Abstract

Objective The objective of this study was to evaluate the potential impact to the U.S. health care system by adopting a novel test that identifies women at risk for spontaneous preterm birth.

Methods A decision-analytic model was developed to assess clinical and cost outcomes over a 1-year period. The use of a prognostic test to predict spontaneous preterm birth in a hypothetical population of women reflective of the U.S. population (predictive arm) was compared with the current baseline rate of spontaneous preterm birth and associated infant morbidity and mortality (baseline care arm).

Results In a population of 3,528,593 births, our model predicts a 23.5% reduction in infant mortality (8,300 vs. 6,343 deaths) with use of the novel test. The rate of acute conditions at birth decreased from 11.2 to 8.1%; similarly, the rate of developmental disabilities decreased from 13.2 to 11.5%. The rate of spontaneous preterm birth decreased from 9.8 to 9.1%, a reduction of 23,430 preterm births. Direct medical costs savings was $511.7M (− 2.1%) in the first year of life.

Discussion The use of a prognostic test for reducing spontaneous preterm birth is a dominant strategy that could reduce costs and improve outcomes. More research is needed once such a test is available to determine if these results are borne out upon real-world use.

Keywords: preterm birth, spontaneous preterm birth, infant mortality, infant morbidity, progesterone, clinical and cost outcomes, prenatal testing

Studies have demonstrated the enormous clinical and economic impact of preterm birth. However, an effective method to identify women at risk for having a preterm birth is not currently available. We describe the potential clinical and economic outcomes of incorporating a novel prognostic test that identifies pregnant women at risk for having a spontaneous preterm birth into routine clinical practice. Our study provides a valuable framework to the clinical community and other U.S. health care stakeholders to explore the impact of such a test as well as other new technologies developed to address the significant challenges of preterm birth.

As the leading cause of death among children younger than the age of 5 years globally, preterm birth is a major public health concern.1 In the United States, approximately one out of every nine infants (11.4%) is born preterm, defined by Goldenberg et al2 as a birth occurring before 37 weeks, and preterm birth is the predominant driver of perinatal morbidity and mortality.3 The risk of mortality and serious acute morbidities such as respiratory distress syndrome (RDS), necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC), and intraventricular hemorrhage (IVH) are inversely correlated with gestational age (GA).4 5 Major developmental disabilities (DDs) associated with preterm birth include neurodevelopmental impairment (mental retardation), vision loss, hearing loss, and cerebral palsy (CP).6

Consequently, preterm birth has a significant economic impact on the U.S. health care system and society as a whole. Based on previous cost estimates published by the Institute of Medicine in 2006, today, preterm birth costs the United States approximately $31.5B annually (2015 dollars).6 Medical care accounts for approximately 65% ($20.3B in 2015 dollars) of these costs and more than 85% of medical services are delivered in the first year of life.6 Direct medical costs due to hospitalization and intervention at birth are especially high for extremely preterm infants (less than 28 weeks of gestation), with estimates of $300,000 to $400,000 (2015 dollars) per infant, on average.6 These costs, as well as other costs for nonacute conditions incurred during the first year of life, are significantly reduced as GA increases.

Due to the significant clinical and economic impact of preterm birth, there is a current unmet need to identify and treat at-risk women with the goal of increasing gestational time. Some women may be identified as having an elevated risk for spontaneous preterm birth based on medical history and epidemiological factors; however, a highly effective and objective method to identify at-risk women without a prior spontaneous preterm birth is not currently available. A short cervix is a consistent risk factor for spontaneous preterm birth and evidence suggests that early onset of cervical shortening indicates the start of pathological preterm parturition.7 As a result, there is interest within the clinical community to conduct cervical length screening alone or in combination with fetal fibronectin testing during the course of prenatal care. However, implementation of cervical length screening has been hindered due to a lack of standardized protocols to identify screening candidates, and concerns regarding the quality and reproducibility of results. In addition, specialized equipment and personnel are required to perform transvaginal ultrasonography, which is superior to transabdominal ultrasound in performance.8 9

Progestogens are currently recommended for women with a clinically detected short cervix or a prior spontaneous preterm birth.10 11 However, cervical length screening has been difficult to implement in clinical practice and does not identify all women who will have spontaneous preterm birth.12 In addition, women with a prior spontaneous preterm birth represent only a modest percentage of all pregnant women and the distinction between spontaneous preterm birth versus indicated preterm birth is not well defined and may overlap.13 Furthermore, progestogens will not prevent spontaneous preterm birth in all women for whom they are indicated.11 12 Therefore, more effective screening tests are needed to identify women at risk of spontaneous preterm birth, as well as better stratify the at-risk population into progestogen responders and nonresponders. In this study, we model the potential impact of a novel blood test to predict risk of spontaneous preterm birth on clinical and economic outcomes from the U.S. perspective. We present an analytical framework for what might be achieved upon incorporation of such a test into routine care that could further enhance the potential for progestogens, or other interventions, to reduce the overall burden of preterm birth. Our analysis is important to understanding the potential clinical and economic implications of adopting such a test.

Methods

A decision-analytic model was developed in Excel (Microsoft Office 2010, Microsoft, Redmond, WA) to compare the clinical outcomes and costs of adopting a novel testing modality to identify women at risk for spontaneous preterm birth, with the current baseline outcomes of infants born preterm, defined as 23 to 37 weeks of gestation. The model considers a hypothetical population of 3,528,593 pregnant women with a singleton gestation and no history of spontaneous preterm birth. The population was estimated by the U.S. Department of Commerce14 based on the U.S. population of 319,000,000 with a fertility rate4 of 2.4/1,000, 95% singleton pregnancy rate,4 and 94% of pregnancies without a history of preterm birth.15

The model estimates direct medical costs from the U.S. health care system perspective over a 1-year time horizon. The model consists of two arms: one where women receive a prognostic test to predict the risk of spontaneous preterm birth (predictive arm) and one where women receive baseline care in the absence of a novel prognostic test (baseline arm). Outcomes in the baseline arm were based on current costs for preterm birth and current risks for acute and long-term morbidities. Women enter the model with no history of having a spontaneous preterm birth and receive a novel prognostic test (see Supplemental Digital Content 1 [online only] for patient flow in the predictive arm). Test-positive women are treated with vaginal progesterone. Patient response to vaginal progesterone therapy is considered to either be analogous to clinical trial results or absent (no response to treatment). The majority of clinical trial data for vaginal progesterone is based on women with a short cervix or a prior preterm birth while the model is focused on a broader population of women with no history of having a preterm birth and with no known presence of a short cervix.

To approximate real-world effectiveness and account for differences between the trial population and the model population, we reduced the population of women impacted by vaginal progesterone to 80% of what has been reported in trials. Trial data report the overall impact of vaginal progesterone in the trial population, including nonresponders16; therefore, our assumption accounts for additional nonresponders in the model population as only 80% of the test-positive population will see increases in the GA at birth, as reported in trials. Validation of the model included review of face validity of the inputs and outcomes through presentation to an expert and the impact of our assumptions were tested via sensitivity analyses. In addition, the resulting cumulative relative risks (RRs) of preterm births in the intervention arm were compared with clinical trial results.

Clinical data to support current risk of spontaneous preterm birth by week when receiving baseline care were sourced from the Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).17 Test performance data and prognostic test cost used in the model are based on the hypothesized performance and cost of a novel serum test currently in development (Table 1) and the threshold at which such a test could provide value was analyzed. Clinical inputs were taken from several sources (Table 2). The reduced risk of spontaneous preterm birth with vaginal progesterone treatment is based on a meta-analysis of five clinical trials for vaginal progesterone in women with a short cervix.17 Data from the meta-analysis were used to fit a week-by-week curve for the RRs of spontaneous preterm birth for the population assumed to respond to vaginal progesterone treatment (see Supplemental Digital Content 2 [online only] for RR of spontaneous preterm birth with vaginal progesterone).

Table 1. Population, test, and intervention inputs.

| Variables | Input | Base value | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Population variables | U.S. population | 319,000,000 | U.S. Census Bureau |

| Incidence of pregnancy (per 1,000) | 12.4 | CDC (2013) | |

| Percentage of pregnancies that are singleton | 95% | CDC (2013) | |

| Rate of spontaneous preterm birth | 9.8% | CDC (2013) | |

| Percentage of women with a history of preterm birth | 6.1% | Petrini et al (2005) | |

| Test/intervention variables | Test sensitivity | 80% | Hypothesized performance |

| Test specificity | 80% | Hypothesized performance | |

| Cost of prognostic test | $1,250 | Market-based assumption aligned with cost for noninvasive prenatal testing at launch | |

| Percentage of women who respond to vaginal progesterone as reported in trials (accounts for additional nonresponders) | 80% | Expert opinion | |

| Cost of vaginal progesterone | $307 | Cahill (2010)29 |

Abbreviation: CDC, Center for Disease Control and Prevention.

Table 2. Clinical inputs.

| GA | Impact of progesterone | Mortality | Mortality by 30 d | CP | Intellectual impairment | Vision impairment | Hearing impairment | RDS | BPD | IVH | NEC | Readmissions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Week 23 | 0.49 | 57.0% | 52.9% | 18.9% | 24.3% | 12.1% | 11.5% | 98.0% | 70.0% | 47.1% | 12.0% | 31.0% |

| Week 24 | 0.5 | 34.1% | 28.7% | 17.5% | 21.7% | 9.5% | 8.4% | 95.8% | 57.3% | 30.7% | 8.8% | 31.0% |

| Week 25 | 0.51 | 22.8% | 18.1% | 16.1% | 19.4% | 7.5% | 6.1% | 91.3% | 43.5% | 20.0% | 6.3% | 31.0% |

| Week 26 | 0.52 | 14.6% | 11.6% | 14.7% | 17.3% | 5.9% | 4.4% | 82.9% | 30.7% | 13.0% | 4.5% | 27.0% |

| Week 27 | 0.525 | 10.4% | 7.9% | 13.4% | 15.4% | 4.6% | 3.2% | 69.1% | 20.3% | 8.5% | 3.2% | 26.0% |

| Week 28 | 0.55 | 5.5% | 3.9% | 12.0% | 13.7% | 3.6% | 2.3% | 50.9% | 12.8% | 5.5% | 2.3% | 22.0% |

| Week 29 | 0.575 | 4.2% | 3.2% | 10.7% | 12.3% | 2.8% | 1.7% | 32.4% | 7.8% | 3.6% | 1.6% | 21.0% |

| Week 30 | 0.6 | 3.2% | 2.4% | 9.4% | 10.9% | 2.2% | 1.2% | 18.1% | 4.6% | 2.4% | 1.2% | 19.0% |

| Week 31 | 0.625 | 2.6% | 1.8% | 8.1% | 9.8% | 1.8% | 0.9% | 9.3% | 2.7% | 1.5% | 0.8% | 16.0% |

| Week 32 | 0.65 | 1.8% | 1.2% | 6.8% | 8.7% | 1.4% | 0.7% | 4.5% | 1.6% | 1.0% | 0.6% | 15.0% |

| Week 33 | 0.7 | 1.5% | 1.0% | 5.5% | 7.8% | 1.1% | 0.5% | 2.1% | 0.9% | 0.7% | 0.4% | 14.0% |

| Week 34 | 0.8 | 1.1% | 0.6% | 4.2% | 6.9% | 0.9% | 0.3% | 1.0% | 0.5% | 0.4% | 0.3% | 13.0% |

| Week 35 | 0.95 | 0.8% | 0.4% | 3.0% | 6.2% | 0.7% | 0.3% | 0.5% | 0.3% | 0.3% | 0.2% | 13.0% |

| Week 36 | 1.125 | 0.6% | 0.3% | 1.8% | 5.5% | 0.5% | 0.2% | 0.2% | 0.2% | 0.2% | 0.1% | 13.0% |

| Week 37 | 0.2% | 0.1% | 0.1% | 4.1% | 0.3% | 0.1% | 0.1% | 0.1% | 0.1% | 0.1% | 13.0% | |

| Source | Romero et al (2012) | CDC (2013) | CDC (2013) | Larroque (2008)30 | Larroque (2008)30 | Larroque (2008)30 | van Dommelen (2015)31 | Stoll (2010)32 | Stoll (2010)32 | Stoll (2010)32 | Stoll (2010)32 | Underwood (2007)33 |

Abbreviations: BPD, bronchial pulmonary dysplasia; CP, cerebral palsy; GA, gestational age; IVH, intraventricular hemorrhage; NEC, necrotizing enterocolitis; RDS, respiratory distress.

Clinical outcomes include the shifts in GA and percentage of associated mortality and acute morbidities, including RDS, bronchial pulmonary dysplasia (BPD), IVH, and NEC. Additional clinical outcomes include the major DDs associated with preterm birth including neurodevelopmental impairment (mental retardation), vision impairment, hearing impairment and CP (see Supplemental Digital Content 3 [online only] for further outcomes information).

Although many clinical outcomes have long-term cost consequences, only the 1 year incremental cost of direct medical expenses are considered within the model. Costs inputs were derived from a literature review, with the exception of the reimbursement for the prognostic test which is assumed to be $1,250, a cost that is aligned with the previous market tolerability for noninvasive prenatal testing at launch. Costs to the health care system are reported in 2015 U.S. dollars and were inflated using the health-specific CPI data. Direct medical costs include maternal costs most closely associated with the intervention and infant costs incurred at delivery through the first year of life; maternal costs for delivery were excluded assuming the relative impact of these costs would be minimal. Specifically, direct medical costs include costs for testing, treatment with vaginal progesterone, hospitalization of the infant at birth, and rehospitalization costs incurred in the first year of life (Table 3). Given the short-term focus, costs were not discounted. Where cost for each week of GA was not available, a cost distribution was assumed based on sample data and expert opinion; available data were fit to the distribution (see Supplemental Digital Contents 4 and 5 [online only] for distribution information).

Table 3. Economic inputs.

| Gestational age | LOS (d) | First year rehospitalization costs | Acute cost |

|---|---|---|---|

| Week 23 | 78.9 | $37,291 | $400,204 |

| Week 24 | 78.9 | $37,291 | $400,204 |

| Week 25 | 83.3 | $30,478 | $419,939 |

| Week 26 | 82 | $25,102 | $373,365 |

| Week 27 | 74.7 | $33,624 | $320,216 |

| Week 28 | 66 | $23,532 | $262,749 |

| Week 29 | 56.5 | $20,198 | $208,229 |

| Week 30 | 47.8 | $20,601 | $167,017 |

| Week 31 | 38.5 | $20,918 | $123,077 |

| Week 32 | 28.2 | $17,243 | $82,926 |

| Week 33 | 19.3 | $16,551 | $54,206 |

| Week 34 | 7.4 | $14,078 | $18,944 |

| Week 35 | 4.7 | $12,320 | $10,802 |

| Week 36 | 3.3 | $9,421 | $6,193 |

| Week 37 | 2.6 | $4,290 | $3,537 |

| Source | Phibbs and Schmitt (2006) | Underwood (2007) | Phibbs and Schmitt (2006) |

Abbreviation: LOS, length of stay.

A univariate sensitivity analysis was performed to identify the most influential variables impacting direct medical and total costs. The average costs and average RRs across the GAs were varied by ± 20%, with the assumption that the distribution of inputs across the weeks of GA did not change (see Supplemental Digital Content 5 [online only] for further univariate sensitivity analysis details). Threshold analyses were also performed to determine the hypothetical maximum or minimum values of influential variables where the model remains cost neutral. The threshold of each selected variable was tested while the remaining variables were held constant at the base case value. In addition, a probabilistic sensitivity analysis was performed using a Monte Carlo approach based on 5,000 randomly generated simulations of parameter values. Clinical inputs assumed a uniform distribution with the exception of the efficacy of vaginal progesterone, which was assumed to have a lognormal distribution. Costs assumed a gamma distribution.

Results

Of the 3,528,593 women who received the novel prognostic test, 913,200 (25.8%) had a positive result (276,642 true positives and 636,558 false positives) and were identified as being at risk for having a spontaneous preterm birth. The rate of spontaneous preterm births in the predictive arm was 9.1% compared with 9.8% in the baseline arm, a reduction of 23,430 preterm births (Table 4). In addition, the predictive arm shifted 30,971 (20.2% of spontaneous preterm birth) births from < 35 weeks of gestation to 35+ weeks as compared with the baseline arm. The average GA of infants born spontaneously preterm in the predictive arm was 34.4 versus 34.1 weeks in the baseline care scenario.

Table 4. GA at birth—base case.

| GA (wk) | Baseline care scenarioa | Prognostic scenariob | Difference | Percent changec |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| < 23 | 5,206 | 5,206 | – | – |

| 23 | 2,330 | 1,570 | 761 | 33% |

| 24 | 3,211 | 2,252 | 1,060 | 32% |

| 25 | 3,767 | 2,568 | 1,181 | 31% |

| 26 | 4,297 | 2,977 | 1,320 | 31% |

| 27 | 5,042 | 3,509 | 1,533 | 30% |

| 28 | 6,324 | 4,503 | 1,821 | 29% |

| 29 | 7,890 | 5,744 | 2,146 | 27% |

| 30 | 10,522 | 7,828 | 2,694 | 26% |

| 31 | 13,570 | 10,313 | 3,257 | 24% |

| 32 | 18,612 | 14,433 | 4,169 | 22% |

| 33 | 27,340 | 22,090 | 5,249 | 19% |

| 34 | 45,165 | 39,384 | 5,781 | 13% |

| 35 | 70,122 | 67,868 | 2,244 | 3% |

| 36 | 122,314 | 132,099 | 9,785 | 8% |

| Total spontaneous preterm birth | 345,802 | 322,372 | 23,430 | 6.8% |

| Induced preterm labor | 61,274 | 61,274 | – | – |

| 37+ | 3,182,791 | 3,206,221 | 23,430 | 0.7% |

| Total | 3,528,593 | 3,528,593 | – | – |

| Average GA for spontaneous preterm births | 34.09 | 34.44 |

Abbreviation: GA, gestational age.

Represents the current birth rate at each gestational age in the absence of the prognostic test.

Represents the result of applying the average relative risk for preterm birth with the use of vaginal progesterone (as reported in trials) to 80% of the test-positive population; base case test performance is 80% sensitivity and 80% specificity.

Represents the percentage of difference in births occurring at each gestational age between the baseline care and prognostic scenarios.

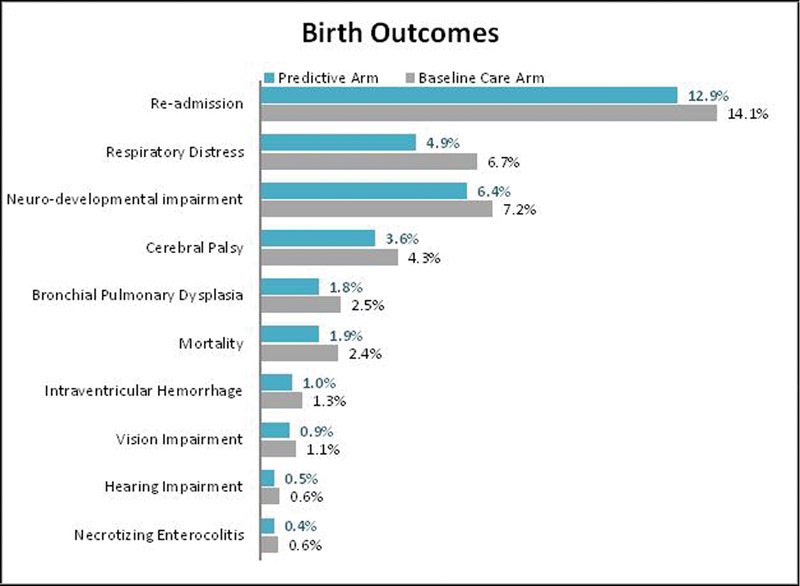

Reported clinical outcomes include surviving infants born spontaneously preterm. The results do not include nonspontaneous preterm births as the test will not have an impact in this population; therefore, it was assumed that the rate of nonspontaneous births would remain constant. Due to the increase in GA, average rates of infant mortality, acute conditions, and long-term disabilities were significantly reduced as shown in Fig. 1. The overall rate of acute conditions at birth including RDS, BPD, IVH, and NEC was decreased by 27.2%, a reduction from 11.2% in the baseline care arm to 8.1% in the predictive arm. Specifically, the rate of RDS decreased from 6.7% in the baseline arm to 4.9% in the predictive arm. The rate of BPD decreased from 2.5% in the baseline arm to 1.8% in the predictive arm; IVH and NEC saw smaller, yet relevant reductions in the predictive arm. Infant mortality decreased by 0.5% in the prognostic scenario.

Fig. 1.

Infant outcomes—base case. Outcomes focus on spontaneous preterm births only, the test does not impact nonspontaneous preterm births.

The overall rate of DDs including CP, neurodevelopment impairment, hearing impairment, and vision impairment decreased from 13.2% in the baseline care arm to 11.5% in the predictive arm. Specifically, the rate of CP decreased from 4.3% in the baseline arm to 3.6% in the predictive arm. Similarly, the rate of neurodevelopmental impairment decreased from 7.2 to 6.4%. Rates of vision and hearing impairment were also lower in the predictive versus the baseline arm.

The cost-benefit analysis demonstrated overall total cost savings (direct and total costs) of $1.49B (5.1%) in the predictive arm. Direct medical cost savings of $511.7M (2.1%) were realized due to a reduction in hospitalization and rehospitalization costs related to increasing the average GA (Table 5).

Table 5. Cost impact—base case.

| Cost | Baseline care | Novel prognostic test | Difference | Percent difference (cost savings) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Direct medical costs | $23,809,928,547 | $23,298,271,692 | $511,656,855 | 2.1% |

| Acute costs | $19,186,306,232 | $14,498,569,470 | $4,687,736,762 | 24.4% |

| First year nonacute medical costs | $4,623,622,315 | $4,108,608,639 | $515,013,676 | 11.1% |

| Prognostic test costs | – | $4,410,741,225 | $4,410,741,225 | – |

| Intervention costs | – | $280,352,358 | $280,352,358 | – |

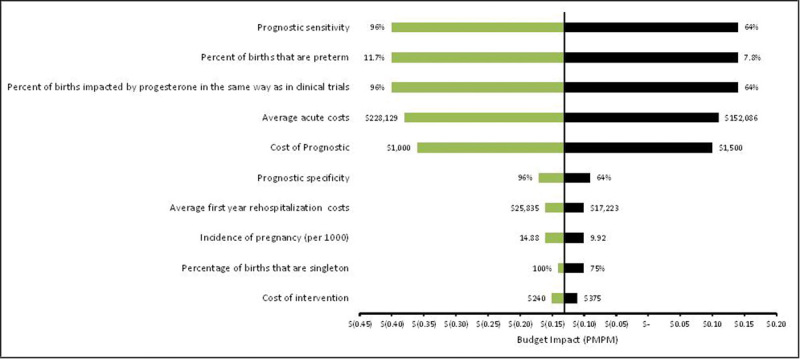

The univariate sensitivity analysis identified the prognostic test sensitivity as the most influential variable in the model. The 10 most impactful inputs are displayed in the resultant tornado diagram (Fig. 2). The prognostic testing cost is a key driver and largely unknown, as such a test is not currently available in the market. To determine the impact of the test cost and the cost of vaginal progesterone on the overall medical costs, a threshold analysis was performed. Model results were cost neutral at a prognostic test cost of $1,395, and became cost saving at any price below this. Model results were cost neutral at a cost of $867 for vaginal progesterone, and became cost savings at any cost below this. Due to the uncertainty of the impact of vaginal progesterone treatment on the model population, the impact of reducing the percentage of patients who responded similarly to those in the clinical trials was explored. The model was cost neutral assuming that at least 72.5% of test-positive women treated with vaginal progesterone in the model population respond similarly compared with women in the trial population; results became cost saving at higher response rates. Finally, threshold analysis was also conducted around the based case hypothesis to determine the impact of prognostic test sensitivity across a range of 50 to 90%; to account for the inverse relationship between sensitivity and specificity, the diagnostic odds ratio18 was used to adjust specificity based on changes in test sensitivity. Cost savings occur with prognostic test sensitivity slightly over 68% (Fig. 3) (see Supplemental Digital Content 6 [online only] for cost savings information based on test specificity).

Fig. 2.

Tornado plot of univariate sensitivity analysis (x-axis represents the cost impact per member for the prognostic scenario).

Fig. 3.

Threshold analysis for prognostic test sensitivity.

Across 5,000 iterations of simultaneously varying all inputs, the cost-benefit analysis was cost neutral or cost saving 62% of the time (Fig. 4). On average, 6.8% of births that would have been preterm in the baseline arm shift to full term in the predictive arm. Average incremental direct medical cost saving was $445.6M.

Fig. 4.

Probabilistic sensitivity analysis (negative values on the y-axis indicate cost savings).

Discussion

Reducing the rate and impact of preterm birth is part of a national agenda to reduce infant mortality (IM CoIIN).19 Additional mandates at the federal government level are also aimed at reducing the rate of fetal and infant deaths.20 Our model demonstrates that a novel test for identifying spontaneous preterm birth risk in women without a prior history of preterm birth could support improved infant outcomes and reduced the overall economic impact of preterm birth. The results represent a highly conservative estimate of the potential improvements in perinatal outcomes and cost savings in the first year of life associated with spontaneous preterm birth upon implementation of a novel prognostic test and subsequent intervention with vaginal progesterone. However, it is important to note that while this analysis focuses on the use of vaginal progesterone, it would apply for any intervention. Health policymakers, insurers, governmental agencies, test developers, and drug manufacturers may find the methodological framework useful to explore the impact of new technologies developed to address the enormous challenges of preterm birth.

A key limitation of the model is our conservative approach of limiting costs to a 1-year time horizon and the focus on acute medical costs incurred during this period. The model does not include other significant costs associated with long-term morbidities across the lifetime of the infant, out of pocket expenses or productivity losses for families of the preterm infants. Therefore, the actual societal costs associated with preterm birth are much higher than what the model currently considers, and we would expect to see significantly more savings if the time horizon was extended beyond the first year of life. To provide additional insight into the impact of other costs, a secondary analysis was conducted to explore the potential impact of the prognostic test on broader, nonmedical costs to society. The analysis provides a 1-year snapshot of additional annual costs to society associated with living individuals who were born preterm. Specifically, annual costs for early intervention services, special education, and lost productivity were compared in the predictive and baseline arms. In a 1-year period, these additional costs were decreased from $5.37B in the baseline arm to $4.39B in the predictive arm, an 18% reduction in nonmedical costs. Extension of this analysis over the lifetime of the cohort and including costs specific to each condition are needed to further understand the overall impact.

Another important limitation is that the exact underlying causes of spontaneous preterm birth and the mechanisms by which vaginal progesterone reduce spontaneous preterm birth risk are not completely understood. Although the use of vaginal progesterone has been shown to reduce the risk of spontaneous preterm birth in randomized clinical trials, these trials have focused on high-risk populations including women with a prior history of spontaneous preterm birth or with a clinically detected short cervix.17 The model attempts to account for the difference in population by reducing the number of women who would see a similar impact, as use of vaginal progesterone has not been studied in the broader population. However, it is possible that the efficacy and impact in our test population could be greater compared with existing data and assumptions. Theoretically, a highly accurate predictor of spontaneous preterm birth risk would identify women who would benefit most from intervention with vaginal progesterone resulting in more infants born at later stages of gestation and a larger cost reduction. Conversely, we also note that a significant number of false-positive women will be treated with vaginal progesterone in our model. These women will experience any potential risks associated with the treatment but no benefit. Although the safety profile of vaginal progesterone treatment is very reassuring, we cannot rule out the possibility that an unknown maternal or fetal risk might be identified in the future.

There are additional interventions that were not considered within the model but show promise. Seventeen-alpha-hydroxy-progesterone caproate (17P) has been shown to have a similar, or in some cases improved, impact on reducing spontaneous preterm birth risk compared with vaginal progesterone in clinical trials and therefore would be another viable option for a proposed intervention.21 However, ready access to 17P has varied across the country due to variations in availability at compounding pharmacies and coverage by insurance companies. Furthermore, while the actual cost of compounded 17P is less than $400 per pregnancy, the amount being charged and paid for 17P is often above $12,000 per pregnancy.22 In addition, it is possible that other emerging interventions, including clinical management programs such as high-intensity case management or group prenatal care, could provide enhanced opportunities to further increase GA at birth and improve birth outcomes.23 24 Ultimately, an effective and accurate method for identifying women at risk for spontaneous preterm birth will enable further study of emerging or novel interventions to reduce the risk of spontaneous preterm birth.

The analysis is also limited by the current data on preterm birth outcomes. Although the model considers the cost impact of key acute outcomes and long-term disabilities resulting from preterm birth, it does not consider other outcomes such as behavioral issues and chronic pulmonary conditions which have not been well studied, but are assumed to impact a significant percentage of preterm infants.25 26 Further consideration of these additional adverse outcomes would enable a broader perspective of the full impact of reducing spontaneous preterm birth.

In addition, our preterm birth study population was limited to 23 weeks of gestation and beyond to ensure that the model focused on the population where an intervention would have an impact. According to the current literature, the definition of preterm birth is contentious and still evolving3; however, infants are generally not considered viable before 22 weeks of gestation and the risk of mortality at 22 weeks is still high.4 Although clinical management guidelines for preterm infants vary across physicians and hospitals, active intervention and resuscitation are uncommon for infants born at 22 weeks or less but increases for those born at 23 weeks due to a higher chance for survival.27 Therefore, it would be less likely to see impactful increases in GA for births prior to 23 weeks in our model.

The model population is further limited to births defined as spontaneous preterm birth based on the current CDC reported rate for spontaneous preterm birth. The CDC reports the incidence of indicated (or induced) preterm births separately from spontaneous preterm births, thereby which spontaneous preterm birth accounts for 89.6% of all preterm births; although a standardized method for classifying preterm birth as spontaneous or indicated does not yet exist. A spontaneous preterm birth is the result of spontaneous labor with intact membranes or preterm premature rupture of the membranes, while an indicated preterm delivery involves induced labor or cesarean section for the purpose of maternal or fetal benefit. However, indicated preterm birth can be the result of conditions having a “spontaneous” origin, such as infection cause by ruptured membranes.3 28 Therefore, the novel test may also identify births currently classified as indicated preterm births if they have a spontaneous origin, thus having a wider impact than considered in the current model. The present analysis suggests that further research is needed to understand the clinical potential of a novel blood test for identifying spontaneous preterm birth risk.

In conclusion, we present these results as a conservative starting point for evaluating such a test. In addition, our sensitivity analysis provides a good foundation for determining the future impact and clinical requirements.

Acknowledgments

Sera Prognostics Inc. provided GfK with financial support to manage the study. The authors, or their respective universities, received unrestricted research funds or honorary payment through GfK to provide expert consultation and article development.

Disclosures The authors provided expert consultation to GfK, a global health care consultancy, on the development of the economic model and article. GfK consultants, Deanna Hertz, Laura Zelle, Susan Garfield* and Amanda DiPaolo were contracted by Sera Prognostics Inc. to manage the study, which included leading the development of the analysis and article. However, the analysis and publication of the article were not contingent on the sponsor's approval, review, or revision.

At the time of writing, Dr. Garfield was employed by GfK. However, she has since moved to Ernst & Young and has received no financial compensation associated with the development or publication of this article.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1.World Bank . Washington, D.C.: World Bank Group; 2014. Levels and Trends in Child Mortality: Estimates Developed by the UN Inter-Agency Group for Child Mortality Estimation (IGME) [Google Scholar]

- 2.Goldenberg R L, Gravett M G, Iams J. et al. The preterm birth syndrome: issues to consider in creating a classification system. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2012;206(2):113–118. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2011.10.865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Martin J, Hamilton B, Osterman M, Curtin S, Mathews T. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2015. Births: Final Data For 2013. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stoll B J, Hansen N I, Bell E F. et al. Trends in care practices, morbidity, and mortality of extremely preterm neonates, 1993-2012. JAMA. 2015;314(10):1039–1051. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.10244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Behrman R, Butler A. Washington, D.C.: National Academies Press; 2007. Preterm Birth. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Phibbs C S, Schmitt S K. Estimates of the cost and length of stay changes that can be attributed to one-week increases in gestational age for premature infants. Early Hum Dev. 2006;82(2):85–95. doi: 10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2006.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Iams J D Cebrik D Lynch C Behrendt N Das A The rate of cervical change and the phenotype of spontaneous preterm birth Am J Obstet Gynecol 201120521300–130..e6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Iams J D Grobman W A Lozitska A et al. Adherence to criteria for transvaginal ultrasound imaging and measurement of cervical length Am J Obstet Gynecol 201320943650–365..e5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Parry S, Elovitz M A. Pros and cons of maternal cervical length screening to identify women at risk of spontaneous preterm delivery. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2014;57(3):537–546. doi: 10.1097/GRF.0000000000000051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Berghella V, Blackwell S, Anderson B, Chauhan S, Copel J, Gyamfi C. et al. Progesterone and preterm birth prevention: translating clinical trials data into clinical practice. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2012;206(5):376–386. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2012.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Committee on Practice Bulletins—Obstetrics, The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists . Practice bulletin no. 130: prediction and prevention of preterm birth. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;120(4):964–973. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3182723b1b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Orzechowski K M, Boelig R C, Baxter J K, Berghella V. A universal transvaginal cervical length screening program for preterm birth prevention. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;124(3):520–525. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000000428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Laughon S K Albert P S Leishear K Mendola P The NICHD Consecutive Pregnancies Study: recurrent preterm delivery by subtype Am J Obstet Gynecol 201421021310–131..e8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.U.S. Department of Commerce American FactFinder - Results Factfindercensusgov. 2015. Available at: http://factfinder.census.gov/faces/tableservices/jsf/pages/productview.xhtml?src=bkmk. Accessed July 8, 2015

- 15.Petrini J R, Callaghan W M, Klebanoff M. et al. Estimated effect of 17 alpha-hydroxyprogesterone caproate on preterm birth in the United States. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;105(2):267–272. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000150560.24297.4f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Romero R Nicolaides K Conde-Agudelo A et al. Vaginal progesterone in women with an asymptomatic sonographic short cervix in the midtrimester decreases preterm delivery and neonatal morbidity: a systematic review and metaanalysis of individual patient data Am J Obstet Gynecol 201220621240–124..e19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Data Access - VitalStats - Homepage Cdcgov. 2015. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/vitalstats.htm. Accessed July 8, 2015

- 18.Genders T S, Meijboom W B, Meijs M F. et al. CT coronary angiography in patients suspected of having coronary artery disease: decision making from various perspectives in the face of uncertainty. Radiology. 2009;253(3):734–744. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2533090507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.National Institute for Children's Health Quality NICHQ.Org | Collaborative Improvement and Innovation Network to Reduce Infant Mortality (IM CoIIN) Nichqorg. 2015. Available at: http://www.nichq.org/childrens-health/infant-health/coiin-to-reduce-infant-mortality. Accessed October 23, 2015

- 20.Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. Maternal, Infant, and Child Health | Healthy People 2020 Healthypeoplegov. 2015. Available at: https://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topics-objectives/topic/maternal-infant-and-child-health/objectives. Accessed November 16, 2015

- 21.Meis P J, Klebanoff M, Thom E. et al. Prevention of recurrent preterm delivery by 17 alpha-hydroxyprogesterone caproate. N Engl J Med. 2003;348(24):2379–2385. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa035140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.analysource.com AnalySource - Your complete Drug Database and Analysis Power Tool.Www1analysourcecom 2015. Available at: https://www1.analysource.com/qry/as_products.taf?_nc=61d5a429673fe1cc012d9e5597286541. Accessed November 30, 2015

- 23.Goyal N K, Hall E S, Meinzen-Derr J K. et al. Dosage effect of prenatal home visiting on pregnancy outcomes in at-risk, first-time mothers. Pediatrics. 2013;132 02:S118–S125. doi: 10.1542/peds.2013-1021J. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Picklesimer A H Billings D Hale N Blackhurst D Covington-Kolb S The effect of CenteringPregnancy group prenatal care on preterm birth in a low-income population Am J Obstet Gynecol 201220654150–415..e7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Delobel-Ayoub M, Kaminski M, Marret S. et al. Behavioral outcome at 3 years of age in very preterm infants: the EPIPAGE study. Pediatrics. 2006;117(6):1996–2005. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-2310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pryhuber G S, Maitre N L, Ballard R A. et al. Prematurity and respiratory outcomes program (PROP): study protocol of a prospective multicenter study of respiratory outcomes of preterm infants in the United States. BMC Pediatr. 2015;15(1):37. doi: 10.1186/s12887-015-0346-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Smith P B, Ambalavanan N, Li L. et al. Approach to infants born at 22 to 24 weeks' gestation: relationship to outcomes of more-mature infants. Pediatrics. 2012;129(6):e1508–e1516. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-2216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Goldenberg R L Culhane J F Iams J D Romero R Epidemiology and causes of preterm birth Lancet 2008. Jan 5;371960675–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cahill A, Odibo A, Caughey A. et al. Universal cervical length screening and treatment with vaginal progesterone to prevent preterm birth: a decision and economic analysis. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2010;202(6):5480–5.48E10. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2009.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Larroque B, Ancel P, Marret S. et al. Neurodevelopmental disabilities and special care of 5-year-old children born before 33 weeks of gestation (the EPIPAGE study): a longitudinal cohort study. The Lancet. 2008;371(9615):813–820. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60380-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.van Dommelen P, Verkerk P, van Straaten H. Hearing Loss by Week of Gestation and Birth Weight in Very Preterm Neonates. The Journal of Pediatrics. 2015;166(4):840–8430. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2014.12.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stoll B, Hansen N, Bell E. et al. Neonatal Outcomes of Extremely Preterm Infants From the NICHD Neonatal Research Network. PEDIATRICS. 2010;126(3):443–456. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-2959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Underwood M, Danielsen B, Gilbert W. Cost, causes and rates of rehospitalization of preterm infants. Journal of Perinatology. 2007;27(10):614–619. doi: 10.1038/sj.jp.7211801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.