Abstract

Background

In general, autosomal dominant inherited hearing loss does not have a founder mutation, with the causative mutation different in each family. For this reason, there has been a strong need for efficient diagnosis methods for autosomal dominant sensorineural hearing loss (ADSNHL) patients. This study sought to verify the effectiveness of our analysis algorithm for the screening of ADSNHL patients as well as the usefulness of the massively parallel DNA sequencing (MPS).

Subjects and Methods

Seventy-five Japanese ADSNHL patients from 53 ENT departments nationwide participated in this study. We conducted genetic analysis of 75 ADSNHL patients using the Invader assay, TaqMan genotyping assay and MPS-based genetic screening.

Results

A total of 46 (61.3%) ADSNHL patients were found to have at least one candidate gene variant.

Conclusion

We were able to achieve a high mutation detection rate through the combination of the Invader assay, TaqMan genotyping assay and MPS. MPS could be used to successfully identify mutations in rare deafness genes.

Introduction

Hearing loss is one of the most frequent congenital disorders in infants, with one out of every 500 newborns having bilateral hearing loss[1]. It is reported that 50–60% of these cases show a genetic etiology, with 80% of those with a genetic etiology demonstrating autosomal recessive hearing loss, and 20% of them showing autosomal dominant hearing loss[2]. However, as over 80 genes have been reported to be associated with hearing loss an efficient genetic screening system is required for nonsyndromic hearing loss. We have been working to popularize genetic analysis in Japan and have revealed the genetic background of Japanese hearing loss patients. Invader screening for 13 genes/46 mutations is currently used in Japanese, and is able to identify the responsible mutations in approximately 30–40% of deafness patients[3, 4], accelerating the clinical application of genetic screening. However, most of mutations targeted by the Invader assay are autosomal recessive genes (GJB2, SLC26A4, CDH23, etc.). However, diagnosis has been possible for only a few patients with an autosomal dominant inheritance pattern. The main features of autosomal dominant sensorineural hearing loss (ADSNHL) are that 1) the severity and/or progression varies in each family and 2) only a small number of founder mutations have been identified and there is remarkable diversity in the mutations found in each family. Accordingly, there is a strong need for the efficient diagnosis for ADSNHL families.

Thirty-two deafness-causative genes have reported to be associated with ADSNHL (Hereditary Hearing loss Homepage; http://hereditaryhearingloss.org/). However, the exons of all of these genes are too numerous for analysis using Sanger sequencing.

Recently, targeted exon sequencing of selected genes using massively parallel DNA sequencing (MPS) technology has provided us with a potential tool with which to systematically tackle previously intractable monogenic disorders and improve molecular diagnosis[5]. We also have recently reported that target exon sequencing using MPS is a powerful tool for the identification of rare gene mutations in deafness patients[6–8].

In this study, we conducted the genetic analysis of 75 ADSNHL patients using the Invader assay, TaqMan genotyping assay and MPS-based genetic screening. While the invader assay and TaqMan genotyping assay can effectively detect the variants frequently found in Japanese patients based on the large data set of the Japanese hearing loss patients[4], MPS can further analyze a large number of genes comprehensively. The purpose of this study is to confirm the effectiveness of our analysis algorithm for the screening of ADSNHL patients as well as the usefulness of MPS.

Subjects and Methods

Subjects

Seventy-five Japanese ADSNHL patients from 53 ENT departments nationwide participated in this study. We considered that a family that had hearing loss pedigrees in two or more generations to demonstrate autosomal dominant inheritance. Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects (or from their next of kin, caretaker, or guardian on the behalf of minors/children) prior to enrollment in the project. This study was approved by the ethical committees of Shinshu University and each of the other participating institutions listed as follows (Sapporo Medical University, Akita University, Iwate Medical University, Tohoku University, Tohoku Rosai Hospital, Yamagata University, Fukushima Medical University, Jichi Medical University, Gunma University, Jyuntendo University, Yokohama City University, Tokai University, Mejiro University, National Rehabilitation Center, Nihon University School, Saitama Medical University, Tokyo Medical University, Jikei University, Abe ENT clinic, Toranomon Hospital, Kitasato University, Tokyo Medical Center Institute of Sensory Organs, International University Health and Welfare Mita Hospital, Jichi University Saitama Medical Center, Aichi Children’s Health Medical Center, Chubu Rosai Hospital, Mie Hospital, Kyoto University, Kyoto Prefectural University, Mie University, Shiga Medical Center for Children, Shiga Medical University, Osaka University, Kansai Medical University, Kobe University, Osaka Medical Center and Research Institute for Maternal and Children Health, Hyogo College of Medicine, Kobe City Medical Center General Hospital, Wakayama Medical University, Kouchi University, Hiroshima University, Hiroshima City Hiroshima Citizen Hospital, Yamaguchi University, Ehime University, Kyushu University, Fukuoka University, Kurume University, Nagasaki University, Kanda ENT Clinic, Miyazaki Medical College, Kagoshima University, Ryukyus University).

Invader assay

We used the Invader assay for screening 46 known mutations in 13 known deafness genes (GJB2, SLC26A4, COCH, KCNQ4, MYO7A, TECTA, CRYM, POU3F4, EYA1, mitochondrial 12 s ribosomal RNA, mitochondrial tRNA(Leu), mitochondrial tRNA(Ser) and mitochondrial tRNA(Lys)). The detailed protocol was described elsewhere[4].

TaqMan genotyping assay

TaqMan genotyping assay for 55 known mutations in six deafness genes (SLC26A4, CDH23, KCNQ4, TECTA, OTOF, and WFS1) was applied for all subjects using a custom TaqMan SNP Genotyping Assay (Applied Biosystems, Life Technologies), TaqMan genotyping master mix (Applied Biosystems, Life Technologies) and a Stepone Plus real-time PCR system (Applied Biosystems, Life Technologies) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. [9]

MPS sequencing

Amplicon library preparation

Amplicon libraries were prepared using an Ion AmpliSeq™ Custom Panel (Applied Biosystems, Life Technologies) according to the manufacturer’s instructions for 63 genes reported to cause non-syndromic hearing loss. The detailed protocol was described elsewhere[10]. After preparation, the amplicon libraries were diluted to 20pM and equal amounts of 6 libraries for 6 patients were pooled for one sequence reaction.

Emulsion PCR and sequencing

Emulsion PCR and sequencing were performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The detailed protocol was described elsewhere[10]. MPS was performed with an Ion Torrent Personal Genome Machine (PGM) system using an Ion PGM™ 200 Sequencing Kit and an Ion 318™ Chip (Life Technologies).

Base call and data analysis

The sequence data were mapped against the human genome sequence (build GRCh37/hg19) with a Torrent Mapping Alignment Program. After sequence mapping, the DNA variant regions were piled up with Torrent Variant Caller plug-in software. After variant detection, their effects were analyzed using ANNOVAR software[11, 12]. The missense, nonsense, insertion/deletion and splicing variants were selected from among the identified variants. Variants were further selected as less than 1% of 1) the 1,000 genome database[13], 2) the 6,500 exome variants (http://evs.gs.washington.edu/EVS/), 3) the Human Genetic Variation Database (dataset for 1,208 Japanese exome variants)[14], 4) the 269 in-house Japanese normal hearing loss controls, and 5) 1000 control data in the deafness variation database[15].

To predict the pathogenicity of missense variants, we used 12 functional prediction software programs including ANNOVAR (SIFT, Polyphen2 HVID, Polyphen2 HVAR, LRT, Mutation Taster, Mutation Assessor, FATHMM, Radial SVM, LR, GERP++, PhyloP and SiPhy 29-way log odds).

Variant confirmation

All the variants found in this study were confirmed by Sanger sequencing using exon-specific custom primers, and segregation analysis was performed for the patients with pathogenic variants.

Results

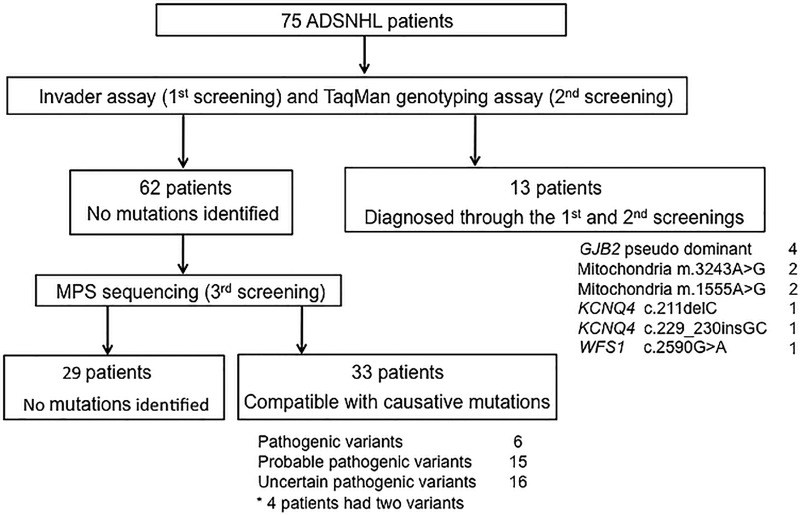

A total of 46 (61.3%) of the 75 ADSNHL patients were found to have at least one candidate variant (Fig 1). Thirteen patients (17.3%; 13/75) were diagnosed through the 1st and 2nd screenings (Invader assay and TaqMan genotyping assay). Among the 62 patients who were not diagnosed through the 1st and 2nd screenings, 33 (44.0%; 33/75) were found to have some candidate variants through the 3rd screening step (MPS).

Fig 1. The overview of our analysis algorithm using 3-step genetic analysis (Invader assay, TaqMan genotyping assay and MPS).

The 1st screening (Invader assay)

The mutations found by the 1st screening in this study are summarized in Table 1. Four patients (5.3%) had two GJB2 mutations, and they were thought to belong to a pseudo-dominant family. Two patients (2.7%) had m.3243A>G mutations and 2 patients (2.7%) had m.1555A>G mutations. The 1st screening was able to diagnose the responsible mutation in 8 (10.7%) of the 75 patients. Invader assay was thought to be useful for identifying pseudo-dominant and maternal inherited cases.

Table 1. The mutations found by the 1st and 2nd screenings in this study.

| Patients | Gene | Nucleotide Change1 | Nucleotide Change2 | Amino acid Change1 | Amino acid Change2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1st screening | |||||

| 1008 | GJB2 | c.235delC | c.[134G>A; 408C>A] | p.L79fs | p.[G45E; Y136X] |

| 794 | GJB2 | c.235delC | c.[134G>A; 408C>A] | p.L79fs | p.[G45E; Y136X] |

| 392 | GJB2 | c.427C>T | c.427C>T | p.R143W | p.R143W |

| 1005 | GJB2 | c.109G>A | c.109G>A | p.V37I | p.V37I |

| 505 | Mitochondria | m.3243A>G | — | — | — |

| 945 | Mitochondria | m.3243A>G | — | — | — |

| 508 | Mitochondria | m.1555A>G | — | — | — |

| 18 | Mitochondria | m.1555A>G | — | — | — |

| 2nd screening | |||||

| 982 | KCNQ4 | c.211delC | — | p.Q71fs | — |

| 38 | KCNQ4 | c.211delC | — | p.Q71fs | — |

| 780 | KCNQ4 | c.211delC | — | p.Q71fs | — |

| 485 | KCNQ4 | c.229_230insGC | — | p.H77fs | — |

| 416 | WFS1 | c.2590G>A | — | p.E864K | — |

The 2nd screening (TaqMan genotyping assay)

The mutations found by the 2nd screening in this study are summarized in Table 1. Four patients (5.3%) had KCNQ4 mutations (c.211delC and c.229_230insGC), and one patient (1.3%) had a WFS1 mutation (c.2590G>A, p.E864K). Thus, the 2nd screening was able to diagnose the responsible mutation in 5 (6.7%) of the 75 patients. TaqMan genotyping assay identified KCNQ4 mutations, which showed high GC contents.

The 3rd screening (MPS)

The 3rd screening was performed for the 62 patients who were not diagnosed through the 1st and 2nd screenings. The mutations found by MPS in this study are summarized in Table 2. The identified mutations were classified into pathogenic variants, probable pathogenic variants and uncertain pathogenic variants. A classification of pathogenic variant was based on the following criteria; 1) previously reported as a pathogenic variant, 2) not identified in controls and 3) judged to be a damaging mutation by functional prediction software. Probable pathogenic variants were classified on the following criteria; 1) not identified in controls, 2) judged to be damaging mutations by functional prediction software and/or 3) nonsense, frameshift insertions/deletions or splicing junctions. Mutations identified in controls and/or not judged to be damaging mutations by functional prediction software were classified as uncertain pathogenic variants. We regarded a mutation as a pathogenic variant when more than six out of 8 prediction programs judged it to be a damaging mutation.

Table 2. The mutations found by the 3rd screening in this study.

| Patients | Gene | Nucleotide Change | Amino acid Change | Control (chromosome) | Functional Prediction | Severity* | Type | References | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SIFT | PolyPhen2 | LRT | Mutation Taster | Mut Assesor | FATHMM | RadialSVM | LR | |||||||||

| Pathogenic variants | ||||||||||||||||

| 964 | ACTG1 | NM_001614 | c.353A>T | p.K118M | 0/538 | D(1) | B(0.40) | D(1) | A(1) | H(0.789) | D(0.54) | D(0/733) | D(0.932) | moderate | high | Zhu et al., 2003[30] |

| 858 | COCH | NM_004086 | c.1115T>C | p.I372T | 0/538 | D(1) | D(0.996) | D(1) | D(1) | M(0.727) | D(0.456) | D(0.621) | D(0.746) | moderate | high | Tsukada et al., 2015[28] |

| 962 | COCH | NM_004086 | c.1115T>C | p.I372T | 0/538 | D(1) | D(0.996) | D(1) | D(1) | M(0.727) | D(0.456) | D(0.621) | D(0.746) | severe | high | Tsukada et al., 2015[28] |

| 883 | COL11A2 | NM_080681 | c.3937_3948del12 | p.1312_1315del4 | 0/538 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | mild | flat | Iwasa et al., 2015[32] |

| 14 | MYO7A | NM_000260 | c.652G>A | p.D218N | 0/538 | D(0.99) | D(1) | D(1) | D(1) | M(0.736) | T(0.421) | D(0.558) | D0.61) | moderate | mid-high | Sun et al., 2011[29] |

| 555 | WFS1 | NM_006005 | c.2507A>C | p.K836T | 0/538 | T(0.38) | D(0.999) | D(1) | D(1) | L(0.566) | D(0.52) | DD(0.568) | D0.778) | mild | low | Fujikawa et al., 2010[27] |

| Probable pathogenic variants | ||||||||||||||||

| 1051 | CCDC50 | NM_178335 | c.820C>T | p.R274X | 0/538 | NA | NA | N(0.753) | A(1) | NA | NA | NA | NA | moderate | flat | This study |

| 1043 | DIAPH1 | NM_005219 | c.3637C>T | p.R1213X | 0/538 | T(0) | NA | D(1) | D(1) | NA | NA | NA | NA | severe | high | This study |

| 610 | DIAPH1 | NM_005219 | c.663G>C | p.L221F | 0/538 | D(1) | D(1) | D(1) | D(1) | M(0.679) | D(0.512) | D0.618) | D(0.827) | moderate | mid-high | This study |

| 963 | EYA4 | NM_004100 | c.1790delT | p.V597fs | 0/538 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | moderate | flat | This study |

| 954 | GRHL2 | NM_024915 | c.937dupC | p.E312fs | 0/538 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | moderate | flat | This study |

| 946 | KCNQ4 | NM_004700 | c.754G>C | p.A252P | 0/538 | D(1) | D(1) | D(1) | D(1) | M(0.75) | D(0.563) | D(0.523) | D(0.532) | moderate | mid-high | This study |

| 995 | KCNQ4 | NM_004700 | c.463G>A | p.G155R | 0/538 | D(1) | D(1) | D(1) | D(1) | L(0.60) | D(0.48) | T(0.30) | T(0.23) | moderate | high | This study |

| 87 | MYH14 | NM_001077 | c.823C>T | p.R275C | 0/538 | D(0.99) | D(1) | NA | D(1) | H(0.79) | T(0.423) | D(0.543) | D(0.595) | mild | mid | This study |

| 1020 | MYO6 | NM_004999 | c.897+2T>C | — | 0/538 | NA | NA | NA | D(1) | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | This study |

| 1021 | MYO6 | NM_004999 | c.1455T>A | p.N485K | 0/538 | D(1) | D(1) | N(1) | D(1) | H(0.877) | D(0.488) | D(0.587) | D(0.832) | moderate | flat | This study |

| 433 | MYO6 | NM_004999 | c.2287-2A>G | — | 0/538 | NA | NA | NA | D(1) | NA | NA | NA | NA | mild | mid | This study |

| 694 | MYO7A | NM_000260 | c.479C>G | p.S160C | 0/538 | D(1) | D(1) | D(1) | D(1) | H(0.881) | D(0.545) | D(0.713) | D(0.97) | NA | NA | This study |

| 673 | MYO7A | NM_000260 | c.1978G>A | p.G660R | 0/538 | D(1) | D(1) | D(1) | D(1) | H(0.882) | D(0.587) | D(0.696) | D(0.986) | mild | low | This study |

| 1080 | TECTA | NM_005422 | c.4302C>A | p.Y1434X | 0/538 | T(0) | NA | D(1) | A(1) | NA | NA | NA | NA | moderate | low-mid | This study |

| 963 | WFS1 | NM_006005 | c.1147C>T | p.R383C | 0/538 | D(0.97) | B(0.039) | D(1) | D(1) | L(0.612) | D(0.492) | D(0.481) | D(0.588) | moderate | flat | This study |

| Uncertain pathogenic variants | ||||||||||||||||

| 406 | COL11A2 | NM_080681 | c.106C>T | p.R36W | 0/538 | D(1) | D(1) | N(0.999) | N(1) | L(0.619) | T(0.235) | T(0.264) | T)0.007) | moderate | mid-high | This study |

| 981 | DIABLO | NM_004403 | c.92C>T | p.T31I | 0/538 | T(0.78) | D(1) | D(1) | D(1) | L(0.632) | T(0.436) | D(0.475) | D(0.585) | mild | flat | This study |

| 962 | GRHL2 | NM_024915 | c.1547G>A | p.R516Q | 1/538 | T(0.34) | B(0.037) | D(1) | D(1) | L(0.596) | T(0.293) | T(0.241) | T0.027) | severe | high | This study |

| 970 | GRHL2 | NM_024915 | c.1334A>G | p.Q445R | 1/538 | T(0.88) | B(0) | N(0.85) | N(0.711) | N(0.541) | T(0.294) | T(0.233) | T(0.022) | moderate | high | This study |

| 97 | MYH14 | NM_001077 | c.1990G>A | p.G664S | 0/538 | T(0.55) | P(0.796) | NA | D(0.976) | N(0.366) | T(0.421) | T(0.373) | T(0.228) | moderate | low-mid | This study |

| 500 | MYH14 | NM_001077 | c.1049G>A | p.R350Q | 1/538 | T(0.42) | B(0.136) | NA | D(0.793) | N(0.539) | D(0.479) | T(0.385) | T(0.388) | NA | NA | This study |

| 962 | MYH14 | NM_001077 | c.5324G>A | p.R1783H | 0/538 | D(1) | B(0.43) | NA | D(0.755) | M(0.708) | D(0.466) | D(0.534) | D(0.572) | severe | high | This study |

| 433 | MYO6 | NM_004999 | c.3497G>T | p.R1166L | 1/538 | T(0.89) | D(1) | D(1) | D(1) | L(0.633) | D(0.49) | D(0.584) | D(0.766) | mild | mid | This study |

| 426 | MYO7A | NM_000260 | c.3701C>G | p.T1234S | 1/538 | D(1) | P(0.911) | D(1) | D(1) | M(0.683) | T(0.434) | D(0.482) | T(0.473) | moderate | high | This study |

| 689 | MYO7A | NM_000260 | c.1868G>A | p.R623H | 0/538 | D(0.99) | D(1) | D(1) | D(1) | L(0.591) | T(0.42) | T(0.455) | T(0.44) | moderate | mid-high | This study |

| 694 | MYO7A | NM_000260 | c.2947G>T | p.D983Y | 0/538 | T(0.94) | P(0.523) | D(1) | D(1) | M(0.698) | D(0.48) | D(0.592) | D(0.731) | NA | NA | This study |

| 705 | MYO7A | NM_000260 | c.1436T>G | p.L479R | 0/538 | T(0.47) | B(0.292) | D(1) | D(1) | N(0.370) | T(0.413) | T(0.24) | T(0.088) | moderate | high | This study |

| 502 | TECTA | NM_005422 | c.842T>C | p.V281A | 0/538 | T(0.15) | B(0.02) | N(0.989) | N(0.998) | L(0.577) | T(0.403) | T(0.254) | T(0.134) | moderate | high | This study |

| 636 | TECTA | NM_005422 | c.5908G>A | p.A1970T | 0/538 | T(0.93) | B(0.056) | N(0.941) | N(0.999) | N(0.467) | D(0.457) | T(0.25) | T(0.262) | mild | mid-high | This study |

| 853 | TJP2 | NM_004817 | c.881G>A | p.S294N | 0/538 | NA | P(0.763) | D(1) | D(1) | M(0.681) | T(0.363) | T(0.275) | T(0.151) | moderate | mid | This study |

| 541 | WFS1 | NM_006005 | c.2359G>A | p.A787T | 0/538 | T(0.41) | B(0.003) | N(0.526) | N(1) | N(0.531) | D(0.514) | T(0.329) | T(0.485) | profound | flat | This study |

*average 500, 1000, 2000 and 4000Hz in the better hearing ear. 25–39:mild, 40–69:moderate, 70–89:severe, 90-: profound

A, disease causing automatic; B, benign; C, conserved; D, deleterious or probably damaging or disease causing; H, high; L, low; M, medium; N, neutral or polymorphism; NA, not applicable; P, possibly damaging; T, tolerated

Based on the above criteria, six mutations were classified as pathogenic variants in 5 genes (COL11A2, MYO7A, WFS1, ACTG1 and COCH), 15 were thought to be probable pathogenic variants in 11 genes (CCDC50, DIAPH1, EYA4, GRHL2, KCNQ4, MTH14, MYO6, MYO7A, TECTA and WFS1), and 16 were thought to be uncertain pathogenic variants in 8 genes (COL11A2, DIABLO, GRHL2, MYH14, MYO6, MYO7A, TECTA, TJP2 and WFS1).

The 3rd screening allowed at least one candidate mutation to be identified in 33 (44.0%; 33/75) of the 62 patients who were not diagnosed through the 1st or 2nd screenings.

Discussion

The results of this study confirmed that our analysis algorithm is an efficient diagnostic strategy for ADSNHL patients. Overall, the 3-step genetic analysis enabled the detection of mutations in 46 (61.3%) of 75 families. Previous studies have reported diagnostic rates of 40.0% (4/10)[16] and 57.1% (4/7)[17] using only MPS. In this study, the number of patients analyzed was much higher than those in past reports, and we believe that this is the first report in which the study population contains a large number of ADSNHL patients.

In this study, we analyzed mutations in GJB2 (for detecting pseudo-dominant cases), mitochondrial m.3243A>G, m.1555A>G (that were not analyzed by MPS) using the 1st screening step. As a result, we detected 4 pseudo-dominant families (5.3%) resulting from GJB2 mutations and 4 families (5.3%) with mitochondrial mutations. It is difficult to distinguish whether a family demonstrates dominant inheritance or not (pseudo-dominant and maternal inheritance) based only on family history, particularly in developed countries where families are usually small. It is, therefore, important to analyze autosomal recessive inheritance and maternal inheritance, even if the case appears to be autosomal dominant inheritance.

The 2nd screening step allowed us to analyze mutations in six genes frequently detected in Japanese hearing loss patients. As a result, we detected causative mutations in 5 patients. KCNQ4 mutations (c.211delC and c.229_230insGC) could not be detected by MPS because of technical limitations (extremely high GC contents), although this mutation was found frequently, as we previously reported[18]. We believe that the 2nd screening step was particularly useful for detecting KCNQ4 mutations.

The 3rd screening step using MPS identified many rare mutations in a number of genes (ACTG1, CCDC50, DIABLO, DIAPH1, EYA4, GRHL2, and TJP2). It has been thought that mutations in many different genes are associated with each ADSNHL family; therefore, it was difficult to identify the causative mutation from the many candidates using only classical methods (Sanger sequencing, etc.). MPS is considered to be an effective tool for screening ADSNHL mutations. Further study is required to confirm the true causative mutations, however, newly identified rare mutations should provide a good detection marker for further use.

In the 3rd screening step, 15 mutations were thought to be probable pathogenic variants. CCDC50: c.820C>T (p.R274X), DIAPH1: c.3637C>T (p.R1213X), EYA4: c.1790delT (p.V597fs), GRHL2: c.937dupC (p.E312fs), MYO6: c.2287-2A>G, MYO6: c.897+2T>C and TECTA: c.4302C>A (p.Y1434X) are truncating mutations; therefore, these mutations are speculated to show pathogenicity. In past reports, in particular, truncating mutations of CCDC50, DIAPH1, EYA4, GRHL2 and MYO6 genes were found to cause ADSNHL[19–24]. DIAPH1: c.663G>C (p.L221F), KCNQ4: c.754G>C (p.A252P), MYH14: c.823C>T (p.R275C), MYO7A: c.479C>G (p.S160C), MYO6: c.1455T>A (p.N485K), MYO7A: c.1978G>A (p.G660R) and WFS1: c.1147C>T (p.R383C) were judged to be damaging mutations by functional prediction programs and were not identified in controls. However, it was difficult to decide whether these mutations are the real cause of hearing loss as these mutations are missense mutations. Further study is needed to reach a definitive conclusion. KCNQ4: c.463G>A (p.G155R) did not meet the criteria for a probable pathogenic variant as only 5 out of the 8 prediction programs judged it to be pathogenic. However, the patient with this mutation showed ski slope hearing loss. In past reports, the patients with KCNQ4 mutations showed a similar type of hearing loss. Their phenotype supports the pathogenicity of this mutation; therefore, we categorized this mutation as a probable pathogenic variant.

Two KCNQ4 mutations were found through the 3rd screening step. Therefore, a total of 6 (8.0%) of the 75 patients were thought to have KCNQ4 mutations. KCNQ4 mutations are considered to be the most important causative mutation in Japanese ADSNHL patients, as we reported previously[18]. WFS1 and COCH gene mutations were also reported to be frequently identified causes of ADSNHL[25, 26]. In our study, 3 patients (4.0%) were identified with WFS1 mutations and 2 patients (2.7%) with COCH mutations. These frequencies are relatively high and are compatible with those from past reports. It is worthy of note that these mutations (WFS1: c.2507A>C (p.K836T), COCH: c.1115T>C (p.I372T)) are recurrent mutations in Japanese patients[27, 28]. Therefore, they may be related to a founder effect. MYO7A (4.0%), MYO6 (4.0%), and DIAPH1 (2.7%) were also detected frequently.

Some mutations (WFS1: c.2590G>A (p.E864K), MYO7A: c.652G>A (p.D218N) and ACTG1: c.353A>T (p.K118M)) were previously reported in different populations[25, 29–31]. Therefore, they may be hot spot mutations rather than founder mutations. Until now, it has been thought that ADSNHL has a different causative mutation in each family and that it is difficult to diagnose ADSNHL families efficiently. However, even in cases of ADSNHL, hot spot mutations and founder mutations are considered to contribute to the etiology to some extent.

In conclusion, MPS was able to successfully identify mutations in rare deafness genes. Moreover, we achieved a high mutation detection rate through a combination of the Invader assay, TaqMan genotyping assay and MPS. The use of MPS is expected to provide a much fuller understanding of the genetic background in cases of ADSNHL.

Acknowledgments

We thank all the families that participated in the present study. We would also like to thank S. Matsuda and F. Suzuki-Tomioka for their technical assistance.

Abbreviations

- ADSNHL

autosomal dominant sensorineural hearing loss

- MPS

massively parallel DNA sequencing

- ENT

ear nose throat

- SNP

single nucleotide polymorphism

- PCR

polymerase chain reaction

Data Availability

Data access is controlled by data access community of the Shinshu University. Data are available from the Shinshu University Institutional Data access / Ethics Committee for researchers who meet the criteria for access to confidential data. If you would like to request access to this data set, please contact Shin-ichi Usami, usami@shinshu-u.ac.jp.

Funding Statement

This study was grant aided by a Health, Labour and Welfare of Japan Scientific Research Grant (H25-Kankaku-Ippan-002), Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development (15dk0310011h0003), and a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (A) (15H02565) from the Ministry of Education, Science and Culture of Japan. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Morton CC, Nance WE. Newborn hearing screening—a silent revolution. N Engl J Med. 2006; 354(20):2151–2164. 10.1056/NEJMra050700 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Smith RJ, Bale JF Jr., White KR . Sensorineural hearing loss in children. Lancet 2005; 365(9462):879–890. 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)71047-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Abe S, Yamaguchi T, Usami S. Application of deafness diagnostic screening panel based on deafness mutation/gene database using invader assay. Genet Test 2007; 11(3):333–340. 10.1089/gte.2007.0002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Usami SI, Nishio SY, Nagano M, Abe S, Yamaguchi T. Simultaneous Screening of Multiple Mutations by Invader Assay Improves Molecular Diagnosis of Hereditary Hearing Loss: A Multicenter Study. PLoS One 2012; 7(2):e31276 10.1371/journal.pone.0031276 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shearer AE, DeLuca AP, Hildebrand MS, Taylor KR, Gurrola J 2nd, Scherer S, et al. Comprehensive genetic testing for hereditary hearing loss using massively parallel sequencing. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2010; 107(49):21104–21109. 10.1073/pnas.1012989107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Miyagawa M, Naito T, Nishio SY, Kamatani N, Usami S. Targeted exon sequencing successfully discovers rare causative genes and clarifies the molecular epidemiology of Japanese deafness patients. PLoS One 2013; 8(8):e71381 10.1371/journal.pone.0071381 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yoshimura H, Iwasaki S, Nishio SY, Kumakawa K, Tono T, Kobayashi Y, et al. Massively parallel DNA sequencing facilitates diagnosis of patients with Usher syndrome type 1. PLoS One 2014; 9(3):e90688 10.1371/journal.pone.0090688 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nishio SY, Usami S. Deafness gene variations in a 1120 nonsyndromic hearing loss cohort: molecular epidemiology and deafness mutation spectrum of patients in Japan. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 2015; 124 Suppl 1:49S–60S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nishio SY, Hayashi Y, Watanabe M, Usami S. Clinical application of a custom AmpliSeq library and ion torrent PGM sequencing to comprehensive mutation screening for deafness genes. Genet Test Mol Biomarkers 2015; 19(4):209–217. 10.1089/gtmb.2014.0252 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Miyagawa M, Nishio SY, Ikeda T, Fukushima K, Usami S. Massively parallel DNA sequencing successfully identifies new causative mutations in deafness genes in patients with cochlear implantation and EAS. PLoS One 2013; 8(10):e75793 10.1371/journal.pone.0075793 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang K, Li M, Hakonarson H. ANNOVAR: functional annotation of genetic variants from high-throughput sequencing data. Nucleic Acids Res 2010; 38(16):e164 10.1093/nar/gkq603 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chang X, Wang K. wANNOVAR: annotating genetic variants for personal genomes via the web. J Med Genet 2012; 49(7):433–436. 10.1136/jmedgenet-2012-100918 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Abecasis GR, Auton A, Brooks LD, DePristo MA, Durbin RM, Handsaker RE, et al. An integrated map of genetic variation from 1,092 human genomes. Nature 2012; 491(7422):56–65. 10.1038/nature11632 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Narahara M, Higasa K, Nakamura S, Tabara Y, Kawaguchi T, Ishii M, et al. Large-scale East-Asian eQTL mapping reveals novel candidate genes for LD mapping and the genomic landscape of transcriptional effects of sequence variants. PLoS One 2014; 9(6):e100924 10.1371/journal.pone.0100924 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shearer AE, Eppsteiner RW, Booth KT, Ephraim SS, Gurrola J 2nd, Simpson A, et al. Utilizing ethnic-specific differences in minor allele frequency to recategorize reported pathogenic deafness variants. Am J Hum Genet 2014; 95(4):445–453. 10.1016/j.ajhg.2014.09.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wu CC, Lin YH, Lu YC, Chen PJ, Yang WS, Hsu CJ, et al. Application of massively parallel sequencing to genetic diagnosis in multiplex families with idiopathic sensorineural hearing impairment. PLoS One 2013; 8(2):e57369 10.1371/journal.pone.0057369 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yang T, Wei X, Chai Y, Li L, Wu H. Genetic etiology study of the non-syndromic deafness in Chinese Hans by targeted next-generation sequencing. Orphanet J Rare Dis 2013; 8:85 10.1186/1750-1172-8-85 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Naito T, Nishio SY, Iwasa Y, Yano T, Kumakawa K, Abe S, et al. Comprehensive genetic screening of KCNQ4 in a large autosomal dominant nonsyndromic hearing loss cohort: genotype-phenotype correlations and a founder mutation. PLoS One 2013; 8(5):e63231 10.1371/journal.pone.0063231 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Modamio-Hoybjor S, Mencia A, Goodyear R, del Castillo I, Richardson G, Moreno F, et al. A mutation in CCDC50, a gene encoding an effector of epidermal growth factor-mediated cell signaling, causes progressive hearing loss. Am J Hum Genet 2007; 80(6):1076–1089. 10.1086/518311 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lynch ED, Lee MK, Morrow JE, Welcsh PL, Leon PE, King MC. Nonsyndromic deafness DFNA1 associated with mutation of a human homolog of the Drosophila gene diaphanous. Science 1997; 278(5341):1315–1318. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kim YR, Kim MA, Sagong B, Bae SH, Lee HJ, Kim HJ, et al. Evaluation of the contribution of the EYA4 and GRHL2 genes in Korean patients with autosomal dominant non-syndromic hearing loss. PLoS One 2015. 10(3):e0119443 10.1371/journal.pone.0119443 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Peters LM, Anderson DW, Griffith AJ, Grundfast KM, San Agustin TB, Madeo AC, et al. Mutation of a transcription factor, TFCP2L3, causes progressive autosomal dominant hearing loss, DFNA28. Hum Mol Genet 2002; 11(23):2877–2885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vona B, Nanda I, Neuner C, Muller T, Haaf T. Confirmation of GRHL2 as the gene for the DFNA28 locus. Am J Med Genet A 2013; 161A(8):2060–2065. 10.1002/ajmg.a.36017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sanggaard KM, Kjaer KW, Eiberg H, Nurnberg G, Nurnberg P, Hoffman K, et al. A novel nonsense mutation in MYO6 is associated with progressive nonsyndromic hearing loss in a Danish DFNA22 family. Am J Med Genet A 2008; 146A(8):1017–1025. 10.1002/ajmg.a.32174 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fukuoka H, Kanda Y, Ohta S, Usami S. Mutations in the WFS1 gene are a frequent cause of autosomal dominant nonsyndromic low-frequency hearing loss in Japanese. J Hum Genet 2007; 52(6):510–515. 10.1007/s10038-007-0144-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hilgert N, Smith RJ, Van Camp G. Forty-six genes causing nonsyndromic hearing impairment: which ones should be analyzed in DNA diagnostics? Mutat Res 2009; 681(2–3):189–196. 10.1016/j.mrrev.2008.08.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fujikawa T, Noguchi Y, Ito T, Takahashi M, Kitamura K. Additional heterozygous 2507A>C mutation of WFS1 in progressive hearing loss at lower frequencies. Laryngoscope 2010; 120(1):166–171. 10.1002/lary.20691 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tsukada K, Ichinose A, Miyagawa M, Mori K, Hattori M, Nishio SY, et al. Detailed hearing and vestibular profiles in the patients with COCH mutations. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 2015; 124 Suppl 1:100S–110S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sun Y, Chen J, Sun H, Cheng J, Li J, Lu Y, et al. Novel missense mutations in MYO7A underlying postlingual high- or low-frequency non-syndromic hearing impairment in two large families from China. J Hum Genet 2011; 56(1):64–70. 10.1038/jhg.2010.147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhu M, Yang T, Wei S, DeWan AT, Morell RJ, Elfenbein JL, et al. Mutations in the gamma-actin gene (ACTG1) are associated with dominant progressive deafness (DFNA20/26). Am J Hum Genet 2003; 73(5):1082–1091. 10.1086/379286 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Eiberg H, Hansen L, Kjer B, Hansen T, Pedersen O, Bille M, et al. Autosomal dominant optic atrophy associated with hearing impairment and impaired glucose regulation caused by a missense mutation in the WFS1 gene. J Med Genet 2006; 43(5):435–440. 10.1136/jmg.2005.034892 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Iwasa Y, Moteki H, Hattori M, Sato R, Nishio SY, Takumi Y, et al. Non-ocular Stickler syndrome with a novel mutation in COL11A2 diagnosed by massively parallel sequencing in Japanese hearing loss patients. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 2015; 124 Suppl 1:111S–117S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data access is controlled by data access community of the Shinshu University. Data are available from the Shinshu University Institutional Data access / Ethics Committee for researchers who meet the criteria for access to confidential data. If you would like to request access to this data set, please contact Shin-ichi Usami, usami@shinshu-u.ac.jp.