The PERK luminal domain can function as a molecular chaperone to recognize and bind misfolded proteins. The crystal structure of the PERK luminal domain suggests that it may utilize a flexible β-sandwich domain to recognize and interact with a broad range of misfolded proteins.

Keywords: ER stress, molecular chaperones, PERK, crystal structure, misfolded proteins

Abstract

PERK is one of the major sensor proteins which can detect the protein-folding imbalance generated by endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress. It remains unclear how the sensor protein PERK is activated by ER stress. It has been demonstrated that the PERK luminal domain can recognize and selectively interact with misfolded proteins but not native proteins. Moreover, the PERK luminal domain may function as a molecular chaperone to directly bind to and suppress the aggregation of a number of misfolded model proteins. The data strongly support the hypothesis that the PERK luminal domain can interact directly with misfolded proteins to induce ER stress signaling. To illustrate the mechanism by which the PERK luminal domain interacts with misfolded proteins, the crystal structure of the human PERK luminal domain was determined to 3.2 Å resolution. Two dimers of the PERK luminal domain constitute a tetramer in the asymmetric unit. Superimposition of the PERK luminal domain molecules indicated that the β-sandwich domain could adopt multiple conformations. It is hypothesized that the PERK luminal domain may utilize its flexible β-sandwich domain to recognize and interact with a broad range of misfolded proteins.

1. Introduction

A number of exogenous and endogenous factors such as UV radiation, reactive oxygen species, hypoxia, protein mutations and nutrient starvation may disturb protein maturation in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) and lead to ER stress. To resolve the imbalance in protein-folding homeostasis, eukaryotic cells unleash the evolutionarily conserved, ER-specific unfolded protein response (UPR; Ron & Walter, 2007 ▸; Schröder & Kaufman, 2005 ▸; Rutkowski & Kaufman, 2007 ▸; Wek et al., 2006 ▸; Walter & Ron, 2011 ▸). This elaborate UPR signaling cascade relies on three independent ER-resident stress sensors: PERK [double-stranded RNA-dependent protein kinase (PRK)-like ER kinase], IRE1 (inositol-requiring 1) and ATF6 (activating transcription factor 6). The mechanism by which the sensor proteins are activated during ER stress remains unclear, particularly for PERK. It was proposed that under nonstressed conditions these ER sensor proteins are inactivated by binding to Bip. During ER stress, protein misfolding induces dissociation of Bip from the sensor proteins (Bertolotti et al., 2000 ▸; Ma et al., 2002 ▸). It has been reported that the misfolded protein may interact directly with the sensor proteins PERK and IRE1 to induce protein oligomerization, which can lead to the activation of PERK and IRE1 (Ron & Walter, 2007 ▸; Credle et al., 2005 ▸; Zhou et al., 2006 ▸; Gardner & Walter, 2011 ▸).

The UPR may alleviate ER stress by regulating a number of transcription pathways. The activation of PERK can shut down global protein translation in order to reduce the ER protein input (Ron & Walter, 2007 ▸; Wang & Kaufman, 2014 ▸). The activation of IRE1 may promote protein folding by overexpressing ER molecular chaperones (Kang et al., 2006 ▸; Hollien & Weissmann, 2006 ▸). ATF6, when activated, undergoes proteolytic cleavage in the Golgi apparatus (Rutkowski & Kaufman, 2007 ▸). The cytosolic portion of ATF6 migrates to the nucleus to induce the transcription of ER molecular chaperones. Collectively, activation of UPR may restore the homeostasis of the ER. If UPR fails to rescue the ER stress, the cell may go through apoptosis (Lin et al., 2007 ▸). Fungal cells contain only the IRE1 branch of the UPR signaling cascade, while metazoan cells have all three arms of the ER stress signaling pathways (Wang & Kaufman, 2014 ▸; Walter & Ron, 2011 ▸).

Both PERK and IRE1 are type I ER transmembrane proteins. During ER stress, the misfolded protein may induce the oligomerization of the N-terminal ER luminal domains of PERK and IRE1. The cytosolic kinase domain of PERK, upon oligomerization, can be activated by autophosphorylation. The PERK cytosolic kinase domain then recruits and phosphorylates the substrate protein eIF2α. The phosphorylation of eIF2α by PERK shuts off overall protein translation (Harding et al., 1999 ▸). After oligomerization induced by ER stress, IRE1 can activate its cytosolic RNAse activity by autophosphorylation. IRE1 can subsequently cause XBP1 (termed HAC1 in yeast) mRNA splicing. The spliced XBP1 acts as a transcription factor to induce expression of the ER molecular chaperone (Sidrauski & Walter, 1997 ▸; Cox & Walter, 1996 ▸). Therefore, PERK and IRE1, when activated, may initiate distinct pathways to handle ER stress.

Genetic and biochemical data have strongly indicated that the ER stress and UPR pathways play essential roles in the development and progression of a number of diseases such as cardiovascular disorders, diabetes and cancers (Wouters & Koritzinsky, 2008 ▸; Minamino et al., 2010 ▸; Sozen et al., 2015 ▸; Nawrocki et al., 2005 ▸; Li et al., 2011 ▸; Oakes & Papa, 2015 ▸). Accumulating evidence has demonstrated that intervention in the pro-apoptotic signaling of ER stress and UPR may be promising strategies for the treatment of cancers and diabetes (Minamino et al., 2010 ▸; Kim et al., 2009 ▸; Zhao et al., 2008 ▸; Cheng et al., 2009 ▸). Understanding the mechanism by which misfolded proteins interact with PERK and IRE1 to activate ER stress may facilitate the identification of inhibitors of IRE1 and PERK as novel drug candidates for a number of diseases.

It remains unclear how ER stress induces the oligomerizations of PERK luminal domains. Our data have indicated that the PERK luminal domain can selectively interact with misfolded proteins but not native proteins. Our hypothesis is that misfolded proteins may activate UPR signaling by directly binding to PERK luminal domains. The binding of PERK and IRE1 to the misfolded proteins induces oligomerization of these ER stress sensor proteins and initiates UPR signaling (Cui et al., 2011 ▸). The crystal structure of the PERK luminal domain is available (Carrara et al., 2015 ▸). However, the structure of the PERK luminal domain cannot provide a clear picture to explain how PERK interacts with misfolded proteins. In this study, we have determined the crystal structure of the PERK luminal domain to 3.2 Å resolution in a different space group from the previously reported structure. The structural analysis suggested that the PERK luminal domain may utilize a flexible β-sandwich domain to recognize and interact with a broad range of misfolded proteins. Taken together, the data provide solid evidence for our hypothesis that the misfolded protein can directly bind the PERK luminal domain to activate ER stress signaling.

2. Methods

2.1. Protein expression and purification

Human PERK luminal domain (hPERK-LD; residues 95–420) was amplified from full-length human PERK cDNA using PCR and cloned into pET-28b. The protein was expressed in Escherichia coli strain BL21 (DE3) grown in LB medium at 37°C. Protein expression was induced by 0.5 mM IPTG when the cells reached an OD600 of 0.6. The cells were harvested, washed in 100 ml binding buffer (10 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl) and then lysed by sonication on ice. The lysate was clarified by centrifugation at 12 000 rev min−1 for 30 min. The supernatant was loaded onto an Ni2+–NTA column pre-equilibrated with binding buffer. The resin was washed with ice-cold washing buffer (20 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.9, 0.5 M NaCl, 60 mM imidazole) and the His-tagged hPERK-LD was eluted using elution buffer (20 mM Tris–HCl buffer pH 7.9, 0.5 M NaCl, 100 mM EDTA). The typical yield of soluble protein (>95% pure from SDS–PAGE analysis) from 1 l of culture was about 40 mg. The protein was then treated with thrombin (one unit per 1 mg protein) at 4°C overnight to remove the polyhistidine tag. The final eluate was subsequently loaded onto a Superdex 200 column (Amersham Biosciences) in 10 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.5, 100 mM NaCl.

2.2. ELISA assay

The binding between hPERK-LD and the denatured proteins was tested using an ELISA assay. The model proteins transferrin, lysome and rhodanese (1 mg ml−1) were denatured using denaturing buffer [50 mM Tris–HCl pH 8.0, 6 M guanidine, 0.1%(v/v) β-mercaptoethanol] and incubated at room temperature for 2 h. The guanidine-denatured transferrin, lysome and rhodanese were diluted to the desired concentrations in PBS and immobilized on an EIA/RIA plate (Corning Incorporated, Corning, New York, USA) for 1 h at room temperature. Native transferrin, lysome and rhodanese in PBS were also coated as controls. The coated plate was washed three times with 200 µl PBST (PBS with 0.2% Tween 20). To block the wells, 200 µl of 1% BSA in PBS was incubated in the wells for 1 h at room temperature. His-tagged hPERK-LD (50 µg ml−1) was then added to the wells for 1 h. After extensive washing with PBST, the bound hPERK-LD can be detected using an HRP-conjugated 6×His epitope tag antibody (Thermal Fisher Scientific, Madison, Wisconsin, USA). OD450 readings were measured after TMP was added to the wells as an HRP substrate.

The binding between hPERK-LD and the denatured proteins can also be examined by using an alternative ELISA assay. hPERK-LD (100 µl of protein at 50 µg ml−1 in PBS) was incubated in the wells of a 96-well EIA/RIA plate for 1 h at room temperature. The protein solutions were then decanted and the wells were washed three times with 200 µl PBST (PBS with 0.2% Tween 20). To block the wells, 200 µl of 1% BSA in PBS was incubated in the wells for 1 h at room temperature. After blocking, the wells were washed three times with 200 µl PBST. Rhodanese (1 mg ml−1; Sigma) was denatured in denaturing buffer [50 mM Tris–HCl pH 8.0, 6 M guanidine, 0.1%(v/v) β-mercaptoethanol] and incubated at room temperature for 2 h. The denatured rhodanese was then diluted in PBS to different concentrations, added to the wells coated with hPERK-LD and then incubated at room temperature for 1 h. Native rhodanese was also added to the coated wells as a comparision. After decanting all liquid, all wells were washed three times with 200 µl PBST. Following this, 100 µl anti-rhodanese goat polyclonal IgG (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, California, USA) was added to the corresponding wells and incubated for 1 h at room temperature. After washing three times with 200 µl PBST, the wells were then incubated with 100 µl of donkey anti-goat HRP-conjugated IgG (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, California, USA) for 30 min at room temperature. The wells were then washed six times with 200 µl PBST and the amount of secondary antibody was measured using TMB peroxidase substrate (Thermal Fisher Scientific, Madison, Wisconsin, USA). The absorbance at 450 nm was measured with a UV micro-plate reader (Bio-Rad, Hercules, California, USA).

2.3. Pull-down assay

200 µl purified hPERK-LD (500 µg ml−1) was mixed with 50 µl charged Ni2+–NTA beads in PBS buffer and incubated for 10 min. The mixture was centrifuged at 800g for 2 min. After washing with PBS buffer, the beads were resuspended in 1 ml buffer consisting of 10 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl. Denatured or native rhodanese (a total amount of 1 or 2 µg, as shown in the figure legends) was added to the beads. After incubation for 10 min at room temperature, the mixture was centrifuged at 800g for 2 min and the supernatant was then removed. The beads were washed three times with PBST. 50 µl sample buffer was added to the beads and heated at 90°C for 5 min. Western blotting was carried out to examine the level of rhodanese bound to hPERK-LD. The anti-rhodanese goat polyclonal IgG was utilized to detect the blotted rhodanese. Donkey anti-goat HRP-conjugated IgG (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, California, USA) was used as the secondary antibody and the amount of secondary antibody was measured using CN/DAB as a substrate.

2.4. Aggregation suppression assay

The molecular-chaperone activity of the PERK luminal domain was determined by monitoring the heat-induced aggregation of alcohol dehydrogenase (ADH) and rhodanese in the presence or absence of hPERK-LD. ADH (10 µM) or rhodanese (2.5 µM) was pre-mixed with different concentration of hPERK-LD (1.25, 2.5 or 5 µM; see figure legends for details). The mixtures were incubated at 50°C and the heat-induced protein aggregation was monitored by light scattering at OD320. ADH or rhodanese in PBS was used as a negative control.

2.5. Crystallization and structure determination

Crystals of the human PERK luminal domain were grown using the hanging-drop vapor-diffusion method in a condition consisting of 100 mM MES pH 6.0, 10–15% PEG 3350. The crystals diffracted X-rays to 3.2 Å resolution using the SER-CAT synchrotron beamline at APS. The atomic coordinates of the human PERK luminal domain structure (PDB entry 4yzs) were used as a search model for the molecular-replacement method with Phaser (McCoy et al., 2007 ▸). The model was manually built by Coot (Emsley & Cowtan, 2004 ▸). Structure refinement was carried out with PHENIX (Adams et al., 2010 ▸). The coordinates and structure factors of the crystal structure of the human PERK luminal domain have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank with accession code 5sv7. Data-collection and structure-refinement statistics are given in Table 1 ▸.

Table 1. Data collection and structure determination of the human PERK luminal domain.

Values in parentheses are for the highest resolution shell.

| Data collection | |

| Space group | P32 |

| a, b, c (Å) | 163.913, 163.913, 63.076 |

| α, β, γ (°) | 90.00, 90.00, 120.00 |

| Wavelength (Å) | 1.000 |

| Resolution (Å) | 38.52–3.20 (3.34–3.20) |

| R sym or R merge | 0.054 (0.417) |

| 〈I/σ(I)〉 | 40.4 (1.96) |

| Completeness (%) | 99.6 (99.1) |

| Multiplicity | 9.4 (8.1) |

| Refinement | |

| Resolution (Å) | 3.20 |

| No. of reflections | 30417 (1572) |

| R work/R free | 0.273 (0.290)/0.322(0.357) |

| No. of atoms | |

| Protein | 6573 |

| Water | 29 |

| B factors (Å2) | |

| Protein | 36.10 |

| Water | 64.5 |

| R.m.s. deviations | |

| Bond lengths (Å) | 0.012 |

| Bond angles (°) | 1.699 |

3. Results and discussions

3.1. The PERK luminal domain selectively binds denatured proteins over native proteins

Recombinant human PERK ER luminal domain (PERK residues 95–420) produced from E. coli was purified using a nickel-chelating column followed by a Superdex 200 gel-filtration column (GE Healthcare). The gel-filtration profile of the PERK luminal domain indicated that it forms a homodimer in solution (Supplementary Fig. S1).

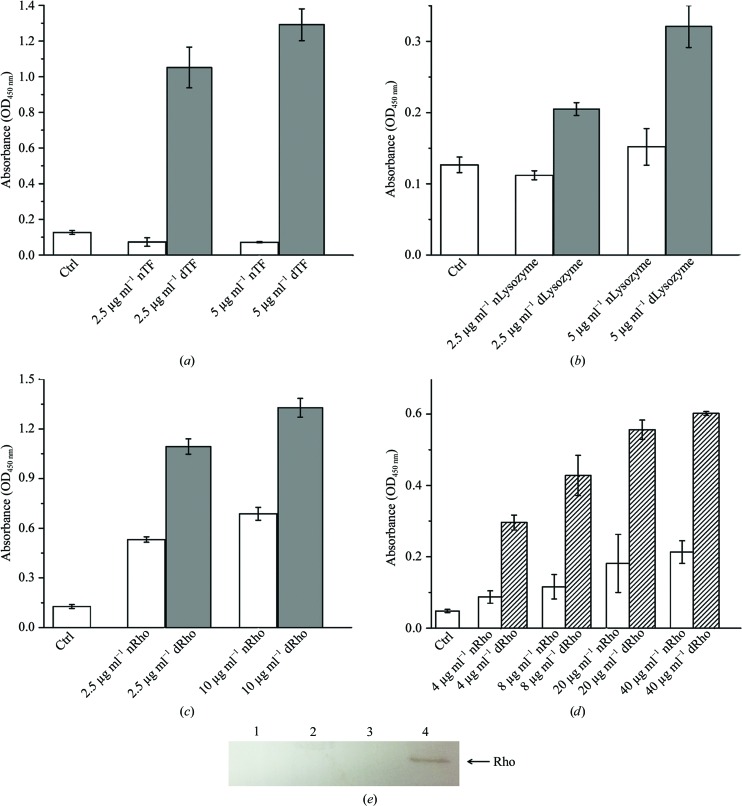

As an ER stress sensor protein, PERK has been proposed to be directly activated by ER misfolded proteins (Credle et al., 2005 ▸). To examine the ability of PERK to interact with the misfolded proteins, we established an ELISA assay using transferrin, lysozyme and rhodanese as the model proteins. To detect the bound PERK luminal domain in the ELISA assays, we generated an N-terminally His-tagged recombinant human PERK luminal domain. In one ELISA assay, the chemically denatured model proteins were coated onto the plate and the bound PERK luminal domain was detected using anti-His-tag antibody. Alternatively, the ELISA assay can be performed by coating the PERK luminal domain onto the plate and then adding denatured model proteins. The bound denatured model proteins were examined using specific antibodies. The data from both cases clearly showed that the PERK luminal domain can selectively recognize and bind a wide range of misfolded proteins but not native proteins (Fig. 1 ▸).

Figure 1.

The PERK luminal domain can directly interact with denatured model proteins as shown by ELISA assays. (a) Chemically denatured human transferrin (labeled dTF) at various concentrations (0 in the control, 2.5 and 5 µg ml−1) was coated onto the plate. Native transferrin (labeled nTF) was coated onto the plate as well. A blank well was utilized as a control (labeled Ctrl). After blocking the plate with BSA, human PERK luminal domain at 50 µg ml−1 was added to the wells. After washing, bound PERK luminal domain was detected using anti-His-tag antibody (see §2 for details). The OD450 readings are shown as gray bars. The standard derivations of three independent experiments are indicated by bars. (b) The PERK luminal domain can directly bind denatured lysozyme coated on the plate. Native and denatured lysozyme are labeled nLysozyme and dLysozyme, respectively. (c) The PERK luminal domain can interact with denatured rhodanese coated on the plate. Native and denatured rhodanese are labeled nRho and dRho, respectively. (d) In this experiment, PERK luminal domain at 50 µg ml−1 was coated onto the wells and native (labeled nRho) and chemically denatured rhodanese (labeled dRho) at various concentrations (0 as a negative control, 4, 8, 20 and 40 µg ml−1) were added. The bound rhodanese can be detected by using the anti-rhodanese antibody. The OD450 readings are shown as open bars. The standard derivations of three independent experiments are indicated by bars. (e) A pull-down assay showing that the PERK luminal domain selectively recognizes and binds the misfolded model protein rhodanese. Purified PERK luminal domain was immobilized on Ni–NTA beads. After washing, denatured or native rhodanese was added to the beads. After extensive washing, Western blotting was performed to show the level of bound rhodanese to PERK luminal domain immobilized on the Ni beads. Lane 1, beads only, without bound PERK, as the control. 2 µg native rhodanese was added to the reaction. Lane 2, beads previously bound with PERK luminal domain. 2 µg native rhodanese was added to the reaction. Lane 3, beads only, without bound PERK, as a control. 2 µg denatured rhodanese was included in the reaction. Lane 4, beads previously bound with PERK luminal domain. 2 µg denatured rhodanese was added to the reaction. The position of rhodanese (Rho) on the membrane is indicated by an arrow.

To further confirm the interaction between the PERK ER luminal domain and misfolded proteins, we performed a pull-down assay using recombinant human PERK luminal domain and the denatured model protein rhodanese (Fig. 1 ▸ e). The data from our pull-down assay clearly showed that the PERK ER luminal domain specifically recognizes and interacts with misfolded rhodanese over native rhodanese. The binding between the PERK ER luminal domain and the misfolded protein is direct and does not require any mediator proteins such as the molecular chaperone Bip. In addition, the PERK luminal domain can recognize and bind to a broad range of denatured model proteins, including insulin, luciferase and citrate synthase (data not shown). The data suggested that misfolded ER proteins may interact directly with the PERK luminal domain to induce UPR signaling during ER stress.

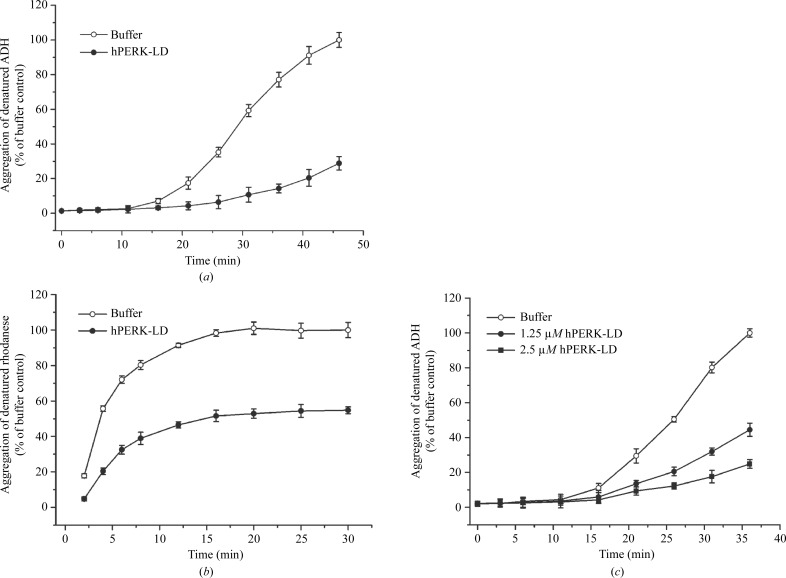

3.2. The PERK luminal domain functions as a molecular chaperone to suppress protein aggregation

A common feature of molecular chaperones is the ability to suppress misfolded protein aggregation induced by heat or chemical denaturation (Tao et al., 2010 ▸; Li & Sha, 2005 ▸). Because the PERK luminal domain can selectively bind misfolded proteins but not native proteins, it would be interesting to examine whether the PERK luminal domain functions as a molecular chaperone to suppress protein aggregation. Here, we have developed a protein-aggregation suppression assay to demonstrate that the PERK luminal domain can efficiently protect denatured protein from aggregating (Fig. 2 ▸). The data clearly indicate that the PERK luminal domain acts as a molecular chaperone to suppress heat-induced model-protein aggregation independently of Bip. The PERK luminal domain suppresses protein aggregation in a dose-dependent fashion (Fig. 2 ▸). It is highly likely that the PERK luminal domain functions a molecular chaperone to suppress protein aggregation by direct binding to the exposed hydrophobic stretches in the denatured proteins.

Figure 2.

The PERK luminal domain functions as a molecular chaperone to suppress protein aggregation. (a) Protein-aggregation suppression assay for human PERK luminal domain (hPERK-LD) using alcohol dehydrogenase (ADH) as the model protein. 5 µM hPERK-LD and 10 µM ADH were utilized in this reaction. Heat-induced ADH aggregation was monitored by light scattering at OD320 at 5 min intervals. The OD320 readings are shown on the vertical axis (as a percentage of the maximum value for the buffer control) and time in minutes is indicated on the horizontal axis. (b) Protein-aggregation suppression assay for hPERK-LD using rhodanese as the model protein. 2.5 µM hPERK-LD and 2.5 µM rhodanese were utilized in this experiment. (c) In this experiment, two different concentrations of the PERK luminal domain (1.25 and 2.5 µM) were utilized in the protein-aggregation suppression assay. 10 µM ADH was present in the reaction. The data indicated that the PERK luminal domain can suppress the heat-induced aggregation of ADH in a dose-depedent manner. The standard derivations of three independent experiments are indicated by the bars.

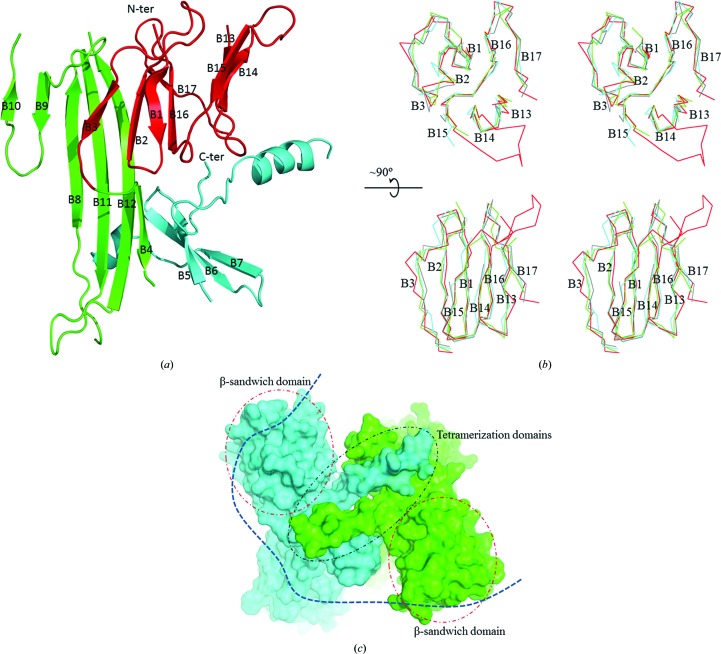

3.3. The crystal structure of the PERK luminal domain suggests the binding site for the misfolded proteins

We have determined the crystal structure of the human PERK luminal domain to 3.2 Å resolution. The crystal structure was determined in space group P32, which differs from the previous determined crystal structure of the human PERK luminal domain (P41212). In our newly determined crystal structure, two PERK luminal domain dimers are present in one asymmetric unit, while in the previously determined structure only one dimer was found.

Our human PERK luminal domain monomer primarily contains three domains: a dimerization domain, a β-sandwich domain and a tetramerization domain (Fig. 3 ▸ a). A total of 19 β-strands (named B1–B19 from the N-terminus to the C-terminus) and one α-helix (A1) are found in one monomer. The dimerization domain forms a continuous β-sheet with the dimerization domain from the other monomer within the dimer. The β-sandwich domain of hPERK-LD contains two layers of β-sheets (layers I and II; Fig. 3b ▸). The tetramerization domain is composed of a helix and a short β-hairpin that shake hands with their counterparts from the other dimer in the structure. The two dimers of the PERK luminal domain dock onto each other to form a tetramer via the tetramerization domain in the asymmetric unit. The tetramer formation (docking of two dimers) in our structure is very similar to that in the previously determined structure.

Figure 3.

The crystal structure of the human PERK luminal domain determined to 3.2 Å resolution. (a) The structure of the PERK luminal domain monomer. The β-sandwich domain, the dimerization domain and the tetramerization domain are shown in red, green and cyan, respectively. The N-terminus and C-terminus of the protein are labeled. The 17 β-strands are labeled B1–B17. (b) Superimposition of the β-sandwich domains from monomers A (in green), B (in red), C (in cyan) and D (in gray) in one asymmetric unit indicates the multiple conformations of this domain. The β-sandwich domain is shown using a Cα-trace drawing in stereo mode. The β-strands that form this domain are labeled. B1–B3, B16 and B17 constitute β-sheet layer I and B13–B15 comprise layer II. The bottom panel was generated by rotating the β-sandwich domain in the top panel by 90° along the horizontal axis. The N-terminus of the protein is labeled. The structure comparison shows that β-strand B3 and the loop connecting B2 and B3 on the N-terminal surface adopt multiple conformations. The loop connecting B14 and B15 is also located on the N-terminal surface but is not visible in the structures of monomers A, C and D. It is only ordered in monomer B (in red), indicating significant flexibility of this region. (c) A surface drawing of the PERK luminal domain tetramer in one asymmetric unit. One PERK dimer is shown in cyan and the other dimer is in green. The two β-sandwich domains located on the top of the two dimers are shown as dotted circles and labeled. The docked tetramerization domains are circled and labeled. The putatively bound misfolded protein chain is shown by a dotted line in dark blue. It is possible that the misfolded protein may induce PERK tetramerization by binding directly to the β-sandwich domains of the PERK luminal domain dimers.

Because our data show that the PERK luminal domain can interact directly with misfolded proteins to suppress protein aggregation, it is of great interest to identify the peptide-binding site in the PERK luminal domain structure. As a molecular chaperone, the PERK luminal domain maintains the capability to interact with a wide range of misfolded proteins, and it is likely that the peptide-binding site of the PERK luminal domain may adopt multiple conformations. The structural flexibility may allow the PERK luminal domain to bind various types of misfolded proteins. A number of molecular chaperones, including trigger factor, Hsp90, GroEL, Hsp40 and sHsp, have been reported to contain flexible regions that interact with client proteins (Kaiser et al., 2006 ▸; Lakshmipathy et al., 2010 ▸; Horwich et al., 2007 ▸; Southworth & Agard, 2011 ▸; Taipale et al., 2010 ▸; Li et al., 2003 ▸; Sha et al., 2000 ▸; Jaya et al., 2009 ▸).

Two PERK luminal dimers are present in one asymmetric unit in our structure, which provides us with an opportunity to examine which domains within the PERK luminal domain structure are flexible and may represent the peptide-binding site of PERK. Superimposition of the four PERK monomers within the asymmetric unit indicates that the dimerization domains and the tetramerization domains of the PERK luminal domains can be aligned very well among the four molecules. In contrast, the β-sandwich domains adopt distinct conformations (Fig. 3 ▸ b). The root-mean-square deviation (r.m.s.d) for the main-chain atoms of the β-sandwich domains is ∼1.5 Å when the four monomers are superimposed, while the r.m.s.d for the main-chain atoms of the other parts of the structure is 0.81 Å, showing that significant flexibility occurs within this β-sandwich domain. The β-sandwich domain of hPERK-LD contains two layers of β-sheets (layers I and II). β-Strands B1–B3, B16 and B17 form layer I and β-strands B13–B15 constitute layer II. In layer I, β-strand B3 and the loop connecting B2 and B3 show great structural variation. In layer II, the loop connecting β-strands B14 and B15 is visible in monomer B while it is disordered in the other monomers (Fig. 3b ▸). Therefore, the loop connecting B14 and B15 has significant structural flexibility.

We hypothesize that the β-sandwich domain of hPERK-LD may represent the peptide-binding site that interacts with misfolded proteins. Several lines of evidence support our hypothesis. (i) The β-sandwich domain of hPERK-LD may adopt multiple conformations to interact with a broad range of misfolded proteins. The structural flexibility of the β-sandwich domain may enable hPERK-LD to recognize and bind misfolded proteins with side chains of different sizes and hydrophobicities. (ii) The structure of the β-sandwich domain of hPERK-LD mimics that of a single-domain antibody or the VH/VL domains of an antibody. All of them contain two layers of β-sheets with the N-terminus at one end of the structure and the C-terminus at the other end. Single-domain antibodies or the similar VH/VL domains of antibodies interact with antigens via the N-terminal complementary-determining regions (CDRs). In the β-sandwich domain of hPERK-LD, the N-terminal loops that connect β-strands B2 and B3 and β-strands B14 and B15 are flexible, as shown by structure superimposition. It is possible that these flexible loops may play important roles in recognizing and binding the misfolded proteins. (iii) In the tetrameric structure of the PERK luminal domain, the docked tetramerization domains are flanked by the β-sandwich domains from two dimers (Fig. 3c ▸). One can imagine that the simultaneous binding of the β-sandwich domains to one chain of misfolded polypeptide can greatly enhance the possibility of docking and handshaking between the two tetramerization domains of hPERK LD. Therefore, the β-sandwich domain is ideally positioned to interact with the misfolded protein to induce the oligomerization of PERK for subsequent ER stress activation.

It is likely that the PERK luminal domain binds misfolded proteins via hydrophobic interactions, as most molecular chaperones do. We examined the exposed molecular surface of the hPERK-LD β-sandwich domain for a large hydrophobic regions. Interestingly, a large hydrophobic patch exists on the N-terminal surface of the β-sandwich domain (Supplementary Fig. S2a and S2b). The residues within the PERK luminal domain which constitute this large hydrophobic patch are highly conserved among species (Supplementary Fig. S3).

We reasoned that mutations within the hPERK-LD β-sandwich domain may diminish the binding capability of the PERK luminal domain to the peptide substrate. Therefore, we constructed two PERK luminal domain mutations, Δ298 and Δ344, in which residues 298–309 (representing β-strand B13) and residues 344–355 (representing β-strand B17) were replaced by the flexible linker (G3S)3, respectively. The Δ298 mutant cannot be expressed in soluble form from E. coli or Pichia systems. The Δ344 mutant can be expressed in E. coli and purified. An ELISA assay clearly showed that the hPERK-LD Δ344 mutant exhibited a reduced ability to interact with the denatured model protein rhodanese (Supplementary Fig. S4). The data strongly support the hypothesis that the hPERK-LD β-sandwich domain may represent the peptide-binding site for misfolded proteins.

In our previous studies, we proposed a ‘line-up’ model to illustrate the mechanism by which ER misfolded proteins interact with PERK luminal domains to induce the oligomerization of PERK homodimers (Cui et al., 2011 ▸). In this paper, we show solid evidence that the PERK luminal domain can interact directly with misfolded model proteins by various ELISA assays. The PERK luminal domain may function as a molecular chaperone to suppress heat-induced protein aggregation. Our crystal structure of the PERK luminal domain suggested that the β-sandwich domain may represent the peptide-binding site for misfolded proteins. The data greatly enhance our understanding of the mechanism by which the misfolded proteins can induce PERK oligomerization to activate ER stress signaling.

Supplementary Material

PDB reference: PERK luminal domain, 5sv7

Supporting Information.. DOI: 10.1107/S2059798316018064/qh5043sup1.pdf

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the staff scientists at the APS SER-CAT beamline for their help in data collection. This work was supported by a grant from the NIH (R01 GM080261).

References

- Adams, P. D. et al. (2010). Acta Cryst. D66, 213–221.

- Bertolotti, A., Zhang, Y., Hendershot, L. M., Harding, H. P. & Ron, D. (2000). Nature Cell. Biol. 2, 326–332. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Carrara, M., Prischi, F., Nowak, P. R. & Ali, M. M. (2015). EMBO J. 34, 1589–1600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Cheng, W. P., Wang, B. W. & Shyu, K. G. (2009). Eur. J. Clin. Invest. 39, 960–971. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Cox, J. S. & Walter, P. (1996). Cell, 87, 391–404. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Credle, J. J., Finer-Moore, J. S., Papa, F. R., Stroud, R. M. & Walter, P. (2005). Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 102, 18773–18784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Cui, W., Li, J., Ron, D. & Sha, B. (2011). Acta Cryst. D67, 423–428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Emsley, P. & Cowtan, K. (2004). Acta Cryst. D60, 2126–2132. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Gardner, B. M. & Walter, P. (2011). Science, 333, 1891–1894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Harding, H. P., Zhang, Y. & Ron, D. (1999). Nature (London), 397, 271–274. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Hollien, J. & Weissmann, J. S. (2006). Science, 313, 104–107. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Horwich, A. L., Fenton, W. A., Chapman, E. & Farr, G. W. (2007). Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 23, 115–145. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Jaya, N., Garcia, V. & Vierling, E. (2009). Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 106, 15604–15609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Kaiser, C. M., Chang, H.-C., Agashe, V. R., Lakshmipathy, S. K., Etchells, S. A., Hayer-Hartl, M., Hartl, F. U. & Barral, J. M. (2006). Nature (London), 444, 455–460. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Kang, S.-W., Rane, N. S., Kim, S. J., Garrison, J. L., Taunton, J. & Hegde, R. S. (2006). Cell, 127, 999–1013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Kim, I., Shu, C.-W., Xu, W., Shiau, C.-W., Grant, D., Vasile, S., Cosford, N. D. P. & Reed, J. C. (2009). J. Biol. Chem. 284, 1593–1603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Lakshmipathy, S. K., Gupta, R., Pinkert, S., Etchells, S. A. & Hartl, F. U. (2010). J. Biol. Chem. 285, 27911–27923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Li, J., Qian, X. & Sha, B. (2003). Structure, 11, 1475–1483. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Li, J. & Sha, B. (2005). Biochem. J. 386, 453–460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Li, X., Zhang, K. & Li, Z. (2011). J. Hematol. Oncol. 4, 8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Lin, J. H., Li, H., Yasumura, D., Cohen, H. R., Zhang, C., Panning, B., Shokat, K. M., LaVail, M. M. & Walter, P. (2007). Science, 318, 944–949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Ma, K., Vattem, K. M. & Wek, R. C. (2002). J. Biol. Chem. 277, 18728–18735. [DOI] [PubMed]

- McCoy, A. J., Grosse-Kunstleve, R. W., Adams, P. D., Winn, M. D., Storoni, L. C. & Read, R. J. (2007). J. Appl. Cryst. 40, 658–674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Minamino, T., Komuro, I. & Kitakaze, M. (2010). Circ. Res. 107, 1071–1082. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Nawrocki, S. T., Carew, J. S., Pino, M. S., Highshaw, R. A., Dunner, K. Jr, Huang, P., Abbruzzese, J. L. & McConkey, D. J. (2005). Cancer Res. 65, 11658–11666. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Oakes, S. A. & Papa, F. R. (2015). Annu. Rev. Pathol. Mech. Dis. 10, 173–194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Ron, D. & Walter, P. (2007). Nature Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 8, 519–529. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Rutkowski, D. T. & Kaufman, R. J. (2007). Trends Biochem. Sci. 32, 469–476. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Schröder, M. & Kaufman, R. J. (2005). Annu. Rev. Biochem. 74, 739–789. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Sha, B., Lee, S. & Cyr, D. M. (2000). Structure, 8, 799–807. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Sidrauski, C. & Walter, P. (1997). Cell, 90, 1031–1039. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Southworth, D. R. & Agard, D. A. (2011). Mol. Cell, 42, 771–781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Sozen, E., Karademir, B. & Ozer, N. K. (2015). Free Radical Biol. Med. 78, 30–41. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Taipale, M., Jarosz, D. F. & Lindquist, S. (2010). Nature Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 11, 515–528. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Tao, J., Petrova, K., Ron, D. & Sha, B. (2010). J. Mol. Biol. 397, 1307–1315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Walter, P. & Ron, D. (2011). Science, 334, 1081–1086. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Wang, M. & Kaufman, R. J. (2014). Nature Rev. Cancer, 14, 581–597. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Wek, R. C., Jiang, H.-Y. & Anthony, T. G. (2006). Biochem. Soc. Trans. 34, 7–11. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Wouters, B. G. & Koritzinsky, M. (2008). Nature Rev. Cancer, 8, 851–864. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Zhao, H., Liao, Y., Minamino, T., Asano, Y., Asakura, M., Kim, J., Asanuma, H., Takashima, S., Hori, M. & Kitakaze, M. (2008). Hypertens. Res. 31, 1977–1987. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Zhou, J., Liu, C. Y., Back, S. H., Clark, R. L., Peisach, D., Xu, Z. & Kaufman, R. J. (2006). Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 103, 14343–14348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

PDB reference: PERK luminal domain, 5sv7

Supporting Information.. DOI: 10.1107/S2059798316018064/qh5043sup1.pdf