Abstract

As a potential means to reduce proliferation of breast cancer cells, a multiple-pathway approach with no effect on control cells was explored. The human interactome being constructed by the Center for Cancer Systems Biology will prove indispensable to understanding composite effects of multiple pathways, but its discovered protein–protein interactions require characterization. Accordingly, we explored the effects of regulators of one protein on downstream targets of the other protein. MCF-7 estrogen receptor-positive (ER+) breast cancer cells were treated with raloxifene to upregulate the TGF-β pathway and PX-866 to down-regulate the PI3K/Akt pathway. This resulted in highly significant downstream reduction of cell cycle proliferation in breast cancer cells with no significant proliferation reduction following similar treatment of noncancerous MCF10A breast epithelial cells. Reduced phosphorylation of p107 and substantial reduction of Rb phosphorylation were observed in response. The effects of reduced Rb and p107 phosphorylation were reflected in significant decline in E2F-1 transcriptional activity, which is dependent on pocket protein phosphorylation status. The reduced proliferation was related to decreased expression of cyclins, including E2F-1-regulated Cyclin E2, which was also in response to raloxifene and PX-866. All combinations of raloxifene and PX-866 produced significant or highly significant results for reduced MCF-7 cell proliferation, reduced Cyclin E2 transcription, and reduced Rb phosphorylation. These studies demonstrated that uncontrolled proliferation of ER+ breast cancer cells can be significantly reduced by combinational targeting of two relevant pathways.

Keywords: PX-866, RALOXIFENE, TGF-β PATHWAY, PI3K/Akt PATHWAY, Rb PHOSPHORYLATION, p107, POCKET PROTEIN, PROLIFERATION, BREAST CANCER

Cancers are dependent on unlimited and unregulated repetition and progression of the mitotic cell cycle, an evolved process essential for multicellular life [Hartman and Fedorov, 2002]. The cell cycle and its regulation are administered by genes, gene products, and pathways of gene products necessary for its establishment, refinement, and maintenance [Tyson and Novak, 2001]. Human genes essential to cell cycle regulation include genes necessary for regulation of transition from G1 to S phase [Qu et al., 2003].

Transition from G1 depends on a vast number of gene products and pathways but most directly on the expression and activity of cyclins and cyclin-dependent kinases (CDKs) in cyclin/CDK complexes, limited by CDK inhibitors [Qu et al., 2003; Cobrinik, 2005]. The “pocket proteins” p107 and Rb are closely related in structure and regulate the transcriptional activity of the E2F family proteins, which have essential roles in regulation of G1 to S transition [Chen et al., 2002; Leng et al., 2002; Cobrinik, 2005]. Pocket proteins are characterized by their conserved pocket structured domains [Singh et al., 2005]. Multiple binding sites, including two sections within the pocket domain, accommodate mutual binding of E2F proteins, cyclins, and histone deacetylases (HDACs) [Sardet et al., 1995; Brehm et al., 1998; Lee et al., 1998; Chen et al., 2002; Singh et al., 2005]. Cell cycle regulation by p107 and Rb is dependent on which proteins bind at the pocket domain, where removal of binding partners may be induced by substitution of phosphate groups donated by complexes of CDK 2 or 4 with cyclin D, E, or A [Harbour et al., 1999; Leng et al., 2002; Chen et al., 2002; Cobrinik, 2005]. Although Rb and p107 activity is suppressed by phosphorylation disassociating E2F proteins from pocket proteins, reduced expression of E2F-1-induced cyclins results from HDACs recruited to the E2F-1 promoter by Rb [Brehm et al., 1998; Leng et al., 2002; Cobrinik, 2005].

As the level of tissue growth and cell reproduction, critical to the event and/or progression of growth-related diseases such as cancer, is regulated by networks of interacting pathways [Stevens et al., 2013], we have investigated the potential down-regulation of cell cycle progression by treatment of cultured human cancer cells with a combination of an activator of an inhibitory pathway (TGF-β), mediated in part by p107, and an inhibitor of an activating pathway (PI3K/Akt) [Testa and Bellacosa, 2001; Chen et al., 2002]. For upregulation of TGF-β pathway activity, we used raloxifene, a selective estrogen receptor modulator (SERM) which competes with 17-β-estradiol (E2) for binding the estrogen receptor ERα and the cytoplasmic estrogen receptor GPR30 and which has been approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for use in breast cancer prevention [Cherlet and Murphy, 2007; LeBlanc et al., 2007; Kleuser et al., 2008; Sasaki et al., 2008]. Preliminary gel-based PCR testing in our lab had shown raloxifene to be optimally effective in gene regulation at 1.0 µM, previously determined to be physiologically relevant [Sasaki et al., 2008]. For down-regulation of the PI3K/Akt pathway we used gradient concentrations of PX-866, a derivative of wortmannin and an inhibitor of the p110α unit of phosphoinositide-3-kinase, currently in multiple clinical trials [Ihle et al., 2004].

MATERIALS AND METHODS

CELL CULTURES, REAGENTS, AND PROCEDURES

Human cell lines were purchased from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Manassas, VA) and included ER-expressing MCF-7 breast cancer epithelial cells and hTERT-expressing but nontumorigenic MCF10A breast epithelial cells. MCF-7 cells were maintained in Dulbecco′s modified Eagle′s medium (DMEM) (Mediatech, Manassas, VA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Atlanta Biologicals, Lawrenceville, GA) and 10% APS (amphotericin B, penicillin, and streptomycin) (Mediatech) and treated in phenol red-free DMEM supplemented also with 0.01 µM β-estradiol (E2) (Sigma–Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) [Cherlet and Murphy, 2007]. MCF10A cells were grown in DMEM/F12 media (Mediatech) with supplementation by 5% horse serum, 0.02 µg/mL EGF, 10 µg/mL insulin, 0.001 µg/mL cholera toxin, 100 µg/mL hydrocortisone, and 50 µg/mL penicillin-streptomycin [Muthuswamy et al., 2001]. Charcoal dextran treatment of serum in media can improve the accuracy of comparisons involving induced hormone level differences and improve precision of comparisons with or without known hormone level differences [Lindquist and de Alarcon, 1987; Tee et al., 2004; Zheng et al., 2006]. Experiments using additional cell types will also be needed.

MCF-7 cells were treated on 3 consecutive days, with media replacement daily, and harvested 18 h after the latest treatment. The cells were treated with 1.0 µM raloxifene, with 0.4 µM PX-866, with 1.0 µM raloxifene in combination with 0.1, 0.4, or 0.8 µM PX-866, or only as control/vehicle with 21 µL DMSO, the median DMSO volume in treatments. With longer treatment, recovery of cell lysates was inconsistent, but testing for time-dependency will, nevertheless, be needed. Raloxifene (Sigma–Aldrich) stock was maintained at room temperature at 54.9 mM concentration. PX-866 (BioVision) was maintained at 190 µM concentration at temperature −20°C and protected from light. Relevant and physiologically appropriate treatment dosages of raloxifene and PX-866 were chosen based on previous testing [Sasaki et al., 2008; Koul et al., 2010], including gel-based PCR in our laboratory (data not shown).

RNA QUANTIFICATION BY REAL-TIME PCR

Total cellular RNA was harvested from cultured cells using RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) in accordance with the manufacturer′s protocol. cDNA was synthesized from RNA using iScript cDNA Synthesis Kit (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA) in accordance with the manufacturer′s instructions. Primers used for real-time PCR were previously tested and validated for the genes Cdc6 [Wu et al., 2009], Cyclin E2 [Wu et al., 2009], E2F-1 [Pulikkan et al., 2010], IL-11 [Onnis et al., 2013], p27 [Su et al., 2013], MAGE-A11 [Minges et al., 2013], and GAPDH [Meeran et al., 2010]. RNA expression from three or more experiments for each gene and treatment was measured by real-time PCR using the CFX Connect system (Bio-Rad Laboratories). Gene-specific RNA expression fold change relative to untreated control cells was determined by the Delta–Delta Ct method [Livak and Schmittgen, 2001], using GAPDH as the reference gene.

QUANTIFICATION OF PROTEIN AND MODIFIED PROTEIN BY WESTERN BLOT

Protein was extracted from cultured MCF-7 cells harvested using RIPA Lysis Buffer (Upstate Biotechnology, Charlottesville, VA) in accordance with the manufacturer′s instructions. Equal amounts of protein were electrophoresed on Mini-PROTEAN TGX Precast Gels (Bio-Rad Laboratories) with Precision Plus Protein Kaleidoscope Standards (Bio-Rad Laboratories) as molecular weight marker. Transfer from gel to nitrocellulose membrane was performed using the Trans-Blot Turbo Transfer System, according to the manufacturer′s protocol (Bio-Rad Laboratories). Blocking and incubation with primary and secondary antibodies was performed using the SNAP i.d. 2.0 Protein Detection System (EMB Millipore Corporation, Billerica, MA) according to the manufacturer′s protocol. Primary antibodies included p107 (C-18): sc-318 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA), against the C-terminal region of human protein p107, p-p107 (Ser 975): sc-130209 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), against human protein p107 phosphorylated at Serine 975, Rb (C-15): sc-50 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), against the C-terminal region of Rb, p-Rb (Ser 807): sc-293117 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), against an Rb sequence containing phosphorylated Ser 807, Cyclin E2 (H-140): sc-22777 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), against the N-terminal region of human protein Cyclin E2 and #4970 (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA), against the human protein β-actin. Secondary antibodies #AP 182P (Millipore) against rabbit IgG, were conjugated with horseradish peroxidase (HRP), and substrate was provided by Bio-Rad Clarity Western ECL Substrate (Bio-Rad Laboratories). The image was developed with the ChemiDoc XRS+System with Image Lab software (Bio-Rad Laboratories), and the results were quantified and normalized by densitometry using ImageJ.

PROLIFERATION ANALYSIS BY MTT ASSAY

Cells were seeded in a 96-well plate at 10,000 cells and 200 µL of media per well. After 24 h of incubation, the media was replaced with media containing the same concentrations of vehicle or raloxifene and/or PX-866 as used in treatments for RNA and protein quantification. Following 72 h of treatment, the media in each well was replaced with 50 µL of MTT solution consisting of 1mg thiazolyl blue tetrazolium bromide (Sigma–Aldrich) per mL phosphate buffered saline (PBS), for an incubation of 4 h. The MTT was next replaced with 150 µL dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) for 10 min incubation and subsequent reading for 595 nm wavelength absorbance on iMark Microplate Absorbance Reader (Bio-Rad). The procedures were repeated for MCF-7 cells and for MCF10A cells.

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

Three independent experiments were used to determine all numerical values. Statistical significance between control groups was evaluated using Student′s t-test and the provided values include mean ± SE. Values of P for determining significance were calculated by formula using Microsoft Excel, with P < 0.05 considered significant and P < 0.01 considered highly significant. GAPDH was used as the reference gene for mRNA normalization and β-actin for protein quantified by densitometry.

RESULTS

RALOXIFENE AND PX-866 REDUCED PROLIFERATION OF MCF-7 BUT NOT MCF10A CELLS

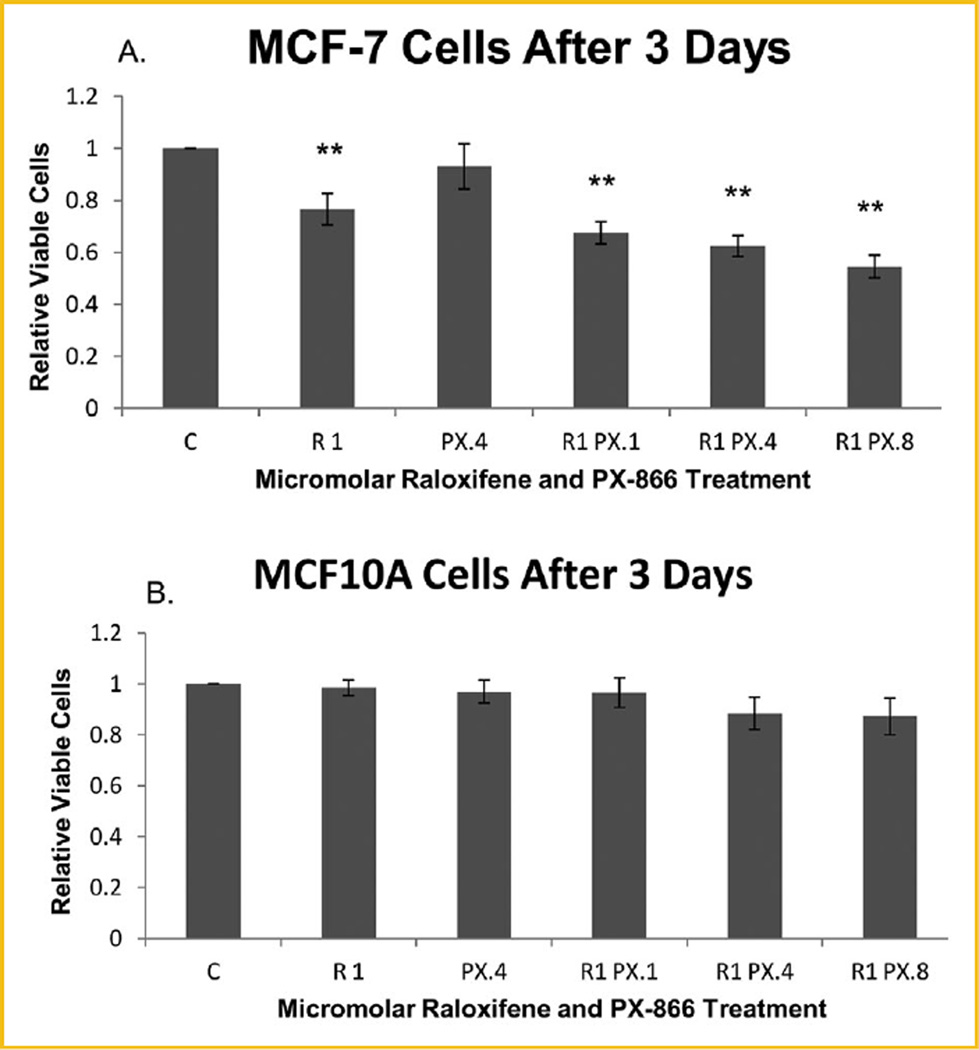

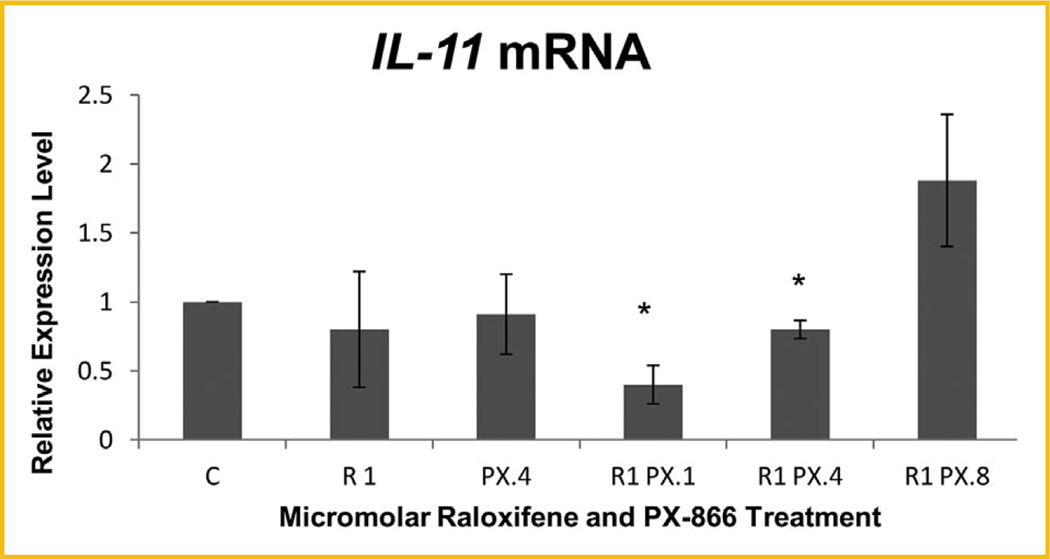

MTT was performed to assess the proliferation of both MCF-7 ER+ breast cancer cells and MCF10A hTERT-expressing noncancerous breast epithelial cells treated with raloxifene, PX-866, or combinations of both. As shown in Figure 1A, highly significant reduction of the proliferation of viable MCF-7 cells relative to untreated control cells was observed after 72 h for all cells treated with raloxifene alone or with raloxifene in combination with any concentration of PX-866. The reduction was enhanced significantly as the PX-866 concentration increased. In contrast, Figure 1B shows that no significant reduction was seen in the same time frame for noncancerous MCF10A cells undergoing the same treatments. Having shown highly significant reduction of proliferation with raloxifene-PX-866 combinations, we examined the mechanism of the reduction, including whether it was significantly due to decreased E2F-1-regulated transcription. Among our early experimental findings, we discovered that combinations of raloxifene and PX-866 significantly reduced the transcription level of oncogene Interleukin-11 (IL-11) (Fig. 2).

Fig. 1.

Raloxifene and PX-866 reduced MCF-7 but not MCF10A cell proliferation following three consecutive days of treatments. C, control; R1, raloxifene 1.0 µM; PX.1, PX-866 0.1 µM; PX.4, PX-866 0.4 µM; PX.8, PX-866 0.8 µM. Proliferation and viability of treated MCF-7 and MCF10A cells in MTT assay. (A) MCF-7 cells treated with raloxifene alone were highly significantly reduced after 72 h to 76.6% of the level of untreated control cells. After the same 72 h, MCF-7 cells treated with raloxifene in combination with 0.1, 0.4, or 0.8 µM PX-866 were highly significantly reduced to 67.5%, 62.4% or 54.5%, respectively, with the reduction of viable cell proliferation increasing with PX-866 dose increase. (B) No significant reduction of proliferation of viable MCF10A cells was observed with the same treatments for the same 72 h duration. Values represent averages from three independent experiments ±SEM. *P < 0.05. **P < 0.01.

Fig. 2.

Raloxifene- and PX-866-reduced IL-11 transcription levels following 3 consecutive days of treatments. Significant decrease in IL-11 transcription was seen following 3 days of treatment with 1.0 µM raloxifene in combination with 0.1 or 0.4 µM PX-866 in MCF-7 cells, with reduction to 40.3% and 80.2%, respectively, of the level of control cells. Values represent averages from three independent experiments ±SEM. *P < 0.05. **P < 0.01.

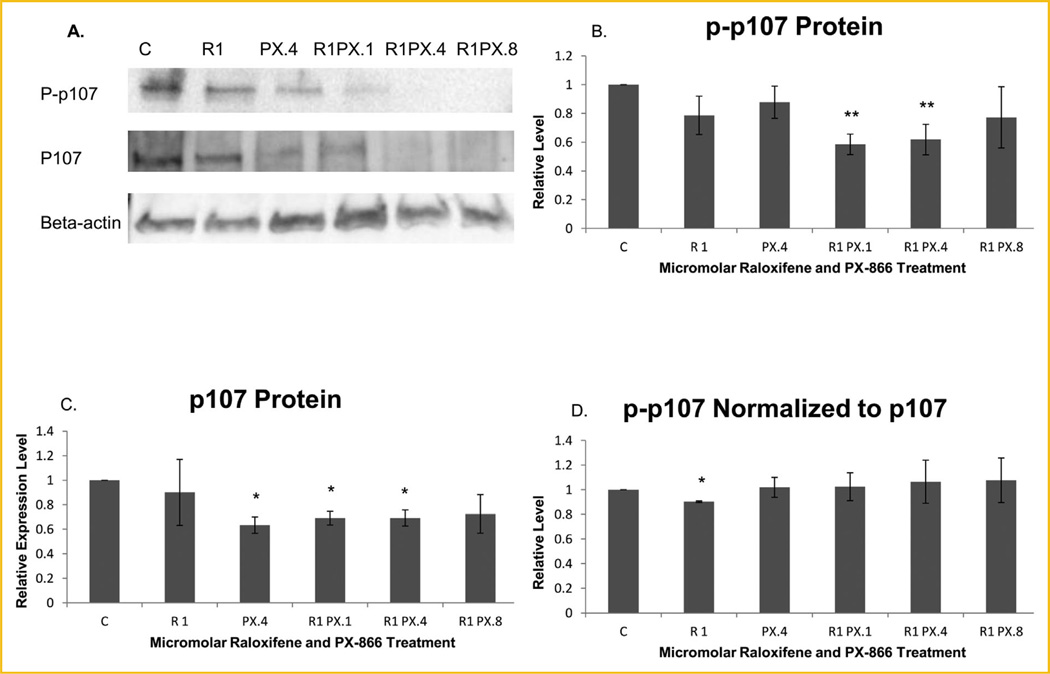

RALOXIFENE AND COMBINATIONS WITH PX-866 REDUCE THE PHOSPHORYLATION AND EXPRESSION OF POCKET PROTEIN p107

We examined whether the treatments altered the level of phosphorylation of p107. As shown in Figure 3B, a highly significant reduction of phosphorylated p107 was observed in MCF-7 cells treated with 1.0 µM raloxifene in combination with 0.1 or 0.4 µM PX-866, measured at 58.5% and 61.8%, respectively, of the level for untreated control cells, according to ImageJ computations. To determine whether the treatments reduced the phosphorylation or simply reduced the expression of p107 protein, we evaluated the level of total p107 protein (both phosphorylated and unphosphorylated) by Western blot. As shown by Figure 3C, a significant level of reduction of total p107 protein was seen for treatments with 0.4 µM PX-866 used alone or with raloxifene in combination with either 0.1 or 0.4 µM PX-866. To determine whether the reduction of phosphorylated p107 indicated a reduction of phosphorylation, we measured phosphorylated p107 normalized in ImageJ to total p107 instead of normalized to the reference protein β-actin. As shown in Figure 3D, the normalization to total p107 indicated that an actual reduction of phosphorylation resulted only in cells treated with raloxifene alone.

Fig. 3.

Immunoblotting analyses show reduced p107 expression and phosphorylation following three day treatments. (A) Western blot images of phosphorylated p107 (P-p107), total p107 protein without regard for phosphorylation (P107) and β-actin. Representative images shown are from the gels used to derive the densitometry averages represented in B–D. (B) Densitometry showed that phosphorylated p107, normalized to β-actin, was highly significantly reduced following 3 days of treatment with 1.0 µM raloxifene in combination with 0.1 or 0.4 µM PX-866. (C) Total p107 protein normalized to β-actin was significantly reduced following three days of treatment with 0.4 µM PX-866 alone or with 0.1 or 0.4 µM PX-866 in combination with 1.0 µM raloxifene. (D) The decrease in phosphorylated p107 was compared to the decrease in total p107 by normalizing p-p107 to total p107, rather than to β-actin. The calculated results showed that only cells treated with raloxifene alone specifically exhibited significant reduction of p107 phosphorylation. Values represent averages from three independent experiments ±SEM. *P < 0.05. **P < 0.01.

RALOXIFENE-PX-866 COMBINATIONS REDUCED THE TRANSCRIPTION OF E2F-1-REGULATED GENES E2F-1, CDC6, AND CYCLIN E2, ESSENTIAL TO G1-S TRANSITION

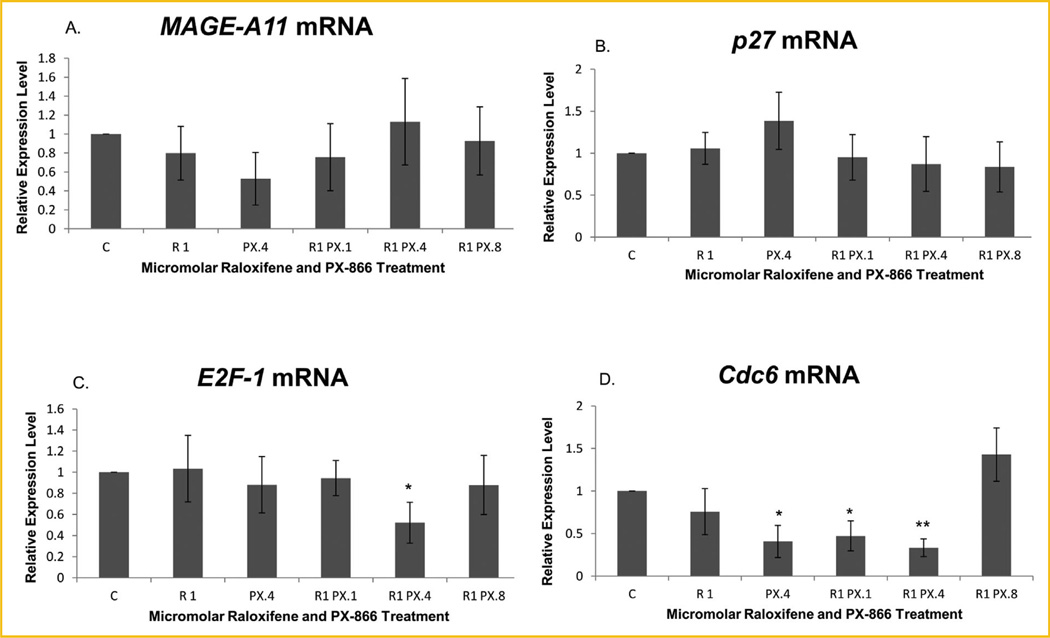

We next used real-time PCR to measure whether the mRNA expression levels of four targets of E2F-1 transcriptional activity were affected by the treatments and whether the level of MAGE-A11 itself might, in fact, be affected. As shown in Figure 4A, there was no significant change in the level of MAGE-A11 expression, at least not at the level of transcription, due to treatment with raloxifene and/or PX-866.

Fig. 4.

Real-time PCR revealed reduced transcription levels of some E2F-1 regulated genes in treated MCF-7 cells. (A) MAGE-A11 and (B) p27 were not significantly altered by treatments with raloxifene and/or PX-866. The transcription level of (C) E2F-1 was significantly reduced only by treatment with 1.0 µM raloxifene in combination with 0.4 µM PX-866, to 56.0% of the level of control cells. The (D) Cdc6 transcription level relative to control cells was significantly reduced by 0.4 µM PX-866 alone and by 0.1 µM PX-866 in combination with raloxifene to 40.7% and 47.3%, respectively, and highly significantly reduced by 0.4 µM PX-866 in combination with raloxifene to 33.4% of the level of control cells. Values represent averages from three independent experiments ±SEM. *P < 0.05. **P < 0.01.

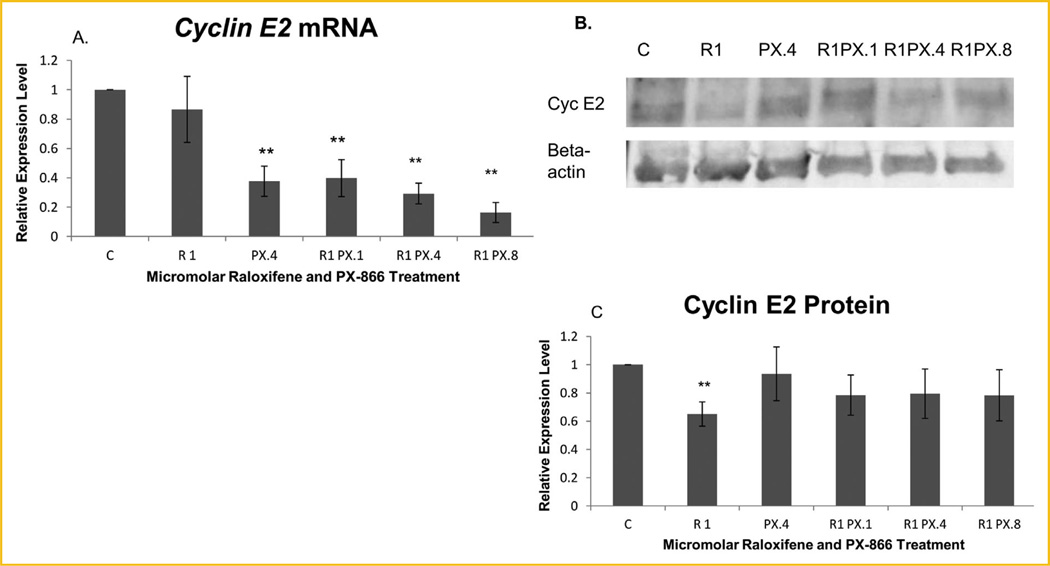

Significant mRNA reduction was observed for three of the E2F-1-regulated genes examined. Figure 4B shows no significant treatment-induced transcription change of the p27 CDK inhibitor. A significant transcription decrease for E2F-1 was observed when MCF-7 cells were treated with 1.0 µM raloxifene in combination with 0.4 µM PX-866, as shown in Figure 4C. As shown in Figure 4D, significant decreases in the level of transcription of Cdc6 were observed when MCF-7 cells were treated with raloxifene in combination with 0.1 or 0.4 µM PX-866 or with 0.4 µM PX-866 alone. In contrast to the more limited effects on other E2F-1-regulated genes, Figure 5A shows that there was highly significant reduction of Cyclin E2 following treatment with PI3K inhibitor PX-866 either alone at 0.4 µM or at any concentration (0.1, 0.4, or 0.8 µM) in combination with raloxifene.

Fig. 5.

PX-866-reduced Cyclin E2 expression at the mRNA level and raloxifene at the protein level. (A) The Cyclin E2 mRNA level in treated MCF-7 cells was highly significantly decreased to 37.7% of the level in untreated control cells by treatment with PX-866 alone and to 40.0%, 29.3%, and 16.4% by treatment with 0.1, 0.4 and 0.8 µM PX-866, respectively, in combination with 1.0 µM raloxifene. (B) Western blot images of Cyclin E2 (Cyc E2) and β-actin. (C) Significant reduction of Cyclin E2 protein in treated MCF-7 cells, like the reduction of p107 phosphorylation, was seen only in samples treated with raloxifene alone, in spite of highly significant transcription reduction using PX-866 alone or in combination. A highly significant reduction of Cyclin E2 to 65.1% relative to the β-actin reference protein was observed using 1.0 µM raloxifene. The effects of raloxifene were more notable at the protein level while the effects of PX-866 were more notable at the transcription level. Values represent averages from three independent experiments ±SEM. *P < 0.05. **P < 0.01.

We performed Western blot analysis to confirm the highly significant down-regulation of Cyclin E2 following treatment with raloxifene and/or PX-866. As shown by Figure 5C, highly significant reduction of Cyclin E2 protein was exhibited but was observed following treatment with raloxifene alone and not following treatment with PX-866 either alone or in combination.

RALOXIFENE AND PX-866 COMBINATIONS REDUCED THE EXPRESSION AND PHOSPHORYLATION OF THE Rb POCKET PROTEIN ESSENTIAL TO E2F-1 MEDIATED G1-S TRANSITION

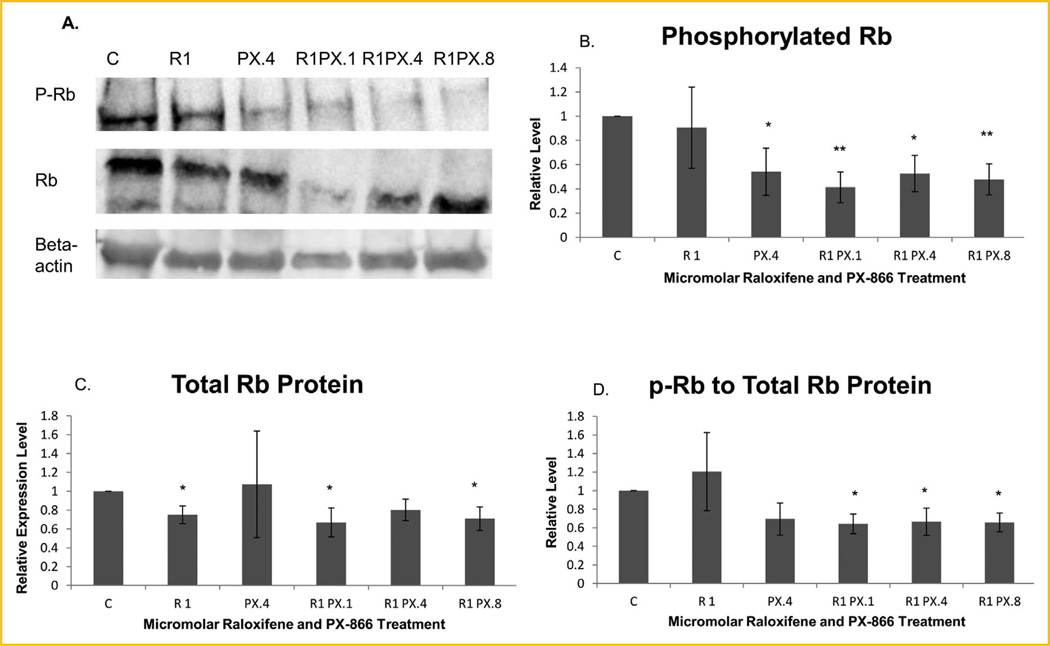

We extended our analysis of treatment effects on phosphorylation of p107 to the related pocket protein Rb. As shown in Figure 6B, phosphorylated Rb was significantly or highly significantly decreased in cells treated with 0.4 µM PX-866 alone or with 1.0 µM raloxifene in combination with any concentration of PX-866, 0.1, 0.4, or 0.8 µM. Phosphorylated Rb in cells treated with raloxifene in combination with 0.1 or 0.8 µM PX-866 was reduced to 41% or 48% of control cell concentrations, respectively. As shown by Figure 6C, total protein expression, as with p107, was also reduced significantly with some treatments, which included raloxifene alone or in combination with 0.1 or 0.8 µM PX-866. When phosphorylated Rb was normalized to total Rb protein expression, as shown in Figure 6D, a significant decrease in phosphorylated protein relative to total protein was exhibited for all cells treated with a combination of raloxifene and PX-866.

Fig. 6.

PX-866- and-raloxifene reduced Rb expression and phosphorylation. (A) Western blot images of phosphorylated Rb (P-Rb), total Rb (Rb) and β-actin. (B) Western blot showed that the phosphorylated Rb protein level was significantly reduced after treatment with PX-866 alone or with 0.4 µM PX-866 in combination with 1.0 µM raloxifene and highly significantly reduced following treatment with 0.1 or 0.8 µM PX-866 in combination with raloxifene. (C) Total Rb protein was significantly reduced following treatment with raloxifene alone or in combination with 0.1 or 0.8 µM PX-866. (D) Phosphorylated Rb relative to total Rb protein was significantly reduced following each combination of PX-866 and raloxifene treatment, to 64.2%, 66.5%, and 65.8% of the level of control cells by use of 0.1, 0.4 and 0.8 µM PX-866, respectively. Values represent averages from three independent experiments ±SEM. *P < 0.05. **P < 0.01.

DISCUSSION

Using the MTT assay, we showed that viable MCF-7 breast cancer cells were highly significantly reduced, relative to untreated control cells, after treatment with raloxifene alone or with raloxifene combined with tested concentrations of PX-866. In contrast, no significant reduction was observed after similar treatments of noncancerous MCF10A breast epithelial cells. We investigated whether the decrease in proliferation of viable MCF-7 cells was the result of a mechanism significantly decreasing E2F-1-mediated transcription regulation.

Both the phosphorylation and expression levels of p107 and Rb proteins, which mediate transcription regulation by E2F proteins [Dyson, 1998], were reduced by raloxifene and/or combinations with PX-866. The transcription levels of four genes transcriptionally regulated by E2F-1 were evaluated in treated and untreated cells using real-time PCR. The genes included Cdc6 and Cyclin E2, both essential to progression from G1 to S phase, the self-regulated E2F-1 gene, which provides cyclic positive feedback, and the CDK inhibitor p27 that serves in cyclic negative feedback [Johnson et al., 1994; Dyson, 1998; Yan et al., 1998; Wang et al., 2005]. Of these genes, E2F-1 transcription was significantly decreased in MCF-7 cells following treatment of one particular raloxifene-PX-866 combination. Cdc6 transcription was significantly reduced following use of two combinations or PX-866 alone. Cyclin E2 mRNA, in contrast, was reduced highly significantly by treatment with the PI3K inhibitor PX-866 used alone or in several concentrations in combination with raloxifene. The decrease in Cyclin E2 mRNA was not accompanied by similar significant reduction in Cyclin E2 protein from similarly treated MCF-7 cells, due in part to a lag in the expression process that includes both transcriptional and post-transcriptional components as well as feedback or compensatory mechanisms following transcription. The only significant decrease observed in Cyclin E2 protein was seen in cells treated with raloxifene alone. The more immediate decrease in Cyclin E2 protein in cells treated only with raloxifene might reflect the transcription-independent character of the direct interaction of the ligand raloxifene with the estrogen receptor ERα, which initiates the effects of raloxifene [Wu et al., 2003; Tee et al., 2004; Cherlet and Murphy, 2007].

Although Cyclins E1 and E2 are remarkably similar in function, there are important differences in their post-transcriptional regulation, with a partially compensatory relationship between Cyclin E1 and Cyclin E2, specifically regulating levels of total E cyclins [Caldon and Musgrove, 2010; Caldon et al., 2013]. Cyclin E1 and E2 mRNA are targets of distinctly different microRNAs following transcription, and Cyclin E1 is also more effectively degraded in the early phases of the cell cycle, S phase in particular, by ubiquitin-mediated proteolysis, at least in cancer cells [Caldon and Musgrove, 2010; Caldon et al., 2013]. The exhibited decreases in Cyclin E2 protein and Cyclin E2 mRNA may be interpreted in light of our MTT results, which showed a reduction of viable MCF-7 cells following treatment with either raloxifene alone or raloxifene in combination with any tested PX-866 concentration but not following treatment with PX-866 alone. Cyclin E2 protein has previously been shown to be expressed at high levels in MCF-7 cells but not in MCF10A cells [Caldon et al., 2013]. Raloxifene and PX-866-induced changes in Cyclin E2 expression likely account for much of the difference between proliferation results in MCF-7 cells and in MCF10A cells.

An examination of the in-process database of the Human Interactome Project of the Center for Cancer Systems Biology (CCSB) of the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute and Harvard Medical School revealed a single protein–protein interaction involving IL-11, and that interaction involved Melanoma Antigen-A11 (MAGE-A11) [Rual et al., 2005]. Since the CCSB experiments identify but do not characterize interactions, we endeavored to determine whether that interaction, potentially regulated in part by raloxifene and PX-866 treatment, is important to regulation of cell proliferation.

Evidence has shown that MAGE-A11 (A) binds to p107, (B) removes the repressive E2F-4 and E2F-5 transcription factors from complex with p107, (C) recruits the androgen receptor (AR) to bind with p107 and modify ER-mediated regulation, (D) recruits E2F-1 into transient complex with p107 to effectively increase E2F-1-mediated transcription of its target genes which collectively induce transition to S phase of the cell cycle, and (E) converts p107 to an activator of cell cycle progression [Toth-Fejel et al., 2004; Minges et al., 2013; Su et al., 2013; Fioretti et al., 2014]. If the interaction between IL-11 and MAGE-A11 involves an effect by IL-11 upon MAGE-A11, then treatment with raloxifene and PX-866 should increase or decrease the MAGE-A11-mediated interference with p107 repressive activity.

Without more global reduction of E2F-1-mediated transcription, the reduced E2F-1 transcriptional activity did not appear to fully account for the reduced MCF-7 cell proliferation or the full extent of Cyclin E2 transcription decrease. We found that raloxifene and PX-866 in combination reduced the transcription level of IL-11 in MCF-7 cells, and CCSB discovered a protein–protein interaction between IL-11 and MAGE-A11, which impacts the repressive activity of TGF-β pathway component p107 [Su et al., 2013]. Effects, if any, of raloxifene and PX-866 on p107 phosphorylation, essential to most changes in the activity of E2F proteins regulated by p107 [Dyson, 1998; Leng et al., 2002], could profoundly impact TGF-β pathway activity, given that MAGE-A11 has been reported to alter the p107 binding partners, recruit AR, and convert p107 from a repressor to an activator of transcription [Su et al., 2013].

Although raloxifene in two combinations with PX-866 highly significantly reduced the level of p107 phosphorylated at Ser 975, PX-866 alone or in combinations with raloxifene reduced the level of total p107 protein. Since MAGE-A11 has also been reported to protect p107 protein from ubiquitin-mediated degradation [Su et al., 2013], a treatment-associated decrease in p107 protein, as we observed, would be consistent with a treatment-associated reduction of MAGE-A11-p107 interaction and with protection of the role of p107 in negative regulation of transcription and cell cycle progression.

Because of the similarity between p107 and Rb in structure and function, we extended the phosphorylation assessment to Rb and found that the treatment-associated reduction of phosphorylation was greater for Rb than for p107. The role of p107 in limiting S phase entry is mostly as a backup for Rb [Herrera et al., 1996; Hurford et al., 1997; Dyson, 1998]. Phosphorylated Rb protein was reduced significantly by all combinational treatments and by PX-866 alone. Total Rb protein, like total p107, was significantly reduced by three of the treatments but the reason, whether or not related to ubiquitin-mediated protein degradation, is a subject for future exploration. When the treatment effects on actual phosphorylation were evaluated, a significant reduction in Rb phosphorylation was indicated for all treatments with combination of raloxifene and PX-866.

Transcription of Cyclin E2, in particular, is regulated more by Rb than by p107. Cyclin E2 has been shown to be overexpressed in Rb double-knockout cells despite a compensatory increase in p107 expression [Herrera et al., 1996; Hurford et al., 1997]. While E2F-1, E2F-2, and E2F-3 are able to bind the activating site on the Cyclin E2 promoter, E2F-4 and E2F-5 are unable to bind [Sardet et al., 1995; Karlseder et al., 1996; Le Cam et al., 1999]. Since p107 preferentially binds E2F-4 or E2F-5, it is a poor substitute for Rb at the Cyclin E2 promoter unless its E2F binding partner is stably changed to E2F-1 [Sardet et al., 1995; Hurford et al., 1997; Dyson, 1998; Le Cam et al., 1999; Chen et al., 2002; Su et al., 2013].

Reduced E2F-1-mediated transcription and reduced proliferation resulted more from reduction of Rb phosphorylation than p107 phosphorylation, but the proliferation reduction was the result of reduced Cyclin E2 expression, which can also be achieved by mechanisms other than a decline in E2F-1 transcriptional activity. Down-regulation of Rb phosphorylation likely contributed a redundant effect on Cyclin E2 expression, while an additional contribution was likely provided by a decrease in Cyclin D1 expression and activity, which is essential to Cyclin E2 down-regulation [Caldon et al., 2009; Caldon and Musgrove, 2010]. Decreased Cyclin D1 expression has been demonstrated in glioblastoma cells as the result of treatment with PX-866 [Koul et al., 2010]. We will test for raloxifene and PX-866 effects on Cyclin D1 expression in MCF-7 cells. Raloxifene and PX-866 produced decreases in proliferation of MCF-7 breast cancer cells, likely through redundant mechanisms. While some important results followed treatments with raloxifene or PX-866 alone, highly significant reduction of MCF-7 cell proliferation, highly significant reduction of Cyclin E2 transcription and significant or highly significant reduction of Rb phosphorylation followed combinations of raloxifene and PX-866. The value of joint pathway modification was demonstrated.

Acknowledgments

Grant sponsor: NCI; Grant number: R01CA178441.

The authors wish to express appreciation to Rishabh Kala for valuable technical support. We also thank Dr. Centdrika Dates for critical reading of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: The authors have no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- Brehm A, Miska EA, McCance DJ, Reid JL, Bannister AJ, Kouzarides T. Retinoblastoma protein recruits histone deacetylase to repress transcription. Nature. 1998;391:597–601. doi: 10.1038/35404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caldon CE, Musgrove EA. Distinct and redundant functions of cyclin E1 and cyclin E2 in development and cancer. Cell Div. 2010;5:2. doi: 10.1186/1747-1028-5-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caldon CE, Sergio CM, Schutte J, Boersma MN, Sutherland RL, Carroll JS, Musgrove EA. Estrogen regulation of cyclin E2 requires cyclin D1 but not c-Myc. Mol Cell Biol. 2009;29:4623–4639. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00269-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caldon CE, Sergio CM, Sutherland RL, Musgrove EA. Differences in degradation lead to asynchronous expression of cyclin E2 in cancer cells. Cell Cycle. 2013;12:596–605. doi: 10.4161/cc.23409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen C-R, Kang Y, Siegel PM, Massague J. E2F4/5 and p107 as Smad cofactors linking the TGFb receptor to c-myc repression. Cell. 2002;110:19–32. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00801-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cherlet T, Murphy LC. Estrogen receptors inhibit Smad3 transcriptional activity through Ap-1 transcription factors. Mol Cell Biochem. 2007;306:33–42. doi: 10.1007/s11010-007-9551-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cobrinik D. Pocket proteins and cell cycle control. Oncogene. 2005;24:2796–2809. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dyson N. The regulation of E2F by pRB-family proteins. Genes Dev. 1998;12:2245–2262. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.15.2245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fioretti FM, Sita-Lumsden A, Bevan CL, Brooke GN. Revising the role of the androgen receptor in breast cancer. J Mol Endocrinol. 2014;52:R257–R265. doi: 10.1530/JME-14-0030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harbour JW, Luo RX, Dei Santi A, Postigo AA, Dean DC. Cdk phosphorylation triggers sequential intramolecular interactions that progressively block Rb functions as cells move through G1. Cell. 1999;98:859–869. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81519-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartman H, Fedorov A. The origin of the eukaryotic cell: A genomic investigation. PNAS. 2002;99:1420–1425. doi: 10.1073/pnas.032658599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrera RE, Sah VP, Williams BO, Makela TP, Weinberg RA, Jacks T. Altered cell cycle kinetics, gene expression and G1 restriction point regulation in Rb-deficient fibroblasts. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:2402–2407. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.5.2402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurford RK, Cobrinik D, Lee M-H, Dyson N. PRB and p107/p130 are required for the regulated expression of different sets of E2F responsive genes. Genes Dev. 1997;11:1447–1463. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.11.1447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ihle NT, Williams R, Chow S, Chew W, Berggren MI, Paine-Murrieta G, Minion DJ, Halter RJ, Wipf P, Abraham R, Kirkpatrick L, Powis G. Molecular pharmacology and antitumor activity of PX-866, a novel inhibitor of phosphoinositide-3-kinase signaling. Mol Cancer Ther. 2004;3:763–772. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson DG, Ohtani K, Nevins JR. Autoregulatory control of E2F1 expression in response to positive and negative cell cycle progression. Genes Dev. 1994;8:1514–1525. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.13.1514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karlseder J, Rotheneder H, Wintersberger E. Interaction of Sp1 with growth- and cell cycle-regulated transcription factor E2F. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:1659–1667. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.4.1659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleuser B, Malek D, Gust R, Pertz HH, Potteck H. 17-b-Estradiol inhibits transforming growth factor-b signaling and function in breast cancer cells via activation of extracellular signal-regulated kinase through the G protein-coupled receptor 30. Mol Pharmacol. 2008;74:1533–1543. doi: 10.1124/mol.108.046854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koul D, Shen R, Kim Y-W, Kondo Y, Lu Y, Bankson J, Ronen SM, Kirkpatrick DL, Powis G, Yung WKA. Cellular and in vivo activity of a novel PI3K inhibitor, PX-866, against human glioblastoma. Neuro Oncol. 2010;12:559–569. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/nop058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LeBlanc K, Sexton E, Parent S, Belanger G, Dery M-C, Boucher V, Asselin E. Effects of 4-hydroxytamoxifene, raloxifene and ICI 182780 on survival of uterine cancer cell lines in the presence and absence of exogenous estrogens. Int J Oncol. 2007;30:477–487. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Cam L, Polanowska J, Fabbrizio E, Oliver M, Philips A, Eaton EN, Classon M, Geng Y, Sardet C. Timing of cyclin E gene expression depends on the regulated association of a bipartite repressor element with a novel E2F complex. EMBO J. 1999;18:1878–1890. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.7.1878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JO, Russo AA, Pavletich NP. Structure of the retinoblastoma tumour-suppressor pocket domain bound to a peptide from HPV E7. Nature. 1998;391:859–865. doi: 10.1038/36038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leng X, Noble M, Adams PD, Qin J, Harper JW. Reversal of growth suppression by p107 via direct phosphorylation by cyclin D1/cyclin-dependent kinase 4. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22:2242–2254. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.7.2242-2254.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindquist DL, de Alarcon PA. Charcoal-dextran treatment of fetal bovine serum removes an inhibitor of human CFU-megakaryocytes. Exp Hematol. 1987;15:234–238. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livak K, Schmittgen T. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(−delta delta C(T)) method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meeran SM, Patel SN, Tollefsbol TO. Sulforaphane causes epigenetic repression of hTERT expression in human breast cancer cell lines. PLoS ONE. 2010;5:e11457. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minges JT, Su S, Grossman G, Blackwelder AJ, Pop EA, Mohler JL, Wilson EM. Melanoma antigen-A11 (MAGE-A11) enhances transcriptional activity by linking androgen receptor dimmers. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:1939–1952. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.428409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthuswamy SK, Li D, Lelievre S, Bissell MJ, Brugge JS. ErbB2, but not ErbB1, reinitiates proliferation and induces luminal repopulation in epithelial acini. Nat Cell Biol. 2001;3:785–792. doi: 10.1038/ncb0901-785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onnis B, Fer N, Rapisarda A, Perez VS, Melillo G. Autocrine production of IL-11 mediates tumorigenicity in cancer cells. J Clin Invest. 2013;123:1615–1629. doi: 10.1172/JCI59623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pulikkan JA, Dengler V, Peramangalam PS, Peer Zada AA, Muller-Tidow C, Bohlander SK, Tenen DG, Behre G. Cell-cycle regulator E2F1 and microRNA-223 comprise an autoregulatory negative feedback loop in acute myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2010;115:1768–1778. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-08-240101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qu Z, MacLellan WR, Weiss JN. Dynamics of the cell cycle: Checkpoints, sizers, and timers. Biophys J. 2003;85:3600–3611. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(03)74778-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rual J, Venkatesan K, Hao T, Hirozane-Kishawa T, Dricot A, Li N, Berriz GF, Gibbons FD, Dreze M, Ayivi-Guedehoussou N, Klitgord N, Simon C, Boxem M, Milstein S, Rosenberg J, Goldberg DS, Zhang LV, Wong SL, Franklin G, Li S, Albala JS, Lim J, Fraughton C, Llamosas E, Cevik S, Bex C, Lamesch P, Sikorski RS, Vandenhaute J, Zighbi HY, Smolyar A, Bosak S, Sequerra R, Doucette-Stamm L, Cusick ME, Hill DE, Roth FP, Vidal M. Towards a proteome-scale map of the human protein-protein interaction network. Nature. 2005;437:1173–1178. doi: 10.1038/nature04209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sardet C, Vidal M, Cobrinik D, Geng Y, Onufryk C, Chen Weinberg AA. E2F-4 and E2F-5, two members of the E2F family, are expressed in the early phases of the cell cycle. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:2403–2407. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.6.2403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasaki H, Hayakawa J, Terai Y, Kanemura M, Tanabe-Kimura A, Kamegai H, Seino-Noda H, Ezoe S, Matsumura I, Kanakura Y, Sakata M, Tasaka K, Ohmichi M. Difference between genomic actions of estrogen versus raloxifene in human ovarian cancer cell lines. Oncogene. 2008;27:2737–2745. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh M, Krajewski M, Mikolajka A, Holak TA. Molecular determinants for the complex formation between the retinoblastoma protein and LXCXE sequences. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:37868–37876. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M504877200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevens A, Hanson D, Whatmore A, Destenaves B, Chatelain P, Clayton P. Human growth is associated with distinct patterns of gene expression in evolutionarily conserved networks. BMC Genomics. 2013;14:547. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-14-547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su S, Minges JT, Grossman G, Blackwelder AJ, Mohler JL, Wilson EM. Proto-oncogene activity of melanoma antigen-A11 (MAGE-A11) regulated retinoblastoma-related p107 and E2F1 proteins. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:24809–24824. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.468579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tee MK, Rogatsky I, Tzagarakis-Foster C, Cvoro A, An J, Christy RJ, Yamamoto Leitman DC. Estradiol and selective estrogen receptor modulators differentially regulate target genes with estrogen receptors α and β. Mol Biol Cell. 2004;15:1262–1272. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E03-06-0360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Testa JR, Bellacosa A. AKT plays a central role in tumorigenesis. PNAS. 2001;98:10983–10985. doi: 10.1073/pnas.211430998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toth-Fejel S, Cheek J, Calhoun K, Muller P, Pommier RF. Estrogen and androgen receptors as comediators of breast cancer cell proliferation. Arch Surg. 2004;139:50–54. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.139.1.50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyson JJ, Novak B. Regulation of the eukaryotic cell cycle: Molecular antagonism, hysteresis, and irreversible transitions. J Theor Biol. 2001;210:249–263. doi: 10.1006/jtbi.2001.2293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang C, Hou X, Mohapatra S, Ma Y, Cress D, Pledger WJ, Chen J. Activation of p27Kip1 expression by E2F1. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:12339–12343. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C400536200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu L, Wu Y, Gathings B, Wan M, Li X, Grizzle W, Liu Z, Lu C, Mao Z, Cao X. Smad4 as a transcription corepressor for estrogen receptor α. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:15192–15200. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M212332200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Z, Cho H-J, Hampton GM, Theodorescu D. Cdc6 and Cyclin E2 are PTEN-regulated genes associated with human prostate cancer metastasis. Neoplasia. 2009;11:66–76. doi: 10.1593/neo.81048. 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan Z, DeGregori J, Shohet R, Leone G, Stillman B, Nevins JR, Williams RS. Cdc6 is regulated by E2F and is essential for DNA replication in mammalian cells. PNAS. 1998;95:3603–3608. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.7.3603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng X, Baker H, Hancock WS, Fawaz F, McCaman M, Pungor E. Proteomic analysis for the assessment of different lots of fetal bovine serum as a raw material for cell culture. Part IV. Application of proteomics to the manufacture of biological drugs. Biotech Prog. 2006;22:1294–1300. doi: 10.1021/bp060121o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]