;120(6):877–884. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bruner DW, Jones M, Buchanan D, et al. Reducing cancer disparities for minorities: a multidisciplinary research agenda to improve patient access to health systems, clinical trials, and effective cancer therapy. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(14):2209–2215. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.04.8116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McCaskill-Stevens W, McKinney MM, Whitman CG, et al. Increasing minority participation in cancer clinical trials: the minority-based community clinical oncology program experience. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(22):5247–5254. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.22.236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Somkin CP, Altschuler A, Ackerson L, et al. Organizational barriers to physician participation in cancer clinical trials. Am J Manag Care. 2005;11(7):413–421. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wong YN, Schluchter MD, Albrecht TL, et al. Financial concerns about participation in clinical trials among patients with cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(5):479–487. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.63.2463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sateren WB, Trimble EL, Abrams J, et al. How socio-demographics, presence of oncology specialists, and hospital cancer programs affect accrual to cancer treatment trials. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20(8):2109–2117. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.08.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Farmer DF, Jackson SA, Camacho F, et al. Attitudes of African American and low socio-economic status white women toward medical research. Health Care Poor Underserved. 2007;18(1):85–99. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2007.0008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Paskett ED, Reeves KW, McLaughlin JM, et al. Recruitment of minority and underserved populations in the United States: the Centers for Population Health and Health Disparities experience. Contemp Clin Trials. 2008;29(6):847–861. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2008.07.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Skloot R. The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks. New York: Broadway Books; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Katz RV, Kegeles SS, Kressin NR, et al. Awareness of the Tuskegee syphilis study and the US presidential apology and their influence on minority participation in biomedical research. Am J Public Health. 2008;98(6):1137–1142. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.100131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shavers VL, Lynch CF, Burmeister LF. Racial differences in factors that influence the willingness to participate in medical research studies. Ann Epidemiol. 2002;12(4):248–256. doi: 10.1016/s1047-2797(01)00265-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Weiner BJ, Jacobs SR, Minasian LM, et al. Organizational designs for achieving high treatment trial enrollment: a fuzzy set analysis of the Community Clinical Oncology Program. J Oncol Pract. 2012;8(5):287–291. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2011.000507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wujcik D, Wolff SN. Recruitment of African Americans to national oncology clinical trials through a clinical trial shared resource. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2010;21(1 suppl):38–50. doi: 10.1353/hpu.0.0251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.McCaskill-Stevens W, Lyss AP, Good M, et al. The NCI Community Oncology Research Program: what every clinician needs to know. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book. 2013 doi: 10.14694/EdBook_AM.2013.33.e84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Brooks SE, Muller CY, Robinson W, et al. Increasing minority enrollment onto clinical trials: practical strategies and challenges emerge from the NRG Oncology Accrual Workshop. J Oncol Pract. 2015;11(6):486–490. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2015.005934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Brown R, Albrecht TL. Enrollment in clinical trials. In: Kissane D, Bultz BD, Butow PN, et al., editors. Handbook of Communication in Oncology and Palliative Care. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Howerton MW, Gibbons MC, Baffi CR, et al. Provider roles in the recruitment of underrepresented populations to cancer clinical trials. Cancer. 2007;109(3):465–476. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Henderson GE, Churchill LR, Davis AM, et al. Clinical trials and medical care: defining the therapeutic misconception. PLoS Med. 2007;4(11):e324. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0040324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pinto HA, McCaskill-Stevens W, Wolfe P, et al. Physician perspectives on increasing minorities in cancer clinical trials: an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) initiative. Ann Epidemiol. 2000;10(8 suppl):S78–S84. doi: 10.1016/s1047-2797(00)00191-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hagiwara N, Penner LA, Gonzalez R, et al. Racial attitudes, physician-patient talk time ratio, and adherence in racially discordant medical interactions. Soc Sci Med. 2013;87:123–131. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.03.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cooper LA, Roter DL, Carson KA, et al. The associations of clinicians’ implicit attitudes about race with medical visit communication and patient ratings of interpersonal care. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(5):979–987. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Blair IV, Steiner JF, Fairclough DL, et al. Clinicians’ implicit ethnic/racial bias and perceptions of care among black and Latino patients. Ann Fam Med. 2013;11(1):43–52. doi: 10.1370/afm.1442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Penner LA, Dovidio JF, West TV, et al. Aversive racism and medical interactions with Black patients: a field study. J Exp Soc Psychol. 2010;46(2):436–440. doi: 10.1016/j.jesp.2009.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.van Ryn M, Burgess D, Malat J, et al. Physicians’ perceptions of patients’ social and behavioral characteristics and race disparities in treatment recommendations for men with coronary artery disease. Am J Public Health. 2006;96(2):351–357. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.041806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Moskowitz D, Thom DH, Guzman D, et al. Is primary care providers’ trust in socially marginalized patients affected by race? J Gen Intern Med. 2011;26(8):846–851. doi: 10.1007/s11606-011-1672-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Moskowitz GB, Stone J, Childs A. Implicit stereotyping and medical decisions: unconscious stereotype activation in practitioners’ thoughts about African Americans. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(5):996–1001. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sabin JA, Greenwald AG. The influence of implicit bias on treatment recommendations for 4 common pediatric conditions: pain, urinary tract infection, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, and asthma. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(5):988–995. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sabin JA, Rivara FP, Greenwald AG. Physician implicit attitudes and stereotypes about race and quality of medical care. Med Care. 2008;46(7):678–685. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181653d58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Joseph G, Dohan D. Diversity of participants in clinical trials in an academic medical center: the role of the ‘Good Study Patient?’. Cancer. 2009;115(3):608–615. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Simon MS, Du W, Flaherty L, et al. Factors associated with breast cancer clinical trials participation and enrollment at a large academic medical center. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22(11):2046–2052. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Penner LA, Blair IV, Albrecht TL, et al. Reducing racial health care disparities: a social psychological analysis. Policy Insights Behav Brain Sci. 2014;1:204–212. doi: 10.1177/2372732214548430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Epstein RM, Street RL., Jr . Patient-Centered Communication in Cancer Care: Promoting Healing and Reducing Suffering. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute; 2007. NIH publication no. 07–6225. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kissane DW, Bylund CL, Banerjee SC, et al. Communication skills training for oncology professionals. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(11):1242–1247. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.39.6184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Brown RF, Butow PN, Boyle F, et al. Seeking informed consent to cancer clinical trials: evaluating the efficacy of doctor communication skills training. Psychooncology. 2007;16(6):507–516. doi: 10.1002/pon.1095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Gross CP, Herrin J, Wong N, et al. Enrolling older persons in cancer trials: the effect of socio-demographic, protocol, and recruitment center characteristics. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(21):4755–4763. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.14.365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Manne S, Kashy D, Albrecht T, et al. Attitudinal barriers to participation in oncology clinical trials: factor analysis and correlates of barriers. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl) 2015;24(1):28–38. doi: 10.1111/ecc.12180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Rivers D, August EM, Sehovic I, et al. A systematic review of the factors influencing African Americans’ participation in cancer clinical trials. Contemp Clin Trials. 2013;35(2):13–32. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2013.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Wendler D, Kington R, Madans J, et al. Are racial and ethnic minorities less willing to participate in health research? PLoS Med. 2006;3(2):e19. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Svensson K, Ramirez OF, Peres F, et al. Socio-economic determinants associated with willingness to participate in medical research among a diverse population. Contemp Clin Trials. 2012;33(6):1197–1205. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2012.07.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Katz RV, Kegeles SS, Kressin NR, et al. The Tuskegee Legacy Project: willingness of minorities to participate in biomedical research. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2006;17(4):698–715. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2006.0126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Meropol NJ, Wong YN, Albrecht T, et al. Randomized trial of a web-based intervention to address barriers to clinical trials. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(5):469–478. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.63.2257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Jacobsen PB, Wells KJ, Meade CD, et al. Effects of a brief multimedia psychoeducational intervention on the attitudes and interest of patients with cancer regarding clinical trial participation: a multicenter randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(20):2516–2521. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.39.5186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Corbie-Smith G, Thomas SB, Williams MV, et al. Attitudes and beliefs of African Americans toward participation in medical research. J Gen Intern Med. 1999;14(9):537–546. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.1999.07048.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Scharff DP, Mathews KJ, Jackson P, et al. More than Tuskegee: understanding mistrust about research participation. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2010;21(3):879–897. doi: 10.1353/hpu.0.0323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Dovidio JF, Penner LA, Albrecht TL, et al. Disparities and distrust: the implications of psychological processes for understanding racial disparities in health and health care. Soc Sci Med. 2008;67(3):478–486. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Penner LA, Dovidio JF, Edmondson D, et al. The experience of discrimination and black-white health disparities in medical care. J Black Psychol. 2009;35(2):180–203. doi: 10.1177/0095798409333585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Halbert CH, Armstrong K, Gandy OH, Jr, et al. Racial differences in trust in health care providers. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(8):896–901. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.8.896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Halbert CH, Weathers B, Delmoor E, et al. Racial differences in medical mistrust among men diagnosed with prostate cancer. Cancer. 2009;115(11):2553–2561. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Boulware L, Cooper L, Ratner L, et al. Race and trust in the health care system. Public Health Reports. 2003;118:358–365. doi: 10.1016/S0033-3549(04)50262-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Duda C, Mahon I, Chen MH, et al. Impact and costs of targeted recruitment of minorities to the National Lung Screening Trial. Clin Trials. 2011;8(2):214–223. doi: 10.1177/1740774510396742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Jean-Pierre P, Fiscella K, Griggs J, et al. Race/ethnicity-based concerns over understanding cancer diagnosis and treatment plan. J Natl Med Assoc. 2010;102(3):184–189. doi: 10.1016/s0027-9684(15)30524-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Street RL, Jr, Gordon H, Haidet P. Physicians’ communication and perceptions of patients: is it how they look, how they talk, or is it just the doctor? Soc Sci Med. 2007;65(3):586–598. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.03.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Eggly S, Harper FW, Penner LA, et al. Variation in question asking during cancer clinical interactions: a potential source of disparities in access to information. Patient Educ Couns. 2011;82(1):63–68. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2010.04.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Cooper LA, Roter DL, Johnson RL, et al. Patient-centered communication, ratings of care, and concordance of patient and physician race. Ann Intern Med. 2003;139(11):907–915. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-139-11-200312020-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Johnson RL, Roter D, Powe NR, et al. Patient race/ethnicity and quality of patient-physician communication during medical visits. Am J Public Health. 2004;94(12):2084–2090. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.12.2084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Gordon HS, Street RL, Jr, Sharf BF, et al. Racial differences in trust and lung cancer patients’ perceptions of physician communication. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(6):904–909. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.03.1955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Gordon HS, Street RL, Jr, Sharf BF, et al. Racial differences in doctors’ information-giving and patients’ participation. Cancer. 2006;107(6):1313–1320. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Siminoff LA, Graham GC, Gordon NH. Cancer communication patterns and the influence of patient characteristics: disparities in information-giving and affective behaviors. Patient Educ Couns. 2006;62(3):355–360. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2006.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Song L, Hamilton JB, Moore AD. Patient-healthcare provider communication: perspectives of African American cancer patients. Health Psychol. 2012;31(5):539–547. doi: 10.1037/a0025334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Sabin J, Nosek BA, Greenwald A, et al. Physicians’ implicit and explicit attitudes about race by MD race, ethnicity, and gender. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2009;20(3):896–913. doi: 10.1353/hpu.0.0185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Penner LA, Dovidio JF, Gonzalez R, et al. The effects of oncologist implicit racial bias in racially discordant oncology interactions. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(24):2874–2880. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.66.3658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Janz NK, Wren PA, Copeland LA, et al. Patient-physician concordance: preferences, perceptions, and factors influencing the breast cancer surgical decision. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22(15):3091–3098. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.09.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Albrecht TL, Eggly SS, Gleason ME, et al. Influence of clinical communication on patients’ decision making on participation in clinical trials. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(16):2666–2673. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.14.8114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Eggly S, Albrecht TL, Harper FW, et al. Oncologists’ recommendations of clinical trial participation to patients. Patient Educ Couns. 2008;70(1):143–148. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2007.09.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Barton E, Eggly S. Ethical or unethical persuasion? The rhetoric of offers to participate in clinical trials. Writ Commun. 2009;26(3):295–319. [Google Scholar]

- 95.Kass N, Taylor H, Fogarty L, et al. Purpose and benefits of early phase cancer trials: what do oncologists say? What do patients hear? J Empir Res Hum Res Ethics. 2008;3(3):57–68. doi: 10.1525/jer.2008.3.3.57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Eggly S, Barton E, Winckles A, et al. A disparity of words: racial differences in oncologist-patient communication about clinical trials. Health Expect. 2015;18(5):1316–1326. doi: 10.1111/hex.12108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Hamel LM, Chapman R, Malloy M, et al. Critical shortage of African American medical oncologists in the United States. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(32):3697–3700. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.59.2493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Street RL, Jr, Slee C, Kalauokalani DK, et al. Improving physician-patient communication about cancer pain with a tailored education-coaching intervention. Patient Educ Couns. 2010;80(1):42–47. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2009.10.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Kass NE, Sugarman J, Medley AM, et al. An intervention to improve cancer patients’ understanding of early-phase clinical trials. IRB. 2009;31(3):1–10. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Brown RF, Bylund CL, Li Y, et al. Testing the utility of a cancer clinical trial specific question prompt list (QPL-CT) during oncology consultations. Patient Educ Couns. 2012;88(2):311–317. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2012.02.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Gaertner S, Dovidio JF. A common ingroup identity: a categorization-based approach for reducing intergroup bias. In: Nelson TD, editor. Handbook of Prejudice, Stereotyping, and Discrimination. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 102.Gaertner S, Dovidio JF, Houlette M. Social categorization. In: Dovidio JF, Hewstone M, Glick P, editors. Handbook of Prejudice, Stereotyping, and Discrimination. London: Sage; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 103.Penner LA, Gaertner S, Dovidio JF, et al. A social psychological approach to improving the outcomes of racially discordant medical interactions. J Gen Intern Med. 2013;28(9):1143–1149. doi: 10.1007/s11606-013-2339-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Stange KC, Breslau ES, Dietrich AJ, et al. State-of-the-art and future directions in multilevel interventions across the cancer control continuum. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr. 2012;2012(44):20–31. doi: 10.1093/jncimonographs/lgs006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Albrecht TL, Penner LA, Cline RJ, et al. Studying the process of clinical communication: issues of context, concepts, and research directions. J Health Commun. 2009;14(suppl 1):47–56. doi: 10.1080/10810730902806794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.McCormack LA, Treiman K, Rupert D, et al. Measuring patient-centered communication in cancer care: a literature review and the development of a systematic approach. Soc Sci Med. 2011;72(7):1085–1095. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Epstein RM, Street RL., Jr . Patient-Centered Communication in Cancer Care: Promoting Healing and Reducing Suffering. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute; US Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health; 2007. NIH publication no. 07-6225. [Google Scholar]

- 108.Sansoni JE, Grootemaat P, Duncan C. Question Prompt Lists in health consultations: a review. Patient Educ Couns. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2015.05.015. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Brandes K, Linn AJ, Butow PN, et al. The characteristics and effectiveness of question prompt list interventions in oncology: a systematic review of the literature. Psychooncology. 2015;24(3):245–252. doi: 10.1002/pon.3637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Dimoska A, Tattersall MH, Butow PN, et al. Can a “prompt list” empower cancer patients to ask relevant questions? Cancer. 2008;113(2):225–237. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Henselmans I, de Haes HC, Smets EM. Enhancing patient participation in oncology consultations: a best evidence synthesis of patient-targeted interventions. Psychooncology. 2013;22(5):961–977. doi: 10.1002/pon.3099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Dimoska A, Butow PN, Dent E, et al. An examination of the initial cancer consultation of medical and radiation oncologists using the Cancode interaction analysis system. Br J Cancer. 2008;98(9):1508–1514. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Cegala DJ, Street RL, Jr, Clinch CR. The impact of patient participation on physicians’ information provision during a primary care medical interview. Health Commun. 2007;21(2):177–185. doi: 10.1080/10410230701307824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Street RL, Jr, Tancredi DJ, Slee C, et al. A pathway linking patient participation in cancer consultations to pain control. Psychooncology. 2014;23(10):1111–1117. doi: 10.1002/pon.3518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Clayton JM, Butow PN, Tattersall MH, et al. Randomized controlled trial of a prompt list to help advanced cancer patients and their caregivers to ask questions about prognosis and end-of-life care. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(6):715–723. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.7827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Greene J, Hibbard JH. Why does patient activation matter? An examination of the relationships between patient activation and health-related outcomes. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27(5):520–526. doi: 10.1007/s11606-011-1931-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Clayton J, Butow P, Tattersall M, et al. Asking questions can help: development and preliminary evaluation of a question prompt list for palliative care patients. Br J Cancer. 2003;89(11):2069–2077. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6601380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Cegala DJ, Chisolm DJ, Nwomeh BC. A communication skills intervention for parents of pediatric surgery patients. Patient Educ Couns. 2013;93(1):34–39. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2013.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Eggly S, Tkatch R, Penner LA, et al. Development of a question prompt list as a communication intervention to reduce racial disparities in cancer treatment. J Cancer Educ. 2013;28(2):282–289. doi: 10.1007/s13187-013-0456-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Eggly S, Hamel LM, Foster T, et al. Using a question prompt list to increase patient active participation in racially discordant cancer interactions. Presented at: 13th International Conference on Communication in Healthcare; October 25–28, 2015; New Orleans, LA. [Google Scholar]

- 121.Brown RF, Cadet DL, Houlihan RH, et al. Perceptions of participation in a phase I, II, or III clinical trial among African American patients with cancer: what do refusers say? J Oncol Pract. 2013;9(6):287–293. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2013.001039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Bylund CL, Brown R, Gueguen JA, et al. The implementation and assessment of a comprehensive communication skills training curriculum for oncologists. Psychooncology. 2010;19(6):583–593. doi: 10.1002/pon.1585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Wendler D, Grady C. What should research participants understand to understand they are participants in research? Bioethics. 2008;22(4):203–208. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8519.2008.00632.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Council for International Organizations of Medical Sciences (CIOMS); World Health Organization. International Ethical Guidelines for Biomedical Research Involving Human Subjects. Geneva: CIOMS; 2002. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Back AL, Arnold RM, Baile WF, et al. Approaching difficult communication tasks in oncology. CA Cancer J Clin. 2005;55(3):164–177. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.55.3.164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Kemp EC, Floyd MR, McCord-Duncan E, et al. Patients prefer the method of “tell back-collaborative inquiry” to assess understanding of medical information. J Am Board Fam Med. 2008;21(1):24–30. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2008.01.070093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Makoul G, Clayman ML. An integrative model of shared decision making in medical encounters. Patient Educ Couns. 2006;60(3):301–312. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2005.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Young AI, Fazio RH. Attitude accessibility as a determinant of object construal and evaluation. J Exp Soc Psychol. 2013;49(3):404–418. [Google Scholar]

- 129.Gollwitzer P. The volitional benefits of planning. In: Gollwitzer P, Bargh J, editors. The Psychology of Action: Linking Cognition and Motivation to Behaviour. New York: Guilford Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 130.Gollwitzer PM. Implementation intentions: strong effects of simple plans. Am Psychologist. 1999;54(7):493–503. [Google Scholar]