Abstract

Objectives

Echocardiography is a sensitive test for rheumatic heart disease (RHD) screening; however the natural history of RHD detected on screening has not been established. We aimed to evaluate the progression of screening-detected RHD in Fiji.

Methods

All young people previously diagnosed with RHD through screening, with echocardiograms available for review, were eligible. All baseline echocardiograms were reported again. Participants underwent follow-up echocardiography. A paediatric cardiologist determined the diagnosis using the World Heart Federation criteria and assessed the severity of regurgitation and stenosis.

Results

Ninety-eight participants were recruited (mean age, 17 years; median duration of follow-up, 7.5 years). Two other children had died from severe RHD. Fourteen of 20 (70%) definite RHD cases persisted or progressed, including four (20%) requiring valve surgery. Four (20%) definite RHD cases improved to borderline RHD and two (10%) to normal. Four of 17 (24%) borderline cases progressed to definite RHD (moderate: 2; severe: 2) and two (12%) improved to normal. Four of the 55 cases reclassified as normal at baseline progressed to borderline RHD. Cases with a follow-up interval >5 years were more likely to improve (37% vs 6%, p=0.03).

Conclusions

The natural history of screening-detected RHD is not benign. Most definite RHD cases persist and others may require surgery or succumb. Progression of borderline cases to severe RHD demonstrates the need for monitoring and individualised consideration of prophylaxis. Robust health system structures are needed for follow-up and delivery of secondary prophylaxis if RHD screening is to be scaled up.

Introduction

Rheumatic heart disease (RHD) remains a major cause of global morbidity and mortality, affecting in excess of 30 million people and causing over 345 000 deaths annually.1 Most patients in resource-limited settings present with advanced disease and complications2 3 and therefore prognosis at the time of diagnosis is poor.4 Echocardiography has been shown to be a highly sensitive test for RHD,5 raising the possibility that a population-based screening programme could identify cases earlier and improve disease outcomes through secondary antibiotic prophylaxis. Formulation of appropriate screening policy requires an understanding of the history of echocardiographic changes over time and how these changes correlate with the risk of developing clinical complications.6

Criteria for the echocardiographic diagnosis of RHD, in individuals without a history of rheumatic fever, have developed over time, culminating in evidence-based criteria produced by the World Heart Federation (WHF) in 2012.7 The WHF criteria defined ‘definite RHD’ on the basis of functional and morphological changes to the heart valves, and also introduced the category of ‘borderline RHD’ where the complete criteria are not fulfilled. The borderline RHD group includes individuals with true, early RHD and others with non-pathological echocardiographic findings,8 9 although it is not known if there are identifiable risk markers to differentiate these populations. In many settings, individuals with borderline RHD have not been commenced on prophylaxis.10 If a large proportion of the borderline group indeed have true, latent RHD (ie, likely to develop clinical disease and likely to benefit from prophylaxis) then the case for screening would be more compelling. On the other hand, the magnitude of the health system response required to treat and follow-up cases would be greatly increased.

Data of echocardiographic progression of cases detected through screening, using the WHF criteria, are limited by small samples and brief follow-up times.11–13 Therefore, we aimed to investigate the changes in echocardiographic findings in a group of children and young people diagnosed with RHD through screening, and to evaluate possible risk and protective factors for disease progression.

Methods

Setting

The study took place in Fiji, a nation of 332 islands in the South Pacific region with a population of approximately 900 000. Fiji has a very high burden of RHD, with a prevalence of definite RHD of 7–8 per 1000 on echocardiographic screening of school-aged children.14 15 RHD is one of the leading causes of mortality in children and young adults.16 The Fiji Ministry of Health and Medical Services operates a register-based RHD control programme. The Ministry has conducted echocardiographic screening of school-aged children sporadically since 2008. Children diagnosed with RHD were recommended secondary antibiotic prophylaxis using intramuscular benzathine penicillin G (BPG). Those with uncertain diagnosis, including those with borderline RHD diagnosed since 2012, are counselled, but most were not commenced on prophylaxis. Surgical intervention is provided by fly-in/fly-out cardiac surgical teams,17 or occasionally via international evacuation.

Participants

All young people with any form of RHD diagnosed on echocardiography (ie, ‘probable’ or ‘definite’ RHD using criteria from the National Institutes for Health and WHO (NIH-WHO),18 or ‘borderline’ or ‘definite’ RHD using WHF criteria) during previous screening studies in Fiji from 2006 to 201314 15 19 20 were eligible to participate. Research staff contacted eligible families with an invitation to participate and provided verbal and written information regarding study procedures. Signed informed consent was obtained from participants, or from a parent or guardian for those aged less than 18 years. Signed assent was additionally obtained for participants aged 10 years and above.

Follow-up assessment

Assessments were completed across 15 days, at six hospitals and health centres from August to November 2015. Age, sex, height and weight were recorded. Information on adherence to secondary prophylaxis was manually collected from clinic injection records, as reported elsewhere.21 Adherence was defined as the proportion of recommended BPG injections received from December 2011 to December 2014. Echocardiography was performed by an experienced sonographer. A Vivid q or Vivid e machine (GE Healthcare, Freiburg, Germany) was used with a 1–5 MHz or 1.7–4 MHz transducer. Machine settings and measurements were as per WHF guidelines.7 Deidentified images were saved for offsite reporting.

Echocardiographic reporting

A paediatric cardiologist, experienced in the echocardiographic diagnosis of RHD, reported all studies, blinded to any clinical information or the original diagnosis. Diagnosis was made according to the WHF criteria, into categories of definite RHD; borderline RHD; congenital or other non-RHD; and normal. Definite and borderline RHD were further classified by the WHF criteria subcategories.7 In addition, we identified a subset of normal cases with non-specific valvular abnormalities (NSVA) on echocardiography, defined as: a single morphological feature of the mitral valve; ≥1 morphological feature of aortic valve; non-pathological mitral regurgitation (MR) with jet length ≥2 cm; or non-pathological aortic regurgitation with jet length ≥1 cm.

As the WHF criteria were developed for diagnosis of cases without a history of rheumatic fever, and not for follow-up of known cases, several modifications were necessary. Disease criteria for those aged ≤20 years were used for participants of all ages, in order to ensure consistent classification of borderline disease. Cases with a history of surgical intervention for RHD were classified as severe, definite RHD. Some baseline echocardiograms performed prior to 2012 did not contain the spectral Doppler views necessary to apply the WHF criteria, and in these cases we used modified criteria to categorise pathological regurgitation using colour Doppler views.22 Assessment of the severity of regurgitation and stenosis was based on previously published recommendations.23–25

Progression was defined as an increase in diagnostic category (ie, from normal to borderline or definite RHD; or from borderline to definite RHD), an increase in severity for definite RHD cases (eg, from mild to moderate) or the requirement for valve surgery. The report of the same cardiologist was used to assess progression. A subset of echocardiograms was reported by a second paediatric cardiologist to assess inter-rater agreement.

Echocardiography results for all participants were discussed with clinical services at the local tertiary referral hospital. Participants with any abnormality on echocardiogram, or who had ever been diagnosed or treated for RHD, were referred for further assessment and counselling with the paediatric or adult cardiology unit. Other participants were notified of a normal result by phone, and offered follow-up with clinical services.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to summarise disease progression and improvement. Evaluation of risk factors for disease persistence and progression used Fisher's exact test for categorical variables and the Mann-Whitney U test for continuous variables. Cohen's κ statistic was used to evaluate the inter-rater agreement of diagnosis between the reporting cardiologists. Deidentified data were analysed using Stata V.14 (Stata Corp, Texas, USA).

Results

One hundred and thirty-four potential RHD cases with echocardiograms available for review were identified. Ninety-eight participants completed a follow-up echocardiogram (table 1). The reasons for non-participation were: known relocation or migration (n=17), unavailability on follow-up clinic dates (n=7), uncontactable (n=7), declined to participate (n=2) and deceased (n=3, including 2 due to severe RHD). The median age of participants at follow-up was 17 years. The median duration of follow-up was 7.5 years; 67% were female, 65% from a rural area and 82% were iTaukei (indigenous Fijian). Very few cases (2%) received adequate antibiotic prophylaxis to protect against disease progression.

Table 1.

Participant characteristics

| Characteristic | |

|---|---|

| Median age at screening (IQR), years | 10.4 (8.5–12.0) |

| Median age at follow-up (IQR), years | 17.0 (14.6–19.3) |

| Median duration of follow-up (IQR), years | 7.5 (2.7–7.7) |

| Gender—n (%) | |

| Female | 66 (67.4) |

| Ethnicity—n (%) | |

| iTaukei | 80 (81.6) |

| Fijian of Indian descent | 17 (17.4) |

| Other | 1 (1.0) |

| Residence—n (%) | |

| Urban | 34 (34.7) |

| Rural | 64 (65.3) |

| Secondary antibiotic prophylaxis—n (%) | 58 (59.2) |

| Not commenced | 40 (40.8) |

| Adherence 0% | 23 (23.5) |

| Adherence 1%–49% | 23 (23.5) |

| Adherence 50%–79% | 6 (6.1) |

| Adherence ≥80% | 2 (2.0) |

| Data unavailable | 4 (4.1) |

| Total | 98 |

Echocardiographic diagnosis

After reporting all baseline echocardiograms again, 20 were classified as definite RHD, 17 as borderline RHD and 55 were reported to be normal using WHF criteria, including 23 with one or more NSVA. There were six cases of congenital disease. Details of echocardiographic diagnosis at baseline and follow-up are shown in table 2. A second cardiologist reported on 95 of the baseline and follow-up echocardiograms (48%). The agreement on diagnosis between reporters was moderate (κ 0.59 for definite RHD; 0.56 for any RHD).

Table 2.

Diagnosis on baseline and follow-up echocardiography

| Diagnosis | Details (subcategory) | Baseline, n | Follow-up, n |

|---|---|---|---|

| Definite RHD | 20 (20.4%) | 18 (18.4%) | |

| A: Pathological MR with morphological features of MV | 11 | 9 | |

| B: Mitral stenosis | 2 | 3 | |

| C: Pathological AR with morphological features of AV | 5 | 5 | |

| D: Borderline disease of AV and MV | 2 | 1 | |

| Borderline RHD | 17 (17.4%) | 19 (19.4%) | |

| A: Morphological features of MV | 0 | 3 | |

| B: Pathological MR | 13 | 15 | |

| C: Pathological AR | 4 | 1 | |

| Normal with NSVA* | 21 (21.4%) | 25 (25.5%) | |

| Morphological feature of MV | 8 | 4 | |

| Morphological feature of AV | 0 | 1 | |

| MR ≥2 cm | 11 | 20 | |

| AR ≥1 cm | 6 | 6 | |

| Normal without NSVA | 34 (34.7%) | 30 (30.6%) | |

| Congenital† | 6 (6.1%) | 6 (6.1%) | |

| Total | 98 | 98 |

*NSVAs are not mutually exclusive.

†Details of congenital cases: bicuspid aortic valve (n=2), mitral valve prolapse (n=2), subarterial ventricular septal defect with aortic valve prolapse (n=1), dilated coronary sinus with persistent left superior vena cava (n=1).

AR, aortic regurgitation; AV, aortic valve; MR, mitral regurgitation; MV, mitral valve; NSVAs, non-specific valvular abnormalities; RHD, rheumatic heart disease.

Change in echocardiographic diagnosis at follow-up

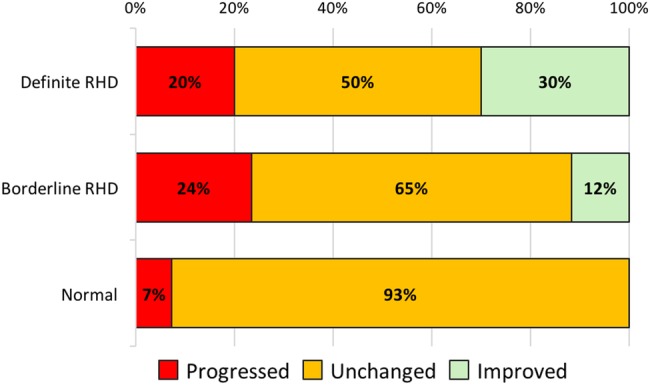

Of the 20 cases with definite RHD at baseline, 14 (70%) had definite RHD on follow-up, 4 (20%) improved to borderline RHD and 2 (10%) improved to normal (table 3, figure 1). Improvement was observed in four of eight (50%) mild RHD cases and two of nine (22%) moderate RHD cases. Four cases (20%) had evidence of valve surgery on follow-up echocardiography.

Table 3.

Change in diagnosis from baseline to follow-up

| Diagnosis at follow-up |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diagnosis at baseline | Definite RHD | Borderline RHD | Normal with NSVA | Normal without NSVA | Congenital | Total (baseline) |

| Definite RHD | 14 (70.0) | 4 (20.0) | 1 (5.0) | 1 (5.0) | 0 | 20 |

| Borderline RHD | 4 (23.5) | 11 (64.7) | 1 (5.9) | 1 (5.9) | 0 | 17 |

| Normal with NSVA | 0 | 1 (4.8) | 15 (71.4) | 5 (23.8) | 0 | 21 |

| Normal without NSVA | 0 | 3 (8.8) | 8 (23.5) | 23 (67.6) | 0 | 34 |

| Congenital | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 (100) | 6 |

| Total (follow-up) | 18 | 19 | 25 | 30 | 6 | 98 |

RHD, rheumatic heart disease; NSVA, non-specific valvular abnormality.

Figure 1.

Change in echocardiographic diagnosis at follow-up, compared with baseline rheumatic heart disease (RHD). Progression of definite RHD cases indicates increased disease severity or valve surgery.

Of the 17 cases with borderline RHD at baseline, 4 (24%) progressed to definite RHD (2 moderate and 2 severe). All four cases had pathological regurgitation of the mitral valve (borderline RHD, subcategory B) at baseline. Two other borderline RHD cases (12%) improved to normal (both also subcategory B). Four of 55 cases classified as normal at baseline progressed to borderline RHD. One of these cases had an NSVA at baseline (aortic regurgitation that progressed to pathological). No normal cases progressed to definite RHD. The reasons for the change in diagnosis for cases diagnosed with definite RHD are shown in table 4.

Table 4.

Reason for change in diagnosis in patients with definite RHD at baseline or follow-up

| Baseline |

Follow-up |

Reason for change in diagnosis | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diagnosis | Detailed findings | Diagnosis | Detailed findings | |

| (A) Improvement | ||||

| Definite RHD A | Pathological MR—moderate AMVL thickening Excessive leaflet tip motion of MV |

Borderline RHD B* | Pathological MR—mild AMVL thickening |

Resolution of excessive tip motion |

| Definite RHD D | Pathological MR—moderate Pathological AR |

Borderline RHD B | Pathological MR—mild | No AR |

| Definite RHD C | Pathological AR—mild AV thickening Coaptation defect of AV |

Normal with NSVA | AR—not pathological (not high velocity or pan-diastolic) | AR not pathological Resolution of morphological features |

| Definite RHD A | Pathological MR—mild AMVL thickening Restricted leaflet motion of MV |

Borderline RHD A | MR—not pathological (not pan-systolic) AMVL thickening Restricted leaflet motion of MV |

MR not pathological |

| Definite RHD A | Pathological MR—mild Pathological AR AMVL thickening Restricted leaflet motion of MV |

Normal | None | Resolution of all findings |

| Definite RHD A | Pathological MR—mild AMVL thickening Restricted leaflet motion of MV |

Borderline RHD A | MR—not pathological (not pan-systolic) AMVL thickening Restricted leaflet motion of MV |

MR not pathological |

| (B) Progression | ||||

| Borderline RHD B | Pathological MR—moderate AMVL thickening |

Definite RHD A | Pathological MR—severe AMVL thickening Excessive leaflet tip motion of MV |

Developed one additional morphological feature |

| Borderline RHD C | Pathological AR—severe | Definite RHD C | Pathological AR—severe Coaptation defect of AV Prolapse of AV |

Developed two morphological features |

| Borderline RHD B | Pathological MR—mild | Definite RHD A | Pathological MR—moderate Pathological AR AMVL thickening Restricted leaflet motion of MV |

Developed two morphological features Also developed pathological AR |

| Borderline RHD B | Pathological MR—mild | Definite RHD A | Pathological MR—moderate Pathological AR AMVL thickening Restricted leaflet motion of MV |

Developed two morphological features Also developed pathological AR |

*Participant was 22 years age at follow-up and using WHF criteria for individuals aged >20 years would be classified as ‘normal’.

AMVL, anterior mitral valve leaflet; AR, aortic regurgitation; AV, aortic valve; MR, mitral regurgitation; MV, mitral valve; NSVA, non-specific valvular abnormality; RHD, rheumatic heart disease; WHF, World Heart Federation.

Factors associated with echocardiographic improvement

Of the 37 cases with definite or borderline RHD at baseline, 29 (78%) persisted or progressed and 8 (21%) improved in diagnostic category. Cases with an interval of >5 years since screening were more likely to improve (37% compared with 6%, p=0.03). Further analysis of potential risk and protective factors was limited by the sample size, but no other associations were found (table 5).

Table 5.

Risk factors for disease persistence and progression in participants with definite or borderline RHD at baseline

| Persisted or progressed, N=29 (78.4%) |

Improved, N=8 (21.6%) |

Risk difference, % (95% CI) |

p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic | ||||

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 9 (75) | 3 (25) | 5.0 (−24.1 to 34.1) | 0.52 |

| Female | 20 (80) | 5 (20) | ||

| Ethnicity | ||||

| iTaukei | 26 (78.8) | 7 (21.2) | −3.8 (−48.5 to 40.9) | 0.64 |

| Fijian of Indian descent | 3 (75.0) | 1 (25.0) | ||

| Residence | ||||

| Urban | 15 (79.0) | 4 (21.0) | −1.1 (−27.7 to 25.3) | 0.62 |

| Rural | 14 (77.8) | 4 (22.2) | ||

| Age at screening (years) | ||||

| <10 | 13 (76.5) | 4 (23.5) | 3.5 (−23.2 to 30.2) | 0.55 |

| ≥10 | 16 (80.0) | 4 (20.0) | ||

| Length of follow-up (years) | ||||

| ≥5 | 12 (63.3) | 7 (36.8) | 31.3 (7.2 to 55.4) | 0.03 |

| <5 | 17 (94.4) | 1 (5.6) | ||

| Adherence to antibiotic prophylaxis (%) | ||||

| ≥50 | 24 (77.4) | 7 (22.6) | 5.9 (−27.3 to 39.2) | 0.61 |

| <50 | 5 (83.3) | 1 (16.7) | ||

| Echocardiographic | ||||

| Baseline diagnosis | ||||

| Definite | 14 (70.0) | 6 (30.0) | 18.2 (−7.0 to 43.5) | 0.17 |

| Borderline | 15 (88.2) | 2 (11.8) | ||

| Severity at baseline | ||||

| Moderate/severe | 10 (83.3) | 2 (16.7) | −7.3 (−34.2 to 19.6) | 0.48 |

| Borderline/mild | 19 (76.0) | 6 (24.0) | ||

| MR >2 cm | ||||

| Yes | 23 (79.3) | 6 (20.7) | −4.3 (−37.7 to 29.1) | 0.57 |

| No | 6 (75.0) | 2 (25.0) | ||

| Initial MR length | ||||

| Mean, cm (SD) | 2.61 (1.4) | 2.45 (1.7) | n/a | 0.68 |

| AR >1 cm | ||||

| Yes | 10 (66.7) | 5 (33.3) | 19.6 (−8.1 to 47.5) | 0.15 |

| No | 19 (86.4) | 3 (13.6) | ||

| Morphological changes | ||||

| ≥1 | 19 (76.0) | 6 (24.0) | 7.3 (−19.6 to 34.3) | 0.48 |

| None | 10 (83.3) | 2 (16.7) | ||

AR, aortic regurgitation; MR, mitral regurgitation; RHD, rheumatic heart disease.

Discussion

This study represents the longest follow-up of participants with echocardiographic screening-detected RHD. Definite RHD appears to be a true disease entity with 70% of cases persisting or progressing and 20% requiring cardiac surgery during median follow-up of 7.5 years. Borderline RHD is a more heterogeneous group, with 24% developing moderate or severe, definite RHD and 12% normalising over the study period. The results of our study are likely to approximate the natural history of echocardiographic findings because the use of antibiotic prophylaxis was very low across the cohort.

Our findings are strikingly similar to those of Zühlke et al,12 who reviewed 55 cases after a median of 60 months in South Africa, using WHF criteria. Of 10 definite RHD cases, 2 improved to borderline RHD and 1 to normal. Of 34 borderline RHD cases, 20% progressed to definite RHD and 59% were classified as normal. Many of the normal cases were adults classified using WHF definitions for individuals aged >20 years, which do not include the borderline category, and therefore the proportion with objective improvements in echocardiography may have been lower. Other studies using the WHF criteria, with shorter follow-up periods, have shown progression of borderline RHD cases in 16%–42%.11 13 26 Earlier follow-up studies used non-standardised criteria, and although not directly comparable, reported similar findings.27–29

More than half of baseline echocardiograms were reclassified as normal, reflecting the higher specificity of the WHF criteria compared with earlier NIH-WHO criteria.14 Four cases with a normal baseline echocardiogram were diagnosed with borderline RHD at follow-up, but none developed definite RHD. These cases had been flagged as abnormal using older criteria or by other reporters, and are therefore not representative of all screen-negative cases. Other studies have shown that 1%–2% of cases with normal screening echocardiograms may develop definite RHD.13 26 This likely reflects the cumulative risk of developing RHD in a high-prevalence setting, and demonstrates that screening at a single age point in childhood will miss a proportion of cases that develop RHD in adolescence and early adulthood. No child with NSVAs at baseline progressed to definite RHD, supporting the WHF classification that these findings represent the upper limits of normal echocardiography and do not require further treatment or follow-up.

Follow-up of >5 years was the only factor we found to be associated with improvement in echocardiographic diagnosis. This likely represents the cumulative resolution of milder forms of disease in a proportion of patients each year, and is consistent with the known course of clinical RHD.30 Other studies have shown an association between persistence of RHD and pathological MR at baseline12 and bedroom crowding.26 Interpretation of all follow-up studies to date is limited by small sample sizes.

The notable difference of our results, compared with previous publications, relates to the severity of disease. Our cohort included many cases with moderate to severe disease at baseline, including four patients requiring valve surgery and three who died during the follow-up period (two due to severe RHD). These patients would presumably have had clinical symptoms or signs at the time of screening, but had not yet been diagnosed due to broader access, health seeking and health system issues. By contrast, <1% of a cohort in New Caledonia developed cardiac complications.26 Further studies into the clinical outcomes of screening-detected RHD, in a range of settings, are required.

For screening-detected cases of definite RHD, our data strongly support the recommendations of the WHF guidelines: the initiation of secondary prophylaxis with ongoing promotion of adherence.7 Further, our data suggest that borderline RHD is not a benign entity. Progression to definite RHD in approximately a quarter demonstrates that borderline cases need clinical follow-up at a minimum. All four borderline RHD cases that progressed to moderate–severe, definite RHD had pathological regurgitation without the morphological features required to fulfil a diagnostic of definite RHD at baseline. The diagnosis for one participant changed from borderline to severe, definite RHD due to the development of a single morphological feature. Assessment of morphology remains subjective, and agreement between experienced cardiologists on the presence of these features is lower than that for regurgitation or overall diagnosis.31 Clinicians should be made aware of this potential limitation of using the WHF criteria to devise individual management plans.

We do not recommend prophylaxis for all borderline cases, but propose that the severity of regurgitation should be used to stratify risk and influence individual management decisions, and expect that experienced clinicians would already consider this as part of standard clinical practice. Our practice is to recommend prophylaxis for patients with borderline RHD who have moderate to severe regurgitation on echocardiography, or with any clinical signs of RHD, as part of counselling families about the prevention of rheumatic fever. Further discrimination of the borderline group into those at true risk from the normal population may not be possible without the development of a non-echocardiographic diagnostic test for RHD. Although a longitudinal, multicountry register has been initiated to further assess the history of mild and borderline RHD diagnosed on screening,32 further clarity on this issue may not be achieved for several years. Therefore, programmes and clinicians will need to balance the potential, yet unproven, benefits of prophylaxis with the burden of overtreatment to individuals and the health system. At a minimum, the development of health system structures for regular, active surveillance of subclinical cases is needed. Implementation of effective recall and follow-up systems is likely to be challenging in many resource-limited and remote settings, and this should be a fundamental consideration for countries deciding whether or not to implement screening. Finally, population-based screening should not be implemented without an ongoing commitment to improve the delivery of secondary prophylaxis. The very low adherence found in this cohort reflects the multifaceted improvements required in Fiji, which are currently being addressed.33

The main limitation of this study was the available sample size, which limited the power to evaluate associations with disease progression. We were also unable to follow-up cases with negative screening echocardiography. Although modifications to the WHF criteria were used, this did not appear to affect the study findings. A single participant with borderline disease would have been classified as normal using the WHF definitions for individuals aged >20 years (table 4), and still classified as improved (from definite RHD at baseline). Agreement between the reporting cardiologist was moderate, similar to reported in other studies.9 13 Since the diagnosis of the same reporter on both echocardiograms was used for analysis, the use of a single reporter is unlikely to have affected the results.

Conclusions

The echocardiographic outcomes for young people with screening-detected, definite RHD are variable. While the majority remain stable, some develop severe clinical complications and others improve without treatment. Borderline RHD is not a benign entity, and although factors associated with progression remain unclear, risk stratification may be used to guide individual treatment plans. Until results of large registries or clinical trials become available, a cautious approach to management and prophylaxis is required, with an emphasis on developing strong systems for follow-up of individuals with abnormal screening.

Key messages.

What is already known about this subject?

Echocardiography can accurately detect rheumatic heart disease (RHD) in those without a history of rheumatic fever. Follow-up of small numbers of children with screening-detected RHD for 2–5 years has shown variable progression, with most cases of definite RHD persisting and 16%–59% of borderline RHD cases improving.

What does this study add?

This study supports previous findings that most definite and borderline RHD cases persist over time (65%–70% in this cohort). In contrast to previous studies, this study shows that screening-detected, definite RHD may be very severe, requiring valve surgery or causing premature death. Borderline RHD is a heterogeneous group, but should not be considered benign, as a quarter of borderline cases developed moderate–severe, definite RHD based on the morphological appearance of the valve.

How might this impact on clinical practice?

Our study supports the treatment of screening-detected, definite RHD with secondary antibiotic prophylaxis. Further, we propose treatment of borderline cases with moderate–severe regurgitation. If population-based screening is to be implemented, development of strong health system structures to follow-up screening-detected cases is essential.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Fiji Ministry of Health and Medical Services and health clinic staff for their support. The authors also thank the research staff Maureen Ah Kee, Maciu Silai, Frances Matanatabu, Lai Matatolu and Sera Rayasidamu for their contributions. The authors also thank Ranu Anjali and Dipesh Raniga for assistance with clinical assessment of participants and Jonathan Carapetis, Terry Nolan, Jim Tulloch and Susan Donath for providing valuable advice on study design and interpretation.

Footnotes

Contributors: DE and ACS conceived the study and devised the protocol with input from GRW, JHK, BR, RLM and SMC. GRW and BR evaluated the echocardiograms. DE coordinated the data collection, performed the analysis and was the main author of the manuscript. All authors provided critical feedback on the manuscript, and read and approved the final version.

Funding: This project was supported by Cure Kids New Zealand. DE, SMC and ACS are supported by Australian National Health and Medical Research Council research fellowships. DE and ACS are supported by the National Heart Foundation of Australia. DE is supported by the University of Melbourne Nossal Global Scholars program.

Competing interests: None.

Ethics approval: Fiji National Research Ethics Review Committee (2015.17) and the Human Research Ethics Committee of the Royal Children's Hospital, Australia (35059A).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Lozano R, Naghavi M, Foreman K et al. . Global and regional mortality from 235 causes of death for 20 age groups in 1990 and 2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet 2012;380:2095–128. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61728-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Okello E, Wanzhu Z, Musoke C et al. . Cardiovascular complications in newly diagnosed rheumatic heart disease patients at Mulago Hospital, Uganda. Cardiovasc J Afr 2013;24:80–5. doi:10.5830/CVJA-2013-004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sliwa K, Carrington M, Mayosi BM et al. . Incidence and characteristics of newly diagnosed rheumatic heart disease in urban African adults: insights from the heart of Soweto study. Eur Heart J 2010;31:719–27. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehp530 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zühlke LJ, Engel ME, Watkins D et al. . Incidence, prevalence and outcome of rheumatic heart disease in South Africa: a systematic review of contemporary studies. Int J Cardiol 2015;199:375–83. doi:10.1016/j.ijcard.2015.06.145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Marijon E, Ou P, Celermajer DS et al. . Prevalence of rheumatic heart disease detected by echocardiographic screening. N Engl J Med 2007;357:470–6. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa065085 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Commonwealth of Australia. Population Based Screening Framework 2008. http://www.cancerscreening.gov.au/internet/screening/publishing.nsf/content/population-based-screening-framework (accessed 15 August 2016).

- 7.Reményi B, Wilson N, Steer A et al. . World Heart Federation criteria for echocardiographic diagnosis of rheumatic heart disease—an evidence-based guideline. Nat Rev Cardiol 2012;9:297–309. doi:10.1038/nrcardio.2012.7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Clark BC, Krishnan A, McCarter R et al. . Using a low-risk population to estimate the specificity of the world heart federation criteria for the diagnosis of rheumatic heart disease. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 2016;29:253–8. doi:10.1016/j.echo.2015.11.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Roberts K, Maguire G, Brown A et al. . Echocardiographic screening for rheumatic heart disease in high and low risk Australian children. Circulation 2014;129:1953–61. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.003495 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Roberts K, Colquhoun S, Steer A et al. . Screening for rheumatic heart disease: current approaches and controversies. Nat Rev Cardiol 2013;10:49–58. doi:10.1038/nrcardio.2012.157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Beaton A, Okello E, Aliku T et al. . Latent rheumatic heart disease: outcomes 2 years after echocardiographic detection. Pediatr Cardiol 2014;35:1259–67. doi:10.1007/s00246-014-0925-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zühlke L, Engel ME, Lemmer CE et al. . The natural history of latent rheumatic heart disease in a 5 year follow-up study: a prospective observational study. BMC Cardiovasc Disord 2016;16:46 doi:10.1186/s12872-016-0225-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rémond M, Atkinson D, White A et al. . Are minor echocardiographic changes associated with an increased risk of acute rheumatic fever or progression to rheumatic heart disease? Int J Cardiol 2015;198:117–22. doi:10.1016/j.ijcard.2015.07.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Colquhoun SM, Kado JH, Remenyi B et al. . Echocardiographic screening in a resource poor setting: borderline rheumatic heart disease could be a normal variant. Int J Cardiol 2014;173:284–9. doi:10.1016/j.ijcard.2014.03.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Engelman D, Kado JH, Reményi B et al. . Focused cardiac ultrasound screening for rheumatic heart disease by briefly trained health workers: a study of diagnostic accuracy. Lancet Glob Health 2016;4:e386–94. doi:10.1016/S2214-109X(16)30065-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Parks T, Kado J, Miller AE et al. . Rheumatic heart disease-attributable mortality at ages 5–69 years in Fiji: A Five-Year, National, Population-Based Record-Linkage Cohort Study. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 2015;9:e0004033 doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0004033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Thomson Mangnall L, Sibbritt D, Fry M et al. . Short- and long-term outcomes after valve replacement surgery for rheumatic heart disease in the South Pacific, conducted by a fly-in/fly-out humanitarian surgical team: a 20-year retrospective study for the years 1991 to 2011. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2014;148:1996–2003. doi:10.1016/j.jtcvs.2014.02.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Carapetis JR, Paar J, Cherian T. Standardization of epidemiologic protocols for surveillance of post-streptococcal sequelae: acute rheumatic fever, rheumatic heart disease and acute post-streptococcal glomerulonephritis. National Institutes of Health, 2006. (cited 30 May 2014). http://www.niaid.nih.gov/topics/strepthroat/documents/groupasequelae.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 19.Steer AC, Kado J, Wilson N et al. . High prevalence of rheumatic heart disease by clinical and echocardiographic screening among children in Fiji. J Heart Valve Dis 2009;18:327–35; discussion 336. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Engelman D, Kado JH, Reményi B et al. . Screening for rheumatic heart disease: quality and agreement of focused cardiac ultrasound by briefly trained health workers. BMC Cardiovasc Disord 2016;16:30 doi:10.1186/s12872-016-0205-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Engelman D, Mataika RL, Kado JH et al. . Adherence to secondary antibiotic prophylaxis for patients with rheumatic heart disease diagnosed through screening in Fiji. Trop Med Int Health Published Online First: 12 Oct 2016. doi:10.1111/tmi.12796 doi:10.1111/tmi.12796 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Beaton A, Aliku T, Okello E et al. . The utility of handheld echocardiography for early diagnosis of rheumatic heart disease. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 2014; 27:42–9. doi:10.1016/j.echo.2013.09.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lancellotti P, Tribouilloy C, Hagendorff A et al. . European Association of Echocardiography recommendations for the assessment of valvular regurgitation. Part 1: aortic and pulmonary regurgitation (native valve disease). Eur J Echocardiogr 2010;11:223–44. doi:10.1093/ejechocard/jeq030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lancellotti P, Moura L, Pierard LA et al. . European Association of Echocardiography recommendations for the assessment of valvular regurgitation. Part 2: mitral and tricuspid regurgitation (native valve disease). Eur J Echocardiogr 2010;11: 307–32. doi:10.1093/ejechocard/jeq031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Baumgartner H, Hung J, Bermejo J et al. . Echocardiographic assessment of valve stenosis: EAE/ASE recommendations for clinical practice. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 2009;22:1–23. doi:10.1016/j.echo.2008.11.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mirabel M, Fauchier T, Bacquelin R et al. . Echocardiography screening to detect rheumatic heart disease: a cohort study of schoolchildren in French Pacific Islands. Int J Cardiol 2015;188:89–95. doi:10.1016/j.ijcard.2015.04.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Paar JA, Berrios NM, Rose JD et al. . Prevalence of rheumatic heart disease in children and young adults in Nicaragua. Am J Cardiol 2010;105:1809–14. doi:10.1016/j.amjcard.2010.01.364 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bhaya M, Beniwal R, Panwar S et al. . Two years of follow-up validates the echocardiographic criteria for the diagnosis and screening of rheumatic heart disease in asymptomatic populations. Echocardiography 2011;28:929–33. doi:10.1111/j.1540-8175.2011.01487.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Saxena A, Ramakrishnan S, Roy A et al. . Prevalence and outcome of subclinical rheumatic heart disease in India: the RHEUMATIC (Rheumatic Heart Echo Utilisation and Monitoring Actuarial Trends in Indian Children) study. Heart 2011;97:2018–22. doi:10.1136/heartjnl-2011-300792 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bland EF, Duckett Jones T. Rheumatic fever and rheumatic heart disease; a twenty year report on 1000 patients followed since childhood. Circulation 1951;4:836–43. doi:10.1161/01.CIR.4.6.836 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bacquelin R, Tafflet M, Rouchon B et al. . Echocardiography-based screening for rheumatic heart disease: what does borderline mean? Int J Cardiol 2016;203:1003–4. doi:10.1016/j.ijcard.2015.11.110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Saxena A, Zühlke L, Wilson N. Echocardiographic screening for rheumatic heart disease: issues for the cardiology community. Glob Heart 2013;8:197 doi:10.1016/j.gheart.2013.08.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.The Fijian Government. Health Ministry committed to addressing rheumatic heart disease Fiji: Fiji Government Online Portal, 2015. (updated 8 April 2015; cited 23 May 2016). http://www.fiji.gov.fj/media-center/press-releases/health-ministry-committed-to-addressing-rheumatic-.aspx