Abstract

Introduction:

Halomonas hamiltonii is a Gram-negative, halophilic, motile, and nonspore-forming rod bacterium. Although most Halomonas sp. are commonly found in saline environments, it has rarely been implicated as a cause of human infection. Herein, the authors present a case report of continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis (CAPD)-related peritonitis attributed to H hamiltonii.

Case presentation:

An 82-year-old male patient who had been receiving CAPD therapy presented to an emergency department with complaints of abdominal pain and cloudy dialysate that had persisted for 2 days. The peritoneal dialysate was compatible with CAPD peritonitis, with white blood cell count of peritoneal effluent of 810/mm3 and neutrophils predominated (60%). Two days after culture on blood agar medium, nonhemolytic pink mucoid colonies showed, with cells showing Gram-negative, nonspore-forming rods with a few longer and larger bacilli than usual were found. We also performed biochemical tests and found negative responses in K/K on the triple sugar iron test and H2S and equivocal (very weak) response in the motility test, but positive responses to catalase, oxidase, and urease tests. The partial sequence of the 16S rRNA gene of a bacterium detected by peritoneal fluid culture was utilized for a Basic Local Alignment Search Tool search, which revealed that the organism was H hamiltonii. Intraperitoneal antibiotics were administered for 21 days, and the patient was discharged without clinical problems.

Conclusion:

We present here the first case report of CAPD-related peritonitis caused by H hamiltonii, which was identified using molecular biological techniques. Although guidelines do not exist for the treatment of infections caused by this organism, conventional treatment for Gram-negative organisms could be effective.

Keywords: first case report, Halomonas hamiltonii, PD peritonitis, peritoneal dialysis, peritonitis

1. Introduction

Continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis (CAPD) is an important treatment option for end-stage renal disease (ESRD). Although the rate of peritonitis has declined in recent years because of improvements in the CAPD technique, peritonitis remains a major complication that causes significant morbidity and mortality in ESRD patients on CAPD.[1,2]

Halophilic bacteria inhabit a wide range of environments and play important roles in the microbial diversities of saline environments.[3–7]Halomonas strains are halophiles usually found in highly saline environments, such as the Dead Sea and the frigid waters of Antarctica.[3–7] The organisms also exhibit great versatility in terms of their abilities to successfully grow in environments with widely varying temperatures and pH values.

Some renal care centers provide hemodialysis patients with written information stating that hemodialyzers can be contaminated in the bicarbonate used to prepare dialysis fluid, and that bacteria may persist despite cleaning and flushing procedures because machines can become contaminated by biofilms and bicarbonate inflow.[9] However, there have been no previous reports of Halomonas infection in ESRD patients on CAPD. Here, we describe the first case report of CAPD-related peritonitis due to H hamiltonii.

2. Case report

An 82-year-old male patient who had been receiving CAPD therapy for ∼1 year was admitted because of abdominal pain and turbid peritoneal effluent that persisted for 3 days. The underlying cause of the ESRD was hypertensive nephropathy, and his dialysis treatment consisted of 4 exchanges of 2 L of dialysate daily. The patient had never been on hemodialysis and had been administered peritoneal dialysis after receiving a diagnosis of ESRD. There was no relevant family history, and the patient had no alcohol consumption or smoking history. The patient was a monk who lived in the countryside and used groundwater for toiletry and drinking.

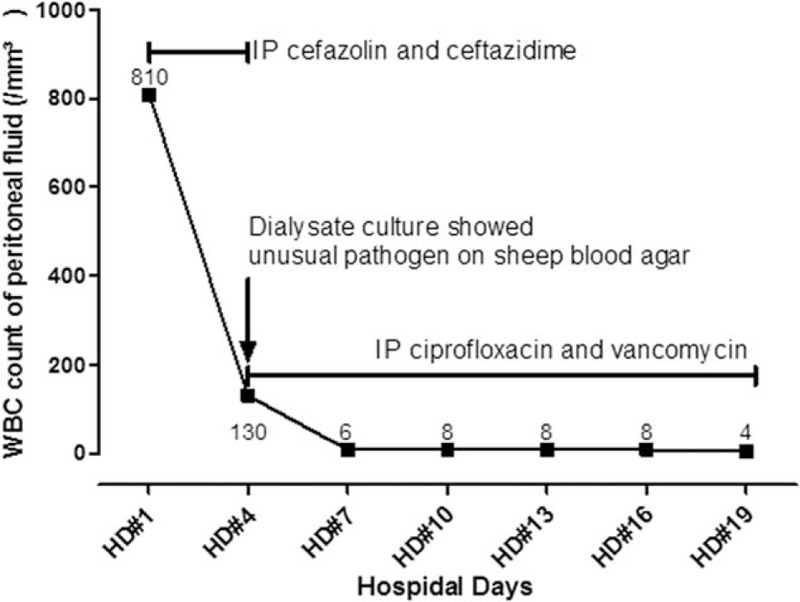

On admission, his blood pressure, heart rate, respiratory rate, and body temperature were 120/80 mm Hg, 72 beats/min, 19/min, and 36.5°C, respectively. Abdominal examination showed diffuse tenderness; however, the CAPD catheter tunnel was normal, and its exit site was clear. Initial laboratory findings were: leukocytes 4250/mm3, hemoglobin 9.5 g/dL, platelets 164,000/mm3, sodium 136 mEq/L, potassium 2.9 mEq/L, chloride 100 mEq/L, blood urea nitrogen 33 mg/dL, creatinine 4.6 mg/dL, aspartate aminotransferase (AST) 25 IU/L, alanine aminotransferase (ALT) 10 IU/L, total bilirubin 0.3 mg/dL, total protein 5.4 g/dL, and albumin 2.7 g/dL. The peritoneal dialysate showed CAPD peritonitis; the white blood cell (WBC) count of the peritoneal effluent was 810/mm3 and neutrophils predominated (60%) (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Time-frame figure of the disease course.

Two peritoneal dialysate samples were inoculated into BacT/ALERT PF Plus culture bottles (bioMérieux, Marcy-I’ Etoile, France) and incubated in a BacT/ALERT 3D Blood Culture System (bioMérieux, Marcy-I’ Etoile, France). Immediately after peritoneal dialysate was sent for bacterial culture, the patient was empirically started on an antibiotics regimen consisting of cefazolin and ceftazidime intraperitoneally.

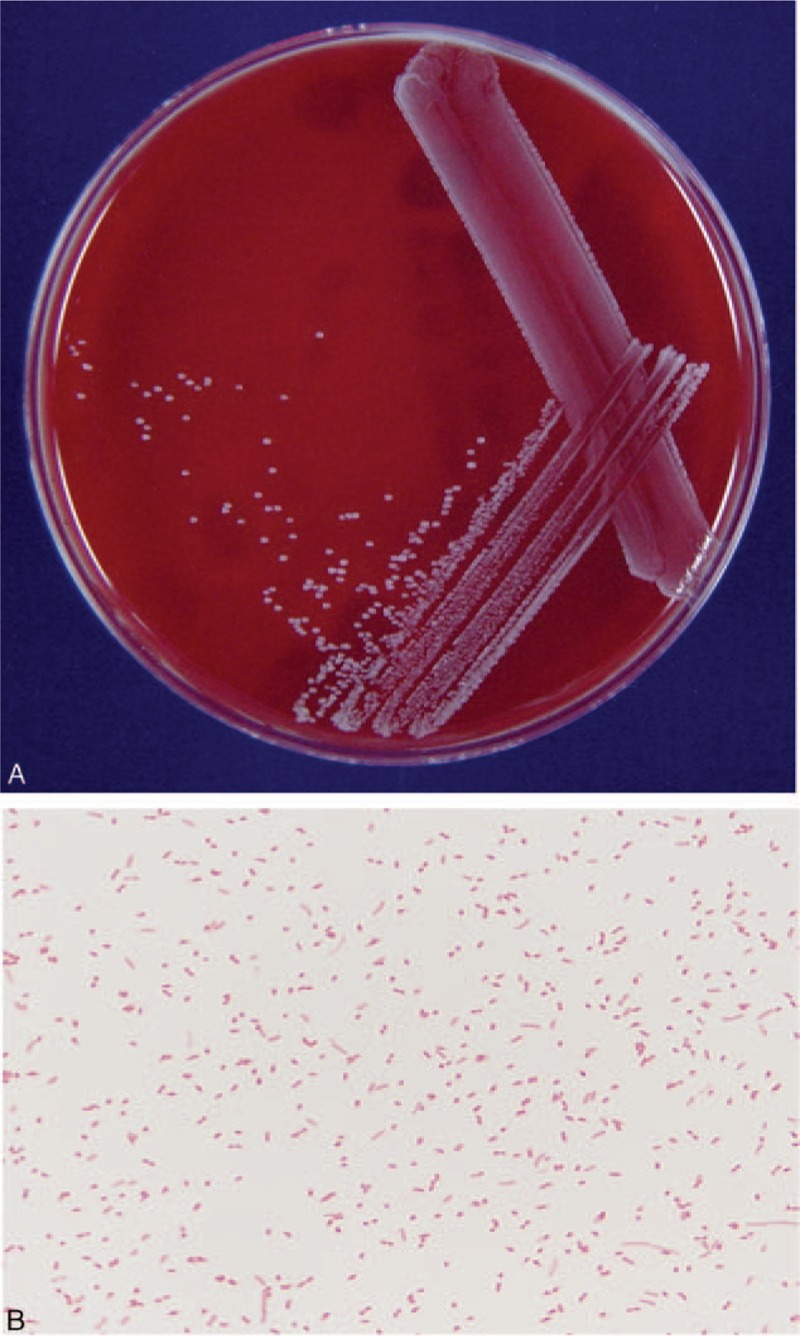

On day 4 after admission and 2 days after culture at 37 °C under 5% CO2, the peritoneal dialysate culture showed 2-mm gray-white, nonhemolytic colonies on sheep blood agar (Fig. 2A), but did not grow on MacConkey's agar. Cells were Gram-negative, nonspore-forming rods with a few longer and larger bacilli than usual (Fig. 2B). The isolate was identified as Methylobacterium sp. based on a positive reaction to urease (GN 0000000200000000) as determined by a commercial identification kit (Vitek II system, bioMérieux, Marcy-I’ Etoile, France).

Figure 2.

(A) H hamiltonii on blood agar medium showing nonhemolytic pink mucoid colonies after incubation for 48 h. (B) Gram stain of H hamiltonii showing Gram-negative, nonspore-forming rods with a few longer and larger bacilli than usual (Gram stain ×1000).

The WBC count of the peritoneal fluid was 130/mm3 with neutrophils predominant (61%) on day 4 after admission. On day 6 after admission, empirical antibiotic treatment was stopped, after which intraperitoneal (IP) ciprofloxacin and vancomycin were started, even though the patient was improving because the authors believed that caution should be taken in considering the possibility of cephalosporin-resistant organisms until the causative organism is identified. On day 18 after admission, the clinical condition of the patient had entirely recovered, and the peritoneal WBC count was 8/mm3. Intraperitoneal treatment was continued for 21 days, and the patient was discharged without any problems (Fig. 1).

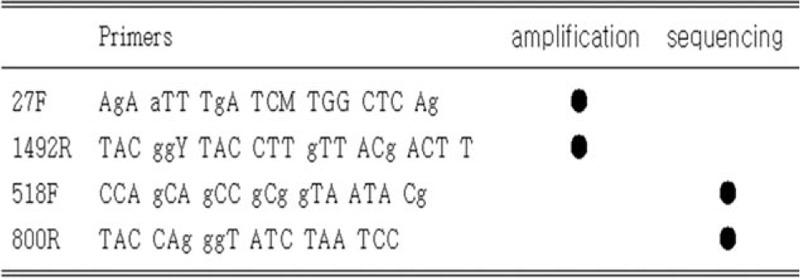

The Vitek 2 (BioMerieux Inc.) automated identification system cannot subdivide Methylobacterium sp; therefore, we requested a molecular biological evaluation from Macrogen (Macrogen Inc., Korea) based on DNA isolated from a cultured colony at day 6 after admission. The 16S rRNA gene was sequenced using universal primers (Fig. 3) and then compared with sequences retrieved from the GenBank, European Molecular Biology Laboratory (EMBL), and DNA Data Bank of Japan (DDBJ) databases. The isolate showed the highest 16S rRNA gene sequence similarity (of 99%) to H hamiltonii W1025T (GenBank accession number AM941396). The partial sequence of the 16S rRNA gene of a bacterium detected by peritoneal fluid culture was utilized for a Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (BLAST) search, which revealed that the organism was H hamiltonii. Accordingly, the causative organism was concluded as H hamiltonii. These results were received after the patient had been discharged.

Figure 3.

Primers used for amplification and sequencing during 16S rRNA analysis.

3. Discussion

To date, the gold standard for identifying pathogens in peritoneal dialysate is culture, but CAPD-related peritonitis is usually treated empirically. So culture-negative peritonitis often exists and remains a clinical issue with renal care centers. To increase susceptibility to bacterial culture, we use blood culture bottles instead of conventional media. In particular, the pediatric blood culture bottles used at our center enable bacterial cultures to be performed on samples as small as 5 mL. And pediatric blood culture bottle can absorb antibiotics, so bacteria that do not grow well in conventional media grow at high rate. Gram-positive bacteria usually grow in blood agar and Gram-negative bacteria in MacConkey agar. In our case, the Gram-negative bacterium grew in blood agar and not definite in MacConkey agar. Because the bacterium did not grow on this medium, we requested a molecular biological evaluation to enable definitive organism identification, and subsequently, we identified the organism as H hamiltonii.

H hamiltonii is an aerobic, halophilic, Gram-negative, nonspore-forming rod bacterium, which contains Q-9 as the predominant ubiquinone and C18:1 ω7 c and C16:0 as the major fatty acids.[9] In this study, cultured colonies are circular, smooth, cream-colored, and translucent. Good growth is observed on sheep blood agar. The family Halomonadaceae was first described in 1988 by Franzmann et al, [8] and although most Halomonas sp. are commonly found in saline or high-salt environments, it has rarely been implicated as a causative organism in human infections. Moreover, a few cases of infections attributed to hemodialysis, hemodialysis machines, and environmental sources in renal care centers have been reported.[9,10,11]

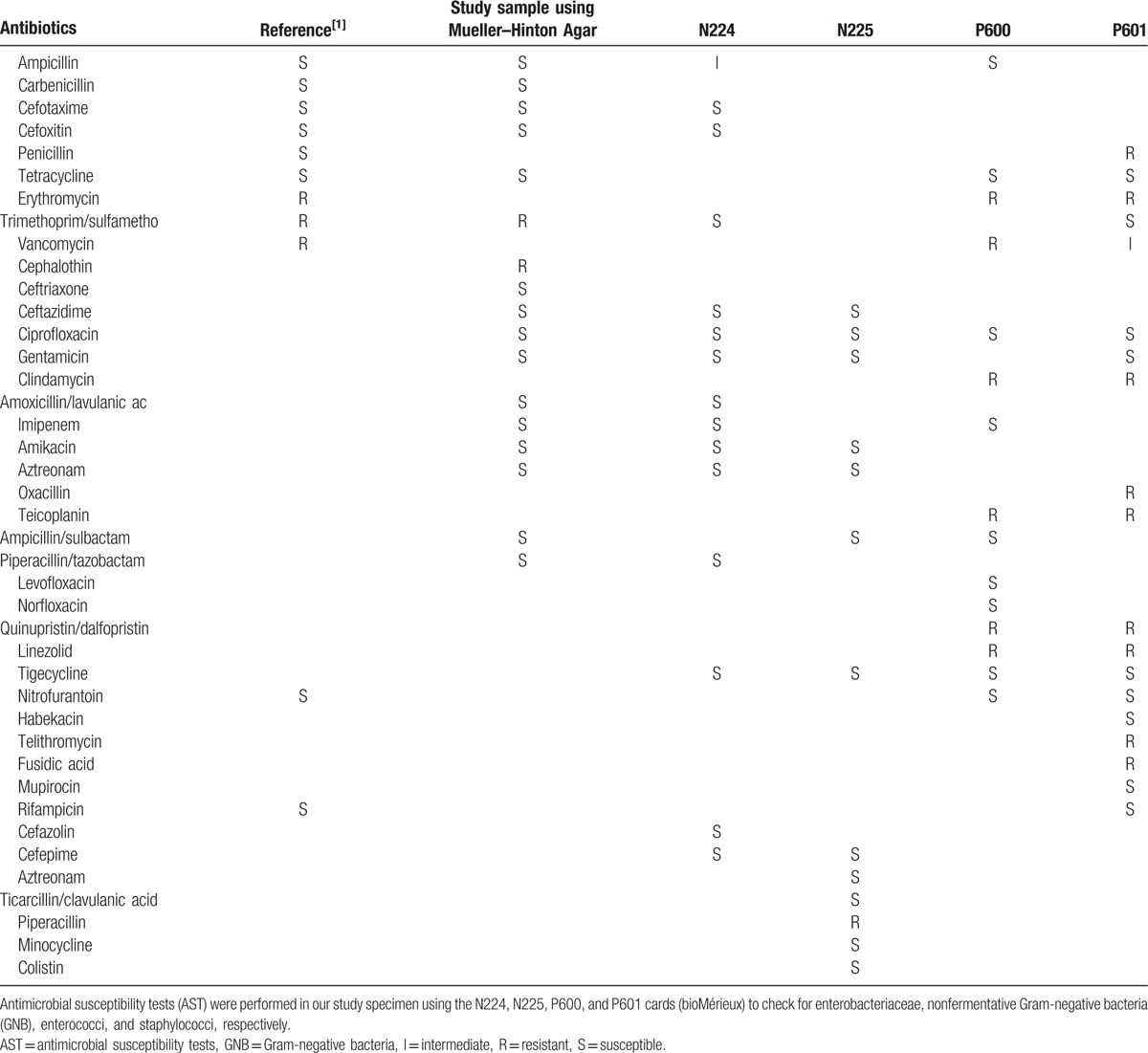

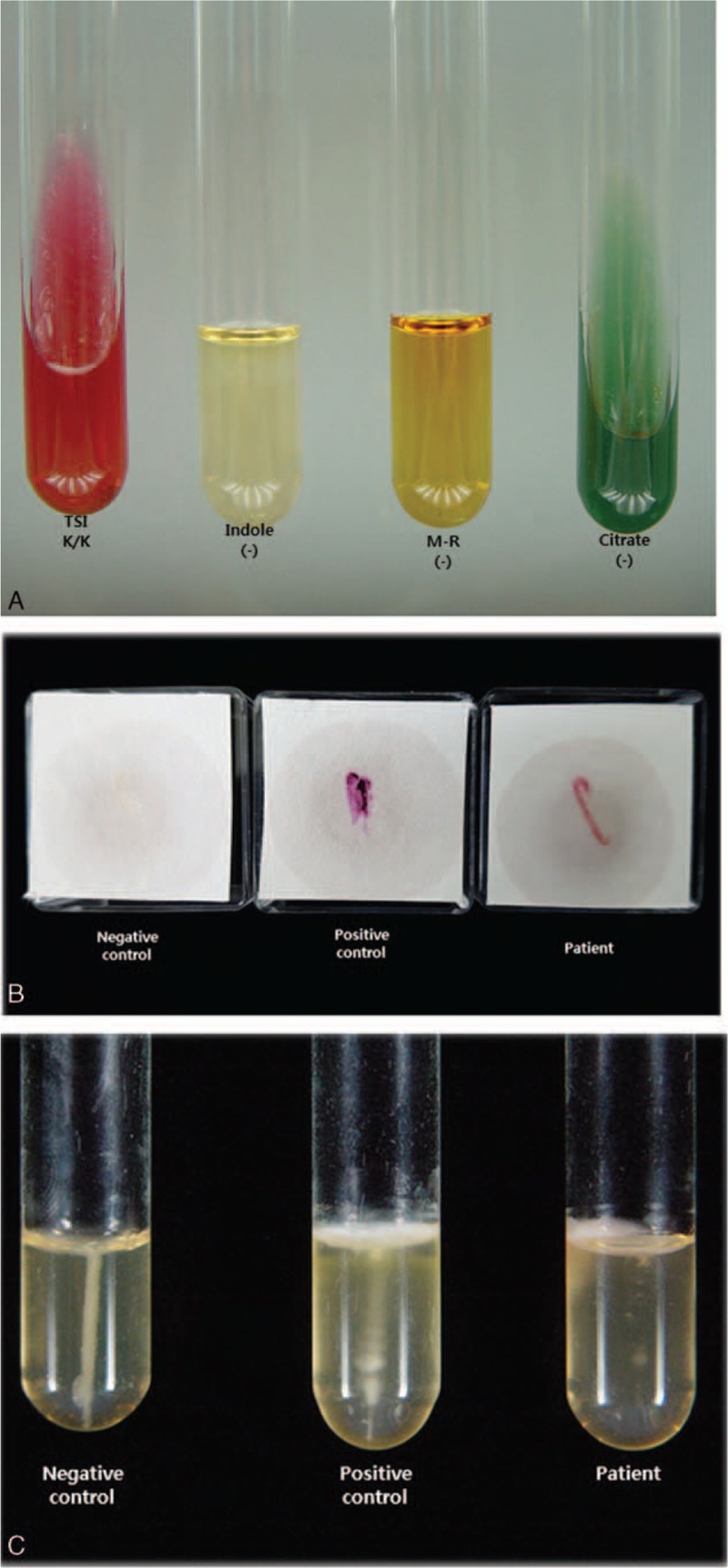

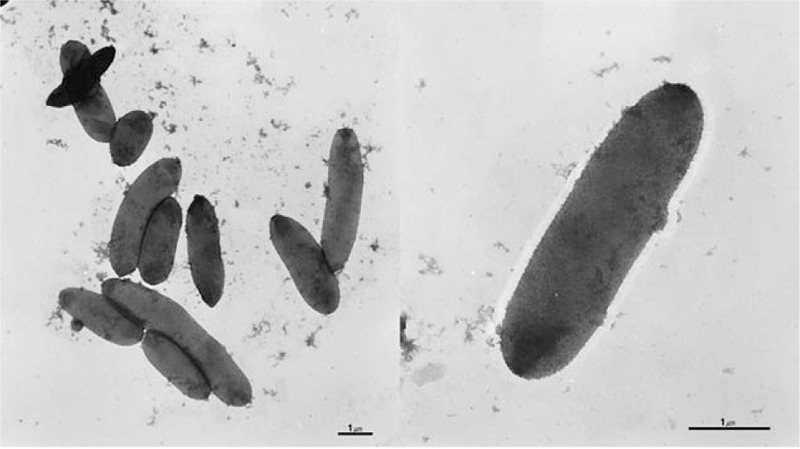

Little is known about the clinical implications of peritoneal dialysis-associated peritonitis (PD peritonitis) caused by Halomonas species. Antibiotic susceptibility to H hamiltonii has been revealed in previous studies. Specifically, Lee et al described the characteristics of Halomonas, especially in ESRD patients with maintenance hemodialysis.[9,10] They had previously reported the treatment of Halomonas-infected hemodialysis patients. However, to the best of our knowledge, there is no Halomonas-specific treatment protocol in PD peritonitis. In hemodialysis patients, conventional antibiotics coverage for Gram-negative rod was successful.[9] Moreover, the results of antimicrobial susceptibility tests (ASTs) have been reported.[9] In the present study, we also conducted ASTs of our study specimen using the N224, N225, P600, and P601 cards (bioMérieux) for enterobacteriaceae, nonfermentative Gram-negative bacteria (GNB), enterococci, and staphylococci, respectively (Table 1). The results of our study were consistent with those of previous studies.[9,10] In this study, we additionally attempted to conduct microscopic examination of Halomonas in peritoneal dialysis fluid. Good growth was observed on blood agar medium, and the biochemical tests for strain characterization revealed negative responses in K/K on the triple sugar iron (TSI) test and H2S, a weak positive equivocal response in the motility test, and positive responses to the catalase, oxidase, and urease tests (Fig. 4). These strains of Halomonas species differ from each in the previous study in terms of having flagella. In our specimen, the motility test is not conclusive. Thus, we performed electron microscopic observation of flagellation in our specimen. We failed to demonstrate that the culture organisms are motile with flagella (Fig. 5). In our specimen, we concluded that this Halomonas species has no flagellae and no motility.

Table 1.

Antimicrobial susceptibility tests (AST) for H hamiltonii.

Figure 4.

Biochemical tests (A), oxidase test (B), and motility test (C) for strain characterization.

Figure 5.

Electron microscopic observation of cultured H hamiltonii.

The patient described in this report was discharged after 21 days of intraperitoneal antibiotic treatment and was later readmitted at our renal care center with CAPD-related peritonitis on October 3rd, 2014. Culture and genetic analyses on this second occasion identified Pseudomonas pseudoalcaligenes as the pathogenic organism. Thus, we concluded that on this second occasion the peritonitis was caused by a different bacterium and that H hamiltonii was causative at first admission.

Patients with maintaining PD have reduced immunity and can therefore be infected with bacteria that do not cause problems for healthy individuals, although infections by Halomonas are rare. Because peritoneal dialysis patients are susceptible to recurrent bacterial infections, accurate identification of the causative organism is essential, and molecular biological methods can be helpful in this context.

It is often not clear why an causal organism cannot be cultured, and the underlying microbiological characterization is poorly understood.[12] To increase susceptibility to bacterial culture, we used the blood culture bottle-based technique with large volume of effluent as recommended by ISPD 2016 peritonitis guideline in this study. However, in our case, the Gram-negative bacterium seemed to grow in blood agar and appeared not to in MacConkey's agar. As a result, molecular biological techniques can be useful for this group of patients. Several studies have shown that the use of molecular biological techniques such as quantitative PCR for bacterial DNA, rRNA amplification by PCR, and so on, can detect and identify bacterial pathogens, thereby increasing diagnosis of CAPD-related peritonitis.[13,14] Moreover, molecular biological analysis could help diagnose culture-negative peritonitis.[15] The patient in the present case was a monk who lived deep in the mountains. Therefore, we collected water from the wells and groundwater that the monk used, and had done culture study. However, we failed to disclose the causative organism, contrary to our expectation. Our institute was founded by the Jogye Order of Korean Buddhism in the rural area. This case might be interesting report of CAPD-related peritonitis due to H hamiltonii whose profession is Buddhist priest, practicing asceticism.

In summary, we provide here the first case report of CAPD-related peritonitis caused by H hamiltonii, which was identified using molecular biological techniques. Although guidelines do not exist for the treatment of infections caused by this organism, conventional treatment for Gram-negative organisms could be effective.

Acknowledgments

This study is a retrospective, noninterventional study, and written informed consent was waived. Approval from institutional review board was not necessary, because of case report with fewer 3 patients not requiring additional resource of patient designed to contribute to generalizable medical knowledge under Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA).

Footnotes

Abbreviations: ALT = alanine aminotransferase, AST = aminotransferase, BLAST = The Basic Local Alignment Search Tool, CAPD = continuous ambulatory peritoneal dialysis, DDBJ = DNA Data Bank of Japan, EMBL = European Molecular Biology Laboratory, ESRD = end-stage renal disease, GNB = Gram-negative bacteria, HD = hemodialysis, I = Intermediate, IP = intra-peritoneal, ISPD = International Society for Peritoneal Dialysis, PD = peritonial dialysis, R = resistant, S = susceptible, TSI test = triple sugar iron test, WBC = white blood cell.

KDY and JYL contributed equally to this study.

The authors have no funding and conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- [1].Troidle L, Gorban-Brennan N, Kliger A, et al. Continuous peritoneal dialysis-associated peritonitis: a review and current concepts. Semin Dial 2003;16:428–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Piraino B, Bailie GR, Bernardini J, et al. Peritoneal dialysis-related infections recommendations: 2005 update. Perit Dial Int 2005;25:107–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Oren A. Halophilic Microorganisms and Their Eenvironments. London: Kluwer Academic Publishers; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- [4].Mabinya LV, Cosa S, Mkwetshana N, et al. Halomonas s. OKOH-OKOH10 marine bacterium isolated from the bottom sediment of Algoa Bay-produces a polysaccharide bioflocculant: partial characterization and biochemical analysis of its properties. Molecules 2011;16:4358–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Dou G, He W, Liu H, et al. Halomonas heilongjiangensis sp. nov., a novel moderately halophilic bacterium isolated from saline and alkaline soil. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek 2015;108:403–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Kim KK, Lee KC, Jeong H, et al. Draft genome sequence of the human pathogen Halomonas stevensii S18214T. J Bacteriol 2012;194:5143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Kim KK, Jin L, Yang HC, et al. Halomonas gomseomensis sp. nov., Halomonas janggokensis sp. nov., Halomonas salaria sp. nov. and Halomonas denitrificans sp. nov., moderately halophilic bacteria isolated from saline water. Int J Systemic Evol Microbiol 2007;57:675–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Peter D Franzmann, Uta Wehmeyer, Erko Stackebrandt, et al. Halomonadaceae fam. nov., a new family of the class Proteobacteria to accommodate the genera Halomonas and Deleya. Syst Appl Microbiol 1988;11:16–9. [Google Scholar]

- [9].Stevens DA, Hamilton JR, Johnson N, et al. Halomonas, a newly recognized human pathogen causing infections and contamination in a dialysis center: three new species. Medicine (Baltimore) 2009;88:244–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Kim KK, Lee KC, Oh HM, et al. Halomonas stevensii sp. nov., Halomonas hamiltonii sp. nov. and Halomonas johnsoniae sp. nov., isolated from a renal care centre. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 2010;60:369–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].von Graevenitz A, Bowman J, Del Notaro C, et al. Human infection with Halomonas venusta following fish bite. J Clin Microbiol 2000;38:3123–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Ghali JR, Bannister KM, Brown FG, et al. Microbiology and outcomes of peritonitis in Australian peritoneal dialysis patients. Perit Dial Int 2011;31:651–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Johnson G, Wilks M, Warwick S, et al. Comparative study of diagnosis of PD peritonitis by quantitative polymerase chain reaction for bacterial DNA vs culture methods. J Nephrol 2006;19:45–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Yoo TH, Chang KH, Ryu DR, et al. Usefulness of 23S rRNA amplification by PCR in the detection of bacteria in CAPD peritonitis. Am J Nephrol 2006;26:115–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Ciesielczuk HL, Shorten RJ, Davenport A, et al. The role of 16s rDNA PCR in the diagnosis of peritoneal dialysis-associated peritonitis. J Med Microb Diagn 2012;1:116. [Google Scholar]