Abstract

Objective

Wheat gluten and related proteins can trigger an autoimmune enteropathy, known as coeliac disease, in people with genetic susceptibility. However, some individuals experience a range of symptoms in response to wheat ingestion, without the characteristic serological or histological evidence of coeliac disease. The aetiology and mechanism of these symptoms are unknown, and no biomarkers have been identified. We aimed to determine if sensitivity to wheat in the absence of coeliac disease is associated with systemic immune activation that may be linked to an enteropathy.

Design

Study participants included individuals who reported symptoms in response to wheat intake and in whom coeliac disease and wheat allergy were ruled out, patients with coeliac disease and healthy controls. Sera were analysed for markers of intestinal cell damage and systemic immune response to microbial components.

Results

Individuals with wheat sensitivity had significantly increased serum levels of soluble CD14 and lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-binding protein, as well as antibody reactivity to bacterial LPS and flagellin. Circulating levels of fatty acid-binding protein 2 (FABP2), a marker of intestinal epithelial cell damage, were significantly elevated in the affected individuals and correlated with the immune responses to microbial products. There was a significant change towards normalisation of the levels of FABP2 and immune activation markers in a subgroup of individuals with wheat sensitivity who observed a diet excluding wheat and related cereals.

Conclusions

These findings reveal a state of systemic immune activation in conjunction with a compromised intestinal epithelium affecting a subset of individuals who experience sensitivity to wheat in the absence of coeliac disease.

Keywords: GUT INFLAMMATION, INTESTINAL BARRIER FUNCTION, INTESTINAL EPITHELIUM, CELIAC DISEASE

Significance of this study.

What is already known on this subject?

Some individuals experience a range of symptoms in response to the ingestion of wheat and related cereals, yet lack the characteristic serological or histological markers of coeliac disease.

Accurate figures for the population prevalence of this sensitivity are not available, although estimates that put the number at similar to or greater than for coeliac disease are often cited.

Despite the increasing interest from the medical community and the general public, the aetiology and mechanism of the associated symptoms are largely unknown and no biomarkers have been identified.

What are the new findings?

Reported sensitivity to wheat in the absence of coeliac disease is associated with significantly increased levels of soluble CD14 and lipopolysaccharide-binding protein, as well as antibody reactivity to microbial antigens, indicating systemic immune activation.

Affected individuals have significantly elevated levels of fatty acid-binding protein 2 that correlates with the markers of systemic immune activation, suggesting compromised intestinal epithelial barrier integrity.

How might it impact on clinical practice in the foreseeable future?

The results demonstrate the presence of objective markers of systemic immune activation and gut epithelial cell damage in individuals who report sensitivity to wheat in the absence of coeliac disease.

The data offer a platform for additional research directed at assessing the use of the examined markers for identifying affected individuals and/or monitoring the response to treatment, investigating the underlying mechanism and molecular triggers responsible for the breach of the epithelial barrier, and evaluating novel treatment strategies in affected individuals.

Introduction

Coeliac disease is an autoimmune disorder with genetic, environmental and immunological components. It is characterised by an immune response to ingested wheat gluten and related proteins of rye and barley that leads to inflammation, villous atrophy and crypt hyperplasia in the small intestine. Among the most common manifestations of coeliac disease are abdominal pain, diarrhoea, weight loss, bone disease and anaemia.1 The disease is strongly associated with genes for the specific class II human leucocyte antigens (HLA) DQ2 and DQ8 that are involved in presenting specific immunogenic peptides of gluten proteins to CD4+ T cells in the small intestine.2 Transglutaminase 2 (TG2) appears to be an important player in the disease, both as a deamidating enzyme that can enhance the immunostimulatory effect of gluten and as the target autoantigen in the ensuing immune response.3 The major B-cell responses in patients with coeliac disease target native and deamidated gluten sequences, as well as the TG2 autoantigen. Among these, the IgA anti-TG2 antibody is currently considered the most sensitive and specific serological marker, whereas antibodies to native gluten proteins have low specificity for coeliac disease and have been found to be elevated in a number of other conditions as well.4

Some individuals experience a range of symptoms in response to ingestion of wheat and related cereals, yet lack the characteristic serological, histological or genetic markers of coeliac disease.5–8 The terms non-coeliac gluten sensitivity and non-coeliac wheat sensitivity (NCWS) are generally used to refer to this condition, which is currently understood as the collection of non-specific symptoms in response to ingestion of gluten-containing cereals, and the resolution of such symptoms on removal of those foods from diet in individuals in whom coeliac disease and IgE-mediated wheat allergy have been ruled out.9 The condition is associated with GI symptoms, most commonly including bloating, abdominal pain and diarrhoea, as well as certain extraintestinal symptoms, among which fatigue, headache, anxiety and cognitive difficulties feature prominently.6 Accurate figures for the prevalence of NCWS are not available, although estimates that put the number at similar to or greater than for coeliac disease (1%) are often cited.10 11 Despite the commonly used terminology for the condition, the identity of the component(s) of wheat and/or related cereals responsible for triggering the associated symptoms remains uncertain. While recent controlled trials have indicated a prominent role for gluten,7 12 non-gluten proteins and fermentable short-chain carbohydrates have also been suggested by some studies to drive aberrant immune responses or to be associated with symptoms.13 14

The potential mechanisms behind the onset of symptoms in NCWS remain unknown, and no biomarkers have been identified.10 However, a small number of studies point to increased antibody reactivity to gluten proteins,5 15 16 moderately raised intraepithelial lymphocyte numbers,5 6 17 increased intraepithelial and lamina propria eosinophil infiltration5 and enhanced expression of intestinal tight junction protein claudin 4,16 Toll-like receptor 2 (TLR2)16 or interferon gamma (IFNγ),17 suggesting intercellular junction and immune abnormalities in subsets of affected individuals. Human intestinal epithelial surfaces are colonised by large communities of microorganisms and are in constant contact with an abundance of highly immunogenic microbial products. Compromised intestinal epithelial integrity has been linked to extensive systemic innate and adaptive immune responses that are a consequence of microbial translocation from the lumen into circulation.18 Systemic immune activation in response to microbial translocation is a noted component of HIV infection and IBD.19 In the current study, we investigated (1) whether systemic immune activation in response to translocated microbial products may be a feature of NCWS, (2) whether such systemic immune activation is linked to a compromised intestinal epithelium and (3) whether the systemic immune activation or damage to the epithelium is responsive to the elimination of wheat and related cereals from diet.

Methods

Patients and controls

The study included 80 individuals with NCWS who met the criteria recently proposed by an expert group20 and who were identified using a previously described structured symptom questionnaire21 22 (a modified version of the Gastrointestinal Symptom Rating Scale designed to rate symptoms commonly associated with NCWS). All NCWS subjects reported experiencing intestinal and/or extraintestinal symptoms after ingestion of gluten-containing foods, including wheat, rye or barley. The reported symptoms in all subjects improved or disappeared when those foods were withdrawn for a period of 6 months, and recurred when they were re-introduced for a period of up to 1 month. Individuals were excluded if they were already on a restrictive diet in the past 6 months, if they were positive for the coeliac disease-specific IgA anti-endomysial and/or anti-TG2 autoantibody or for intestinal histological findings characteristic of coeliac disease, or if they were positive for wheat allergy-specific IgE serology or skin prick test. A total of six intestinal biopsies, including two from the duodenal bulb and four from the distal duodenum, were taken from each individual. Serum samples from all 80 NCWS subjects while on a diet that contained wheat, rye and/or barley were available. In addition to the above specimens, serum samples were available from 20 of the above NCWS individuals both before and after 6 months of a self-monitored diet free of wheat, rye and barley. These individuals were asked to complete the previously described questionnaire22 before initiating the diet and immediately following its completion. For this study, specific intestinal symptoms (bloating, abdominal pain, diarrhoea, epigastric pain and nausea) and extraintestinal symptoms (fatigue, headache, anxiety, memory and cognitive disturbances, and numbness in arms or legs), selected on the basis of being the most commonly reported symptoms by patients in this population as previously found,6 were considered for analysis. Symptoms were scored from 0 to 3 as follows: 0=absent, 1=occasionally present, 2=frequently present and 3=always present. A total score, based on the sum of individual symptom scores, was calculated for each individual at the two time points (before and after the diet). The study also included 40 serum samples from patients with biopsy-proven active coeliac disease and 40 serum samples from healthy subjects (both groups on normal non-restrictive diet), recruited as part of the same protocol that included the NCWS individuals. All cases of coeliac disease were biopsy proven and diagnosed according to established criteria.23 Screening questionnaires were used to evaluate the general health of unaffected controls. Individuals who had a history of liver disease, liver function blood test results (aspartate transaminase, alanine transaminase, alkaline phosphatase, total protein, albumin, globulin and bilirubin) outside the normal range or a recent infection were excluded from all cohorts in the study.

All samples were collected with written informed consent under institutional review board-approved protocols at St. Orsola-Malpighi Hospital, Bologna, Italy. Serum specimens were kept at −80°C to maintain stability. This study was approved by the institutional review board of Columbia University Medical Center.

Assays

Established serological markers of coeliac disease, including IgA antibody to TG2 and IgG and IgA antibodies to deamidated gliadin, were measured as previously described.24 25

Serum IgG, IgA and IgM antibodies to native gliadin were measured separately by ELISA as previously described,24 26 with the following modification: the secondary antibodies were horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated anti-human IgG (GE Healthcare), IgA (MP Biomedicals) or IgM (MP Biomedicals). Serum IgG, IgA and IgM antibodies to bacterial flagellin were measured separately using a similar protocol for detecting antibodies to gliadin, with the following modification: plates were coated with a 2 μg/mL solution of highly purified flagellin from Salmonella typhimurium (InvivoGen).

Levels of serum IgG, IgA and IgM endotoxin-core antibodies (EndoCAb) (Hycult Biotech), lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-binding protein (LBP) (Hycult Biotech), soluble CD14 (sCD14) (R&D Systems) and fatty acid-binding protein 2 (FABP2) (R&D Systems) were determined by ELISA, according to the manufacturers' protocols.

Data analysis

Group differences were analysed by the Kruskal-Wallis one-way analysis of variance, with post hoc testing and correction for multiple comparisons. Correlation analysis was performed using Spearman's r. A multivariate principal component analysis (PCA) was carried out on the entire dataset to reduce data dimensionality and to assess clustering. The effect of the restrictive diet was assessed by the Wilcoxon matched-pairs test. All p values were two sided, and differences were considered statistically significant at p<0.05. Statistical analyses were performed with Prism 6 (GraphPad) and Minitab 17 (Minitab) software.

Results

Patients and controls

The demographic and clinical characteristics of the study cohorts are included in table 1. Twenty-one (26%) NCWS individuals expressed HLA DQ2 and/or DQ8, a rate not substantially different than in the general population. Small intestine duodenal biopsy showed a normal mucosa (Marsh 0) in 48 (60%) and mild abnormalities, represented by an increased intraepithelial lymphocyte number (Marsh 1) in 32 (40%). In contrast, all patients with coeliac disease in this study expressed HLA DQ2 and/or DQ8 and presented with Marsh 3 grade intestinal histological findings.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of study cohorts

| Subject group | Number of subjects | Mean age, years (SD) | Female sex, n (%) | Coeliac disease-associated HLA DQ2 and/or DQ8, n (%) | Intestinal biopsy histological grade: Marsh 0; Marsh 1; Marsh 3, n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NCWS | |||||

| Non-restrictive diet | 80 | 34.6 (10.3) | 62 (78) | 21 (26) | 48 (60); 32 (40); 0 |

| Before and after restrictive diet* | 20 | 34.0 (10.7) | 19 (95) | 7 (35) | 9 (45); 11 (55); 0 |

| Active coeliac disease | 40 | 34.5 (13.7) | 30 (75) | 40 (100) | 0; 0; 40 (100) |

| Healthy | 40 | 35.0 (12.8) | 30 (75) | – | – |

*Intestinal biopsy taken before dietary restriction.

HLA, human leucocyte antigen; NCWS, non-coeliac wheat sensitivity.

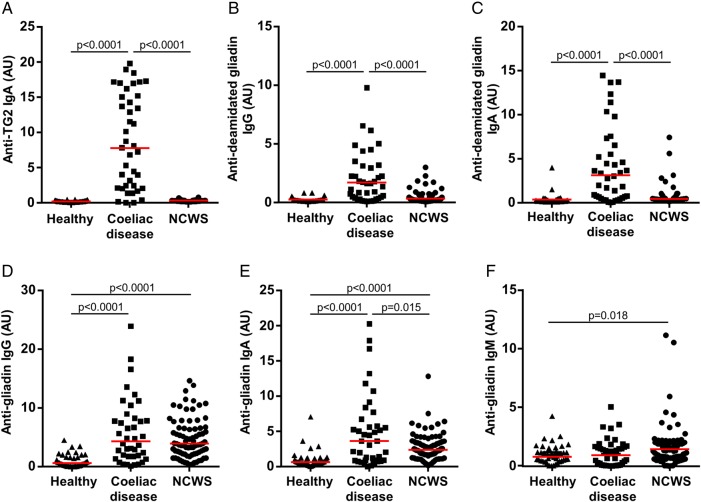

Markers of coeliac disease and immune reactivity to gluten

The active coeliac disease cohort exhibited significantly elevated IgA antibody reactivity to TG2, as well as IgG and IgA antibody reactivity to deamidated gliadin, when compared with healthy controls (p<0.0001 for each comparison) (figure 1A–C). Patients with coeliac disease also displayed increased IgG and IgA (p<0.0001 for each), but not IgM, antibody reactivity to native gliadin when compared with healthy controls (figure 1D–F). In the NCWS cohort (while being on a diet that did not restrict the intake of wheat and related cereals), IgG, IgA and IgM antibodies to native gliadin were all significantly higher than in the healthy control group (p<0.0001, p<0.0001 and p=0.018, respectively) (figure 1D–F). However, IgA reactivity to native gliadin in this NCWS cohort was lower than in the coeliac disease group (p=0.015). There was no association between antibody reactivity to native gliadin and the presence of HLA DQ2 and/or DQ8 genotypes in the NCWS group.

Figure 1.

Markers of coeliac disease and immune reactivity to wheat gluten. Serum levels of (A) IgA antibody to transglutaminase 2 (TG2), (B) IgG antibody to deamidated gliadin, (C) IgA antibody to deamidated gliadin, (D) IgG antibody to native gliadin, (E) IgA antibody to native gliadin and (F) IgM antibody to native gliadin in cohorts of healthy controls, patients with coeliac disease and individuals identified as having non-coeliac wheat sensitivity (NCWS). Horizontal red lines indicate the median for each cohort.

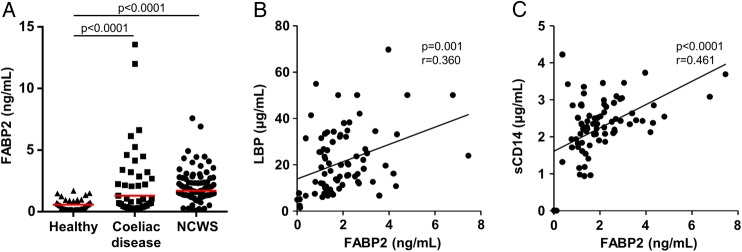

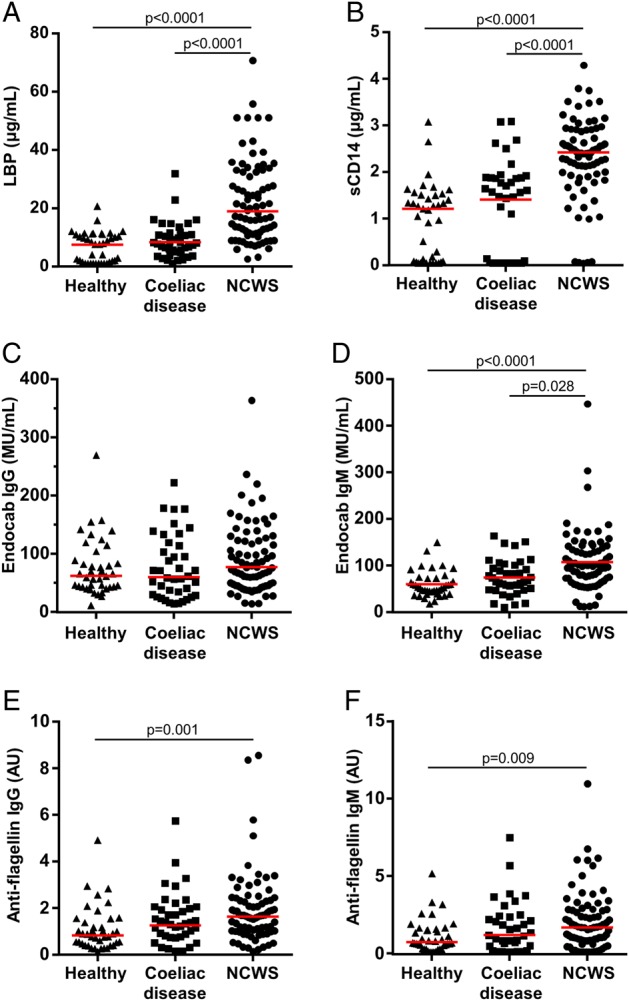

Systemic innate immune activation

Serum levels of both LBP and sCD14 were significantly elevated in individuals with NCWS in comparison with patients with coeliac disease and healthy individuals (p<0.0001 for each comparison) (figure 2A, B). There was a highly significant correlation between serum LBP and sCD14 (r=0.657, p<0.0001) (see online supplementary figure S1). Neither LBP nor sCD14 was found to be significantly elevated in patients with coeliac disease when compared with healthy controls.

Figure 2.

Markers of systemic immune response to microbial components. Serum levels of (A) lipopolysaccharide-binding protein (LBP), (B) soluble CD14 (sCD14), (C) endotoxin-core antibodies (EndoCAb) IgG, (D) EndoCAb IgM, (E) IgG antibody to flagellin and (F) IgM antibody to flagellin in cohorts of healthy controls, patients with coeliac disease and individuals with non-coeliac wheat sensitivity (NCWS). Horizontal red lines indicate the median for each cohort.

gutjnl-2016-311964supp_figures.pdf (344.4KB, pdf)

B-cell response to microbial antigens

When compared with the healthy control and coeliac disease cohorts, the NCWS group had significantly higher levels of EndoCAb IgM (p<0.0001 and p=0.028, respectively) (figure 2D), but not IgG or IgA (see figure 2C and online supplementary figure S2A). In contrast to the NCWS cohort, the coeliac disease group had higher levels of EndoCAb IgA when compared with the NCWS and healthy control groups (p=0.021 and p=0.032, respectively) (see online supplementary figure S2A), but not IgG or IgM (figure 2C, D).

Furthermore, the levels of IgG and IgM antibodies to flagellin were significantly elevated in the NCWS cohort when compared with the healthy control group (p=0.001 and p=0.009, respectively) (figure 2E, F). These antibodies were not significantly elevated in the coeliac disease cohort, although there was a trend towards higher IgA reactivity to flagellin when compared with healthy controls (p=0.059) (see online supplementary figure S2B). The increased IgM antibody response to flagellin correlated with the elevated EndoCAb IgM in the NCWS cohort (r=0.386, p<0.0001) (see online supplementary figure S3).

Systemic immune activation is associated with increased intestinal epithelial cell damage

In comparison with the healthy control group, serum concentrations of FABP2, a marker of intestinal epithelial cell damage, were significantly elevated in the NCWS cohort, as well as in the coeliac disease group (p<0.0001 for each) (figure 3A). In addition, the FABP2 concentrations in the NCWS cohort correlated with levels of LBP (r=0.360, p=0.001) and sCD14 (r=0.461, p<0.0001) (figure 3B, C). The FABP2 concentrations in the NCWS group also correlated with EndoCAb IgM (r=0.305, p=0.003) and anti-flagellin IgM antibody reactivity (r=0.239, p=0.033) in the NCWS cohort (see online supplementary figure S4A, B). In the coeliac disease cohort, FABP2 concentrations correlated with the levels of IgA antibody to TG2 (r=0.559, p<0.0001) (see online supplementary figure S5).

Figure 3.

Intestinal epithelial cell damage and correlation with systemic immune activation. (A) Serum levels of fatty acid-binding protein 2 (FABP2) in cohorts of healthy controls, patients with coeliac disease and individuals identified as having non-coeliac wheat sensitivity (NCWS). (B and C) Correlation of serum levels of FABP2 with lipopolysaccharide-binding protein (LBP) (B) and soluble CD14 (sCD14) (C) in individuals with NCWS. Horizontal red lines indicate the median for each cohort.

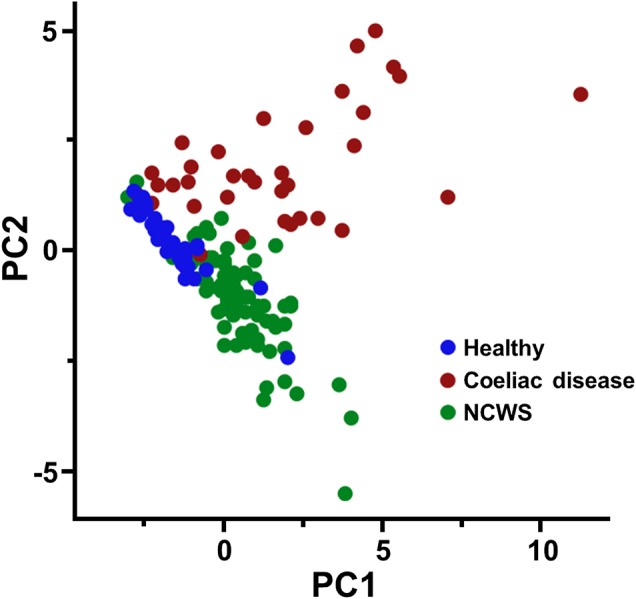

Multivariate analysis of dataset

PCA was used to assess similarities and differences between the subjects in the three cohorts based on the generated data and to determine whether they can be grouped. Most of the variability in the data could be explained by the first two components (54%). The score plot of the first and second components for the entire dataset demonstrated the clustering of the healthy control, coeliac disease and NCWS subjects into three discernible groups, with some outliers (figure 4).

Figure 4.

Principal component analysis (PCA) score plot for the complete dataset of serological markers (anti-transglutaminase 2 (anti-TG2) IgA; anti-deamidated gliadin IgG and IgA; anti-gliadin IgG, IgA and IgM; lipopolysaccharide-binding protein (LBP); soluble CD14 (sCD14); endotoxin-core antibodies (EndoCAb) IgG, IgA and IgM; anti-flagellin IgG, IgA and IgM; and fatty acid-binding protein 2 (FABP2)) measured in healthy controls, patients with coeliac disease and individuals with non-coeliac wheat sensitivity (NCWS). Subjects are plotted in two dimensions using the first and second principal components (PC1 and PC2).

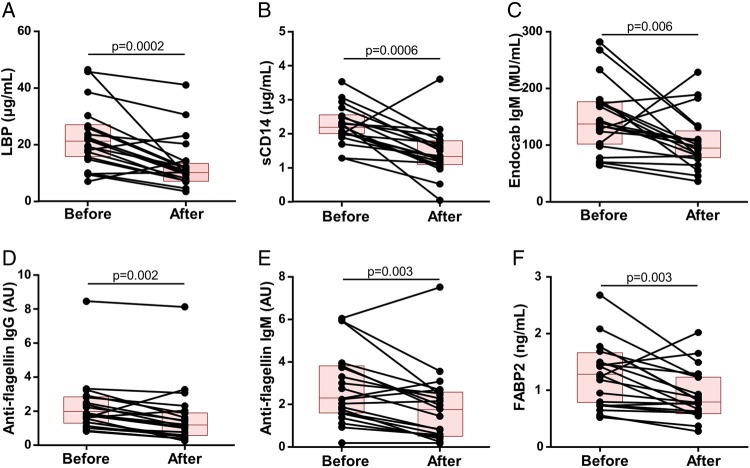

Systemic immune activation and intestinal epithelial cell damage respond to dietary restriction

Levels of the above markers of immune activation and gut epithelial cell damage were also measured in 20 of the above NCWS subjects before and 6 months after initiation of a diet free of wheat, rye and barley. All individuals reported symptom improvement at the end of 6 months, which was reflected in a significant reduction in both the intestinal and extraintestinal composite symptom scores (p<0.0001 for each) (figure 5A, B), accompanied by a decline in IgG, IgA and IgM anti-gliadin antibodies (p<0.0001, p=0.002 and p=0.004, respectively) (figure 5C–E). In conjunction with this, we found a statistically significant reduction in the serum levels of LBP (p=0.0002), sCD14 (p=0.0006), EndoCAb IgM (p=0.006), anti-flagellin IgG and IgM antibodies (p=0.002 and p=0.003, respectively) and FABP2 (p=0.003) after the completion of the diet (figure 6A–F). The magnitude of change in the measured biological markers did not correlate significantly with that for the symptom scores.

Figure 5.

Symptoms and anti-gliadin antibody reactivity in response to the restrictive diet. (A and B) Composite scores for intestinal symptoms (bloating, abdominal pain, diarrhoea, epigastric pain and nausea) and extraintestinal symptoms (fatigue, headache, anxiety, memory and/or cognitive disturbances, and numbness in arms and/or legs) before and after 6 months of a diet free of wheat, rye and barley in a cohort of 20 patients with non-coeliac wheat sensitivity (NCWS). (C–E) Levels of IgG, IgA and IgM antibody to gliadin proteins before and 6 months after starting the diet in the NCWS cohort. Each individual is represented by a dot and the two points corresponding to the same individual are connected by a line. Each box indicates the 25th–75th percentiles of distribution, with the horizontal line inside the box representing the median.

Figure 6.

Markers of intestinal epithelial cell damage and systemic immune activation in response to the restrictive diet. (A–F) Levels of lipopolysaccharide-binding protein (LBP), soluble CD14 (sCD14), endotoxin-core antibodies (EndoCAb) IgM, anti-flagellin IgG, anti-flagellin IgM and fatty acid-binding protein 2 (FABP2) before and after 6 months of a diet free of wheat, rye and barley in the cohort of 20 patients with non-coeliac wheat sensitivity (NCWS). Each individual is represented by a dot and the two points corresponding to the same individual are connected by a line. Each box indicates the 25th–75th percentiles of distribution, with the horizontal line inside the box representing the median.

Discussion

As expected, the cohort of individuals with sensitivity to wheat in the absence of coeliac disease did not exhibit significantly elevated antibody responses to TG2 or deamidated gliadin sequences. This indicates that in contrast to coeliac disease, the observed humoral immune response to gluten in NCWS is independent of TG2 enzymatic activity and HLA-DQ2/DQ8, and is likely to target certain epitopes that are distinct from those in coeliac disease. We hypothesised that the enhanced antibody response to native gliadin in NCWS individuals, particularly IgG and IgM isotypes, may be a consequence of ongoing intestinal epithelial barrier defects. If so, such defects might also give rise to an inadequate regulation of the interaction between the gut microbiota and systemic circulation, resulting in peripheral immune activation. To examine this, we measured the levels of LBP and sCD14 as indicators of the translocation of microbial products, particularly LPS, across the epithelial barrier. Translocated circulating LPS can result in the rapid secretion of LBP by GI and hepatic epithelial cells, as well as sCD14 by CD14+ monocytes/macrophages.19 sCD14 binds LPS in the presence of LBP to activate TLR4.27 We found significantly elevated serum levels of both LBP and sCD14 in individuals with NCWS in comparison with patients with coeliac disease and healthy controls. The high degree of correlation between serum LBP and sCD14 suggested that these molecules are concurrently expressed in response to the stimulus in NCWS individuals.

We also quantified serum levels of antibody to LPS core oligosaccharide, or EndoCAb, which is known to modulate in response to bacterial endotoxin in circulation.28 As they are involved in the neutralisation of circulating endotoxin, EndoCAb immunoglobulins are typically depleted in response to an acute LPS exposure, but eventually rise due to the B-cell anamnestic response.19 Individuals in the NCWS cohort exhibited increased levels of EndoCAb IgM. To demonstrate that the systemic immune response in individuals identified as having NCWS would not be limited to only LPS if driven by translocated microbial products, we also measured serum levels of antibody to flagellin, the principal substituent protein of the flagellum in Gram-positive and negative bacteria. We found that levels of IgG and IgM antibodies to flagellin were significantly elevated in the NCWS cohort. Considering that no individuals in this study had evidence of infection, these observations are suggestive of a translocation of microbial products from the GI tract that contributes to the observed innate and adaptive immune activation in the NCWS cohort.

Circulating bacterial components, such as LPS and flagellin, bind to their respective TLRs on various cells, including macrophages and dendritic cells, which results in signalling through the myeloid differentiation factor 88 (MyD88) adaptor protein.27 Ultimately, MyD88 signalling leads to the activation of transcription factor nuclear factor-κB and increased expression of various proinflammatory cytokines that can exert deleterious systemic effects.19 29 A systemic innate immune activation model would be consistent with the generally rapid onset of reported symptoms in NCWS.6 In addition, circulating microbial products can bind to TLRs on other cells to trigger a more localised inflammatory response. For example, LPS binds directly to TLR4 on the luminal surface of brain blood vessels, resulting in local cytokine secretion in the brain that has been shown to activate the microglia to displace inhibitory synapses.30 In HIV infection, where the presence of microbial translocation is linked to intestinal epithelial damage, increased systemic immune activation in response to bacterial antigens is associated with cognitive deficits.31 Such a pathway might contribute to some of the neurocognitive symptoms experienced by NCWS individuals.

Subsequently, we considered whether the observed systemic immune activation in response to microbial products in individuals with NCWS may be linked to increased intestinal enterocyte damage and turnover rate. FABP2 is a cytosolic protein specific to intestinal epithelial cells that is rapidly released into systemic circulation after cellular damage.32 Alterations in circulating FABP2 concentration, reflecting epithelial cell loss and changes in enterocyte turnover rate, are useful for identifying acute intestinal injury.32–35 Elevated circulating FABP2 has been shown to be associated with increasing degrees of villous atrophy in coeliac disease,36 and with microbial translocation in HIV37 that is in turn linked to damaged intestinal epithelial barrier integrity.18 Similar to the patients with coeliac disease, the NCWS individuals in this study were found to have raised circulating FABP2 levels, indicating increased intestinal epithelial cell damage. FABP2 concentrations in the NCWS cohort correlated strongly with levels of LBP and sCD14, suggesting a link between the intestinal epithelial cell damage and the acute systemic immune activation in response to translocated microbial products. The FABP2 concentrations in the NCWS group also correlated with IgM antibody reactivity towards microbial antigens, though less strongly in comparison with LBP and sCD14 responses, as might be expected for a systemic antibody response. In the coeliac disease cohort, FABP2 concentrations correlated with the increased IgA antibody to TG2, confirming the existence of a close relationship between the mucosal autoimmune response and the intestinal damage in this disease.

In contrast to coeliac disease, however, investigations of small intestine biopsies in NCWS subjects in this and other studies have not found villous atrophy or mucosal architectural abnormalities,5 6 21 38 even if significant inflammatory changes are seen.5 One possible explanation for this could be that the epithelial damage associated with NCWS is in regions other than the duodenum from where biopsies are generally taken in such individuals. This would be plausible because FABP2 is expressed primarily by the epithelial cells of the jejunum,33 39 which may point to this region of the small intestine as a potential primary site of mucosal damage in NCWS. Different sections of the GI tract have unique cellular, structural and immunological features that make them vulnerable to specific insults.40 Another possibility is that the epithelial changes associated with NCWS might be more subtle in comparison with coeliac disease, without overt remodelling of the mucosa. For example, tumour necrosis factor (TNFα)-mediated enhancement of enterocyte loss has been shown to cause mucosal barrier dysfunction and physical gaps in the epithelium that require confocal and scanning electron microscopy for visualisation.41

On the other hand, despite the established extensive villous damage associated with coeliac disease, neither LBP nor sCD14 levels were found to be significantly elevated in the coeliac disease group, thus standing in stark contrast to the NCWS cohort. In addition, among the immunoglobulin responses to microbial antigens, only IgA antibodies appeared to be increased in coeliac disease. These data suggest that there is an effective mechanism for the neutralisation of microbial products that may cross into the lamina propria in most cases of coeliac disease, possibly in part via the localised IgA response and mucosal phagocytic cells. These mechanisms are known to be essential for the immune surveillance of luminal antigens and the elimination of microbial products that cross the epithelial barrier, thereby reducing the likelihood of their translocation into the submucosa and access to blood vessels.19 Such mucosal immune responses may be lacking or inadequate in individuals with NCWS. Instead, what we observed were enhanced IgM responses to gliadin, LPS and flagellin in the NCWS cohort, which clearly contrasted with the coeliac disease group. In humans, IgM memory B cells are present in the peripheral blood and contribute to the expression of IgM antibodies to a diverse variety of antigens, offering a first line of defence against potential pathogens.42 Exposure to unmethylated CpG sequences, which are abundant in the bacterial and viral genomes, can result in TLR9-dependent proliferation and differentiation of these B cells, independent of direct interaction with their respective antigens or T-cell involvement.43 Acute microbial translocation from the gut, as the data from our study suggest, would be expected to enhance the secretion of IgM antibodies in the periphery via this pathway. These IgM B cells would be additionally stimulated on encounter with specific antigens, such as the translocated microbial components or gliadin sequences, and may contribute to the observed IgM antibody responses.43 44 Recognition and agglutination of antigens by IgM and IgG antibodies can result in the activation of the classical complement pathway and Fc receptor-mediated endocytosis by macrophages,45 further contributing to the ongoing systemic immune response.

The hallmark of NCWS is the onset of intestinal and/or extraintestinal symptoms on ingestion of gluten-containing foods, that is, wheat, rye and barley, and the alleviation of symptoms on their withdrawal from diet. To determine whether the patient-reported symptom resolution on the elimination of these foods would be associated with the amelioration of intestinal epithelial cell damage and a reduction in microbial translocation and systemic immune activation, we examined the above markers in a subset of NCWS subjects before and after a diet that excluded wheat and related cereals. The results indicated a significant decline in the markers of immune activation and gut epithelial cell damage, in conjunction with the improvement of symptoms. However, the magnitude of change in the measured biological markers did not correlate significantly with that for the symptom scores. This appears to be similar to observations in patients with coeliac disease, where symptoms are known to be a poor predictor of disease activity and associated biomarkers.46 47 A limitation of this portion of the study was the absence of a healthy control group to assess the potential impact of the dietary restriction in unaffected individuals.

In summary, the results of this study on individuals with sensitivity to wheat in the absence of coeliac disease demonstrate (1) significantly increased serum levels of sCD14 and LBP, as well as antibody reactivity to microbial antigens, indicating systemic immune activation; (2) an elevated expression of FABP2 that correlates with the systemic immune responses to bacterial products, suggesting compromised intestinal epithelial barrier integrity and increased microbial translocation; and (3) a significant change towards normalisation in the levels of the immune activation markers, as well as FABP2 expression, in response to the restrictive diet, which is associated with improvement in symptoms. Our data establish the presence of objective markers of systemic immune activation and epithelial cell damage in the affected individuals. The results of the multivariate data analysis suggest that a selected panel of these may have use for identifying patients with NCWS or patient subsets in the future. It is important to emphasise that this study does not address the potential mechanism or molecular trigger(s) responsible for driving the presumed loss of epithelial barrier integrity and microbial translocation. Further research is needed to investigate the mechanism responsible for the intestinal damage and breach of the epithelial barrier, assess the potential use of the identified immune markers for the diagnosis of affected individuals and/or monitoring the response to specific treatment strategies, and examine potential therapies to counter epithelial cell damage and systemic immune activation in affected individuals.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr Timothy C Wang (Columbia University) and Dr Donald D Kasarda (US Department of Agriculture) for the critical review and discussion of the manuscript. The authors are also grateful to Dr Benjamin Lebwohl and Dr Daniel E Freedberg (Columbia University) for insightful discussions and input during the course of the study.

Footnotes

Contributors: AA had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. AA: study concept and design. MU, MA, GC, RDG, AI, ECV, PHG, UV and AA: contribution to study design. MU, MA, GC, RDG, AI and UV: acquisition of data. MU, MA, GC, RDG, AI, ECV, PHG, UV and AA: analysis and interpretation of data. MU and AA: drafting of the manuscript. MU, MA, GC, RDG, PHG, ECV, UV and AA: critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content. MU and AA: statistical analysis. GC, RDG, ECV, PHG, UV and AA: administrative, technical or material support. AA: obtained funding. AA: study supervision.

Funding: This study was supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health, through grant number UL1 TR000040 (to AA) and The Stanley Medical Research Institute through grant number 08R-2061 (to AA). Additional support was provided by the Italian Ministry of University, Research and Education through grant number 2009MFSXNZ_002 (to RDG), the Italian Ministry of Public Health through Ricerca Finalizzata Regione Emilia Romagna-2009 (to RDG), and funds from the University of Bologna. The funding agencies had no role in the design and conduct of the study; in the collection, analysis and interpretation of the data; or in the preparation, review or approval of the manuscript.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: Institutional Review Board of Columbia University Medical Center.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Guandalini S, Assiri A. Celiac disease: a review. JAMA Pediatr 2014;168:272–8. 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2013.3858 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Louka AS, Sollid LM. HLA in coeliac disease: unravelling the complex genetics of a complex disorder. Tissue Antigens 2003;61:105–17. 10.1034/j.1399-0039.2003.00017.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sollid LM, Jabri B. Celiac disease and transglutaminase 2: a model for posttranslational modification of antigens and HLA association in the pathogenesis of autoimmune disorders. Curr Opin Immunol 2011;23:732–8. 10.1016/j.coi.2011.08.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rostom A, Murray JA, Kagnoff MF. American Gastroenterological Association (AGA) Institute Technical Review on the Diagnosis and Management of Celiac Disease. Gastroenterology 2006;131:1981–2002. 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.10.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carroccio A, Mansueto P, Iacono G, et al. . Non-celiac wheat sensitivity diagnosed by double-blind placebo-controlled challenge: exploring a new clinical entity. Am J Gastroenterol 2012;107:1898–906. 10.1038/ajg.2012.236 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Volta U, Bardella MT, Calabrò A, et al. . An Italian prospective multicenter survey on patients suspected of having non-celiac gluten sensitivity. BMC Med 2014;12:85 10.1186/1741-7015-12-85 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Biesiekierski JR, Newnham ED, Irving PM, et al. . Gluten causes gastrointestinal symptoms in subjects without celiac disease: a double-blind randomized placebo-controlled trial. Am J Gastroenterol 2011;106:508–14. 10.1038/ajg.2010.487 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Peters SL, Biesiekierski JR, Yelland GW, et al. . Randomised clinical trial: gluten may cause depression in subjects with non-coeliac gluten sensitivity—an exploratory clinical study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2014;39:1104–12. 10.1111/apt.12730 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ludvigsson JF, Leffler DA, Bai JC, et al. . The Oslo definitions for coeliac disease and related terms. Gut 2013;62:43–52. 10.1136/gutjnl-2011-301346 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fasano A, Sapone A, Zevallos V, et al. . Nonceliac gluten sensitivity. Gastroenterology 2015;148:1195–204. 10.1053/j.gastro.2014.12.049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Green PH, Lebwohl B, Greywoode R. Celiac disease. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2015;135:1099–106. 10.1016/j.jaci.2015.01.044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Di Sabatino A, Volta U, Salvatore C, et al. . Small amounts of gluten in subjects with suspected nonceliac gluten sensitivity: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, cross-over trial. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2015;13:1604–12. 10.1016/j.cgh.2015.01.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Junker Y, Zeissig S, Kim SJ, et al. . Wheat amylase trypsin inhibitors drive intestinal inflammation via activation of toll-like receptor 4. J Exp Med 2012;209:2395–408. 10.1084/jem.20102660 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Biesiekierski JR, Peters SL, Newnham ED, et al. . No effects of gluten in patients with self-reported non-celiac gluten sensitivity after dietary reduction of fermentable, poorly absorbed, short-chain carbohydrates. Gastroenterology 2013;145:320–8. 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.04.051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Volta U, Tovoli F, Cicola R, et al. . Serological tests in gluten sensitivity (nonceliac gluten intolerance). J Clin Gastroenterol 2012;46:680–5. 10.1097/MCG.0b013e3182372541 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sapone A, Lammers KM, Casolaro V, et al. . Divergence of gut permeability and mucosal immune gene expression in two gluten-associated conditions: celiac disease and gluten sensitivity. BMC Med 2011;9:23 10.1186/1741-7015-9-23 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brottveit M, Beitnes AC, Tollefsen S, et al. . Mucosal cytokine response after short-term gluten challenge in celiac disease and non-celiac gluten sensitivity. Am J Gastroenterol 2013;108:842–50. 10.1038/ajg.2013.91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Estes JD, Harris LD, Klatt NR, et al. . Damaged intestinal epithelial integrity linked to microbial translocation in pathogenic simian immunodeficiency virus infections. PLoS Pathog 2010;6:e1001052 10.1371/journal.ppat.1001052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brenchley JM, Douek DC. Microbial translocation across the GI tract. Annu Rev Immunol 2012;30:149–73. 10.1146/annurev-immunol-020711-075001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Catassi C, Elli L, Bonaz B, et al. . Diagnosis of non-celiac gluten sensitivity (NCGS): the Salerno experts’ criteria. Nutrients 2015;7:4966–77. 10.3390/nu7064966 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Caio G, Volta U, Tovoli F, et al. . Effect of gluten free diet on immune response to gliadin in patients with non-celiac gluten sensitivity. BMC Gastroenterol 2014;14:26 10.1186/1471-230X-14-26 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Volta U, Caio G, De Giorgio R, et al. . Non-celiac gluten sensitivity: a work-in-progress entity in the spectrum of wheat-related disorders. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol 2015;29:477–91. 10.1016/j.bpg.2015.04.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rubio-Tapia A, Hill ID, Kelly CP, et al. . ACG clinical guidelines: diagnosis and management of celiac disease. Am J Gastroenterol 2013;108:656–76. 10.1038/ajg.2013.79 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Moeller S, Canetta PA, Taylor AK, et al. . Lack of serologic evidence to link IgA nephropathy with celiac disease or immune reactivity to gluten. PLoS ONE 2014;9:e94677 10.1371/journal.pone.0094677 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lau NM, Green PH, Taylor AK, et al. . Markers of celiac disease and gluten sensitivity in children with autism. PLoS ONE 2013;8:e66155 10.1371/journal.pone.0066155 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Huebener S, Tanaka CK, Uhde M, et al. . Specific nongluten proteins of wheat are novel target antigens in celiac disease humoral response. J Proteome Res 2015;14:503–11. 10.1021/pr500809b [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Miller SI, Ernst RK, Bader MW. LPS, TLR4 and infectious disease diversity. Nat Rev Microbiol 2005;3:36–46. 10.1038/nrmicro1068 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Barclay GR. Endogenous endotoxin-core antibody (EndoCAb) as a marker of endotoxin exposure and a prognostic indicator: a review. Prog Clin Biol Res 1995;392:263–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Akira S, Takeda K. Toll-like receptor signalling. Nat Rev Immunol 2004;4:499–511. 10.1038/nri1391 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chen Z, Jalabi W, Shpargel KB, et al. . Lipopolysaccharide-induced microglial activation and neuroprotection against experimental brain injury is independent of hematogenous TLR4. J Neurosci 2012;32:11706–15. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0730-12.2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sandler NG, Douek DC. Microbial translocation in HIV infection: causes, consequences and treatment opportunities. Nat Rev Microbiol 2012;10:655–66. 10.1038/nrmicro2848 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pelsers MM, Hermens WT, Glatz JF. Fatty acid-binding proteins as plasma markers of tissue injury. Clin Chim Acta 2005;352:15–35. 10.1016/j.cccn.2004.09.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pelsers MM, Namiot Z, Kisielewski W, et al. . Intestinal-type and liver-type fatty acid-binding protein in the intestine. Tissue distribution and clinical utility. Clin Biochem 2003;36:529–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sandler NG, Koh C, Roque A, et al. . Host response to translocated microbial products predicts outcomes of patients with HBV or HCV infection. Gastroenterology 2011;141:1220–30. 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.06.063 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sacchettini JC, Hauft SM, Van Camp SL, et al. . Developmental and structural studies of an intracellular lipid binding protein expressed in the ileal epithelium. J Biol Chem 1990;265:19199–207. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Adriaanse MP, Tack GJ, Passos VL, et al. . Serum I-FABP as marker for enterocyte damage in coeliac disease and its relation to villous atrophy and circulating autoantibodies. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2013;37:482–90. 10.1111/apt.12194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hunt PW, Sinclair E, Rodriguez B, et al. . Gut epithelial barrier dysfunction and innate immune activation predict mortality in treated HIV infection. J Infect Dis 2014;210:1228–38. 10.1093/infdis/jiu238 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shahbazkhani B, Sadeghi A, Malekzadeh R, et al. . Non-celiac gluten sensitivity has narrowed the spectrum of irritable bowel syndrome: a double-blind randomized placebo-controlled trial. Nutrients 2015;7:4542–54. 10.3390/nu7064542 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Derikx JP, Vreugdenhil AC, Van den Neucker AM, et al. . A pilot study on the noninvasive evaluation of intestinal damage in celiac disease using I-FABP and L-FABP. J Clin Gastroenterol 2009;43:727–33. 10.1097/MCG.0b013e31819194b0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cossart P, Sansonetti PJ. Bacterial invasion: the paradigms of enteroinvasive pathogens. Science 2004;304:242–8. 10.1126/science.1090124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kiesslich R, Goetz M, Angus EM, et al. . Identification of epithelial gaps in human small and large intestine by confocal endomicroscopy. Gastroenterology 2007;133:1769–78. 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.09.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lanzavecchia A, Bernasconi N, Traggiai E, et al. . Understanding and making use of human memory B cells. Immunol Rev 2006;211:303–9. 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2006.00403.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Capolunghi F, Rosado MM, Sinibaldi M, et al. . Why do we need IgM memory B cells? Immunol Lett 2013;152:114–20. 10.1016/j.imlet.2013.04.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bailey M, Haverson K, Miller B, et al. . Effects of infection with transmissible gastroenteritis virus on concomitant immune responses to dietary and injected antigens. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol 2004;11:337–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ehrenstein MR, Notley CA. The importance of natural IgM: scavenger, protector and regulator. Nat Rev Immunol 2010;10:778–86. 10.1038/nri2849 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Katz KD, Rashtak S, Lahr BD, et al. . Screening for celiac disease in a North American population: sequential serology and gastrointestinal symptoms. Am J Gastroenterol 2011;106:1333–9. 10.1038/ajg.2011.21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Leffler DA, Dennis M, Hyett B, et al. . Etiologies and predictors of diagnosis in nonresponsive celiac disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2007;5:445–50. 10.1016/j.cgh.2006.12.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

gutjnl-2016-311964supp_figures.pdf (344.4KB, pdf)