Abstract

Norovirus (NoV) infection is the leading cause of epidemic gastroenteritis globally, and can lead to detrimental chronic infection in immunocompromised hosts. Despite its prevalence as a cause of diarrheal illness, the study of human NoVs (HNoVs) has historically been limited by a paucity of models. The use of murine NoV (MNoV) to interrogate mechanisms of host control of viral infection has facilitated the exploration of different genetic mouse models, revealing roles for both innate and adaptive immunity in viral regulation. MNoV studies have also recently identified important interactions between the commensal micro-biota and NoV with clear extensions to HNoVs. In this review, we discuss the most current understanding of how the host, the microbiome, and their interactions regulate NoV infections.

Noroviruses: Tenacious Pathogens

In the United States alone, human noroviruses (HNoVs) are responsible for approximately 20 million cases of acute gastroenteritis annually, leading to over 70 000 hospitalizations and nearly 800 deaths [1]. HNoV infections are also a global problem, causing approximately US$60 billion in societal costs every year [2]. HNoVs cause a species-specific infection, but recent developments are overcoming the historical lack of cell culture and small animal models [3–5]. Nevertheless, the direct study of factors regulating HNoV pathogenesis in the natural host will always be limited. To counter this limitation, HNoV infections are studied in non-human hosts or related NoVs are investigated in their natural hosts as detailed in a recent review [6]. Among the available models, murine NoV (MNoV), first described in 2003, provides the most widely used, readily tractable model system to explore viral and host factors regulating NoV infection [7]. MNoV infection is studied in vitro macrophages, dendritic cells (DCs), and B cells [4,8], as well as in vivo in mice [9]. Together, these studies have revealed novel host pathways critical to the regulation of NoV infection, and facilitated the exploration of NoV interactions with the commensal microbiome, a critically important player in mucosal infection. In this review, first, we briefly summarize parameters of NoV infections including transmission, symptoms, and viral tropism. Second, we explore the known mechanisms of host regulation of NoVs, with a focus on innate and adaptive immune regulators. Lastly, we detail recent work exploring the interactions of NoVs with the microbiota, describing the coordinate effects of host and microbial control of NoVs, and providing a comprehensive examination of the complex interactions between NoV, host, and bacteria. Future studies of the multifaceted regulation of NoV infection using existing and newly developed models will undoubtedly yield new scientific insights that may ultimately reduce the global burden of disease.

NoV Infection and Disease

NoV is a genus in the Caliciviridae (see Glossary) family. These non-enveloped icosahedral viruses have a single-stranded, positive-sense RNA genome, and are classified into at least six genogroups on the basis of their nucleotide sequence [10]. Genogroup I (GI), GII, and GIV viruses infect humans, with GII being the most prevalent, while GV viruses infect rodents (Table 1) [11]. The NoV genome contains three to four open reading frames (ORFs). ORF1 encodes nonstructural proteins including viral protein, genome-linked (VPg) and the RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp). ORF2 and ORF3 encode structural capsid proteins VP1 and VP2, respectively [10]. ORF4 is only found in MNoVs and encodes virulence factor VF1 [12].

Table 1.

Major Mechanisms of Infection in HNoV and MNoV. Human and murine norovirus (HNoV and MNoV) infections exhibit distinct characteristics, such as symptomatology and known attachment factors/receptors, but share overlap in the carbohydrate nature of their attachment factors, in cellular tropism, as well as in harboring a potential for persistent viral shedding.

| Human norovirus | Murine norovirus | |

|---|---|---|

| Symptoms | Abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea [17,20,21] | Asymptomatic in wild-type mice; potential for lethality in immunocompromised mice (Table 2) |

| Duration of infection | Acute symptomatic phase (1–4 days), which may be followed by viral shedding for weeks to months [22–24] | Acute strains cleared in 7–10 days; persistent strains are shed for many months/lifetime of animal [24,30] |

| In vitro tropism | B cells and enterocytes [4,5] | Macrophages, dendritic cells, microglial cells, and B cells [4,8,44] |

| In vivo tropism | Intestinal epithelial cells, myeloid cells, and lymphoid cells in immunocompromised patients [40] | Intestinal epithelial cells, macrophages, dendritic cells, B cells, and Kupffer cells (stellate macrophages in the liver) in immunocompromised mice [4,41,42,72] |

| Known attachment factors and receptors | Histo-blood group antigens are attachment factors conferring susceptibility to most HNoV strains [51,52]. Some strains bind heparan sulfate, sialic acid, and β-galactosylceramide [81–83]. No proteinaceous receptors are known | Strain-dependent attachment factors include terminal sialic acid residues on gangliosides and glycoproteins, and glycans on N-linked proteins [79,80]; CD300LF and CD300LD are proteinaceous viral receptors [44,45] |

NoV transmission typically occurs by the fecal–oral route from contaminated surfaces, food or water, and by person-to-person spread [10] but transmission via droplets, through aerosolization of HNoV-containing vomitus, can also occur [13,14]. Outbreaks occur in places where people gather (e.g., cruise ships, day-care centers, hospitals). They are facilitated by the low numbers of virions able to cause infections (i.e., low infectious dose) [15,16], high amounts of viral shedding [17], high environmental stability of HNoV [18], and a relative viral resistance to disinfectants [19].

After an average 1.2-day incubation period, HNoV infection induces symptoms including abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea, which typically resolve within 1–4 days [17,20,21]. However, viral shedding may occur for weeks to months in asymptomatic healthy hosts [22], and years in immunocompromised patients [23]. The latter have been postulated to serve as a reservoir for future outbreaks [24]. There is no significant correlation between presentation of symptoms and viral burden, duration, or magnitude of NoV shedding, but enhanced cytokine responses correlate with HNoV symptoms and suggest immune mediation [17]. Complications can occur following acute infection and include postinfectious irritable bowel syndrome [25,26], life-threatening dehydration [27], necrotizing enterocolitis [28], and exacerbation of Crohn’s disease [29].

NoVs cause species-specific infections. Thus, HNoVs can only infect animal models with reduced immune responses [3]. Alternatively, models relying on the natural infection of surrogate viruses can be used (recently reviewed, [6,30]). MNoV, a natural mouse pathogen endemic to animal facilities throughout the world [31–33], has been the most widely used surrogate model. MNoV cultivation in multiple cell types in vitro, the ability to genetically manipulate both virus and host, and the use of acute [murine norovirus 1 (MNV-1)] and chronic (e.g., MNV.CR6, MNV-3) MNoV strains add to the strengths of this model system [24,30].

The cellular and tissue tropism is a critical determinant of pathogenesis and an active area of investigation in the NoV field (Table 1) [34]. Recently, a model was proposed based on experimental evidence, whereby MNoVs use microfold (M) cells to overcome the epithelial barrier in order to infect B cells, macrophages, and DCs in the intestine, before being trafficked to local lymph nodes and distal sites by DCs [35–38]. B cells are also targets for HNoVs [4], but other targets exist, since humans deficient in B cells are still susceptible to HNoV infection [39]. Recent immunofluorescence analysis of small intestinal biopsy samples from HNoV-infected immunocompromised patients revealed the presence of HNoV infection in intestinal epithelial cells, CD68+ or DC-SIGN+ phagocytes (e.g., macrophages, DCs), and CD3+ cells (T cells or intraepithelial lymphocytes) [40]. A tropism of HNoV for enterocytes was subsequently confirmed by cultivating HNoV in human intestinal enteroid monolayer cultures [5]. MNoV antigen is also observed in small intestinal epithelial cells of immunodeficient signal transducer and activator of transcription 1 (Stat1)- and recombination activating gene (Rag1)/Stat1-deficient mice [41,42]. Taken together, the data indicate that both MNoV and HNoVs share a tropism for intestinal immune and epithelial cells. However, whether all the same cell types are infected in immunocompetent hosts remains to be confirmed.

Cellular tropism of NoVs is determined at the level of virus entry [43]. This was confirmed recently following the identification of CD300LF and CD300LD as functional receptors for MNoV [44,45]. Expression of murine CD300LF and CD300LD in multiple nonsusceptible cells, including HeLa or HEK293T cells from nonmurine hosts, supported MNoV infection, while infection could be reduced by competition with soluble protein or antibody [44,45]. Expression of human CD300F was unable to substitute for murine CD300LF, nor was antihuman CD300F able to block infection, indicating that restriction of NoVs may be due to species-specific variation in these molecules, rendering them determinants of species specificity. CD300LF and CD300LD belong to a family of type I transmembrane proteins with an immunoglobulin-like extracellular domain that can bind lipids in the plasma membrane [46]. Both proteins are expressed in myeloid cells, which are known MNoV target cells [47,48]. These findings raise questions regarding their physiological role during MNoV infection in vivo. Preincubation of MNV-1 with soluble CD300LF prevents mortality of Stat1-deficient mice, and Cd300lf−/− mice are resistant to viral shedding following oral infection with MNV.CR6 [44]. Whether MNoV establishes tissue infection in Cd300lf−/− or CD300ld−/− mice, however, has not been reported. These data pave the way for future investigations into the molecular details governing NoV entry.

Another key player during NoV infection is fucosyltransferase 2, or FUT2, whose protein expression is critical for susceptibility to most (but not all) HNoV strains [49,50]. FUT2 activity is required during the synthesis of ABO histo-blood group antigens (HBGAs), which are attachment factors or receptors that facilitate binding of some caliciviruses to cells [51,52]. Some individuals harbor an inactivating mutation in FUT2, which leads to the absence of ABO antigens, and these individuals (nonsecretors) have lower susceptibility to symptomatic infection [53]. This is likely due to the inability of certain HNoV strains to infect enterocytes, since intestinal organoids from nonsecretors are resistant to infection by some HNoVs [5]. Antibodies that prevent the interaction between the virus and HBGAs correlate with development of protective immune responses to HNoV infection [54,55], and current vaccine and immunoprophylaxis strategies under development are aimed at eliciting antibodies that block HBGA binding [56,57]. Future studies will be required to understand the precise function(s) of different susceptibility factors during NoV infection, which in turn may influence vaccine design.

Host Immune Regulators of NoV

Host genes broadly important for immunity are critical in the control of HNoV infection, as evidenced by primary or secondary immunodeficiencies, which have been associated with chronic NoV infection [58]. The immune response and cytokines in particular may also control symptomatology in HNoV infection [17]. Serum T-helper type 1 (Th1), Th2 cytokines, and interleukin-8 (IL-8) were more elevated in symptomatic versus asymptomatic patients, despite equivalent viral titers [17]. However, the underlying genetic causes for these specific immune responses were not explored. Future work to identify additional human genes affecting HNoV infection and symptomatology will thus be important in order to aid in vaccine development and treatment. Recent NoV vaccination efforts (reviewed in [59]) have relied upon HNoV-recombinant viruslike particles, produced by spontaneous self-assembly of the capsid protein VP1, to provide insight into immune correlates of protection [54,56]. The advent of novel in vitro culture methods for HNoV [4,5] now makes development of live-attenuated vaccines possible, and may facilitate defining functional host immune responses to HNoV.

Genetic knockout mouse models have proved extremely tractable for interrogating and identifying specific host genes regulating NoV pathogenesis (Table 2). Indeed, MNoV was first identified in immunodeficient mice highlighting the importance of the type I interferon (IFN) pathway, including the type I IFN receptor, Ifnar1, and the downstream transcription factor Stat1 in MNoV control [9,60–63]. The production of, and response to, IFNs has been consistently shown to be important for MNoV regulation. Pattern recognition receptors for viral RNA including melanoma differentiation-associated protein 5 (MDA5), a retinoic acid-inducible gene (RIG-I)-like receptor, Toll-like-receptor 3 (TLR3), and nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain (NOD)-like receptor family member NLRP6 also limit viral replication in vivo [64,65]. Pattern recognition receptors stimulate transcription of IFNs by activating the IFN regulatory transcription factor (IRF) family members IRF3 and IRF7, which additionally control MNoV viral levels [60]. Ifnar1−/− mice, which lack the ability to respond to type I IFNs, die upon MNoV challenge [8,9,60–63]. This lethality phenotype is exacerbated by an additional mutation in Ifngr1, the type II IFN receptor, suggesting combinatorial antiviral effects of type I and II IFNs [61,66].

Table 2.

Host Genes Involved in MNoV Regulation. Mouse genes implicated in viral infection, innate immune control, and adaptive immune control of murine norovirus are presented. MNV-1 and MNV-1.CW3 (here CW3) are acute strains of MNoV that infect systemic organs and are cleared by wild-type (WT) mice, while CR3, CR6, MNV/Hannover, and MNV-3 are persistent strains of MNoV that infect the intestine, are shed into the feces, and are not cleared in WT mice.

| Viral infection | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gene | Role | MNoV strain(s) | In vitro effect | In vivo effect | Refs |

| Cd300lf and CD300ld | Viral receptors | CW3/CR6 | Myeloid cell lines and primary macrophages lacking Cd300lf or CD300ld are not infected | Oral CR6 infection is prevented in Cd300lf−/− mice | [44,45] |

| Rag2 and Il2rg | Development of Peyer’s patches and M cells | CW3/CR3 | MNoV is transcytosed by M-cell-like murine intestinal epithelial mlCcl2 cells | Oral MNoV infection is reduced in mice lacking M cells | [37,38] |

| Innate immunity | |||||

| Gene | Role | MNoV strain(s) | In vitro effect | In vivo effect | Refs |

| Mda5 | Viral recognition | MNV-1 | Higher viral replication and defective cytokine response in Mda5−/− dendritic cells | Higher viral replication in Mda5−/− mice | [64] |

| Tlr3 | Viral recognition | MNV-1 | No effect observed | Higher viral replication in Tlr3−/− mice | [64] |

| Nlrp6 | Viral recognition | MNV-1 | N/A | Higher viral replication and levels of fecal shedding in Nlrp6−/− mice, and virus persists in Nlrp6−/− mice | [65] |

| Irf3 | Induction of IFN | CW3 | Irf3−/−Irf7−/− dendritic cells and macrophages show higher viral replication, and macrophages show impaired IFN production | Higher viral replication in Irf3−/− mice | [60] |

| CR6 | N/A | Irf3−/− mice are resistant to the effects of antibiotics in preventing infection | [68] | ||

| Irf7 | Induction of IFN | CW3 | Irf3−/−Irf7−/− dendritic cells and macrophages show higher viral replication, and macrophages show impaired IFN production | Higher viral replication in Irf7−/− mice | [60] |

| Ifnar1 | Type I IFN response | MNV-1/CW3 | Ifnar1−/− dendritic cells and macrophages show higher viral replication | Ifnar1−/− mice succumb to lethal infection, virus replicates to higher level, and virus persists in conditional knockout mice lacking Ifnar1 in dendritic cells or macrophages | [8,9,60–63] |

| CR6 | N/A | Enteric virus infects systemically in Ifnar1−/− mice | [68,69] | ||

| Ifngr1 | Type II IFN response | CW3 | N/A | Addition of Ifngr1 deficiency to type I IFN receptor deficiency causes increased viral replication and mortality | [61,66] |

| Ifnlr1 | Type III IFN response | CR6 | N/A | Higher viral replication and levels of fecal shedding in Ifnlr1−/− mice, and Ifnlr1−/− mice are resistant to the effects of antibiotics in preventing infection | [67,68] |

| Stat1 | Type I, II, and III IFN response | MNV-1/CW3 | Stat1−/− dendritic cells and macrophages show higher viral replication, and Stat1 is required for IFN-γ-mediated inhibition of MNoV replication in macrophages | Stat1−/− mice succumb to lethal infection | [8,9,66] |

| CR6 | N/A | Higher viral replication and levels of fecal shedding in Stat1−/− mice, and Stat1−/− mice are resistant to the effects of antibiotics in preventing infection | [67,68] | ||

| Irf1 | Type II IFN Response | CW3 | Irf1 is required for IFN-γ-mediated inhibition of MNoV replication in macrophages | Addition of Irf1 deficiency to type I IFN receptor deficiency causes increased viral replication and mortality | [66] |

| Atg5-Atg12, Atg7, and Atg16L1 | Type II IFN response | CW3 | Atg5–Atg12, Atg7, and Atg16L1 are required for IFN-γ-mediated inhibition of MNoV replication in macrophages | Addition of macrophage-specific Atg5-deficiency to type I IFN receptor deficiency causes increased viral replication and mortality | [61] |

| CR6 | N/A | Persistent viral infection induces intestinal pathology in Atg16L1-hypomorphic mice, dependent upon TNF-α and IFN-γ, though viral levels are similar to wild-type mice | [71] | ||

| Il10 | Anti-inflammatory cytokine | MNV/Hannover1 | N/A | Persistent viral infection induces intestinal pathology in Il10-deficient mice; though overall viral levels are similar to wild-type mice, MNoV localization is altered at early time points in knockout mice | [72] |

| Adaptive immunity | |||||

| Gene | Role | MNoV strain(s) | In vitro effect | In vivo effect | Refs |

| Rag1 | B- and T-lymphocyte development | CW3/MNV-3 | N/A | MNoV persists in Rag1−/− mice, and adoptively transferred immune splenocytes can clear infection; adoptively transferred MNV-specific CD8+ T cells can decrease viral loads | [63,73–75] |

| Ighm/muMt | B-lymphocyte development | CW3/MNV-3 | N/A | MNoV persists in muMt−/− mice; adoptively transferred immune splenocytes derived from B-cell-deficient mice or antibody production-deficient mice are unable to efficiently clear persistent infection in Rag1−/− mice; B cells are critical for protective immunity | [63,73,74,76] |

| MHC II | CD4+ T-cell development | CW3/MNV-3 | N/A | MHC II −/− mice have higher viral titers in the ileum than wild-type mice, but clear infection normally; CD4+ T cells are critical for protective immunity | [63,74,76] |

| MHC I and β2M | CD8+ T-cell development | CW3 | N/A | MNoV persists in MHC I × β2M−/− mice for longer periods than in wild-type mice, but is eventually cleared; acute control of virus is also regulated by CD8+ T cells | [74,76] |

Interestingly, for persistent strains of MNoV, Ifnar1 does not control viral shedding or levels in the gut, but rather, regulates the ability of virus to spread to extraintestinal sites such as spleen [67,68]. Fecal shedding of these strains is instead limited by type III IFN signaling through Ifnlr1 [67,68]. Intraperitoneal administration of type III IFN cures persistent MNoV infection, even in the absence of adaptive immunity, suggesting this pathway as a potential therapeutic target for humans [67]. IFN-λ administration is an especially attractive approach, as it is a safe treatment for chronic hepatitis C virus [69]. Work in HEK293FT cells demonstrated that replication of transfected HNoV RNA is also sensitive to pretreatment with type I and III IFN, but unlike MNoV, blocking such responses does not affect viral replication [70]. This suggests that there may be alternate ways in which HNoV and MNoV engage IFN pathways [70].

After engagement of IFNs with their receptors, downstream transcription factors drive the production of a variety of antiviral factors. STAT1, which mediates IFN-stimulated gene transcription in type I, II, and III IFN signaling pathways, is critical for controlling viral loads, shedding, and lethality, as observed by infection of Stat1−/− mice with acute and persistent MNoV strains [8,9,66–68]. Transcription factor IRF1 is important for type II IFN-mediated control of MNoV in vitro in macrophages, and in vivo Irf1−/− mice exhibit enhanced lethality to MNoV challenge in the context of antibody-mediated IFNAR1 depletion [66]. Other factors downstream of IFN signaling implicated in MNoV control include proteins involved in macroautophagy. Mice lacking autophagy genes Atg5, Atg12, Atg7, or Atg16L1 in macrophages fail to control MNoV in vivo on an Ifnar1-deficient background, and autophagy-deficient macrophages fail to respond to type II IFN-directed control of acute MNoV replication in vitro [61]. However, the specific mechanisms by which autophagy may control MNoV remain to be elucidated. Interestingly, ATG16L1 is also important for preventing intestinal pathology induced by persistent MNoV infection [71]. This effect does not appear to occur through direct control of MNoV levels in the gut, as mice hypomorphic for Atg16L1 exhibit an inflammatory bowel disease (IBD)-like phenotype with viral infection [71]. Another study has shown that mice deficient in Il10, an anti-inflammatory cytokine, also exhibit intestinal pathology with persistent MNoV infection; in Il10−/− mice, altered MNoV levels may drive inflammation as MNoV is detectable in epithelial and lamina propria cells in the first two days after infection [72]. These findings suggest that although inflammation is important for controlling MNoV, unchecked inflammation induced by the virus may have pathologic consequences.

In addition to innate immunity, the adaptive immune system also controls MNoV (Table 2). For example, MNV-1 is not effectively cleared in mice lacking either set of, or both sets of, lymphocytes (e.g., B and T cells), that is, Rag1-, immunoglobulin heavy constant mu (Ighm/muMt)-, and MHC Class II-deficient mice [63,73–75]. Antibody responses are an important component of MNoV control and protection against repeat challenge, as Rag1−/− and muMt−/− mice fail to clear acute MNoV infection [73,74]. CD4+ and CD8+ T cells also play combinatorial roles in regulating MNoV; mice lacking CD4+ T cells present higher tissue titers but normal viral clearance, while mice lacking CD8+ T cells exhibit delayed viral clearance [63,74–76]. Infection with different MNoV strains elicits differential innate and adaptive immune responses. While adaptive immune responses are critical for the control of acute MNoV strains, persistent strains such as MNV-3 and MNV.CR6 fail to generate effective T-cell responses, which may contribute to viral persistence [75,76]. Acute MNoV strain MNV-1 stimulates greater type I and III IFN responses than persistent strain MNV.CR6, which may contribute to the development of enhanced adaptive immune responses and viral clearance [67]. However, a robust adaptive immune response alone is not sufficient for clearance of acute MNoV, as MNV-1 persists in mice lacking type I IFN signaling in DCs [62]. Extrapolating from MNoV findings, it is reasonable to assume that targeted IFN-related therapies might be potentially effective in HNoV clearance; however, the importance of differential adaptive immune responses to genetically diverse NoV strains may represent a challenge and will require further investigation.

Interactions of NoV with the Microbiota

The intestinal lumen houses a large number and variety of commensal microbes (bacteria, viruses, fungi, protozoa, and single-celled archaea species), collectively referred to as the microbiome. Pathogens infecting the intestine encounter these microbes, and NoV infections are influenced by those encounters with harmful or beneficial outcomes to the host. To date, a direct interaction of HNoV capsids with members of the microbiota is known for a few commensal (e.g., Enterobacter cloacae) and pathogenic (e.g., Clostridium difficile) bacterial species [77,78]. Interactions are mediated via HBGA-like carbohydrates expressed on the surface of these bacteria [78]. Both HNoVs and MNoVs have been reported to bind additional carbohydrate moieties [79–83], including sialic acid residues (Table 1), which are widely expressed on bacteria [84]. Thus, MNoVs likely interact with members of the microbiome as well, although specific interactions remain to be demonstrated.

Although not universally seen, both HNoV and MNoV can alter host gut microbial communities. This dysbiosis typically results in an enhanced bacterial Firmicutes-to-Bacteroidetes (F/B) ratio, an alteration also linked to liver fibrosis and obesity [85,86]. A subset (20%) of HNoV-infected individuals exhibited enhanced F/B ratios [87], while MNV-1 enhanced F/B ratios in C57BL/6 mice at Day 5 postinfection [88]. However, longitudinal analyses of both C57BL/6 (MNV-1, MNV.CR6) and Swiss Webster (MNV-1, MNV-4) mice failed to detect MNoV-induced dysbiosis of gastrointestinal bacteria at the phylum level [89]. A reduction in intestinal Lactobacillus strains occurred in MNV1-infected ICR mice, with a concurrent increase in Proteobacteria delta, mirroring findings from HNoV [89]. On the flip side, experimentally induced bacterial dysbiosis also alters MNoV infection. For instance, pretreatment of mice with an antibiotic cocktail including vancomycin, ampicillin, metronidazole, and neomycin (VNAM) reduces acute MNV-1 titers [4] and reduces or prevents infection by persistent MNoV strains MNV-3 and MNV.CR6, respectively [4,68]. Importantly, MNV.CR6 viral loads are restored with a fecal transplant from untreated to antibiotic-treated animals [68]. Although antibiotic treatment reduces intestinal MNoV titers, it is not an advisable treatment option for HNoV infections, given the overall beneficial impact of the microbiota on human health [90].

From the perspective of the cellular level, co-infection of macrophages with MNoV and various bacteria has been shown to reduce viral titers, likely stemming from bacterial triggering of innate immune responses [91–93]. However, by contrast, MNoV-induced inhibition of inflammatory cytokines appears to foster bacterial growth. These findings highlight the need to further study complex, trans-kingdom interactions and their effects on the host.

The Bermuda Triangle: Host, Microbiota, and NoV

Recent work has provided much insight into different host regulators of NoVs and clearly identified an important role for commensal microbes in NoV infection. However, these findings only begin to outline a still poorly defined triangle of interactions between the host, bacteria, and the virus.

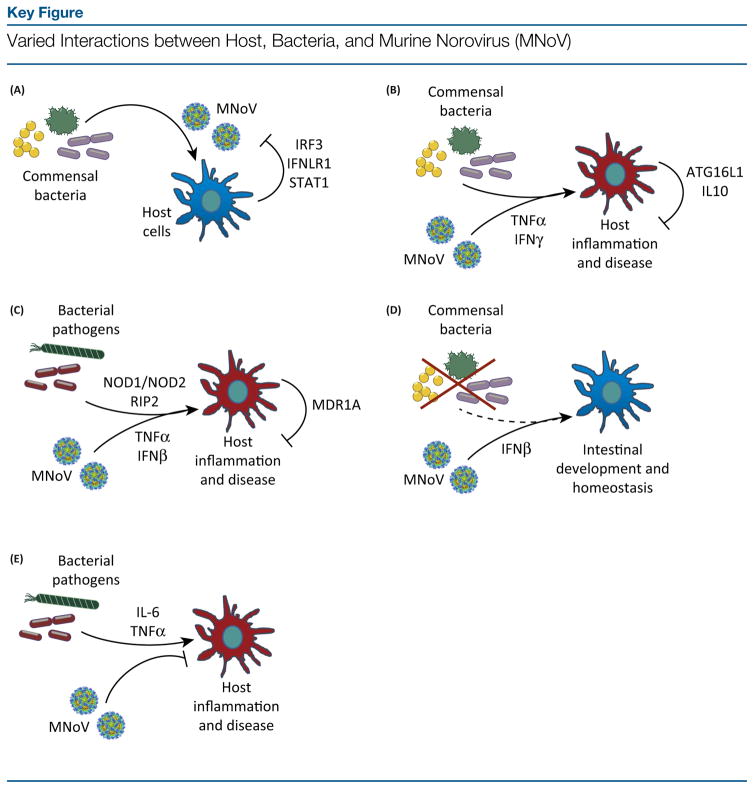

As outlined earlier, commensal bacteria in vivo serve a proviral function by facilitating successful viral infection [4,68]. This proviral function is countered by host antiviral factors in the IFN-λ pathway, including IRF3, IFNLR1, and STAT1, such that in the absence of these host molecules, persistent MNoV is less dependent on bacteria for infection (Figure 1A, Key Figure). The mechanism by which these host molecules alter the infectious potential of MNoV and its interaction with bacteria remains unclear. Consequently, these interactions will require a greater depth of understanding of all three arms of contact: MNoV interactions with commensal bacteria, interactions of bacteria with type III IFN signaling pathways, and the specific antiviral effects of type III IFN signaling on MNoV. In another interesting example of other enteric kingdoms of life interacting with MNoV in a proviral fashion, helminth infection with Trichinella spiralis leads to elevated intestinal MNV-1 loads due to STAT6-dependent changes in macrophage function [94]. These examples indicate that NoVs can benefit from the presence of other kingdoms of life normally present in the intestine, but that these beneficial effects may be mediated by the host.

Figure 1.

(A) Commensal bacteria facilitate persistent MNoV infection in a manner counteracted by innate immune factors IRF3, IFNLR1, and STAT1. (B) Commensal bacteria and MNoV are both needed to drive TNF-α and IFN-γ-mediated intestinal inflammation in mice lacking Atg16l1 or Il10. (C) MNoV exacerbates intestinal inflammation and lethality during pathogenic bacterial infection by potentiating inflammatory signals, including TNF-α and type I IFN, and host responses to bacteria. (D) In the absence of commensal bacteria, MNoV may replace protective functions of enteric microbes via type I IFN signaling. (E) In other contexts, MNoV can serve a protective role by decreasing the host inflammatory response to bacterial pathogens. IFN, interferon; IFNLR1, interferon λ receptor 1; IL, interleukin; IRF3, interferon regulatory transcription factor 3; NOD, nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain; STAT1, signal transducer and activator of transcription 1; TNF, tumor necrosis factor.

In other cases, the combination of MNoV and commensal bacteria may induce pathologic consequences to a susceptible host, such as persistent MNoV infection potentiating intestinal inflammation in particular genetic contexts. For example, Atg16L1−/− or Il10−/− mice, which serve as models for IBD, develop intestinal inflammation following MNoV infection [71,72]. Treatment of mice with antibiotics following MNoV viral infection, or the infection of germ-free mice, prevents injury-induced pathology. Consequently, in these IBD models, MNoV and commensal bacteria work synergistically to induce inflammation via inflammatory host factors [tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) and IFN-γ], and in opposition to other protective host factors (ATL16L1 and IL-10; Figure 1B).

MNoV can also act in concert with pathogenic bacteria to drive inflammation. In a mouse model of Helicobacter bilis-induced IBD, mice deficient in ATP-binding cassette transporter multidrug resistance gene 1a (Mdr1a) develop more severe colitis during co-infection with Gram-negative pathogen H. bilis and persistent MNoV, than with H. bilis infection alone [95] (Figure 1C). Host factor MDR1A, linked to human IBD and potentially important in intestinal barrier function, thus appears to suppress this co-infection phenotype [95]. The pathology-enhancing effect of MNoV in the context of IBD risk factor genes, however, was not observed in mice deficient for mothers against decapentaplegic homolog 3 (Smad3) and Il10 [96,97]. Acute MNoV infection also enhances lethality by systemic Escherichia coli, via type I IFNs and TNF-α, as well as via NOD1/NOD2- and RIP2-enhanced bacterial recognition on cell surfaces [98]. Thus, in addition to promoting potentially deleterious inflammatory effects from commensal bacteria under certain genetic contexts in mice, MNoV can also enhance inflammation, which is driven by known pathogenic bacteria such as E. coli. The host inflammatory response, while fighting these pathogens, is subverted by such multiple stimuli, turning on itself, and causing severe intestinal tissue damage to the host. Extrapolating to humans, the wide genetic diversity, differential co-infections, and unique commensal microbes harbored by each person may thus differentially predispose individuals to a range of symptoms and potential long-term effects from NoV-induced inflammation. The effects of inherent human variability during NoV infection thus represent an unexplored area of investigation.

In other contexts, MNoV infection can be beneficial for the host. Interestingly, in the absence of the microbiota, MNoV acts via type IIFN to restore abnormalities in intestinal tissues and immune function [99]. Wild-type mice treated with a VNAM antibiotics cocktail exhibited enhanced dextran sodium sulfate-induced intestinal injury and morbidity, which could be rescued by MNoV infection, but not in an Ifnar1−/− genetic background. In addition, MNoV infection of VNAM-treated mice significantly reduced weight loss, diarrhea, and intestinal histopathology following infection with Citrobacter rodentium, a model for enteropathogenic E. coli [99]. Thus, MNoV contributed in protecting mice against injury, presumably by replacing IFN signaling functions of commensal bacteria [99] (Figure 1D). Another study found that in ampicillin-treated mice, MNoV infection partially restored antibacterial defenses against vancomycin-resistant Enterococcus faecium, again supporting a role for MNoV in replacing the commensal micro-biota’s role in immune signaling [100]. While these studies were undertaken in the absence of the microbiota, MNoV infection of conventionally housed mice has also been found to increase mouse survival following intranasal bacterial infection with Pseudomonas aeruginosa [101]. Indeed, MNoV infection was associated with reduced P. aeruginosa-induced neutrophil infiltration in the lung and decreased proinflammatory cytokine (IL-6 and TNF-α) production, thus resulting in protected alveolar capillary barrier permeability and reduced acute lung injury [101] (Figure 1E). MNoV can thus confer protection against a variety of different pathogenic bacteria by stimulating effective immunological responses; whether these findings apply broadly to all mucosal pathogens or are specific to particular pathogen subsets remains to be determined.

The intestinal environment with its rich mixture of different commensal and pathogenic microbes, host cells, microbial products, and cytokines is a complex locale which we are only beginning to understand. Systematic interrogation of the individual connections between these different components will start to shed light on the context-dependent effects of these factors on each other. Ultimately, studies will need to consider the translatability of these findings to HNoV infection as appropriate models are being developed.

Concluding Remarks

NoV infections cause a significant public health burden worldwide, but no directed treatment or prevention strategies are currently approved. Historically, this has been in large part due to the many technical hurdles that scientists have faced working with NoV. However, over the last two decades, NoV researchers have made significant leaps forward, increasing our general understanding of NoV biology (Box 1). These developments were aided in part by the utility of the MNoV model. Recent advances have included the identification of previously unknown host regulators, and the ascription of a novel function for the microbiota in modulating NoV infection at both cellular and host levels. Such information is invaluable for the development of vaccines and antivirals. Furthermore, NoV-infected cell types are being identified, which shifts the paradigm away from an exclusively enterotropic virus to that of a virus exhibiting a broader tropism also encompassing myeloid cell lineages [8,40]. The implications of this expanded cellular tropism for pathogenesis and vaccine responses are only just beginning to be explored. In addition, determining the translatability of findings from MNoV to HNoV will require gaining a better appreciation of the aspects by which HNoV infection and disease are best modeled with current experimental strategies. In addition, the development of improved models will undoubtedly be a focus of investigation over the decades to come (see Outstanding Questions). Thus, as future discoveries reveal further insights into NoVs, these are expected to have a significant positive impact on public health, hopefully reducing the associated personal and economic burden of this infectious disease.

Box 1. The Clinician’s Corner.

Norovirus is the leading cause of epidemic gastroenteritis, and can persist indefinitely in immunocompromised hosts. This may be the case for patients with genetic immunodeficiencies, or those at risk of infection post-transplantation.

In addition to causing acute gastroenteritis, norovirus infection has been suggested as a possible trigger for other enteric diseases, including postinfectious irritable bowel syndrome, necrotizing enterocolitis in infants, and exacerbation of inflammatory bowel disease. Additional evidence is needed to bolster these connections, and the mechanisms by which norovirus might cause long-term disease remain unclear.

The commensal bacteria of the gut have been shown to help facilitate norovirus infection. Because different individuals harbor different commensal bacterial communities, it is possible that interindividual variation in gut bacteria could contribute to differing severity of norovirus infection. There is no evidence, however, that antibiotic treatment would be either helpful or therapeutic for an ongoing norovirus infection.

Both the innate and adaptive immune systems have been shown to be important for norovirus regulation in mouse models, suggesting that future targeting of the innate immune system may be important therapeutically for patients with chronic norovirus infection.

Outstanding Questions.

Which are the major cell types infected during norovirus (NoV) infection in immunocompetent hosts?

How does the tropism for immune cells influence immunity against NoVs?

Which aspects of human NoV biology are best modeled by murine NoV? Which aspects require other existing or yet to be developed models?

What are the physiological functions of histo-blood group antigens, CD300LF, and CD300LD during NoV infection?

How does the wide genetic diversity of commensal microbes in individuals, in addition to differential co-infections with different pathogens, influence NoV disease outcomes?

How will microbial/NoV interactions affect vaccine development?

Can interferon-λ or other host regulators be contemplated as a putative treatment for persistent NoV infections? If so, how?

Trends.

Murine norovirus provides a practical model to study of norovirus infections and pathogenesis.

Murine and human noroviruses share a tropism for immune cells and intestinal epithelial cells.

Norovirus infection is regulated by multiple host genes, including viral entry factors, innate immune mediators, and components of the adaptive immune system.

The commensal bacteria of the gastrointestinal microbiome can modulate norovirus infection.

Recent findings indicate that norovirus and commensal bacteria stimulate overlapping host immune pathways, and furthermore, that certain bacteria are required to mediate some of the pathologic effects of norovirus infection.

Host and microbial effects on norovirus may function in complex combinations to regulate viral infection and pathogenesis.

Acknowledgments

M.T.B. was supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH) training grant T32CA009547. Work in the laboratory of C.E.W. was supported by NIH grants AI102106, AI080611, and AI103961. H.T. was supported in part by a University of Michigan Rackham Merit fellowship and NIH training grants T32AI007413 and T32DK094775.

Glossary

- Caliciviridae (caliciviruses)

family of positive-sense, nonsegmented, single-stranded RNA viruses including norovirus.

- CD300LF and CD300LD

inhibitory receptors of the immunoglobulin superfamily, known to be expressed on myeloid cells, and recently identified as viral receptors for murine norovirus.

- CD68+ or DC-SIGN+ phagocytes

CD68 is a surface marker for macrophages, and DC-SIGN (or CD209) is a marker for dendritic cells, both found in the lamina propria of the human intestine.

- Crohn’s disease

a type of chronic inflammatory bowel disease that may affect any part of the gastrointestinal tract, characterized by symptoms including abdominal pain, diarrhea, fever, and weight loss.

- Dextran sodium sulfate

a compound used to induce colitis in mouse models; it interferes with intestinal barrier function and stimulates inflammation, thereby mimicking clinical features of inflammatory bowel diseases.

- Fucosyltransferase 2

enzyme that transfers fucose sugars, and governs the molecular basis of the histo-blood group antigens, which are surface markers for red blood cells.

- Macroautophagy

a process by which cells degrade and recycle intracellular contents.

- Microfold (M) cells

a subtype of intestinal epithelial cell, found in gut- and mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue, which facilitates transport of microbes from the gut lumen to the lamina propria.

- Necrotizing enterocolitis

a medical condition primarily affecting premature infants, often leading to death, where portions of the bowel undergo necrosis.

- Pattern recognition receptors

receptors that recognize conserved features of pathogens and initiate signaling cascades resulting in innate immune responses. They are divided into four families, including Toll-like receptors, nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain-like receptors, and RIG-I-like receptors.

- T-helper type 1 (Th1) and Th2

T helper (Th) cells are T cells that facilitate B-cell antibody class switching and activation of cytotoxic T cells. Th1 cells are important for control of intracellular bacteria and protozoa and classically produce effector cytokine interferon-γ (IFN-γ type II IFN). Th2 cells are important for the control of extracellular parasites such as helminths, and are associated with cytokines interleukin-4 (IL-4), IL-5, and IL-13.

- Type I, II, and III interferons (IFNs)

signaling cytokines produced by host cells in response to exposure to pathogens. Type I (including IFN-α and IFN-β) and type III IFNs (such as IFN-λ) are classically triggered with viral infection, with type III IFN being more associated with mucosal infections. Type II IFN (or IFN-γ) is usually associated with bacterial infections.

References

- 1.Hall AJ, et al. Norovirus disease in the United States. Emerg Infect Dis. 2013;19:1198–1205. doi: 10.3201/eid1908.130465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bartsch SM, et al. Global economic burden of norovirus gastroenteritis. PLoS ONE. 2016;11:e0151219. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0151219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Taube S, et al. A mouse model for human norovirus. mBio. 2013;4:e00450–e513. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00450-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jones MK, et al. Enteric bacteria promote human and mouse norovirus infection of B cells. Science. 2014;346:755–759. doi: 10.1126/science.1257147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ettayebi K, et al. Replication of human noroviruses in stem cell-derived human enteroids. Science. 2016;353:1387–1393. doi: 10.1126/science.aaf5211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wobus CE, et al. Animal models of norovirus infection. In: Svensson L, et al., editors. Viral Gastroenteritis: Molecular Epidemiology and Pathogenesis. 1. Academic Press; 2016. pp. 397–422. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wobus CE, et al. Murine norovirus: a model system to study norovirus biology and pathogenesis. J Virol. 2006;80:5104–5112. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02346-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wobus CE, et al. Replication of norovirus in cell culture reveals a tropism for dendritic cells and macrophages. PLoS Biol. 2004;2:e432. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0020432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Karst SM, et al. STAT1-dependent innate immunity to a Norwalk-like virus. Science. 2003;299:1575–1578. doi: 10.1126/science.1077905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Green KY. Caliciviridae: the noroviruses. In: Knipe DM, editor. Fields Virology. 6. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2013. pp. 582–608. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vinje J. Advances in laboratory methods for detection and typing of norovirus. J Clin Microbiol. 2015;53:373–381. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01535-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McFadden N, et al. Norovirus regulation of the innate immune response and apoptosis occurs via the product of the alternative open reading frame 4. PLoS Pathog. 2011;7:e1002413. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kirby AE, et al. Vomiting as a symptom and transmission risk in norovirus illness: evidence from human challenge studies. PLoS ONE. 2016;11:e0143759. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0143759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jones RM, Brosseau LM. Aerosol transmission of infectious disease. J Occup Environ Med. 2015;57:501–508. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0000000000000448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Teunis PF, et al. Norwalk virus: how infectious is it? J Med Virol. 2008;80:1468–1476. doi: 10.1002/jmv.21237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Atmar RL, et al. Determination of the 50% human infectious dose for Norwalk virus. J Infect Dis. 2014;209:1016–1022. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jit620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Newman KL, et al. Norovirus in symptomatic and asymptomatic individuals: cytokines and viral shedding. Clin Exp Immunol. 2016;184:347–357. doi: 10.1111/cei.12772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Colas de la Noue A, et al. Absolute humidity influences the seasonal persistence and infectivity of human norovirus. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2014;80:7196–7205. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01871-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tung G, et al. Efficacy of commonly used disinfectants for inactivation of human noroviruses and their surrogates. J Food Prot. 2013;76:1210–1217. doi: 10.4315/0362-028X.JFP-12-532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kaufman SS, et al. Treatment of norovirus infections: moving antivirals from the bench to the bedside. Antiviral Res. 2014;105:80–91. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2014.02.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee RM, et al. Incubation periods of viral gastroenteritis: a systematic review. BMC Infect Dis. 2013;13:446. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-13-446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Teunis PF, et al. Shedding of norovirus in symptomatic and asymptomatic infections. Epidemiol Infect. 2015;143:1710–1717. doi: 10.1017/S095026881400274X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Echenique IA, et al. Prolonged norovirus infection after pancreas transplantation: a case report and review of chronic norovirus. Transpl Infect Dis. 2016;18:98–104. doi: 10.1111/tid.12472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Karst SM, et al. The molecular pathology of noroviruses. J Pathol. 2015;235:206–216. doi: 10.1002/path.4463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bonani M, et al. Chronic norovirus infection as a risk factor for secondary lactose maldigestion in renal transplant recipients: a prospective parallel cohort pilot study. Transplantation. 2016 doi: 10.1097/TP.0000000000001376. Published online August 1, 2016. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/TP.0000000000001376. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 26.Futagami S, et al. Systematic review with meta-analysis: post-infectious functional dyspepsia. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2015;41:177–188. doi: 10.1111/apt.13006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Glass RI, et al. Norovirus gastroenteritis. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:1776–1785. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0804575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pelizzo G, et al. Isolated colon ischemia with norovirus infection in preterm babies: a case series. J Med Case Rep. 2013;7:108. doi: 10.1186/1752-1947-7-108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hubbard VM, Cadwell K. Viruses, autophagy genes, and Crohn’s disease. Viruses. 2011;3:1281–1311. doi: 10.3390/v3071281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Karst SM, et al. Advances in norovirus biology. Cell Host Microbe. 2014;15:668–680. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2014.05.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hsu CC, et al. Development of a microsphere-based serologic multiplexed fluorescent immunoassay and a reverse transcriptase PCR assay to detect murine norovirus 1 infection in mice. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 2005;12:1145–1151. doi: 10.1128/CDLI.12.10.1145-1151.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kim JR, et al. Prevalence of murine norovirus infection in Korean laboratory animal facilities. J Vet Med Sci. 2011;73:687–691. doi: 10.1292/jvms.10-0226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McInnes EF, et al. Prevalence of viral, bacterial and parasitological diseases in rats and mice used in research environments in Australasia over a 5-y period. Lab Anim (NY) 2011;40:341–350. doi: 10.1038/laban1111-341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Karst SM, Tibbetts SA. Recent advances in understanding norovirus pathogenesis. J Med Virol. 2016;88:1837–1843. doi: 10.1002/jmv.24559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Elftman MD, et al. Multiple effects of dendritic cell depletion on murine norovirus infection. J Gen Virol. 2013;94:1761–1768. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.052134-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Karst SM, Wobus CE. A working model of how noroviruses infect the intestine. PLoS Pathog. 2015;11:e1004626. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gonzalez-Hernandez MB, et al. Efficient norovirus and reovirus replication in the mouse intestine requires microfold (M) cells. J Virol. 2014;88:6934–6943. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00204-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gonzalez-Hernandez MB, et al. Murine norovirus transcytosis across an in vitro polarized murine intestinal epithelial monolayer is mediated by M-like cells. J Virol. 2013;87:12685–12693. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02378-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Brown JR, et al. Norovirus infections occur in B-cell-deficient patients. Clin Infect Dis. 2016;62:1136–1138. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciw060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Karandikar UC, et al. Detection of human norovirus in intestinal biopsies from immunocompromised transplant patients. J Gen Virol. 2016;97:2291–2300. doi: 10.1099/jgv.0.000545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mumphrey SM, et al. Murine norovirus 1 infection is associated with histopathological changes in immunocompetent hosts, but clinical disease is prevented by STAT1-dependent interferon responses. J Virol. 2007;81:3251–3263. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02096-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ward JM, et al. Pathology of immunodeficient mice with naturally occurring murine norovirus infection. Toxicol Pathol. 2006;34:708–715. doi: 10.1080/01926230600918876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Guix S, et al. Norwalk virus RNA is infectious in mammalian cells. J Virol. 2007;81:12238–12248. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01489-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Orchard RC, et al. Discovery of a proteinaceous cellular receptor for a norovirus. Science. 2016;353:933–936. doi: 10.1126/science.aaf1220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Haga K, et al. Functional receptor molecules CD300lf and CD300ld within the CD300 family enable murine noroviruses to infect cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2016;113:E6248–E6255. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1605575113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Borrego F. The CD300 molecules: an emerging family of regulators of the immune system. Blood. 2013;121:1951–1960. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-09-435057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tian L, et al. Enhanced efferocytosis by dendritic cells underlies memory T-cell expansion and susceptibility to autoimmune disease in CD300f-deficient mice. Cell Death Differ. 2016;23:1086–1096. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2015.161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Albino D, et al. ESE3/EHF controls epithelial cell differentiation and its loss leads to prostate tumors with mesenchymal and stem-like features. Cancer Res. 2012;72:2889–2900. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-0212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Currier RL, et al. Innate susceptibility to norovirus infections influenced by FUT2 genotype in a United States pediatric population. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;60:1631–1638. doi: 10.1093/cid/civ165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lindesmith L, et al. Human susceptibility and resistance to Norwalk virus infection. Nat Med. 2003;9:548–553. doi: 10.1038/nm860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tan M, Jiang X. Histo-blood group antigens: a common niche for norovirus and rotavirus. Expert Rev Mol Med. 2014;16:e5. doi: 10.1017/erm.2014.2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sestak K. Role of histo-blood group antigens in primate enteric calicivirus infections. World J Virol. 2014;3:18–21. doi: 10.5501/wjv.v3.i3.18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kambhampati A, et al. Host genetic susceptibility to enteric viruses: a systematic review and metaanalysis. Clin Infect Dis. 2016;62:11–18. doi: 10.1093/cid/civ873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Atmar RL, et al. Norovirus vaccine against experimental human Norwalk virus illness. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:2178–2187. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1101245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ramani S, et al. Mucosal and cellular immune responses to Norwalk virus. J Infect Dis. 2015;212:397–405. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiv053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lindesmith LC, et al. Broad blockade antibody responses in human volunteers after immunization with a multivalent norovirus VLP candidate vaccine: immunological analyses from a phase I clinical trial. PLoS Med. 2015;12:e1001807. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Chen Z, et al. Development of Norwalk virus-specific monoclonal antibodies with therapeutic potential for the treatment of Norwalk virus gastroenteritis. J Virol. 2013;87:9547–9557. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01376-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Green KY. Norovirus infection in immunocompromised hosts. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2014;20:717–723. doi: 10.1111/1469-0691.12761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Riddle MS, Walker RI. Status of vaccine research and development for norovirus. Vaccine. 2016;34:2895–2899. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2016.03.077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Thackray LB, et al. Critical role for interferon regulatory factor 3 (IRF-3) and IRF-7 in type I interferon-mediated control of murine norovirus replication. J Virol. 2012;86:13515–13523. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01824-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hwang S, et al. Nondegradative role of Atg5-Atg12/Atg16L1 autophagy protein complex in antiviral activity of interferon gamma. Cell Host Microbe. 2012;11:397–409. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2012.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Nice TJ, et al. Type I interferon receptor deficiency in dendritic cells facilitates systemic murine norovirus persistence despite enhanced adaptive immunity. PLoS Pathog. 2016;12:e1005684. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1005684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Zhu S, et al. Identification of immune and viral correlates of norovirus protective immunity through comparative study of intra-cluster norovirus strains. PLoS Pathog. 2013;9:e1003592. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.McCartney SA, et al. MDA-5 recognition of a murine norovirus. PLoS Pathog. 2008;4:e1000108. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wang P, et al. Nlrp6 regulates intestinal antiviral innate immunity. Science. 2015;350:826–830. doi: 10.1126/science.aab3145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Maloney NS, et al. Essential cell-autonomous role for interferon (FN) regulatory factor 1 in IFN-gamma-mediated inhibition of norovirus replication in macrophages. J Virol. 2012;86:12655–12664. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01564-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Nice TJ, et al. Interferon-lambda cures persistent murine norovirus infection in the absence of adaptive immunity. Science. 2015;347:269–273. doi: 10.1126/science.1258100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Baldridge MT, et al. Commensal microbes and interferon-lambda determine persistence of enteric murine norovirus infection. Science. 2015;347:266–269. doi: 10.1126/science.1258025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Muir AJ, et al. A randomized phase 2b study of peginterferon lambda-1a for the treatment of chronic HCV infection. J Hepatol. 2014;61:1238–1246. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2014.07.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Qu L, et al. Replication of human norovirus RNA in mammalian cells reveals lack of interferon response. J Virol. 2016;90:8906–8923. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01425-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Cadwell K, et al. Virus-plus-susceptibility gene interaction determines Crohn’s disease gene Atg16L1 phenotypes in intestine. Cell. 2010;141:1135–1145. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.05.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Basic M, et al. Norovirus triggered microbiota-driven mucosal inflammation in interleukin 10-deficient mice. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2014;20:431–443. doi: 10.1097/01.MIB.0000441346.86827.ed. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Chachu KA, et al. Antibody is critical for the clearance of murine norovirus infection. J Virol. 2008;82:6610–6617. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00141-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Chachu KA, et al. Immune mechanisms responsible for vaccination against and clearance of mucosal and lymphatic norovirus infection. PLoS Pathog. 2008;4:e1000236. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Tomov VT, et al. Persistent enteric murine norovirus infection is associated with functionally suboptimal virus-specific CD8 T cell responses. J Virol. 2013;87:7015–7031. doi: 10.1128/JVI.03389-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Zhu S, et al. Norovirus antagonism of B-cell antigen presentation results in impaired control of acute infection. Mucosal Immunol. 2016;9:1559–1570. doi: 10.1038/mi.2016.15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Li D, et al. Binding to histo-blood group antigen-expressing bacteria protects human norovirus from acute heat stress. Front Microbiol. 2015;6:659. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2015.00659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Miura T, et al. Histo-blood group antigen-like substances of human enteric bacteria as specific adsorbents for human noroviruses. J Virol. 2013;87:9441–9451. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01060-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Taube S, et al. Ganglioside-linked terminal sialic acid moieties on murine macrophages function as attachment receptors for murine noroviruses. J Virol. 2009;83:4092–4101. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02245-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Taube S, et al. Murine noroviruses bind glycolipid and glycoprotein attachment receptors in a strain-dependent manner. J Virol. 2012;86:5584–5593. doi: 10.1128/JVI.06854-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Bally M, et al. Norovirus GII. 4 virus-like particles recognize galactosylceramides in domains of planar supported lipid bilayers. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2012;51:12020–12024. doi: 10.1002/anie.201205972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Rydell GE, et al. Human noroviruses recognize sialyl Lewis x neoglycoprotein. Glycobiology. 2009;19:309–320. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cwn139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Tamura M, et al. Genogroup II noroviruses efficiently bind to heparan sulfate proteoglycan associated with the cellular membrane. J Virol. 2004;78:3817–3826. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.8.3817-3826.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Almagro-Moreno S, Boyd EF. Bacterial catabolism of nonulosonic (sialic) acid and fitness in the gut. Gut Microbes. 2010;1:45–50. doi: 10.4161/gmic.1.1.10386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.DeMinicis S, et al. Dysbiosis contributes to fibrogenesis in the course of chronic liver injury in mice. Hepatology. 2014;59:1738–1749. doi: 10.1002/hep.26695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Compare D, et al. The gut bacteria-driven obesity development. Dig Dis. 2016;34:221–229. doi: 10.1159/000443356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Nelson AM, et al. Disruption of the human gut microbiota following norovirus infection. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e48224. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0048224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Hickman D, et al. The effect of malnutrition on norovirus infection. mBio. 2014;5:e01032–e1113. doi: 10.1128/mBio.01032-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Nelson AM, et al. Murine norovirus infection does not cause major disruptions in the murine intestinal microbiota. Microbiome. 2013;1:7. doi: 10.1186/2049-2618-1-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Pettigrew MM, et al. The human microbiota: novel targets for hospital-acquired infections and antibiotic resistance. Ann Epidemiol. 2016;26:342–347. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2016.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Agnihothram SS, et al. Infection of murine macrophages by Salmonella enterica serovar Heidelberg blocks murine norovirus infectivity and virus-induced apoptosis. PLoS ONE. 2015;10:e0144911. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0144911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Li D, et al. Anti-viral effect of Bifidobacterium adolescentis against noroviruses. Front Microbiol. 2016;7:864. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2016.00864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Lee H, Ko G. Antiviral effect of vitamin A on norovirus infection via modulation of the gut microbiome. Sci Rep. 2016;6:25835. doi: 10.1038/srep25835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Osborne LC, et al. Coinfection. Virus-helminth coinfection reveals a microbiota-independent mechanism of immuno-modulation. Science. 2014;345:578–582. doi: 10.1126/science.1256942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Lencioni KC, et al. Murine norovirus: an intercurrent variable in a mouse model of bacteria-induced inflammatory bowel disease. Comp Med. 2008;58:522–533. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Lencioni KC, et al. Lack of effect of murine norovirus infection on a mouse model of bacteria-induced colon cancer. Comp Med. 2011;61:219–226. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Hsu CC, et al. Infection with murine norovirus 4 does not alter Helicobacter-induced inflammatory bowel disease in Il10−/−mice. Comp Med. 2014;64:256–263. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Kim YG, et al. Viral infection augments Nod1/2 signaling to potentiate lethality associated with secondary bacterial infections. Cell Host Microbe. 2011;9:496–507. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2011.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Kernbauer E, et al. An enteric virus can replace the beneficial function of commensal bacteria. Nature. 2014;516:94–98. doi: 10.1038/nature13960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Abt MC, et al. TLR-7 activation enhances IL-22-mediated colonization resistance against vancomycin-resistant enterococcus. Sci Transl Med. 2016;8:327ra25. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aad6663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Thepaut M, et al. Protective role of murine norovirus against Pseudomonas aeruginosa acute pneumonia. Vet Res. 2015;46:91. doi: 10.1186/s13567-015-0239-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]