Abstract

Background

The purpose of this study was to describe the experience of the Center of Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER) with expanded access of investigational drugs.

Methods

Multiple searches of CDER’s document tracking system were performed to identify the number, type, and indication for all expanded access requests over the 10-year time period of January 2005 through December 2014. An additional search was performed to identify all active commercial investigational drug development programs during that time period and whether or not the clinical program was placed on hold. The two searches were then cross-referenced to identify those commercial investigational drug development programs placed on clinical hold due to serious adverse events occurring within expanded access programs.

Results

CDER receives over 1000 applications for expanded access each year. The majority are for single patients, roughly evenly split between emergency and nonemergency use. The vast majority, 99.7%, are allowed to proceed. The incidence of clinical holds for all commercial investigational drug development programs is 7.9%, as compared to only 0.2% related to adverse events observed in patients receiving drug treatments under expanded access.

Conclusions

The expanded access program is viewed as a success from FDA’s perspective based on the large number of applications processed and allowed to proceed each year. However, the actual number of patients and their health care providers that desire drug treatments available under expanded access is not known. It is exceedingly rare for a serious adverse event under expanded access to affect the development program for that drug.

Keywords: expanded access, compassionate use, US Food and Drug Administration

Introduction

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has a long history of facilitating access to investigational drugs for the treatment of patients with serious or immediately life-threatening diseases or conditions that lack therapeutic alternatives. Expanded access, also referred to as “compassionate use,” is the use of an investigational drug product outside the context of a clinical trial or study. Under the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act (FDCA), FDA may authorize expanded access to an investigational product for the purpose of diagnosing, monitoring, or treating a serious or immediately life-threatening disease if (1) there is no comparable or satisfactory alternative treatment available; (2) the potential benefit justifies the potential risks of the treatment use and those potential risks are not unreasonable in the context of the disease or condition; (3) expanded access will not interfere with the initiation, conduct, or completion of clinical investigations that could support marketing approval or otherwise compromise the potential development of the expanded access use; and (4) an expanded access submission (investigational new drug [IND] application or new protocol to an existing active IND) for a specific use is made (21 CFR 312 subpart I).

Whenever possible, participation in a clinical trial is the preferred mechanism for providing patients access to an investigational drug, because clinical trials can generate the data that may support the approval of the drug and, consequently, result in greater availability of the drug. Not all patients have access to clinical trials. This may be due to the patient not meeting eligibility criteria or living too distant from study sites. In some cases, there may not be any ongoing trials. These patients may be able to receive investigational drugs, when appropriate, through expanded access. Health care providers can apply to the FDA to treat their patients with an investigational drug by submitting an IND application. There are 3 types of expanded access IND applications that can be submitted, depending on the size of the intended treatment population: (1) single patient, emergency or nonemergency use; (2) intermediate-size patient population; and (3) large patient population under a treatment IND. Alternatively, expanded access may be obtained through the submission of an expanded access protocol to an existing IND application, either by a commercial or research sponsor.

For physicians seeking expanded access to an investigational drug for their patient(s), an important component of the expanded access application is a letter of authorization (LOA) from the commercial developer of the investigational drug. The LOA grants FDA the right to reference the commercial developer’s application for information to satisfy submission requirements, such as a description of the manufacturing facility, chemistry, manufacturing and controls information, and pharmacology and toxicology information. But most importantly, the commercial developer must agree to provide the investigational drug for use in the expanded access program. There are many legitimate reasons why a commercial developer may elect to limit or deny expanded access to their investigational drug, including limitations in investigational drug supplies, diversion of eligible patients away from clinical trials, and lack of a favorable risk-benefit profile in specific patient populations. A common but unsubstantiated perception is that expanded access could place a drug development program at jeopardy following the occurrence of adverse events. It is assumed that patients who do not meet the entry criteria for clinical trials, but are treated on expanded access protocols, might be at increased risk for serious adverse events because of their advanced disease and/or comorbidities. The major concern is that these events, once reported to the FDA, could lead to clinical holds of the ongoing clinical trials and/or complicate the determination of the safety profile of a drug on FDA review of a marketing application. This perception remains despite the fact that the expedited adverse event safety reporting regulation (21 CFR 312.32) only requires reporting of those events that are serious, unexpected, and suspected to be related to the study drug.

There has been considerable controversy of late in the ethics, legality, and politics of expanded access.1–6 The purpose of this study was to describe the experience of the Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER) with expanded access to investigational drugs and to examine the hypothesis that expanded access poses a significant risk to a drug developer’s program.

Materials and Methods

We performed multiple searches of CDER’s document archiving, reporting, and regulatory tracking system (DARRTS) over the 10-year time period of January 2005 through December 2014. DARRTS is the informatics system that CDER uses to track all of the activities related to the applications, reports, meetings, and documents submitted to the FDA for medical products regulated by CDER. Queries were performed on FDA’s tracking databases to identify all new expanded access INDs, the type of expanded access IND, drug requested, indication and responsible review Division. In addition, active INDs with a submission of a new expanded access protocol during the time period were identified. A second query identified all active commercial INDs during that same time period. The third query was run to identify all of the INDs previously submitted by commercial sponsors (ie, “commercial INDs”) that were referenced by a new expanded access IND. A final query identified all of the INDs that were placed on clinical hold and the time from submission when that hold was placed. The clinical hold query was compared with the reference commercial IND query to identify those commercial INDs placed on clinical hold due to serious adverse events occurring on treatment under an expanded access IND.

A formal statistical analysis plan for these queries was not prespecified, therefore, only descriptive statistics were performed.

Results

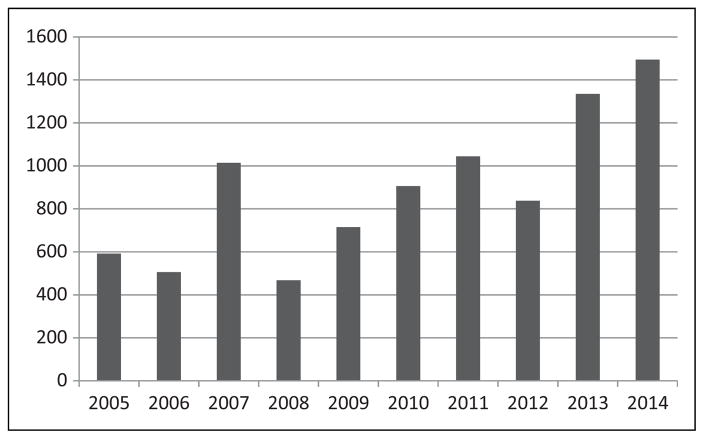

During the 10-year time period from 2005 through 2014 there were 10 939 new expanded access IND applications submitted to CDER. The number of expanded access requests has gone up significantly over the time period observed. The number of IND applications received in 2014 was more than double the number received in 2005 (Figure 1). These expanded access INDs referenced 1033 active commercial INDs. In addition, there were 665 expanded access protocols submitted to active commercial INDs during this same time period.

Figure 1.

The number of new expanded access IND requests to CDER by year of receipt. IND, investigational new drug.

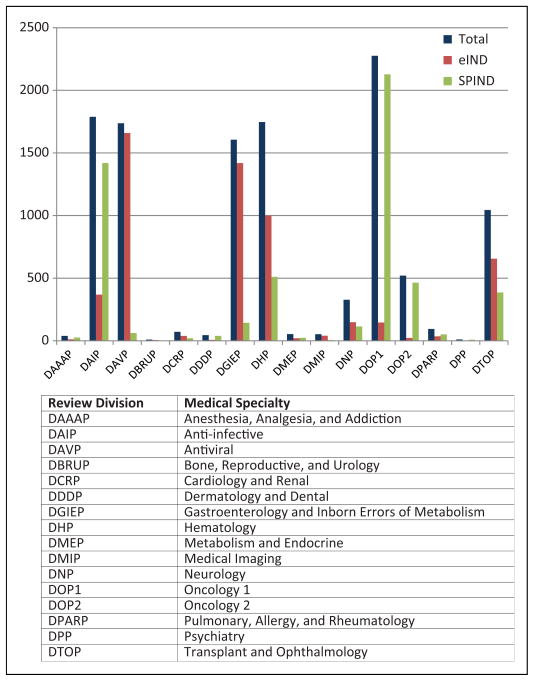

The vast majority of the expanded access INDs were for single patient use and these were split almost evenly between emergency and nonemergency (Table 1). The requests for access INDs are concentrated in review divisions that oversee antiviral and anti-infective products, transplant and ophthalmology products, hematology and oncology products, and products intended to treat gastroenterology disorders and inborn errors of metabolism (Figure 2). This is expected since these therapeutic areas are the ones where products are being developed to treat life-threatening illness with significant unmet medical need. The pattern of emergency versus none-mergency IND submissions was not anticipated. The vast majority of emergency IND (eIND) requests involved antiviral products, transplant and ophthalmology products, hematology products, and products intended to treat gastroenterology disorders and inborn errors of metabolism. In contrast, the majority of INDs involving anti-infective and oncology products were nonemergency submissions. We did not observe any trends over time for the types of access INDs or their indications.

Table 1.

Distribution of Expanded Access IND Types Submitted to CDER From 2005 Through 2014.

| Type of IND | Number |

|---|---|

| Single-patient IND, nonemergency (SPIND) | 5284 |

| Single-patient IND, emergency (eIND) | 5511 |

| Intermediate-size IND | 116 |

| Large population treatment IND | 28 |

| Total | 10 939 |

Figure 2.

The distribution of single-patient INDs, both emergency (eIND) and nonemergency (SPIND), across the review divisions in the Office of New Drugs within CDER. The totals shown represents the addition of both emergency and nonemergency INDs. IND, investigational new drug.

Almost all (99.7%) of the submitted expanded access INDs and protocols were allowed to proceed, some however after modification to the protocol (ie, to enhance safety monitoring or modify dosing). The number of uniquely named investigational drug entities for which expanded access INDs were requested is 1735; however, this number overestimates the total since the names of investigational drugs can change, sometimes only slightly, during development. There were 6581 indications listed for the expanded access INDs. This number is also an overestimate because of the varying names for the same indications (eg, mast cell disease vs mastocytosis; pancreatic cancer vs pancreas cancer, etc) and lumping or splitting of indications (eg, sarcoma vs liposarcoma). The most frequently requested indications were for hematologic malignancies, influenza, solid organ malignancies, irritable bowel syndrome, veno-occlusive disease, toxoplasmosis, hepatitis C, and Fabry disease.

During this same 10-year time period there were 10 482 active commercial INDs by 3242 commercial sponsors studying an estimated 9525 investigational drugs. The incidence of full and partial clinical holds for these commercial INDs was 1494, of which only 831 were beyond the initial 30-day safety review window. INDs undergo an initial safety review before they can proceed. Therefore, new INDs can only be placed on clinical hold because of serious adverse events after the trial has started which is after this initial review. The incidence of clinical holds, full or partial, for commercial INDs beyond the initial 30-day safety review window is relevant to this study and was 7.9%. There were only 2 instances identified in which a serious adverse event that occurred on treatment under an expanded access IND led to a clinical hold of the referenced commercial IND, for an incidence of 2 of 1033 (0.2%) referenced commercial INDs. Both instances involved the death of a cancer patient shortly after infusion of the investigational drug. In the first instance, a development program had multiple INDs placed on clinical hold and the hold actions were removed 2 months later, following submission of additional safety data and revision of the protocols to mitigate the risks identified. In the second instance, a partial clinical hold was placed on a commercial IND to limit the enrollment of new patients who were part of a specific vulnerable population and the clinical hold was removed 20 months later. Both drug development programs are still active.

Discussion

CDER receives more than 1000 requests for expanded access to investigational drugs each year. Temporal trends of the recent 10-year period demonstrate a significant increase in the number of request submitted each year. The vast majority are new single-patient INDs; however, INDs involving intermediate-size and large patient populations in treatment INDs may allow for the treatment of large numbers of patients within a single application.

Many parties participate in the expanded access process, including patients and their families, health care providers, institutional review boards, drug developers, and the FDA. There is a competing interest between an individual patient’s desire to gain access to an alternative therapy that is not currently marketed and the societal benefit of an efficient drug development process. The company developing the drug, being at the nexus of the process, has the tremendously difficult task of making the decision whether or not to provide access to the drug. CDER is able to track the number of times companies grant cross-reference to their drug (receives an LOA) but FDA is not aware of the number of requests received by companies. Based on the 99.7% rate of CDER allowing expanded access INDs to proceed, we can conclude that FDA is not an impediment to expanded access for those applicants that understand the process.

Nevertheless, there are many legitimate reasons for companies to deny access to their investigational drug. It is not uncommon for trials to fail as a result of lack of accrual, and given the opportunity, patients may prefer expanded access to trial participation especially when there is a chance of being randomized to placebo or standard of care. Drug companies often delay ramping up commercial drug production until late in development for practical reasons and the supply of investigational drug product can be quite limited. Diverting drug product to expanded access programs may interfere with the conduct of the requisite trials. This was highlighted in a recent article describing the ethical challenges faced by one company and how they dealt with it when providing expanded access for a drug being developed for multiple myeloma.7 In addition, there is a perception that expanded access might pose a risk to the development of a drug. The results of this study demonstrate that serious adverse events occurring on treatments available in expanded access programs do not significantly jeopardize drug development programs and that this fear is not a good reason to deny patients expanded access to an investigational drug.

A clinical hold is issued by FDA to delay the start of a proposed clinical trial or to suspend an ongoing trial(s). A clinical trial may be placed on hold because (1) subjects are or would be exposed to an unreasonable and significant risk, (2) the IND does not contain sufficient information required to assess risk to subjects, (3) clinical investigators are not qualified, or (4) the investigator’s brochure is misleading, erroneous, or materially incomplete (21 CFR 312.42(b)(1)). Additional grounds exist for placing a Phase 2/3 trial on hold, such as the plan or protocol is clearly deficient in its design to meet its stated objectives (21 CFR 312.42(b)(2)). This study found that roughly one half of all the clinical holds were placed during the 30-day safety review. These clinical holds are usually based on issues arising from nonclinical studies and/or concerns regarding the planned dosing or monitoring. In contrast, ongoing INDs are at risk for being placed on hold because of new safety signals arising from serious adverse events occurring in ongoing clinical trials. Oftentimes, these new risks can be mitigated through changes in the protocol (ie, entry criteria, monitoring, etc) and changes to the informed consent, thus avoiding a clinical hold.

New safety signals for an investigational drug are identified through expedited adverse event reporting and the routine assessment of cumulative adverse events. FDA expects the sponsor of an IND, commercial or research, to make a determination, independent of the investigator, as to whether or not a serious adverse event or death is causally related to the investigational drug before submitting an expedited report. This does not mean ruling out all possibility that it is related. Patients with significant comorbidities or advanced stages of a terminal disease are likely to experience serious adverse events, but these are usually anticipated and therefore a single event is unlikely to be interpretable. In this analysis of almost 11 000 expanded access INDs, an unexpected death temporally associated with investigational drug administration prompted interruption of 2 clinical development programs but only for a short time. The rarity of these events would not appear to support a general policy of denying large numbers of patients access to investigational drugs under expanded access programs. Even in the rare instances when a drug development program was interrupted, inclusion of additional safe guards ultimately allowed drug development to proceed.

Patients with serious and/or life-threatening illnesses, who have no available therapies or have failed all available therapies, sometimes with the assistance of their health care providers, will lobby for access to investigational drugs. Companies are developing new processes to deal with the increasing demand for expanded access.7 Many companies, however, may not be prepared to deal with all of the ethical and moral dilemmas posed by the competing interests of individual patients and society. Nevertheless, this burden is likely to increase with increasing awareness of this opportunity. FDA encourages companies to provide expanded access to promising drugs following completion of clinical trials in order to bridge the gap of marketing application preparation and review. Moreover, there is a public desire that companies have a public and transparent process regarding how they deal with expanded access requests. While there are often little data about the effectiveness of the drugs available under expanded access programs, in unique circumstances, expanded access has either bolstered, or been the sole source of, the safety and effectiveness data available for certain drugs that treat very rare diseases.

From FDA’s perspective, the expanded access program is viewed as successful based on both the volume of requests handled each year and the extremely high rate of approval of these requests. Nevertheless, FDA is not aware of the entire demand for investigational drugs under expanded access programs, since we only know about those requests that we receive, and based on the number of “right to try laws” passed in state legislatures, there appears to be a desire for improvement.4,6,8–10 FDA is currently in the process of streamlining the application process; however, more needs to be done to facilitate the interactions between patients, health care providers, and sponsors.

Conclusions

More than 1000 requests for expanded access to investigational drugs are submitted to CDER every year. The vast majority, 99.7%, are allowed to proceed. The majority of these requests are for single patients, evenly split between emergency and nonemergency use. The actual number of patients and their health care providers that desire expanded access to investigational drugs is not known since a letter of authorization by the commercial sponsor of the investigational drug is a requirement for submission of the expanded access application to FDA. It is exceedingly rare for a serious adverse event occurring during treatment under expanded access to affect the drug’s development program.

Acknowledgments

Funding

No financial support of the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article was declared.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

No potential conflicts were declared.

References

- 1.Rosenblatt M, Kuhlik B. Principles and challenges in access to experimental medicines. JAMA. 2015;313:2023–2024. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.4135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Caplan A. Medical ethicist Arthur Caplan explains why he opposes “right-to-try” laws. Oncology (Williston Park) 2016;30:8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Caplan AL, Bateman-House A. Should patients in need be given access to experimental drugs? Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2015;16:1275–1279. doi: 10.1517/14656566.2015.1046837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bateman-House A, Kimberly L, Redman B, Dubler N, Caplan A. Right-to-try laws: hope, hype, and unintended consequences. Ann Intern Med. 2015;163:796–797. doi: 10.7326/M15-0148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tsakopoulos A, Han J, Nodler H, Russo V. The right to try: an overview of efforts to obtain expedited access to unapproved treatment for the terminally ill. Food Drug Law J. 2015;70:617–641. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zettler PJ, Greely HT. The strange allure of state “right-to-try” laws. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174:1885–1886. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.5767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Caplan AL, Ray A. The ethical challenges of compassionate use. JAMA. 2016;315:979–980. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.0416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jacob JA. Questions of safety and fairness raised as right-to-try movement gains steam. JAMA. 2015;314:758–760. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.7691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Servick K. Patient advocacy. “Right to try” laws bypass FDA for last-ditch treatments. Science. 2014;344:1329. doi: 10.1126/science.344.6190.1329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yang YT, Chen B, Bennett C. “Right-to-try” legislation: progress or peril? J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:2597–2599. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.62.8057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]