Abstract

Cancer stem cells (CSCs) are thought to be responsible for tumor initiation, drug and radiation resistance, invasive growth, metastasis, and tumor relapse, which are the main causes of cancer‐related deaths. Gastrointestinal cancers are the most common malignancies and still the most frequent cause of cancer‐related mortality worldwide. Because gastrointestinal CSCs are also thought to be resistant to conventional therapies, an effective and novel cancer treatment is imperative. The first reported CSCs in a gastrointestinal tumor were found in colorectal cancer in 2007. Subsequently, CSCs were reported in other gastrointestinal cancers, such as esophagus, stomach, liver, and pancreas. Specific phenotypes could be used to distinguish CSCs from non‐CSCs. For example, gastrointestinal CSCs express unique surface markers, exist in a side‐population fraction, show high aldehyde dehydrogenase‐1 activity, form tumorspheres when cultured in non‐adherent conditions, and demonstrate high tumorigenic potential in immunocompromised mice. The signal transduction pathways in gastrointestinal CSCs are similar to those involved in normal embryonic development. Moreover, CSCs are modified by the aberrant expression of several microRNAs. Thus, it is very difficult to target gastrointestinal CSCs. This review focuses on the current research on gastrointestinal CSCs and future strategies to abolish the gastrointestinal CSC phenotype.

Keywords: Cancer stem cell, drug resistance, gastrointestinal cancer, neoplasm metastasis, phenotype of cancer stem cell

Gastrointestinal cancers encompass a variety of diseases, many of which have poor prognoses worldwide. Only CRC is listed in the top 10 for incidence rate of tumor; however, four gastrointestinal cancers, including colorectal, pancreatic, hepatic and biliary tract, and esophageal cancers, are in the top 10 for death rates from tumors in the USA.1 Additionally, there are four gastrointestinal carcinomas – colorectal, gastric, pancreatic, and hepatic carcinomas – in the top five for death rates in Japan.2

Combining several therapeutic approaches such as surgery, endoscopic therapy, chemotherapy, and radiation may improve survival in patients with gastrointestinal cancer. However, the effectiveness of these treatments depends on the cancer's status, specifically, on metastasis, resistance to radiation/chemotherapy, and recurrence, which are all thought to be caused by CSCs. Therefore, new therapeutic options for these diseases must be developed.

Cancer stem cells have been detected in several tumor types and might be important therapeutic targets. Cancer stem cells in solid tumors were first reported in the CD44+CD24−/low fraction of breast cancer.3 The first report of gastrointestinal CSCs was in the CD133+CD44+ALDH1+ fraction of CRC.4 Subsequently, gastrointestinal CSCs have been detected in cancers of esophagus, stomach, liver, and pancreas.5

Gastrointestinal CSCs express unique surface markers (e.g., CD24, CD26, CD44, CD90, CD133, and CD166),6, 7 exist in an SP fraction possessing increased Hoechst 33342 efflux capacity,6 show high ALDH1 activity,6 and form spheres when cultured in non‐adherent conditions (Table 1).6 Cancer stem cells also demonstrate high tumorigenic potential when xenografted into immunocompromised mice.3, 6

Table 1.

Representative unique markers of gastrointestinal cancer stem cells

| Tumor type | Representative unique markers | References |

|---|---|---|

| Colorectal cancer | CD133+/CD44+/ALDH1+ | Ricci‐Vitiani et al.4 |

| EpCAM+/CD44+, CD166+ | Dalerba et al.8 | |

| CD44+/CD24+ | Yeung et al.9 | |

| Lgr5+/GPR49+ | Vermeulen et al.10 | |

| Metastatic colon | CD133+/CD26+ | Pang et al.11 |

| Gastric cancer | CD44+ | Takaishi et al.12 |

| Liver cancer | CD133+/CD49f+ | Rountree et al.13 |

| CD90+/CD45− | Yang et al.14 | |

| CD13+ | Haraguchi et al.15 | |

| EpCAM+ | Kimura et al.16 | |

| Pancreatic cancer | CD133+/CD44+/CD24+/ESA+ | Li et al.17 |

| CXCR4+ | Hermann et al.18 | |

| Esophageal cancer | CD44+/ALDH1+ | Zhao et al.19 |

ALDH1, aldehyde dehydrogenase‐1; CXCR4, C‐X‐C chemokine receptor type 4; EpCAM, epithelial cell adhesion molecule; ESA, epithelial‐specific antigen; GPR, G‐protein coupled receptor; Lgr5, leucine‐rich repeat‐containing G‐protein‐coupled receptor 5.

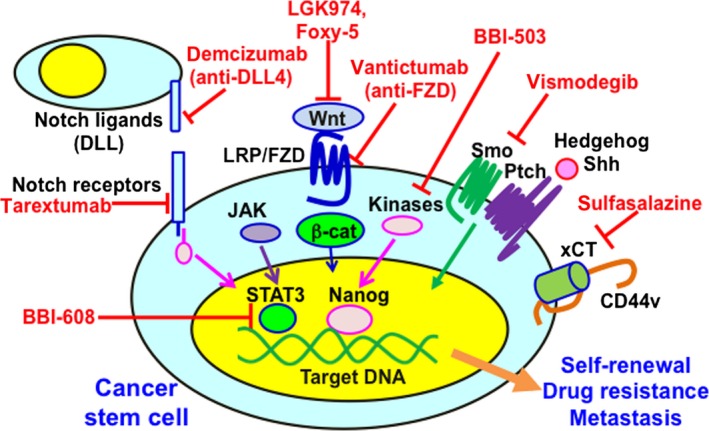

Cancer stem cells are thought to be derived from stem cells in normal adult tissue, their progenitors, and/or dedifferentiated mature cells.7 Hence, the signal transduction pathways in CSCs, which play important roles in self‐renewal, are similar to those involved in normal embryonic development. These include Wnt, Hedgehog, and Notch signals, in addition to pathways involving the polycomb group proteins (Fig. 1). Moreover, growth factors, such as fibroblast growth factor, TGF‐β, and insulin‐like growth factor‐1, might control the stemness of CSCs. Pro‐inflammatory cytokines (e.g., tumor necrosis factor‐α) could facilitate CSC generation, suggesting a possible link between CSCs and inflammation. Hypoxia also plays critical roles in the regulation of self‐renewal in normal cells and CSCs. The effects of hypoxia are mainly mediated by hypoxia‐inducible factors, particularly hypoxia‐inducible factor 2α. Cancer stem cells also show aberrant expression of several miRNAs, which could alter signal transduction pathways.20, 21 For example, overexpression of miR‐451 reduces colorectal CSC growth by inhibiting the Wnt signals, and miR‐34a suppresses pancreatic CSC growth by inhibiting the Notch signals (Table 2).

Figure 1.

Aberrant signal transduction pathways in cancer stem cells (CSCs) and therapeutic agents targeting CSCs. Signal transduction pathways in CSCs, which play important roles in self‐renewal, drug resistance, tumor recurrence, and distant metastasis, are being elucidated. Signaling pathways, including Notch, Wnt, and Hedgehog signaling, and downstream effectors, including the transcription factors β‐catenin (β‐cat), signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3), and Nanog, play key roles in CSC properties. After interaction with xCT, a CD44 variant (CD44v) enhanced capacity for gultathione synthesis and defense against reactive oxygen species. Due to this aberrant status, CSCs acquire the unique phenotype. The best way to eradicate CSCs is to identify the molecules responsible for the specific properties of CSCs, but not of normal cells. DLL, delta‐like ligand; FZD, Frizzled; JAK, Janus kinase; LRP, lipoprotein receptor‐related protein; Ptch, Patched; Shh, sonic Hedgehog; Smo, Smoothened.

Table 2.

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) regulating cancer stem cells from multiple cancers

| miRNA | Cancer type | Cell line/tissue sample | Expression in cancer stem cells | Target | Function |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| miR‐93 | Breast (basal) | HCC1954, SUM159, xenografts | Reduced | Many stem cell genes including SOX4 and STAT3 | Inhibits proliferation and metastasis |

| Breast (luminal) | MCF7, primary tumors | Increased | Does not affect the genes that it targets in basal breast cancer cell lines | Increases proliferation | |

| Colon | SW116 cell line | Reduced | HDAC8 and TLE4 (potential) | Inhibits proliferation | |

| miR‐200a | Ovarian | OVCAR3 cell line | Reduced | ZEB2 | Inhibits migration and invasion |

| Breast | Breast cancer tissues | Reduced | Not identified | Not known | |

| miR‐199a | Ovarian | Primary tumors, xenografts | Reduced | CD44 | Reduced tumor growth, reduced invasion, increased expression of stemness genes, increased chemosensitivity |

| miR‐199a‐3p | Hepatic | SNU449, primary HCC samples | Reduced | CD44 | Inhibits proliferation and invasion |

| miR‐199a‐2 | Ovarian | Ovarian ascites/ovarian cancer tissues | Reduced | IKKB | Induces apoptosis; increases chemosensitivity |

| miR‐34 | Glioma | Stem cell lines 0308 and 1228 | Reduced | Not identified | Induces differentiation |

| Prostate | Primary tumors, xenografts, prostate cancer cell lines | Reduced | CD44 | Inhibits metastasis and proliferation | |

| Pancreatic | MIAPaCa‐2, BxPC3 cell line, xenografts | Reduced | BCL2, NOTCH1 | Reduces tumorsphere formation | |

| let‐7 | Hepatic | HCC samples, HepG2, xenografts | Increased | SOCS1, CASP3 | Enhances chemoresistance |

| Breast | SkBr3, breast cancer samples | Reduced | HRAS, HMGA2 | Reduces mammosphere formation; inhibits differentiation | |

| miR‐451 | Colorectal | DLD1, LS513, colon cancer samples | Reduced | MIF | Wnt/β‐catenin signaling |

| miR‐106b | Gastric | MKN45, KATO III | Increased | Smad7 | TGF‐β/Smad signal activated |

| miR‐22 | Leukemia | MDS samples | Increased | TET2 | Promotion of self‐renewal |

| Breast | Breast cancer samples | Increased | TET family (TET1−3) | Suppression of miR‐200 family expression | |

| miR‐200 family | Breast | MDA‐MB‐435, BT‐549 | Reduced | ZEB1/ZEB2 I | Inhibition of EMT |

| Breast cancer samples | Reduced | BMI‐1 | Inhibition of self‐renewal | ||

| Breast cancer cell lines | Reduced | SUZ12 | Inhibition of mammosphere formation | ||

| miR‐193 | Breast, Colorectal | MDA‐MB‐231, HCT‐116, HT‐29 | Reduced | PLAU and K‐RAS | Inhibition of tumorigenicity and invasiveness |

EMT, epithelial–mesenchymal transition; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; MDS, myelodysplastic syndrome; TGF‐β, transforming growth factor‐β.

This review focuses on the recent developments in research on CSCs in gastrointestinal cancers. Understanding CSCs will be helpful for the development of novel therapeutic strategies and markers for gastrointestinal cancers.

Colorectal Cancer

It was first reported in 2007 that CRC cells expressing CD133 had a CSC phenotype.4, 22 Normal cells expressing Lgr5, a specific marker of intestinal stem cells, are converted into CSCs upon upregulation of the Wnt signals.23, 24, 25 Moreover, knockdown of Lgr5 could reduce tumorigenicity of CRC cells.26

CD44 or CD166 might be a promising marker of colon CSCs;4, 8, 9, 27 ALDH1, Lgr5, and EpCAM have also been used as CSC markers.28, 29 However, these are not the best markers to identify CSCs because they are also expressed in normal stem cells. Cancer stem cells but not normal intestinal stem cells, were identified to express Dclk1,25 which could be a unique marker for colon CSCs and could be used as a therapeutic target.

Epigenetic mechanisms are important regulators of CSCs. CD133 is directly regulated through promoter methylation,30 moreover, the DNA methylation of Lgr5 is implicated in CRC tumorigenesis.31 In addition, miRNAs inhibit the expression of stemness regulatory genes.32, 33

Cellular niches, a microenvironment formed by surrounding cells such as fibroblasts or vascular endothelial cells, play important roles in promoting and maintaining stemness in normal stem cells. Myofibroblasts promote the stemness of colon CSCs by secreting hepatocyte growth factor or collagen type I.34, 35 In addition, Jagged‐1, which is secreted from vascular endothelial cells, activates the Notch signalings and promotes the CSC phenotype in CRC.36

A method for generating CRC stem‐like cells from established CRC cell lines was reported.37 Briefly, induced pluripotent stem cells from CRC cells were retrovirally transfected with a set of defined factors (OCT3/4, SOX2, and KLF4) and these induced cells showed CSC properties. This method should facilitate research on colon CSCs and promote the establishment of new therapies targeting CSCs.

Pancreatic Cancer

The high rates of local tumor invasion, metastasis, and drug resistance in pancreatic cancer, for which CSCs are thought to be responsible, result in poor prognosis, poor survival rate, and high possibility of recurrence.

Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma is the most frequent histological type of pancreatic cancer. It is a complex genetic disease, and its progression requires the successive accumulation of several gene mutations including activated KRAS and inactivated CDKN2A, TP53, and SMAD4, which are already detectable in the premalignant lesions.

The representative cell surface markers used to isolate pancreatic CSCs are CD24+CD44+EpCAM+, CD133+, CXCR4+, and c‐Met+.17, 18, 38 An alternative technique for CSC identification in PDAC is based on enhanced ALDH1 activity and enhanced Hoechst 33342 efflux capacity. These marker‐positive cells show increased CSC phenotypes. A high population of SP cells and marker‐positive cells are also associated with poor prognosis in PDAC patients. However, specific universal markers for pancreatic CSCs have not been found.

Several signaling pathways are functional in pancreatic CSCs, for example, Hedgehog, Notch, Wnt, and phosphatidylinositol‐3 kinase/Akt (protein kinase B) signals. Inhibition of the Hedgehog signals decreased the pancreatic CSC phenotypes and tumorigenesis.39 Additionally, several miRNAs are important in the regulation of CSC phenotypes. MicroRNA‐21 and miR‐221 are overexpressed in PDAC, and their downregulation with antisense oligos results in decreased growth, metastasis, and chemoresistance.40, 41 High miR‐21 expression is also linked to poor prognosis in patients with PDAC. In contrast, the tumor suppressor miRNAs, miR‐34 and miR‐200a, are decreased in PDAC, and their restoration leads to inhibition of cancer properties.42, 43

Cancer stem cells are related to difficulties of targeting mutant KRAS in PDAC.44 Although KRAS ablation leads to tumor regression, a small population of PDAC cells acquired resistance to it and showed a high tumorigenic capacity with high CD44 and CD133 expressions.44 The CSC‐like cells that survived KRAS ablation had high mitochondrial activity and showed high sensitivity to oxidative phosphorylation inhibitors, leading to inhibition of tumorigenesis.

Liver Cancer

Primary liver cancers include two major histological types, HCC and intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma. Both diseases arise from bipotential hepatic progenitor cells that can differentiate into hepatocytes and cholangiocytes, whereas recent reports suggest that intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma arises through a process of transdifferentiation of hepatocytes into cholangiocytes.45 Limited cases of liver cancer with both phenotypes might support the former perspective. In this review, we describe the CSCs in HCC.

The liver has a remarkable regenerative capacity and there are two basic mechanisms of liver regeneration. During acute liver injuries, such as surgical removal, the remaining healthy hepatocytes replicate and restore liver function. In contrast, in chronic liver diseases, hepatic progenitor cells are induced and differentiate into hepatocytes or cholangiocytes. Because HCC generally develops following chronic liver disease and hepatic progenitor cell markers are often expressed in this process, hepatic progenitor cells are thought to be associated with hepatocarcinogenesis. Cancer stem cell phenotypes of HCC are inhibited by pharmacological blockage of the interleukin‐6 signalings, which is increased in chronic hepatitis, suggesting a relationship between chronic inflammation and HCC.46

Cell surface markers for isolating hepatic CSCs are CD13, CD24, CD44, CD90, CD133, oval cell marker OV6, and EpCAM.11, 12, 13, 47, 48, 49, 50 However, most of them are also expressed in normal hepatic progenitor cells. CD90+ and OV6+ cells have metastatic capacities, whereas CD13+, CD133+, CD24+, and EpCAM+ cells have chemoresistant capacities.51, 52 Moreover, metastatic CD90+ cells induce co‐injected non‐metastatic EpCAM+ cells to metastasize into the lung.53

The signaling pathways involved in hepatocarcinogenesis are p53, Akt, insulin‐like growth factor‐1 receptor, Wnt, TGF‐β, Notch, and Hedgehog. However, these signalings are also activated in normal liver development and chronic liver diseases. Furthermore, some of the cell surface markers used for isolating CSCs are involved in these signaling pathways. For example, EpCAM activates the Wnt signals, and CD24 is a STAT3‐mediated Nanog regulator, which leads to cell cycle signaling.47, 54 The class IV intermediate filament protein nestin regulates cellular plasticity and the tumorigenesis of liver CSCs in a p53‐dependent manner. Similarly, the transcription factor Twist2 regulates self‐renewal of liver CSCs in a CD24‐dependent manner.55, 56

In CD133+ HCC cells, miR‐130b, miR‐181, and let‐7 families are upregulated, whereas miR‐150 is downregulated, resulting in regulating phenotypes of cancer stemness. Increased levels of miR‐130b reduce the expression of its target tumor protein P53 inducible nuclear protein‐1, leading to self‐renewal and tumorigenesis,57 whereas inhibition of miR‐181 or let‐7 results in decreased motility and invasion capacity or increased chemosensitivity, respectively.58 Overexpression of miR‐150 significantly decreases the number of CD133+ liver CSCs.59

Esophageal Cancer

There are two main histological subtypes of esophageal cancer, ESCC and esophageal adenocarcinoma. The chemotherapy drugs used for the treatment of esophageal cancer are often combined with radiation either before or after surgery; however, conventional treatments are not really effective.

Esophageal CSCs were first separated as a single clone from an ESCC cell line.60 The ESCC cells harboring stem cell characteristics are more radioresistant than their parental cells. The SP cells in radioresistant esophageal cancer cells express high levels of β‐catenin, Oct3/4, and β1‐integrin.61 Recent studies described the relationship between the expression of miRNAs, for example, miR‐29662 and miR‐200c,63 and chemoresistance of ESCC.

Many genetic alterations are involved in esophageal tumorigenesis. Inhibition of PIK3CA reduces the proliferation of CSCs in ESCC. Phosphatidylinositol‐3 kinase inhibition was more effective in cells harboring a PIK3CA mutation than in control cells. Similarly, WNT10A‐overexpression increases self‐renewal capabilities and induces a larger population of CSCs, suggesting that WNT10A mediates migration and invasion in ESCC.64

Aldehyde dehydrogenase‐1, Lgr5, and CD44 are useful for sorting esophageal CSCs. Cancer cells with high CD44 expression show characteristics of EMT. Epidermal growth factor receptor plays a crucial role in EMT induction through TGF‐β. Epithelial–mesenchymal transition is critical for the generation of CSCs and epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitors could suppress EMT at the invasive front of ESCC.65

Gastric Cancer

The existence of CSCs in GC was first revealed by analyzing a panel of GC cell lines.10 Cancer stem cells from either GC cell lines or resected tumors were isolated using cell surface markers such as CD44 and EpCAM. Moreover, gastric CSCs can even be isolated from the peripheral blood of GC patients using CD44 and CD54.

Lgr5 is a gastric CSC marker and Lgr5+ stem cells in the stomach could be the origin of gastric CSCs.66 Patients with GC containing Lgr5+ cells have a short median survival.66 Helicobacter pylori infection triggers inflammation and changes the local gastric microenvironment, which changes might affect the differentiation of gastric stem cells and could induce GC. Helicobacter pylori colonizes and manipulates both progenitor and Lgr5+ stem cells, which then change gland turnover and cause hyperplasia.67

Gastric CSCs are thought to be derived from normal tissue stem cells. However, chronic infection with Helicobacter felis caused inflammation and induced the reconstruction of gastric tissue with bone marrow‐derived cells, whereas acute inflammation does not lead to bone marrow‐derived cell recruitment.68

Stem cells that express villin exist in the pyloric gland and villin+ gastric stem cells might be converted to GC cells.69 KLF4 might play a critical role in GC initiation and progression in villin+ gastric stem cells.69 In addition, ALDH1, CD90, CD71, and CD133 could be candidate markers of CSCs. MicroRNAs might regulate the properties of gastric CSCs by inducing EMT.70

Therapies Targeting Gastrointestinal CSCs

Many chemotherapeutic and biological agents have been developed against gastrointestinal cancers; however, they target the cells found in the bulk tumor and cannot efficiently remove CSCs, which leads to treatment failure, chemoresistance, and recurrence. Consequently, gastrointestinal cancer therapies targeting CSCs have been investigated (Table 3).

Table 3.

Target molecules and pathways for gastrointestinal cancer stem cells

| Target molecules/pathways | Taget tumors | Therapeutic agents | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Surface markers | CD133 | CRC, HCC | Oncolytic measles virus |

| CD44, xCT | GC, CRC | sulfasalazine | |

| CD90 | HCC | (not specific agents) | |

| Signaling pathways | Wnt/β‐catenin signaling | CRC, Solid tumors | LGK974, Foxy‐5, PRI‐724, vantictumab |

| Hedgehog signaling | CRC, Solid tumors, PDAC | vismodegib,sonidegib, cyclopamine | |

| Notch signaling | Metastatic CRC, PDAC | demcizumab, tarextumab, RO492909 | |

| NF‐κB signaling | GC, CRC | HGS1029, LCL161, GDC‐0152 | |

| PI3K/AKT signaling | CRC | idelalisib, temsirolimus, everolimus, dactolisib | |

| JAK/STAT signaling | GC, CRC, PDAC | napabucasin (BBI‐608), fedratinib, pacritinib | |

| Kinases | HCC, cholangiocarcinoma | amcasertib (BBI‐503) | |

| Microenvironment | VEGF/VEGF‐R | GC, CRC, PDAC | bevacizumab, cediranib, ziv‐aflibercept |

| CXCL12/CXCR4 | PDAC, CRC, Esophageal cancer | MSX‐122, LY2510924 | |

| Epigenetic system | Histone deacetylases | GC, CRC, PDAC | entinostat, vorinostat, mocetinostat, romidepsin, belinostat, panobinostat |

| EZH2 inhibitor | GC, CRC, HCC | tazemetostat (EPZ‐6438) | |

| micro RNAs | Almost all types of tumor | (not specific agents) | |

| Others | ABC transporters | GC, CRC, PDAC | zosuquidar, tariquidar, laniquidar |

| Immune‐mediated antitumor effect, insulin resistance | GC, CRC, PDAC, HCC | metformin | |

ABC, ATP‐binding cassette; CRC, colorectal cancer; CXCL1, chemokine (C‐X‐C motif) ligand 1; CRCR4, CXC chemokine receptor 4; EZH2, enhancer of zeste homolog 2; GC, gastric cancer; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; JAK, Janus‐activated kinase; NF‐κB, nuclear factor‐κB; PDAC, pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma; PI3K, phosphatidylinositol 3‐kinase; STAT, signal transducer and activator of transcription; VEGF, vascular endothelial growth factor; VEGF‐R, VEGF receptor.

Surface markers

An anti‐CD133 mAb possesses therapeutic potential against CRCs. An oncolytic measles virus retargeted to CD133 selectively eliminated CD133+ cells from a murine xenograft of both CRC and HCC.71

Sulfasalazine is an inhibitor for cystine/glutamate transporter xCT and suppresses the survival of CD44v‐positive CSCs.27 A phase I study of sulfapyridine given to patients with advanced GC reported that CD44v‐positive cancer cells and intratumoral glutathione levels were reduced in several patients.72

Signaling pathways

The Wnt signals play important roles in the regulation of CSCs. The small molecule LGK974 is an inhibitor of the O‐acyltransferase porcupine that acetylates Wnt proteins73 and is now under a phase I trial. Similarly, a Wnt‐5a‐mimicking hexapeptide Foxy‐5 was shown to impair migration and invasion74 and is currently under a phase I trial as a metastasis‐inhibiting agent for CRC.

Vismodegib is a small‐molecule inhibitor of Smoothened, which is a component of the Hedgehog signals. The Smoothened inhibitor cyclopamine inhibited the growth, invasion, and metastasis of PDAC.75

A phase I trial of Notch signaling blockade by the γ‐secretase inhibitor, RO492909, was effective against metastatic CRC.76 Humanized mAbs demcizumab (targeting Notch ligand, delta‐like‐4) and tarextumab (targeting the Notch‐2/3 receptors) were evaluated in combination with standard chemotherapy in phase II trials for metastatic PDAC. Although the YOSEMITE trial (demcizumab and gemcitabine plus protein‐bound paclitaxel) is still under estimation for PDAC, the ALPINE trial (tarextumab and gemcitabine plus protein‐bound paclitaxel) has been discontinued.77

Phase III trials are testing BBI‐608, an orally administered drug targeting STAT3, as a single agent for advanced CRC resistant to standard therapeutics (CO.23 trial)77 or in combination with weekly paclitaxel for advanced GC.77 Although the CO.23 trial was closed due to poor outcome, others with BBI‐608 are still under estimation, including a phase III study of BBI‐608 in combination with FOLFIRI with/without bevacizumab, which is a neutralizing antibody for vascular endothelial growth factor, for advanced CRC.77

A phase II study of BBI‐503, a small‐molecule inhibitor for Nanog and other CSC pathways, given as a single agent or in combination with anticancer therapeutics for advanced hepatic cancers.77

Others

Bevacizumab leads to normalization of tumor vasculature and specific inhibition of CSC growth.78 Antitumor drug efflux by ATP‐binding cassette transporters induces chemoresistance, which is one of the CSC phenotypes. Thus, agents targeting ATP‐binding cassette transporters have been developed and some of them have entered phase II/III clinical trials.

Metformin, a first‐line drug for diabetes, has been shown to decrease cancer incidence and mortality in population studies. Even though the mechanism remains unclear, studies have revealed an association between metformin and the number of CD133+ cells in various cancers.79

Discussion

Many markers for CSCs are also found on normal stem cells, which is a disadvantage in terms of their use as therapeutic targets. Thus, the best way to eradicate CSCs is to discover the molecules responsible for the peculiar properties of CSCs, but not of normal cells, such as Dclk1 in colorectal CSCs.25 Other reliable candidates would be variants of stem cell markers, such as CD44v8–10.27

Although the biological function of CSCs markers is often unclear, some relationship between CSC markers and biological CSC function was reported. After interactions with xCT, CD44v enhanced capacity for gultathione synthesis and defense against reactive oxygen species.27

Epithelial–mesenchymal transition is associated with carcinogenesis, invasion, metastasis, recurrence, and chemoresistance, which have been shown to be tightly linked with the function of CSCs. However, the direct relationship between CSCs and EMT in terms of molecular mechanisms remains to be elucidated. The EMT phenomenon and CSC properties might be promoted by common cellular signaling pathways, such as TGF‐β, Wnt/β‐catenin, Hedgehog, and Notch.

Conclusions

Most gastrointestinal tumors probably contain a small population of self‐renewing cells known as CSCs. As mentioned above, putative CSCs have been isolated from gastrointestinal tumors using either surface markers or ALDH1 activity. However, there is not sufficient evidence to determine the relationship among CSCs sorted by different methods. The tumorigenicity defined by CSC markers may not completely reflect their original cancer phenotype when cultured in a xenogeneic environment. A CSC population sorted by CSC markers has heterogeneity even in the same type of tumor.80 Moreover, there is no correlation between marker expression and tumorigenic potentiality in CSCs of the same cancer type obtained from different patients. Although the choice of CSC markers remains controversial, compelling evidence has shown that CSCs undeniably exist in various malignancies.

Anticancer therapies are usually evaluated on their ability to shrink tumors. If these therapies do not eliminate CSCs, a relapse could occur and CSCs could enable tumors to develop further resistance. The best way to eliminate gastrointestinal CSCs is to identify the specific markers for gastrointestinal CSCs, but not for normal cells. Targeted therapy against these specific molecules could offer new approaches to eradicate the malignant phenotypes of cancer without affecting normal stem cells.

Disclosure Statement

The authors have no conflict of interest.

Abbreviations

- ALDH1

aldehyde dehydrogenase‐1

- CRC

colorectal carcinoma

- CSC

cancer stem cell

- Dclk1

doublecortin‐like kinase‐1

- EMT

epithelial–mesenchymal transition

- EpCAM

epithelial cell adhesion molecule

- ESCC

esophageal squamous cell carcinoma

- KLF4

Kruppel‐like factor‐4

- GC

gastric cancer

- HCC

hepatocellular carcinoma

- Lgr5

leucine‐rich repeat containing G protein‐coupled receptor‐5

- miRNAs

microRNAs

- OCT‐3/4

octamer‐binding transcription factor‐3/4

- PDAC

pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma

- PIK3CA

phosphatidylinositol‐4,5‐bisphosphate 3‐kinase catalytic subunit α

- SOX2

sex‐determining region Y (SRY)‐related HMG‐box‐2

- SP

side population

- STAT3

signal transducer and activator of the transcription‐3

- TGF‐β

transforming growth factor‐β

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Department of Research Promotion, Practical Research for Innovative Cancer Control, Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare of Japan (H.T.).

Cancer Sci 107 (2016) 1556–1562

Funding Information

Department of Research Promotion, Practical Research for Innovative Cancer Control, Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare of Japan.

References

- 1. American‐Cancer‐Society . Cancer Facts & Figures 2016. http://www.cancer.org/acs/groups/content/@research/documents/document/acspc-047079.pdf

- 2. Center for Cancer Control and Information Services NCC, Japan . Cancer mortality (1958‐2014). http://ganjoho.jp/en/professional/statistics/table_download.html

- 3. Al–Hajj M, Wicha MS, Benito‐Hernandez A et al Prospective identification of tumorigenic breast cancer cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2003; 100: 3982–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ricci‐Vitiani L, Lombardi DG, Pilozzi E et al Identification and expansion of human colon‐cancer‐initiating cells. Nature 2007; 445: 111–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Mikhail S, Zeidan A. Stem cells in gastrointestinal cancers: the road less travelled. World J Stem Cells 2014; 6: 606–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Visvader JE, Lindeman GJ. Cancer stem cells in solid tumours: accumulating evidence and unresolved questions. Nat Rev Cancer 2008; 8: 755–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Garvalov BK, Acker T. Cancer stem cells: a new framework for the design of tumor therapies. J Mol Med 2011; 89: 95–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Dalerba P, Dylla SJ, Park IK et al Phenotypic characterization of human colorectal cancer stem cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2007; 104: 10158–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Yeung TM, Gandhi SC, Wilding JL et al Cancer stem cells from colorectal cancer‐derived cell lines. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2010; 107: 3722–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Vermeulen L, Todaro M, de Sousa Mello F et al Single‐cell cloning of colon cancer stem cells reveals a multi‐lineage differentiation capacity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2008; 105: 13427–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Pang R, Law WL, Chu AC et al A subpopulation of CD26+ cancer stem cells with metastatic capacity in human colorectal cancer. Cell Stem Cell 2010; 6: 603–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Takaishi S, Okumura T, Tu S et al Identification of gastric cancer stem cells using the cell surface marker CD44. Stem Cells 2009; 27: 1006–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Rountree CB, Senadheera S, Mato JM et al Expansion of liver cancer stem cells during aging in methionine adenosyltransferase‐1A‐deficient mice. Hepatology 2008; 47: 1288–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Yang ZF, Ho DW, Ng MN et al Significance of CD90+ cancer stem cells in human liver cancer. Cancer Cell 2008; 13: 153–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Haraguchi N, Ishii H, Mimori K et al CD13 is a therapeutic target in human liver cancer stem cells. J Clin Invest 2010; 120: 3326–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kimura O, Takahashi T, Ishii N et al Characterization of the epithelial cell adhesion molecule(EpCAM)+ cell population in hepatocellular carcinoma cell lines. Cancer Sci 2010; 101: 2145–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Li C, Heidt DG, Dalerba P et al Identification of pancreatic cancer stem cells. Cancer Res 2007; 67: 1030–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hermann PC, Huber SL, Herrler T et al Distinct populations of cancer stem cells determine tumor growth and metastatic activity in human pancreatic cancer. Cell Stem Cell 2007; 1: 313–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Zhao JS, Li WJ, Ge D et al Tumor initiating cells in esophageal squamous cell carcinomas express high levels of CD44. PLoS ONE 2011; 6: e21419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Sun X, Jiao X, Pestell TG et al MicroRNAs and cancer stem cells: the sword and the shield. Oncogene 2014; 33: 4967–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Chhabra R, Saini N. MicroRNAs in cancer stem cells: current status and future directions. Tumour Biol 2014; 35: 8395–405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. O'Brien CA, Pollett A, Gallinger S et al A human colon cancer cell capable of initiating tumour growth in immunodeficient mice. Nature 2007; 445: 106–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Barker N, van Es JH, Kuipers J et al Identification of stem cells in small intestine and colon by marker gene Lgr5. Nature 2007; 449: 1003–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Barker N, Ridgway RA, van Es JH et al Crypt stem cells as the cells‐of‐origin of intestinal cancer. Nature 2009; 457: 608–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Nakanishi Y, Seno H, Fukuoka A et al Dclk1 distinguishes between tumor and normal stem cells in the intestine. Nat Genet 2013; 45: 98–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Tsuji S, Kawasaki Y, Furukawa S et al The miR‐363‐GATA6‐Lgr5 pathway is critical for colorectal tumourigenesis. Nat Commun 2014; 5: 3150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ishimoto T, Nagano O, Yae T et al CD44 variant regulates redox status in cancer cells by stabilizing the xCT subunit of system xc(–) and thereby promotes tumor growth. Cancer Cell 2011; 19: 387–400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Huang EH, Hynes MJ, Zhang T et al Aldehyde dehydrogenase‐1 is a marker for normal and malignant human colonic stem cells(SC) and tracks SC overpopulation during colon tumorigenesis. Cancer Res 2009; 69: 3382–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Schepers AG, Snippert HJ, Stange DE et al Lineage tracing reveals Lgr5+ stem cell activity in mouse intestinal adenomas. Science 2012; 337: 730–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Yi JM, Tsai HC, Glockner SC et al Abnormal DNA methylation of CD133 in colorectal and glioblastoma tumors. Cancer Res 2008; 68: 8094–103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. de Sousa EMF, Colak S, Buikhuisen J et al Methylation of cancer‐stem‐cell‐associated Wnt target genes predicts poor prognosis in colorectal cancer patients. Cell Stem Cell 2011; 9: 476–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Chen J, Chen Y, Chen Z. MiR‐125a/b regulates the activation of cancer stem cells in paclitaxel–resistant colon cancer. Cancer Invest 2013; 31: 17–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Jones MF, Hara T, Francis P et al The CDX1‐microRNA‐215 axis regulates colorectal cancer stem cell differentiation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2015; 112: E1550–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Loeffler M, Kruger JA, Niethammer AG et al Targeting tumor–associated fibroblasts improves cancer chemotherapy by increasing intratumoral drug uptake. J Clin Invest 2006; 116: 1955–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Vermeulen L, De Sousa EMF, van der Heijden M et al Wnt activity defines colon cancer stem cells and is regulated by the microenvironment. Nat Cell Biol 2010; 12: 468–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Lu J, Ye X, Fan F et al Endothelial cells promote the colorectal cancer stem cell phenotype through a soluble form of Jagged–1. Cancer Cell 2013; 23: 171–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Oshima N, Yamada Y, Nagayama S et al Induction of cancer stem cell properties in colon cancer cells by defined factors. PLoS ONE 2014; 9: e101735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Li C, Wu JJ, Hynes M et al c–Met is a marker of pancreatic cancer stem cells and therapeutic target. Gastroenterology 2011; 141: 2218–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Petrova E, Matevossian A, Resh MD. Hedgehog acyltransferase as a target in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Oncogene 2015; 34: 263–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Park JK, Lee EJ, Esau C et al Antisense inhibition of microRNA–21 or –221 arrests cell cycle, induces apoptosis, and sensitizes the effects of gemcitabine in pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Pancreas 2009; 38: e190–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Moriyama T, Ohuchida K, Mizumoto K et al MicroRNA–21 modulates biological functions of pancreatic cancer cells including their proliferation, invasion, and chemoresistance. Mol Cancer Ther 2009; 8: 1067–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Ji Q, Hao X, Zhang M et al MicroRNA miR–34 inhibits human pancreatic cancer tumor–initiating cells. PLoS ONE 2009; 4: e6816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Lu Y, Lu J, Li X et al MiR–200a inhibits epithelial–mesenchymal transition of pancreatic cancer stem cell. BMC Cancer 2014; 14: 85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Viale A, Pettazzoni P, Lyssiotis CA et al Oncogene ablation–resistant pancreatic cancer cells depend on mitochondrial function. Nature 2014; 514: 628–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Sekiya S, Suzuki A. Intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma can arise from Notch–mediated conversion of hepatocytes. J Clin Invest 2012; 122: 3914–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Wan S, Zhao E, Kryczek I et al Tumor‐associated macrophages produce interleukin‐6 and signal via STAT3 to promote expansion of human hepatocellular carcinoma stem cells. Gastroenterology 2014; 147: 1393–404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Lee TK, Castilho A, Cheung VC et al CD24(+)liver tumor–initiating cells drive self–renewal and tumor initiation through STAT3–mediated NANOG regulation. Cell Stem Cell 2011; 9: 50–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Ma S, Chan KW, Hu L et al Identification and characterization of tumorigenic liver cancer stem/progenitor cells. Gastroenterology 2007; 132: 2542–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Yang W, Wang C, Lin Y et al OV6 + tumor–initiating cells contribute to tumor progression and invasion in human hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol 2012; 57: 613–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Yamashita T, Ji J, Budhu A et al EpCAM–positive hepatocellular carcinoma cells are tumor–initiating cells with stem/progenitor cell features. Gastroenterology 2009; 136: 1012–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Yamashita T, Wang XW. Cancer stem cells in the development of liver cancer. J Clin Invest 2013; 123: 1911–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Yamashita T, Kaneko S. Orchestration of hepatocellular carcinoma development by diverse liver cancer stem cells. J Gastroenterol 2014; 49: 1105–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Yamashita T, Honda M, Nakamoto Y et al Discrete nature of EpCAM+ and CD90+ cancer stem cells in human hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology 2013; 57: 1484–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Yamashita T, Budhu A, Forgues M et al Activation of hepatic stem cell marker EpCAM by Wnt‐beta‐catenin signaling in hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Res 2007; 67: 10831–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Tschaharganeh DF, Xue W, Calvisi DF et al p53–dependent Nestin regulation links tumor suppression to cellular plasticity in liver cancer. Cell 2014; 158: 579–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Liu AY, Cai Y, Mao Y et al Twist2 promotes self–renewal of liver cancer stem–like cells by regulating CD24. Carcinogenesis 2014; 35: 537–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Ma S, Tang KH, Chan YP et al miR–130b Promotes CD133(+) liver tumor–initiating cell growth and self–renewal via tumor protein 53–induced nuclear protein‐1. Cell Stem Cell 2010; 7: 694–707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Ji J, Yamashita T, Budhu A et al Identification of microRNA–181 by genome–wide screening as a critical player in EpCAM–positive hepatic cancer stem cells. Hepatology 2009; 50: 472–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Zhang J, Luo N, Luo Y et al microRNA–150 inhibits human CD133–positive liver cancer stem cells through negative regulation of the transcription factor c–Myb. Int J Oncol 2012; 40: 747–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Ban S, Ishikawa K, Kawai S et al Potential in a single cancer cell to produce heterogeneous morphology, radiosensitivity and gene expression. J Radiat Res 2005; 46: 43–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Zhang X, Komaki R, Wang L et al Treatment of radioresistant stem–like esophageal cancer cells by an apoptotic gene–armed, telomerase–specific oncolytic adenovirus. Clin Cancer Res 2008; 14: 2813–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Hong L, Han Y, Zhang H et al The prognostic and chemotherapeutic value of miR–296 in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Ann Surg 2010; 251: 1056–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Hamano R, Miyata H, Yamasaki M et al Overexpression of miR–200c induces chemoresistance in esophageal cancers mediated through activation of the Akt‐signaling pathway. Clin Cancer Res 2011; 17: 3029–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Long A, Giroux V, Whelan KA et al WNT10A promotes an invasive and self–renewing phenotype in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Carcinogenesis 2015; 36: 598–606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Sato F, Kubota Y, Natsuizaka M et al EGFR inhibitors prevent induction of cancer stem–like cells in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma by suppressing epithelial–mesenchymal transition. Cancer Biol Ther 2015; 16: 933–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Barker N, Huch M, Kujala P et al Lgr5(+ve)stem cells drive self–renewal in the stomach and build long–lived gastric units in vitro . Cell Stem Cell 2010; 6: 25–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Sigal M, Rothenberg ME, Logan CY et al Helicobacter pylori activates and expands Lgr5+ stem cells through direct colonization of the gastric glands. Gastroenterology 2015; 148: 1392–404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Houghton J, Stoicov C, Nomura S et al Gastric cancer originating from bone marrow‐derived cells. Science 2004; 306: 1568–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Li Q, Jia Z, Wang L et al Disruption of Klf4 in villin–positive gastric progenitor cells promotes formation and progression of tumors of the antrum in mice. Gastroenterology 2012; 142: 531–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Link A, Kupcinskas J, Wex T et al Macro‐role of microRNA in gastric cancer. Dig Dis 2012; 30: 255–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Bach P, Abel T, Hoffmann C et al Specific elimination of CD133+ tumor cells with targeted oncolytic measles virus. Cancer Res 2013; 73: 865–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Shitara K, Doi T, Nagano O et al Dose‐escalation study for the targeting of CD44v+cancer stem cells by sulfasalazine in patients with advanced gastric cancer (EPOC1205). Gastric Cancer 2016. doi: 10.1007/s10120‐016‐0610‐8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Liu J, Pan S, Hsieh MH et al Targeting Wnt–driven cancer through the inhibition of Porcupine by LGK974. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2013; 110: 20224–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Safholm A, Tuomela J, Rosenkvist J et al The Wnt–5a–derived hexapeptide Foxy–5 inhibits breast cancer metastasis in vivo by targeting cell motility. Clin Cancer Res 2008; 14: 6556–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Feldmann G, Dhara S, Fendrich V et al Blockade of hedgehog signaling inhibits pancreatic cancer invasion and metastases: a new paradigm for combination therapy in solid cancers. Cancer Res 2007; 67: 2187–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. LoConte NK, Razak AR, Ivy P et al A multicenter phase‐1 study of gamma–secretase inhibitor RO4929097 in combination with capecitabine in refractory solid tumors. Invest New Drugs 2015; 33: 169–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. ClinicalTrials.gov . https://clinicaltrials.gov/

- 78. Zhao D, Pan C, Sun J et al VEGF drives cancer‐initiating stem cells through VEGFR‐2/Stat3 signaling to upregulate Myc and Sox2. Oncogene 2015; 34: 3107–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Lee MS, Hsu CC, Wahlqvist ML et al Type‐2 diabetes increases and metformin reduces total, colorectal, liver and pancreatic cancer incidences in Taiwanese: a representative population prospective cohort study of 800,000 individuals. BMC Cancer 2011; 11: 20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Di J, Yigit R, Figdor CG et al Expression compilation of several putative cancer stem cell markers by primary ovarian carcinoma. J Cancer Ther 2010; 1: 165–73. [Google Scholar]