Abstract

Cholesterol has typically been considered an exogenous, disease-related factor in immunity; however, recent literature suggests that a paradigm shift is in order. Sterols are now recognized to ligate several immune receptors. Altered flux through the mevalonic acid synthesis pathway also appears to be a required event in the antiviral interferon response of macrophages and in the activation, proliferation, and differentiation of T cells. In this review, evidence is discussed that suggests an intrinsic, ‘professional’ role for sterols and oxysterols in macrophage and T cell immunity. Host defense may have been the original selection pressure behind the development of mechanisms for intracellular cholesterol homeostasis. Functional coupling between sterol metabolism and immunity has fundamental implications for health and disease.

Intracellular Sterol Flux: Rheostat of Innate and Adaptive Immune Responses

Cholesterol, by virtue of its planar 4-ring structure and asymmetric decoration with a hydroxyl group, plays a fundamental role in determining membrane integrity and fluidity in eukaryotic cells [1–3]. Vesicular and non-vesicular trafficking of cholesterol within cells maintains a range of cholesterol content across different intracellular membranes. Low cholesterol endows the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) with sensitivity to cholesterol sensing by the ER integral membrane protein Sterol Response Element Binding Protein (SREBP) Cleavage-Activating Protein (SCAP), but also makes the ER susceptible to dysfunction (i.e., ER stress) upon cholesterol overloading. On the other hand, high levels of cholesterol in the plasma membrane regulate signaling of membrane proteins to the environment. In order to maintain membrane integrity and avoid toxicity, cells possess complex homeostatic circuits for maintaining free (i.e., unesterified) cholesterol levels within a narrow range [4].

Cholesterol regulation has classically been considered a housekeeping function of cells, and its study, a discipline largely relegated to cell biologists. Until recently, cholesterol has generally been considered an exogenous influence upon immunity during disease, such as with pathologic cholesterol overloading of macrophages (‘foam cells’) in atherosclerosis. Recent literature, however, has shattered this paradigm by showing, remarkably, that several immune receptors (e.g., stimulator of interferon genes [STING], T cell receptor [TCR]-β, inflammasomes, Toll-like Receptors [TLRs], C-X-C chemokine receptor 2 [CXCR2], Epstein Barr Virus-induced 2 [Ebi2], the C-type lectin Mincle, and RAR-related orphan receptor [ROR]-γt) are regulated, either directly (i.e., by ligation) or indirectly, by sterols [5–12]. Moreover, it is now known that TCR and interferon receptor activation induce rapid changes in intracellular sterol metabolism that are required for T cell proliferation and antiviral host defense, respectively [5, 13, 14]. Conversely, blocked flux through the mevalonic acid synthesis pathway is sufficient to induce type I interferons and activate the inflammasome [5, 15].

It thus appears that sterols are dynamically regulated, bioactive, intrinsic players in the immune response, and the cellular sterolome is a rapidly malleable regulator of immunity that couples host defense to metabolism. A fast-growing number of roles for cholesterol has been identified in inflammation and immunity. In the present review, rather than attempt a comprehensive review of this wide-ranging literature, the emphasis will be upon intrinsic roles that have recently been identified for cellular sterols in cell-autonomous immune responses – in particular, innate responses of macrophages to TLR ligands, inflammasome activators, and virus; and adaptive responses of T cells to mitogens and differentiation factors.

Coupling of Intracellular Sterols to Macrophage Innate Immunity

A basic comprehension of intracellular cholesterol homeostasis and its regulation by oxysterols, reviewed in Box 1 and Figure I, is essential to understanding roles of sterols in immunity. It is now recognized that homeostatic cholesterol sensing and intracellular sterol flux directly regulate the inflammatory programming of macrophages. Key roles in immunity have been identified for oxysterols, both via Liver X Receptor (LXR)-dependent and -independent mechanisms, as well as for SREBPs, the mevalonic acid synthesis pathway, and cholesterol itself. In this emerging paradigm, intracellular sterols and inflammation are directly coupled in a circuit, suggesting that host defense and not cellular housekeeping may have been the original end-goal for, and evolutionary pressure behind, intracellular sterol management.

Box 1. A Brief Overview of Intracellular Cholesterol Homeostasis.

Cellular cholesterol homeostasis has recently been reviewed comprehensively [10, 75, 76]. In brief, cells regulate their cholesterol content via the opposing actions of two transcription factors: i) sterol response element binding protein-2 (SREBP2) – which induces genes that promote cholesterol uptake (e.g., low density lipoprotein receptor [LDLR]) and synthesis (e.g., hydroxyl-methylglutaryl coenzyme A reductase [HMGCR]); and ii) the Liver X Receptors (LXRα and -β) – which induce genes that reduce cholesterol uptake (i.e., inducible degrader of LDLR [IDOL]) and promote cholesterol efflux (e.g., ATP Binding Cassette transporter [ABC]A1 and ABCG1).

Under low cholesterol conditions, SREBP2, an ER transmembrane precursor protein, is escorted by the cholesterol-sensing ER chaperone protein SREBP cleavage-activating protein (SCAP) to the Golgi complex, where it is proteolytically cleaved, yielding an NH2-terminal domain basic helix-loop-helix transcription factor that migrates to the nucleus to induce target genes. LXRs meanwhile actively repress their targets by recruiting corepressors. During cholesterol excess, however, SREBP2 is sequestered in the ER due to binding of cholesterol and desmosterol (penultimate synthetic precursor to cholesterol) to SCAP, as well as binding of oxysterols to the SCAP-retention protein, insulin-induced gene (INSIG). Oxysterols and desmosterol on the other hand bind and activate LXRs, inducing coactivator-for-corepressor exchange and target gene induction. 24,25-epoxycholesterol, an oxysterol by-product of the mevalonic acid synthesis pathway, plus several oxysterols that are products of enzymatic oxidation of cholesterol itself (e.g., 25-hydroxycholesterol [25HC], 27HC, 24HC), coordinately inhibit SREBP2 and activate LXR via direct binding to INSIG and LXR, respectively. 25HC and 27HC also promote INSIG-dependent, proteasomal degradation of HMGCR.

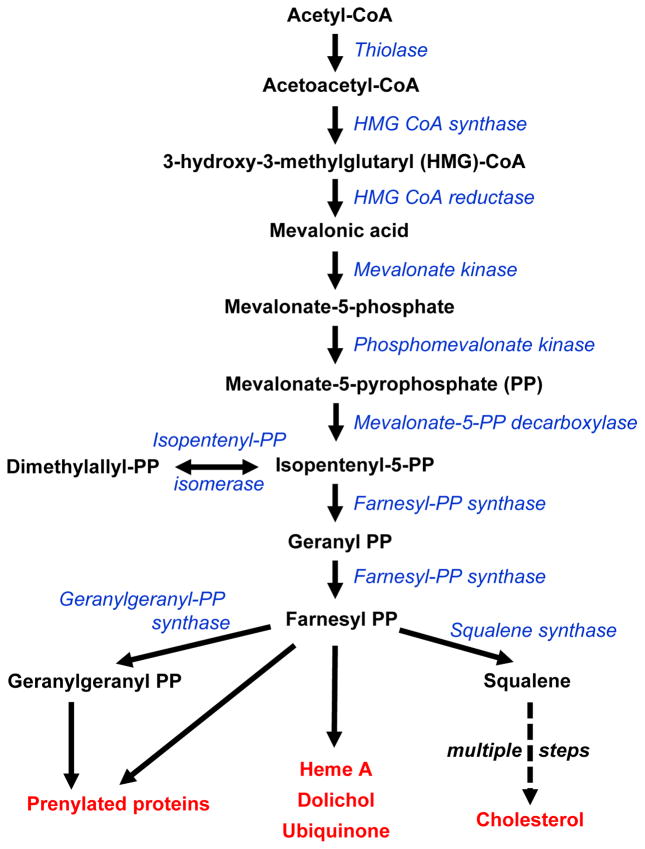

SREBP1a and SREBP1c, expressed from alternate promoters of a distinct gene (SREBF1) from that encoding SREBP2 (SREBF2), have a largely redundant set of target genes to that of SREBP2, but, particularly in the case of SREBP1c, ‘preferentially’ induce targets that promote fatty acid synthesis [75]. Moreover, it is important to note that the mevalonic acid synthesis pathway (shown in simplified form in Figure I) produces not only cholesterol (as well as multiple cholesterol biosynthetic intermediates), but also isoprenoids (i.e., geranylgeranyl-PP, farnesyl-PP) that support protein localization and function through post-translational modification (prenylation), as well as other non-sterol lipid products (e.g., ubiquinone, dolichol). Thus, SREBP activity in response to sterol sensing is directly linked to many critical sterol-independent functions in the cell.

Figure I. The Mevalonic Acid Synthesis Pathway.

Abbreviations used: CoA: coenzyme A, PP: Pyrophosphate

LXRs Integrate Sterol Sensing with Inflammation

Seminal work performed over a decade ago by Tontonoz and colleagues demonstrated that LXR activation suppresses nuclear factor (NF)-κB-dependent pro-inflammatory gene induction by lipopolysaccharide (LPS)[16]. Since that time, multiple, and, at times, seemingly contradictory anti-inflammatory mechanisms have been identified for LXR. The relative contribution, cell type-dependence, disease-dependence, and LXR isoform-dependence of these mechanisms remain uncertain. It has been reported that sumoylation of activated LXRs induces their tethering to, and suppression of, NF-κB, AP-1, and STAT-1 response elements in pro-inflammatory gene promoters [17, 18]. More recent work has challenged the importance of LXR sumoylation, suggesting instead that LXR-dependent induction of ATP Binding Cassette A1 transporter (ABCA1) may suppress TLR2 and TLR4 signaling at the plasma membrane of macrophages by depleting cholesterol in lipid rafts [19]. Contrary to this, however, another group has reported that the anti-inflammatory activity of LXR agonists is intact or even increased in Abca1−/−Abcg1−/− macrophages [20]. Given technical differences between the reports, further work will be required to clarify the importance of ABC transporters in this context. In macrophages, LXR also promotes ‘M2’ programming through indirect transcriptional means, by upregulating interferon regulatory factor 8 (IRF8) and thereby leading to arginase induction via interactive binding of IRF8 and PU.1 at a composite element in the arginase promoter [21]. Finally, LXRα has been shown to suppress trafficking of dendritic cells (DC) from tumors to lymph nodes in mice by reducing DC expression of CC chemokine receptor-7 [22]. Perhaps reflecting species-dependence, LXR has, however, also been reported to upregulate CCR7 in primary human DCs [23].

LXR activation has also been shown to induce anti-inflammatory omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) via upregulation of genes that mediate elongation and unsaturation of fatty acids [24]. Whether this leads to downstream generation of anti-inflammatory specialized pro-resolving lipid mediators (i.e., resolvins, protectins) remains to be determined. It has also recently been shown that in hepatocytes LXRα induction of lysophospholipid acyltransferase 3 (Lpcat3) reduces ER stress and associated cytokine induction via insertion of PUFAs into cellular phospholipids [25]. Interestingly, the potential for LXR-induced Lpcat3 on the other hand to augment LPS-induced eicosanoid release from macrophages has also recently been shown [26]. This appears to occur due to Lpcat3-dependent incorporation of arachidonic acid into membrane phospholipids.

Perhaps the evolutionarily original role for LXR as a sterol-inflammation coupler is its recently identified regulation of the homeostatic clearance functions of macrophages in vivo. Macrophage LXR senses the sterol burden of internalized apoptotic cell corpses and upregulates the efferocytosis receptor, Mer, in a feed-forward fashion [27]. Sterol-sensing by macrophage LXR also regulates the clearance of senescent neutrophils in the bone marrow, and thus plays a key role in circadian modulation of the hematopoietic niche and egress of hematopoietic progenitors into the circulation [28]. Of interest, LXRα was recently identified as a lineage-defining transcription factor required for the development of marginal zone macrophages in the spleen [29]. Taken together, these reports point toward the critical evolutionary crosstalk between lipid sensing and immunity, and identify LXR as a master regulator of these functions, both in homeostatic conditions and during inflammation.

Most reports to date that have probed LXR have used synthetic agonists. In other cases, supraphysiologic concentrations of LXR agonistic oxysterols have been tested ex vivo. Given this, the physiologic relevance and LXR-specificity of many of these findings are unclear. The identity of the endogenous sterol species that activate LXR in macrophages in vivo is uncertain in most cases, although it has recently been shown that regulated accumulation of desmosterol in lipid-overloaded foam cells is responsible for their LXR-dependent anti-inflammatory phenotype [30]. Future work involving LXR-null animals and lipidomics may be required to clarify physiologic roles for the LXRs and their native agonists in vivo.

25-hydroxycholesterol (25HC): a Pleiotropic Lipid Regulator of Inflammation

Among oxysterol agonists of LXR, 25HC, the product of oxidation of cholesterol by cholesterol-25-hydroxylase (Ch25h), has in recent years been assigned highly diverse, mixed effects on inflammation, most of which are LXR-independent [10]. These reports appear to suggest that 25HC may act as more of a context-dependent modulator of inflammatory responses. Unlike some other oxysterol-synthetic enzymes, Ch25h, an interferon-stimulated gene, is rapidly upregulated by TLR ligands, culminating in robust generation and release of 25HC by stimulated macrophages [31]. Suggesting that 25HC may act as a negative feedback regulator of LPS-induced inflammation, it has recently been shown to suppress production of mature IL-1β protein, both through inhibiting SREBP-dependent pro-IL-1β transcription, and through broadly suppressing the NLRP3, NLRC4, and AIM2 inflammasomes [7]. In contrast, another group has shown that 25HC amplifies inflammation by promoting recruitment of AP-1 to the promoters of TLR-responsive inflammatory genes through an LXR-independent pathway [32]. The relative contribution and context-dependence of the anti- vs. pro-inflammatory roles of 25HC, as well as whether 25HC may suppress inflammation through LXR-dependent mechanisms, remain uncertain at present.

Of interest, it was recently reported that 25HC and some other oxysterols (22R-HC, 24S-HC, 27-HC, 19-HC) chemoattract neutrophils to tumors via ligation of CXCR2 [9]. Although a full discussion of oxysterols in cell trafficking is outside the scope of the present review (for this, readers are referred to [10]), it is worth noting that 7α,25-HC, the product of secondary oxidation of 25HC via the enzyme Cyp7b1, was recently identified as a chemoattractant ligand for the G-protein coupled receptor, Ebi2 [33, 34]. In this context, the 7α,25-HC/Ebi2 axis plays a key role in positioning of B cells and CD4+ DCs within the spleen; thus, Ch25h−/− and Cyp7b1−/− mice, like Ebi2−/− mice, have reduced T cell-dependent antibody responses [33–35]. Taken together, it seems clear that innate and adaptive immunity are coupled directly to cellular sterol metabolism, and that oxysterols must now be recognized as ‘professional’ immune mediators.

SREBPs in Inflammasome Activation

Similar to the LXRs, SREBPs have recently been shown to play direct roles in inflammation, some of these, through newly discovered target genes that have extended the functional purview of the SREBP network. In endothelial cells, SREBP2 is activated by oscillatory flow and activates the NLRP3 inflammasome by transactivating NADPH oxidase 2 and NLRP3 [36]. Suggesting that SREBP2 and NLRP3 may moreover communicate in a feed-forward loop in some settings, it was recently reported that hepatitis C virus (HCV) activates SREBP2 in liver cells via NLRP3-dependent, caspase-1-mediated cleavage of the SREBP retention factor insulin-induced gene (INSIG)[37]. On the other hand, geranylgeranyl-pyrophosphate (GGPP), an isoprenoid product of the mevalonic acid synthesis pathway, suppresses the pyrin inflammasome through supporting K-ras/PI3K signaling [15]. Thus, it seems that SREBPs and mevalonic acid-derived lipids interestingly exert divergent effects upon different inflammasomes, potentially in a cell type- and stimulus-dependent manner.

Taken together, lipid synthesis and inflammasome activation appear to be integrated during the innate immune response, with SREBPs promoting inflammation in some contexts. What remains to be clarified is the extent to which physiological activation of SREBPs can suffice as a priming and/or triggering event for inflammasomes, as well as whether rapid changes in ER or mitochondrial-associated membrane cholesterol regulate the inflammasome. Teleologically, it seems plausible that expansion of the ER membrane by lipogenesis during the innate immune response may serve to buffer it against the ER stress associated with rapid cytokine production. Conversely, it is intriguing to consider that acute changes in membrane lipids may possibly be perceived as pro-inflammatory innate ‘danger signals.’ Altogether, it appears that IL-1β output is directly tuned to mevalonic acid pathway flux through multiple mechanisms.

Cholesterol Crystals as Damage-Associated Molecular Patterns

Recently, it has been shown that cholesterol crystals, which can form intracellularly following uptake of oxidized LDL (oxLDL), also activate NLRP3-dependent IL-1β production by inducing phagolysosomal damage in macrophages [15]. While oxLDL can prime the inflammasome by activating TLRs [15], cholesterol crystals also promote their own uptake in a feed-forward manner and also induce inflammasome-priming cytokines via activation of complement component C5a [38]. Cholesterol crystals also indirectly prime macrophages for IL-1β release in a transcellular manner, by inducing release of TLR-stimulatory extracellular traps from neutrophils (i.e., NETs)[39]. Interestingly, cholesterol crystals were also recently demonstrated to function as direct innate immune ligands, inducing pro-inflammatory cytokine production via ligation of Mincle, a scavenger receptor with a cholesterol interaction motif [11]. In other settings, dietary cholesterol, internalized via the receptor Niemann-Pick C1-like 1, also activates the inflammasome and IL-1β production in intestinal epithelial cells in vivo [40].

In aggregate, these reports indicate that cholesterol sensing by multiple receptors in a variety of myeloid and non-myeloid cell types, has the potential, particularly in a pro-inflammatory microenvironment, to activate the inflammasome. Cholesterol crystals – which essentially represent a failure of free cholesterol homeostasis – serve as pro-inflammatory danger signals that are detected by the immune system through both cell-autonomous and transcellular mechanisms. Future work will be required to identify the range of disease settings and organ systems in which cholesterol-induced inflammasome activation and NET release are operative.

Mevalonic Acid Synthesis Pathway and Oxysterols in Antiviral Host Defense

A key evolutionary function of inflammation – arguably, its original purpose – is host defense against pathogens. It may thus be unsurprising that, in recent years, several roles have also been identified for intracellular sterols in host defense. Multiple types of intracellular pathogens, ranging from virus, to bacteria, to parasites have been shown to co-opt cellular cholesterol handling for their benefit, generally promoting cholesterol accumulation for a variety of purposes, including support of cell entry and exit, energy utilization, and gene expression [41–43]. Conversely, it is now recognized that host reprogramming of sterol metabolism is a pivotal, and, likely, ancient mechanism of host defense against intracellular pathogens. As a comprehensive discussion of the importance of sterols in infectious disease is beyond the scope of the present review, here, the focus is on viral pathogenesis and antiviral host defense. To what extent these or analogous mechanisms apply to extracellular pathogens remains largely undetermined.

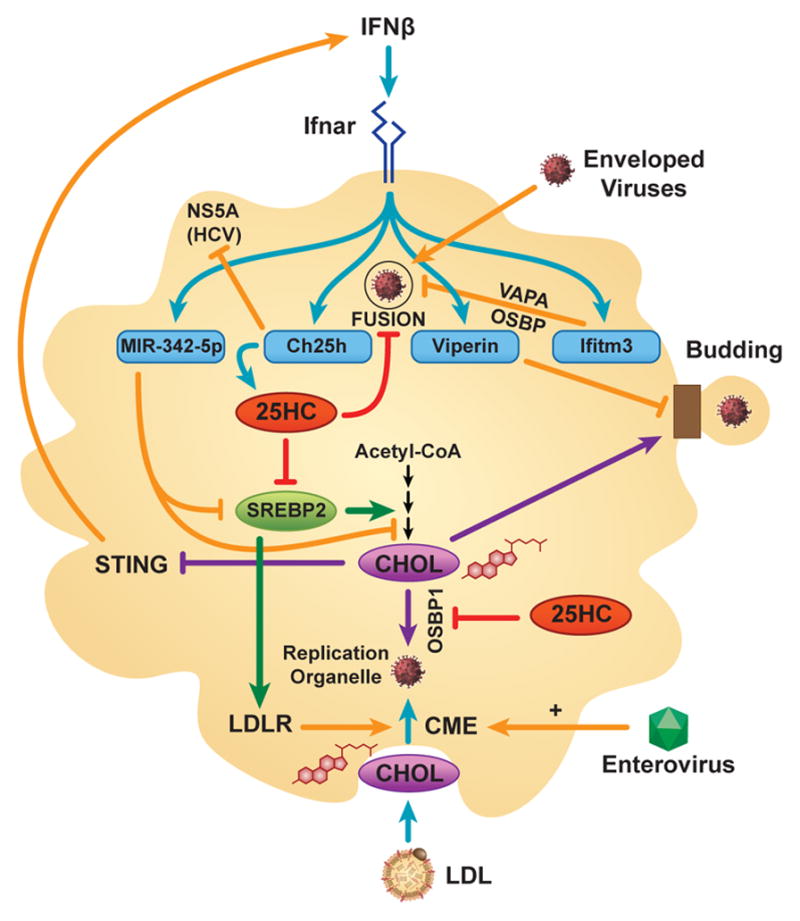

Intracellular membranes, derived from remodeling of the ER, Golgi complex, and/or other organelles in infected cells serve as platforms that enable effective assembly and replication for many viruses [41]. It is thought that viruses promote formation of these so-called ‘replication organelles’ (‘membranous webs’ in the case of HCV) and also cholesterol-enrich other subcellular membranes by pirating host cell mechanisms in order to increase synthesis, uptake, and redistribution of cholesterol within the infected cell (Figure 1). For example, HCV activates SREBPs, thereby driving synthesis of cholesterol and GGPP required for viral replication, and also promoting LDLR-dependent internalization of virus and cholesterol [44]. Similarly, West Nile Virus drives cholesterologenesis, relocalizing cholesterol-synthetic enzymes to replication sites in the cell [41]. In the case of Hantavirus and Andes Virus, SREBP2-dependent plasma membrane cholesterol enrichment is required for membrane fusion and viral entry [45, 46], and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) promotes budding from host cells by augmenting lipid raft cholesterol through antagonism of ABCA1 [47]. By contrast, enteroviruses enhance clathrin-mediated endocytosis in order to move plasma membrane and extracellular cholesterol internally to replication organelles, thereby facilitating viral RNA synthesis and polyprotein processing [48].

Figure 1. Interactions between the Sterol and Interferon Networks in Antiviral Host Defense.

In macrophages, interferon (IFN)-β induces several gene products (miR-342-5p, cholesterol-25-hydroxylase [Ch25h], viperin, interferon-induced transmembrane protein 3 [Ifitm3]) that inhibit virus by depleting cholesterol [CHOL] and isoprenoids required for viral gene expression in the replication organelle, and/or by reprogramming intracellular cholesterol trafficking. miR-342-5p suppresses the mevalonic acid synthesis pathway (depicted as multiple steps from acetyl-CoA to CHOL) through repressing SREBP2 and pathway enzymes. Ch25h-derived 25-hydroxycholesterol (25HC) inhibits SREBP2 activation, OSBP1-dependent cholesterol delivery to the replication organelle, and, along with Ifitm3, also blocks viral fusion/entry. Ch25h can also directly inhibit the HCV NS5A protein. Viperin impairs viral budding through altering raft lipids. IFNβ-induced depletion of newly synthesized cholesterol in the ER de-represses stimulator of IFN genes (STING), inducing IFNβ production. Enteroviruses promote clathrin-mediated endocytosis (CME) of cholesterol to the replication organelle, a pathway that can also be promoted by SREBP2-supported, LDLR-dependent uptake of extracellular cholesterol. ER = endoplasmic reticulum; HCV = Hepatitis C Virus; Ifnar = IFNα/β receptor; LDLR = low density lipoprotein receptor; OSBP = oxysterol binding protein; SREBP = sterol response element binding protein; VAPA = vesicle-associated membrane protein-associated protein A.

Mevalonic Acid Synthesis Pathway as Effector and Regulator of the Interferon Response

The interferon response is perhaps the best-described mechanism of host defense against viruses. Detection of virus by host cells induces type I interferons, which, via autocrine signaling through IFNα/β receptor (Ifnar), induce scores of ‘interferon-stimulated genes’, several with defined antiviral effects, but many others of unknown function. Remarkably, several groups have recently shown that shutdown of the mevalonic acid synthesis pathway is a major effector mechanism of interferons, and that cholesterol and isoprenoid deficiency both impair the life cycle of different viruses through multiple mechanisms (Figure 1). In a landmark paper, Ghazal and colleagues showed that virus-infected cells undergo Ifnar1-dependent reduction of mevalonic acid pathway flux, and that pathway inhibition impairs cytomegalovirus replication in a manner that can be reversed by metabolic rescue with geranylgeraniol (cell-permeant version of GGPP)[49]. By contrast, interferon-induced reduction in sterols mediates suppression of influenza A virus [50]. Interestingly, reduction in the pool size of newly synthesized cholesterol, either by interferon treatment or genetic intervention on the mevalonate pathway, promotes further interferon induction by activating the ER-resident immune receptor, STING [50]. This finding suggests that the sterol and interferon networks communicate as a metabolic-immune circuit, and that ER cholesterol is detected not just by the classical SCAP-SREBP system, but also by innate immune receptors. Suggesting yet further entanglement between sterol homeostasis and interferon-mediated antiviral responses, interferon-induced genes have also been identified that suppress virus by redistributing intracellular cholesterol. For example, interferon-inducible transmembrane protein 3 blocks viral fusion/entry in endosomes by interfering with the interaction between the cholesterol trafficking proteins vesicle-membrane-protein-associated protein A and oxysterol-binding protein (OSBP), thereby causing an accumulation of cholesterol in late endosomes, that ultimately blocks viral fusion [51].

Recently, the mechanisms by which interferon-induced genes suppress the mevalonic acid synthesis pathway have begun to be defined (Figure 1). Viperin inhibits the synthetic enzyme farnesyl diphosphate synthase through direct interaction [52]. Ch25h likely inhibits the mevalonic acid pathway through its SREBP-inhibitory product, 25HC [50]. In the case of hepatocytes, 25HC also induces expression of the SREBF2- and LDLR-targeting microRNA, miR-185, thereby inhibiting formation of the HCV membranous web [53]. miR-342-5p, an interferon-induced microRNA, exerts antiviral effects against multiple pathogenic viruses ranging from cytomegalovirus to influenza A through direct, multi-hit targeting not only of SREBF-2, but also IDI1 and SC4MOL, two mevalonic acid pathway enzymes [50].

Translating these insights in a therapeutic approach, recent studies have corroborated that combination targeting of multiple enzymes in the mevalonic acid synthesis cascade is superior to single enzyme targeting for suppressing virus, due to pathway feedback. Thus, isolated inhibition of squalene synthase, the first sterol-committed enzyme immediately downstream of the off-branching of the pathway to isoprenoids (Figure I), leads to secondary GGPP overproduction and SREBP2 activation, thereby promoting HCV proliferation [54]. In this light, native oxysterols such as 25HC, which promote hydroxymethylglutaryl CoA reductase (HMGCR) degradation and also inhibit SREBPs, may be superior to statins at suppression of the mevalonic acid pathway and viral infection, because statins induce secondary SREBP2-dependent HMGCR upregulation [54]. An alternative strategy for achieving antiviral cholesterol depletion which has proven effective in the case of HIV and HCV infection is the upregulation of the transporter ABCA1 through pharmacologic activation of LXR [55, 56].

25-hydroxycholesterol: a broad-spectrum antiviral interferon-stimulated lipid

Remarkably, in addition to the roles identified for 25HC in inflammasome suppression, AP-1 regulation, and CXCR2 ligation discussed above, several reports have recently identified potent antiviral effects of 25HC on a wide range of enveloped and non-enveloped viruses [49, 57–60](Figure 1). Cheng and colleagues reported that 25HC, induced by autocrine interferon signaling, inhibits growth of multiple enveloped viruses (e.g., HIV, Ebola virus, herpes simplex virus) in cultured cells by blocking viral fusion/entry through SREBP-independent, direct effects on the host cell membrane [58]. By contrast, Ghazal and colleagues found that 25HC (as well as 27HC and 24,25-epoxycholesterol) suppress post-entry viral growth, at least in part, through SREBP-dependent mevalonic acid pathway inhibition [59]. In the case of HCV, 25HC exerts a minor inhibitory effect on viral-host cell fusion, with its major effect being to inhibit RNA replication through blocking membranous web biogenesis [61]. The enzyme CH25H can also itself (i.e., in a 25HC-independent manner) interact with the NS5A protein of HCV and inhibit its dimerization, thereby suppressing viral replication [62]. Although 25HC does not inhibit adenovirus [49, 58], it, along with 27HC, suppresses several other non-enveloped viruses, including human papillomavirus-16, human rotavirus, and human rhinovirus [57, 60]. An antiviral mechanism that has recently been defined for 25HC in the case of rhinovirus involves cholesterol trafficking. 25HC suppresses rhinovirus by binding to the lipid-exchange protein OSBP1 and locking it in a transfer-inactive state, thereby blocking a cholesterol-phosphatidylinositol 4-phosphate countercurrent at ER-Golgi contact sites that is required for formation of the replication organelle [60]. 25HC may also exert broad-spectrum antiviral activity via SREBP- and LXR-independent induction of the integrated stress response in macrophages [63]. Taken together, it seems clear that 25HC has multiple, redundant antiviral actions, and that it resides squarely at the interface between sterol metabolism and host defense. This suggests that these two functions of the cell, metabolism and immunity, are coupled and perhaps even inseparable, and raises the yet larger question of whether sterols also regulate the biology of uninfected leukocytes, such as during development, differentiation, and adaptive responses to the environment.

Dynamic Sterol Fluxes Regulate T Cell Immunity

Recent literature has, in fact, begun to reveal that sterol metabolism plays a remarkably central role in lymphocyte biology. Cholesterol is now thought to serve as a metabolic checkpoint for T cell proliferation and TCR signaling, with induction of lipid synthesis during T cell activation being linked to bioenergetic programs that together determine T cell fitness. Moreover, emerging evidence suggests that cell-specific sterol metabolite profiles may also underlie T cell development during health and differentiation during disease.

Cholesterol as a Metabolic Checkpoint for T Cell Proliferation

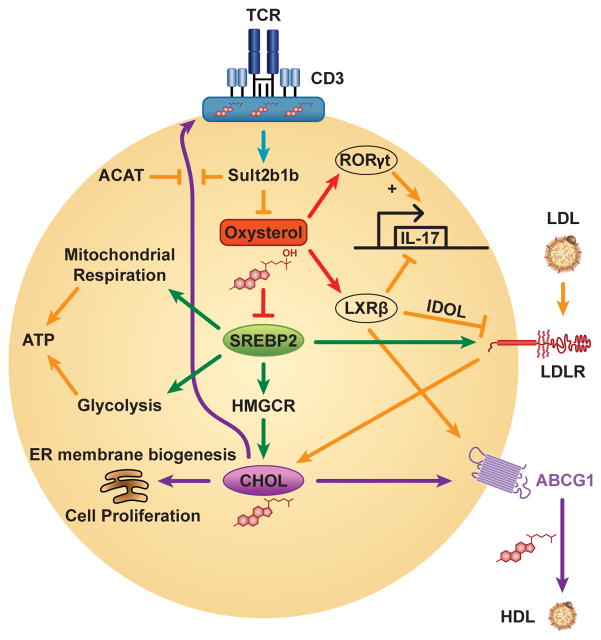

In a seminal paper, Bensinger et al. reported that cellular cholesterol enrichment occurs rapidly in CD4+ T cells upon activation, and is required for cell proliferation [13]. This arises from suppression of LXRβ (and its targets) and activation of SREBP2 (and its targets) due, in part, to inactivating sulfation of oxysterols by sulfotransferase family 2b member 1 (Sult2b1)[13](Figure 2). Similar lipogenic requirements for proliferation are observed in CD8+ T cells – including in the context of antigen-specific viral responses [13, 14], regulatory T cells [64], and B cells [13], suggesting that cholesterol may serve as a general signal of cell fitness for proliferation. Conversely, LXRβ suppresses cell cycle progression and proliferation, both in naive and activated cells, through induction of the efflux transporter ABCG1 and subsequent cellular cholesterol depletion [13].

Figure 2. Integrated Changes in Sterol Metabolism Program the Activated T Cell.

After T cell receptor (TCR) ligation, sulfotransferase family 2b member 1b (Sult2b1b) sulfates oxysterols, inactivating them as liver X receptor (LXR) agonists and sterol response element binding protein 2 (SREBP2) inhibitors, and also generates cholesterol-sulfate, which displaces lipid raft cholesterol from binding to TCRβ. Some oxysterols and cholesterol biosynthetic intermediates (not shown) activate the IL-17-promoting nuclear receptor RAR-related orphan receptor (ROR)γt, whereas LXRβ indirectly inhibits IL-17 transcription. LXRβ also opposes SREBP2-dependent cholesterol (CHOL) accumulation through IDOL-dependent degradation of the low density lipoprotein receptor (LDLR) and induction of the cholesterol efflux transporter ABCG1. In addition to promoting ER membrane biogenesis through lipid accumulation, SREBP2 programs bioenergetics through supporting mitochondrial respiration and glycolysis. The cholesterol esterification enzyme, acyl-coenzyme A:cholesterol acyltransferase 1 (ACAT1) regulates TCR signaling in CD8+ T cells by limiting levels of plasma membrane free cholesterol. ABCG1 = ATP Binding Cassette transporter G1; ER = endoplasmic reticulum; HDL = high density lipoprotein; HMGCR = hydroxymethylglutaryl-Coenzyme A reductase; IDOL = inducible degrader of the LDLR.

Whereas the mechanisms that regulate Sult2b1 remain unclear, SREBP2 activation has been shown to be PI3K-mTOR-dependent in activated T cells [14, 64]. Interestingly, SREBP2 is required not only for rapid cholesterol synthesis, but also for the enhanced glycolysis and mitochondrial respiration that support cell blasting [14, 64]. Thus, SREBP2 integrates reprogramming of cholesterologenesis with cellular bioenergetics in activated T cells. Given that ubiquinone, a key electron carrier of the electron transport chain, is prenylated, it seems plausible that SREBP2 may support mitochondrial energetics through driving the mevalonic acid synthesis pathway (Figure I). Mechanisms have also been proposed by which glycolytic and Krebs cycle metabolites may promote lipogenesis through serving as a source in the cytoplasm of the lipid building block, acetyl-coA [65].

One key question that remains incompletely resolved is the identity of the subcellular compartment(s) in which cholesterol regulates cell proliferation, and whether this may be context-dependent. SREBP-insufficient T cells have normal TCR signaling in the face of proliferative failure [14]. This suggests that SREBP2 does not control proliferation through regulating the cholesterol content of plasma membrane lipid rafts (cholesterol-sensitive membrane microdomains in which TCR signaling is activated [66]). Instead, it may suggest that the cholesterol content of the ER, where rapid membrane biogenesis is required during proliferation, is critical. On the other hand, Abcg1−/− T cells are hyperproliferative due to enhanced TCR signaling, likely stemming from augmented lipid raft cholesterol [67]. Indeed, suggesting that plasma membrane cholesterol levels may be an important determinant of the signaling traits of T cell subsets, it has been shown that the relatively high TCR signaling strength of γδ as compared to αβ T cells may arise from their increased plasma membrane cholesterol and lipid raft formation [68].

Membrane Cholesterol as an Allosteric Regulator of TCR Signaling

Recently, it has been shown that cholesterol regulates TCR signaling not only through membrane raft formation, but also through serving as a structural component of the TCR complex. Plasma membrane cholesterol binds directly to the TCRβ chain in vivo, promoting TCR dimerization and nanoclustering, and thereby enhancing receptor avidity to multivalent MHC-peptide [6]. This phenomenon appears to be regulated metabolically, and in a cell-specific manner. Thus, acyl-coenzyme A:cholesterol acyltransferase 1 (ACAT1), a cholesterol esterification enzyme, restrains TCR clustering and signaling, cell proliferation, and formation of the immunological synapse in CD8+ but not CD4+ T cells by reducing levels of free cholesterol in the plasma membrane [69]. The reasons for the CD8+ T cell specificity of this mechanism remain unclear. Interestingly, cholesterol sulfate, which is produced in vivo by the action of Sult2b1 upon cholesterol, disrupts TCR nanoclusters, decreases TCR avidity, and inhibits TCR signaling by displacing TCRβ-bound cholesterol [70]. The extent to which Sult2b1-derived cholesterol sulfate may serve as a dynamic negative feedback regulator of TCR activation in vivo is uncertain, but evidence does suggest that it plays a role in thymic selection through differential regulation of TCR signaling in thymic T cell subsets [70]. Adding yet further complexity to the picture, it was recently reported that cholesterol binding may serve a dual role in TCR signaling, promoting TCR avidity, but also restraining spontaneous signaling by keeping the TCR in an inactive allosteric conformation that cannot be phosphorylated [71]. Taken together, it appears that cholesterol and its metabolites may serve to fine-tune the setpoint for TCR activation, possibly in a developmental, cell-specific, and stimulus-dependent manner. Given that TCR nanoclustering is known to increase from naive T cells to effector and memory T cells [70], it is intriguing to consider that developmentally regulated cholesterol metabolism may possibly interact with the environment in the programming of lymphocytes.

Complex Roles for Sterols in Th17 Differentiation

It was recently discovered that sterols not only regulate T cell proliferation and TCR signaling, but that they also play a key role in T cell differentiation. Two oxysterols – 7α,27-OHC and 7β,27-OHC – are reportedly preferentially produced by T helper (Th)17 cells as compared to Th1 cells, and act as direct RORγt agonists, enhancing the differentiation of Th17 cells [72]. Further evidence may however be required to better prove the status of these two oxysterols as bona fide endogenous RORγt ligands in mice and humans. Other groups have reported that mevalonic acid pathway activity drives the intracellular accumulation of cholesterol biosynthetic intermediates during Th17 differentiation, and that either desmosterol and desmosterol-sulfate [12], or a sterol(s) in the pathway downstream of lanosterol and upstream of zymosterol [73] are likely endogenous RORγt agonists. Indeed, evidence suggests that multiple different cholesterol synthetic intermediates, potentially including non-canonical species, activate RORγt [73]. It thus seems likely that more than one species may be active in vivo, and that the profile of RORγt agonists within IL-17+ T cells may possibly vary across cell type, cytokine milieu, and activation status. Given that deletion of cholesterol biosynthetic pathway enzymes induces non-physiological accumulation of precursors and, potentially, non-canonical species, future studies will likely need to correlate careful, global measurements of the cellular sterolome with biochemical and functional measurements.

Interestingly, LXR suppresses Th17 differentiation. This occurs in part due to the LXR target SREBP1 binding to the IL-17 promoter and interfering with aryl hydrocarbon receptor-dependent IL-17 transcription [74]. Mitigating this effect, it appears that during Th17 differentiation, the LXR network is suppressed by sulfation of oxysterol agonists [73]. Taken together, while many interesting questions remain to addressed in upcoming years, it appears clear that dynamic shifts in sterol species, induced through integrated changes in multiple metabolic enzymes, play a critical role in programming the biology of Th17 cells, and, potentially, other T cell subsets.

Concluding Remarks

Sterols bind directly to several immune receptors and dynamic changes in mevalonic acid pathway flux are required for innate and adaptive immune responses, as highlighted here in macrophages and T cells. Recent recognition of this has led to the realization that cholesterol metabolism is an intrinsic regulator and effector of cellular immunity, but many questions about its roles remain open (see Outstanding Questions). Among these, it will be important to reconcile the capacity of statins to activate the inflammasome [15] with their now very well-known anti-inflammatory properties. It is intriguing to consider that, in the modern era of dyslipidemia, looking to immunity may well offer valuable mechanistic insights and perhaps novel therapeutic avenues not just for inflammatory features of cardiovascular disease, but also for dysregulated cholesterol trafficking.

Outstanding questions.

How do oxysterols engage so many cellular receptors and what are the key oxysterols and oxysterol receptors that program innate and adaptive immune functions in vivo?

To what extent do oxysterols exert endocrine effects on the immune response (i.e., does tissue-specific production of oxysterols program immune cells in distant organs by communication via the bloodstream)?

Do oxysterols and/or oxysterol-targeting drugs represent novel therapeutic opportunities in immune-mediated disease?

What is the mechanism by which STING ‘senses’ and is suppressed by ER cholesterol?

Are there additional ER membrane proteins that regulate immunity through cholesterol sensing?

Do proteins of the oxysterol binding protein (OSBP) and OSBP-related protein (ORP) families regulate host defense, lymphocyte proliferation, and/or lymphocyte programming?

How are the mevalonic acid synthesis pathway and intracellular cholesterol trafficking integrated with bioenergetic programs (aerobic respiration, glycolysis) in immune cells?

Would more graded interventions upon intracellular cholesterol (e.g., treatment with oxysterols or multi-hit strategies on mevalonic acid synthesis pathway enzymes) be more effective and/or less toxic than statins at immunomodulation?

Would quantitative profiling of the ‘sterolome’ (i.e., cholesterol biosynthetic intermediates, oxysterols) in leukocytes or plasma be more informative than isolated measurement of cholesterol at predicting disease risk and/or responses to statin therapy?

How does 25HC suppress multiple inflammasomes?

What proportion/subset of overall interferon antiviral activity arises from SREBP2 inhibition and/or 25HC induction?

Trends.

Sterols bind directly to several different immune receptors, regulating cytokine expression, leukocyte migration, and T cell differentiation.

Interferon-induced suppression of the mevalonic acid synthesis pathway plays a central role in antiviral host defense.

T cell receptor (TCR)-induced activation of sterol biosynthesis is required for cell proliferation and differentiation.

Oxysterols, cholesterol crystals, and isoprenoids regulate activation of the inflammasome.

Cholesterol binds directly to the TCRβ chain, regulating receptor nanoclustering and activation.

Acknowledgments

The author thanks Paul Windsor for assistance with figure production. This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (Z01 ES102005).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Howe V, et al. Cholesterol homeostasis: How do cells sense sterol excess? Chemistry and physics of lipids. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.chemphyslip.2016.02.011. pii: S0009-3084(0016)30033-30030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lange Y, Steck TL. Active membrane cholesterol as a physiological effector. Chemistry and physics of lipids. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.chemphyslip.2016.02.003. pii: S0009-3084(0016)30015-30019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kulig W, et al. Cholesterol oxidation products and their biological importance. Chemistry and physics of lipids. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.chemphyslip.2016.03.001. pii: S0009-3084(0016)30034-30032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Radhakrishnan A, et al. Switch-like control of SREBP-2 transport triggered by small changes in ER cholesterol: a delicate balance. Cell metabolism. 2008;8:512–521. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2008.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.York AG, et al. Limiting Cholesterol Biosynthetic Flux Spontaneously Engages Type I IFN Signaling. Cell. 2015;163:1716–1729. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.11.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Molnar E, et al. Cholesterol and sphingomyelin drive ligand-independent T-cell antigen receptor nanoclustering. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2012;287:42664–42674. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.386045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Reboldi A, et al. Inflammation. 25-Hydroxycholesterol suppresses interleukin-1-driven inflammation downstream of type I interferon. Science. 2014;345:679–684. doi: 10.1126/science.1254790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tall AR, Yvan-Charvet L. Cholesterol, inflammation and innate immunity. Nature reviews Immunology. 2015;15:104–116. doi: 10.1038/nri3793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Raccosta L, et al. The oxysterol-CXCR2 axis plays a key role in the recruitment of tumor-promoting neutrophils. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2013;210:1711–1728. doi: 10.1084/jem.20130440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cyster JG, et al. 25-Hydroxycholesterols in innate and adaptive immunity. Nature reviews Immunology. 2014;14:731–743. doi: 10.1038/nri3755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kiyotake R, et al. Human Mincle Binds to Cholesterol Crystals and Triggers Innate Immune Responses. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2015;290:25322–25332. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M115.645234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hu X, et al. Sterol metabolism controls T(H)17 differentiation by generating endogenous RORgamma agonists. Nature chemical biology. 2015;11:141–147. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bensinger SJ, et al. LXR signaling couples sterol metabolism to proliferation in the acquired immune response. Cell. 2008;134:97–111. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.04.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kidani Y, et al. Sterol regulatory element-binding proteins are essential for the metabolic programming of effector T cells and adaptive immunity. Nature immunology. 2013;14:489–499. doi: 10.1038/ni.2570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Akula MK, et al. Control of the innate immune response by the mevalonate pathway. Nature immunology. 2016 doi: 10.1038/ni.3487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Joseph SB, et al. Reciprocal regulation of inflammation and lipid metabolism by liver X receptors. Nature medicine. 2003;9:213–219. doi: 10.1038/nm820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ghisletti S, et al. Parallel SUMOylation-dependent pathways mediate gene- and signal-specific transrepression by LXRs and PPARgamma. Molecular cell. 2007;25:57–70. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.11.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee JH, et al. Differential SUMOylation of LXRalpha and LXRbeta mediates transrepression of STAT1 inflammatory signaling in IFN-gamma-stimulated brain astrocytes. Molecular cell. 2009;35:806–817. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.07.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ito A, et al. LXRs link metabolism to inflammation through Abca1-dependent regulation of membrane composition and TLR signaling. eLife. 2015;4:e08009. doi: 10.7554/eLife.08009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kappus MS, et al. Activation of liver X receptor decreases atherosclerosis in Ldlr(−)/(−) mice in the absence of ATP-binding cassette transporters A1 and G1 in myeloid cells. Arteriosclerosis, thrombosis, and vascular biology. 2014;34:279–284. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.113.302781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pourcet B, et al. LXRalpha regulates macrophage arginase 1 through PU.1 and interferon regulatory factor 8. Circulation research. 2011;109:492–501. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.111.241810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Villablanca EJ, et al. Tumor-mediated liver X receptor-alpha activation inhibits CC chemokine receptor-7 expression on dendritic cells and dampens antitumor responses. Nature medicine. 2010;16:98–105. doi: 10.1038/nm.2074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Feig JE, et al. LXR promotes the maximal egress of monocyte-derived cells from mouse aortic plaques during atherosclerosis regression. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2010;120:4415–4424. doi: 10.1172/JCI38911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li P, et al. NCoR repression of LXRs restricts macrophage biosynthesis of insulin-sensitizing omega 3 fatty acids. Cell. 2013;155:200–214. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.08.054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rong X, et al. LXRs regulate ER stress and inflammation through dynamic modulation of membrane phospholipid composition. Cell metabolism. 2013;18:685–697. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2013.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ishibashi M, et al. Liver x receptor regulates arachidonic acid distribution and eicosanoid release in human macrophages: a key role for lysophosphatidylcholine acyltransferase 3. Arteriosclerosis, thrombosis, and vascular biology. 2013;33:1171–1179. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.112.300812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.NAG, et al. Apoptotic cells promote their own clearance and immune tolerance through activation of the nuclear receptor LXR. Immunity. 2009;31:245–258. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.06.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Casanova-Acebes M, et al. Rhythmic modulation of the hematopoietic niche through neutrophil clearance. Cell. 2013;153:1025–1035. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.04.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.NAG, et al. The nuclear receptor LXRalpha controls the functional specialization of splenic macrophages. Nature immunology. 2013;14:831–839. doi: 10.1038/ni.2622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Spann NJ, et al. Regulated accumulation of desmosterol integrates macrophage lipid metabolism and inflammatory responses. Cell. 2012;151:138–152. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.06.054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bauman DR, et al. 25-Hydroxycholesterol secreted by macrophages in response to Toll-like receptor activation suppresses immunoglobulin A production. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2009;106:16764–16769. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0909142106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gold ES, et al. 25-Hydroxycholesterol acts as an amplifier of inflammatory signaling. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2014;111:10666–10671. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1404271111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hannedouche S, et al. Oxysterols direct immune cell migration via EBI2. Nature. 2011;475:524–527. doi: 10.1038/nature10280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Liu C, et al. Oxysterols direct B-cell migration through EBI2. Nature. 2011;475:519–523. doi: 10.1038/nature10226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yi T, Cyster JG. EBI2-mediated bridging channel positioning supports splenic dendritic cell homeostasis and particulate antigen capture. eLife. 2013;2:e00757. doi: 10.7554/eLife.00757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Xiao H, et al. Sterol regulatory element binding protein 2 activation of NLRP3 inflammasome in endothelium mediates hemodynamic-induced atherosclerosis susceptibility. Circulation. 2013;128:632–642. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.002714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.McRae S, et al. The Hepatitis C Virus-induced NLRP3 Inflammasome Activates the Sterol Regulatory Element-binding Protein (SREBP) and Regulates Lipid Metabolism. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2016;291:3254–3267. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M115.694059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 38.Samstad EO, et al. Cholesterol crystals induce complement-dependent inflammasome activation and cytokine release. Journal of immunology. 2014;192:2837–2845. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1302484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Warnatsch A, et al. Inflammation. Neutrophil extracellular traps license macrophages for cytokine production in atherosclerosis. Science. 2015;349:316–320. doi: 10.1126/science.aaa8064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Progatzky F, et al. Dietary cholesterol directly induces acute inflammasome-dependent intestinal inflammation. Nature communications. 2014;5:5864. doi: 10.1038/ncomms6864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chukkapalli V, et al. Lipids at the interface of virus-host interactions. Current opinion in microbiology. 2012;15:512–518. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2012.05.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Coppens I. Targeting lipid biosynthesis and salvage in apicomplexan parasites for improved chemotherapies. Nature reviews Microbiology. 2013;11:823–835. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro3139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wipperman MF, et al. Pathogen roid rage: cholesterol utilization by Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Critical reviews in biochemistry and molecular biology. 2014;49:269–293. doi: 10.3109/10409238.2014.895700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Syed GH, et al. Hepatitis C virus hijacks host lipid metabolism. Trends in endocrinology and metabolism: TEM. 2010;21:33–40. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2009.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kleinfelter LM, et al. Haploid Genetic Screen Reveals a Profound and Direct Dependence on Cholesterol for Hantavirus Membrane Fusion. mBio. 2015;6:e00801. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00801-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Petersen J, et al. The major cellular sterol regulatory pathway is required for Andes virus infection. PLoS pathogens. 2014;10:e1003911. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cui HL, et al. HIV-1 Nef mobilizes lipid rafts in macrophages through a pathway that competes with ABCA1-dependent cholesterol efflux. Journal of lipid research. 2012;53:696–708. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M023119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ilnytska O, et al. Enteroviruses harness the cellular endocytic machinery to remodel the host cell cholesterol landscape for effective viral replication. Cell host & microbe. 2013;14:281–293. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2013.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Blanc M, et al. Host defense against viral infection involves interferon mediated down-regulation of sterol biosynthesis. PLoS biology. 2011;9:e1000598. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Robertson KA, et al. An Interferon Regulated MicroRNA Provides Broad Cell-Intrinsic Antiviral Immunity through Multihit Host-Directed Targeting of the Sterol Pathway. PLoS biology. 2016;14:e1002364. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1002364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Amini-Bavil-Olyaee S, et al. The antiviral effector IFITM3 disrupts intracellular cholesterol homeostasis to block viral entry. Cell host & microbe. 2013;13:452–464. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2013.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wang X, et al. The interferon-inducible protein viperin inhibits influenza virus release by perturbing lipid rafts. Cell host & microbe. 2007;2:96–105. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2007.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Singaravelu R, et al. MicroRNAs regulate the immunometabolic response to viral infection in the liver. Nature chemical biology. 2015;11:988–993. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Owens CM, et al. Chemical combinations elucidate pathway interactions and regulation relevant to Hepatitis C replication. Molecular systems biology. 2010;6:375. doi: 10.1038/msb.2010.32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Morrow MP, et al. Stimulation of the liver X receptor pathway inhibits HIV-1 replication via induction of ATP-binding cassette transporter A1. Molecular pharmacology. 2010;78:215–225. doi: 10.1124/mol.110.065029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bocchetta S, et al. Up-regulation of the ATP-binding cassette transporter A1 inhibits hepatitis C virus infection. PloS one. 2014;9:e92140. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0092140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Civra A, et al. Inhibition of pathogenic non-enveloped viruses by 25-hydroxycholesterol and 27-hydroxycholesterol. Scientific reports. 2014;4:7487. doi: 10.1038/srep07487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Liu SY, et al. Interferon-inducible cholesterol-25-hydroxylase broadly inhibits viral entry by production of 25-hydroxycholesterol. Immunity. 2013;38:92–105. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Blanc M, et al. The transcription factor STAT-1 couples macrophage synthesis of 25-hydroxycholesterol to the interferon antiviral response. Immunity. 2013;38:106–118. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Roulin PS, et al. Rhinovirus uses a phosphatidylinositol 4-phosphate/cholesterol counter-current for the formation of replication compartments at the ER-Golgi interface. Cell host & microbe. 2014;16:677–690. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2014.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Anggakusuma, et al. Interferon-inducible cholesterol-25-hydroxylase restricts hepatitis C virus replication through blockage of membranous web formation. Hepatology. 2015;62:702–714. doi: 10.1002/hep.27913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Chen Y, et al. Interferon-inducible cholesterol-25-hydroxylase inhibits hepatitis C virus replication via distinct mechanisms. Scientific reports. 2014;4:7242. doi: 10.1038/srep07242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Shibata N, et al. 25-Hydroxycholesterol activates the integrated stress response to reprogram transcription and translation in macrophages. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2013;288:35812–35823. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.519637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zeng H, et al. mTORC1 couples immune signals and metabolic programming to establish T(reg)-cell function. Nature. 2013;499:485–490. doi: 10.1038/nature12297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Thurnher M, Gruenbacher G. T lymphocyte regulation by mevalonate metabolism. Science signaling. 2015;8:re4. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2005970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Fessler MB, Parks JS. Intracellular lipid flux and membrane microdomains as organizing principles in inflammatory cell signaling. Journal of immunology. 2011;187:1529–1535. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1100253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Armstrong AJ, et al. ATP-binding cassette transporter G1 negatively regulates thymocyte and peripheral lymphocyte proliferation. Journal of immunology. 2010;184:173–183. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0902372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Cheng HY, et al. Increased cholesterol content in gammadelta (gammadelta) T lymphocytes differentially regulates their activation. PloS one. 2013;8:e63746. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0063746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Yang W, et al. Potentiating the antitumour response of CD8(+) T cells by modulating cholesterol metabolism. Nature. 2016;531:651–655. doi: 10.1038/nature17412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Wang F, et al. Inhibition of T cell receptor signaling by cholesterol sulfate, a naturally occurring derivative of membrane cholesterol. Nature immunology. 2016;17:844–850. doi: 10.1038/ni.3462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Swamy M, et al. A Cholesterol-Based Allostery Model of T Cell Receptor Phosphorylation. Immunity. 2016;44:1091–1101. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2016.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Soroosh P, et al. Oxysterols are agonist ligands of RORgammat and drive Th17 cell differentiation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2014;111:12163–12168. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1322807111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Santori FR, et al. Identification of natural RORgamma ligands that regulate the development of lymphoid cells. Cell metabolism. 2015;21:286–297. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2015.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Cui G, et al. Liver X receptor (LXR) mediates negative regulation of mouse and human Th17 differentiation. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2011;121:658–670. doi: 10.1172/JCI42974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Jeon TI, Osborne TF. SREBPs: metabolic integrators in physiology and metabolism. Trends in endocrinology and metabolism: TEM. 2012;23:65–72. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2011.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Spann NJ, Glass CK. Sterols and oxysterols in immune cell function. Nature immunology. 2013;14:893–900. doi: 10.1038/ni.2681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]