Abstract

Strong social bonds form between individuals in many group-living species, and these relationships can have important fitness benefits. When responding to vocalizations produced by groupmates, receivers are expected to adjust their behaviour depending on the nature of the bond they share with the signaller. Here we investigate whether the strength of the signaller–receiver social bond affects response to calls that attract others to help mob a predator. Using field-based playback experiments on a habituated population of wild dwarf mongooses (Helogale parvula), we first demonstrate that a particular vocalization given on detecting predatory snakes does act as a recruitment call; receivers were more likely to look, approach and engage in mobbing behaviour than in response to control close calls. We then show that individuals respond more strongly to these recruitment calls if they are from groupmates with whom they are more strongly bonded (those with whom they preferentially groom and forage). Our study, therefore, provides novel evidence about the anti-predator benefits of close bonds within social groups.

Keywords: social bonds, vocal communication, recruitment calling, snake mobbing, anti-predator behaviour, dwarf mongoose

1. Introduction

A common feature of stable social groups is the presence of close bonds, or ‘friendships', between individuals [1,2]. While there are many different ways to quantify the strength of such relationships [3], it is recognized that ‘strong’ bonds with groupmates can provide considerable long-term health and fitness benefits [1,2]. However, less is known about potential short-term survival benefits [1,4]. Reduction of predation risk is facilitated in many species by a range of different acoustic signals that can induce fleeing, increase vigilance and coordinate defensive actions [5,6]. Recent work on chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes) and yellow-bellied marmots (Marmota flaviventris) has shown that the propensity of individuals to give flee alarm calls can depend on the presence of close affiliates and their own position in a social network [7,8]. Behavioural adjustments in response to at least some anti-predator vocalizations (e.g. those that coordinate defence) might also be expected depending on the level of affiliation with the caller, but little attention has been paid to receivers in this regard (see [4] for an exception).

In many taxa, certain vocalizations serve to attract others to the caller. These ‘recruitment’ calls often advertise the location of a food source [9], but are also given when individuals encounter specific predators [10]. Predator-related recruitment calls can engage both conspecifics and heterospecifics in collective mobbing behaviour, with responders purposefully approaching and harassing the threat [10–12]. Mobbing is costly in terms of potential injury or death, lost foraging time and the risk of attracting further predators [13–15]. Like many other vocalizations, predator-related recruitment calls can convey information about the caller's identity [4,16]. However, only one empirical study has considered how within-group signaller–receiver bond strength might influence call responses: crested macaques (Macaca nigra) oriented for longer towards a loudspeaker playing recruitment calls of close affiliates compared with those of weak affiliates [4].

Here we use field playback experiments to examine whether caller identity influences receiver responses to the calls given by dwarf mongooses (Helogale parvula) on encountering predatory snakes. Having first demonstrated that these calls do indeed function to recruit group members, we investigate the role of social-bond strength between callers and responders. Specifically, we test whether individuals show greater responses to the recruitment calls of individuals to which they are more strongly bonded.

2. Material and methods

(a). Study site and population

Data were collected on Sorabi Rock Lodge Reserve, South Africa from nine wild dwarf mongoose groups habituated to close observation [17,18]; full methodology in the electronic supplementary material; datasets available in [19]. Data on natural mobbing events—approaching, cooperative harassing and attacking of a predator—were collected using all-occurrence sampling between January 2014 and March 2016.

(b). Playback experiment 1

To test whether the calls given by dwarf mongooses when they detect a predator to be mobbed (see §3) function to recruit others, we compared responses to playback of these calls and control close calls given while foraging (electronic supplementary material, figure S1). Putative ‘recruitment’ calls were recorded during natural snake-mobbing events and rubber-snake presentations. Close calls were recorded opportunistically during foraging bouts. Nine randomly selected subordinate individuals received separate 10 min playbacks of the two call types at natural rates and amplitudes. Playbacks to the same focal individual were of calls from the same adult subordinate group member and were separated by 1 h; the presentation order of the two playback types was alternated to different focal individuals. Focal individuals were filmed during playback, and data on looking, approaching and mobbing behaviour were subsequently extracted.

(c). Playback experiment 2

To assess how the response to recruitment calls is influenced by signaller–receiver social-bond strength, we conducted a second playback experiment. Eight individuals from four groups (those with sufficient subordinate group members to enable comparison of a stronger and weaker social bond) each received two 10 min playbacks of recruitment calls, one from a subordinate groupmate with whom they shared a relatively strong bond and one with whom they shared a relatively weak bond. Social-bond strengths were determined from composite sociality indexes (CSI) [4,20] based on grooming and nearest-neighbour foraging distances. The use of multiple behavioural indices strengthens the assessment of bond strength, and previous research has established that grooming and foraging associations are strongly correlated within dwarf mongoose groups (full details in the electronic supplementary material). Experimental signaller–receiver dyads were selected to maximize the difference in CSI scores for a given focal individual. Playbacks to the same focal individual were separated by 7.5 ± 2.3 days (mean ± s.e.; range: 2–15); group size was the same for both trials to the same individual. Variation in the time between trials to the same focal individual did not significantly affect either the absolute response shown in the second trial (Jonckheere-Terpstra test, duration of looking: TJT = 17, N = 8, p = 0.24; duration of physical response: TJT = 11, N = 8, p = 0.61) or the difference in response between the two trials (duration of looking: TJT = 12, N = 8, p = 0.90; duration of physical response: TJT = 15, N = 8, p = 0.43). The presentation order of the two playbacks was alternated to different focal individuals. Focal individuals were filmed, and data extracted, as in Experiment 1.

(d). Statistical analysis

The response of focal foragers to the two types of call (Experiment 1) were analysed using two McNemar related-samples tests (for tendencies to look at and to approach the speaker) and two Wilcoxon's signed-rank tests (for durations of looking and physical responses; the latter defined as the time spent approaching and mobbing). Data from Experiment 2 were analysed using linear mixed models (LMMs) and generalized linear mixed models (GLMMs) to account for data collection from more than one focal individual per group. For all models, the fixed effects of social-bond strength (strong, weak), group size and trial order (1, 2) were fitted, and focal individual nested in group was included as a random term.

3. Results

Sixty-one natural mobbing events were observed in response to snakes (puff adders (Bitis arietans), Mozambique spitting cobras (Naja mossambica), black mambas (Dendroaspis polylepis), African rock pythons (Python sebae)). In all cases, the first individual to locate the threat gave a particular vocalization (electronic supplementary material, figure S1a); this was the vocalization tested in the playback experiments. Other group members approached the caller, searched for the threat and then surrounded the predator, displaying typical mobbing behaviours such as head bobbing and weaving, striking at the predator and threat scratching. Mobbing events lasted for 697 ± 148 s (mean ± s.e.) and involved 62 ± 4% of the group.

Compared with close-call playback, playback of calls given on detecting snakes (see above) resulted in focal foragers being more likely to look at the speaker (McNemar's test: N = 9 paired playbacks, p = 0.013), looking for longer (Wilcoxon's signed-rank test: Z = 0, N = 9, p = 0.004), being more likely to approach the speaker (McNemar's test: N = 9 paired playbacks, p = 0.041) and responding physically for longer (Wilcoxon's signed-rank test: Z = 0, N = 9, p = 0.014).

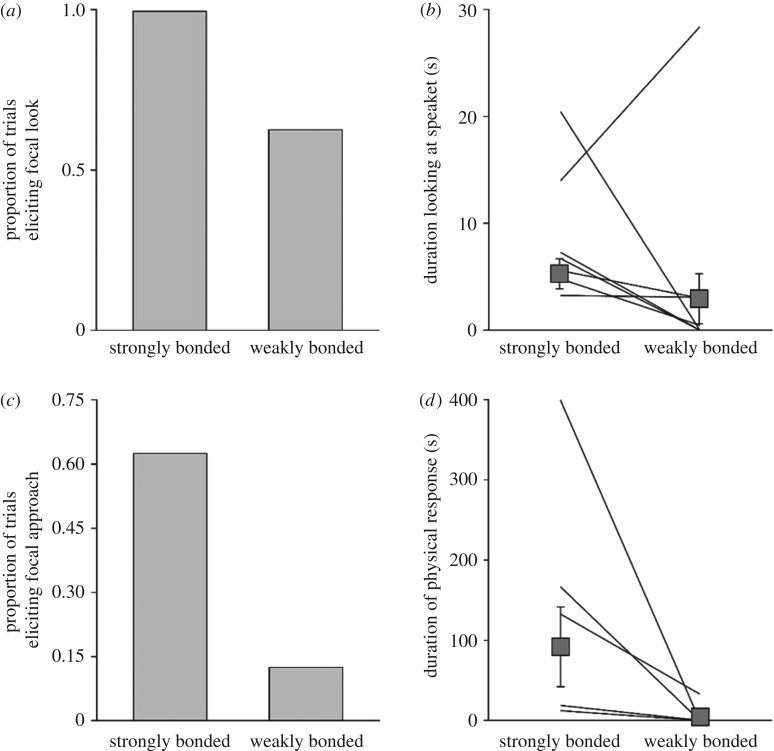

Controlling for a significant negative effect of trial order in several cases (electronic supplementary material, table S1), focal foragers were more likely to look at the speaker (GLMM: χ2 = 4.56, d.f. = 1, p = 0.033; figure 1a), looked for longer (LMM: χ2 = 11.06, d.f. = 1, p = 0.001; figure 1b), were more likely to approach the speaker (GLMM: χ2 = 10.62, d.f. = 1, p = 0.001; figure 1c) and responded physically for longer (LMM: χ2 = 854.95, d.f. = 1, p < 0.001; figure 1d) when played recruitment calls from individuals to which they were strongly bonded compared with those from groupmates to which they were more weakly bonded.

Figure 1.

Response of dwarf mongooses to the playback of recruitment calls given by groupmates to which they are strongly or weakly bonded. (a) Proportion of trials eliciting looking at speaker, (b) total duration looking at speaker, (c) proportion of trials eliciting approach to speaker and (d) total duration of physical response. For (a–c), N = eight individuals, four groups; for (d), N = seven individuals, three groups. Shown for (b) and (d) are results for each focal individual separately (lines) and the overall treatment mean (solid squares) ± s.e.

4. Discussion

Our study shows that, on detecting predatory snakes, dwarf mongooses produce specific vocalizations that act as recruitment calls. These calls increase the likelihood of the caller being joined by other group members in mobbing the threat, as is the case in various other species [10,11]. We demonstrate experimentally that the response to these recruitment calls differs depending on the social-bond strength shared by the signaller and receiver. Individuals showed a greater response (in terms of looking, approaching and mobbing) when hearing recruitment calls from groupmates to which they were strongly bonded compared with those with which they shared a weaker bond. Although a previous study indicated that crested macaques orientated more to (i.e. looked in the direction of) the recruitment calls of close affiliates than weak affiliates, they found no difference in the tendency to approach or duration of response [4]. To our knowledge, the current work is, therefore, the first to show greater active responses to the recruitment calls of groupmates with whom receivers share stronger bonds (see [21] for an example of how long-term familiarity increases the likelihood that neighbours assist one another in nest defence).

Heightened responses to the recruitment calling of particular group members could theoretically be a by-product of factors influencing the formation of social bonds. If individuals were more likely to form strong bonds with groupmates of similar age and size, for example, dyads with strong bonds would have similar risk profiles. Mobbing behaviour by one of these other individuals would thus be a potentially good indication of a threat to self. Within dwarf mongoose groups, however, there is much variation in social-bond strength between individuals of the same age (JM Kern 2016, unpublished data). Indeed, in several cases, the strongly and weakly bonded experimental individuals were littermates. Instead, the preferential response to recruitment calls from strongly bonded groupmates may arise from a trade-off between the benefits and costs, given that mobbing behaviour is costly [13–15]. There are a number of potential such possibilities.

First, it has been suggested that mobbing may function as a costly signal, advertising individual quality to conspecifics [22]. Individuals may invest more in signalling their quality to those with which they share strong bonds to uphold their attractiveness as a close partner, though so far support for this hypothesis is lacking [12,23]. Second, individuals may preferentially associate with close affiliates in stressful situations. In pilot whales (Globicephala melas), for example, closely affiliated dyads increase their synchronization when swimming in stressful circumstances [24]. Third, there may be variation in the relative costs and benefits of responding to callers with whom receivers have stronger or weaker bonds. The effectiveness of mobbing increases with the number of participants [15], thus groupmates may directly improve the survival chances of a caller when they respond to recruitment calls. Reciprocal cooperation, often performed over long time periods, may also be more likely between strongly bonded individuals [25]. Receivers who respond to close affiliates now may, therefore, stand to gain future advantages, including likely assistance themselves in future mobbing events or intra-group conflicts [26], in addition to the ongoing advantages of close friendships.

Recent experimental work using other call types has demonstrated an effect of social-bond strength and other social attributes on caller behaviour [26]. Here, we show an effect of social bonds on receiver responses (see also [4]), enhancing our understanding of the role of social bonds in intra-group interactions. While the long-term benefits of close social bonds are well established, particularly in primates, the potential in other species and in the context of predation has been little explored. In general, by adjusting their responses depending on caller identity, receivers can facilitate more efficient and effective use of social information.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank B. Rouwhorst and H. Yeates for access to their land, C. Esterhuizen for logistical support and 12 research assistants for observational data collection.

Ethics

This study was conducted under permission from the Department of Environmental Affairs and Tourism, Limpopo Province, South Africa (permit number: 001-CPM403-00013) and with approval from the relevant Ethical Review Groups at the University of Pretoria, South Africa (Animal Use and Care Committee no. EC057-11) and the University of Bristol, UK (university investigator no. UB/14/044).

Data accessibility

Kern JM, Radford AN. 2016 Data from: Social-bond strength influences vocally mediated recruitment to mobbing. Dryad Digital Repository. (http://dx.doi.org/10.5061/dryad.6ph26).

Authors' contributions

J.M.K. and A.N.R. designed the study; J.M.K. collected the data; J.M.K. analysed the data with advice from A.N.R.; J.M.K and A.N.R. interpreted the data and co-wrote the paper. Both authors approve the final version of the manuscript and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Competing interests

We have no competing interests.

Funding

The work was supported by a University of Bristol studentship to J.M.K.

References

- 1.Seyfarth RM, Cheney DL. 2012. The evolutionary origins of friendship. Ann. Rev. Psychol. 63, 153–177. ( 10.1146/annurev-psych-120710-100337) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Silk JB. 2014. Evolutionary perspectives on the links between close social bonds, health and fitness. In Sociality, hierarchy, health: comparative biodemography (eds Weinstein M, Lane M), pp. 121–143. Washington, DC: National Academies Press. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Silk J, Cheney D, Seyfarth R.. 2013. A practical guide to the study of social relationships. Evol. Anthropol. 22, 213–225. ( 10.1002/evan.21367) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Micheletta J, Waller BM, Panggur MR, Neumann C, Duboscq J, Agil M, Engelhardt A.. 2012. Social bonds affect anti-predator behaviour in a tolerant species of macaque, Macaca nigra. Proc. R. Soc. B 279, 4042–4050. ( 10.1098/rspb.2012.1470) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hollén LI, Radford AN. 2009. The development of alarm call behaviour in mammals and birds. Anim. Behav. 78, 791–800. ( 10.1016/j.anbehav.2009.07.021) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Magrath RD, Haff TM, Fallow PM, Radford AN. 2015. Eavesdropping on heterospecific alarm calls: from mechanisms to consequences. Biol. Rev. 90, 560–586. ( 10.1111/brv.12122) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schel AM, Townsened SW, Machanda Z, Zuberbühler K, Slocombe KE. 2013. Chimpanzee alarm call production meets key criteria for intentionality. PLoS ONE 8, e76674 ( 10.1371/journal.pone.0076674) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fuong H, Maldonado-Chaparro A, Blumstein DT. 2015. Are social attributes associated with alarm calling propensity? Behav. Ecol. 26, 587–592. ( 10.1093/beheco/aru235) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Radford AN, Ridley AR. 2006. Recruitment calling: a novel form of extended parental care in an altricial species. Curr. Biol. 16, 1700–1704. ( 10.1016/j.cub.2006.06.053) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Curio E. 1978. The adaptive significance of avian mobbing. I. Teleonomic hypotheses and predictions. Ethology 46, 175–183. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Caro TM. 2005. Antipredator defenses in birds and mammals. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Graw B, Manser MB. 2007. The function of mobbing in cooperative meerkats. Anim. Behav. 74, 507–517. ( 10.1016/j.anbehav.2006.11.021) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Owings DH, Coss RG. 1977. Snake mobbing by California ground squirrels: adaptive variation and ontogeny. Behaviour 62, 50–68. ( 10.1163/156853977X00045) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cowlishaw G. 1994. Vulnerability to predation in baboon populations. Behaviour 131, 293–304. ( 10.1163/156853994X00488) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Krams I, Krama T, Igaune K, Mänd R.. 2007. Long-lasting mobbing of the pied flycatcher increases the risk of nest predation. Behav. Ecol. 18, 1082–1084. ( 10.1093/beheco/arm079) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kennedy RAW, Evans CS, McDonald PG. 2009. Individual distinctiveness in the mobbing call of a cooperative bird, the noisy miner Manorina melanocephala. J. Avian Biol. 40, 481–490. ( 10.1111/j.1600-048X.2008.04682.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kern JM, Radford AN. 2013. Call of duty? Variation in use of the watchman's song by sentinel dwarf mongooses, Helogale parvula. Anim. Behav. 85, 967–975. ( 10.1016/j.anbehav.2013.02.020) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kern JM, Radford AN. 2014. Sentinel dwarf mongooses Helogale parvula exhibit flexible decision making in relation to predation risk. Anim. Behav. 98, 185–192. ( 10.1016/j.anbehav.2014.10.012) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kern JM, Radford AN. 2016. Data from: Social-bond strength influences vocally-mediated recruitment to mobbing. Dryad Digital Repository. ( 10.5061/dryad.6ph26) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Silk JB, Altmann J, Alberts SC. 2006. Social relationships among adult female baboons (Papio cynocephalus). I. Variation in the strength of social bonds . Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 61, 183–195. ( 10.1007/s00265-006-0249-2) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Grabowska-Zhang AM, Sheldon BC, Hinde CA. 2012. Long-term familiarity promotes joining in neighbour nest defence. Biol. Lett. 8, 544–546. ( 10.1098/rsbl.2012.0183) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Maklakov AA. 2002. Snake-directed mobbing in a cooperative breeder: anti-predator behaviour or self-advertisement for the formation of dispersal coalitions? Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 52, 372–378. ( 10.1007/s00265-002-0528-5) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ostreiher R. 2003. Is mobbing altruistic or selfish behaviour? Anim. Behav. 66, 145–149. ( 10.1006/anbe.2003.2165) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Senigaglia V, de Stephanis R, Verborgh P, Lusseau D.. 2012. The role of synchronized swimming as affiliative and anti-predatory behavior in long-finned pilot whales. Behav. Processes 91, 8–14. ( 10.1016/j.beproc.2012.04.011) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mitani JC, Watts DP. 2001. Why do chimpanzees hunt and share meat? Anim. Behav. 61, 915–924. ( 10.1006/anbe.2000.1681) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Palombit RA, Seyfarth RM, Cheney DL. 1997. The adaptive value of ‘friendships’ to female baboons: experimental and observational evidence. Anim. Behav. 54, 599–614. ( 10.1006/anbe.1996.0457) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Kern JM, Radford AN. 2016 Data from: Social-bond strength influences vocally mediated recruitment to mobbing. Dryad Digital Repository. (http://dx.doi.org/10.5061/dryad.6ph26).