Abstract

Transplantation of solid organs between genetically distinct individuals leads, in the absence of immunosuppression, to T cell-dependent transplant rejection. Activation of graft-reactive T cells relies on the presentation of transplant-derived antigens (intact donor MHC molecules or processed peptides on host MHC molecules) by mature dendritic cells (DCs). This review will focus on novel insights regarding the steps for maturation and differentiation of DCs that are necessary for productive presentation of transplant antigens to host T cells. These steps include the licensing of DCs by the microbiota, their activation and maturation following recognition of allogeneic non-self and their capture of donor cell exosomes to amplify presentation of transplant antigens.

Recent Advances on Innate Immunity in Transplantation

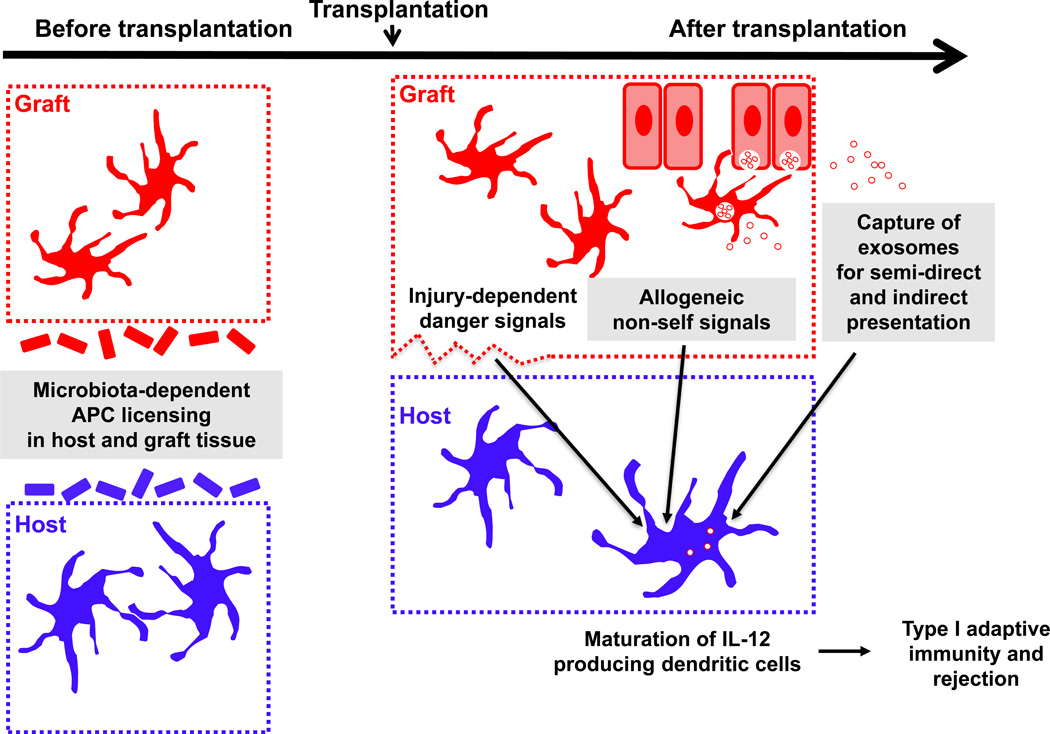

Transplantation of organs from cadaveric or living donors can cure end-stage organ failure in transplant recipients. However, with the exception of organ donation between identical twins, transplantation sets up a cascade of inflammatory events leading to recognition of the allograft (see Glossary) by the host’s immune system and to T cell-dependent transplant rejection. To prevent rejection, transplant patients take global immunosuppressive medications lifelong, which can lead to side effects as well as increased susceptibility to infections and malignancies. In order to develop more specific and less toxic therapies, a better understanding of the steps leading to robust activation of alloreactive T cells by innate immune cells is required. To this end, a large body of work has focused on the biology of alloreactive T cells and approaches to delete or suppress them. In recent years, several groups have turned their attention to the antigen-presenting cells (APCs) that initiate the activation of allogeneic T cells, revealing at least 3 new mechanisms by which innate immunity controls the quality and robustness of alloreactive T cell priming (Figure 1). First, the composition of the microbiota within the donor and the host prior to transplantation was shown to tune the capacity of APCs to prime alloreactive T cells and dictate the subsequent kinetics of graft rejection. Second, following transplantation, recognition by recipient mononuclear phagocytes of non-self determinants in the donor graft, encoded by non-MHC genes, was found to promote maturation and differentiation of these cells enhancing subsequent priming of alloreactive T cells. Third, cell-to-cell communication via exosomes was found crucial to the transfer of intact donor MHC molecules from donor dendritic cells (DCs) onto the surface of host DCs for presentation to alloreactive T cells. This review will cover these novel determinants of the quality and potency of alloantigen presentation after solid organ transplantation.

Figure 1. Tuning of Antigen-Presenting Cells (APCs) Before and After Transplantation for Optimal Priming of Alloreactive T Cells.

Donor cells are represented in red and host cells in blue. The donor and host microbiota license innate immune cells at the steady state for subsequent immune responses, including alloimmunity. Following transplantation, recognition by host dendritic cells (DCs) of both danger signals and allogeneic non-self determinants promotes their maturation. Danger encompasses a variety of molecules released from the damaged graft tissue as a result of ischemia reperfusion injury at the time of transplantation. Allogeneic non-self could consist of yet to be discovered allodeterminants expressed on donor tissue (including potentially both hematopoietic and parenchymal cells) that are either related or unrelated to the MHC. These allogeneic signals appear critical in particular for the induction of IL-12. Capture of donor exosomes and likely of other types of extracellular vesicles (EVs) boosts their acquisition of alloantigen for semi-direct or indirect presentation to alloreactive T cells, ultimately leading to type I adaptive immunity and rejection.

Shaded boxes are described in more detail in corresponding sections of this review.

Recognition of Allografts: the Basics

The potency of the anti-donor response against an allograft depends on the frequency/number of host T cells that recognize alloantigens and their differentiation stage, but also on the degree of activation of innate immune cells that present such alloantigens. Alloreactive T cells include those that recognize intact donor MHC molecules on the surface of donor cells - referred in transplantation as the direct pathway of allorecognition-, and of peptides derived from polymorphic regions of the allogeneic MHC molecules or of non-MHC proteins presented by self-MHC molecules, which is known as the indirect pathway. Directly alloreactive T cells can also recognize, via the semi-direct pathway, donor MHC molecules transferred intact to host APCs [1]. This latter mechanism enables a single DC from the host to present simultaneously or not, (i) donor allopeptides loaded in self MHC molecules to indirect pathway CD4 T cells, and (ii) donor intact MHC molecules to direct pathway CD8 T cells [1] or, potentially, to directly alloreactive CD4 T cells. The semi-direct pathway provides a means by which indirectly alloreactive CD4 T cells cross-regulate positively or negatively the function of direct pathway CD8 T cells that interact with the same DCs [2–4].

The prevailing view is that the direct CD4 pathway is polyclonal and short-lived, since the number of donor passenger leukocytes is limited and decreases with time after transplantation, and that the indirect pathway is oligoclonal and long-lived [5, 6]. In most models, either pathway can by itself trigger acute rejection [7, 8]. The indirect CD4 pathway promotes alloantibody production and chronic rejection [9]. In contrast, the biological relevance of the semi-direct pathway in vivo is just beginning to be elucidated. Besides its role in cross-regulation between indirectly and directly alloreactive T cells, new evidence indicates that the semi-direct pathway may have a key role in allosensitization of direct pathway T cells in those instances where donor passenger leukocytes traffic to the graft-draining lymphoid organs in extremely low numbers (e.g. heart transplantation in mice), or are unable to migrate out of the graft due to excision of lymphatic vessels during surgery and lack of surgical blood vessel anastomoses (e.g. skin allografts)[10, 11]. Under these circumstances, soluble MHC molecules, released by the graft itself or by the relatively few donor passenger leukocytes that reach the lymphoid organs, are acquired by recipient APCs via a mechanism termed cross-dressing for presentation to directly alloreactive T cells via the semi-direct pathway.

The frequency of indirect T cells against a given allopeptide is < 1:100,000, a frequency that is similar to that of any nominal peptide presented via the canonical pathway [12]. By contrast, the fraction of directly alloreactive T cells against foreign intact MHC molecules is 100-fold to 1,000 fold higher, since thymic deletion does not select for or against T cells to recognize the hundreds of MHC alleles not expressed by the graft recipient [12]. Thus, the number of unique T cell clones that are alloreactive in a given host depends on the extent of genetic disparities between the donor and the recipient that can be recognized by the host’s T cells, with disparities in MHC alleles being a critical factor in the number of potential alloreactive clones. Following transplantation, both donor and recipient APCs can activate alloreactive T cells and their state of maturation is crucial to the magnitude and quality of the T cell response.

DCs are professional APCs with unique ability to present efficiently donor alloantigen to naïve T cells. Different DC subsets have been identified, including conventional, monocyte-derived, and plasmacytoid DCs [13]. Transplanted organs/tissues are populated by tissue-resident conventional DCs, which trigger activation of alloreactive T cells, directly by themselves or indirectly by transferring donor alloantigen to the recipient’s conventional DCs that reside in the graft-draining lymphoid organs [14, 15]. Monocyte-derived DCs, originated from blood monocytes, participate at a later time point by re-presenting donor alloantigen and promoting expansion of effector T cells inside the allograft [16]. Plasmacytoid DCs have been implicated in transplantation tolerance [17].

Microbiota-dependent Licensing of Innate Immune Cells for Priming of Alloimmunity

Knowledge of how the microbiota can influence innate immune maturation has increased exponentially in recent years, though fine understanding of mechanisms and implications in various disease settings is still emerging. One clue that the microbiota might be important in modulating the strength of an alloresponse following transplantation came from the clinical observation that organs colonized by microbiota, such as the intestine and the lung, were more susceptible to acute and chronic rejection than organs deemed sterile such as the heart and the kidney (OPTN/SRTR database, December 2012).

Innate Licensing Prior to Transplantation

In addressing the role of the microbiota in alloimmunity, Lei et al. found that pre-treating both donor and recipient mice with broad-spectrum antibiotics prior to transplantation, or use of germ-free mice devoid of microbiota, resulted in prolongation of minor mismatched skin graft survival [18], suggesting that certain microbial communities promoted transplant rejection. This was ascribed to an ability of the microbiota prior to transplantation to alter signaling pathways in lymph node APCs allowing them, after transplantation, to promote enhanced proliferation and IFN-γ production by alloreactive T cells. Interestingly, reconstitution of germ-free mice with fecal microbial communities from untreated mice had a positive licensing effect on APCs. However, transfer of microbes from mice pre-treated with antibiotics did not have this effect on APCs, despite similar total bacterial loads, suggesting that different bacterial communities could affect subsequent alloreactivity differently. Mechanistically, pre-antibiotic microbiota activated the type I interferon and the NF-κB pathways in host DCs more efficiently than post-antibiotic microbiota [18], although whether all or only specific DC subsets that are affected is not yet clear. Whether changing the pre-transplantation microbiota in host or donors in the clinic could impact transplant outcomes remains to be determined.

Analogies with Anti-tumor and Anti-viral Immunity

The ability of the microbiota to license APCs for priming of alloreactive T cells is reminiscent of similar positive APC tuning for initiation of anti-tumoral or anti-viral immunity. Indeed, improved anti-tumor immunity in mice colonized by commensal species from the genus Bifidobacterium correlated with increased expression of genes associated with the type I interferon pathway in splenic DCs from tumor-bearing mice [19]. The microbiota was also found to poise lung DCs to produce pro-IL-1β and pro-IL-18, facilitating their migration to draining lymph nodes following intranasal influenza A virus inoculation and promoting anti-viral T cell priming [20]. Similarly, the microbiota enhanced responsiveness of splenic macrophages to type I and type II interferon signaling enabling subsequent control of systemic LCMV or mucosal influenza viral replication [21]. Splenic DCs from germ-free mice were shown to have defects not in the expression of transcription factors such as NF-κB and type-I interferon-driven IRF3, but rather in the ability of these transcription factors to bind chromatin sites, and this correlated with increased histone H3 trimethylation at several inflammatory gene start sites [22]. This suggests that the microbiota may license innate cells by triggering cell-intrinsic epigenetic modifications. Epigenetic changes induced by bacteria have also been described in T cells, by short chain fatty acids produced by fermenting bacteria from the colon, which inhibit histone deacetylases (HDACs), and promote histone acetylation of the FoxP3 locus in T cells and Treg differentiation [23–25], but whether fermenting bacteria can affect graft outcome remains to be studied.

There is evidence that the microbiota can also regulate DC function through indirect mechanisms. Outer membrane vesicles (OMVs) released by commensal and pathogenic gram-negative bacteria stimulate DC maturation [26]. These vesicles carry bacterial components (e.g. LPS, DNA, RNA, proteins, enzymes) in a non-replicative way. OMVs can also promote mucosal tolerance. As example, commensal Bacteroides fragilis OMVs deliver immune-regulatory signals to intestinal DCs that promote generation of Tregs in the intestine [27]. Whether this is a mechanism by which the microbiota modulates graft survival needs to be investigated.

Potential Microbiota-dependent Innate Signaling after Tissue Injury

In addition to licensing innate cells at the steady state, the microbiota may also drive innate signals after tissue injury, as shown by the ability of specific intestinal commensal species, upon intestinal damage induced by dextran sulfate sodium (DSS), to drive the production of interleukin-1β by intestinal Ly6Chigh monocytes [28], a cell subset whose continuous replenishment from a pool of circulating monocytes is also dependent on the microbiota [29]. As tissue injury is a certainty following organ transplantation, which not only involves surgical sectioning of the skin, but also ischemia and reperfusion of the transplanted organ, it is conceivable that similar commensal-dependent signaling may be triggered in innate cells, perhaps helping explain the worse outcome of organs with a high commensal content, though this remains to be formerly addressed.

Following transplantation, it is thought that donor DCs need to migrate to secondary lymphoid organs to prime alloreactive T cells, but whether commensal-dependent alteration of DCs facilitates such migration is not known. MyD88- and TRIF-dependent signals may help promote migration of DCs from donor skin grafts into the host’s draining lymph nodes correlating with faster skin graft rejection [30, 31], but it is not clear if these adaptors mediate signals downstream from the microbiota or downstream from damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs). However, as mentioned above, microbiota-dependent licensing of innate immune cells can regulate innate cell migration that contributes to initiation of anti-viral immunity [20]. Similarly, lung colonization with Staphylococcus aureus was found to promote TLR2-dependent recruitment and maturation of M2 alveolar macrophages that helped reduce influenza-mediated acute lung injury [32]. Conversely, commensal signals can also prevent migration of select innate immune cell types, as shown in the case of intestinal luminal bacteria-capturing CX3CR1hi mononuclear phagocytes whose migration to mesenteric lymph nodes is enabled in antibiotic-treated mice [33]. Preventing migration in this case is important to avoid developing an immune response to intestinal commensals. Harnessing such property in transplant settings could theoretically be favorable for graft acceptance.

Impact of Tissue-specific Microbial Communities

The composition of the microbiota is different in different organs, and even in different regions of a given organ or tissue depending on the pH, mucus, surfactant or oil covering, moisture and oxygen content [34]. Moreover, because the microbiota can exert local and distal effects, it is not clear whether all microbial communities throughout the body contribute to (or are sufficient for) global innate poising, and/or whether each compartment exerts location-specific effects. The fact that both donor and recipient mice had to be treated with antibiotics to achieve prolonged survival of minor mismatched skin grafts [18] suggests at least redundant effects of donor and host microbiota. In terms of tissue-specific effects, skin-resident DCs have been shown to sense and respond to alterations in local microbial communities [35] and tune the function of local T cells in a manner dependent on the IL-1R pathway [36]. In clinical transplantation, longitudinal changes in microbial composition of transplanted intestine or transplanted lung have been associated with organ-specific transplant outcome, with a relative reduction in the phylum Firmicutes in the ileal effluent being associated with acute intestinal rejection, and colonization of transplanted lungs with small conidia Aspergillus or lack of recolonization by dominant pre-transplant species such as Pseudomonas in cystic fibrosis patients being associated with chronic lung rejection [37–39]. Thus, whether skin, lung and intestinal microbial communities can tune immune responses to only transplanted skin, lung or intestine, respectively, or can cross-regulate more global alloimmunity remains to be determined. In any case, the rapid reversibility of APC licensing following antibiotic treatment and rapid acquisition of positive tuning of APCs in conventionalized germ-free mice [18] indicates a very dynamic microbial-host dialogue that may be amenable to therapeutic manipulation in settings of transplantation where the timing of initial exposure to alloantigen is known. However, more research is needed to understand the specific effects on innate cells of select microbial species, individually or as part of communities, at different locations. Ultimately, the goal will be to determine whether select species or communities could synergize with immunosuppressive therapies to promote graft acceptance.

Non-self Recognition by Innate Immune Cells

Whether or not properly poised by the microbiota, APCs need to differentiate from immature to mature following transplantation to be able to prime alloreactive T cells. The role of antigen-presenting DCs in initiating the primary alloimmune response within secondary lymphoid tissue is well established [10, 40, 41]. However, two fundamental questions related to DC maturation and function in alloimmunity have lingered unanswered for some time. The first is the nature of the signal required for the induction of mature DCs and the second is whether DCs continue to play a role in the alloimmune response beyond its initiation phase. These questions have been recently addressed in mouse transplantation models, leading to novel insights into the immunobiology of allograft rejection.

How the Innate Immune System Senses the Allograft to Generate Mature DCs

The assumption in alloimmunity has been that the release of DAMPs from the graft at the time of transplantation elicits the activation of host DCs, which in turn trigger the adaptive alloimmune response. This model, known as the “danger hypothesis”, has several shortcomings. First is the observation that DAMPs induce the generation of DCs that support T lymphocyte proliferation but fail to drive T cell differentiation into the IFN-γ-producing lymphocytes that dominate in transplant rejection - the reason being that DAMPs are not sufficient to cause DCs to produce IL-12 [42, 43]. Second, the rejection of allografts mismatched with the recipient at more than a single minor histocompatibility antigen occurs promptly in the absence of major innate signaling pathways or cytokines that mediate the actions of DAMPs [30, 44–47]. For example, Myd88 knockout, Myd88/TRIF double knockout, and intereferon-1 (IFN-1) receptor knockout recipients reject MHC-mismatched allografts without significant delay. Third, allografts parked in T lymphocyte-deficient mice are rejected when the host is replenished with T lymphocytes long after resolution of graft damage and of the resulting DAMPs [48–52]. Therefore, additional pathways that generate mature DCs in response to allotransplantation likely exist.

One possible mechanism is that DCs or their precursors distinguish between self and allogeneic non-self as they would between self and microbial non-self – a phenomenon referred to as “innate allorecognition” [43]. This possibility has been formally tested in the mouse. Zecher et al showed that injecting allogeneic RAG−/− splenocytes into the ear pinnae of RAG−/− recipients elicits significantly greater swelling and infiltration of the skin with host myeloid cells than injecting syngeneic splenocytes [52]. Depletion and cell transfer experiments established that the response is independent of NK cells and, instead, is mediated by monocytes. By performing heart, kidney, and bone marrow transplants into RAG−/−γc−/− mice, which lack T, B, and innate lymphoid cells including NK cells, Oberbarnscheidt et al provided direct evidence that detection of allogeneic non-self by monocytes is necessary for initiating alloimmunity [43]. In these experiments, allogeneic but not syngeneic grafts elicited persistent differentiation of monocytes to mature DC that express IL-12, stimulate T cell proliferation and IFN-γ production, and precipitate graft rejection. Conversely, host monocyte depletion prevented rejection. Thus, innate allorecognition by monocytes seems to be the key that unlocks the differentiation of monocytes to mature, IL-12-producing DCs after allotransplantation (Figure 1). Although danger clearly amplifies this innate response, it is not sufficient to initiate it.

Role of Host DCs in the Allograft: A Continuous Love Affair with the T Cell

Host DCs accumulate in the graft rapidly after transplantation, replacing donor-derived DCs, and persist throughout the life of the graft [53–55]. Which host cells the DCs derive from and their function in the alloimmune response, however, have remained unclear. Recently, our groups (Morelli & Lakkis) have shown in mouse heart and kidney allografts that the vast majority of host CD11c+ DCs that replace donor DCs within few days after transplantation have phenotypic and functional features of monocyte-derived DCs (mono-DC), that they originate from Ly6Clo (non-classical) host monocytes, and that they play a key role in allograft rejection [16, 56]. First, DCs in the allograft extend dendrites into the capillary lumina of renal allografts, capture effector T cells rolling along the endothelium, and mediate their transendothelial migration into the graft in a cognate Ag-dependent fashion [56]. Second, host mono-DCs continue to make extended cognate interactions with effector T cells that infiltrated the graft [16]. These interactions arrest alloantigen-specific effectors within the graft parenchyma, increase their proliferation, and reduce their apoptosis. Depletion of graft DCs successfully delays ongoing acute rejection and prevents rejection mediated by the transfer of effector T cells into the host. How intragraft DCs that are of host origin continue to activate and engage directly alloreactive effector T cells, which constitute the majority of effectors during the alloimmune response, is not known but is likely occurring via the semi-direct (cross-dressing) pathway of alloantigen presentation (see next section: “Alloantigen Presentation by Innate Immune Cells”). It is also conceivable that some of the graft DCs migrate back to secondary lymphoid tissues where they activate additional T cells [57], but this possibility remains to be formally tested. Recognition of allogeneic non-self by monocytes, described above, is an important factor behind the differentiation of host monocytes to mono-DCs in the graft. Therefore, host DCs continue to play an essential role in alloimmunity beyond the initiation phase by propagating the effector T cell response within the graft itself, leading to full-blown graft rejection. Moreover, host DC persistence and maturation in the graft is driven by innate allorecognition.

Both of the insights, innate allorecognition and extended function of host DCs in the graft, provide opportunities in the future to inhibit alloimmune responses in a cognate and potentially safe manner. The first raises the possibility that blocking the sensing mechanisms or the signaling pathways triggered by the recognition of allogeneic non-self by monocytes would constitute a novel therapeutic modality to prevent acute or chronic allograft rejection. It is known so far that initial sensing of allografts by monocytes is not dependent on MHC mismatch between the donor and recipient [43]. Instead, we (Lakkis et al) are currently exploring the possibility that SIRPα on donor tissues, which is a highly polymorphic molecule not linked to the MHC, is important for this innate allorecognition phenomenon. The second insight provides the prospect that inhibiting recipient monocyte migration to the graft or their differentiation into DCs could interrupt rejection even after T cell priming has already taken place in secondary lymphoid tissues. Indeed, Miller et al have shown that the number of intra-graft DCs directly correlates with the number of T cells that infiltrate the graft [58] and it has been show in tumor settings that intra-tumoral transfer of DCs promotes recruitment of T cells into the tumor and tumor rejection [59]. Preventing monocyte-dependent recruitment of T cells to the allograft is particularly relevant to memory T cells, which represent a substantial fraction of the alloreactive T cell repertoire in humans [60], and can be recalled and propagated by alloantigens in the graft [61].

Alloantigen Presentation by Innate Immune Cells

Following their microbiota-dependent poising and allogeneic non-self-dependent maturation, DCs still need to present alloantigen to alloreactive T cells for fullblown alloimmunity to ensue. Upon transplantation, release of DAMPs induced by the ischemia and reperfusion injury incurred by all transplanted organs promotes activation of graft-resident APCs, including conventional DCs. As a result, fully activated donor DCs migrate via blood or lymphatic vessels to secondary lymphoid organs [14].

It has been generally accepted that directly alloreactive naïve T cells recognize donor (intact) MHC molecules present on the surface of donor DCs mobilized to secondary lymphoid organs. Accumulating evidence, however, has challenged this dogma [62–66]. After transplantation of fully H2-mismatched skin or cardiac allografts in mice, donor-derived living DCs are detected at very low numbers in draining lymphoid organs [10, 57]. This is because donor passenger DCs have a limited lifespan and they are recognized as non-self and eliminated by the host NK cells [66, 67]. Indeed, homing of allogeneic DCs to lymph nodes triggers recruitment and activation of host NK cells that eliminate most of the allogeneic DCs [66, 68]. Host CD8 T effector cells recognizing non-self MHC-I molecules also kill allogeneic DCs mobilized to lymph nodes [69]. Besides, most allogeneic DCs that migrated to lymph nodes fail to form stable contacts with directly alloreactive CD4 T cells [66]. Importantly, lymphatic vessels, one of the main routes used by donor DCs to migrate out of the grafts, are sectioned during the transplantation procedure and do not fully reconnect with the recipient lymphatics until approximately one week after surgery [11]. These findings raise the question of how, in certain transplant models, the relatively few donor DCs detected in graft-draining lymphoid organs elicit so efficiently the directly alloreactive T-cell response that leads to acute rejection. This issue is particularly relevant in naïve hosts, in which the percentage of naïve T cells against donor MHC molecules is much lower than in pre-sensitized recipients with anti-donor and cross-reactive T-cell memory.

Numerous studies have shown that APCs can acquire MHC:peptide complexes from other leukocytes or endothelial cells [1, 70–73]. The transfer of MHC:peptide complexes and of other cell surface molecules between leukocytes has been dubbed cross-dressing, trogocytosis or cell nibbling. Following heart, kidney, or skin transplantation in mice, a percentage of host APCs in the draining lymphoid organs express donor-derived H2 molecules on the cell surface [10, 74, 75]. Also, the opposite transfer of host H2 molecules to donor DCs has been detected after bone marrow transplantation [76]. Transfer of donor MHC molecules, from donor passenger APCs or from the graft itself, to recipient APCs not only explains the semi-direct pathway, but also the efficient recognition of non-self MHC molecules by naïve T cells in the presence of extremely few donor passenger APCs, as 1 donor APC may transfer intact MHC molecules onto several host APCs. Recent evidence indicates that recipient APCs acquire donor intact MHC molecules through uptake of donor-derived extracellular vesicles (EVs) [10, 11].

Role of Extracellular Vesicles in Transplant Rejection

Leukocytes, including DCs, communicate through exchange of EVs, which differ in biogenesis, composition, and size. Microvesicles and apoptotic cell blebs are between 0.2–1 µm in size and are shed from the surface membrane of living and dying cells, respectively [77]. In contrast, exosomes are EVs of endocytic origin, between 70–120 nm in diameter. Exosomes are generated as intraluminal vesicles by reverse budding of the limiting membrane of late endosomes termed multi-vesicular bodies [77, 78]. Once the limiting membrane of the multivesicular bodies fuses with the plasma membrane, it releases to the intercellular space or bodily fluids its cargo of intraluminal vesicles, which are then termed exosomes. Most studies on transfer of MHC molecules between leukocytes have focused on exosomes whereas the role of other types of EVs in the passage of functional MHC antigen between cells is very limited.

The protein composition of the exosome membrane and its intraluminal cargo depends on the lineage and state of activation, transformation, or infection of the parent cell. Exosomes carry cell-specific antigens, heat shock proteins, MHC and cell adhesion molecules, cytokines, proteinases, cytoplasmic enzymes, signal transduction molecules, and molecules involved in exosome biogenesis. Exosomes also contain mRNAs, non-coding regulatory RNAs including microRNAs (miRNAs), and in some cases extra-chromosomal DNA [78]. Exosomes even have cell-independent ability to process precursor miRNAs into mature miRNAs [79].

The current view is that exosomes function as a device for horizontal dissemination of proteins, lipids, and RNAs [80]. Exosomes interact with cells via multiple ligand-receptor interactions. Exosomes may remain on the surface or be rapidly internalized by the target cell. Indirect evidence suggests that endocytosed exosomes fuse with the membrane of the endocytic vacuoles releasing their intraluminal cargo into the cytosol of the acceptor cells [81]. Thus, exosomes may “inject” their intraluminal cargo into the cytosol of the acceptor leukocytes, where the exosome-shuttled miRNAs regulate their target mRNAs [81, 82], and the exosome-derived mRNAs translate into proteins [83]. Exosomes released by activated DCs are enriched in donor MHC molecules, T cell costimulatory molecules, and adhesion molecules on the vesicle surface [84, 85]. Although at high concentration APC-derived exosomes can function as antigen-presenting vesicles for T cell clones, lines, and primed T cells, their ability to stimulate naïve T cell is limited [78]. Such capacity, nevertheless, increases substantially when the exosomes are bound to DCs [85].

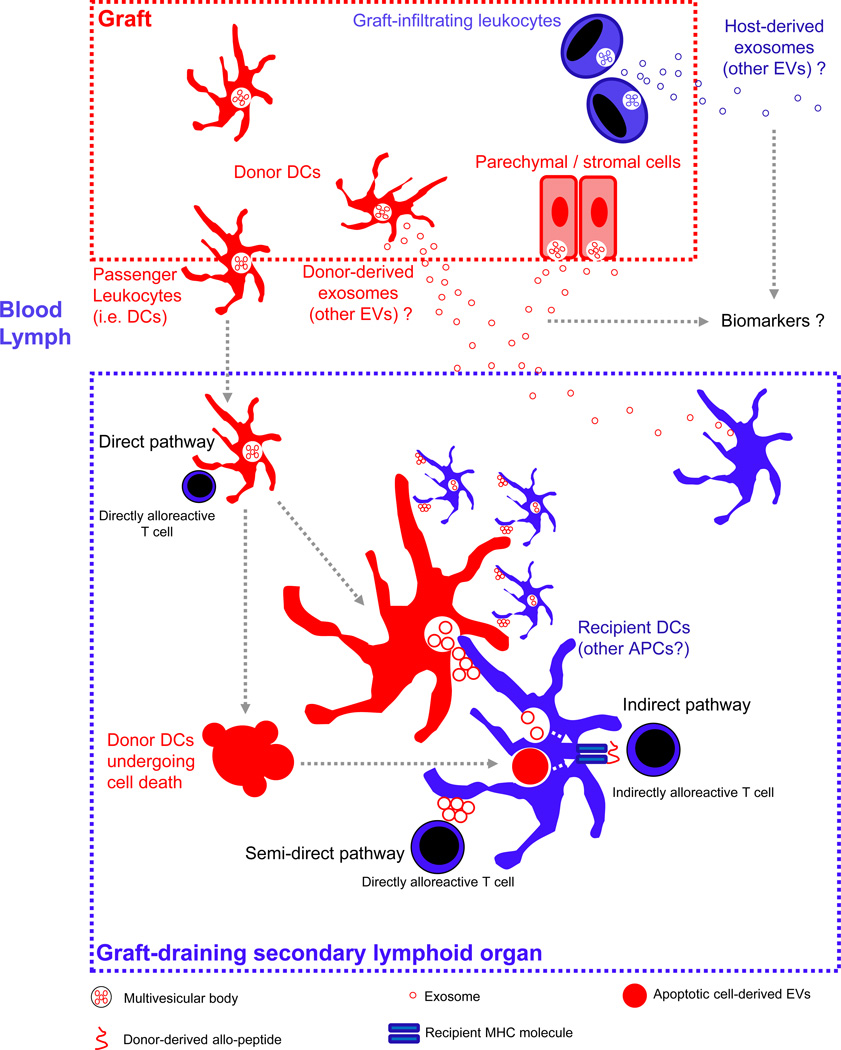

After transplantation of fully H2-disparate heart or skin grafts in non-allosensitized mice, the relatively few donor migrating DCs that reach the lymphoid organs, and likely the graft itself, transfer clusters of exosomes carrying donor H2 molecules and APC-activating signals to a high number of host APCs (Figure 2) [10, 11]. Indeed, the quantity of recipient DCs bearing donor H2 molecules was approximately 100-fold higher that the number of donor passenger DCs detected in the graft-draining lymphoid organ at the same time. The clusters of donor-derived exosomes remained attached to the host DCs for presentation of donor H2 molecules to direct pathway CD8 T cells via the semi-direct pathway, or were internalized for processing and presentation of the resulting donor H2-derived allopeptides to indirect pathway CD4 T cells (Figure 2) [10, 11]. Importantly, uptake of exosomes released by fully-activated donor DCs promoted activation of the host DCs, perhaps because exosomes from activated DCs bear high content of heat shock proteins and mir-155 that are potent inducers of DC activation [81, 86]. Interestingly, exosomes released by mast cells, erythrocytes, or infected macrophages also promote DC activation [87–89]. In accordance to a role of the recipient DCs in presentation of donor MHC molecules acquired via donor-derived exosomes, depletion of host DCs after heart transplantation reduced presentation of donor H2 molecules to directly alloreactive T cells, and delayed acute rejection [10]. These findings unveil a dual role for the passage donor-derived exosomes in graft rejection, first, as the elusive ultrastructural basis behind the semi-direct pathway, and second, as a mechanism of amplification for presentation of non-self MHC molecules to T cells in lymphoid organs during allosensitization.

Figure 2. Role of Extracellular Vesicles in Transplantation.

The donor is represented in red and the recipient in blue. After transplantation, donor-derived passenger antigen-presenting cells (APCs) (i.e. dendritic cells, DCs) migrate to the graft-draining lymphoid tissues, where they present donor MHC molecules to directly alloreactive T cells (i.e. direct pathway), or transfer clusters of donor exosomes (and likely other extracellular vesicles, EVs) bearing donor MHC molecules to recipient APCs. Transfer of clusters of donor exosomes bearing MHC molecules and APC-activating signals from relatively few donor migrating DCs to a higher number of recipient APCs amplifies T-cell allosensitization, and is the basis of the semi-direct pathway of allorecognition by T cells. Alternatively, EVs carrying donor MHC molecules and released by the allograft itself into blood or lymph could be a source of donor MHC molecules for recipients APCs residing in graft-draining lymphoid tissues. Donor-derived exosomes and EVs derived from donor migrating APCs undergoing apoptosis are also internalized for processing into donor-derived peptides for presentation to T cells through the indirect pathway of allorecognition. EVs released by the allograft or by graft-infiltrating leukocytes into systemic blood or bodily fluids (e.g. urine) constitute promising protein or RNA biomarkers.

Exosome-like EVs have also been shown to induce auto-antibodies involved in allograft vascular rejection. Serum-deprived endothelial cells release, besides apoptotic cell-derived vesicles, exosome-like EVs enriched in the LG3 fragment of the vascular extracellular matrix protein perlecam [90]. Repetitive injection of these endothelial-derived exosome-like EVs, unlike infusion of apoptotic cell vesicles from the same parent cells, triggers production of antibodies against the auto-antigen LG3 and aggravate vascular rejection in mice [90].

Extracellular Vesicles as Therapeutic Tools and Biomarkers in Transplantation

Donor-derived exosomes may facilitate recognition of the allograft as non-self, but exosomes have also been shown to delay allograft rejection in some settings. Systemic administration of donor-derived exosomes produced by immature DCs plus suboptimal pharmacologic immunosuppression decreased the anti-donor response and prolonged survival of cardiac and intestinal allografts in murine models [91–93]. In such studies, however, whether the donor-specific immunosuppression was due to intrinsic properties of the donor-derived EVs, or simply to a donor-specific transfusion effect caused by delivering donor antigen through a pro-tolerogenic route (i.v.) was not explored. There is evidence that some of the immunosuppressive effects of mesenchymal stem cells are mediated by secreted factors, including EVs. Repetitive administration of exosome-enriched fractions from culture supernatants of mesenchymal stem cells, bearing high amounts of IL-10, TFG-β and HLA-G, improved the symptoms in one patient with refractory graft-versus-host disease [94].

Although these studies provide evidence for the potential use of immunosuppressive exosomes or other EVs in the clinic, the mechanisms by which certain types of exosomes regulate the immune response remain mostly unknown. Interestingly, exosomes released by CD4 Foxp3 regulatory T (Treg) cells express CD73, an ecto-enzyme that generates the immune-suppressive nucleoside adenosine [95]. Such exosomes suppressed proliferation and IL-2 and IFN-γ secretion in CD4 T cells in vitro [95]. Through exosome-mediated transfer of Let-7d miRNA, CD4 Foxp3 Treg cells reduce Th1 proliferation and IFN-γ secretion, and suppress pathogenic Th1 cell-mediated systemic disease in mice [96]. In a transplantation model, repetitive i.v. administration of exosomes purified from cultures of donor or recipient polyclonal CD4 Treg cells prolonged survival of kidney allografts in rats [97]. Although these findings are promising for future exosome-based immunosuppressive therapies, the extreme dilution in plasma of the injected EVs and their rapid clearance from circulation by phagocytes are critical hurdles for their clinical applicability.

Exosomes isolated from bodily fluids represent potential protein and RNA biomarkers (Figure 2). Urine EVs, including exosomes, carry proteins derived from glomerular, tubular, prostate and bladder cells, and have been investigated as biomarkers for various kidney diseases [98]. The content of exosomes in urine augments throughout the first week after kidney transplantation [99]. In patients with delayed graft function, the levels in urine of exosome-associated neutrophil gelatinase-associated lipocalin (NGAL) are higher than those in recipients without such complication [100]. In contrast, the amounts of mRNAs for biomarkers of renal cellular injury found in urine exosomes correlate poorly with the clinical outcome of renal transplantation [99]. Exosomes isolated from sera and bronchoalveolar lavage fluid of patients undergoing acute or chronic rejection of lung allografts carry high content of collagen-V, a lung-associated self-antigen involved in lung allograft rejection [101]. Importantly, exosomes bearing high levels of collagen-V were detectable before clinical diagnosis of lung rejection [101], suggesting they could be used as predictive biomarkers.

Concluding Remarks

Innate immune cells are essential to activate alloreactive T cells following transplantation but it is now apparent that their activating capacity is modulated not only after, but also already before transplantation. Licensing of innate immune cells by the microbiota before transplantation and their activation by allogeneic non-self molecules expressed on donor cells after transplantation establish their activation threshold and differentiation status for subsequent alloreactive T cell priming. Concurrently, capture of donor exosomes and alloantigen processing by host DCs provide the epitopes necessary for initiation of adaptive alloimmunity. Many outstanding questions remain to be investigated (see Outstanding Questions). In particular, the role of the microbiota after transplantation and the precise mechanisms linking commensal microbes outside body barriers to modulation of alloimmunity inside the body need to be clarified. In addition, the allogeneic non-self determinants that need to be recognized by innate cells to promote their maturation and whether they can be masked to promote graft acceptance needs to be further pursued. Finally, whether release and capture of exosomes can be manipulated therapeutically to reduce allorecognition should be investigated. Resolving these and other questions will bring us one step closer to improving transplant outcome in the clinic.

Outstanding Questions Box.

What is the fate of effector T cells that make extended, cognate contacts with DCs in the graft? Are they more likely to become potent, short-lived effectors or long-lived memory cells?

Role of the microbiota in transplantation

What is the impact of the microbiota after transplantation?

Do different commensal species tune innate immune cells differently and how does assembly of microbial communities change these effects?

What are the molecular determinants by which the microbiota tunes innate immune cells?

Are there immunosuppressive commensals that could promote graft acceptance?

Do organ-specific commensals tune innate immune cells locally or systemically?

Role of the microbiota in transplantation

What are the molecular determinants and mechanisms of allogeneic non-self recognition by innate immune cells?

Extracellular vesicles and transplantation

Does organ colonization alter the rate, number or quality of exosomes and other EVs produced by donor DCs?

Are donor-derived EVs released mainly by the relatively few donor passenger APCs that reach the graft-draining lymphoid tissues, by the graft itself, or by both, and if released by the graft how do they avoid extreme dilution in the systemic circulation and rapid clearance by phagocytes?

What is the nature of the APC-activating signals delivered by donor exosomes, and other EVs?

Will future methodologies for the use of EVs as biomarkers be able to isolate EVs released exclusively by the graft or graft-infiltrating cells, and distinguish them from “background” EVs produced by host tissues?

What is the effect of immunosuppressive therapies on the release and capture of exosomes and other EVs, and can capture of donor EVs by host DCs be blocked to limit presentation of alloantigens?

Trends Box.

The composition of the microbiota tunes innate immune cells to establish their threshold of activation of adaptive alloimmunity

Non-self recognition of mammalian determinants encoded by non-MHC genes in allogeneic grafts initiates activation and differentiation of host mononuclear phagocytes

Capture of donor exosomes by host DCs amplifies activation of direct and indirect pathways T cells and is a major pathway for priming adaptive alloimmunity

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH RO1s AI115716 to M.-L.A, AI049466 and AI099465 to F.G.L. and HL130191 to A.E.M.

Glossary Box

- Alloantigen

polymorphic molecule for which a variant expressed by donor cells can be recognized by the adaptive immune system

- Allograft

an organ transplanted between genetically distinct individuals of the same species

- Allopeptide

a peptide derived from a polymorphic region of an alloantigen

- Alloreactive

ability to recognize an alloantigen

- Allorecognition

sensing of allogeneic non-self by either innate or adaptive immune cells

- Direct pathway

presentation of intact donor MHC molecule by a donor cell to a T cell

- Exosomes

nanovesicles generated in the endocytic compartment of most cell types, and released to the extracellular space or bodily fluids by fusion of multivesicular bodies with the cell membrane

- Extracellular vesicles

generic name given to all membrane vesicles derived from cells, including microvesicles shed from the cell surface, exosomes released from the endocytic compartment and apoptotic cell-derived vesicles

- Indirect pathway

presentation of an allopeptide by host MHC molecules to a T cell

- Microbiota

the combination of microbes that colonize a habitat

- Minor mismatch

a polymorphism in a non-MHC-encoded gene that can give rise to an allopeptide

- Semi-direct pathway

presentation by host APCs of intact captured donor MHC molecules

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Herrera OB, et al. A novel pathway of alloantigen presentation by dendritic cells. J Immunol. 2004;173(8):4828–4837. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.8.4828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lee RS, et al. Indirect recognition by helper cells can induce donor-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes in vivo. J Exp Med. 1994;179(3):865–872. doi: 10.1084/jem.179.3.865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wise MP, et al. Linked suppression of skin graft rejection can operate through indirect recognition. J Immunol. 1998;161(11):5813–5816. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sivaganesh S, et al. Copresentation of intact and processed MHC alloantigen by recipient dendritic cells enables delivery of linked help to alloreactive CD8 T cells by indirect-pathway CD4 T cells. J Immunol. 2013;190(11):5829–5838. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1300458. Epub 2013 Apr 29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Suchin EJ, et al. Quantifying the frequency of alloreactive T cells in vivo: new answers to an old question. J Immunol. 2001;166(2):973–981. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.2.973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Benichou G, et al. Limited T cell response to donor MHC peptides during allograft rejection. Implications for selective immune therapy in transplantation. J Immunol. 1994;153(3):938–945. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Auchincloss H, Jr, et al. The role of ‘indirect’ recognition in initiating rejection of skin grafts from major histocompatibility complex class II-deficient mice. Proc.Natl.Acad.Sci.USA. 1993;90:3373–3377. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.8.3373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Illigens BM, et al. The relative contribution of direct and indirect antigen recognition pathways to the alloresponse and graft rejection depends upon the nature of the transplant. Hum Immunol. 2002;63(10):912–925. doi: 10.1016/s0198-8859(02)00449-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Baker RJ, et al. Loss of direct and maintenance of indirect alloresponses in renal allograft recipients: implications for the pathogenesis of chronic allograft nephropathy. J Immunol. 2001;167(12):7199–7206. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.12.7199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liu Q, et al. Donor dendritic cell-derived exosomes promote allograft-targeting immune response. J Clin Invest. 2016;126(8):2805–2820. doi: 10.1172/JCI84577. Epub 2016 Jun 27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Marino JM, et al. Donor exosomes rather than passenger leukocytes initiate alloreactive T cell responses after transplantation. Science Immunology. 2016;1(1):aaf8759. doi: 10.1126/sciimmunol.aaf8759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Felix NJ, Allen PM. Specificity of T-cell alloreactivity. Nat Rev Immunol. 2007;7(12):942–953. doi: 10.1038/nri2200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Geissmann F, et al. Development of monocytes, macrophages, and dendritic cells. Science. 2010;327(5966):656–661. doi: 10.1126/science.1178331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Morelli AE. Dendritic cells of myeloid lineage: the masterminds behind acute allograft rejection. Curr Opin Organ Transplant. 2014;19(1):20–27. doi: 10.1097/MOT.0000000000000039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ochando J, et al. The Mononuclear Phagocyte System in Organ Transplantation. Am J Transplant. 2016;16(4):1053–1069. doi: 10.1111/ajt.13627. Epub 2016 Jan 28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhuang Q, et al. Graft-infiltrating host dendritic cells play a key role in organ transplant rejection. Nat Commun. 2016;7:12623. doi: 10.1038/ncomms12623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ochando JC, et al. Alloantigen-presenting plasmacytoid dendritic cells mediate tolerance to vascularized grafts. Nat Immunol. 2006;7(6):652–662. doi: 10.1038/ni1333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lei YM, et al. The composition of the microbiota modulates allograft rejection. J Clin Invest. 2016;126(7):2736–2744. doi: 10.1172/JCI85295. Epub 2016 Jun 20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sivan A, et al. Commensal Bifidobacterium promotes antitumor immunity and facilitates anti-PD-L1 efficacy. Science. 2015;350(6264):1084–1089. doi: 10.1126/science.aac4255. Epub 2015 Nov 5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ichinohe T, et al. Microbiota regulates immune defense against respiratory tract influenza A virus infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108(13):5354–5359. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1019378108. Epub 2011 Mar 14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Abt MC, et al. Commensal bacteria calibrate the activation threshold of innate antiviral immunity. Immunity. 2012;37(1):158–170. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.04.011. Epub 2012 Jun 14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ganal SC, et al. Priming of natural killer cells by nonmucosal mononuclear phagocytes requires instructive signals from commensal microbiota. Immunity. 2012;37(1):171–186. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.05.020. Epub 2012 Jun 28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Smith PM, et al. The microbial metabolites, short-chain fatty acids, regulate colonic Treg cell homeostasis. Science. 2013;341(6145):569–573. doi: 10.1126/science.1241165. Epub 2013 Jul 4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Furusawa Y, et al. Commensal microbe-derived butyrate induces the differentiation of colonic regulatory T cells. Nature. 2013;504(7480):446–450. doi: 10.1038/nature12721. Epub 2013 Nov 13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Arpaia N, et al. Metabolites produced by commensal bacteria promote peripheral regulatory T-cell generation. Nature. 2013;504(7480):451–455. doi: 10.1038/nature12726. Epub 2013 Nov 13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kaparakis-Liaskos M, Ferrero RL. Immune modulation by bacterial outer membrane vesicles. Nat Rev Immunol. 2015;15(6):375–387. doi: 10.1038/nri3837. Epub 2015 May 15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chu H, et al. Gene-microbiota interactions contribute to the pathogenesis of inflammatory bowel disease. Science. 2016;352(6289):1116–1120. doi: 10.1126/science.aad9948. Epub 2016 May 5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Seo SU, et al. Distinct Commensals Induce Interleukin-1beta via NLRP3 Inflammasome in Inflammatory Monocytes to Promote Intestinal Inflammation in Response to Injury. Immunity. 2015;42(4):744–755. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2015.03.004. Epub 2015 Apr 7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bain CC, et al. Constant replenishment from circulating monocytes maintains the macrophage pool in the intestine of adult mice. Nat Immunol. 2014;15(10):929–937. doi: 10.1038/ni.2967. Epub 2014 Aug 24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McKay D, et al. Simultaneous deletion of MyD88 and Trif delays major histocompatibility and minor antigen mismatch allograft rejection. Eur J Immunol. 2006;36(8):1994–2002. doi: 10.1002/eji.200636249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Goldstein DR, et al. Critical role of the Toll-like receptor signal adaptor protein MyD88 in acute allograft rejection. J Clin Invest. 2003;111(10):1571–1578. doi: 10.1172/JCI17573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang J, et al. Bacterial colonization dampens influenza-mediated acute lung injury via induction of M2 alveolar macrophages. Nat Commun. 2106;4 doi: 10.1038/ncomms3106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Diehl GE, et al. Microbiota restricts trafficking of bacteria to mesenteric lymph nodes by CX(3)CR1(hi) cells. Nature. 2013;494(7435):116–120. doi: 10.1038/nature11809. Epub 2013 Jan 13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Findley K, et al. Topographic diversity of fungal and bacterial communities in human skin. Nature. 2013;498(7454):367–370. doi: 10.1038/nature12171. Epub 2013 May 22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Naik S, et al. Commensal-dendritic-cell interaction specifies a unique protective skin immune signature. Nature. 2015;520(7545):104–108. doi: 10.1038/nature14052. Epub 2015 Jan 5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Naik S, et al. Compartmentalized control of skin immunity by resident commensals. Science. 2012;337(6098):1115–1119. doi: 10.1126/science.1225152. Epub 2012 Jul 26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Oh PL, et al. Characterization of the ileal microbiota in rejecting and nonrejecting recipients of small bowel transplants. Am J Transplant. 2012;12(3):753–762. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2011.03860.x. Epub 2011 Dec 7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Weigt SS, et al. Colonization with small conidia Aspergillus species is associated with bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome: a two-center validation study. Am J Transplant. 2013;13(4):919–927. doi: 10.1111/ajt.12131. Epub 2013 Feb 7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Willner DL, et al. Reestablishment of Recipient-associated Microbiota in the Lung Allograft Is Linked to Reduced Risk of Bronchiolitis Obliterans Syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;187(6):640–647. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201209-1680OC. Epub 2013 Jan 17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lechler RI, Batchelor JR. Restoration of immunogenicity to passenger cell-depleted kidney allografts by the addition of donor strain dendritic cells. J Exp Med. 1982;155(1):31–41. doi: 10.1084/jem.155.1.31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lakkis FG, et al. Immunologic ‘ignorance’ of vascularized organ transplants in the absence of secondary lymphoid tissue. Nat Med. 2000;6(6):686–688. doi: 10.1038/76267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sporri R, Reis e Sousa C. Inflammatory mediators are insufficient for full dendritic cell activation and promote expansion of CD4+ T cell populations lacking helper function. Nat Immunol. 2005;6(2):163–170. doi: 10.1038/ni1162. Epub 2005 Jan 16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Oberbarnscheidt MH, et al. Non-self recognition by monocytes initiates allograft rejection. J Clin Invest. 2014;124(8):3579–3589. doi: 10.1172/JCI74370. Epub 2014 Jul 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tesar BM, et al. TH1 immune responses to fully MHC mismatched allografts are diminished in the absence of MyD88, a toll-like receptor signal adaptor protein. Am J Transplant. 2004;4(9):1429–1439. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2004.00544.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hutton MJ, et al. Islet allograft rejection is independent of toll-like receptor signaling in mice. Transplantation. 2009;88(9):1075–1080. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e3181bd3fe2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Oberbarnscheidt MH, et al. Type I interferons are not critical for skin allograft rejection or the generation of donor-specific CD8+ memory T cells. Am J Transplant. 2010;10(1):162–167. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2009.02871.x. Epub 2009 Nov 24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Li H, et al. Graft-versus-host disease is independent of innate signaling pathways triggered by pathogens in host hematopoietic cells. J Immunol. 2011;186(1):230–241. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1002965. Epub 2010 Nov 22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bingaman AW, et al. Vigorous allograft rejection in the absence of danger. J Immunol. 2000;164(6):3065–3071. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.6.3065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Anderson CC, et al. Testing time-, ignorance-, and danger-based models of tolerance. J Immunol. 2001;166(6):3663–3671. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.6.3663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Anderson CC, Matzinger P. Immunity or tolerance: opposite outcomes of microchimerism from skin grafts. Nat Med. 2001;7(1):80–87. doi: 10.1038/83393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Chan WF, et al. The ability of natural tolerance to be applied to allogeneic tissue: determinants and limits. Biol Direct. 2007;2:10. doi: 10.1186/1745-6150-2-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zecher D, et al. An innate response to allogeneic nonself mediated by monocytes. J Immunol. 2009;183(12):7810–7816. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0902194. Epub. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Grau V, et al. Dynamics of monocytes/macrophages and T lymphocytes in acutely rejecting rat renal allografts. Cell Tissue Res. 1998;291(1):117–126. doi: 10.1007/s004410050985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Penfield JG, et al. Transplant surgery injury recruits recipient MHC class II-positive leukocytes into the kidney. Kidney Int. 1999;56(5):1759–1769. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.1999.00741.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Saiki T, et al. Trafficking of host- and donor-derived dendritic cells in rat cardiac transplantation: allosensitization in the spleen and hepatic nodes. Transplantation. 2001;71(12):1806–1815. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200106270-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Walch JM, et al. Cognate antigen directs CD8+ T cell migration to vascularized transplants. J Clin Invest. 2013;123(6):2663–2671. doi: 10.1172/JCI66722. Epub 2013 May 15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Celli S, et al. Visualizing the innate and adaptive immune responses underlying allograft rejection by two-photon microscopy. Nat Med. 2011;17(6):744–749. doi: 10.1038/nm.2376. Epub 2011 May 15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Miller ML, et al. Adoptive transfer of tracer alloreactive CD4+ TCR-transgenic T cells alters the endogenous immune response to an allograft. Am J Transplant. 2016:13821. doi: 10.1111/ajt.13821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Spranger S, et al. Melanoma-intrinsic beta-catenin signalling prevents anti-tumour immunity. Nature. 2015;523(7559):231–235. doi: 10.1038/nature14404. Epub 2015 May 11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Macedo C, et al. Contribution of naive and memory T-cell populations to the human alloimmune response. Am J Transplant. 2009;9(9):2057–2066. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2009.02742.x. Epub 2009 Jul 16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Chalasani G, et al. Recall and propagation of allospecific memory T cells independent of secondary lymphoid organs. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99(9):6175–6180. doi: 10.1073/pnas.092596999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Chen Y, et al. The male minor transplantation antigen preferentially activates recipient CD4+ T cells through the indirect presentation pathway in vivo. J Immunol. 2003;171(12):6510–6518. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.12.6510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Brennan TV, et al. Preferential priming of alloreactive T cells with indirect reactivity. Am J Transplant. 2009;9(4):709–718. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2009.02578.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zheng XX, et al. The role of donor and recipient B7-1 (CD80) in allograft rejection. J Immunol. 1997;159(3):1169–1173. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Mandelbrot DA, et al. Expression of B7 molecules in recipient, not donor, mice determines the survival of cardiac allografts. J Immunol. 1999;163(7):3753–3757. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Garrod KR, et al. NK cell patrolling and elimination of donor-derived dendritic cells favor indirect alloreactivity. J Immunol. 2010;184(5):2329–2336. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0902748. Epub 2010 Feb 5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Yu G, et al. NK cells promote transplant tolerance by killing donor antigen-presenting cells. J Exp Med. 2006;203(8):1851–1858. doi: 10.1084/jem.20060603. Epub 2006 Jul 24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Laffont S, et al. Natural killer cells recruited into lymph nodes inhibit alloreactive T-cell activation through perforin-mediated killing of donor allogeneic dendritic cells. Blood. 2008;112(3):661–671. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-10-120089. Epub 2008 May 27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Laffont S, et al. CD8+ T-cell-mediated killing of donor dendritic cells prevents alloreactive T helper type-2 responses in vivo. Blood. 2006;108(7):2257–2264. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-10-4059. Epub 2006 Jan 31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Wakim LM, Bevan MJ. Cross-dressed dendritic cells drive memory CD8+ T-cell activation after viral infection. Nature. 2011;471(7340):629–632. doi: 10.1038/nature09863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Smyth LA, et al. Acquisition of MHC:peptide complexes by dendritic cells contributes to the generation of antiviral CD8+ T cell immunity in vivo. J Immunol. 2012;189(5):2274–2282. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1200664. Epub 2012 Jul 20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Zhang QJ, et al. Trogocytosis of MHC-I/peptide complexes derived from tumors and infected cells enhances dendritic cell cross-priming and promotes adaptive T cell responses. PLoS One. 2008;3(8):e3097. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Harshyne LA, et al. Dendritic cells acquire antigens from live cells for cross-presentation to CTL. J Immunol. 2001;166(6):3717–3723. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.6.3717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Brown K, et al. Extensive and bidirectional transfer of major histocompatibility complex class II molecules between donor and recipient cells in vivo following solid organ transplantation. FASEB J. 2008;22(11):3776–3784. doi: 10.1096/fj.08-107441. Epub 2008 Jul 16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Brown K, et al. Coexpression of donor peptide/recipient MHC complex and intact donor MHC: evidence for a link between the direct and indirect pathways. Am J Transplant. 2011;11(4):826–831. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2011.03437.x. Epub 2011 Mar 14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Markey KA, et al. Cross-dressing by donor dendritic cells after allogeneic bone marrow transplantation contributes to formation of the immunological synapse and maximizes responses to indirectly presented antigen. J Immunol. 2014;192(11):5426–5433. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1302490. Epub 2014 Apr 30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Colombo M, et al. Biogenesis, secretion, and intercellular interactions of exosomes and other extracellular vesicles. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2014;30:255–289. doi: 10.1146/annurev-cellbio-101512-122326. Epub 2014 Aug 21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Robbins PD, Morelli AE. Regulation of immune responses by extracellular vesicles. Nat Rev Immunol. 2014;14(3):195–208. doi: 10.1038/nri3622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Melo SA, et al. Cancer exosomes perform cell-independent microRNA biogenesis and promote tumorigenesis. Cancer Cell. 2014;26(5):707–721. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2014.09.005. Epub 2014 Oct 23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Tkach M, Thery C. Communication by Extracellular Vesicles: Where We Are and Where We Need to Go. Cell. 2016;164(6):1226–1232. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.01.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Montecalvo A, et al. Mechanism of transfer of functional microRNAs between mouse dendritic cells via exosomes. Blood. 2012;119(3):756–766. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-02-338004. Epub 2011 Oct 26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Mittelbrunn M, et al. Unidirectional transfer of microRNA-loaded exosomes from T cells to antigen-presenting cells. Nat Commun. 2011;2:282. doi: 10.1038/ncomms1285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Valadi H, et al. Exosome-mediated transfer of mRNAs and microRNAs is a novel mechanism of genetic exchange between cells. Nat Cell Biol. 2007;9(6):654–659. doi: 10.1038/ncb1596. Epub 2007 May 7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Segura E, et al. ICAM-1 on exosomes from mature dendritic cells is critical for efficient naive T-cell priming. Blood. 2005;106(1):216–223. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-01-0220. Epub 2005 Mar 24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Montecalvo A, et al. Exosomes as a short-range mechanism to spread alloantigen between dendritic cells during T cell allorecognition. J Immunol. 2008;180(5):3081–3090. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.5.3081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Thery C, et al. Molecular characterization of dendritic cell-derived exosomes. Selective accumulation of the heat shock protein hsc73. J Cell Biol. 1999;147(3):599–610. doi: 10.1083/jcb.147.3.599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Skokos D, et al. Mast cell-derived exosomes induce phenotypic and functional maturation of dendritic cells and elicit specific immune responses in vivo. J Immunol. 2003;170(6):3037–3045. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.6.3037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Danesh A, et al. Exosomes from red blood cell units bind to monocytes and induce proinflammatory cytokines, boosting T-cell responses in vitro. Blood. 2014;123(5):687–696. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-10-530469. Epub 2013 Dec 12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Bhatnagar S, et al. Exosomes released from macrophages infected with intracellular pathogens stimulate a proinflammatory response in vitro and in vivo. Blood. 2007;110(9):3234–3244. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-03-079152. Epub 2007 Jul 31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Dieude M, et al. The 20S proteasome core, active within apoptotic exosome-like vesicles, induces autoantibody production and accelerates rejection. Sci Transl Med. 2015;7(318):318ra200. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aac9816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Peche H, et al. Induction of tolerance by exosomes and short-term immunosuppression in a fully MHC-mismatched rat cardiac allograft model. Am J Transplant. 2006;6(7):1541–1550. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2006.01344.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Li X, et al. Tolerance induction by exosomes from immature dendritic cells and rapamycin in a mouse cardiac allograft model. PLoS One. 2012;7(8):e44045. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0044045. Epub 2012 Aug 29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Yang X, et al. Exosomes derived from immature bone marrow dendritic cells induce tolerogenicity of intestinal transplantation in rats. J Surg Res. 2011;171(2):826–832. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2010.05.021. Epub 2010 Jun 8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Kordelas L, et al. MSC-derived exosomes: a novel tool to treat therapy-refractory graft-versus-host disease. Leukemia. 2014;28(4):970–973. doi: 10.1038/leu.2014.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Smyth LA, et al. CD73 expression on extracellular vesicles derived from CD4+ CD25+ Foxp3+ T cells contributes to their regulatory function. Eur J Immunol. 2013;43(9):2430–2440. doi: 10.1002/eji.201242909. Epub 2013 Jul 15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Okoye IS, et al. MicroRNA-containing T-regulatory-cell-derived exosomes suppress pathogenic T helper 1 cells. Immunity. 2014;41(1):89–103. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.05.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Yu X, et al. CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells-derived exosomes prolonged kidney allograft survival in a rat model. Cell Immunol. 2013;285(1–2):62–68. doi: 10.1016/j.cellimm.2013.06.010. Epub 2013 Jun 28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Salih M, et al. Urinary extracellular vesicles and the kidney: biomarkers and beyond. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2014;306(11):F1251–F1259. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00128.2014. Epub 2014 Apr 2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Peake PW, et al. A comparison of the ability of levels of urinary biomarker proteins and exosomal mRNA to predict outcomes after renal transplantation. PLoS One. 2014;9(2):e98644. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0098644. eCollection 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Alvarez S, et al. Urinary exosomes as a source of kidney dysfunction biomarker in renal transplantation. Transplant Proc. 2013;45(10):3719–3723. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2013.08.079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Gunasekaran M, et al. Donor-Derived Exosomes With Lung Self-Antigens in Human Lung Allograft Rejection. Am J Transplant. 2016:13915. doi: 10.1111/ajt.13915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]