Supraventricular tachycardias (SVTs) are common. Although Canadian epidemiologic data are lacking, evidence from the United States suggests that they account for about 50 000 emergency department visits annually.1 Atrial flutter has an overall incidence of 88 per 100 000 person-years, with an increasing incidence in older people, men and people with heart failure or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.2 In the US, the prevalence of paroxysmal SVT in the general population is 2.25 per 1000 population and the incidence 35 per 100 000 person-years.3

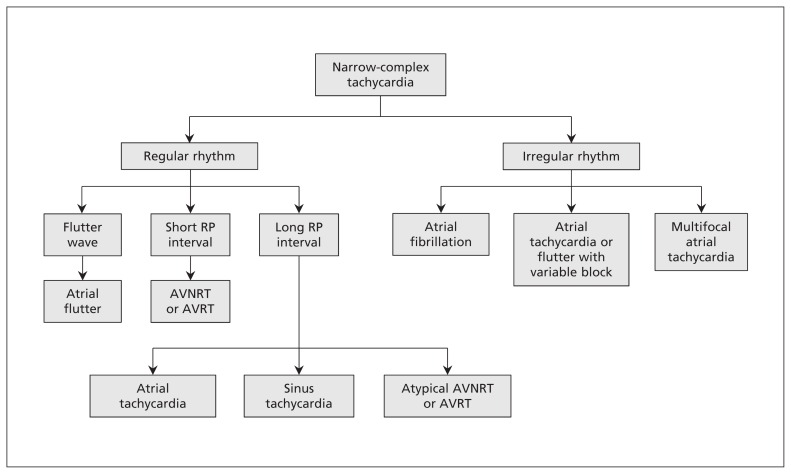

Supraventricular tachycardias represent a range of tachyarrhythmias (Figure 1) originating from a circuit or focus involving the atria or the atrioventricular node.4 The term paroxysmal SVT denotes a subset of SVTs that present as a clinical syndrome of rapid regular tachycardia with an abrupt onset and termination. Supraventricular tachycardias are usually narrow-complex tachycardias with a QRS interval of 100 ms or less on an electrocardiogram (ECG). Occasionally, they may show a wide QRS complex in the case of a pre-existing conduction delay, an aberrancy due to rate-related conduction delay or a bundle branch block. Rapid recognition of the underlying rhythm is essential to correct management in the acute setting, including identifying patients who may benefit from definitive treatment with catheter ablation.5

Figure 1:

A simplified approach to the diagnosis of narrow-complex tachycardias on electrocardiogram. AVNRT = atrioventricular nodal re-entrant tachycardia, AVRT = atrioventricular re-entrant tachycardia.

We reviewed randomized controlled trials, review articles and clinical practice guidelines to present a practical approach to the diagnosis and management of SVTs (Box 1). We focus on the most common forms of regular SVT, specifically atrioventricular nodal re-entrant tachycardia (AVNRT), atrioventricular re-entrant tachycardia (AVRT), atrial tachycardia and atrial flutter (Table 1). We have not included atrial fibrillation in this review. Although it is an arrhythmia that originates in the atria (and the pulmonary veins), the mechanism for this irregular tachycardia differs from the others we discuss.

Box 1: Evidence used in this review.

We conducted a literature search of PubMed using the following terms: “supraventricular tachycardia,” “atrial tachycardia,” “atrial flutter,” “atrioventricular nodal reentry tachycardia” and “atrioventricular reentry tachycardia” combined with “management or treatment or ablation.” “Atrial fibrillation” was used as an exclusive term. We included English- and French-language reports of studies involving human adults. (Further details about the search terms are in Appendix 1, available at www.cmaj.ca/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1503/cmaj.160079/-/DC1) We included randomized controlled trials, review articles and clinical practice guidelines, including the 2015 American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association/Heart Rhythm Society guideline on the management of adults with supraventricular tachycardia. We also manually retrieved articles from the reference lists of relevant articles.

Table 1:

| Type of SVT | Mechanism | Heart rate, beats/min | Rhythm | ECG findings | Rate of termination with adenosine | Use of anticoagulation | Response to catheter ablation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AVNRT | AV re-entry involving 2 functional pathways in the AV node | 150–250 | Regular | Retrograde P wave after QRS complex | 78%–96% | No | Acute success rate 96%–97%; recurrence rate 5% |

| AVRT | Re-entry involving AV node and accessory pathway | 150–250 | Regular | Retrograde P wave after QRS complex | 78%–96% | No | Acute success rate 93%; recurrence rate 8% |

| Atrial tachycardia | Ectopic atrial focus with enhanced automaticity | 150–250 | Regular or irregular (if variable AV block) | Ectopic P wave before QRS complex | Unlikely to terminate; may unmask underlying rhythm | No | Acute success rate 80%–100%; recurrence rate 4%–27% |

| Atrial flutter | Macro–re-entrant circuit (typically in the right atrium) | 150 | Regular or irregular (if variable AV block) | Atrial flutter wave with 2:1 conduction block or variable conduction block | Unlikely to terminate; may unmask underlying rhythm | Yes if age ≥ 65 yr or CHADS2 score ≥ 1 (CCS guideline35) | Typical: acute success rate 97%; recurrence rate 10% Atypical: acute success rate 73%–100%; recurrence rate 7%–53% |

Note: AV = atrioventricular, AVNRT = atrioventricular nodal re-entrant tachycardia, AVRT = atrioventricular re-entrant tachycardia, CCS = Canadian Cardiovascular Society, CHADS2 score = score counts 1 point for history of congestive heart failure, hypertension, age ≥ 75 years or diabetes mellitus, and 2 points for previous stroke or transient ischemic attack, ECG = electrocardiogram.

Typical features are summarized for each arrhythmia; however, different heart rates and atrioventricular conduction patterns are possible. The information in this table stems from multiple observational studies and registries.

Recommendations in this review are based on the 2015 guideline of the American College of Cardiology, the American Heart Association and the Heart Rhythm Society on the management of adults with supraventricular tachycardia (Box 2).5

Box 2: Summary of recommendations from the 2015 guideline of the American College of Cardiology, the American Heart Association and the Heart Rhythm Society on the management of adults with supraventricular tachycardia (SVT)*5.

Acute treatment

Vagal manoeuvres are recommended for acute treatment in patients with regular SVT (class I recommendation, level B-R evidence)

Intravenous administration of adenosine is recommended for acute treatment in patients with regular SVT (class I recommendation, level B-R evidence)

Synchronized cardioversion is recommended for acute treatment in patients with hemodynamically stable SVT when pharmacologic treatment is ineffective or contraindicated (class I recommendation, level B-NR evidence)

Intravenous administration of diltiazem or verapamil can be effective for acute treatment in patients with hemodynamically stable SVT (class IIa recommendation, level B-R evidence)

Intravenous use of β-blockers is reasonable for acute treatment in patients with hemodynamically stable SVT (class IIa recommendation, level C-LD evidence)

Ongoing management

Oral β-blocker, diltiazem or verapamil treatment is useful for ongoing management in patients with symptomatic SVT who do not have ventricular pre-excitation during sinus rhythm (class I recommendation, level B-R evidence)

Electrophysiologic study with the option of radiofrequency catheter ablation is useful for the diagnosis and potential treatment of SVT (class I recommendation, level B-NR evidence)

Patients with SVT should be educated on how to perform vagal manoeuvres for ongoing management of SVT (class I recommendation, level C-LD evidence)

Referral for radiofrequency catheter ablation

Catheter ablation of the slow pathway is recommended in patients with AVNRT (class I recommendation, level B-NR evidence)

Catheter ablation is recommended in patients with symptomatic focal atrial tachycardia as an alternative to pharmacologic treatment (class I recommendation, level B-NR evidence)

Catheter ablation of the accessory pathway is recommended in patients with AVRT or pre-excited atrial fibrillation (class I recommendation, level B-NR evidence)

An electrophysiologic study is reasonable in asymptomatic patients with pre-excitation to stratify risk for arrhythmic events (class IIa recommendation, level B-NR evidence)

Catheter ablation of the cavotricuspid isthmus is useful in patients with atrial flutter that is either symptomatic or refractory to pharmacologic rate control (class I recommendation, level B-R evidence)

Note: AVNRT = atrioventricular nodal re-entrant tachycardia, AVRT = atrioventricular re-entrant tachycardia.

Class I = strong recommendation where benefits >>> risks; class IIa = moderate-strength recommendation where benefits >> risks. Level B-R = moderate-quality evidence from one or more randomized controlled trials (RCTs) or meta-analyses of moderate-quality RCTs; level B-NR = moderate-quality evidence from one or more nonrandomized or observational or registry studies; level C-LD = limited data from RCTs or nonrandomized observational or registry studies with limitations of design or execution.

Who gets SVT?

In a single-centre retrospective study involving 1754 consecutive patients undergoing catheter ablation for paroxysmal SVT, the most common mechanism was AVRT in men, whereas AVNRT and atrial tachycardia were more common in women.6 In both sexes, the proportion of patients with AVRT decreased with age, and the proportion with AVNRT or atrial tachycardia increased. Overall, the most common mechanism in this cohort was AVNRT followed by AVRT and atrial tachycardia.

What are the different mechanisms of SVT?

Understanding the underlying mechanism is useful in understanding the clues on ECG. Ventricular rates in SVT may vary from 150 to 250 beats/min. However, the rate may be slower in older patients and in patients taking AV nodal blocking medications (i.e., calcium-channel blockers, β-blockers and digoxin).7

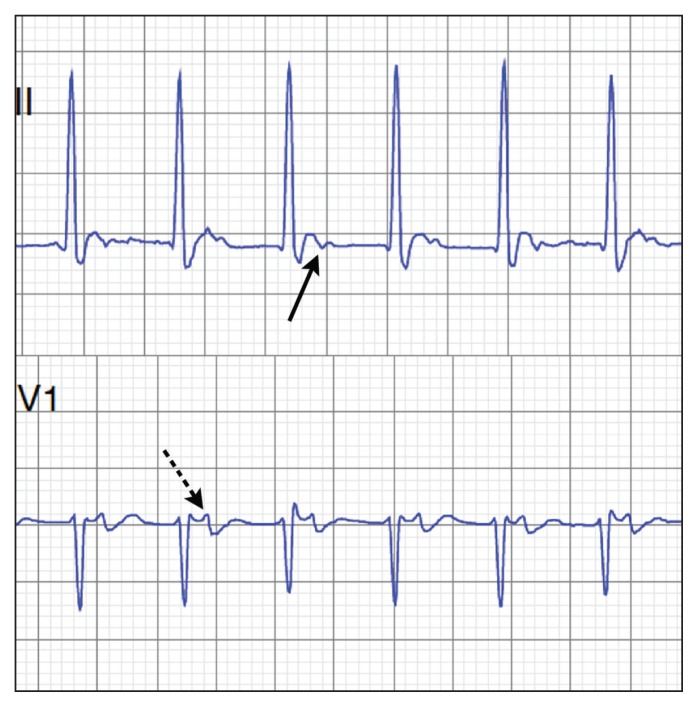

In patients with AVNRT, two functionally distinct pathways in the AV node — generally referred to as fast and slow pathways — are involved that may form an electrical circuit within the AV node. Clues on ECG include a pseudo R1 wave in lead V1 and a pseudo S wave in the inferior leads. These findings correspond to retrograde P waves seen after the QRS complex (Figure 2).8,9

Figure 2:

Electrocardiographic clues to the diagnosis of atrioventricular re-entrant tachycardia and atrioventricular nodal re-entrant tachycardia include a P wave following the QRS complex, as can be seen in lead II (solid arrow) and lead V1 (dotted arrow), and a short RP interval.

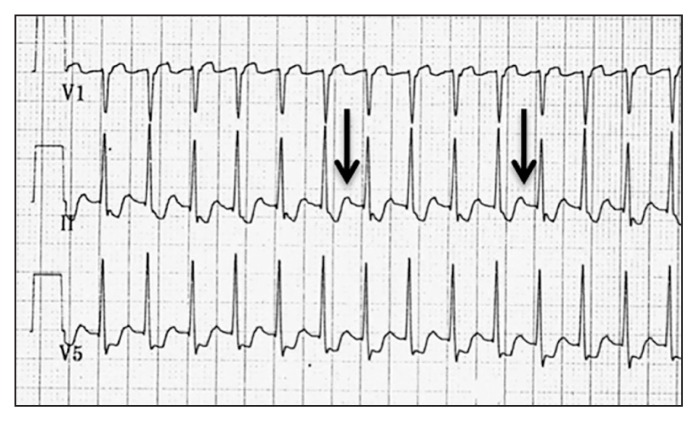

In patients with AVRT, the tachycardia involves both the AV node and an extranodal accessory pathway (bypass tract) that connects the myocardium of the atrium to the ventricle.10 In AVRT with a narrow QRS complex, a circuit forms from the anterograde conduction through the AV node and retrograde conduction through the accessory pathway. An ECG performed during the tachyarrhythmia may show retrograde P waves following the QRS complex. Once terminated, the resting ECG may show signs of pre-excitation: a delta wave with a widened QRS complex and a short PR interval. In Wolff–Parkinson–White syndrome, pre-excitation is seen on the resting ECG (Figure 3) coupled with symptoms of palpitations (e.g., re-entrant tachycardia involving the accessory pathway).7

Figure 3:

Electrocardiogram showing classic triad of an accessory pathway (bypass tract) in lead V6 — short PR interval, wide QRS complex and delta wave (arrow) — representing myocardial depolarization via anterograde conduction along the bypass tract.

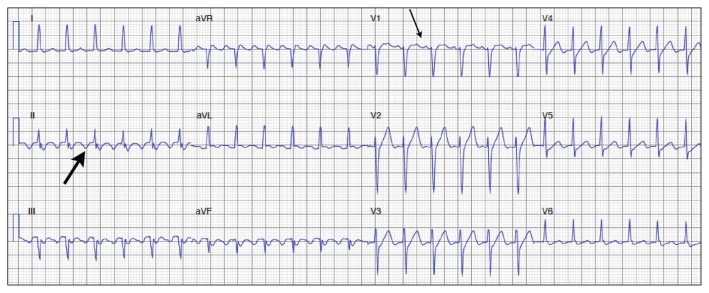

Atrial tachycardia originates from a focal atrial site and is characterized by regular and organized atrial activity (Figure 4). The mechanism of atrial tachycardia is a result of a micro–re-entrant circuit in the atrium or an automatic focus.7 Depending on the atrial rate and the AV nodal conduction properties, 2:1 or variable conduction may be seen. Diagnostic clues on ECG include a warm-up phenomenon in which the atrial rate increases slightly over the first 5 to 10 seconds before stabilizing. On surface ECG, the P waves are usually seen before every QRS complex and have a different axis than a sinus P wave. At high atrial rates, the P waves may be embedded in the descending limb of the T wave or completely obscured by the T waves.7

Figure 4:

Electrocardiogram showing ectopic atrial tachycardia. The ectopic P wave (arrows) axis is positive in lead II. Although sinus tachycardia may give a similar P wave axis, the atrial rate of about 215 beats/min suggests atrial tachycardia. Electrophysiologic mapping confirmed an ectopic atrial focus in the right atrium.

Atrial flutter originates from an anatomic macro–re-entrant circuit in the atria. The most common (typical) atrial flutter involves counterclockwise conduction in the right atrium along an anatomic circuit including the cavotricuspid isthmus (the area between the inferior vena cava and the tricuspid annulus). Atrial flutter is associated with many conditions, including heart failure, obstructive sleep apnea, chronic pulmonary disease, previous stroke, hyperthyroidism, valvular heart disease, pericardial disease and postcardiac surgery.11,12 In regular SVT due to atrial flutter, the atrial rate is typically 300 beats/min with a 2:1 ventricular rate of 150 beats/min.7 It can be identified on the ECG as a sawtooth pattern of flutter waves that are negative in the inferior leads and positive in lead V1 (Figure 5).

Figure 5:

Electrocardiogram showing atrial flutter with 2:1 atrioventricular nodal conduction, with negative flutter waves in inferior leads II (thick arrow), III and aVF and positive flutter waves in V1 (thin arrow).

What is the diagnostic approach in the emergency department?

1. Assess hemodynamic status

When assessing a patient with suspected SVT, it is essential to assess the patient’s hemodynamic status quickly. Supraventricular tachycardias are rarely fatal, but the annual risk of sudden cardiac death is 0.02%–0.15% among patients with Wolff–Parkinson–White syndrome.13 Nonetheless, certain patients with cardiac comorbidities may not tolerate the underlying rapid ventricular rate, which may lead to hemodynamic instability, exacerbated congestive heart failure or angina. If the patient is deemed unstable because of the SVT, and a trial of vagal manoeuvres or intravenous adenosine is ineffective or not feasible, synchronized electrical cardioversion may be warranted.5

2. Assess the type of SVT

If the patient is hemodynamically and clinically stable, the most important diagnostic step is to obtain a 12-lead ECG. Once the ECG is obtained, the four-step approach outlined in Figure 1 is suggested to diagnose the underlying rhythm.

First, determine whether the QRS complex is narrow (< 120 ms) or wide (≥ 120 ms). A narrow complex confirms the supraventricular origin of the arrhythmia; a wide complex may represent ventricular tachycardia or SVT with aberrancy.

Second, if the QRS complex is narrow, assess whether the rhythm is regular or irregular. An irregular rhythm generally excludes AVNRT and AVRT, and is more in favour of atrial fibrillation, or atrial flutter or tachycardia with variable conduction through the AV node. A narrow-complex tachycardia with a regular rhythm is likely to be sinus tachycardia, AVRT, AVNRT, atrial flutter or atrial tachycardia.

Third, to diagnose the mechanism behind the narrow-complex tachycardia, look closely for any sign of atrial activity or P waves.

If a P wave is seen, the final step is to assess its place in the cardiac cycle by comparing the RP and PR intervals. If the RP interval is shorter than the PR interval (i.e., the P wave is seen immediately after the QRS complex), it is likely a retrograde P wave, and the most likely diagnosis is AVNRT or AVRT. If the RP interval is longer than the PR interval (i.e., the P wave is seen before the QRS complex), the most likely diagnosis is sinus tachycardia or atrial tachycardia. Atrial flutter may appear to fall in either category when presenting as a regular tachycardia with 2:1 conduction. Atrial flutter should be suspected when the heart rate is near 150 beats/min or when the P wave falls exactly in the middle of the RR interval (i.e., the length of the RP interval equals that of the PR interval), in which case another P wave (flutter wave) may be hidden in the QRS complex.

What is the initial treatment in hemodynamically stable patients?

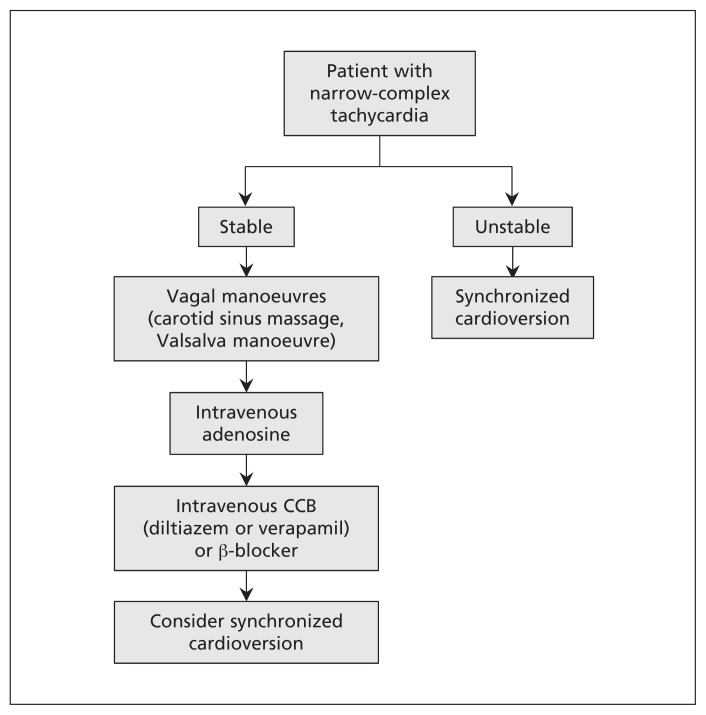

In hemodynamically stable patients with SVT, once the ECG is obtained, a diagnostic and therapeutic trial of a vagal manoeuvre is recommended under continuous ECG monitoring (Figure 6).5 In patients with AVRT or AVNRT, the vagal manoeuvre may terminate the circuit and restore normal sinus rhythm. In patients whose tachycardia does not involve the AV node (e.g., atrial flutter and atrial tachycardia), vagal manoeuvres or intravenous use of adenosine may slow the ventricular rate briefly and thus unmask the underlying atrial rhythm. We recommend beginning with the nonpharmacologic approach because it may obviate the need for adenosine, and it may identify patients who respond to the vagal manoeuvre and who can be taught to use it in future episodes.

Figure 6:

Clinical approach to patients with narrow-complex tachycardia. CCB = calcium-channel blocker.

Nonpharmacologic measures

Both carotid sinus massage and the Valsalva manoeuvre transiently augment vagal tone. Before performing carotid sinus massage, auscultation for carotid bruits must be done to avoid compressing an atherosclerotic plaque and provoking an embolic event. If no bruits are heard, the physician may ask the patient to turn his or her head to the opposite side of the massage. With two fingers, the physician compresses the carotid artery at the angle of the jaw. The manoeuvre should be repeated on both sides because some patients may respond better on one side than the other. Both carotid arteries should never be compressed at the same time.14 The Valsalva manoeuvre may be performed at the bedside by asking the patient to bear down against a closed glottis for 10–30 seconds.5,15 In our experience, we often put our hands on the patient’s abdomen and ask the patient to push it back up.

In a small prospective randomized case study, conversion occurred in only 9 (10.5%) of 86 patients with SVT who received carotid sinus massage.15 Contraindications to carotid sinus massage include carotid bruit, ventricular tachyarrhythmia, and stroke or myocardial infarction within the last three months. In older patients, extra precaution must be taken because of a 1% risk of transient neurologic complication occurring after carotid sinus massage and a 0.1% risk of persistent neurologic sequelae.16

An updated Cochrane review of the effectiveness of the Valsalva manoeuvre found a reversion rate varying from 19.4% to 54.3%.17 Recently, Appelboam and colleagues18 compared the standard Valsalva manoeuvre with a modified one consisting of performing the manoeuvre in the same semi-recumbent position but, immediately after the Valsalva strain, having patients lie flat and raising their legs to 45° for 15 seconds. The modified manoeuvre was found to be significantly more effective in terminating the SVT (43% v. 17%).

Pharmacologic measures

If vagal manoeuvres fail, a trial of intravenous adenosine may be given at an initial dose of 6 mg and a subsequent dose of 12 mg.5,19 Its use may serve as a diagnostic and therapeutic tool because it will terminate almost all AVNRTs and AVRTs by breaking the AV-nodal dependent circuit. In patients with non–AV-nodal dependent circuits (i.e., focal atrial tachycardia and atrial flutter), intravenous use of adenosine may prove to be a valuable diagnostic tool because the transient AV block may unmask ectopic atrial P waves or flutter waves.20 Patients should always be monitored by ECG during adenosine administration.

Adenosine may induce a wide range of transient bradycardias (including sinus arrest and asystole) as well as atrial fibrillation, SVT and ventricular tachycardia. Albeit very rare, cases of sustained ventricular tachycardia, ventricular fibrillation and Torsades de pointes have been reported.21 In patients with underlying coronary disease, adenosine may lead to coronary steal syndrome and subsequent myocardial ischemia. 22 Adenosine should therefore always be administered with an external pacemaker or defibrillator nearby.7

When vagal manoeuvres and adenosine fail to terminate a narrow-complex tachycardia, intravenous treatment with a nondihydropiridine calcium-channel blocker (e.g., diltiazem and verapamil) or β-blocker may be used. Calcium-channel blockers terminate 64%–98% of SVTs in hemodynamically stable patients. Administering a calcium-channel blocker intravenously over 20 minutes has been shown to reduce the rate of hypotension.23 There are fewer data supporting the use of β-blockers in the acute treatment of SVT; however, they are considered reasonable choices because of their safety profile.5,23

If all aforementioned pharmacologic therapies fail, synchronized cardioversion is recommended, even in hemodynamically stable patients.5

In patients presenting in atrial fibrillation who have known Wolff–Parkinson–White or new pre-excitation pattern on ECG, the use of potent AV-nodal blockers (i.e., β-blockers, diltiazem, verapamil and digoxin) should be avoided because these medications may potentiate conduction over the accessory pathway and lead to potentially life-threatening ventricular arrhythmias. In these cases, intravenous use of procainamide is the preferred approach in the acute setting.24

Who should be referred for radiofrequency catheter ablation?

All patients with symptomatic or recurrent episodes of AVNRT, AVRT, atrial flutter or atrial tachycardia should be referred for consideration of radiofrequency catheter ablation as first-line treatment.5 Definitive treatment improves quality of life, reduces anxiety and is cost-effective in symptomatic individuals.25–28 In a US study comparing radiofrequency catheter ablation with long-term medical management in patients with monthly episodes of SVT, ablation was found to reduce medical costs by US$27 900 per patient and was associated with an improvement in life expectancy of 3.10 quality-adjusted life-years.25 Overall, the rate of major complications after radiofrequency catheter ablation is low (0.5%–3%) and varies with the type of SVT ablated.29

It is of paramount importance to consider patient preference before undergoing any invasive procedure. For patients who are rarely symptomatic of the SVT and are reluctant to undergo an invasive procedure, a more conservative approach may be considered.

For patients with symptomatic AVNRT, referral to an electrophysiologist is strongly suggested for confirmation of the diagnosis and possible ablation.5 Success rates of ablation have been reported to be greater than 90% with minimal risk of complications (1%–3%).30 A meta-analysis showed rates of complications following ablation in patients with AVNRT as follows: cardiac tamponade 0.1%, pulmonary embolus 0.2% and need for permanent pacemaker implantation 0.7%.29

For patients with symptomatic AVRT, catheter ablation is considered first-line treatment. Risk stratification should be noninvasive in asymptomatic patients with Wolff–Parkinson–White pattern found incidentally on resting ECG, especially in the pediatric population. An exercise stress test and ambulatory ECG (Holter) monitoring to assess anterograde conduction and the subsequent risk of sudden cardiac death is recommended.31 If inconclusive, it is reasonable to stratify risk with an invasive electrophysiologic study to assess the properties of the accessory pathway. Patients should be referred for catheter ablation after the first episode of AVNRT, AVRT, typical atrial flutter or refractory atrial tachycardia.5 Ablation success rates are reported to be 90%–95%, and the overall complication rate is less than 3%, with the most common being AV block (0.8%), pacemaker implantation (0.3%) and cardiac tamponade (0.4%).29,32

In patients with symptomatic focal atrial tachycardia, catheter ablation is the recommended first-line treatment. The success rate is 90%–95% with a complication rate of 1%–2%.5

For patients with typical atrial flutter, the success rate for single-procedure catheter ablation is excellent. A meta-analysis determined the success rate to be 92% for single-procedure ablation and 97% for multiple-procedure ablation, with an overall complication rate of 0.5%.29 The most common complications noted were AV block (0.4%) and pericardial effusion (0.3%). Nonetheless, about 10% of the patients had long-term recurrence of atrial flutter.29 About one-third of patients with atrial flutter who undergo ablation will develop atrial fibrillation.33,34 For these reasons, anticoagulation after successful ablation should be continued if the patient has a risk factor for embolic stroke. According to a Canadian guideline, oral anticoagulation is warranted in patients aged 65 years and older or in those with at least one of the following risk factors: congestive heart failure, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, or a history of stroke or transient ischemic attack.35 There is currently no evidence to support the discontinuation of oral anticoagulation after successful ablation of atrial flutter.

Conclusion

Supraventricular tachycardias are common among patients in the emergency department and in the office. Prompt recognition of the specific type of arrhythmia is essential to determine therapeutic management. All patients with symptomatic SVT should be referred to a cardiologist for assessment and management. Depending on patient preferences, curative radiofrequency ablation should be considered because of its high success rate, which will subsequently improve quality of life and reduce associated costs.

Key points

Supraventricular tachycardia represents a range of tachyarrhythmias originating from a circuit or focus involving the atria or the atrioventricular node.

The most common forms encountered in primary care are atrioventricular nodal re-entrant tachycardia, atrioventricular re-entrant tachycardia, atrial tachycardia and atrial flutter.

In patients with hemodynamically stable SVT, the first step is to obtain a 12-lead electrocardiogram; a diagnostic and therapeutic trial of vagal manoeuvres or intravenous adenosine may then be attempted.

Patients with symptomatic SVT should be referred to a cardiologist for assessment and management, with consideration of curative radiofrequency ablation owing to its high rate of success, low rate of complications and subsequent improvement in quality of life.

Patients with an asymptomatic accessory pathway should be referred for an exercise stress test, ambulatory ECG monitoring and possible electrophysiology study to assess their risk of arrhythmic events.

Acknowledgements

Vidal Essebag is a Canadian Institutes of Health Research Clinician Scientist. All images of ECGs were obtained with consent from the Virtual Cardiology app by McGill University cardiologists and cardiologists from Université Laval.

Footnotes

CMAJ Podcasts: author interview at https://soundcloud.com/cmajpodcasts/160079-view

Competing interests: None declared.

This article was solicited and has been peer reviewed.

Contributors: All of the authors contributed substantially to the conception and design of the review. Lior Bibas and Michael Levi performed the literature search. All of the authors drafted the manuscript and revised it critically, approved the final version to be published and agreed to act as guarantors of the work.

References

- 1.Murman DH, McDonald AJ, Pelletier AJ, et al. U.S. emergency department visits for supraventricular tachycardia, 1993–2003. Acad Emerg Med 2007;14:578–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Granada J, Uribe W, Chyou PH, et al. Incidence and predictors of atrial flutter in the general population. J Am Coll Cardiol 2000;36:2242–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Orejarena LA, Vidaillet H, Jr, DeStefano F, et al. Paroxysmal supraventricular tachycardia in the general population. J Am Coll Cardiol 1998;31:150–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Medi C, Kalman JM, Freedman SB. Supraventricular tachycardia. Med J Aust 2009;190:255–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Page RL, Joglar JA, Caldwell MA, et al. 2015 ACC/AHA/HRS guideline for the management of adult patients with supraventricular tachycardia: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines and the Heart Rhythm Society. J Am Coll Cardiol 2016;67:e27–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Porter MJ, Morton JB, Denman R, et al. Influence of age and gender on the mechanism of supraventricular tachycardia. Heart Rhythm 2004;1:393–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Link MS. Clinical practice. Evaluation and initial treatment of supraventricular tachycardia. N Engl J Med 2012;367:1438–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pieper SJ, Stanton MS. Narrow QRS complex tachycardias. Mayo Clin Proc 1995;70:371–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McGuire MA, Bourke JP, Robotin MC, et al. High resolution mapping of Koch’s triangle using sixty electrodes in humans with atrioventricular junctional (AV nodal) reentrant tachycardia. Circulation 1993;88:2315–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wolff L, Parkinson J, White PD. Bundle branch block with a short P-R interval in healthy young people prone to paroxysmal tachycardia. Am Heart J 1930;5:685–704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee KW, Yang Y, Scheinman MMUniversity of California-San Francisco, San Francisco, CA, USA. Atrial flutter: a review of its history, mechanisms, clinical features, and current therapy. Curr Probl Cardiol 2005;30:121–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bitter T, Fox H, Gaddam S, et al. Sleep-disordered breathing and cardiac arrhythmias. Can J Cardiol 2015;31:928–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Munger TM, Packer DL, Hammill S, et al. A population study of the natural history of Wolff–Parkinson–White syndrome in Olmsted County, Minnesota, 1953–1989. Circulation 1993; 87:866–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mann DL, Zipes DP, Libby P, et al. , editors. Braunwald’s heart disease: a textbook of cardiovascular medicine. 10th ed Philadelphia: Saunders; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lim SH, Anantharaman V, Teo WS, et al. Comparison of treatment of supraventricular tachycardia by Valsalva maneuver and carotid sinus massage. Ann Emerg Med 1998;31:30–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Richardson DA, Bexton R, Shaw FE, et al. Complications of carotid sinus massage — a prospective series of older patients. Age Ageing 2000;29:413–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Smith GD, Fry MM, Taylor D, et al. Effectiveness of the Valsalva Manoeuvre for reversion of supraventricular tachycardia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2015;(2):CD009502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Appelboam A, Reuben A, Mann C, et al. Postural modification to the standard Valsalva manoeuvre for emergency treatment of supraventricular tachycardias (REVERT): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2015;386:1747–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Neumar RW, Otto CW, Link MS, et al. Part 8: adult advanced cardiovascular life support: 2010 American Heart Association guidelines for cardiopulmonary resuscitation and emergency cardiovascular care. Circulation 2010;122(Suppl 3):S729–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rankin AC, Oldroyd KG, Chong E, et al. Value and limitations of adenosine in the diagnosis and treatment of narrow and broad complex tachycardias. Br Heart J 1989;62:195–203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mallet ML. Proarrhythmic effects of adenosine: a review of the literature. Emerg Med J 2004;21:408–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Strååt E, Henriksson P, Edlund A. Adenosine provokes myocardial ischaemia in patients with ischaemic heart disease without increasing cardiac work. J Intern Med 1991;230:319–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lim SH, Anantharaman V, Teo WS, et al. Slow infusion of calcium channel blockers compared with intravenous adenosine in the emergency treatment of supraventricular tachycardia. Resuscitation 2009;80:523–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Redfearn DP, Krahn AD, Skanes AC, et al. Use of medications in Wolff–Parkinson–White syndrome. Expert Opin Pharmacother 2005;6:955–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cheng CH, Sanders GD, Hlatky MA, et al. Cost-effectiveness of radiofrequency ablation for supraventricular tachycardia. Ann Intern Med 2000;133:864–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hogenhuis W, Stevens SK, Wang P, et al. Cost-effectiveness of radiofrequency ablation compared with other strategies in Wolff–Parkinson–White syndrome. Circulation 1993;88:II437–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.O’Callaghan PA, Meara M, Kongsgaard E, et al. Symptomatic improvement after radiofrequency catheter ablation for typical atrial flutter. Heart 2001;86:167–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yildirim O, Yontar OC, Semiz M, et al. The effect of radiofrequency ablation treatment on quality of life and anxiety in patients with supraventricular tachycardia. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci 2012;16:2108–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Spector P, Reynolds MR, Calkins H, et al. Meta-analysis of ablation of atrial flutter and supraventricular tachycardia. Am J Cardiol 2009;104:671–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Scheinman MM, Huang S. The 1998 NASPE prospective catheter ablation registry. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol 2000; 23: 1020–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cohen MI, Triedman JK, Cannon BC, et al. PACES/HRS expert consensus statement on the management of the asymptomatic young patient with a Wolff–Parkinson–White (WPW, ventricular preexcitation) electrocardiographic pattern: developed in partnership between the Pediatric and Congenital Electrophysiology Society (PACES) and the Heart Rhythm Society (HRS). Endorsed by the governing bodies of PACES, HRS, the American College of Cardiology Foundation (ACCF), the American Heart Association (AHA), the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP), and the Canadian Heart Rhythm Society (CHRS). Heart Rhythm 2012;9:1006–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chen SA, Tai CT. Ablation of atrioventricular accessory pathways: current technique — state of the art. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol 2001;24:1795–809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Joza J, Filion KB, Eberg M, et al. Prognostic value of atrial fibrillation inducibility after right atrial flutter ablation. Heart Rhythm 2014;11:1870–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pérez FJ, Schubert CM, Parvez B, et al. Long-term outcomes after catheter ablation of cavo-tricuspid isthmus dependent atrial flutter: a meta-analysis. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol 2009; 2:393–401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Verma A, Cairns JA, Mitchell LB, et al. 2014 focused update of the Canadian Cardiovascular Society Guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation. Can J Cardiol 2014;30:1114–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]