Abstract

Introduction

The use of autologous fat transplantation to correct volume and contour defects, scars, and asymmetry after breast cancer surgery has increased over the past 20 years. Many developments and refinements in this technique have taken place in recent years, and several studies of the safety of lipofilling in the breast have been published.

Presentation of case

We performed a literature review of this technique, highlighting the crucial role of lipofilling in breast cancer reconstruction.

Discussion

The efficacy of the fat graft transplantation depends on the experience and the technique used by the surgeon. The ASCs (adipose-derived stem cells) contained in the fat graft has proven to be crucial for breast reconstruction by mean the regeneration of tissue, through the chemotactic, paracrine, and immunomodulatory activities and their in situ differentiation.

Conclusion

The role of lipofilling for breast reconstruction could be more significant with the application of the findings of experimental research on tissue engineering and ASCs.

Keywords: Autologous fat transplantation, Breast reconstruction, Adipose-derived stem cells

Highlights

-

•

Autologous fat transplantation does not compromise oncological outcomes and minimizes discomfort to the patients.

-

•

The ASCs (adipose-derived stem cells) into the fat graft allow the regeneration of tissue after breast reconstruction.

-

•

The role of lipofilling could be more significant with the findings of experimental research on tissue engineering and ASCs.

1. Introduction

Autologous fat transplantation, also known as fat grafting or lipofilling, is an increasingly popular technique used in reconstructive surgery of the breast. Autologous fat grafting (AFG) was first used for filling defects and remodelling body contours over a century ago; however, its current usage dates back to 1987, when Bircoll [1] described a method that coupled liposuction with autologous transplantation of the harvested fat in the breast. The major advantage cited for this new technique was the presence of virtually limitless donor tissue that was soft and malleable [1]. AFG can be used for simple, aesthetic augmentation of the breast, correction of breast asymmetry, correction of breast deformities, as an adjunct or primary tool in breast reconstruction, and for soft-tissue coverage of breast implants [2]. An increasing number of authors proposed that lipofilling could improve the outcomes of total or partial reconstruction in breast cancer patients [2], [3], [4]. Although several teams have used repeated lipofilling sessions for total breast reconstruction, most authors consider that the lipofilling technique is indicated for the local improvement of small defects or asymmetry only [4], [5], [6]. Fat grafts are preferred over other graft types for the correction of volume and contour defects because fat is autologous, abundant, and easily harvested. Adipose tissue transfer in the form of fat grafting is now commonly used, and many variations on fat harvesting, preparation, and reinjection have been reported [7]. The filler function, however, is not the only important aspect of AFG, and numerous studies have reported the regenerative effects of autologous fat grafts [8], [9], [10]. These remarkable effects are particularly observed in irradiated tissue, and are most likely attributable to the high content of mesenchymal stem cells in fat grafts [10], [11], the quantity of which varies depending on the cell-isolation procedure used. However, initial attempts at AFG were often accompanied by a high rate of graft resorption and complications such as fat necrosis. Because the latter is associated with the formation of microcalcifications in the long-term, it caused concerns about possible interference with the prompt detection of breast cancer through mammography [12]. This led to its disapproval by the American Society of Plastic and Reconstructive Surgeons (ASPRS) in 1987. The ASPRS made the following statement in regard to AFG: “The committee is unanimous in deploring the use of autologous fat injection in breast augmentation. Much of the injected fat will not survive, and the known physiological response to necrosis of this tissue is scarring and calcification. As a result, detection of early breast carcinoma through xerography and mammography will become difficult and the presence of disease may go undiscovered.” [2], [13]. Nearly a decade later, Coleman introduced a new, refined technique of fat aspiration, purification, and injection that greatly improved graft survival and reduced the rate of complications [14]. His technique consisted of three steps: manual lipoaspiration under low pressure, centrifugation for 3 min at 3000 rpm, and reinjection in 3D [7]. Coleman technique was superior to conventional liposuction for harvesting and processing fat grafts because the Coleman fat grafts have a greater number of viable adipocytes and sustain more optimal cellular function than fat grafts harvested with conventional liposuction performed by an experienced surgeon [7]. Approximately the same time, a growing body of literature emerged suggesting that other procedures performed on the breast, such as reduction mammoplasties, also lead to scarring that is visible during breast screening and is far in excess of what would be expected after lipofilling [15], [16], [17]. Subsequent studies showed that these artefacts did not appreciably affect screening [17], [18]. In addition, several case reports and case series published over the years have not provided any definitive evidence to support these and other concerns about AFG. Finally, the lipofilling procedure has been greatly refined since its initial description, resulting in increased confidence in its use, including for breast reconstruction and remodelling [17], [19]. The recommendation against the procedure by the ASPRS, now known as the American Society of Plastic Surgeons, was reversed in 2009 [17], [20].

2. Application

Acquired contour deformities of the reconstructed breast are relatively common and independent of the technique used, presenting a frequent therapeutic challenge to reconstructive surgeons [21]. Primary breast reconstruction usually meets the goal of establishing a natural-appearing breast shape [21]. However, in the immediate or late postoperative period, secondary contour defects of the reconstructed breast can develop [21], [22]. There are important landmarks in the female breast, and the creation of a well-defined inframammary fold during breast reconstruction is a fundamental element in obtaining a good aesthetic result [23]. Autologous fat transplantation represents a simple solution to restore the profile of the breast after reconstruction. In fact, in breast cancer surgery, lipofilling is usually used for the correction of defects and asymmetry following tumour excision (or breast conservative surgery), with/without radiotherapy [24]. Adequate tissue expansion allows the use of autologous flaps or the insertion of definitive prosthetic implants for breast reconstruction. Tissue expansion can be carried out with the aid of a computer program to help the surgeon select the appropriate tissue expander during the planning stage of breast reconstruction [25], [26]. However, lipofilling can be used to improve soft-tissue coverage following prosthesis or tissue expander implantation and the volume replacement of implants in unsatisfactory oncoplastic breast reconstruction outcomes. Other applications of AFG are volume augmentation and refinement after autologous flap or whole breast reconstruction with serial fat grafting or scar correction [24].

3. Oncological safety

Autologous fat transplantation, as reported in the literature, can lead to fat necrosis and calcification but not significantly more frequently than after reduction mammoplasty [27]. There is no scientific evidence that fat grafting interferes with breast cancer detection [27], [28], [29]. The question of de novo cancer induction or accelerating growth of a pre-existing cancer by fat grafting has not been answered to date [19]. Thus far, no guarantee of cancer safety in fat grafting can be given to patients, although there is no scientific evidence of increased breast cancer occurrence or recurrence after fat grafting at this time [19].

4. Efficacy of lipofilling

Fat is a filler with ideal properties; it naturally integrates into tissues, is autologous, and is 100% biocompatible. However, this is not the only function of lipofilling. Fat is an active and dynamic tissue composed of several different cell types, including adipocytes, fibroblasts, smooth muscle cells, endothelial cells, and adipogenic progenitor cells called pre-adipocytes [30], [31], [32]. Stem cells isolated from lipoaspirates have demonstrated a broad in vitro adipogenic, chondrogenic, osteogenic, and myogenic lineage commitment [33], [34] as well as differentiation into pancreatic cells, hepatocytes, and neurogenic cells [35], [36], [37]. Cytometric analysis of adipose-derived stem cells (ASCs) has shown that these cells do not express CD31 and CD45, but do express CD34, CD73, CD105, and the mesenchymal stem cell marker CD90 [38], [39]. ASCs have a differentiation potential similar to that of other mesenchymal stem cells as well as a higher yield upon isolation and a greater proliferative rate in culture than bone marrow–derived stem cells [40], [41], [42]. Owing to these potentials and because they can be easily harvested in great amounts with minimal donor-site morbidity, ASCs are particularly promising for regenerative therapies [40], [43]. ASCs are present in the so-called stromal vascular fraction (SVF) of adipose tissue [44], together with a heterogeneous population of many other cell types, including pre-adipocytes, endothelial cells, pericytes, hematopoietic-lineage cells, and fibroblasts. The regenerative features of the SVF include its paracrine effects: SVF cells secrete vascular endothelial growth factor, hepatocyte growth factor, and transforming growth factor-β under different stimuli (e.g., hypoxia, growth factors) [45], [46] and strongly influence the differentiation of niche stem cells, promoting angiogenesis and wound healing, and potentially aiding new tissue growth and development [43]. Mature adipocytes react in a variety of ways in response to the pre-adipocyte environment [47]. In ischaemic conditions, these cells either die, survive, or undergo dedifferentiation; the dedifferentiated cells can re-accumulate fat and differentiate into adipocytes when an adequate vascular supply is re-established [47], [48], [49] Adipocytes are sensitive to their environment, and have short lifespans once removed from the body; they do not react well to excessive handling, refrigeration, or major trauma during tissue collection or processing [47], [50]. Initially, the graft survives via the direct diffusion of nutrients from plasma; therefore, smaller grafts, with higher surface area–to–volume ratios have an advantage over larger grafts, as a greater proportion of the graft is in contact with the graft bed [47], [51], [52]. This facilitates revascularisation [47], [53], which occurs as early as 48 h post-transplantation [47], [54]. Large grafts exhibit higher rates of liquefaction, necrosis, and cyst formation, while very small grafts tend to be reabsorbed [47], [55]. To ensure maximal take, many surgeons perform repeated transfers [47], [56], [57], [58]. In breast reconstruction surgery, fat transplantation can be used not only to fill atrophic scars but also to reduce scar contracture as a regenerative alternative to other surgical techniques [59]. From a histological point of view, autologous fat grafts containing ASCs show the ability to regenerate the dermis and subcutaneous tissue and improve the dermal and new collagen deposition, and local neoangiogenesis [60], [61], [62]. Mojallal et al. [63] showed that fat tissue grafting stimulates the neosynthesis of collagen fibres at the recipient site and makes the dermis thicker, thereby improving skin quality. Rigotti et al. [8] reported that the transplantation of lipoaspirates containing adult ASCs is a highly effective therapeutic approach for the treatment of degenerative, chronic lesions induced as late effects of oncologic radiation treatments. In fact, ultrastructural analysis of the radio-damaged tissue revealed a significant reduction of the capillary bed [8]. Owing to the angiogenic factors released from ASCs, lipofilling interrupted a vicious circle of vascular lesion, ischaemia, hyperpermeability, and fibrosis leading to increased ischaemia, and favoured the growth of a microvascular bed with the correct ratio of adipocytes to capillaries [8].

5. Surgical technique

Several techniques for fat harvesting and lipofilling are currently being employed. In all of these techniques, autologous fat is harvested, processed, and grafted [17]. Before surgery, the various adipose areas of the body are examined to identify natural fat deposits. The most common donor site is abdominal fat because it is one of the largest fat deposits. The second most common sites are the greater trochanteric region (saddle bags) and the inside of the thighs and knees [24]. Several techniques have been proposed for fat harvesting, and there is an ongoing debate in the literature as to which method produces more viable and functional adipocytes. The most frequently used methods for fat harvesting are vacuum aspiration or syringe aspiration with or without the infiltration of tumescent fluid. The “wet” technique involves the injection of a tumescent fluid consisting of NaCl, epinephrine, and a local anaesthetic drug, e.g., Klein solution [64]. The shear stress exerted on harvested fat has been determined to decrease adipocyte viability, and a low shear stress improves graft survival [17]. An alternative “dry” method of graft harvesting without the tumescent fluid can also be used. Cell viability in the samples harvested in this manner has been found to be similar to that observed in samples harvested by the “wet” method [17], [65]. However, the “dry” technique may lead to a greater requirement for analgesics [17], [64]. It is widely accepted that less-traumatic methods of fat harvesting result in increased adipocyte viability and graft survival [66], [67]. Coleman et al. [9] described a technique for fat harvesting that minimized trauma to the adipocytes. With a 3-mm, blunt-edged, 2-hole cannula connected to a 10-mL syringe, fat is suctioned manually by withdrawing the plunger. Erdim et al. [68] reported higher graft viability with lipoaspirates that were obtained using a 6-mm cannula rather than a 4-mm or 2-mm cannula. . Keck et al. have shown that suction-assisted lipoaspiration (SAL) with 0.5-bar negative pressure leads to cell yield and viability comparable to manual lipoaspiration [69]. Recently new methods of lipoaspiration have been developed such as suction- or power-assisted, laser-assisted, and ultrasound-assisted liposuction. These techniques were developed with the goal of achieving rapid tissue harvest, promoting skin tightening, and minimizing harvest-site morbidity [70]. Ultrasound-assisted liposuction (UAL), is gaining popularity for its ability to improve the process of lipoaspiration, by decreasing blood loss and tissue trauma [71]. During UAL, a specialized probe or cannula is used that transmits ultrasound vibrations into the fat tissue [70]. The vibrations lead to emulsification of the fat, making it easier to remove [72]. Dusher et al. [73] evaluated the regenerative abilities of ASCs harvested via a third-generation ultrasound-assisted liposuction (UAL) device versus ASCs obtained via standard suction-assisted lipoaspiration (SAL). They reported that ASCs obtained via UAL were of equal quality when directly compared with SAL [73]. Alternatively, laserassisted liposuction (LAL), which uses thermolysis to selectively lyse adipocytes, has been shown to decrease ASCs yield and viability as compared with SAL [74].

The most frequently used methods for fat processing are centrifugation, washing, and decantation. The widely used protocol to separate purified fat from call debris is the centrifugation, as described by Coleman [75]. Once the fat is harvested, the fat syringes are centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 3 min. After centrifugation, the lipoaspirate is separated into four layers: (a) the oily fraction, which leaks out of disrupted adipocytes; (b) the watery fraction, which consists of blood, lidocaine, and saline injected before the liposuction; (c) a cell pellet on the bottom; and (d) purified fat between the oily and watery fractions [24]. Subsequently, under local anaesthesia, the skin of the breast is punctured with an 18-gauge cannula that is used to release dermatofascial adhesions and scar tissue. The same cannula is then used to inject the fat graft in the subcutaneous and subglandular plane of the breast (Fig. 1, Fig. 2, Fig. 3a,b).

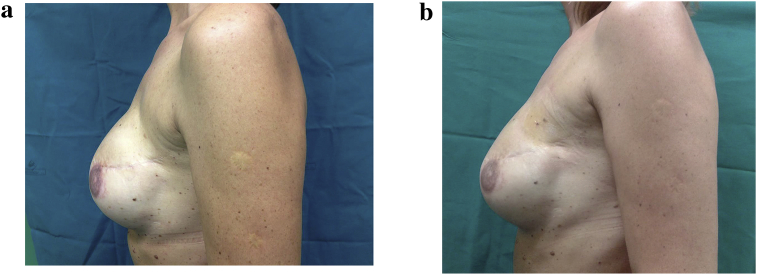

Fig. 1.

a – 40 year old patient subjected to mastectomy and recostruction with implants. Before treatment with lipofilling. b – 40 year old patient subjected to outer upper left quadrantectomy. After treatment with lipofilling at the level of the upper outer scar of left breast.

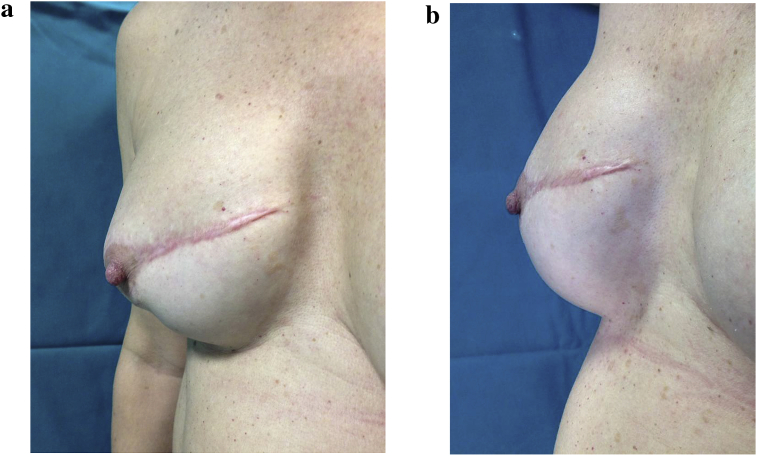

Fig. 2.

a – 38 year old patient subjected to mastectomy and recostruction with implants. Before treatment with lipofilling. b – 38 year old patient subjected to mastectomy and recostruction with implants. After treatment with lipofilling at the level of the scar of right breast.

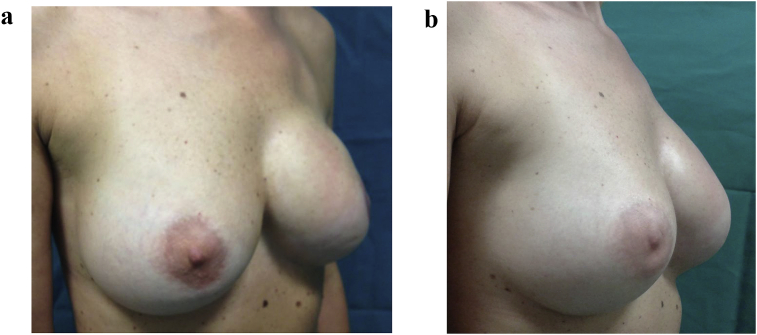

Fig. 3.

a – 35 year old patient subjected to mastectomy and recostruction with implants. Before treatment with lipofilling. b – 35 year old patient subjected to mastectomy and recostruction with implants. After treatment with lipofilling at the level of the scar of left breast.

The washing technique of fat processing is performed as follows: the harvested fat is washed with normal saline [76] or 5% glucose solution [77] to remove blood, the oily fraction, and cellular debris from the aspirated fat [24]. The least popular technique of fat processing is decantation, which uses gravity to precipitate the cellular component from the oily and watery components [24].

6. Complications

Fat tissue that is not perfused can die and result in necrotic cysts and even calcifications; however, these complications can occur after any type of breast surgery [2]. It was thought that fat grafting to the breast could potentially interfere with breast cancer detection; however, no conclusive evidence of such interference has been found [78]. Two cases of breast cancer after fat grafting to the breast were reported, but there was no delay in detection or treatment in these cases [78]. Radiological studies suggest that imaging technologies (ultrasound, mammography, and magnetic resonance imaging) can identify the grafted fat tissue, microcalcifications, and suspicious lesions; biopsies may be performed, if needed, for additional clarification [78]. The use of minuscule incisions and the blunt nature of the technique minimize the possibility of damaging the underlying structures such as nerves, ducts, and blood vessels [2]. Largo et al. [19] reported that among 1453 patients who underwent lipofilling of the breast, the most common complications were palpable nodules not requiring any surgical intervention (7%), unsatisfactory results in terms of volume, shape, and/or symmetry (3%), and infections (0.7%). Dysaesthesia, lymphadenopathy, pain, or haematoma seem to be less of a concern. No decrease in nipple sensitivity or lactation disorder due to fat grafting to the breast has been reported [19]. Death resulting from fat grafting has not been described [19]. Furthermore, donor-site complications appear to be minimal and related to the liposuction technique [24]. Possible donor-site complications include bruising, swelling, haematoma formation, paraesthesia or donor-site pain, infection, hypertrophic scarring, contour irregularities, and damage to underlying structures such as intraperitoneal or intramuscular penetration of the cannula [24]. Early experience noted that graft re-absorption was the main drawback of AFG, with 50%–90% graft-loss rates being reported [47], [79], [80], [81]. Large grafts exhibit higher rates of liquefaction, necrosis, and cyst formation, while very small grafts tend to be reabsorbed [47], [55]. To ensure maximal take, many surgeons perform repeated transfers [47], [56], [57], [58]. Groen et al. [82] in a review of 33 studies reported 461 complications in a total of 5502 patients. The reported total complication rate was 8.4% (95% CI 7.6–9.1) including nodules/masses 11.5%, cyst formation 6.9%, haematoma 6.3%, calcifications 5.2%, straie of breast 4.4%, fat/liponecrosis 4%, granulomas 3.6%, infections/cellulitis 0.8%, seroma 0.8%, donor site infections 0.7%, abces 0.6%, pneumothorax 0.2%, delayed wound healing 0.1%. Agha et al. [83] in a review of 24 studies reported 207 complications, 7,3% of 2832 treated breasts. Fat necrosis accounted for 62% of all complications and occurred in 17 of the 24 studies.

7. Discussion

Plastic surgeons and patients may have drastically different ideas of what constitutes an attractive, natural, and ideal breast shape [84], [85]. As with any surgical procedure, the technique used, the execution of the technique, and the experience of the surgeon affect the outcome. After mastectomy and breast reconstruction both with autogenous flaps and with implants, patients may notice subtle deformities and deficiencies, and consider their reconstructions incomplete [2], [86]. Grafted fat can provide missing coverage and may relax the breast capsule [2], [86]. Fat can be grafted in large or small volumes to correct otherwise difficult problems such as axillary deficiencies, poor breast shape, visible implant edges, capsular contracture, and even radiation damage [2], [86]. Often patients find the improvement after this procedure insufficient, and the procedure should be repeated to obtain a fully satisfying result. Beck et al. [87] reported an objective, computed tomography analysis that showed low fat-resorption rates during the first 3 months (0%–9.54%). The average fat resorption rate increased to 51.72% between the third and ninth months. The rate of fat resorption remained stable after the ninth month, and even seemed to be lower (44.02%) after 3 years. Every step in fat transplantation, i.e., harvesting, processing, and transplantation, is important, but viability of the harvested fat cells is crucial [88]. The chances of survival are higher the less the fat graft is manipulated and the more quickly it is re-injected [89]. Transplanted fat is vulnerable to pressure. Constricted skin with a very thin or scarred subcutaneous fat layer cannot sustain as large an amount of fat as healthy tissue, preferably with lax skin and a thick subcutaneous fat layer [88]. In fact, the vitality of ASCs has proven to be crucial for stimulating tissue regeneration through the chemotactic, paracrine, and immunomodulatory activities of the cells and in situ differentiation [38], [39].

8. Conclusion

In breast cancer surgery to correct irregularity and deformities, autologous fat transplantation is an acceptable procedure that does not compromise oncological outcomes and minimizes discomfort to the patients. The role of lipofilling for breast reconstruction could be more significant with the application of the findings of experimental research on tissue engineering and ASCs. Thus far, no guarantee of cancer safety in fat grafting can be given to patients, although there is no scientific evidence of increased breast cancer occurrence or recurrence after fat grafting at this time.

Ethical approval

Nothing to declare.

Sources of funding

Nothing to declare.

Author contribution

Dr. Simonacci Francesco, writing.

Dr. Bertozzi Nicolo’, data collections.

Dr. Grieco Michele Pio, data collections.

Prof. Eugenio Grignaffini, data collections.

Prof. Raposio Edoardo, study design.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declares that there is no conflict of interest regarding the publication of this paper.

Trial registry number – ISRCTN

Nothing to declare.

Guarantor

Dr. Simonacci Francesco.

Dr. Bertozzi Nicolo’.

Dr. Grieco Michele Pio.

Prof. Grignaffini Eugenio.

Prof. Raposio Edoardo.

Registration unique identifying number (UIN)

Nothing to declare.

References

- 1.Bircoll M. Cosmetic breast augmentation utilizing autologous fat and liposuction techniques. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 1987;79:267–271. doi: 10.1097/00006534-198702000-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Coleman S.R., Saboeiro A.P. Fat grafting to the breast revisited: safety and efficacy. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2007;119:775–785. doi: 10.1097/01.prs.0000252001.59162.c9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rietjens M., De Lorenzi F., Rossetto F. Safety of fat grafting in secondary breast reconstruction after cancer. J. Plast. Reconstr. Aesthet. Surg. 2011;64:477–483. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2010.06.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Petit J.Y., Botteri E., Lohsiriwat V. Locoregional recurrence risk after lipofilling in breast cancer patients. Ann. Oncol. 2012;23:582–588. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdr158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Amar O., Bruant-Rodier C., Lehmann S., Bollecker V., Wilk A. Fat tissue transplant: restoration of the mammary volume after conservative treatment of breast cancers, clinical and radiological considerations. Ann. Chir. Plast. Esthet. 2008;53:169–177. doi: 10.1016/j.anplas.2007.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kijima Y., Yoshinaka H., Owaki T., Aikou T. Early experience of immediate reconstruction using autologous free dermal fat graft after breast conservational surgery. J. Plast. Reconstr. Aesthet. Surg. 2007;60:495–502. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2006.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gir P., Brown S.A., Oni G., Kashefi N., Mojallal A., Rohrich R.J. Fat grafting: evidence-based review on autologous fat harvesting, processing, reinjection, and storage. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2012;130:249–258. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e318254b4d3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rigotti G., Marchi A., Galiè M. Clinical treatment of radiotherapy tissue damage by lipoaspirate transplant: a healing process mediated by adipose-derived adult stem cells. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2007;119:1409–1422. doi: 10.1097/01.prs.0000256047.47909.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Coleman S.R. Structural fat grafting: more than a permanent filler. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2006;118:108S–120S. doi: 10.1097/01.prs.0000234610.81672.e7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mestak O., Sukop A., Hsueh Y.S. Centrifugation versus PureGraft for fatgrafting to the breast after breast-conserving therapy. World J. Surg. Oncol. 2014;12:178. doi: 10.1186/1477-7819-12-178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lindroos B., Suuronen R., Miettinen S. The potential of adipose stem cells in regenerative medicine. Stem Cell Rev. 2011;7:269–291. doi: 10.1007/s12015-010-9193-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Krastev T.K., Jonasse Y., Kon M. Oncological safety of autologous lipoaspirate grafting in breast cancer patients: a systematic review. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2013;20:111–119. doi: 10.1245/s10434-012-2565-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Report on autologous fat transplantation ASPRS Ad-Hoc committee on new procedures. Plast. Surg. Nurs. September 30, 1987;1987(7):140–141. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Coleman S.R. Facial recontouring with lipostructure. Clin. Plast. Surg. 1997;24:347–367. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brown F.E., Sargent S.K., Cohen S.R., Morain W.D. Mammographic changes following reduction mammaplasty. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 1987;80:691–698. doi: 10.1097/00006534-198711000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Isaacs G., Rozner L., Tudball C. Breast lumps after reduction mammaplasty. Ann. Plast. Surg. 1985;15:394–399. doi: 10.1097/00000637-198511000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kasem A., Wazir U., Headon H., Mokbel K. Breast lipofilling: a review of current practice. Arch. Plast. Surg. 2015;42:126–130. doi: 10.5999/aps.2015.42.2.126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Danikas D., Theodorou S.J., Kokkalis G., Vasiou K., Kyriakopoulou K. Mammographic findings following reduction mammoplasty. Aesthetic Plast. Surg. 2001;25:283–285. doi: 10.1007/s002660010137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Largo R.D., Tchang L.A., Mele V. Efficacy, safety and complications of autologous fat grafting to healthy breast tissue: a systematic review. J. Plast. Reconstr. Aesthet. Surg. 2014;67:437–448. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2013.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.American Society of Plastic Surgeons . American Society of Plastic Surgeons; Arlington Heights, IL: 2009. Fat Transfer/fat Graft and Fat Injection: ASPS Guiding Principles. [cited 2014 Dec 24] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cigna E., Ribuffo D., Sorvillo V. Secondary lipofilling after breast reconstruction with implants. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2012;16:1729–1734. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ribuffo D., Atzeni M., Serratore F., Guerra M., Bucher S. Cagliari University Hospital (CUH) protocol for immediate alloplastic breast reconstruction and unplanned radiotherapy. A preliminary report. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2011;15:840–844. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fan J., Raposio E., Wang J., Nordström R.E. Development of the inframammary fold and ptosis in breast reconstruction with textured tissue expanders. Aesthetic Plast. Surg. 2002;26:219–222. doi: 10.1007/s00266-002-1477-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hamza A., Lohsiriwat V., Rietjens M. Lipofilling in breast cancer surgery. Gland. Surg. 2013;2:7–14. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2227-684X.2013.02.03. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Raposio E., Cicchetti S., Adami M., Ciliberti R.G., Santi P.L. Computer planning for breast reconstruction by tissue expansion: an update. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2004;113:2095–2097. doi: 10.1097/01.prs.0000121189.51406.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Raposio E., Caregnato P., Barabino P. Computer-based preoperative planning for breast reconstruction in the woman with unilateral breast hypoplasia. Minerva Chir. 2002;57:711–714. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Veber M., Tourasse C., Toussoun G., Moutran M., Mojallal A., Delay E. Radiographic findings after breast augmentation by autologous fat transfer. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2011;127:1289–1299. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e318205f38f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Parikh R.P., Doren E.L., Mooney B., Sun W.V., Laronga C., Smith P.D. Differentiating fat necrosis from recurrent malignancy in fat-grafted breasts: an imaging classification system to guide management. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2012;130:761–772. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e318262f03b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pulagam S.R., Poulton T., Mamounas E.P. Long-term clinical and radiologic results with autologous fat transplantation for breast augmentation: case reports and review of the literature. Breast J. 2006;12:63–65. doi: 10.1111/j.1075-122X.2006.00188.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Katz A.J., Llull R., Hedrick M.H., Futrell J.W. Emerging approaches to the tissue engineering of fat. Clin. Plast. Surg. 1999;26:587–603. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Raposio E., Guida C., Baldelli I. Characterization and induction of human pre-adipocytes. Toxicol In Vitro. 2007:21330–21334. doi: 10.1016/j.tiv.2006.09.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Raposio E., Guida C., Coradeghini R. In vitro polydeoxyribonucleotide effects on human pre-adipocytes. Cell Prolif. 2008;41:739–754. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2184.2008.00547.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Altman A.M., Abdul Khalek F.J., Alt E.U., Butler C.E. Adipose tissue-derived stem cells enhance bioprosthetic mesh repair of ventral hernias. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2010;126:845–854. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181e6044f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Makarov A.V., Arutyunyan I.V., Bol'shakova G.B., Volkov A.V., Gol'dshtein D.V. Morphological changes in paraurethral area after introduction of tissue engineering construct on the basis of adipose tissue stromal cells. Bull. Exp. Biol. Med. 2009;148:719–724. doi: 10.1007/s10517-010-0801-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Coradeghini R., Guida C., Scanarotti C., Sanguineti R., Bassi A.M., Parodi A. A comparative study of proliferation and hepatic differentiation of human adipose-derived stem cells. Cells Tissues Organs. 2010;191:466–477. doi: 10.1159/000273266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Aluigi M.G., Coradeghini R., Guida C. Pre-adipocytes commitment to neurogenesis 1: preliminary localisation of cholinergic molecules. Cell Biol. Int. 2009;33:594–601. doi: 10.1016/j.cellbi.2009.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Scanarotti C., Bassi A.M., Catalano M., Guida C., Coradeghini R., Falugi C. Neurogenic-committed human pre-adipocytes express CYP1A isoforms. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2010;184:474–483. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2010.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Raposio E., Caruana G., Petrella M., Bonomini S., Grieco M.P. A standardized method of isolating adipose-derived stem cells for clinical applications. Ann. Plast. Surg. 2016;76:124–126. doi: 10.1097/SAP.0000000000000609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Raposio E., Caruana G., Bonomini S., Libondi G. A novel and effective strategy for the isolation of adipose-derived stem cells: minimally manipulated adipose-derived stem cells for more rapid and safe stem cell therapy. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2014;133:1406–1409. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0000000000000170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Raposio E., Bertozzi N., Bonomini S., Bernuzzi G., Formentini A., Grignaffini E. Adipose-derived stem cells added to platelet-rich plasma for chronic skin ulcer therapy. Wounds. 2016;28:126–131. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Higuci A., Chuang C.W., Ling Q.D. Differentiation ability of adipose-derived stem cells separated from adipose tissue by a membrane filtration method. J. Memb. Sci. 2011;366:286–294. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Salibian A.A., Widgerow A.D., Abrouk M., Evans G.R. Stem cells in plastic surgery: a review of current clinical and translational applications. Arch. Plast. Surg. 2013;40:666–675. doi: 10.5999/aps.2013.40.6.666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Caruana G., Bertozzi N., Boschi E., Pio Grieco M., Grignaffini E., Raposio E. Role of adipose-derived stem cells in chronic cutaneous wound healing. Ann. Ital. Chir. 2015;86:1–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tang W., Zeve D., Suh J.M. White fat progenitor cells reside in the adipose vasculature. Science. 2008;322:583–586. doi: 10.1126/science.1156232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kapur S.K., Katz A.J. Review of the adipose derived stem cell secretome. Biochimie. 2013;95:2222–2228. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2013.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Salgado A.J., Reis R.L., Sousa N.J., Gimble J.M. Adipose tissue derived stem cells secretome: soluble factors and their roles in regenerative medicine. Curr. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2010;5:103–110. doi: 10.2174/157488810791268564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chan C.W., McCulley S.J., Macmillan R.D. Autologous fat transfer–a review of the literature with a focus on breast cancer surgery. J. Plast. Reconstr. Aesthet. Surg. 2008;61:1438–1448. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2008.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ellenbogen R. Autologous fat injection. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 1991;88:543–544. doi: 10.1097/00006534-199109000-00040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ullmann Y., Hyams M., Ramon Y., Beach D., Peled I.J., Lindenbaum E.S. Enhancing the survival of aspirated human fat injected into nude mice. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 1998;101:1940–1944. doi: 10.1097/00006534-199806000-00026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Illouz Y.G. Study of subcutaneous fat. Aesthetic Plast. Surg. 1990;14:165–177. doi: 10.1007/BF01578345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Niemelä S.M., Miettinen S., Konttinen Y. Fat tissue: views on reconstruction and exploitation. J. Craniofac Surg. 2007;18:325–335. doi: 10.1097/scs.0b013e3180333b6a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Boschert M.T., Beckert B.W., Puckett C.L., Concannon M.J. Analysis of lipocyte viability after liposuction. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2002;109:761–765. doi: 10.1097/00006534-200202000-00054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Fagrell D., Eneström S., Berggren A., Kniola B. Fat cylinder transplantation: an experimental comparative study of three different kinds of fat transplants. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 1996;98:90–96. doi: 10.1097/00006534-199607000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Moscona R., Shoshani O., Lichtig H., Karnieli E. Viability of adipose tissue injected and treated by different methods: an experimental study in the rat. Ann. Plast. Surg. 1994;33:500–506. doi: 10.1097/00000637-199411000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Peer L.A. The neglected free fat graft, its behavior and clinical use. Am. J. Surg. 1956;92:40–47. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(56)80009-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Coleman S.R. Long-term survival of fat transplants: controlled demonstrations. Aesthetic Plast. Surg. 1995;19:421–425. doi: 10.1007/BF00453875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sattler G., Sommer B. Liporecycling: a technique for facial rejuvenation and body contouring. Dermatol. Surg. 2000;26:1140–1144. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Spear S.L., Wilson H.B., Lockwood M.D. Fat injection to correct contour deformities in the reconstructed breast. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2005;116:1300–1305. doi: 10.1097/01.prs.0000181509.67319.cf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Khouri R.K., Smit J.M., Cardoso E. Percutaneous aponeurotomy and lipofilling: a regenerative alternative to flap reconstruction? Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2013;132:1280–1290. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3182a4c3a9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Klinger M., Marazzi M., Vigo D., Torre M. Fat injection for cases of severe burn outcomes: a new perspective of scar remodeling and reduction. Aesthetic Plast. Surg. 2008;32:465–469. doi: 10.1007/s00266-008-9122-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Caviggioli F., Villani F., Forcellini D., Vinci V., Klinger F. Scar treatment by lipostructure. Update Plast. Surg. 2009;2:51–53. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Klinger M., Caviggioli F., Klinger F.M. Autologous fat graft in scar treatment. J. Craniofac Surg. 2013;24:1610–1615. doi: 10.1097/SCS.0b013e3182a24548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Mojallal A., Lequeux C., Shipkov C. Improvement of skin quality after fat grafting: clinical observation and an animal study. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2009;124:765–774. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181b17b8f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Klein J.A. Tumescent technique for local anesthesia improves safety in large-volume liposuction. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 1993;92:1085–1098. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Agostini T., Lazzeri D., Pini A. Wet and dry techniques for structural fat graft harvesting: histomorphometric and cell viability assessments of lipoaspirated samples. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2012;130:331e–339e. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3182589f76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kakagia D., Pallua N. Autologous fat grafting: in search of the optimal technique. Surg. Innov. 2014;21:327–336. doi: 10.1177/1553350613518846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Pu L.L., Coleman S.R., Cui X., Ferguson R.E., Jr., Vasconez H.C. Autologous fat grafts harvested and refined by the Coleman technique: a comparative study. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2008;122:932–937. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181811ff0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Erdim M., Tezel E., Numanoglu A., Sav A. The effects of the size of liposuction cannula on adipocyte survival and the optimum temperature for fat graft storage: an experimental study. J. Plast. Reconstr. Aesthet. Surg. 2009;62:1210–1214. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2008.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Keck M., Kober J., Riedl O. Power assisted liposuction to obtain adipose-derived stem cells: impact on viability and differentiation to adipocytes in comparison to manual aspiration. J. Plast. Reconstr. Aesthet. Surg. 2014;67:e1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2013.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Shridharani S.M., Broyles J.M., Matarasso A. Liposuction devices: technology update. Med. Dev. (Auckl) 2014;7:241–251. doi: 10.2147/MDER.S47322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Nagy M.W., Vanek P.F., Jr. A multicenter, prospective, randomized, single-blind, controlled clinical trial comparing VASER-assisted Lipoplasty and suction-assisted Lipoplasty. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2012;129:681e–689e. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3182442274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Cimino W.W. The physics of soft tissue fragmentation using ultrasonic frequency vibration of metal probes. Clin. Plast. Surg. 1999;26:447–461. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Duscher D., Atashroo D., Maan Z.N. Ultrasound-assisted liposuction does not compromise the regenerative potential of adipose-derived stem cells. Stem Cells Transl. Med. 2016;5:248–257. doi: 10.5966/sctm.2015-0064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Chung M.T., Zimmermann A.S., Paik K.J. Isolation of human adipose-derived stromal cells using laser-assisted liposuction and their therapeutic potential in regenerative medicine. Stem Cells Transl. Med. 2013;2:808–817. doi: 10.5966/sctm.2012-0183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Coleman S.R. Facial augmentation with structural fat grafting. Clin. Plast. Surg. 2006;33:567–577. doi: 10.1016/j.cps.2006.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Asken S. Autologous fat transplantation: micro and macro techniques. Am. J. Cosmet. Surg. 1987;4:111–121. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Fournier P.F. Fat grafting: my technique. Dermatol. Surg. 2000;26:1117–1128. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Gutowski K.A. ASPS Fat Graft Task Force. Current applications and safety of autologous fat grafts: a report of the ASPS fat graft task force. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2009;124:272–280. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181a09506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Peer L.A. Loss of weight and volume in human fat grafts: withpostulation of a ‘‘cell survival theory’’. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 1950;5:217–230. [Google Scholar]

- 80.Chajchir A. Fat injection: long-term follow-up. Aesthetic Plast. Surg. 1996;20:291–296. doi: 10.1007/BF00228458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Mikus J.L., Koufman J.A., Kilpatrick S.E. Fate of liposuctioned and purified autologous fat injections in the canine vocal fold. Laryngoscope. 1995;105:17–22. doi: 10.1288/00005537-199501000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Groen J.W., Negenborn V.L., Twisk D.J. Autologous fat grafting in onco-plastic breast reconstruction: a systematic review on oncological and radiological safety, complications, volume retention and patient/surgeon satisfaction. J. Plast. Reconstr. Aesthet. Surg. 2016;69:742–764. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2016.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Agha R.A., Fowler A.J., Herlin C., Goodacre T.E., Orgill D.P. Use of autologous fat grafting for breast reconstruction: a systematic review with meta-analysis of oncological outcomes. J. Plast. Reconstr. Aesthet. Surg. 2015;68:143–161. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2014.10.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Hsia H.C., Thomson J.G. Differences in breast shape preferences between plastic surgeons and patients seeking breast augmentation. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2003;112:312–320. doi: 10.1097/01.PRS.0000066365.12348.A7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Raposio E., Belgrano V., Santi P., Chiorri C. Which is the ideal breast Size?:Some social clues for plastic surgeons. Ann. Plast. Surg. 2016;76:340–345. doi: 10.1097/SAP.0000000000000471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Rigotti G., Marchi A., Galie M. Clinical treatment of radiotherapy tissue damage by lipoaspirate transplant: a healing process mediated by adipose-derived adult stem cells. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2007;119:1409–1422. doi: 10.1097/01.prs.0000256047.47909.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Beck M., Amar O., Bodin F., Lutz J.C., Lehmann S., Bruant-Rodier C. Evaluation of breast lipofilling after sequelae of conservative treatment for cancer. Eur. J. Plastic Surg. 2012;35:221–228. [Google Scholar]

- 88.Peltoniemi H.H., Salmi A., Miettinen S. Stem cell enrichment does not warrant a higher graft survival in lipofilling of the breast: a prospective comparative study. J. Plast. Reconstr. Aesthet. Surg. 2013;66:1494–1503. doi: 10.1016/j.bjps.2013.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Smith P., Adams W.P., Jr., Lipschitz A.H. Autologous human fat grafting: effect of harvesting and preparation techniques on adipocyte graft survival. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2006;117:1836–1844. doi: 10.1097/01.prs.0000218825.77014.78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]