Abstract

Peritumoral brain edema (PTBE) is mediated by blood-brain barrier breakdown. PTBE results from interstitial vasogenic brain edema due to vascular endothelial growth factor and other inflammatory products of brain tumors. Glucocorticoids (GCs) are the mainstay for treatment of PTBE despite significant systemic side effects. GCs are thought to affect multiple cell types in the edematous brain. Here, we review preclinical studies of GC effects on edematous brain and review mechanisms underlying GC action on tumor cells, endothelial cells, and astrocytes. GCs may reduce tumor cell viability and suppress vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) production in tumor cells. Modulation of expression and distribution of tight junction proteins occludin, claudin-5, and ZO-1 in endothelial cells likely plays a central role in GC action on endothelial cells. GCs may also have an effect on astrocyte angiopoietin production and limited effect on astrocyte aquaporin. A better understanding of these molecular mechanisms may lead to the development of novel therapeutics for management of PTBE with a better side effect profile.

Keywords: Peritumoral brain edema (PTBE), Glucocorticoids, Blood-brain barrier

Introduction

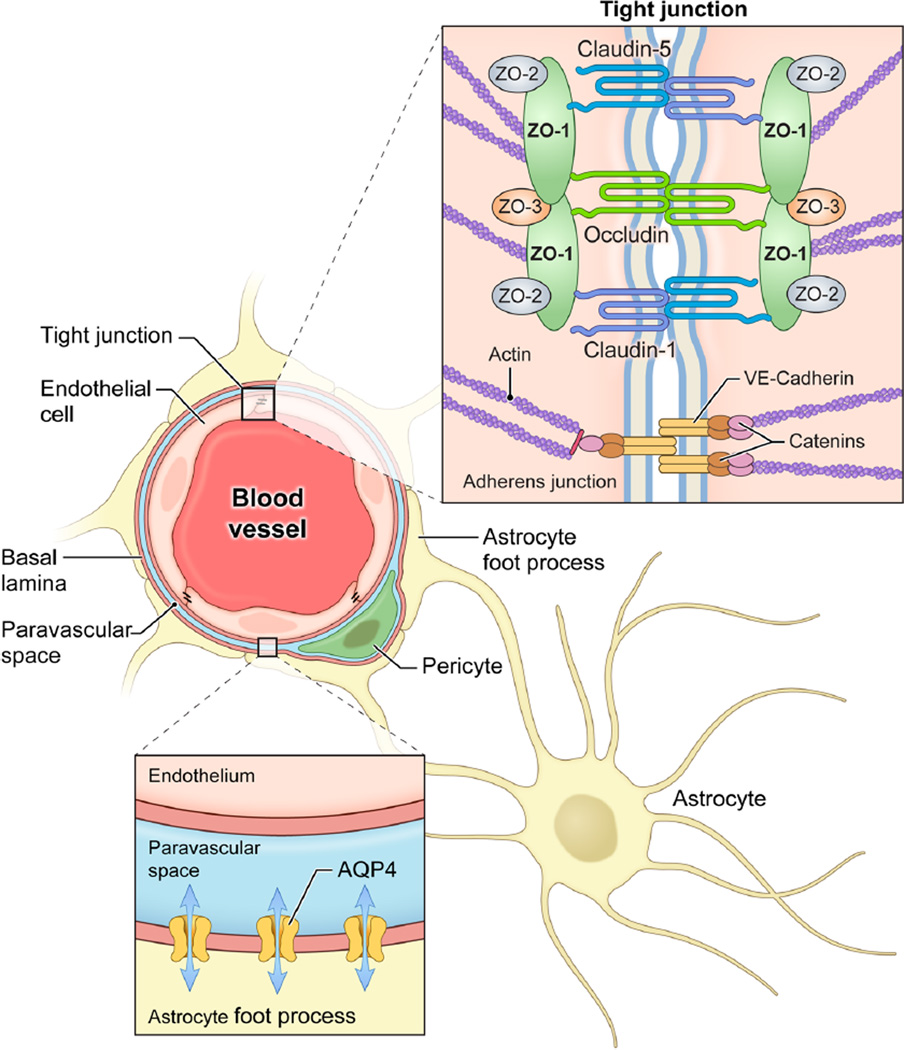

Peritumoral brain edema (PTBE) is a leading cause of morbidity and mortality in patients with brain tumors. Breakdown of the structural integrity of the blood-brain barrier (BBB) and the subsequent increase in interstitial fluid mediates this type of brain edema, termed vasogenic brain edema (VBE) (Fig. 1). In contrast, edema mediated by cell death and swelling seen in early ischemic injury for example is called cytotoxic edema. Vasogenic edema in PTBE is mediated primarily by vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) [1, 2]. Inhibition of VEGF receptors (VEGFR) with antibodies significantly decreases PTBE [3]. Although effective [4], VEGFR inhibition is rarely used to manage isolated PTBE.

Fig. 1.

Blood-brain barrier tight junctions and aquaporin-4 channels. Tight junctions between endothelial cells of the microvasculature comprise the blood-brain barrier. Claudin-5, claudin-1, and occludin are key tight junction proteins in this barrier. All three contain four transmembrane spanning regions with cytosolic amino and carboxy termini. Zonula occludens (ZO) proteins ZO-1, ZO-2, and ZO-3 anchor these tight junction proteins to the endothelial cell actin cytoskeleton. Adherens junctions also contribute to the blood-brain barrier. Vascular endothelial cadherin (VE-cadherin) is the primary component of adherens junctions and is anchored to the actin cytoskeleton by catenins. Finally, foot processes of astrocytes envelop the microvasculature also contributing to the integrity of the blood-brain barrier. Aquaporin-4 channels are located on theses foot processes facing the vessel. These channels allow for bidirectional water flow between the astrocyte and the perivascular space

Clinically, glucocorticoids (GCs) have been the mainstay of treatment to manage PTBE. It was demonstrated first in the 1940s that a crude extract from the adrenal cortex and anterior pituitary significantly decreased brain edema in a cat model [5]. In the modern neurooncology era, dexamethasone, is used commonly to manage PTBE due to its potent glucocorticoid and low mineralocorticoid effects. Despite its potency, high doses of dexamethasone are required to achieve clinically relevant reduction in PTBE and result in significant systemic side effects, particularly with prolonged use [6]. These include fat redistribution, immunosuppression, glucose intolerance, osteoporosis, and avascular necrosis among others [7]. Although routinely used to manage PTBE arising from brain tumors [8–10], GC use may actually worsen outcomes [11, 12].

GCs modulate PTBE pleiotropically, affecting multiple cell types in the brain. A better understanding of these molecular mechanisms could assist in the development of novel treatments with more specific targets and a better side effect profile. In this review, we explore preclinical studies on the molecular mechanisms by which corticosteroids exert their effects in the treatment of vasogenic edema.

Review

General pathways

GCs mediate their effects through the glucocorticoid receptor (GR). Being lipid soluble, glucocorticoids diffuse through the cell membrane and bind to intracellular GR. Subsequently, heat-shock protein 90 (Hsp90) release, GR dimerization, and GR translocation to the nucleus occurs, where transcription of multiple target genes is altered [13]. Though GCs exert some of their effects through direct action on other signaling cascades—so-called non-genomic effects—most effects relevant to brain edema are mediated through transcriptional changes [7].

GCs regulate target genes via glucocorticoid response element (GRE) within the promoter region. GR-glucocorticoid complexes bind the GRE to modulate the gene expression, typically by increasing transcription. Decreased transcription of the downstream gene, or so-called negative GREs, are rare [13, 14]. The GRE was originally discovered in the promoter region of the mouse mammary tumor virus and contains the palindromic sequence GGTACAnnnTGTTCT. [14, 15]. Each of the GR proteins in the activated homodimer contains a zinc finger that interacts with one end of this palindromic sequence via the major groove in DNA [16]. Other transcription elements, however, also play an important role in the activity of glucocorticoids in brain edema. Most notably is the activator protein type 1 (AP-1) site—a sequence upstream of genes like VEGF and other inflammatory mediators—that is targeted by GC action.

Early studies failed to demonstrate strong evidence of NSAIDS on vascular permeability or PTBE [17–20]. Therefore, although GCs have well documented anti-inflammatory effects, these effects may play a minor role in PTBE. GCs inhibit inflammation via two mechanisms [21]. First is increased transcription of proteins that suppress inflammatory mediators. For example, glucocorticoid-induced leucine zipper (GILZ) expression is stimulated by glucocorticoids and has been demonstrated to inhibit the proinflammatory transcription factors AP-1 and NF-kB. [22–24] Second, GC action inhibits proinflammatory mediators via direct protein-protein interaction. Direct inhibitory interactions between the GC-bound, activated GR homodimer and NF-kB and AP-1 proteins have been demonstrated in in vitro studies. [25, 26] AP-1 and NF-kB are important mediators of the inflammatory response, and their suppression by glucocorticoids results in decreased production of proinflammatory cytokines such as granulocyte macrophage colony stimulating factor (GM-CSF), tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), and interleukins-1,2, and 10. [13] Anti-inflammatory effects of GCs may depend primarily on direct protein-protein interactions [27, 28]. This is different from transcriptional effects on GCs primarily responsible for brain edema resolution.

Modulation of the expression of endothelial tight junction proteins may underlie the formation and resolution of brain edema. This review will primarily highlight GC effects on endothelial tight junctions and other effects on brain tumor cells and astrocytes. These sites are discussed in turn with a focus on preclinical evidence for glucocorticoid effects at each.

Tumor cells

Vascular endothelial growth factor

BBB breakdown in PTBE is primarily mediated by VEGF [1, 2]. VEGF is secreted directly by tumor cells and tumor VEGF expression correlates with vascular permeability and vasogenic brain edema (VBE) in vivo [29, 30]. GCs can directly suppress VEGF production by tumor cells in some conditions. Heiss et al. demonstrated a significant decrease in VEGF mRNA expression by a glioma cell line in vitro when treated with dexamethasone [31]. But, GCs had limited effect on VEGF induced by hypoxia rather than growth factors. Since hypoxia induces VEGF expression in many brain tumors [32], GCs may have limited effect on tumor VEGF production. The study also suggests that the activated GR interacts directly with the AP-1 transactivator complex via protein-protein interactions, bypassing transcriptional effects. This is supported by two important findings in their study. First, inhibition of the GR by RU486 reversed the effects of dexamethasone. Second, dexamethasone alone had no effect on basal levels of VEGF production in this glioma cell line. The effect was only demonstrated when VEGF production was first augmented by compounds that target the AP-1 binding site in the VEGF gene (i.e., platelet-derived growth factor). Presumably, the activated GR interacts with the AP-1 transactivator protein complex preventing its ability to stimulate VEGF transcription. The non-genomic effect is mediated by the interaction of the activated GR and the AP-1 protein complex [33].

Tumor cell viability

GCs may have a direct effect on viability and proliferation of primary brain tumor cells. Using three different human glioblastoma multiforme (GBM) cell lines, Kaup et al. demonstrated an inconsistent decrease in cell proliferation in response to dexamethasone under some conditions (e.g., incubation with dexamethasone before becoming confluent) [34]. Fan et al. demonstrated a significant inhibition of cell proliferation among three rodent glioma cell lines, though the effect was limited on human glioma cell lines. Although dexamethasone was effective against U87 human glioma cell line, a paradoxical increase in proliferation was observed in T98G and U251 human glioma cell lines, particularly at higher dexamethasone concentrations. [35] These results suggest a time-sensitive period during which proliferation of this particular cell line can be sensitized to and subsequently inhibited by dexamethasone [34]. Ultimately, some heterogeneity in cell lines’ response to GC is to be expected, especially considering recent evidence of anywhere from three to six subtypes of malignant gliomas that are otherwise histologically identical [36, 37]. Despite these findings from in vitro studies, GCs do not appear to have antitumor effects in the clinical setting. In primary brain tumor patients, dexamethasone does have beneficial effects in decreasing the apparent size of the tumor. However, this change is usually attributable to decreases in edema rather than tumor [38].

Conversely, dexamethasone may reverse the effect of chemotherapeutic agents on primary brain tumor cell viability. Two studies have reported that dexamethasone may reverse multiple cellular indicators of apoptosis normally induced by temozolomide in cultured human GBM cells [39, 40]. Temozolomide is the standard of care chemotherapeutic agent used in treatment of glioblastoma. Studies using in vitro GBM cultures have also shown that dexamethasone may reverse the efficacy of other chemotherapeutic agents including ACNU, methotrexate, and cisplatinum [41–45]. Clinical studies have demonstrated no appreciable change in concentration of chemotherapeutic agents within the tumor itself but have shown decreased concentration in peritumoral regions in response to dexamethasone [46–50]. It remains unknown whether this is due to reduced vascular permeability induced by GC effect on peritumoral endothelium.

Aquaporin

GCs may also have an important role in the regulation of water channel expression within tumor cells. Aquaporins (AQP) are water channels whose expression is thought to play a central role in the formation and resolution of brain edema. AQP-4 expression—particularly on astrocytes—has been studied the most in relationship to vasogenic edema and is discussed extensively in the astrocyte section of this review. AQP-1 channels, on the other hand, have been found expressed in glioma cells and their associated tumor vasculature [51]. Hayashi et al. found that GCs stimulated expression of AQP-1 channels in response to dexamethasone treatment on gliosarcoma cells in vitro [52]. The role of AQP-1 in the formation and/or resolution of PTBE is unclear. However, AQP-1 expression is related to changes in water and H+ movement within glioma cells as their metabolic profile shifts toward glycolysis [52].

In summary, GCs may affect PTBE by modulating VEGF secretion by primary brain tumor cells. GCs may also decrease tumor cell viability and proliferation. However, the antiproliferative effects of GCs may not be clinically relevant. GCs may decrease tumor cell responsiveness to certain chemotherapeutics and worsen clinical outcomes independent of their effect on PTBE.

Endothelial cells

Endothelial cells lining the brain microvasculature highly express tight junction proteins forming the blood-brain barrier (BBB). BBB prevents extravasation and paracellular movement of proteins and small molecules into the brain parenchyma (Fig. 1) [53]. VBE mediated by VEGF and other inflammatory mediators results in disruption of the BBB from functional loss of tight junction proteins [54]. GC-mediated reversal of VBE by modulation of tight junction proteins including occludin, claudin-5, claudin-1, and ZO-1 [59] are discussed in the following sections.

Occludin

Occludin is a 504-amino acid integral protein with a molecular weight of about 65 kDa. It contains four transmembrane spanning regions, two extracellular domains, and intracellular carboxy and amino terminal regions [56]. In endothelial cells, occludin is one of the primary proteins involved in maintaining the integrity of the BBB [57, 58]. Loss of endothelial cell occludin expression leads to vasogenic edema through BBB breakdown, particularly in high-grade gliomas [55, 59, 60]. GCs may alleviate vasogenic edema through transcriptional upregulation of functional occludin protein in endothelial cells [61–67]. Cultured endothelial cells demonstrate increased occludin expression when treated with GCs in conjunction with proinflammatory cytokines (i.e., TNF-α, IL-1) or with GC treatment alone [67]. This suggests that GCs may affect baseline endothelial cell occludin expression in addition to reversing the effects of proinflammatory cytokines. In addition to transcriptional changes, GCs may increase the functionality of occludin protein already present in endothelial cells through dephosphorylation [66]. VEGF-induced breakdown of endothelial cell culture monolayers correlates with phosphorylation of the occludin protein via protein kinase C, which is likely reversed by GC action [68, 69]. Many modern in vitro studies of the BBB utilize bovine retinal endothelial cells and measure electrical resistance across monolayer as a proxy for BBB integrity [62, 64, 67, 70]. This proxy measure for BBB permeability—called trans-endothelial resistance (TER)—is well established and based on pore theory [71]. But, few studies have assessed the effect of GCs on tight junction proteins on brain endothelial cells or an in vivo brain model of vasogenic edema [61]. An improved understanding of mechanisms of VBE in the brain requires reliable animal models.

Claudin

The claudins are a family of small transmembrane proteins that serve as the primary component of tight junctions in various tissue types [72]. Of the 20 subtypes of claudins, only claudin-1 and claudin-5 are heavily expressed in the endothelial cells of the BBB [54]. Claudin-5 is downregulated in endothelial cells cocultured with glioma cells or exposed to proinflammatory cytokines [59, 67]. Treatment with GCs results in transcriptional upregulation of claudin-5 expression in vitro but not on claudin-1 [63, 67]. Although expression of both claudin-5 and claudin-1 decreases with BBB breakdown [59, 73], only claudin-5 is transcriptionally upregulated in response to GCs.

Occludin and claudin-5 may have overlapping roles in maintaining the BBB. Gene knockout of either of the proteins result in limited effect on the ultrastructure of endothelial tight junctions and minimal increases in overall permeability [58, 74–76]. GCs may mediate their effect on tight junctions by restoring expression of both claudin-5 and occludin.

ZO-1 expression

ZO-1 is a fully intracellular protein that anchors integral proteins like occludin to the actin cytoskeleton [53]. Similarly, it also anchors adherens junctions to the cytoskeleton as well. In vitro studies have not established the exact relationship between GCs and ZO-1 expression. Romero et al. found significant upregulation of ZO-1 protein and mRNA expression in cultured rat brain endothelial cells in response to dexamethasone [65]. Other studies, however, have contradicted these findings in rat brain endothelial cell line [77], bovine retinal endothelial cells [66], and mouse brain endothelial cells [78]. Two studies employing rat brain endothelial cells and similar experimental designs found opposite effects of dexamethasone on ZO-1 expression [65, 77]. In vitro studies have consistently demonstrated a translocation of ZO-1 to the periphery of endothelial cells after treatment with GCs [65, 66, 78]. Endothelial cells are likely induced by GCs to both increase production of tight junction-associated proteins like ZO-1 in addition to reorganizing already synthesized proteins to reestablish the tight junctions of the BBB.

Adherens junctions

Adherens junctions have been shown to play an important role in the binding of adjacent vascular endothelial cells of the brain similar to tight junctions [79, 80]. These structures are based largely on the extracellularly linked protein vascular endothelial cadherin (VE-cadherin) anchored to intracellular proteins like α-catenin, β-catenin, and p120-catenin [53]. Interestingly, there may be no direct effect of glucocorticoids on adherens junction proteins [65, 67, 78]. Blecharz et al. demonstrated an increase in VE-cadherin expression after dexamethasone treatment but no effect on α-catenin, β-catenin, and β-actin. Furthermore, the increased expression of VE-cadherin was not due to direct transcriptional effects of dexamethasone on the VE-cadherin gene [78]. Glucocorticoids can increase adherens junction protein expression in endothelial cells of other tissue types [81]. In the brain though, glucocorticoids most likely mediate their tightening of the BBB primarily through a direct effect on tight junction proteins which subsequently leads to reestablishment of adherens junctions through some other mechanism. In concert, these effects restore the integrity of the BBB and prevent further extravasation of fluid into the interstitium.

Matrix metalloproteinases

Matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) are a family of enzymes that degrade the extracellular matrix and basal lamina in various tissues. In the brain, MMPs have been implicated in BBB breakdown in many models of CNS disease including glioblastomas [59], reperfusion injury following ischemic stroke [82], and active multiple sclerosis [83]. Inhibition of MMPs with synthetic compounds decreases brain vessel permeability in vivo. [84] Similarly, endogenous inhibitors of MMPs, such as tissue inhibitor of matrix metalloproteinases-1 (TIMP-1) may have a role in GC-mediated reversal of vasogenic edema. Brain endothelial cells demonstrate an upregulation of TIMP-1 protein and mRNA in response to GCs in vitro [77, 85]. Decrease inMMP-9 expression in response to dexamethasone has been confirmed in vivo as well. In an intracerebral hemorrhage animal model, MMP-9 protein expression in the ipsilateral hemisphere was decreased by GCs [86]. In a pneumococcal meningitis animal model, both the parenchymal mRNA levels and colony stimulating factor (CSF) activity levels of MMP-9 were diminished by GCs [87]. Finally, in human patients with tuberculous meningitis, CSF protein concentrations of MMP-9 were significantly reduced in response to GCs [88]. MMP-9—also called gelatinase B—mediates its destructive effect on the BBB by destroying the collagen type IV enriched for in the basal lamina of brain endothelium. MMP-9 is released by brain endothelial cells, inflammatory cells, and astrocytes and is a specific inhibitory target of TIMP-1. The TIMP-1/MMP-9 ratio plays a critical role in the normal physiology of inflammation, angiogenesis, and tissue remodeling [89]. GCs restore the ratio when decreased due to inflammation. In endothelial cells, this is likely mediated by differential transcriptional regulation of TIMP-1 expression and MMP-9 expression, [85].

In summary, the blood-brain barrier (BBB) is comprised of tightly linked endothelial cells of the brain microvasculature. Brain endothelial cells have unique expression patterns of tight junction proteins occludin, claudin-5, and ZO-1 along with adherens junction proteins comprising this barrier. GC action on this cell type likely plays the most important role in PTBE. In in vitro models of BBB breakdown, GCs induce upregulation of occludin and claudin-5 expression but have no apparent direct effect on claudin-1 or VE-cadherin expression. Additionally, dephosphorylation of occludin and translocation of ZO-1 to the cell membrane likely play a role in GC action. Finally, GCs restore the balance of matrix metalloproteinases and their endogenous inhibitors by downregulating the former and upregulating the latter. Specifically, GCs act on MMP-9 and TIMP-1.

Astrocytes

Astrocyte foot processes play an important role in the BBB integrity. Cocultures of brain endothelial cells with astrocytes represent the limited permeability of the BBB better than endothelial cells alone [90]. Removal of these cocultured astrocytes results in increased permeability but has no effect on the organization or expression of tight junction or adherens junction proteins [91]. Thus, in the reinstatement of BBB integrity stimulated by glucocorticoids, astrocytes may be important targets as well. Their role in physical barrier formation and secretion of important mediators is discussed in this section.

Aquaporins

Aquaporins are a family of at least 13 transmembrane proteins that transport water. Aquaporin 1 (AQP1), aquaporin 4 (AQP4), and to a lesser degree aquaporin 9 (AQP9) are expressed in brain tissue, but only AQP4 has been shown to play a significant role in the formation and resolution of brain edema. AQP4 upregulation consistently occurs in the setting of both cytotoxic (cellular swelling) and vasogenic brain edema (interstitial edema) and is expressed on the foot processes of astrocytes that surround the microvasculature of the brain [92, 93]. Its presumed role in these two forms of edema, however, is considerably different. In vivo studies ofAQP4 knockout animals show significantly decreased edema formation in models of cytotoxic edema like water intoxication and ischemic stroke [94] while the opposite is true in vasogenic edema. AQP4 gene knockout mice in vasogenic edema models experience increased intracranial pressure and edema from both direct intraparenchymal fluid infusion and implanted tumor cells [95]. These observations are consistent with AQP4 as a passive water channel expressed on astrocyte foot processes at the interface of where fluid enters or exits the brain parenchyma depending on the mechanism of edema.

The AQP1 gene contains a glucocorticoid response element in its promoter and has demonstrated upregulation in response to glucocorticoids in various tissues outside of the brain [96–98]. In the brain however, AQP1 expression is mainly localized to the choroid plexus and its role in edema formation is not as well established as AQP4. The effect of glucocorticoids on brain AQ4 expression is under investigation. In vitro studies have failed to demonstrate a direct effect of glucocorticoids on AQP4 expression. In testing various steroid hormones, Gu et al. demonstrated that testosterone stimulates AQP4 protein and mRNA upregulation in astrocyte cell cultures, but both estradiol and dexamethasone failed to have an effect [99]. Though a handful of studies in other tissues like the lung have demonstrated upregulation of AQP4 at the protein level in response to glucocorticoids [100], this has not been demonstrated in in vitro studies of brain tissue [93, 99].

In vivo studies suggest a more indirect effect of GCs on AQP4 expression. Dexamethasone treatment resulted in delayed decreased AQP4 protein expression in rat models of cytotoxic brain edema bacterial meningitis [101] and intracerebral hemorrhage [102], both representing. The delayed response coincides with GC-mediated edema resolution via targets other than AQP4. Additionally, a large clinical study characterizing AQP4 expression in 189 human patients with brain tumors found no difference in AQP4 expression with dexamethasone treatment [103].

Angiopoietins

Angiopoietins are substances secreted mainly by astrocytes and pericytes that play a key role in angiogenesis and stability of the BBB. The two most widely studied in relationship to brain edema are angiopoietin-1 (Ang1) and angiopoietin-2 (Ang2). Ang1 binds Tie-2 receptors, stabilizes the BBB, and is capable of stimulating upregulation of key tight junction proteins in endothelial cells [104]. Ang2, on the other hand, is a natural antagonist of the Tie-2 receptor and is associated with BBB breakdown and brain endothelial cell apoptosis in vivo [105]. The interplay of Ang1 and Ang2 is important in proper stability of the BBB. Overexpression of Ang2, for example, prevents blood vessel formation in animal embryos [106]. Despite their important role in angiogenesis and brain edema, the literature on the effect of glucocorticoids on astrocyte angiopoietins is limited. In an in vitro study of brain astrocyte, pericyte, and endothelial cells, Kim et al. found that dexamethasone stimulates increased protein and mRNA expression of Ang1 in astrocytes and pericytes, though not in endothelial cells [107]. This also coincided with a decrease in protein and mRNA expression of VEGF in the same cell types. These findings are consistent with the role of glucocorticoids in promoting the integrity of the BBB which is at least partially mediated by the stabilizing effects of angiopoietin-1.

In summary, astrocytes envelop endothelial cells of the microvasculature and play a key role in the structure and signaling involved in BBB integrity. AQP4 is a passive water channel expressed on astrocyte foot processes and plays an important role in resolution of vasogenic edema. Dexamethasone has no direct effect on AQP4 expression in astrocyte cultures though in vivo studies demonstrate a secondary increase in astrocyte AQP4 expression. Finally, angiopoietin-1 and angiopoietin-2 stabilize or destabilize microvascular structure, respectively. Limited data suggests dexamethasone may upregulate angiopoietin-1 astrocyte expression.

Conclusions

Peritumoral brain edema at the molecular level is the result of disruption in the structure of the BBB. Of the three main cellular targets of glucocorticoids (tumor cells, endothelial cells, and astrocytes), protein expression in endothelial cells likely play the most critical role in GC-mediated reversal of PTBE. In particular, the tight junction proteins occludin, claudin-5, and ZO-1 along with MMPs and VEGF are central to the GC mechanism of action (Table 1). Importantly though, in vitro studies can often be at odds with clinically relevant mechanisms. We have developed an in vivo animal model which isolates VEGF-mediated vasogenic edema and plan to employ this model in further elucidation of mechanism of glucocorticoid action (under review). A better understanding of these glucocorticoid mechanisms will help identify novel targets for edema resolution potentially with better side effect profiles than glucocorticoids.

Table 1.

Summary of glucocorticoid effects in preclinical studies

| Cell type | Protein | Function | In vitro GC Effect (protein and mRNA expression) |

Other GC effects | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tumor | VEGF | Increased permeability | Downregulation | Counteracts VEGF mediated edema |

Ineffective in hypoxia mediated VEGF production |

| Tumor | AQP1 | Water channel | Upregulation | – | Not likely a mediator of PTBE |

| Endothelial | GC Receptor | Mediates GC action | Downregulation | Nuclear concentration | |

| Endothelial | Occludin | Tight junction integral protein |

Upregulation | Dephosphorylation | Phosphorylated occludin is nonfunctional |

| Endothelial | Claudin-5 | Tight junction integral protein |

Upregulation | – | |

| Endothelial | Claudin-1 | Tight junction integral protein |

No effect | – | |

| Endothelial | ZO-1 | Tight junction intracellular anchor |

Mixed | Redistribution to cell periphery |

|

| Endothelial | VE-Cadherin | Adherens junctions | No effect | – | |

| Endothelial | MMP-9 | ECM and basal lamina degradation |

Downregulation | – | MMP-9/TIMP-1 ratio important mediator of BBB integrity |

| Endothelial | TIMP-1 | Endogenous inhibitor of MMP-9 and others |

Upregulation | – | MMP-9/TIMP-1 ratio important mediator of BBB integrity |

| Astrocyte | AQP4 | Water channel | None | Secondary upregulation in-vivo |

Plays key role in cerebral edema |

| Astrocyte | AQP1 | Water channel | None | – | Unclear role in cerebral edema. Localized to choroid plexus |

| Astrocyte | AQP9 | Water and solute channel | None | – | Unclear role in cerebral edema |

| Astrocyte | Angiopoietin-1 | Stabilizes vessels | Upregulation | – | Limited data |

| Astrocyte | Angiopoietin-2 | Destabilizes vessels; potentiates angiogenesis |

– | – |

VEGF vascular endothelial growth factor, AQP aquaporin, ZO-1 zonula occludens 1, VE-cadherin vascular endothelial cadherin, MMP-9 matrix metalloproteinase 9, TIMP-1 tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases 1, GC glucocorticoid, ECM extracellular matrix, PTBE peritumoral brain edema

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Marsha Merrill, PhD, for discussions and historical insights. This study was funded by the intramural research program of the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke at the National Institutes of Health (NIH). This research was also made possible through the NIH Medical Research Scholars Program, a public-private partnership supported jointly by the NIH and generous contributions to the Foundation for the NIH. The authors thank Ethan Tyler from the Medical Arts Branch of the NIH Clinical Center for the illustration.

Footnotes

Compliance with ethical standards No financial disclosures.

Conflict of interest None.

References

- 1.Berkman RA, Merrill MJ, Reinhold WC, et al. Expression of the vascular permeability factor/vascular endothelial growth factor gene in central nervous system neoplasms. J Clin Invest. 1993;91:153–159. doi: 10.1172/JCI116165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Strugar J, Rothbart D, Harrington W, Criscuolo GR. Vascular permeability factor in brain metastases: correlation with vasogenic brain edema and tumor angiogenesis. J Neurosurg. 1994;81:560–566. doi: 10.3171/jns.1994.81.4.0560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gerstner ER, Duda DG, di Tomaso E, et al. VEGF inhibitors in the treatment of cerebral edema in patients with brain cancer. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2009;6:229–236. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2009.14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ananthnarayan S, Bahng J, Roring J, et al. Time course of imaging changes of GBM during extended bevacizumab treatment. J Neuro-Oncol. 2008;88:339–347. doi: 10.1007/s11060-008-9573-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Prados M, Strowger B, Feindel W. Studies on cerebral edema; reaction of the brain to exposure to air; physiologic changes. Arch Neurol Psychiatr. 1945;54:290–300. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vecht CJ, Hovestadt A, Verbiest HB, et al. Dose-effect relationship of dexamethasone on Karnofsky performance in metastatic brain tumors: a randomized study of doses of 4, 8, and 16 mg per day. Neurology. 1994;444:675–680. doi: 10.1212/wnl.44.4.675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dietrich J, Rao K, Pastorino S, Kesari S. Corticosteroids in brain cancer patients: benefits and pitfalls. Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol. 2011;4(2):233–242. doi: 10.1586/ecp.11.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Veldhuijzen van Zanten SEM, Cruz O, Kaspers GJL, et al. State of affairs in use of steroids in diffuse intrinsic pontine glioma: an international survey and a review of the literature. J Neuro-Oncol. 2016;128:387–394. doi: 10.1007/s11060-016-2141-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Marantidou A, Levy C, Duquesne A, et al. Steroid requirements during radiotherapy for malignant gliomas. J Neuro-Oncol. 2010;100:89–94. doi: 10.1007/s11060-010-0142-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ryken TC, McDermott M, Robinson PD, et al. The role of steroids in the management of brain metastases: a systematic review and evidence-based clinical practice guideline. J Neuro-Oncol. 2010;96:103–114. doi: 10.1007/s11060-009-0057-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shields LBE, Shelton BJ, Shearer AJ, et al. Dexamethasone administration during definitive radiation and temozolomide renders a poor prognosis in a retrospective analysis of newly diagnosed glioblastoma patients. Radiat Oncol. 2015;10:222. doi: 10.1186/s13014-015-0527-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pitter KL, Tamagno I, Alikhanyan K, et al. Corticosteroids compromise survival in glioblastoma. Brain. 2016;139:1458–1471. doi: 10.1093/brain/aww046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Barnes PJ. Molecular mechanisms and cellular effects of glucocorticosteroids. Immunol Allergy Clin N Am. 2005;25:451–468. doi: 10.1016/j.iac.2005.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Barnes PJ. Anti-inflammatory actions of glucocorticoids: molecular mechanisms. Clin Sci. 1998;572:557–572. doi: 10.1042/cs0940557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chandler Maler BA, Yamamoto KRVL. DNA sequences bound specifically by glucocorticoid receptor in vitro render a heterologous promoter hormone responsive in vivo. Cell. 1983;33:489–499. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(83)90430-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Luisi BF, Xu WX, Otwinowski Z, et al. Crystallographic analysis of the interaction of the glucocorticoid receptor with DNA. Nature. 1991;352:497–505. doi: 10.1038/352497a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ohnishi T, Sher P, Posner J, Shapiro WR. Capillary permeability factor secreted by malignant brain tumor. J Neurosurg. 1990;72:245–251. doi: 10.3171/jns.1990.72.2.0245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bruce JN, Criscuolo GR, Merrill MJ, et al. Vascular permeability induced by protein product of malignant brain tumors: inhibition by dexamethasone. J Neurosurg. 1987;67:880–884. doi: 10.3171/jns.1987.67.6.0880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Weissman DE, Stewart C. Experimental drug therapy of peritumoral brain edema. J Neuro-Oncol. 1988;6:339–342. doi: 10.1007/BF00177429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Reichman H, Farrel C, Maestro R. Effects of steroids and nonsteroid anti-inflammatory agents on vascular permeability in a rat glioma model. J Neurosurg. 1986;65:233–237. doi: 10.3171/jns.1986.65.2.0233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nicolaides NC, Galata Z, Kino T, et al. The human glucocorticoid receptor: molecular basis of biologic function. Steroids. 2010;75:1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.steroids.2009.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mittelstadt PR, Ashwell JD. Inhibition of AP-1 by the glucocorticoid-inducible protein GILZ. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:29603–29610. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M101522200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ayroldi E, Riccardi C. Glucocorticoid-induced leucine zipper (GILZ): a new important mediator of glucocorticoid action. FASEB J. 2009;23:3649–3658. doi: 10.1096/fj.09-134684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Newton R. Anti-inflammatory glucocorticoids: changing concepts. Eur J Pharmacol. 2014;724:231–236. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2013.05.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Scheinman R, Gualberto A, Jewell C, et al. Characterization of mechanisms involved in transrepression of NF-kappa B by activated glucocorticoid receptors. [Accessed 10 May 2016];PubMed-NCBI. 1995 doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.2.943. http://proxy.library.upenn.edu:2084/pubmed?otool=upennlib&term=Scheinman+RI,+Gualberto+A,+Jewell+CM,+Cidlowski+JA,+Baldwin+Jr+AS+1995+Characterization+of+mechanisms+involved+in+transrepression+of+NF-_B+by+activated+glucocorticoid+receptors.+Mol+Cell+Bio. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ray A, Prefontaine KE. Physical association and functional antagonism between the p65 subunit of transcription factor NF-kappa B and the glucocorticoid receptor. ProcNatl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:752–756. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.2.752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Reichardt HM, Tuckermann JP, Vujic M, et al. Repression of in inflammatory responses in the absence of DNA binding by the glucocorticoid receptor. EMBO J. 2001;20:7168–7173. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.24.7168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Reichardt HM, Kaestner KH, Tuckermann J, et al. DNA binding of the glucocorticoid receptor is not essential for survival. Cell. 1998;93:531–541. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81183-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Plate K, Breier G, Weich H, Risau W. Vascular endothelial growth factor is a potential tumor angiogenesis factor in human gliomas in vivo. Nature. 1992;355:242–244. doi: 10.1038/359845a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Machein MR, Kullmer J, Fiebich BL, et al. Vascular endothelial growth factor expression, vascular volume, and, capillary permeability in human brain tumors. (Human. Neurosurgery. 1999;44:732–740. doi: 10.1097/00006123-199904000-00022. discussion 740–1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Heiss JD, Papavassiliou E, Merrill MJ, et al. Mechanism of dexamethasone suppression of brain tumor-associated vascular permeability in rats. Involvement of the glucocorticoid receptor and vascular permeability factor. J Clin Invest. 1996;98:1400–1408. doi: 10.1172/JCI118927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shweiki D, Itin A, Soffer D, Keshet E. Vascular endothelial growth factor induced by hypoxia may mediate hypoxia-initiated angiogenesis. Nature. 1992;360:40–46. doi: 10.1038/359843a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Scheinman R, Gualberto A, Jewell C, et al. Characterization of mechanisms involved in transrepression of NF-kappa B by activated glucocorticoid receptors. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15(2):943–953. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.2.943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kaup B, Schindler I, Knupfer H, et al. Time-dependent inhibition of glioblastoma cell proliferation by dexamethasone. J Neuro-Oncol. 2001;51:105–110. doi: 10.1023/a:1010684921099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fan Z, Sehm T, Rauh M, et al. Dexamethasone alleviates tumor-associated brain damage and angiogenesis. PLoS One. 2014;9:e93264. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0093264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kloosterhof NK, de Rooi JJ, Kros M, et al. Molecular subtypes of glioma identified by genome-wide methylation profiling. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2013;52:665–674. doi: 10.1002/gcc.22062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Li A, Walling J, Ahn S, et al. Unsupervised analysis of transcriptomic profiles reveals six glioma subtypes. Cancer Res. 2009;69:2091–2099. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-2100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fletcher JW, George EA, Henry RE, Donati RM. Brain scans, dexamethasone therapy, and brain tumors. JAMA. 1975;232:1261–1263. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Das A, Banik NL, Patel SJ, Ray SK. Dexamethasone protected human glioblastoma U87MG cells from temozolomide induced apoptosis by maintaining Bax:Bcl-2 ratio and preventing proteolytic activities. Mol Cancer. 2004 doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-3-36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sur P, Sribnick EA, Patel SJ, et al. Dexamethasone decreases temozolomide-induced apoptosis in human glioblastoma T98G cells. Glia. 2005;50:160–167. doi: 10.1002/glia.20168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wolff JE, Denecke J, Jürgens H. Dexamethasone induces partial resistance to cisplatinum in C6 glioma cells. Anticancer Res. 1996;16:805–809. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wolff JE, Jürgens H. Dexamethasone induced partial resistance to methotrexate in C6-glioma cells. Anticancer Res. 1994;14:1585–1588. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Weller M, Schmidt C, RothW, Dichgans J. Chemotherapy of human malignant glioma: prevention of efficacy by dexamethasone? Neurology. 1997;48:1704–1709. doi: 10.1212/wnl.48.6.1704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Qian YH, Xiao Q, Chen H, Xu J. Dexamethasone inhibits camptothecin-induced apoptosis in C6-glioma via activation of Stat5/Bcl-xL pathway. Biochim Biophys Acta - Mol Cell Res. 2009;1793:764–771. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2009.01.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ueda S, Mineta T, Nakahara Y, et al. Induction of the DNA repair gene O6-methylguanine-DNA methyltransferase by dexamethasone in glioblastomas. J Neurosurg. 2004;101:659–663. doi: 10.3171/jns.2004.101.4.0659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fross RD, Warnke PC, Groothuis DR. Blood flow and blood-to-tissue transport in 9 L gliosarcomas: the role of the brain tumor model in drug delivery research. J Neuro-Oncol. 1991;11:185–197. doi: 10.1007/BF00165526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Morris GM, Micca PL, Coderre JA. The effect of dexamethasone on the uptake of p-boronophenylalanine in the rat brain and intracranial 9 L gliosarcoma. Appl Radiat Isot. 2004;61:917–921. doi: 10.1016/j.apradiso.2004.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Straathof CSM, Van Den Bent MJ, Loos WJ, et al. The accumulation of topotecan in 9 L glioma and in brain parenchyma with and without dexamethasone administration. J Neuro-Oncol. 1999;42:117–122. doi: 10.1023/a:1006166716683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Straathof CSM, Van Den Bent MJ, Ma J, et al. The effect of dexamethasone on the uptake of cisplatin in 9 L glioma and the area of brain around tumor. J Neuro-Oncol. 1998;37:1–8. doi: 10.1023/a:1005835212246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Muldoon LL, Soussain C, Jahnke K, et al. Chemotherapy delivery issues in central nervous system malignancy: a reality check. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:2295–2305. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.09.9861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Endo M, Jain RK, Witwer B, Brown D. Water channel (aquaporin 1) expression and distribution in mammary carcinomas and glioblastomas. Microvasc Res. 1999;58:89–98. doi: 10.1006/mvre.1999.2158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hayashi Y, Edwards NA, Proescholdt MA, et al. Regulation and function of aquaporin-1 in glioma cells 1. Neoplasia. 2007;9:777–787. doi: 10.1593/neo.07454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mehta D, Malik AB. Review) Signaling mechanisms regulating endothelial permeability. Physiol Rev. 2006;86:279–367. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00012.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Papadopoulos MC, Saadoun S, Davies DC, Bell BA. Emerging molecular mechanisms of brain tumour oedema. Br J Neurosurg. 2001;15:101–108. doi: 10.1080/02688690120036775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Liebner S, Fischmann A, Rascher G, et al. Claudin-1 and claudin-5 expression and tight junction morphology are altered in blood vessels of human glioblastoma multiforme. Acta Neuropathol. 2000;100:323–331. doi: 10.1007/s004010000180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tstlkita S. Occludin: a novel integral membrane protein localizing at tight junctions. J Cell Biol. 1993;123:1777–1788. doi: 10.1083/jcb.123.6.1777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Huber JD, Egleton RD, Thomas P, et al. Molecular physiology and pathophysiology of tight junctions in the blood–brain barrier. Trends Neurosci. 2001;24:719–725. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(00)02004-x. Review) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hirase T, Staddon JM, Saitou M, et al. Occludin as a possible determinant of tight junction permeability in endothelial cells. J Cell Sci. 1997;110(Pt 1):1603–1613. doi: 10.1242/jcs.110.14.1603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ishihara H, Kubota H, Lindberg RLP, et al. Endothelial cell barrier impairment induced by glioblastomas and transforming growth factor a 2 involves matrix metalloproteinases and tight junction proteins. Exp Neurol. 2008 doi: 10.1097/NEN.0b013e31816fd622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Papadopoulos MC, Saadoun S, Woodrow CJ, et al. Occludin expression in microvessels of neoplastic and nonneoplastic human brain. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol. 2001;27:384–395. doi: 10.1046/j.0305-1846.2001.00341.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Gu YT, Qin LJ, Qin X, Xu F. The molecular mechanism of dexamethasone-mediated effect on the blood-brain tumor barrier permeability in a rat brain tumor model. Neurosci Lett. 2009 doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2008.12.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Keil JM, Liu X, Antonetti DA. Glucocorticoid induction of occludin expression and endothelial barrier requires transcription factor p54 NONO. NONO. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2013;54:4007–4015. doi: 10.1167/iovs.13-11980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Felinski EA, Cox AE, Phillips BE, Antonetti DA. Glucocorticoids induce transactivation of tight junction genes occludin and claudin-5 in retinal endothelial cells via a novel cis-element. Exp Eye Res. 2008;86:867–878. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2008.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Förster C, Silwedel C, Golenhofen N, et al. Occludin as direct target for glucocorticoid-induced improvement of blood-brain barrier properties in a murine in vitro system. J Physiol. 2005;565:475–486. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2005.084038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Romero IA, Radewicz K, Jubin E, et al. Changes in cytoskeletal and tight junctional proteins correlate with decreased permeability induced by dexamethasone in cultured rat brain endothelial cells. Neurosci Lett. 2003;344:112–116. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(03)00348-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Antonetti DA, Wolpert EB, DeMaio L, et al. Hydrocortisone decreases retinal endothelial cell water and solute flux coincident with increased content and decreased phosphorylation of occludin. J Neurochem. 2002;80:667–677. doi: 10.1046/j.0022-3042.2001.00740.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Förster C, Burek M, Romero IA, et al. Differential effects of hydrocortisone and TNFα on tight junction proteins in an in vitro model of the human blood–brain barrier. J Physiol. 2008;5867:1937–1949. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.146852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Murakami T, Frey T, Lin C, Antonetti DA. Protein kinase C phosphorylates occludin regulating tight junction trafficking in vascular endothelial growth factor-induced permeability in vivo. Diabetes. 2012;61:1573–1583. doi: 10.2337/db11-1367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Murakami T, Felinski EA, Antonetti DA. Occludin phosphorylation and ubiquitination regulate tight junction trafficking and vascular endothelial growth factor-induced permeability. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:21036–21046. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.016766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Hoheisel D, Nitz T, Franke H, et al. Hydrocortisone reinforces the blood-brain properties in a serum free cell culture system. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1998;247:312–315. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Yuan SY, Rigor RR. Methods for Measuring Permeability. 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 72.Elkouby-Naor L, Ben-Yosef T. Functions of claudin tight junction proteins and their complex interactions in various physiological systems, 1st ed. Int Rev Cell Mol Biol. 2010 doi: 10.1016/S1937-6448(10)79001-8. (Review/book) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Förster C, Waschke J, Burek M, et al. Glucocorticoid effects on mouse microvascular endothelial barrier permeability are brain specific. J Physiol. 2006;573:413–425. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.106385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Nitta T, Hata M, Gotoh S, et al. Size-selective loosening of the blood-brain barrier in claudin-5-deficient mice. J Cell Biol. 2003;161:653–660. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200302070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Wong V, Gumbiner BM. Synthetic peptide corresponding to the extracellular domain of occludin perturbs the tight junction permeability barrier. J Cell Biol. 1997;136:399–409. doi: 10.1083/jcb.136.2.399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Saitou M, Fujimoto K, Doi Y, et al. Occludin-deficient embryonic stem cells can differentiate into polarized epithelial cells bearing tight junctions. J Cell Biol. 1998;141:397–408. doi: 10.1083/jcb.141.2.397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Harkness KA, Adamson P, Sussman J, et al. Dexamethasone regulation of matrix metalloproteinase expression in CNS vascular endothelium. Brain. 2000;123:698–709. doi: 10.1093/brain/123.4.698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Blecharz KG, Drenckhahn D, Forster CY. Glucocorticoids increase VE-cadherin expression and cause cytoskeletal rearrangements in murine brain endothelial cEND cells. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2008;28:1139–1149. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2008.2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Gumbiner BM. Cell adhesion: the molecular basis of tissue architecture and morphogenesis. Cell. 1996;84:345–357. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81279-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Lampugnani MG, Corada M, Caveda L, et al. The molecular organization of endothelial cell to cell junctions: differential association of plakoglobin, beta-catenin, and alpha-catenin with vascular endothelial cadherin (VE-cadherin. J Cell Biol. 1995;129:203–217. doi: 10.1083/jcb.129.1.203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Guan Y, Rubenstein NM, Failor KL, et al. Glucocorticoids control beta-catenin protein expression and localization through distinct pathways that can be uncoupled by disruption of signaling events required for tight junction formation in rat mammary epithelial tumor cells. Mol Endocrinol. 2004;18:214–227. doi: 10.1210/me.2003-0014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Rosenberg GA, Yang Y. Vasogenic edema due to tight junction disruption by matrix metalloproteinases in cerebral ischemia. Neurosurg Focus. 2007;22:E4. doi: 10.3171/foc.2007.22.5.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Avolio C, Filippi M, Tortorella C, et al. Serum MMP-9/TIMP-1 andMMP-2/TIMP-2 ratios in multiple sclerosis: relationships with different magnetic resonance imaging measures of disease activity during IFN-beta-1a treatment. Mult Scler. 2005;11:441–446. doi: 10.1191/1352458505ms1193oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Gijbels K, Galardy RE, Steinman L. Reversal of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis with a hydroxamate inhibitor of matrix metalloproteases. J Clin Invest. 1994;94:2177–2182. doi: 10.1172/JCI117578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Förster C, Kahles T, Kietz S, Drenckhahn D. Dexamethasone induces the expression of metalloproteinase inhibitor TIMP-1 in the murine cerebral vascular endothelial cell line cEND. J Physiol. 2007;580:937–949. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.129007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Yang JT, Lee TH, Lee IN, et al. Dexamethasone inhibits ICAM-1 and MMP-9 expression and reduces brain edema in intracerebral hemorrhagic rats. Acta Neurochir. 2011;153:2197–2203. doi: 10.1007/s00701-011-1122-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Liu X, Han Q, Sun R, Li Z. Dexamethasone regulation of matrix metalloproteinase expression in experimental pneumococcal meningitis. Brain Res. 2008;1207:237–243. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2008.01.106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Green JA, Tran CTH, Farrar JJ, et al. Dexamethasone, cerebrospinal fluid matrix metalloproteinase concentrations and clinical outcomes in tuberculous meningitis. PLoS One. 2009 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Gardner J, Ghorpade A. Review) Tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase (TIMP)-1: the TIMPed balance of matrix metalloproteinases in the central nervous system. J Neurosci Res. 2003;74:801–806. doi: 10.1002/jnr.10835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Kröll S, El-Gindi J, Thanabalasundaram G, et al. Control of the blood-brain barrier by glucocorticoids and the cells of the neurovascular unit. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2009;1165:228–239. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.04040.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Hamm S, Dehouck B, Kraus J, et al. Astrocyte mediated modulation of blood-brain barrier permeability does not correlate with a loss of tight junction proteins from the cellular contacts. Cell Tissue Res. 2004;315:157–166. doi: 10.1007/s00441-003-0825-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Verkman AS, Binder DK, Bloch O, et al. Three distinct roles of aquaporin-4 in brain function revealed by knockout mice. Biochim Biophys Acta-Biomembr. 2006;1758:1085–1093. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2006.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Saadoun S, Papadopoulos MC, Davies DC, et al. Aquaporin-4 expression is increased in oedematous human brain tumours. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2002;72:262–265. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.72.2.262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Manley GT, Fujimura M, Ma T, et al. Aquaporin-4 deletion in mice reduces brain edema after acute water intoxication and ischemic stroke. Nat Med. 2000;6:159–163. doi: 10.1038/72256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Papadopoulos MC, Manley GT, Krishna S, Verkman AS. Aquaporin-4 facilitates reabsorption of excess fluid in vasogenic brain edema. FASEB J. 2004;18:1291–1293. doi: 10.1096/fj.04-1723fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Moon C, King LS, Agre P. Aqp1 expression in erythroleukemia cells: genetic regulation of glucocorticoid and chemical induction. Am J Phys. 1997;273:C1562–C1570. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1997.273.5.C1562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Stoenoiu MS, Ni J, Verkaeren C, et al. Corticosteroids induce expression of aquaporin-1 and increase transcellular water transport in rat peritoneum. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2003;14:555–565. doi: 10.1097/01.asn.0000053420.37216.9e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Liu H, Hooper SB, Armugam A, et al. Aquaporin gene expression and regulation in the ovine fetal lung. J Physiol. 2003;551:503–514. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2003.044875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Gu F, Hata R, Toku K, et al. Testosterone up-regulates aquaporin-4 expression in cultured astrocytes. J Neurosci Res. 2003;72:709–715. doi: 10.1002/jnr.10603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Gunnarson E, Zelenina M, Aperia A. Regulation of brain aquaporins. Neuroscience. 2004;129:947–955. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2004.08.022. Review) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Du KX, Dong Y, Zhang Y, et al. Effects of dexamethasone on aquaporin-4 expression in brain tissue of rat with bacterial meningitis. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2015;8:3090–3096. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Gu YT, Zhang H, Xue YX. Dexamethasone treatment modulates aquaporin-4 expression after intracerebral hemorrhage in rats. Neurosci Lett. 2007;413:126–131. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2006.11.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Warth A, Simon P, Capper D, et al. Expression pattern of the water channel aquaporin-4 in human gliomas is associated with blood-brain barrier disturbance but not with patient survival. J Neurosci Res. 2007;85:1336–1346. doi: 10.1002/jnr.21224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Hori S, Ohtsuki S, Hosoya KI, et al. A pericyte-derived angiopoietin-1 multimeric complex induces occludin gene expression in brain capillary endothelial cells through Tie-2 activation in vitro. J Neurochem. 2004;89:503–513. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2004.02343.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Nag S, Papneja T, Venugopalan R, Stewart DJ. Increased angiopoietin2 expression is associated with endothelial apoptosis and blood-brain barrier breakdown. Lab Investig. 2005;85:1189–1198. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.3700325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Maisonpierre PC. Angiopoietin-2, a natural antagonist for Tie2 that disrupts in vivo angiogenesis. Science. 1997;277:55–6080. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5322.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Kim H, Lee JM, Park JS, et al. Dexamethasone coordinately regulates angiopoietin-1 and VEGF: a mechanism of glucocorticoid-induced stabilization of blood-brain barrier. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2008;372:243–248. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.05.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]