The recently updated World Health Organization (WHO) consolidated guidelines on the use of antiretroviral therapy (ART) recommending to “treat all” mark a paradigm shift in the delivery of HIV treatment: from who is eligible and when to start ART, to how to provide client-centred and high-quality care to all people living with HIV (PLHIV). As part of this shift, the new guidance includes service delivery recommendations based on a “differentiated care framework” [1]. Yet, despite the increased global attention paid to differentiated care [2–4], the concept is not well defined.

There is broad agreement that a “one-size-fits-all” model of HIV services will not succeed in providing sustainable access to ART and support services for the 37 million PLHIV today. Instead, health systems will need to both accelerate ART initiation and support retention and viral suppression, which requires adapting HIV services to specific client populations and contexts [5]. Past discussions have looked at differentiated care through a health system's lens – focusing on what aspects of care are needed, how often they are needed, where care should be delivered and who will provide it [6]. An approach to HIV testing, care and treatment that distinguishes client groups according to broad definitions, however, is more likely to succeed.

Differentiated care is a client-centred approach that simplifies and adapts HIV services across the cascade, in ways that both serve the needs of PLHIV better and reduce unnecessary burdens on the health system. Differentiated care incorporates concepts such as simplification, task shifting and decentralization, which have also been called “community-based care, optimized care, patient-centred/focussed care, needs-based care [and] tiered care” [6]. The health system implications of this client-centred approach are clear: when a health system adopts a more responsive model of care, tailored to the needs of various groups of PLHIV, it can allocate resources more effectively, provide better access for underserved populations and deliver care in ways to improve quality of care and life. While differentiated approaches are often more cost-effective in an environment where funding for HIV is under threat, it is critical to ensure that the primary focus for differentiating care remains to improve quality rather than to prop up a misleading “more with less” agenda.

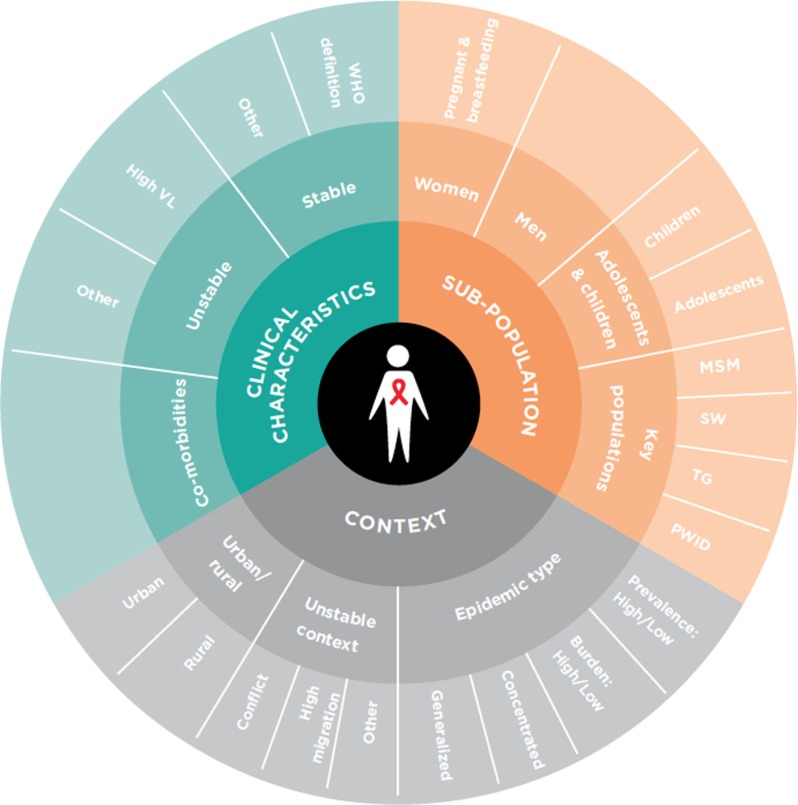

Well-known models of differentiated care have focused on ART delivery to clients who are clinically stable and have largely been implemented in high-prevalence countries in sub-Saharan Africa. Examples include client-managed groups (e.g. community adherence groups in Mozambique [7]), health care worker-managed groups (e.g. adherence clubs in South Africa [8]), facility-based individual delivery (e.g. “fast track” ART refills in Malawi [9]) and out-of-facility individual delivery (e.g. community drug distribution points in Uganda [10]). To succeed, however, differentiated care must not be limited to stable client models or solely to ART delivery. Policymakers and implementers should “differentiate” care for defined groups according to three elements as defined in Figure 1: (1) clinical characteristics; (2) sub-population; and (3) context [11]. Examples of differentiated care can be found across the cascade and the three elements including expanded PrEP access for sex workers in South Africa [12], a “one-window” approach for people who use drugs in Ukraine [13], targeted peer-led testing of key populations in Thailand [14] and in low-prevalence settings with stable client delivery models in Myanmar [15].

Figure 1.

Beyond stable clients: service delivery should be differentiated considering three elements [11].

Differentiated care is also a rights-based approach that can act as a modality of stigma and discrimination reduction irrespective of whether or not those rights are formally recognized in laws [16]. By considering the context of the client and health system, differentiated care can help to address policy barriers related to who can dispense versus distribute ART and who can conduct HIV testing. In addition, implementation, particularly at the national level, affords significant opportunities to confront legal and structural barriers that prevent underserved client groups from accessing services [17]. While national policies endorsing differentiated care are necessary for scale-up of HIV services, successful implementation will be dependent on an enabling environment inclusive of a robust drug supply (including fast tracked drug pick-ups and 3–6 month ART refills); access to laboratory monitoring, in particular viral load; a reliable monitoring and evaluation system; and recognition of lay workers. Achieving and sustaining these high-quality services also requires an empowered PLHIV community and civil society. Together, these bodies can advocate and create demand for services that are best tailored to the needs of clients in a given context.

The release of the new WHO guidelines add to the momentum around differentiated care, as evidenced by PEPFAR's Technical Considerations and the Global Fund's toolkit [3, 4] and provide opportunities to reimagine, reorganize and scale up client-centred approaches to HIV service delivery at the national level [1]. The inclusion of differentiated care also catalyses long-standing efforts of rights and community advocates to provide holistic and supportive care, particularly to underserved client groups [18].

Thirty-seven million PLHIV worldwide need lifelong ART. To achieve this, countries must adopt and adapt existing models of differentiated care to meet both the diverse needs of PLHIV and the capacity and constraints of their health systems. To ensure sustainability, successful programmes must be supported by national policies and be adequately funded. The impact of the scale-up of differentiated care models should be evaluated with clear indicators, including quality and outcomes of care, client and health care worker satisfaction, and costs to both the client and the health system. As the models are implemented and improved through analysis of programme data, quality improvement mechanisms and implementation research, stakeholders can work together to address the priority challenges that arise.

Differentiated care is not just about stable clients – but providing quality care from prevention to suppression, including for clients who are unstable or have advanced disease. The global HIV community must seize the opportunity to reimagine service delivery where focus is placed on the quality of services that PLHIV receive. As has been demonstrated throughout the history of the HIV response, lessons learned from HIV can inform and improve care and service delivery across a range of health issues and vice versa. Hence, leveraging the concept of differentiated care beyond HIV to other chronic diseases for all clients will strengthen health systems and contribute to reaching Sustainable Development Goal 3 – “good health and well-being” [19]. To reach that goal, ministries of health, implementing partners, donors, civil society and communities of PLHIV will first need to unite around a differentiated care concept that puts people at the centre of services.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Kevin Osborne, Owen Ryan and Mark Aurigemma for their comments.

Competing interests

None of the authors have any competing interests to declare.

Authors' contributions

The concept for this was developed by HB, MD, PE, TE, RF, NF, AG and IZ. HB and AG wrote the first draft. All authors contributed and approved the final version.

Disclaimer

The views and opinions expressed here are solely those of the authors in their private capacity. The content in this document are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Agency for International Development or the United States Government.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. Consolidated guidelines on the use of antiretroviral drugs for treating and preventing HIV infection: recommendations for a public health approach. 2nd ed. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO; 2016. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.UNAIDS. Community-based antiretroviral therapy delivery: experiences from MSF. Geneva, Switzerland: UNAIDS; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 3.The Global Fund. A toolkit for health facilities: differentiated care for HIV and tuberculosis. Geneva, Switzerland: The Global Fund; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 4.PEPFAR. PEPFAR technical considerations for COP/ROP 2016. Washington, DC: US Department of State; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 5.UNAIDS. 90-90-90: an ambitious treatment target to help end the AIDS epidemic. Geneva, Switzerland: UNAIDS; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Duncombe C, Rosenblum S, Hellmann N, Holmes C, Wilkinson L, Biot M, et al. Reframing HIV care: putting people at the centre of antiretroviral delivery. Trop Med Int Health. 2015;20(4):430–47. doi: 10.1111/tmi.12460. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/tmi.12460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Decroo T, Koole O, Remartinez D, dos Santos N, Dezembro S, Jofrisse M, et al. Four-year retention and risk factors for attrition among members of community ART groups in Tete, Mozambique. Trop Med Int Health. 2014;19(5):514–21. doi: 10.1111/tmi.12278. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/tmi.12278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wilkinson L, Harley B, Sharp J, Solomon S, Jacobs S, Cragg C, et al. The expansion of the Adherence Club model for stable antiretroviral therapy patients in the Cape Metro, South Africa 2011–2015. Trop Med Int Health. 2016;21(6):743–9. doi: 10.1111/tmi.12699. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/tmi.12699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cawley C, Nicolas S, Szumilin E, Perry S, Amoros Quiles I, Masiku C, et al. AIDS. Durban, South Africa: 2016. Six-monthly appointments as a strategy for stable antiretroviral therapy patients: evidence of its effectiveness from seven years of experience in a Medecins Sans Frontieres-supported programme in Chiradzulu district, Malawi. 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Okoboi S, Ding E, Persuad S, Wangisi J, Birungi J, Shurgold S, et al. Community-based ART distribution system can effectively facilitate long-term program retention and low-rates of death and virologic failure in rural Uganda. AIDS Res Ther. 2015;12:37. doi: 10.1186/s12981-015-0077-4. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/s12981-015-0077-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.International AIDS Society (IAS) Differentiated care for HIV: a decision framework for antiretroviral therapy delivery. Durban, South Africa: International AIDS Society; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sidley P. South Africa's sex workers will receive HIV prevention and treatment. BMJ. 2016;352:i1593. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i1593. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmj.i1593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rudyi SKZ, Salabai N. AIDS 2016. Durban, South Africa: 2016. Fast-tracking a comprehensive, integrated and sustainable response to HIV among people who inject drugs in Ukraine. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vannakit RJJ, Pengnonyang S, Jitjang S, Janamnuaysook R, Pankam T, Trachunthong D, et al. AIDS 2016. Durban, South Africa: 2016. A cohort study of community-based test and treat for men who have sex with men and transgender women: preliminary findings from Thailand. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mesic AFJ, Aye T, Greig J, Thwe TT, Moretó-Planas L, Kliesckova J, et al. A differentiated model of care – implications for successful ART scale-up and integration of care for the main co-morbidities in a concentrated HIV epidemic – the experience of Médecins Sans Frontières in Yangon, Myanmar. J Int AIDS Soc. 2016 doi: 10.7448/IAS.20.5.21644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.UNAIDS. Agenda for zero discrimination in health care. Geneva, Switzerland: UNAIDS; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Global Network of People Living with HIV (GNP+), HIV Justice Network. Advancing HIV justice: a progress report of achievements and challenges in global advocacy against HIV criminalisation. Amsterdam: Global Network of People Living with HIV (GNP+), HIV Justice Network; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Barr D, Amon JJ, Clayton M. Articulating a rights-based approach to HIV treatment and prevention interventions. Curr HIV Res. 2011;9:396–404. doi: 10.2174/157016211798038588. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.2174/157016211798038588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.United Nations. Transforming our world: the 2030 agenda for sustainable development A/Res/70/1. New York: United Nations; 2015. [Google Scholar]