Case report

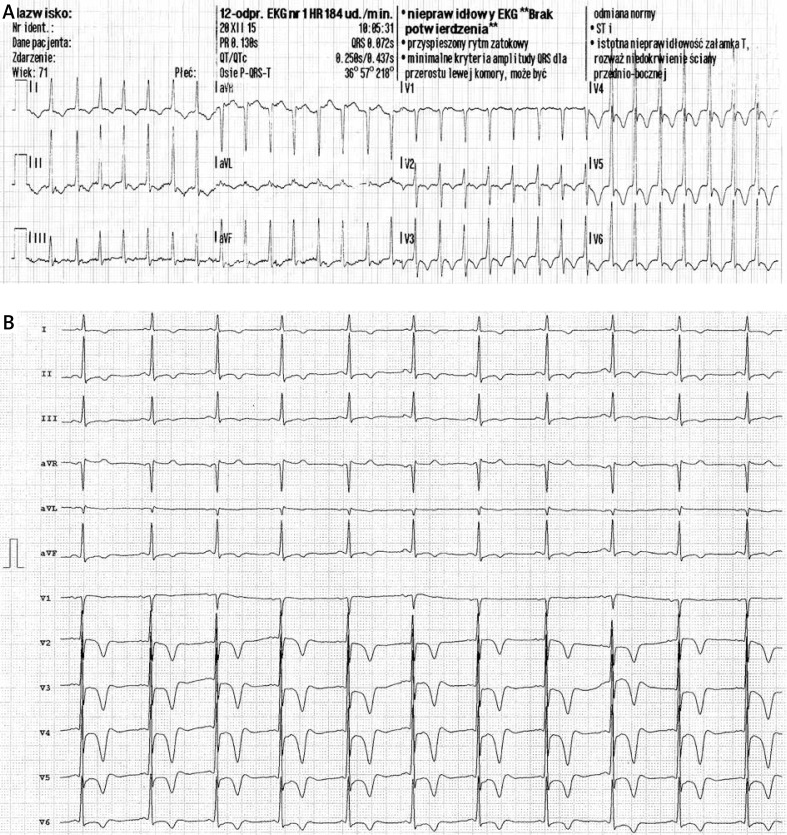

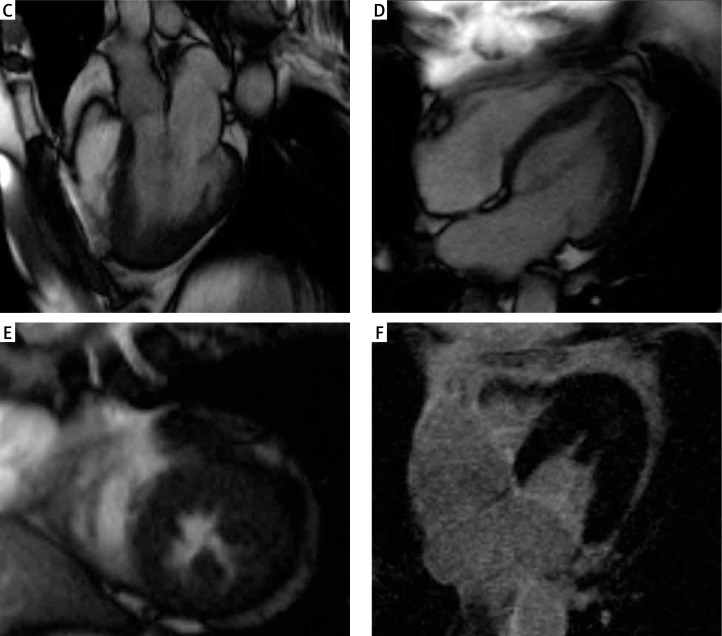

A 72-year-old female patient with a history of hypertension was admitted to the hospital with suspicion of non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndrome. On ECG, left ventricle hypertrophy and negative T waves in V2–V6 were present. Levels of cardiac enzymes were markedly increased with troponin (Tn) I at admission 2.06 µg/l and with a subsequent drop to values of 0.99 µg/l and 0.71 µg/l. Renal function parameters were normal. She did not complain of chest pain, but due to long lasting diabetes treated with insulin silent myocardial ischemia was suspected. At admission, an episode of supraventricular tachycardia with a heart rate of 180 beats per minute was detected (Figure 1 A). Negative T waves in V2–V6 (Figure 1 B), increased troponin level and long-lasting diabetes as a risk factor for atherosclerosis with potential silent ischemia were indicators for coronary angiography. In urgent coronary angiography no significant coronary artery stenoses were confirmed. The tentative diagnosis of myocardial ischemia/injury due to epicardial coronary artery disease became doubtful. Transthoracic echocardiography was technically difficult due to suboptimal acoustic condition for the imaging. All heart valves were normal. Both ventricles and atria were non-dilated. Ejection fraction was 70%. The intraventricular septum at the basal segment was non-thickened (end systole 13 mm, end diastole 8 mm). Thickness of posterior wall was normal (end systole 14 mm, end diastole 7 mm). Importantly, the apical segment of the intraventricular septum was hypertrophied (15–16 mm at end diastole; quality of imaging was suboptimal) suggesting the apical form of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM). In Doppler echocardiography moderate pulmonary hypertension was detected. To confirm the presence of apical HCM cardiac magnetic resonance (CMR) with contrast agent (gadolinium) was performed. Cardiac magnetic resonance examination confirmed apical hypertrophy and excluded either ischemic injury or fibrotic area of myocardium due to lack of regions of late contrast enhancement (Figures 1 C–F). No ventricular arrhythmias were observed in the ECG Holter recording. Both family history of sudden cardiac death and past history of syncope were negative.

Figure 1.

A – Supraventricular tachycardia at admission with negative T waves in V2–6. B – Sinus rhythm with negative T waves in V2–6. Cine steady-state free precession cardiac magnetic resonance images in three-chamber (C) and four-chamber (D) apical long axis views as well in short axis (E) apical view. Late gadolinium enhancement imaging (F) excluded the presence of acute ischemic injury and myocardial fibrosis. Note the presence of myocardial hypertrophy in the apical segment of the lateral and anterior wall. The left ventricular ejection fraction was 83%, end-diastolic volume 79 ml, end-systolic volume 14 ml, stroke volume 65 ml, and myocardial mass 92 g

Discussion

Cardiac magnetic resonance is a very useful diagnostic modality in patients with non-definitive HCM due to technical difficulties in echocardiographic imaging. In about 20% of patients suspected with HCM the diagnosis is confirmed by CMR, especially when hypertrophy is localized in the apex or in the lateral wall.

An increased (even persistently) level of troponin in HCM has been reported in several papers. A recent study [1] showed that high sensitive troponin T (hs-TnT) was detectable in three-quarters and elevated in one-quarter of patients with HCM. Thus positive troponin test is a frequent phenomenon in HCM. In obstructive HCM, TnI is correlated with left ventricular (LV) hypertrophy [2], and this biomarker is an independent predictor of the presence of myocardial fibrosis in CMR [3]. In our patient with apical HCM and an elevated level of TnI, late enhancement was absent and LV hypertrophy was relatively mild, limited to the apical region.

Interestingly, in the latest study of consecutive referrals of patients with suspected/known HCM to large tertiary centers, 18% of patients presented with apical HCM phenotype [4]. Traditionally, apical HCM has been considered a rare variant of HCM, with a prevalence of approximately 7% and known more benign prognosis and lower risk of SCD [5].

Previously, it has been documented in HCM [6] that increased troponin release may be present in such patients and is temporarily enhanced by exercise and decreased with β-blockade. Probably in our patient supraventricular tachycardia mimics exercise and may be responsible for the increase of troponin.

Summing up, physicians should be aware of apical HCM in the case of patients with symptoms suggestive of acute coronary syndrome (electrocardiographic changes, chest pain at rest, positive troponin test) and normal or near-normal coronary angiography. The lack of late enhancement in contrast CMR may be a useful non-invasive method to exclude myocardial infarct.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Cramer G, Bakker J, Gommans F, et al. Relation of highly sensitive cardiac troponin T in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy to left ventricular mass and cardiovascular risk. Am J Cardiol. 2014;113:1240–5. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2013.12.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhang C, Liu R, Yuan J, et al. Predictive values of N-terminal pro-B-type natriuretic peptide and cardiac troponin I for myocardial fibrosis in hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0146572. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0146572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhang C, Liu R, Yuan J, et al. Significance and determinants of cardiac troponin I in patients with obstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Am J Cardiol. 2015;116:1744–51. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2015.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ismail TF, Jabbour A, Gulati A, et al. Role of late gadolinium enhancement cardiovascular magnetic resonance in the risk stratification of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. Heart. 2014;100:1851–8. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2013-305471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Eriksson MJ, Sonnenberg B, Woo A, et al. Long-term outcome in patients with apical hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2002;39:638–45. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(01)01778-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pop GA, Cramer E, Timmermans J, et al. Troponin I release at rest and after exercise in patients with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy and the effect of betablockade. Arch Cardiol Mex. 2006;76:415–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]