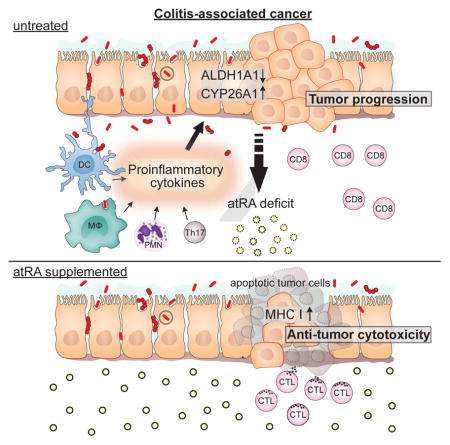

Summary

Although all-trans retinoic acid (atRA) is a key regulator of intestinal immunity, its role in colorectal cancer (CRC) is unknown. We found that mice with colitis-associated CRC had a marked deficiency in colonic atRA due to alterations in atRA metabolism mediated by microbiota-induced intestinal inflammation. Human ulcerative colitis (UC), UC-associated CRC, and sporadic CRC specimens have similar alterations in atRA metabolic enzymes, consistent with reduced colonic atRA. Inhibition of atRA signaling promoted tumorigenesis whereas atRA supplementation reduced tumor burden. The benefit of atRA treatment was mediated by cytotoxic CD8+ T cells, activated due to MHCI upregulation on tumor cells. Consistent with these findings, increased colonic expression of the atRA-catabolizing enzyme, CYP26A1, correlated with reduced frequencies of tumoral cytotoxic CD8+ T cells and with worse disease prognosis in human CRC. These results reveal a mechanism by which microbiota drive colon carcinogenesis and highlight atRA metabolism as a therapeutic target for CRC.

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the second leading cause of cancer mortality in the U.S. (Haggar and Boushey, 2009), and ulcerative colitis (UC), a chronic inflammatory condition of the colon, has been shown to predispose individuals to CRC (Ullman and Itzkowitz, 2011). Despite advances in therapy, however, 20–30% of UC patients still undergo colectomy because they are refractory to current therapy or because they have developed CRC. Unfortunately, surgery is often associated with significant postoperative morbidities (Biondi et al., 2012). Thus, there remains an urgent need for improved therapy and effective chemoprophylaxis in UC and UC-associated cancer.

The vitamin A metabolite all-trans retinoic acid (atRA) is required for several crucial physiological processes (Clagett-Dame and DeLuca, 2002; Mark et al., 2006; Obrochta et al., 2015). In recent years, atRA has been shown to regulate both the innate and adaptive immune systems and, in particular, to play a requisite role in shaping intestinal immunity (Cassani et al., 2012; Hall et al., 2011b). atRA maintains immune homeostasis in the intestinal lamina propria mainly by potentiating the induction and maintenance of regulatory T-cells and reciprocally inhibiting the development of Th17 cells (Benson et al., 2007; Cassani et al., 2012; Coombes et al., 2007; Mucida et al., 2007). Additionally, in certain pathological settings, atRA can also elicit proinflammatory effector T-cell responses (Allie et al., 2013; Guo et al., 2014; Guo et al., 2012; Hall et al., 2011a). However, despite the critical influence of atRA on intestinal immunity, its role in CRC has not been previously investigated.

We hypothesized that a local deficiency of atRA might promote the development of CRC, especially in the context of intestinal inflammation. Therefore, we studied atRA metabolism in colitis-associated CRC. Our findings reveal a link between microbiota-induced intestinal inflammation, atRA deficiency, and CRC in mice and humans, as well as a strong anti-tumor effect of atRA mediated through CD8+ effector T-cells.

Results

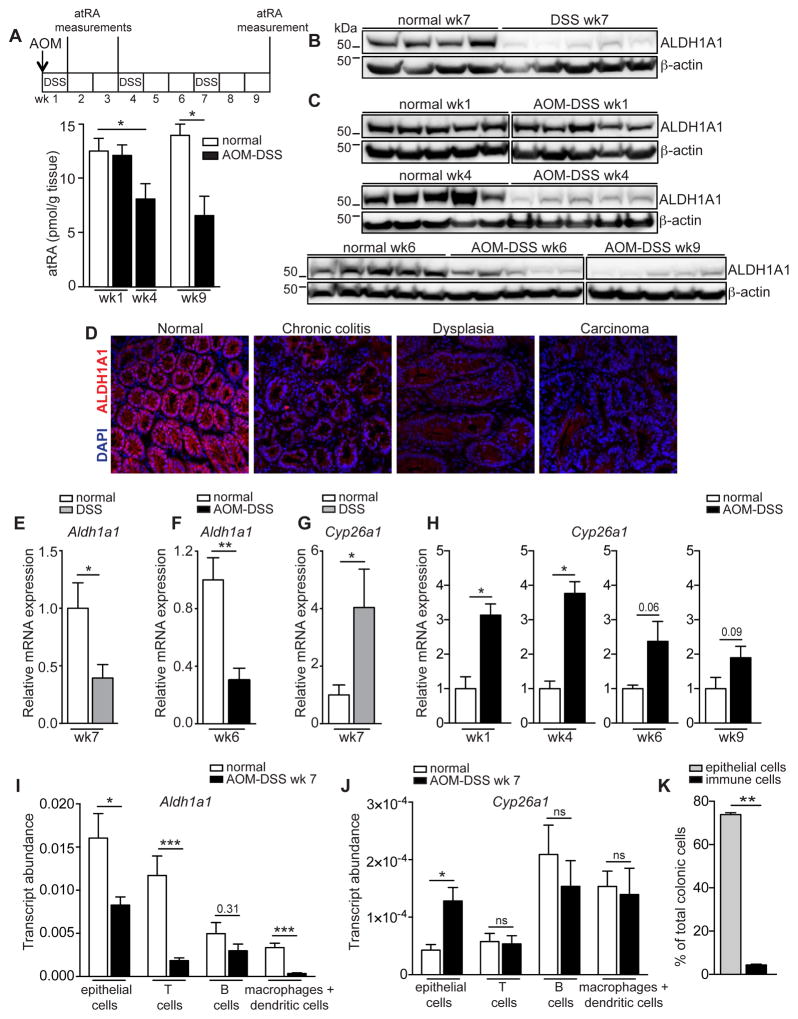

Mice with colitis-associated cancer are deficient in colonic atRA due to altered atRA metabolism

To investigate the role of atRA metabolism in CRC development, we used a mouse model that recapitulates progression from colitis to cancer: the AOM-DSS model (Tanaka et al., 2003). In this model, the colonotropic carcinogen azoxymethane (AOM) is combined with the inflammatory agent dextran sodium sulfate (DSS) to induce chronic intestinal inflammation and tumor formation in the distal colons of mice within nine to ten weeks, with dysplasia appearing as early as week three. In contrast, mice administered DSS alone develop chronic colitis without tumorigenesis (Wirtz et al., 2007).

In line with our hypothesis that a local deficiency of atRA might promote the development of CRC, colonic atRA levels, as measured by quantitative mass spectrometry, were significantly reduced in mice with colitis-associated cancer (CAC) as early as four weeks after AOM-DSS induction, when mice had chronic inflammation with dysplastic changes in the colon. atRA levels further declined to approximately half the normal colonic atRA level by week nine, when carcinomas became apparent (Figure 1A and Figure S1A). To investigate whether this deficiency could result from altered expression of atRA metabolic enzymes, we analyzed the colonic expression of key enzymes that function in the synthesis of atRA—the retinaldehyde dehydrogenases, ALDH1A1, ALDH1A2, and ALDH1A3—and the catabolism of atRA—the cytochrome p450 (CYP) family members, CYP26A1, CYP26B1, and CYP26C1—during progression from colitis to cancer. Because ALDH1A1 is the most abundantly expressed ALDH1A isoform in the normal mouse colon (data not shown), and CYP26A1 is the most catalytically active of the three CYP26 enzymes (Kedishvili, 2013), we focused our analyses on these enzymes. Colonic ALDH1A1 protein expression declined in mice with chronic colitis and in mice with CAC throughout disease progression, ultimately decreasing by 50–70% compared to age-matched normal mice (Figure 1B–D and Figure S1B,C). This reduction was also observed at the transcript level (Figure 1E,F). ALDH1A2 protein expression remained unchanged (Figure S1D), whereas ALDH1A3 was consistently decreased during disease progression (Figure S1E).

Figure 1. AOM-DSS mice have a deficiency in colonic atRA that can be attributed to alterations in atRA metabolism.

(A) Mass spectrometry measurements of colonic atRA concentrations in AOM-DSS mice throughout disease progression compared to normal age-matched mice (n=3–5 mice per group). (B,C) Immunoblots for ALDH1A1 in distal colonic lysates of mice with chronic colitis (DSS wk7) (B), and of AOM-DSS mice at different time points throughout disease progression (C), compared to normal age-matched mice (n=5 mice per group). Representative of 2 independent experiments. Cropped immunoblots were taken from different parts of the same gel and are indicated by demarcation lines. (D) Immunofluorescence staining of ALDH1A1 (red) in colonic tissue sections throughout disease progression, from steady state to colitis (DSS-treated), dysplasia and carcinoma. Scale bar=50 μm. (n=5 mice per group). (E–H) qRT-PCR measurements of Aldh1a1 (E,F) and Cyp26a1 (G,H), relative to Gapdh, in distal colons of mice treated with DSS (E,G) or AOM-DSS (F,H) compared to normal age-matched mice (n=4–5 mice per group). Representative of 3 independent experiments. (I, J) qRT-PCR measurements of Aldh1a1 (I) and Cyp26a1 (J), relative to Gapdh, in different cell types sorted from AOM-DSS and normal age-matched mice (n=5 mice per group). (K) Flow cytometry data showing the frequencies of different cell types in distal colons of AOM-DSS mice (n=5 mice per group). Results are represented as mean ± SEM. p<0.05=*; p<0.01=**; p<0.001=***, Mann Whitney U-test. See also Figure S1.

In contrast to the atRA synthesis enzymes, the colonic transcript levels of the atRA catabolizing enzyme CYP26A1 were increased four-fold in mice with chronic colitis (Figure 1G), and three-to eight-fold (depending on the CYP26 isoform) in mice with CAC. Upregulation was observed as early as one week after AOM-DSS induction, with levels declining thereafter (Figure 1H and Figure S1F,G).

We next sought to partition out the contribution of various cell types to the colonic atRA deficiency. Although Aldh1a1 expression was reduced in colonic epithelial cells, T-cells, and macrophages or dendritic cells in CAC mice (Figure 1I), Cyp26a1 expression was increased only in the epithelial compartment (Figure 1J). Given the relative abundance of epithelial cells compared to immune cells (Figure 1K) and the observation that epithelial cells exhibit alterations in both Aldh1a1 and Cyp26a1, the atRA deficiency observed in colitis or CAC can largely be attributed to the epithelial cells. Taken together, these findings indicate that mice with CAC have a marked decrease in colonic atRA as a result of a decrease in the atRA-synthesizing ALDH1A enzymes and an increase in the atRA-catabolizing CYP26 enzymes.

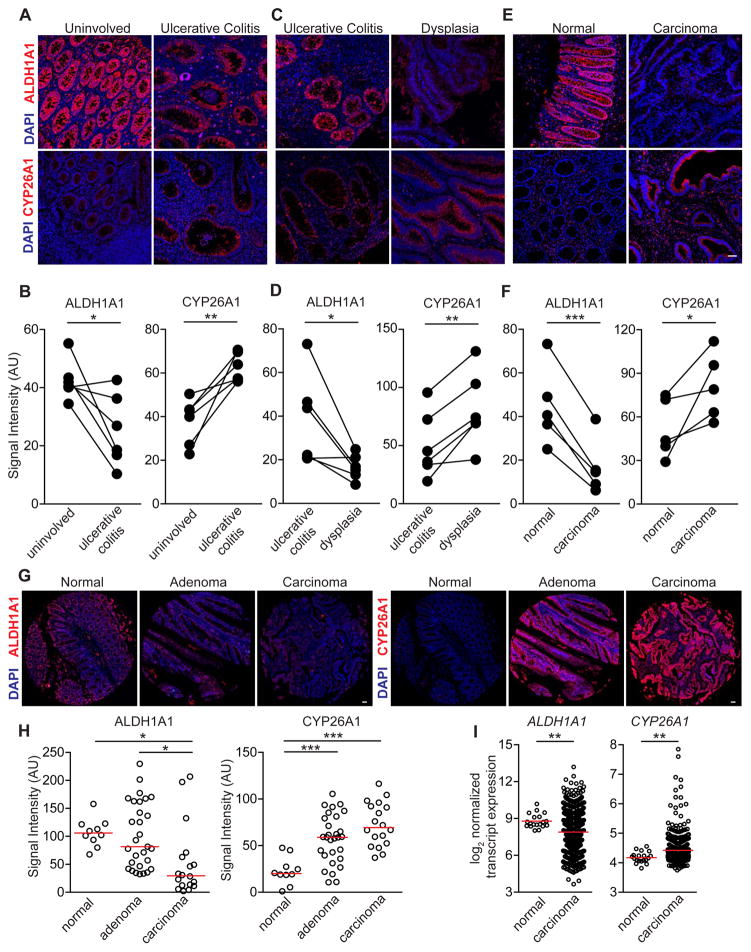

Abnormal atRA metabolism is a common feature of ulcerative colitis and colorectal cancer in humans

To assess whether atRA deficiency is present in UC-associated CRC, we examined the expression of ALDH1A1 and CYP26A1 in colonic resections from UC and UC-associated CRC patients. In specimens from UC patients, there was a significant decrease in ALDH1A1 and a corresponding increase in CYP26A1 in colitis regions compared to matched uninvolved regions of tissue (Figure 2A,B) and in dysplastic tissue compared to matched colitis tissue (Figure 2C,D). ALDH1A1 and CYP26A1 were also lower and higher, respectively, in colon adenocarcinomas compared to matched normal regions (Figure 2E,F). Using a tissue microarray, we found that the same ALDH1A1 and CYP26A1 differential expression was conserved in sporadic adenocarcinomas compared to normal colons and adenomas (Figure 2G,H). Transcript expression of ALDH1A1 was also decreased and CYP26A1 increased in colon cancer specimens from an independent microarray dataset, GSE39582 (Figure 2I) (Marisa et al., 2013).

Figure 2. Human UC, UC-associated dysplasia and sporadic colon adenocarcinoma exhibit abnormal expression of colonic atRA metabolizing enzymes.

(A,C,E,G) Representative immunofluorescence images of ALDH1A1 and CYP26A1 (red) on matched human UC and uninvolved colonic resections (n=6 samples) (A), matched human UC and dysplastic colonic resections (n=6 samples) (C), matched adenocarcinoma and normal colonic resections (n=5 samples) (Scale bar=50 μm) (E), and on a sporadic adenoma and carcinoma tissue microarray (G) (Scale bar=1 mm). (B,D,F,H) Average staining intensity values (in arbitrary units (AU)) of ALDH1A1 and CYP26A1 in the colonic epithelium, acquired from a minimum of 3 image fields, of all samples in (A,C,E,G). (I) Transcript expression of ALDH1A1 and CYP26A1 from the gene expression microarray dataset GSE39582. Paired-t-test (B,D,F) and one-way ANOVA test (H), p<0.05=*; p<0.01=**; p<0.001=***.

These findings show that patients with sporadic CRC, UC and UC-associated CRC have similar alterations in atRA metabolism in affected tissues, consistent with the reduced colonic levels of atRA observed in the mouse model of CAC.

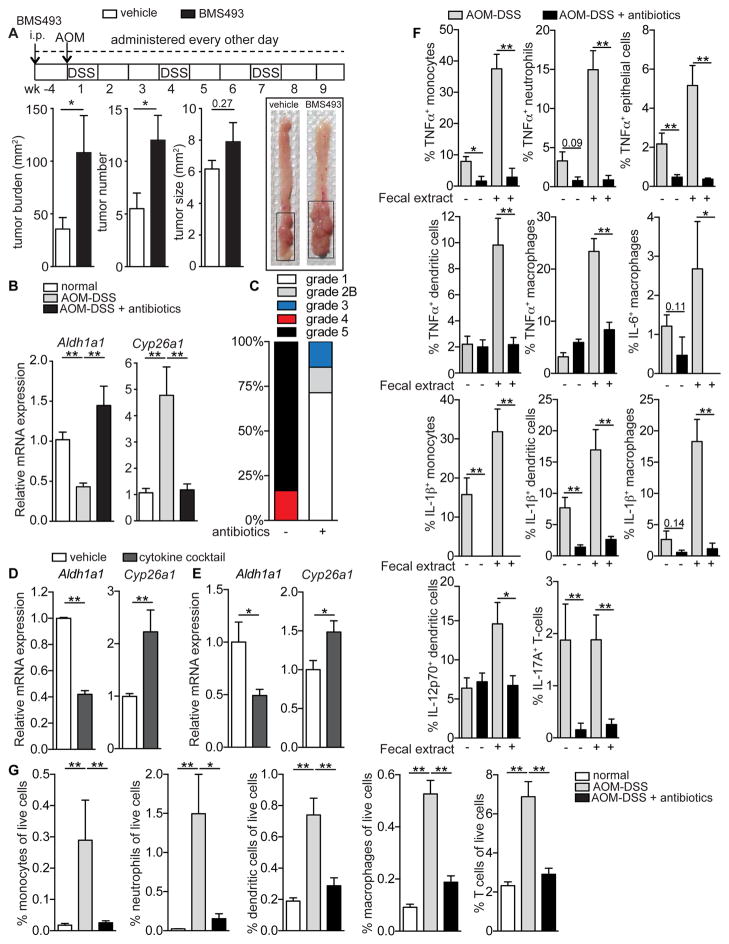

Inflammation triggered by intestinal microbiota induces atRA enzyme alteration in mice with CAC

To investigate whether atRA deficiency can exacerbate CRC tumorigenesis, we treated mice with the pan-retinoic acid receptor (RAR) inverse agonist BMS493 (Germain et al., 2009) four weeks prior to and throughout disease progression following AOM-DSS induction. This treatment led to a significant increase in tumor burden (Figure 3A), compelling us to investigate the mechanism responsible for the atRA enzyme deregulation observed in mice with CAC. Several investigators have demonstrated the pro-tumorigenic effects of intestinal microbiota in CRC (Arthur et al., 2012; Couturier-Maillard et al., 2013; Hu et al., 2013), with broad-spectrum antibiotics dramatically reducing tumor incidence in animal models of CRC, including the AOM-DSS model (Grivennikov et al., 2012; Zackular et al., 2013). We therefore hypothesized that bacterial influx into the colon, due to defective barrier permeability, could induce colonic atRA enzyme alteration in the context of colitis and CRC. In accord with our hypothesis, pretreatment with broad-spectrum antibiotics completely prevented both the decrease in Aldh1a1 and increase in Cyp26a1 in mice with CAC (Figure 3B and Figure S2A,B). Antibiotic-treated AOM-DSS mice also exhibited significantly increased body weights and dramatically reduced tumor burdens compared to untreated AOM-DSS mice (Figure S2C,D).

Figure 3. Inflammation triggered by intestinal microbiota induces atRA enzyme alteration in AOM-DSS mice.

(A) Tumor analyses in AOM-DSS mice treated with the pan-retinoic acid receptor inhibitor (BMS493) compared to vehicle-treated mice. Also shown are representative images of the colons. Data are pooled from 2 independent experiments (n=7–8 mice). (B) qRT-PCR measurements of Aldh1a1 and Cyp26a1, normalized to Gapdh, in the distal colons of normal age-matched mice and untreated or antibiotic-treated AOM-DSS mice (n=5–6 mice per group). Representative of 2 independent experiments. (C) Colitis score grading of antibiotic-treated or untreated AOM-DSS mice (n=5 mice per group). (D) qRT-PCR measurements of Aldh1a1 and Cyp26a1 from intestinal organoids cultured in vitro with a proinflammatory cytokine mixture compared to vehicle. Data are pooled from 3 independent experiments. (E) qRT-PCR measurements of Aldh1a1 and Cyp26a1 from distal colons of antibiotic-treated mice injected intramucosally with a proinflammatory cytokine mixture or vehicle (n=8–10 mice per group). (F) Flow cytometry data showing the percentage of specific cell populations from the distal colons of untreated or antibiotic-treated AOM-DSS mice expressing different cytokines induced via stimulation with fecal extract (n=5 mice per group). (G) Quantitation of the frequency of different immune cells in the distal colons of normal age-matched mice and untreated or antibiotic-treated AOM-DSS mice (n=5 mice per group). Results are represented as mean ± SEM. p<0.05=*; p<0.01=**; p<0.001=***, Mann Whitney U-test. See also Figure S2.

Having demonstrated that atRA enzymes are altered not only in CAC but also during chronic colitis (Figure 1), we hypothesized that inflammation driven by gut microbiota could contribute to the altered enzyme expression. In line with our hypothesis, the colons of antibiotic-treated AOM-DSS mice not only had healthier colitis scores compared to untreated AOM-DSS mice (Figure 3C and Figure S2E), but also showed a striking reduction in the expression of several proinflammatory cytokines (TNFα, IFNγ, IL-1β, IL-17A, IL-12, IL-6 and IL-23) (Figure S2F). To test whether these proinflammatory cytokines could be altering atRA enzymes in colitis or CAC, we asked whether culturing epithelial organoids with these cytokines, or whether injecting these cytokines into the mucosal wall of the distal colon of antibiotic-treated mice (Figure S2G), could alter the expression of Aldh1a1 and Cyp26a1. In both contexts, the proinflammatory cytokines induced a significant decrease in Aldh1a1 and increase in Cyp26a1 (Figure 3D,E).

Next, we investigated the cell types responsible for secreting the various proinflammatory cytokines in the colons of mice with CAC. The myeloid compartment secreted a wide range of these cytokines, including TNFα, IL-1β, IL-6 and IL-12, while the epithelial cells secreted TNFα and T-cells secreted IL-17A (Figure 3F and Figure S2H). Antibiotic treatment not only markedly reduced cytokine secretion from all these cell types, but also substantially reduced immune cell infiltration into the colon (Figure 3F,G and Figure S2H). These results show that expression of the atRA metabolic enzymes is altered by inflammatory cytokines released from colonic epithelial cells and infiltrating immune cells in response to the influx of gut microbiota across a defective mucosal barrier.

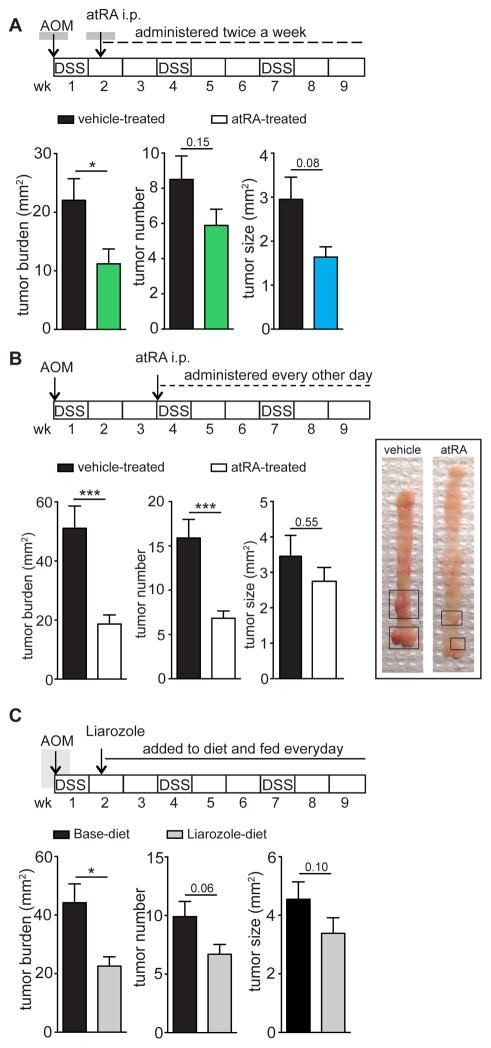

atRA supplementation decreases tumor burden in mice with CAC

Given the altered atRA metabolism in AOM-DSS mice as well as in human CRC, we assessed whether treatment with atRA could decrease tumor burden. We used two distinct methods for this purpose: 1) intraperitoneal injection of atRA and 2) oral administration of Liarozole, an inhibitor of the CYP26 enzymes that catabolize atRA (Van Wauwe et al., 1990). Liarozole’s ability to increase available endogenous atRA was demonstrated in vitro using RARE-luciferase assays (Figure S3A,B) on two colon cancer cell lines, MC38 and CT26, and in vivo via mass spectrometry of colons of AOM-DSS mice orally gavaged with Liarozole (Figure S3C). atRA was administered to AOM-DSS mice either starting early, when acute colitis was established, or later, after dysplastic changes had occurred in the colon. In both cases, tumor burden in atRA-treated mice was reduced by more than half compared to vehicle-treated mice (Figure 4A,B). Consistent with atRA treatment, Liarozole treatment also resulted in a 50% reduction in tumor burden (Figure 4C). These data demonstrate a robust therapeutic benefit conferred by atRA supplementation.

Figure 4. atRA supplementation decreases tumor burden in AOM-DSS mice.

(A,B) Graphs represent tumor analyses in AOM-DSS mice treated with 200μg atRA twice a week starting from day 10 (A) or every other day from week 4 (B) after disease induction compared to vehicle-treated mice. Representative image of mouse colons from (B). Data represent pooled data from 2 independent experiments with n=10 mice per group in (A) and n=9–13 mice in (B). (C) Tumor analyses in AOM-DSS mice fed with a diet containing Liarozole compared to a control base diet from day 10 after disease induction. Representative of 3 independent experiments (n=10 mice per group). Results are represented as mean ± SEM with p<0.05=*; p<0.01=**; p<0.001=***, Mann Whitney U-test. See also Figure S3.

atRA treatment elicits a pronounced CD8+ T-cell response in mice with CAC

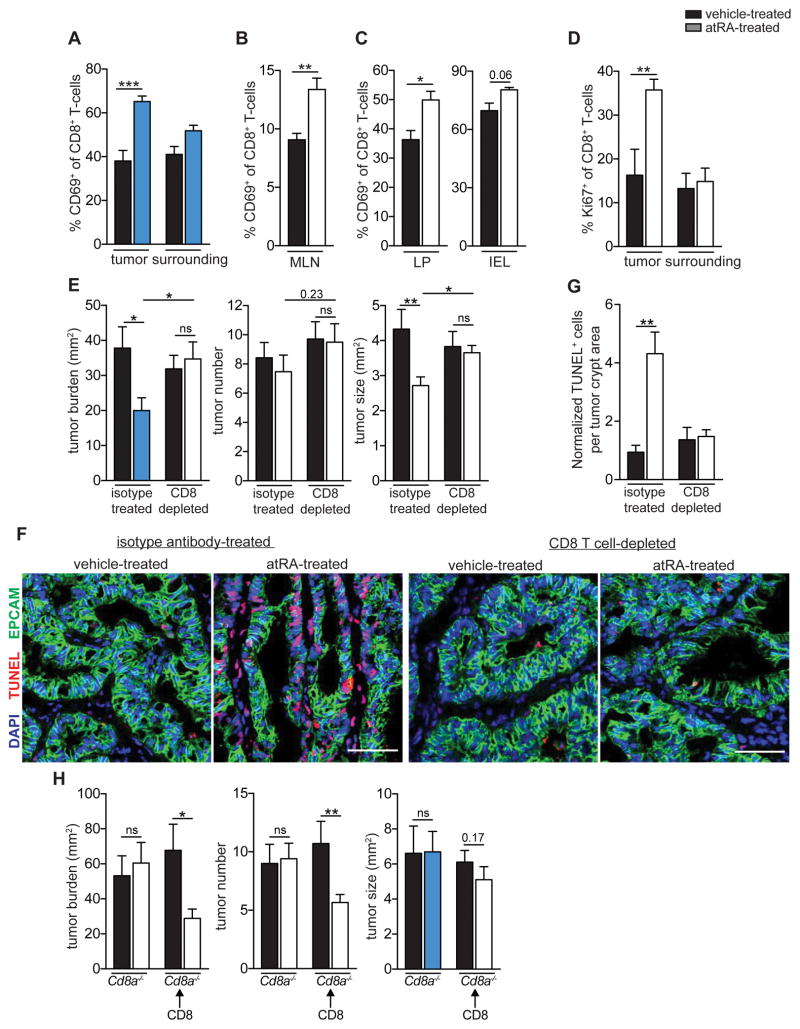

Next, we sought to identify the mechanism responsible for the anti-tumor effect of atRA. Since CD8+ T-cells play a crucial role in anti-tumor immunity, we examined the CD8+ T-cell response in AOM-DSS mice treated with atRA. A significant increase in the percentage of CD8+ T-cells expressing the early activation marker CD69 was seen in tumors and MLNs in atRA-treated mice (Figure 5A,B and Figure S4A). The atRA-mediated increase in activated CD8+ T-cells was more pronounced in the lamina propria (LP) than the intra-epithelial lymphocyte (IEL) layer of the tumor (Figure 5C). In addition, the percentage of proliferating intratumoral CD8+ T-cells nearly doubled in atRA-treated mice (Figure 5D). Thus, a robust CD8+ T-cell response is induced by atRA treatment of mice with CAC.

Figure 5. atRA reduces tumor burden in AOM-DSS mice through a CD8+ T-cell-dependent mechanism.

(A–D) Flow cytometry data of percentages of CD69+ CD8+ T-cells (A,B,C) and Ki67+ CD8+ T-cells (D) in tumors (A,D), surrounding distal colonic tissue (A,D), IEL and LP layers of the tumors (C) and MLNs (B) of vehicle-or atRA-treated AOM-DSS mice. Data were pooled from 3 independent experiments with n=14 mice per group (A) and n=8 mice per group (B), and from 2 independent experiments with n=6–10 mice per group (C) and n=6 mice per group (D). (E) Tumor analyses of vehicle- or atRA-treated AOM-DSS mice injected from week 4 to week 9 with isotype control or anti-CD8α depleting antibody. Data were pooled from 2 independent experiments with n=6 mice in the isotype-treated group and n=8 mice in the CD8-depleted group. (F) Immunofluorescence images showing EpCAM (green), DAPI (blue) and TUNEL (red) in colonic tumor sections from atRA- or vehicle-treated isotype-injected and CD8-depleted AOM-DSS mice. Representative image from n=6 per group in the isotype-treated group and n=4 mice in the CD8-depleted group. Scale bar=50 μm. (G) Relative number of TUNEL+ cells quantified by normalizing to tumor crypt area in (F). (H) Tumor analyses in Cd8a−/− mice induced with AOM-DSS, and Cd8a−/− mice adoptively transferred with CD8+ T-cells, treated from week 3 to week 9 with atRA (n=6–9 mice per group). Results are represented as mean ± SEM. p<0.05=*; p<0.01=**; p<0.001=***, Mann Whitney U-test. See also Figure S4 and S5.

The anti-tumor effect of atRA is CD8+ T-cell dependent

To determine the functional relevance of the CD8+ T-cell response elicited by atRA treatment, we evaluated the therapeutic benefit of atRA in AOM-DSS mice depleted of CD8+ T-cells (Figure S4B) as well as in CD8-deficient (Cd8a−/−) mice. atRA had no effect on tumor burden in either CD8+ T-cell-depleted mice or Cd8a−/− mice (Figure 5E,H), demonstrating that the therapeutic effect of atRA is dependent on CD8+ T-cells. Consistent with this idea, we observed a four-fold increase in tumor cell death in atRA-treated AOM-DSS mice compared to vehicle-treated mice (Figure 5F,G), with CD8+ T-cells in close proximity to TUNEL+ tumor cells in the atRA-treated condition (Figure S4C). This increase in tumor cell death was completely abrogated in CD8+ T-cell-depleted mice (Figure 5F,G). Importantly, the therapeutic benefit of atRA treatment in Cd8a−/− mice was restored upon adoptive transfer of CD8+ T-cells (Figure 5H and Figure S4D). Although mature CD4+ T-cells can be reprogrammed in an atRA-dependent manner into MHCII-restricted CD8αα+ IELs with cytotoxic functions (Mucida et al., 2013; Reis et al., 2014), in the context of CAC, atRA treatment did not increase the frequency of this cell type (Figure S4E). These results therefore demonstrate that the therapeutic benefit conferred by atRA is dependent on CD8+ T-cells.

A detailed analysis of CD4+ T-cells did not reveal any significant changes in the number (Figure S5A) or activation status of these cells in the tumors and MLNs of atRA-treated mice (Figure S5B,C). Moreover, CD4+ T-cells isolated from the tumor or surrounding tissue from atRA-treated mice did not show any differences in TNFα, IFNγ, or IL-17A secretion compared to vehicle-treated mice (Figure S5D,E). Interestingly, there was a significant increase in the frequency of CD4+FOXP3+ regulatory T (Treg) cells in tumors of atRA-treated mice (Figure S5F); however, this increase in tumoral Treg cells was observed in atRA-treated Cd8a−/− mice as well (Figure S5G), which are refractory to the therapeutic benefit of atRA, indicating that the anti-tumor effect of atRA is not mediated through Treg cells alone.

In a study in mice with DSS-induced colitis, atRA supplementation suppressed colitis by inducing γδ+ T-cells to secrete IL-22 (Mielke et al., 2013). However, in our studies, atRA treatment of Tcrd−/− mice still significantly decreased tumor burden, indicating that γδ+ T-cells are not required for the anti-tumor effect of atRA (Figure S5H). Nonetheless, we observed that the colonic tissue surrounding the tumoral regions in atRA-treated mice had reduced inflammation scores, which could contribute to the atRA-mediated reduction in tumor burden in parallel with the CD8+ T-cell mechanism (Figure S5I,J).

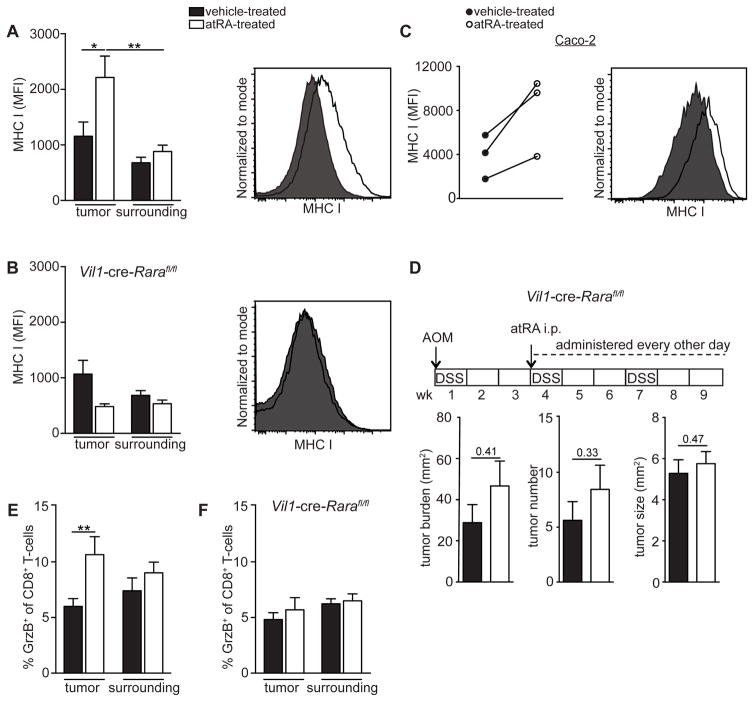

atRA upregulates MHCI expression on tumor epithelial cells to promote T-cell cytotoxicity

Given that CD8+ T-cells are the dominant mediator of the anti-tumor effect of atRA, we sought to determine the mechanistic basis of the CD8+ T-cell-dependent effect of atRA treatment on CAC. Since CD8+ T-cell-mediated cytotoxicity is MHC class I-restricted, we analyzed the expression of MHCI on the tumor epithelial cells before and after atRA treatment and found that mice treated with atRA exhibited a significant increase in MHCI (Figure 6A and Figure S6A). Interestingly, this atRA-mediated increase in MHCI was abrogated when the retinoic acid receptor alpha (RARα) was deleted from intestinal epithelial cells using Vil1-cre-Rarafl/fl mice (Figure 6B). In line with the direct mode of action of atRA on tumor epithelial cells, exogenous addition of atRA to the human colon cancer cell line Caco-2 in vitro also increased MHCI expression (Figure 6C).

Figure 6. atRA upregulates MHCI expression on tumor epithelial cells, leading to increased cytotoxic T lymphocytes.

(A,B) Flow cytometry plots of geometric mean intensity (MFI) of MHCI expression on tumor and surrounding epithelial cells (EpCAM+) from atRA- or vehicle-treated normal age-matched (A) or Vil1-cre-Rarafl/fl (B) AOM-DSS mice. Also shown are representative histograms of MHCI from the tumor epithelial cells. Data were pooled from 2 independent experiments with n=8–9 mice per group. (C) MHCI MFI on Caco-2 cells 72 hrs after in vitro treatment with 1 μM atRA compared to vehicle (DMSO). Shown are 3 independent experiments and a representative histogram. (D) Tumor analyses of vehicle- or atRA-treated Vil1-cre-Rarafl/fl mice induced with AOM-DSS. Data were pooled from 2 independent experiments with n=8–9 mice per group. (E,F) Flow cytometry data of percentage of granzyme B+ CD8+ T-cells in the tumors and surrounding distal colonic tissue from atRA- versus vehicle-treated normal age-matched (E) or Vil1-cre-Rarafl/fl (F) AOM-DSS mice. Data were pooled from 2 independent experiments with n=6 mice per group. Results are represented as mean ± SEM p<0.05=*; p<0.01=**; p<0.001=***, Mann Whitney U-test. See also Figure S6 and S7.

Next, we considered the possibility that increased MHCI expression on tumor epithelial cells could render them more susceptible to CD8+ cytotoxic-T-cell killing. Indeed, Vil1-cre-Rarafl/fl mice that lack the atRA-mediated upregulation of MHCI were resistant to the anti-tumor effects of atRA (Figure 6D). Consistent with this, intratumoral CD8+ T-cells in atRA-treated AOM-DSS wild-type mice expressed higher levels of granzyme B, indicating increased cytotoxic activity (Figure 6E and Figure S6B), which was not seen in Vil1-cre-Rarafl/fl mice (Figure 6F). Consequently, untreated Vil1-cre-Rarafl/fl mice induced with AOM-DSS had a trend toward a higher tumor burden than control mice (Figure S6C). To determine if atRA acted on epithelial cells, and not myeloid cells or CD8+ T-cells, to mediate its anti-tumor effects, we tested whether mice lacking RARα expression in macrophages (Lyz2-cre-Rarafl/fl mice), dendritic cells (Itgax-cre-Rarafl/fl mice) and CD8+ T-cells (through adoptive transfer of CD8+ T-cells from Cd4-cre-Rarafl/fl mice into Cd8a−/− mice, as CD8+ T-cells in these mice lack the receptor due to cre expression in the double-positive thymocytes) were responsive to the anti-tumor effects of atRA. Importantly, all of the aforementioned mice exhibited lower tumor burdens upon atRA treatment, confirming that the anti-tumor effect of atRA was not dependent on direct effects of atRA on these cell types (Figure S6D–F). These results demonstrate that atRA acts directly on tumor epithelial cells to upregulate MHCI, thereby rendering them sensitive to CD8+ T-cell-mediated killing.

To assess our findings in another model of CRC, we investigated whether the MC38 subcutaneous tumor model was similarly responsive to atRA through a CD8+ T-cell-mediated mechanism. In line with our observations from the AOM-DSS model, we found that, while wild-type mice subcutaneously implanted with MC38 were responsive to the anti-tumor effect of atRA, Cd8a−/− mice were not (Figure S7A,B). Moreover, atRA-treated MC38 tumor mice had a significantly higher expression of MHCI on their tumor cells compared to vehicle-treated mice (Figure S7C).

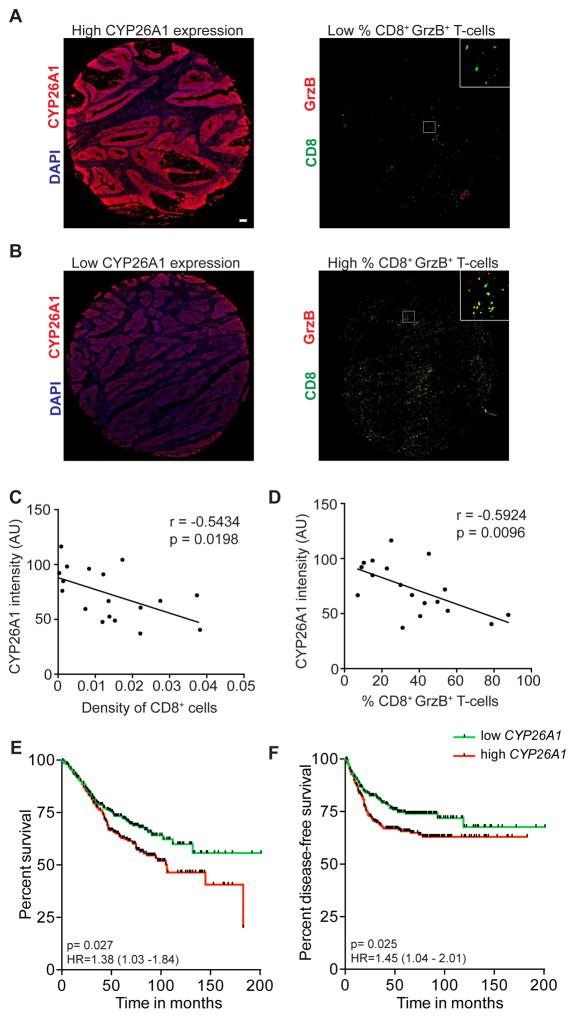

CYP26A1 in colon carcinoma correlates with reduced cytotoxic CD8+ T-cell frequency and worse disease prognosis

The findings from our mouse studies suggest that intestinal atRA deficiency dampens the CD8+ T-cell-mediated anti-tumor responses, which is known to correlate with overall survival in CRC (Deschoolmeester et al., 2010; Galon et al., 2006; Koelzer et al., 2014). We therefore correlated ALDH1A1 and CYP26A1 expression in each core biopsy from the sporadic colon cancer tissue microarray with tumoral CD8+ T-cell density and granzyme B expression to determine if atRA metabolism could predict cytotoxic T-cell potential. Indeed, there was a significant negative correlation between CYP26A1 expression and both tumoral CD8+ T-cell density (Figure 7A–C) and percentage of CD8+ T-cells expressing granzyme B in CRC specimens (Figure 7A,B and D). We found no significant correlation with ALDH1A1 (data not shown). We also tested whether ALDH1A1 and CYP26A1 mRNA expression correlates with disease prognosis using the GSE39582 dataset (Marisa et al., 2013). This dataset has a large number of CRC samples obtained from a multi-center cohort (n=566) containing information on overall survival and disease-free survival. Although ALDH1A1 expression did not correlate with disease prognosis, CYP26A1 expression correlated inversely with both overall survival and disease-free survival (Figure 7E,F).

Figure 7. CYP26A1 in colon carcinoma correlates with reduced CD8+ T-cell cytotoxicity as well as with worse disease prognosis.

(A,B) Representative images of core biopsies of adenocarcinomas showing high and low CYP26A1 staining (red) and corresponding serial sections showing CD8+ T-cell staining (green) and granzyme B staining (red). Scale bar=50 μm. (C,D) Correlation between CYP26A1 staining intensity (in arbitrary units (AU)) and CD8+ T-cell density normalized to tumor area (C) and percentage of CD8+ T-cells expressing granzyme B (D) in sporadic adenocarcinoma specimens, using Pearson’s correlation analyses. (E,F) Kaplan-Meier curves showing the correlation of CYP26A1 transcript expression, partitioned around the median, with overall survival (E) and disease-free survival (F) in colon cancer patients. p<0.05=*; p<0.01=**; p<0.001=***.

Discussion

atRA has shown promise in the treatment of several malignancies. In acute promyelocytic leukemia, it is known to act by inducing post-maturation apoptosis of the leukemic cells (Jimenez-Lara et al., 2004). Despite its established regulatory role in intestinal immunity, the influence of atRA on CRC development has not been previously examined. Our findings reveal that mice with CAC have significantly reduced levels of atRA in their colons due to a marked decrease in atRA-synthesizing ALDH1A enzymes and an increase in atRA-catabolizing CYP26 enzymes, imputing an important role to atRA in CRC.

Direct evidence of the adverse effect of an atRA deficit was demonstrated in mice with CAC. In these mice, further inhibition of atRA signaling increased tumor burden, while, conversely, atRA supplementation reduced tumor burden. Interestingly, depletion of the intestinal microbiota in AOM-DSS mice prevented the alteration of the atRA enzymes. The absence of intestinal bacteria in germ-free mice and antibiotic-treated mice has been demonstrated to dramatically reduce tumor formation in several models of CRC (Grivennikov et al., 2012; Zackular et al., 2013). Increased inflammation and production of genotoxic metabolites are among the mechanisms by which microbiota potentiate colon carcinogenesis (Belcheva et al., 2014; Grivennikov, 2013). However, our study demonstrates yet another mechanism by which intestinal microbiota may promote CRC—by altering atRA metabolism.

An important finding of our study is that CRC patients have similar alterations in atRA metabolism in their tumors irrespective of whether they had a history of colitis. High inter-patient variability in our tissue microarray analysis of ALDH1A1 and CYP26A1 in sporadic colon carcinomas and adenomas may reflect differences in the extent of barrier permeability or associated inflammation. Similarly, adenocarcinomas may exhibit lower expression of epithelial tight junction proteins and greater barrier permeability compared to adenomas, possibly explaining the more pronounced enzyme changes in carcinomas (Nakayama et al., 2008; Soler et al., 1999). Nevertheless, when compared with normal colonic mucosa, colitis, dysplasia and colon carcinoma are all characterized by a decrease in ALDH1A1 and a concomitant increase in the CYP26A1, indicative of reduced colonic levels of atRA. These findings are in accord with recent investigations of sporadic CRC (Kropotova et al., 2014), including a study demonstrating that CYP26B1 expression directly correlates with disease prognosis (Brown et al., 2014). In the present study, we found a significant correlation between CYP26A1 transcript expression and both overall survival and disease-free survival in a multi-center cohort of CRC patients (Marisa et al., 2013). Our findings that abnormal atRA metabolism correlates with clinical prognosis and is present across most pre-neoplastic and neoplastic conditions of the colon, combined with the observed exacerbation of disease in mice with CAC upon inhibition of atRA signaling and the therapeutic benefit of atRA supplementation, suggest that atRA deficiency is an important factor in the pathogenesis of CRC.

A number of possible mechanisms might explain the beneficial anti-tumor effect of atRA. In a mouse model of Crohn’s disease, atRA supplementation attenuated disease progression by promoting Treg cell-mediated intestinal tolerance (Collins et al., 2011). In another study, atRA supplementation ameliorated DSS-induced colitis, but through a mechanism that was γδ+ T cell-dependent. (Mielke et al., 2013). However, in our studies, the anti-tumor effect of atRA was found to be independent of γδ+ T-cells. Since in vitro studies have shown that atRA can induce apoptosis of colon cancer cell lines, albeit at high non-physiological concentrations (Bengtsson et al., 2013; Lee et al., 2000), we considered the possibility that the therapeutic benefit of atRA was due to a direct apoptotic effect on the tumor cells. In our studies, atRA treatment did lead to tumor cell apoptosis in vivo, but, surprisingly, the therapeutic effect of atRA was mediated by CD8+ T-cells rather than through a direct anti-tumor effect.

Previous studies have shown that atRA can elicit CD4+ or CD8+ effector T-cell responses in the context of infection (Guo et al., 2014; Hall et al., 2011b). Here, in CAC, we found that atRA treatment led to an increase in tumoral CD8+ T-cell cytotoxic activity. Furthermore, using Vil1-cre-Rarafl/fl mice we found that atRA treatment directly acts on tumor epithelial cells to upregulate MHCI expression, thereby rendering them more susceptible to killing by CD8+ cytotoxic T lymphocytes. Consistent with this mechanism, previous in vitro studies have demonstrated that MHCI is a direct transcriptional target of atRA (Balmer and Blomhoff, 2002; Jansa and Forejt, 1996; Nagata et al., 1992). Untreated Vil1-cre-Rarafl/fl mice induced with AOM-DSS did not develop more tumors than control mice, but since mice with CAC already have dramatically reduced levels of atRA, the absence of RARα on epithelial cells likely would have had little impact on tumor burden.

Our findings from the mouse model of CAC suggest that atRA deficiency in human CRC could impair effector cytotoxic T-cell function, resulting in accelerated growth of tumors. Consistent with this hypothesis, we found a strong negative correlation between abnormal atRA metabolism and both tumoral CD8+ T-cell frequency and granzyme B expression in human CRC. Several studies have shown that infiltration of T-cells, especially CD8+ T-cells, as well as MHCI expression by tumor cells, correlates with improved CRC prognosis (Deschoolmeester et al., 2010; Galon et al., 2006; Koelzer et al., 2014; Simpson et al., 2010). Our work not only provides a potential explanation for these phenomena, but also suggests that restoration of atRA levels in the colon could provide a therapeutic benefit in human CRC by promoting MHCI expression by tumor cells and cytotoxic T-cell function.

Experimental Procedures

Patient specimens

Patient specimens were obtained from the Stanford Tissue Bank and from the Toronto General Hospital (Ontario, Canada) under protocols approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB, Stanford) and the University Health Network Research Ethics Board (Toronto General Hospital).

Mice

C57BL/6 mice, Cd8a−/−, Vil1-cre mice, Lyz2-cre mice, Cd4-cre mice and Tcrd−/− mice were from The Jackson Laboratory. Rarafl/fl mice were a kind gift from Dr. Yasmine Belkaid (NIAID, Bethesda, MD).

DSS and AOM-DSS mouse models

The DSS and AOM-DSS mouse models of chronic colitis and CAC, respectively, were established using the protocol described by Wirtz et al. (Wirtz et al., 2007), with slight modifications. In brief, for the development of chronic colitis, mice were given 3% DSS salt in drinking water for 7 days, followed by drinking water for 14 days. This cycle was repeated twice. For CAC, mice were given an initial i.p. injection of AOM at the beginning of the chronic colitis protocol.

Antibiotic treatment of AOM-DSS mice

Antibiotics were supplied in water before induction with AOM-DSS. The antibiotics used were ampicillin (1g/L), metronidazole (1g/L), vancomycin (0.5 g/L), and neomycin (1g/L) (Sigma-Aldrich).

Bacterial culture on Agar plates

Fecal extract from antibiotic-treated mice were cultured on LB Agar and Blood Agar (TSA with 5% Sheep Blood) plates.

atRA treatment of Caco-2 cell line

Caco-2 cells were cultured in complete EMEM medium and treated with 1μM atRA or DMSO. They were harvested for analysis 72 hrs later.

Luciferase assay

CT26 or MC38 cells were transfected with a firefly luciferase reporter plasmid driven by a pGL3-RARE-responsive promoter (Addgene) and a renilla luciferase reporter plasmid. atRA or vehicle was added along with increasing amounts of Liarozole, and the activity of both reporters was recorded.

Intramucosal colonic injections

Antibiotic-treated C57BL/6 mice were injected intramucosally in the distal colon with a cytokine mixture containing 100ng each of TNFα, IL-1β, IL-12p70, IL-23, IL-6, IFNγ and IL-17A (Peprotech) or 1% BSA in PBS (vehicle), and the distal colonic tissues were collected for qRT-PCR analyses.

Intestinal organoid culture and cytokine treatment

Organoids derived from tumors of AOM-DSS mice were cultured with a cytokine mixture containing 50ng/mL each of TNFα, IL-1β, IL-12p70, IL-23, IL-6, IFNγ or 1% BSA in PBS (vehicle) for 48 hrs and then harvested for qRT-PCR analyses.

Quantitation of all-trans retinoic acid expression in mouse colonic tissue

atRA was extracted from mouse colons as described (Kane et al., 2008). Quantification of retinoids was done using LC-MS/MS with an alternate LC separation.

Drug treatment

200μg BMS493 (Tocris Bioscience) or DMSO alone (vehicle) was i.p. injected into female C57BL/6 mice 4 weeks prior to induction with AOM-DSS and continued until the end of the AOM-DSS treatment period. 200μg atRA or DMSO alone (vehicle) was i.p. injected into AOM-DSS mice either twice a week or every other day. 80 ppm Liarozole (Tocris Bioscience) was incorporated into a base diet containing 4 IU/g of vitamin A (Research Diets). Mice were orally gavaged with 400μg Liarozole or polyethylene glycol-200 (vehicle) after induction with AOM-DSS daily until the end of week 4.

CD8+ T-cell depletion

500μg rat anti-mouse CD8α antibody (clone YTS169.4, BioXCell) was injected i.p. into 10-week-old C57BL/6 female mice once a week, from week 4 to week 9 after disease induction. The control group received the same amount of isotype control antibody (clone LTF2, BioXCell).

Adoptive transfer of CD8+ T-cells into Cd8a−/− mice

CD8+ T-cells were isolated from the spleen, MLNs and other lymph nodes from DSS-treated C57BL/6 mice and adoptively transferred into Cd8a−/− mice (8×106 cells per mouse) 2 weeks after induction with AOM-DSS (Figure S4D). atRA or vehicle was administered every other day to recipient mice from the day of adoptive transfer to the end of week 9.

Immunoblotting

Protein lysates were prepared from the distal half of the colons using RIPA lysis buffer. Primary and secondary HRP-labeled antibodies were used at 1:500 and 1:2000 dilutions, respectively, in 5% milk in PBS-Tween.

Real time quantitative PCR (qRT-PCR)

Transcript expression was determined using the Fast SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems) and the 7900HT real-time PCR instrument (Applied Biosystems). For quantification of 16s rDNA, mouse fecal DNA was extracted using the REDExtract-N-Amp™ Tissue PCR Kit (Sigma Aldrich) and purified of inhibitors (Zymo Research).

Histology and Colitis grading

Disease diagnosis and colitis grading of hematoxylin and eosin stained slides were determined by an experienced gastrointestinal pathologist at Stanford University who was blinded with respect to treatment. For colitis grading, the scheme from Geboes et al. was used (Geboes et al., 2000).

Immunofluorescence staining

OCT-embedded colonic sections were post-fixed in 2% paraformaldehyde and blocked with 10% goat serum. They were subsequently stained with primary and secondary antibodies.

Flow cytometry

Isolated colonic and MLN cells were resuspended in FACS buffer containing 1% BSA in PBS and stained with antibodies. Flow cytometric data acquisition was performed on a LSRII flow cytometer (BD Biosciences).

Statistics

Experimental data were analyzed with the Mann Whitney U-test using Prism (GraphPad Software), unless otherwise stated. Tissue microarray data were analyzed using the One-way ANOVA test, and correlation analysis was performed using the Pearson’s correlation test. Kaplan Meier curves for disease-free survival and overall survival were generated and analyzed with Prism (GraphPad software) using the Log-rank (Mantel Cox) test. Results are represented as mean ± SEM. p<0.05=*; p<0.01=**; p<0.001=***.

Animal Study Approval

All animal protocols used in this study were approved by the Stanford University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Prof. Robert West for providing us with colon cancer specimens. We thank Raghav Kumar for technical assistance, Nancy Wu for flow cytometry assistance, Philip Engleman and Shawn Winer for help with the pathological diagnoses of histology slides. We also wish to thank Matt Spitzer and Ian Linde for critical review of the manuscript. The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grants 5 U01 CA141468 and 1 R01 CA163441.

Footnotes

Supplemental Information includes seven figures and detailed explanation of experimental procedures.

Author Contributions

N.B. and R.Y. conceived the study, performed all experiments, and wrote the manuscript; T.R.P., H.X.L.P., N.R.F., J.A.K. and Y.C. helped in designing the research and provided technical assistance. M.A.D. and T.D.P. provided pathology assistance. R.H. provided experimental help. C.R.K., J.W. and J.L.N. provided experimental assistance for the atRA mass spectrometry measurements. L.T., and O.C. provided technical assistance with flow cytometry. D.W. provided patient specimens for histology. E.G.E. supervised the study and wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Allie SR, Zhang W, Tsai CY, Noelle RJ, Usherwood EJ. Critical role for all-trans retinoic acid for optimal effector and effector memory CD8 T cell differentiation. Journal of immunology. 2013;190:2178–2187. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1201945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arthur JC, Perez-Chanona E, Muhlbauer M, Tomkovich S, Uronis JM, Fan TJ, Campbell BJ, Abujamel T, Dogan B, Rogers AB, et al. Intestinal inflammation targets cancer-inducing activity of the microbiota. Science. 2012;338:120–123. doi: 10.1126/science.1224820. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balmer JE, Blomhoff R. Gene expression regulation by retinoic acid. Journal of lipid research. 2002;43:1773–1808. doi: 10.1194/jlr.r100015-jlr200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belcheva A, Irrazabal T, Robertson SJ, Streutker C, Maughan H, Rubino S, Moriyama EH, Copeland JK, Kumar S, Green B, et al. Gut microbial metabolism drives transformation of MSH2-deficient colon epithelial cells. Cell. 2014;158:288–299. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.04.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bengtsson AM, Jonsson G, Magnusson C, Salim T, Axelsson C, Sjolander A. The cysteinyl leukotriene 2 receptor contributes to all-trans retinoic acid-induced differentiation of colon cancer cells. BMC cancer. 2013;13:336. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-13-336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benson MJ, Pino-Lagos K, Rosemblatt M, Noelle RJ. All-trans retinoic acid mediates enhanced T reg cell growth, differentiation, and gut homing in the face of high levels of co-stimulation. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2007;204:1765–1774. doi: 10.1084/jem.20070719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biondi A, Zoccali M, Costa S, Troci A, Contessini-Avesani E, Fichera A. Surgical treatment of ulcerative colitis in the biologic therapy era. World journal of gastroenterology: WJG. 2012;18:1861–1870. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v18.i16.1861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown GT, Cash BG, Blihoghe D, Johansson P, Alnabulsi A, Murray GI. The expression and prognostic significance of retinoic acid metabolising enzymes in colorectal cancer. PloS one. 2014;9:e90776. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0090776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cassani B, Villablanca EJ, De Calisto J, Wang S, Mora JR. Vitamin A and immune regulation: role of retinoic acid in gut-associated dendritic cell education, immune protection and tolerance. Molecular aspects of medicine. 2012;33:63–76. doi: 10.1016/j.mam.2011.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clagett-Dame M, DeLuca HF. The role of vitamin A in mammalian reproduction and embryonic development. Annual review of nutrition. 2002;22:347–381. doi: 10.1146/annurev.nutr.22.010402.102745E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins CB, Aherne CM, Kominsky D, McNamee EN, Lebsack MD, Eltzschig H, Jedlicka P, Rivera-Nieves J. Retinoic acid attenuates ileitis by restoring the balance between T-helper 17 and T regulatory cells. Gastroenterology. 2011;141:1821–1831. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.05.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coombes JL, Siddiqui KR, Arancibia-Carcamo CV, Hall J, Sun CM, Belkaid Y, Powrie F. A functionally specialized population of mucosal CD103+ DCs 25 induces Foxp3+ regulatory T cells via a TGF-beta and retinoic acid-dependent mechanism. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2007;204:1757–1764. doi: 10.1084/jem.20070590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Couturier-Maillard A, Secher T, Rehman A, Normand S, De Arcangelis A, Haesler R, Huot L, Grandjean T, Bressenot A, Delanoye-Crespin A, et al. NOD2-mediated dysbiosis predisposes mice to transmissible colitis and colorectal cancer. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2013;123:700–711. doi: 10.1172/JCI62236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deschoolmeester V, Baay M, Van Marck E, Weyler J, Vermeulen P, Lardon F, Vermorken JB. Tumor infiltrating lymphocytes: an intriguing player in the survival of colorectal cancer patients. BMC immunology. 2010;11:19. doi: 10.1186/1471-2172-11-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galon J, Costes A, Sanchez-Cabo F, Kirilovsky A, Mlecnik B, Lagorce-Pages C, Tosolini M, Camus M, Berger A, Wind P, et al. Type, density, and location of immune cells within human colorectal tumors predict clinical outcome. Science. 2006;313:1960–1964. doi: 10.1126/science.1129139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geboes K, Riddell R, Ost A, Jensfelt B, Persson T, Lofberg R. A reproducible grading scale for histological assessment of inflammation in ulcerative colitis. Gut. 2000;47:404–409. doi: 10.1136/gut.47.3.404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Germain P, Gaudon C, Pogenberg V, Sanglier S, Van Dorsselaer A, Royer CA, Lazar MA, Bourguet W, Gronemeyer H. Differential action on coregulator interaction defines inverse retinoid agonists and neutral antagonists. Chemistry & biology. 2009;16:479–489. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2009.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grivennikov SI. Inflammation and colorectal cancer: colitis-associated neoplasia. Semin Immunopathol. 2013;35:229–244. doi: 10.1007/s00281-012-0352-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grivennikov SI, Wang K, Mucida D, Stewart CA, Schnabl B, Jauch D, Taniguchi K, Yu GY, Osterreicher CH, Hung KE, et al. Adenoma-linked barrier defects and microbial products drive IL-23/IL-17-mediated tumour growth. Nature. 2012;491:254–258. doi: 10.1038/nature11465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo Y, Lee YC, Brown C, Zhang W, Usherwood E, Noelle RJ. Dissecting the role of retinoic acid receptor isoforms in the CD8 response to infection. Journal of immunology. 2014;192:3336–3344. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1301949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo Y, Pino-Lagos K, Ahonen CA, Bennett KA, Wang J, Napoli JL, Blomhoff R, Sockanathan S, Chandraratna RA, Dmitrovsky E, et al. A retinoic acid-- rich tumor microenvironment provides clonal survival cues for tumor-specific CD8(+) T cells. Cancer research. 2012;72:5230–5239. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-1727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haggar FA, Boushey RP. Colorectal cancer epidemiology: incidence, mortality, survival, and risk factors. Clinics in colon and rectal surgery. 2009;22:191–197. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1242458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall JA, Cannons JL, Grainger JR, Dos Santos LM, Hand TW, Naik S, Wohlfert EA, Chou DB, Oldenhove G, Robinson M, et al. Essential role for retinoic acid in the promotion of CD4(+) T cell effector responses via retinoic acid receptor alpha. Immunity. 2011a;34:435–447. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall JA, Grainger JR, Spencer SP, Belkaid Y. The role of retinoic acid in tolerance and immunity. Immunity. 2011b;35:13–22. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu B, Elinav E, Huber S, Strowig T, Hao L, Hafemann A, Jin C, Wunderlich C, Wunderlich T, Eisenbarth SC, Flavell RA. Microbiota-induced activation of epithelial IL-6 signaling links inflammasome-driven inflammation with transmissible cancer. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2013;110:9862–9867. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1307575110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jansa P, Forejt J. A novel type of retinoic acid response element in the second intron of the mouse H2Kb gene is activated by the RAR/RXR heterodimer. Nucleic acids research. 1996;24:694–701. doi: 10.1093/nar/24.4.694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jimenez-Lara AM, Clarke N, Altucci L, Gronemeyer H. Retinoic-acid-induced apoptosis in leukemia cells. Trends in molecular medicine. 2004;10:508–515. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2004.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kane MA, Folias AE, Wang C, Napoli JL. Quantitative profiling of endogenous retinoic acid in vivo and in vitro by tandem mass spectrometry. Analytical chemistry. 2008;80:1702–1708. doi: 10.1021/ac702030f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kedishvili NY. Enzymology of retinoic acid biosynthesis and degradation. Journal of lipid research. 2013;54:1744–1760. doi: 10.1194/jlr.R037028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koelzer VH, Lugli A, Dawson H, Hadrich M, Berger MD, Borner M, Mallaev M, Galvan JA, Amsler J, Schnuriger B, et al. CD8/CD45RO T-cell infiltration in endoscopic biopsies of colorectal cancer predicts nodal metastasis and survival. Journal of translational medicine. 2014;12:81. doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-12-81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kropotova ES, Zinovieva OL, Zyryanova AF, Dybovaya VI, Prasolov VS, Beresten SF, Oparina NY, Mashkova TD. Altered expression of multiple genes involved in retinoic acid biosynthesis in human colorectal cancer. Pathology oncology research: POR. 2014;20:707–717. doi: 10.1007/s12253-014-9751-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee MO, Han SY, Jiang S, Park JH, Kim SJ. Differential effects of retinoic acid on growth and apoptosis in human colon cancer cell lines associated with the induction of retinoic acid receptor beta. Biochemical pharmacology. 2000;59:485–496. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(99)00355-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marisa L, de Reynies A, Duval A, Selves J, Gaub MP, Vescovo L, Etienne-Grimaldi MC, Schiappa R, Guenot D, Ayadi M, et al. Gene expression classification of colon cancer into molecular subtypes: characterization, validation, and prognostic value. PLoS medicine. 2013;10:e1001453. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mark M, Ghyselinck NB, Chambon P. Function of retinoid nuclear receptors: lessons from genetic and pharmacological dissections of the retinoic acid signaling pathway during mouse embryogenesis. Annual review of pharmacology and toxicology. 2006;46:451–480. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.46.120604.141156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mielke LA, Jones SA, Raverdeau M, Higgs R, Stefanska A, Groom JR, Misiak A, Dungan LS, Sutton CE, Streubel G, et al. Retinoic acid expression associates with enhanced IL-22 production by gammadelta T cells and innate lymphoid cells and attenuation of intestinal inflammation. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2013;210:1117–1124. doi: 10.1084/jem.20121588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mucida D, Husain MM, Muroi S, van Wijk F, Shinnakasu R, Naoe Y, Reis BS, Huang Y, Lambolez F, Docherty M, et al. Transcriptional reprogramming of mature CD4(+) helper T cells generates distinct MHC class II-restricted cytotoxic T lymphocytes. Nature immunology. 2013;14:281–289. doi: 10.1038/ni.2523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mucida D, Park Y, Kim G, Turovskaya O, Scott I, Kronenberg M, Cheroutre H. Reciprocal TH17 and regulatory T cell differentiation mediated by retinoic acid. Science. 2007;317:256–260. doi: 10.1126/science.1145697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagata T, Segars JH, Levi BZ, Ozato K. Retinoic acid-dependent transactivation of major histocompatibility complex class I promoters by the nuclear hormone receptor H-2RIIBP in undifferentiated embryonal carcinoma cells. 27 Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1992;89:937–941. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.3.937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakayama F, Semba S, Usami Y, Chiba H, Sawada N, Yokozaki H. Hypermethylation-modulated downregulation of claudin-7 expression promotes the progression of colorectal carcinoma. Pathobiology: journal of immunopathology, molecular and cellular biology. 2008;75:177–185. doi: 10.1159/000124978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obrochta KM, Krois CR, Campos B, Napoli JL. Insulin regulates retinol dehydrogenase expression and all-trans-retinoic acid biosynthesis through FoxO1. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2015;290:7259–7268. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.609313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reis BS, Hoytema van Konijnenburg DP, Grivennikov SI, Mucida D. Transcription factor T-bet regulates intraepithelial lymphocyte functional maturation. Immunity. 2014;41:244–256. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.06.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson JA, Al-Attar A, Watson NF, Scholefield JH, Ilyas M, Durrant LG. Intratumoral T cell infiltration, MHC class I and STAT1 as biomarkers of good prognosis in colorectal cancer. Gut. 2010;59:926–933. doi: 10.1136/gut.2009.194472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soler AP, Miller RD, Laughlin KV, Carp NZ, Klurfeld DM, Mullin JM. Increased tight junctional permeability is associated with the development of colon cancer. Carcinogenesis. 1999;20:1425–1431. doi: 10.1093/carcin/20.8.1425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka T, Kohno H, Suzuki R, Yamada Y, Sugie S, Mori H. A novel inflammation-related mouse colon carcinogenesis model induced by azoxymethane and dextran sodium sulfate. Cancer science. 2003;94:965–973. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2003.tb01386.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ullman TA, Itzkowitz SH. Intestinal inflammation and cancer. Gastroenterology. 2011;140:1807–1816. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.01.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Wauwe JP, Coene MC, Goossens J, Cools W, Monbaliu J. Effects of cytochrome P-450 inhibitors on the in vivo metabolism of all-trans-retinoic acid in rats. The Journal of pharmacology and experimental therapeutics. 1990;252:365–369. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wirtz S, Neufert C, Weigmann B, Neurath MF. Chemically induced mouse models of intestinal inflammation. Nature protocols. 2007;2:541–546. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zackular JP, Baxter NT, Iverson KD, Sadler WD, Petrosino JF, Chen GY, Schloss PD. The gut microbiome modulates colon tumorigenesis. mBio. 2013;4:e00692–00613. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00692-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.