Abstract

Previous preclinical studies and a phase I clinical trial suggested myo-inositol may be a safe and effective lung cancer chemopreventive agent. We conducted a randomized, double blind, placebo-controlled, phase IIb study to determine the chemopreventive effects of myo-inositol in smokers with bronchial dysplasia. Smokers with ≥ 1 site of dysplasia identified by autofluorescence bronchoscopy-directed biopsy were randomly assigned to receive oral placebo or myo-inositol, 9 g once/day for two weeks, and then twice/day for 6 months. The primary endpoint was change in dysplasia rate after six months of intervention on a per participant basis. Other trial endpoints reported herein include Ki-67 labeling index, blood and bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BAL) levels of pro-inflammatory, oxidant/anti-oxidant biomarkers, and an airway epithelial gene-expression signature for phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K) activity. Seventy four (n=38 myo-inositol, n=36 placebo) participants with a baseline and 6-month bronchoscopy were included in all efficacy analyses. The complete response and the progressive disease rates were 26.3% versus 13.9% and 47.4% versus 33.3%, respectively, in the myo-inositol and placebo arms (p=0.76). Compared with placebo, myo-inositol intervention significantly reduced IL-6 levels in BAL over 6 months (p=0.03). Among those with a complete response in the myo-inositol arm, there was a significant decrease in a gene-expression signature reflective of PI3K activation within the cytologically-normal bronchial airway epithelium (p=0.002). The heterogeneous response to myo-inositol suggests a targeted therapy approach based on molecular alterations is needed in future clinical trials to determine the efficacy of myo-inositol as a chemopreventive agent.

Keywords: myo-Inositol, bronchial dysplasia, chemoprevention

INTRODUCTION

Lung cancer is the most common cause of cancer death worldwide, with an estimated 1.8 million new cases and 1.6 million deaths in 2012(1) and causes more deaths in the United States than colorectal cancer, breast cancer, and prostate cancer combined.(2) Former heavy smokers retain an elevated risk for lung cancer even years after they stop smoking.(3, 4) Therefore, a strategy to prevent lung cancer in addition to smoking cessation is needed. Chemoprevention involves the use of dietary or pharmaceutical interventions to slow or reverse the progression of premalignancy to invasive cancer.(5, 6) In addition to efficacy, safety is a critical consideration since the intervention is given to individuals who are at risk for cancer, but otherwise are in apparent good health.

myo-Inositol is found in a wide variety of foods such as whole grains, seeds, and fruits. It is a source of several second messengers including diacylglycerol and is required by human cells for growth and survival in culture. Pre-clinical studies show myo-inositol inhibits carcinogenesis by 40% to 50% in both the induction and post-initiation phases.(7, 8) Mechanistically, the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K) pathway that is activated in the bronchial epithelial cells of smokers with dysplasia was found to be inhibited by myo-inositol and associated with regression of bronchial dysplasia.(9) The low toxicity and promising pre-clinical and phase I clinical trial data led to the current randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase IIb clinical trial in smokers with bronchial dysplasia, who are at high risk for lung cancer.(10)

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Clinical Trial Protocol

The Review of Ethics Boards of the BCCA and the University of British Columbia, and the Mayo Clinic and University of New Mexico Institutional Review Boards approved this study. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants. The clinical trial registration number was NCT00783705.

Study participant recruitment and eligibility

From November 3, 2008 to August 9, 2013, current and former smokers between the ages of 45 to 79 years from the Greater Vancouver area who had a ≥ 30 pack-year smoking history were recruited through the community outreach networks, television programs, radio broadcasts, and local newspapers. In March of 2010 recruitment was extended to participants in Rochester, Minnesota and Albuquerque, New Mexico. A former smoker was defined as a person who had not smoked for at least one year, verified by urinary cotinine below 100 ng/ml. Eligibility criteria for randomization to study drug included ≥ 1 site of histologically-confirmed bronchial dysplasia on baseline bronchoscopy, no evidence of lung cancer (stage 0/I curatively treated non-small cell lung cancer with all therapy completed ≥6 months prior to randomization allowed), and normal organ and marrow function.

Bronchoscopic Procedures

Prior to July 8, 2009, 41 participants were screened for bronchoscopy using C-reactive protein (CRP) level in plasma. Those with CRP≥1.25 mg/L were offered autofluorescence bronchoscopy to localize areas of dysplasia using the Onco-LIFE device (Novadaq Technologies Corp., Richmond, BC, Canada) as described previously.(11, 12) The use of CRP was based on our preliminary study that the prevalence of dysplasia was higher among those with elevated CRP. Biopsy samples were taken from areas that were abnormal under white light and/or autofluorescence examination and at least one control biopsy was obtained from bronchial mucosa with normal fluorescence in an upper or lower lobe of the lung. After July 8, 2009, the CRP eligibility criterion was removed as the prevalence of dysplasia in the high versus low CRP group was not sufficiently higher to justify its use. An additional 407 participants who met the age and smoking criteria were offered a bronchoscopy with biopsy of all abnormal sites under white-light or autofluorescence examination and 6 pre-determined sites in the main carina, both upper and lower lobes and the right middle lobe before and after treatment. The median number of biopsy samples obtained per participant was 6 (range=1–14) in the myo-inositol group and 7 (range=1–14) in the placebo group.

Bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) from the right upper lobe or the left upper lobe was performed using 20 mL aliquots of normal saline as described previously.(13) BAL cells were separated from the fluid by centrifugation at 1500 rpm for 5 minutes and fluids were stored at −80°C until cytokine evaluation.

Bronchial brushing was performed in two separate subsegmental bronchi that had not been lavaged or biopsied using a 1.7 mm diameter bronchial cytology brush (Hobbs Medical, Stafford Springs, CT). The brushes were retrieved and immediately immersed in RNALater and kept frozen at −80° C until RNA extraction and gene expression profiling using RNA-Seq.

The biopsy samples were fixed in buffered formalin, embedded in paraffin, and serial sections were obtained. Sections 1, 6, and 13 were stained with hematoxylin-eosin and used to determine histopathologic classification. They were systematically reviewed by two pulmonary pathologists (MA, DI) who were blinded to intervention assignments. All biopsy samples were classified according to World Health Organization (WHO) criteria (normal, basal cell hyperplasia, metaplasia, mild/moderate/severe dysplasia, or carcinoma in-situ).(14) One grade difference in sample classification between the two pathologists was resolved by a third pathologist (JY) to reach a final diagnosis.

Spiral Chest Computed Tomography (CT)

CT scans were performed at BCCA as previously described using a 16 detector CT scanner at 120 kVp, 0.5 second rotation time, pitch 1.25 and 40 mA. Images were reconstructed at 1 mm slice width at 1 mm spacing.(15, 16) The CT scans were performed before and at the end of the 6 month intervention. The site, size and appearance of nodules ≥ 1mm in diameter were recorded. All scans were reviewed by an experienced chest radiologist (JM) without knowledge of the intervention assignment.

Randomization

Participants were randomly assigned to receive either myo-inositol (Tsuno Food Industries Co., Ltd., Wakayama, Japan) at a dose of 9 grams orally (with water or juice) once/day for 2 weeks and then twice/day for 6 months, or placebo. The placebo powder sachet was visually identical to the active compound sachet. A dynamic allocation procedure was used to balance marginal distributions of the specified stratification factors: smoking status (current versus former), prior stage 0/I lung cancer (yes versus no) and number of dysplastic lesions at baseline (1 versus >1). All study personnel were blinded to the study codes, as was confirmed by independent review.

Follow Up

The participants were interviewed by telephone at week 2, months 1, 2, 4, 5, and 7 to 8 and were seen in person at months 3 and 6 for monitoring of compliance and drug-related adverse events. Compliance was determined from an agent diary and by unused sachet counts at each follow-up visit. Compliance was defined as ingestion of ≥ 80% of the planned doses. Smoking status was confirmed by measuring urinary cotinine at months 3 and 6. Toxicity was monitored according to the NCI Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE version 3.0). Fasting blood glucose was measured at baseline and at months 1, 3, and 6. No dose modification was made for grade 1 toxicity. For grade 2 toxicity or intolerable grade 1 adverse events (AEs) that were possibly, probably, or definitely related to study agent, study agent was stopped for up to 2 weeks. If the AE resolved, the study agent was resumed at once/day dosing for one week and then increased to full dose if there was no AE recurrence. If the AE recurred, the participant was taken off the study permanently. For grade 3 or 4 AEs that were deemed possibly, probably, or definitely related to study agent, participants were taken off study permanently. When grade 3 or 4 adverse events occurred that were judged unlikely related to the study agent, intervention was stopped for up to 2 weeks and then resumed at the same dose as prior to the AE after the AE resolved. If the AE recurred, the participant was taken off study permanently. Participants underwent a second autofluorescence bronchoscopy with BAL and bronchial brushings after 6 months on study agent, and biopsies were obtained from the same sites that were biopsied at baseline as well as any new areas that displayed abnormal fluorescence. The bronchoscopist was blinded to the intervention assignment.

Biomarker Analysis

Ki-67 Expression In Bronchial Biopsies

Unstained bronchial biopsy specimens (5-micron) were mounted on silanized glass slides (HistoBond, Marienfeld-Germany) and Ki-67 expression was determined by the method of Shi et al. (17) The primary Ki-67 antibody (1:250, Lab Vision, Fremont, CA.), and the biotinylated secondary antibody (1:500, Vector Lab) were used, followed by ABC method (Vectastain ABC Elite Kit, Vector Lab, Burlingame, CA) with diaminobenzidine (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) used as chromogen. For a negative control, the primary antibody was omitted. The percentage of positively stained cells was determined by counting a total of 100 cells in the most positively stained area in the tissue section.

BAL and Plasma Biomarkers

The potential anti-oxidative and anti-inflammatory effects of myo-inositol were determined in distal BAL and plasma collected before and after intervention. The biomarkers interrogated using ELISA were: 1) pro-inflammatory proteins: C-reactive protein, interleukin-6, and CCL-2 (all from R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN); 2) oxidant/antioxidants: myeloperoxidase (MPO, R&D Systems Minneapolis, MN), nitrotyrosine (Hycult Biotech, Plymouth Meeting, PA) and glutathione (Millipore-Calbiochem, San Diego, CA); and 3) pneumoproteins: Clara cell protein-16 (CC-16, Biovendor, Asheville, NC), surfactant protein-D (SFTPD, R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) and CCL18 (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN). Laboratory personnel were blinded to the intervention assignment. All measurements were performed in duplicate.

Assessing PI3K Activity Based on Airway Gene Expression

Matched pre- and post-treatment bronchial brushings of cytologically normal epithelium were collected during bronchoscopy from 72 subjects (n=144 samples). Total RNA was extracted using the miRNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen). Sequencing libraries were prepared using the Illumina® TruSeq® RNA Kit v2 and multiplexed in groups of six using the Illumina® TruSeq® Paired-End Cluster Kit. Each sample was sequenced on an Illumina® HiSeq® 2500 to generate paired-end 100 nucleotide reads. Demultiplexing and creation of FASTQ files were performed using Illumina CASAVA. Alignment and gene-level counts were generated using RSEM (v1.2.10) (18) and hg19 and Ensembl v74 annotation. Six samples were removed from downstream analyses based on data quality as assessed using RSeQC (v2.3.3) (19) and single nucleotide variant calls to verify that paired samples were derived from the same subject. Genes were filtered out based on a modified version of the mixture model in the SCAN.UPC package (20); a gene was included in downstream analyses if the mixture model classified it as “ “signal” in at least 15% of the samples. All subsequent analyses were conducted using R (v3.0.0). Linear modeling to identify treatment effects within complete responders (n=10 subjects in the myo-inositol arm or n=5 subjects in the placebo arm) and progressors (n=15 subjects in the myo-inositol arm or n=11 subjects in the placebo arm) was performed using the edgeR (v3.4.2) (21) and limma (v23.18.13) packages (22) using normalized voom-transformed data (23). To identify relationships between the effects of myo-inositol treatment and PI3K-pathway activation, the moderated t-statistics from the linear modeling were used to create rankings of genes for each group. GSEA (Gene Set Enrichment Analysis) (24) was used determine if genes that we previously reported to be either increased or decreased with PIK3CA overexpression in vitro (9) are significantly enriched at the extremes of the ranked lists. The RNA-Seq data from this study is available from the NCBI Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) under accession [GEO ID pending].

Outcomes

The primary endpoint of the study was defined as change in dysplasia rate on a per-participant basis, with the per-lesion analysis specified as a secondary endpoint. Secondary endpoints reported herein include change in Ki-67 labeling index in bronchial biopsies, changes in biomarker levels in BAL and plasma, and effect on airway epithelial gene expression signature for PI3K activity. We also determined whether baseline biomarker measurements were related to progression/regression of dysplasia at 6 months. Safety and AE profiles of participants enrolled in both intervention arms were also closely monitored.

Statistical Design and Analyses

The sample size for this trial was calculated as follows. The placebo group was expected to have a 20% complete response rate based on three previous NCI sponsored chemoprevention trials with similar but not identical eligibility criteria.(12, 25, 26) In our previously reported pilot study in 20 subjects, the complete response rate was 67%.(10) Assuming at least a 30% difference in the dysplasia response rates between the myo-inositol and placebo arms (20%–50%), a sample size of 50 evaluable participants per intervention arm provided 80% power (2-sided chi-square test with continuity correction; alpha=0.05). If the difference in the response rates between the treatment groups was at least 35%, the study had 90% power to detect a significant difference. Assuming a 10% drop out rate, we planned to enroll a total of 110 participants to have 100 evaluable participants.

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize participant characteristics and pathologic evaluations of the bronchial biopsy examinations. Comparison between groups was done with the Wilcoxon rank sum test for continuous variables. Pearson’s chi-square test with continuity correction or Fisher’s exact test, as appropriate for small expected cell sizes, was used to compare categorical variables. Response rates were calculated on a per-site and a per-participant basis. For the lesion-specific analysis, complete response (CR) was defined as the regression of a dysplastic lesion of any grade to one classified as being either hyperplastic or normal. Progressive disease (PD) was defined as appearance of lesions that were classified as mild dysplasia or worse, irrespective of whether the site was biopsied at baseline, or worsening of the dysplastic lesion present at baseline by two or more grades (e.g., mild dysplasia to severe dysplasia or worse). Post-intervention biopsies of metaplasia or lower that were either metaplastic or lower at baseline, or not biopsied at baseline were graded as not applicable (NA). Dysplastic lesions that were not classified as complete response, progressive disease, or not applicable were referred to as stable disease (SD).

For the participant specific analysis, CR was defined as regression of all dysplastic lesions found at baseline to lesions that were no worse than hyperplasia, as defined by the site analysis at 6 months and the appearance of no new dysplastic lesions that were graded as mild dysplasia or worse. PD was defined as progression of one or more sites by 2 more grades as defined for the lesion-specific analysis above, or the appearance of new dysplastic lesions that were mild dysplasia or worse at 6 months. Partial response (PR) was defined as regression of some but not all of the dysplastic lesions with the appearance of no new lesions that were graded as mild dysplasia or worse. Stable disease (SD) referred to participants who did not have a CR, PR, or PD. For participant-specific analysis, PR and SD were combined into one response category because minor changes like one grade change are prone to grading error. We also categorized participants as regression or stable (CR, PR, or SD) vs. progressive disease (PD) when doing the lesion specific analysis. In the comparison of treatment arms for the participant-specific assessment of response (CR vs. SD/PR vs. PD) from baseline to 6 month, a Kruskal Wallis test was used, accounting for the ordered nature of response. A multiple variable logistic regression model was used to assess the odds of progression (as opposed to CR, SD, or PR) with the variables of treatment arm, gender, smoking status (current vs. former) and maximal histologic grade in the participant (mild vs. moderate vs. severe). Generalized estimating equations (GEE) were used for the lesion specific analyses due to the varying number of lesions per participant. The association of baseline histologic grade of a lesion and baseline Ki-67 staining was also assessed using a linear regression GEE model. The percent change in Ki-67 labeling index from bronchial biopsies with dysplasia at baseline to 6 months post-intervention was compared between intervention arms using a GEE model.

Biomarker expression levels (at baseline and change from baseline) were compared between and within arms using a Wilcoxon rank sum or sign rank test. The trends in response rates by baseline marker levels (divided into quartiles) were tested using a Cochran Armitage test for trend (1-sided test). Logistic regression models were used to evaluate the impact of baseline biomarker levels (divided into quartiles) on participant level response (CR versus others; CR/PR versus others) unadjusted and adjusted for intervention arm.

All P values are two-sided, unless otherwise noted. A two-sided P value less than .05 was considered statistically significant. No adjustments for multiple comparisons were done for the secondary endpoints as this was largely an exploratory exercise. SAS version 9.3 (SAS, Inc., Cary, NC) was used for all analyses.

RESULTS

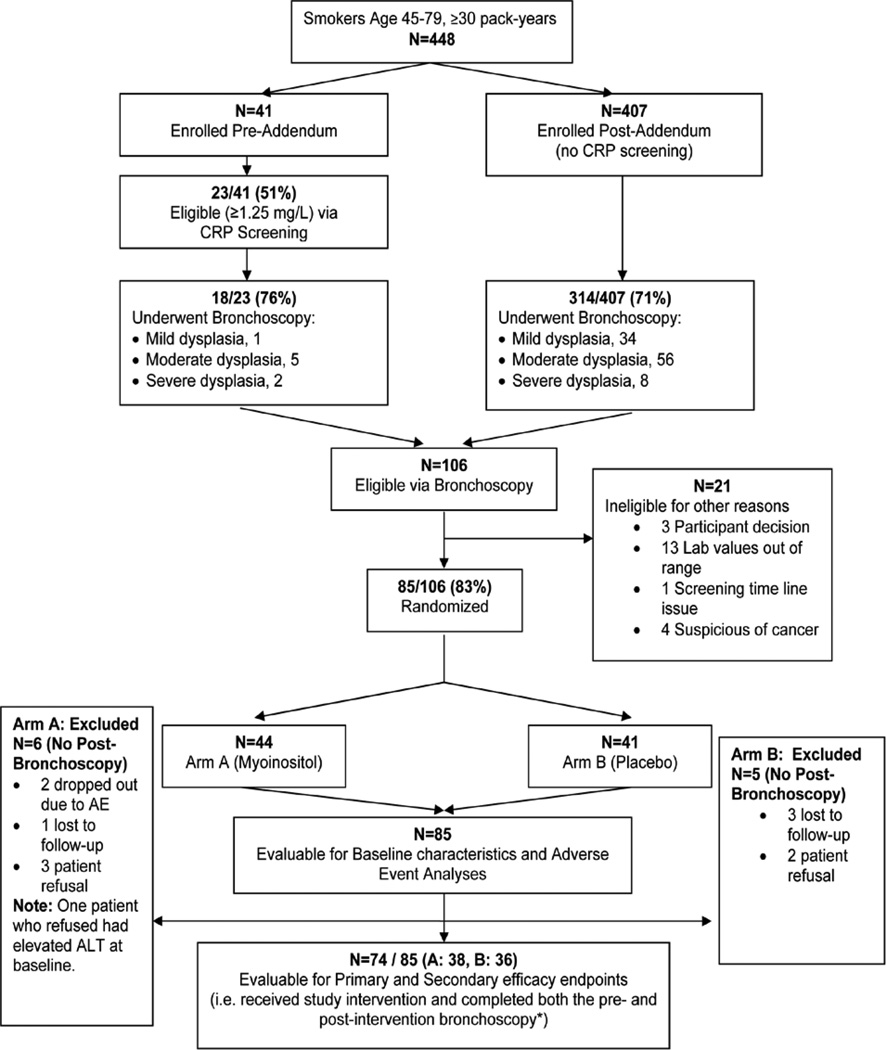

After 448 participants were screened and 85 randomized to receive placebo (41) or myo-inositol (44), the trial was closed due to slow accrual. All 85 participants were included in the baseline and AE analyses. Eleven of the 85 participants did not have a follow-up bronchoscopy due to AEs, loss to follow-up, or refusal. Therefore, 74 participants (38 myo-inositol, 36 placebo) were included in the efficacy analyses (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

CONSORT Diagram

Clinical Characteristics

Baseline characteristics of the 85 participants are shown in Table 1. There was no statistically significant difference in median age, race, body mass index, gender, self-reported smoking status, prior NSAID use, number of biopsies obtained, and number of dysplastic lesions or severity of dysplasia at baseline. Based on the baseline cotinine measurement, 6 participants in the myo-inositol group and 1 participant in the placebo group with a self-reported former smoking status were reclassified as current smokers. There was no significant difference in study arms based on this reclassification (p=0.36).

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics for Randomized Participants Receiving Study Intervention

|

myo-Inositol (N=44) |

Placebo (N=41) |

Total (N=85) |

p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 0.521 | |||

| Median | 58.5 | 58.0 | 58.0 | |

| Range | (45.0–75.0) | (46.0–79.0) | (45.0–79.0) | |

| Race | 0.592 | |||

| White | 42 (95.5%) | 38 (92.7%) | 80 (94.1%) | |

| Asian | 2 (4.8%) | 3 (7.3%) | 5 (5.9%) | |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 0.621 | |||

| Median | 27.2 | 26.0 | 26.5 | |

| Range | (21.1–36.3) | (21.0–35.2) | (21.0–36.3) | |

| Gender, N (%) | 0.352 | |||

| Female | 10 (22.7%) | 13 (31.7%) | 23 (27.1%) | |

| Male | 34 (77.3%) | 28 (68.3%) | 62 (72.9%) | |

| Smoking status, N (%) | 0.852 | |||

| Current | 27 (61.4%) | 26 (63.4%) | 53 (62.4%) | |

| Former | 17 (38.6%) | 15 (36.6%) | 32 (37.6%) | |

| Prior NSAID use | 0.492 | |||

| No | 28 (63.6%) | 29 (70.7%) | 57 (67.1%) | |

| Yes | 16 (36.4%) | 12 (29.3%) | 28 (32.9%) | |

| Dysplastic lesions identified | 0.742 | |||

| 1 Dysplastic lesion | 22 (50.0%) | 19 (46.3%) | 41 (48.2%) | |

| >1 Dysplastic lesions | 22 (50.0%) | 22 (53.7%) | 44 (51.8%) | |

| Mucosal biopsies obtained | 0.621 | |||

| Median | 6.0 | 7.0 | 7.0 | |

| Range | (1.0–14.0) | (1.0–14.0) | (1.0–14.0) | |

| Most advanced histology, N (%) | 0.112 | |||

| Mild dysplasia | 15 (34.1%) | 13 (31.7%) | 28 (32.9%) | |

| Moderate dysplasia | 28 (63.6%) | 22 (53.7%) | 50 (58.8%) | |

| Severe dysplasia | 1 (2.3%) | 6 (14.6%) | 7 (8.2%) |

Kruskal Wallis

Chi-Square

No registered participants reported prior lung cancer

No registered participants reported Hispanic or Latino ethnicity

Effects of myo-inositol on Histopathology of Bronchial Biopsies

Participant-specific Analysis

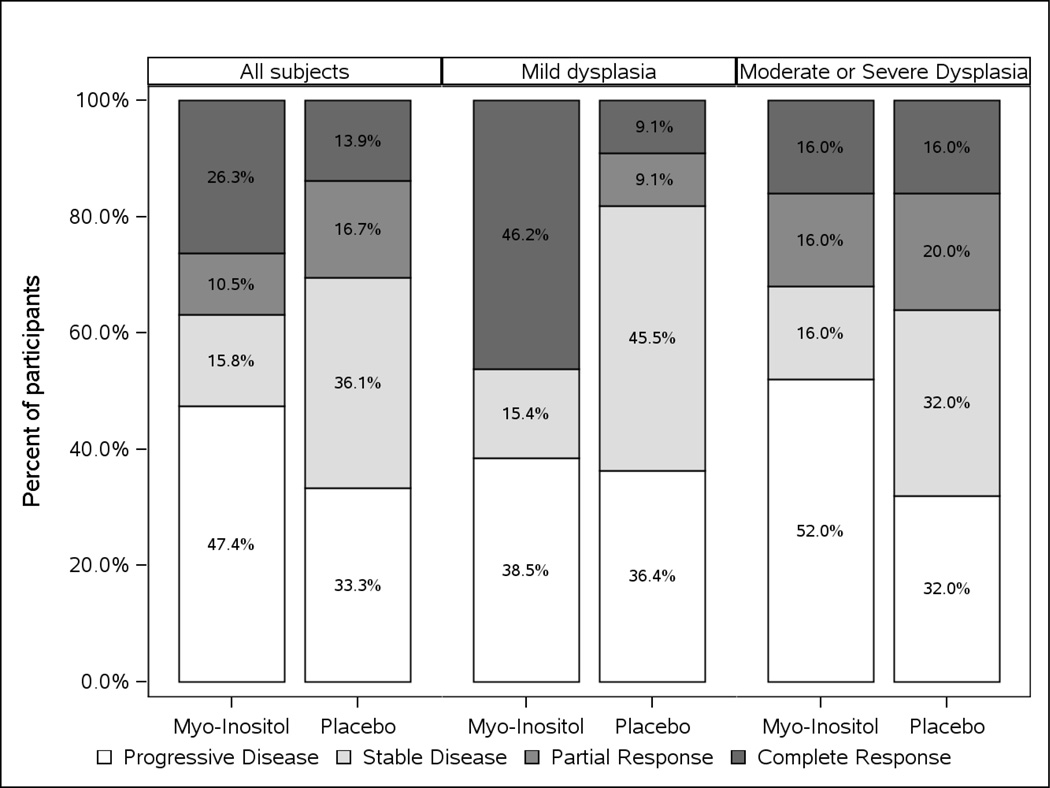

There was no statistically significant difference in response, categorized as complete response (CR) vs. partial or stable response (PR/SD) vs. progressive disease (PD), between intervention arms, p=0.76 (Figure 2). The CR rate was 26.3% in the myo-inositol group and 13.9% in the placebo group and the PD rates were 47.4% and 33.3%, respectively. The response rates in the 23 participants with a maximum histopathology grade of mild dysplasia at baseline were also not significantly different (p=0.34) with CR rates of 46.2% versus 9.1% and PD rates of 38.5% versus 36.7% in the myo-inositol and placebo arms, respectively (Figure 2). In a similar assessment of 50 participants with a maximum histopathology grade of moderate/severe dysplasia at baseline, there was no significant difference in the response rates between the intervention arms (p=0.27; Figure 2). There was no significant difference in the efficacy of myo-inositol by smoking status (Table 2). A multiple variable logistic regression model adjusting for gender, smoking status and maximum histopathology grade at baseline showed no significant difference in the odds of progression between the intervention arms.

Figure 2.

Change in Bronchial Dysplasia, by Intervention Arm

Numbers shown represent the proportion of participants with each bronchial dysplasia change state. No participants with a partial response were observed among those with Mild Dysplasia at baseline in the myo-inositol arm.

Table 2.

Response to myo-Inositol by Smoking Status Showing No Difference Between myo-Inositol and Placebo

| Smoking Status |

Participant- level Response |

myo-Inositol (N=38) |

Placebo (N=36) |

P-value† |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Current smokers | N=23 | N=23 | 0.1571 | |

| PD | 13 (56.5%) | 11 (47.8%) | ||

| SD or PR | 8 (34.8%) | 11 (47.8%) | ||

| CR | 2 (8.7%) | 1 (4.3%) | ||

| Former smokers | N=15 | N=13 | 0.881 | |

| PD | 5 (33.3%) | 1 (7.7%) | ||

| SD or PR | 2 (13.3%) | 8 (61.5%) | ||

| CR | 8 (53.3%) | 4 (30.8%) | ||

Kruskal Wallis test, considering responses as ordered; progressive (PD), then stable/partial response (SD/PR), then complete response (CR).

Lesion-specific Analysis

In the per-lesion analyses, a total of 267 lesions in 38 participants assigned to the myo-inositol arm were biopsied at baseline (31.8% dysplastic) and 265 lesions were biopsied post-intervention (20.4% dysplastic). In the placebo arm, a total of 258 lesions in 36 participants were biopsied at baseline (34.5% dysplastic) and 243 lesions were biopsied post-intervention (23.9% dysplastic). The per-lesion response rates in the myo-inositol arm were 10.2% with CR, 15.9% with SD, and12.5% with PD, and for the placebo arm the corresponding rates were 7.4%, 22.6%, and 10.3%.

CT Detected Lung Nodules

Sixty-two BCCA participants had CT prior to intervention. Of the 27 participants with no lung nodules, only 4 underwent a repeat CT scan at Month 6. Among the 39 participants with pre- and post-treatment CT data, 18 participants with 53 lesions in the myo-inositol group and 17 participants with 49 lesions in the placebo group had one or more non-calcified lung nodules at baseline, with mean (SD) sizes of 5.9 (3.8) mm and 4.1 (2.2) mm, respectively. A GEE analysis of % change in the CT nodule size from baseline to 6 months showed no difference between the intervention arms (p=0.6). Based on a nodule specific GEE analysis, there was also no significant difference between the arms (p=0.91) when looking at the nodules categorized as progressed (myo-inositol=12.5%; placebo=3.5%) versus regressed/stable (myo-inositol=87.5%; placebo=96.5%), with progression defined as any increase from baseline or appearance of new nodules and regression/stable defined as decrease from baseline and no new nodules.

Biomarker Analyses

Ki-67 in Bronchial Biopsies

Ki-67 labeling index data were available from baseline bronchial dysplasia and site-matched, post-intervention biopsy samples from 65 participants (n=33 and n=32 in the myo-inositol and placebo arms, respectively). The mean percent change in Ki-67 labeling index in the bronchial biopsies with dysplasia from baseline to 6 months in the myo-inositol arm was −22.8% compared to −6.2% in the placebo arm, which was not significantly different between the intervention arms (p=0.34).

BAL and Plasma Biomarkers

Compared with placebo, treatment with myo-inositol significantly reduced IL-6 levels in BAL over 6 months (p=0.03) and produced borderline significant effects on BAL glutathione and myeloperoxidase (p=0.06 for both) (Table 3). There were no significant effects of myo-inositol on any of the plasma biomarkers (data not shown). To determine whether any of the biomarkers predicted CR or CR/PR, we performed a series of exploratory analyses using baseline biomarker levels (in quartiles) in BAL and plasma. Irrespective of treatment status, increased baseline levels of CC16 in both BAL and plasma were associated with CR (Supplementary Table 1) and CR/PR (Supplementary Table 2). Reduced plasma levels of MPO were also significantly associated with CR/PR but not with CR.

Table 3.

Change in Biomarker Levels in Bronchoalveolar Lavage Fluid from baseline (pre) to 6 Months Post-Intervention

| Difference in post – pre levels; Median (range) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| myo-Inositol | Placebo | P* | |

| IL-6 (pg/ml) | −0.68 (−2.78 to 0.34) |

−0.27 (−1.54 to 1.89) |

0.03 |

| GSH (umol/L) | −0.246 (−1.98 to 0.48) |

−0.558 (−1.13 to 0.33) |

0.06 |

| MPO (ng/mL) | −3.457 (−8.17 to 2.77) |

−1.154 (−8.43 to 1.21) |

0.06 |

| CC16 (ng/mL) | −66.962 (−127.56 to 52.26) |

−54.323 (−144.65 to 140.84) |

0.10 |

| SFTPD (ng/ml) | −12.387 (−47.12 to 5.72) |

7.213 (−7.62 to 23.79) |

0.22 |

| CCL18 (ng/ml) | −121.470 (−1234.7 to 1122.9) |

10.702 (−684.95 to 683.25) |

0.63 |

| CCL-2 (pg/ml) | −9.2465 (−44.32 to 8.62) |

9.413 (−52.58 to 54.6) |

0.58 |

Wilcoxon Rank-Sum P-Value (for difference in absolute change by arm)

Abbreviations: CC-16, Clara cell protein-16; CRP, c-reactive protein; GSH, total glutathione; IL-6, interleukin-6; MPO, myeloperoxidase, SFTPD, surfactant protein D

CCL18, chemokine ligand 18 previously known as pulmonary and activation-regulated chemokine ; CCL-2, chemokine ligand 2 previously known as monocyte chemotactic protein 1

PI3K-Associated Gene Expression Within the Cytologically Normal Bronchial Epithelium

In order to test the previously developed hypothesis that PI3K-associated gene expression within the cytologically normal epithelium decreases with clinical response to myo-inositol (9), we evaluated PI3K-activity-related gene expression pre- vs. post-therapy amongst patients receiving myo-inositol who achieved a complete response. Overall, there was a significant inverse relationship between PI3K activity and response to myo-inositol, which was expected given our previous results which show myo-inositol inhibition of PI3K signaling (9). Specifically, we found that in participants with a complete response to myo-inositol (n=10), those genes that increase upon treatment are inversely enriched in decreased genes from our in vitro signature for PI3K activity (p = 0.002); this results suggests a decrease in PI3K activity in this group. This decrease in PI3K activity was not found among the complete responders in the placebo arm, nor among the subjects with progressive disease in either treatment arm.

Agent Compliance

Participants in the myo-inositol and placebo groups took 67.9% ± 3.8% and 79.8% ± 3.1% of the prescribed doses, respectively. There was no significant difference in response rates (CR vs. SD/PR vs. PD) between the intervention arms within compliant and non-compliant participants (Table 4).

Table 4.

Participant-Specific Analysis of Response by Intervention Arm Based on Agent Compliance

| Compliance Status |

Participant- level Response |

myo-Inositol (N=38) |

Placebo (N=35) |

P-value† |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Compliant * | N=25 | N=28 | ||

| PD | 12 (48.0%) | 9 (32.1%) | 0.73 | |

| SD or PR | 7 (28.0%) | 16 (57.2%) | ||

| CR | 6 (24.0%) | 3 (10.7%) | ||

| Non-Compliant * | N=13 | N=7 | ||

| PD | 6 (46.2%) | 3 (37.5%) | 0.91 | |

| SD or PR | 3 (23.1%) | 3 (37.5%) | ||

| CR | 4 (30.8%) | 2 (25.0%) | ||

Kruskal Wallis test.

defined as the number of sachets taken by the participant divided by the number of sachets that should have been taken by the participant based on a 6-month intervention.

Adverse Events

All adverse events (AEs) regardless of attribution were collected. At least one AE, regardless of grade or attribution, was reported by 39/44 (89%) participants in the myo-inositol arm and 34/41 (83%) participants in the placebo arm (p=0.45 for comparison between arms). Most AEs were classified as grade 1 (77.3%), with progressively fewer grade 2 (19.6%), and grade 3 (2.7%) adverse events reported. No grade 4 AEs were reported. Seven (8%) participants (n=4, myo-inositol and n=3, placebo) experienced a total of 9 grade 3 adverse events (dyspnea, dizziness, pain, arthralgia, and bilateral cataracts in the myo-inositol arm; syncope, rash, and peripheral neuropathy in the placebo arm) all of which were felt to be unlikely to be related to the study agents, except for syncope, which was possibly related. Participants in the myo-inositol arm reported a higher incidence of gastrointestinal AEs compared to the placebo arm (59% myo-inositol arm; 43% placebo arm; p=0.16). One Serious Adverse Event was reported: a grade 2 coronary artery calcification in the myo-inositol arm, deemed unrelated to study intervention.

DISCUSSION

This is the first phase IIb chemoprevention trial to examine the safety and efficacy of myo-inositol for lung cancer chemoprevention. Following on promising preclinical data and our previous small phase IIa trial showing a high bronchial dysplasia reversion rate, this trial was designed to evaluate the efficacy of a longer (6 month) myo-inositol intervention (10). Although safety and tolerability were established, there was no overall statistically significant effect on bronchial dysplasia, albeit in a study that only achieved three-quarters of its planned accrual. The goal of phase II chemoprevention trials is to identify agents that have clinically meaningful effects. Our sample size calculation was based on a ≥30% better complete response (CR) rate in the myo-inositol group versus placebo. A post-hoc sample size calculation showed that with 35 participants per group, a difference of 35% (20% versus 55%) in the dysplasia response rates, with a power of 80% and a 2-sided error rate of 0.05, would have been detectable. Thus, even with the smaller than anticipated accrual, this study had sufficient power to detect a meaningful treatment effect. myo-Inositol would likely not be considered for a phase III trial based on the 12% improvement in CR rates over placebo observed in this trial.

It is possible, and perhaps even likely, that decreased progression to higher grades of dysplasia would be more predictive of cancer prevention than dysplasia regression. In colon cancer prevention, the most effective trial model has examined progression to new polyps rather than regression of sporadic polyps (27, 28). In bronchial dysplasia, such studies would be significantly larger than our current trial and thus even more difficult to perform. Nevertheless, our data suggest potential differential effects in subpopulations within the studied cohort. A numerically higher, but statistically not significant percentage of CR was observed in the myo-inositol arm as compared to placebo (26.3% versus 13.9%); this was balanced by a non-statistically significant increase in the percentage of PD with myo-inositol (47.4% versus 33.3%). Similarly, a higher but statistically not significant mean percent change in Ki-67 expression level in the bronchial biopsies with dysplasia from baseline to 6 months was observed in the myo-inositol arm compared to the placebo arm (−22.8% compared to −6.2%, p=0.34). Furthermore, treatment with myo-inositol significantly reduced levels of IL-6, a pro-inflammatory biomarker in BAL (p=0.0317). Taken together, this consistent modulation of multiple markers suggests that there could be a subpopulation within the entire cohort that may experience benefit from myo-inositol. There is a precedent for differential responses to chemopreventive interventions within participant subgroups from the previously reported phase IIb iloprost trial, which showed a significant regression of dysplasia in former, but not current, smokers (29). In our study, there was no significant interaction of smoking status and treatment arm using participant reported or urinary cotinine verified smoking status. The effect of short-term changes in the smoking status on bronchial dysplasia in 30% of the participants could not be evaluated in a phase II study of this size. Thus we were unable to identify a myo-inositol-sensitive subgroup, if one exists.

The PI3K/Akt signaling pathway regulates diverse cellular function including proliferation and survival. We have previously demonstrated significantly increased pAkt in dysplastic lesions versus hyperplastic/metaplastic lesions before myo-inositol treatment (30). Following myo-inositol treatment, significant decrease in pAkt was observed in dysplastic (P < 0.01) but not hyperplastic/metaplastic lesions (P > 0.05). In vitro, myo-inositol decreased endogenous and tobacco carcinogen-induced activation of Akt in immortalized human bronchial epithelial cells, which decreased cell proliferation and induced a G(1)-S cell cycle arrest.(30) These results show that the phenotypic progression of premalignant bronchial lesions from smokers correlates with increased activation of Akt and that it is a target of myo-inositol. Similarly, examination of gene expression in cytologically normal bronchial epithelial cells from participants in the same phase IIa study showed that myo-inositol was associated with reduction in PI3k activity among those smokers who had regression of their premalignant lesions (9). This finding is confirmed in the current study. Among those smokers who had a complete response to myo-inositol, the gene-expression signature of PI3K activity was reduced in bronchial epithelial cells post-treatment, whereas there was no significant reduction in this signature among the clinical non-responders to myo-inositol nor in the placebo arm regardless of clinical response. While the sample size was limited and varied between response subgroups, these results suggest that PI3k associated gene expression could serve as an intermediate biomarker of therapeutic efficacy for myo-inositol. Whether selection of subjects with activation of the PI3K pathway would lead to a higher complete response rate requires further investigation.

The advantage of using bronchial dysplasia for phase II chemoprevention trials is that these lesions can be localized and biopsied using white light and autofluorescence bronchoscopy for histopathology confirmation. The presence of dysplasia is a known risk marker for lung cancer both in the central airways and the peripheral lung.(31–33) However, there has been a change in the lung cancer cell type distribution worldwide. The prevalence of centrally located squamous cell carcinomas has been steadily decreasing and replaced by an increase in adenocarcinomas,(34) which are usually located in the peripheral lung beyond the range of sampling by standard flexible bronchoscopes. This is reflected in a steady decline in proportion of smokers found to have bronchial dysplasia in the last decade.(35) This contributed to the reported difficulty in identifying participants for the current clinical trial. Alternative intermediate endpoint biomarkers, such as CT detected non-calcified lung nodules are needed for future phase II lung cancer chemoprevention trials.(36) CT scan was done in this study to rule out lung cancer prior to starting treatment with myo-inositol or placebo. However, the study population was selected for the presence of central lung bronchial dysplasia rather than presence of peripheral lung nodules, and thus was not sufficiently powered to robustly examine the effect of myo-inositol on CT-detected lung nodules.

In summary, despite a reduction in pro-inflammatory cytokine and oxidant level in BAL, the slight but statistically insignificant increase in CR and reduction in Ki-67 labeling index in bronchial biopsies after treatment with myo-inositol compared to placebo was accompanied by an increase in PD rate of similar magnitude. This suggests that a targeted approach based on an understanding of the underlying molecular alterations (9) is probably needed to determine if myo-inositol has a role as a chemopreventive agent in a more defined cohort.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Research Support: Supported by a contract from the National Cancer Institute (N01CN35000).

The authors gratefully acknowledge the following people for their technical assistance in participant recruitment, bronchoscopy, sample processing, data management, and immunohistochemistray assays: Sharon Gee, Jennifer Kidd, Myles McKinnon, Bimmie Kalan, Lori Bergstrom, Meghan Muse, Hanqiao Liu, Huiqing Si, Cindy Fitting, Mary Fredericksen, Cindy Beinhorn, Barbara Greguson, Christopher Zima, and Dr. Steven Kye. We thank Fumi Tsuno, Tsuno Food Industries Co., Ltd., Wakayama, Japan for supplying the myo-inositol to NCI DCP. The authors also gratefully acknowledge Colleen Garvey, Sharon Kaufman, and Karrie Fursa for their assistance with study design, administration, and manuscript preparation.

Footnotes

Clinical Trial Registration: www.clinicaltrials.gov; NCT00783705

The authors have no conflict of interest

REFERENCES

- 1.Stewart BaW CP, editor. The World Cancer Report 2014: International Agency for Research on Cancer. 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Siegel R, Ma J, Zou Z, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2014. CA Cancer J Clin. 2014;64:9–29. doi: 10.3322/caac.21208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tong L, Spitz MR, Fueger JJ, Amos CA. Lung carcinoma in former smokers. Cancer. 1996;78:1004–1010. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0142(19960901)78:5<1004::AID-CNCR10>3.0.CO;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Peto R, Darby S, Deo H, Silcocks P, Whitley E, Doll R. Smoking, smoking cessation, and lung cancer in the UK since 1950: combination of national statistics with two case-control studies. Bmj. 2000;321:323–329. doi: 10.1136/bmj.321.7257.323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sporn MB, Newton DL. Chemoprevention of cancer with retinoids. Fed Proc. 1979;38:2528–2534. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Szabo E, Mao JT, Lam S, Reid ME, Keith RL. Chemoprevention of lung cancer: Diagnosis and management of lung cancer, 3rd ed: American College of Chest Physicians evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest. 2013;143:e40S–e60S. doi: 10.1378/chest.12-2348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Estensen RD, Wattenberg LW. Studies of chemopreventive effects of myo-inositol on benzo[a]pyrene-induced neoplasia of the lung and forestomach of female A/J mice. Carcinogenesis. 1993;14:1975–1977. doi: 10.1093/carcin/14.9.1975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wattenberg LW, Estensen RD. Chemopreventive effects of myo-inositol and dexamethasone on benzo[a]pyrene and 4-(methylnitrosoamino)-1-(3-pyridyl)-1-butanone-induced pulmonary carcinogenesis in female A/J mice. Cancer Res. 1996;56:5132–5135. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gustafson AM, Soldi R, Anderlind C, Scholand MB, Qian J, Zhang X, et al. Airway PI3K pathway activation is an early and reversible event in lung cancer development. Sci Transl Med. 2010;2:26ra5. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3000251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lam S, McWilliams A, LeRiche J, MacAulay C, Wattenberg L, Szabo E. A phase I study of myo-inositol for lung cancer chemoprevention. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2006;15:1526–1531. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-06-0128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lam S, Kennedy T, Unger M, Miller YE, Gelmont D, Rusch V, et al. Localization of bronchial intraepithelial neoplastic lesions by fluorescence bronchoscopy. Chest. 1998;113:696–702. doi: 10.1378/chest.113.3.696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lam S, leRiche JC, McWilliams A, Macaulay C, Dyachkova Y, Szabo E, et al. A randomized phase IIb trial of pulmicort turbuhaler (budesonide) in people with dysplasia of the bronchial epithelium. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:6502–6511. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-0686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lam S, Leriche JC, Kijek K, Phillips D. Effect of bronchial lavage volume on cellular and protein recovery. Chest. 1985;88:856–859. doi: 10.1378/chest.88.6.856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Travis W. Histological typing of lung and pleural tumors. Berlin-Heidelberg: Springer-Verlag; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 15.McWilliams A, Mayo J, MacDonald S, leRiche JC, Palcic B, Szabo E, et al. Lung cancer screening: a different paradigm. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2003;168:1167–1173. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200301-144OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McWilliams AM, Mayo JR, Ahn MI, MacDonald SL, Lam SC. Lung cancer screening using multi-slice thin-section computed tomography and autofluorescence bronchoscopy. J Thorac Oncol. 2006;1:61–68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shi SR, Key ME, Kalra KL. Antigen retrieval in formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissues: an enhancement method for immunohistochemical staining based on microwave oven heating of tissue sections. J Histochem Cytochem. 1991;39:741–748. doi: 10.1177/39.6.1709656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li B, Dewey CN. RSEM: accurate transcript quantification from RNA-Seq data with or without a reference genome. BMC Bioinformatics. 2011 Aug 4;12:323. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-12-323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang L, Wang S, Li W. RSeQC:quality control of RNA-seq experiments. Bioinformatics. 2012 Aug 15;28(16):2184–2185. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts356. Epub 2012 Jun 27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kusko RL, Brothers Ii JF, Tedrow J, Pandit K, Huleihel L, et al. Integrated Genomics Reveals Convergent Transcriptomic Networks Underlying COPD and IPF. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2016 Apr 22; doi: 10.1164/rccm.201510-2026OC. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Robinson MD, McCarthy DJ, Smyth GK. edgeR: a Bioconductor package for differential expression analysis of digital gene expression data. Bioinformatics. 2010 Jan 1;26(1):139–140. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp616. Epub 2009 Nov 11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ritchie ME, Phipson B, Wu D, Hu Y, Law CW, Shi W, Smyth GK. limma powers differential expression analyses for RNA-sequencing and microarray studies. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015 Apr 20;43(7):e47. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv007. Epub 2015 Jan 20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Law CW, Chen Y, Shi W, Smyth GK. voom: Precision weights unlock linear model analysis tools for RNA-seq read counts. Genome Biol. 2014 Feb 3;15(2):R29. doi: 10.1186/gb-2014-15-2-r29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Subramanian A, Tamayo P, Mootha VK, Mukherjee S, Ebert BL, Gillette MA, Paulovich A, Pomeroy SL, Golub TR, Lander ES, Mesirov JP. Gene set enrichment analysis: a knowledge-based approach for interpreting genome-wide expression profiles. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005 Oct 25;102(43):15545–15550. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0506580102. Epub 2005 Sep 30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lam S, MacAulay C, Le Riche JC, Dyachkova Y, Coldman A, Guillaud M, et al. A randomized phase IIb trial of anethole dithiolethione in smokers with bronchial dysplasia. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2002;94:1001–1009. doi: 10.1093/jnci/94.13.1001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lam S, Xu X, Parker-Klein H, Le Riche JC, Macaulay C, Guillaud M, et al. Surrogate end-point biomarker analysis in a retinol chemoprevention trial in current and former smokers with bronchial dysplasia. Int J Oncol. 2003;23:1607–1613. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Baron JA, Cole BF, Sandler RS, Haile RW, Ahnen D, Bresalier R, et al. A randomized trial of aspirin to prevent colorectal adenomas. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:891–899. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa021735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sandler RS, Halabi S, Baron JA, Budinger S, Paskett E, Keresztes R, et al. A randomized trial of aspirin to prevent colorectal adenomas in patients with previous colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:883–890. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa021633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Keith RL, Blatchford PJ, Kittelson J, Minna JD, Kelly K, Massion PP, et al. Oral iloprost improves endobronchial dysplasia in former smokers. Cancer Prev Res (Phila) 2011;4:793–802. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-11-0057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Han W, Gills JJ, Memmott RM, Lam S, Dennis PA. The chemopreventive agent myoinositol inhibits Akt and extracellular signal-regulated kinase in bronchial lesions from heavy smokers. Cancer Prev Res (Phila) 2009 Apr;2(4):370–376. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-08-0209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ishizumi T, McWilliams A, MacAulay C, Gazdar A, Lam S. Natural history of bronchial preinvasive lesions. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2010;29:5–14. doi: 10.1007/s10555-010-9214-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jeremy George P, Banerjee AK, Read CA, O'Sullivan C, Falzon M, Pezzella F, et al. Surveillance for the detection of early lung cancer in patients with bronchial dysplasia. Thorax. 2007;62:43–50. doi: 10.1136/thx.2005.052191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lam S, Szabo E. Preinvasive Endobronchial Lesions: Lung Cancer Precursors and Risk Markers? Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2015 Dec 15;192(12):1411–1413. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201508-1668ED. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lortet-Tieulent J, Soerjomataram I, Ferlay J, Rutherford M, Weiderpass E, Bray F. International trends in lung cancer incidence by histological subtype: adenocarcinoma stabilizing in men but still increasing in women. Lung Cancer. 2014;84:13–22. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2014.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jen RLS, Lam S. Detection and Treatment of Preneoplastic Lesions. In: Roth JA, Cox JD, Hong WK, editors. Lung Cancer. Fourth. John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 2014. Lung Cancer, 4rd Edition. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pinsky PF, Nath PH, Gierada DS, Sonavane S, Szabo E. Short- and long-term lung cancer risk associated with noncalcified nodules observed on low-dose CT. Cancer Prev Res (Phila) 2014;7:1179–1185. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-13-0438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.