Abstract

Background:

Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH) is a rare condition that can be caused by a primary or acquired disorder of uncontrolled immune response. Liver injury is a common complication of HLH; however, HLH presenting as acute liver failure (ALF) has rarely been reported in adults.

Case summary:

A 34-year-old man was admitted to our hospital with nausea and fatigue persisting for 2 weeks and jaundice for 1 week. He had hyperthermia at the onset of disease. At admission, he had severe liver injury with unknown etiology. The laboratory data showed that he had hyperferritinemia, thrombocytopenia, anemia, hypertriglyceridemia, and hypofibrinogenemia. Finally, a bone marrow biopsy revealed hemophagocytic cells, and he was diagnosed with HLH. The patient was treated with prednisone and plasma exchange. However, the liver function of the patient deteriorated, and he finally died of multiorgan failure.

Conclusions:

Reports of adult patients with ALF caused by HLH have increased, and HLH should be suspected in patients with ALF of indeterminate cause. Although the efficacy of the treatment strategy recommended by the HLH 2004 remains to be confirmed in adult patients with ALF caused by HLH, early diagnosis and prompt combined treatment with steroids and cyclosporin A or etoposide should be emphasized.

Keywords: acute liver failure, adults, case report, hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis

1. Introduction

Acute liver failure (ALF) is heterogeneous in etiology and in prognosis.[1] Viral hepatitis and drug-induced hepatitis are the most common causes of ALF; however, the etiology of ALF cannot be determined in about one-third of all cases.[2–4] Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH) occurs as a primary or acquired disorder of uncontrolled immune response.[5] Liver injury has been found in most cases of HLH,[6] but HLH as the cause of ALF has rarely been reported in adults. The clinical characteristic, diagnosis, and treatment of patients with ALF caused by HLH remain largely unknown. Therefore, we present a patient with ALF caused by HLH and give a brief review of the diagnosis and treatment of prior patients with ALF caused by HLH.

2. Case report

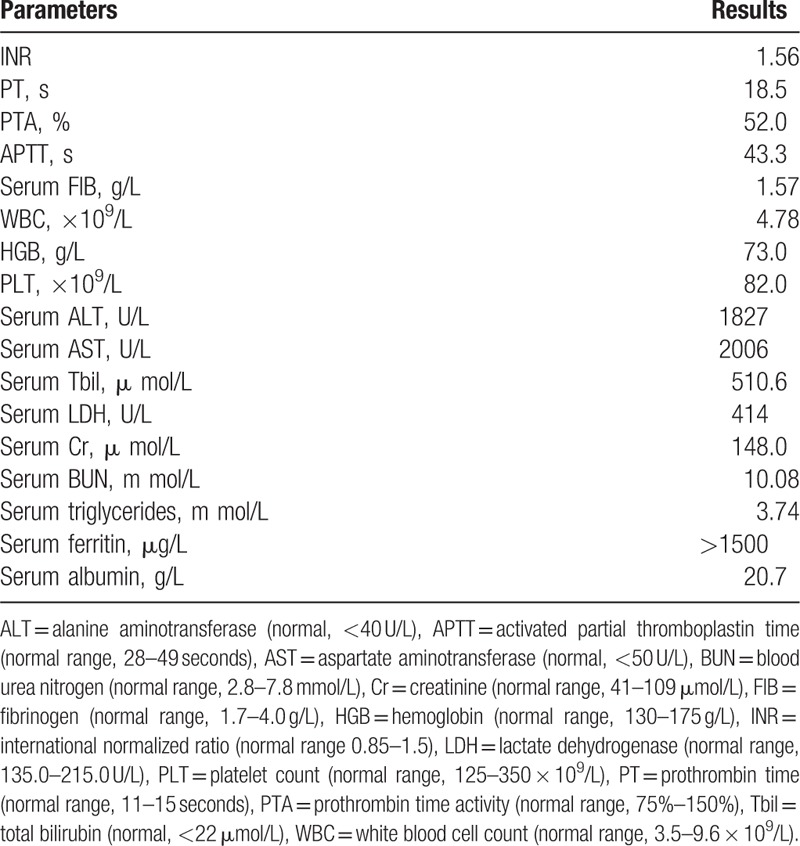

A 34-year-old Chinese man presented to our hospital with nausea and fatigue persisting for 2 weeks and jaundice for 1 week on Mach 31, 2014. At the onset of disease, he had hyperthermia (a peak temperature of up to 40°C) for 1 week. The patient was treated for influenza at a local clinic for 3 days and for acute hepatitis for 1 week. Upon admission, abdominal ultrasound studies showed heterogeneous liver echogenicity and splenomegaly. On examination, he weighed 50 kg and was oriented to person and place; he had marked jaundice over the entire body. Neither spider telangiectasis nor palmar erythema was noted. The superficial lymph nodes were not palpable. The remainder of the examination was unremarkable. The laboratory findings of the patient at the time of admission are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Laboratory findings of the patients with acute liver failure caused by hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis at the time of admission.

Additional studies (indirect immunofluorescence) showed that the patient was negative for IgM antibodies for legionella pneumophila, mycoplasma pneumoniae, chlamydia pneumoniae, influenza virus A and B, Q fever rickettsia, adenovirus, and respiratory syncytial virus. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays for IgM antibodies for Epstein–Barr virus (EBV), hepatitis A and E viruses, cytomegalovirus, herpes simplex viruses 1 and 2, togavirus, and human immunodeficiency virus also were negative. Tests for hepatitis B virus surface antigen and core antibody, and hepatitis C virus antibody were negative. His serum EBV DNA was also negative (real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction). Tests (indirect immunofluorescence) for antinuclear antibody, double-stranded DNA antibody, antiliver-kidney microsomal antibody, antismooth muscle antibody, and anti-mitochondrial antibody M2 also were negative. The patient's serum ceruloplasmin level was normal, and he was not known to be an alcoholic. The patient also had no history of liver disease.

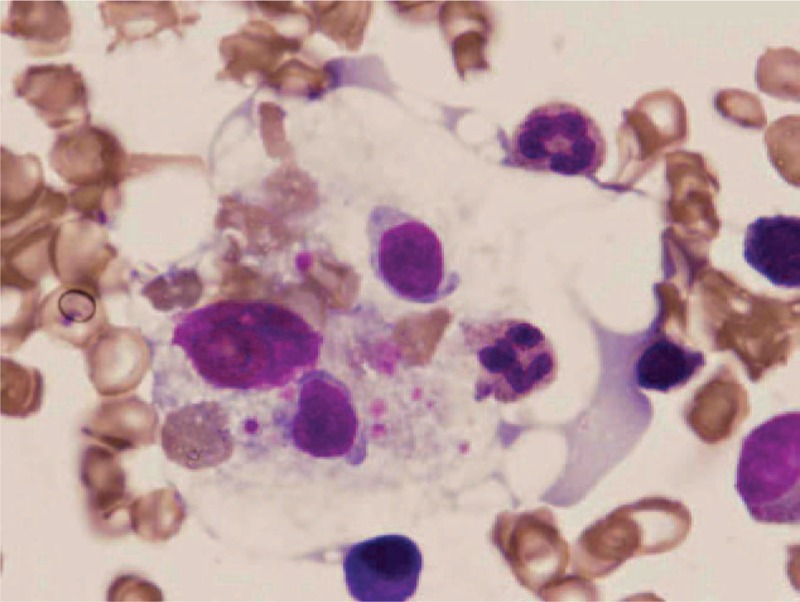

The patient was diagnosed with acute hepatitis with unknown etiology. On the third day after admission, a bone marrow puncture-biopsy was performed, which revealed an elevated percentage of histocytes of 4% (normal range 0.04–0.52%) with frequent hemophagocytosis (Fig. 1). Based on this finding together with the clinical and analytical data (fever, splenomegaly, bicytopenia, a ferritin of >1500 μg/L, and triglycerides of 3.74 m mol/L), the patients was diagnosed as having HLH with ALF.

Figure 1.

Bone marrow smear revealing hemophagocytic histocytes by light microscopy on day 3 after admission (Wright–Giemsa staining, ×1000).

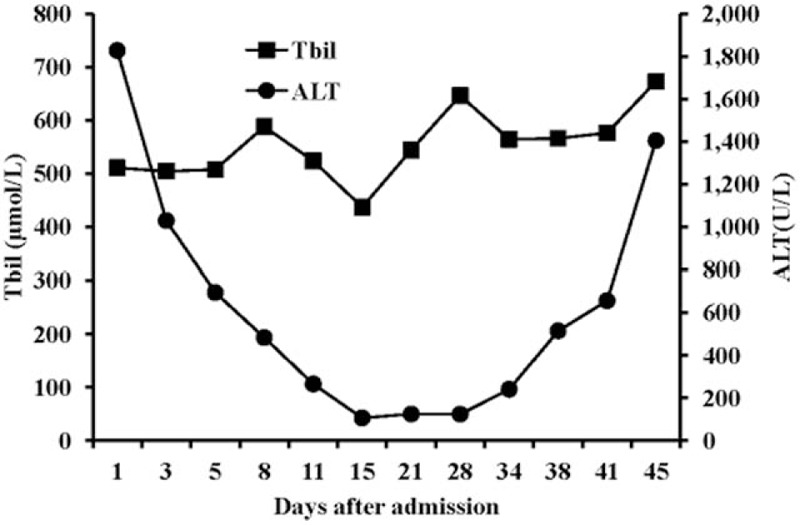

To establish a treatment strategy, we consulted with the specialists in hematology, oncology, and hepatology in our hospital. Because the use of etoposide was contraindicated by liver failure in this patient, the patient was treated with 40 mg prednisone (0.8 mg/kg/day, orally) together with plasma exchange for the first 2 weeks. Plasma exchange was performed 2 times per week, and 2000 to 2500 mL frozen plasma was used each time. Additional treatments including bed rest, liver-protective treatment (glutathione, adenosylmethionine, and branched-chain amino acids), energy supplements and vitamins, intravenous infusion of plasma and albumin, maintenance of water–electrolyte and acid–base equilibriums, and preventing and treating complications were applied to improve his liver and renal function. His serum alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and aspartate transaminase (AST) levels decreased to within normal ranges. His total bilirubin (Tbil) level also decreased to 436 μmol/L (normal <22 μmol/L), and his prothrombin time activity (PTA) increased to 75% (normal range 75–150%). His serum creatinine (Cr) also decreased to 118 μmol/L (normal range 41–109 μmol/L).

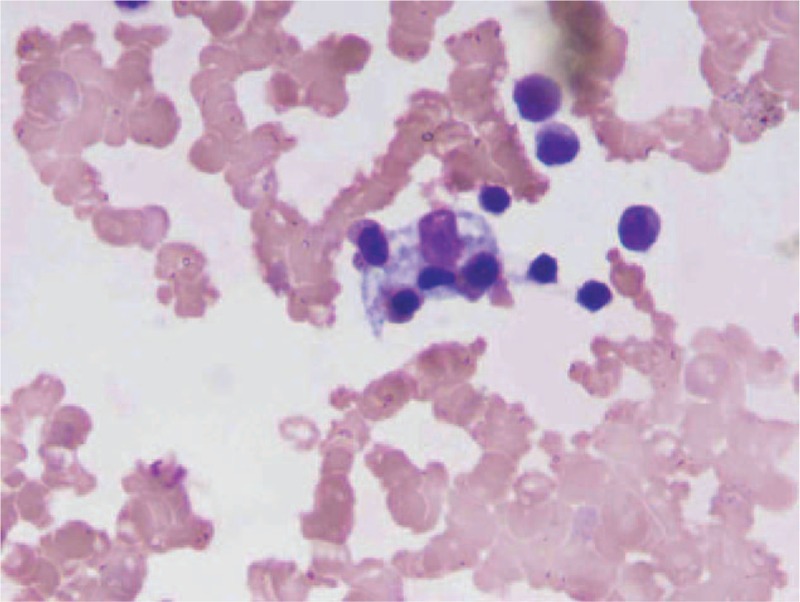

The patient continued to be treated with prednisone (0.8 mg/kg/day, orally) and liver-protective treatment (including infusion of plasma and albumin) from the third to the fourth week of hospitalization, and his PTA and Tbil level were relatively stable during this period. However, his serum albumin level fluctuated between 17.1 and 25.3 g/L (normal range 35–50 g/L), and his ferritin level remained above 1500 μg/L. The patient had fever during the third week, with a temperature reaching 39.6°C. Blood cultures were negative; chest computed tomography (CT) showed bilateral pleural effusion and multiple lung high density lesions. No evidence of tuberculosis or invasive fungal infection was found. Bacterial pneumonia was suspected, and moxifloxacin hydrochloride was administered intravenously at 400 mg/day for 1 week. The fever lasted 3 days and resolved. Five days later, repeated chest CT showed that the pleural effusion had disappeared and the high density lesions in the lung were significantly reduced. A bone marrow puncture-biopsy was repeated and demonstrated that the percentage of activated histiocytes had not decreased from the first examination and hemophagocytosis was also easily found (Fig. 2). After consulting with the hematology, oncology, and hepatology specialists, we prepared to add etoposide to his treatment. However, the patient developed progressive jaundice with significant elevation in ALT and AST levels again during the fifth week in our hospital (Fig. 3). His PTA dropped to 26%, and grade 3 hepatic encephalopathy developed. His blood ammonia level rose to 105.8 μmol/L (normal range 18–72 μmol/L), and serum Cr rose to 245 μmol/L. He was treated with plasma exchange 3 times again. However, his condition rapidly worsened, and he developed hypotension, requiring vasopressor agents. Despite intensive physiological care, including increasing the prednisone dose to 50 mg/day, orally and repeated intravenous infusion of plasma and albumin during the last week, the patient's condition deteriorated, and he died of multiorgan failure during the 6th week of hospitalization. Autopsy was declined.

Figure 2.

Repeated bone marrow smear on the third week after admission. Activated histiocytes and hemophagocytosis were also easily found by light microscopy (Wright–Giemsa staining, ×1000).

Figure 3.

Alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and total bilirubin (Tbil) levels over time after admission. ALT = alanine aminotransferase, Tbil = total bilirubin.

A written informed consent for the case report was obtained from the wife of patient. The consent procedure was approved by the Ethics Committee of Affiliated Hospital of Zunyi Medical College.

3. Discussion

HLH is classified as either primary or familial HLH and secondary or acquired HLH. Primary HLH often results from defects in the perforin, munc 13–4, and syntaxin 11 genes and rarely occurs in adults. Secondary HLH arises from infectious, rheumatologic, malignant, or metabolic disorders.[6,7] EBV is one of the common causes of HLH,[8,9] and the hepatitis virus also has been reported to induce HLH.[10] However, in ∼20% of adult patients with HLH, the underlying causative disease cannot be identified.[11,12] Recent studies have found that ∼14% of adult patients with acquired HLH also have mutations in HLH-related genes.[13] Because we could not examine the HLH-related gene mutations in the present case, whether our patient had any HLH-related genetic abnormalities remains unknown.

HLH has a wide spectrum of clinical manifestations. Liver injury is a common complication of HLH. In previous studies, ∼85% of adult patients with secondary HLH had elevated ALT and AST levels, and ∼50% of patients had hyperbilirubinemia.[11,12] Most patients with HLH only have mild to moderate elevated ALT and AST levels; liver failure as a presentation of HLH is rare and often results from multiorgan failure during the progression of HLH.[14,15] The common histopathological findings of the liver in patients with HLH are nonspecific changes, including sinusoidal dilatation, hepatocellular necrosis, endothelialitis, and steatosis.[16–18] In patients with ALF induced by HLH, massive hepatic necrosis can be found.[19–21] The mechanisms of liver injury caused by HLH remain unknown. It is generally considered that liver injury results from either infiltration of activated hemophagocytic histiocytes or overproduction of cytokines in patients with HLH.[5,22,23] Liver injury may also be the result of underlying diseases.[16,17] In a previous study, in >50% of patients with HLH, the underlying disease process contributed to marked hepatic injury.[17]

Previously, HLH has been considered a rare disease in adults; however, in the last decade, reports of both HLH in adult patients and of cases of ALF caused by HLH have notably increased.[6,24] In a recent report, the diagnosis of HLH dramatically increased after awareness of this disease was increased at a single center in China.[15] A transplant center reported 3 patients with liver failure induced by HLH in 1 year.[20] Therefore, increase awareness is one of the possible reasons for increased reports of ALF caused by HLH. However, whether the incidence of HLH in adult patients has been increased is currently unknown.

The diagnostic criteria for HLH in pediatric patients were established by the Histiocyte Society in 2004,[25] which include fever >38.5°C; splenomegaly; cytopenias involving at least 2 of 3 lineages in the peripheral blood; hyperferritinemia >500 μg/L; increased triglycerides and/or decreased fibrinogen; hemophagocytosis in the bone marrow, spleen, or lymph nodes; low or absent NK-cell activity; and high levels of soluble CD25 (interleukin-2 receptor α). Five of these 8 criteria are required for diagnosis. The diagnosis can also be established by finding the HLH-related gene abnormality. These criteria have been validated in pediatric patients, but their specificity and sensitivity in adult HLH patients remain to be demonstrated.

The diagnosis of ALF induced by HLH is difficult, especially in the early stage of disease. Because patients with HLH lack specific clinical manifestations and laboratory findings, it is difficult to distinguish ALF induced by HLH from ALF caused by a virus, drug, or autoimmune condition.[6] One retrospective study found that 49% of patients with HLH were initially misdiagnosed.[26] Therefore, in patients with ALF of indeterminate cause, HLH should be suspected with a high degree. It has been reported that children with ALF caused by HLH exhibit a higher incidence of pleural effusion, C-reactive protein elevation (especially >5 mg/dL), thrombocytopenia, anemia, fever, splenomegaly, and hypoalbuminemia (<25 g/dL),[27] and whether adult patients with ALF induced by HLH also have these clinical characteristics remains to be demonstrated. Bone marrow puncture-biopsy and/or liver biopsy are helpful in the diagnosis of most cases of HLH; however, in some patients, hemophagocytosis cannot be found in early stage of the disease. Therefore, repeated bone marrow puncture-biopsy and/or liver biopsy is necessary in highly suspected cases.[28,29] Liver biopsy is also helpful in finding the underlying diseases.

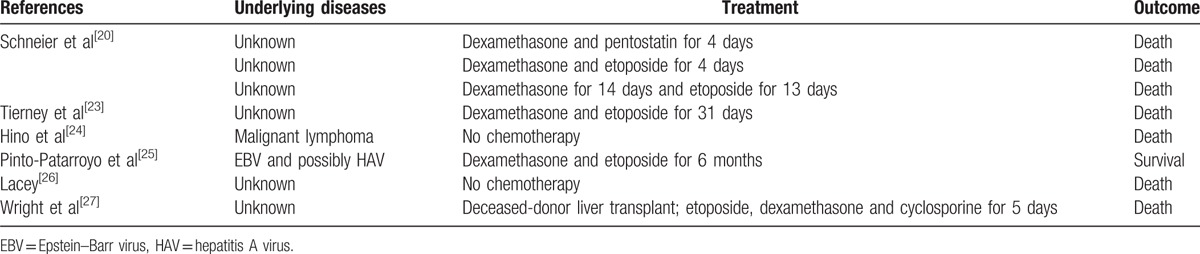

The prognosis of adult patients with HLH is very poor,[19,20,30–33] with mortality ranging from to 41% to 75%,[6,11] depending on underlying diseases,[26] age,[34] ferritin level,[35] and so on. Whether the severity of liver injury determines the outcome of patients with HLH remains unknown. Some studies did not find that ALT or Tbil could serve as prognostic factors,[15,26] whereas others found that cholestasis and a high AST level were associated with poor outcomes of adult HLH patients.[16,36] In EBV-associated HLH, higher ALT and AST levels reflect the severity of HLH.[8] We reviewed all 8 published case reports of patients with ALF caused by HLH (Table 2), and of these, 7 died, indicating that ALF induced by HLH is associated with high mortality.

Table 2.

Reported cases of patients with acute liver failure caused by hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis.

The HLH-2004 protocols recommend a combination of dexamethasone, etoposide, and cyclosporine, followed by bone marrow transplantation for the treatment of primary HLH.[25] This protocol is indicated in all patients younger than 18 years of age who have severe and persistent or reactivated HLH. Although case reports and retrospective studies have shown that the treatment strategy containing etoposide improved the survival of patients with acquired HLH,[36,37] the efficacy of the HLH-2004 protocol in adult patients with HLH still remains to be proved.[24,28] The hepatotoxicity of etoposide makes the treatment of patients with ALF induced by HLH more difficult. Among the 8 patients with ALF caused by HLH reported, 6 were treated with etoposide and dexamethasone for different periods, and only 1 patient survived (Table 2). Delayed diagnosis of HLH was considered the most important factor related to treatment failure. However, the only surviving patient was treated with etoposide and dexamethasone at almost 1 year after the initial symptoms started.[32] Because cases of ALF induced HLH have been rarely reported, we still cannot conclude from the poor outcomes of these case reports that the treatment strategy of the HLH-2004 protocol is ineffective in adult patients with ALF caused by HLH. Early diagnosis and timely treatment with the HLH-2004 protocol has been shown to improve survival in adult patients with HLH;[36–38] therefore, in adult patients with ALF caused by HLH, early diagnosis and treatment must also be emphasized. Liver transplantation has been reported in a patient with ALF caused HLH, and the patient died 20 days after liver transplantation.[33] Liver transplantation was not recommended for children with HLH before; however, a recent study showed it is beneficial in selected children with secondary HLH and ALF.[39] The treatment failure in our case also indicated that the role of plasma exchange is limited in the treatment of patients with ALF caused by HLH. Further studies are needed to identify an effective treatment strategy for patients with ALF induced by HLH.

4. Conclusions

Adult cases of ALF caused by HLH are increasingly recognized, and therefore, in patients with ALF of indeterminate cause, HLH should be suspected with a high degree. Bone marrow puncture-biopsy and/or liver biopsy are helpful in the diagnosis of most cases of HLH. The prognosis of adult patients with ALF caused by HLH is very poor. Although the efficacy of the HLH 2004 protocol in such cases still remains to be demonstrated, early diagnosis and prompt combined treatment with steroids and cyclosporin A or etoposide must be emphasized.

Footnotes

Abbreviations: ALF = acute liver failure, ALT = alanine aminotransferase, APTT = activated partial thromboplastin time, AST = aspartate aminotransferase, BUN = blood urea nitrogen, Cr = creatinine, CT = computed tomography, EBV = Epstein–Barr virus, ELISA = enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, FIB = fibrinogen, HAV = hepatitis A virus, HBsAg = hepatitis B virus surface antigen, HGB = hemoglobin, HLH = hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis, INR = international normalized ratio, kg = kilogram, LDH = lactate dehydrogenase, NK cells = natural killer cells, PLT = platelet, PT = prothrombin time, PTA = prothrombin time activity, Tbil = total bilirubin, WBC = white blood cell.

Funding: This work was supported by the Funds of the Chinese National Natural Science Foundation Project (814600124/H0316, 81160067/H0318).

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- [1].Lee WM, Stravitz RT, Larson AM. Introduction to the revised American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases Position Paper on acute liver failure 2011. Hepatology (Baltimore, MD) 2012;55:965–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Ostapowicz G, Fontana RJ, Schiodt FV, et al. Results of a prospective study of acute liver failure at 17 tertiary care centers in the United States. Ann Intern Med 2002;137:947–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Hadem J, Tacke F, Bruns T, et al. Etiologies and outcomes of acute liver failure in Germany. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2012;10:664–9. e662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Zhao P, Wang C, Liu W, et al. Causes and outcomes of acute liver failure in China. PloS One 2013;8:e80991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Rosado FG, Kim AS. Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis: an update on diagnosis and pathogenesis. Am J Clin Pathol 2013;139:713–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Ramos-Casals M, Brito-Zerón P, López-Guillermo A, et al. Adult haemophagocytic syndrome. Lancet 2014;383:1503–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Mehta RS, Smith RE. Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH): a review of literature. Med Oncol 2013;30:740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Chen J, Wang X, He P, et al. Viral etiology, clinical and laboratory features of adult hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. J Med Virol 2016;88:541–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Tseng YT, Sheng WH, Lin BH, et al. Causes, clinical symptoms, and outcomes of infectious diseases associated with hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis in Taiwanese adults. J Microbiol Immunol Infect 2011;44:191–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Seo JY, Seo DD, Jeon TJ, et al. A case of hemophagocytic syndrome complicated by acute viral hepatitis A infection. Korean J Hepatol 2010;16:79–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Li J, Wang Q, Zheng W, et al. Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis: clinical analysis of 103 adult patients. Medicine (Baltimore) 2014;93:100–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Otrock ZK, Eby CS. Clinical characteristics, prognostic factors, and outcomes of adult patients with hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Am J Hematol 2015;90:220–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Zhang K, Jordan MB, Marsh RA, et al. Hypomorphic mutations in PRF1, MUNC13-4, and STXBP2 are associated with adult-onset familial HLH. Blood 2011;118:5794–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Mayordomo-Colunga J, Rey C, Gonzalez S, et al. Multiorgan failure due to hemophagocytic syndrome: A case report. Cases J 2008;1:209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Li F, Yang Y, Jin F, et al. Clinical characteristics and prognostic factors of adult hemophagocytic syndrome patients: a retrospective study of increasing awareness of a disease from a single-center in China. Orphanet J Rare Dis 2015;10:20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].de Kerguenec C, Hillaire S, Molinie V, et al. Hepatic manifestations of hemophagocytic syndrome: a study of 30 cases. Am J Gastroenterol 2001;96:852–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Tsui WM, Wong KF, Tse CC. Liver changes in reactive haemophagocytic syndrome. Liver 1992;12:363–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Favara BE. Histopathology of the liver in histiocytosis syndromes. Pediatr Pathol Lab Med 1996;16:413–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Lacey B. An unexpected cause of acute liver failure. Gastroenterol Rep 2014;2:239–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Schneier A, Stueck AE, Petersen B, et al. An unusual cause of acute liver failure: three cases of hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis presenting at a transplant center. Semin Liver Dis 2016;36:99–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Bravo-Jaimes KM. Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis presenting as acute liver failure in a patient with Hodgkin lymphoma: case report and review of the literature. Rev Gastroenterol Peru 2015;35:256–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Chen JH, Fleming MD, Pinkus GS, et al. Pathology of the liver in familial hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Am J Surg Pathol 2010;34:852–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Larroche C. Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis in adults: Diagnosis and treatment. Joint Bone Spine 2012;79:356–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Hayden A, Park S, Giustini D, et al. Hemophagocytic syndromes (HPSs) including hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH) in adults: a systematic scoping review. Blood Rev 2016;30:411–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Henter JI, Horne A, Arico M, et al. HLH-2004: Diagnostic and therapeutic guidelines for hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2007;48:124–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Parikh SA, Kapoor P, Letendre L, et al. Prognostic factors and outcomes of adults with hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Mayo Clinic Proc 2014;89:484–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Ryu JM, Kim KM, Oh SH, et al. Differential clinical characteristics of acute liver failure caused by hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis in children. Pediatr Int 2013;55:748–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Lehmberg K, Ehl S. Diagnostic evaluation of patients with suspected haemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Br J Haematol 2013;160:275–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Meghan Campo M, Nancy Berliner M. Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis in adults. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am 2015;29:915–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Tierney LM, Jr, Thabet A, Nishino H. Case records of the Massachusetts General Hospital. Case 10-2011. A woman with fever, confusion, liver failure, anemia, and thrombocytopenia. N Engl J Med 2011;364:1259–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Hino T, Sata M, Arima N, et al. A case of malignant lymphoma with hemophagocytic syndrome presenting as hepatic failure. Kurume Med J 1997;44:53–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Pinto-Patarroyo GP, Rytting ME, Vierling JM, et al. Haemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis presenting as liver failure following Epstein-Barr and prior hepatitis A infections. BMJ Case Rep 2013;2013:bcr2013008979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Wright G, Wilmore S, Makanyanga J, et al. Liver transplant for adult hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis: case report and literature review. Exp Clin Transplant 2012;10:508–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Oto M, Yoshitsugu K, Uneda S, et al. Prognostic factors and outcomes of adult-onset hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis: a retrospective analysis of 34 cases. Hematol Rep 2015;7:5841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Lin TF, Ferlic-Stark LL, Allen CE, et al. Rate of decline of ferritin in patients with hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis as a prognostic variable for mortality. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2011;56:154–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Arca M, Fardet L, Galicier L, et al. Prognostic factors of early death in a cohort of 162 adult haemophagocytic syndrome: impact of triggering disease and early treatment with etoposide. Br J Haematol 2015;168:63–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Beffermann CN, Pilcante SJ, Ocqueteau TM, et al. Acquired hemophagocytic syndrome treated with HLH 94-04 chemotherapy protocol: report of four cases. Rev Med Chil 2015;143:1172–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Aulagnon F, Lapidus N, Canet E, et al. Acute kidney injury in adults with hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Am J Kidney Dis 2015;65:851–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Amir AZ, Ling SC, Naqvi A, et al. Liver transplantation for children with acute liver failure associated with secondary hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Liver Transplant 2016;22:1245–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]