Abstract

The participation of women in the Japanese labor force is characterized by its M-shaped curve, which reflects decreased employment rates during child-rearing years. Although, this M-shaped curve is now improving, the majority of women in employment are likely to fall into the category of non-regular workers. Based on a review of the previous Japanese studies of the health of non-regular workers, we found that non-regular female workers experienced greater psychological distress, poorer self-rated health, a higher smoking rate, and less access to preventive medicine than regular workers did. However, despite the large number of non-regular workers, there are limited researches regarding their health. In contrast, several studies in Japan concluded that regular workers also had worse health conditions due to the additional responsibility and longer work hours associated with the job, housekeeping, and child rearing. The health of non-regular workers might be threatened by the effects of precarious employment status, lower income, a lower safety net, outdated social norm regarding non-regular workers, and difficulty in achieving a work-life balance. A sector wide social approach to consider life course aspect is needed to protect the health and well-being of female workers’ health; promotion of an occupational health program alone is insufficient.

Keywords: Non-regular work, Precarious employment, Regular work, Gender role, Social determinants of health, Decent work, Work-life balance

Background

The participation of women in the Japanese labor force by age groups is distinguished by its M-shaped graph characteristic, which reflects the decreased employment rates during child-rearing years. Both female educational attainment and an increase in career-minded women have resulted in an increase over the last decades of women in the working age population (20–40 years old). Their labour force participation rate increased from around 50% to 70% during the years of 1975 to 2014 among the working age population1). However, across the total population, the Japanese female labor force participation rate still remains less than 50% and is less than that for men.

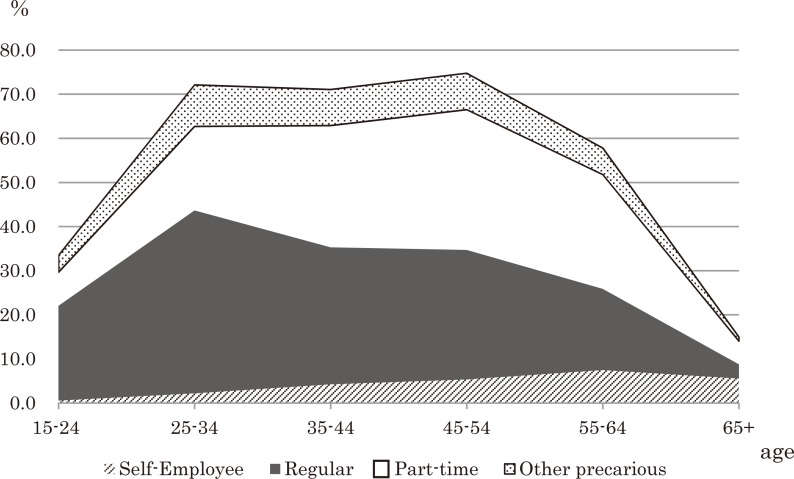

In Japan, the majority of employed women are more likely categorized as non-regular workers (Table 1). Non-regular workers includes part-time workers and other precarious employment groups such as dispatched workers, contract workers, and temporary employees. Additionally, half of the women aged 15 years and over do not work outside the home for pay. This non-working population is mainly composed of retirees, housewives, and students. While the labor force participation rate among 25–54-year-old women is around 70%, and thus would seem to resolve the M-shaped curve, the majority of these women work as non-regular workers in 2015, as shown in Fig. 12). The health of non-regular workers is of great concern because the labor force among middle-aged women and women of child-rearing ages is mainly composed of workers with non-regular employment.

Table 1. Japanese labor force overview by sex and working status.

| Men | Women | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10,000 persons |

% | 10,000 persons |

% | |||

| Population aged >15 years old | 5,328 | 5,728 | ||||

| Non Labor force population | 1,580 | 29.7 | 2,887 | 50.4 | ||

| Labor force population | 3,747 | 70.3 | 2,841 | 49.6 | ||

| Self-employee | 407 | 10.9 | 136 | 4.8 | ||

| Family employee | 30 | 0.8 | 132 | 4.6 | ||

| Regular workers | 2,261 | 60.3 | 1,042 | 36.7 | ||

| Regular workers (managers) | 262 | 7.0 | 85 | 3.0 | ||

| Part-time workers | 312 | 8.3 | 1,053 | 37.1 | ||

| Dispatched workers | 50 | 1.3 | 76 | 2.7 | ||

| Contract employees | 154 | 4.1 | 133 | 4.7 | ||

| Entrusted employees | 75 | 2.0 | 43 | 1.5 | ||

| Others | 42 | 1.1 | 41 | 1.4 | ||

| Unemployment | 134 | 3.6 | 88 | 3.1 | ||

| Unknown from the data | 20 | 0.5 | 12 | 0.4 | ||

| Total (Labor force population) | 3,747 | 100.0 | 2,841 | 100.0 | ||

Source: Labour Force Survey 2015. Statistics Bureau, Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications2).

Fig. 1.

Labor force participation rates of women by age group and employment type in 2015.

Source: Labour Force Survey 2015.

Statistics Bureau, Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications.

Some women choose to be non-regular workers because they prefer the flexible schedule to keep their work-life balance. Other women, by contrast, are easily drawn into a vicious cycle of precarious employment in spite of their desire to be regular workers because it is difficult to change the career from non-regular workers to regular workers in the Japanese labor market. According to a Labour Force Survey, among non-regular female workers who were asked why they chose non-regular work, 27.6% preferred flexible working schedule, 16.6% wanted to maintain a work-life balance, and 12.3% cited the lack of regular employment3). Non-regular female workers have a variety of work preferences.

The aim of this article is to report the findings of previous studies on the health status of non-regular workers, and to describe the particular working situation among Japanese women with non-regular employment. First, we will briefly review the general findings on the association between precarious employment and health. Next, we will review the current health status of women with non-regular employment in Japan, and consider reasons for their transition into vulnerable conditions. Finally, we will introduce a particularly challenging situation in Japan: the health of highly educated women with precarious employment.

Findings from Previous Studies: Associations between Non-regular Workers and Health

Precarious employment, including non-regular workers in Japan, is known globally as a social determinant of health; the World Health Organization (WHO) has drawn attention to its effects on workers’ health4). Several review articles have concluded that precarious employment is associated with psychological morbidity5, 6).

We found a limited number of studies that compared the health status of non-regular workers with that of regular workers in Japan. Non-regular workers often encounter inferior working conditions that are detrimental to their health. Among full-time workers, non-regular workers tend to report poorer self-rated health than regular workers7). Single female non-regular employed women had more psychological distress compared to regular workers8). The lack of participation in decision-making in work settings was significantly associated with a higher risk of psychological distress at follow-up after a year among non-regular female employees9). As cohort study showed that part-time workers had a higher risk for mortality than regular workers10). Moreover, female non-regular workers were more likely to be smokers compared to regular workers, even with adjustment for socioeconomic status and household income7). Non-regular workers also had less access to the preventive health care11).

In Japan, several studies concluded that regular workers also had worse health status due to additional responsibilities and longer work hours12, 13). Owing to various work preferences, both regularly employed and non-regularly employed women had different factors that threatened their health. A previous nationally representative survey suggested that a shift toward diverse employment patterns might be a cause of deteriorating health among the entire working population, regardless of employment status14).

Why does Precarious Employment Cause Workers’ Health to Deteriorate?

Research on the association between non-regular employment and health has suggested possible factors that are often shared by non-regular workers: effects of precarious employment, lower income, lower safety net, and difficulty achieving work-life balance.

Effects of precarious employment

Non-regular work implies precarious employment, i.e. uncertainty in employment continuation, affect the workers’ social role at work and possibly mental health. In addition, non-regular workers who provide main household income as well as basic household income worry about continued employment for household support.

Non-regular job tend to discourage the creation of networks or teams in the workplace; this working culture can make non-regular workers feel isolated and prevent them from gaining social capital in their working life. In this way, multifaceted difficulties still remain to cause vulnerable conditions for non-regular working women in Japan.

The fixed disparity in society that results from employment status could be connected to increased anxiety and fear about the future, and to a feeling of distrust that contributes to the deterioration of people’s health.

Lower income and lower safety net among Japanese non-regular workers

The average income of working women in Japan is lower than that of men. About 65% of women who work make an annual income of less than 3 million yen (US$30,000), while only 24% of working men are in the same income category15). The average salary and lifetime earnings differ by sex; even among non-regular workers, women receive lower salaries16).

One common reason that is given to explain this discrepancy is that fewer women than men are promoted to managerial levels. Educational background is known as an important factor in deciding workers’ incomes, and in fact, the educational attainment among working women today in Japan still tends to be less than that of men17) in spite of keeping higher educational level among OECD countries18). Another factor could be women’s shorter job histories compared with men, as a result of leaving work for giving birth and raising their children. Furthermore, women may tend to work in industries that pay lower wages. Since women make a lower salary irrespective of marital status, unemployed women and women who are non-regular employees are at an increasing risk of poverty as they get older. Moreover, the marriage intention in Japan, is decreasing among the younger population in non-regular workers who will live alone19).

This problem will become more apparent in the future; if the situation continues as it is, the number of poor, older women will increase. The effects of poverty on health: include deterioration of food quality and quality of life, decreased access to health care, inferior living environment, deficient information, minimal education and more seriously, increased risk of illness caused by social exclusion20). A lower income provides a lower quality of life in this capitalist economic system. The chain of poverty, in which the first generation produces a second generation similar to itself, should and can be avoided.

Non-regular workers receive safety net, or social welfare compare to regular workers. Non-regular employees often miss out on public support that they should receive. A Japanese study revealed that non-regular employees with children, notably single mothers, tend to drop out of the social security system (e.g., health insurance)21). This situation is seen as relevant to the deterioration of single mothers’ health22). According to a review that analyzed articles by the extent of the welfare state23), non-regular workers’ health was not as negatively impacted in higher welfare state countries. Thus, having an equal safety net might protect non-regular workers’ health.

Outdated social norm of non-regular workers

One more aspect of the Japanese labor culture that should be mentioned is the recognition of female non-regular employees as workers who support their families, because part-time jobs for married women were regarded as acceptable non-regular work in former generations. To test this hypothesis, data for college graduate female of a national university in a metropolitan area were analyzed descriptively. The results showed that most non-regular employed alumnae were married, had children, and were less engaged in responsible jobs requiring long working hours16). However, it should be noted that married women who work part-time for low wages receive the benefits of tax exemption, health insurance, and a pension. We cannot predict the sustainability of the social protections for married women, as explained above. Such regulatory protections in Japan may engender trust in married, non-regular employees regarding their place in society.

The difficulty of sustaining a work-life balance

In the present day, many women employees tend to stop their paid work for family reasons such as marriage, childbirth, and caregiving. These choices are encouraged by Japanese cultural norms, which assume that women should work for their families.

Working women spent an average of 215 minutes doing housekeeping, while working men spent an average of just 42 minutes per day on the same tasks in 201124). This suggests that husbands may be unwilling to participate in housework, and thus women have to work at home for their family after finishing their paid work day. This phenomenon reflects Japanese cultural norms dictating that women should remain at home rather than work outside the home, as well as the real difficulty of continuing to work while raising children. Around 60% of Japanese women quit their job after having their first child. Indeed, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) has urged the Japanese government to improve working conditions for women25).

Since a work-life balance is difficult to sustain, single mothers tend to choose non-regular work, and thus receive lower salaries. The OECD also reported that single mothers in Japan had the highest poverty rate among OECD countries, and that the social redistribution system is not adequate. Thus, working single mothers are in vulnerable situations created by the multiple burden of low income and low safety net and the difficulty of achieving a work-life balance.

A Particular Case in Japan: Precarious Employment in Academia and the Health of Women

Higher educational attainment is correlated with better health29). However, the academic sector in Japan is currently experiencing a change from its general historical norm.

The fluidity of employment contracts is extending further into the research field in education. The rate of non-regular employment for researchers in universities and research institutions is higher than that for general workers at 52% (194,064 people); many researchers have completed a doctoral degree, and have thus held unstable academic positions for long periods of time, including part-time, temporary, or fixed-term posts26). Two main reasons are put forward to explain the increase in precarious employment for academic researchers: one is the significant increase in doctorates awarded since the 1990s when the government made graduate school education a priority; another is the growing financial burden on universities caused by declining birth rates, which has necessitated switching researchers from permanent to non-regular posts as fellows. However, careers and health status among female researchers have different challenges from those of male researchers.

Academic achievement for women in Japan has consistently improved over the past 20 years, and the number of women who go on to university (including junior college) has increased at the same rate that it has for men (57.0% vs. 52.2%)26). The number of women going on to graduate school is also increasing, with 33.1% of female students enrolled in doctoral programs.

The most common career step following completion of one’s doctoral degree is a research position. However, while the number of women in Japan who are becoming researchers is gradually increasing, that rate has remained below 14.0%, the lowest among OECD member countries27). Universities that are research institutions have a relatively high rate of enrollment of female researchers, but even then, the proportion of permanent employees who are women declines with higher job classifications: 31.6% of lecturers, 23.2% of associate professors, and 15% of professors are women. A survey targeting national universities found that while the overall number of women who were part-time lecturers was 23.1%, the number who held a full-time teaching position was 17.6%, and the proportion of women under 60 years of age who did not hold a full-time position was 52.1%28). These data was suggested that the majority of female researchers work their entire career in precarious employment situations such as part-time lecturing and postdoctoral fellowships.

Social epidemiological research has suggested that people with higher education levels tend to have better health29). However, it is unclear whether precarious employment contracts affect the health of highly educated workers. Due to the lack of stable positions, a large number of researchers teach at multiple universities as part-time lecturers. Furthermore, it is difficult to investigate the health status of part-time lecturers, particularly women, because they are not included as a target of health care in a university.

Recent surveys carried out by the Union of University Part-time Lecturers—Hijokin Koshi Kumiai (2001, 2003, and 2007)—help us understand their collective health status30).

In total, 1,907 part-time lecturers answered the questions in 2001, 2003, and 2007. The average age of respondents, many of whom specialized in the humanities and social sciences, was: 46.3 years, with 42% (2001) women; 46.7 years, with 55% (2003) women; and 47.5 years, with 44% (2007) women. Among these women, the proportion of those who worked exclusively part-time in universities was 86.4%, 84.6%, and 74.6%, respectively. In other words, the majority of female part-time lecturers held multiple fragmented jobs to maintain their careers. These women gave an average of 9.2 weekly lectures at 3.1 schools (2007, same thereafter). Fewer than half (41%) had an average annual income below 2.5 million yen, with 13% having social insurance premiums (national health insurance and national pension plan).

In the conclusions of these surveys, the reasons for the health issues of female part-time researches were frequently cited as: psychosomatic stresses resulting from life events such as marriage and childbirth, and poor social security.

While these issues are generally seen among women in precarious employment, several interacting factors are thought to be relevant to the specific situation of researchers. These include: the lack of a secure, favorable research environment, which directly affects the ability to plan a career trajectory; the disturbing lack of transparency in human resources and exclusive employment systems for researchers; and, the prevalence of overt gender discrimination in the male-centric “research community” (at least, many female researchers feel this way). It will be necessary to clarify the ways in which these factors affect the health status of women who work as academic researchers.

Conclusion

In this report, we found that Japanese women who are non-regular workers tend to have a reduced health status due to precarious employment and the lack of social protection. However, more evidence is needed to clarify the health of Japanese women according to their employment status.

Due to disparity of welfare and benefits among workers, non-regular workers’ health might be under threat. Non-regular workers seem to be excluded from a regular income and a safety net. Moreover, the Japanese labor market does not allow easy transition between employment categories, and non-regular workers tend to remain in those positions for longer periods. Therefore, non-regular workers who cannot achieve regular employment may be the least motivated to work and may have stress because of their situation. Given that non-regular work is associated with lower incomes and less safety, these workers are more vulnerable to an unsustainable lifestyle. The vicious cycle of non-regular work and poverty arguably influences the next generation; all sectors of society should engage in efforts to prevent this from continuing. We also found that vulnerable populations such as single woman or single mothers, and particular job categories, such as work in an academic field, easily fall into a vicious cycle to work that interfere with work choices.

Japanese women face difficulties in achieving work-life balance because they work hard at housekeeping tasks for their families after returning home from their paid work. This aspect is also relevant to women employed as regular full-time workers who have to work long in the company and to work at home as well. This work-life hardship is now recognized by the government, which has just started to extend a helping hand to women to prevent a gender gap in labor participation and from Shoshika, declining birthrate regardless of employment status.

The Japanese government has recently implemented a new policy to support women through the Act on Promotion of Women’s Participation and Advancement in the Workplace (2016), and this policy itself is a constructive change. As one studied showed that the countries where their welfare state is relatively higher support non-regular workers to protect from their deterioration of health while non-regular workers under the less supportive countries suffer from poor health23). In this regard, a social welfare system that protects non-regular workers should be considered as a conceptual framework from a various aspects related to health; these includes individual factors (e.g., behavior, education) and social factors (e.g., policy, culture, welfare)31). Health disparities based on employment patterns should at least be reduced in a society like Japan, where the laws and regulations for occupational safety and industrial health are applicable to every worker.

The sector wide approach should be composed of well-designed supports from life course aspects. A support for keeping a daily work-life balance such as childrearing and housekeeping and a support for particular concerns for non-regular workers in working settings such as social security and observance of occupational health regulations should be included.

References

- 1.Gender Equality Bureau, Cabinet Office. 2015. http://www.gender.go.jp/about_danjo/whitepaper/h27/zentai/html/honpen/b1_s02_01.html. Accessed May 19, 2016 (in Japanese).

- 2.Statistics Bureau, Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications Labour Force Survey 2015. http://www.stat.go.jp/data/roudou/sokuhou/4hanki/dt/index.htm. Accessed May 19, 2016.

- 3.Statistics Bureau, Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications Labour Force Survey 2015.

- 4.Commission on Social Determinants of Health (2008). Chapter 7. Fair employment and decent work. 72–83. In: Closing the gap in a generation: health equity through action on the social determinants of health. Final Report of the Commission on Social Determinants of Health, World Health Organization, Geneva. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Virtanen M, Kivimäki M, Joensuu M, Virtanen P, Elovainio M, Vahtera J (2005) Temporary employment and health: a review. Int J Epidemiol 34, 610–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tompa E, Scott-Marshall H, Dolinschi R, Trevithick S, Bhattacharyya S (2007) Precarious employment experiences and their health consequences: towards a theoretical framework. Work 28, 209–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tsurugano S, Inoue M, Yano E (2012) Precarious employment and health: analysis of the Comprehensive National Survey in Japan. Ind Health 50, 223–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Inoue A, Kawakami N, Tsuno K, Tomioka K, Nakanishi M (2013) Organizational justice and psychological distress among permanent and non-permanent employees in Japan: a prospective cohort study. Int J Behav Med 20, 265–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Inoue A, Kawakami N, Tsuno K, Tomioka K, Nakanishi M (2013) Organizational justice and psychological distress among permanent and non-permanent employees in Japan: a prospective cohort study. Int J Behav Med 20, 265–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Honjo K, Iso H, Ikeda A, Fujino Y, Tamakoshi A; JACC Study Group (2015) Employment situation and risk of death among middle-aged Japanese women. J Epidemiol Community Health 69, 1012–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Inoue M, Tsurugano S, Nishikitani M, Yano E (2012) Full-time workers with precarious employment face lower protection for receiving annual health check-ups. Am J Ind Med 55, 884–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Seto M, Morimoto K, Maruyama S (2006) Work and family life of childrearing women workers in Japan: comparison of non-regular employees with short working hours, non-regular employees with long working hours, and regular employees. J Occup Health 48, 183–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sugawara N, Yasui-Furukori N, Sasaki G, Tanaka O, Umeda T, Takahashi I, Danjo K, Matsuzaka M, Kaneko S, Nakaji S (2013) Gender differences in factors associated with suicidal ideation and depressive symptoms among middle-aged workers in Japan. Ind Health 51, 202–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nishikitani M, Nakao M, Tsurugano S, Yano E (2012) The possible absence of a healthy-worker effect: a cross-sectional survey among educated Japanese women. BMJ Open 2, 5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.National Tax Agency Survey on Salary in Private Sector 2013. https://www.nta.go.jp/kohyo/tokei/kokuzeicho/minkan2013/minkan.htm. Accessed May 22, 2016.

- 16.Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. Basic Survey on Wage Structure, 2015, Figure 6 (in Japanese). http://www.mhlw.go.jp/toukei/itiran/roudou/chingin/kouzou/z2015/index.html. Accessed September 30, 2016.

- 17.Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology. School Basic Survey 2014. Table 4 (Total) http://www.e-stat.go.jp/SG1/estat/List.do?bid=000001015843&cycode=0. Accessed May 22, 2016.

- 18.OECD Education at a Grance 2014, Japan. https://www.oecd.org/edu/Japan-EAG2014-Country-Note.pdf. Accessed September 30, 2016.

- 19.Special Report on the Longitudinal Survey of Newborns in the 21st Century and the Longitudinal Survey of Adults in the 21st Century: Ten-Year Follow-up, 2001–2011, Figure 2 (in Japanese) http://www.mhlw.go.jp/toukei/saikin/hw/judan/tokubetsu13/index.html. Accessed September 30, 2016.

- 20.Aya Abe (2011) Jakusha no Ibasho ga Nai Shakai: Poverty/ Disparity, and Social inclusion. Kodansha, Tokyo (in Japanese). [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cabinet Office, Government of Japan White Paper on Children and Young People 2014. Chapter 3–3 Child poverty. http://www8.cao.go.jp/youth/whitepaper/h26honpen/b1_03_03.html (in Japanese). Accessed May 15, 2016.

- 22.Kachi Y, Inoue M, Nishikitani M, Yano E (2014) Differences in self-rated health by employment contract and household structure among Japanese employees: a nationwide cross-sectional study. J Occup Health 56, 339–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kim IH, Muntaner C, Vahid Shahidi F, Vives A, Vanroelen C, Benach J (2012) Welfare states, flexible employment, and health: a critical review. Health Policy 104, 99–127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Statistics Bureau, Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications Time Use and Leisure Activities Survey 2011. http://www.stat.go.jp/data/shakai/2011/gaiyou.htm. Accessed May 15, 2016.

- 25.Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development “Better Policy” Series. JAPAN Advancing the third arrow for a resilient economy and inclusive growth. 2014. http://www.oecd.org/about/publishing/betterpoliciesseries.htm#japan. Accessed May 15, 2016.

- 26.Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology. School Basic Survey 2015. http://www.e-stat.go.jp/SG1/estat/List.do?bid=000001015843&cycode=0. Accessed May 19, 2016.

- 27.Gender Equality Cabinet Office “White Paper on Gender Equality”, 2015.

- 28.The Japan Association of National Universities (2015). The 12th Report for the Implementation of Gender Equality in National Universities, Tokyo. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Glymour MM, Avendano M, Kawachi I (2014) Chapter 2. Soeioeconomic Status and Health. In: Berkman LF, Kawachi I, Glymour MM. Social Epidemiology 2nd edition, 17–62, Oxford University Press, New York. [Google Scholar]

- 30.The Union of University Part-time Lecturers in Tokyo Area and University Part-time Lecturers Union Kansai Part-time University Teachers: The Voice and the Realities Conditions of Part-time University Lecturers Survey Result (2001, 2007, 2007).

- 31.World Health Organization, Solar O, and Irwin A (2010). Chapter 5. CSDH conceptual framework. In: A conceptual framework for action on the social determinants of health. Social Determinants of Health Discussion Paper 2 (Policy and Practice), 20–49, World Health Organization, Geneva.