Abstract

OBJECTIVES

To estimate tuberculosis (TB) rates among young children in the United States by children’s and parents’ birth origins and describe the epidemiology of TB among young children who are foreign-born or have at least 1 foreign-born parent.

METHODS

Study subjects were children <5 years old diagnosed with TB in 20 US jurisdictions during 2005–2006. TB rates were calculated from jurisdictions’ TB case counts and American Community Survey population estimates. An observational study collected demographics, immigration and travel histories, and clinical and source case details from parental interviews and health department and TB surveillance records.

RESULTS

Compared with TB rates among US-born children with US-born parents, rates were 32 times higher in foreign-born children and 6 times higher in US-born children with foreign-born parents. Most TB cases (53%) were among the 29% of children who were US born with foreign-born parents. In the observational study, US-born children with foreign-born parents were more likely than foreign-born children to be infants (30% vs 7%), Hispanic (73% vs 37%), diagnosed through contact tracing (40% vs 7%), and have an identified source case (61% vs 19%); two-thirds of children were exposed in the United States.

CONCLUSIONS

Young children who are US born of foreign-born parents have relatively high rates of TB and account for most cases in this age group. Prompt diagnosis and treatment of adult source cases, effective contact investigations prioritizing young contacts, and targeted testing and treatment of latent TB infection are necessary to reduce TB morbidity in this population.

Keywords: tuberculosis, epidemiology, young children, foreign birth

Tuberculosis (TB) in children <5 years old (young children) is a sentinel event because it represents recent or ongoing disease transmission rather than reactivation of remotely acquired infection; as such, it points to deficiencies in TB control.1 In the United States, an average 416 TB cases were reported annually in young children from 2007 to 2011.2 Recent exposure to an adult with TB disease (the source case) is the primary mode of transmission to young children.3,4 In the United States, although >60% of all TB cases occur among foreign-born persons, 90% of cases in young children occur among US-born persons.5–7 Approximately two-thirds of US-born young children with TB have foreign-born parents, suggesting that this is an important population for prevention efforts.8,9 However, to date, no studies have calculated TB rates in young children by country of birth and parents’ origins.

We used a multistate, cross-sectional observational study to calculate TB rates in young children in 3 subgroups: (1) foreign-born children, (2) US-born children with at least 1 foreign-born parent, and (3) US-born children of US-born parents. To improve understanding of TB in children who are foreign born or have foreign-born parents, we describe the children’s epidemiologic and clinical characteristics and characteristics of source cases.

METHODS

This cross-sectional population-based study of TB in children is part of a general investigation of TB among foreign-born persons in the United States,10 conducted in 2005–2007 by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)-funded Tuberculosis Epidemiologic Studies Consortium (TBESC).11 Each of the consortium’s 20 US sites was located in or partnered with a state or municipal health department (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Reported TB Cases in Children <5 Years Old by Study Site, Nativity, and Enrollment Period, 2005–2006a

| Enrollment Site | Jurisdictions | All Children | Foreign Born | US Born | Years Enrolling |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arkansas Department of Health | State of Arkansas | 3 | 1 | 2 | 1.4 |

| University of Alabama, Birmingham | State of Alabama | 12 | 2 | 10 | 1.4 |

| California Department of Health Services and University of California, San Francisco | Alameda, Orange, San Diego, Santa Clara, and San Francisco counties | 30 | 3 | 27 | 1.9 |

| Denver Public Health and Hospitals Authority | Six counties in the Denver metropolitan area | 4 | 2 | 2 | 1.5 |

| Broward County Department of Health | Broward County, Florida | 4 | 0 | 4 | 1.5 |

| Emory University | Twenty counties in the Atlanta metropolitan area | 23 | 4 | 19 | 1.4 |

| Hawaii Department of Health | State of Hawaii | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1.9 |

| American Lung Association of Metropolitan Chicago | Four counties in the Chicago metropolitan area | 17 | 14 | 3 | 2.0 |

| Maryland Department of Health and Mental Hygiene | State of Maryland | 13 | 3 | 10 | 1.6 |

| Massachusetts Department of Public Health | State of Massachusetts | 12 | 1 | 11 | 1.6 |

| Minnesota Department of Health | State of Minnesota | 12 | 4 | 8 | 1.4 |

| University of Medicine and Dentistry of New Jersey | State of New Jersey | 17 | 1 | 16 | 1.3 |

| New York City Department of Health/Charles P. Felton National TB Center at Harlem | New York City (NYC) | 37 | 6 | 31 | 1.3 |

| New York State Department of Health, Health Research Inc | State of New York excluding New York City | 15 | 2 | 13 | 1.7 |

| RTI International | State of North Carolina | 21 | 3 | 18 | 1.3 |

| Tennessee Department of Health | State of Tennessee | 24 | 4 | 20 | 1.7 |

| Texas Department of State Health Services and University of North Texas Health Science Center | State of Texas | 115 | 10 | 105 | 2.1 |

| Seattle-King County Department of Public Health | King County, WA | 4 | 1 | 3 | 1.4 |

| Total | 364 | 61 | 303 |

Case numbers reflect total case counts for children <5 years old in the given jurisdiction during that study site’s specific 2005 and 2006 enrollment period, not the entire 2 calendar years.

All sites obtained institutional review board approval; for the observational study, the child’s parent or guardian provided written informed consent. The US Department of Health and Human Services provided a Certificate of Confidentiality to each site to protect participants’ sensitive information from involuntary disclosure. Additional information on measures used to protect confidentiality and encourage participation has been published.10

Study Population

Study sites collected TB case counts for all young children during the study’s recruitment period (Table 1) and queried health department staff or the child’s parents to determine parental nativity. Children were eligible for the observational study if they were (1) <5 years old at TB treatment initiation, (2) foreign born or US born with at least 1 foreign-born parent, and (3) living in a TBESC jurisdiction. Sites began and ended the study at different times, based on timing of institutional review board approvals and recruitment rates. Recruitment began at all sites in 2005 and continued a median of 18 months (range = 13–25 months; Table 1). Additional recruitment details have been published.10 CDC’s National Tuberculosis Surveillance System was queried to determine what proportion of TB cases in young children were reported from the study jurisdictions in 2005 and 2006.

Data Collection

Data for the observational study were derived from (1) a structured in-person interview with a child’s parent or guardian for demographic and visa information, (2) routine TB surveillance reports for clinical variables, and (3) local health department resources for information on source cases. The source case is a person with TB who transmitted the infection to a child. When a young child is diagnosed with TB, the local health department attempts to identify the source case to break the chain of transmission. All source cases identified by participating health departments were offered enrollment and interviewed with a standard questionnaire.

The parent’s or guardian’s English proficiency was assessed with a US Census question that has been shown to correlate strongly with scores on standardized English proficiency tests: “I would like to know how well you speak English. Would you say you speak English very well, well, not well, or not at all?”10,12 Persons who responded that they spoke English “very well” were interviewed in English unless they requested an interpreter; all others were interviewed in their native language by using bilingual interviewers and interpreters.

All questionnaires and consent documents were translated from English into 10 languages that, together with English, accommodated almost 90% of participants; for the remainder, professional translation occurred at the time of interview.10

Calculation of TB Rates

To account for differences in recruitment periods, each of the site’s total number of TB cases in children <5 years old was annualized to estimate the average number of cases in a 12-month period. Population information on children <5 years old by children’s and parents’ origin (US-born children of US-born parents, US-born children with at least 1 foreign-born parent, and foreign-born children) for all counties in the study’s catchment area was obtained by special request to the US Census Bureau’s American Community Survey for 2005–2007 (see Supplemental Table 6).

TB incidence was determined by dividing the annualized number of TB cases in each subgroup by the average annual population census estimates obtained over a 3-year period (2005–2007) for all study sites; 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated by Poisson distribution methods.13,14 To assess the impact of excluding children with unknown parental birth country, the annualized number of such children was added to each US-born category, and TB incidence and 95% CI recalculated.

Analysis of Data From Observational Study

US-born and foreign-born children were compared by clinical and sociodemographic variables by using Pearson’s χ2 or Fisher’s exact tests. Analyses were conducted with Stata 10.0 (Stata Corp, College Station, TX), SAS 9.3 (SAS Institute, Inc, Cary, NC), and Microsoft Excel 2007 (Microsoft, Inc, Redmond, WA).

RESULTS

A total of 364 TB cases in children <5 years old were identified in the 20 US study sites (Table 1); this represented 49.6% of all TB cases in young children reported to the National Tuberculosis Surveillance System in 2005 and 2006. More than 80% (n = 303) of the children were US born, including 194 (64%) with at least 1 foreign-born parent, 76 (25%) with US-born parents, and 33 (11%) whose parents’ birth countries were unknown. Sixty-one children (17%) were foreign born.

TB Rate Estimates

Estimated TB rates per 100 000 population for children <5 years old were 2.57 for all children, 24.03 for foreign-born children, 4.81 for US-born children with at least 1 foreign-born parent, and 0.75 for US-born children of US-born parents. More than half of the cases (53%) occurred among US-born children with foreign-born parents (Table 2). When the 33 children with unknown parental birthplaces were included in the group with foreign-born parents, that group’s TB rate increased to 5.61; including them in the group with US-born parents increased that rate to 1.08.

TABLE 2.

TB Cases and Rates Among Children Who Are <5 Years Old by Birth Origin and Parents’ Birth Origin in 20 Jurisdictions in the United States

| Total | Foreign Born | US Born With at Least 1 Foreign-Born Parent | US Born of US-Born parents | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of TB cases in children <5 y olda (%) | 364 (100) | 61 (16.7) | 194 (53.3) | 76 (20.9) |

| Annualized case number | 217.12 | 36.75 | 117.18 | 43.86 |

| Population <5 y of age estimated from US Census ACS 2005–2007 (%) | 8 450 150 (100) | 152 890 (1.8) | 2 433 890 (28.8) | 5 863 360 (69.4) |

| TB rateb (95% CI) | 2.57 (2.23–2.91) | 24.03 (16.21–31.85) | 4.81 (3.94–5.68) | 0.75 (0.53–0.97) |

ACS, American Community Survey.

The total number of 364 includes 33 (9%) children, not shown in the other columns, with unknown parental birth countries.

TB rates per 100 000 population, annualized and adjusted for study enrollment period. To estimate the impact of excluding the 33 children with unknown parental birth country on incidence, the entire annualized number (19.33) was added to each US-born category, and TB incidence and 95% CIs were calculated to be 5.61 (4.67–6.55) for US-born children with at least 1 foreign-born parent; 1.08 (0.81–1.35) for US born with US-born parents.

Observational Study Results: Demographics

A total of 255 children (61 foreign born, 194 US born) were eligible for the observational study, of whom 149 (58%) were enrolled: 27 (44%) foreign born and 122 (63%) US born; US born children were more likely to be enrolled (P = .01). Reasons for nonenrollment included parental refusal, >6 months elapsed since treatment start, inability to contact the child’s parents, or the child moved; case counts by nonenrollment reason were not provided by study sites. Two-thirds of enrolled children were Hispanic; the median age was 2 years. The foreign-born children were from Mexico (9), Central America/South America/Caribbean (5), sub-Saharan Africa (5), South Asia/East Asia/Pacific (5), and Eastern Europe/Central Asia (3); 6 (22%) were adopted by US-born parents. Adoptees were from Guatemala, China, Ethiopia, and Kazakhstan, and 2 were from the Russian Federation. US-born children were more likely than foreign-born children to be Hispanic and to be diagnosed before their first birthday (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics, Care-Seeking Behavior, and Access to Health Care Among 149 Children <5 Years Old Newly Diagnosed With TB in the United States in 2005–2006 and Enrolled in Observational Study, by the Child’s Nativity

| Participant Characteristics | All Cases (N = 149) |

US Born (N = 122) |

Foreign Born (N = 27) |

Risk Ratioa | 95% CI | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % (n/N) | n | % (n/N) | n | % (n/N) | |||

| Age | ||||||||

| Younger than 1 y | 38 | 26 | 36 | 30 | 2 | 7 | 4.28 | 1.06–17.22 |

| Between 1 and 4 y | 111 | 74 | 86 | 70 | 25 | 93 | referent | |

| Gender | ||||||||

| Male | 68 | 46 | 54 | 44 | 14 | 52 | 0.78 | 0.39–1.54 |

| Female | 81 | 54 | 68 | 56 | 13 | 48 | referent | |

| Hispanic | ||||||||

| Yes | 99 | 66 | 89 | 73 | 10 | 37 | 3.37 | 1.67–6.80 |

| No | 50 | 34 | 33 | 27 | 17 | 63 | referent | |

| Country or world region of parent’s birthb | ||||||||

| Mexico | 81 | 54 | 72 | 59 | 9 | 33 | 2.38 | 1.15–4.96 |

| Latin America/South America/Caribbean | 29 | 19 | 25 | 20 | 4 | 15 | 1.39 | 0.52–3.71 |

| South Asia/East Asia/Pacific | 19 | 13 | 15 | 12 | 4 | 15 | 0.84 | 0.33–2.17 |

| Sub-Saharan Africa | 14 | 9 | 10 | 8 | 4 | 15 | 0.60 | 0.24–1.48 |

| United Statesc | 6 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 22 | excluded | |

| Parent’s visa status at US entryd | ||||||||

| Undocumented | 72 | 48 | 63 | 52 | 9 | 33 | 1.82 | 0.84–3.96 |

| Documented | 57 | 38 | 44 | 36 | 13 | 48 | referent | |

| Unknown | 20 | 13 | 15 | 12 | 5 | 19 | excluded | |

| Informant speaks English “not at all” | ||||||||

| Yes | 46 | 31 | 37 | 30 | 9 | 33 | 0.89 | 0.43–1.84 |

| No | 103 | 69 | 85 | 70 | 18 | 67 | referent | |

| Parent feared child’s deportatione | ||||||||

| Yes | 15 | 10 | 11 | 9 | 4 | 15 | 0.81 | 0.32–2.01 |

| No | 107 | 72 | 84 | 69 | 23 | 85 | referent | |

| Not applicable | 21 | 14 | 21 | 17 | 0 | 0 | excluded | |

| No opinion | 6 | 4 | 6 | 5 | 0 | 0 | excluded | |

| Health insurance | ||||||||

| Yes | 113 | 76 | 100 | 82 | 13 | 48 | 3.38 | 1.76–6.51 |

| No | 36 | 24 | 22 | 18 | 14 | 52 | referent | |

| Reason for initially seeking health caref | ||||||||

| Screenings and well-baby examinations | 37 | 25 | 17 | 14 | 20 | 74 | 0.12 | 0.05–0.25 |

| Symptoms | 61 | 41 | 56 | 46 | 5 | 19 | 3.05 | 1.22–7.61 |

| Contact investigation or known TB exposure | 51 | 34 | 49 | 40 | 2 | 7 | 6.51 | 1.60–26.38 |

| Source case identified | ||||||||

| Yes | 79 | 53 | 74 | 61 | 5 | 19 | 4.97 | 1.99–12.41 |

| No | 70 | 47 | 48 | 39 | 22 | 81 | referent | |

| Probable location of TB transmission | ||||||||

| Inside United States | 102 | 68 | 97 | 80 | 5 | 19 | 9.55 | 3.85–23.66 |

| Outside United States | 36 | 24 | 15 | 12 | 21 | 78 | 0.09 | 0.04–0.21 |

| Exposure risks both inside and outside United States | 11 | 7 | 10 | 8 | 1 | 4 | 2.07 | 0.31–13.86 |

| TB site | ||||||||

| Pulmonary only | 102 | 68 | 83 | 68 | 19 | 70 | 0.91 | 0.43–1.94 |

| Pulmonary and extrapulmonary | 21 | 14 | 17 | 14 | 4 | 15 | 0.94 | 0.36–2.45 |

| Extrapulmonary only | 26 | 17 | 22 | 18 | 4 | 15 | 1.22 | 0.46–3.22 |

| Abnormal chest radiograph | ||||||||

| Yes | 130 | 87 | 104 | 85 | 26 | 96 | 0.29 | 0.04–2.03 |

| No | 17 | 11 | 16 | 13 | 1 | 4 | referent | |

| Unknown/not done | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | excluded | |

| Specimen positive by culture | ||||||||

| Yes | 45 | 30 | 44 | 36 | 1 | 4 | 11.25 | 1.57–80.38 |

| Culture negative | 38 | 26 | 25 | 20 | 13 | 48 | 0.37 | 0.19–0.71 |

| Not done or unknown | 66 | 44 | 53 | 43 | 13 | 48 | 0.81 | 0.41–1.60 |

| Tuberculin skin test positive at diagnosis | ||||||||

| Yes | 124 | 83 | 99 | 81 | 25 | 93 | 0.62 | 0.16–2.37 |

| No | 16 | 11 | 14 | 11 | 2 | 7 | referent | |

| Unknown/not done | 9 | 6 | 9 | 7 | 0 | 0 | excluded | |

| TB symptoms | ||||||||

| Yes | 99 | 66 | 83 | 68 | 16 | 59 | 1.36 | 0.68–2.71 |

| No | 50 | 34 | 39 | 32 | 11 | 41 | referent | |

Risk ratio estimates the relative risk of US-born children compared with foreign-born children (with asymptotic 95% CIs).

At least 1 parent born in given region. When discordant and US-born for 1 parent, foreign region given (n = 22); Mexico given when Mexican and Latin American parents (n = 4).

All children were adopted (adoptee birth countries were Guatemala, China, Ethiopia, Kazakhstan, and 2 from the Russian Federation).

At least 1 parent with given visa status. When discordant, undocumented given over documented.

Interview informant was asked: “When you took your child for tuberculosis treatment, were you afraid you or your child might be sent back to the country you came from?”

Reasons for initially seeking health care among adopted children were post adoption check-ups (n = 4), well-baby examinations, and symptoms (n = 1).

Of the 143 children with at least 1 foreign-born parent, more than half the parents (57%) were from Mexico. Almost half (48%) of the foreign-born parents reported they were undocumented at time of US entry, and 31% spoke no English. Fifteen (10%) of the 149 parents said “yes” when asked if they feared they or their children would be deported when they took the children for TB treatment.

Care-Seeking Behavior

US-born children were more likely to have identified source cases, have medical insurance, and be diagnosed through medical evaluation for symptoms; foreign-born children were more likely to be diagnosed through medical screenings (Table 3). Of the 70 children without identified source cases, 37 (53%) were diagnosed during medical visits for symptoms and 33 (47%) during screenings, most commonly well-child examinations (n = 18). Of the 79 children with identified source cases, 51 (65%) were diagnosed through the source case’s contact investigation (n = 47) or evaluation for a known TB exposure (n = 4), 24 (30%) were diagnosed during medical visits for symptoms, and 4 (5%) from well-child examinations.

Clinical Findings

Forty-seven children (32%) had some extrapulmonary TB; extrapulmonary involvement was more common in symptomatic children (40% vs 14%; P < .01). Meningeal and miliary presentations were more common in infants (24% vs 5%; P < .01; data not shown). Of the 140 children who received tuberculin skin tests, 89% were positive.

All but 1 of 45 culture-confirmed TB cases occurred in US-born children (Table 3). Of the 44 with isoniazid, rifampin, and ethambutol drug susceptibility testing (DST), 1 (2.3%) had multidrug-resistant (MDR) TB (resistance to both isoniazid and rifampin) and 5 (11.4%) had isoniazid-resistant, rifampin-susceptible TB. Three children who were only clinically confirmed had source cases with MDR TB. Of the 35 isolates with pyrazinamide (PZA) DST, 5 (14.3%) were resistant. All children with PZA-resistant TB were US born with a Mexican-born parent (33% PZA resistance among the 15 children of Mexican-born parents with PZA DST results) and had extrapulmonary involvement. Those who had eaten unpasteurized dairy products were more likely to have PZA resistance: 60% vs 7% (P = .02). Ninety-nine children (66%) had TB symptoms; most commonly fever (56%) and cough (54%) (Table 4). A median 52 days elapsed between symptom onset and TB treatment initiation: 44.5 for US-born and 115 for foreign-born children (Table 4). A median 2 clinical visits occurred before treatment initiation; 15 of 99 symptomatic participants had >4 visits (maximum 7).

TABLE 4.

Characteristics of 99 Symptomatic Children <5 Years Old Newly Diagnosed With TB in 20 Jurisdictions in the United States in 2005–2006 and Enrolled in Observational Study, by the Child’s Nativity

| Symptomatic Participant Characteristics | All Cases (N = 99) |

US Born (N = 83) |

Foreign Born (N = 16) |

Risk Ratioa | 95% CI | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % (n/N) | n | % (n/N) | n | % (n/N) | |||

| Cough | ||||||||

| Yes | 53 | 54 | 45 | 54 | 8 | 50 | 1.15 | 0.47–2.83 |

| No | 46 | 46 | 38 | 46 | 8 | 50 | referent | |

| Fever | ||||||||

| Yes | 55 | 56 | 51 | 61 | 4 | 25 | 3.75 | 1.30–10.82 |

| No | 44 | 44 | 32 | 39 | 12 | 75 | referent | |

| Night sweats | ||||||||

| Yes | 43 | 43 | 34 | 41 | 9 | 56 | 0.60 | 0.24–1.48 |

| No | 56 | 57 | 49 | 59 | 7 | 44 | referent | |

| Weight loss | ||||||||

| Yes | 38 | 38 | 33 | 40 | 5 | 31 | 1.37 | 0.52–3.64 |

| No | 61 | 62 | 50 | 60 | 11 | 69 | referent | |

| Lymphadenopathy | ||||||||

| Yes | 20 | 20 | 16 | 19 | 4 | 25 | 0.78 | 0.28–2.16 |

| No | 77 | 78 | 65 | 78 | 12 | 75 | referent | |

| Unknown | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | excluded | |

| Reason for initially seeking health careb | ||||||||

| Screenings and well-baby examinations | 18 | 18 | 8 | 10 | 10 | 63 | 0.13 | 0.06–0.32 |

| Symptoms | 57 | 58 | 52 | 63 | 5 | 31 | 2.99 | 1.12–7.95 |

| Contact investigation or known TB exposure | 24 | 24 | 23 | 28 | 1 | 6 | 4.80 | 0.67–34.47 |

| Median days from symptom onset to treatment initiation (IQR) | 52 | (23–117) | 44.5 | (21–112) | 115 | (36–160) | 0.999 | 0.998–1.000 |

| Median number of physician visits from symptom onset to treatment initiationc (IQR) | 2 | (1–3) | 2 | (1–2.5) | 2 | (1–3) | 1.023 | 0.951–1.100 |

Risk ratio estimates the relative risk of US-born children compared with foreign-born children (with asymptotic 95% CIs).

Reasons for initially seeking health care among symptomatic adopted children were post-adoption check-ups (n = 2), well-baby examinations, and symptoms (n = 1).

Number of physician visits required for TB diagnosis for persons reporting symptoms.

Source of Infection

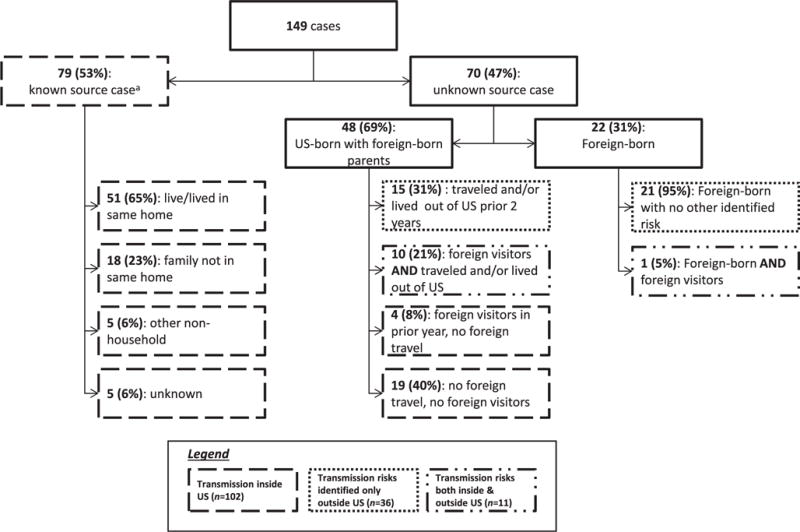

Conservatively, 102 (68%) of the participants contracted TB in the United States (Table 3), 79 with known source cases and 23 with no foreign travel (4 with foreign visitors in the previous year and 19 without) (Fig 1). Thirty-six children (24%) had TB transmission risks only outside the United States (21 foreign born with no other identified risk factors, 15 with foreign travel in the 2 years before diagnosis). Eleven children (7%) had foreign visitors and foreign travel. US-born children were nearly 10 times as likely as foreign-born children to have been infected in the United States (Table 3).

FIGURE 1.

Sources of TB infection for 149 children <5 years old who were foreign born or had foreign-born parents and were diagnosed with TB in 20 US jurisdictions 2005–2006.a Three of 5 foreign-born children had history of previous travel or foreign-born visitors. Of the 74 US-born children, 1 had lived outside the United States, 10 had travelled outside the United States, 16 reported foreign-born household visitors, and 50 (68% of 74) had no risks identified other than known contact to active TB in the United States.

Source Case Characteristics

Seventy-nine children (53%) in the observational study had known source cases. Fifty-one (65%) of the source cases lived in the child’s household. The source case was diagnosed first for 54 (68%) children and the child was diagnosed first for 16 (20%). The timing of diagnosis relative to the source was unknown for 9 children, including 2 in whom the epidemiologic linkage was confirmed through Mycobacterium tuberculosis genotyping.

Source cases for 52 (66%) of the 79 children were enrolled in the study; 6 of the source cases infected 2 different enrolled children each. Among the 46 unique enrolled source cases (Table 5), 42 (91%) were foreign born, including at least 38% who were undocumented at diagnosis. The median time from US entry to TB treatment initiation was 5.3 years (interquartile range [IQR] 2.7–13.1). Most source cases reported cough (91%) and were acid-fast bacilli sputum smear positive (89%) or M tuberculosis sputum culture positive (98%). For 3 enrolled US-born children with only clinically confirmed TB, the 2 foreign-born source cases had MDR TB. The median time from the source case’s symptom onset to the source case’s treatment initiation was 105 days (IQR 72–190 days), to the child’s treatment initiation was 132 days (IQR 101–212 days, Table 5).

TABLE 5.

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of 46 Persons With TB Who Were Identified as the Source of Transmission for 52 Children With TB Enrolled in the Observational Study

| Source Case Characteristic | n (N%) |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Male | 18 (39) |

| Female | 28 (61) |

| Age at treatment initiation, median (IQR) | 30.9 (25.2–39.6) |

| Country or world region of birth | |

| United States | 4 (9) |

| Latin America/South America/Caribbean | 9 (20) |

| Mexico | 24 (52) |

| Sub-Saharan Africa | 3 (6) |

| South Asia/East Asia/Pacific | 6 (13) |

| Speaks English “not at all” | 15 (33) |

| Sputum smear positive for acid-fast bacilli | 41 (89) |

| Sputum culture positive for TB | 45 (98) |

| Chest radiograph abnormality | |

| Cavitary | 28 (61) |

| Noncavitary consistent with TB | 17 (37) |

| Unknown | 1 (2) |

| Reason for seeking care | |

| Symptoms | 37 (80) |

| Contact investigation | 7 (15) |

| Other (regular check-up and pregnancy/child birth) | 2 (4) |

| Reported cough | |

| Yes | 42 (91) |

| No | 4 (9) |

| Years from source case’s US entry to TB treatment initiation (N = 42), median (IQR) | 5.3 (2.7–13.1) |

| Days from source case’s onset of symptoms to treatment initiation (N = 41); median (IQR) | 105 (72–190) |

| Days from source case’s onset of symptoms to child’s TB treatment initiation (N = 47),a median (IQR) | 132 (101–212) |

| Days from source case’s TB treatment initiation to child’s TB treatment initiation (N = 52),a median (IQR) | 11.5 (1–33.5) |

| Visa status at interview (N = 42) | |

| Undocumented | 16 (38) |

| Temporary | 5 (12) |

| Permanent | 18 (43) |

| Unknown | 3 (7) |

| Overseas medical examination before US entry (N = 42) | |

| Yes | 10 (24) |

| No | 29 (69) |

| Unknown | 3 (7) |

| US medical examination to change visa (N = 42) | |

| Yes | 5 (12) |

| No | 37 (88) |

Multiple children infected by source case.

DISCUSSION

TB in young children is of particular clinical and programmatic concern because (1) such cases are markers for recent or ongoing transmission, (2) young children are more likely to progress from infection to disease, and (3) young children are more likely to develop severe manifestations of TB, such as meningeal or miliary disease.15,16

Foreign-born children have long been known to be at high risk of TB and have been a focus of prevention efforts.17,18 But the risk of TB among children of foreign-born parents has been harder to define because of the difficulty of obtaining parental birth information and population denominators.

This is the first US study to calculate TB rates among children younger than 5 years by national origin of both the children and their parents. The study found that the TB rate for young children who are US born but have at least 1 foreign-born parent was more than 6 times that of US-born young children with US-born parents. Although foreign-born children had higher TB rates, they accounted for only 1.8% of the total population of children <5 years old and 17% of TB cases in young children. Most TB cases (53%) in young children were reported among the 29% of the US population of young children with at least 1 foreign-born parent. This pediatric population should be a focus of TB prevention and control efforts.

Routine ascertainment of children’s and parents’ countries of birth can help identify children at risk for both TB and latent TB infection (LTBI). It took a median of 52 days to initiate TB therapy for the symptomatic children in this study. Unfortunately, symptoms such as fever and cough are also seen in the more common viral upper respiratory infections, making it difficult to select young children who should be further evaluated for TB. We propose that young children who are foreign born or US born with foreign-born parents be assessed for TB if they have coughs lasting for >3 weeks and are not experiencing clinical improvement.15,19–21

Even though specimen collection from young children is challenging, confirming TB diagnosis and identifying drug susceptibilities is critical. In our study, PZA-resistant M tuberculosis complex strains were associated with a parent being born in Mexico and with consumption of unpasteurized dairy products, suggesting infection with Mycobacterium bovis. Speciation to confirm M bovis was not performed, but all children with PZA-resistant mycobacterial disease had extrapulmonary involvement, an epidemiologic characteristic of M bovis disease, and many had eaten unpasteurized dairy products, a known source of M bovis infection.22 If culture cannot be obtained, these epidemiologic and clinical characteristics can help support a diagnosis of PZA-resistant TB.

The importance of prioritizing young pediatric contacts for evaluation in contact investigations23 is underscored by our finding that more than one-third of the children in the observational study were diagnosed that way.

Prevention of TB in young children also requires preventing TB transmission from adults to children. In the observational study, more than 60% of US-born children had an identified source case, but a substantial amount of time was required to initiate treatment of these source cases: a median of 105 days from symptom onset. Earlier identification of the adult source case might have prevented transmission to these children or allowed for preventive treatment before the children’s infections had progressed to disease. Factors associated with longer time to treatment initiation could include declining public health funding, which would reduce resources required for extensive and detailed contact tracing and source case investigations.24 Other factors might be barriers to care that are unique to foreign-born populations; many of the individuals who were identified source cases in this study did not speak English, were undocumented immigrants, and expressed fears of deportation.

Although early diagnosis and prompt treatment of TB disease is a primary component of TB control, it is preferable to prevent TB disease through (1) identification, screening, and LTBI testing of children at high risk and (2) treatment of infected children. Testing of children who do not have TB risk factors is strongly discouraged because of a low yield of positives and a high yield of false-positives.17 In response to the need for easily administered screening instruments, questionnaires have been developed and validated for screening children <18 years old in clinics and office-based practices; those determined to be at high risk can be tested for LTBI.17,19,25 These questionnaires ask about presence of a household member born outside the United States, child’s birth place and foreign travel, foreign visitors to the child’s household, and other risk factors. Different questions and combinations of questions have been associated with different levels of sensitivity and specificity. The high rates of TB in young children who are foreign born or have foreign-born parents suggest that, at least for children <5 years old, all those who are born in countries with moderate to high TB rates (eg, Asia, Middle East, Africa, Latin America, and countries of the former Soviet Union), or have a parent who was born in such a country, should be considered for LTBI testing, regardless of responses to other questions.26 Of note, although 1 set of current guidelines for LTBI testing in children recommends testing of children with recent foreign travel to countries with high TB rates,23 more than two-thirds of the children in our observational study were exposed in the United States. In an effort to curtail importation of TB cases among US immigrants, the CDC’s Division of Global Migration and Quarantine in 2007 revised the prearrival requirements for immigrant children and refugees to require that all children ages 2 to 14 be tested for TB infection and, if positive, screened for TB with a chest radiograph.27,28 Although this change will help identify both children with TB and those who could benefit from LTBI treatment in the United States, it will not help those children who acquire infection after arrival.

An important issue is the generalizability of the study’s calculated TB rates to the nation as a whole, as the population studied was not a national sample. However, the sample was drawn from 16 states and represented almost half of all TB cases diagnosed in young children in the United States during the study enrollment years. Moreover, the calculated overall rate of 2.57 per 100 000 young children in the study jurisdictions is similar to the national rate of 2.38 per 100 000 in 2005–2007.29 Although parental origin was unknown for 33 US-born children, a sensitivity analysis that assigned those children to US or foreign parentage changed the estimated TB rates only modestly.

A limitation of the observational study is that only ~60% of eligible cases were enrolled, and US-born children were more likely to be enrolled; to the extent that children with particular characteristics (eg, age, site of disease) were differentially enrolled by nativity, this could affect study comparisons. However, the clinical characteristics of the study population were consistent with those previously reported for pediatric TB, including (1) the proportion and types of extrapulmonary TB overall and by age group, (2) the higher prevalence of PZA resistance among children of Mexican descent, and (3) the proportion of laboratory-confirmed cases (30% in the study, 25% nationally, P = .15).16,30–32

An additional limitation to the observational study is that source cases were identified through epidemiologic links; it is unclear how many were confirmed by genotyping. However, other studies have shown tight concordance (85%–91%) between genotyping results and epidemiologic data in patient-source case pairs for young children.33,34 Finally, PZA analysis was limited by missing data.

CONCLUSIONS

Ultimately, prevention of TB in young children will require more effective testing and treatment of adults at high risk of LTBI, so they do not develop TB and transmit it to young children.35 Foreign-born adults represent the largest high-risk population in the United States.7 All medical providers should assess patients’ country of birth routinely as part of any clinical encounter. This practice will identify persons likely to have LTBI and TB disease; treatment will prevent disease transmission.

Supplementary Material

WHAT’S KNOWN ON THIS SUBJECT

More than 60% of all US tuberculosis cases occur among foreign-born persons, but ~90% of cases in young children occur among US-born; many of these children have foreign-born parents, suggesting that this is an important population for prevention.

WHAT THIS STUDY ADDS

This is the first study to calculate tuberculosis rates in US-born children by parental nativity. Compared with US-born children with US-born parents, rates were 32 times higher in foreign-born children and 6 times higher in US-born children with foreign-born parents.

Acknowledgments

We thank the investigators and staff at all the participating TBESC sites: James McAuley, MD, MPH, Sharon Welbel, MD, Judith Beison, BS, Chicago, IL; Frank Wilson, MD, MPH, Cheryl LeDoux, MT, MPH, Little Rock, AR; Jennifer Flood, MD, MPH, Sumi Sun, MPH, Richmond, CA; Holly Anger, MPH, Paul Colson, PhD, Yael Hirsch-Moverman, PhD, MPH, Hugo Ortega, BA, Jiehui Li, MBBS, MSc, New York, NY; Lourdes Yun, MD, MSPH, Denver, CO; Jane Tapia, BSN, Atlanta, GA; Jessie Wing, MD, MPH, Honolulu, HI; Wendy Cronin, PhD, Susan Dorman, MD, Frances Maurer, BSN, MS, Baltimore, MD; Sue Etkind, RN, MS, Sharon Sharnprapai, MS, John Bernardo, MD, C. Robert Horsburgh Jr, MD, Arnaud Barbosa, Boston, MA; Wendy Sutherland, MPH, Hodan Guled, MPH, Jane Schulz, RN, MPH, Sarah Solarz, MPH, Minneapolis, MN; John Grabau, PhD, MPH, Margaret Oxtoby, Stephen Hughes, PhD, Albany, NY; Rachel Royce, PhD, MPH, Carol Dukes-Hamilton, MD, Research Triangle Park, NC; Connie Haley, MD, MPH, Jon Warkentin, MD, MPH, Tamara Chavez-Lindell, MPH, Nashville, TN; Stephen Weis, DO, Patrick Moonan, DrPH, Guadalupe Munguia, MD, MPH, Fort Worth, TX; Ashutosh Tamhane, MD, PhD, MSPH, Birmingham, AL; Nandini Selvam, MPH, PhD, Anna Sevilla, MPH, Newark, NJ; Gary Goldbaum, MD, MPH, Masa Narita, MD, Seattle, WA; Lisa Pascopella, PhD, MPH, L. Masae Kawamura, MD, Baby Djojonegoro, MPH, San Francisco, CA; Charles Wallace, PhD, Austin, TX; Frank Valdez Jr, Yuly Orozco, Houston, TX; Izelda Zarate, Brownsville, TX; Marie McMillan, RN, Kesner Accime, Ft Lauderdale, FL.

The authors also thank Andrea T Cruz, MD, MPH, for her critical review of the manuscript, as well as the CDC project coordinator Lolem Ngong, MPH.

FUNDING: Funded by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

ABBREVIATIONS

- CDC

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

- CI

confidence interval

- DST

drug susceptibility test

- IQR

interquartile range

- LTBI

latent tuberculosis infection

- MDR

multidrug-resistant

- PZA

pyrazinamide

- TB

tuberculosis

- TBESC

Tuberculosis Epidemiologic Studies Consortium

Footnotes

Drs Katz, Davidow, and Reves conceptualized and designed the study, and critically reviewed the manuscript; Drs Pang, Teeter, and Graviss participated in data collection and analytic planning, carried out the analyses, and drafted the initial manuscript; Mr Miranda, Ms Wall, Ms Ghosh, Ms Stein-Hart, and Dr Restrepo participated in data collection and analytic planning, and reviewed and revised the manuscript; and all authors approved the final manuscript as submitted.

The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

FINANCIAL DISCLOSURE: The authors have indicated they have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

POTENTIAL CONFLICT OF INTEREST: The authors have indicated they have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Lobato MN, Mohle-Boetani JC, Royce SE. Missed opportunities for preventing tuberculosis among children younger than five years of age. Pediatrics. 2000;106(6) doi: 10.1542/peds.106.6.e75. Available at: www.pediatrics.org/cgi/content/full/106/6/e75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) NCHHSTP Atlas. Available at: www.cdc.gov/nchhstp/atlas/. Accessed Apr 23, 2013.

- 3.Khan EA, Starke JR. Diagnosis of tuberculosis in children: increased need for better methods. Emerg Infect Dis. 1995;1(4):115–123. doi: 10.3201/eid0104.950402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Smith KC. Tuberculosis in children. Curr Probl Pediatr. 2001;31(1):1–30. doi: 10.1016/s1538-5442(01)70040-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Reported Tuberculosis in the United States, 2009. Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services, CDC; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Reported Tuberculosis in the United States, 2010. Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services, CDC; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Reported Tuberculosis in the United States, 2011. Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services, CDC; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kenyon TA, Driver C, Haas E, Valway SE, Moser KS, Onorato IM. Immigration and tuberculosis among children on the United States-Mexico border, County of San Diego, California. Pediatrics. 1999;104(1) doi: 10.1542/peds.104.1.e8. Available at: www.pediatrics.org/cgi/content/full/104/1/e8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Winston CA, Menzies HJ. Pediatric and adolescent tuberculosis in the United States, 2008–2010. Pediatrics. 2012;130(6) doi: 10.1542/peds.2012-1057. Available at: www.pediatrics.org/cgi/content/full/130/6/e1425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Davidow AL, Katz D, Reves R, Bethel J, Ngong L, Tuberculosis Epidemiologic Studies Consortium The challenge of multisite epidemiologic studies in diverse populations: design and implementation of a 22-site study of tuberculosis in foreign-born people. Public Health Rep. 2009;124(3):391–399. doi: 10.1177/003335490912400308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Katz D, Albalak R, Wing JS, Combs V, Tuberculosis Epidemiologic Studies Consortium Setting the agenda: a new model for collaborative tuberculosis epidemiologic research. Tuberculosis (Edinb) 2007;87(1):1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.tube.2005.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kominski R. How good is “How well”? An examination of the Census English-speaking ability question. Paper presented at: the American Statistical Association annual meeting; Aug 6–11, 1989; Washington, DC. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stuart A, Ord K. Kendall’s Advanced Theory of Statistics, Distribution Theory. 6th. Vol. 1. London, UK: Arnold; 1998. p. 351. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Elandt-Johnson RC, Johnson NL. Survival Models and Data Analysis. New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons; 1980. p. 69. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Munoz FM, Starke JR. Tuberculosis in children. In: Reichman LB, Hershfield ES, editors. Tuberculosis: a Comprehensive International Approach. 2nd. New York, NY: Marcel Dekker, Inc; 2000. pp. 553–586. [Google Scholar]

- 16.CDC. Slide sets—Epidemiology of pediatric tuberculosis in the United States, 1993–2008 (Slide 19) Available at: www.cdc.gov/tb/publications/slidesets/pediatricTb/default.htm. Accessed March 11, 2013.

- 17.Pediatric Tuberculosis Collaborative Group. Targeted tuberculin skin testing and treatment of latent tuberculosis infection in children and adolescents. Pediatrics. 2004;114(supp 4):1175–1201. [Google Scholar]

- 18.American Academy of Pediatrics. Tuberculosis. In: Pickering LK, Baker CJ, Kimberlin DW, Long SS, editors. Red Book: 2012 Report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases. Elk Grove Village, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics; 2012. p. 740. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Froehlich H, Ackerson LM, Morozumi PA, Pediatric Tuberculosis Study Group of Kaiser Permanente, Northern California Targeted testing of children for tuberculosis: validation of a risk assessment questionnaire. Pediatrics. 2001;107(4) doi: 10.1542/peds.107.4.e54. Available at: www.pediatrics.org/cgi/content/full/107/4/e54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Marchant JM, Masters IB, Taylor SM, Chang AB. Utility of signs and symptoms of chronic cough in predicting specific cause in children. Thorax. 2006;61(8):694–698. doi: 10.1136/thx.2005.056986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Marais BJ, Obihara CC, Gie RP, et al. The prevalence of symptoms associated with pulmonary tuberculosis in randomly selected children from a high burden community. Arch Dis Child. 2005;90(11):1166–1170. doi: 10.1136/adc.2004.060640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dankner WM, Davis CE. Mycobacterium bovis as a significant cause of tuberculosis in children residing along the United States-Mexico border in the Baja California region. Pediatrics. 2000;105(6) doi: 10.1542/peds.105.6.e79. Available at: www.pediatrics.org/cgi/content/full/105/6/e79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.National Tuberculosis Controllers Association; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Guidelines for the investigation of contacts of persons with infectious tuberculosis. Recommendations from the National Tuberculosis Controllers Association and CDC. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2005;54(RR-15):1–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.American Public Health Association. Budget cuts straining capacity of public health departments: services in demand. Nations Health. 2010;40:1–16. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ozuah PO, Ozuah TP, Stein REK, Burton W, Mulvihill M. Evaluation of a risk assessment questionnaire used to target tuberculin skin testing in children. JAMA. 2001;285(4):451–453. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.4.451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.American Thoracic Society. Targeted tuberculin testing and treatment of latent tuberculosis infection. This official statement of the American Thoracic Society was adopted by the ATS Board of Directors, July 1999. This is a Joint Statement of the American Thoracic Society (ATS) and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). This statement was endorsed by the Council of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. (IDSA), September 1999, and the sections of this statement. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000;161(4 pt 2):S221–S247. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.161.supplement_3.ats600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.CDC. Revised technical instructions for tuberculosis screening and treatment for panel physicians. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2008;57:292–293. [Google Scholar]

- 28.CDC. CDC immigration requirements: technical instructions for tuberculosis screening and treatment. Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services, CDC; 2009. Available at: www.cdc.gov/immigrantrefugeehealth/exams/ti/panel/tuberculosis-panel-technical-instructions.html. Accessed October 17, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 29.CDC. National Tuberculosis Surveillance System, United States, 1993–2010. US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Division of TB Elimination, CDC WONDER Online Database; Nov, 2012. OTIS 2010 TB Data Request. Available at: http://wonder.cdc.gov/tb-v2010.html. Accessed May 22, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Human tuberculosis caused by Mycobacterium bovis—New York City, 2001–2004. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2005;54(24):605–608. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hlavsa MC, Moonan PK, Cowan LS, et al. Human tuberculosis due to Mycobacterium bovis in the United States, 1995–2005. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;47(2):168–175. doi: 10.1086/589240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rodwell TC, Moore M, Moser KS, Brodine SK, Strathdee SA. Tuberculosis from Mycobacterium bovis in binational communities, United States. Emerg Infect Dis. 2008;14(6):909–916. doi: 10.3201/eid1406.071485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sun SJ, Bennett DE, Flood J, Loeffler AM, Kammerer S, Ellis BA. Identifying the sources of tuberculosis in young children: a multistate investigation. Emerg Infect Dis. 2002;8(11):1216–1223. doi: 10.3201/eid0811.020419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wootton SH, Gonzalez BE, Pawlak R, et al. Epidemiology of pediatric tuberculosis using traditional and molecular techniques: Houston, Texas. Pediatrics. 2005;116(5):1141–1147. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-2701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hill AN, Becerra J, Castro KG. Modelling tuberculosis trends in the USA. Epidemiol Infect. 2012;140(10):1862–1872. doi: 10.1017/S095026881100286X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.