Abstract

Previously, we reported that Sebox is a new maternal effect gene (MEG) that is required for early embryo development beyond the two-cell (2C) stage because this gene orchestrates the expression of important genes for zygotic genome activation (ZGA). However, regulators of Sebox expression remain unknown. Therefore, the objectives of the present study were to use bioinformatics tools to identify such regulatory microRNAs (miRNAs) and to determine the effects of the identified miRNAs on Sebox expression. Using computational algorithms, we identified a motif within the 3′UTR of Sebox mRNA that is specific to the seed region of the miR-125 family, which includes miR-125a-5p, miR-125b-5p and miR-351-5p. During our search for miRNAs, we found that the Lin28a 3′UTR also contains the same binding motif for the seed region of the miR-125 family. In addition, we confirmed that Lin28a also plays a role as a MEG and affects ZGA at the 2C stage, without affecting oocyte maturation or fertilization. Thus, we provide the first report indicating that the miR-125 family plays a crucial role in regulating MEGs related to the 2C block and in regulating ZGA through methods such as affecting Sebox and Lin28a in oocytes and embryos.

Keywords: Sebox, Lin28a, miR-125 family, translational regulation, bioinformatics

1. Background

Gene expression is a multi-step process that is regulated at both the transcriptional and translational levels as well as by the turnover of mRNAs and proteins [1]. MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are a class of endogenous, single-stranded and non-coding small RNAs (approximately 21–25 nucleotides) that primarily bind to complementary sequences in the 3′UTRs of their target mRNAs; this binding results in mRNA degradation and/or repression of mRNA translation [2]. Complete complementarity between miRNA and mRNA rarely occurs in mammals, but binding at the seed region (6–8 nucleotides at the 5′ end of the miRNA that exactly complements the target mRNA) sufficiently suppresses expression of that specific gene [3]. In general, one gene can be regulated by several miRNAs, and one miRNA can regulate the expression of several target genes [3].

miRNAs are known to play an essential role in the regulation of normal development, disease status and many other physiological processes, including fertility. miRNAs exhibit dynamic expression profiles in oocytes and regulate the expression of many maternal genes in oocytes and embryos. Specifically, disruption of Dicer, a key enzyme involved in miRNA processing, results in meiotic arrest and severe spindle and chromosomal segregation defects in oocytes [4]. Some miRNAs are abundant in the immature oocyte and are then depleted throughout oocyte maturation, while others are relatively stable [5]. The differential expression of miRNAs is spatially and temporally regulated during the completion of oocyte meiosis and early embryo development [6]. Interestingly, the clustered miRNAs miR-430 and miR-309 have been linked to maternal mRNA clearance during the maternal-to-zygotic transition (MZT) [7,8].

During oogenesis, maternal effect genes (MEGs) are produced and accumulate in oocytes and function in the completion of fertilization, embryonic cell division, zygotic genome activation (ZGA) and early embryogenesis [9]. Abnormalities in the expression of MEGs result in defective embryogenesis [10], and disruption of MEGs such as Mater [11], Ube2a [12], Brg1 [13], Padi6 [14], Basonuclin [15] and Nlrp2 [16] disrupts ZGA and impairs embryo development, causing arrest at the two-cell (2C) stage, referred to as the 2C block in mice.

In a previous study, we found that the skin-embryo-brain-oocyte homeobox (Sebox) is also required for normal early embryo development, especially development at the 2C stage, and reported Sebox as a new candidate MEG [17]. Sebox is a mouse paired-like homeobox gene that encodes a homeodomain-containing protein [18]. Compared with its expression in metaphase II (MII) oocytes, Sebox expression is high in germinal vesicle (GV) oocytes and persists until ZGA occurs in mice [17]. Despite the specific and marked silencing of Sebox through Sebox RNA interference (RNAi), the oocytes' maturation rate, spindle configuration, chromosome organization and gross morphology were not affected [17]. However, silencing Sebox at the pronuclear (PN) stage arrested embryonic development at the 2C stage [17]. We confirmed that this developmental arrest in Sebox-silenced embryos was due to the incomplete degradation of several maternal factors (c-mos, Gbx2 and Gdf9), with the concurrent aberrant expression of certain ZGA markers (Mt1a, Rpl23, Ube2a and Wee1) [19]. Despite the importance of Sebox in the regulation of embryo development, regulatory mechanisms for Sebox expression are not yet well understood.

Therefore, the objectives of the present study were to identify miRNAs that regulate Sebox expression and to evaluate their function during preimplantational embryonic development. While we were cross-checking multiple computational algorithms, we discovered that the seed region of miR-125 family members is specific to the miRNA response element (MRE) within the 3′UTR of Sebox mRNA. In addition, these computational methods also revealed that Lin-28 homologue A (Lin28a) mRNA has the same conserved miR-125 family target site in its 3′UTR region. Therefore, we extended the aim of our study to include evaluation of the regulatory effect of the miR-125 family on the expression of Lin28a as well as Sebox.

2. Material and methods

2.1. Animals

Female imprinting control region (ICR) mice were obtained from Koatech (Pyeoungtack) and mated to male mice of the same strain to produce embryos in the breeding facility at the CHA Stem Cell Institute of CHA University. All described procedures were reviewed and approved by the University of Science Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and were conducted in accordance with the Guiding Principles for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.

2.2. Reagents

Chemicals and reagents were obtained from Sigma Chemical Corporation unless otherwise noted.

2.3. Isolation of oocytes and embryos

To isolate GV oocytes from preovulatory follicles, four-week-old female ICR mice were injected with 5 IU of eCG and sacrificed 46 h later. Cumulus-enclosed oocyte complexes (COCs) were recovered from the ovaries by puncturing the preovulatory follicles with a 27-gauge needle. M2 medium containing 0.2 mM 3-isobutyl-1-methyl-xanthine (IBMX) was used to inhibit germinal vesicle breakdown (GVBD). Isolated oocytes were snap-frozen and stored at −70°C prior to RNA isolation. To obtain MII oocytes, we injected female mice with 5 IU eCG, followed by 5 IU hCG after 46 h. Superovulated MII oocytes were obtained from the oviduct 16 h after hCG injection. Cumulus cells surrounding MII oocytes were removed by treating COCs with hyaluronidase (300 U ml−1). Female mice in which superovulation was induced were mated, and embryos were obtained at specific time points after hCG injection as follows: PN 1-cell embryo at 18–20 h, 2C embryos at 44–46 h, 4C embryos at 56–58 h, 8C embryos at 68–70 h, morula (MO) stage at 80–85 h and blastocyst (BL) stage at 96–98 h.

2.4. Microinjection and in vitro culture

The GV oocytes were microinjected with miRNA mimics in M2 medium containing 0.2 mM IBMX. An injection pipette containing the miRNA mimic solution was inserted into the cytoplasm of an oocyte, and 10 pl of 2 μM miRNA mimic, 2 μM miRNA inhibitor or Lin28a small interfering RNA (siRNA; Dharmacon) was microinjected using a constant flow system (Femtojet; Eppendorf). To assess injection damage, oocytes were injected with a negative control miRNA mimic and control siRNA (Dharmacon), which were used as negative controls. To determine the rate of in vitro maturation, oocytes were cultured in M16 medium containing 0.2 mM IBMX for 24 h and then cultured in M16 medium alone for 16 h in 5% CO2 at 37°C. After the miRNA mimic microinjection experiments, the maturation stage of the oocytes was scored based on the presence of a GV oocyte, a polar body (MII oocyte) or neither a GV nor a polar body (MI oocyte).

2.5. Messenger RNA isolation in oocytes and quantitative real-time RT-PCR

Oocyte mRNA was isolated using the Dynabeads mRNA DIRECT Kit (Invitrogen Dynal AS) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Briefly, oocytes were suspended with lysis/binding buffer and mixed with pre-washed Dynabeads oligo dT25. After RNA binding, the beads were washed twice with buffer A and then with buffer B, and RNA was eluted with Tris–HCl via incubation at 72°C. The isolated mRNA was used as a template for reverse transcription using oligo(dT) primers according to the M-MLV protocol. PCR was performed with a single-oocyte-equivalent amount of cDNAs. The PCR conditions and primer sequences for the encoding genes are listed in table 1. Gene expression was quantified via real-time RT-PCR, as described previously [17].

Table 1.

Primer sequences and RT-PCR conditions. The annealing temperature was 60°C for all genes. F, forward primer; R, reverse primer.

| gene | primer sequence | product size |

|---|---|---|

| Lin28a | F: 5'-GCGAAGATCCAAAGGAGACA-3' | 206 bp |

| R: 5'-TGTGGATCTCTTCCTCTTCC-3' | ||

| Oct4 | F: 5'-CCGGAAGAGAAAGCGAACTA-3' | 393 bp |

| R: 5'-CAGTTTGAATGCATGGGAGA-3' | ||

| Klf4 | F: 5'-AAAAGAACAGCCACCCACAC-3' | 227 bp |

| R: 5'-GAAAAGGCCCTGTCACACTT-3' | ||

| Sox2 | F: 5'-AACCCCAAGATGCACAACTC-3' | 201 bp |

| R: 5'-TCCGGGAAGCGTGTACTTAT-3' | ||

| c-Myc | F: 5'-TGATGTGGTGTCTGTGGAGA-3' | 230 bp |

| R: 5'-TGTTGCTGATCTGCTTCAGG-3' | ||

| Nanog | F: 5'-CCAAAGGATGAAGTGCAAGC-3' | 106 bp |

| R: 5'-GCAATGGATGCTGGGATACT-3' | ||

| Dppa2 | F: 5'-CACAGACTACGCTACGCAATCA-3' | 245 bp |

| R: 5'-AGTGTCTCCGAAGTCTCAAATAG-3' | ||

| Dppa4 | F: 5'-GATACCTGCCCTCATTGACCCT-3' | 182 bp |

| R: 5'-CACACCACATTTCCCCTTTGACTTC-3' | ||

| Gata6 | F: 5'-CAACCACTACCTTATGGCGTAGAAA-3' | 354 bp |

| R: 5'-GGCCGTCTTGACCTGAATACTTGA-3' | ||

| Piwil2 | F: 5'-TTGTCATGTCGGACGGGAAGG-3' | 320 bp |

| R: 5'-CTCATTGCTGGCTGTCTCGTTTTGT-3' | ||

| Cbx1 | F: 5'-CTACGAGCAGTGTCACCCTTCA-3' | 295 bp |

| R: 5'-TTGCCTCCCTCTGACTTATCTG-3' | ||

| Hdac3 | F: 5'-TCCCGAGGAGAACTACAGCAGG-3' | 280 bp |

| R: 5'-GGACAATCATCAGGCCGTGAGA-3' | ||

| Tbpl1 | F: 5'-CGGAACAACAAAGCGAGAAACC-3' | 203 bp |

| R: 5'-AGATCACATCCGTGGGAAGACG-3' | ||

| eIF-1a | F: 5'-TTTGGTCACTACTCAGGAGG-3' | 149 bp |

| R: 5'-ATCAGAAGCAACTGGGACAC-3' | ||

| Mt1a | F: 5'-CACCAGATCTCGGAATGGAC-3' | 114 bp |

| R: 5'-AGCAGCTCTTCTTGCAGGAG-3' | ||

| Cdc2 | F: 5′-GGACTACAAGAACACCTTTC-3′ | 262 bp |

| R: 5′-CAGGAAGAGAGCCAACGGTA-3′ | ||

| Hsp70.1 | F: 5′-AACGTGCTCATCTTCGACCT-3′ | 185 bp |

| R: 5′-TGGCTGATGTCCTTCTTGTG-3′ | ||

| Muerv-l | F: 5′-TTGCTTCCTGTCCCCATAAC-3′ | 132 bp |

| R: 5′-AAAATGACCAGGGGGAAGTC-3′ | ||

| Rpl23 | F: 5′-CATGGTGATGGCCACAGTTA-3′ | 136 bp |

| R: 5′-GACCCCTGCGTTATCTTCAA-3′ | ||

| Ube2a | F: 5′-AATGGTTTGGAATGCGGTCA-3′ | 272 bp |

| R: 5′-TGTTTGCTGGACTATTGGGA-3′ | ||

| U2afbp-rs | F: 5′-TAAGCTGCAACCTGGAACCT-3′ | 109 bp |

| R: 5′-CCTGCGTACCATCTTCCATT-3′ | ||

| H1Foo | F: 5'-GCGAAACCGAAAGAGGTCAGAA-3' | 377 bp |

| R: 5'-TGGAGGAGGTCTTGGGAAGTAA-3' | ||

| Gapdh | F: 5'-ACCACAGTCCATGCCATCAC-3' | 452 bp |

| R: 5'-TCCACCACCCTGTTGCTGTA-3' |

2.6. Isolation of oocyte mature miRNA and quantitative real-time RT-PCR for miRNA

Mature miRNA was isolated from 20 GV and MII oocytes using a miRNeasy micro kit (Qiagen) and bacterial ribosomal RNA carrier (Roche) and reverse-transcribed with miScript II RT (Qiagen). To quantify the mRNA, quantitative real-time RT-PCR was performed with a single-oocyte-equivalent amount of cDNA as previously described [20]. The PCR conditions and primer sequences are shown in table 1. The quantitative real-time RT-PCR analysis was performed with a miScript SYBR Green PCR kit (Qiagen) and iCycler (Bio-Rad) with universal tag primers and specific mature miRNA primers (miScript Primer Assay; Qiagen). The expression level of each miRNA species in oocytes was normalized to that of RUN6-2. The relative expression levels of the target miRNAs were calculated using the 2−ΔΔCt method, and all analytic procedures were repeated at least three times.

2.7. Parthenogenetic activation and culture of activated oocytes

Mature oocytes were parthenogenetically activated by culturing them for 2 h in Ca2-free KSOM medium supplemented with 10 mM SrCl2 and 5 mg ml−1 cytochalasin B. The activated oocytes were then cultured in modified Chatot, Ziomek and Bavister (CZB) medium (37°C, 5% CO2) to monitor their development to the 2C stage.

2.8. In vitro fertilization

Sperm were collected from the caudal epididymides of eight-week-old male ICR mice (Koatech). The epididymis was incised to release sperm into M16 medium. The sperm were incubated in M16 medium for 1 h to allow capacitation. The zona pellucida (ZP) was removed from oocytes by treating them with Tyrode's solution (pH 2.5). After ZP thinning was observed using a microscope, the oocytes were transferred to M16 medium, and the cellular mass was washed out of the ZP by gentle pipetting. ZP-free MII eggs were then placed in a 200 μl droplet of M16 medium under mineral oil and inseminated with 2.5 × 104 ml−1 sperm. After 2 h, the oocytes were washed to remove unbound sperm and cultured in M16 medium for 5 h (37°C, 5% CO2) to observe PN formation.

2.9. Transcriptional activity assay

Newly synthesized RNAs (indicative of transcriptional activity) were visualized in embryos by applying 5-ethynyl uridine (EU) in an in vitro embryonic transcriptional activity assay [19,21]. The Click-iT RNA Imaging Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific) was used for these assays. After subjecting embryos to culture in 2 mM EU-supplemented M16 medium, the embryos were washed and fixed in 3.7% formaldehyde containing 0.2% Triton X-100. Finally, the embryos were sequentially immersed in reaction buffer, washed three times and examined via confocal microscopy (Leica).

2.10. Cell culture and miRNA mimic transfection

J1 mouse embryonic stem cells (mESCs) were purchased from ATCC. The mESCs were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium supplemented with 15% fetal calf serum (HyClone), 0.1 mM 2-mercaptoethanol (Sigma), 100 U ml−1 penicillin, 100 μg ml−1 streptomycin, 2 mM glutamine (Gibco) and 1000 U ml−1 LIF (Chemicon). The cells were routinely passaged at 80–90% confluence. The mESCs were transfected with 10 nM of each miRNA mimic (negative control, miR-125a-5p mimic, miR-125b-5p mimic and miR-351-5p mimic; Bioneer) using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen Corporation) transfection reagent in Opti-MEM media (Invitrogen Corporation) according to the manufacturer's directions. After 48 h, the cells were harvested for gene expression analysis.

2.11. Western blotting

Protein extracts were separated using 12% SDS-PAGE and transferred onto polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (Amersham Biosciences). The membranes were blocked for 1 h in Tris-buffered saline-Tween (TBST; 0.2 M NaCl, 0.1% Tween-20 and 10 mM Tris (pH 7.4)) containing 5% non-fat dry milk. The blocked membranes were then incubated with a goat polyclonal anti-Sebox antibody [17], goat polyclonal anti-c-Myc antibody (1 : 1000; Abcam), rabbit polyclonal anti-Lin28a antibody (1 : 1000; Abcam) or mouse monoclonal anti-α-tubulin antibody (1 : 1000; sc-8035, Santa Cruz Biotechnology) in TBST. After the incubation, the membranes were incubated with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-goat IgG (1 : 2000; A5420), anti-rabbit IgG (1 : 2000) or anti-mouse IgG (1 : 2000; A-2554) in TBST for 1 h at room temperature. After each step, the membranes were washed several times with TBST, and bound antibody was detected using an enhanced chemiluminescence detection system (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

2.12. DNA constructs

To generate the Sebox firefly luciferase reporter, the full-length sequence of the Sebox 3′UTR (NM_008759.2: 611-1285), encompassing the MRE of miR-125a-5p, miR-125b-5p and miR-351-5p, was amplified using the forward primer GCTAGCTTTAGGTGTAGAGCTTTTAAGT and the reverse primer AAGCTTTTAAAGCAAAGAGTTTTGTTTT. To generate the Lin28a firefly luciferase reporter, the sequence of the Lin28a 3′UTR (NM_145833.1: 1193-1846)-containing MRE was amplified using the forward primer GCTAGCGATGACAGGCAAAGAGGGTG and the reverse primer AAGCTTAGGCTTCCACTAATCTGGCA. The Sebox 3′UTR (675 bp) and Lin28a 3′UTR (654 bp) PCR products were digested with NheI and HindIII. Then, the digested PCR products were cloned into a NheI- and HindIII-opened pGL4.10 vector (Promega). The sequences of the constructs were confirmed by DNA sequencing.

2.13. Luciferase reporter assay

The effect of miRNA overexpression on the mouse Sebox or Lin28a 3′UTR was assessed in HEK 293 cells. Cells grown in 24-well plates were transfected with the following plasmids using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen Corporation): 100 ng of a plasmid encoding a firefly luciferase reporter fused with the mouse Sebox or Lin28a 3′UTR, 50 ng pRL-TK control plasmid (Renilla luciferase) and 10 nM miRNA mimics with or without 50 nM inhibitors. The cells were harvested 48 h later and assayed with a dual-luciferase assay system (Promega) and a Modulus microplate reader luminometer (Turner Biosystems). For signal normalization, the readout of firefly luciferase activity from non-transfected HEK 293 cells was subtracted as background, and the activity of the firefly luciferase was then normalized to that of the co-transfected control Renilla luciferase. All results are the mean of at least three independent experiments. Significant downregulation of normalized luciferase expression was identified using paired t-tests.

2.14. Statistical analysis

The quantitative real-time RT-PCR data were statistically analysed using Student's t-tests. The data derived from at least three separate and independent experiments were expressed as the mean ± s.e.m. The p-values for each gene in the miRNA mimic or miRNA inhibitor microinjection group and the negative control miRNA microinjection group were calculated based on paired t-tests of triplicate ΔCT values, and a value of p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

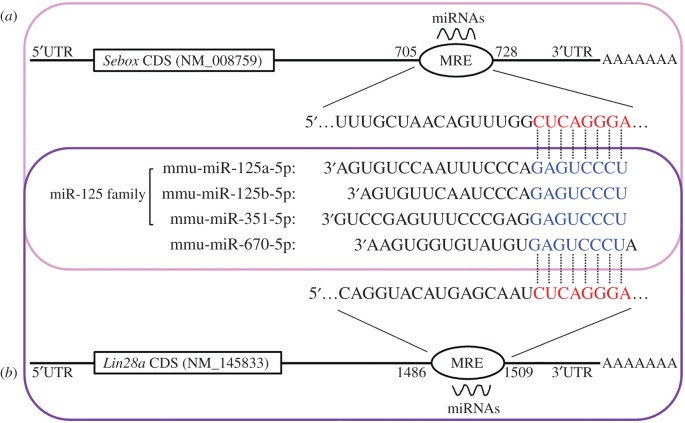

3.1. The miR-125 family is predicted to target Sebox as well as Lin28a

Computational approaches have become an indispensable tool for understanding and predicting miRNA target gene interactions. To identify miRNAs capable of targeting Sebox, we identified potential miRNA binding sites, known as MREs, in the Sebox 3′UTR using bioinformatic tools and then confirmed whether those putative sites were indeed functional. Because miRNAs bind to their targets with imperfect complementary sequences, algorithms that predict miRNA binding sites in single mRNAs often produce a large number of false positives. We used TargetScan (http://www.targetscan.org), miRanda (http://www.microrna.org) and miRmap (http://mirmap.ezlab.org) to select sequences showing complete complementarity between the miRNA seed region and the 3′UTR of the mRNA; these algorithm-based tools help to eliminate false positives. We identified one predicted MRE in the 3′UTR of Sebox mRNA (NM_008759: position 721–728) and four miRNAs (miR-125a-5p, miR-125b-5p, miR-351-5p and miR-670-5p) that were predicted to target Sebox (figure 1a, pink box). Among these four putative miRNAs identified using TargetScan, miRanda and miRmap, miR-125a-5p, miR-125b-5p and miR-351-5p are members of the miR-125 family, whereas miR-670-5p is not (figure 1). Interestingly, the same sequence of the MRE predicted for the four miRNAs was also found in the 3′UTR of Lin28a mRNA (NM_145833: position 1502–1509; figure 1b, violet box). Each computational algorithm provides a score that can be employed to predict mRNA–miRNA interactions. These algorithms use different strategies to rank predictions; in some cases, the larger positive values represent more trustable predictions, whereas in other cases, the smaller values are better. Using these three algorithms, we identified a target prediction score for the interactions between each miR-125 family member and the target mRNAs, Sebox and Lin28a. The electronic supplementary material, table S1 lists the estimated prediction score for the interactions between the miR-125 family members and each target MEG. We found that the sequences with higher scoring predictions were the strongest candidates for validation experiments, and we identified miR-125 family binding sites in the Sebox and Lin28a mRNAs (electronic supplementary material, table S1).

Figure 1.

miRNAs predicted to target Sebox and Lin28a. The predicted miRNA (miR-125a-5p, miR-125b-5p, miR-351-5p and miR-670-5p) targeting sequence located in the 3′UTR of Sebox (a, pink box) and/or Lin28a (b, violet box) mRNA was found using TargetScan, miRanda and miRmap. Red letters indicate the MRE in the 3′UTR of Sebox and Lin28a mRNA, while blue letters indicate the seed region of each miRNA we identified.

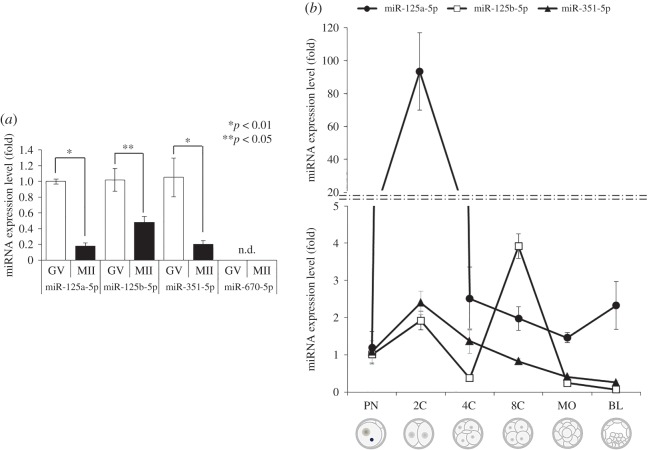

3.2. miR-125 family members are expressed in oocytes and embryos

Expression profiles of the members of the miR-125 family were examined in oocytes and early developmental stage embryos via quantitative real-time RT-PCR. We found that the members of the miR-125 family were expressed in oocytes, whereas miR-670-5p was not (figure 2a). Expression of the miR-125 family members was higher in GV oocytes than in MII oocytes (figure 2a). Because miR-670-5p was not detected in oocytes, we decided to exclude miR-670-5p from further investigation. miR-125a-5p expression was detected in PN-stage embryos, dramatically increased at the 2C stage, and then decreased at stage 4C and after (figure 2b; filled circles). miR-125b-5p expression was detected in PN-stage embryos, slightly increased at the 2C stage, and then decreased at the 4C stage. Interestingly, miR-125b-5p expression dramatically increased at the 8C stage and then decreased to an undetectable level from MO- to BL-stage embryos (figure 2b; open squares). miR-351-5p expression was detected in PN-stage embryos, slightly increased at the 2C stage and gradually decreased thereafter (figure 2b; filled triangles).

Figure 2.

Expression of miR-125 family members in oocytes and early developmental embryos. (a) Expression of miR-125 family members was detected in oocytes. Expression of the four predicted miRNAs in mouse GV and MII oocytes was evaluated using quantitative real-time RT-PCR analysis with mature miRNA primers. n.d., detected. *p < 0.01, **p < 0.05, relative to the expression level in GV oocytes. (b) Relative expression levels of miR-125 family members during early embryogenesis. The relative expression of miR-125a-5p, miR-125b-5p and miR-351-5p in single embryos throughout development was measured by quantitative real-time RT-PCR. Experiments were repeated at least three times, and the data are expressed as the mean ± s.e.m. Filled circles, miR-125a-5p; open squares, miR-125b-5p; filled triangles, miR-351-5p.

3.3. The miR-125 family directly targets the 3′UTR of Sebox and Lin28a

The in silico analysis of putative miRNAs and their targets Sebox and Lin28a indicated that miR-125a-5p, miR-125b-5p and miR-351-5p may regulate the expression of Sebox and Lin28a. Therefore, we sought to determine whether the miR-125 family can regulate Sebox and Lin28a expression in oocytes and undifferentiated mESCs. As an assay of miRNA function, we evaluated the ability of each miR-125 family member to target endogenous Sebox and Lin28a mRNAs in oocytes and mESCs by microinjecting or transfecting cells with mimics of each miR-125 family member. When oocytes were microinjected with a mimic of miR-125a-5p or miR-125b-5p, Sebox transcript levels were markedly reduced (electronic supplementary material, figure S1a). Unexpectedly, microinjection of the miR-351-5p mimic significantly increased oocyte-stored Sebox mRNA (electronic supplementary material, figure S1a). Several studies have reported that the endogenous miRNA targets have significantly higher expression levels following the transfection of mimics due to the low effectiveness of suppression of the endogenous miRNA pathway [15,22]. Sebox mRNA levels were slightly increased when mESCs were transfected with miR-125a-5p or miR-125b-5p mimics, whereas Sebox mRNA levels were slightly decreased following miR-351-5p mimic transfection, but none of these changes were statistically significant (electronic supplementary material, figure S1b). These results show that treating oocytes with mimics of miR-125 family members resulted in an inconsistent pattern of endogenous Sebox mRNA regulation. However, the expression of Lin28a transcripts in oocytes was markedly reduced when the oocytes were microinjected with mimics of each miR-125 family member (electronic supplementary material, figure S1c). Lin28a mRNA levels were significantly decreased when mESCs were transfected with miR-125a-5p and miR-125b-5p but not when they were transfected with miR-351-5p (electronic supplementary material, figure S1d). These results indicate that the identified miRNAs did regulate the expression of the target genes Sebox and Lin28a, but the transcript expression profiles of Sebox and Lin28a varied among the different cell types.

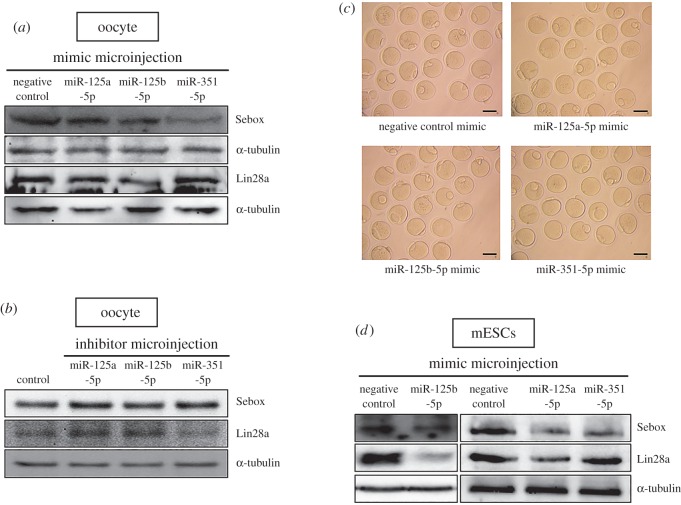

3.4. Mimics and inhibitors of the miR-125 family regulate the level of Sebox and Lin28a translation

We analysed whether overexpression of miR-125 family members affected Sebox and Lin28a protein expression. Sebox translational levels were negatively regulated by the overexpression of mimics of each miR-125 family member in oocytes (figure 3a), while enhanced Sebox protein expression was observed in oocytes that were microinjected with inhibitors of miR-125 family members (figure 3b). In addition, Lin28a protein translation was also reduced when oocytes were microinjected with mimics of miR-125a-5p and miR-125b-5p but not when they were microinjected with miR-351-5p mimics (figure 3a). However, after the levels of miR-125a-5p and miR-125b-5p were reduced in oocytes via inhibitor microinjection, Lin28a protein levels were also markedly elevated (figure 3b). In this case, the inhibitor of miR-351-5p again led to different results compared with the inhibitors of miR-125a-5p and miR-125b-5p (figure 3b). Although Sebox and Lin28a protein expression was markedly reduced following the microinjection of mimics of each miR-125 family member (figure 3a), oocyte nuclear maturation was not affected, and most of the oocytes extruded polar bodies and matured to the MII stage (figure 3c and table 2). No change in maturation rate was observed in the miR-125a-5p (91.3 ± 2.4), miR-125b-5p (92.3 ± 5.0), miR-351-5p (95.3 ± 3.0) or negative control (90.2 ± 3.2; figure 3c and table 2) groups. These results are highly supportive of our earlier data, indicating that the reduction of Sebox and Lin28a expression by the miR-125 family members did not affect the regulation of oocyte nuclear maturation.

Figure 3.

The miR-125 family regulates Sebox and Lin28a translation. Endogenous Sebox and Lin28a protein expression levels were detected by western blotting after miR-125 family members were overexpressed (a) or downregulated (b) in oocytes. The blots were reprobed with α-tubulin antibody as a loading control. (c) Photomicrographs of MII oocytes cultured in vitro after microinjection with mimics of each miR-125 family member. Disruption of Sebox and Lin28a translation by microinjection of mimics of each miR-125 family member did not affect normal oocyte nuclear maturation. Scale bars, 100 µm. (d) Western blotting was performed to detect the endogenous expression of Sebox and Lin28a in mESCs transfected with mimics of miR-125 family members.

Table 2.

In vitro maturation of mouse oocytes after GV oocytes were injected with mimics of each miR-125 family member. Common letters indicate no significant difference.

| number of oocytes (%) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| total | metaphase I | metaphase II | abnormal | |

| negative control mimic | 133 | 12 (9.0)a | 120 (90.2)b | 1 (0.8)c |

| miR-125a-5p mimic | 127 | 11 (8.7)a | 116 (91.3)b | 0 (0.0)c |

| miR-125b-5p mimic | 155 | 10 (6.5)a | 143 (92.3)b | 2 (1.3)c |

| miR-351-5p mimic | 149 | 5 (3.4)a | 142 (95.3)b | 2 (1.3)c |

After miR-125 family members were overexpressed in mESCs, Sebox protein levels were decreased (figure 3d). In addition, Lin28a protein levels were also markedly decreased in mESCs in which miR-125a-5p or miR-125b-5p was overexpressed (figure 3d). However, miR-351-5p overexpression did not affect Lin28a translation levels in mESCs (figure 3d). We found that miR-125a-5p and miR-125b-5p inhibited both Sebox and Lin28a protein expression, whereas miR-351-5p suppressed only Sebox protein expression.

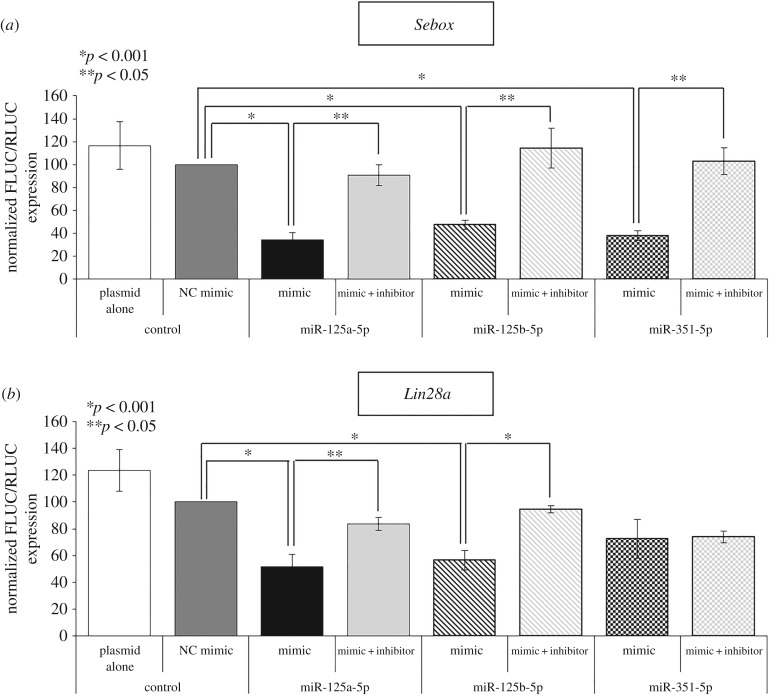

To confirm that the direct pairing of miR-125 family members and their target mRNA leads to suppression of translation, we performed a luciferase reporter assay. We measured the ability of miRNA overexpression to decrease the expression of firefly luciferase from an mRNA bearing the 3′UTR of Sebox (figure 4a) and Lin28a (figure 4b). We found that overexpression of all of the miRNAs significantly reduced the expression of firefly luciferase via targeting of the mouse Sebox 3′UTR. When miRNA mimics of miR-125a-5p (black bar), miR-125b-5p (black striped bar) and miR-351-5p (black checked bar) were each co-transfected with the Sebox 3′UTR luciferase reporter, the expression of firefly luciferase was decreased (by 2.9-fold, 2.1-fold and 2.6-fold, respectively) relative to the luciferase expression observed following transfection with the negative control mimic (dark grey bar; figure 4a). This reduction in expression by members of the miR-125 family was blocked by treatment with an inhibitor of each miRNA (figure 4a; light grey bar, light grey striped bar and light grey checked bar). Consistent with the decreased endogenous expression of Sebox, the luciferase activity for Lin28a expression was also significantly decreased when miR-125a-5p (black bar) or miR-125b-3p (black striped bar) was transfected (figure 4b). Meanwhile, miR-351-5p (black checked bar) had no effect on Lin28a expression (figure 4b), which is also consistent with the western blotting results (figure 3). These results indicate that direct binding between the miR-125 family members and the MRE in the 3′UTR of Sebox or Lin28a mRNA is capable of inhibiting Sebox and Lin28a post-transcriptional expression.

Figure 4.

Sebox and Lin28a are direct downstream targets of the miR-125 family. HEK 293T cell reporter-based assays of miR-125a-5p, miR-125b-5p and miR-351-5p targeting of Sebox mRNA (a) and Lin28a mRNA (b) through a targeting sequence located at the 3′UTR. Luciferase assays were performed to determine the effects of miRNA overexpression with or without inhibition of the Sebox or Lin28a 3′UTR. The level of firefly luciferase (FLUC) activity, normalized against that of Renilla luciferase (RLUC), is presented as a percentage of the signal obtained with transfection of a negative control (NC) mimic. Experiments were repeated at least three times, and the data are expressed as the mean ± s.e.m. Renilla luciferase was commonly used as an internal control. Plasmid alone and NC mimic groups were used as controls. *p < 0.001, **p < 0.05 compared with the NC mimic or with the mimic of each miR-125 family member.

3.5. Lin28a is a new maternal effect gene

Using computational approaches, the putative MRE of the miR-125 family was identified in the 3′UTR of Sebox and Lin28a (figure 1). Lin28a regulates the translation of genes important for ESC growth and maintenance; however, its function in mammalian oocytes and early developmental stage embryos is not known. Therefore, we investigated the potential role of Lin28a in oocyte maturation, fertilization and preimplantation embryonic development and determined whether Lin28a functions as a MEG like Sebox.

3.5.1. In vitro oocyte maturation occurs despite Lin28a RNAi

Like the levels of many other maternally expressed mRNAs, Lin28a mRNA levels were higher in oocytes than in embryos (electronic supplementary material, figure S2a) and were particularly high in GV oocytes (electronic supplementary material, figure S2b). Lin28a protein levels were also decreased during oocyte maturation (electronic supplementary material, figure S2c). To determine the role of Lin28a during oocyte maturation, Lin28a siRNA was microinjected into the cytoplasm of GV oocytes to silence Lin28a expression. Despite the knockdown of Lin28a mRNA (electronic supplementary material, figure S2d) and protein expression (electronic supplementary material, figure S2e), the oocytes all matured, and the MII oocytes were morphologically normal (table 3), suggesting that Lin28a is not a critical factor for nuclear maturation in mouse oocytes. A recent study reported that Lin28a regulates Oct4 at the post-transcriptional stage in human ESCs [23]. Oct4 binds to its own promoter region, Sox2 and Nanog also bind to the Oct4 promoter and Nanog binds to the promoters of all three factors. Thus, we evaluated the expression of other reprogramming factors in oocytes after the injection of Lin28a siRNA and found that c-Myc mRNA and protein levels in MII oocytes were considerably reduced by Lin28a siRNA (electronic supplementary material, figure S2d,e). However, other reprogramming factors (Oct4, Klf4 and Sox2) did not appear to be affected (electronic supplementary material, figure S2d).

Table 3.

In vitro maturation of mouse GV oocytes after Lin28a siRNA injection. Common letters indicate no significant difference.

| treatment | number of oocytes (%) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| total | GV | metaphase I | metaphase II | |

| no injection | 190 | 3 (1.6)a | 19 (10.0)b | 168 (88.4)c |

| control siRNA injection | 142 | 1 (0.7)a | 25 (17.6)b | 116 (81.4)c |

| Lin28a siRNA injection | 168 | 0 (0.0)a | 12 (7.1)b | 156 (92.9)c |

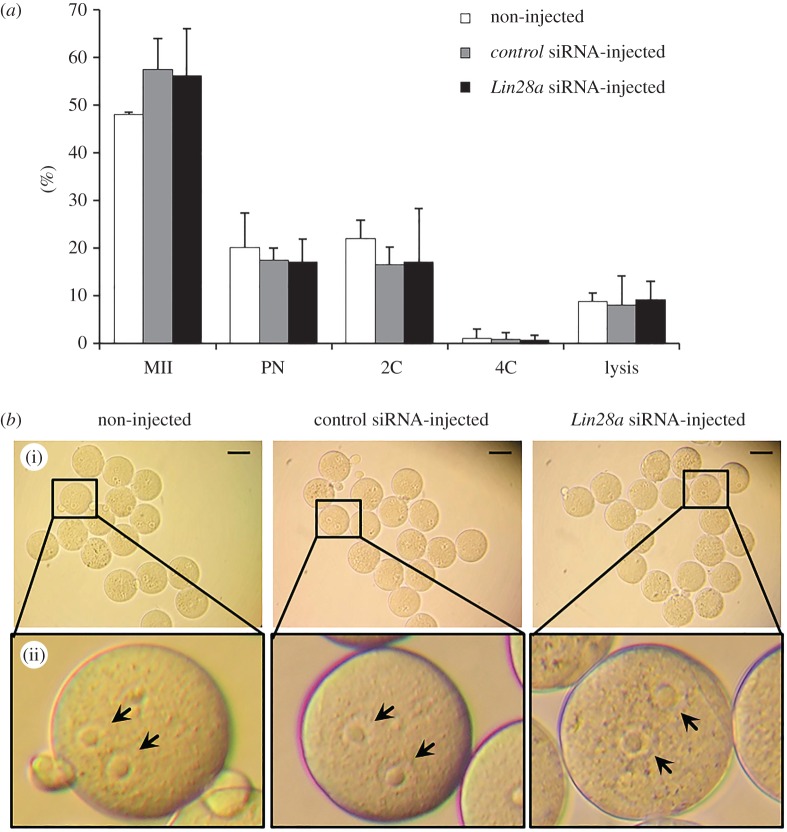

To verify that complete oocyte cytoplasmic maturation occurred after RNAi, Lin28a-silenced MII oocytes were parthenogenetically activated with strontium chloride. The development of the Lin28a-injected oocytes to the PN and 2C stages (17.7% and 15.7%, respectively) was similar to that of non-injected oocytes (20.8% and 21.6%) and of control siRNA-injected oocytes (17.2% and 16.4%; figure 5a). The role of Lin28a in preparing the oocyte for fertilization was further evaluated by in vitro fertilization (IVF). We found that PN formation was similar in the three groups (non-injected, 74.1%; control siRNA, 71.2%; Lin28a siRNA, 74.2%; figure 5b).

Figure 5.

Lin28a-silenced MII oocytes were activated parthenogenetically and formed PN embryos after fertilization. (a) GV oocytes injected with control siRNA or Lin28a siRNA were matured in vitro for 14 h. MII oocytes were activated with SrCl2 and cultured in CZB medium to observe parthenogenetic development. Activated oocytes were scored according to developmental stage. The results are expressed as the mean ± s.e.m. of three independent experiments. (b) Despite the reduction of Lin28a in MII oocytes, sperm penetration and PN formation occurred. Photomicrographs of PN-stage embryos after IVF. MII oocytes (i) injected with control siRNA or Lin28a siRNA appear similar to control oocytes. The images in (ii) are high-magnification images of the boxed area in (i). Arrows indicate well-formed pronuclei in the oocyte cytoplasm. Scale bars, 100 µm.

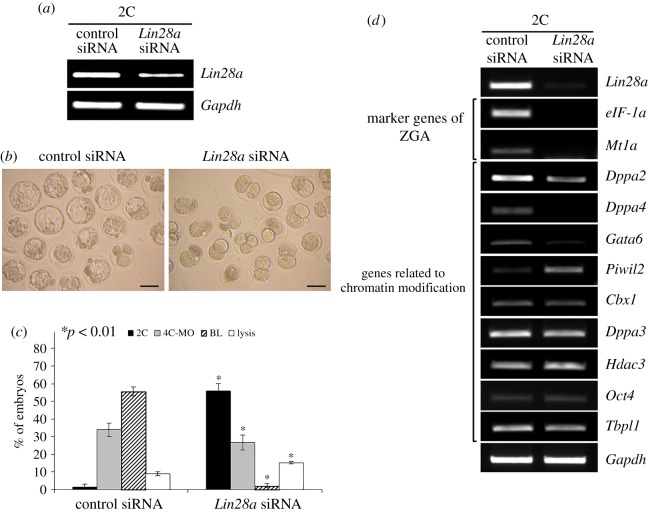

3.5.2. Lin28a silencing causes embryonic arrest at the two-cell stage

Because Lin28a RNAi did not affect oocyte maturation, activation, fertilization or PN formation, we evaluated the effect of Lin28a RNAi on preimplantation embryonic development. Lin28a RNAi reduced Lin28a mRNA levels by 80% compared with control siRNA (figure 6a) and blocked embryo development (figure 6b). Most of the control siRNA-injected PN embryos developed into four-cell MOs (33.92%) and BLs (55.66%), and only 1.52% of these embryos remained at the 2C stage (figure 6c). By contrast, the Lin28a-silenced embryos arrested at the 2C stage (55.82%); only 2.19% of these embryos developed to the BL stage (figure 6c). We found that ZGA markers (eIF-1a and Mt1a) were dramatically downregulated in Lin28a-silenced 2C stage embryos (figure 6d). Some chromatin modification genes were also downregulated (Dppa2, Dppa4 and Gata6), whereas Piwil2 was upregulated. By contrast, the expression of other chromatin modification genes (Cbx1, Dppa3, Hdac3, Oct4 and Tbpl1) did not change significantly (figure 6d).

Figure 6.

Lin28a siRNA caused developmental arrest at the 2C stage. (a) Microinjections of Lin28a siRNA reduced Lin28a mRNA levels, as assessed by RT-PCR. (b) Images of embryos 3 days after RNAi delivery. Most of the Lin28a siRNA-injected PN embryos were arrested at the 2C stage, whereas most of the control embryos developed further, up to the BL stage. Scale bars, 100 µm. (c) The developmental stage of PN embryos microinjected with control or Lin28a siRNA was scored after 3 days. The results are expressed as the mean ± s.e.m. of three experiments. *p < 0.01 compared with control siRNA-injected embryos (same stage). (d) Effect of Lin28a siRNA on the expression of genes related to ZGA and chromatin modification in embryos. PN embryos injected with control siRNA or Lin28a siRNA were matured in vitro. 2C-stage embryos were used to analyse gene expression.

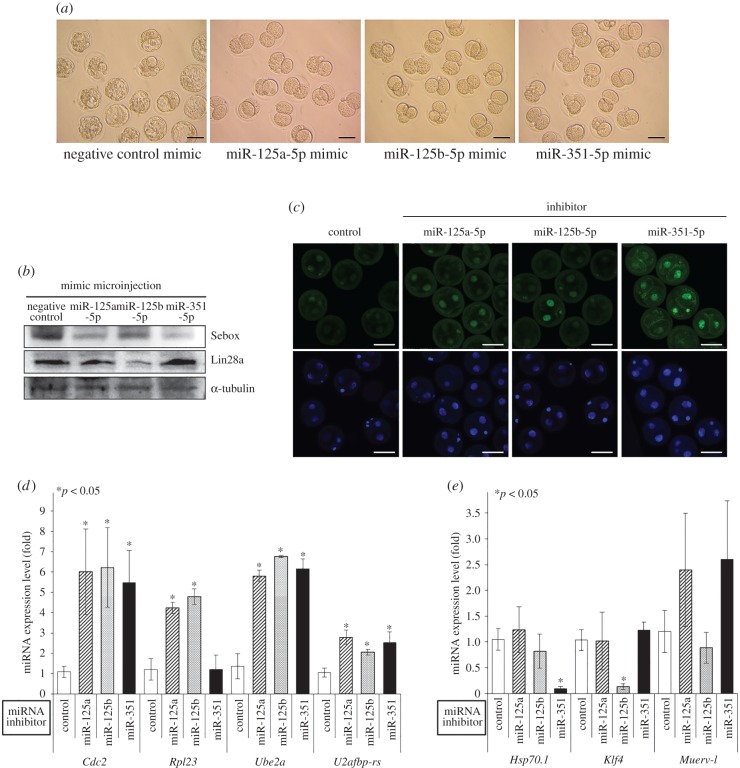

3.6. The miR-125 family suppresses early embryonic development via regulation of zygotic genome activation

We further investigated the effect of the miR-125 family on early embryonic development. As expected, microinjection of miR-125 family member mimics significantly affected embryonic development, causing it to stop at the 2C stage; the negative control mimic did not have this effect (figure 7a and table 4). The majority of the miR-125a-5p mimic-injected (84.3%), miR-125b-5p mimic-injected (65.5%) and miR-351-5p mimic-injected PN embryos (71.2%) were arrested at the 2C stage (table 4), similar to the effects of directly targeting Sebox [17] and Lin28a by dsRNA microinjection (figure 6). In addition, Sebox and Lin28a translation was markedly decreased by the overexpression of each miR-125 family member mimic in 2C embryos, except that the miR-351-5p mimic did not affect Lin28a translation (figure 7b). Taken together, these results strongly suggest that microinjection of miR-125 family member mimics caused abnormally low levels of Sebox and Lin28a in PN embryos, which led to developmental arrest of the early stage embryos.

Figure 7.

Simultaneous suppression of Sebox and Lin28a through treatment with mimics of miR-125 family members impaired early embryogenesis, resulting in the arrest of embryogenesis at the 2C stage. (a) Treatment with mimics of each miR-125 family member resulted in the arrest of embryo development at the 2C stage. Scale bars, 100 µm. (b) The treatment with miR-125 family member mimics reduced Sebox and/or Lin28a protein levels. Western blot results of endogenous Sebox and Lin28a expression in arrested 2C embryos that were microinjected with a negative control mimic or with mimics of each miR-125 family member. The blots were reprobed with an α-tubulin antibody as a loading control. (c) Embryonic transcriptional activity assay of miR-125 family-silenced 2C embryos. After inhibitors of the miR-125 family were microinjected into PN embryos, transcriptional activity was investigated based on nuclear EU incorporation (green) in 2C embryos. DNA was counterstained with Hoechst 33342 (blue). Scale bars, 50 µm. (d,e) Expression of ZGA markers in miR-125 family-depleted 2C embryos. The transcript level of ZGA markers was measured via quantitative real-time RT-PCR after PN embryos were treated with inhibitors of each miR-125 family member. *p < 0.05 compared with the control group.

Table 4.

In vitro development of mouse GV oocytes after PN embryos were microinjected with mimics of each miR-125 family member.

| number of embryos (%) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| total | 2 cell | 3 cell | 4/8 cell | MO | BL | |

| negative control mimic | 57 | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 10 (16.6) | 9 (17.0) | 38 (66.4) |

| miR-125a-5p mimic | 40 | 34 (84.2)a | 3 (7.9) | 3 (7.9) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0)a |

| miR-125b-5p mimic | 31 | 17 (65.5)a | 12 (29.7) | 1 (2.2) | 1 (2.6) | 0 (0.0)a |

| miR-351-5p mimic | 42 | 29 (71.2)a | 9 (21.2) | 4 (7.6) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0)a |

aValues are statistically significant at p<0.001 compared with the negative control mimic-injected group at the same stage.

To determine whether downregulation of the miR-125 family contributes to ZGA, we evaluated transcriptional activity in 2C embryos microinjected with inhibitors of the miR-125 family through EU incorporation. After the microinjection of each miR-125 family inhibitor, 2C embryos showed increased EU incorporation compared with the control group (figure 7c). These results indicate that the downregulation of the miR-125 family leads to increased transcriptional activity via upregulation of Sebox and Lin28a. In addition, we determined the expression of several ZGA markers in 2C embryos treated with inhibitors of the miR-125 family. As shown in figure 7d, the expression levels of Cdc2, Rpl23, Ube2a and U2afbp-rs were significantly upregulated, whereas no change in Rpl23 mRNA expression was observed under treatment with the inhibitor of miR-351-5p. By contrast, when PN embryos were microinjected with the inhibitors of miR-125b-5p and miR-351-5p, there was a marked reduction of the transcript levels of Klf4 and Hsp70.1, respectively, but no change in the expression of the remaining mRNAs was observed (figure 7e). The expression of Muerv-l was not significantly altered (figure 7e). These results strongly suggest that the miR-125 family is involved in the development of embryos beyond the 2C stage, through regulation of ZGA via control of Sebox and Lin28a expression.

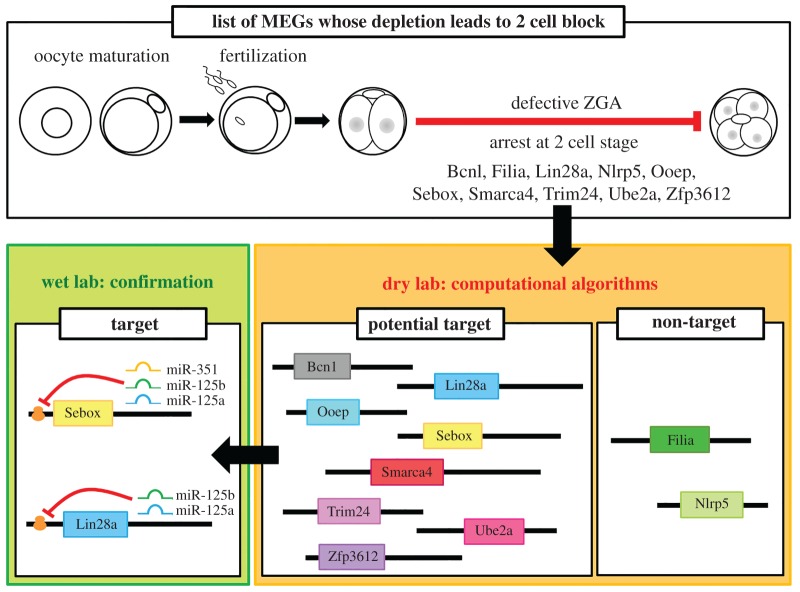

3.7. Bioinformatics results suggest that the miR-125 family targets most maternal effect genes related to two-cell arrest

The MEGs accumulate maternal factors during oogenesis and enable ZGA and the progression of early embryo development [10]. The disruption of several MEGs did not affect folliculogenesis, oogenesis, oocyte maturation, ovulation or fertilization but did affect ZGA in 2C-stage embryos and subsequently led to arrest at the 2C stage [10]. Because we found that miR-125 family members concurrently suppressed Sebox and Lin28a, we searched for more potential MEG targets of the miR-125 family using computational algorithms. We focused on MEGs for which disrupted expression had been reported to result in 2C arrest. The miRNA target prediction process, or so-called dry laboratory method, identified more MEG genes (Bcn1, Lin28a, Ooep, Sebox, Smarca4, Trim24, Ube2a and Zfp36l2) as potential targets of the miR-125 family; Filia and Nlrp5 were not identified as potential targets (figure 8; electronic supplementary material, table S2). Among the MEG genes identified as potential targets of the miR-125 family, we confirmed through wet laboratory methods that Sebox translation was suppressed by all members of the miR-125 family, while Lin28a translation was inhibited by miR-125a and miR-125b (figures 3, 7 and 8). Taking these results together, we suggest that most of the MEGs whose disruption resulted in 2C arrest were regulated by the miR-125 family. Further studies are required to assess whether the miR-125 family regulates ZGA by targeting the other predicted MEGs (Bcn1, Ooep, Smarca4, Trim24, Ube2a and Zfp36l2) in oocytes and embryos.

Figure 8.

Schematic diagram depicting the identification of potential target genes of the miR-125 family using computational algorithms. The depletion of MEGs, such as Bcn1, Filia, Lin28a, Nlrp5, Ooep, Sebox, Smarca4, Trim24, Ube2a and Zfp36l2, has been reported to result in defective embryogenesis, especially arrest at the 2C stage due to impaired ZGA. Using computational algorithms, we found that all of these MEGs, excluding Filia and Nlrp5, contained a binding motif for the seed region of the miR-125 family in the 3′UTR of their mRNA. Using wet laboratory experimental methods, we found that of these MEGs, Sebox and Lin28a play an important role during ZGA and are direct targets of miR-125 family members in oocytes and embryos. However, further wet laboratory experimental studies are needed to confirming the data acquired through dry laboratory methods.

4. Discussion

miRNAs are endogenous non-coding RNAs that control gene expression at the transcriptional as well as translational level. Recently, studies on miRNAs have focused on in silico analyses using bioinformatics tools to identify target mRNAs and determine the regulatory mechanisms between miRNAs and proteins. Numerous computational approaches for miRNA target prediction have already been developed, such as TargetScan, miRanda, miRmap, Diana-MicroT, TargetBoost, miTarget, MirTarget2, TargetSpy, TargetMiner, MultiMiTar, NBmiRTar and microT-ANN [24]. Because each algorithm has its own set of limitations, multiple computational algorithms are commonly used simultaneously to predict and identify miRNA targets through comparisons [25]. For most algorithms, including PicTar [26], TargetScan [27], miRanda [28], miRmap [29], TargetMiner [30], PITA [31] and SVMicrO [32], target prediction is based on seed matching, conservation, free energy and site accessibility [33]. miRNA binding sites can be categorized into four main categories according to the Watson–Crick match (A-U and G-C) between an miRNA seed sequence and its target: (i) the 6mer is an exact match between the miRNA seed sequence and the target mRNA for six nucleotides; (ii) the 7mer-m8 is an exact match to positions 2–8 of the 5′ end of the miRNA, which contains the seed region; (iii) the 7mer-1A is an exact match to positions 1–7 of the 5′ end of the miRNA, which contains the seed region; and (iv) the 8mer is an exact match to positions 1–8 of the 5′ end of the miRNA, which contains the seed region [3,33].

A combination of computational algorithms was used for miRNA–mRNA target prediction. In this study, we employed the TargetScan [27], miRanda [28] and miRmap [29] algorithms to predict miRNA–mRNA interactions. Using this approach, we found that the miR-125 family targets the 3′UTRs of the Sebox and Lin28a mRNAs and that the miR-125 family members miR-125a, miR-125b and miR-351 share the same seed sequence [34]. Through computational searches, we found that these three closely related miRNAs in the miR-125 family bind to eigtht conserved base pairs within the 3′UTR sequence of Sebox and Lin28a mRNA, CUCAGGGA. According to the miRNA categories of TargetScan, these identified miRNAs were categorized into the 8mer category. The seed regions of the miR-125 family members and the MRE in the 3′UTR of Sebox and Lin28a were completely complementary.

The miR-125 family is highly conserved and is expressed in mammals [35]. As one of the most important miRNA families, the miR-125 family has been implicated in a variety of developmental processes, including host immune responses and cancer and disease development, as either a repressor or promoter [35]. Each member of the miR-125 family is located on different murine chromosomes and is most probably expressed in clusters with other miRNAs, such as miR-99/miR-100 and let-7 family members, suggesting that their expression is regulated by different 5′ UTR regulatory sequences and transcription factors [36]. Among the members of the miR-125 family, miR-125a and miR-125b have been shown to suppress Lin28a expression during the early stages of ESC differentiation [37]. In this study, we also observed miR-125a- and miR-125b-mediated post-transcriptional control of Lin28a in mESCs. Thus, we suggest that the expression of Lin28a in mESCs is strictly regulated by miR-125a and miR-125b. In addition, Lin28a binds with various miRNAs, such as let-7, miR-30 and miR-9, and has multiple roles in development, differentiation, growth, metabolism and pluripotency [37,38]. Further studies examining the finely tuned Lin28a-mediated regulation of embryonic development are needed.

Importantly, let-7e and miR-125a share the same genomic locus, suggesting that these miRNAs originate from the same primary miRNA transcript and regulate Lin28a expression [37]. These findings also suggest that Lin28a expression may be extensively and complexly controlled by miR-125 family members and other Lin28a regulatory miRNAs. Importantly, we showed that miR-351-5p, another member of the miR-125 family, did not significantly affect endogenous Lin28a translation in mESCs and oocytes. These data indicate that although members of the miR-125 family share the same seed region sequence, expression of the Lin28a target gene was regulated differently by each miR-125 family member.

Sebox is a relatively new MEG that encodes a subfamily of homeodomain-containing homeobox proteins. Most homeodomain-containing proteins act as transcription factors and activate or repress the expression of other target genes. Whether Sebox is a transcription factor that binds to and controls the activity of other genes remains unclear. Therefore, further studies should determine whether Sebox represents a novel transcription factor and clarify mutual functional interactions between Sebox and its target genes. In mice, Sebox has recently been shown to affect both early oogenesis in the fetus and early embryogenesis, and it has also been reported to affect mesoderm formation in early amphibian embryos [17,19,39,40]. In this study, we provide the first report that Sebox, both mRNA and protein, is expressed in mESCs. Until now, however, Sebox has not been specifically referenced in any stem cell research study. Our observations demonstrate that miR-125 family members negatively regulate Sebox translational levels in mESCs and oocytes in a seed sequence-dependent manner. Furthermore, luciferase reporter analyses revealed the direct binding of miR-125 family members to the 3′ UTR of Sebox mRNA. The findings of this study suggest that future studies of the regulatory mechanisms by which the miR-125 family and its target Sebox mRNA play a role in maintaining the pluripotency and differentiation of mESCs will be of considerable interest.

Lin28a is a conserved RNA binding protein that was originally identified as a key regulator of developmental timing in Caenorhabditis elegans [41]. Lin28a is abundant in human and mouse ESCs, but its expression decreases during differentiation [42]. Lin28a appears to suppress miRNA-mediated differentiation in stem cells [43]. In addition, Lin28a was used together with Oct4, Sox2 and Nanog as a pluripotency reprogramming factor to reprogram fibroblasts to generate induced pluripotent stem cells [44]. Importantly, Lin28a is also highly expressed in oocytes and mESCs. Although Lin28a RNAi resulted in a marked decrease in both Lin28a mRNA and protein, these changes in oocytes did not affect the oocytes' competence for maturation and fertilization. Conversely, Lin28a knockdown in PN-stage embryos blocked preimplantational embryo development mainly at the 2C or 4C stage. Based on these observations of the present study, we conclude that Lin28a is a new MEG that has a pivotal function in early embryonic development, especially in 2C block and ZGA.

Maternal mRNAs and proteins accumulate in developing oocytes but are mostly degraded by the end of the 2C stage [45]. Maternal mRNAs and proteins are replaced by embryonic gene products during early embryonic development. This process, known as ZGA, is the first major developmental event that takes place after fertilization [46]. ZGA occurs around the PN to 2C stage in mice [47] and around the 4C to 8C stage in humans [48]. Zygotic gene activation is responsible for reprogramming gene expression, which establishes the totipotent state of each blastomere in cleavage-stage embryos [13]. Sebox plays a crucial role in preparing oocytes for embryonic development by orchestrating the expression of other important MEGs and ZGA markers [19]. Furthermore, our findings demonstrate that ZGA is also disrupted by Lin28a depletion. Therefore, we conclude that Sebox and Lin28a are mainly involved in the decay of maternal transcripts and ZGA during early embryogenesis. Likewise, as expected, we found that knockdown of the miR-125 family led to an increase Sebox and Lin28a protein levels during oocyte maturation and to an increase in the expression of genes related to ZGA during the MZT period. Based on these findings, we conclude that the miR-125 family is a novel regulator of ZGA that functions through the regulation of MEGs, for example, by modulating Sebox and Lin28a translation.

By using dry laboratory tools, we also found that miR-125 family members may regulate the expression of other MEGs that are involved in the 2C block of preimplantational embryonic development in vitro. This computational work has been inspired by the observation that miR-125 family members simultaneously regulate Sebox and Lin28a and that Sebox and Lin28a both function as MEGs during early embryonic development in vitro. As we expected, most of the MEGs related to features of the 2C block, excluding Nlrp5 and Filia, seemed to be regulated by miR-125 family members. This observation is also a very interesting and meaningful discovery and may open a new area of research to study the regulatory mechanisms of the timely expression and degradation of MEGs during early embryonic development.

5. Conclusion

This is the first report on the pivotal role of miR-125 family members, miR-125a-5p, miR-125b-5p and/or miR-351-5p, in the regulation of MEG expression, especially the expression of Sebox and Lin28a in oocytes, embryos and mESCs. This regulation is controlled via direct binding of miR-125 family members to Sebox and Lin28a mRNA, which causes translational repression. Our findings provide a promising foundation for future studies of the regulation of MEGs and/or reprogramming factors by miRNAs in oocytes, embryos and mESCs.

Supplementary Material

Data accessibility

The relevant data supporting this article have been uploaded as part of the electronic supplementary material, figures S1 and S2 and tables S1 and S2.

Authors' contributions

K.-H.K., Y.-M.S., and K.-A.L. conceived and designed the experiments; K.-H.K., Y.-M.S., E.-Y.K., S.-Y.L. and J.K. performed the experiments; K.-H.K., Y.-M.S., J.-J.K. and K.-A.L. analysed the data; K.-H.K., Y.-M.S. and K.-A.L. wrote the manuscript; and K.-H.K., J.-J.K. and K.-A.L. acquired financial support.

Competing interests

We have no competing interests.

Funding

This research was supported by the Basic Science Research Program of the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) and by the Ministry of Education (2009-0093821 and NRF-2015R1D1A1A01056595).

References

- 1.Schwanhausser B, Busse D, Li N, Dittmar G, Schuchhardt J, Wolf J, Chen W, Selbach M. 2011. Global quantification of mammalian gene expression control. Nature 473, 337–342. (doi:10.1038/nature10098) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bartel DP. 2009. MicroRNAs: target recognition and regulatory functions. Cell 136, 215–233. (doi:10.1016/j.cell.2009.01.002) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brennecke J, Stark A, Russell RB, Cohen SM. 2005. Principles of microRNA-target recognition. PLoS Biol. 3, e85 (doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0030085) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Murchison EP, Stein P, Xuan Z, Pan H, Zhang MQ, Schultz RM, Hannon GJ. 2007. Critical roles for Dicer in the female germline. Genes Dev. 21, 682–693. (doi:10.1101/gad.1521307) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tesfaye D, Worku D, Rings F, Phatsara C, Tholen E, Schellander K, Hoelker M. 2009. Identification and expression profiling of microRNAs during bovine oocyte maturation using heterologous approach. Mol. Reprod. Dev. 76, 665–677. (doi:10.1002/mrd.21005) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tang F, et al. 2007. Maternal microRNAs are essential for mouse zygotic development. Genes Dev. 21, 644–648. (doi:10.1101/gad.418707) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Giraldez AJ, Mishima Y, Rihel J, Grocock RJ, Van Dongen S, Inoue K, Enright AJ, Schier AF. 2006. Zebrafish MiR-430 promotes deadenylation and clearance of maternal mRNAs. Science 312, 75–79. (doi:10.1126/science.1122689) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bushati N, Stark A, Brennecke J, Cohen SM. 2008. Temporal reciprocity of miRNAs and their targets during the maternal-to-zygotic transition in Drosophila. Curr. Biol. 18, 501–506. (doi:10.1016/j.cub.2008.02.081) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Eppig JJ, Wigglesworth K. 2000. Development of mouse and rat oocytes in chimeric reaggregated ovaries after interspecific exchange of somatic and germ cell components. Biol. Reprod. 63, 1014–1023. (doi:10.1095/biolreprod63.4.1014) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kim KH, Lee KA. 2014. Maternal effect genes: findings and effects on mouse embryo development. Clin. Exp. Reprod. Med. 41, 47–61. (doi:10.5653/cerm.2014.41.2.47) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tong ZB, Gold L, Pfeifer KE, Dorward H, Lee E, Bondy CA, Dean J, Nelson LM. 2000. Mater, a maternal effect gene required for early embryonic development in mice. Nat. Genet. 26, 267–268. (doi:10.1038/81547) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Roest HP, Baarends WM, de Wit J, van Klaveren JW, Wassenaar E, Hoogerbrugge JW, van Cappellen WA, Hoeijmakers JH, Grootegoed JA. 2004. The ubiquitin-conjugating DNA repair enzyme HR6A is a maternal factor essential for early embryonic development in mice. Mol. Cell. Biol. 24, 5485–5495. (doi:10.1128/MCB.24.12.5485-5495.2004) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bultman SJ, Gebuhr TC, Pan H, Svoboda P, Schultz RM, Magnuson T. 2006. Maternal BRG1 regulates zygotic genome activation in the mouse. Genes Dev. 20, 1744–1754. (doi:10.1101/gad.1435106) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Esposito G, Vitale AM, Leijten FP, Strik AM, Koonen-Reemst AM, Yurttas P, Robben TJ, Coonrod S, Gossen JA. 2007. Peptidylarginine deiminase (PAD) 6 is essential for oocyte cytoskeletal sheet formation and female fertility. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 273, 25–31. (doi:10.1016/j.mce.2007.05.005) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Grimm D, Streetz KL, Jopling CL, Storm TA, Pandey K, Davis CR, Marion P, Salazar F, Kay MA. 2006. Fatality in mice due to oversaturation of cellular microRNA/short hairpin RNA pathways. Nature 441, 537–541. (doi:10.1038/nature04791) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Peng H, et al. 2012. Nlrp2, a maternal effect gene required for early embryonic development in the mouse. PLoS ONE 7, e30344 (doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0030344) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kim KH, Kim EY, Lee KA. 2008. SEBOX is essential for early embryogenesis at the two-cell stage in the mouse. Biol. Reprod. 79, 1192–1201. (doi:10.1095/biolreprod.108.068478) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cinquanta M, Rovescalli AC, Kozak CA, Nirenberg M. 2000. Mouse Sebox homeobox gene expression in skin, brain, oocytes, and two-cell embryos. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 97, 8904–8909. (doi:10.1073/pnas.97.16.8904) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Park MW, Kim KH, Kim EY, Lee SY, Ko JJ, Lee KA. 2015. Associations among Sebox and other MEGs and its effects on early embryogenesis. PLoS ONE 10, e0115050 (doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0115050) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kim KH, Kim EY, Kim Y, Kim E, Lee HS, Yoon SY, Lee KA. 2011. Gas6 downregulation impaired cytoplasmic maturation and pronuclear formation independent to the MPF activity. PLoS ONE 6, e23304 (doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0023304) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Waksmundzka M, Debey P. 2001. Electric field-mediated BrUTP uptake by mouse oocytes, eggs, and embryos. Mol. Reprod. Dev. 58, 173–179. (doi:10.1002/1098-2795(200102)58:2<173::AID-MRD6>3.0.CO;2-2) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Khan AA, Betel D, Miller ML, Sander C, Leslie CS, Marks DS. 2009. Transfection of small RNAs globally perturbs gene regulation by endogenous microRNAs. Nat. Biotechnol. 27, 549–555. (doi:10.1038/nbt.1543) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Qiu C, Ma Y, Wang J, Peng S, Huang Y. 2010. Lin28-mediated post-transcriptional regulation of Oct4 expression in human embryonic stem cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 38, 1240–1248. (doi:10.1093/nar/gkp1071) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kleftogiannis D, Korfiati A, Theofilatos K, Likothanassis S, Tsakalidis A, Mavroudi S. 2013. Where we stand, where we are moving: surveying computational techniques for identifying miRNA genes and uncovering their regulatory role. J. Biomed. Inform. 46, 563–573. (doi:10.1016/j.jbi.2013.02.002) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pasquinelli AE. 2012. MicroRNAs and their targets: recognition, regulation and an emerging reciprocal relationship. Nat. Rev. Genet. 13, 271–282. (doi:10.1038/nrg3162) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Krek A, et al. 2005. Combinatorial microRNA target predictions. Nat. Genet. 37, 495–500. (doi:10.1038/ng1536) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lewis BP, Shih IH, Jones-Rhoades MW, Bartel DP, Burge CB. 2003. Prediction of mammalian microRNA targets. Cell 115, 787–798. (doi:10.1016/S0092-8674(03)01018-3) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.John B, Enright AJ, Aravin A, Tuschl T, Sander C, Marks DS. 2004. Human microRNA targets. PLoS Biol. 2, e363 (doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0020363) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vejnar CE, Blum M, Zdobnov EM. 2013. miRmap web: comprehensive microRNA target prediction online. Nucleic Acids Res. 41, W165–W168. (doi:10.1093/nar/gkt430) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bandyopadhyay S, Mitra R. 2009. TargetMiner: microRNA target prediction with systematic identification of tissue-specific negative examples. Bioinformatics 25, 2625–2631. (doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/btp503) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kertesz M, Iovino N, Unnerstall U, Gaul U, Segal E. 2007. The role of site accessibility in microRNA target recognition. Nat. Genet. 39, 1278–1284. (doi:10.1038/ng2135) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liu H, Yue D, Chen Y, Gao SJ, Huang Y. 2010. Improving performance of mammalian microRNA target prediction. BMC Bioinf. 11, 476 (doi:10.1186/1471-2105-11-476) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Peterson SM, Thompson JA, Ufkin ML, Sathyanarayana P, Liaw L, Congdon CB. 2014. Common features of microRNA target prediction tools. Front. Genet. 5, 23 (doi:10.3389/fgene.2014.00023) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chen Y, Melton DW, Gelfond JA, McManus LM, Shireman PK. 2012. MiR-351 transiently increases during muscle regeneration and promotes progenitor cell proliferation and survival upon differentiation. Physiol. Genomics 44, 1042–1051. (doi:10.1152/physiolgenomics.00052.2012) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sun YM, Lin KY, Chen YQ. 2013. Diverse functions of miR-125 family in different cell contexts. J. Hematol. Oncol. 6, 6 (doi:10.1186/1756-8722-6-6) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gerrits A, Walasek MA, Olthof S, Weersing E, Ritsema M, Zwart E, van Os R, Bystrykh LV, de Haan G. 2012. Genetic screen identifies microRNA cluster 99b/let-7e/125a as a regulator of primitive hematopoietic cells. Blood 119, 377–387. (doi:10.1182/blood-2011-01-331686) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhong X, Li N, Liang S, Huang Q, Coukos G, Zhang L. 2010. Identification of microRNAs regulating reprogramming factor LIN28 in embryonic stem cells and cancer cells. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 41 961–41 971. (doi:10.1074/jbc.M110.169607) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Melton C, Judson RL, Blelloch R. 2010. Opposing microRNA families regulate self-renewal in mouse embryonic stem cells. Nature 463, 621–626. (doi:10.1038/nature08725) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Moreno DL, Salazar Z, Betancourt M, Casas E, Ducolomb Y, Gonzalez C, Bonilla E. 2014. Sebox plays an important role during the early mouse oogenesis in vitro. Zygote 22, 64–68. (doi:10.1017/S0967199412000342) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chen G, Tan R, Tao Q. 2015. Sebox regulates mesoderm formation in early amphibian embryos. Dev. Dyn. 244, 1415–1426. (doi:10.1002/dvdy.24323) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Moss EG, Lee RC, Ambros V. 1997. The cold shock domain protein LIN-28 controls developmental timing in C. elegans and is regulated by the lin-4 RNA. Cell 88, 637–646. (doi:10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81906-6) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Darr H, Benvenisty N. 2009. Genetic analysis of the role of the reprogramming gene LIN-28 in human embryonic stem cells. Stem Cells 27, 352–362. (doi:10.1634/stemcells.2008-0720) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rybak A, Fuchs H, Smirnova L, Brandt C, Pohl EE, Nitsch R, Wulczyn FG. 2008. A feedback loop comprising lin-28 and let-7 controls pre-let-7 maturation during neural stem-cell commitment. Nat. Cell Biol. 10, 987–993. (doi:10.1038/ncb1759) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yu J, et al. 2007. Induced pluripotent stem cell lines derived from human somatic cells. Science 318, 1917–1920. (doi:10.1126/science.1151526) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Alizadeh Z, Kageyama S, Aoki F. 2005. Degradation of maternal mRNA in mouse embryos: selective degradation of specific mRNAs after fertilization. Mol. Reprod. Dev. 72, 281–290. (doi:10.1002/mrd.20340) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schultz R. 2002. The molecular foundations of the maternal to zygotic transition in the preimplantation embryo. Hum. Reprod. Update 8, 323–331. (doi:10.1093/humupd/8.4.323) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Schultz RM. 1993. Regulation of zygotic gene activation in the mouse. Bioessays 15, 531–538. (doi:10.1002/bies.950150806) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Telford NA, Watson AJ, Schultz GA. 1990. Transition from maternal to embryonic control in early mammalian development: a comparison of several species. Mol. Reprod. Dev. 26, 90–100. (doi:10.1002/mrd.1080260113) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The relevant data supporting this article have been uploaded as part of the electronic supplementary material, figures S1 and S2 and tables S1 and S2.