Abstract

Instruction

There is evidence of a relationship between severity of infection and inflammatory response of the immune system. The objective is to assess serum levels of immunoglobulins and to establish its relationship with severity of community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) and clinical outcome.

Methods

This was an observational and cross-sectional study in which 3 groups of patients diagnosed with CAP were compared: patients treated in the outpatient setting (n=54), patients requiring in-patient care (hospital ward) (n=173), and patients requiring admission to the intensive care unit (ICU) (n=191).

Results

Serum total IgG (and IgG subclasses IgG1, IgG2, IgG3, IgG4), IgA and IgM were measured at the first clinical visit. Normal cutpoints were defined as the lowest value obtained in controls (≤680, ≤323, ≤154, ≤10, ≤5, ≤30 and ≤50 mg/dL for total IgG, IgG1, IgG2, IgG3, IgG4, IgM and IgA, respectively). Serum immunoglobulin levels decreased in relation to severity of CAP. Low serum levels of total IgG, IgG1 and IgG2 showed a relationship with ICU admission. Low serum level of total IgG was independently associated with ICU admission (OR=2.45, 95% CI 1.4 to 4.2, p=0.002), adjusted by the CURB-65 severity score and comorbidities (chronic respiratory and heart diseases). Low levels of total IgG, IgG1 and IgG2 were significantly associated with 30-day mortality.

Conclusions

Patients with severe CAP admitted to the ICU showed lower levels of immunoglobulins than non-ICU patients and this increased mortality.

Keywords: Immunodeficiency, Pneumonia, Respiratory Infection

Key messages.

Low levels of immunoglobulins are a prognostic factor of severity in community pneumonia?

Patients with severe community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU) showed lower levels of circulating immunoglobulins than non-ICU patients and this observation is associated with an increased mortality.

These findings suggest that we should continue the investigation of the target subgroup of patients with CAP where the use of intravenous immunoglobulin as adjunctive treatment may improve outcome and reduce mortality.

Introduction

Community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) remains one of the infectious diseases with the highest morbidity and mortality. In the general adult population, the annual incidence of CAP varies between 1.6 and 13.4 cases per 1000 inhabitants, and hospitalisation rates range between 22% and 61.4%.1 2 Approximately 10% of hospitalised patients require admission to the intensive care unit (ICU).3 The mortality rate varies between 0.1 and 0.7 per 1000 persons-year.1–5

There is evidence of the relationship between severity of infection and inflammatory response of the immune system.6 7 Immunoglobulins (IgG subclasses) are particularly effective in the identification, neutralisation, opsonisation and direct lysis of pathogens as well as activation of the complement cascade. Owing to these specific functions, immunoglobulins are postulated as new therapies, already used in the treatment of primary humoral immunodeficiency,8–11 autoimmune diseases11 and neonatal streptococcal septic shock.12 Treatment with intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG) is a promising adjunctive therapy for severe sepsis and septic shock, but its use remains controversial, although an overall mortality benefit has been reported in small studies.13

It is well known that a deficit in immunoglobulin production, especially IgG in primary immunodeficiencies, causes an increase in infections, in particular by encapsulated pathogens of the upper (sinusitis, tracheobronchitis) or lower (pneumonia) respiratory tract. However, there is little information on changes in serum levels of immunoglobulins in previously healthy subjects diagnosed with pneumonia. Therefore, a cross-sectional study in patients with CAP was conducted, the aim of which was to assess serum levels of immunoglobulins and to establish a relationship with severity of pneumonia and clinical outcome.

Methods

Design and setting

This was an observational and cross-sectional study in which three groups of patients diagnosed with CAP were compared. The diagnosis of CAP was based on acute lower respiratory tract infection with the appearance of focal signs on physical examination of the chest and new radiological findings suggestive of pulmonary infiltrate.1 2 The three study populations were patients with CAP treated at home, patients with CAP requiring inpatient care, and patients with CAP requiring admission to the ICU.14 All patients gave written consent to draw blood samples for the immunological study on the first day of the patient–physician encounter. Written informed consent was obtained directly from all patients or their legal representative before enrolment. The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Consorci Sanitari del Maresme (Barcelona, Spain).

Exclusion criteria and other study details, including data collected for each patient, are described in the online supplementary data.

bmjresp-2016-000152supp.pdf (77.2KB, pdf)

Prognostic data included were septic shock, defined by persistent hypotension despite fluid replacement therapy associated with signs of hypoperfusion, and 30-day mortality. Severity of CAP at the first evaluation of the patient was estimated using the CURB-65 severity score.15

Immunological study

Blood samples were obtained from all patients during the first contact with the physician and at the time of diagnosis of CAP, and were stored at −80°C until analysis. Serum total IgG (and IgG subclasses IgG1, IgG2, IgG3, IgG4), IgA and IgM were measured by nephelometry.16 Since standard criteria regarding normal values of immunoglobulins are lacking, reference values were those obtained in a control group of the same population (see online supplementary data).17 In patients with CAP, normal cutpoints for serum concentration of immunoglobulins or IgG subclasses was defined as the lowest value obtained in controls, which were 680 mg/dL for IgG, 323 mg/dL for IgG1, 154 mg/dL for IgG2, 10 mg/dL for IgG3, 5 mg/dL for IgG4, 30 mg/dL for IgM, and 50 mg/dL for IgA. Hypogammaglobulinaemia was defined as a serum IgG level <500 mg/dL.18

Statistical analysis

Immunoglobulin levels in each of the three study groups (ambulatory CAP, hospitalised patients with CAP, patients with CAP admitted to the ICU) were expressed as median and IQR (25–75th centile) and also categorised as low (deficient) or normal levels according to the cutpoints for serum levels of immunoglobulins and IgG subclasses. Ambulatory patients with CAP or those requiring inpatient care were grouped in a single category of non-ICU patients with CAP in order to compare this category with patients with CAP admitted to the ICU. All factors associated with low serum levels of immunoglobulins were analysed. Means were compared with the analysis of variance (ANOVA) or the Kruskal-Wallis test (three groups) or Student's t-test or the Mann-Whitney U test (two groups). The Spearman correlation coefficient (rs) was used to assess the relationship between continuous variables. The effect of serum levels of immunoglobulins on ICU admission was assessed in a logistic regression analysis, and the OR and 95% CIs were calculated. The model was adjusted by confounding variables associated with both serum levels of immunoglobulins and ICU admission. Statistical significance was set at p<0.05. The SPSS program (V.11.0) was used for data analysis.

Results

Study population and baseline characteristics

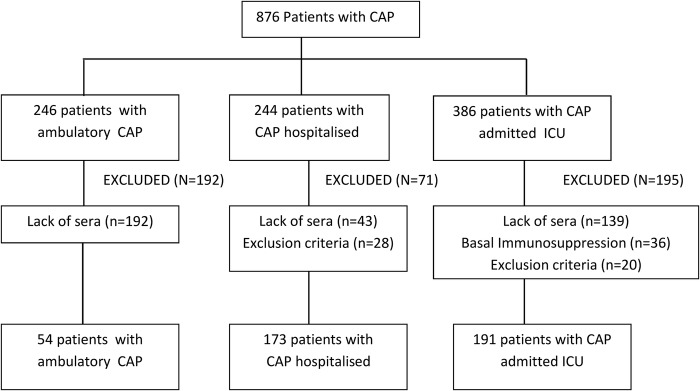

A total of 876 patients diagnosed with CAP were enrolled and classified into groups of ambulatory CAP (n=246), CAP requiring hospitalisation (n=244), and CAP requiring care in the ICU (n=386). However, 458 (52.3%) patients were excluded in most cases (n=374) because blood samples on the day of CAP diagnosis were unavailable. The flow chart of the study population is shown in figure 1. The three study groups included 54 patients with CAP treated in the outpatient setting, 173 admitted to the hospital, and 191 admitted to the ICU. Baseline characteristics of the patients are shown in table 1.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of the study population. CAP, community-acquired pneumonia; ICU, intensive care unit.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the study population according to site of care

| Site of care of patients with CAP |

p Value three study groups | p Value ICU vs non-ICU groups | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Ambulatory | Hospital ward | ICU | Non-ICU | ||

| Total patients | 54 | 173 | 191 | 227 | ||

| Male patients | 42 (77.8) | 112 (64.7) | 136 (71.2) | 154 (67.8) | 0.146 | 0.457 |

| Age, years, mean (SD) | 51.1 (18.8) | 71.1 (15.6) | 60.1 (17.4) | 66.3 (18.5) | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Alcohol consumption | 7 (14) | 8 (4.8) | 30 (15.7) | 15 (6.9) | 0.003 | 0.004 |

| Smoking habit | 14 (28) | 27 (16.1) | 67 (35.1) | 41 (18.8) | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Chronic respiratory disease | 12 (24) | 100 (59.2) | 73 (38.2) | 112 (51.1) | <0.001 | 0.009 |

| Chronic heart disease | 6 (12) | 76 (45) | 42 (22) | 82 (37.4) | <0.001 | 0.001 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 2 (4) | 41 (24.3) | 44 (23) | 43 (19.6) | 0.006 | 0.401 |

| Chronic neurological disorders | 5 (10) | 29 (17.2) | 19 (9.9) | 34 (15.5) | 0.101 | 0.093 |

| Chronic renal failure | 1 (2) | 8 (4.7) | 7 (3.7) | 9 (4.1) | 0.663 | 0.817 |

| Past solid neoplasm | 1 (2) | 10 (5.9) | 4 (2.1) | 11 (5.0) | 0.125 | 0.115 |

| Oral corticosteroids | 5 (10) | 30 (17.8) | 8 (4.2) | 35 (16.0) | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Previous symptoms, days, mean (SD) | 7.6 (5.6) | 4.5 (5.3) | 3.5 (2.9) | 5 (5.5) | <0.001 | 0.069 |

| Shock | 0 | 0 | 88 (46.1) | 0 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Death | 0 | 5 (2.9) | 43 (22.5) | 5 (2.2) | <0.001 | <0.001 |

Data as frequencies and percentages in parentheses unless otherwise stated.

CAP, community-acquired pneumonia; ICU, intensive care unit.

Serum immunoglobulin levels

As shown in table 2, serum immunoglobulin levels decreased in relation to severity of CAP, that is, patients requiring ICU admission showed significantly lower values of all IgG subclasses and IgA as compared with patients with CAP treated in the outpatient setting or admitted to the hospital. Serum immunoglobulins except for total IgG were higher in ambulatory CAP as compared with hospitalised patients, who also showed higher levels as compared with patients admitted to the ICU.

Table 2.

Differences of serum levels of immunoglobulins in patients with CAP according to the site of care on the first day of medical consultation

| Serum levels of immunoglobulins (mg/dL) | Site of care of patients with CAP |

p Value three study groups | p Value ICU vs non-ICU groups | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ambulatory (n=54) | Hospital ward (n=173) | ICU (n=191) | Non-ICU (n=227) | |||

| IgG, total | 1110 (889–1350) | 986.5 (768.5–1175) | 908 (682–1300) | 1010 (810–1210) | 0.035 | 0.081 |

| IgG1 | 673 (557–815) | 608.5 (493.5–767.5) | 541 (401–766) | 623 (504–772) | 0.009 | 0.005 |

| IgG2 | 339 (239–506) | 318 (209–430.5) | 270.5 (162–369) | 323.5 (221–447) | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| IgG3 | 60.8 (43.1–80) | 61.3 (43.5–85.4) | 43.1 (29–70) | 61.3 (43.4–83.3) | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| IgG4 | 46.8 (27.7–103) | 43.3 (18.6–74.5) | 28.5 (15–58) | 44.7 (21.4–80.9) | 0.001 | 0.001 |

| IgA | 233 (160–342) | 254 (186–333) | 221.5 (132–310) | 249 (184–340) | 0.018 | 0.008 |

| IgM | 107 (58–162) | 76.5 (53–121) | 83 (58–117) | 81 (54–129) | 0.032 | 0.705 |

Data as median and IQR (25–75th centile) in parentheses.

CAP, community-acquired pneumonia; ICU, intensive care unit.

The correlation between serum immunoglobulin levels and days with symptoms prior to medical diagnosis of CAP showed a significant and positive correlation between IgG2 levels and days with symptoms in patients not requiring ICU admission (rs=0.145, p=0.035), whereas in patients admitted to the ICU there was a negative correlation between days of previous symptoms and serum levels of total IgG (rs=−0.216, p=0.003), IgG1 (rs=0.201, p=0.005) and IgG2 (rs=−0.175, p=0.016).

Low serum immunoglobulin levels

As shown in table 3, low serum levels of total IgG, IgG1 and IgG2 (according to the reference values) showed a relationship with ICU admission. Differences in the percentage of patients with low immunoglobulin levels between those treated in the outpatient setting and those admitted to the hospital ward were not observed. However, there was a statistically significant association between low levels of total IgG and IgG1 and higher values in the CURB-65 severity score (table 4). All patients with a CURB-65 severity score of 4 and 5 were admitted to the ICU.

Table 3.

Patients with CAP and low levels of serum immunoglobulins according to the site of care

| Low levels of serum immunoglobulins, mg/dL (cutpoints) | Site of care of patients with CAP |

p Value three study groups | p Value ICU vs non-ICU groups | OR (95% CI) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ambulatory (n=54) | Hospital ward (n=173) | ICU (n=191) | Non-ICU (n=227) | ||||

| IgG, total (≤680) | 7 (13) | 33 (19.1) | 75 (39.3) | 40 (17.6) | <0.001 | <0.001 | 3.03 (1.94 to 4.75) |

| IgG1 (≤323) | 3 (5.6) | 13 (7.5) | 41 (21.5) | 16 (7.1) | <0.001 | <0.001 | 3.59 (1.94 to 6.63) |

| IgG2 (≤154) | 8 (14.8) | 31 (17.9) | 52 (27.2) | 39 (17.2) | <0.04 | <0.013 | 1.8 (1.13 to 2.89) |

| IgG3 (≤10) | 1 (1.9) | 0 | 5 (2.6) | 1 (0.4) | 0.108 | 0.098 | 6.05 (0.7 to 52.2) |

| IgG4 (≤5) | 3 (5.6) | 7 (4.0) | 5 (2.6) | 10 (4.4) | 0.544 | 0.328 | 0.58 (0.2 to 1.74) |

| IgA (≤50) | 1 (2.0) | 4 (2.3) | 7 (3.7) | 5 (2.2) | 0.683 | 0.389 | 1.60 (0.81 to 3.17) |

| IgM (≤30) | 3 (5.6) | 13 (7.5) | 21 (11.0) | 16 (7.1) | 0.366 | 0.173 | 1.66 (0.52 to 5.32) |

Data as frequencies and percentages in parentheses.

CAP, community-acquired pneumonia; ICU, intensive care unit.

Table 4.

Association between low serum levels of immunoglobulins and CURB-65 score

| Immunoglobulins cutpoints, mg/dL | CURB-65 severity score |

p Value | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 (n=71) | 1 (n=137) | 2 (n=124) | 3 (n=68) | 4 (n=14) | 5 (n=4) | ||

| IgG, total (≤680) | 14 (19.7) | 29 (21.2) | 36 (29.0) | 28 (41.2) | 5 (35.7) | 3 (75) | 0.005 |

| IgG1 (≤323) | 6 (8.5) | 11 (8) | 17 (13.7) | 18 (26.5) | 3 (21.4) | 2 (50) | 0.001 |

| IgG2 (≤154) | 11 (15.5) | 30 (21.9) | 22 (17.7) | 23 (33.8) | 4 (28.6) | 1 (25) | 0.113 |

| IgG3 (≤10) | 1 (1.4) | 2 (1.5) | 2 (1.6) | 1 (1.5) | 0 | 0 | 0.998 |

| IgG4 (≤5) | 5 (7) | 2 (1.5) | 6 (4.8) | 2 (3) | 0 | 0 | 0.353 |

| IgA (≤50) | 2 (2.8) | 4 (2.9) | 2 (1.6) | 3 (4.4) | 1 (7.1) | 0 | 0.820 |

| IgM (≤30) | 4 (5.6) | 9 (6.6) | 12 (9.7) | 10 (14.7) | 2 (14.3) | 0 | 0.331 |

Data as frequencies and percentages in parentheses.

In the multivariate analysis, a low serum level of total IgG was independently associated with ICU admission (OR=2.45, 95% CI 1.4 to 4.2, p=0.002), adjusted by the CURB-65 severity score and comorbidities (chronic respiratory and heart diseases) (table 5).

Table 5.

Effect of low levels of serum IgG levels adjusted by independent risk factors on ICU admission

| Variable | OR (95% CI) | p Value |

|---|---|---|

| Low level of total IgG (≤680 mg/dL) | 2.45 (1.4 to 4.2) | 0.002 |

| CURB-65 severity score | 4.62 (3.33 to 6.4) | <0.001 |

| Chronic heart disease | 0.22 (0.12 to 0.4) | <0.001 |

| Chronic respiratory disease | 0.29 (0.17 to 0.51) | <0.001 |

ICU, intensive care unit.

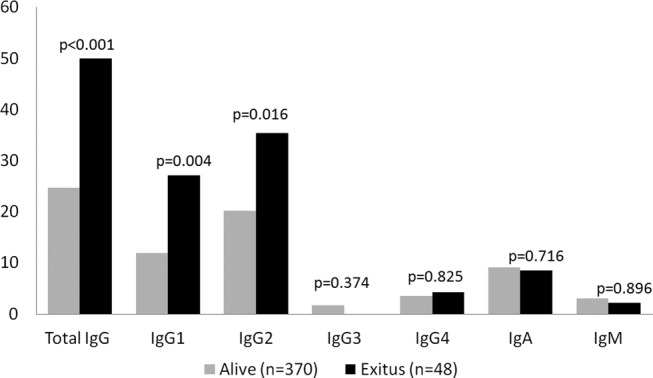

30-day mortality

Of the 418 patients with CAP, 48 (11.5%) died within 30 days after diagnosis. In relation to the CURB-65 severity score, the mortality rate was 100% for patients with score 5, 28.6% for score 4, 20.6% for score 3, 18.7% for score 2 and only 2.2% for score 1. Admissions to the hospital and to the ICU were both associated with mortality. Also, low levels of total IgG, IgG1 and IgG2 were significantly related to fatality (figure 2). Patients with hypogammaglobulinaemia (total IgG<500 mg/dL) (n=23) also showed a higher mortality rate than the remaining patient, but it was not statistically significant (p=0.079).

Figure 2.

Low levels of serum immunoglobulins and effect on 30-day mortality.

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study in which serum levels of immunoglobulins were measured in patients with CAP divided according to severity of pneumonia. We have observed that if the CAP is more severe, there is a lower concentration of IgG1, IgG2, IgG3 and IgG4 subclasses as well as IgA. In fact, patients requiring ICU admission as compared with those not treated in the ICU showed lower levels of circulating IgG1, IgG2, IgG3, IgG4 and IgA. Since no differences in serum concentrations of immunoglobulins between patients treated ambulatorily and patients treated in the hospital ward were observed, it seems that low immunoglobulin levels may occur exclusively in patients with severe CAP, and that low values of total IgG in the acute phase of CAP is an independent prognostic factor for ICU admission.

Although factors influencing the outcome of pneumonia have been extensively investigated, the potential effect of low immunoglobulin levels on mortality in CAP remains unclear. Moreover, it has been observed that low levels of total IgG, IgG1 and IgG2 at the onset of CAP are indicator of a higher severity and an increased in mortality.

A few studies have assessed changes of serum immunoglobulin levels in pneumonia. Feldman et al19 measured IgG levels in 66 patients (19 patients required ICU treatment), and found abnormal levels (increase or decrease) in the IgG subclasses but without differences between ICU and non-ICU patients. These findings may be probably be explained by the small number of patients in both groups, particularly critically ill patients. In the present study, serum immunoglobulin levels were measured in a large study sample of 418 patients with CAP, which allowed stratification into two large subsets of 227 patients not requiring ICU admission and 191 severely ill patients treated in the ICU. We found significant differences in the four IgG subclasses, with lower values among patients admitted to the ICU. In contrast to findings in the study of Feldman et al,19 we found that low levels of total IgG, IgG1 and IgG2 may be prognostic factors of mortality and are more frequently observed in patients admitted to the ICU. In 1990, Herer et al20 reported that serum levels of IgG2 in patients with CAP (n=38) of bacterial or unknown aetiology were lower than in healthy subjects (n=26), remaining low 9 months later. A comparison with healthy subjects was not made in our study. However, in a previous population-based case–control study, with 171 cases and 90 controls matched by age and sex, all immunoglobulins were significantly lower in cases than in controls, mainly total IgG and IgG2.17 In contrast to the study of Herer et al,20 80% of patients normalised immunological levels in the convalescent phase (after 30 days).

Similar results have been obtained in the studies of Gordon et al21 22 in which a decrease in serum levels of total IgG, IgG1 and IgG2 in patients with CAP with severe influenza H1N1 virus pneumonia as well in the remaining patients with severe non-influenza CAP. Although Gordon et al11 21 established an association between acute low values of IgG2 and severe infection by influenza H1N1 virus, they could not determine whether this was due to the virus itself or to other factors of severity. On the other hand, Justel et al23 observed that patients with severe disease caused by influenza A (H1N1) and low levels of IgG2 and IgM on ICU admission died sooner. In our study, we detected no differences in serum levels of IgM, perhaps because we excluded immunosuppressed patients. In this study, low levels of total IgG (below the reference cut-off value) was an independent risk factor for ICU admission in the logistic regression analysis, as was the CURB-65 severity score.

Clearly, there are levels of serum immunoglobulins lower in patients with severe CAP, but the reason for these decline is unknown. Hukuhara et al24 suggested that IgG2 are consumed at the infected phase by protecting against bacterial infections. In our study, ICU patients despite consult a physicians before patients no-ICU, showed lower IgG2 and also to further delay in diagnosis more decreased concentrations of this subclass. Regardless of the underlying mechanism responsible for the low levels of immunoglobulins, according to the present findings, patients with decreases in total IgG and IgG1, as well as IgG2, have a threefold and twofold increased risk of ICU admission, respectively, than patients with normal levels. Low levels of total IgG were found in 20.9% of patients who died as compared with 8% of survivors. In previous study in our group, showed as serum levels of IgG2 (<301 mg/dL) at the time of CAP diagnosis was a mortality predictor for hospitalised patients with CAP and patients with IgG2 levels below this cut-off died sooner.25 Of studies that have investigated the relationship between immunoglobulins and sepsis, Bermejo-Martín et al26 demonstrated that the combined presence of low levels of IgG1, IgM and IgA in plasma was associated with reduced survival for cases of severe sepsis or septic shock. These results suggest that we should continue the investigation of the target subgroup of patients with CAP, probably using immunoscores with different immunoglobulins to predict prognosis, whereas the use of IVIG as adjunctive treatment during the acute phase of the disease may improve outcome and reduce mortality.

Data supporting the use of IVIG remains controversial. Werdan et al27 in a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicentre trial (the SBITS study), the administration of intravenous monoclonal IgG did not reduce 28-day mortality in patients with sepsis. However, studies with polyclonal IVIG have shown a reduction in mortality, with a trend in favour of immunoglobulin preparations enriched with IgM.28 29 Data of systematic reviews and meta-analyses provided evidence of the effect of polyclonal IVIG to reduce mortality in patients with severe sepsis or septic shock.30–32 Further evidence is needed from large, well-designed randomised controlled trials to use IGIV in pneumonia to confirm whether these promising results are applicable to patients with sepsis caused by pneumonia.

This is the first study of a population with CAP in which immunological status was evaluated. Also, three different levels of CAP severity according to the level of care and CURB-65 severity score were separately assessed, showing that hypogammaglobulinaemia may be postulated as a prognostic factor only in critically ill patients with CAP, with an increase in mortality in the presence of low serum immunoglobulin levels. The analysis of the major immunoglobulins and IgG subclasses allowed us to identify that the IgG group especially IgG1 and IgG2 subtypes were those related to prognosis of CAP. Some limitations should be mentioned. Despite strict exclusion criteria, it is unknown whether some patients with low immunoglobulin levels may have had some immunodeficiency disease still undiagnosed. The lack of follow-up during the convalescent phase does not allow distinguishing patients with acquired immunodeficiency caused by CAP from those with deficient immunological status at baseline. On the other hand, although all patients with CAP requiring ICU admission were included in the study, patients with less severe disease, especially those treated as outpatients, may be well under-represented given that physicians did not always order a chest X-ray to establish the diagnosis of CAP, or consider it necessary to draw a blood sample to assess the immunological status on the first day of consultation.

In summary, this study shows that patients with severe CAP admitted to the ICU showed lower levels of circulating immunoglobulins than non-ICU patients and that this IgG deficiency is associated with a higher mortality.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Marta Pulido, MD, for editing the manuscript and editorial assistance. This article is part of a doctoral thesis, published online beforehand: http//tdx.cat/bitstream/handle/10803/377750/mcdltt1de1pdf?sequence=1, in UAB (University Autonoma Barcelona) digital repository of documentary TDX (Tesis Doctorals en Xarxa).

Footnotes

Contributors: MCdlT was responsible for the study design, selection of patients, interpretation of analysis, search of literature, writing and submitting of the manuscript. PT was responsible for the study design, selection of patients and writing of the manuscript. MS-P contributed to the methodological assessment, criteria for analysis, statistical analysis, interpretation of data and writing of the manuscript. EP provided criteria for analysis, and participated in the statistical analysis, interpretation of data and writing of the manuscript. EG and EV were involved in the selection of patients and data collection. JCY and AT contributed to the methodological assessment and writing of the manuscript. JA contributed to the study design, selection of patients, search of literature and writing of the manuscript. All authors have seen and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding: This work was supported by a grant (08/PI 090448) from Fondo de Investigaciones Sanitarias (FIS) and CIBER de Respiratorio (06/06/0028), Madrid, Spain and a grant from ‘Fundació Salut del Consorci Sanitari del Maresme’.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Consorci Sanitari del Maresme (Barcelona, Spain).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Almirall J, Bolíbar I, Vidal J et al. Epidemiology of community-acquired pneumonia in adults: a population-based study. Eur Respir J 2000;15:757–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Woodhead MA, Macfarlane JT, McCracken JS et al. Prospective study of the aetiology and outcome of pneumonia in the community. Lancet 1987;2:671–4. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(87)90430-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jokinen C, Heiskanen L, Juvonen H et al. Incidence of community-acquired pneumonia in the population of four municipalities in eastern Finland. Am J Epidemiol 1993;137:977–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mandell LA, Wunderink RG, Anzueto A et al. Infectious Diseases Society of America/American Thoracic Society consensus guidelines on the management of community-acquired pneumonia in adults. Clin Infect Dis 2007;44:S27–72. doi:10.1086/511159 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Marshall JC. Sepsis: current status, future prospects. Curr Opin Crit Care 2004;10:250–64. doi:10.1097/01.ccx.0000134877.60312.f3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Meijvis SCA, van de Garde EMW, Rijkers GT et al. Treatment with anti-inflammatory drugs in community-acquired pneumonia. J Intern Med 2012;272:25–35. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2796.2012.02554.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fernandez-Serrano S, Dorca J, Coromines M et al. Molecular inflammatory responses measured in blood of patients with severe community-acquired pneumonia. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol 2003;10:813–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lucas M, Lee M, Lortan J et al. Infection outcomes in patients with common variable immunodeficiency disorders: relationship to immunoglobulin therapy over 22 years. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2010;125:1354–60. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2010.02.040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Skull S, Kemp A. Treatment of hypogammaglobulinaemia with intravenous immunoglobulin, 1973–93. Arch Dis Child 1996;74:527–30. doi:10.1136/adc.74.6.527 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.de Gracia J, Vendrell M, Alvarez A et al. Immunoglobulin therapy to control lung damage in patients with common variable immunodeficiency. Int Immunopharmacol 2004;4:745–53. doi:10.1016/j.intimp.2004.02.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Orange JS, Hossny EM, Weiler CR et al. Use of intravenous immunoglobulin in human disease: a review of evidence by members of the Primary Immunodeficiency Committee of the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2006;117(4 Suppl):S525–53. doi:10.1016/j.jaci.2006.01.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kaul R, McGeer A, Norrby-Teglund A et al. Intravenous immunoglobulin therapy for streptococcal toxic shock syndrome—a comparative observational study. The Canadian Streptococcal Study Group. Clin Infect Dis 1999;28:800–7. doi:10.1086/515199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hartung HP, Mouthon L, Ahmed R et al. Clinical applications of intravenous immunoglobulins (IVIg)—beyond immunodeficiencies and neurology. Clin Exp Immunol 2009;158(Suppl 1):23–33. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2249.2009.04024.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Alfageme I, Aspa J, Bello S et al. , Grupo de Estudio de la Neumonía Adquirida en la Comunidad. Area de Tuberculosis e Infecciones Respiratorias (TIR)-SEPAR. Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of community-acquired pneumonia. Spanish Society of Pulmonology and Thoracic Surgery (SEPAR). Arch Bronconeumol 2005;41:279–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.British Thoracic Society Standards of Care Committee. BTS guidelines for the management of community acquired pneumonia in adults. Thorax 2001;56(Suppl 4):IV1–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Whicher JT, Price CP, Spencer K. Immunonephelometric and immunoturbidimetric assays for proteins. Crit Rev Clin Lab Sci 1983;18:213–60. doi:10.3109/10408368209085072 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.de la Torre MC, Bolíbar I, Vendrell M et al. Serum immunoglobulins in the infected and convalescent phases in community-acquired pneumonia. Respir Med 2013;107:2038–45. doi:10.1016/j.rmed.2013.09.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.De Gracia J, Rodrigo MJ, Morell F et al. IgG subclass deficiencies associated with bronchiectasis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1966;153:650–5. doi:10.1164/ajrccm.153.2.8564113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Feldman C, Mahomed AG, Mahida P et al. IgG subclasses in previously healthy adult patients with acute community-acquired pneumonia. S Afr Med J 1996;86:600–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Herer B, Labrousse F, Mordelet-Dambrine M et al. Selective IgG subclass deficiencies and antibody responses to pneumococcal capsular polysaccharide antigen in adult community-acquired pneumonia. Am Rev Respir Dis 1990;142:854–7. doi:10.1164/ajrccm/142.4.854 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gordon CL, Johnson PD, Permezel M et al. Association between severe pandemic 2009 influenza A (H1N1) virus infection and immunoglobulin G(2) subclass deficiency. Clin Infect Dis 2010;50:672–8. doi:10.1086/650462 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gordon CL, Holmes NE, Grayson ML et al. Comparison of immunoglobulin G subclass concentrations in severe community-acquired pneumonia and severe pandemic 2009 influenza A (H1N1) infection. Clin Vaccine Immunol 2012;19:446–8. doi:10.1128/CVI.05518-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Justel M, Socias L, Almansa R et al. IgM levels in plasma predict outcome in severe pandemic influenza. J Clin Virol 2013;58:564–7. doi:10.1016/j.jcv.2013.09.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hukuhara H, Shigeno Y, Saito A. Serum levels of healthy adult humans and changes of IgG subclass levels between infected and convalescent phase in respiratory infections. Kansenshogaku Zasshi 1991;65:564–70. doi:10.11150/kansenshogakuzasshi1970.65.564 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.de la Torre MC, Palomera E, Serra-Prat M et al. IgG2 as an independent risk factor for mortality in patients with community-acquired pneumonia. J Crit Care 2016;35:115–19. doi:10.1016/j.jcrc.2016.05.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bermejo-Martín JF, Rodriguez-Fernandez A, Herrán-Monge R et al. Immunoglobulins IgG1, IgM and IgA: a synergistic team influencing survival in sepsis. J Intern Med 2014;276:404–12. doi:10.1111/joim.12265 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Werdan K, Pilz G, Bujdoso O et al. Score-based immunoglobulin G therapy of patients with sepsis: the SBITS study. Crit Care Med 2007;35:2693–701. doi:10.1097/01.CCM.0000295426.37471.79 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pildal J, Gotzsche PC. Polyclonal immunoglobulin for treatment of bacterial sepsis: a systematic review. Clin Infec Dis 2004;39:38–46. doi:10.1086/421089 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kreymann KG, de Heer G, Nierhaus A et al. Use of polyclonal immunoglobulins as adjunctive therapy for sepsis or septic shock. Crit Care Med 2007;35:2677–85. doi:10.1097/01.CCM.0000295263.12774.97 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Alejandria MM, Langsang MA, Dans LF et al. Intravenous immunoglobulin for treating sepsis and septic shock. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2002;(1):CD001090 doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001090 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Turgeon AF, Hutton B, Fergusson DA et al. Meta-analysis: intravenous immunoglobulin in critically ill adult patients with sepsis. Ann Intern Med 2007;146:193–203. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-146-3-200702060-00009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Laupland KB, Kirkpatrick AW, Delaney A. Polyclonal intravenous immunoglobulin for the treatment of severe sepsis and septic shock in critically ill adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit Care Med 2007;35:2686–92. doi:10.1097/01.CCM.0000295312.13466.1C [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjresp-2016-000152supp.pdf (77.2KB, pdf)