Abstract

Background

Cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 2A/2B (CDKN2A/2B) near chromosome 9p21 have been associated with both atherosclerosis and artery calcification, but the underlying mechanisms remained largely unknown. Considering that CDKN2A/2B is a frequently reported site for DNA methylation, this study aimed to evaluate whether carotid artery calcification (CarAC) is related to methylation levels of CDKN2A/2B in patients with ischemic stroke.

Methods

DNA methylation levels of CDKN2A/2B were measured in 322 ischemic stroke patients using peripheral blood leukocytes. Methylation levels of 36 CpG sites around promoter regions of CDKN2A/2B were examined with BiSulfite Amplicon Sequencing. CarAC was quantified with Agatston score based on results of computed tomography angiography. Generalized liner model was performed to explore the association between methylation levels and CarAC.

Results

Of the 322 analyzed patients, 187 (58.1%) were classified as with and 135 (41.9%) without evident CarAC. The average methylation levels of CDKN2B were higher in patents with CarAC than those without (5.7 vs 5.4, p = 0.001). After adjustment for potential confounders, methylation levels of CDKN2B were positively correlated with cube root transformed calcification scores (β = 0.591 ± 0.172, p = 0.001) in generalized liner model. A positive correlation was also detected between average methylation levels of CDKN2B and cube root transformed calcium volumes (β = 0.533 ± 0.160, p = 0.001).

Conclusions

DNA methylation of CDKN2B may play a potential role in artery calcification.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1186/s12967-016-1093-4) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Carotid artery calcification, CDKN2A/2B, DNA methylation, Ischemic stroke

Background

As a surrogate measure of atherosclerosis, calcification may contribute to plaque vulnerability and, therefore, risk of vascular events [1]. Because carotid bifurcation and adjacent segments are the predilection sites of atherosclerosis, calcification in these location can reflect the overall burden of vascular calcification [2], and may predict risk of stroke, myocardial infarction and the overall vascular events [3, 4].

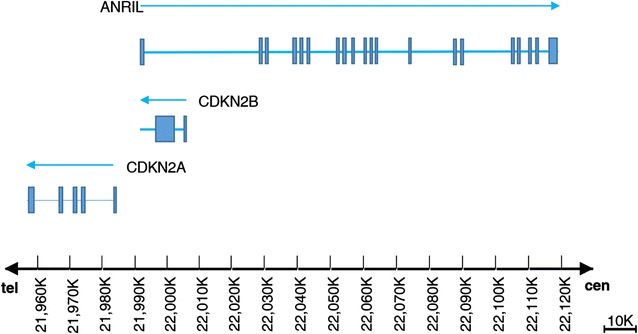

Genetic factors have long been proposed with an important role in the initiation and development of arterial calcification [5, 6]. After the landmark genome-wide association studies identified human chromosome 9p21 (Chr9p21) as a potential genetic origin both for atherosclerosis and artery calcification [7–9], determining gene variants responsible for artery calcification has become a focus of many studies. Intriguingly, Chr9p21 region is actually a “gene desert” devoid of annotated protein-coding genes. Only the antisense noncoding RNA in the INK4 locus (ANRIL) is transcribed in this region. The closest protein-coding genes to Chr9p21 locus are two cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors, CDKN2A and CDKN2B, both of which involve in cell cycle regulation (Fig. 1). This locational neighborhood between Chr9p21 and CDKN2A/2B may suggest their functional associations, which have been evidenced by results from recent studies [10, 11]. For example, Motterle et al. showed that Chr9p21 variation can change the level of ANRIL transcription, which in turn alter expression of CDKN2A/2B and enhance proliferation of vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMCs), and subsequently promote atherosclerosis [11].

Fig. 1.

Illustration of genomic organization of the 9p21 locus. Blue lines with arrows represent the approximate locations and transcribe directions of CDKN2A, CDKN2B and ANRIL. Blue boxes indicate exons. ANRIL is transcribed in opposite direction of CDKN2A/2B genes. Cen indicates centromere, and tel indicates telomere

Both functional [12] and genetic studies [13, 14] suggested that CDKN2A/2B may promote atherosclerosis by facilitating the process of calcification. But the mechanisms remain largely unknown. Considering that CDKN2A/2B is a frequently reported site of action for DNA methylation [15, 16], we hypothesized that DNA methylation in CDKN2A/2B may increase the susceptibility of artery calcification. In this study, we tested this hypothesis by evaluating the degree of DNA methylation in CDKN2A/2B and the carotid calcification load in a cohort of patients with ischemic stroke.

Methods

Study population

This study was approved by the Ethical Review Board of Jinling Hospital. Written informed consent was obtained from all enrolled patients. Consecutive patients with ischemic stroke were screened from Nanjing Stroke Registry Program [17] between July 2012 and September 2013. Patients were included if they: (1) were diagnosed with first-ever ischemic stroke within 7 days of onset; (2) aged 18 years or older; (3) completed a neck computed tomography angiography (CTA). Ischemic stroke was diagnosed if there were new focal neurological deficits explained by relevant lesions detected on diffusion-weighted imaging or computed tomography. Patients with malignant neoplasm, severe liver or kidney dysfunction, autoimmune diseases, parathyroid gland diseases, or calcium-phosphorus metabolic disorders were excluded. Since the stents may influence the accuracy of calcification assessment, patients with history of carotid artery stenting were also excluded. A total of 391 patients were screened and 324 patients were finally enrolled.

Artery calcification measurement

Each enrolled patient underwent a neck computed tomography angiography for CarAC evaluation. CTA was performed by a dual-source 64 slice CT system (Siemens, Forchheim, Germany) to quantify CarAC. Imaging was acquired by scanning from 4 cm below aortic arch to the superior border of orbit in craniocaudal direction. Details on CTA scan have been provided elsewhere [18].

Calcification scores in carotid artery were measured with Syngo Calcium Scoring system (Siemens, Forchheim, Germany). A focus of ≥4 contiguous pixels accompanied by a CT density ≥130 Hounsfield units (HU) was defined as calcification according to the method of Agatston score [19]. Area of calcification (mm2) was multiplied by a weighted value assigned to its highest HU (130–199HU = 1; 200–299HU = 2; 300–399HU = 3; and >400HU = 4). Carotid calcification was measured at both sides within 3 cm proximal and distal segments of the bifurcation including four artery segments: common, bulb, internal, and external. The software used for calculating Agatston score also provided an isotropically interpolated calcium volume (mm3), by calculating the numbers of voxels with attenuation ≥130HU and summing the total voxel volumes. Calcification scores and calcium volume were assessed by two raters independently. The raters were blinded to other clinical data.

DNA isolation and epi-genotyping

Venous blood samples were drawn in the morning after an overnight fasting for biochemical marker assaying and methylation analyzing. Genomic DNA was extracted from whole blood with commercially available kits (TIANGEN Biotech, Beijing, China). DNA was quantified and then diluted to a working concentration of 10 ng/μL for genotyping.

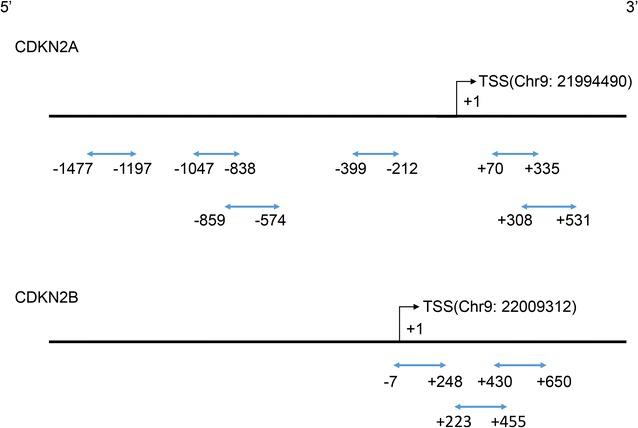

CpG islands located in the proximal promoter of CDKN2A/2B were selected for measurement according to the following criteria: (1) 200 bp minimum length; (2) 50% or higher GC content; (3) 0.60 or higher ratio of observed/expected dinucleotides CpG. Six regions from CpG islands of CDKN2A and three from that of CDKN2B were selected and sequenced (Fig. 2). BiSulfite Amplicon Sequencing (BSAS) was used for quantitative methylation analysis [20]. Bisulfite conversion of 1 μg genomic DNA was performed with the EZ DNA Methylation™-GOLD Kit (ZYMO RESEARCH, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Sodium bisulfite preferentially deaminates unmethylated cytosine residues to thymines, whereas methyl-cytosines remain unmodified. After PCR amplification (HotStarTaq polymerase kit, TAKARA, Tokyo, Japan) of target CpG regions and library construction, the products were sequenced on Illumina MiSeq Benchtop Sequencer (CA, USA). Primer sequences used for PCR were shown in Additional file 1: Table S1. All samples achieved a mean coverage of >600X. Each tested CpG site was named as its relative distance (in bp) to transcriptional start site (TSS). Methylation level at each CpG site was calculated as the percentage of the methylated cytosines over the total tested cytosines. The average methylation level was calculated using methylation levels of all measured CpG sites within the gene.

Fig. 2.

CpG regions sequenced around promoter of CDKN2A/2B. Blue lines with arrows indicate selected CpG regions analyzed in this study, all of which locate in CpG islands around gene promoters. Range of each region is indicated by its relative distance (in bp) to TSS

Statistical analysis

Normality of parameters was assessed by Shapiro–Wilk test. As all continuous data in this study did not meet the normality assumption, they were described as median (interquartile range) and compared with Mann–Whitney U test. The non-parameters were compared with Fisher’s exact test. Patients were classified as without (Agatston score = 0), with mild (0 < Agatston score ≤ 100) and with severe (Agatston score > 100) CarAC. Methylation levels of CDKN2A/2B were compared between patients with and without CarAC using Mann–Whitney U test. Methylation levels of CDKN2A/2B were also compared among patients with mild, severe and without CarAC using Kruskal–Wallis test.

Spearman correlations were used to evaluate pairwise correlations of methylation levels between different CpG sites in the same gene. Given the heavily skewed distribution of calcification scores and calcium volume, cube root transformation was performed before comparison, as suggested in the previous studies [21, 22]. Generalized linear model was used to explore the association between methylation levels and cube root transformed calcification scores/calcium volumes after adjusting for age, sex, body mass index (BMI), diabetes mellitus (DM), hypertension (HTN) and smoking. These variables were chose for adjustment because they were identified as confounders that affected artery calcification. Bonferroni correction was used for multiple testing.

The data were analyzed by IBM SPSS Statistics Version 22.0 (Armonk, NY: IBM Corp.). A two-tailed value of p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Of the 324 enrolled patients, 2 (0.6%) failed in epi-genotyping. Finally, 322 (99.4%) patients were included for data analysis. Demographic characteristics and major risk factors for cardiovascular diseases were listed in Table 1. The median age of the 322 analyzed patients was 62.0 (55.0–70.0) years, and 229 (71.1%) of them were male. There were 250 (77.6%) patients with HTN and 110 (34.2%) with DM.

Table 1.

Comparison of demographic characteristics between patients with and without CarAC

| Characteristics | All (n = 322) | CarAC | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| With (n = 187) | Without (n = 135) | |||

| Age, years | 62.0 (55.0–70.0) | 66.0 (58.0–73.0) | 57.0 (47.0–64.0) | <0.001 |

| Male, n (%) | 229 (71.1) | 132 (70.6) | 97 (71.9) | 0.901 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 24.7 (22.9–26.1) | 24.5 (22.6–26.0) | 24.9 (23.7–26.4) | 0.032 |

| HTN, n (%) | 250 (77.6) | 155 (82.9) | 95 (70.4) | 0.010 |

| DM, n (%) | 110 (34.2) | 74 (39.6) | 36 (26.7) | 0.017 |

| CAD, n (%) | 24 (7.5) | 16 (8.6) | 8 (5.9) | 0.400 |

| TC, mmol/L | 4.21 (3.58–5.00) | 4.17 (3.40–4.93) | 4.28 (3.83–5.12) | 0.029 |

| TG, mmol/L | 1.40 (1.09–1.88) | 1.36 (1.03–1.75) | 1.54 (1.17–2.02) | 0.016 |

| HDL, mmol/L | 0.98 (0.82–1.15) | 0.98 (0.81–1.15) | 0.99 (0.84–1.16) | 0.363 |

| LDL, mmol/L | 2.61 (1.93–3.18) | 2.57 (1.79–3.18) | 2.68 (2.20–3.19) | 0.180 |

| Glucose, mmol/L | 5.3 (4.6–6.6) | 5.3 (4.7–6.8) | 5.2 (4.6–6.2) | 0.260 |

| Smoking, n (%) | 132 (41.0) | 81 (43.3) | 51 (37.8) | 0.359 |

| Drinking, n (%) | 96 (29.8) | 58 (31.0) | 38 (28.1) | 0.622 |

Statistically signficant values are in italics

Data are presented as number of patients (%) or median (interquartile range)

CarAC carotid artery calcification; BMI body mass index; HTN hypertension; DM diabetes mellitus; CAD coronary artery disease; TC total cholesterol; TG triglyceride; HDL high-density lipoprotein; LDL low-density lipoprotein

Based on Agatston score, 187 (58.1%) patients were grouped as with and 135 (41.9%) without CarAC. CarAC scores presented an extremely left-skewed distribution with a median (interquartile range) of 9.0 (0–111.1). The mean calcium volume (mm3) was 11.0 (0–98.0). Compared with patients without CarAC, those with CarAC were older (66.0 vs 57.0 years, p < 0.001), and had higher prevalences of HTN (82.9 vs 70.4%, p = 0.010) and DM (39.6 vs 26.7%, p = 0.017). Patients with CarAC had lower BMI (24.5 vs 24.9, p = 0.032), lower TC (4.17 vs 4.28 mmol/L, p = 0.029) and lower TG (1.36 vs 1.54 mmol/L, p = 0.016) levels (Table 1).

According to the results measured from target regions, there were 36 CpG sites (24 in CDKN2A and 12 in CDKN2B) identified as methylated sites (detailed information of each site was shown in Additional file 1: Table S2). The distribution of methylation levels of the 36 CpGs were listed in Additional file 1: Table S3. Methylation levels of CpG sites measured within CDKN2A were not significantly correlated, while those within CDKN2B were significantly correlated (Additional file 1: Table S4 and S5).

The methylation levels of each CpG site and average percent methylation of CDKN2A/2B were compared between patients with and without CarAC (Table 2). Higher methylation levels of CDKN2B were observed in patients with CarAC (5.7 vs 5.4, p = 0.001) compared to those without CarAC. When patients were grouped as with no, mild or severe CarAC, patients with severe CarAC had highest levels of CDKN2B (5.4 vs 5.6 vs 5.9, p < 0.001) as shown in Table 3. After adjusting for age, sex, BMI, DM, HTN and smoking, generalized liner model detected a positive correlation between average methylation levels of CDKN2B and cube root transformed calcification scores (β = 0.591 ± 0.172, p = 0.001, Table 4). And average methylation levels of CDKN2B were also associated with (cube root) calcium volumes (β = 0.533 ± 0.160, p = 0.001) after the adjustment. When further corrected for multiple comparison, CDKN2B methylation levels were still associated with cube root transformed calcification scores (corrected p = 0.002) and calcium volumes (corrected p = 0.002).

Table 2.

Differences of methylation levels (%) between patients with and without CarAC

| Gene | Position | CarAC | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| With | Without | |||

| CDKN2A | 1 | 4.4 (3.0–6.0) | 4.1 (2.7–5.9) | 0.480 |

| 2 | 7.1 (5.3–8.9) | 6.7 (5.4–8.5) | 0.520 | |

| 3 | 8.2 (6.8–10.7) | 8.0 (6.3–9.6) | 0.130 | |

| 4 | 5.8 (4.2–8.0) | 5.8 (4.3–7.7) | 0.896 | |

| 5 | 4.8 (4.0–5.5) | 5.1 (4.1–5.5) | 0.181 | |

| 6 | 2.7 (2.3–3.4) | 2.7 (2.3–3.2) | 0.592 | |

| 7 | 2.3 (1.9–2.8) | 2.2 (1.7–2.8) | 0.062 | |

| 8 | 4.3 (3.8–5.0) | 4.4 (3.6–5.2) | 0.598 | |

| 9 | 4.4 (2.4–8.2) | 4.4 (2.5–7.7) | 0.845 | |

| 10 | 2.1 (1.0–3.2) | 1.8 (0.9–3.0) | 0.377 | |

| 11 | 3.7 (2.5–4.9) | 3.5 (2.3–5.0) | 0.679 | |

| 12 | 0.9 (0.5–1.3) | 0.9 (0.6–1.4) | 0.745 | |

| 13 | 1.2 (0.9–1.5) | 1.3 (1.0–1.5) | 0.325 | |

| 14 | 1.2 (1.0–1.5) | 1.2 (0.9–1.4) | 0.468 | |

| 15 | 2.1 (1.7–2.3) | 2.0 (1.6–2.5) | 0.482 | |

| 16 | 1.3 (1.0–1.7) | 1.3 (1.0–1.7) | 0.800 | |

| 17 | 3.3 (2.7–4.2) | 3.1 (2.6–3.5) | 0.001 | |

| 18 | 2.2 (1.7–2.6) | 2.2 (1.8–2.6) | 0.937 | |

| 19 | 2.5 (2.0–3.0) | 2.5 (2.0–2.9) | 0.806 | |

| 20 | 2.7 (2.1–3.3) | 2.7 (2.3–3.2) | 0.615 | |

| 21 | 15.6 (13.6–17.8) | 15.3 (13.9–16.8) | 0.511 | |

| 22 | 2.5 (2.0–3.1) | 2.6 (2.1–3.2) | 0.425 | |

| 23 | 4.3 (3.5–5.1) | 4.3 (3.5–5.0) | 0.983 | |

| 24 | 1.7 (1.2–2.5) | 1.8 (1.3–2.5) | 0.449 | |

| Average | 4.0 (3.6–4.3) | 3.9 (3.6–4.2) | 0.277 | |

| CDKN2B | 1 | 5.5 (4.5–6.4) | 5.2 (4.2–6.1) | 0.046 |

| 2 | 4.4 (3.4–5.3) | 4.3 (3.3–5.2) | 0.395 | |

| 3 | 3.8 (3.1–4.9) | 4.0 (3.1–4.6) | 0.890 | |

| 4 | 4.2 (3.4–5.1) | 4.1 (3.3–4.8) | 0.233 | |

| 5 | 7.6 (6.6–8.9) | 7.2 (6.3–8.1) | 0.002 | |

| 6 | 6.9 (5.7–8.2) | 6.5 (5.3–7.4) | 0.009 | |

| 7 | 8.3 (7.1–9.6) | 7.5 (6.7–8.2) | <0.001 | |

| 8 | 3.5 (2.9–4.2) | 3.3 (2.9–3.7) | 0.039 | |

| 9 | 4.0 (3.3–4.5) | 3.6 (3.0–4.1) | <0.001 | |

| 10 | 6.1 (5.2–7.1) | 5.6 (4.6–6.3) | <0.001 | |

| 11 | 7.5 (6.3–8.7) | 6.8 (6.0–7.8) | 0.007 | |

| 12 | 5.7 (4.9–6.7) | 5.4 (4.6–6.0) | 0.009 | |

| Average | 5.7 (5.0–6.4) | 5.4 (4.7–5.9) | 0.001 | |

Statistically signficant values are in italics

For each CpG site, p < 0.05/36 after Bonferroni correction, and p < 0.025 for average levels

Table 3.

Methylation levels of CDKN2A/2B according to severity of CarAC

| Gene | Without (n = 135) | Mild (n = 103) | Sever (n = 84) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CDKN2A | 3.9 (3.6–4.2) | 4.0 (3.6–4.4) | 4.0 (3.6–4.2) | 0.189 |

| CDKN2B | 5.4 (4.7–5.9) | 5.6 (4.8–6.2) | 5.9 (5.2–6.6) | <0.001 |

Statistically signficant values are in italics

Table 4.

Association between methylation levels of CDKN2A/2B and cube root transformed calcification scores/calcium volumes

| Agatston score | Calcium volume | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | SE | p value | β | SE | p value | |

| Model 1 | ||||||

| CDKN2A | 0.013 | 0.325 | 0.968 | 0.032 | 0.302 | 0.915 |

| Age | 0.108 | 0.016 | <0.001 | 0.101 | 0.015 | <0.001 |

| Sex | 0.566 | 0.461 | 0.219 | 0.556 | 0.429 | 0.194 |

| BMI | −0.136 | 0.064 | 0.034 | −0.130 | 0.059 | 0.029 |

| HTN | 1.173 | 0.429 | 0.006 | 1.084 | 0.399 | 0.007 |

| DM | 0.844 | 0.377 | 0.025 | 0.792 | 0.351 | 0.024 |

| Smoking | 0.654 | 0.404 | 0.105 | 0.599 | 0.375 | 0.111 |

| Model 2 | ||||||

| CDKN2B | 0.591 | 0.172 | 0.001 | 0.533 | 0.160 | 0.001 |

| Age | 0.078 | 0.018 | <0.001 | 0.074 | 0.017 | <0.001 |

| Sex | 0.433 | 0.451 | 0.338 | 0.437 | 0.420 | 0.299 |

| BMI | −0.127 | 0.062 | 0.042 | −0.122 | 0.058 | 0.036 |

| HTN | 1.348 | 0.420 | 0.001 | 1.240 | 0.392 | 0.002 |

| DM | 0.750 | 0.367 | 0.041 | 0.704 | 0.342 | 0.039 |

| Smoking | 0.746 | 0.392 | 0.057 | 0.678 | 0.365 | 0.063 |

Statistically signficant values are in italics

Generalized liner model was adjusted for age, sex, BMI, HTN, DM and smoking

Discussion

In this study, we observed a positive correlation between CDKN2B methylation and CarAC, which was quantified by Agatston score and calcium volume. These results verified our hypothesis that DNA methylation in CDKN2B may increase the susceptibility of artery calcification.

The relationship between Chr9p21 variants and artery calcification has been established previously [9, 23, 24]. Chr9p21 variants may up-regulate the expression of ANRIL, which was negatively correlated with the expression of CDKN2B [25]. ANRIL can recruit and bind epigenetic modifiers such as polycomb repressor complex to promoter regions of adjacent genes [12, 15, 26]. These epigenetic regulations may eventually influence DNA methylation of CDKN2B. Methylation occurred in CpG islands around promoter regions generally inhibits gene expression [27]. CDKN2B, known as a tumor suppressor, participates in cell cycle regulation via retinoblastoma (Rb) pathway [28]. The protein p15INK4b, encoded by CDKN2B, can specifically bind to CDKN4 and CDKN6, resulting in G1 phase arrest and blockage of cell proliferation [8]. The viewpoint that CDKN2B methylation may lead to unlimited cell proliferation has been verified in a spectrum of cancers [29, 30].

Chronic vascular inflammation arising from atherosclerosis contributes to calcification [6]. Repression of CDKN2B may result in losing control of Rb proteins, which may subsequently enhance the proliferation of macrophage [12]. In the condition of imbalance between promotion and inhibition of calcification, a proportion of VSMCs tend to differentiate into an osteoblastic and proliferative phenotype [31–33]. These processes play a role in the progression of arterial calcification. Therefore, methylation at CDKN2B may be a substantial contributor to artery calcification. And the possible association of CDKN2B methylation and atherosclerosis can be further extrapolated to patients with CAD or other cardiovascular diseases.

Our study has several strengths. To the best of our knowledge, this study was the first to report the association between CDKN2B methylation status and CarAC. CarAC was quantified by both Agatston method and calcium volume. Considering its less invasiveness and simplicity, methylation tests may be used in clinical settings for predicting the artery calcification. There are potential treatment implications. CpG island hypermethylation has been targeted in cancer treatment, with pharmacological agents modifying the epigenetic mechanisms been studied intensively [30]. Similarly, agents which can specifically regulate CDKN2B methylation may be used for preventing artery calcification in future.

There are several limitations in our study. Firstly, the nature of the cross-sectional study limited us to reach a causal relationship. Secondly, the CDKN2A/2B expression was not evaluated in this study due to lack of fresh leukocytes. Further functional studies are warranted to clarify the underlying mechanisms that correlate CDKN2B methylation with artery calcification. Third, given the varied predisposition of DNA methylation in different tissues, methylation measured from leukocytes may not represent that of arterial wall. But considering that monocyte-derived macrophages, lymphocytes and platelets from peripheral blood are involved in atherogenesis [34], and harvesting vascular tissue from human body is largely impractical, the research strategy used in this study is logical and rational. Fourth, the present study was conducted in patients with ischemic stroke, which may generate selection bias. Not all potential confounders can be collected and analyzed due to the limited sample size and study resource. Moreover, patients with history of carotid artery stenting were excluded for accurate calcification assessment, which may lead to selection bias.

Conclusions

In summary, CDKN2B methylation is associated with CarAC independent of major cardiovascular risk factors. Our findings may enrich the body of knowledge on epigenetic pathology and provide some new implications for prevention and treatment of atherosclerotic diseases.

Authors’ contributions

SZ and GX conceived and designed the experiments, and wrote the draft of the manuscript; LW and YZ assessed the calcification scores; YZ and SZ collected data; SZ and BC undertook the statistical analyses; SZ, BC, YZ, KL and HZ performed laboratory experiments; ZZ, LS, XX, MD and HC gave critical comments on the draft and contributed to the manuscript writing; GX, GL and XL reviewed clinical assessments in this study and supervised this study. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

We thank all patients for participating in this study. We are also grateful to Center for Genetics & Genomic Analysis, Genesky Biotechnologies Inc. (Shanghai, 201203) for their technical support in sequencing.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Availability of data and materials

The data will not be shared, since part of the data is being reused by another study.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was approved by the Ethical Review Board of Jinling Hospital. Written informed consent was obtained from all enrolled patients.

Funding

This work was financially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC, # 81571143 to GX, # 81530038 to XL and # 81220108008 to XL).

Abbreviations

- ANRIL

antisense noncoding RNA in the INK4 locus

- BMI

body mass index

- BSAS

BiSulfite Amplicon Sequencing

- CarAC

carotid artery calcification

- CAD

coronary artery disease

- CDKN2A/2B

cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor 2A/2B

- Chr9p21

chromosome 9p21

- CTA

computed tomography angiography

- DM

diabetes mellitus

- HDL

high-density lipoprotein

- HTN

hypertension

- HU

Hounsfield units

- LDL

low-density lipoprotein

- Rb

retinoblastoma

- TC

total cholesterol

- TG

triglyceride

- TSS

transcriptional start site

- VSMC

vascular smooth muscle cell

Additional file

Additional file 1: Table S1. Primer sequences for CDKN2A/2B genes (start and end site were named as its relative distance to transcriptional start site). Table S2. Methylated CpG sites identified in this study. Table S3. Distribution of methylation levels (%) of 36 CpG sites in CDKN2A/2B genes. Table S4. Spearman pairwise correlations for CpG sites of CDKN2A. Table S5. Spearman pairwise correlations for CpG sites of CDKN2B.

Contributor Information

Shuyu Zhou, Email: liuchuanf@126.com.

Yumeng Zhang, Email: yumengzhang_nju@126.com.

Li Wang, Email: rubyli870613@126.com.

Zhizhong Zhang, Email: zhizhongn@gmail.com.

Biyang Cai, Email: livart.cby@gmail.com.

Keting Liu, Email: lkt921110@gmail.com.

Hao Zhang, Email: zh_hao@163.com.

Minhui Dai, Email: daiminhui07@163.com.

Lingli Sun, Email: sunlingliy@163.com.

Xiaomeng Xu, Email: xuxiaomeng@163.com.

Huan Cai, Email: ch.neurol@gmail.com.

Xinfeng Liu, Email: xfliu2@vip.163.com.

Guangming Lu, Email: cjr.luguangming@vip.163.com.

Gelin Xu, Email: gelinxu@nju.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Pursnani A, Massaro JM, D’Agostino RB, Sr, et al. Guideline-based statin eligibility, coronary artery calcification, and cardiovascular events. JAMA. 2015;314:134–141. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.7515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Friedlander AH, El Saden SM, Hazboun RC, et al. Detection of carotid artery calcification on the panoramic images of post-menopausal females is significantly associated with severe abdominal aortic calcification: a risk indicator of future adverse vascular events. Dentomaxillofac Radiol. 2015;44:20150094. doi: 10.1259/dmfr.20150094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Allison MA, Hsi S, Wassel CL, et al. Calcified atherosclerosis in different vascular beds and the risk of mortality. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2012;32:140–146. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.111.235234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Elias-Smale SE, Odink AE, Wieberdink RG, et al. Carotid, aortic arch and coronary calcification are related to history of stroke: the Rotterdam Study. Atherosclerosis. 2010;212:656–660. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2010.06.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rutsch F, Nitschke Y, Terkeltaub R. Genetics in arterial calcification: pieces of a puzzle and cogs in a wheel. Circ Res. 2011;109:578–592. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.111.247965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Demer LL, Tintut Y. Inflammatory metabolic, and genetic mechanisms of vascular calcification. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2014;34:715–723. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.113.302070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ye S, Willeit J, Kronenberg F, et al. Association of genetic variation on chromosome 9p21 with susceptibility and progression of atherosclerosis: a population-based, prospective study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;52:378–384. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.11.087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Holdt LM, Teupser D. Recent studies of the human chromosome 9p21 locus, which is associated with atherosclerosis in human populations. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2012;32:196–206. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.111.232678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.O’Donnell CJ, Kavousi M, Smith AV, et al. Genome-wide association study for coronary artery calcification with follow-up in myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2011;124:2855–2864. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.974899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jarinova O, Stewart AF, Roberts R, et al. Functional analysis of the chromosome 9p21.3 coronary artery disease risk locus. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2009;29:1671–1677. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.109.189522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Motterle A, Pu X, Wood H, et al. Functional analyses of coronary artery disease associated variation on chromosome 9p21 in vascular smooth muscle cells. Hum Mol Genet. 2012;21:4021–4029. doi: 10.1093/hmg/dds224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hannou SA, Wouters K, Paumelle R, et al. Functional genomics of the CDKN2A/B locus in cardiovascular and metabolic disease: what have we learned from GWASs? Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2015;26:176–184. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2015.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pechlivanis S, Muhleisen TW, Mohlenkamp S, et al. Risk loci for coronary artery calcification replicated at 9p21 and 6q24 in the Heinz Nixdorf Recall Study. BMC Med Genet. 2013;14:23. doi: 10.1186/1471-2350-14-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim DS, Smith JA, Bielak LF, et al. The relationship between diastolic blood pressure and coronary artery calcification is dependent on single nucleotide polymorphisms on chromosome 9p21.3. BMC Med Genet. 2014;15:89. doi: 10.1186/s12881-014-0089-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zaina S. Unraveling the DNA methylome of atherosclerosis. Curr Opin Lipidol. 2014;25:148–153. doi: 10.1097/MOL.0000000000000059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhuang J, Peng W, Li H, et al. Methylation of p15INK4b and expression of ANRIL on chromosome 9p21 are associated with coronary artery disease. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e47193. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0047193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liu X, Xu G, Wu W, Zhang R, Yin Q, Zhu W. Subtypes and one-year survival of first-ever stroke in Chinese patients: The Nanjing Stroke Registry. Cerebrovasc Dis (Basel, Switzerland) 2006;22:130–136. doi: 10.1159/000093241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lu L, Zhang LJ, Poon CS, et al. Digital subtraction CT angiography for detection of intracranial aneurysms: comparison with three-dimensional digital subtraction angiography. Radiology. 2012;262:605–612. doi: 10.1148/radiol.11110486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pham PH, Rao DS, Vasunilashorn F, et al. Computed tomography calcium quantification as a measure of atherosclerotic plaque morphology and stability. Invest Radiol. 2006;41:674–680. doi: 10.1097/01.rli.0000233325.42572.08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Masser DR, Berg AS, Freeman WM. Focused, high accuracy 5-methylcytosine quantitation with base resolution by benchtop next-generation sequencing. Epigenetics Chromatin. 2013;6:33. doi: 10.1186/1756-8935-6-33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Subedi D, Zishan US, Chappell F, et al. Intracranial carotid calcification on cranial computed tomography: visual scoring methods, semiautomated scores, and volume measurements in patients with stroke. Stroke. 2015;46:2504–2509. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.115.009716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wilson D, Charidimou A, Shakeshaft C, et al. Volume and functional outcome of intracerebral hemorrhage according to oral anticoagulant type. Neurology. 2016;86:360–366. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000002310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pechlivanis S, Scherag A, Muhleisen TW, et al. Coronary artery calcification and its relationship to validated genetic variants for diabetes mellitus assessed in the Heinz Nixdorf recall cohort. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2010;30:1867–1872. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.110.208496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang Y, Wang L, Zhang Z, et al. Shared and discrepant susceptibility for carotid artery and aortic arch calcification: a genetic association study. Atherosclerosis. 2015;241:371–375. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2015.05.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Johnson AD, Hwang SJ, Voorman A, et al. Resequencing and clinical associations of the 9p21.3 region: a comprehensive investigation in the Framingham heart study. Circulation. 2013;127:799–810. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.111559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Popov N, Gil J. Epigenetic regulation of the INK4b-ARF-INK4a locus: in sickness and in health. Epigenetics. 2010;5:685–690. doi: 10.4161/epi.5.8.12996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Portela A, Esteller M. Epigenetic modifications and human disease. Nat Biotechnol. 2010;28:1057–1068. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gil J, Peters G. Regulation of the INK4b-ARF-INK4a tumour suppressor locus: all for one or one for all. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2006;7:667–677. doi: 10.1038/nrm1987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Herman JG, Baylin SB. Gene silencing in cancer in association with promoter hypermethylation. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:2042–2054. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra023075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Esteller M. CpG island hypermethylation and tumor suppressor genes: a booming present, a brighter future. Oncogene. 2002;21:5427–5440. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Doherty TM, Asotra K, Fitzpatrick LA, et al. Calcification in atherosclerosis: bone biology and chronic inflammation at the arterial crossroads. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:11201–11206. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1932554100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Johnson RC, Leopold JA, Loscalzo J. Vascular calcification: pathobiological mechanisms and clinical implications. Circ Res. 2006;99:1044–1059. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000249379.55535.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhu D, Mackenzie NC, Farquharson C, et al. Mechanisms and clinical consequences of vascular calcification. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2012;3:95. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2012.00095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wierda RJ, Geutskens SB, Jukema JW, et al. Epigenetics in atherosclerosis and inflammation. J Cell Mol Med. 2010;14:1225–1240. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2010.01022.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data will not be shared, since part of the data is being reused by another study.