Abstract

Mycobacterium abscessus is a pathogenic, rapidly growing mycobacterium responsible for pulmonary and cutaneous infections in immunocompetent patients and in patients with Mendelian disorders, such as cystic fibrosis (CF). Mycobacterium abscessus is known to transition from a smooth (S) morphotype with cell surface-associated glycopeptidolipids (GPL) to a rough (R) morphotype lacking GPL. Herein, we show that M. abscessus S and R variants are able to grow inside macrophages and are present in morphologically distinct phagosomes. The S forms are found mostly as single bacteria within phagosomes characterized by a tightly apposed phagosomal membrane and the presence of an electron translucent zone (ETZ) surrounding the bacilli. By contrast, infection with the R form leads to phagosomes often containing more than two bacilli, surrounded by a loose phagosomal membrane and lacking the ETZ. In contrast to the R variant, the S variant is capable of restricting intraphagosomal acidification and induces less apoptosis and autophagy. Importantly, the membrane of phagosomes enclosing the S forms showed signs of alteration, such as breaks or partial degradation. Although not frequently encountered, these events suggest that the S form is capable of provoking phagosome–cytosol communication. In conclusion, M. abscessus S exhibits traits inside macrophages that are reminiscent of slow-growing mycobacterial species.

Keywords: Mycobacterium abscessus, macrophages, phagosome, innate response, rapid-growing mycobacteria

1. Introduction

The Mycobacterium genus represents a complex group of more than 100 species, of which only a limited number are strict human or animal pathogens. Most of the non-pathogenic saprophytic mycobacteria belong to the rapid-growing mycobacteria (RGM) group, although some of them, including M. abscessus, M. chelonae and M. fortuitum, have recently been classified as true opportunistic pathogens [1]. Mycobacterium abscessus is now recognized as the major pulmonary pathogen within the RGM [2], with cystic fibrosis (CF) patients being particularly vulnerable to infection with this mycobacterium [3–7]. Mycobacterium abscessus is also regarded as a nosocomial infectious agent responsible for several epidemics due to clinical practices with contaminated materials [8,9]. Recent epidemiological studies and clinical case studies of CF patients infected with M. abscessus emphasized the persistence, sometimes for several decades, of M. abscessus within the host [10–12]. Finally, M. abscessus has been associated with the most direct impact on lung functions in CF patients when compared with the slow-growing mycobacterium (SGM) M. avium, and non-fermentative Gram-negative bacteria [13].

Like M. avium or M. smegmatis [14], M. abscessus displays two distinct morphotypes on solid agar media: a smooth (S) variant, non-cording but motile and biofilm-forming, and a rough (R) variant, cording but non-motile and non-biofilm-forming. The major difference between these two variants resides in the total loss of surface-associated glycopeptidolipids (GPL) in the R form [15]. Importantly, the R variant appears to arise only during the course of infection in the host organism, as evidenced by culture-positive sputum samples from patients [11] or experiments in B-cell-deficient mice [16]. In addition, R variants are frequently associated with severe infections as observed in CF patients infected with M. abscessus [11,12]. In the light of these findings, one may hypothesize that S and R variants differentially affect the phagocytic pathway.

One key difference between pathogenic and non-pathogenic mycobacteria is the capacity of pathogenic mycobacteria to survive and replicate within macrophages (Mϕ) and dendritic cells (DC) by arresting phagosome maturation and, hence, preventing fusion with lysosomes [17–23]. Mycobacterium fortuitum and M. smegmatis, a saprophytic RGM, are both unable to multiply inside Mϕ and are rapidly cleared from the infected cells [24,25]. In sharp contrast, M. abscessus not only survives, but also replicates inside Mϕ [26–28]. Histopathological studies performed on autopsy-derived lung tissue sections of patients who died from an infection with M. abscessus revealed the presence of granulomas with caseous lesions, a hallmark of persistent mycobacterial infection [29]. Such characteristic features have also recently been corroborated in zebrafish and mice infected with M. abscessus [16,30].

Based on these physiopathological features, M. abscessus can be regarded as a pseudotuberculous and virulent RGM with a potential dual pathogenic manifestation linked to the S to R transition. This prompted us to compare the phagocytic uptake and fate of both S and R variants within Mϕ with respect to growth and describe how these events affect the endomembrane compartment in which they reside. Our findings point to intracellular characteristics that are specific to M. abscessus S and which resemble those usually attributed to pathogenic SGM.

2. Results

2.1. Differential phagocytic uptake of Mycobacterium abscessus S and R variants

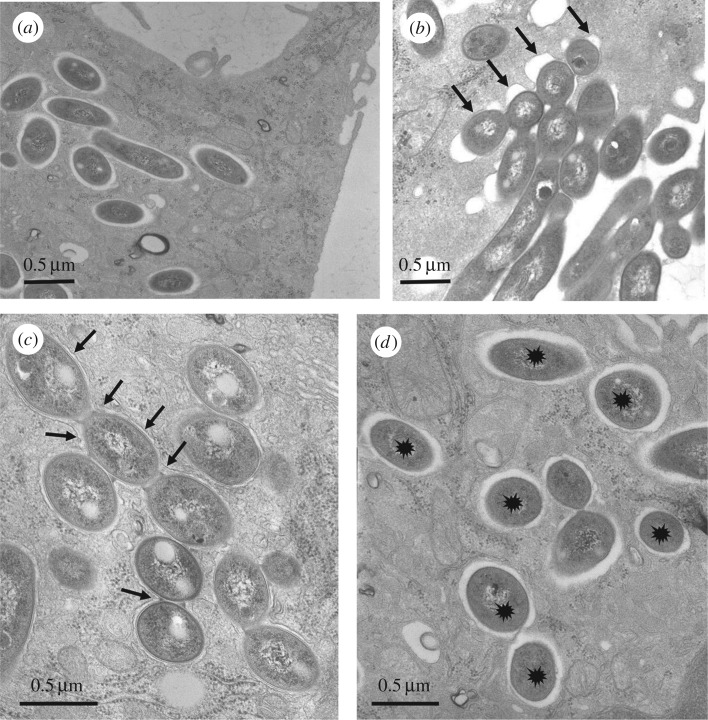

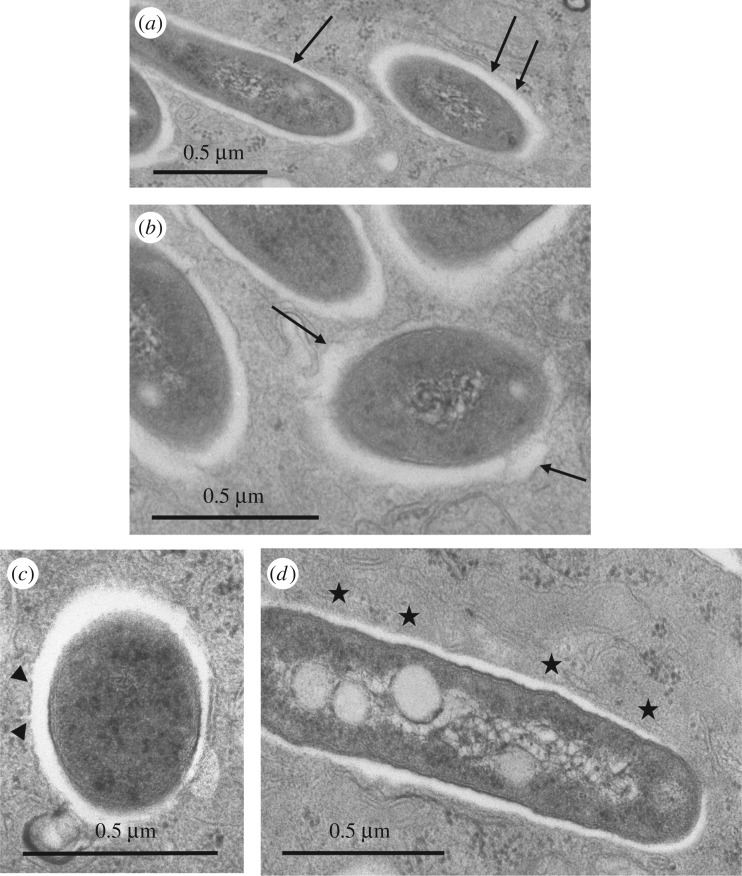

Bone-marrow-derived murine Mϕ (BMDM) were infected with the S or R variant of M. abscessus at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 1 in the absence of antibiotics (see Experimental procedures). After extensive washes to eliminate the residual extracellular bacteria, cells were fixed and processed for transmission electron microscopy (TEM) at selected time points thereafter (0–24 h p.i.). Examination of thin sections up to 24 h p.i. showed that the S variant was efficiently phagocytized. Bacteria in phagocytic cups or still binding to the cell surface were usually not found with M. abscessus S (figure 1a). Around 80% of the phagosomes harbouring M. abscessus S were loner phagosomes containing a single bacterium whereas 60% of the phagosomes harbouring M. abscessus R were social phagosomes with at least 2 bacilli (electronic supplementary material, figure S1). Most of the cell profiles displayed between 1 and 10 phagosomes at 24 h p.i. By contrast, the cell profiles displayed a low number of phagosomes following infection with the R variant. This could be linked to the highly aggregative nature of the R variant, despite extensive treatments involving several passages through a syringe needle. An important consequence of the R clumping/cording is that, in many instances, bacteria were gathered in long chains located at the close vicinity of the cell surface or in phagocytic cups. In the latter case, the tips of the pseudopods seemed to be unable to fuse together to give rise to nascent phagosomes (figure 1b). This observation indicates that a large amount of R forms might remain outside the cells. A few phagosomes, however, were found within Mϕ. They usually harboured large numbers of the M. abscessus R variant (figure 1c) as opposed to those harbouring the S variant, usually containing a single bacterium (figure 1d).

Figure 1.

Ultrastructural differences of the M. abscessus S- or R-containing phagosomes. Bone marrow-derived murine Mϕ (BMDM) were infected with either the S (a,d) or R (b,c) variants of M. abscessus for 3 h. At 24 h p.i., cells were fixed and processed for TEM. Thin sections were analysed for phagocytic uptake of each variant (a,b) and the morphological appearance of R (c) or S (d)-containing phagosomes. S forms (a) reside within phagosomes and none are found in phagocytic cups whereas most of the R forms (b) are still clustered in phagocytic cups (arrows) at 24 h p.i. (c) Once formed, the R-containing phagosomes usually comprise several bacteria (social phagosomes, indicated with arrows). (d) The S-containing phagosomes typically comprise a single bacterium (loner phagosomes, indicated with stars).

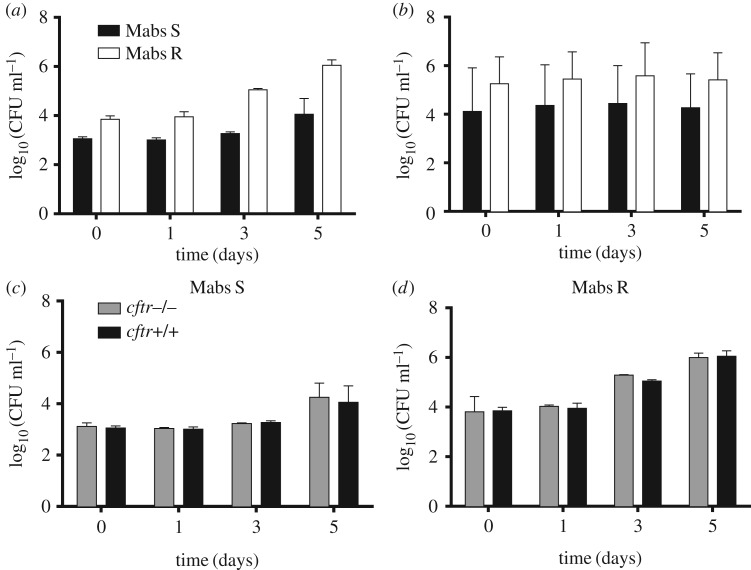

2.2. Mycobacterium abscessus multiplies similarly inside wild-type and cystic fibrosis conductance transmembrane regulator defective Mϕ

We next evaluated the intracellular growth of both variants in murine and human Mϕ by infecting cells at an MOI of 1 for 3 h (see Experimental procedures). That M. abscessus S and R survive in murine (figure 2a) and human (figure 2b) Mϕ is in line with previous reports [26,28]. However, it was not possible to directly compare the data obtained for the S and R variants because we systematically observed important differences in the mycobacterial uptake (up to a one log10 difference for the R variant). Determination of bacterial doubling time in Mϕ was 14.3 ± 0.8 h for the R variant and 19.4 ± 0.6 h for the S variant (figure 2a,b) compared with 6.0 ± 0.6 h and 5.8 ± 0.7 h for the in vitro grown R and S variants, respectively (electronic supplementary material, figure S2). These differences might be due to the intrinsic clumping of the M. abscessus R variant (figure 1b,c), despite extensive treatments to obtain homogeneous bacterial preparations [21,31]. Although extracellular growth cannot be totally excluded, this seems very unlikely because cells were systematically maintained under amikacin treatment during the duration of the experiment.

Figure 2.

Growth of M. abscessus S (Mabs S) and R (Mabs R) variants in different cells. Wild-type murine (a) or human (b) Mϕ were infected with S and R variants. Amikacin treatment was applied to avoid extracellular growth (see Experimental procedures). The number of CFU was determined at the indicated times p.i. (c,d) Wild-type and cftr−/− murine Mϕ were infected as mentioned above. Intracellular growth was similar in murine wild-type Mϕ and in murine Mϕ knock-out for cftr (cftr−/−). Error bars indicate the s.e.m., based on the results from three independent experiments.

Mycobacterium abscessus infection has been reported in patients with CF, a genetic disease linked to a functional defect of the CFTR (cystic fibrosis conductance transmembrane regulator) chloride channel [32]. We therefore evaluated whether mutations abolishing the expression level or function and/or the stability of CFTR may affect M. abscessus intracellular survival/growth. Comparison of the bacterial loads clearly indicated that intracellular growth of the S and R variants was similar in wild-type and cftr−/− BMDM (figure 2c,d). Comparable results were obtained following infection of murine Mϕ carrying the CFTRΔF508 mutation, representing the most frequent mutation encountered in CF patients and resulting in an abnormal CFTR protein (electronic supplementary material, figure S3). Overall, these observations not only indicate that M. abscessus can resist the bactericidal activity of murine/human Mϕ but also suggest that a functional CFTR is not required for sustaining intracellular growth of M. abscessus, at least within in vitro infected Mϕ.

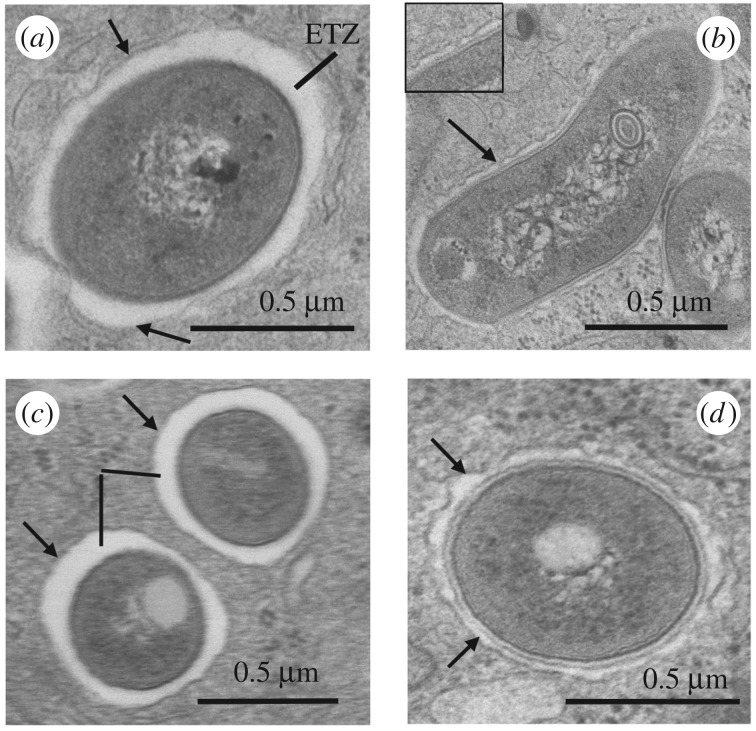

2.3. Distinct morphology of the intraphagosomal Mycobacterium abscessus S and R variants

The persistence phenotype of M. abscessus S and R in Mϕ prompted us to examine their ultrastructure within phagosomes. The most prominent feature was the appearance of the mycobacterial cell wall and its interaction with the phagosome membrane. In the case of the S strain, the outermost electron translucent zone (ETZ), which is a major part of the mycobacterial cell wall [33], was thick and apposed to the phagosome membrane all around (figure 3a). By contrast, the R form displayed a very thin ETZ (figure 3b). Although the phagosome membrane was no longer tightly apposed to the mycobacterial cell wall all around, it did seem to make contact with the mycobacterial cell wall at discrete sites (figure 3b, arrows and insert).

Figure 3.

Morphological appearance of the electron translucent layer (ETZ) of the cell wall of M. abscessus within phagosomes. Bone marrow-derived murine Mϕ (BMDM) were infected with various M. abscessus strains for 3 h. At selected time points p.i., cells were fixed and processed for TEM. The cell wall ultrastructure of the different strains was assessed on 100–200 different bacterial profiles. (a) S variant: the electron translucent outermost layer (ETZ) of the wall was thick and apposed to the smooth phagosome membrane (arrows) all around. (b) R variant: in the absence of GPL production, the ETZ was thin and the phagosome membrane had a wavy appearance (arrows); in some instances a close contact was observed at discrete sites (arrow and insert). (c) Mycobacterium abscessus ΔmmpL4b complemented strain: as for the S variant. (d) Mycobacterium abscessus ΔmmpL4b mutant: no GPL produced and thin ETZ as for the R variant.

It is well known that a major difference in the cell wall of the S and R variants of M. abscessus and M. bolettii resides in the lack of GPLs in the outermost cell wall layer of the R variant [34,35]. To confirm the dependence of ETZ formation on GPL production, BMDM were infected with a ΔmmpL4b mutant generated in an S background, a well-defined mutant that fails to produce and export GPL but exhibits a clumping/cording phenotype similar to the wild-type R strain [34]. BMDM were also infected with the corresponding complemented strain expressing mmpL4b under the control of the hsp60 promoter on the pNVB1 integrative plasmid [36]. Only the wild-type M. abscessus S and the ΔmmpL4b complemented strain, both producing GPLs, elaborated a thick ETZ (figure 3a,c), whereas the GPL-deficient ΔmmpL4b mutant, like the R variant, did not (figure 3b,d). Overall, these results indicate that M. abscessus elaborates an ETZ that depends on GPL production, which might contribute to the survival of the S variant within its host cell.

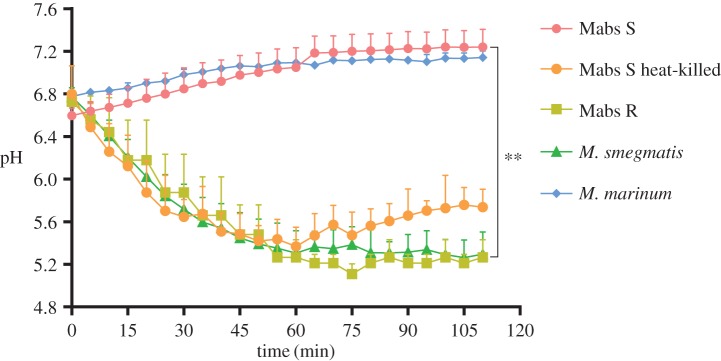

2.4. Mycobacterium abscessus S prevents phagosome maturation/acidification

Based on the intracellular survival of the two variants, it was of importance to understand by which mechanism(s) they resist the bactericidal response, known to clear most RGM infections. Live pathogenic mycobacteria, but not avirulent mycobacteria, are known to be retained in a mildly acidified environment [17,37–39]. The measurement of the phagosomal pH, following internalization, has been widely used as a physiologically relevant indicator of the maturation status of phagosomes [40]. We therefore analysed the pH of S- versus R-containing phagosomes in Mϕ using direct measurement of intraphagosomal pH by double fluorescent labelling. FITC (pH sensitive)-labelled M. abscessus S or R expressing mCherry (pH resistant) were used to infect Mϕ. The ratio between pH-sensitive and pH-resistant fluorescent stains was scored at specific time points. The pH was then calculated by comparing each ratio against a pH standard curve established with well-defined pH buffers [40]. Mycobacterium abscessus S- and M. marinum-containing phagosomes were not acidified in murine Mϕ, as reported for M. tuberculosis or M. avium infected cells [17,37] (figure 4). That heat-killed M. abscessus S failed to prevent phagosomal acidification suggests that this relies on an active process. Conversely, M. abscessus R-containing phagosomes were significantly more acidic than those containing the S variant at all time points (figure 4). A fast decline in phagosomal pH was previously reported to correlate with the rapid processing of phagosomes in late phagosomes or phagolysosomes [41]. This establishes that M. abscessus S-containing phagosomes are not processed into phagolysosomes following infection as shown earlier for phagosomes containing pathogenic mycobacteria [17,23,42–44].

Figure 4.

Absence of phagosomal acidification inside M. abscessus S-infected Mϕ. Human THP-1 Mϕ were infected with FITC-labelled mCherry-expressing M. abscessus S (Mabs S) and R (Mabs R), M. smegmatis, M. marinum and heat-killed M. abscessus S (Mabs S heat-killed). Fluorescent signals were measured sequentially at 485 nm (FITC) and 544 nm excitation wavelengths (mCherry) after a 15 mn incubation period at 37°C. The first time point on the x-axis (0 mn) was taken immediately after the 15 mn incubation. Subsequently, the pH at each time point was extrapolated from a standardized pH curve. The pH values were significantly different depending on whether phagosomes contained S or R variants. Results are representative of three independent experiments. (**p < 0.01).

2.5. The S variant may induce phagosome-cytosol communication

Both in vitro and in vivo studies demonstrated that pathogenic M. tuberculosis and M. marinum induce ruptures in the phagosome membrane and establish a phagosome-to-cytosol communication prior to the host cell death [45–48]. We evaluated whether this may also occur for M. abscessus. Conventional TEM approaches were first used to investigate whether the S form was able to promote an alteration of the phagosomal membrane, eventually followed by rupture of the membrane, which would allow the S form to gain access to the cytosol. Phagosomal rupture and phagosome-cytosol communication can be difficult to assess by conventional TEM because of tangential sections through part or all of the phagosome membrane. Care was therefore taken to examine only parts of the phagosome membrane where the plane of the section was perpendicular to the mycobacterial cell wall and hence also the phagosome membrane. Four situations were observed at 24 h p.i., as follows. (i) In the first and most frequent case, the phagosome membrane had a smooth appearance and it was tightly apposed to the ETZ (figure 5a, arrows). (ii) For part of the phagosomes, the membrane became wavy and it was no longer closely apposed to the ETZ (figure 5b, arrow). This could represent the first sign of an alteration of the phagosomal membrane. (iii) In rare instances, interruptions in the phagosome membrane were observed (figure 5c, arrowheads) that were not observed in other endocytic organelles (not shown). (iv) Finally, in a few cases, the phagosome membrane was no longer visible around part of the bacterium (figure 5d). Owing to the above-mentioned constraints, it was not possible by TEM to determine whether the entire bacterium had been freed in the cytosol (complete rupture of the phagosome membrane) or not (phagosome–cytosol communication only) and quantifications were not possible for the same reasons.

Figure 5.

Alteration of the membrane of phagosomes containing the S variant as assessed by TEM. Bone marrow-derived murine Mϕ were infected with M. abscessus S for 3 h. Phagosomes were examined for obvious signs of membrane alteration/destruction. (a) No alteration: the phagosome membrane is smooth (arrows) and closely apposed to the mycobacterial cell wall ETZ all around. (b) First sign of alteration: the phagosome membrane has become wavy and is no longer closely apposed to the bacterium all around (arrows). (c) The phagosome membrane displays breaks (arrowheads). (d) The phagosome membrane is no longer visible (stars).

Phagosome membrane rupture was subsequently assessed using the CCF-4 (cephalosporin core linking 7-hydroxycoumarin to fluorescein) substrate in a fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) assay, as previously described [47]. Differentiated THP-1 cells infected at an MOI of 1, either with M. abscessus S, M. smegmatis (negative control) or M. marinum, displayed at day 0 (3 h p.i.) a FRET 450 nm (blue)/535 nm (green) ratio of 1 (electronic supplementary material, figure S4), indicative of an absence of CCF-4 cleavage by the M. abscessus β-lactamase (BlaMab) [48]. Interestingly, and in contrast to M. smegmatis-infected Mϕ, M. abscessus S-infected cells displayed a FRET ratio of 1.5 at 24 h p.i., indicative of the fluorescence shift as a result of the disruption of CCF-4 by BlaMab in the cytosolic compartment (electronic supplementary material, figure S4). The FRET assay, performed in THP-1 cells, relies either on phagosome–cytosol interplay enabling diffusion of BlaMab into the cytosol and/or on the presence of free intra-cytosolic organisms. These results corroborate the TEM observations in murine Mϕ and suggest that the S variant, but not the R form, might establish a successful phagosome–cytosol communication.

2.6. Mycobacterium abscessus S fails to trigger apoptosis and bacterial autophagy

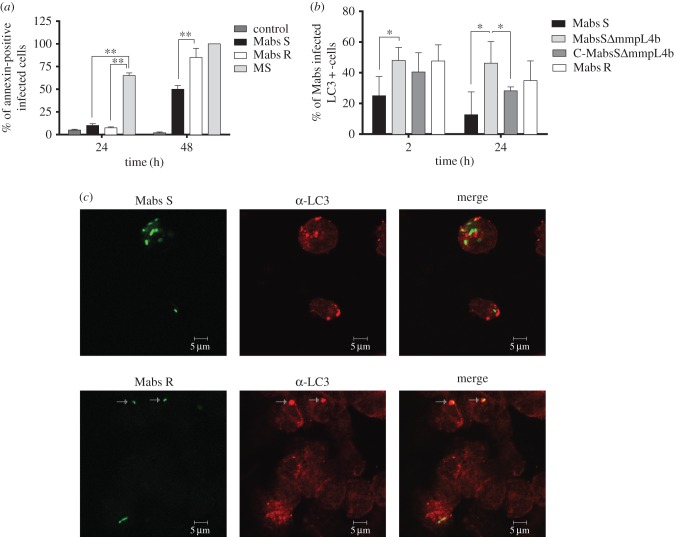

The phagosome–cytosol interplay may substantially impact on apoptosis and autophagy in the infected host phagocytes [49], both these cellular responses being efficient in controlling the intracellular growth of the RGM, M. smegmatis and M. fortuitum [24,50,51]. Here, we evaluated the extent of apoptosis following infection of THP-1 Mϕ with M. abscessus S, following annexin-V labelling. M. smegmatis, known as a potent apoptosis-inducing species [24,25], was also included as a positive control. Our results confirm the previously described pro-apoptotic activity of M. smegmatis [25] with nearly 80% of infected cells annexin-V-positive at 24 h p.i. (figure 6a). Compared to M. smegmatis, M. abscessus S- and R-infected Mϕ were only slightly apoptotic, with at most 10% of infected cells annexin-V-positive at 24 h (figure 6a). However, a significant difference in labelling was observed between the S and R variants at 48 h p.i. (figure 6a) with 50% and 90% of annexin-V-positive infected Mϕ, respectively. Overall, these results indicate that M. abscessus S is less pro-apoptotic than M. abscessus R, in agreement with previous observations in zebrafish [30].

Figure 6.

Mycobacterium abscessus-induced apoptosis and autophagy in wild-type Mϕ. (a) Analysis of apoptosis: THP-1 Mϕ were infected with M. abscessus S (Mabs S), M. abscessus R (Mabs R) or M. smegmatis (MS). The percentage of apoptotic cells was determined at 24 h p.i. using annexin-V-FITC conjugates (Abcam, USA) and propidium iodide to stain the dead cells. Fluorescent signals (mCherry from mycobacteria, FITC from the annexin-V and absence of propidium iodide) were analysed by flow cytometry. A significant increase in the percentage of apoptotic cells was associated with M. smegmatis-infected cells when compared with Mϕ infected with M. abscessus S or R. However, the R variant was significantly more pro-apoptotic than the S variant at 48 h. Error bars indicate the s.e.m. based on the results of two independent experiments (**p < 0.01). (b,c) Comparative behaviour of M. abscessus S and R variants towards autophagy. (b) Percentage of colocalization of M. abscessus S (Mabs S), S ΔmmpL4b mutant (MabsS ΔmmpL4b), ΔmmpL4b complemented (C-MabsS ΔmmpL4b) and R (Mabs R)-infected cells with LC3 at 2 and 24 h p.i. determined after immunofluorescence analyses. Error bars indicate the s.e.m. based on the results from four independent experiments (*p < 0.05). (c) Confocal immunofluorescence images of fixed THP-1 cells infected with Alexa-488-labelled M. abscessus variant S (Mabs S) or variant R (Mabs R) (green) (2 h p.i.) and immuno-stained for endogenous LC3 (red). Scale bars, 5 µm.

Autophagy was next assessed after infection of THP-1 Mϕ with the Alexa488-labelled S variant and using anti-LC3-antibodies to specifically immunolabel autophagosome membranes. M. abscessus S did not co-localize with the LC3 marker, with 10% at 24 h p.i. of autophagosomes potentially containing the S variant (figure 6b,c). Comparatively, the R variant induced more autophagy than the S variant (figure 6b,c), as evidenced by the increased percentage of M. abscessus-LC3-positive infected cells (figure 6b) and confocal microscopy (figure 6c). In addition, the results obtained with the GPL-deficient ΔmmpL4b S mutant were comparable to those of M. abscessus R (figure 6b), confirming the importance of the surface-exposed GPL in the inhibition of autophagy of the S variant.

3. Discussion

The source and the mechanism responsible for pulmonary contamination of CF patients with M. abscessus remain unclear [52]. It appears, therefore, critical to understand how M. abscessus resists the Mϕ bactericidal activity, usually highly efficient against other RGM, such as M. smegmatis and M. fortuitum [24,25]. The S variant, capable of forming biofilm-like structures, is most likely to be the infecting form. GPL present at the surface of M. abscessus S have been shown to prevent TLR2 signalling in respiratory epithelial cells [53], possibly allowing lung colonization and subsequent survival in a silent and permissive niche, as shown for M. tuberculosis and M. marinum [20,45]. Herein, we confirmed that M. abscessus S survives in Mϕ, an observation consistent with previous studies [26–28], and demonstrated, for the first time, that replication of M. abscessus in Mϕ was not affected by functional CFTR defects. This provides evidence that such a modification is not responsible for the peculiar susceptibility of CF patients to M. abscessus infections, at least at the intracellular level. Noteworthily, Griffith et al. demonstrated that one third of the pulmonary infections due to M. abscessus can occur in the absence of a pre-existing lung pathology [2], emphasizing the intrinsic ability of M. abscessus to resist the bactericidal activity of Mϕ, a feature historically considered to be an exclusive attribute of SGM. In this context, Oberley-Deegan et al. proposed that M. abscessus could interfere with phagosome processing into phagolysosomes through the manipulation of host signal transduction pathways [27,54].

After phagocytosis by Mϕ, the S variant is found as a single bacterium in loner phagosomes whose membrane is closely apposed all around the outer surface of the mycobacterial cell wall. The S variant was also found to reside in slightly acidified non-mature phagosomes that are unable to fuse with lysosomes [42,43]. The retention of Rab5 at the membrane of M. abscessus-containing phagosomes in epithelial cells [54] is consistent with these findings. In addition, M. abscessus S was also found to be a poor apoptosis- and autophagy-inducing strain. These results were unexpected as all the RGM studied so far, particularly M. smegmatis and M. fortuitum, reside in phagolysosomes and are subsequently eliminated by the Mϕ. Moreover, RGM are known to induce the formation of autophagic vacuoles and cell apoptosis, both strategies considered important host cell defence mechanisms [55–57].

By contrast, the R form follows a rather different pathway. First, during the early infection stage, it presents a strong tendency to form chains or large clumps that usually remain in phagocytic cups instead of being internalized. As a result, cells contain less phagosomes but the latter contain generally multiple bacteria. It is well known that phagosomes containing several bacteria are systematically processed into phagolysosomes [17,23,41–44]. As expected, such phagosomes were rapidly acidified. Yet the intraphagosomal R variants did not appear to undergo degradation, at least during the first 24 h p.i., as assessed by EM observation of thin sections. The absence of degradation in phagolysosomes has already been observed for other mycobacteria [42]. Furthermore, the presence of the R variant within Mϕ induced the formation of autophagic vacuoles and cells became apoptotic. All these results point towards a typical RGM-like behaviour for the R variant [24,25]. It is noteworthy that the potent apoptosis-induced cell death activity may help the R variant to reach the extracellular environment ([30] and our study) where it can form cords. However, another unexpected result of this study was that the R variant, as opposed to other RGM, was able to replicate within Mϕ, an intriguing phenotype that may be due to the extensive clumping of the R variant within phagocytic cups or phagosomes. Moreover, re-invasion of extracellular bacteria that are released from the apoptotic Mϕ cannot be fully excluded.

The question that arises from this work is the following: why do the R and S variants follow such different phagosome trafficking pathways? Based on EM analyses of murine Mϕ infected with either M. avium, or M. tuberculosis, de Chastellier and colleagues showed evidence that, independent of the molecular mechanisms involved in the blocking of phagosome maturation of a mycobacterium-containing phagosome, the establishment and maintenance of a close apposition of the phagosome membrane with the entire mycobacterial surface all around represented a necessary requirement for prevention of phagosome maturation [39,42]. Interestingly, such a close interaction was observed in the case of S variant-containing phagosomes but not for those containing the R form. The establishment and maintenance of a long-lasting close apposition most probably involves the interaction between specific proteins and/or lipids of the phagosome membrane with specific components of the mycobacterial cell wall surface. Among these, ManLAM of M. tuberculosis is considered to be responsible for the prevention of phagosome maturation [58]. Recent studies also demonstrated that cyclopropane rings in α-mycolic acids are critical determinants for the phagosome maturation block [59]. The masking role of phenolic glycolipid (PGL), a major glycolipid found in SGM, including M. marinum and some M. tuberculosis clinical isolates, for recruiting permissive Mϕ has also been unravelled [60]. By analogy, GPL can be regarded as the PGL-matching glycolipid of atypical mycobacteria as it displays similar functional roles, such as limiting mycobacterial uptake [61] and masking the TLR2 ligands, thereby accounting for different inflammation-elicited responses towards S and R variants [36,62]. It could thus be argued that the S to R transition, involving loss of function mutations in the GPL biosynthetic or export machinery in M. abscessus, conditions the inflammatory response of the infected host.

The EM approaches used in this work provide compelling evidence on the role of GPL in the differential processing of phagosomes containing the S and R variants. It is well known that GPL is a major constituent of the mycobacterial cell wall ETZ [63,64]. While the ETZ was very thick in the case of the S variant, it was thinned out in the case of the R variant and also in the case of the ΔmmpL4b mutant that is unable to transport/assemble GPL at the bacterial surface. With the S variant being closely apposed to the phagosome membrane all around, and the R variant making contact with the phagosome membrane only at discrete sites, it is tempting to speculate that GPL is a major actor for establishing and maintaining the close apposition required for prevention of phagosome maturation. In fact, the M. avium complex GPL can delay phagosome–lysosome fusion following its ligation to the mannose receptor [65,66].

Interestingly, among M. abscessus, M. smegmatis and M. chelonae, all expressing cell surface GPL, as evidenced by high conservation of their respective gpl locus [67], only M. abscessus and M. chelonae have retained the ability to survive inside Mϕ [68]. Mycobacterium smegmatis mc2155 strain, which derives originally from the ATCC 607 strain [69], expresses less triglycosylated GPL than M. abscessus or M. chelonae [67]. That the level of GPL production can be enhanced in M. smegmatis mc2155 when overexpressing the whole mbtH-mps1-mps2-gap operon from M. abscessus [70] reflects quantitative differences in GPL production between these species, despite the presence of a similar gpl locus. Subtle differences at the cell surface in relation to GPL production may thus considerably interfere and modify the fate of mycobacteria within Mϕ.

Another important aspect concerns the possibility for M. abscessus to alter the phagosomal membrane and free itself from the phagosome in which it resides. A qualitative EM analysis of thin sections of at least 150 phagosomes showed that the membrane of S- but not R-containing phagosomes may present alterations. The membrane became loose and, in rare instances, showed breaks or partial lysis. Importantly, neighbouring organelles showed no signs of membrane alteration, thus ruling out eventual artefacts due to the processing of the EM samples. Unfortunately, we were neither able to quantify such events nor to conclusively determine whether the entire bacterium could be released into the cytosolic compartment.

The mycobacterial constituents and molecular mechanisms involved in the alteration or rupture of the M. abscessus S-containing phagosome membrane remain unknown. It has been reported that M. abscessus is not equipped with the ESX-1 apparatus, which mediates establishment of cytosol contact for slow-growing pathogenic mycobacteria such as M. tuberculosis [46,47,55,71,72], M. marinum [45] and M. kansasii [73]. Ongoing work dedicated to study a panel of defined transposon mutants [74] will hopefully allow us to identify the putative ESX-1-independent membrane-damaging constituents of the S strain, which are obviously mediated by an ESX-1-independent mechanism.

To summarize, it seems to be rather difficult to strictly compare the behaviours of S and R morphotypes. S and R variants can be regarded as two representatives of the same isolate, which coexist and/or evolve differently in response to host immunity, resulting in different fates for both the bacteria and the host. In conclusion, we provide compelling evidence that, at the cellular level, M. abscessus S imitates the phenotypic traits of pathogenic SGM and that the loss of cell wall associated lipids, namely GPL, can result in the acquisition of an RGM-like intracellular behaviour with a peculiar extracellular state characterized by a very high replication capacity [30]. CF patients are mainly infected with extracellular pathogens, such as Pseudomonas and Staphylococcus, with high growth rates in the bronchial lumen. By analogy, M. abscessus R can be regarded as the aggressive form in these patients. The capacity of M. abscessus to transition from an S intra-Mϕ-resistant form to an R extracellular form probably increases its capacity to adapt and survive in the changing environments. This is corroborated by recent comparative genomic studies indicating that M. abscessus evolves rapidly and should be monitored closely for the acquisition of more pathogenic traits. Mycobacterium abscessus genomes are very plastic, with many recently introduced insertion sequences such as prophages and novel genes, and have an open pan-genome [75,76], suggesting that they might continue to acquire new genetic material, for the adaptation to divergent environmental conditions.

4. Experimental procedures

4.1. Bacterial culture conditions

Isogenic pairs of S and R GFP- or mCherry-expressing M. abscessus CIP 104536T were used throughout this study. An mmpL4b KO (ΔmmpL4b) mutant displaying an R morphotype [34] and its complemented counterpart, which stably expresses MmpL4b under the control of the hsp60 promoter, were also used. Mycobacteria were grown aerobically in Middlebrook 7H9 medium supplemented with 0.05% Tween 80 and 10% OADC (oleic acid, dextrose, catalase and bovine albumin) (Becton Dickinson, Le Pont-de-Claix, France) at 37°C. GFP-expressing strains were propagated in medium containing 500 µg ml−1 hygromycin B (Roche Diagnostics, Meylan, France). MCherry-expressing mycobacterial strains were grown in the presence of 250 µg ml−1 kanamycin (Sigma, USA).

4.2. Macrophage culture conditions

Animal experiments were performed according to institutional and national ethical guidelines (Agreement no 92-033-01). ΔF508 FVB mice, supplemented with movicol (Norgine, The Netherlands), and their wild-type FVB littermates [77,78] were from INRA (Jouy en Josas, France). The BMDM Mϕ, human monocyte- derived Mϕ (HMDM) and THP-1 Mϕ were prepared as previously described [31,79]. THP-1 Mϕ were cultured in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% FBS and differentiated for 24 h with 20 ng ml−1 PMA prior to infection.

4.3. Mϕ infections and intracellular growth measurement

Mycobacteria, grown aerobically at 37°C up to mid-log phase, were harvested by centrifugation and suspended in a phosphate buffer saline (PBS) solution (Sigma, USA). The bacterial clumps were disrupted by 20–30 passages through 26.5G insulin syringe and the bacterial suspension was then used to infect Mϕ (5 × 104 to 105) at an MOI between 1 and 10 mycobacteria per Mϕ in order to avoid rapid cell lysis, and incubated for 3 h at 37°C. After infection, cells were washed thoroughly with PBS (three to four times, except when explicitly stated differently) to eliminate extracellular bacteria and re-fed with complete medium containing amikacin at 250 µg ml−1 (except for EM experiments) for a further 1 h incubation at 37°C. This step was essential for killing the remaining extracellular mycobacteria, particularly the R variant that presents a sticky and clumpy phenotype (see Results). The medium containing amikacin was then discarded and cells were washed again three times. Infected cells were subsequently incubated in the presence of amikacin at 50 µg ml−1 at 37°C (except for EM experiments). CFU counts were performed at day 0 (or 4 h p.i. after the last wash), day 1, day 3 and day 5, by lysing the cells with cold distillated water, and plating 10-fold serial dilutions on LB plates (Sigma, USA). Colony enumeration was performed after 5–7 days of incubation at 37°C.

4.4. Analysis of phagosomal acidification

In total, 24-well plates of fully confluent monolayers of Mϕ were infected with FITC-labelled M. abscessus (expressing mCherry) at an MOI between 1 and 10, centrifuged at low speed for 90 s and incubated at 37°C for 15 min prior to fluorescence measurements. Fluorescent signals were then measured by sequentially exciting at 485 nm (FITC) and 544 nm (mCherry) using a Fluoroskan Ascent FL spectrofluorometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, France). A standard pH curve was established to correlate the fluorescence signal with the pH as described [40].

4.5. Apoptotis and autophagy determination

The apoptosis assay was performed as described previously [80]. Mϕ were infected with M. abscessus and the percentage of apoptotic cells was determined using annexin-V–FITC conjugates (Abcam, USA) and propidium iodide staining of dead cells. Cells were infected with mCherry-expressing mycobacteria at an MOI of 10. For flow cytometry analysis, 10 000 events were collected for each condition and the percentages of annexin-V-positive mCherry-positive and propidium iodide-negative cells were determined, in order to count infected cells that became apoptotic.

For autophagy, mycobacteria were labelled with 50 µg ml−1 Alexa-488-succinimidyl ester in PBS for 45 min at room temperature (RT) and used to infect THP-1 Mϕ at an MOI of 1–10. Cells were spun down for 5 min at 800 rpm to synchronize phagocytosis, incubated for 30 min at 37°C, washed several times to remove extracellular bacteria and then incubated for 15 min, 2 h or 24 h at 37°C. Subsequently, cells were fixed with 2% paraformaldehyde (Delta microscopy) for 10 min, permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X100/PBS for 5 min and blocked with 4% BSA (Euromedex, France), 2% goat serum (Sigma, USA) in PBS for 1 h. Cells were incubated with rabbit anti-LC3 (MBL, France) overnight in blocking buffer, washed and then incubated for 3 h with secondary antibody coupled to Alexa-568. Observation was done using a Zeiss LSM 510 Inv confocal microscope and images were processed with ImageJ software. A total of 100 bacteria were counted per time point.

4.6. Processing for electron microscopy

Cells were fixed for 1 h at RT with 2.5% glutaraldehyde (Sigma, St Louis, MI, USA) in 0.1 M cacodylate buffer, pH 7.2, containing 0.1 M sucrose, 5 mM CaCl2 and 5 mM MgCl2. After two successive 15 min washes with the same buffer, cells were post-fixed for 1 h at RT with 1% osmium tetroxide (Electron Microscopy Sciences, distributed by Euromedex, Mundolsheim, France) in the same buffer devoid of sucrose. Cells were washed with buffer, scraped off the dishes with a rubber policeman, concentrated in 2% agarose in the same buffer, and treated for 1 h in 1% uranyl acetate in 30% methanol. Samples were dehydrated in a graded series of ethanol and embedded in Spurr resin. Thin sections were stained with 1% uranyl acetate in distilled water and then with lead citrate.

4.7. Fluorescence resonance energy transfer

We performed a modified assay that was previously used to investigate the breakdown of the endocytic vacuoles by Gram-negative bacteria using a chemical probe that is trapped within the host cytoplasm and detectable by fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) measurements, as recently described [47]. Briefly, at successive stages of the time course measurements, a mix containing 50 µM CCF-4 substrate (Life Technologies, Saint Aubin, France) in EM medium (120 mM NaCl, 7 mM KCl, 1.8 mM CaCl2, 0.8 mM MgCl2, 5 mM glucose and 25 mM Hepes at pH 7.3) containing 2.5 µM probenicid was added to the infected THP-1 cells for 2 h at RT in the dark. Cells were then washed with PBS containing 2.5 µM probenicid before fixing with PFA 4% for 30 min at RT in the dark. Cells were washed directly before performing fluorescence imaging. Measurement of the ratio of 450 nm (blue)/535 nm (green) fluorescence allowed determining whether the bacteria established a phagosome–cytosol communication. Reading was performed by a fluorescence microscope with AutoPlay (Nikon) for the automatic acquisition of at least 50 cells per well and image analyses were performed using a dedicated algorithm using Metamorph software [47]. The experiment was repeated twice with similar results.

4.8. Statistical analyses

Fisher's exact test and the Student's t-test were used for all comparisons (GraphPad Prism version 6.0d; GraphPad Software, Inc). A p-value less than 0.05 was considered significant (n.s. = non-significant, *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001; ****p < 0.0001).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We greatly acknowledge Dr S. Canaan for critical reading of the manuscript and help in formatting the TIFF files of EM figures and V. Dubois for formatting the figures. We wish to acknowledge TRI-Genotoul Imaging facility (Toulouse, France). The authors wish to thank Jean Paul Chauvin, head of this EM facility, for expert technical assistance with the electron microscopes and the digital camera.

Authors' contributions

A.-L.R., A.V., A.B., R.S., A.B., L.L., T.D., L.M., M.R. and F.G.-M. carried out the microbiology, bacterial–cells interaction, confocal microscopy, electronic microscopy (A.V. with C.d.C.). J.-L.H., L.K., C.d.C., I.V., R.B., L.M. and J.-L.G. participated in the design of the study and drafted the manuscript; A.-L.R., A.B., R.S., L.M., I.V., R.B. and J.-L.H. carried out the statistical analyses; J.-L.H., L.K., R.B., C.d.C. and I.V. conceived the study, designed the study, coordinated the study and drafted the manuscript. All authors gave final approval for publication.

Competing interests

We have no competing interests.

Funding

This work was supported by the French Cystic Fibrosis Patients Association ‘Vaincre la Mucoviscidose’ (IC0709; IC0808; IC1010) and the French Research National Agency (ANR program DIMIVYR (ANR-13-BSV3-0007-01). R.B. acknowledges support by the Fondation Pour La Recherche Médicale FRM (DEQ20130326471). L.K. acknowledges the FRM (DEQ20150331719). I.V. was supported by a European Community FP7 Marie Curie Career Integration Grant Europe (autophagtuberculosis 293416), University of Toulouse and Vaincre la Mucoviscidose. A.V. would like to thank Infectiopôle Sud for financial support. C.d.C. and A.V. performed the EM observations and analyses in the PiCSL EM core facility (Institut de Biologie du Développement/Aix Marseille Université, Marseille), a member of the France-BioImaging French research infrastructure.

References

- 1.Guglielmetti L, et al. 2015. Human infections due to nontuberculous mycobacteria: the infectious diseases and clinical microbiology specialists’ point of view. Future Microbiol. 10, 1467–1483. (doi:10.1111/j.1462-5822.2005.00675.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Griffith DE, Girard WM, Wallace RJJ. 1993. Clinical features of pulmonary disease caused by rapidly growing mycobacteria. An analysis of 154 patients. Am. Rev. Respir. Dis. 147, 1271–1278. (doi:10.1164/ajrccm/147.5.1271) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Olivier KN, et al. 2003. Nontuberculous mycobacteria. I: Multicenter prevalence study in cystic fibrosis. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 167, 828–834. (doi:10.1164/rccm.200207-678OC) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Levy I, et al. 2008. Multicenter cross-sectional study of nontuberculous mycobacterial infections among cystic fibrosis patients, Israel. Emerg. Infect Dis. 14, 378–384. (doi:10.3201/eid1403.061405) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Roux A-L, et al. 2009. Multicenter study of prevalence of nontuberculous mycobacteria in patients with cystic fibrosis in france. J. Clin. Microbiol. 47, 4124–4128. (doi:10.1128/JCM.01257-09) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Esther CRJ, Esserman DA, Gilligan P, Kerr A, Noone PG. 2010. Chronic Mycobacterium abscessus infection and lung function decline in cystic fibrosis. J. Cyst Fibros. 9, 117–123. (doi:10.1016/j.jcf.2009.12.001) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Qvist T, et al. 2015. Epidemiology of nontuberculous mycobacteria among patients with cystic fibrosis in Scandinavia. J. Cyst Fibros. 14, 46–52. (doi:10.1016/j.jcf.2014.08.002) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Duarte RS, et al. 2009. Epidemic of postsurgical infections caused by Mycobacterium massiliense. J. Clin. Microbiol. 47, 2149–2155. (doi:10.1128/JCM.00027-09) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Leão SC, et al. 2010. Epidemic of surgical-site infections by a single clone of rapidly growing mycobacteria in Brazil. Future Microbiol. 5, 971–980. (doi:10.2217/fmb.10.49) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cullen AR, Cannon CL, Mark EJ, Colin AA. 2000. Mycobacterium abscessus infection in cystic fibrosis. Colonization or infection? Am. J. Respir. Crit Care Med. 161, 641–645. (doi:10.1164/ajrccm.161.2.9903062) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jonsson BE, Gilljam M, Lindblad A, Ridell M, Wold AE, Welinder-Olsson C. 2007. Molecular epidemiology of Mycobacterium abscessus, with focus on cystic fibrosis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 45, 1497–1504. (doi:10.1128/JCM.02592-06) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Catherinot E, et al. 2009. Acute respiratory failure involving an R variant of Mycobacterium abscessus. J. Clin. Microbiol. 47, 271–274. (doi:10.1128/JCM.01478-08) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Qvist T, et al. 2016. Comparing the harmful effects of nontuberculous mycobacteria and Gram negative bacteria on lung function in patients with cystic fibrosis. J. Cyst Fibros. 15, 380–385. (doi:10.1016/j.jcf.2015.09.007) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chatterjee D, Khoo KH. 2001. The surface glycopeptidolipids of mycobacteria: structures and biological properties. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 58, 2018–2042. (doi:10.1420-682X/01/142018-25) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Howard ST, Rhoades E, Recht J, Pang X, Alsup A, Kolter R, Lyons CR, Byrd TF. 2006. Spontaneous reversion of Mycobacterium abscessus from a smooth to a rough morphotype is associated with reduced expression of glycopeptidolipid and reacquisition of an invasive phenotype. Microbiology 152, 1581–1590. (doi:10.1099/mic.0.28625-0) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rottman M, Catherinot E, Hochedez P, Emile J-F, Casanova J-L, Gaillard J-L, Soudais C. 2007. Importance of T cells, gamma interferon, and tumor necrosis factor in immune control of the rapid grower Mycobacterium abscessus in C57BL/6 mice. Infect Immun. 75, 5898–5907. (doi:10.1128/IAI.00014-07) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.de Chastellier C, Lang T, Thilo L.. 1995. Phagocytic processing of the macrophage endoparasite, Mycobacterium avium, in comparison to phagosomes which contain Bacillus subtilis or latex beads. Eur. J. Cell Biol. 68, 167–182. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sturgill-Koszycki S, Schaible UE, Russell DG. 1996. Mycobacterium-containing phagosomes are accessible to early endosomes and reflect a transitional state in normal phagosome biogenesis. EMBO J. 15, 6960–6968. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Via LE, Deretic D, Ulmer RJ, Hibler NS, Huber LA, Deretic V. 1997. Arrest of mycobacterial phagosome maturation is caused by a block in vesicle fusion between stages controlled by rab5 and rab7. J. Biol. Chem. 272, 13 326–13 331. (doi:10.1074/jbc.272.20.13326) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Russell DG. 2001. Mycobacterium tuberculosis: here today, and here tomorrow. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2, 569–577. (doi:10.1038/35085034) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tailleux L. et al. . 2003. Constrained intracellular survival of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in human dendritic cells. J. Immunol. 170, 1939–1948. (doi:10.4049/jimmunol.170.4.1939) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vergne I, Chua J, Singh SB, Deretic V. 2004. Cell biology of Mycobacterium tuberculosis phagosome. Annu. Rev. Cell. Dev. Biol. 20, 367–394. (doi:10.1146/annurev.cellbio.20.010403.114015) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Clemens DL, Horwitz MA. 1995. Characterization of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis phagosome and evidence that phagosomal maturation is inhibited. J. Exp. Med. 181, 257–270. (doi:10.10.1084/jem.181.1.257) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Anes E, et al. 2006. Dynamic life and death interactions between Mycobacterium smegmatis and J774 macrophages. Cell Microbiol. 8, 939–960. (doi:10.1111/j.1462-5822.2005.00675.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bohsali A, Abdalla H, Velmurugan K, Briken V. 2010. The non-pathogenic mycobacteria M. smegmatis and M. fortuitum induce rapid host cell apoptosis via a caspase-3 and TNF dependent pathway. BMC Microbiol. 10, 237 (doi:10.1186/1471-2180-10-237) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Byrd TF, Lyons CR. 1999. Preliminary characterization of a Mycobacterium abscessus mutant in human and murine models of infection. Infect Immun. 67, 4700–4707. (doi:10.0019-9567/99) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Oberley-Deegan RE, Lee YM, Morey GE, Cook DM, Chan ED, Crapo JD. 2009. The antioxidant mimetic, MnTE-2-PyP, reduces intracellular growth of Mycobacterium abscessus. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 41, 170–178. (doi:10.1165/rcmb.2008-0138OC) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nessar R, Reyrat J-M, Davidson LB, Byrd TF. 2011. Deletion of the mmpL4b gene in the Mycobacterium abscessus glycopeptidolipid biosynthetic pathway results in loss of surface colonization capability, but enhanced ability to replicate in human macrophages and stimulate their innate immune response. Microbiology 157, 1187–1195. (doi:10.1099/mic.0.046557-0) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tomashefski JFJ, Stern RC, Demko CA, Doershuk CF. 1996. Nontuberculous mycobacteria in cystic fibrosis. An autopsy study. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 154, 523–528. (doi:10.1164/ajrccm.154.2.8756832) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bernut A, Herrmann J-L, Kissa K, Dubremetz J-F, Gaillard J-L, Lutfalla G, Kremer L. 2014. Mycobacterium abscessus cording prevents phagocytosis and promotes abscess formation. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 111, E943–E952. (doi:10.1073/pnas.1321390111) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Catherinot E, et al. 2007. Hypervirulence of a rough variant of the Mycobacterium abscessus type strain. Infect Immun. 75, 1055–1058. (doi:10.1128/IAI.00835-06) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Riordan JR, et al. 1989. Identification of the cystic fibrosis gene: cloning and characterization of complementary DNA. Science 245, 1066–1073. (doi:10.1126/science.2475911) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Draper P. 1974. The mycoside capsule of Mycobacterium avium 357. J. Gen. Microbiol. 83, 431–433. (doi:10.1099/00221287-83-2-431) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Medjahed H, Reyrat J-M. 2009. Construction of Mycobacterium abscessus defined glycopeptidolipid mutants: comparison of genetic tools. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 75, 1331–1338. (doi:10.1128/AEM.01914-08) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bernut A, et al. 2016. Insights into the smooth-to-rough transitioning in Mycobacterium bolletii unravels a functional Tyr residue conserved in all mycobacterial MmpL family members. Mol. Microbiol. 99, 866–883. (doi:10.1111/mmi.13283) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Roux A-L, et al. 2011. Overexpression of proinflammatory TLR-2-signalling lipoproteins in hypervirulent mycobacterial variants. Cell Microbiol. 13, 692–704. (doi:10.1111/j.1462-5822.2010.01565.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sturgill-Koszycki S, et al. 1994. Lack of acidification in Mycobacterium phagosomes produced by exclusion of the vesicular proton-ATPase. Science 263, 678–681. (doi:10.1126/science.8303277) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mwandumba HC, Russell DG, Nyirenda MH, Anderson J, White SA, Molyneux ME, Squire. 2004. Mycobacterium tuberculosis resides in nonacidified vacuoles in endocytically competent alveolar macrophages from patients with tuberculosis and HIV infection. J. Immunol. 172, 4592–4598. (doi:10.4049/jimmunol.172.7.4592) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.de Chastellier C, Forquet F, Gordon A, Thilo L. 2009. Mycobacterium requires an all-around closely apposing phagosome membrane to maintain the maturation block and this apposition is re-established when it rescues itself from phagolysosomes. Cell Microbiol. 11, 1190–1207. (doi:10.1111/j.1462-5822.2009.01324.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pethe K, Swenson DL, Alonso S, Anderson J, Wang C, Russell DG. 2004. Isolation of Mycobacterium tuberculosis mutants defective in the arrest of phagosome maturation. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 101, 13 642–13 647. (doi:10.1073/pnas.0401657101) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yates RM, Hermetter A, Russell DG. 2005. The kinetics of phagosome maturation as a function of phagosome/lysosome fusion and acquisition of hydrolytic activity. Traffic 6, 413–420. (doi:10.1111/j.1600-0854.2005.00284.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.de Chastellier C. 2009. The many niches and strategies used by pathogenic mycobacteria for survival within host macrophages. Immunobiology 214, 526–542. (doi:10.1016/j.imbio.2008.12.005) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.de Chastellier C, Thilo L. 1997. Phagosome maturation and fusion with lysosomes in relation to surface property and size of the phagocytic particle. Eur. J. Cell Biol. 74, 49–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pietersen R, Thilo L, de Chastellier C. 2004. Mycobacterium tuberculosis and Mycobacterium avium modify the composition of the phagosomal membrane in infected macrophages by selective depletion of cell surface-derived glycoconjugates. Eur. J. Cell Biol. 83, 153–158. (doi:10.1078/0171-9335-00370) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Stamm LM, et al. 2003. Mycobacterium marinum escapes from phagosomes and is propelled by actin-based motility. J. Exp. Med. 198, 1361–1368. (doi:10.1084/jem.20031072) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.van der Wel N, Hava D, Houben D, Fluitsma D, van Zon M, Pierson J, Brenner M, Peters PJ. 2007. M. tuberculosis and M. leprae translocate from the phagolysosome to the cytosol in myeloid cells. Cell 129, 1287–1298. (doi:10.1016/j.cell.2007.05.059) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Simeone R, Bobard A, Lippmann J, Bitter W, Majlessi L, Brosch R, Enninga J. 2012. Phagosomal rupture by Mycobacterium tuberculosis results in toxicity and host cell death. PLoS Pathog. 8, e1002507 (doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1002507) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dubée V, et al. 2015. β- Lactamase inhibition by avibactam in Mycobacterium abscessus. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 70, 1051–1058. (doi:10.1093/jac/dku510) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Huang J, Brumell JH. 2014. Bacteria–autophagy interplay: a battle for survival. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 12, 101–114. (doi:10.1038/nrmicro3160) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zullo AJ, Lee S. 2012. Mycobacterial induction of autophagy varies by species and occurs independently of mammalian target of rapamycin inhibition. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 12 668–12 678. (doi:10.1074/jbc.M111.320135) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bah A, Lacarrière C, Vergne I. 2016. Autophagy-related proteins target ubiquitin-free mycobacterial compartment to promote killing in macrophages. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 6, 53 (doi:10.3389/fcimb.2016.00053) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bryant JM, Grogono DM, Parkhill J, Floto RA. 2013. Transmission of M. abscessus in patients with cystic fibrosis—authors’ reply. Lancet 382, 504 (London, England) (doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61709-2) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Davidson LB, Nessar R, Kempaiah P, Perkins DJ, Byrd TF. 2011. Mycobacterium abscessus glycopeptidolipid prevents respiratory epithelial TLR2 signaling as measured by HD2 gene expression and IL-8 release. PLoS ONE 6, e29148 (doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0029148) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Baltierra-Uribe SL, de García-Vásquez MJ, Castrejón-Jiménez NS, Estrella-Piñón MP, Luna-Herrera J, García-Pérez BE. 2014. Mycobacteria entry and trafficking into endothelial cells. Can. J. Microbiol. 60, 569–577. (doi:10.1139/cjm-2014-0087) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Simeone R, Sayes F, Song O, Gröschel MI, Brodin P, Brosch R, Majlessi L. 2015. Cytosolic access of Mycobacterium tuberculosis: critical impact of phagosomal acidification control and demonstration of occurrence in vivo. PLoS Pathog. 11, e1004650 (doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1004650) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Deretic V, Saitoh T, Akira S. 2013. Autophagy in infection, inflammation and immunity. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 13, 722–737. (doi:10.1038/nri3532) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hmama Z, Peña-Díaz S, Joseph S, Av-Gay Y. 2015. Immunoevasion and immunosuppression of the macrophage by Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Immunol. Rev. 264, 220–232. (doi:10.1111/imr.12268) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Fratti RA, Chua J, Vergne I, Deretic V. 2003. Mycobacterium tuberculosis glycosylated phosphatidylinositol causes phagosome maturation arrest. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 100, 5437–5442. (doi:10.1073/pnas.0737613100) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Corrales RM, Molle V, Leiba J, Mourey L, de Chastellier C, Kremer L. 2012. Phosphorylation of mycobacterial PcaA inhibits mycolic acid cyclopropanation: consequences for intracellular survival and for phagosome maturation block. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 26 187–26 199. (doi:10.1074/jbc.M112.373209) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Cambier CJ, Takaki KK, Larson RP, Hernandez RE, Tobin DM, Urdahl KB, Cosma CL, Ramakrishnan L. 2014. Mycobacteria manipulate macrophage recruitment through coordinated use of membrane lipids. Nature 505, 218–222. (doi:10.1038/nature12799) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Villeneuve C, Etienne G, Abadie V, Montrozier H, Bordier C, Laval F, Daffe M, Maridonneau-Parini I, Astarie-Dequeker C. 2003. Surface-exposed glycopeptidolipids of Mycobacterium smegmatis specifically inhibit the phagocytosis of mycobacteria by human macrophages: identification of a novel family of glycopeptidolipids. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 51 291–51 300. (doi:10.1074/jbc.M306554200) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Rhoades ER, Archambault AS, Greendyke R, Hsu F-F, Streeter C, Byrd TF. 2009. Mycobacterium abscessus glycopeptidolipids mask underlying cell wall phosphatidyl-myo-inositol mannosides blocking induction of human macrophage TNF-α by preventing interaction with TLR2. J. Immunol. 183, 1997–2007. (doi:10.4049/jimmunol.0802181) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Frehel C, de Chastellier C, Lang T, Rastogi N. 1986. Evidence for inhibition of fusion of lysosomal and prelysosomal compartments with phagosomes in macrophages infected with pathogenic Mycobacterium avium. Infect Immun. 52, 252–262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Tereletsky MJ, Barrow WW. 1983. Postphagocytic detection of glycopeptidolipids associated with the superficial L1 layer of Mycobacterium intracellulare. Infect Immun. 41, 1312–1321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Shimada K, Takimoto H, Yano I, Kumazawa Y. 2006. Involvement of mannose receptor in glycopeptidolipid-mediated inhibition of phagosome-lysosome fusion. Microbiol. Immunol. 50, 243–251. (doi:10.1111/j.1348-0421.2006.tb03782.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kano H, Doi T, Fujita Y, Takimoto H, Yano I, Kumazawa Y. 2005. Serotype-specific modulation of human monocyte functions by glycopeptidolipid (GPL) isolated from Mycobacterium avium complex. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 28, 335–339. (doi:10.1248/bpb.28.335) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ripoll F, et al. 2007. Genomics of glycopeptidolipid biosynthesis in Mycobacterium abscessus and M. chelonae. BMC Genomics 8, 114 (doi:10.1186/1471-2164-8-114) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Harriff MJ, Wu M, Kent ML, Bermudez LE. 2008. Species of environmental mycobacteria differ in their abilities to grow in human, mouse, and carp macrophages and with regard to the presence of mycobacterial virulence genes, as observed by DNA microarray hybridization. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 74, 275–285. (doi:10.1128/AEM.01480-07) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kocincova D, Winter N, Euphrasie D, Daffe M, Reyrat J-M, Etienne G. 2009. The cell surface-exposed glycopeptidolipids confer a selective advantage to the smooth variants of Mycobacterium smegmatis in vitro. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 290, 39–44. (doi:10.1111/j.1574-6968.2008.01396.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Pawlik A, et al. 2013. Identification and characterization of the genetic changes responsible for the characteristic smooth-to-rough morphotype alterations of clinically persistent Mycobacterium abscessus. Mol. Microbiol. 90, 612–629. (doi:10.1111/mmi.12387) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Houben D, et al. 2012. ESX-1-mediated translocation to the cytosol controls virulence of mycobacteria. Cell Microbiol. 14, 1287–1298. (doi:10.1111/j.1462-5822.2012.01799.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Wassermann R, et al. 2015. Mycobacterium tuberculosis differentially activates cGAS- and inflammasome-dependent intracellular immune responses through ESX-1. Cell Host Microbe 17, 799–810. (doi:10.1016/j.chom.2015.05.003) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Wang J, et al. 2015. Insights on the emergence of Mycobacterium tuberculosis from the analysis of Mycobacterium kansasii. Genome Biol. Evol. 7, 856–870. (doi:10.1093/gbe/evv035) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Bakala N'Goma JC, et al. 2015. Mycobacterium abscessus phospholipase C expression is induced during coculture within amoebae and enhances M. abscessus virulence in mice. Infect Immun. 83, 780–791. (doi:10.1128/IAI.02032-14) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Choo SW, et al. 2014. Genomic reconnaissance of clinical isolates of emerging human pathogen Mycobacterium abscessus reveals high evolutionary potential. Sci. Rep. 4, 4061 (doi:10.1038/srep04061) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Sapriel G, et al. 2016. Genome-wide mosaicism within Mycobacterium abscessus: evolutionary and epidemiological implications. BMC Genomics 17, 118 (doi:10.1186/s12864-016-2448-1) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Snouwaert JN, Brigman KK, Latour AM, Malouf NN, Boucher RC, Smithies O. Koller BH. 1992. An animal model for cystic fibrosis made by gene targeting. Science 257, 1083–1088. (doi:10.1126/science.257.5073.1083) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Colledge WH, et al. 1995. Generation and characterization of a delta F508 cystic fibrosis mouse model. Nat. Genet. 10, 445–452. (doi:10.1038/ng0895-445) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Dulphy N, Herrmann J-L, Nigou J, Rea D, Boissel N, Puzo G, Charron D, Lagrange PH, Toubert A. 2007. Intermediate maturation of Mycobacterium tuberculosis LAM-activated human dendritic cells. Cell Microbiol. 9, 1412–1425. (doi:10.1111/j.1462-5822.2006.00881.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Guerardel Y, Maes E, Briken V, Chirat F, Leroy Y, Locht C, Strecker G, Kremer L. 2003. Lipomannan and lipoarabinomannan from a clinical isolate of Mycobacterium kansasii: novel structural features and apoptosis-inducing properties. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 36 637–36 651. (doi:10.1074/jbc.M305427200) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.