Abstract

Background

Therapeutic antibodies against programmed death receptor 1 (PD-1) are considered front-line therapy in metastatic melanoma. The efficacy of PD-1 blockade for patients with biologically distinct melanomas arising from acral and mucosal surfaces has not been well described.

Methods

A multi-institutional retrospective cohort analysis identified adults with advanced acral and mucosal melanoma treated with nivolumab or pembrolizumab as standard clinical practice, via expanded access programs, or published prospective trials. Objective responses were determined utilizing investigator-assessed Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST) 1.1. Progression-free (PFS) and overall survival (OS) were assessed using Kaplan-Meier methods.

Results

60 individuals were identified; 25 (42%) with acral and 35 (58%) with mucosal melanoma. Fifty-one (85%) patients had received prior therapy, including 77% with prior ipilimumab. Forty patients (67%) received pembrolizumab at 2mg/kg or 10mg/kg and 20 (33%) received nivolumab at 1mg/kg or 3mg/kg every 2–3 weeks. ORR (95% confidence interval, CI) was 32% (15–54%) in acral and 23% (10–40%) in mucosal melanoma. After a median follow up of 20 months in acral and 10.6 months in mucosal, median PFS was 4.1 months and 3.9 months, respectively. Only two patients (3%) discontinued treatment due to toxicity.

Conclusions

Response rates to PD-1 blockade in patients with acral and mucosal melanomas were comparable to published rates in cutaneous melanoma and support the routine use of PD-1 blockade in clinical practice. Further investigation is needed to identify the mechanisms of response and resistance to therapy in these subtypes.

Keywords: acral melanoma, mucosal melanoma, immunotherapy, anti-PD-1, nivolumab, pembrolizumab

Introduction

Malignant melanomas encompass a genetically heterogeneous group of neoplasms diagnosed in 74,000 people in the United States each year and resulted in approximately 10,000 deaths in 2015.1 Although melanomas most commonly arise from melanocytes in the basal layer of the epidermis (cutaneous melanoma), they can also originate from melanocytes situated within the mucosal surfaces of the body (mucosal melanoma), glabrous skin, including the palms of the hands or the soles of the feet (acral melanoma), or the uveal tract of the eye.2–5 Mucosal and acral melanomas comprise less than 10% of all newly diagnosed cases in the US each year; they have distinct genetic and clinical characteristics,6, 7 lower somatic mutational burden,8, 9 and poorer prognosis than stage-matched cutaneous melanomas.10, 11

Historically, the prognosis of all patients with unresectable or metastatic melanoma was poor, with a 5-year survival rate as low as 6%.12 Over the past 5 years, however, treatment of cutaneous melanoma has been revolutionized by targeted therapy against mutant BRAF and immune-checkpoint inhibitors expressed on T lymphocytes and other immune cells that enhance anti-tumor immunity. Thus far, three agents that block immune checkpoint molecules have been approved by the FDA to treat patients with advanced melanoma: ipilimumab (Bristol-Myers Squibb, New York, NY), a monoclonal antibody against cytotoxic T-lymphocyte associated protein 4 (CTLA-4), the anti- programmed cell death receptor 1 (PD-1) agents pembrolizumab (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) and nivolumab (BMS, New York, NY), as well as the combination of ipilimumab plus nivolumab. Across different trials, PD-1 blockade with either nivolumab or pembrolizumab resulted in response rates of approximately 26%–44% when used as single agents13–19 and significantly improved overall survival (OS) in comparison to ipilimumab and dacarbazine.17, 20

Due to their rarity, acral and mucosal melanomas were not reported separately from most clinical trials accruing patients with advanced melanoma. Consequently, despite the routine clinical use of PD1 blockade, less is known about the efficacy for these specific subtypes. Recent data investigating the efficacy of immune-checkpoint inhibition in cutaneous melanoma, non-small cell lung cancer, and microsatellite unstable colorectal and gynecologic carcinomas suggest that tumors with a higher mutational burden are more likely to respond to these therapies.21–24 Given the lower somatic mutation rates of acral and mucosal melanomas versus cutaneous melanomas, we hypothesized that the efficacy of immune checkpoint blockade may be lower in these subgroups.

To investigate the efficacy of PD-1 blockade in these less common subtypes of melanoma, we assembled a retrospective, multicenter cohort of patients with advanced or unresectable mucosal or acral melanoma treated with the anti-PD-1 agents nivolumab or pembrolizumab as standard therapy (after FDA approval), via expanded access programs, or on published clinical trials.

Materials & Methods

Study population

Following approval by Institutional Review Boards at each site, patients 18 years or older with advanced acral or mucosal melanoma treated with at least 1 dose of nivolumab or pembrolizumab were identified using electronic databases and data query systems of participating institutions (Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (n=29), Dana-Farber Cancer Institute (n=8), Vanderbilt University Medical Center (n=8), Massachusetts General Hospital (n=3), University of California at San Francisco (n=6), Georgetown University Medical Center (n=5), and the University of Chicago (n=1)). Patients were included in this study if they received pembrolizumab or nivolumab between 1/1/2010 and 4/1/2015 either as standard clinical practice following approval by the FDA, via an Expanded Access Program (EAP), NCT02083484, or another published clinical trial (NCT0129582713; NCT01295827;25 NCT01927419;26 NCT01024231;27 NCT01721746).19

Relevant clinical data were retrieved from electronic medical records including: sex; age, stage, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status, and sites of metastatic disease at anti-PD1 treatment initiation; presence of BRAF, NRAS, and KIT mutations; number and characteristics of prior and subsequent systemic therapies; treatment-related variables (anti-PD-1 agent used, duration of treatment, reason for discontinuation, toxicities), and survival status. Toxicities were retrieved from medical records and graded according to the National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events, version 4.03 if attributed to anti-PD-1 therapy.

Efficacy assessment and statistical considerations

The primary objective of this study was to determine the objective response rate (ORR) of patients with acral and mucosal melanoma treated with anti-PD-1 agents. Radiologic response was assessed according to the Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST) v1.1, [30] determined by a study-participating reference radiologist at each site for those patients enrolled in a non-EAP prospective clinical trial. For patients treated with commercially available drug or via the pembrolizumab EAP, local investigators interpreted responses using RECIST 1.1 with the exception that confirmation scans were not required for objective responses. ORR was defined as the proportion of patients achieving a complete response (CR) or partial response (PR). Patients who received one or more doses of therapy without subsequent radiographic evaluation were considered to have progressive disease (PD).

Baseline and treatment characteristics are presented by frequencies and percentages for categorical variables and median and range for continuous variables and were analyzed using descriptive statistics. Progression Free Survival (PFS) was calculated from date of anti-PD-1 treatment initiation to radiologic progression, change in therapy, death or last follow up. Overall survival (OS) was estimated from date of anti-PD-1 treatment initiation to date of death from any cause or last follow up. Patients alive at last follow up were censored. PFS and OS were estimated using the Kaplan-Meier method and expressed as median values with two-sided 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Log-rank test was used for comparisons between categorical variables and the Score test for continuous variables. Univariate analyses were performed for factors influencing PFS and OS. P-values < 0.05 were considered significant. All analysis was done using R version 3.1.1.

Results

Demographics and clinical characteristics at baseline

A total of 60 patients treated with anti-PD-1 agents were identified: 35 (58%) with tumors arising from mucosal sites and 25 (42%) from acral sites. Median age at time of PD-1 blockade therapy for the entire cohort was 64 years (range: 35 – 94). The cohort was 55% female overall. Thirty-five patients (58%) had stage IV-M1c disease at the time of PD-1 treatment; central nervous system (CNS) involvement was present in 9 patients (15%). Among patients with mucosal melanoma, 40% arose from vulvovaginal, 34% from anorectal, and 26% from head and neck mucosal sites. Demographic details are described in Table 1. An alteration in BRAF, KIT or NRAS was identified in 17 out of 52 tumors (33%) tested for at least one genomic aberration (BRAF n=2; KIT n=5; NRAS n=10); see Supplemental Table 1 for detailed mutational data. Fifty-one patients (85%) had received prior systemic treatments; median number of prior therapies was 1 (range 0–5). Forty-six patients (77%) received ipilimumab, of which 9 (20%) achieved disease stability (n=4) or antitumor response (n=5).

Table 1.

Demographics and clinical characteristics

| Variable | Number (%)

|

p-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Acral | Mucosal | ||

|

| ||||

| Number of patients | 60 | 25 | 35 | |

|

| ||||

| Age at PD-1 Treatment, | 0.85 | |||

| Median (range) | 64 (35–94) | 64 (35–94) | 65 (37–89) | |

|

| ||||

| Sex | 0.02 | |||

| Female | 33 (55) | 9 (36) | 24 (69) | |

| Male | 27 (45) | 16 (64) | 11 (31) | |

|

| ||||

| ECOG at treatment initiation | 1 | |||

| 0 | 30 (50) | 12 (48) | 18 (51) | |

| ≥1 | 30 (50) | 13 (52) | 17 (49) | |

|

| ||||

| Site | -- | |||

| Hand/foot | 18 (30) | 18 (72) | - | |

| Nailbed | 3 (5) | 3 (12) | - | |

| Anorectal | 12 (20) | - | 12 (34) | |

| Vulvovaginal | 14 (23) | - | 14 (40) | |

| Head/neck | 9 (15) | - | 9 (26) | |

| Unknown* | 4 (7) | 4 (16) | - | |

|

| ||||

| Stage at treatment | 0.11 | |||

| III | 6 (10) | 5 (20) | 1 (3) | |

| IV – M1A | 8 (13) | 4 (16) | 4 (11) | |

| IV – M1B | 11 (18) | 5 (20) | 6 (17) | |

| IV – M1C | 35 (58) | 11 (44) | 24 (69) | |

|

| ||||

| Brain metastases | 1 | |||

| Yes | 9 (15) | 4 (16) | 5 (14) | |

| No | 51 (85) | 21 (84) | 30 (86) | |

|

| ||||

| Liver metastases | 0.053 | |||

| Yes | 18 (30) | 4 (16) | 14 (40) | |

| No | 42 (70) | 21 (84) | 21 (60) | |

|

| ||||

| Mutations | 0.02 | |||

| BRAF | 2 (3) | 2 (8) | 0 | |

| KIT | 5 (8) | 3 (12) | 2 (6) | |

| NRAS | 10 (16) | 6 (24) | 4 (11) | |

| Wild type** | 35 (58) | 9 (36) | 26 (74) | |

| NA | 8 (13) | 5 (20) | 3 (9) | |

|

| ||||

| Prior systemic therapy*** | 0.28 | |||

| Yes | 51 (85) | 23 (92) | 28 (80) | |

| No | 9 (15) | 2 (8) | 7 (20) | |

|

| ||||

| Prior Ipilimumab | 0.76 | |||

| Yes | 46 (77) | 20 (80) | 26 (74) | |

| No | 14 (23) | 5 (20) | 9 (26) | |

|

| ||||

| Response to Ipilimumab**** | 0.03 | |||

| POD | 37 (80) | 13 (65) | 24 (92) | |

| PR or SD | 9 (20) | 7 (35) | 2 (8) | |

NA – not assessed /

precise description of primary site missing or not available /

for at least one of BRAF, KIT or NRAS / POD – progression of disease / / PR – partial response / SD – stable disease /

prior systemic therapy for advanced disease, which included:ipilimumab (n=46), IL-2 (n=6 ), cytotoxic chemotherapy (n=7), interferon + cisplatin (n=1), trametinib (n=1), other (n=3) /

among those who had prior ipilimumab

Treatment details

Nivolumab was administered in 20 patients (n=8 acral, n=12 mucosal), all of which were participants in clinical trials. Ten of 20 patients received standard 3mg/kg IV dosing every 2 weeks; the remainder had doses ranging from 0.3 mg/kg to 10 mg/kg IV every 2–3 weeks. Pembrolizumab was administered in 40 patients (n=17 acral, n=23 mucosal). The standard dosing of 2mg/kg every 3 weeks was received by 34 (85%) of patients; the remainder (15%) received 10mg/kg every 2–3 weeks.

Overall, 28 (47%) patients received treatment as a part of a clinical trial and 32 (53%) via commercial drug or an Expanded Access Program. The median number of doses administered was 6 (range: 1–52) and the median time on treatment was 3.4 months (range: 0.7–37.5 months). Treatment details according to each specific subtype are summarized in Supplemental Table 2. Information regarding subsequent treatment after progression on anti-PD-1 therapy was available for 59 of 60 patients. Twenty-eight (47%) received at least 1 additional systemic therapy. Seventeen patients (29%) received at least 1 cytotoxic therapy. Twelve patients (20%) received at least 1 immune-based therapy, most commonly ipilimumab (n=9; 15%) or a standard anti-PD-1 agent (n=4; 7%), including two patients initially treated with nivolumab that subsequently received pembrolizumab, one patient treated with pembrolizumab who subsequently received nivolumab and one patient who was re-challenged with pembrolizumab.

Efficacy analyses

Objective Response Rate

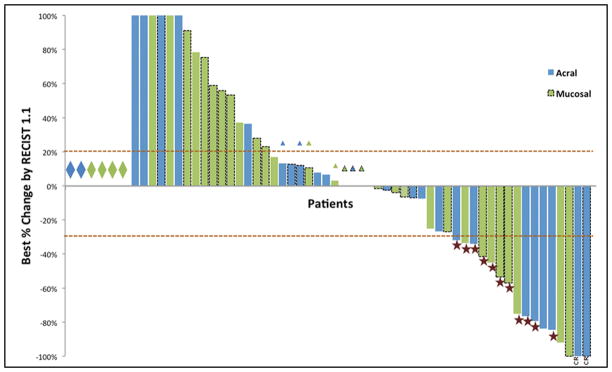

Treatment outcomes are summarized in Table 2. For acral melanoma, 2 patients had a CR and 6 had a PR, for an ORR of 32% (95% CI: 15–54%). For mucosal melanoma, the ORR was 23% (95% CI: 10–40%). PD was the best response for 40% of patients with acral melanomas (95% CI: 21–61%) and 57% of patients with mucosal melanomas (95% CI: 39–74%). The changes in disease burden from baseline are illustrated in Figure 1.

Table 2.

Treatment outcomes

| Outcome | Number (%) | |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Acral (n=25) | Mucosal (n=35) | |

|

| ||

| Best response* | ||

| CR | 2 (8) | 0 |

| PR | 6 (24) | 8 (23) |

| SD | 7 (28) | 7 (20) |

| POD | 10 (40) | 20 (57) |

|

| ||

| ORR (95% CI) | 32% (15 – 54) | 23% (10 – 40) |

|

| ||

| mDoR - months (range) | 14.7 (3.7 – 44.0+) | 12.9 (2.1 – 15.9) |

|

| ||

| mPFS – months | 4.1 | 3.9 |

|

| ||

| mOS - months | 31.7 | 12.4 |

assessed by RECIST v1.1 / CR – complete response / PR – partial response / SD – stable diseae / POD – progressios of disease / ORR – objective response rate / mPFS – median progression free survival / mOS – median overall survival / mDoR – median duration of response

Figure 1.

Waterfall plot of objective response for n=60 patients with primary acral (blue) and mucosal (green) melanoma by RECIST 1.1. Diamonds indicate patients who clinically progressed without a repeat radiographic assessment (n=6). Triangles indicate best response was progressive disease due to growth in non-target lesions. Stars indicate partial responses (n=14) and CR indicates a complete response (n=2). Dashed outlines indicate investigator-assessed responses (n=26). Percent changes greater than 100% are truncated.

Among the 16 patients whose tumors had a PR or CR, 8 have progressed (50%) during evaluable follow up. After a median follow up of 26 months, median duration of response was 14.7 months (range: 3.7–44+ months) for patients with acral and 12.9 months (range: 2.1–15.9 months) for patients with mucosal melanoma. There were no objective responses among 4 patients re-challenged with anti-PD1 therapy following progression on prior pembrolizumab or nivolumab. On univariate analysis, no variables were associated with response for either acral or mucosal melanomas (Supplemental Tables 3 and 4). Among the 17 patients whose tumors had a known driver in BRAF, NRAS, or KIT, 4/10 patients with NRAS mutations responded to PD-1 blockade versus 0/5 and 0/2 with KIT or BRAF, respectively. This was not statistically significant (p=0.41).

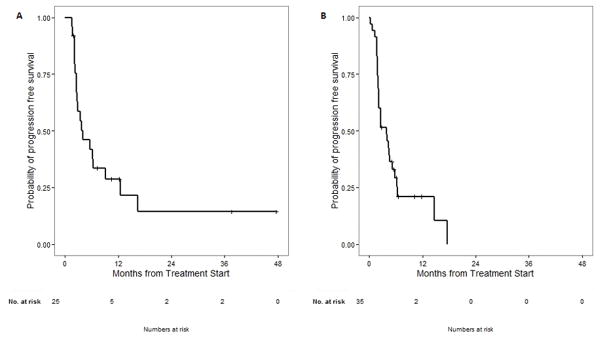

Progression Free Survival

The status of progression was known in 59/60 patients (98%). The majority of patients (74%) experienced progression of disease, whereas 8 patients (13%) remained on PD-1 blockade without progression. Patients with acral melanoma had a median PFS of 4.1 months with a median follow up of 20 months. Patients with mucosal melanoma had a median PFS of 3.9 months with a median follow up of 10.6 months (see Figure 2). On univariate analysis, there was no significant association between primary subsite, mutation status, stage at treatment, CNS or liver involvement, prior therapy, or response to prior ipilimumab with PFS in either acral or mucosal subtypes (Supplemental Tables 5 and 6).

Figure 2.

Median progression-free survival from time of anti-PD1 therapy. (A) Median PFS in patients with acral melanoma is 4.1 months with a median follow up of 20 months. (B) Median PFS in patients with mucosal melanoma is 3.9 months with a median follow up of 10.6 months.

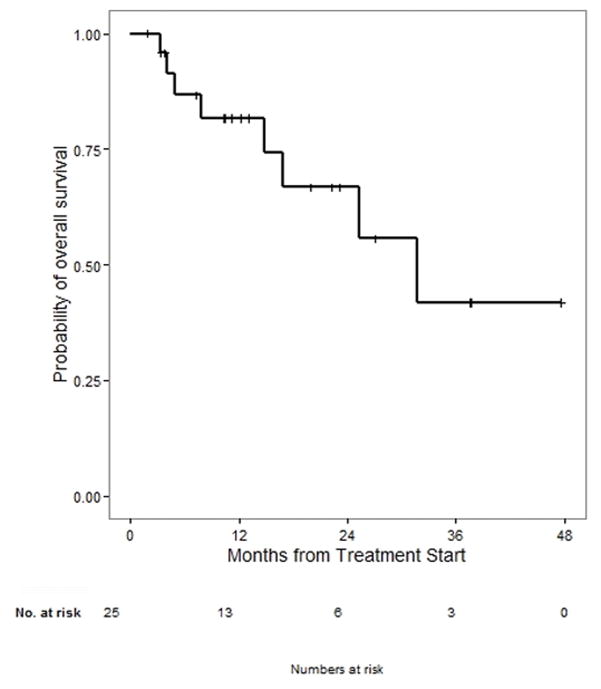

Overall Survival

Across the entire cohort, 25 of 60 patients died. After a median follow up of 20 months, the median OS for those with acral primary was 31.7 months (see Figure 3). There was no significant association with age, sex, mutation status, CNS/liver involvement, or prior therapy outcomes in acral subtypes (Supplemental Table 7). Given the median follow up of 10.6 months in patients with mucosal primary, OS data are not mature enough to report.

Figure 3.

Median overall survival from time of anti-PD1 therapy in patients with acral melanoma is 31.7 months with a median follow up of 20 months. Follow-up was not mature enough to report median OS in patients with mucosal melanoma.

Toxicity

Across the entire cohort, 31/60 patients (51%) had at least 1 adverse event (AE) attributable to anti-PD-1. The majority (81%) of AEs were Grade 1 or 2. Overall, the most common AEs were fatigue (n=16), rash (n=6), and hepatitis (n=5). No patients in this cohort were diagnosed with pneumonitis. Grade 3 or 4 AEs included Grade 4 hemolytic anemia (n=1), Grade 3 hepatitis (n=2), retinopathy (n=1), hyperglycemia (n=1), and tenosynovitis/arthralgias (n=1). Two patients (3%) discontinued treatment due to toxicity (Grade 3 arthralgias and Grade 3 retinopathy). There were no treatment-related deaths.

Discussion

Acral and mucosal melanomas are epidemiologically and molecularly distinct from non-acral cutaneous melanoma,6–9 but limited evidence exists to support the efficacy of immune checkpoint blockade with anti-PD-1 agents in this setting. This cohort represents to our knowledge the first published report of patients with acral melanoma treated with nivolumab or pembrolizumab, and one of the first including patients with mucosal melanoma. In a largely second line setting, we found that response rate was similar in both acral (32%) and mucosal (23%) groups. This ORR in mucosal melanoma is numerically identical to the 23% ORR in 86 patients with mucosal melanoma treated across multiple prospective trials of nivolumab, although this may be influenced by an overlap of 7 patients included in both cohorts.28 These response rates in mucosal and acral melanoma are also in line with prior published response rates in 2nd line cutaneous melanoma trials of PD-1 blockade with nivolumab or pembrolizumab of 26–31%.15, 16, 18

Our analysis of this cohort could not detect a difference in ORR by age, subsite, site of metastasis, or prior therapy. Treatment was well tolerated, with only 2 of 60 patients discontinuing therapy due to toxicity. Therefore, these data support the routine use of PD-1 blockade for advanced or unresectable acral and mucosal melanoma regardless of age, site of primary or metastatic disease, or response to prior therapy. Extrapolating from the ORRs in treatment-naïve versus ipilimumab-refractory cutaneous melanoma, one could reasonably expect the efficacy in a treatment-naïve cohort to be even higher than is reported in this majority (85%) pre-treated population. Parallels to biochemotherapy in mucosal melanoma can be drawn, where ORRs were 36–54% in smaller, heterogeneously treated series that demonstrated durable responses in some patients.29–31 Given the fact that PD-1 blockade is generally understood to be better tolerated than biochemotherapy and has demonstrated an OS benefit in cutaneous melanomas, this report supports the use of anti-PD-1 based therapy in the frontline setting for acral and mucosal melanomas.

We acknowledge that the major limitations of this analysis are that it is retrospective in nature and represents a pooled analysis of varying doses and schedules for two distinct PD-1-blocking agents (nivolumab and pembrolizumab). We believe this is an acceptable limitation given that ORR and PFS have not varied significantly within trials testing various schedules and doses of anti-PD-1 antibodies. For example, a randomized trial of pembrolizumab given at 10mg/kg either every 2 or 3 weeks could not detect a difference in response rate (34% vs 33%) or 6-month PFS rate (47% vs 46%).17 In a second-line setting after ipilimumab, patients treated with pembrolizumab at either 10mg/kg or 2mg/kg every 3 weeks had similar ORRs in both Phase 1 and Phase 2 trials.16, 18 The Phase 1 escalation of nivolumab in cutaneous melanoma did not appear to follow linear dose response kinetics.14 Therefore, the exact dose and schedule is unlikely to have significantly impacted the clinical efficacy. In addition, the inclusion of patients who received commercial agents or pembrolizumab via the EAP likely provides a more relevant ‘real-world’ response rate for practitioners who treat patients with these rare tumors outside the context of a clinical trial.

We did not intend to compare nivolumab and pembrolizumab in this study; instead, we pooled patients with these rare melanoma subtypes to explore the clinical efficacy of anti-PD-1 therapy in this population. It is possible that differences in efficacy between nivolumab and pembrolizumab exist within these subtypes of melanoma. This requires further study once more patients are treated with each agent.

Recognizing the limitations of a retrospective analysis that compare unplanned cohorts, the numerically similar response rates in mucosal, acral, and cutaneous melanoma to anti-PD1 therapy raise the question of what biological mechanisms underlie responses in these subtypes. Several groups have reported that the probability of obtaining clinical benefit to checkpoint blockade in different tumor types is linked to the mutational burden of the tumors themselves. In patients with cutaneous melanoma receiving ipilimumab, a higher mutational burden was associated with improved survival.23, 24 In a recent Phase 2 trial of nivolumab in patients with mismatch repair (MMR)-deficient carcinomas and MMR proficient colorectal adenocarcinomas, MMR deficient cancers had a significantly higher mutational burden (over 20-fold) and response rate (40%; 95% CI: 12–74%) than MMR proficient colorectal cancers (0%; 95% CI: 0–20%).21 In a concurrent publication in this issue, the ORR to PD-1/PD-L1 in uveal melanoma, which has a very low mutational burden,32 was 3%, supporting this notion. The somatic mutation rate of both acral and mucosal melanomas has been established as 5–10 fold lower than melanomas arising in chronically sun-damaged skin, however.8, 9 This suggests that the response rate, if it were strictly related to somatic mutational burden, should be lower for mucosal and acral melanomas than their cutaneous counterparts. More complex mechanisms beyond mutational burden may be contributing to immune responses in these rare melanoma subtypes.

One mechanism of response to PD-1 inhibition may be related to the specific tumor microenvironment present within each tumor. In a retrospective analysis of a prospective trial of cutaneous melanoma treated with pembrolizumab, patients with pre-treatment tumors that had higher densities of CD8+ T cells at the invasive margin, particularly those expressing PD-1, or more clonal expansion of the T cell receptor were more likely to obtain objective responses.33 A similar analysis of a prospective trial of the PD-Ligand 1 (PD-L1) inhibitor MPDL3280 across multiple tumor types found an association between objective responses and higher PD-L1 and CTLA4 expression as well as T-helper type 1 gene expression signature.34

At present, there is a dearth of published data regarding the prevalence and subtypes of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) in acral and mucosal melanomas. The histologic presence of TILs can be a useful marker for distinguishing acral melanoma in situ lesions from benign acral nevi,35 suggesting that most acral melanomas overcome some degree of immune surveillance to metastasize. The presence of TILs was associated with superior clinical outcomes in retrospective analyses of primary acral melanomas and oral cavity mucosal melanomas.36, 37 Future research into TILs and other immune subsets will help elucidate mechanisms of resistance to immune surveillance, such as beta-catenin signaling.38 This in turn will help identify patients whose tumors will respond to PD-1 blockade and suggest rational combination strategies.

A large, single-institution analysis of median OS from time of metastasis for 2920 patients with various melanoma subtypes demonstrated an inferior median OS for the 237 patients with mucosal melanoma versus the 105 patients with acral melanomas spanning several decades (9.1 vs 11.4 months, p<0.001).11 The median OS in this cohort for patients with acral melanoma was 31 months, underscoring the magnitude of clinical benefit seen with modern checkpoint inhibitors and targeted therapy for these patients. The OS data for patients with mucosal melanoma were not mature enough for presentation in this manuscript, and further study is warranted to understand whether this subtype continues to display more aggressive clinical behavior in the era of PD-1 blockade.

Overall, this analysis is the first published report on the efficacy of PD-1 blockade in patients with advanced or unresectable acral and mucosal melanomas and supports the routine use of these agents for these rare melanoma subtypes. The role of specific driver mutations, immunologic infiltrates and potential biomarkers of response and resistance needs to be investigated further in these tumors. The efficacy of newer therapies, such as the combination of ipilimumab and nivolumab, should also be investigated.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Research support: Bristol-Myers Squibb (BMS) and Merck provided financial support for the conduct of the trials analyzed retrospectively in this manuscript. ANS, DK, JDW, and MAP receive support through the NIH Cancer Center Support Grant P30 CA008748.

Footnotes

Author Contributions

ANS – Conception/design, data acquisition, data analysis, drafting article, final approval of document, agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work. Responsible for overall content as guarantor.

RRM – Conception/design, data acquisition, data analysis, drafting article, final approval of document, agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

PAO – data acquisition, drafting article, final approval of document, agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

DBJ – data acquisition, drafting article, final approval of document, agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work

KKT – data acquisition, drafting article, final approval of document, agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work

SR – data acquisition, drafting article, final approval of document, agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work

ZE – data acquisition, drafting article, final approval of document, agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work

RJS – data acquisition, drafting article, final approval of document, agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work

JJL – data acquisition, drafting article, final approval of document, agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work

TCG – data acquisition, review/editing article, final approval of document, agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work

AKSS – data acquisition, review/editing article, final approval of document, agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work DK – data analysis and interpretation, drafting article, final approval of document, agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work

VC – data acquisition and curation, drafting article, final approval of document, agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work

CB – data acquisition and curation, drafting article, final approval of document, agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work

IP – data acquisition, drafting article, final approval of document, agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work

MBA – data acquisition, review/editing article, final approval of document, agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work

AA – conception/design, review/editing article, final approval of document, agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work

AR – conception/design, review/editing article, final approval of document, agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work

JDW – conception/design, review/editing article, final approval of document, agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work

MAP – conception/design, review/editing article, final approval of document, agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work

Conflict of Interest: ANS received travel support from BMS and is on a scientific advisory board for Vaccinex. RRM received travel grants from Merck Serrano. ZE reports no relevant disclosures. AKS has served as a consultant for BMS. MAP has received honoraria from Merck and BMS, a research grant from BMS, and has served on scientific advisory boards for Caladrius, BMS, and Amgen. DBJ is on advisory boards for BMS and Genoptix. JW has grant support from BMS and personal fees from BMS and Merck. AR has received personal fees from Merck, Novartis, Genentech, GlaxoSmithKline, Flexus, Compugen, and Amgen. He has ownership/stock in Kita Pharma.

References

- 1.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2015. CA Cancer J Clin. 2015;65:5–29. doi: 10.3322/caac.21254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McLaughlin CC, Wu XC, Jemal A, Martin HJ, Roche LM, Chen VW. Incidence of noncutaneous melanomas in the U.S. Cancer. 2005;103:1000–1007. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dupin E, Le Douarin NM. Development of melanocyte precursors from the vertebrate neural crest. Oncogene. 2003;22:3016–3023. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chang AE, Karnell LH, Menck HR. The National Cancer Data Base report on cutaneous and noncutaneous melanoma: a summary of 84,836 cases from the past decade. The American College of Surgeons Commission on Cancer and the American Cancer Society. Cancer. 1998;83:1664–1678. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19981015)83:8<1664::aid-cncr23>3.0.co;2-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bastian BC. The molecular pathology of melanoma: an integrated taxonomy of melanocytic neoplasia. Annu Rev Pathol. 2014;9:239–271. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pathol-012513-104658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Curtin JA, Busam K, Pinkel D, Bastian BC. Somatic activation of KIT in distinct subtypes of melanoma. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:4340–4346. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.2984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Curtin JA, Fridlyand J, Kageshita T, et al. Distinct sets of genetic alterations in melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:2135–2147. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa050092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Furney SJ, Turajlic S, Stamp G, et al. Genome sequencing of mucosal melanomas reveals that they are driven by distinct mechanisms from cutaneous melanoma. J Pathol. 2013;230:261–269. doi: 10.1002/path.4204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Furney SJ, Turajlic S, Stamp G, et al. The mutational burden of acral melanoma revealed by whole-genome sequencing and comparative analysis. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res. 2014;27:835–838. doi: 10.1111/pcmr.12279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bello DM, Chou JF, Panageas KS, et al. Prognosis of acral melanoma: a series of 281 patients. Ann Surg Oncol. 2013;20:3618–3625. doi: 10.1245/s10434-013-3089-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Postow MA, Kuk D, Bogatch K, Carvajal RD. Assessment of overall survival from time of metastastasis in mucosal, uveal, and cutaneous melanoma. ASCO Meeting Abstracts. 2014;32:9074. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Barth A, Wanek LA, Morton DL. Prognostic factors in 1,521 melanoma patients with distant metastases. J Am Coll Surg. 1995;181:193–201. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hamid O, Robert C, Daud A, et al. Safety and tumor responses with lambrolizumab (anti-PD-1) in melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:134–144. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1305133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Topalian SL, Hodi FS, Brahmer JR, et al. Safety, activity, and immune correlates of anti-PD-1 antibody in cancer. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:2443–2454. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1200690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Topalian SL, Sznol M, McDermott DF, et al. Survival, durable tumor remission, and long-term safety in patients with advanced melanoma receiving nivolumab. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:1020–1030. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.53.0105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Robert C, Ribas A, Wolchok JD, et al. Anti-programmed-death-receptor-1 treatment with pembrolizumab in ipilimumab-refractory advanced melanoma: a randomised dose-comparison cohort of a phase 1 trial. Lancet. 2014;384:1109–1117. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60958-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Robert C, Schachter J, Long GV, et al. Pembrolizumab versus Ipilimumab in Advanced Melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:2521–2532. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1503093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ribas A, Puzanov I, Dummer R, et al. Pembrolizumab versus investigator-choice chemotherapy for ipilimumab-refractory melanoma (KEYNOTE-002): a randomised, controlled, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16:908–918. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(15)00083-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Weber JS, D'Angelo SP, Minor D, et al. Nivolumab versus chemotherapy in patients with advanced melanoma who progressed after anti-CTLA-4 treatment (CheckMate 037): a randomised, controlled, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16:375–384. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(15)70076-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Robert C, Long GV, Brady B, et al. Nivolumab in previously untreated melanoma without BRAF mutation. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:320–330. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1412082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Le DT, Uram JN, Wang H, et al. PD-1 Blockade in Tumors with Mismatch-Repair Deficiency. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:2509–2520. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1500596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rizvi NA, Hellmann MD, Snyder A, et al. Cancer immunology. Mutational landscape determines sensitivity to PD-1 blockade in non-small cell lung cancer. Science. 2015;348:124–128. doi: 10.1126/science.aaa1348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Snyder A, Makarov V, Merghoub T, et al. Genetic basis for clinical response to CTLA-4 blockade in melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:2189–2199. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1406498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Van Allen EM, Miao D, Schilling B, et al. Genomic correlates of response to CTLA-4 blockade in metastatic melanoma. Science. 2015;350:207–211. doi: 10.1126/science.aad0095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Larkin J, Chiarion-Sileni V, Gonzalez R, et al. Combined Nivolumab and Ipilimumab or Monotherapy in Untreated Melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2015 doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1504030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Postow MA, Chesney J, Pavlick AC, et al. Nivolumab and Ipilimumab versus Ipilimumab in Untreated Melanoma. New England Journal of Medicine. 2015;372:2006–2017. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1414428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wolchok JD, Kluger H, Callahan MK, et al. Nivolumab plus ipilimumab in advanced melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:122–133. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1302369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Larkin J, D'Angelo S, Sosman J, et al. Efficacy and safety of Nivolumab (NIVO) monotherapy in the treatment of advanced mucosal melanoma (MEL) Pigment Cell & Melanoma Research. 2015;28:789. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bartell HL, Bedikian AY, Papadopoulos NE, et al. Biochemotherapy in patients with advanced head and neck mucosal melanoma. Head Neck. 2008;30:1592–1598. doi: 10.1002/hed.20910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Harting MS, Kim KB. Biochemotherapy in patients with advanced vulvovaginal mucosal melanoma. Melanoma Res. 2004;14:517–520. doi: 10.1097/00008390-200412000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kim KB, Sanguino AM, Hodges C, et al. Biochemotherapy in patients with metastatic anorectal mucosal melanoma. Cancer. 2004;100:1478–1483. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Furney SJ, Pedersen M, Gentien D, et al. SF3B1 mutations are associated with alternative splicing in uveal melanoma. Cancer Discov. 2013;3:1122–1129. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-13-0330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tumeh PC, Harview CL, Yearley JH, et al. PD-1 blockade induces responses by inhibiting adaptive immune resistance. Nature. 2014;515:568–571. doi: 10.1038/nature13954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Herbst RS, Soria JC, Kowanetz M, et al. Predictive correlates of response to the anti-PD-L1 antibody MPDL3280A in cancer patients. Nature. 2014;515:563–567. doi: 10.1038/nature14011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tan KB, Moncrieff M, Thompson JF, et al. Subungual melanoma: a study of 124 cases highlighting features of early lesions, potential pitfalls in diagnosis, and guidelines for histologic reporting. Am J Surg Pathol. 2007;31:1902–1912. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e318073c600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lee SJ, Lim HJ, Choi YH, et al. The clinical significance of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes and microscopic satellites in acral melanoma in a korean population. Ann Dermatol. 2013;25:61–66. doi: 10.5021/ad.2013.25.1.61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Song H, Wu Y, Ren G, Guo W, Wang L. Prognostic factors of oral mucosal melanoma: histopathological analysis in a retrospective cohort of 82 cases. Histopathology. 2015 doi: 10.1111/his.12692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Spranger S, Bao R, Gajewski TF. Melanoma-intrinsic [bgr]-catenin signalling prevents anti-tumour immunity. Nature. 2015 doi: 10.1038/nature14404. advance online publication. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.