Abstract

Aim

To evaluate the effects of resistance training on metabolic syndrome risk factors through comparison with a control group.

Design

Meta-analysis comparing resistance training interventions with control groups. Two independent reviewers selected the studies and assessed their quality and data. The pooled mean differences between resistance training and the control group were calculated using a fixed-effects model.

Data sources

The MEDLINE, PEDro, EMBASE, SPORTDiscus and The Cochrane Library databases were searched from their earliest records to 10 January 2015.

Eligibility criteria for selecting studies

Randomised controlled trials that compared the effect of resistance training on metabolic syndrome risk factors with a control group were included. All types of resistance training, irrespective of intensity, frequency or duration, were eligible.

Results

Only systolic blood pressure was significantly reduced, by 4.08 mm Hg (95% CI 1.33 to 6.82; p<0.01), following resistance training. The pooled effect showed a reduction of 0.04 mmol/L (95% CI −0.12, 0.21; p>0.05) for fasting plasma glucose, 0.00 (95% CI −0.05, 0.04; p>0.05) for high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol, 0.03 (95% CI −0.14, 0.20; p>0.05) for triglycerides, 1.39 mm Hg (95% CI −0.19, 2.98; p=0.08) for diastolic blood pressure and 1.09 cm (95% CI −0.12, 2.30; p=0.08) for waist circumference. Inconsistency (I2) for all meta-analysis was 0%.

Conclusions

Resistance training may help reduce systolic blood pressure levels, stroke mortality and mortality from heart disease in people with metabolic syndrome.

Trial registration number

CRD42015016538.

Keywords: Exercise training, Strength, Cardiovascular

Introduction

Individuals with metabolic syndrome1 2 have a greater risk of developing cardiovascular diseases and type 2 diabetes mellitus, and consequently have an increased risk of premature death.3

Resistance training is an effective, low-cost strategy to prevent and treat cardiovascular events.4 There is an inverse association between muscular fitness5 and strength and the incidence of metabolic syndrome. People who practise resistance training have a 34% lower chance of developing the syndrome.6

However, there are conflicting results in papers on the contribution of resistance training and metabolic syndrome disorders. In some trials, the incidence of metabolic syndrome was reduced,7–10 but in others, resistance training showed no effect on the components of metabolic syndrome.11–13 Meta-analysis allows the results of independent studies to be grouped.

To the best of the our knowledge, the only one previous meta-analysis14 that has examined the effects of resistance training on metabolic syndrome was published in 2010. The authors included only studies in the English language published up to 2007, with the primary outcomes of HbA1c and fat mass percentage. Studies involving four types of intervention were included: resistance training versus control, resistance plus aerobic training versus control, resistance versus aerobic training and resistance training plus diet versus only diet. The systematic review did not investigate the isolated effect of resistance training compared with a control group. The authors did not evaluate the methodological quality of the included studies.15

Therefore, the aim of this systematic review and meta-analysis was to evaluate the effects of resistance training on metabolic syndrome risk factors (blood pressure, fasting glucose, triglycerides, high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol and waist circumference) in comparison with a control group.

Materials and methods

This systematic review was registered in an international database of systematic reviews in health and social care (registration number CRD42015016538; http://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/). The preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analyses (PRISMA) guidelines were followed to improve the reporting of this systematic review and meta-analysis.

Literature search

The MEDLINE, PEDro, EMBASE, SPORTDiscus and The Cochrane Library databases were searched from their earliest records to 10 January 2015, to identify randomised controlled trials that use resistance training as an exercise treatment for metabolic syndrome. The search strategy used a combination of the following Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) terms: randomised controlled trial, metabolic syndrome x and resistance training. Keywords related to these terms were also used (see online supplementary table S1). The reference lists of the included studies were checked to find potential studies that could also be used in this review. There were no language or date of publication restrictions.

bjsports-2015-094715supp_tables.pdf (1.1MB, pdf)

Study selection

Study selection was performed by two independent researchers (IRL and SNL), with disagreements resolved by consensus. If necessary, a third researcher (JNJ) was consulted. Only randomised controlled trials that compared resistance training with a control group (no intervention) were included in this review. Studies that used diet intervention were included if this intervention was equal for all the groups in the study. Trials were eligible if they included participants with metabolic syndrome and assessed the components of the syndrome: elevated fasting plasma glucose, triglycerides, HDL-cholesterol, blood pressure and waist circumference. As the aim of the study was to evaluate the effect on all metabolic syndrome risk factors, studies that did not evaluate at least four of these outcomes were excluded. All types of resistance training, irrespective of intensity, frequency or duration, were eligible for inclusion.

Data extraction and risk of bias assessment

For risk of bias assessment, two different tools were used, the PEDro scale16 17 and the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE).18 19 The PEDro scale is a valid measure of the methodological quality of clinical trials and is based on the Delphi list developed by Verhagen et al.20 The GRADE approach evaluates the quality of evidence for outcomes (meta-analysis) reported in systematic reviews. In addition, it is a systematic and explicit approach that allows judgements to be made about strength of evidence and is an effective method for linking evidence quality and clinical recommendations.

Two reviewers (IRL and SNL) independently assessed the risk of bias of individual studies using the PEDro scale.16 17 If trials were already listed on the PEDro database (http://www.pedro.org.au/), these scores were adopted. A PEDro score of 7 or greater was considered of ‘high quality’, studies with a score of 5 or 6 were considered of ‘moderate quality’ and those with a score of 4 or less were deemed of ‘poor quality’.21–23 Any disagreements in the scoring of trials were resolved consensually. Methodological quality was not an inclusion criterion. Two reviewers (IRL and SNL) also independently extracted outcome data using a standardised data extraction form.

The GRADE approach was used by two independent reviewers (IRL and SNL) to evaluate the overall quality of evidence and the strength of the recommendation,18 19 as advocated by the Cochrane Back Review Group.24 The overall quality of evidence was initially regarded as ‘high’ but was downgraded by one level for each of the three factors encountered: risk of bias (>25% of participants from studies with low-quality methods—PEDro score <7 points), inconsistency of results (substantial I2 statistic) and imprecision (<400 participants in total for each outcome). Publication bias assessment with a funnel plot was not performed and indirectness was not considered for this review owing to the presence of a specific population, relevant outcome measures and direct comparisons.

The following factors were used to define the quality of evidence: high quality—further research is unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect; moderate quality—further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and might change the estimate; low quality—further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate; and very low quality—we are uncertain about the estimate.

Extracted data included final values of means, SDs and sample sizes of triglycerides, fasting glucose, HDL-cholesterol, blood pressure and waist circumference. When final values were not available, change scores were used. When there was insufficient information, the authors were contacted. As SD values are not always reported by researchers, where necessary, these data were imputed or calculated using methods recommended in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. As an example, in the study by Castaneda,25 SD was obtained from the SE of the mean multiplied by the square root of the sample size.

Blood pressure values were expressed in millimetre of mercury, waist circumference in centimetres and glucose, triglycerides and HDL-cholesterol in millimole per litre. Where appropriate, data were converted to these units of measurement.

Statistical analysis

Pooling was carried out using Comprehensive Meta-Analysis software, V.2.2.064 (BioStat, Englewood, New Jersey, USA). When trials were sufficiently homogeneous (ie, an I2 value <50%), pooled effects were calculated using a fixed-effects model, whereas random effects were used to estimate the pooled effects of heterogeneous trials (ie, an I2 of 50% or more). Mean difference (MD) with 95% CIs was calculated.

In addition, a stratified exploratory analysis was performed using the same procedures as the main analysis, comparing high (PEDro ≥7) versus low/moderate (PEDro ≤6) methodological quality, and short-term (<6 months) versus long-term (≥6 months) interventions, as used in a previous study.26

Results

Description of included studies

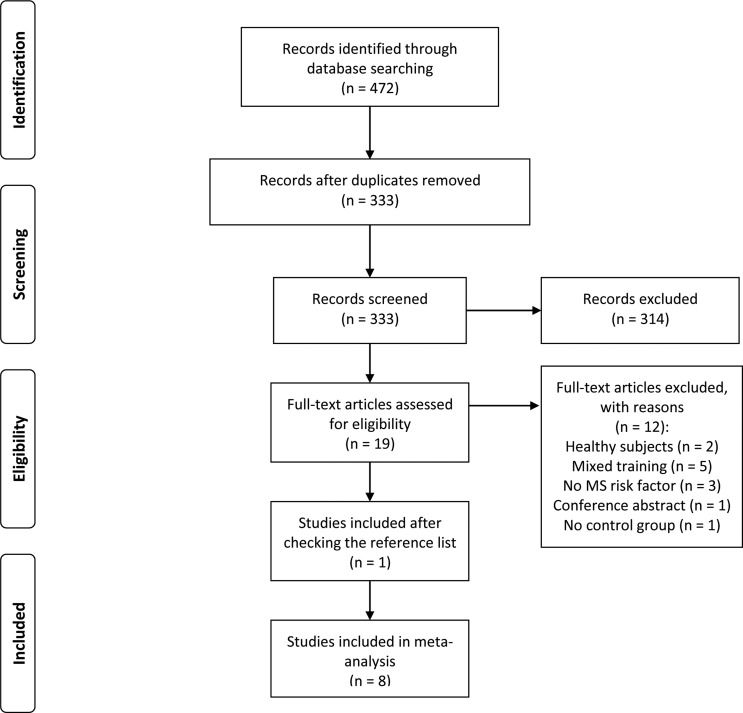

After the removal of duplicates, the search strategy identified 333 titles. Screening of titles and abstracts identified 19 potentially eligible articles, and 7 original trials were included.7 8 10 11 25 27 28 A further study29 was included after checking the reference lists of included trials. The reasons for excluding articles were: use of healthy subjects,30 31 intervention with mixed training, that is, resistance plus aerobic training,32–36 no evaluation of metabolic syndrome risk factors,37–39 conference abstract40 and no control group13 (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flow chart of studies included.

A total of 341 men and 178 women were included in the meta-analysis. Three studies included only men,10 11 28 and five included a mixed sample of men and women, with 64.5% (n=40),25 44.8% (n=13),27 36.2% (n=46),29 39.5% (n=8)8 and 62.2% (n=71)7 of women, respectively. The training period ranged from 12 weeks to 9 months, and all studies had an incremental workload in intensity or volume. Online supplementary table 2 shows the characteristics of the included trials.

Resistance training as a treatment of metabolic syndrome

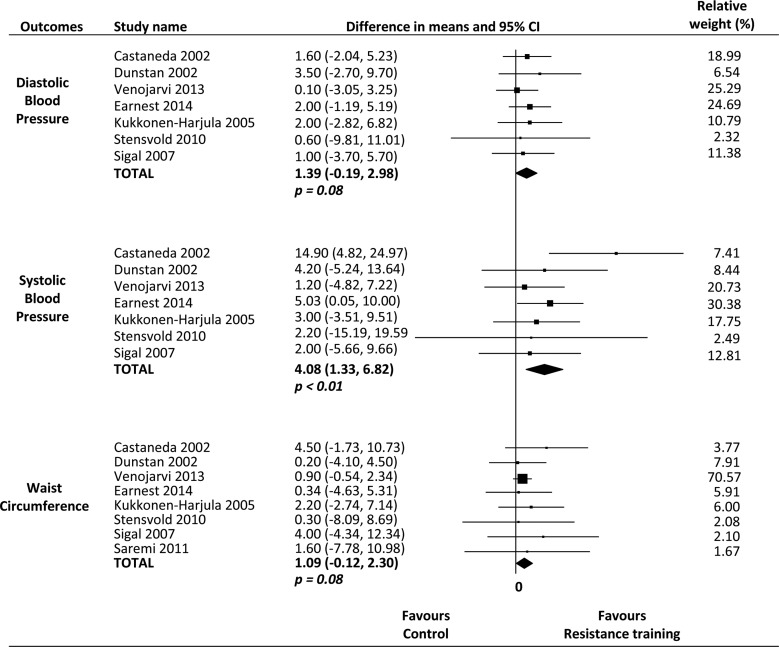

A fixed-effects model was used for all meta-analyses. The results of meta-analysis comparing the effects of resistance training with a control group show that resistance training is significantly superior to control groups in terms of reducing systolic blood pressure (seven studies, n=476, I2=0%, MD 4.08 mm Hg (95% CI 1.33 to 6.82)).

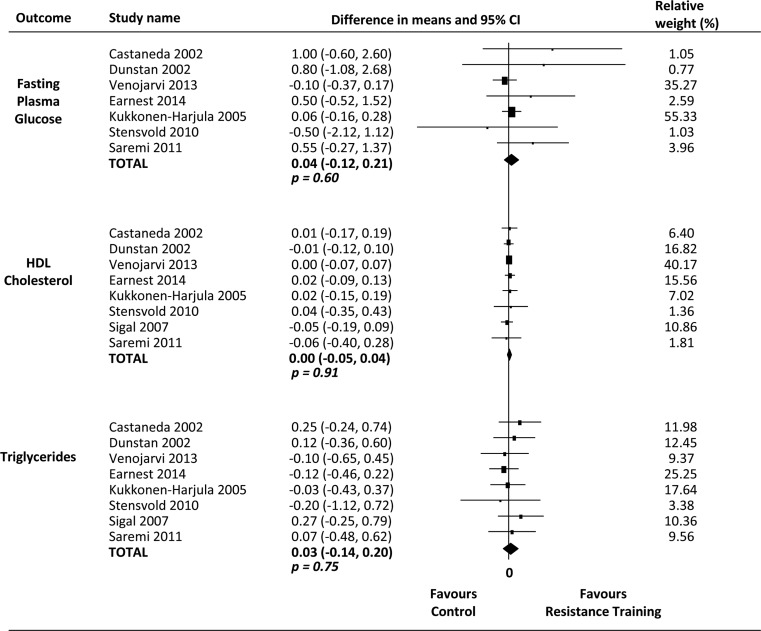

However, the results of pooling data show that resistance training is not superior to control interventions (no intervention) in improving fasting plasma glucose (seven studies, n=370, I2=0%, MD 0.04 mmol/L (95% CI −0.12 to 0.21)), HDL-cholesterol (eight studies, n=497, I2=0%, MD 0.00 mmol/L (95% CI −0.05 to 0.04)), triglycerides (eight studies, n=497, I2=0%, MD 0.03 mmol/L (95% CI −0.14 to 0.20)), diastolic blood pressure (seven studies, n=476, I2=0%, MD 1.39 mm Hg (95% CI −0.19, 2.98)) and waist circumference (eight studies, n=497, I2=0%, MD 1.09 cm (95% CI −0.12 to 2.30)) (figures 2 and 3).

Figure 2.

Effects of resistance training on clinical parameters of metabolic syndrome.

Figure 3.

Effects of resistance training on metabolic parameters of metabolic syndrome.

Methodological quality

One study29 was considered ‘high quality’, three studies8 25 28 were considered ‘moderate quality’ and four studies7 10 11 27 were considered ‘poor quality’. All included trials had random allocation between group comparisons and provided points and estimates of variability. Concealed allocation was performed in two studies.8 29 Owing to the nature of the interventions, blinding of participants and therapists was not possible. Assessor blinding was implemented in two of included studies.25 29 In addition, four studies had adequate follow-up,8 25 28 29 and two studies included an intention-to-treat analysis.25 29 Complete details are reported in online supplementary table 3.

Secondary exploratory analysis

Exploratory analysis was performed comparing short-term (<6 months) versus long-term (≥6 months) studies (see online supplementary appendix figure 1–appendix figure 6), and low/moderate methodological quality (PEDro ≤6) versus high methodological quality (PEDro ≥7) studies (see online supplementary appendix figure 7–appendix figure 11). Stratified analysis by methodological quality for fasting glucose results was not possible as the high-quality study29 did not report this outcome.

bjsports-2015-094715supp_figures.pdf (2.9MB, pdf)

Long-term trials are more effective than short-term trials in reducing systolic blood pressure (four studies, I2=0%, MD 3.85 mm Hg (95% CI 0.55 to 7.14); p=0.02). There was also a reduction in diastolic blood pressure, although this was not statistically significant (four studies, I2=0%, MD 1.97 mm Hg (95% CI −0.20 to 4.14); p=0.07). Other potential influences of these aspects were not detected as comparisons of subgroups revealed no differences in pooled estimates with overlapping CIs.

No inference could be made about the comparison between low/moderate-quality and high-quality studies because of the small number of high-quality studies.

GRADE assessment of main analyses

On the basis of the GRADE system (see online supplementary table 4), pooled data of HDL-cholesterol, triglycerides, systolic blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure and waist circumference were classified as moderate-quality evidence. All these variables were downgraded one level owing to the presence of risk of bias (more than 25% of participants from studies of low/moderate methodological quality, PEDro score <7 points). The evidence for fasting plasma glucose lost points owing to the risk of bias and imprecision (fewer than 400 participants in the meta-analysis) and was classified as low-quality evidence.

Discussion

This systematic review provides evidence of moderate quality that resistance training reduces systolic blood pressure in adults with metabolic syndrome. Although there seems to be a trend that resistance training slightly improves diastolic blood pressure and waist circumference, the meta-analysis may have been underpowered for detection of differences in these two risk factors. Resistance training had no effect on metabolic parameters, that is, fasting glucose, HDL-cholesterol and triglycerides.

Systolic blood pressure reduced by resistance training

There was a reduction in systolic blood pressure of 4.1 mm Hg, which extends findings in previous studies that reported reductions after resistance training intervention.14 41 42 Lewington et al43 found that even a reduction of up to 2 mm Hg can reduce stroke mortality by around 10% and mortality from heart disease by about 7%. Although these reductions seem proportionately small, it is related to changes in only one risk factor, systolic blood pressure.

Thus, the present study reinforces the importance of physical training as an important strategy in the treatment and prevention of this syndrome and shows that further randomised controlled trials are required to conclusively determine the effect of resistance training on the parameters of metabolic syndrome. Moreover, the methodological quality of future studies should be improved. Researchers should be concerned mainly to concealed allocation, blinding of assessors and the inclusion of an intention-to-treat analysis.

Comparison with other studies

Regarding metabolic outcomes, the results extend those of Cornelissen et al.42 The authors did not find any significant changes in fasting glucose, HDL-cholesterol and triglyceride values. When the studies were considered individually, only one found significant positive changes in HDL-C28 and one showed improvement in triglyceride and fasting plasma glucose values.10 Both studies used only male subjects. Whereas five of the studies included in this review comprised volunteers of both sexes, and metabolic changes caused by menopause may influence the behaviour of these risk factors,44 further research is needed with specific populations to better understand these effects.

One interesting point to consider in this study is the consistency found in the meta-analyses. Such consistency is probably due to the similarity of the effect sizes. A specific population of similar age, affected by the same condition (metabolic syndrome), and undergoing similar interventions may have contributed to this lack of heterogeneity. However, it is important to note that the absence of heterogeneity, as measured by I2, does not imply homogeneity.

Considering these results, we propose periodised and individualised resistance training as part of treatment to reduce systolic blood pressure in patients with metabolic syndrome.

Strengths and limitations

The strengths of this systematic review are its search protocol and the inclusion of only randomised controlled trials. In addition, trials published in any language were eligible for inclusion. Another strength of this review is that the training effect was explored through quantitatively pooled trials. Inconsistency (I2) was assessed to evaluate the consistency of the results. It is important to show that the variation in findings is compatible with chance alone. The I2 of the meta-analysis was 0% for all risk factors. Also, the overall quality of the evidence was assessed using the GRADE approach, which evaluates quality of evidence and is an effective method for linking evidence quality and clinical recommendations.

A limitation of this review is that publication bias was not assessed with a funnel plot, as tests for funnel plot asymmetry should be used only when there are at least 10 studies included in the meta-analysis.24 Another limitation, not of this study particularly, is the low number of participants composing this meta-analysis. It shows that, despite the advance of exercise science in recent years, there is a lack of randomised trials evaluating these conditions (metabolic syndrome and resistance training).

In summary, resistance training is an effective treatment for reducing systolic blood pressure levels by approximately 4 mm Hg in people with metabolic syndrome. This effect size is clinically meaningful because it would translate to a 10% reduction in stroke mortality and 7% reduction in deaths from heart disease if achieved at a population level.

What is already known?

Resistance training is an effective and low-cost method to prevent and treat cardiovascular diseases.

There is an inverse association between muscular strength and the incidence of metabolic syndrome.

What are the new findings?

Resistance training reduces systolic blood pressure by approximately 4.1 mm Hg.

At the society level, a reduction of up to 2 mm Hg can reduce stroke mortality by around 10% and mortality from heart disease by about 7%.

There was no statistical difference between resistance training and control in reducing diastolic blood pressure and waist circumference.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dr Fereshteh Pourkazemi and the corresponding authors of studies included in this review and meta-analysis for their help in data acquisition.

Footnotes

Contributors: All the authors contributed to the design, searching and screening of studies and data extraction. IRL, PHF, CMP and JNJ contributed to the analysis, discussion and preparation of manuscript.

Funding: This study was funded by the São Paulo Research Foundation (FAPESP), grant #2013/10857-6 and #2014/05419-2.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Alberti KG, Eckel RH, Grundy SM, et al. , International Diabetes Federation Task Force on Epidemiology and Prevention; Hational Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; American Heart Association; World Heart Federation; International Atherosclerosis Society; International Association for the Study of Obesity. Harmonizing the metabolic syndrome: a joint interim statement of the International Diabetes Federation Task Force on Epidemiology and Prevention; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; American Heart Association; World Heart Federation; International Atherosclerosis Society; and International Association for the Study of Obesity. Circulation 2009;120:1640–5. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.192644 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Reiner Z, Catapano AL, De Backer G, et al. . ESC/EAS Guidelines for the management of dyslipidaemias: the Task Force for the management of dyslipidaemias of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the European Atherosclerosis Society (EAS). Eur Heart J 2011;32:1769–818. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehr158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gami AS, Witt BJ, Howard DE, et al. . Metabolic syndrome and risk of incident cardiovascular events and death: a systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. J Am Coll Cardiol 2007;49:403–14. 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.09.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Naci H, Ioannidis JP. Comparative effectiveness of exercise and drug interventions on mortality outcomes: metaepidemiological study. Br J Sports Med 2015;49:1414–22. 10.1136/bjsports-2015-f5577rep [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Artero EG, Lee DC, Lavie CJ, et al. . Effects of muscular strength on cardiovascular risk factors and prognosis. J Cardiopulm Rehabil Prev 2012;32:351–8. 10.1097/HCR.0b013e3182642688 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jurca R, Lamonte MJ, Barlow CE, et al. . Association of muscular strength with incidence of metabolic syndrome in men. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2005;37:1849–55. 10.1249/01.mss.0000175865.17614.74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Earnest CP, Johannsen NM, Swift DL, et al. . Aerobic and strength training in concomitant metabolic syndrome and type 2 diabetes. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2014;46:1293–301. 10.1249/MSS.0000000000000242 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stensvold D, Tjønna AE, Skaug EA, et al. . Strength training versus aerobic interval training to modify risk factors of metabolic syndrome. J Appl Physiol (1985) 2010;108:804–10. 10.1152/japplphysiol.00996.2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Potteiger JA, Claytor RP, Hulver MW, et al. . Resistance exercise and aerobic exercise when paired with dietary energy restriction both reduce the clinical components of metabolic syndrome in previously physically inactive males. Eur J Appl Physiol 2012;112:2035–44. 10.1007/s00421-011-2174-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Saremi A, Moslehabadi M, Parastesh M. Effects of twelve-week strength training on serum chemerin, TNF-α and CRP level in subjects with the metabolic syndrome. Iran J Endocrinol Metab 2011;12:536–43. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Venojärvi M, Wasenius N, Manderoos S, et al. . Nordic walking decreased circulating chemerin and leptin concentrations in middle-aged men with impaired glucose regulation. Ann Med 2013;45:162–70. 10.3109/07853890.2012.727020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Banz WJ, Maher MA, Thompson WG, et al. . Effects of resistance versus aerobic training on coronary artery disease risk factors. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 2003;228:434–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bateman LA, Slentz CA, Willis LH, et al. . Comparison of aerobic versus resistance exercise training effects on metabolic syndrome (from the Studies of a Targeted Risk Reduction Intervention Through Defined Exercise—STRRIDE-AT/RT). Am J Cardiol 2011;108:838–44. 10.1016/j.amjcard.2011.04.037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Strasser B, Siebert U, Schobersberger W. Resistance training in the treatment of the metabolic syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis of the effect of resistance training on metabolic clustering in patients with abnormal glucose metabolism. Sports Med 2010;40:397–415. 10.2165/11531380-000000000-00000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ardern CL. Systematic review hacks for the sports and exercise clinician: five essential methodological elements. Br J Sports Med 2016;50:447–9.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Macedo LG, Elkins MR, Maher CG, et al. . There was evidence of convergent and construct validity of Physiotherapy Evidence Database quality scale for physiotherapy trials. J Clin Epidemiol 2010;63:920–5. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.10.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Maher CG, Sherrington C, Herbert RD, et al. . Reliability of the PEDro scale for rating quality of randomized controlled trials. Phys Ther 2003;83:713–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Atkins D, Best D, Briss PA, et al. . Grading quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ 2004;328:1490 10.1136/bmj.328.7454.1490 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Kunz R, et al. . What is “quality of evidence” and why is it important to clinicians? BMJ 2008;336:995–8. 10.1136/bmj.39490.551019.BE [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Verhagen AP, de Vet HC, de Bie RA, et al. . The Delphi list: a criteria list for quality assessment of randomized clinical trials for conducting systematic reviews developed by Delphi consensus. J Clin Epidemiol 1998;51:1235–41. 10.1016/S0895-4356(98)00131-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fernandez M, Hartvigsen J, Ferreira ML, et al. . Advice to stay active or structured exercise in the management of sciatica: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2015;40:1457–66. 10.1097/BRS.0000000000001036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fernandez M, Ferreira ML, Refshauge KM, et al. . Surgery or physical activity in the management of sciatica: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Spine J 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Machado AF, Ferreira PH, Micheletti JK, et al. . Can water temperature and immersion time influence the effect of cold water immersion on muscle soreness? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sports Med 2015. 10.1007/s40279-015-0431-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Higgins JPT, Green S. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0 [updated March 2011]. The Cochrane Collaboration, 2011. http://www.cochrane-handbook.org

- 25.Castaneda C, Layne JE, Munoz-Orians L, et al. . A randomized controlled trial of resistance exercise training to improve glycemic control in older adults with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 2002;25:2335–41. 10.2337/diacare.25.12.2335 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schwingshackl L, Missbach B, Dias S, et al. . Impact of different training modalities on glycaemic control and blood lipids in patients with type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Diabetologia 2014;57:1789–97. 10.1007/s00125-014-3303-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dunstan DW, Daly RM, Owen N, et al. . High-intensity resistance training improves glycemic control in older patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 2002;25:1729–36. 10.2337/diacare.25.10.1729 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kukkonen-Harjula KT, Borg PT, Nenonen AM, et al. . Effects of a weight maintenance program with or without exercise on the metabolic syndrome: a randomized trial in obese men. Prev Med 2005;41:784–90. 10.1016/j.ypmed.2005.07.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sigal RJ, Kenny GP, Boule NG, et al. . Effects of aerobic training, resistance training, or both on glycemic control in type 2 diabetes: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med 2007;147:357–69. 10.7326/0003-4819-147-6-200709180-00005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tsuzuku S, Kajioka T, Endo H, et al. . Favorable effects of non-instrumental resistance training on fat distribution and metabolic profiles in healthy elderly people. Eur J Appl Physiol 2007;99:549–55. 10.1007/s00421-006-0377-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Conceição MS, Bonganha V, Vechin FC, et al. . Sixteen weeks of resistance training can decrease the risk of metabolic syndrome in healthy postmenopausal women. Clin Interv Aging 2013;8:1221–8. 10.2147/CIA.S44245 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kemmler W, Von Stengel S, Engelke K, et al. . Exercise decreases the risk of metabolic syndrome in elderly females. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2009;41:297–305. 10.1249/MSS.0b013e31818844b7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Balducci S, Zanuso S, Nicolucci A, et al. . Effect of an intensive exercise intervention strategy on modifiable cardiovascular risk factors in subjects with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a randomized controlled trial: the Italian Diabetes and Exercise Study (IDES). Arch Intern Med 2010;170:1794–803. 10.1001/archinternmed.2010.380 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kemmler W, von Stengel S, Bebenek M, et al. . Long-term exercise and risk of metabolic and cardiac diseases: the Erlangen Fitness and Prevention Study. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med 2013;2013:768431 10.1155/2013/768431 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rodriguez-Escudero JP, Somers VK, Heath AL, et al. . Effect of a lifestyle therapy program using cardiac rehabilitation resources on metabolic syndrome components. J Cardiopulm Rehabil Prev 2013;33:360–70. 10.1097/HCR.0b013e3182a52762 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bouchonville M, Armamento-Villareal R, Shah K, et al. . Weight loss, exercise or both and cardiometabolic risk factors in obese older adults: results of a randomized controlled trial. Int J Obes (Lond) 2014;38:423–31. 10.1038/ijo.2013.122 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Levinger I, Goodman C, Peake J, et al. . Inflammation, hepatic enzymes and resistance training in individuals with metabolic risk factors. Diabet Med 2009;26:220–7. 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2009.02679.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Stensvold D, Slørdahl SA, Wisløff U. Effect of exercise training on inflammation status among people with metabolic syndrome. Metab Syndr Relat Disord 2012;10:267–72. 10.1089/met.2011.0140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Venojärvi M, Korkmaz A, Wasenius N, et al. . 12 weeks’ aerobic and resistance training without dietary intervention did not influence oxidative stress but aerobic training decreased atherogenic index in middle-aged men with impaired glucose regulation. Food Chem Toxicol 2013;61:127–35. 10.1016/j.fct.2013.04.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ho S, Pal S, Hills AP, et al. . Twelve weeks of moderate aerobic, resistance and combination exercise training improves chronic disease risk factors in overweight and obese subjects. Obes Rev 2010;11:385. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pattyn N, Cornelissen VA, Eshghi SR, et al. . The effect of exercise on the cardiovascular risk factors constituting the metabolic syndrome: a meta-analysis of controlled trials. Sports Med 2013;43:121–33. 10.1007/s40279-012-0003-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cornelissen VA, Fagard RH, Coeckelberghs E, et al. . Impact of resistance training on blood pressure and other cardiovascular risk factors: a meta-analysis of randomized, controlled trials. Hypertension 2011;58:950–8. 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.111.177071 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lewington S, Clarke R, Qizilbash N, et al. . Age-specific relevance of usual blood pressure to vascular mortality: a meta-analysis of individual data for one million adults in 61 prospective studies. Lancet 2002;360:1903–13. 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)11911-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Polotsky HN, Polotsky AJ. Metabolic implications of menopause. Semin Reprod Med 2010;28:426–34. 10.1055/s-0030-1262902 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bjsports-2015-094715supp_tables.pdf (1.1MB, pdf)

bjsports-2015-094715supp_figures.pdf (2.9MB, pdf)