Abstract

Background

Tobacco companies use colour on cigarette packaging and labelling to communicate brand imagery, diminish health concerns, and as a replacement for prohibited descriptive words (‘light’ and ‘mild’) to make misleading claims about reduced risks.

Methods

We analysed previously secret tobacco industry documents to identify additional ways in which cigarette companies tested and manipulated pack colours to affect consumers’ perceptions of the cigarettes’ flavour and strength.

Results

Cigarette companies’ approach to package design is based on ‘sensation transference’ in which consumers transfer sensations they derive from the packaging to the product itself. Companies manipulate consumers’ perceptions of the taste and strength of cigarettes by changing the colour of the packaging. For example, even without changes to the tobacco blends, flavourings or additives, consumers perceive the taste of cigarettes in packages with red and darker colours to be fuller flavoured and stronger, and cigarettes in packs with more white and lighter colours are perceived to taste lighter and be less harmful.

Conclusions

Companies use pack colours to manipulate consumers’ perceptions of the taste, strength and health impacts of the cigarettes inside the packs, thereby altering their characteristics and effectively creating new products. In countries that do not require standardised packaging, regulators should consider colour equivalently to other changes in cigarette characteristics (eg, physical characteristics, ingredients, additives and flavourings) when making determinations about whether or not to permit new products on the market.

INTRODUCTION

Tobacco companies have long understood that pack colours influence consumers’ purchasing decisions. On reviewing previously secret internal industry documents available at the time, Wakefield et al demonstrated that tobacco companies use pack design to communicate brand imagery and influence consumers’ perceptions of taste, strength and harm as an important element in their overall marketing strategies.1 Subsequent studies showed that companies use pack colours to play an important role in communicating brand imagery and product characteristics,2 to target specific groups3–6 and to diminish health concerns,1,7 sometimes developing pack and promotional concepts before product development.8 Cigarettes from packs with brand descriptors including ‘light’, ‘low’, ‘mild’, ‘smooth’, ‘silver’ and ‘gold’ are perceived as having lower health risks.9–14 Before descriptors such as ‘light’ and ‘mild’ were prohibited,15 the companies associated them with specific package colours to make the same misleading claims about reduced risks without using words.10,13,14,16–24 To address this practice, the WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC) commits signatories to implement national laws that ensure that tobacco product packaging and labelling do not promote tobacco products by any means that are false or misleading25 and recommends standardised packaging.26 Companies understand that pack structures, shapes, openings, descriptors and colours communicate brand imagery and influence perceptions of product quality, strength and taste.27

In 1954, psychologist and marketing pioneer Cheskin28 described using scientific testing to analyse the impact of colour on consumers’ purchasing choices and explained how colour could be used to design effective packaging. Tobacco companies followed the work of Cheskin and his Color Research Institute (CRI) on consumers’ emotional responses to packages and the impact that package colour had on their perceptions of how the product inside the package tasted. Cheskin revealed that on an unconscious level ‘people transferred sensations of color and design to sensations of taste’, which he called ‘sensation transference’.28 He demonstrated that consumers transfer sensations or impressions they have about packaging to the product itself; indeed, consumers do not distinguish between the package and the product.28

The existing literature focuses on how colour is used in package design to ‘communicate information’ such as product identification and brand imagery (eg, the red chevron shouts ‘Marlboro’), targeted groups (eg, pastels say ‘women’s cigarettes’) or reduced health risks (eg, silver whispers ‘ultra-light’ cigarettes). Since Wakefield’s 2002 study,1 more than 6 million documents have been added to the Truth Tobacco Industry Documents library that match her search terms, and more than 200 000 more documents have been added using narrower search terms that focus on taste. Building on Wakefield’s work, we show how the industry relied on Cheskin’s work to use pack designs and colours not only to communicate marketing information, but also to influence consumers’ experiences of smoking the cigarettes themselves by altering their perceptions of the cigarettes’ taste. This understanding distinguishes between using pack colours to communicate information about a brand or sub-brand that might be associated with a particular taste versus using pack colours to manipulate consumer perceptions of the cigarette’s taste.

As of March 2016, 180 countries had become Parties to the WHO FCTC, which calls for tobacco product regulation (including packaging), and the USA enacted the Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act (FSPTCA). Since pack colours alter smokers’ experience of the cigarettes’ taste and strength, one can argue that pack colour changes are tantamount to product changes, which could have implications for laws regulating the introduction of new tobacco products.

METHODS

Between January 2013 and December 2014, we analysed previously secret tobacco company documents available at the UCSF Truth Tobacco Documents Library (TTDL, https://industrydocuments.library.ucsf.edu/tobacco/) on the industry’s internal research on how cigarette package colours influence consumers’ perceptions of the cigarettes inside the package, in particular the cigarettes’ taste. We used standard snowball search techniques,29 beginning with the search terms ‘(flavor OR flavour) AND (color OR colour)’ (106 169 documents), ‘taste AND (color OR colour)’ (98 460), ‘taste perception AND pack*’ (3384), ‘(color OR colour) and “taste perception” and pack’ (1110), ‘(color OR colour) code’ (3654), ‘sensory science’ (181) and ‘sensation transference’ (11); additional documents were found by reviewing adjacent documents (Bates numbers). We narrowed our initial searches to documents detailing the companies’ market research and scientific literature reviews concerning the use of colour in package design to influence consumers’ perceptions of the cigarettes’ taste and other sensory experiences. We reviewed ~400 documents; this paper is based on 54 documents showing what the tobacco companies researched and understood about pack colours’ influence on consumers’ perceptions of cigarettes’ taste.

RESULTS

Sensation transference: the package is the product

Since the 1950s, tobacco companies conducted extensive social science and psychology research to better understand how package colour affects consumers’ perceptions of the cigarettes inside the packs.28,30–35 Companies including Philip Morris (PM),36 RJ Reynolds (RJR),33,37 Lorillard,38,39 Brown and Williamson (B&W)40 and British American Tobacco (BAT)41 incorporated Cheskin’s theory of ‘sensation transference’28 in their market research and package design testing and worked to design cigarette packages that would affect their customers’ sensations and perceptions of the taste of the cigarettes inside the packs.

PM hired Cheskin and CRI to help redesign its Marlboro pack in the 1950s.42,43 CRI conducted psychological studies on how colour could inform pack design, resulting in the new Marlboro flip-top pack with its distinctive chevron design, red colour and brand name lettering.42 PM spent 7 years engaged in ‘an extraordinary degree of calculation, thoughtful planning and scientific testing’ on the new Marlboro packaging, refuting the industry cliché that ‘no one smokes the package’.44 By adding red to the mostly white package, PM converted Marlboro from a ‘woman’s cigarette’ to a new brand that was ‘high quality’ and ‘full flavor’,42,43 with Marlboro’s new ‘macho’ image further developed by Leo Burnett’s ‘Marlboro Man’ advertising campaign.45

RJR’s ‘Brand Marketing Training Module’ emphasises how package changes are tantamount to changes in the physical product itself: “Your primary concern is consumers’ reaction to and perceptions of the product inside the package, not their judgment as to which is the most attractive package [emphasis added].”37 Moreover, “a package is much more than a container; it … generates expectations and people generally get what they expect. In repeated tests, consumers will declare one product superior to another although only the packages or labels [not the cigarettes] are different [emphasis added].”37 The manual states that designing an effective new package is important not only because it could be “the major factor in a new marketing strategy by significantly improving consumer perceptions of the total product,” but also because “a package change can create a ‘new’ product” by giving customers the existing product in a new form (emphasis added).37

Company research demonstrating that altering pack colour changes perceptions of cigarettes’ characteristics

Building on Cheskin’s work and sensation transference, as early as the 1950s the companies used ocular measurements (eye movements),30 tachistoscopic testing (consumers’ recall time after flashing a picture of the package)46 and repertory grid techniques (colour’s influence on consumers’ assessment of the products’ sensory properties)41 alongside traditional market surveys to determine how cigarette pack colours not only enhanced the visual prominence of their brands and supported brand imagery, but also influenced consumers’ experience of smoking the cigarettes. Table 1 compiles internal industry research documents focusing on the impact that cigarette pack colours have on particular perceptions of the taste of the cigarettes inside the pack. These documents generally show that consumer perceptions of full, rich or strong flavoured cigarettes are associated with red and dark colours such as brown or black, whereas consumer perceptions of mild, smooth and mellow flavours are associated with light colours such as light blue or silver. Menthol and ‘cool’ or ‘fresh’ are universally associated with green, and low strength is associated with white or very light shades. Even subtle changes in colour tones, such as using a lighter beige background, can have these effects.

Table 1.

Summary of industry research on effects of package colour on smoker perceptions of the flavour and taste of cigarettes in the package

| Consumer perceptions | Colour | Company | Year |

|---|---|---|---|

| Full flavour | Red | PM | 1950s43 |

| RJR | 200147 | ||

| RJR | 199148 | ||

| RJR | 198749 | ||

| BAT | 198650 | ||

| RJR | 198451 | ||

| RJR | 198452 | ||

| RJR | 1980s37 | ||

| Brown | PM | 196531 | |

| Rich tobacco taste, flavourful | Red | PM | 199953 |

| PM | 198154 | ||

| RJR | 198451 | ||

| RJR | 197955 | ||

| Blue | B&W | 197856–58 | |

| B&W | 197740 | ||

| PM | 199959 | ||

| PM | 199860–62 | ||

| Beige | RJR | 198763 | |

| RJR | 198664 | ||

| RJR | 198665 | ||

| RJR | 198466 | ||

| B&W | 199467 | ||

| Satisfying | Red | PM | 199953 |

| RJR | 198451 | ||

| Blue | B&W | 197858 | |

| Beige | RJR | 198763 | |

| RJR | 198664 | ||

| RJR | 198665 | ||

| Strong taste | Black | RJR | 198451 |

| Brown | RJR | 197968 | |

| B&W | 199467 | ||

| Red | PM | 198154 | |

| RJR | 198749 | ||

| RJR | 198452 | ||

| RJR | 197968 | ||

| Tastes like Marlboro | Red | RJR | 198452 |

| Enhances flavour | Red | RJR | 200147 |

| Green | RJR | 200147 | |

| Good aftertaste | Silver | B&W | 197858 |

| Smooth | Blue | B&W | 197858 |

| Artificial taste | Gray | RJR | 198664 |

| Low strength | White, lighter shades | RJR | 197968 |

| Mild | Blue | PM | 199959 |

| PM | 199860–62 | ||

| PM | 198154 | ||

| Silver | B&W | 197858 | |

| Gray | RJR | 198664 | |

| Mellow | Blue | B&W | 197858 |

| Menthol | Green | RJR | 200147 |

| RJR | 199148 | ||

| RJR | 198749 | ||

| RJR | 198769 | ||

| BAT | 198650 | ||

| RJR | 198451 | ||

| RJR | 1980s37 | ||

| Cool | Green | RJR | 200147 |

| RJR | 198749 | ||

| Fresh | Green | RJR | 200147 |

| Silver | B&W | 197858 |

Taste and strength

Particular pack colours led consumers to perceive the cigarettes had what companies considered ‘good’ and ‘bad’ attributes, including full or enhanced flavour, rich tobacco taste, strong taste, good aftertaste, taste like Marlboro, smooth, satisfying, mild, mellow, low strength, artificial taste, cool, fresh or menthol flavoured. Since pack colours influence consumers’ perceptions of the cigarettes’ taste and strength, selecting or changing package colours was seen not only as part of brand and image development, but also as part of ‘product development’, similar to selecting the cigarettes’ physical ingredients (table 1).

In the 1960s, Louis Cheskin Associates conducted ‘association tests’ with 1800 cigarette smokers to help PM determine which of three proposed pack colour combinations would most effectively create ‘favourable associations’ (eg, ‘high quality tobacco’, ‘rich tobacco flavour’, ‘mild’ and ‘low-tar and nicotine’) and be less likely to create ‘unfavourable associations’ (eg, ‘low quality tobacco’, ‘little tobacco flavour’, ‘strong’ and ‘high tar and nicotine’).31 These associations were based on the packages alone; the respondents never smoked the cigarettes. Packages with certain colour and label combinations (eg, brown pack with a brown label) were more effective than others (eg, brown package with red-brown label) at leading consumers to believe that the cigarettes inside the pack had ‘rich tobacco flavour’, ‘high quality tobacco’ and ‘low-tar and nicotine’.31

RJR studied how package colour influences consumers’ perceptions of cigarette taste and strength when it began researching a new package for Camel Filters in 1975. They aimed to develop a contemporary package that would appeal to young men while retaining the cigarette’s flavour quality perception. RJR contracted Data Development Corporation to conduct a package study to test consumers’ perceptions of the product’s taste attributes (as well as brand imagery).70–72 Study respondents first rated how they perceived the cigarettes would taste based only on seeing four different test packages, and next rated the cigarettes’ taste ‘attributes’ after smoking cigarettes from one of the test packs.70–72 The study found no significant differences in how consumers perceived the cigarettes’ characteristics after smoking them and concluded that the risk of adopting any of the proposed alternative packs would outweigh the potential gains of younger imagery: ‘“Younger” imagery seems to be increasing at the expense of some [perceived] flavor quality of the cigarette. The current pack is seen more than the others as denoting a cigarette for people who are looking for flavor [emphasis added]’.70

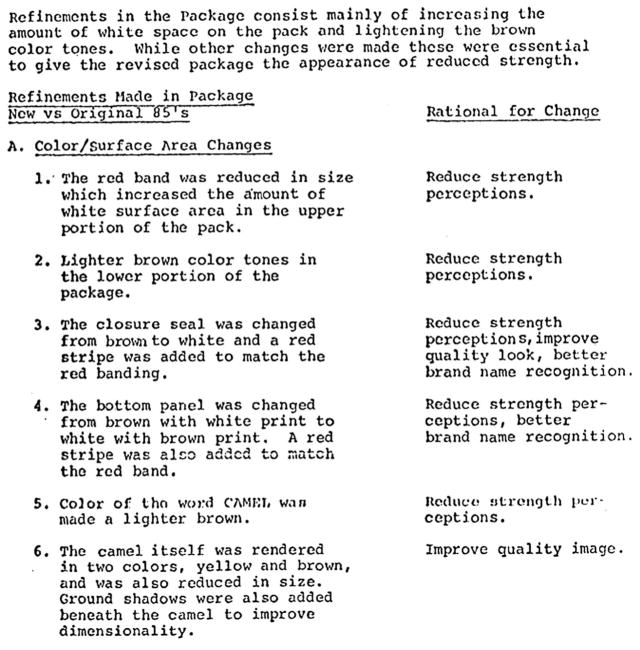

In 1979, RJR began testing revised Camel Filters packaging. RJR sought to reduce consumers’ perception that Camel Filters were stronger than most other cigarettes while at the same time maintain desired product perceptions (taste, satisfaction, ‘tar’ and nicotine, smoothness) and brand attributes (masculine, young adult, rugged).68,73 Test respondents viewed package prototypes and measured their perceptions of the product’s strength, harshness, taste, quality, smoothness, ‘satisfaction’ and tar perception, in addition to measuring the pack’s visual prominence.68 The tests revealed that small pack refinements such as increasing white space, reducing the red band and lightening brown colour tones could influence how consumers perceived cigarette strength (figure 1).68

Figure 1.

Details of proposed refinements in a 1979 new package design for Camel Filters, consisting mainly of increasing the amount of white space, reducing the red band and lightening the brown colour tones to reduce consumers’ perceptions of the cigarettes’ strength.68

Although Marlboro Ultra Lights were not actually marketed until the late 1990s, in 1981 PM conducted internal consumer taste preference studies in which smokers tested identical Marlboro Ultra Lights cigarettes in a blue pack versus a red pack.54 Marlboro smokers generally preferred the cigarettes in the red package and perceived the cigarettes in the red pack to have more taste than those in the blue pack. Some found cigarettes in the blue package ‘too mild’ or ‘not easy drawing’, while others perceived the cigarettes in the red pack as ‘too strong’ or ‘harsher’ than those in the blue pack.54

In 1984, RJR launched ‘Project XG’ to create a product that would replace Marlboro as the most relevant brand among younger adult smokers….74 RJR recognised that to achieve this goal they needed to use package colours and design and ‘non-menthol taste cues’ to improve consumers’ perceptions of XG’s product attributes, resulting in more smoothness, more strength, more tobacco taste, less harshness and “a positive taste benefit similar to Marlboro but smoother…” (table 1).51

Maintaining full flavour in reduced tar cigarettes

Beginning in the 1970s, tobacco companies sought to create and market products that reportedly had reduced tar to address consumers’ health concerns while still delivering ‘full flavour’ that met consumers’ taste preferences.40,67,68,73,75–77

In 1977, responding to growing consumer health concerns and consistent with broader industry marketing practices, B&W began testing pack designs for a new Viceroy low-tar cigarette and examined how changes in package colours could lead consumers to believe that the cigarettes inside were low-tar and full taste.40 B&W faced the problem that perceptions of tar level and taste are not independent; low-tar is associated with weak taste and high-tar is associated with full taste. Researchers sought a pack design that would receive the same taste ratings as, but lower tar ratings than, Marlboro Lights.40 After initially finding variations in pack design produced only minor changes in the taste/tar perception,39 B&W researchers recommended using a royal blue pack to make a clear statement about ‘taste’ and ‘impact’ and letting advertising pull down the perceived tar level (table 1).56

To verify that the proposed package design for the new low-tar cigarette supported the desired product perceptions, B&W tested Viceroy Rich Lights in royal blue versus silver packs in 1978.57 After participants smoked cigarettes from royal blue and silver packs that, unbeknownst to them, contained identical cigarettes, they rated the cigarettes from each pack on different attributes.78 B&W analysed respondents’ taste perceptions and concluded, “The blue pack outscored the silver pack on satisfaction, full taste, tobacco taste. The silver pack achieved higher score for aftertaste, mildness, smoothness, mellowness, freshness”.58 The test also showed that the silver pack was perceived as ‘low-tar’ cigarettes and ‘for women’, while the blue pack was perceived as ‘average-tar’ and ‘for men’ (table 1).58

In 1979, RJR began ‘Project BY’, an effort to enter the non-menthol, full-flavour, low-tar (‘FFLT’) market category, and conducted a study to inform new BY packaging alternatives, aiming to appeal to its target market of FFLT male smokers aged 25–34.55 In addition to examining the overall appeal and user imagery associated with alternative packages, the study assessed how changes in pack design affected consumers’ ‘product perceptions’ including ‘satisfaction’, ‘taste’, ‘tar and nicotine’ and ‘smoothness’.55 RJR’s study based on viewing (not smoking) 27 proposed packs including variations on names, colours and designs concluded that these elements work together to create product perceptions (eg, wedge and diagonal designs could mitigate high tar perceptions from dark colours but maintain positive taste perceptions), effectively contributing to product development.55

RJR’s changes in Camel pack designs from 1930 to 2005 (figure 2, top) illustrate that they used pack colours to influence consumers’ perceptions of the cigarettes’ taste. In 1930, Camel packs used a dark tan background above and below the camel, a dark brown camel and dark lettering.79 In 1961, the dark background was removed above the camel and lightened below the camel, and the camel colour was lightened.80 In 1972, all of the background was white, the lettering was lightened and the tab was changed from dark blue to white for its ‘low tar Camel taste’.81 In 1990, the dark pyramid was removed, and the lettering was further lightened for ‘extra mild Camel taste’.82 In 2005, the tan trees were removed, the camel was made lighter, and the pyramid was silver for ‘extra smooth and mellow’ taste and ‘ultra-lights’ cigarettes.83

Figure 2.

Top: Examples of changes in Camel pack designs from 1930 through 2005, illustrating how RJR changed pack colours in ways that the research presented in this paper indicate would affect consumers’ perceptions of the cigarettes’ taste, with progressively lighter colours and more white conveying ‘low tar’ taste, ‘extra mild’ taste and ‘extra smooth and mellow’ taste.79–83 Bottom: Examples of Camel pack designs after enactment of the US Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act in 2009, including a 2010 pack84 from RJR’s ‘Break Free Adventure’ that uses the word ‘Blue’ in lieu of the newly forbidden identifiers ‘low’, ‘light’ or ‘mild’, and Camel Crush packs 85 that use black and red colours for ‘bold taste’ and green and white colours for ‘menthol fresh’ taste.

In 2010, shortly after FSPTCA’s enactment, RJR introduced the Camel ‘Break Free Adventure’ campaign84 aimed at young adults and hipsters. Since FSPTCA forbade the use of terms such as ‘light’ and ‘mild’ seen in the 1972 and 1990 packs, the 2010 pack used the identifier ‘Blue’ and a white background to connote ‘light’, but also used colours, themes and geographic references that appeal to their target young consumers. In 2014, RJR re-introduced Camel Crush, a novel tobacco product containing a capsule with menthol-flavoured liquid (subsequently pulled from the market by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2015). Camel Crush packs85 used the same concepts that Cheskin highlighted in the 1950s, with ‘bold tasting’ products using black and red packs and ‘menthol fresh’ products using white and green packs (figure 2, bottom).

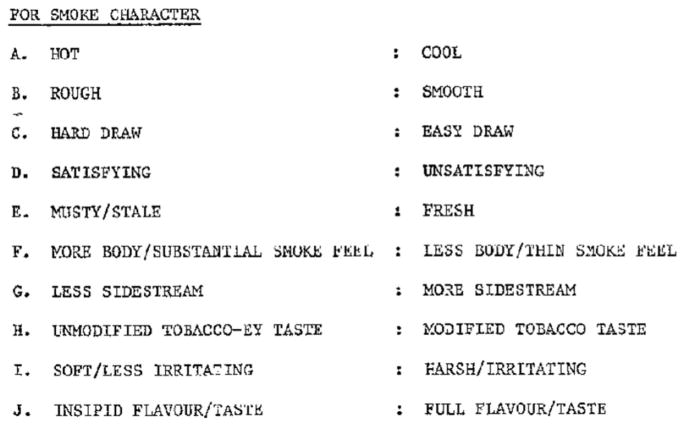

Attractiveness

The companies found that they could manipulate package colours to make the cigarettes inside more attractive to consumers by influencing perceptions that the cigarettes are higher quality, more prestigious or upscale, convey trust or responsibility, are more exciting or relaxing or are especially appealing to men, women or young people (table 1). For example, in the 1970s BAT began using the repertory grid technique to quantify how important brand image variables, including colour, are to individuals’ assessments of cigarettes’ sensory properties.86 Based on psychologist George Kelly’s theory that individuals develop personal ‘constructs’ (basic terms expressed as contrasts between two ideas) to describe their experience, respondents were shown cigarette packs with design variations (including changes in colours, lettering, dominant design shapes elements and motifs or crests)41 and asked what associations the pack appearance created, what type of smoking experience they would expect from the cigarettes inside those packs and the general personality of people they would expect to smoke those cigarettes.86 Interviewers elicited sets of descriptive terms (‘constructs’) and created lists of opposite terms (‘binary grids’) to describe the ‘smoke character’ (figure 3) (as well as other attributes) associated with each pack,70,86 and BAT hoped that this initial study would demonstrate how the repertory grid technique could quantify consumers’ subjective perceptions of cigarette characteristics.

Figure 3.

Binary grid used by British American Tobacco researchers in 1978 to describe consumers’ perceptions of the ‘smoke characte’ associated with cigarette packs.86

DISCUSSION

As early as the 1950s, tobacco companies developed a sophisticated understanding that by changing pack colours they could not only alter brand appeal and make misleading health claims,1,9,11–13,27,87,88 but could also change consumers’ perceptions of the taste, strength and other sensory attributes of the cigarettes inside the packages without changing the physical ingredients of the cigarettes themselves. The companies use pack colours to alter the characteristics of the products, just as they use tobacco blends, flavourings and additives to change the products’ physical characteristics to manipulate consumers’ perceptions of the cigarettes’ flavour and taste. They design packages that create the ideal balance between ‘low-tar’ and ‘full-flavour’ attributes. For example, the companies understand that by merely increasing the use of red on packs, consumers perceive the cigarettes inside to have fuller, stronger, richer tobacco taste,37,47–51,53,68 and by lightening the pack’s colour palette or increasing the amount of white, companies can reduce perceptions of the cigarette’s strength without changing the cigarette’s formula.48–51,63–66,68 Importantly, RJR’s manual stated that beyond marketing, designing new packages was important because “a package change can create a ‘new’ product” by giving customers the existing product in a new form (emphasis added).37

Implications for tobacco product regulation

The FCTC89 (to which USA is not a party) and FSPTCA90 regulate new tobacco product introductions, ingredients disclosures and packaging and labelling. The Guidelines for Implementation of FCTC Articles 9 (product content regulation) and 10 (product disclosures regulation) recommend that Parties prohibit or restrict ingredients that may be used to increase the attractiveness of tobacco products, that have certain colouring properties that make the products more appealing or create the impression that they have a health benefit.91 The Guidelines for Implementation of Article 11 (packaging and labelling) seek to counter established industry tactics for circumventing tobacco packaging and labelling regulation and urge Parties to consider adopting standardised packaging measures to prevent the industry from continuing to use packaging and labelling to mislead consumers and promote its products.26

Our findings provide evidence of how tobacco companies adjust pack designs and colours to manipulate consumers by altering their perceptions of the products inside the packs and to create the impression that some cigarettes are less harmful than others. This evidence can be used to support adoption of measures to prevent companies from using packaging to deceive consumers and to regulate the introduction and marketing of new tobacco products. In particular, these findings and the accompanying legal analysis (see online supplementary text) support mandatory reporting of package designs along with the mandatory reporting of physical product contents, because package designs influence consumers’ perceptions of the cigarettes’ taste as do physical tobacco constituents (eg, additives and flavourings) that would be required to be disclosed under such reporting laws. For example, under Canada’s tobacco reporting regulations, manufacturers and importers must provide Health Canada with annual reports that include tobacco product ingredients, toxic constituents, toxic emissions as well as information on product packaging.92,93 Our findings support regulations that would specifically mandate the reporting of colour changes in packaging reports and would support adoption of similar measures by other countries.

Packaging and labelling colour should be treated as tobacco product ingredients

The FSPTCA requires companies to obtain authorisation from FDA before introducing new tobacco products into the market, and products with different characteristics (including changed ingredients and designs) will not be authorised unless it is demonstrated that the changes would be appropriate for the protection of public health.94 The industry documents summarised here demonstrate that tobacco companies routinely change colours in cigarette packaging and labelling not merely to communicate information about the product, but also to change consumers’ perceptions of the product’s taste and strength, thereby changing the product’s ingredients and effectively creating a ‘new product’. Since these design changes do not involve words, they allow tobacco companies to evade laws and regulations designed to prevent the companies from manipulating consumers. Indeed, package design experts wrote in 1995 that colour is a potent tool because it is “beyond the law. Words can be regulated, and so can pictures, but color cannot.”34

FDA initially stated that it would consider tobacco product labels and packaging as ‘part’ of the product in its premarket reviews,95 but then retreated from this position96,97 after industry pressure and lawsuits.98,99 FDA’s original position was appropriate and consistent with industry understanding and practices, and it should be followed (see online supplementary text). Likewise, other countries should treat products with packaging changes as new products when implementing FCTC Article 11.25,26

Implications for standardised packaging

Australia became the first country to mandate standardised packaging along with product standarisation in December 2012,100 and in 2015 Ireland101 and the UK102 passed similar laws. In December 2015, France passed a standardised packaging law,103 in March 2016, Canada announced plans to adopt standardised packaging104 and Finland, Norway, Sweden and New Zealand were expected to follow suit, with the European Union as a whole also considering the measure.105

Before Australia’s law was implemented, several papers suggested that standardised packaging may help reduce misperceptions of risk communicated through pack design3,4,6,7,9,11,16,88 and help promote cessation, especially among youth.87,106,107 Standardised packaging may reduce smoking in current smokers by making the packs less appealing,108,109 by producing less craving and motivation to seek tobacco110,111 and by increasing attention to health warnings.112,113 Since the introduction of standardised packaging in Australia, evidence among adult smokers suggests that plain packaging has achieved its specific objectives and reduced the appeal of tobacco products, increased the effectiveness of health warnings, helped reduce the extent to which smokers are misled about the harms of smoking114,115 and reduced the ability of the pack to appeal to young people.116 The industry documents reviewed in this paper can be used to support standardised packaging by confirming that companies use the colours on packaging to manipulate and impact consumers’ perceptions about taste, strength and relative risk of the cigarettes inside the pack.

CONCLUSION

Tobacco companies use cigarette pack colours to manipulate not only consumers’ brand choices and perceptions of harm, but also smokers’ experiences of the taste and strength of the cigarettes inside the pack to effectively create new products, just as they would by making changes to the cigarette’s ingredients or physical properties. Since changes in packaging colours influence consumers’ perceptions and experiences of smoking the cigarettes, including leading consumers to believe that the products taste better, these package changes effectively create new tobacco products. In countries that do not require standardised packaging, regulators should recognise this reality and consider colour equivalently to other changes in cigarette characteristics (eg, ingredients, additives and flavourings) when determining whether to permit new products on the market.

Supplementary Material

What this paper adds.

Cigarette pack colours are used not only to manipulate consumers’ brand choices and perceptions of harm, but also to change smokers’ perceptions of the taste and strength of the cigarettes inside the pack without changing the cigarettes themselves.

When tobacco companies change pack colours, they effectively create new tobacco products, just as when they make changes to the cigarettes’ ingredients, additives or flavourings; all new tobacco products should be subject to equivalently rigorous new tobacco product review.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Janet Hoek and Lucy Popova for providing valuable feedback on the manuscript.

Funding This work was funded by National Cancer Institute grants CA-087472 and 1P50CA180890 from the National Cancer Institute and Food and Drug Administration Center for Tobacco Products. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health or the US FDA. The funding agencies played no role in the conduct of the research or preparation of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Competing interests None declared.

Provenance and peer review Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement All source materials for this paper are publicly available. The tobacco documents are all available at the UCSF Legacy Tobacco Documents Library, http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu.

Contributors LKL collected the data and prepared the first draft of the paper. LKL and SG collaborated to prepare the final manuscript.

References

- 1.Wakefield M, Morley C, Horan JK, et al. The cigarette pack as image: new evidence from tobacco industry documents. Tob Control. 2002;11(Suppl 1):I73–80. doi: 10.1136/tc.11.suppl_1.i73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.National Cancer Institute. The role of the media in promoting and reducing tobacco use. Tobacco control monograph No. 19. Bethesda, MD: US Dept. of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute; 2008. http://cancercontrol.cancer.gov/brp/tcrb/monographs/19/m19_complete.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Moodie C, Ford A. Young adult smokers’ perceptions of cigarette pack innovation, pack colour and plain packaging. Aust Mark J. 2011;19:174–80. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Moodie C, Ford A, Mackintosh AM, et al. Young people’s perceptions of cigarette packaging and plain packaging: an online survey. Nicotine Tob Res. 2012;14:98–105. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntr136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Balbach ED, Gasior RJ, Barbeau EM. R.J. Reynolds’ targeting of African Americans: 1988–2000. Am J Public Health. 2003;93:822–7. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.5.822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Doxey J, Hammond D. Deadly in pink: the impact of cigarette packaging among young women. Tob Control. 2011;20:353–60. doi: 10.1136/tc.2010.038315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wakefield MA, Germain D, Durkin SJ. How does increasingly plainer cigarette packaging influence adult smokers’ perceptions about brand image? An experimental study. Tob Control. 2008;17:416–21. doi: 10.1136/tc.2008.026732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pollay RW, Dewhirst T. A Premiere example of the illusion of harm reduction cigarettes in the 1990s. Tob Control. 2003;12:322–32. doi: 10.1136/tc.12.3.322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hammond D, Dockrell M, Arnott D, et al. Cigarette pack design and perceptions of risk among UK adults and youth. Eur J Public Health. 2009;19:631–7. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/ckp122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hammond D, Parkinson C. The impact of cigarette package design on perceptions of risk. J Public Health (Oxf) 2009;31:345–53. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdp066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bansal-Travers M, Hammond D, Smith P, et al. The impact of cigarette pack design, descriptors, and warning labels on risk perception in the US. Am J Prev Med. 2011;40:674–82. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2011.01.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mutti S, Hammond D, Borland R, et al. Beyond light and mild: cigarette brand descriptors and perceptions of risk in the International Tobacco Control (ITC) Four Country Survey. Addiction. 2011;106:1166–75. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2011.03402.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yong HH, Borland R, Cummings KM, et al. Impact of the removal of misleading terms on cigarette pack on smokers’ beliefs about ‘light/mild’ cigarettes: cross-country comparisons. Addiction. 2011;106:2204–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2011.03533.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bansal-Travers M, O’Connor R, Fix BV, et al. What do cigarette pack colors communicate to smokers in the U.S.? Am J Prev Med. 2011;40:683–9. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2011.01.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act, Pub. L. No. 111-31, Section 911 (2009).

- 16.Peace J, Wilson N, Hoek J, et al. Survey of descriptors on cigarette packs: still misleading consumers? N Z Med J. 2009;122:90–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.King B, Borland R, Abdul-Salaam S, et al. Divergence between strength indicators in packaging and cigarette engineering a case study of Marlboro varieties in Australia and the USA. Tob Control. 2010;19:398–402. doi: 10.1136/tc.2009.033217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Altria Sales & Distribution. Retailer brochure: introducing new packaging on many Philip Morris USA (PM USA) brands. Philip Morris; 2010. [accessed 20 Apr 2015]. https://industrydocuments.library.ucsf.edu/tobacco/docs/fgmf0217. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Connolly GN, Alpert HR. Has the tobacco industry evaded the FDA’s ban on ‘Light’ cigarette descriptors? Tob Control. 2014;23:140–5. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2012-050746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.New packaging guide. Philip Morris; 2010. [accessed 11 Jan 2013]. [Author unknown] http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/xjn30i00. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sarmento J. FW: Packaging changes. Philip Morris; Jun 17, 2010. [accessed 22 Jan 2013]. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/xwr30i00. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pugh K. FDA pack identifiers. Philip Morris; Jan 28, 2010. [accessed 22 Jan 2013]. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/cjl30i00. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wilson D. [accessed 10 Apr 2015];Coded to obey law, Lights become Marlboro Gold. 2010 http://www.nytimes.com/2010/02/19/business/19smoke.html?_r=0.

- 24.Wilson D. [accessed 10 Apr 2015];FDA seeks explanation of Marlboro Marketing. 2010 http://www.nytimes.com/2010/06/18/health/18tobacco.html?_r=0.

- 25.World Health Organization. [accessed 01 Apr 2015];WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control, Article 11. 2005 http://www.who.int/fctc/text_download/en/

- 26.World Health Organization. [accessed 8 Apr 2015];Guidelines for implementation of Article 11 of the WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (packaging and labelling of tobacco products) 2008 http://www.who.int/fctc/guidelines/adopted/article_11/en/

- 27.Kotnowski K, Hammond D. The impact of cigarette pack shape, size and opening: evidence from tobacco company documents. Addiction. 2013;108:1658–68. doi: 10.1111/add.12183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cheskin L. Color guide for marketing media. Brown & Williamson; 1954. [accessed 20 Dec 2012]. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/yjb14f00. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Anderson SJ, McCandless PM, Klausner K, et al. Tobacco documents research methodology. Tob Control. 2011;20(Suppl 2):ii8–11. doi: 10.1136/tc.2010.041921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dupuis RN. Challenges in tobacco research. Philip Morris; 1955. [accessed 15 Jan 2014]. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/gde58e00. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cheskin L. Philip Morris; Mar 26, 1965. [accessed 19 Dec 2012]. File No. 1965 A-1 Confidential Report Association Tests: Philip Morris Filter Packages. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/tid05e00. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cheskin L. Philip Morris; Sep 30, 1966. [accessed 19 Dec 2012]. Code No. A-3 660000 Confidential Report Association Test: Philip Morris Filter (Brown) Packages. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/xid05e00. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sherrill J. Trip Report to Chicago September 2, 1970 (700902) RJ Reynolds; Sep 09, 1970. [accessed 19 Dec 2012]. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/rbg69d00. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hine T. The total package seeing and believing. Lorillard; 1995. [accessed 21 Dec 2012]. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/uxh54a00. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sensory Science 101. Philip Morris; Oct 08, 2004. [accessed 10 Jan 2013]. [Author unknown] http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/eza90g00. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cheskin L. How to predict what people will buy. New York: Liveright Publishing Corporation; 1957. https://archive.org/stream/howtopredictwhat00ches-page/n5/mode/2up. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Brand marketing training module. RJ Reynolds; [accessed 21 Dec 2012]. [Author and date unknown] http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/gqy09d00. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cooper KR. Package testing. Lorillard; Nov 29, 1978. [accessed 14 Jan 2014]. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/quw41e00. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Greene J. Old Gold Filter package test. Lorillard; Dec 14, 1978. [accessed 14 Jan 2014]. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/vxn10e00. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Viceroy low tar pack design test. Brown & Williamson; Dec 12, 1977. [accessed 14 May 2013]. [Author unknown] http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/bxs00f00. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Marketing news. British American Tobacco; 1973. [accessed 11 Jan 2013]. [Author unknown] http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/itg64a99. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Marlboro—the pack the people picked. RJ Reynolds; 1970. [accessed 19 Dec 2012]. [Author unknown] http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/joz51c00. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Somasundaram M. Wall Street Journal. [accessed 19 Dec 2012];Red Packages Lure Shoppers Like Capes Flourished at Bulls: Marlboro, Coca-Cola, Colgate Wear Most Popular Color on Global Market Shelves. 1995 http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/kpn39h00.

- 44.Never say die: history of Red Roof Pack. Philip Morris; 1993. [accessed 10 Apr 2015]. [Author unknown] https://industrydocuments.library.ucsf.edu/tobacco/docs/mgdx0122. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cullman JF. An address by Joseph F. Cullman, 3rd Executive Vice President of Philip Morris Inc before the Chicago Federated Advertising Club, Chicago, Illinois, on Thursday, 551020. Philip Morris; Oct 20, 1955. [accessed 1 Aug 2013]. Cigarette marketing today. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/cms34e00. [Google Scholar]

- 46.GR&DC Research Programme 1984—1986 psychology research. British American Tobacco; [accessed 7 Jan 2013]. [Author unknown] http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/qgn36a99. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bockweg T, Chapple N, Cornell C, et al. Color documentation for Doral packaging colors. RJ Reynolds; Jan 16, 2001. [accessed 12 Jun 2013]. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/hsu14j00. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cato Gobe & Associates. RJ Reynolds; 1991. [accessed 19 Dec 2012]. Savings segment project for R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Company a Visual Category Investigation First Presentation. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/rup03d00. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Packaging. RJ Reynolds; 1987. [accessed 2 Jan 2013]. [Author unknown] http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/yre05d00. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Miller L. British American Tobacco; May 23, 1986. [accessed 7 Jan 2013]. Principles of measurement of visual standout in pack design: report no. RD 2039. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/ihb34a99. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Project XG packaging briefing document. RJ Reynolds; 1984. [accessed 8 Jan 2013]. [Author unknown] http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/lkc85d00. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Project XG packaging development. RJ Reynolds; 1984. [accessed 8 Jan 2013]. [Author unknown] http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/mkc85d00. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Marlboro Milds Menthol test market image study—topline report. Philip Morris; 1999. [accessed 23 Jan 2013]. [Author unknown] http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/zkv39h00. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Isaacs J. Philip Morris; 1981. [accessed 25 Jan 2013]. Identified HTI test of Marlboro Ultra Lights in a Blue Pack Versus Marlboro Ultra Lights in a Red Pack (Project No. 1256/1257) http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/geb36e00. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Project BY package exploratory study (MDD #79-1985) executive summary. RJ Reynolds; 1979. [accessed 23 Sep 2014]. [Author unknown] http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/emf49d00. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Viceroy low tar pack design test, phase II. Brown & Williamson; Jan 05, 1978. [accessed 14 May 2013]. [Author unknown] http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/dxs00f00. [Google Scholar]

- 57.McCafferty B. Viceroy Rich Lights pseudo product test. Brown & Williamson; Feb 08, 1978. [accessed 14 May 2013]. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/dys00f00. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Viceroy Rich Lights product, pack, and advertising testing of blue and silver packs. Brown & Williamson; 1978. [accessed 23 Jan 2013]. [Author unknown] http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/ews00f00. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Marlboro test market launch of Marlboro Milds Menthol. Philip Morris; 1999. [accessed 12 Sep 2014]. [Author unknown] http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/fkp00i00. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sun Research Corporation. Executive summary—a qualitative focus on new product development for Marlboro: Marlboro Milds. Philip Morris; May, 1998. [accessed 12 Sep 2014]. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/wdy89h00. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Bennette A, Ellis N. Marlboro Milds research—final report. Philip Morris; May 28, 1998. [accessed 12 Sep 2014]. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/feb99h00. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Monieson M. Milds research findings. Philip Morris; Jun 17, 1998. [accessed 12 Sep 2014]. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/xdy89h00. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Packaging graphics. RJ Reynolds; 1987. [accessed 2 Jan 2013]. [Author unknown] http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/cse05d00. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Project Spa Quantitative Package test. RJ Reynolds; 1986. [accessed 8 Jan 2013]. [Author unknown] http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/tvo35d00. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Toben TP. New business research and development report: Project Spa Package Test. RJ Reynolds; Apr 18, 1986. [accessed 8 Jan 2013]. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/lko64d00. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Packaging status. RJ Reynolds; 1984. [accessed 8 Jan 2013]. [Author unknown] http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/xls35d00. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Vasudevan B. Barclay Pack Color Change. Brown & Williamson; Sep 07, 1994. [accessed 19 Dec 2012]. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/aoq30f00. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Etzel EC. RJ Reynolds; 1979. [accessed 11 Dec 2012]. Camel Filter revised packaging test. consumer research proposal. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/qxb79d00. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Pasterczyk RC. Appendix II—new business research and development report: Project CMB Package test. RJ Reynolds; May 27, 1987. [accessed 15 Mar 2013]. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/lgm83d00. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Data Development Corp. Recommendations. RJ Reynolds; 1975. [accessed 11 Dec 2012]. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/sxb79d00. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Data Development Corp. RJ Reynolds; 1975. [accessed 11 Dec 2012]. Appendix Table 1. Anticipated usage of Camel Filters—pre-trial among total respondents. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/txb79d00. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Data Development Corp. Camel Filter Package study. RJ Reynolds; 1975. [accessed 11 Dec 2012]. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/rxb79d00. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Monahan EN. Consumer research proposal: Camel Filter Alternate Package Research (MRD #79-) RJ Reynolds; 1979. [accessed 11 Dec 2012]. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/pxb79d00. [Google Scholar]

- 74.DSN. TSB Technology Optimization Program. Research; Oct 16, 1984. [accessed 19 Sep 2014]. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/ylk76b00. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Rawson DE. Salem King and Salem Lights Package Testing. RJ Reynolds; Apr 12, 1978. [accessed 19 Dec 2012]. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/ows13a00. [Google Scholar]

- 76.RJR. R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Co. Developing New Cigarette. 75. Vol. 9. RJ Reynolds; Sep 14, 1987. [accessed 13 Mar 2013]. RJR News. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/wre05d00. [Google Scholar]

- 77.SHF cigarette market place opportunities search and situation analysis volume ii management report. Lorillard; 1976. [accessed 23 Jan 2013]. [Author unknown] http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/dxy41e00. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Kightlinger SA. Viceroy Rich Lights pseudo-product/pack test (Project #197829) Brown & Williamson; Feb 14, 1978. [accessed 14 May 2013]. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/uws00f00. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Stanford Research into the Impact of Tobacco Advertising. [accessed 8 Mar 2016];Camel pack design. 1930 http://tobacco.stanford.edu/tobacco_main/images.php?token2=fm_st151.php&token1=fm_img4657.php&theme_file=fm_mt018.php&theme_name=SmokinginSports&subtheme_name=Football.

- 80.Stanford Research into the Impact of Tobacco Advertising. [accessed 8 Mar 2016];Camel pack design. 1961 http://tobacco.stanford.edu/tobacco_main/images.php?token2=fm_st151.php&token1=fm_img4618.php&theme_file=fm_mt018.php&theme_name=SmokinginSports&subtheme_name=Football.

- 81.Stanford Research into the Impact of Tobacco Advertising. [accessed 8 Mar 2016];Camel pack design. 1972 http://tobacco.stanford.edu/tobacco_main/images.php?token2=fm_st100.php&token1=fm_img9572.php&theme_file=fm_mt007.php&theme_name=Light,Super&UltraLight&subtheme_name=Light.

- 82.Stanford Research into the Impact of Tobacco Advertising. [accessed 8 Mar 2016];Camel pack design. 1990 http://tobacco.stanford.edu/tobacco_main/images.php?token2=fm_st105.php&token1=fm_img3270.php&theme_file=fm_mt007.php&theme_name=Light, Super & Ultra Light&subtheme_name=Mild as Ma.

- 83.Stanford Research into the Impact of Tobacco Advertising. [accessed 8 Mar 2016];Camel pack design. 2005 http://tobacco.stanford.edu/tobacco_main/images.php?token2=fm_st203.php&token1=fm_img6073.php&theme_file=fm_php&theme_name=&subtheme_name=

- 84.Campaign for Tobacco Free Kids. [accessed 8 Mar 2016];Camel’s Break Free Adventure Contest. 2010 http://www.tobaccofreekids.org/pressoffice/camelpromotion/camelbreakfreeadventure.pdf.

- 85.Bella’s Blog. [accessed 8 Mar 2016];Play Camel Crush’s instant win game. 2014 http://bellasblog.info/2014/01/15/play-camel-crushs-instant-win-game/

- 86.Ferris RP, Oldman M. Brown & Williamson; Sep 27, 1978. [accessed 10 Jan 2013]. Application of repertory grid technique: I. an investigation of brand images report no. RD.1617. http://legacy.library.ucsf.edu/tid/ebm00f00. [Google Scholar]

- 87.Gallopel-Morvan K, Moodie C, Hammond D, et al. Consumer perceptions of cigarette pack design in France: a comparison of regular, limited edition and plain packaging. Tob Control. 2012;21:502–6. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2011-050079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Hammond D. “Plain packaging” regulations for tobacco products: the impact of standardizing the color and design of cigarette packs among UK adults and youth. Salud Publica Mex. 2010;52:S226–32. doi: 10.1590/s0036-36342010000800018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.World Health Organization. WHO framework convention on tobacco control. Geneva, Switzerland: 2005. [accessed 1 Apr 2015]. http://www.who.int/fctc/text_download/en/ [Google Scholar]

- 90.Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act, Pub. L. 111–31 (2009).

- 91.World Health Organization. Partial guidelines for implementation of Articles 9 and 10 of the WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (Regulation of the contents of tobacco products and regulation of tobacco product disclosures) [accessed 1 Apr 2015];2012 http://www.who.int/fctc/guidelines/adopted/article_9and10/en/

- 92.Health Canada. [accessed 1 Apr 2015];Tobacco reporting regulations. 2005 http://www.hc-sc.gc.ca/hc-ps/tobac-tabac/legislation/reg/indust/index-eng.php.

- 93.World Health Organization. [accessed 1 Apr 2015];Best practices in tobacco control: regulation of tobacco products: Canada Report. 2005 http://www.who.int/tobacco/global_interaction/tobreg/CanadaBestPracticeFinal_ForPrinting.pdf?ua=1.

- 94.Family Smoking Prevention and Tobacco Control Act, Pub. L. No. 111-31, Section 910 (2009).

- 95.FDA Center for Tobacco Products. Draft Guidance for Industry and Food and Drug Administration Staff. Demonstrating the substantial equivalence of a new tobacco product: responses to frequently asked questions. 2011 Sep; [Google Scholar]

- 96.FDA Center for Tobacco Products. [accessed 25 May 2016];Guidance for industry, demonstrating the substantial equivalence of a new tobacco product: responses to frequently asked questions. 2015 Mar 4; and reissued on September 8, 2015. Available at: http://www.fda.gov/TobaccoProducts/GuidanceComplianceRegulatoryInformation/ucm436462.htm.

- 97.FDA Center for Tobacco Products. [accessed 29 May 2015];This week in CTP: FDA announces interim enforcement policy related to substantial equivalence FAQ guidance. 2015 http://www.fda.gov/TobaccoProducts/NewsEvents/ucm448854.htm.

- 98.Philip Morris USA Inc. et al. v. U.S. Food and Drug Administration et al. U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia; 2015. [accessed 25 May 2016]. Case No. 1:15-cv-00544. http://www.plainsite.org/dockets/2l1grm3pb/district-of-columbia-district-court/philip-morris-usa-inc-et-al-v-united-states-food-and-drug-administration-et-al/ [Google Scholar]

- 99.Field E. [accessed 5 Jun 2015];Big tobacco sues FDA over label guidance. 2015 https://www.law360.com/articles/642999/big-tobacco-sues-fda-over-label-guidance-?article_related_content=1.

- 100.Tobacco Plain Packaging Act 2011. No. 148, 2011 as amended. [accessed 1 Apr 2015];2011 http://www.comlaw.gov.au/Details/C2013C00190.

- 101.BBC. [accessed 10 Feb 2016];Republic of Ireland passes cigarette plain package law. 2015 http://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-31722210.

- 102.Perraudin F. [accessed 10 Feb 2016];MPs pass legislation to introduce standardised cigarette packaging. 2015 http://www.theguardian.com/politics/2015/mar/11/mps-pass-legislation-introduce-standardised-cigarette-packaging.

- 103.The Guardian. [accessed 10 Feb 2015];France votes for plain cigarette packaging from 2016. 2015 http://www.theguardian.com/society/2015/dec/18/france-votes-for-plain-cigarette-packaging-from-2016.

- 104.Pfeffer A CBC News. [accessed 20 Mar 2016];Federal government moves ahead on plain packaging for cigarettes. 2016 http://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/ottawa/plain-package-cigarette-plan-1.3492992.

- 105.Action on Smoking & Health (ASH) [accessed 1 Oct 2015];Plain packaging for tobacco will become the global norm. 2015 http://ash.org/plain-packs-pr/

- 106.Hoek J, Wong C, Gendall P, et al. Effects of dissuasive packaging on young adult smokers. Tob Control. 2011;20:183–8. doi: 10.1136/tc.2010.037861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Scheffels J, Sæbø G. Perceptions of plain and branded cigarette packaging among Norwegian youth and adults: a focus group study. Nicotine Tob Res. 2013;15:450–6. doi: 10.1093/ntr/nts153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Hoek J, Gendall P, Gifford H, et al. Tobacco branding, plain packaging, pictorial warnings, and symbolic consumption. Qual Health Res. 2012;22:630–9. doi: 10.1177/1049732311431070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Stead M, Moodie C, Angus K, et al. Is consumer response to plain/standardised tobacco packaging consistent with framework convention on tobacco control guidelines? A systematic review of quantitative studies. PLoS One. 2013;8:e75919. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0075919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Hogarth L, Maynard O, Munafò M. Plain cigarette packs do not exert Pavlovian to instrumental transfer of control over tobacco-seeking. Addiction. 2015;110:174–82. doi: 10.1111/add.12756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Brose LS, Chong CB, Aspinall E, et al. Effects of standardised cigarette packaging on craving, motivation to stop and perceptions of cigarettes and packs. Psychol Health. 2014;29:849–60. doi: 10.1080/08870446.2014.896915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Munafò M, Roberts N, Bauld L, et al. Plain packaging increases visual attention to health warnings on cigarette packs in non-smokers and weekly smokers but not daily smokers. Addiction. 2011;106:1505–10. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2011.03430.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Maynard OM, Munafo MR, Leonards U. Visual attention to health warnings on plain tobacco packaging in adolescent smokers and non-smokers. Addiction. 2013;108:413–19. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2012.04028.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Hastings G, Moodie C. Death of a salesman. Tob Control. 2015;24:ii1–2. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2015-052285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Wakefield M, Coomber K, Zacher M, et al. Australian adult smokers’ responses to plain packaging with larger graphic health warnings 1 year after implementation: results from a national cross-sectional tracking survey. Tob Control. 2015;24:ii17–25. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2014-052050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.White VM, Williams T, Wakefield M. Has the introduction of plain packaging with larger graphic health warnings changed adolescents’ perceptions of cigarette packs and brands? Tob Control. 2015;24:ii42–9. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2014-052084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.