Summary

The clinical course of chronic lymphocytic leukaemia (CLL) is heterogeneous, and treatment options vary considerably. The Connect® CLL registry is a multicentre, prospective observational cohort study that provides a real‐world perspective on the management of, and outcomes for, patients with CLL. Between 2010 and 2014, 1494 patients with CLL and that initiated therapy, were enrolled from 199 centres throughout the USA (179 community‐, 17 academic‐, and 3 government‐based centres). Patients were grouped by line of therapy at enrolment (LOT). We describe the clinical and demographic characteristics of, and practice patterns for, patients with CLL enrolled in this treatment registry, providing patient‐level observational data that represent real‐world experiences in the USA. Fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) analyses were performed on 49·3% of patients at enrolment. The most common genetic abnormalities detected by FISH were del(13q) and trisomy 12 (45·7% and 20·8%, respectively). Differences in disease characteristics and comorbidities were observed between patients enrolled in LOT1 and combined LOT2/≥3 cohorts. Important trends observed include the infrequent use of genetic prognostic testing, and differences in patient characteristics for patients receiving chemoimmunotherapy combinations. These data represent experiences of patients with CLL in the USA, which may inform treatment decisions in everyday practice.

Keywords: chronic lymphocytic leukaemia, practice patterns, patient characteristics, Connect® CLL Registry, chemoimmunotherapy

Chronic lymphocytic leukaemia (CLL) is the most common adult leukaemia in Western countries. Considerable advances have been made in our understanding of the biology of CLL and use of prognostic markers to predict disease progression and therapeutic outcomes. Although diagnostic and prognostic testing is recommended (Hallek et al, 2008; National Comprehensive Cancer Network, 2014; https://www.nccn.org/), interpretation of international guidelines still varies considerably, specifically regarding when to initiate CLL therapy, how to apply prognostic factors when making treatment choices, and the type and sequence of therapeutic regimen offered to patients (Hallek, 2013; Cuneo et al, 2014; Mertens & Stilgenbauer, 2014). Although the results of testing for immunoglobulin heavy chain locus (IGHV) and fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) have been shown to predict survival in patients with CLL (Parikh et al, 2016) they are not recommended to be used to drive treatment initiation decisions (Hallek et al, 2008). However, such testing could guide follow‐up intervals for high‐risk patients (Parikh et al, 2016). CLL is a disease that predominantly affects elderly people, and the management of elderly patients with CLL is more complex than that of younger patients due to a greater frequency of comorbidities (Altekruse et al, 2010; Smith et al, 2011; Siegel et al, 2014). Furthermore, differences in patient outcomes can exist between those treated in clinical trials and those treated in clinical practice: patients in clinical trials may be younger, have fewer comorbidities, more favourable Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Performance Status (ECOG PS), or different racial and/or socioeconomic profiles (Abel, 2011). Therefore, the treatments offered to patients with CLL and the resulting outcomes may vary considerably between institutions, as well as between academic and community settings. As the number of novel agents available for the treatment of CLL expand, these results are particularly relevant in order to foster a more collaborative approach in the diagnosis and treatment of CLL.

The Connect® CLL registry was established to gather information about the experiences of patients undergoing treatment for CLL. To our knowledge, it is the largest prospective disease registry to date, and focuses on the clinical courses of patients being treated for CLL at multiple study centres in the USA. The primary objective of the Registry is to observe the treatment patterns for patients with CLL. Here we describe the clinical and demographic characteristics of patients included in the Connect CLL registry, as well as the treatment patterns of enrolling physicians from community‐, academic‐ and government‐based centres.

Patients and methods

Study design and participants

The Connect CLL registry (NCT01081015) is a multicentre, prospective observational cohort study. A central Institutional Review Board (IRB) (Quorum Review IRB, Seattle, WA, USA) approved the study protocol and was used by 100 centres for site‐specific approval; the remaining centres used their local IRB. Study centres with experience in oncology/haematology trials/registries, access to high‐speed internet, and adequate numbers of patients with CLL were selected; each centre could enrol a maximum of 30 patients. Sites were encouraged to enrol all eligible patients as they presented to their physician.

Patients were required to be aged ≥18 years, provide written informed consent, and have CLL as defined by the International Workshop on Chronic Lymphocytic Leukaemia (IWCLL) guidelines (Hallek et al, 2008). Only patients who initiated a line of therapy (LOT) within 2 months prior to study enrolment were eligible for inclusion. Patients were enrolled into one of three cohorts based on the LOT initiated: ‘LOT1’ (first‐line); ‘LOT2’ (second‐line); and ‘LOT≥3’ (third‐line or above). Each patient was to be followed for up to 5 years or until early discontinuation (i.e., due to death, withdrawal of consent, loss to follow‐up, or study termination). Follow‐up data were to be collected approximately every 3 months during study participation.

The Connect CLL registry is observational, with all interventions and scheduled visits performed solely at the discretion of the treating physician in accordance with their usual care. Participation in the registry is voluntary; patients can withdraw at any time without affecting their subsequent medical care. Patients can receive compensation for completion of the health‐related quality of life (HRQoL) questionnaires ($10 per questionnaire) if reimbursement is approved by their IRB.

Assessments

Information was collected at enrolment via an electronic data capture system, and included demographic information, relevant medical history, laboratory testing, available diagnostic and prognostic testing [i.e., metaphase cytogenetics (MC) and FISH], flow cytometry analyses (CD38 and ZAP70 expression), and HRQoL.

Every 3 months, centre personnel record protocol‐specified, relevant data retrieved from patient medical records. In addition, patients are asked to complete HRQoL instruments at enrolment and every 3 months during follow‐up.

Statistical analysis

Date of enrolment was considered the baseline for this study. Only laboratory samples collected no more than 7 days before the start of enrolment therapy were used for baseline laboratory testing. Medical history and pre‐existing condition data were used to generate a Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) score for use as a prognostic indicator of overall risk of death due to comorbidities and to assess the burden of comorbidities at registry enrolment (Charlson et al, 1987). All data entered as of 25 December 2014 were included in this analysis. Survival data were updated as of 25 August 2015.

Statistical analyses to assess differences in characteristics at enrolment between patient subgroups of interest were conducted using a Chi‐square test for the comparison of rates and a Wilcoxon two‐sample test for the comparison of medians. Logistic regression was used to assess the role of ECOG PS and CCI scores adjusted for LOT and age, and to identify factors predicting MC or FISH testing. Patients with MC or FISH data were compared with those who did not have a result or were not tested. Univariate logistic regression was utilized to screen covariates; those significant at the 0·15 level were evaluated in the multivariate setting. All possible logistic regression models were run and the best fitting model was selected using the score statistic. Missing data were not imputed as per registry protocol. In the statistical analyses, missing data was assumed to be missing at random; sensitivity analyses were conducted where appropriate.

The Kaplan–Meier method was used to estimate overall survival (OS) by LOT and P‐values from the log‐rank test for comparison of survival distributions were provided. OS was defined as the interval between the start of enrolment therapy and the date of death; subjects who did not have a date of death were censored at the last date at which they were known to be alive, at study discontinuation or at the data cut‐off date, whichever was earliest.

All statistical significance was assessed at a 5% level (two‐sided). Statistical analyses of all data were performed using SAS® version 9.2 statistical software (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA).

Results

Patient population

Between March 2010 and January 2014, 1494 patients were enrolled in the Connect CLL Registry, from 199 centres throughout the USA (179 community‐, 17 academic‐ and 3 government‐based centres). Of these, 1311 (87·8%), 155 (10·4%), and 28 (1·9%) patients were enrolled at community‐, academic‐ and government‐based centres, respectively. Of the total population, 889 were in LOT1, 260 were in LOT2 and 345 were in LOT≥3. Patient enrolment in academic versus community centres was balanced across LOT groups. 1449 patients completed the HRQoL questionnaire at enrolment.

Table 1 provides demographics and characteristics of the total population by LOT at study enrolment. The median age of patients was 69 years (range 22–99), with 512 (34·3%) patients aged ≥65 to <75 years and 455 (30·5%) ≥75 years. All patients had a clinical diagnosis of CLL; this diagnosis was confirmed by flow cytometry in 94·9% of patients (i.e., positive for CD5 and ≥1 of CD19, CD20 or CD23).

Table 1.

Patient demographics and characteristics at enrolment to the registry

| LOT1 (n = 889) | LOT2 (n = 260) | LOT≥3 (n = 345) | All patients (N = 1494) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 67·6 (11·0) | 69·9 (11·2) | 69·0 (9·8) | 68·3 (10·8) |

| Median (range) | 68·0 (22–99) | 71·0 (34–96) | 69·0 (34–93) | 69·0 (22–99) |

| Age, n (%) | ||||

| <65 years | 335 (37·7) | 83 (31·9) | 109 (31·6) | 527 (35·3) |

| ≥65 to <75 years | 295 (33·2) | 82 (31·5) | 135 (39·1) | 512 (34·3) |

| ≥75 years | 259 (29·1) | 95 (36·5) | 101 (29·3) | 455 (30·5) |

| Sex, n (%) | ||||

| Male | 566 (63·7) | 171 (65·8) | 216 (62·6) | 953 (63·8) |

| Female | 323 (36·3) | 89 (34·2) | 129 (37·4) | 541 (36·2) |

| Duration of CLL from diagnosis to enrolment, median (range), months | 15 (0–390) | 60 (1–339) | 96 (5–380) | 37 (0–390) |

| Race, n (%) | n = 863 | n = 250 | n = 331 | N = 1444 |

| White | 798 (92·5) | 234 (93·6) | 301 (90·9) | 1333 (92·3) |

| Black | 56 (6·5) | 14 (5·6) | 28 (8·5) | 98 (6·8) |

| Other | 6 (0·7) | 1 (0·4) | 1 (0·3) | 8 (0·6) |

| American Indian/Alaskan native | 0 | 1 (0·4) | 0 | 1 (0·1) |

| Asian | 3 (0·3) | 0 | 1 (0·3) | 4 (0·3) |

| United States geographic region, n (%) | n = 881 | n = 259 | n = 343 | N = 1483 |

| Northeast | 112 (12·7) | 41 (15·8) | 54 (15·7) | 207 (14·0) |

| Midwest | 277 (31·4) | 68 (26·3) | 114 (33·2) | 459 (31·0) |

| South | 352 (40·0) | 113 (43·6) | 126 (36·7) | 591 (39·9) |

| West | 140 (15·9) | 37 (14·3) | 49 (14·3) | 226 (15·2) |

| Institution type, n (%) | ||||

| Academic | 86 (9·7) | 28 (10·8) | 41 (11·9) | 155 (10·4) |

| Community | 787 (88·5) | 227 (87·3) | 297 (86·1) | 1311 (87·8) |

| Government | 16 (1·8) | 5 (1·9) | 7 (2·0) | 28 (1·9) |

| Insurance type, n (%)a | ||||

| Medicare | 512 (57·6) | 170 (65·4) | 232 (67·2) | 914 (61·2) |

| Medicaid | 42 (4·7) | 11 (4·2) | 12 (3·5) | 65 (4·4) |

| Supplemental coverage | 178 (20·0) | 60 (23·1) | 88 (25·5) | 326 (21·8) |

| Private health insurance | 403 (45·3) | 99 (38·1) | 125 (36·2) | 627 (42·0) |

| Health maintenance organization | 104 (11·7) | 31 (11·9) | 38 (11·0) | 173 (11·6) |

| Preferred provider organization | 232 (26·1) | 54 (20·8) | 63 (18·3) | 349 (23·4) |

| Other | 68 (7·6) | 16 (6·2) | 25 (7·2) | 109 (7·3) |

| Military | 15 (1·7) | 3 (1·2) | 8 (2·3) | 26 (1·7) |

| Self‐pay | 13 (1·5) | 3 (1·2) | 3 (0·9) | 19 (1·3) |

| Other insurance | 13 (1·5) | 3 (1·2) | 8 (2·3) | 24 (1·6) |

| Not specified | 20 (2·2) | 13 (5·0) | 8 (2·3) | 41 (2·7) |

| History of CLL in immediate family, n (%) | n = 741 | n = 208 | n = 265 | N = 1214 |

| Yes | 37 (5·0) | 15 (7·2) | 23 (8·7) | 75 (6·2) |

| No | 704 (95·0) | 193 (92·8) | 242 (91·3) | 1139 (93·8) |

CLL, chronic lymphocytic leukaemia; LOT, line of therapy; SD, standard deviation.

Patients can be covered by multiple insurance plans.

Disease characteristics at study enrolment are presented by LOT in Table 2; Table SI shows data by patient age. Rai stage was recorded in 1075 (72%) patients. In patients with recorded symptoms, the most frequent constitutional symptom in all age groups was fatigue. Haematology data stratified by Rai stage at enrolment are shown in Table SII.

Table 2.

Clinical characteristics at enrolment to the registry

| LOT1 (n = 889) | LOT2 (n = 260) | LOT≥3 (n = 345) | All patients (N = 1494) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ECOG PS, n (%) | n = 689 | n = 182 | n = 250 | N = 1121 |

| 0: Fully active | 346 (50·2) | 77 (42·3) | 103 (41·2) | 526 (46·9) |

| 1: Restricted in strenuous activity only | 296 (43·0) | 93 (51·1) | 124 (49·6) | 513 (45·8) |

| 2: Ambulatory, but unable to work | 41 (6·0) | 11 (6·0) | 20 (8·0) | 72 (6·4) |

| 3: Capable of only limited self‐care | 5 (0·7) | 1 (0·5) | 3 (1·2) | 9 (0·8) |

| 4: Completely disabled | 1 (0·1) | 0 | 0 | 1 (0·1) |

| Rai staging system, n (%) | n = 684 | n = 172 | n = 219 | N = 1075 |

| Stage 0 | 172 (25·1) | 53 (30·8) | 56 (25·6) | 281 (26·1) |

| Stage I | 191 (27·9) | 35 (20·3) | 62 (28·3) | 288 (26·8) |

| Stage II | 108 (15·8) | 32 (18·6) | 27 (12·3) | 167 (15·5) |

| Stage III | 107 (15·6) | 28 (16·3) | 40 (18·3) | 175 (16·3) |

| Stage IV | 106 (15·5) | 24 (14·0) | 34 (15·5) | 164 (15·3) |

| Binet staging system, n (%) | n = 109 | n = 23 | n = 25 | N = 157 |

| Stage A | 30 (27·5) | 7 (30·4) | 9 (36·0) | 46 (29·3) |

| Stage B | 42 (38·5) | 8 (34·8) | 5 (20·0) | 55 (35·0) |

| Stage C | 37 (33·9) | 8 (34·8) | 11 (44·0) | 56 (35·7) |

| Constitutional symptoms,a n (%) | n = 580 | n = 174 | n = 216 | N = 970 |

| Fatigue | 480 (82·8) | 148 (85·1) | 178 (82·4) | 806 (83·1) |

| Fever | 60 (10·3) | 12 (6·9) | 15 (6·9) | 87 (9·0) |

| Night sweats | 226 (39·0) | 59 (33·9) | 53 (24·5) | 338 (34·8) |

| Other | 113 (19·5) | 42 (24·1) | 37 (17·1) | 221 (22·8) |

| Weight loss | 157 (27·1) | 55 (31·6) | 53 (24·5) | 236 (24·3) |

| Nodal bulk (≥5 cm), n/N b (%) | ||||

| Head and neck | 34/777 (4·4) | 5/221 (2·3) | 9/281 (3·2) | 48/1279 (3·8) |

| Axillae | 36/717 (5·0) | 8/198 (4·0) | 16/275 (5·8) | 60/1190 (5·0) |

| Groin | 16/527 (3·0) | 8/152 (4·0) | 4/200 (2·0) | 28/879 (3·2) |

| CCI score, median (range) | 2·0 (2·0–10·0) | 2·0 (2·0–9·0) | 2·0 (2·0–13·0) | 2·0 (2·0–13·0) |

CCI, Charlson Comorbidity Index; ECOG PS, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group Performance Status; LOT, line of therapy.

All relevant constitutional symptoms could be checked.

n refers to the number of patients testing positive. N refers to the total number of patients with recorded lymph node data.

Differences in characteristics at registry enrolment were observed between patients in LOT1 and the combined LOT2/≥3 cohorts, as follows: median age was lower in LOT1 patients, an ECOG PS of 0 was more frequent, and CCI scores of ≥3 were less frequent. Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy–Leukaemia (FACT‐Leu) median HRQoL scores at enrolment were also higher in the LOT1 cohort than in LOT2/LOT≥3 (138·0 vs. 134·2, respectively) and in the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy–General (FACT‐G) total scores (88·0 vs. 85·3, respectively) (Table SIII).

Characteristics also differed by type of treating institution. The median age of patients treated at academic versus community/government centres was 63 years vs. 70 years (P < 0·0001). Significantly more patients at academic centres had CCI scores ≤2 than those at community/government centres (68·4% vs. 53·4%; P = 0·0004). They also had significantly higher estimated creatinine clearance (CrCl) than those treated at community/government centres (medians 86·9 ml/min vs. 72·0 ml/min; P = 0·001). In the German CLL Study Group CLL8 (Cramer et al, 2013) and CLL10 (Eichhorst et al, 2014) trials, ‘fitness’ of patients eligible for intensive chemoimmunotherapy (CIT) regimens were defined as those with CCI scores ≤2, CrCl ≥70 ml/min and ECOG PS ≤1. Applying this definition to our study population, we found that 20% of patients aged <75 years met the criteria; when stratified by LOT, 23% of LOT1 and 14% of LOT2 patients met the criteria. Across institution types, we found that a disproportionate number of the ‘fit’ patients were enrolled at academic centres rather than community/government centres (35% vs. 18%) (Sharman et al, 2014a).

Prognostic information and practice patterns

Fewer than 20% of patients were tested for ZAP70 or CD38 expression at study enrolment (Table 3). MC analyses, most frequently of bone marrow aspirate, were performed in 36·2% of patients, and trisomy 12 (17·6%) and del(13q) (14·2%) were the most commonly detected abnormalities. FISH was performed in 49·3% of patients at enrolment, with del(13q) (45·7%) and trisomy 12 (20·8%) being the most commonly detected abnormalities. Of the 889 patients in LOT1, 65% (n = 576) were tested by MC and/or FISH before enrolment, as were 50% (n = 130) of LOT2 patients, and 45% (n = 155) of LOT≥3 patients. Of the 861 patients overall who were tested at enrolment, 40% of those who progressed had MC and/or FISH analyses retested with a subsequent LOT.

Table 3.

Prognostic factors at enrolment to the registry

| LOT1 (n = 889) | LOT2 (n = 260) | LOT≥3 (n = 345) | All patients (N = 1494) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MC analysis performeda | ||||

| Yes | 347 (39·0) | 81 (31·2) | 113 (32·8) | 541 (36·2) |

| Abnormalities found | 158 (45·5) | 37 (45·7) | 67 (59·3) | 262 (48·4) |

| del(11q) | 36 (10·4) | 6 (7·4) | 17 (15·0) | 59 (10·9) |

| del(13q) | 47 (13·5) | 11 (13·6) | 19 (16·8) | 77 (14·2) |

| del(17p) | 19 (5·5) | 3 (3·7) | 12 (10·6) | 34 (6·3) |

| Trisomy 12 | 57 (16·4) | 14 (17·3) | 24 (21·2) | 95 (17·6) |

| No | 464 (52·2) | 144 (55·4) | 189 (54·8) | 797 (53·3) |

| Not specified | 78 (8·8) | 35 (13·5) | 43 (12·5) | 156 (10·4) |

| FISH analysis performed | ||||

| Yes | 513 (57·7) | 105 (40·4) | 119 (34·5) | 737 (49·3) |

| Abnormalities found | 380 (74·1) | 67 (63·8) | 93 (78·2) | 540 (73·3) |

| del(11q) | 90 (17·5) | 19 (18·1) | 26 (21·8) | 135 (18·3) |

| del(13q) | 238 (46·4) | 43 (41·0) | 56 (47·1) | 337 (45·7) |

| del(17p) | 51 (9·9) | 12 (11·4) | 25 (21·0) | 88 (11·9) |

| Trisomy 12 | 105 (20·5) | 20 (19·0) | 28 (23·5) | 153 (20·8) |

| No | 325 (36·6) | 132 (50·8) | 186 (53·9) | 643 (43·0) |

| ZAP70 performed | ||||

| Yes | 203 (22·8) | 43 (16·5) | 47 (13·6) | 293 (19·6) |

| ZAP70 positive | 115 (56·7) | 22 (51·2) | 33 (70·2) | 170 (58·0) |

| ZAP70 negative | 77 (37·9) | 19 (44·2) | 13 (27·7) | 109 (37·2) |

| Not evaluable/specified | 11 (5·5) | 2 (4·6) | 1 (2·1) | 14 (4·7) |

| No | 686 (77·2) | 217 (83·5) | 298 (86·4) | 1201 (80·4) |

| CD38 performed | ||||

| Yes | 189 (21·3) | 38 (14·6) | 34 (9·9) | 261 (17·5) |

| CD38 positive | 77 (40·7) | 16 (42·1) | 16 (47·1) | 109 (41·8) |

| CD38 negative | 105 (55·6) | 21 (55·3) | 15 (44·1) | 141 (54·0) |

| Not evaluable/specified | 7 (3·7) | 1 (2·6) | 3 (8·8) | 11 (4·2) |

| No | 700 (78·7) | 222 (85·4) | 311 (90·1) | 1233 (82·5) |

| IGVH performed | ||||

| Yes | 70 (7·9) | 13 (5·0) | 10 (2·9) | 93 (6·2) |

| IGVH mutated | 25 (35·7) | 3 (23·1) | 2 (20·0) | 30 (2·0) |

| IGVH unmutated | 45 (64·3) | 9 (69·2) | 8 (80·0) | 62 (4·1) |

| Not evaluable/specified | 0 (0) | 1 (7·7) | 0 (0) | 1 (< 0·1) |

| No | 819 (92·1) | 247 (95·0) | 335 (97·1) | 1401 (93·8) |

All values are n (%).

FISH, fluorescence in situ hybridization; LOT, line of therapy; MC, metaphase cytogenetics.

No refers to patients for whom test results were negative. Not specified refers to patients for whom data is missing or was not completed.

Significant differences in MC/FISH prognostic testing rates were observed between patients in LOT1 and patients in LOT2/≥3 (64·8% vs. 47·1%, respectively; P < 0·0001); therefore, further analyses stratifying by LOT1 versus LOT2/≥3 were performed. In univariate logistic regression analyses of LOT1 patients, 5 of 12 potential prognostic or social predictors were significantly associated with performing MC or FISH: Rai stage ≥II; age ≤75 years; private insurance; white race; and treating‐institution type (academic versus community/government centre) (Mato et al, 2015). In multivariate analysis, treating‐institution type, race, and insurance status remained significant independent predictors of MC/FISH testing at LOT1. When the analysis was performed within the subset of patients enrolled at community/government centres only, age, race and Rai stage were independent significant predictors of performing prognostic testing (Table 4) (Mato et al, 2015).

Table 4.

Multivariate analysis: independent predictors of performing MC/FISH analyses in LOT1 patients

| Institution type | Covariate | OR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|

| All centres | Academic versus community/government centre | 1·76 (1·03–2·99) |

| White versus other ethnicity | 1·90 (1·13–3·17) | |

| Private insurance versus other | 1·44 (1·08–1·92) | |

| Community/government centres | White versus other ethnicity | 2·40 (1·26–4·58) |

| <75 versus ≥75 years of age | 1·44 (1·01–2·05) | |

| Rai stage ≥II versus ≤I | 1·52 (1·07–2·14) |

CI, confidence interval; FISH, fluorescence in situ hybridization; LOT, line of therapy; MC, metaphase cytogenetics; OR, odds ratio.

Survival outcomes and CLL disease history and therapy

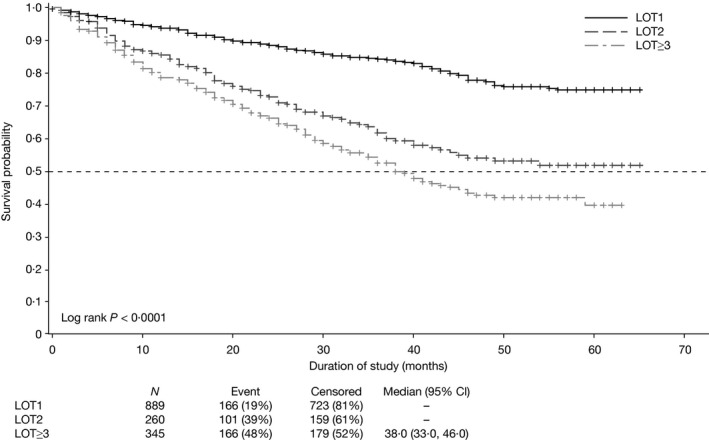

The median time from diagnosis to study entry (for any LOT) was 37 months (range 0–390). Figure 1 depicts the OS estimates for the fully enrolled Connect CLL. Median follow‐up was 36·6 months (range 1–65) in LOT1, 28·8 months (range 0–63) in LOT2 and 25·8 months (range 0–62) in LOT≥3. Median OS has not been reached for LOT1 and LOT2 cohorts. For patients in the LOT1 group, the most common reasons for treatment initiation at enrolment to the registry were progressive marrow failure (39·9%) and massive bulky or progressive lymphadenopathy (37·1%).

Figure 1.

Kaplan–Meier curves of overall survival stratified by LOT. Data cut‐off: 25 August 2015. CI, confidence interval; LOT, line of therapy.

The most commonly used treatment approach across all cohorts and all age groups was CIT, which was prescribed to a total of 895 patients (59·9%) (Table 5). Chlorambucil‐based therapy was infrequently prescribed in the total population and across all LOTs (~4%). In LOT1 patients, the most commonly prescribed therapies were purine analogue‐based (37·4%) and bendamustine‐based (22·7%) CITs, although with increasing patient age a decreased use of purine analogue‐based CIT was observed in favour of bendamustine‐based CIT and anti‐CD20 monoclonal antibody therapies. Overall, in LOT2 patients, bendamustine‐based CIT combinations were the most frequently prescribed therapies (28·9%), particularly in patients aged ≥65 to <75 years (37·8%). LOT2 patients aged ≥75 years received purine analogue‐based CIT and anti‐CD20 monoclonal antibody monotherapies most frequently. LOT≥3 patients also received CIT combinations most frequently (43·5% overall; with 29·3% bendamustine‐based CIT and 10·4% purine analogue‐based CIT). A variety of purine analogue‐based regimens were used (Table 6). Across all LOTs, patients were infrequently enrolled into clinical trials; in LOT1, 30 patients (3·4%) were enrolled into clinical trials compared with 5 (1·9%) in LOT2 and 5 (4·6%) in LOT≥3 (Table 5).

Table 5.

All therapy categories at enrolment to the registry

| Patients, age (years) | Therapy prescribed at enrolment | LOT1 | LOT2 | LOT≥3 | Overall | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | n (%) | N | n (%) | N | n (%) | N | n (%) | ||

| All | CIT | 889 | 588 (66·1) | 260 | 157 (60·4) | 345 | 150 (43·5) | 1,494 | 895 (59·9) |

| Purine analogue‐based CIT | 332 (37·4) | 65 (25·0) | 36 (10·4) | 433 (29·0) | |||||

| Bendamustine‐based CIT | 202 (22·7) | 75 (28·9) | 101 (29·3) | 378 (25·3) | |||||

| Chlorambucil‐based CIT | 10 (1·1) | 0 | 1 (0·3) | 11 (0·7) | |||||

| CHOP/CVP/CTX‐based CIT | 33 (3·7) | 13 (5·0) | 9 (2·6) | 55 (3·7) | |||||

| Other CIT | 11 (1·2) | 4 (1·5) | 3 (0·9) | 18 (1·2) | |||||

| Chemotherapy | 91 (10·2) | 26 (10·0) | 35 (10·1) | 152 (10·2) | |||||

| Chlorambucil monotherapy | 41 (4·6) | 6 (2·3) | 11 (3·2) | 58 (3·9) | |||||

| Anti‐CD20 mAb monotherapy | 116 (13·1) | 45 (17·3) | 72 (20·9) | 233 (15·6) | |||||

| Rituximab monotherapy | 104 (11·7) | 38 (14·6) | 44 (12·8) | 186 (12·4) | |||||

| Ofatumumab monotherapy | 5 (0·6) | 2 (0·8) | 23 (6·7) | 30 (2·0) | |||||

| Kinase inhibitor therapies | 0 | 0 | 1 (0·3) | 1 (0·1) | |||||

| Immunomodulatory therapy | 17 (1·9) | 2 (0·8) | 5 (1·5) | 24 (1·6) | |||||

| Conditioning regimen + SCT | 0 | 0 | 1 (0·3) | 1 (0·1) | |||||

| High‐dose steroid (±mAb) | 1 (0·1) | 3 (1·2) | 3 (0·9) | 7 (0·5) | |||||

| Clinical trial | 30 (3·4) | 5 (1·9) | 24 (7·0) | 59 (4·0) | |||||

| Othera | 46 (5·2) | 22 (8·5) | 54 (15·7) | 122 (8·2) | |||||

| <65 | CIT | 335 | 265 (79·1) | 83 | 56 (67·5) | 109 | 49 (45·0) | 527 | 370 (70·2) |

| Purine analogue‐based CIT | 186 (55·5) | 24 (28·9) | 15 (13·8) | 225 (42·7) | |||||

| Bendamustine‐based CIT | 64 (19·1) | 27 (32·5) | 31 (28·4) | 122 (23·2) | |||||

| Chlorambucil‐based CIT | 3 (0·9) | 0 | 0 | 3 (0·6) | |||||

| CHOP/CVP/CTX‐based CIT | 10 (3·0) | 4 (4·8) | 2 (1·8) | 16 (3·0) | |||||

| Other CIT | 2 (0·6) | 1 (1·2) | 1 (0·9) | 4 (0·8) | |||||

| Chemotherapy | 18 (5·4) | 5 (6·0) | 5 (4·6) | 28 (5·3) | |||||

| Chlorambucil monotherapy | 4 (1·2) | 1 (1·2) | 0 | 5 (0·9) | |||||

| Anti‐CD20 mAb monotherapy | 25 (7·5) | 9 (10·8) | 26 (23·9) | 60 (11·4) | |||||

| Rituximab monotherapy | 23 (6·9) | 8 (9·6) | 14 (12·8) | 45 (8·5) | |||||

| Ofatumumab monotherapy | 0 | 0 | 10 (9·2) | 10 (19·0) | |||||

| Immunomodulatory therapy | 7 (2·1) | 1 (1·2) | 3 (2·8) | 11 (2·1) | |||||

| Conditioning regimen + SCT | 0 | 0 | 1 (0·9) | 1 (0·2) | |||||

| High‐dose steroid (± mAb) | 0 | 2 (2·4) | 1 (0·9) | 3 (0·6) | |||||

| Clinical trial | 9 (2·7) | 2 (2·4) | 5 (4·6) | 16 (3·0) | |||||

| Othera | 11 (3·3) | 8 (9·6) | 19 (17·4) | 38 (7·2) | |||||

| ≥65 to <75 | CIT | 295 | 192 (65·1) | 82 | 56 (68·3) | 135 | 65 (48·2) | 512 | 313 (61·1) |

| Purine analogue‐based CIT | 100 (33·9) | 20 (24·4) | 17 (12·6) | 137 (26·8) | |||||

| Bendamustine‐based CIT | 73 (24·8) | 31 (37·8) | 43 (31·9) | 147 (28·7) | |||||

| Chlorambucil‐based CIT | 2 (0·7) | 0 | 0 | 2 (0·4) | |||||

| CHOP/CVP/CTX‐based CIT | 10 (3·4) | 3 (3·7) | 5 (3·7) | 18 (3·5) | |||||

| Other CIT | 7 (2·4) | 2 (2·4) | 0 | 9 (1·8) | |||||

| Chemotherapy | 29 (9·8) | 4 (4·9) | 14 (10·4) | 47 (9·2) | |||||

| Chlorambucil monotherapy | 15 (5·1) | 2 (2·4) | 2 (1·5) | 19 (3·7) | |||||

| Anti‐CD20 mAb monotherapy | 34 (11·5) | 15 (18·3) | 23 (17·0) | 72 (14·1) | |||||

| Rituximab monotherapy | 31 (10·5) | 14 (17·1) | 16 (11·9) | 61 (11·9) | |||||

| Ofatumumab monotherapy | 2 (0·7) | 0 | 7 (5·2) | 9 (1·8) | |||||

| Immunomodulatory therapy | 6 (2·0) | 0 | 2 (1·5) | 8 (1·6) | |||||

| High‐dose steroid (± mAb) | 0 | 1 (1·2) | 1 (0·7) | 2 (0·4) | |||||

| Clinical trial | 13 (4·4) | 1 (1·2) | 13 (9·6) | 27 (5·3) | |||||

| Othera | 21 (7·1) | 5 (6·1) | 17 (12·6) | 43 (8·4) | |||||

| ≥75 | CIT | 259 | 131 (50·6) | 95 | 45 (47·4) | 101 | 36 (35·6) | 455 | 212 (46·6) |

| Purine analogue‐based CIT | 46 (17·8) | 21 (22·1) | 4 (4·0) | 71 (15·6) | |||||

| Bendamustine‐based CIT | 65 (25·1) | 17 (17·9) | 27 (26·7) | 109 (24·0) | |||||

| Chlorambucil‐based CIT | 5 (1·9) | 0 | 1 (1·0) | 6 (1·3) | |||||

| CHOP/CVP/CTX‐based CIT | 13 (5·0) | 6 (6·3) | 2 (2·0) | 21 (4·6) | |||||

| Other CIT | 2 (0·8) | 1 (1·1) | 2 (2·0) | 5 (1·1) | |||||

| Chemotherapy | 44 (17·0) | 17 (17·9) | 16 (15·8) | 77 (16·9) | |||||

| Chlorambucil monotherapy | 22 (8·5) | 3 (3·2) | 9 (8·9) | 34 (7·5) | |||||

| Anti‐CD20 mAb monotherapy | 57 (22·0) | 21 (22·1) | 23 (22·8) | 101 (22·2) | |||||

| Rituximab monotherapy | 50 (19·3) | 16 (16·8) | 14 (13·9) | 80 (17·6) | |||||

| Ofatumumab monotherapy | 3 (1·2) | 2 (2·1) | 6 (5·9) | 11 (2·4) | |||||

| Kinase inhibitor therapies | 0 | 0 | 1 (1·0) | 1 (0·2) | |||||

| Immunomodulatory therapy | 4 (1·5) | 1 (1·1) | 0 | 5 (1·1) | |||||

| High‐dose steroid (± mAb) | 1 (0·4) | 0 | 1 (1·0) | 2 (0·4) | |||||

| Clinical trial | 8 (3·1) | 2 (2·1) | 6 (5·9) | 16 (3·5) | |||||

| Othera | 14 (5·4) | 9 (9·5) | 18 (17·8) | 41 (9·0) | |||||

CHOP, cyclophosphamide, hydroxydaunorubicin, oncovin, prednisolone; CIT, chemoimmunotherapy; CTX, cyclophosphamide; CVP, cyclophosphamide, vincristine, prednisolone; LOT, line of therapy; mAb, monoclonal antibody; SCT, stem cell transplant.

Other, regimens that were not classifiable as conventional CLL regimens.

Table 6.

Purine analogue‐based CIT regimens administered at enrolment to the registry

| LOT1 (n = 332) | LOT2 (n = 65) | LOT≥3 (n = 36) | Overall (n = 433) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Purine analogue‐based CIT treatment regimen, n (%) | ||||

| Cladribine + R | 0 | 0 | 1 (2·7) | 1 (0·2) |

| FCR + Dex | 8 (2·4) | 1 (1·5) | 2 (5·6) | 11 (2·5) |

| FCR + Len | 4 (1·2) | 0 | 0 | 4 (0·9) |

| FC + ofatumumab | 0 | 1 (1·5) | 0 | 1 (0·2) |

| FCR + prednisone | 3 (0·9) | 0 | 0 | 3 (0·7) |

| FCR | 230 (69·3) | 34 (52·3) | 18 (50·0) | 282 (65·1) |

| FCR + methotrexate | 0 | 1 (1·5) | 0 | 1 (0·2) |

| CR + pentostatin + dexamethasone | 1 (0·3) | 0 | 0 | 1 (0·2) |

| CR + pentostatin | 24 (7·2) | 8 (12·3) | 6 (16·7) | 38 (8·8) |

| FR + dexamethasone | 6 (1·8) | 2 (3·1) | 0 | 8 (1·8) |

| F + ofatumumab | 0 | 0 | 1 (2·7) | 1 (0·2) |

| FR + prednisone | 1 (0·3) | 0 | 1 (2·7) | 2 (0·5) |

| FR | 55 (16·6) | 18 (27·7) | 7 (19·4) | 80 (18·5) |

CIT, chemoimmunotherapy; CR, cyclophosphamide, rituximab; Dex, dexamethasone; F, fludarabine; FC, fludarabine, cyclophosphamide; FCR, fludarabine, cyclophosphamide, rituximab; FR, fludarabine, rituximab; Len, lenalidomide; LOT, line of therapy; R, rituximab.

Discussion

The majority of patients in the Connect CLL registry were treated at community‐based centres. As such, the registry provides detailed, patient‐level observational data of a diverse population of patients with CLL who would, on the whole, be unsuitable for stringent clinical trials.

Overall, the Connect CLL registry appears to be generally representative of the US CLL population. The median age of patients enrolled in the Connect CLL registry was 69 years whereas the median age of patients at diagnosis reported in the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program was 71 years (Altekruse et al, 2010). There was a high proportion of older patients (65% ≥65 years) in the Connect CLL registry, allowing for more detailed analyses across age groups. The ratio of white to black patients was similar to that reported in SEER registries (Shenoy et al, 2011). The majority of patients (88%) were being cared for at community‐based centres and outside the context of interventional clinical trials, thereby allowing insight into more typical, community‐based management of CLL.

Genomic aberrations in CLL are important predictors of disease progression and survival, and unfavourable prognostic markers can be easily identified using MC or FISH (Damle et al, 1999; Hamblin et al, 1999; Döhner et al, 2000). The National Comprehensive Cancer Network (National Comprehensive Cancer Network, 2014; https://www.nccn.org/), the IWCLL (Hallek et al, 2008) guidelines, and a recent meta‐analysis of genetic testing in newly diagnosed CLL (Parikh et al, 2016) recommend prognostic testing, such as FISH and IGHV, in the management of patients with CLL. As genetic defects may be acquired as the disease progresses, repeat testing prior to each line of therapy may be useful (Hallek et al, 2008); however, limited information exists about how these guidelines are interpreted in practice. In Connect CLL, genetic testing by MC and FISH was performed in only 39% and 58% of patients before LOT1, respectively; only 6·4% of patients across all LOTs were tested for IGHV somatic hypermutation. Additionally, only 40% of patients tested at enrolment and who progressed were retested by MC and/or FISH with a subsequent LOT. These data may suggest a dearth of routine genetic testing in the community as a means of guiding treatment selection; however, as this is an observational study, underreporting or missing data could partially explain these lower diagnostic testing rates.

The importance of FISH testing before therapy selection is highlighted in the inclusion criteria of recent CIT clinical trials. In CLL10 (Eichhorst et al, 2013), for example, and in ongoing front‐line studies comparing CIT approaches with kinase inhibitors (NCT02048813; NCT01886872), patients with del(17p) are excluded due to the poor outcomes expected with CITs. More recent data, however, from patients receiving ibrutinib or idelalisib with rituximab, demonstrate that these agents may, in part, overcome traditional unfavourable characteristics such as del(17p) (Byrd et al, 2014; Furman et al, 2014; O'Brien et al, 2014; Sharman et al, 2014b). Nevertheless, even with these newer targeted agents, patients with high‐risk FISH cytogenetics are shown to relapse more quickly than their low‐risk counterparts. Recent data also demonstrate the value of MC in the risk stratification of ibrutinib‐treated patients (Thompson et al, 2014). In the current era of targeted therapies, the presence of certain genetic abnormalities may be of relevance when personalizing therapies. Now that kinase inhibitors are widely available, it will be important to observe if the use of genetic testing will dramatically affect treatment selection in Connect CLL participants.

Differences observed between clinical trial participants and the community‐based CLL population raise the question as to whether promising results obtained from clinical trials can be extrapolated to routine practice. Recent data from landmark CIT clinical trials, such as CLL8 (Cramer et al, 2013) and CLL10 (Eichhorst et al, 2014), demonstrate that study participants treated with CIT regimens, such as fludarabine, cyclophosphamide, and rituximab (FCR) or bendamustine and rituximab (BR), are generally younger and have fewer comorbid conditions than typical patients with CLL (Hallek et al, 2010; Eichhorst et al, 2013). Specifically, patients enrolled in CLL8 (FCR versus fludarabine and cyclophosphamide) had a median age of 61 years, and only 11% of patients aged ≥70 years were treated with FCR (Cramer et al, 2013). Similarly, in CLL10 (FCR versus BR), the median age was 62 years and the median Cumulative Illness Rating Scale (CIRS) score was 2 (Eichhorst et al, 2014). CIRS scores were not captured in our analysis, although we did calculate CCI scores, which are reported to provide reasonable correlation with the CIRS as objective estimates of medical comorbidity (Extermann et al, 1998). Although the median CCI score in the Connect CLL registry was 2, 45% of patients had CCI ≥3, which signifies the presence of multiple comorbid conditions and predicts a 10‐year mortality of 59% attributable to comorbid disease (Charlson et al, 1987).

Many would argue that CIT combinations, particularly FCR, are the standard of care in the front‐line treatment of fit patients with CLL, yet only 45·4% of patients <75 years of age in the Connect CLL registry were treated with purine analogue‐based CIT in the LOT1 cohort. When considering the inclusion criteria for patients in studies such as CLL8 and CLL10, we estimated that only 20% of patients in the Connect CLL registry would have been considered suitable study candidates. Therefore, our CIT‐treated population appears different to that of the CLL8 and CLL10 trials (Cramer et al, 2013; Eichhorst et al, 2014), and may provide important insights into whether the results of clinical trials can be extended to routine community‐based treatment.

The survival data represent heterogeneously treated CLL patient populations in front‐line and relapsed settings. As the data continue to mature, they will provide a unique opportunity for further stratification of outcomes based on clinical/prognostic factors and clinically relevant comparisons – particularly those not easily made in the context of clinical trials.

As this registry enrolled patients between 2010 and 2014, and enrolment in clinical trials was low (<5%), very few patients were treated with investigational kinase inhibitor therapies. The approval of agents, such as ibrutinib and idelalisib, by the United States Food and Drug Administration has transformed the management of CLL, particularly for patients with relapsed/refractory (R/R) disease, unfavourable prognostic factors, or advanced age (for whom CIT regimens may be too toxic) (Grosicki, 2015; Morabito et al, 2015a,b; Tucker & Rule, 2015). Landmark studies that contributed to these approvals and their widespread adoption included randomized comparisons against agents such as chlorambucil, ofatumumab, and rituximab (Byrd et al, 2014; Furman et al, 2014; Sharman et al, 2014b; Hillmen et al, 2015). However, recent editorials have questioned the clinical equipoise of such comparisons, particularly when crossover to the experimental arm was not permitted despite overwhelming activity from previously reported Phase 1b/2 studies (O'Brien, 2013; Schuster, 2013). Data from the Connect CLL registry were used to evaluate how frequently these ‘comparator arm’ treatment approaches were prescribed in the community setting. Across all LOTs and all ages, chlorambucil monotherapy was prescribed to 3·9% of patients, and ofatumumab monotherapy to 2·0% of patients (76·7% of all prescriptions were to LOT ≥ 3 patients). Rituximab monotherapy was prescribed to 12·4% of patients across all LOTs and all ages, and was most frequently used in the R/R setting (13·6% of patients in LOT2/LOT ≥ 3) and in older patients (17·6% of patients aged ≥75 years). As the armamentarium of active agents continues to increase, these data may help to ascertain which therapies should be used as ‘standard therapy’ controls in future comparisons.

‘There are several strengths to enrolling only treated patients to a registry such as this. Firstly, a registry of treated patients prevents the introduction of bias from uncontrolled systematic differences that exist between treated and non‐treated patients. Secondly, a registry restricted to treated patients can help to ensure that the sample size of each treatment subgroup is feasible for the analysis of real‐world treatment patterns and comparative effectiveness. There are, however, potential sources of bias inherent to any observational cohort study arising from patient selection, data collection, and in assessing treatment effectiveness due to lack of treatment randomization. Therefore, the Connect CLL registry made an effort to enrol patients who were representative of the underlying US population, and to include patients from multiple geographically diverse and primarily community‐based centres. Patients were enrolled from a large number of sites distributed widely across the USA and the number of patients enrolled per site was capped to ensure a representative sample of CLL patients participated in the study. In order to further minimize bias and better understand the patient population included in the study, personnel at sites were educated to consecutively enrol patients as they entered a line of CLL treatment. Personnel at each centre were also reminded to invite every eligible patient with CLL to participate in the registry, regardless of treatment, medical history or ECOG PS. Nevertheless, the majority of patients in the study had an ECOG PS of ≤1 (92·7%) and were insured either privately (42·0%) or through the Medicare program (61·2%), which may limit our ability to assess for differences stratified by performance status and insurance type. In addition, although enrolling patients only when they started treatment prevented us from accurately describing all patients diagnosed with CLL, it did allow us to describe treatment patterns, a main objective of the registry.

In this analysis of Connect CLL data, important trends in practice patterns including infrequent use of prognostic testing, marked underutilization of clinical trials, and increasing use of monotherapies (particularly for R/R patients) were found. These data reflect real‐world practice patterns and the broad experiences of both community and academic physicians involved in the treatment of CLL patients. These findings may provide physicians with a greater understanding of the realities of treating CLL patients and the challenges commonly encountered in everyday practice. These outcomes will provide further insights and information to those involved in the community‐based care of patients with CLL.

Authorship

All authors participated in the acquisition and/or analysis or interpretation of the data reported in this manuscript. All authors were involved in drafting the paper, critical review, and approval of the manuscript, and are fully responsible for all content and editorial decisions.

Disclosures

AM has received research funding from Celgene Corporation, AbbVie, Gilead, Pronai, and TG Therapeutics; has been a consultant for AbbVie; and has been a member of a speakers’ bureau for Celgene Corporation; CN has received research funding from Celgene Corporation, Seattle Genetics, and Genentech; and has been on advisory boards for Celgene Corporation, Astellas, Genentech, and Seattle Genetics; NEK has received research funding from Gilead, Celgene Corporation, Hospira, Genentech, and Pharmacyclics; and has been on advisory committees for Gilead and Celgene Corporation; MAW has been a consultant for Celgene Corporation, Pharmacyclics, and Gilead; NL has received research funding from Gilead, AbbVie, Genentech, Infinity, and Pronai; has been a consultant for Gilead, AbbVie, Genentech, Pronai, and Pharmacyclics; and has been on an advisory committee for Celgene Corporation; TJK has received research funding from Celgene Corporation and Roche; has been a consultant for Celgene Corporation, Pharmacyclics, and AbbVie; and has received honoraria from Pharmacyclics; DLG has been a consultant and member of a speakers’ bureau for Celgene Corporation; IWF has received research funding from Celgene Corporation, Novartis Pharmaceuticals, Karyopharm Therapeutics, Gilead Sciences, Genentech, Tragara Pharmaceuticals, Infinity Pharmaceuticals, Bristol‐Myers Squibb, ImmunoGen, Pfizer, OncoMed Pharmaceuticals, Portola Pharmaceuticals, Calithera Biosciences, Agios, Seattle Genetics, Millennium Pharmaceuticals, Janssen, Constellation Pharmaceuticals, Incyte, and has stock or ownership in RainTree; MFK has been a consultant for Celgene Corporation; CRF has received research funding from Gilead, Spectrum, Millennium, Janssen, Infinity, AbbVie, Acerta, Pharmacyclics, and TG Therapeutics; has been a consultant for Celgene Corporation, Optum Rx, Gilead, Seattle Genetics, Millennium, and Genentech/Roche; and has received honoraria from Celgene Corporation; CMF has received research funding from Genentech and Gilead, has been a consultant and part of a speakers’ bureau for Celgene Corporation, Gilead, Janssen, Pharmacyclics, Seattle Genetics, and Genentech, has been on an advisory committee for Celgene Corporation, and has received honoraria from Janssen; PK, ASS, KS, and EDF are employees of Celgene Corporation and have equity; JPS has received honoraria from Genentech, Gilead, and TG Therapeutics; has been a consultant for Celgene Corporation, Genentech, Gilead, and Pharmacyclics; has been a member of a speakers’ bureau for Gilead; has received research funding from Celgene Corporation, Genentech, Gilead, Pharmacyclics, TG Therapeutics, Seattle Genetics, and Acerta; and has received travel expenses from Celgene Corporation and Gilead.

Supporting information

Table SI. Clinical characteristics at enrolment to the registry.

Table SII. Haematology variables at enrolment to the registry stratified by Rai stage.

Table SIII. HRQoL at enrolment to the registry as assessed by FACT‐Leu and FACT‐G.

Acknowledgements

All individuals involved in the maintenance of the Connect® CLL registry. The authors received medical writing assistance in the preparation of this manuscript from Ronald van Olffen, PhD, CMPP and Eva Polk, PhD, CMPP, employed by Excerpta Medica BV and supported by Celgene Corporation. The authors are fully responsible for all content and editorial decisions. The Connect CLL Registry is sponsored and funded by Celgene Corporation.

References

- Abel, G.A. (2011) The real world: CLL. Blood, 117, 3481–3482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altekruse S.F., Kosary C.L., Krapcho M., Neyman N., Aminou R., Waldron W., Ruhl J., Howlader N., Tatalovich Z., Cho H., Mariotto A., Eisner M.P., Lewis D.R., Cronin K., Chen H.S., Feuer E.J., Stinchcomb D.G. & Edwards B.K. (eds). (2010) SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975–2007. Available from: http://seer.cancer.gov/csr/1975_2007.htm [Accessed September 3 2015].

- Byrd, J.C. , Brown, J.R. , O'Brien, S. , Barrientos, J.C. , Kay, N.E. , Reddy, N.M. , Coutre, S. , Tam, C.S. , Mulligan, S.P. , Jaeger, U. , Devereux, S. , Barr, P.M. , Furman, R.R. , Kipps, T.J. , Cymbalista, F. , Pocock, C. , Thornton, P. , Caligaris‐Cappio, F. , Robak, T. , Delgado, J. , Schuster, S.J. , Montillo, M. , Schuh, A. , de Vos, S. , Gill, D. , Bloor, A. , Dearden, C. , Moreno, C. , Jones, J.J. , Chu, A.D. , Fardis, M. , McGreivy, J. , Clow, F. , James, D.F. , Hillmen, P. & RESONATE Investigators (2014) Ibrutinib versus ofatumumab in previously treated chronic lymphoid leukemia. New England Journal of Medicine, 371, 213–223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charlson, M.E. , Pompei, P. , Ales, K.L. & MacKenzie, C.R. (1987) A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. Journal of Chronic Disease, 40, 373–383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CinicalTrials.gov . A Randomized Phase III Study of Bendamustine Plus Rituximab Versus Ibrutinib Plus Rituximab Versus Ibrutinib Alone in Untreated Older Patients (≥ 65 Years of Age) With Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia (CLL). Available from: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01886872 [Accessed September 3, 2015].

- ClinicalTrials.gov . A Randomized Phase III Study of Ibrutinib (PCI‐32765)‐Based Therapy vs Standard Fludarabine, Cyclophosphamide, and Rituximab (FCR) Chemoimmunotherapy in Untreated Younger Patients With Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia (CLL). Available from: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02048813 [Accessed September 3, 2015].

- Cramer, P. , Fink, A.M. , Busch, R. , Eichhorst, B. , Wendtner, C.M. , Pflug, N. , Langerbeins, P. , Bahlo, J. , Goede, V. , Schubert, F. , Döhner, H. , Stilgenbauer, S. , Dreger, P. , Kneba, M. , Böttcher, S. , Mayer, J. , Hallek, M. & Fischer, K. (2013) Second‐line therapies of patients initially treated with fludarabine and cyclophosphamide or fludarabine, cyclophosphamide and rituximab for chronic lymphocytic leukemia within the CLL8 protocol of the German CLL Study Group. Leukemia & Lymphoma, 54, 1821–1822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuneo, A. , Cavazzini, F. , Ciccone, M. , Daghia, G. , Sofritti, O. , Saccenti, E. , Negrini, M. & Rigolin, G.M. (2014) Modern treatment in chronic lymphocytic leukemia: impact on survival and efficacy in high‐risk subgroups. Cancer Medicine, 3, 555–564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damle, R.N. , Wasil, T. , Fais, F. , Ghiotto, F. , Valetto, A. , Allen, S.L. , Buchbinder, A. , Budman, D. , Dittmar, K. , Kolitz, J. , Lichtman, S.M. , Schulman, P. , Vinciguerra, V.P. , Rai, K.R. , Ferrarini, M. & Chiorazzi, N. (1999) Ig V gene mutation status and CD38 expression as novel prognostic indicators in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood, 94, 1840–1847. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Döhner, H. , Stilgenbauer, S. , Benner, A. , Leupolt, E. , Kröber, A. , Bullinger, L. , Döhner, K. , Bentz, M. & Lichter, P. (2000) Genomic aberrations and survival in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. New England Journal of Medicine, 343, 1910–1916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eichhorst, B. , Fink, A.M. , Busch, R. , Lange, E. , Köppler, H. , Kiehl, M. , Sokler, M. , Schlag, R. , Vehling‐Kaiser, U. , Kochling, G.R.A. , Ploger, C. , Gregor, M. , Plesner, T. , Trneny, M. , Fischer, K. , Dohner, H. , Kneba, M. , Wendtner, C. , Klapper, C. , Kreuzer, K.‐A. , Stilgenbauer, S. , Bottcher, S. & Hallek, M. (2013) Chemoimmunotherapy with fludarabine (F), cyclophosphamide (C), and rituximab (R) (FCR) versus bendamustine and rituximab (BR) in previously untreated and physically fit patients (pts) with advanced chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL): results of a planned interim analysis of the CLL10 trial, an international, randomized study of the German CLL Study Group (GCLLSG). Blood, 122, 526. [Google Scholar]

- Eichhorst, B. , Fink, A.M. , Busch, R. , Kovacs, G. , Maurer, C. , Lange, E. , Köppler, H. , G Kiehl, M. , Soekler, M. , Schlag, R. , Vehling‐Kaiser, U. , R. A. Köchling, G. , Plöger, C. , Gregor, M. , Trneny, M. , Fischer, K. , Döhner, H. , Kneba, M. , Wendtner, C.‐M. , Klapper, W. , Kreuzer, K.‐A. , Stilgenbauer, S. , Böttcher, S. & Hallek, M. (2014) Frontline chemoimmunotherapy with fludarabine (F), cyclophosphamide (C), and rituximab (R) (FCR) shows superior efficacy in comparison to bendamustine (B) and rituximab (BR) in previously untreated and physically fit patients (pts) with advanced chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL): final analysis of an international, randomized study of the German CLL Study Group (GCLLSG) (CLL10 Study). Blood, 124, 19. [Google Scholar]

- Extermann, M. , Overcash, J. , Lyman, G.H. , Parr, J. & Balducci, L. (1998) Comorbidity and functional status are independent in older cancer patients. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 16, 1582–1587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furman, R.R. , Sharman, J.P. , Coutre, S.E. , Cheson, B.D. , Pagel, J.M. , Hillmen, P. , Barrientos, J.C. , Zelenetz, A.D. , Kipps, T.J. , Flinn, I. , Ghia, P. , Eradat, H. , Ervin, T. , Lamanna, N. , Coiffier, B. , Pettitt, A.R. , Ma, S. , Stilgenbauer, S. , Cramer, P. , Aiello, M. , Johnson, D.M. , Miller, L.L. , Li, D. , Jahn, T.M. , Dansey, R.D. , Hallek, M. & O'Brien, S.M. (2014) Idelalisib and rituximab in relapsed chronic lymphocytic leukemia. New England Journal of Medicine, 370, 997–1007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grosicki, S. (2015) Ofatumumab for the treatment of chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Expert Review of Hematology, 8, 265–272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hallek, M. (2013) Signaling the end of chronic lymphocytic leukemia: new frontline treatment strategies. Blood, 122, 3723–3734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hallek, M. , Cheson, B.D. , Catovsky, D. , Caligaris‐Cappio, F. , Dighiero, G. , Döhner, H. , Hillmen, P. , Keating, M.J. , Montserrat, E. , Rai, K.R. , Kipps, T.J. & International Workshop on Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia (2008) Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of chronic lymphocytic leukemia: a report from the International Workshop on Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia updating the National Cancer Institute‐Working Group 1996 guidelines. Blood, 111, 5446–5456. Erratum in: (2008) Blood, 112, 5259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hallek, M. , Fischer, K. , Fingerle‐Rowson, G. , Fink, A.M. , Busch, R. , Mayer, J. , Hensel, M. , Hopfinger, G. , Hess, G. , von Grünhagen, U. , Bergmann, M. , Catalano, J. , Zinzani, P.L. , Caligaris‐Cappio, F. , Seymour, J.F. , Berrebi, A. , Jäger, U. , Cazin, B. , Trneny, M. , Westermann, A. , Wendtner, C.M. , Eichhorst, B.F. , Staib, P. , Bühler, A. , Winkler, D. , Zenz, T. , Böttcher, S. , Ritgen, M. , Mendila, M. , Kneba, M. , Döhner, H. , Stilgenbauer, S. & International Group of Investigators & German Chronic Lymphocytic Leukaemia Study Group (2010) Addition of rituximab to fludarabine and cyclophosphamide in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukaemia: a randomised, open‐label, phase 3 trial. Lancet, 376, 1164–1174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamblin, T.J. , Davis, Z. , Gardiner, A. , Oscier, D.G. & Stevenson, F.K. (1999) Unmutated Ig V(H) genes are associated with a more aggressive form of chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood, 94, 1848–1854. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hillmen, P. , Robak, T. , Janssens, A. , Babu, K.G. , Kloczko, J. , Grosicki, S. , Doubek, M. , Panagiotidis, P. , Kimby, E. , Schuh, A. , Pettitt, A.R. , Boyd, T. , Montillo, M. , Gupta, I.V. , Wright, O. , Dixon, I. , Carey, J.L. , Chang, C.N. , Lisby, S. , McKeown, A. , Offner, F. & COMPLEMENT 1 Study Investigators (2015) Chlorambucil plus ofatumumab versus chlorambucil alone in previously untreated patients with chronic lymphocytic leukaemia (COMPLEMENT 1): a randomised, multicentre, open‐label phase 3 trial. Lancet, 385, 1873–1883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mato, A. , Flowers, C. , Farber, C.M. , Weiss, A. , Kipps, T. , Kozloff, M. , Nabhan, C. , Flinn, I. , Grinblatt, D.L. , Lamanna, N. , Sullivan, K.A. , Kiselev, P. , Flick, E.D. , Foon, K.A. , Swern, A.S. & Sharman, J.P. (2015) Prognostic testing patterns in CLL pts treated in U.S. practices from the Connect CLL Registry. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 33(Suppl. 15), 7013. [Google Scholar]

- Mertens, D. & Stilgenbauer, S. (2014) Prognostic and predictive factors in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia: relevant in the era of novel treatment approaches? Journal of Clinical Oncology, 32, 869–872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morabito, F. , Recchia, A.G. , Vigna, E. , De Stefano, L. , Bossio, S. , Morabito, L. , Pellicanò, M. , Palummo, A. , Storino, F. , Caruso, N. & Gentile, M. (2015a) Promising therapies for the treatment of chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Expert Opinion on Investigative Drugs, 24, 795–807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morabito, F. , Gentile, M. , Seymour, J.F. & Polliack, A. (2015b) Ibrutinib, idelalisib and obinutuzumab for the treatment of patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia: three new arrows aiming at the target. Leukemia & Lymphoma, 56, 3250–3256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network (2014) Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia. Available from: https://www.nccn.org/store/login/login.aspx?ReturnURL=http://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/nhl.pdf [Accessed September 3, 2015].

- O'Brien, S. (2013) Ibrutinib CLL Trial: Where is the Equipoise? Available from: http://www.ascopost.com/issues/may-1-2013/ibrutinib-cll-trial-where-is-the-equipoise/ [Accessed September 3, 2015].

- O'Brien, S. , Jones, J.A. , Coutre, S. , Coutre, S. , Mato, A. , Hillmen, P. , Tam, C. , Osterborg, A. , Siddiqi, T. , Thirman, M.J. , Furman, R.R. , Ilhan, O. , Keating, K. , Call, T.G. , Brown, J.R. , Stevens‐Brogan, M. , Li, Y. , Fardis, M. , Clow, F. , James, D.F. , Chu, A.D. , Hallek, M. & Stilgenbauer, S. (2014) Efficacy and safety of ibrutinib in patients with relapsed or refractory chronic lymphocytic leukemia or small lymphocytic leukemia with 17p deletion: results from the phase II RESONATE™‐17 trial. Blood, 124, 327. [Google Scholar]

- Parikh, S.A. , Strati, P. , Tsang, M. , West, C.P. & Shanafelt, T.D. (2016) Should IGHV status and FISH testing be performed in all CLL patients at diagnosis? A systematic review and meta‐analysis. Blood, 127, 1752–1760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuster, S.J. (2013) SIDEBAR: The Ethical Imperative of Clinical Equipoise. Available from: http://www.ascopost.com/issues/may-1,-2013/sidebar-the-ethical-imperative-of-clinical-equipoise.aspx [Accessed September 3, 2015].

- Sharman, J.P. , Mato, A. , Kay, N.E. , Kipps, T. , Lamanna, N. , Weiss, M. , Nabhan, C. , Flinn, I. , Grinblatt, G.L. , Kozloff, M.F. , Farber, C.M. , Sullivan, K. , Street, T. , Swern, A.S. & Flowers, C.R. (2014a) Demographics by age group (AG) and line of therapy (LOT) in chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) patients (pts) treated in US practices from the Connect® CLL Registry. Blood, 124, 3338.25431474 [Google Scholar]

- Sharman, J.P. , Coutre, S.E. , Furma, R.R. , Cheson, B. , Pagel, J.M. , Hillmen, P. , Barrientos, J.C. , Zelenetz, A.D. , Kipps, T.J. , Flinn, I.W. , Ghia, P. , Hallek, M. , Coiffier, B. , O'Brien, S. , Tausch, E. , Kreuzer, K.A. , Jiang, W. , Lazarov, M. , Li, D. , Jahn, T.M. & Stilgenbauer, S. (2014b) Second interim analysis of a phase 3 study of idelalisib (ZYDELIG®) plus rituximab (R) for relapsed chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL): efficacy analysis in patient subpopulations with del(17p) and other adverse prognostic factors. Blood, 124, 330. [Google Scholar]

- Shenoy, P.J. , Malik, N. , Sinha, R. , Nooka, A. , Nastoupil, L.J. , Smith, M. & Flowers, C.R. (2011) Racial differences in the presentation and outcomes of chronic lymphocytic leukemia and variants in the United States. Clinical Lymphoma Myeloma and Leukemia, 11, 498–506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegel, R. , Ma, J. , Zou, Z. & Jemal, A. (2014) Cancer statistics, 2014. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians, 64, 9–29. Erratum in: (2014) CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians, 64, 364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith, A. , Howell, D. , Patmore, R. , Jack, A. & Roman, E. (2011) Incidence of haematological malignancy by sub‐type: a report from the Haematological Malignancy Research Network. British Journal of Cancer, 105, 1684–1692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, P.A. , Wierda, W.G. , Ferrajoli, A. , Smith, S. , O'Brien, S. , Burger, J.A. , Estrov, Z. , Jain, N. , Kantarjian, H.M. & Keating, M.J. (2014) Complex karyotype, rather than del(17p), is associated with inferior outcomes in relapsed or refractory CLL patients treated with ibrutinib‐based regimens. Blood, 124, 22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tucker, D.L. & Rule, S.A. (2015) A critical appraisal of ibrutinib in the treatment of mantle cell lymphoma and chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Therapeutics and Clinical Risk Management, 11, 979–990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table SI. Clinical characteristics at enrolment to the registry.

Table SII. Haematology variables at enrolment to the registry stratified by Rai stage.

Table SIII. HRQoL at enrolment to the registry as assessed by FACT‐Leu and FACT‐G.