Abstract

Background & Aims

Current research focuses on developing alternative strategies to restore decreased liver mass prior to the onset of endstage liver disease. Cell engraftment/repopulation requires regeneration in normal liver, but we have shown that severe liver injury stimulates repopulation without partial hepatectomy (PH). We have now investigated whether a less severe injury, secondary biliary fibrosis, would drive engraftment/repopulation of ectopically transplanted mature hepatocytes.

Methods

Ductular proliferation and progressive fibrosis in DPPIV− F344 rats was induced by common bile duct ligation (BDL). Purified DPPIV+/GFP+ hepatocytes were infused without PH into the spleen of BDL rats and compared to rats without BDL.

Results

Within one week, transplanted hepatocytes were detected in hepatic portal areas and at the periphery of expanding portal regions. DPPIV+/GFP+ repopulating cell clusters of different sizes were observed in BDL rats but not untreated normal recipients. Surprisingly, some engrafted hepatocytes formed CK-19/claudin-7 expressing epithelial cells resembling cholangiocytes within repopulating clusters. In addition, substantial numbers of hepatocytes engrafted at the intrasplenic injection site assembled into multicellular groups. These also showed biliary “transdifferentiation” in the majority of intrasplenic injection sites of rats that received BDL but not in untreated recipients. PCR array analysis showed up-regulation of osteopontin (SPP1). Cell culture studies demonstrated increased Itgβ4, HNF1β, HNF6, Sox-9, and CK-19 mRNA expression in hepatocytes incubated with osteopontin, suggesting that this secreted protein promotes dedifferentiation of hepatocytes.

Conclusions

Our studies show that biliary fibrosis stimulates liver repopulation by ectopically transplanted hepatocytes and also stimulates hepatocyte transition towards a biliary epithelial phenotype. Words: 249

Keywords: Cell transplantation, bile duct ligation, hepatocyte dedifferentiation, hepatocyte transdifferentiation, osteopontin

INTRODUCTION

Chronic liver injury causes progressive fibrosis, characterized by accumulation of collagen and scar tissue, which leads to impaired hepatic function (1). Cirrhosis is the advanced stage of fibrosis in patients with chronic liver diseases, one of the major causes of death in the US, and liver transplantation is the only effective therapeutic option for end-stage disease (2, 3). Because of the increasing scarcity of donor organs (4), alternate therapies are critical. We have therefore focused on cell-based therapies to generate healthy new hepatic tissue mass in the diseased liver and delay the end stage. Successful application of these therapies would comprise an important clinical advance (5–8), but successful treatment will require strategies to promote engraftment and then expand the population of engrafted cells.

Elegant pioneering studies have shown that mature hepatocytes can repopulate more than 80% of the recipient liver (9–12). Such repopulation levels are achieved under circumstances of massive injury or inhibition of the proliferative capacity of host hepatocytes, which provides a selective growth advantage of transplanted cells. However, these studies represent extreme experimental conditions that might not accurately reflect clinical therapeutic scenarios. Nevertheless, liver repopulation after cell transplantation into the diseased liver environment must be evaluated in models that reproduce the most important features of human fibrosis.

Repopulation of the healthy liver requires stimulation of regeneration by partial hepatectomy (PH) to expand the transplanted cells (reviewed 6). However, we recently demonstrated that the injury inherent in severe liver disease can also drive repopulation by transplanted cells without additional treatment. In these experiments, we studied advanced cirrhosis induced by the hepatotoxin thioacetamide (TAA) and observed engrafted and repopulating cell clusters at 2 months after transplantation without the additional stimulus of PH (13).

In the present study, we investigated whether a less severe injury, biliary fibrosis following bile duct ligation (BDL), would drive repopulation by transplanted mature hepatocytes. As in our previous studies (6, 13), the experiments utilized transplantation of dipeptidyl-peptidase IV-positive (DPPIV+) donor cells into allogeneic DPPIV− host rats, but because BDL made the portal vein inaccessible, cell transplantation was carried out via intrasplenic injection. The experiments indeed demonstrated that biliary fibrosis induces hepatocyte repopulation, but surprisingly, they also showed striking and rapid transition of hepatocytes to cholangiocyte-like cells in both liver and spleen. This led us to explore how BDL directs two processes: hepatocyte repopulation and reprogramming of hepatocytes to induce phenotype conversion.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Animals and bile duct ligation

DPPIV+ F344 rats were purchased from Charles River. F344-Tg(EGFP) F455/Rrrc rats and DPPIV− F344 rats were originally obtained from the Rat Resource and Research Center of the University of Missouri-Columbia and used to derive male DPPIV+/GFP+ and DPPIV− F344 rats. For BDL, the common bile duct of DPPIV− F344 rats (2–3 months of age) was exposed and two ligatures were placed at the proximal and distal duct ends and tightened, followed by excision of the central part. All animal studies were conducted under protocols approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees of the University of Pittsburgh in accordance with NIH guidelines.

Isolation and purification of mature hepatocytes

Livers from DPPIV+ F344 or F344-Tg(EGFP) F455/Rrrc rats were perfused with 5000 U/100 mL collagenase (Sigma), excised, minced and suspended in Hank’s balanced salt solution (HBSS). Cell suspension was filtered through a 70-μm nylon mesh and centrifuged for 2 minutes at 50 × g at 4°C. The pellet was washed 3 times with Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium (DMEM) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), re-suspended in DMEM/10% FBS, mixed with an equal volume of Percoll (GE Healthcare Bio-Sciences) solution (containing Percoll/10x HBSS, 9:1), and centrifuged for 10 minutes at 50 × g at 4°C. Cell viability of purified hepatocytes was >95%.

Cell culture

Purified hepatocytes (2 × 105) were plated on collagen-coated 6-well plates and incubated in serum-free Minimum Essential medium (MEM) containing 500 ng/mL insulin (Sigma). After ~2 hours, cells were incubated with or without osteopontin (R&D Systems), chenodeoxycholate, ursodeoxycholate, or taurocholate (Sigma) at various concentrations for 4 days. Triplicate cultures were pooled after cell lysis using Trizol reagent (Life Technologies), followed by total RNA isolation and subsequent qRT-PCR analysis.

Cell transplantation and liver repopulation

Purified hepatocytes (~1 × 107) were transplanted without PH into the spleen of DPPIV− F344 rats at 2 or 4 weeks after BDL or age-matched non-treated normal recipients. Rats were sacrificed at different times following cell transplantation and liver replacement was determined by enzyme histochemistry for DPPIV, as described previously (14). For engraftment studies, transplanted hepatocytes were detected by immunohistochemistry for enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP).

Histochemistry

Sirius Red, Masson’s trichrome, and hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining of paraffin-embedded liver sections was performed using standard techniques. Enzyme histochemistry for γ–glutamyl transpeptidase (GGT) was determined as described previously (15).

Laser capture microscopy

Cryosections from liver tissues at 1 month after BDL and non-treated normal livers (n = 3/3 rats) were stained by Cresyl Violet (Ambion) to visualize the fibrotic septa and surrounding parenchymal tissue regions, which was followed by laser capture microdissection (LCM) using the LMD6500 Laser Microdissection System (Leica Microsystems). By collecting laser-captured liver tissue samples from 5–10 fibrotic septa regions and equally sized regions from surrounding parenchyma of each rat, we isolated 50–150 ng RNA/sample using the PicoPure RNA isolation kit (Life Technology). LCM-derived RNA had a very high integrity without DNA contamination (RIN numbers were between 8.0 and 9.3), as determined using the 2100 Bioanalyzer system (Agilent Technologies). RNA was amplified using the Ovation PicoSL WTA System V2 (NuGEN Technologies). After one round of amplification, at least 7 μg complementary DNA/sample was obtained, subsequently pooled for each group and used for RT-PCR, qRT-PCR analysis for selected genes or PCR array analysis.

RT-PCR, qRT-PCR, and qRT-PCR array analysis

Total RNA was extracted from cell isolates or snap-frozen liver tissue using Trizol reagent (Life Technologies) and treated with DNAse I (NEB), followed by a cleanup step using RNeasy Plus Mini/Micro Kit (Qiagen).

For RT-PCR analyses, RNA was reverse transcribed using Verso cDNA Synthesis Kit (Thermo Scientific). A complete list of primers with the number of cycles is shown in Supplemental Table 1. cDNA was amplified by Choice-Taq DNA Polymerase (Denville Scientific) for 10 minutes at 95°C, followed by 25 to 35 cycles at 94°C for 30 seconds, 60°C for 20 seconds, 72°C for 60 seconds and a final cycle at 72°C for 7 minutes.

qRT-PCR was performed with at least two independent experiments, each with duplicate assays, using the StepOnePlus Real Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems). All samples were analyzed using Power SYBR Green Master Mix (Applied Biosystems). mRNA abundance was determined by normalization of the data to the expression levels of glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) mRNA. RT-PCR data were analyzed using the 2−ΔΔCt (ddCt) method. A complete list of primers is shown in Supplemental Table 1.

Rat Growth Factors RT2 Profiler™ PCR arrays (SA Biosciences) containing 84 genes encoding specific growth factors (SA Biosciences; www.sabiosciences.com) were used to determine mRNA expression levels in laser-captured liver tissue samples. A complete list of the genes, as well as housekeeping genes/controls can be found in www.sabiosciences.com. cDNA synthesis, qRT-PCR, and data analysis were performed according to the manufacture’s instructions. For data analysis, the SA Bioscience web-based PCR Array Data Analysis tool was used (www.sabiosciences.com/pcrarraydataanalysis.php).

Quantification of dedifferentiated hepatocytes

To determine the % of bile ductules derived from transplanted DPPIV+ hepatocytes, 3 liver sections (representing 3 different lobes) from each rat (n = 3) were analyzed for the presence of bile duct-like structures in DPPIV+ cell clusters.

Additional information can be found in the Supplemental Materials and Methods.

RESULTS

Characterization of hepatic fibrosis after bile duct ligation

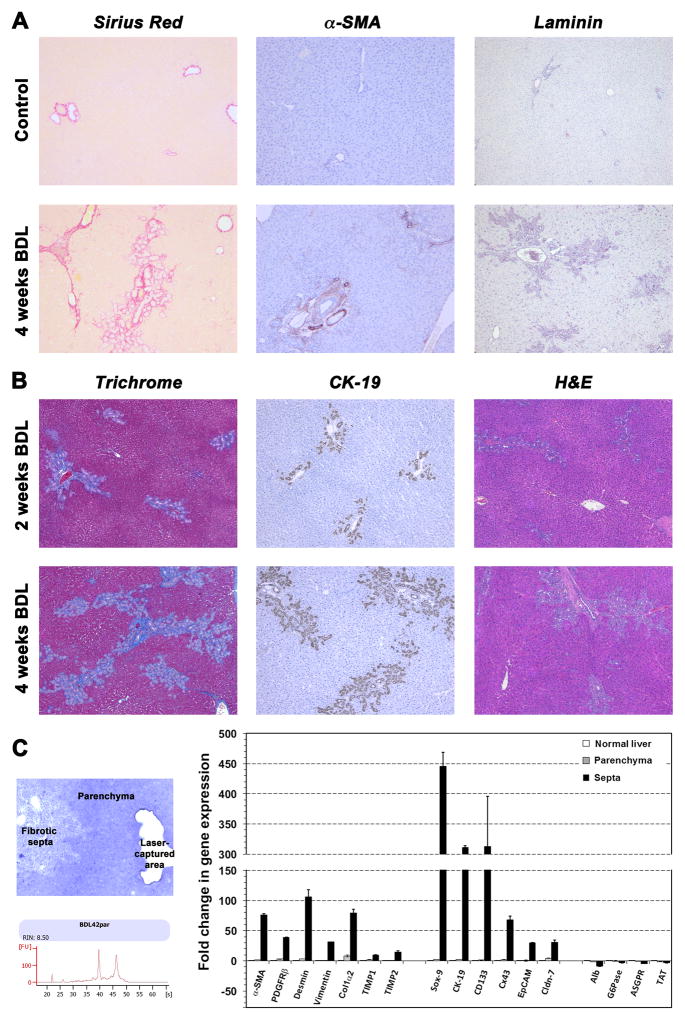

To directly address the influence of a mild injury on the engraftment and repopulation of transplanted hepatocytes in a diseased liver environment, we induced progressive portal tract fibrosis by common bile duct ligation in DPPIV− F344 rats. Changes were assessed at 2 and 4 weeks after BDL, using Sirius Red (Figure 1A, left panels), Masson’s trichrome (Figure 1B, left panels), and H&E staining (Figure 1B, right panels). Immunohistochemistry for CK-19 showed strong cholangiocyte proliferation after BDL (Figure 1B, middle panels). Compared to normal liver tissue, increased numbers of α-SMA+ (Figure 1A, middle panels) and laminin+ cells were detected at 4 weeks after BDL (Figure 1A, right panels), indicating activation of fibroblasts and stellate cells (additional immunohistochemical analyses can be found in Supplemental Figure 1).

Fig. 1. Liver fibrosis in bile duct-ligated rats.

Biliary fibrosis was induced by BDL in DPPIV− F344 rats. Pathologic changes at 2/4 weeks after BDL were determined using histochemical and immunohistochemical techniques (A,B). Original magnification, ×50. (C) RNA extracts from laser-captured liver regions (fibrotic septa, surrounding parenchyma) at 1 month after BDL were analyzed, using pooled RNA samples. LCM-derived RNA had high integrity without DNA contamination (one sample is shown). Mean ± SEM values of two replicate PCR analyses are expressed as fold differences in gene expression compared to age-matched normal control rats, set at a value of 1.

To determine the expression levels of fibrosis-related genes, qRT-PCR analyses were performed on laser-captured liver tissue samples at 1 month after BDL (Figure 1C). We observed elevated expression of α-SMA, platelet-derived growth factor receptor beta (PDGFRβ), desmin, vimentin, collagen 1α2 (Col1α2), and tissue inhibitor metalloproteinase-1 and -2 (TIMP1, TIMP2) messenger RNA (mRNA). Up-regulation of these genes clearly reflects activation of stellate cells and ongoing fibrogenesis. Over-expression of Sox-9, CK-19, prominin-1 (CD133), connexin43 (Cx43), EpCAM, and Cldn-7 indicated progressive bile duct proliferation after BDL. Furthermore, the liver weight in animals that underwent BDL was increased 1.29 and 1.78 fold at 2 weeks and 4 weeks, respectively, compared to control rats (n = 8/5).

Engraftment and repopulation of the liver with biliary fibrosis

Purified hepatocytes were infused into the spleen of BDL rats to test the feasibility of hepatocyte transplantation in rats with ongoing biliary fibrosis. We used two different detection methods to follow the fate of donor cells after transplantation into DPPIV− rats. GFP+ hepatocytes were used for studies of engraftment, since GFP is expressed throughout the cell cytoplasm, and is, therefore, particularly useful to visualize single cells early after transplantation. DPPIV was used as a marker enzyme in studies of repopulation in DPPIV− rats. Infusions consisted of 1 × 107 highly purified hepatocytes, without detection of Sox-9, CK-19, Cx43, EpCAM, or CK-7, which would indicate biliary cell contamination (Supplemental Figure 2; see also Figure 6A & B, below).

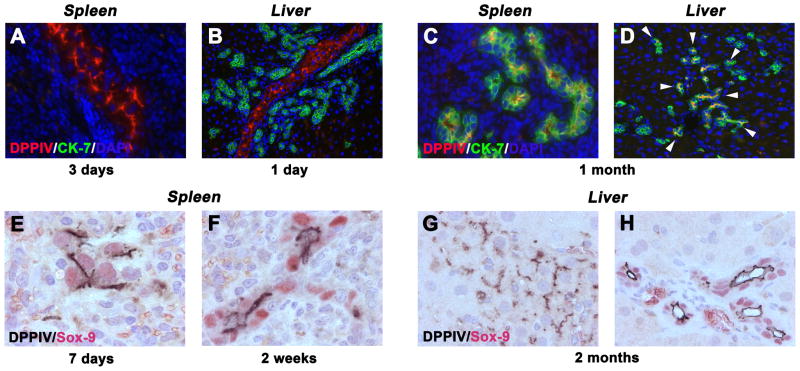

Fig. 6. Timecource of phenotype conversion of donor-derived hepatocytes in recipient rats.

DPPIV+ hepatocytes were intrasplenically transplanted into DPPIV− F344 rats with BDL. (A–D) Simultaneous immunohistochemistry for DPPIV and CK-7. Note the presence of DPPIV+ donor cells co-expressing CK-7 (see arrow heads) in close proximity to expanding host bile ducts. (E–H) Double-immunohistochemistry for DPPIV/Sox-9. Original magnification, ×400 (A,C), ×200 (B,D), ×1000 (E,F), ×640 (G,H).

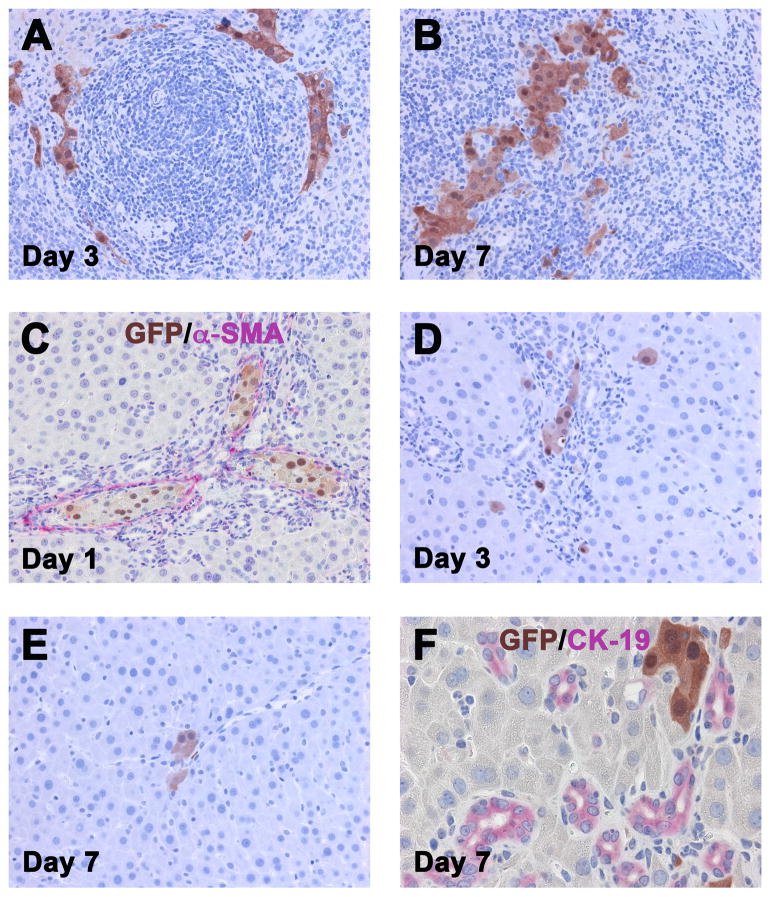

In engraftment studies, tissue samples were analyzed at day 1, 3 and 7 after intrasplenic hepatocyte transplantation (n = 10). At day 1 after cell infusion, pools of unattached deteriorating GFP+ cells (which disappeared on day 3) and scattered viable GFP+ hepatocytes were observed in the red pulp of the recipient spleen (data not shown). These assembled into multicellular groups day 3 (Figure 2A) and increased in size at day 7 (Figure 2B).

Fig. 2. Engraftment of mature GFP+ hepatocytes transplanted into the spleen of DPPIV− F344 rats at 1 month after BDL.

Immunohistochemistry for GFP showing engraftment of highly purified GFP+ hepatocytes (~1 × 107 cells) in the injection site of the spleen (A, B) and after migration into the liver (C–F). Rats were sacrificed at 1, 3 or 7 days after cell infusion. Original magnification, ×200 (A–E), ×400 (F).

Recipient livers at day 1 showed multicellular groups of GFP+ hepatocytes in portal vessels, surrounded by extensive zones of expanding host bile ducts (Figure 2C). Scattered GFP+ hepatocytes were also observed at the periphery of the expanded portal areas, in some cases merged with GFP− hepatocyte cords outside of the limiting plate. Reduced intravascular groups of donor-derived cells were observed at day 3; however, an increased number of single GFP+ hepatocytes were within hepatic plates that were not adjacent to portal areas (Figure 2D). By day 7, some of the parenchymal foci became multicellular (Figure 2E & F), demonstrating early hepatic tissue replacement in the bile duct-ligated recipient liver.

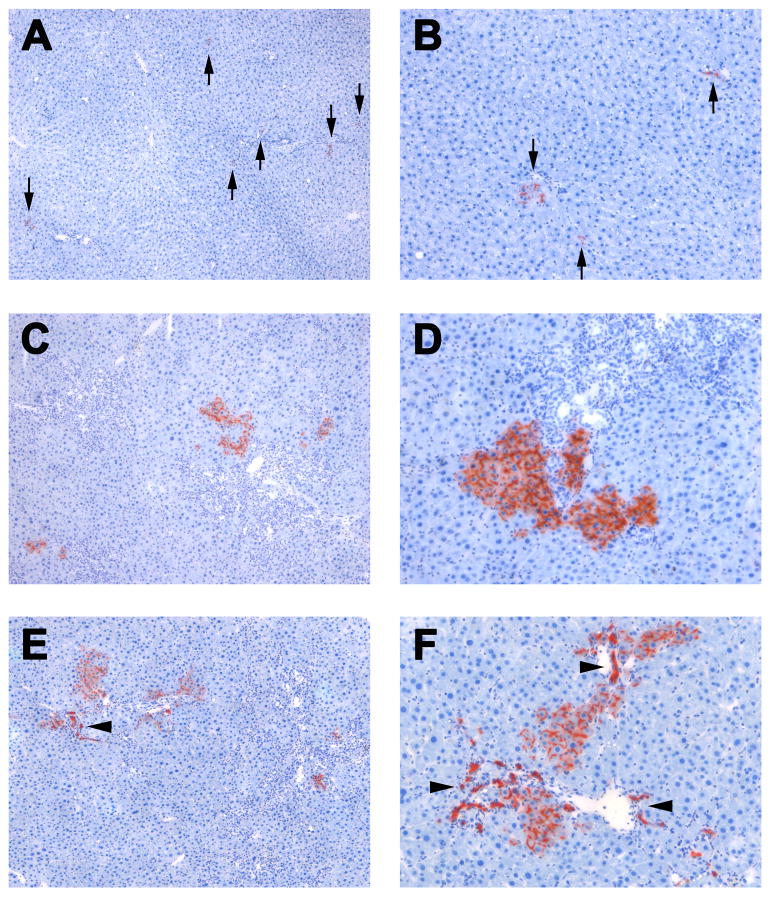

In repopulation studies, DPPIV+ adult hepatocytes were transplanted into the spleens of DPPIV− rats w/o BDL (n = 7) (Figure 3A & B), or at 2/4 weeks after BDL (n = 15) (Figure 3C–F). Ectopic transplanted hepatocytes migrated and engrafted into both liver microenvironments. Only single DPPIV+ hepatocytes or very small hepatocytic cell groups (up to 4 cells) were detected in the non-injured recipient liver (Figure 3A & B). However, expansion and cluster formation of transplanted hepatocytes was only observed in recipient rats with ongoing biliary fibrosis during the 2-month observation time. Donor-derived hepatocytes incorporated into the host liver parenchyma and generated DPPIV+ cell clusters of different sizes, which were mainly located in close proximity to portal areas with expanding host bile ducts (Figure 3C–F). Importantly, 9.88 ± 3.69 % of transplanted DPPIV+ cell clusters contained donor-derived DPPIV+ bile ductules (Figure 3E & F). This contrasts with our previous study of repopulation in TAA-induced cirrhosis, where engrafted hepatocyte-derived clusters were entirely hepatocytic.

Fig. 3. Tissue replacement in the recipient liver by donor hepatocytes.

Highly purified DPPIV+ hepatocytes (~1×107) were transplanted into the spleen of DPPIV− F344 rats w/o (A,B) or with BDL (C–F). After migration and engraftment, only single DPPIV+ cells or very small cell groups were found in normal recipient livers (see arrows in A,B). In contrast, repopulation of transplanted hepatocytes was observed in host livers of BDL recipient rats. Donor-derived hepatocytes incorporated in the host parenchyma and generated DPPIV+ cell clusters (C–F). Arrowheads highlight donor-derived bile ducts. Examples at 2 months after transplantation are shown (A–F). Original magnification, ×50 (A,C,E), ×100 (B,D,F).

Phenotype transition of mature hepatocytes into bile duct-like cells

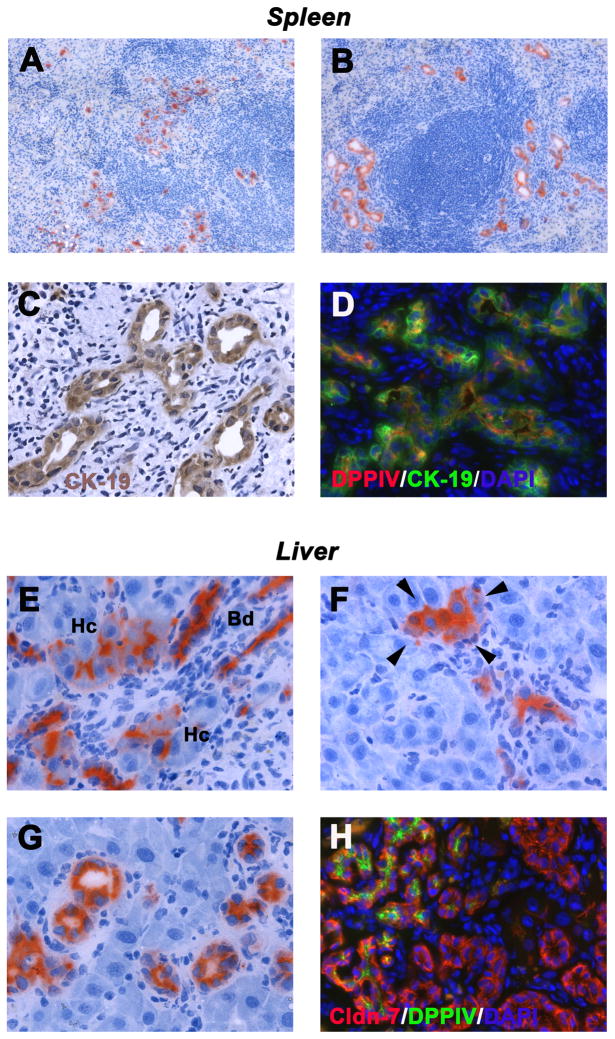

In normal recipient rats without BDL, accumulation of DPPIV+ hepatocytes was observed in the injection site of the spleen and only single or very small epithelial cell groups without lumens were seen 1 month after hepatocyte infusion (Figure 4A). In contrast, the vast majority of hepatocytes engrafted in the host spleen of BDL rats formed ducts with central lumens that resembled bile ducts at 4 weeks after cell infusion (representing >90% of DPPIV+ cells; see Figure 4B). Immunohistochemical analyses for CK-19 was strongly positive, a characteristic of bile ducts (Figure 4C), confirmed by simultaneous immunohistochemistry for DPPIV and CK-19 (Figure 4D).

Fig. 4. Evidence of biliary epithelial differentiation of transplanted hepatocytes.

DPPIV+ hepatocytes were transplanted into the spleen of DPPIV− F344 rats w/o (A) or with BDL (B–H). DPPIV+ cells are shown in the injection site of recipient spleens of normal (A) and BDL rats (B). Transplanted hepatocytes expressed CK-19 (C,D). DPPIV expression pattern of engrafted hepatocytes in livers of BDL rats (E–G). Note the presence of hepatocyte-like cells expressing DPPIV in the cytoplasm (see arrow heads; F). DPPIV+ hepatocytes co-expressed claudin-7 (H). Panels show transplanted cells at 1 month (A–F) and 2 months (G,H) after infusion. Original magnification, ×100 (A,B), ×400 (C–H).

In the BDL liver at 1 month, transplanted hepatocytes had grown into both hepatocytic and ductular cell groups. Normally, hepatocytes express DPPIV in a bile canalicular pattern, whereas cholangiocytes express DPPIV in the cytoplasm (both expression patterns are shown in Figure 4E). The presence of hepatocyte-like cells, which expressed DPPIV in the cytoplasm near the luminal surface (see arrow heads in Figure 4F) and large DPPIV+ bile duct-like structures at 2 months (Figure 4G), suggests ongoing phenotype conversion of hepatocytes. Double immunohistochemistry clearly showed that donor-derived DPPIV+ cells co-expressed bile duct-specific markers, e.g., claudin-7 in contrast to morphologically identical host-derived ducts (Figure 4H).

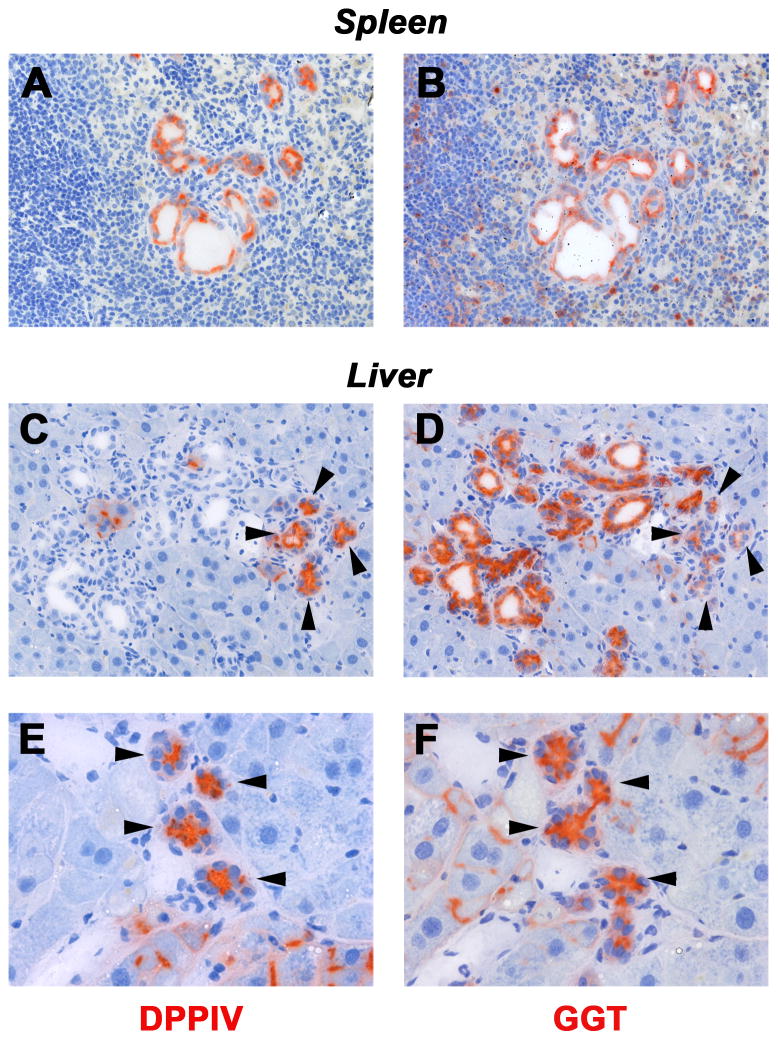

To verify these data, we examined additional cell type-specific markers. GGT, normally expressed in biliary cells (15), was uniformly expressed in donor-derived DPPIV+ cell groups in the recipient spleen (compare Figure 5A & B). In the liver (Figure 5C–F), donor-derived DPPIV+ cells with biliary structure-like morphology were integrated with host bile ducts at 1 and 2 months after cell infusion. Both host and donor cells were GGT+; although in some cases, GGT expression was weaker in donor-derived cells (Figure 5D). Furthermore, CK-7, exclusively expressed in bile duct cells, was not observed in transplanted DPPIV+ hepatocytes within 3 days after cell infusion (Figure 6A & B). However, transplanted donor cells exhibiting biliary cell morphology co-expressed CK-7 in the recipient spleen and liver at 1 month (Figure 6C & D). The spleen shows sequential phenotype conversion of cords of engrafted hepatocytes into ductal structures with central lumens and biliary gene expression. In contrast, the liver shows de novo appearance of DPPIV+ bile duct clusters adjacent to some hepatocyte clusters, without an obvious transition. These are frequently integrated with clusters of morphologically identical DPPIV− bile ducts (Figure panels 4H, 5C, 6D).

Fig. 5. γ–Glutamyl transpeptidase (GGT) expression in donor-derived cells in recipient rats.

DPPIV+ hepatocytes were transplanted into the spleen of DPPIV− F344 rats with BDL. The panels compare DPPIV and GGT staining in serial sections of recipient spleen at 1 month and liver at 2 months after cell infusion. Note the presence of bile duct-like cells expressing DPPIV and GGT (see arrow heads). Host DPPIV− hepatocytes can also express GGT with a pattern of weak canalicular staining (F), a phenomenon observed after hepatocyte transplantation (see ref. 15). Original magnification, ×200 (A–D), ×400 (E,F).

To determine the time course of phenotype conversion, recipient spleens of BDL rats at 1, 2 and 3 weeks (n = 11) after hepatocyte transplantation were analyzed for the expression of Sox-9, which is the earliest marker in biliary development (16) and not expressed in hepatocytes. As shown in Figure 6E, Sox-9 was already expressed in DPPIV+ hepatocytes at day 7 after cell infusion, although they still retained DPPIV+ canaliculi. By 2 weeks, these had transitioned to bile duct-like structures with smaller nuclei positive for Sox-9 within cells arranged around a central DPPIV+ lumen (Figure 6F), and phenotype conversion continued, thereafter (data not shown). In the liver, engrafted and expanded donor hepatocyte clusters were Sox-9− (Figure 6G). However, hepatocyte-derived ductules expressed Sox-9 (Figure 6H).

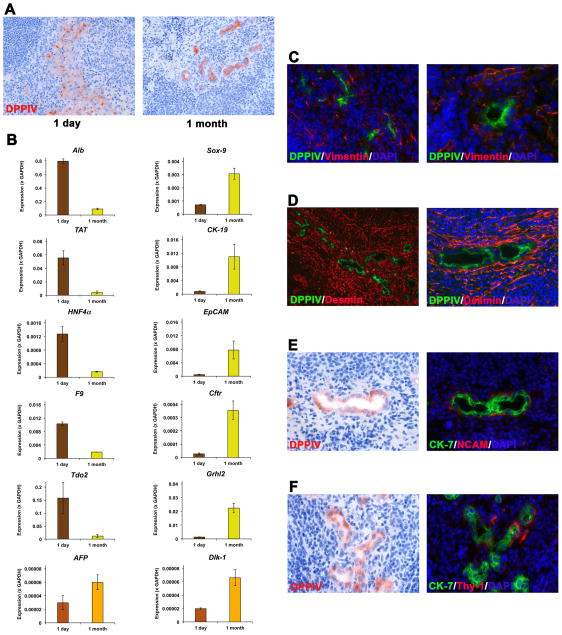

Previously, Tarlow et al. demonstrated that mature hepatocytes can undergo reversible ductular “metaplasia”, a process characterized by induction of progenitor genes in hepatocytes (17). Therefore, to determine whether hepatocyte-derived bile duct-like structures resembles either the “stable” cholangiocyte or a hepatocyte-derived progenitor phenotype, we analyzed tissue samples isolated from spleen regions at the injection site of hepatocytes at different time points after cell infusion with a panel of epithelial and mesenchymal markers that discriminate of the two phenotypes. Enzyme histochemistry for DPPIV confirmed the presence of donor-derived cells in separated spleen samples, which exhibited a hepatocytic phenotype at day 1 but bile duct-like cell morphology 1 month thereafter (Figure 7A). qRT-PCR analyses determined that hepatocyte-specific genes (e.g., Alb, TAT, Tdo2) were predominantly expressed early after hepatocyte infusion, but bile duct-related genes (e.g., CK-19, EpCAM, Crhl2) predominated 1 month later (Figure 7B). Importantly, levels of the progenitor markers AFP and Dlk-1, which were detected at 1 month after cell infusion, cannot be considered as biologically relevant, since mRNA expression values remained near zero (Figure 7B). Moreover, immunohistochemical analyses for vimentin, desmin, NCAM and Thy-1 showed no evidence of mesenchymal marker expression in donor-derived bile duct-like cells (Figure 7C–F; compare with Supplemental Figure 1, which shows the pattern of mesenchymal markers associated with intrahepatic bile duct proliferation). The newly formed ducts lacked the markers that characterized ductular “metaplasia” and had a phenotype like mature cholangiocytes.

Fig. 7. Direct phenotype transition of transplanted hepatocytes into bile duct-like cells in recipient spleen.

(A) DPPIV staining compares morphology of transplanted hepatocytes engrafted at the splenic injection. (B) RNA extracts derived from the injection site at 1 day and 1 month after hepatocyte infusion into BDL rats (n=3/3) were pooled and analyzed by qRT-PCR. Mean ± SEM values of two replicate analyses for selected genes are shown. (C–F) At 1 month, mesenchymal markers were apparent in the stroma but not in donor-derived cells. Panels in E and F compare stainings in consecutive sections. Original magnification, ×200 (A;D,left panel), ×400 (C, left;D,right;E;F), ×640 (C; right).

Growth factors and modeling of phenotype conversion in cultured hepatocytes

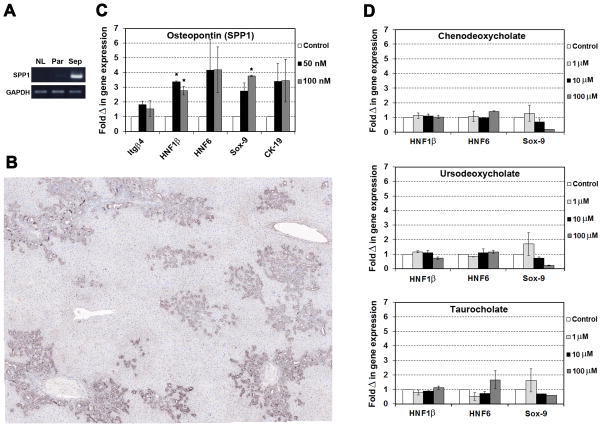

Because we observed dedifferentiation of mature hepatocytes, we analyzed a growth factor and cytokine PCR array to identify soluble signal factors that could be involved in this process and confirmed changes in gene expression with subsequent qRT-PCR analyses (Supplemental Table 2). Marked up-regulation of fibroblast growth factor (FGF)18, interleukin (IL)-6, and secreted phosphoprotein 1 (SPP1, osteopontin) mRNA was observed in laser-captured fibrotic portal regions compared to surrounding parenchyma and age-matched controls (Supplemental Table 2).

To directly examine the effect of cytokines on hepatocytes, we then performed cell culture studies. However, it has been demonstrated in vitro that IL-6 reverses biliary “transdifferentiation” of cultured hepatocytes (18), so we did not perform experiments with this cytokine. Moreover, a pilot experiment with mature hepatocytes incubated with FGF18 showed no effect on mRNA expression of genes that are involved in the development of bile ducts (data not shown) and published studies have shown that this agent is a hepatocyte mitogen without obvious phenotypic effects (19). We therefore focused on osteopontin, which is highly expressed in biliary epithelial cells after BDL (Figure 8A & B; Supplemental Figure 3), as a potential signal that regulates phenotype transition. After attaching highly purified mature hepatocytes for 2 hours, cells were cultured in control medium or supplemented with 50 or 100 nM osteopontin (20) for 4 days. As demonstrated in Figure 8C, qRT-PCR analyses of selected genes showed that osteopontin clearly stimulated the mRNA expression of genes involved in the development of bile ducts (e.g., hepatocyte nuclear factor 1β [HNF1β], HNF6, and Sox-9).

Fig. 8. Detection of osteopontin (SPP1) in fibrotic liver and its effect on hepatocytes.

(A) RNA extracts from laser-captured liver regions (Sep, fibrotic septa; Par, surrounding parenchyma) at 1 month after BDL compared to normal livers (NL) were analyzed, using pooled RNA samples (3 rats, each group). One representative analysis of 2 independent RT-PCR analyses is shown. (B) Immunohistochemistry for osteopontin 4 weeks after BDL. Image contains 36 merged adjacent microscopic fields (×200). Normal liver is shown in Supplemental Figure 3. (C,D) Hepatocytes were cultured in triplicates with osteopontin or bile acids for 4 days (n=2). Two independent RT-PCR analyses were performed for each experiment. Mean ± SEM values are expressed as fold changes of RNA expression with respect to cells cultured without osteopontin/bile acids. (*P < 0.05; Student’s t test)

Finally, our finding of enhanced dedifferentiation of hepatocytes in the spleen also raises the issue of the nature of the signals involved. Such signals must be transmitted to the spleen via the blood. Osteopontin is clearly a candidate, but bile duct ligation also results in elevation of peripheral blood bile acids. We therefore performed additional in vitro studies, in which mature hepatocytes were treated with up to 100 μM chenodeoxycholate, ursodeoxycholate, or taurocholate (21). However, these experiments showed no evidence that bile acids stimulate biliary gene expression (Figure 8D).

DISCUSSION

Cell-based therapies (e.g., hepatocytes, stem cells) hold great promise for the treatment of patients with endstage liver diseases. Several rodent models of human hepatic fibrosis (22) are available to study novel cell transplantation strategies in fibrotic recipient rats. In a fibrotic/cirrhotic liver environment induced by TAA, we demonstrated that hepatic cells can effectively repopulate severely injured liver (13). The aim of the present study was to investigate the influence of a milder injury on the engraftment and tissue replacement of transplanted mature hepatocytes. The mild injury was secondary biliary fibrosis induced by BDL, which has a strong effect on bile ducts and their surrounding stroma and a smaller effect on hepatocytes. Obstruction of the common bile duct induces portal inflammation and bile duct proliferation and can lead to biliary cirrhosis (23). We established biliary fibrosis at 4 weeks after BDL in mutant DPPIV− F344 rats (24), indicated by accumulation of collagen (25, 26). Increased levels of α-SMA, PDGFRβ, Col1α2, TIMP1, and TIMP2 mRNA in laser-captured material demonstrated activation of stellate cells and ongoing fibrogenesis (1, 26). Furthermore, strong up-regulation of bile duct-specific marker genes (e.g., Sox-9, CK-19, Cx43, and EpCAM) clearly reflects cholangiocyte proliferation caused by biliary obstruction. Severe hepatocyte damage, which is achieved after chronic treatment with TAA in DPPIV− F344 rats (13), was not observed in BDL rats. Using a model of secondary biliary fibrosis induced by common BDL, we have made three major observations. First, ectopically transplanted mature hepatocytes migrate to the diseased liver and repopulate by forming cell clusters without the additional stimulus provided by liver regeneration. Second, fully differentiated hepatocytes are capable of phenotype transition to bile duct-like structures in a liver environment with ongoing biliary fibrosis. Third, osteopontin, which is strongly overexpressed in bile duct-ligated rat liver, stimulates hepatocytes to express biliary markers, and suggests a mechanism for this phenotype transition.

Intraportal infusion is the most common route for hepatocyte transplantation in clinical settings, except in patients with liver cirrhosis (8). Similary, in our experimental experience, most successful liver repopulation was achieved after cell infusion into the portal vein of partial hepatectomized rats, even in fibrotic/cirrhotic recipient rats (13). However, this approach is impractical several weeks after bile duct ligation. Hepatocytes have been transplanted at different ectopic injection sites, e.g., dorsal fascia (27) or spleen (28), and approximately 50% of the infused hepatocytes translocate to the liver (29). The present study showed that intrasplenic infused hepatocytes, which are in a quiescent state with a slow cell turnover, re-enter the cell cycle and proliferate after migration and engraftment in a liver environment of secondary biliary fibrosis. Our studies also show that ongoing biliary fibrosis stimulates repopulation by mature hepatocytes, although to a lesser extent than the injury of a severely injured fibrotic liver (13). Therefore, future research strategies could enable transplanted donor cells to out-compete host hepatocytes and more extensively repopulate the diseased environment (30). A selective growth advantage of donor cells can also be achieved by infusion of highly proliferative cells. To date, fetal liver stem/progenitor cells are the most efficient cell source to repopulate the near-normal liver environment after differentiation into hepatocytes and bile duct cells (reviewed 6). Furthermore, to enhance the repopulation potential of transplanted cells as demonstrated in rodent models (11, 12), preconditioning (e.g., partial resection or irradiation) of the recipient liver represents a promising approach in human hepatocyte transplantation (8).

Our strategy for identifying transplanted cells via DPPIV staining provided clear documentation of hepatocyte phenotype transition to bile duct-like cells in both liver and spleen. These provide in vivo confirmation of earlier studies that demonstrated hepatocyte transformation in organoid cultures (31, 32) and in retrorsine-treated chimeric recipient rats subjected to the biliary toxin methylene dianiline (DAPM) (33, 34). Earlier evidence that hepatocytes are capable of undergoing phenotypic transition to cholangiocytic cells was shown in the rat spleen, after hepatocytes were intrasplenically infused and the left branch of the portal vein was ligated (35, 36), and in mouse liver injury models, using genetic lineage tracing (37, 38). Furthermore, Grompe and co-workers demonstrated that mouse and human hepatocytes are capable of undergoing ductular “metaplasia” and contribute to the progenitor cell pool under chronic injury, a process that is reversible during recovery (17). However, our studies clearly showed that transplanted mature hepatocytes dedifferentiated into bile duct-like cells expressing the cholangiocytic markers CK-7 and CK-19, which are not expressed in “metaplastic” cells (17). Furthermore, we did not observe expression of mesenchymal markers (e.g., vimentin and NCAM), which are induced in biliary-like progenitor cells (17), as well as convincing evidence of hepatocyte transition into a unique progenitor cell state (AFP+, Dlk-1+) that might be reversed following liver recovery. Taken together, our studies suggest that transplanted hepatocytes undergo a direct phenotype conversion into biliary epithelial-(like) cells.

We have exclusively used purified cell isolates (see Supplemental Figure 2) to avoid contaminating biliary epithelial and hepatic progenitor cells in hepatocyte fractions (34, 35). Although at a lower frequency compared to the additional exposure to DAPM (31), our study demonstrates the phenotypic transition of some ectopically infused hepatocytes after engraftment in a liver environment with ongoing biliary fibrosis. Phenotype conversion also occurred in hepatocytes that remained in the spleen, which provided a clear view of the sequential changes because the transplanted cells were independent of endogenous liver and bile ducts.

To identify soluble factors, which are involved in hepatocyte dedifferentiation (a phenomena that was not observed in TAA-treated recipient rats), we performed PCR array/qRT-PCR analyses in laser-captured liver tissue samples of bile duct-ligated rats and detected highly elevated osteopontin mRNA levels in fibrotic portal regions. In addition, compared to laser-captured liver tissue regions of TAA-induced fibrotic liver, qRT-PCR analyses in rats after BDL showed much higher up-regulation of osteopontin mRNA, as well as of Sox-9 (see Supplemental Table 3). Osteopontin is a pleiotropic cytokine, which is detected in a variety of liver cells (e.g., bile duct cells, stellate cells, macrophages, and hepatocytes) and mediates diverse cellular functions (39). Osteopontin is Hedgehog-regulated and promotes hepatic fibrosis (40). Pritchett et al. (41) demonstrated that Sox-9 (downstream of Hedgehog signaling) is responsible for osteopontin production and suggested that osteopontin is a major regulator of hepatic fibrosis. Since osteopontin is highly expressed and can be secreted by bile duct cells after BDL, we cultured purified hepatocytes with or without osteopontin and studied the expression pattern of biliary epithelial cell markers to determine the potential role for osteopontin in hepatocyte dedifferentiation. Increased expression of the liver-specific genes/transcription factors Itgβ4, CK-19, HNF1β, Sox9, and HNF6, which are required in bile duct development (16, 42–44), suggest a new function of osteopontin. However, additional studies to provide a better understanding of the basic requirements and the mechanism of osteopontin-induced phenotype conversion are necessary.

In summary, our studies show that ongoing biliary fibrosis creates a hepatic tissue environment in which ectopically transplanted mature hepatocytes engraft and replace tissue mass. They also suggest a model for studying transition of hepatocytes to biliary epithelium and propose that osteopontin promotes hepatocyte conversion to cholangiocytes.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dr. George Michalopoulos (Division of Pathology, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA) for his helpful discussions and critical reading of the article.

Financial support: Supported by NIH grant R01 DK090325 (to M.O.).

Abbreviations

- PH

partial hepatectomy

- TAA

thioacetamide

- BDL

bile duct ligation

- DPPIV

dipeptidyl-peptidase IV

- HBSS

Hank’s balanced salt solution

- DMEM

Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium

- FBS

fetal bovine serum

- EGFP

enhanced green fluorescent protein

- H&E

hematoxylin and eosin

- GGT

γ–glutamyl transpeptidase

- IHC

immunohistochemistry

- α-SMA

alpha-smooth muscle actin

- CK-19

cytokeratin-19

- Sox-9

SRY-related high-mobility group box 9

- Cldn-7

claudin-7

- EpCAM

epithelial cell adhesion molecule

- LCM

laser capture microdissection

- PDGFRβ

platelet-derived growth factor receptor beta

- Col1α2

collagen 1α2

- TIMP1

tissue inhibitor metalloproteinase-1

- Cx43

connexin43

- FGF

fibroblast growth factor

- IL

interleukin

- SPP1

secreted phosphoprotein 1

- HNF

hepatocyte nuclear factor

- Itg4β

integrin beta-4

Footnotes

Conflict of interests: The authors indicate no potential conflicts of interest.

Author’s contributions: M.I.Y. carried out experiments and analyzed data. J.L. performed histological sub-classification of fibrosis and tissue analyses. M.O. designed the studies, performed experiments, analyzed data and wrote the manuscript. All authors read and commented on the manuscript.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

Author names in bold designate shared co-first/second authorship.

- 1.Hernandez-Gea V, Friedman SL. Pathogenesis of liver fibrosis. Annu Rev Pathol. 2011;6:425–456. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pathol-011110-130246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Murphy SL, Xu J, Kochanek KD. Deaths: final data for 2010. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2013;61:1–117. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cárdenas A, Ginès P. Management of patients with cirrhosis awaiting liver transplantation. Gut. 2011;60:412–421. doi: 10.1136/gut.2009.179937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kim WR, Lake JR, Smith JM, Skeans MA, Schladt DP, Edwards EB, et al. OPTN/SRTR 2013 Annual Data Report: liver. Am J Transplant. 2015;15(Suppl 2):1–28. doi: 10.1111/ajt.13197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Struecker B, Raschzok N, Sauer IM. Liver support strategies: cutting-edge technologies. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;11:166–176. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2013.204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Oertel M. Fetal liver cell transplantation as a potential alternative to whole liver transplantation? J Gastroenterol. 2011;46:953–965. doi: 10.1007/s00535-011-0427-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Huebert RC, Rakela J. Cellular therapy for liver disease. Mayo Clin Proc. 2014;89:414–424. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2013.10.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gramignoli R, Vosough M, Kannisto K, Srinivasan RC, Strom SC. Clinical hepatocyte transplantation: practical limits and possible solutions. Eur Surg Res. 2015;54:162–177. doi: 10.1159/000369552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rhim JA, Sandgren EP, Degen JL, Palmiter RD, Brinster RL. Replacement of diseased mouse liver by hepatic cell transplantation. Science. 1994;263:1149–1152. doi: 10.1126/science.8108734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Overturf K, Al-Dhalimy M, Tanguay R, Brantly M, Ou CN, Finegold M, et al. Hepatocytes corrected by gene therapy are selected in vivo in a murine model of hereditary tyrosinaemia type I. Nat Genet. 1996;12:266–273. doi: 10.1038/ng0396-266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Laconi E, Oren R, Mukhopadhyay DK, Hurston E, Laconi S, Pani P, et al. Long-term, near-total liver replacement by transplantation of isolated hepatocytes in rats treated with retrorsine. Am J Pathol. 1998;153:319–329. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)65574-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guha C, Sharma A, Gupta S, Alfieri A, Gorla GR, Gagandeep S, et al. Amelioration of radiation-induced liver damage in partially hepatectomized rats by hepatocyte transplantation. Cancer Res. 1999;59:5871–5874. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yovchev MI, Xue Y, Shafritz DA, Locker J, Oertel M. Repopulation of the fibrotic/cirrhotic rat liver by transplanted hepatic stem/progenitor cells and mature hepatocytes. Hepatology. 2014;59:284–295. doi: 10.1002/hep.26615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yovchev MI, Dabeva MD, Oertel M. Isolation, characterization, and transplantation of adult liver progenitor cells. Methods Mol Biol. 2013;976:37–51. doi: 10.1007/978-1-62703-317-6_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gupta S, Rajvanshi P, Malhi H, Slehria S, Sokhi RP, Vasa SR, et al. Cell transplantation causes loss of gap junctions and activates GGT expression permanently in host liver. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2000;279:G815–826. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.2000.279.4.G815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Antoniou A, Raynaud P, Cordi S, Zong Y, Tronche F, Stanger BZ, et al. Intrahepatic bile ducts develop according to a new mode of tubulogenesis regulated by the transcription factor SOX9. Gastroenterology. 2009;136:2325–2333. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.02.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tarlow BD, Pelz C, Naugler WE, Wakefield L, Wilson EM, Finegold MJ, et al. Bipotential adult liver progenitors are derived from chronically injured mature hepatocytes. Cell Stem Cell. 2014;15:605–618. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2014.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sone M, Nishikawa Y, Nagahama Y, Kumagai E, Doi Y, Omori Y, et al. Recovery of mature hepatocytic phenotype following bile ductular transdifferentiation of rat hepatocytes in vitro. Am J Pathol. 2012;181:2094–2104. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2012.08.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hu MC, Qiu WR, Wang YP, Hill D, Ring BD, Scully S, et al. FGF-18, a novel member of the fibroblast growth factor family, stimulates hepatic and intestinal proliferation. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:6063–6074. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.10.6063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Urtasun R, Lopategi A, George J, Leung TM, Lu Y, Wang X, et al. Osteopontin, an oxidant stress sensitive cytokine, up-regulates collagen-I via integrin α(V)β(3) engagement and PI3K/pAkt/NFκB signaling. Hepatology. 2012;55:594–608. doi: 10.1002/hep.24701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fu D, Wakabayashi Y, Lippincott-Schwartz J, Arias IM. Bile acid stimulates hepatocyte polarization through a cAMP-Epac-MEK-LKB1-AMPK pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:1403–1408. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1018376108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Popov Y, Schuppan D. Targeting liver fibrosis: strategies for development and validation of antifibrotic therapies. Hepatology. 2009;50:1294–1306. doi: 10.1002/hep.23123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kountouras J, Billing BH, Scheuer PJ. Prolonged bile duct obstruction: a new experimental model for cirrhosis in the rat. Br J Exp Pathol. 1984;65:305–311. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Thompson NL, Hixson DC, Callanan H, Panzica M, Flanagan D, Faris RA, et al. A Fischer rat substrain deficient in dipeptidyl peptidase IV activity makes normal steady-state RNA levels and an altered protein. Use as a liver-cell transplantation model. Biochem J. 1991;273:497–502. doi: 10.1042/bj2730497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tarcin O, Basaranoglu M, Tahan V, Tahan G, Sücüllü I, Yilmaz N, et al. Time course of collagen peak in bile duct-ligated rats. BMC Gastroenterol. 2011;11:45. doi: 10.1186/1471-230X-11-45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Popov Y, Sverdlov DY, Bhaskar KR, Sharma AK, Millonig G, Patsenker E, et al. Macrophage-mediated phagocytosis of apoptotic cholangiocytes contributes to reversal of experimental biliary fibrosis. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2010;298:G323–334. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00394.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jirtle RL, Biles C, Michalopoulos G. Morphologic and histochemical analysis of hepatocytes transplanted into syngeneic hosts. Am J Pathol. 1980;101:115–126. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mito M, Kusano M, Onishi T, Saito T, Ebata H. Hepatocellular transplantation --morphological study on hepatocytes transplanted into rat spleen-- Gastroenterol Jpn. 1978;13:480–490. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gupta S, Aragona E, Vemuru RP, Bhargava KK, Burk RD, Chowdhury JR. Permanent engraftment and function of hepatocytes delivered to the liver: implications for gene therapy and liver repopulation. Hepatology. 1991;14:144–149. doi: 10.1002/hep.1840140124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Oertel M, Menthena A, Dabeva MD, Shafritz DA. Cell competition leads to a high level of normal liver reconstitution by transplanted fetal liver stem/progenitor cells. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:507–520. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.10.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Michalopoulos GK, Bowen WC, Mulè K, Lopez-Talavera JC, Mars W. Hepatocytes undergo phenotypic transformation to biliary epithelium in organoid cultures. Hepatology. 2002;36:278–283. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2002.34858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Limaye PB, Bowen WC, Orr AV, Luo J, Tseng GC, Michalopoulos GK. Mechanisms of hepatocyte growth factor-mediated and epidermal growth factor-mediated signaling in transdifferentiation of rat hepatocytes to biliary epithelium. Hepatology. 2008;47:1702–1713. doi: 10.1002/hep.22221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Michalopoulos GK, Barua L, Bowen WC. Transdifferentiation of rat hepatocytes into biliary cells after bile duct ligation and toxic biliary injury. Hepatology. 2005;41:535–544. doi: 10.1002/hep.20600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Limaye PB, Bowen WC, Orr A, Apte UM, Michalopoulos GK. Expression of hepatocytic- and biliary-specific transcription factors in regenerating bile ducts during hepatocyte-to-biliary epithelial cell transdifferentiation. Comp Hepatol. 2010;9:9. doi: 10.1186/1476-5926-9-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fukuda K, Sugihara A, Nakasho K, Tsujimura T, Yamada N, Okaya A, et al. The origin of biliary ductular cells that appear in the spleen after transplantation of hepatocytes. Cell Transplant. 2004;13:27–33. doi: 10.3727/000000004772664860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Watanabe H, Hata M, Terada N, Ueda H, Yamada N, Yamanegi K, et al. Transdifferentiation into biliary ductular cells of hepatocytes transplanted into the spleen. Pathology. 2008;40:272–276. doi: 10.1080/00313020801911546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yanger K, Zong Y, Maggs LR, Shapira SN, Maddipati R, Aiello NM, et al. Robust cellular reprogramming occurs spontaneously during liver regeneration. Genes Dev. 2013;27:719–724. doi: 10.1101/gad.207803.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sekiya S, Suzuki A. Hepatocytes, rather than cholangiocytes, can be the major source of primitive ductules in the chronically injured mouse liver. Am J Pathol. 2014;184:1468–1478. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2014.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nagoshi S. Osteopontin: Versatile modulator of liver diseases. Hepatol Res. 2014;44:22–30. doi: 10.1111/hepr.12166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Syn WK, Choi SS, Liaskou E, Karaca GF, Agboola KM, Oo YH, et al. Osteopontin is induced by hedgehog pathway activation and promotes fibrosis progression in nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Hepatology. 2011;53:106–115. doi: 10.1002/hep.23998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pritchett J, Harvey E, Athwal V, Berry A, Rowe C, Oakley F, et al. Osteopontin is a novel downstream target of SOX9 with diagnostic implications for progression of liver fibrosis in humans. Hepatology. 2012;56:1108–1116. doi: 10.1002/hep.25758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Couvelard A, Bringuier AF, Dauge MC, Nejjari M, Darai E, Benifla JL, et al. Expression of integrins during liver organogenesis in humans. Hepatology. 1998;27:839–847. doi: 10.1002/hep.510270328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Coffinier C, Gresh L, Fiette L, Tronche F, Schütz G, Babinet C, et al. Bile system morphogenesis defects and liver dysfunction upon targeted deletion of HNF1beta. Development. 2002;129:1829–1838. doi: 10.1242/dev.129.8.1829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Clotman F, Lannoy VJ, Reber M, Cereghini S, Cassiman D, Jacquemin P, et al. The onecut transcription factor HNF6 is required for normal development of the biliary tract. Development. 2002;129:1819–1828. doi: 10.1242/dev.129.8.1819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.